-

Poultry production has significant potential to improve livelihoods, particularly in rural areas, due to the advantages of raising chickens and the relative ease of enhancing productivity[1]. As a sector of animal agriculture, poultry farming enables rapid food production, requires minimal initial capital investment, and can efficiently utilize available household labor[2]. Moreover, it is characterized by short generation intervals and high efficiency in converting nutrients into high-quality animal proteins. Therefore, improving poultry productivity is essential to meet the growing demand for animal protein sources.

The major challenges in poultry production, regardless of the system or location, are the availability, quality, and cost of feed ingredients[3]. Feed costs typically constitute approximately 60%–65% of the total expenses in poultry farming, with protein accounting for around 13% of the total feed cost[4]. A feasible approach to address this issue is incorporating agricultural and aquatic byproduct wastes that humans do not directly consume. Investigating the potential of these feed resources, which are cheaper, locally available, and offer nutritional values comparable to conventional protein sources, is crucial. Such alternative feeds for poultry can significantly reduce feed costs, mitigate waste disposal challenges, and alleviate competition for food with humans[5,6]. Optimal cost reduction can be achieved by developing diet formulations that utilize alternative, locally available ingredients.

Fish waste meal (FWM) is a byproduct used as a protein supplement in poultry feed. More than 70% of the total fish catch undergoes further processing before reaching the market[7], resulting in the generation of substantial quantities (approximately 20%–80%) of fish waste, depending on the level of processing (e.g., gutting, scaling, filleting), and fish species. Each species has distinct characteristics in terms of composition, size, shape, and inherent chemistry[8,9]. Fish byproducts are nutritionally significant and contain proteins, fatty acids (FAs), and minerals similar to those found in fish fillets and other foods consumed by humans. Research on meagre and gilthead sea bream species indicates that the skin is a major protein source, while trimmings and bones are rich in calcium, and the head, intestines, and bones contain substantial lipids[10]. These processing activities result in various discards, including muscle trimmings (15%–20%), skin and fins (1%–3%), bones (9%–15%), heads (9%–12%), viscera (12%–18%), and scales (5%)[11].

To address the growing demand for fast food and to remain competitive with the broiler and layer industries, fish waste and byproducts can be converted into additives for poultry feed. This could enhance eggs' omega-3 FA content and improve growth and carcass characteristics. Several studies have reported significant results regarding using fish waste and byproducts as additives in poultry feed, particularly regarding growth, egg quality, blood biochemistry, and carcass characteristics. This review aims to provide further insights into the potential use of fish waste and byproducts in poultry production and their effects on growth performance, egg quality, blood biochemistry, and carcass characteristics.

-

The term 'byproduct' refers to something that is not typically considered a saleable product but can be utilized after processing. At the same time, 'waste' denotes unfit materials for feed or food purposes and must be composted or disposed of[12]. The EC regulation of animal byproducts (EC No. 1774/2002) defines these byproducts as whole or partial animal bodies or products that are considered unsuitable for human consumption. Although terms such as co-streams, co-products, discards, and waste are often used interchangeably, 'waste' generally implies material with no value[13]. Various terms such as 'byproduct', 'co-product', 'fish waste', 'fish offal', 'fish visceral mass', and 'fish discards' are used to describe non-edible parts of seafood processing[12]. Stevens[14] defined byproducts as all edible or non-edible materials that remain after the main products are prepared. Common byproducts of finfish include frames (bones with attached flesh), trimmings, blood, head, skin, and viscera (guts). The fractions of byproducts as a percentage of the total wet weight of Atlantic salmon are reported as heads (10%), belly flaps (1.5%), skin (3.5%), viscera (12.5%), frames (10%), trimming (2%), and blood (2%)[14].

