-

Oocyte maturation represents a complicated procedure entailing multiple 'stop-and-go' stages. These stages are stringently controlled during the entire reproductive cycle. The oocyte undergoes two rounds of meiosis before forming a mature gamete[1]. The maturation process of oocytes can be divided into nuclear maturation, cytoplasmic maturation, and cell membrane maturation, and mitochondria are among the most crucial organelles within the cytoplasm[2]. Mitochondria are in the process of dynamic changes in the cell. Mitochondrial dynamics pertains to the dynamic events such as fusion, fission, and selective breakdown of mitochondria in cells to maintain their morphology and to regulate cell autophagy, signal transduction, and apoptosis, which plays a critical part in keeping the normal operations of cells[3]. Fusion and fission are regulated by a variety of proteins, such as dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1), which has the function of regulating mitochondrial fission via mitofusin 1 (Mfn1), and mitofusin 2 (Mfn2)[4]. Autophagy of Mitochondria plays a crucial role in regulating organelle equilibrium and ensuring proper mitochondrial function through quality control mechanisms. This cellular process primarily involves the specific sequestration and subsequent breakdown of dysfunctional mitochondrial components through autophagic pathways[5]. These dynamic alterations assist in sustaining the normal functioning of mitochondria and enabling them to adapt to the metabolic requirements during cell development. Considering the substantial energy requirements for transcriptional and translational activities during meiotic progression, maintaining proper mitochondrial function is of great necessity[6]. Emerging evidence reveals a significant association between female gamete developmental potential, mitochondrial genome copy number, and cellular energy status. Mitochondria stand as the sole organelles within animal cells that possess genetic material known as mtDNA. On average, mouse oocytes may carry only one mtDNA copy per mitochondrion, then defective mtDNA equals defective mitochondria, and oocytes can maintain normal mitochondrial function by quality control at the single-genome level through selective mitophagy[7]. During oocyte maturation, a large amount of energy is required to support various cellular activities, which is mainly provided by ATP produced by mitochondria. Approaches like drug treatment and mitochondrial supplementation have been put forward to boost ATP generation and enhance oocyte quality[8].

Oxidative stress is defined as the disturbance of the equilibrium between the generation and elimination of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS). This leads to a rise in ROS levels that exceeds the scavenging ability of the cellular antioxidant system, ultimately causing damage to cells[9]. ROS are predominantly generated during the process of the mitochondrial respiratory chain when ATP is being produced. Under normal conditions, ROS levels are maintained within a dynamic range to ensure the normal development of oocytes[10]. However, external or internal stimuli may affect the production and elimination of ROS in mitochondria, breaking the intracellular redox homeostasis, giving rise to the accumulation of ROS, and instigating oxidative stress. In oocytes, oxidative stress has the potential to inflict irreversible harm on biological macromolecules like DNA, lipids, and proteins, thereby impeding oocyte maturation[11]. At the same time, the elevated ROS level may trigger the apoptosis signaling pathway through the mitochondrial pathway, DNA damage, NF-κB activation, MAPK pathway, and endoplasmic reticulum stress[12]. Oxidative stress may also activate autophagy. During oocyte development, moderate autophagy helps to remove damaged mitochondria and other organelles, thereby alleviating cell damage caused by oxidative stress. However, excessive oxidative stress may lead to an abnormal increase in autophagy, and affect the normal development of oocytes[13].

HIF-1 functions as a nuclear protein with the ability to carry out transcriptional activity, which is closely involved in cell metabolism, development, and proliferation, and cell apoptosis in normoxic and hypoxic environments[14]. The transcription factor HIF-1 has a heterodimeric structure formed by HIF-1α and HIF-1β. HIF-1β shows stable expression in cells. In contrast, the expression of HIF-1α is determined by the intracellular oxygen concentrations. In a normoxic environment, HIF-1α exists in a state of dynamic equilibrium regarding its expression and degradation[15]. HIF-1α, serving as a transcription factor, holds a pivotal position in the cellular response to a hypoxic environment. However, recent investigations have revealed that HIF-1α also exerts a diverse range of crucial functions even under normoxic conditions. In normal oxygen circumstances, HIF-1α can attach to the promoter regions of certain genes associated with glucose metabolism, promote the expression of hexokinase 2 (HK2), phosphofructokinase 1 (PFK1), and other genes, enhance glycolytic flux, and provide more energy for cells[16]. This is particularly important for some cells with high metabolic demands, helping them to proliferate and function rapidly under normal oxygen conditions. Under normoxic conditions, HIF-1α can activate the expression of cell cyclin-related proteins, such as Cyclin D1, promote cells from the G1 phase to the S phase, and promote cell proliferation. In addition, the stabilization of HIF-1α influences cell proliferation and apoptosis. For example, HIF-1α stabilized by USP14 inhibits cell proliferation under normoxic conditions[17]. HIF-1α activation during normoxia is also involved in controlling cell phenotype and function. For example, in vascular smooth muscle cells, HIF-1α activation can promote cell transformation from contractile to synthetic forms and increase collagen synthesis and secretion[18].

During follicular development, increased oxygen consumption leads to decreased oxygen concentration in follicular fluid, forming a hypoxic environment, and HIF-1α is activated to induce downstream signaling pathways, increase follicle maturation rate, and reduce atretic follicles[19]. HIF-1α controls the secretion of relevant angiogenic factors from oocytes and prompts glycolysis within granulosa cells, thereby fulfilling the energy demands for oocyte development[20]. In the process of follicle development, the production of a large amount of metabolic waste necessitates autophagy to break down abnormal proteins and damaged organelles within the cells. Excessive metabolic waste may lead to insufficient autophagy function and trigger cell apoptosis. HIF-1α can induce signaling pathways to increase the rate of autophagy and protect cells from apoptosis[21].

However, whether HIF1α signaling is activated during oocyte culture and the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. In this research, we explored the impact of HIF-1α on oocyte maturation and its underlying mechanism by suppressing the activity of HIF-1α.

-

TRITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (ZF-0316), Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (ZF-0511), Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG H&L (ZF-0512), Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG H&L (ZF-0513) were purchased from Zsbio (Beijing, China). The rabbit anti-HIF1 alpha antibody (ER1802-41) was obtained from Huabio. Rabbit anti-phospho-DRP1 antibody (3455S), Rabbit anti-LC3B antibody (2775S) was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (CA, USA). Mouse anti-β-actin antibody (66009-1-Ig), rabbit anti-α-tubulin antibody (11224-1-AP), mouse anti-GAPDH antibody (60004-1-Ig), rabbit anti-TOM20 antibody (11802-1-AP), rabbit anti-FIS1 antibody (10956-1-AP), rabbit anti-Parkin antibody (14060-1-AP) were obtained from Proteintech (Wuhan, China). Additionally, Hochest 33342 was from Sigma-Aldrich Corp (MO, USA). Mitochondrial membrane potential assay kit with TMRE (C2001S-1), reactive oxygen species assay kit (S0033S-1), Annexin V-FITC apoptosis detection kit (C1062M), lyso-tracker red (C1046) were purchased from Beyotime (Beijing, China). Mito-tracker red CMXRos (M7512) was purchased from Thermo Fisher (Shanghai, China). All experimental reagents and compounds were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Corporation, unless specifically noted for alternative sources in the materials and methods section.