Proteins/amino acid composition

-

Fish frames are rich in highly nutritious and easily digestible proteins, which can be extracted through enzymatic hydrolysis instead of being discarded as waste[15]. Fish-derived proteins provide a more balanced profile of essential dietary amino acids than alternative animal protein sources, making them nutritionally superior to plant-based proteins[16]. However, fish muscle proteins are more heat-sensitive than mammals[17,18]. Additionally, proteins from cold-water fish are more prone to denaturation than tropical fish proteins. Fish byproducts, including fish meal, protein hydrolysates, and silage, offer a rich and diverse amino acid profile beneficial for animal nutrition. The amino acid composition includes essential and non-essential amino acids crucial for growth, tissue repair, immune function, and overall health. These include lysine (6–8 g/100 g), important for protein synthesis, growth, and immunity; methionine (2.5–3.5 g/100 g), key for protein synthesis and enzyme activity; threonine (4–5 g/100 g), vital for gut health and metabolism; leucine (5–7 g/100 g) and valine (4–5 g/100 g), branched-chain amino acids essential for muscle synthesis and energy; lsoleucine (4–5 g/100 g), supporting muscle recovery and immunity; histidine (2–3 g/100 g), crucial for histamine production and red blood cell growth; and phenylalanine (3–4 g/100 g), a precursor for tyrosine, involved in hormone production[19].

Non-essential amino acids like glutamic acid (13–18 g/100 g), the most abundant in fish byproducts, support energy production and protein synthesis. Aspartic acid (9–11 g/100 g) aids metabolism and energy, while alanine (4–5 g/100 g) is key for muscle tissue energy. Arginine (5–7 g/100 g) supports nitrogen metabolism and immunity, and glycine (2–3 g/100 g) is vital for collagen and detoxification. Serine (4–6 g/100 g) aids protein metabolism, and proline (3–4 g/100 g) is important for collagen and tissue repair[20]. These amino acids contribute significantly to animal health and growth.

Bioactive peptides

-

Proteins extracted from fish muscle contain numerous peptides with various bioactivities, including antihypertensive, antithrombotic, immunomodulatory, and antioxidative properties[17]. These bioactive peptides have anticoagulant and antiplatelet properties that inhibit coagulation factors in the intrinsic pathway[17]. Fish muscle proteins, resulting from enzymatic hydrolysis, possess diverse functional and nutritional attributes, including generating numerous physiologically active peptides[21].

Collagen and gelatin

-

Fish skin waste is a valuable source of collagen and gelatin, widely used in biomedical, food, and cosmetic industries. Collagen, a structural protein in connective tissues like skin, tendons, and ligaments, provides strength and elasticity. Both freshwater and marine fish, including species such as tilapia, catfish, and cold-water fish, are rich in collagen, which contains essential amino acids such as glycine (25%–30%), proline (15%–20%), and hydroxyproline (10%–15%), crucial for maintaining skin hydration, elasticity, and overall health[22]. Gelatin, a partially hydrolyzed form of collagen, differs from fish muscle proteins due to its high concentration of non-polar amino acids like alanine, glycine, proline, and valine, making it highly beneficial for various applications[21]. Additionally, gelatin extracted from fish skin exhibits superior biological activities, including antioxidant and antihypertensive properties, attributed to its unique glycine-proline-alanine repeating sequence[17].

Hydrolysis converts collagen into gelatin, breaking it down into smaller peptides. Fish gelatin, derived from freshwater and marine species, offers numerous advantages, including enhanced bioactivity, antioxidant properties, and a lower risk of disease transmission than mammalian-based gelatin[23]. This makes it ideal for use in food products such as jellies, gummy candies, and marshmallows, as well as in pharmaceutical capsules and dietary supplements. Moreover, using fish byproducts for collagen and gelatin production promotes sustainability by reducing waste and adding economic value to the fish processing industries. Overall, collagen and gelatin from fish waste are highly versatile, providing significant economic and environmental benefits across multiple industries.

Enzymes

-

Fish waste and byproducts contain various enzymes, such as proteases, lipases, and carbohydrase, which are important for enhancing the nutritional value of animal feeds, including poultry diets[24]. These enzymes break down proteins, fats, and carbohydrates in fish byproducts, improving their digestibility and nutritional profile[25]. The enzyme content and activity levels vary between marine and freshwater fish species, as their dietary habits and physiological characteristics differ[26]. Enzyme concentrations in fish waste from marine fish typically range from 3% to 5% of the total protein content[27]. Oily marine fish, with their fat and protein-rich tissues, tend to have higher lipase and protease levels, with lipase activity ranging from 4 to 6 units/mg protein[28].

In contrast, enzyme activity in freshwater fish waste generally ranges from 2% to 4% of total protein content[29]. Freshwater fish have lower lipase levels but significant protease activity, and carbohydrase activity is more pronounced due to their mixed diet. For example, tilapia has about 5 units/mg of protein protease activity, while lipase activity is lower than marine fish[30].

Minerals

-

Fish waste, including skin, bones, and scales, contains a rich mineral valuable for various applications. The mineral composition of fish byproducts varies slightly between freshwater and marine species, but both provide essential elements necessary for human and animal nutrition. Common minerals found in fish waste include calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, potassium, and trace elements like iodine, selenium, and iron. The mineral content typically ranges from 10% to 20%, with calcium and phosphorus being the most abundant, contributing to the strength and structure of bones and scales. In particular, calcium and phosphorus are vital for bone health and are often utilized in animal feed and fertilizers[31].

In terms of inclusion, the level of mineral content in fish byproducts is influenced by species, processing methods, and the specific byproduct (e.g., fish meal, fish silage, or fish oil). Marine fish, particularly cold-water species like salmon, are often richer in certain minerals such as iodine and selenium. In contrast, freshwater fish like tilapia and catfish tend to have higher levels of calcium and phosphorus[32]. Including fish byproducts in animal feed or fertilizers provides these essential minerals and contributes to sustainability by reducing waste and utilizing materials from the fishing industry. Moreover, using fish byproducts with a high mineral content helps to add nutritional value to animal diets and agricultural soil, making fish waste a valuable resource in both environmental and economic terms.

FA composition

-

Various fish byproducts are recognized as promising sources of FAs. Among these, fish byproducts, which contain high proportions of FAs, have been extensively studied. They affect neurological and immune systems, which are necessary for maintaining appropriate brain function. The primary type of FA varies by food type, with fish being rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), such as eicosatetraenoic acid (EPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)[33]. Many studies have shown that fish byproducts, including liver, viscera, trimmings, skin, head, and eyeballs, are rich in omega-3 FAs (EPA and DHA), which have positive health benefits[34].

Fish byproducts, particularly fish oil, are rich in essential FAs beneficial for animals and humans. The FA composition of fish waste and byproducts typically includes EPA (10%–20% of total FAs), which helps reduce inflammation, supports cardiovascular health and promotes brain function; DHA (10%–15%), important for brain health, eye development, and cognitive function; and arachidonic acid (AA) (1%–5%), involved in inflammatory responses and immune function regulation[34]. Saturated fats such as palmitic acid (15%–25%) play roles in cellular processes and energy storage, while stearic acid (5%–10%) is less likely to raise cholesterol levels than other saturated fats. Monounsaturated fats like oleic acid (10%–20%) support cardiovascular health and reduce inflammation, and Linoleic acid (1%–2%) is an essential omega-6 FA that aids cell structure and immune function[33]. Additionally, docosapentaenoic acid (DPA), often present in trace amounts, serves as a precursor to EPA and DHA and may benefit heart health. The high omega-3 content, particularly EPA and DHA, makes fish byproducts, especially fish oil, an important source of FAs for animal feed and human supplements, contributing to overall health, reducing inflammation, supporting heart health, and promoting brain function[34].