Oocyte collection and in vitro culture

-

In the experiment, oocytes were obtained from female ICR mice aged 6 to 7 weeks. Mice were euthanized through cervical dislocation. Subsequently, their ovaries were excised and transferred into pre-warmed M2 medium for the collection of GV-stage oocytes. Oocytes were then cultured in M16 medium, which was covered with liquid paraffin oil. The cultivation took place at 37 °C within an atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy

-

A minimum of 30 oocytes were procured for each group. The collected oocytes were subjected to fixation using 4% paraformaldehyde solution, with an incubation period lasting between 30 min to 1 h under ambient temperature conditions. Following fixation, for 20 min at room temperature, the oocytes were incubated in a PBS solution consisting of 0.5% Triton X-100. Then, the oocytes were blocked with PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h at room temperature. After that, the oocytes were incubated in the specific antibody overnight at 4 °C. The oocytes underwent three washes in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20 and 0.01% Triton X-100. Subsequently, for 60 min at room temperature, they were incubated with the proper secondary antibody. After washing the oocytes three times in duplicate, Hoechst 33342 was used for the staining of chromosomes. Finally, we utilized a laser-scanning confocal microscope to observe the oocytes.

Fluorescence staining of live cells was applied to detect mitochondria, oxidative stress, early apoptosis, and lysosomes. MI stage oocytes from the experimental and control groups were collected and transferred to M2 medium with living cell staining solution, and stained at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 30 min before immediate imaging under confocal microscopy.

Western blot analysis

-

From each group, a total of 150 oocytes at the MI stage were gathered and then lysed in Laemmil sample buffer. The centrifuge tube holding the oocyte lysate underwent heating in a metal bath at 100 °C for 10 min. Following the heating step, the centrifuge tube was quickly placed in the refrigerator at −20 °C for storage. Then the samples were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). The electrophoresis parameters were adjusted to 160 V, and the electrophoresis time was about 80 min. After that, the proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. These membranes were then blocked using a rapid blocking solution for 15 min at room temperature. The membranes were incubated at 4 °C overnight with primary antibodies against HIF-1α, TOM20, Fis1, Parkin, p-Drp1, α-tubulin, β-actin, and GAPDH. Subsequently, the membranes underwent three washes in TBST. They were then incubated with the appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at a temperature of 37 °C. In the end, TBST was used to rinse the membrane three times. Subsequently, the PVDF membrane had treatment applied with the enhanced chemiluminescence reagent, and the protein bands were made visible using Tanon-3900. The relative signal intensities were quantified using Image J software.

Quantitative real-time PCR

-

RNA was extracted using magnetic beads and reverse transcribed to obtain cDNA, which was stored at −80 °C. For assay, each of the cDNA samples was added separately to 96-well plates, ensuring at least three replicates per assay. A total system of 20 μL was prepared. After centrifugation, the mRNA levels were gauged via Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction, with the use of One plus real-time PCR system to obtain mRNA level melting curves, and the dissolution curves were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCᴛ method. To standardize the expression levels of target genes, the GAPDH expression levels in each corresponding sample were used as the reference.

ATP level detection

-

The ATP level of oocytes during the MI phase in the control and experimental groups was measured using an ATP bioluminescence kit. At least 30 oocytes were collected from each group for each experiment, added with 100 μL ATP release reagent, shaken on ice for 3 min, then added with 100 μL working solution, mixed and added into 96-wells, chemiluminescence detection was performed by multifunctional microplate reader. The experiment was repeated three times.

Statistical analysis and relative fluorescence intensity measure

-

Immunofluorescence analysis was conducted under the same conditions for both the control and experimental groups. All the images were obtained by utilizing the identical settings of the confocal microscope. The average fluorescence intensity per unit area within the target region was measured, and the fluorescence intensity of the samples was analyzed using ZEN lite 2012 and ImageJ software.

For each assay, at least three independent biological replicates were performed with no less than 30 oocytes per set of samples. Results are expressed as mean ± SEMs. Statistical analysis was carried out using GraphPad Prism software. An independent-samples t-test was utilized for statistical comparisons. Significance was defined as a p-value less than 0.05.