The high concentration of omega-3 FAs (EPA and DHA) in fish byproducts offers significant health benefits, particularly for reducing inflammation, promoting heart health, and supporting cognitive function, making it a key component in human health supplements and animal feed[34]. These FAs enhance the quality of animal feed, especially in aquaculture, improving growth and health in fish and livestock. Additionally, utilizing fish waste for its FA content provides a sustainable source of essential nutrients, reducing waste and increasing the value of fish processing. The FA composition of fish byproduct waste is crucial in improving animal nutrition and human health and supporting sustainable food production systems.

Proximate composition of fish waste and byproducts

-

Fish byproducts generally have a high moisture content, typically ranging from 60% to 80%, which is crucial for processing as it affects drying and preservation methods[35]. These byproducts are rich in protein (15%–60%) regardless of the processing method and the fish species. Fish meal, derived from fish waste, is an excellent source of high-quality protein, essential for animal feed and human consumption[36]. Fish byproducts, especially fatty parts like the liver and viscera, are also rich in lipids, ranging from 5% to 30%, including beneficial omega-3 FAs such as EPA and DHA, which promote heart and brain health[37]. The ash content, representing the mineral content, typically ranges from 10% to 20%, providing essential minerals like calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, and potassium for animal feed and fertilizer production[38]. Fish waste generally contains less than 5% carbohydrates, primarily in the form of non-starch polysaccharides and other soluble sugars[39]. The fiber content in fish byproducts is low, around 1%–3%, mainly from connective tissues and scales, contributing to digestibility[17]. Additionally, fish byproducts are a good source of essential vitamins (A, D, B12), and minerals (iodine, selenium), which are important for animal and human nutrition[40]. The exact composition varies by fish species, processing method, and byproduct (e.g., fish meal, fish oil, fish silage), making it essential to understand the proximate composition for determining the nutritional value and potential uses of fish waste in industries such as animal feed, agriculture, and human consumption[41].

-

Processing, preserving, and applying fish waste and byproducts are critical to maximizing their value and reducing environmental impact. These processes are essential in transforming fish waste into valuable products for various industries, including animal feed, agriculture, cosmetics, and food production.

Processing

-

Fish waste and byproducts, which include bones, heads, skin, fins, and viscera (internal organs), can be processed and utilized in various ways across different industries. Here are the main types of processing, preservation, and applications of fish waste and byproducts:

Fish meal and fish oil extraction are key processes that produce valuable feed supplements and oils from fish waste[42]. Fish meal is a protein-rich powder made from fish and is commonly used as a feed supplement for livestock and fish. The production of fish meal involves several steps: first, the fish is cooked, typically by steaming, to coagulate the protein and release water and oil. After cooking, the coagulated fish is pressed to separate it into two phases: the solid phase, known as press cake, which contains protein, bones, and oil, and the liquid phase, called press liquor. The press cake is then dried to reduce its moisture content, which helps preserve it during storage. Finally, the dried fish is ground into a powder to improve its digestibility and nutrient absorption. This process makes fish meal an effective and nutritious feed supplement for livestock and aquaculture[43]. Fish oil is extracted from fish waste, particularly from the fatty parts such as the liver. This process typically involves mechanical or solvent extraction followed by refining. The extracted fish oil is a valuable source of omega-3 FAs. It is used in various applications, including as a supplement in animal feed and as a key ingredient in human nutritional supplements.

Fish silage is a liquid feed made from fish waste, whole fish, acid, and sometimes alkali. It is produced by mincing the fish waste or whole fish into small particles and then adding an organic or inorganic acid, such as sulfuric or formic acid, to lower the pH. This acidification process and the potential use of bacteria inhibit spoilage and allow the fish to liquefy. The fish and acid are mixed thoroughly to ensure that all the fish are in contact with the acid. Finally, the mixture is stored in an acid-resistant tank to preserve its quality until it is ready for use[44].

Chitosan production and fish collagen/gelatin production are both processes that utilize fish and crustacean byproducts for various applications. Chitosan is derived from the shells of crustaceans (such as shrimp) or fish by demineralizing and deacetylating the shells to produce chitosan. This biopolymer is widely used in industries ranging from agriculture to pharmaceuticals[45]. On the other hand, fish collagen and gelatin are extracted from fish skin and bones, typically through hydrolysis. This process breaks down the collagen into gelatin, used in the food, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical industries[46]. Both chitosan and collagen/gelatin production represent sustainable uses for fish waste and byproducts, offering a range of functional applications.