-

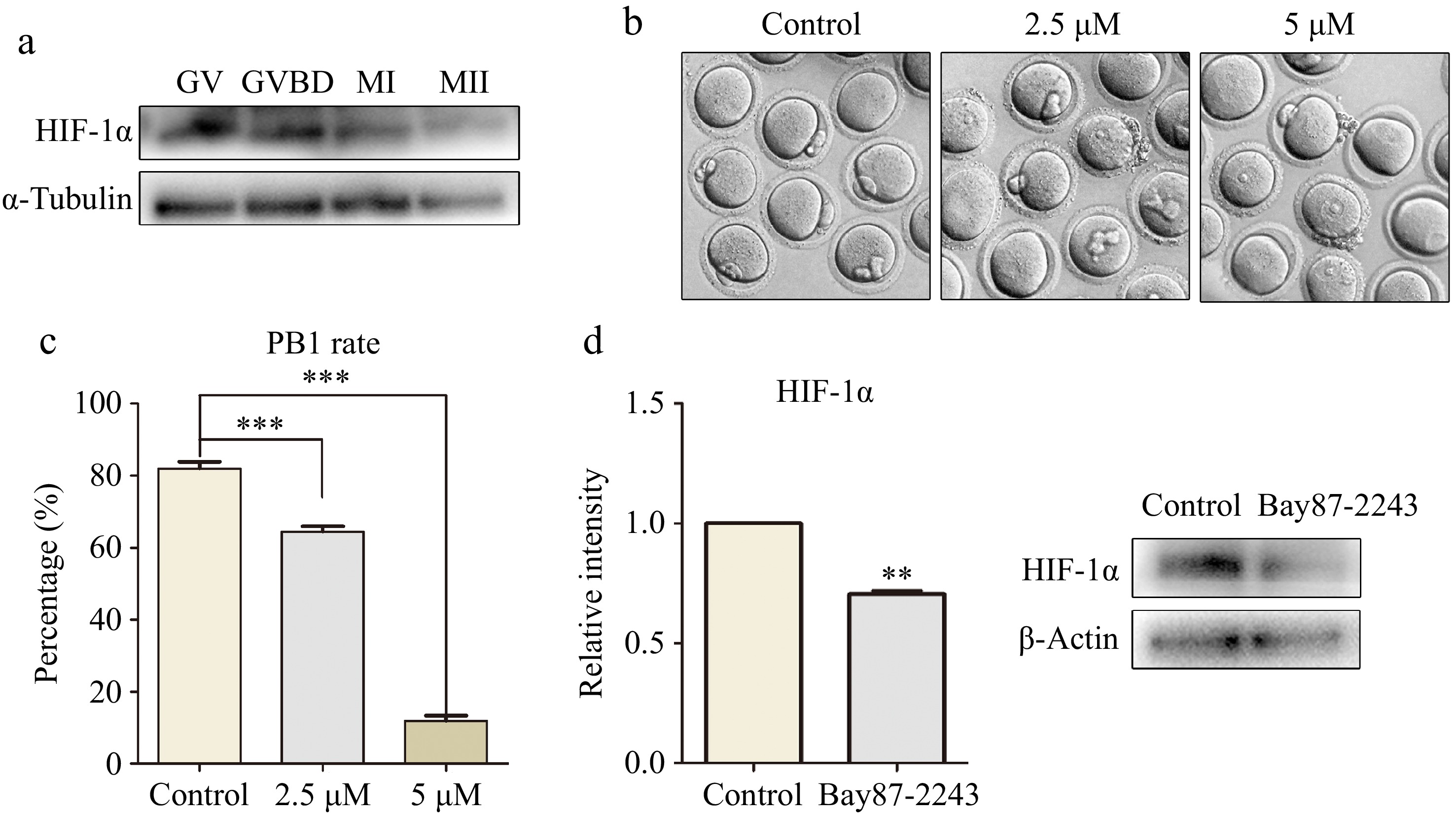

We first examined the HIF-1α expression in oocytes by Western blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 1a, we found that HIF-1α expressed at the GV, GVBD, MI, and MII stages during oocyte maturation. We probed into the function of HIF-1α by treating oocytes using a HIF-1α inhibitor, Bay87-2243. We set up concentration gradients at 2.5 and 5 µM. After culturing for 14 h, the development status of each group was observed via a microscope. As is evident from Fig. 1b, most oocytes in the control group expelled the first polar body and entered the metaphase II (MII) stage. Compared to the control group, the groups treated with 2.5 and 5 µM inhibitors exhibited a marked decrease in polar body extrusion rates (control group, 82.00% ± 1.87%, n = 44; 2.5 μM treatment group, 66.90% ± 1.65%, n = 38, p < 0.001; 5 μM treatment group, 11.85% ± 1.45%, n = 50, p < 0.001; Fig. 1c). These data implied that the reduction in HIF-1α activity influences oocyte maturation. We finally selected 2.5 µM Bay87-2243 treatment conditions for subsequent studies. As verified by Western blot, the expression of HIF-1α protein in oocytes treated with 2.5 μM Bay87-2243 was significantly decreased (control group, 1.0 ± 0.0, n = 150; treatment group, 0.71 ± 0.02, n = 150, p < 0.01; Fig. 1d).

Figure 1.

The inhibition of HIF-1α activity led to the failure of oocyte maturation. (a) Western blot results showed that mouse oocytes expressed HIF-1α at different maturation stages (GV, GVBD, MI, and MII). (b) Digital image correlation (DIC) images of control oocytes and Bay87-2243 treated oocytes after 14 h of culture. Bar = 80 μm. (c) The rate of polar body extrusion after 14 h of culture in the control group and Bay87-2243 treatment group. *** Significant difference (p < 0.001). (d) Western blot was used to analyze the inhibition efficiency of Bay87-2243 on HIF-1α protein expression. HIF-1α protein intensity analysis. ** Significant difference (p < 0.01).

Loss of HIF-1α activity causes mitochondrial dysfunction in oocytes

-

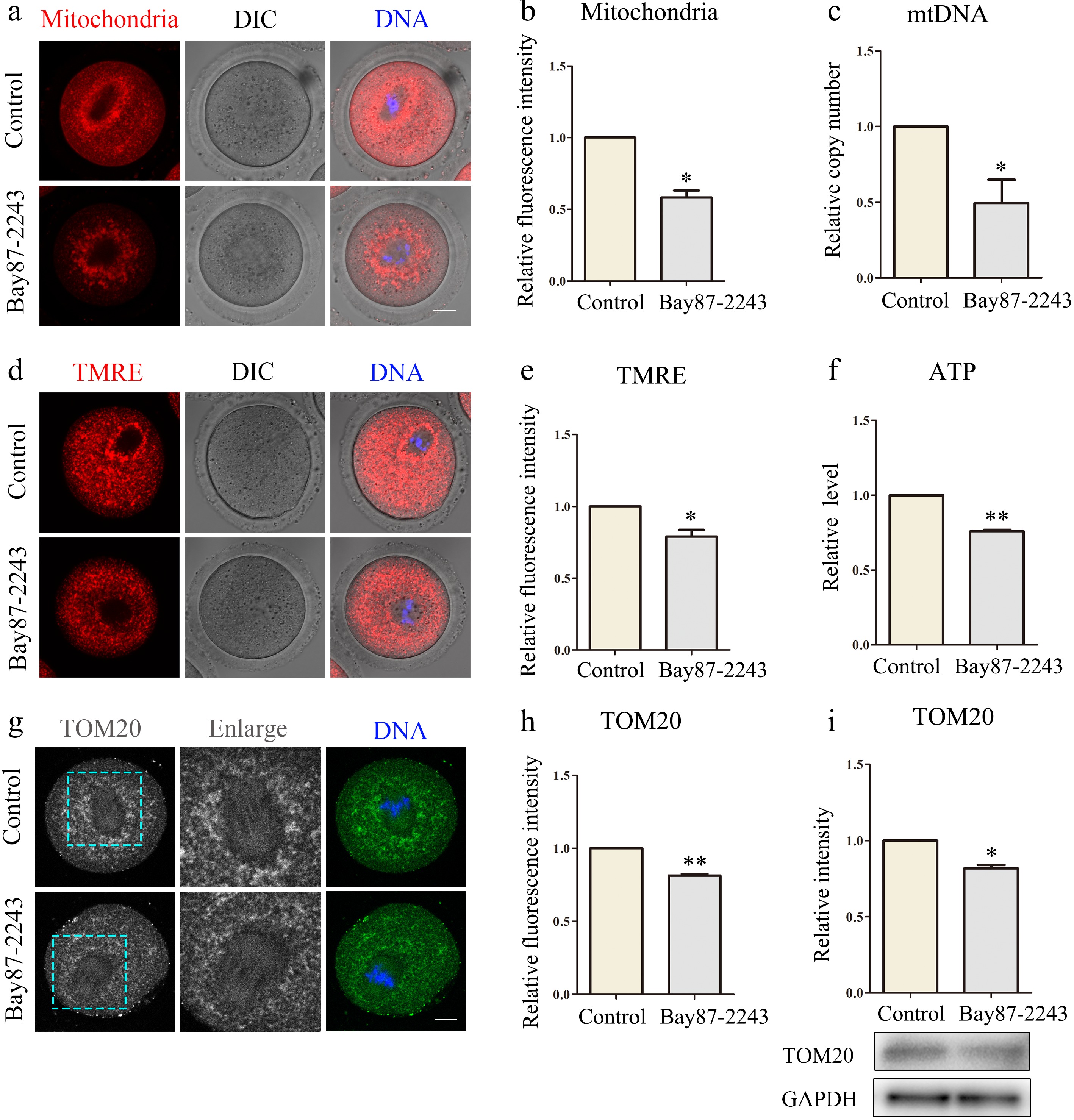

During oocyte maturation, mitochondria generate ATP, a crucial energy source essential for supporting successful oocyte development. Consequently, we investigated the impact of HIF-1α deficiencies on mitochondria during the oocyte maturation process. We observed that mitochondria in the control group oocytes displayed a strong Mito-Tracker signal, whereas the signal in the treated group was notably weaker (control group, 1.0 ± 0.0, n = 32; treatment group, 0.58 ± 0.09, n = 42, p < 0. 05; Fig. 2a, b). MtDNA copy number can mirror the quantity of mitochondria present within an oocyte. As detected by the assay, the relative copy number of oocytes inhibited by HIF-1α was significantly decreased compared with the control group (control group, 1.0 ± 0.0, n = 45; treatment group, 0.50 ± 0.34, n = 45, p < 0.05; Fig. 2c). A normal mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) serves as one of the crucial indices for sustaining the normal physiological functions of mitochondria. MMP was measured through TMRE staining. The obtained results indicated that the oocytes with inhibited HIF-1α displayed a weaker TMRE signal in contrast to those in the control group (control group, 1.0 ± 0.0, n = 41; treatment group, 0.79 ± 0.09, n = 36, p < 0.05; Fig. 2d, e). Finally, we examined the ATP level of the cells. The results revealed a significant reduction in ATP levels in the experimental group (control group, 1.0 ± 0.0, n = 35; treatment group, 0.81 ± 0.02, n = 35, p < 0.01; Fig. 2f). Tom20, located on the outer mitochondrial membrane, plays a key role in assessing mitochondrial state and function. Immunofluorescence and western blot results indicated that the fluorescence signal of TOM20 in the experimental group decreased remarkably (control group, 1.0 ± 0.0, n = 33; treatment group, 0.81 ± 0.02, n = 32, p < 0.01; Fig. 2g, h), along with a significant reduction in the expression level of TOM20 protein (control group, 1.0 ± 0.0, n = 150; treatment group, 0.79 ± 0.05, n = 150, p < 0.05; Fig. 2i). These results confirm that when HIF-1α was inhibited by Bay87-2243, the function of oocyte mitochondria was affected.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of HIF-1α impairs mitochondrial function in oocytes. (a) Typical map of mitochondrial distribution of oocytes in control group and Bay87-2243 treatment group. Red, mitochondria; blue, DNA. Bar = 20 μm. (b) Relative fluorescence intensity of mitochondrial signal after Bay87-2243 treatment. (c) The relative mtDNA copy number was evaluated in both control and Bay87-2243 treatment oocytes. (d) Typical graphs of TMRE in control and Bay87-2243 treatment groups. Red, TMRE; blue, DNA. Bar = 20 μm. (e) Relative fluorescence intensity of TMRE in the control group and Bay87-2243 treatment group. (f) The relative ATP levels were measured in both the control and Bay87-2243 treatment groups. (g) Typical graphs of TOM20 in control and Bay87-2243 treatment groups. Green, TOM20; blue, DNA. Bar = 20 μm. (h) Relative fluorescence intensity of TOM20 in control group and Bay87-2243 treatment group. (i) Western blot was used to detect the expression of TOM20 protein in the control group and Bay87-2243 treatment group. * Significant difference (p < 0.05); ** Significant difference (p < 0.01).