Determining the nutritional value of fish byproducts and their effect on poultry performance requires an understanding of their moisture content, drying temperatures, and changes in the chemical composition[47]. Feed quality, shelf life, and storage are all impacted by moisture content; low moisture maintains feed stability, whereas high moisture encourages microbial development and spoiling[48]. The moisture level of fish byproducts, which normally ranges from 60 to 80% in fresh material, plays an important role in storage stability and nutrient retention. Excess moisture can cause spoiling and microbial growth, whilst inadequate removal can reduce nutritional digestibility in poultry[49]. Moisture is reduced to about 10%–15% during drying to ensure preservation. Drying temperatures, typically ranging from 40 to 90 °C, are critical for preserving nutritional integrity[50]. Temperatures exceeding 60 °C can denature proteins, oxidize lipids, and degrade key vitamins including vitamin A and vitamin B, lowering nutritional value. Higher temperatures can also change the amino acid composition and reduce protein digestion, which affects poultry growth and performance[51]. Drying causes chemical changes such as the loss of water-soluble nutrients and the development of Maillard reaction products, both of which can impact feed palatability and quality. Thus, establishing the ideal drying temperature range (50–70 °C) and moisture content (10%–15%) is crucial for retaining the nutritious profile of fish byproducts[52]. This knowledge is critical for developing balanced chicken diets that enhance growth performance, feed efficiency, and overall poultry health. Further research into the impact of drying conditions on chemical composition will help to optimize the use of fish wastes as a sustainable and cost-effective feed additive.

Preservation

-

Fish waste can be preserved using several methods to prevent spoilage and maintain its nutritional value for further processing or application. One common method is freezing, which helps to maintain the quality of fish byproducts until they are ready for use. This is particularly beneficial for long-term storage and transportation, ensuring that fish waste remains usable for later processing[53]. Another method is drying, which removes moisture from fish waste, inhibiting the growth of bacteria and fungi, thereby extending its shelf life. Dried fish byproducts are lightweight, easy to store, and transport, and often used to produce fish meal, fish flour, or other fish-based ingredients[54].

Additionally, fermentation can be used, where fish waste is treated with microorganisms (such as bacteria) to preserve it, a process commonly used to produce fish silage. Fermentation not only preserves the fish but also enhances the digestibility and nutritional value of the resulting product, making it more suitable for animal feed[55]. Lastly, fish byproducts can be canned in vacuum-sealed containers, which helps preserve their shelf life and ensures long-term storage. Canning is often used for fish-based products like soups, broths, and other processed food items[56].

Application

-

Fish waste has various applications across industries. In animal feed, fish meal is a key component in aquaculture, livestock, and poultry, while fish protein hydrolysates and silage improve digestibility and nutrient absorption. Fish oil, rich in omega-3 FAs, promotes growth in aquaculture feed[57]. In agriculture, fish waste is processed into liquid or solid fertilizers, providing essential nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, and fish protein hydrolysates and silage act as biostimulants, boosting nutrient uptake and plant resilience[58]. Fish waste is converted into protein powder for protein bars and supplements for human consumption, and fish gelatin is used in food products, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics. Fish oil is also converted into supplements[59]. In cosmetics and pharmaceuticals, fish collagen improves skin elasticity and hydration, and chitosan from fish shells is used in weight loss supplements, wound healing, and as an antimicrobial agent[60]. Additionally, fish protein makes biodegradable plastics, and chitosan aids water treatment by removing impurities like heavy metals and oils[61].