Loss of HIF-1α activity leads to abnormal mitochondrial dynamics in oocytes

-

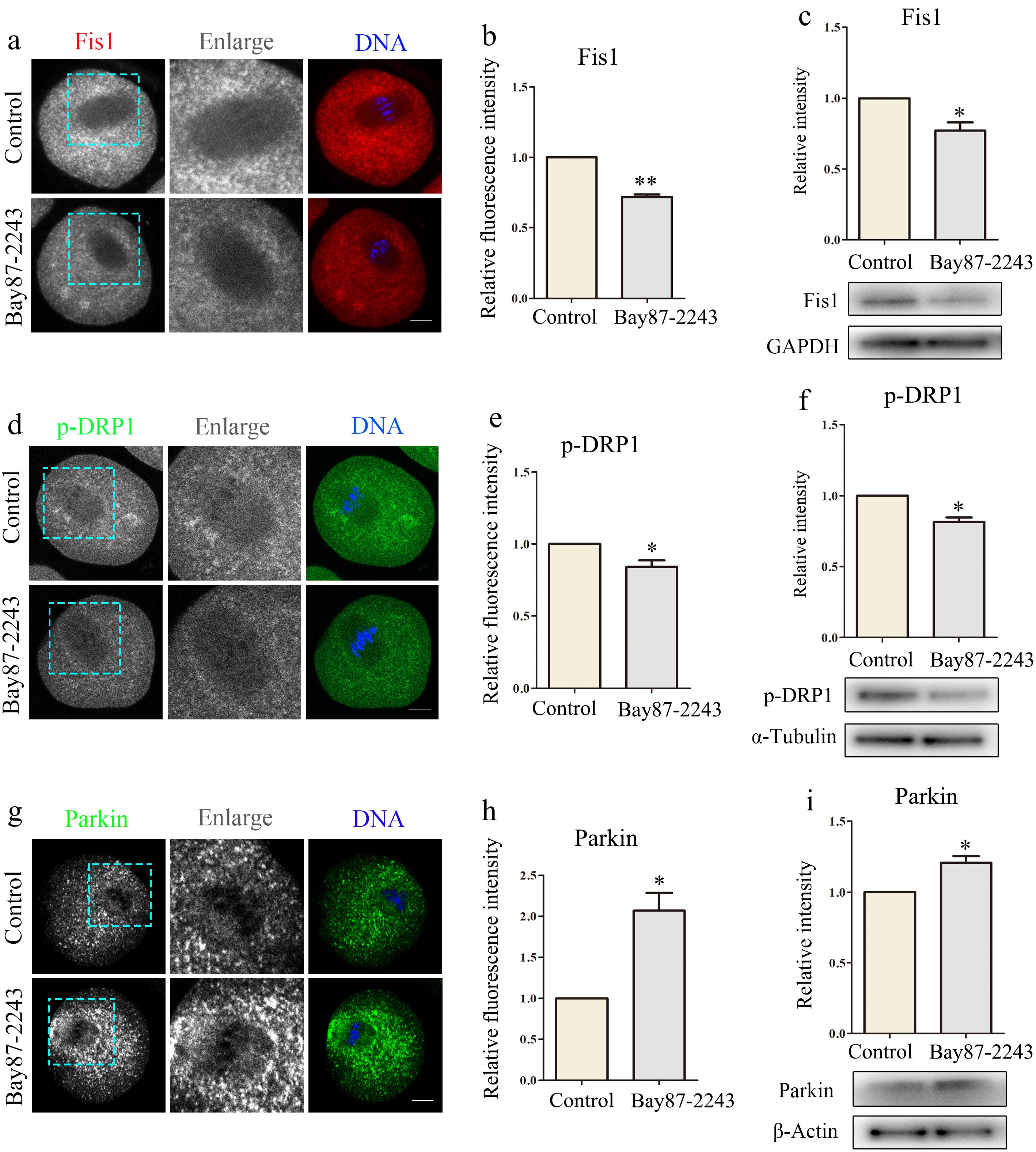

Mitochondria are in the process of dynamic changes in cells. Through continuous division and fusion, mitochondria provide energy for cells and regulate cell autophagy, signal transduction, and apoptosis. Fis1 locates at the mitochondrial outer membrane, and facilitates mitochondrial fission. Therefore, in this experiment, Fis1 levels were detected by immunofluorescence and immunoblotting. The results indicated a notable reduction in the Fis1 signal in the experimental group (control group, 1.0 ± 0.0, n = 36; treatment group, 0.72 ± 0.03, n = 32, p < 0.01; Fig. 3a, b), and the protein expression level was also markedly decreased (control group, 1.0 ± 0.0, n = 33; treatment group, 0.78 ± 0.10, n = 29, p < 0.05; Fig. 3c). DRP1 can also mediate mitochondrial fission and regulate mitophagy to ensure cell health. P-DRP1 levels were measured by immunofluorescence and immunoblotting. The results demonstrated a significant decline in p-DRP1 signal within the experimental group cells (control group, 1.0 ± 0.0, n = 33; treatment group, 0.83 ± 0.13, n = 31, p < 0.05; Fig. 3d, e), and the protein expression level was also significantly decreased (control group, 1.0 ± 0.0, n = 150; treatment group, 0.81 ± 0.06, n = 150, p < 0.05; Fig. 3f). Thus, inhibition of HIF-1α leads to abnormal mitochondrial dynamics in oocytes. Mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy interact and regulate each other. Parkin, an E3 ubiquitin ligase situated in the cytoplasm, assumes a pivotal function in the process of mitophagy. Parkin levels were measured by immunofluorescence and immunoblotting. The results showed that Parkin signal (control group, 1.0 ± 0.0, n = 31; treatment group, 2.07 ± 0.43, n = 30, p < 0.05; Fig. 3g, h) and protein expression levels (control group, 1.0 ± 0.0, n = 150; treatment group, 1.21 ± 0.09, n = 150, p < 0.05; Fig. 3i) were significantly increased in the experimental cells. Therefore, inhibition of HIF-1α leads to mitophagy in oocytes.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of HIF-1α leads to abnormal mitochondrial dynamics in oocytes. (a) Typical graphs of Fis1 in control and Bay87-2243 treatment groups. Red, Fis1; blue, DNA. Bar = 20 μm. (b) Relative fluorescence intensity of Fis1 in control group and Bay87-2243 treatment group. (c) Western blot was used to detect the expression of Fis1 protein in the control group and Bay87-2243 treatment group. (d) Typical graphs of p-Drp1 in control and Bay87-2243 treatment groups. Green, p-Drp1; blue, DNA. Bar = 20 μm. (e) Relative fluorescence intensity of p-Drp1 in control group and Bay87-2243 treatment group. (f) Western blot was used to detect the expression of p-Drp1 protein in the control group and Bay87-2243 treatment group. (g) Typical graphs of Parkin in control and Bay87-2243 treatment groups. Green, Parkin; blue, DNA. Bar = 20 μm. (h) Relative fluorescence intensity of Parkin in control group and Bay87-2243 treatment group. (i) Western blot was used to detect the expression of Parkin protein in the control group and Bay87-2243 treatment group. * Significant difference (p < 0.05); ** Significant difference (p < 0.01).

Loss of HIF-1α activity induces oxidative stress and apoptosis in oocytes

-

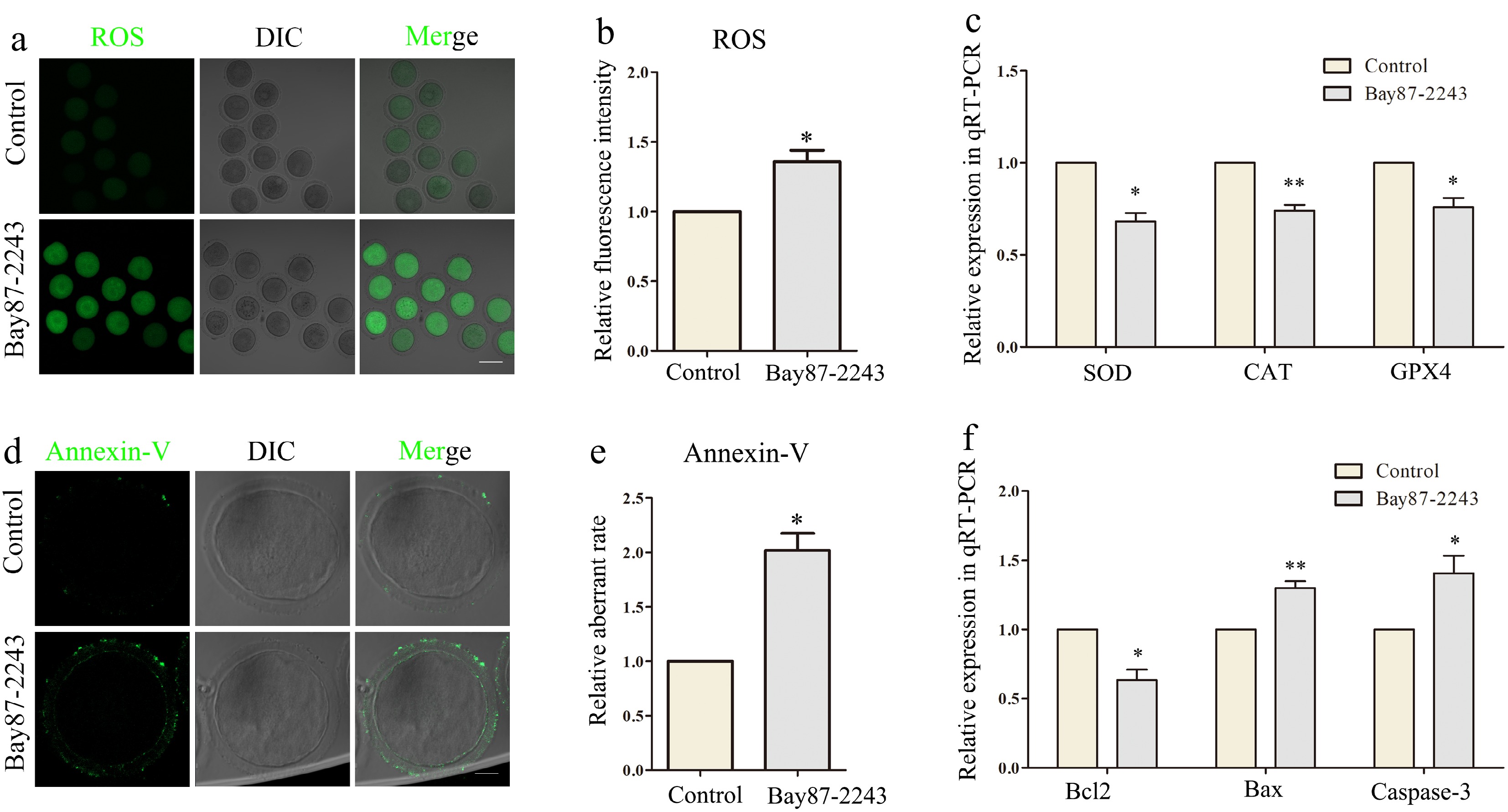

Mitochondria generate ROS when they undergo oxidative phosphorylation, which is the main pathway for intracellular ROS production. Mitochondria can maintain ROS homeostasis under normal conditions, but dysfunctional mitochondrial function has the potential to trigger oxidative stress. Initially, we quantified ROS levels in oocytes after HIF-1α suppression. As shown in Fig. 4a, the experimental group exhibited a markedly stronger ROS signal intensity compared to the control group (control group, 1.0 ± 0.0, n = 31; treatment group, 1.36 ± 0.15, n = 31, p < 0.05; Fig. 4b). Subsequently, using qPCR and other techniques, the expression levels of relevant genes were analyzed, revealing that HIF-1α inhibition led to a notable reduction in the expression of SOD, CAT, and GPX4 (Fig. 4c). This implies that when HIF-1α is inhibited, it leads to the occurrence of oxidative stress in oocytes. As the level of ROS increases, it may lead to apoptosis by affecting the normal function of mitochondria. Therefore, Annexin-V reagent was used to detect whether the cells underwent early apoptosis. The findings indicated a significantly increased likelihood of apoptosis in the experimental group compared to the control group (control group, 1.0 ± 0.0, n = 30; treatment group, 2.02 ± 0.31, n = 32, p < 0.05; Fig. 4d, e). Subsequently, qPCR and other methods were used to detect the expression levels of related genes. The results showed that after inhibiting HIF-1α, the expression level of BCL2 significantly decreased, while the expression levels of BAX and Caspase-3 significantly increased (Fig. 4f). These results suggest that inhibition of HIF-1α leads to early apoptosis in oocytes and further confirm that HIF-1α performs an essential role in oocyte maturation.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of HIF-1α induces oxidative stress and apoptosis of oocytes. (a) The reactive oxygen species (ROS) level in the control and Bay87-2243 treatment groups of oocytes. Green, ROS. Bar = 80 μm. (b) Relative fluorescence intensity of ROS in control group and Bay87-2243 treatment group. (c) Effects of HIF-1α on expression of the several oxidative stress‐related genes in oocytes. The levels of SOD, CAT, and GPX4 expression in the Bay87-2243 treated oocytes decline than the control oocytes. (d) Annexin‐V signals in the control and Bay87-2243 treatment group oocytes. Green, Annexin‐V. Bar = 20 μm. (e) Relative fluorescence intensity of Annexin‐V in control group and Bay87-2243 treatment group. (f) Effect of HIF-1α on the expression of several apoptosis-related genes in oocytes. The expression levels of Bcl2, Bax, and Caspase-3 increased in oocytes treated with Bay87-2243 compared with the control group. * Significant difference (p < 0.05); ** Significant difference (p < 0.01).