-

Fish byproducts and waste, including fish meal, fish oil, and other fish-derived products, are commonly used in poultry feed due to their rich nutrient profile, which includes high-quality proteins, essential FAs, and minerals. Including fish byproducts in poultry diets can have positive and negative effects on poultry production, depending on the composition, quality, and quantity of the byproducts used[62]. However, the effects are listed under growth performance, egg quality, carcass characteristics, and blood parameters.

Poultry feed that contains fish waste and byproducts provides essential nutrients that promote health and productivity at every stage of development, from chick growth to egg production. During the chick stage, fishmeal offers highly digestible proteins and amino acids, such as methionine and lysine, which support tissue and bone development. Omega-3 FAs from fish oil increase growth rates, improve feed conversion, and boost immune function, laying the foundation for future growth[63]. As poultry enter the growing stage, fishmeal continues to support muscle development, while omega-3 FAs improve feed efficiency and cardiovascular health, enabling faster growth with less feed and strengthening immune responses.

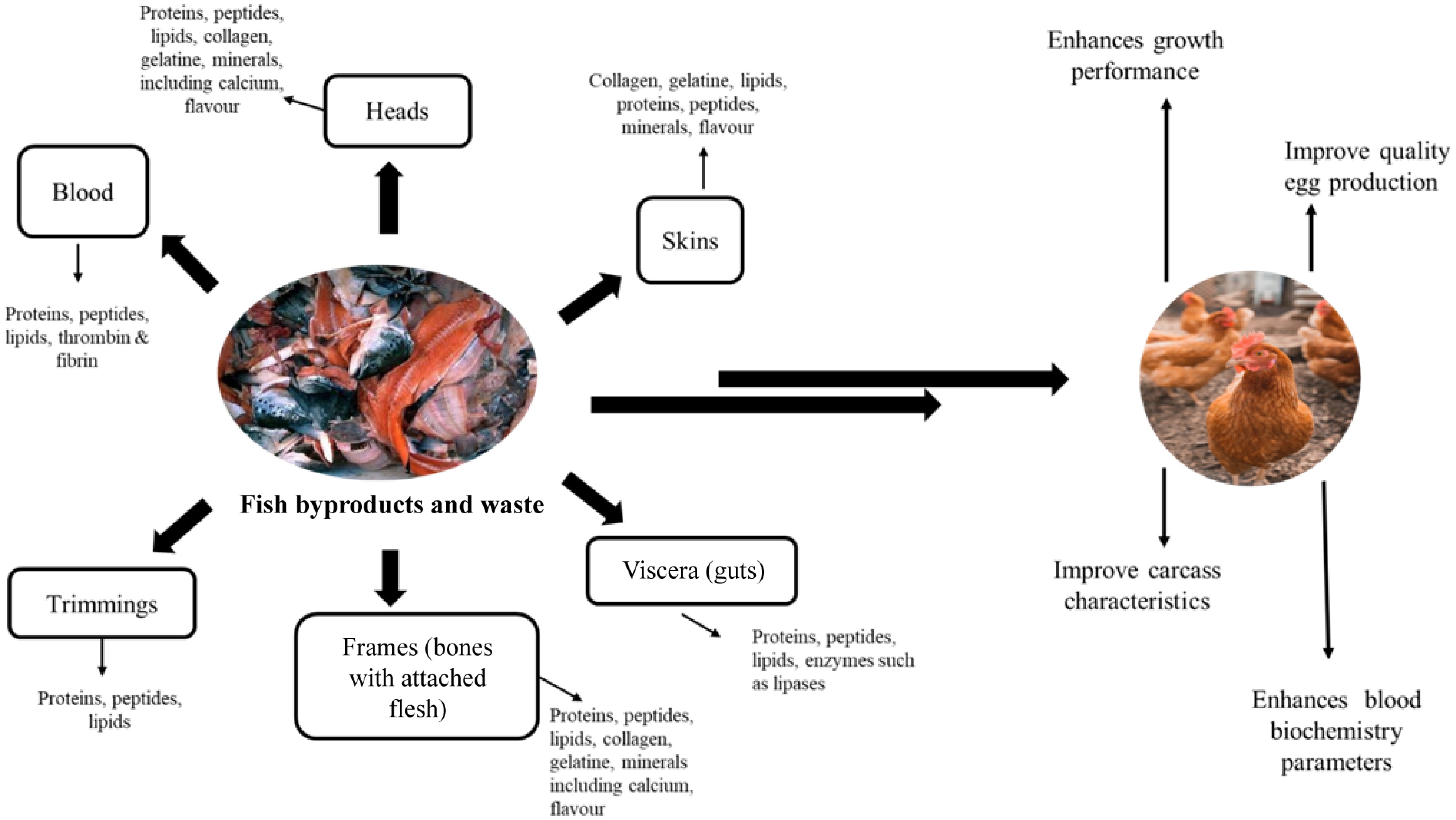

Fish byproducts play a vital role during the laying stage of egg production by supplying essential vitamins, proteins, and FAs that enhance egg quality. Omega-3s, such as EPA and DHA, not only improve fertility and ensure consistent egg production but also enrich the egg yolk, resulting in a high-quality product[63]. Additionally, the amino acids found in fishmeal support healthy reproductive systems and strong eggshells. By utilizing fish waste at every stage of development, poultry farmers can improve productivity, growth, and overall health while reaping financial and nutritional benefits[64]. The nutritional composition and significance of fish waste and byproducts in poultry feeds are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Effect of fish waste on poultry growth performance

-

When fish waste is added to poultry feed, it improves growth performance by providing a high protein and vital nutrient supply. Studies have demonstrated that moderate incorporation of fish waste byproducts, such as fish meal or fish oil, can improve poultry growth rates and feed efficiency. However, excessive amounts may have negative consequences, such as lower feed intake or unpleasant odors in meat and eggs. Proper formulation and balanced inclusion are critical to maximizing advantages while minimizing negative consequences. For example, Shabani et al.