Loss of HIF-1α activity increases the level of autophagy in oocytes

-

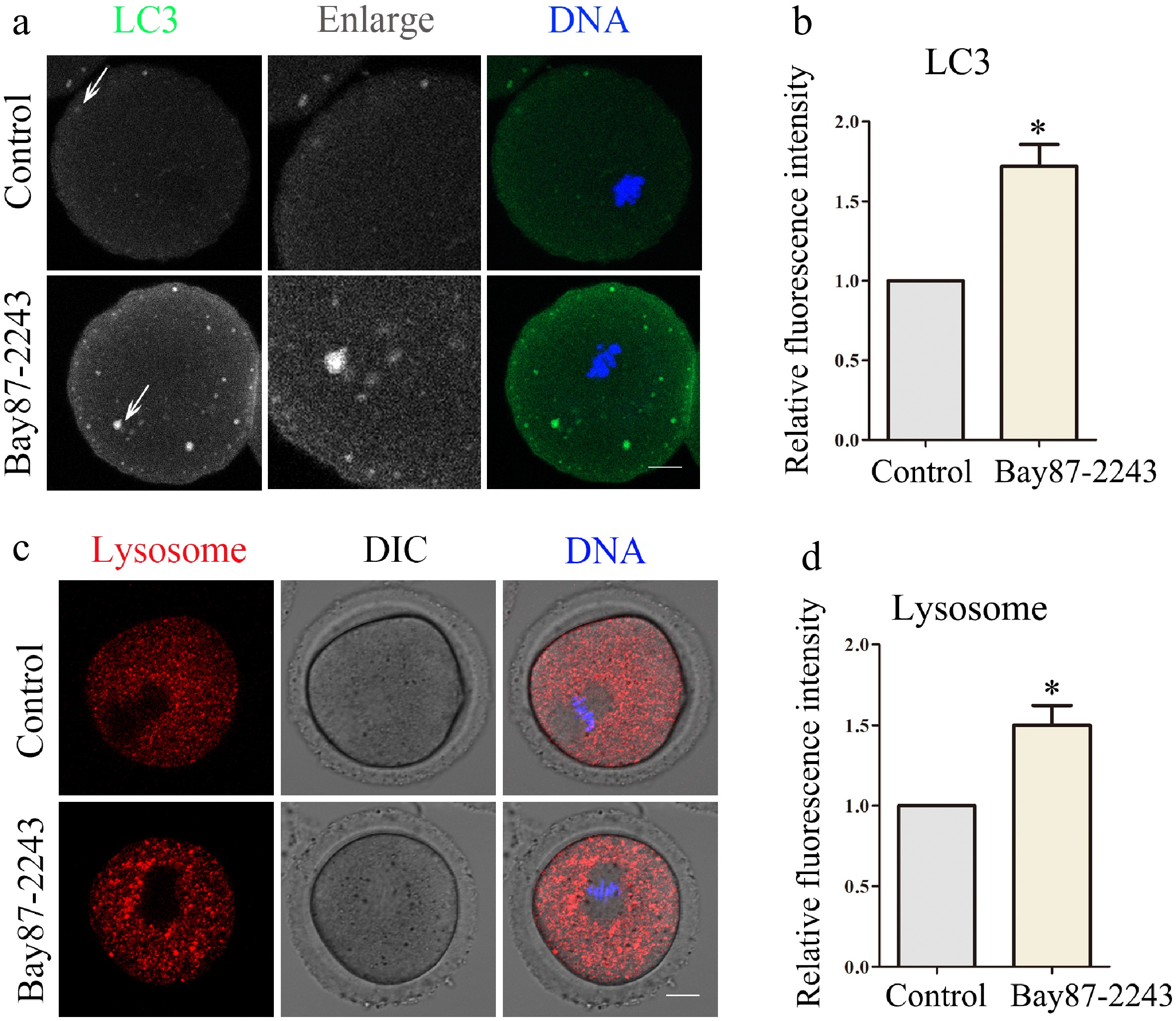

Subsequently, we investigated the impact of HIF-1α inhibition on autophagy. The expression level of LC3 protein can reflect the level of autophagy. Therefore, the expression level of LC3 was detected by immunofluorescence staining to explore whether inhibition of HIF-1α caused autophagy. As shown in Fig. 5a, in the control group, the LC3 signal was evenly dispersed across the oocyte cortex, while the experimental group exhibited noticeable aggregation. Analysis of LC3 protein immunofluorescence intensity demonstrated a significant rise in relative fluorescence intensity in oocytes after HIF-1α inhibition (control group, 1.0 ± 0.0, n = 31; treatment group, 1.77 ± 0.22, n = 28, p < 0.05; Fig. 5b). Lysosomes can remove useless biological macromolecules and senescent organelles in oocytes, which is closely associated with the cellular autophagy process. Therefore, subsequent experimental investigations were conducted to examine the functional consequences of HIF-1α suppression on lysosomal activity. The lysosomal compartment dynamics in meiotic stage I oocytes were monitored using lyso-tracker-based fluorescent imaging techniques. Results demonstrated that the lyso-tracker signal exhibited a remarkable increase in the oocytes of the experimental group. Moreover, the results of the statistical analysis revealed a notable increase in the relative fluorescence intensity within the experimental group (control group, 1.0 ± 0.0, n = 34; treatment group, 1.53 ± 0.33, n = 33, p < 0.05; Fig. 5c, d). These data suggested HIF-1α activity was essential for lysosome-related autophagy.

Figure 5.

Inhibition of HIF-1α impairs oocyte autophagy and lysosomal function. (a) Typical graphs of LC3 in control and Bay87-2243 treatment groups. Green, LC3; blue, DNA. Bar = 20 μm. (b) Relative fluorescence intensity of LC3 in control group and Bay87-2243 treatment group. (c) Typical graphs of lysosome in control and Bay87-2243 treatment groups. Green, Lysosome; blue, DNA. Bar = 20 μm. (d) Relative fluorescence intensity of lysosome in control group and Bay87-2243 treatment group. * Significant difference (p < 0.05).

-

This study investigated the functional role of HIF-1α in mammalian oocyte development and maturation during in vitro culture under normoxic conditions. HIF-1α might be involved in regulating oocyte maturation through its impact on mitochondrial function. Under normoxic conditions, when the protein abundance of HIF-1α is inhibited, the function and dynamics of mitochondria in oocytes are disrupted. This disruption gives rise to oxidative stress and the early apoptosis of oocytes. Additionally, it causes an increase in autophagy, leading to a decline in the oocytes' polar body extrusion rate.

In most cases, HIF-1α initially amasses in the cytoplasm. Subsequently, it transfers into the nucleus where it binds to HIF-1β. This binding event results in the formation of a dimer, which further assembles into the HIF-1 complex. By doing so, the complex can regulate the expression of relevant genes, thus ensuring the normal functioning of cells[22]. In addition, HIF-1α can also interact with a number of other proteins, participate in cell signaling and metabolic regulation, or play a non-transcription factor function in certain cellular processes[23]. To investigate the functional role of HIF-1α during meiotic progression in mammalian female gametes, we carried out an experiment where we incubated the oocytes with the HIF-1α inhibitor Bay87-2243. Experimental analyses demonstrated that the first polar body ejection rate of oocytes was inhibited after treatment with both 2.5 and 5 μM inhibitors, indicating that suppression of HIF-1α activity can affect the meiotic process of oocytes and lead to decreased oocyte quality. These results supported previous findings that HIF-1α regulates oocyte maturation[24].

We then investigate the way of HIF-1α on polar body extrusion from oocytes. HIF-1α and mitochondria are closely interrelated, and HIF-1α can regulate mitochondrial metabolism through a variety of mechanisms to adapt to the energy demand of cells[25]. The results showed that inhibition of HIF-1α caused mitochondrial abnormalities, decreased mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) level, mitochondrial copy number, and ATP production. This is consistent with previous findings that HIF-1α can affect mitochondrial function. Research findings have indicated that HIF-1α can enhance mitochondrial respiration. It accomplishes this through modulating the expression of elements in the mitochondrial electron transport chain, particularly complexes such as cytochrome c oxidase within the mitochondria[26]. For example, a steady manifestation of HIF-1α in knockout human foreskin fibroblasts increased the mRNA and protein levels of cytochrome c oxidase 4-2 (COX4-2)[27]. In addition, HIF-1α can activate the mitochondrial outer membrane receptor protein BNIP3 mediated mitophagy pathway, promote mitophagy, and maintain cell energy metabolism and mitochondrial homeostasis[28]. For instance, in the studies regarding acrylonitrile-induced neurotoxicity, the activation of HIF-1α remarkably alleviated mitochondrial dysfunction[29]. Relevant studies have shown that the increased expression of HIF-1α can promote the expression of mitochondrial autophagy-related protein Parkin, thus enhancing mitochondrial autophagy, which is specifically reflected in the fact that HIF-1α can bind to the hypoxia response element (HRE) in the promoter region of Parkin gene. Thus, the transcription of the Parkin gene and the expression of the Parkin protein was promoted[30]. Mitochondrial function and mitochondrial dynamics are intricately linked. Their coordinated operation is crucial for upholding cellular homeostasis. We found that mitochondrial dynamics was also abnormal after HIF-1α inhibition, showing aberrant Fis1, DRP1 expression, and localization. This is consistent with existing findings that DRP1 is a key target of HIF-1α in regulating mitochondrial function, and by up-regulating the expression of DRP1, it promotes mitochondrial division and then affects the energy metabolism of cells[31]. For instance, within a pulmonary fibrosis model, Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission modulates lipid metabolic reprogramming via the ROS/HIF-1α pathway which impacts cell proliferation and apoptosis[32]. In the glucose deprivation hypoxia/restoration model, HIF-1α activation has been demonstrated to enhance Drp1 transcriptional activity through the Akt signaling pathway, leading to increased mitochondrial fission[33]. FIS1 is also a key protein in mitochondrial division, and the binding site of its gene promoter region can interact with HIF-1α to affect the transcription of the FIS1 gene and thus affect the expression of the FIS1 protein[34]. In addition, HIF-1α can also regulate the dynamic changes of mitochondria by up-regulating the expression of HO-1 (heme oxygenase-1). The up-regulation of HO-1 can inhibit the expression of FIS1, and the reduction of its expression helps to reduce the excessive division of mitochondria and maintain the normal morphology and function of mitochondria, thus alleviating cell damage[35]. Therefore, HIF-1α may affect oocyte development by affecting mitochondrial function and dynamics.

Dysfunction of mitochondria may result in a decline in the ability of oocytes to clear ROS, resulting in the dysregulation of cellular redox homeostasis, leading to the occurrence of oxidative stress[36]. We examined the alterations in ROS levels within oocytes after the inhibition of HIF-1α activity. Our findings revealed that a deficiency in HIF-1α led to enhanced oxidative stress. A significant reduction was observed in the expression of key antioxidant-related genes, including superoxide SOD, CAT, and GPX4. Previous studies have documented the involvement of HIF-1α in cellular responses to redox imbalance: HIF-1α can promote glycolytic metabolism and reduce mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, thereby reducing ROS generation[37]. And HIF-1α can further reduce ROS generation by inhibiting mitochondrial complex I activity[38]. HIF-1α can also regulate the number of mitochondria by inhibiting peroxisome proliferation receptor-γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α), thus diminishing the generation of ROS[39]. Moreover, experimental observations revealed that suppressing HIF-1α activity led to a substantial increase in oocyte apoptosis, accompanied by notable changes in genetic markers associated with apoptosis pathways. The cellular apoptotic mechanisms appeared to be triggered by reactive oxygen species reaching critical threshold levels[40]. Research evidence indicates that HIF-1α demonstrates protective effects against cellular redox imbalance by upregulating antioxidant genes such as HO-1, thereby inhibiting apoptosis[41]. In summary, HIF-1α is crucial for maintaining the redox equilibrium and suppressing apoptosis within oocytes.

Subsequent investigations revealed that suppressing HIF-1α activity resulted in markedly enhanced autophagic activity in female gametes, with this increase being accompanied by abnormal lysosomal function. Autophagy serves as a vital cellular mechanism for preserving homeostasis, as it entails the degradation of damaged organelles and proteins. However, overactivation of autophagy has the potential to trigger cell self-digestion and the subsequent impairment of cellular functions. HIF-1α exerts a multifaceted regulatory function during the autophagy process. The specific underlying mechanisms have been delved into in numerous research investigations. Research findings have indicated that HIF-1α can influence the autophagy level through the regulation of BNIP3 expression. As a crucial transcriptional target of HIF-1α, BNIP3 upregulation has been demonstrated to facilitate mitochondrial autophagy processes. In some cases, HIF-1α is also capable of decreasing the autophagy level via the inhibition of BNIP3 expression, thus maintaining cellular homeostasis[42]. In some cells, HIF-1α can also indirectly inhibit excessive autophagy by activating the mTOR signaling pathway to avoid cell damage caused by excessive autophagy when the intracellular energy level is high[43]. As the degradation center in cells, lysosomes are crucial in the autophagy process. Lysosomes act as the ultimate effectors in the autophagy process. They are tasked with degrading the substrates encapsulated by autophagosomes. Moreover, they play a crucial regulatory part in the development of oocytes[44]. Studies have found that HIF-1α can affect cell metabolism and autophagy efficiency by regulating the function and localization of lysosomes. HIF-1α can directly negatively regulate the ATP6V1A gene, which is a key component in maintaining lysosomal homeostasis and encodes a key subunit of the V-ATPase complex. When the expression of ATP6V1A is inhibited, the acidic environment in the lysosome will be destroyed, the pH value of the lysosome will increase, the volume of the lysosome will increase, and the localization of the lysosome will be abnormal[45]. The abnormal lysosome localization will directly affect the fusion efficiency of autophagosome and lysosome, resulting in impaired autophagy function. The abnormal autophagy function will further affect the location and function of lysosomes, forming a vicious cycle and causing damage to cell development[46].

-

Our study findings suggested that inhibition of HIF-1α caused oocyte maturation disorders, which may be through inducing abnormalities in mitochondrial function and dynamics, leading to oxidative stress and early apoptosis, and increasing autophagy in oocytes.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32370908), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China (KYT2024002, KJJQ2025001, RENCAI2024011).

-

All procedures were reviewed and preapproved by the Nanjing Agricultural University (Identification No.NJAULLSC2022070, approval date: 2022/8/1). The experimental protocol strictly adhered to the 3R principles (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement) for ethical animal research.

-

All contributing researchers have made substantial intellectual inputs to this manuscript through the following specific activities: study conception and experimental framework development: Sun SC, Wang Y, Pan WL; experimental data acquisition and documentation: Pan WL, Ma RJ; analysis and interpretation of results: Pan WL, Hou YX; manuscript preparation: Pan WL. Each author reviewed the outcomes and consented to the final form of the manuscript.

-

The data underpinning the outcomes of this research can be accessed from the corresponding author when a reasonable request is submitted.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. Professor Shao-Chen Sun is the Editorial Board member of Animal Advances who was blinded from reviewing or making decisions on the manuscript. The article was subject to the journal's standard procedures, with peer-review handled independently of this Editorial Board member and the research groups.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Pan WL, Ma RJ, Hou YX, Wang Y, Sun SC. 2025. HIF-1α regulates mitochondria function for oxidative stress and autophagy during oocyte maturation. Animal Advances 2: e014 doi: 10.48130/animadv-0025-0014

HIF-1α regulates mitochondria function for oxidative stress and autophagy during oocyte maturation

- Received: 24 February 2025

- Revised: 25 March 2025

- Accepted: 28 March 2025

- Published online: 23 May 2025

Abstract: Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) serves as a crucial transcription factor that is pivotal in regulating the cellular response to low-oxygen conditions, and it is also involved in multiple cellular processes under normoxic conditions. During follicular development, oocyte maturation requires massive energy which leads to oxygen decrease and forms physiological hypoxia. HIF-1α is activated to ensure the adaption of follicles to the hypoxic environment and maintain normal development. In the current research, we explored the impacts of HIF-1α activity on oocyte maturation. The findings indicated that the suppression of HIF-1α led to defects in oocyte polar body extrusion. Additionally, mitochondrial dysfunction was detected, manifested by a reduction in mitochondrial membrane potential, the number of mitochondria, and ATP production. Further analysis showed that HIF-1α affected Fis1 and DRP1 for mitochondria dynamics, which further induced Parkin-related mitophagy. This led to a further elevation in ROS levels, thereby causing oxidative stress and triggering early apoptosis. Moreover, the autophagy level in oocytes increased, and at the same time, there are abnormalities in lysosomes. Overall, our findings indicated that HIF-1α maintains oocyte homeostasis and developmental potential by regulating redox balance, mitochondrial function, apoptosis, and autophagy-lysosomal pathways for meiotic maturation.

-

Key words:

- HIF-1α /

- Oocyte /

- Mitochondria /

- Oxidative stress /

- Autophagy