[65] found that broiler chickens exhibited improved growth when fed up to 120 g/kg of fish waste silage (FWS) for 42 d, suggesting that FWS is a valuable protein source for poultry. Similarly, another study showed that up to 10% acid-treated FWS could be incorporated into broiler diets without adversely affecting growth performance[66]. Additionally, research on fish waste fermented with molasses and specific probiotics revealed significant improvements in growth performance and feed conversion ratio when fed to day-old broiler chickens for 42 d[67]. Interestingly, even higher inclusion rates of FWS, such as 20% and 30%, did not significantly affect productive indices like growth and feed intake when included in broiler diets for 28 d[68]. These findings highlight FWS as a promising alternative for utilizing fish byproducts effectively.

Further research by Al-Marzooqi et al.[69] demonstrated that sardine FWS could replace up to 20% of soybean meal in broiler diets without negatively affecting growth, and this held true under both closed- and open-sided housing conditions. This study emphasizes the versatility of FWS in different environmental setups. Similarly, Smitha & Mercy[70] found that fermented FWS could replace up to 100% of unsalted dried fish in broiler diets without adverse effects on growth rate or feed conversion efficiency, underscoring its potential as an economical and viable protein source. In a related study, the use of rainbow trout viscera waste silage in broiler diets at 0%, 10%, 20%, and 30% inclusion rates led to significant improvements in feed consumption, live weight gain, and feed conversion ratio, with the best results observed at 10% and 20% inclusion rates[71]. This suggests that FWS provides excellent protein and nutritional value for broilers. Moreover, feeding Vanraja chickens with acid-ensiled fish waste for 45 d resulted in significant weight gain, lower feed conversion ratios, and reduced feed costs per kilogram of weight gain[72].

Additionally, supplementing broiler chicks of the Cobb-500 strain with 20%, 13.5%, and 7% fish waste significantly improved metabolizable energy intake and body weight gain. The feed conversion ratio also showed improvement compared to the control group during the finisher phase and throughout the entire experimental period[7]. These results highlight the potential of FWS to enhance the sustainability of poultry production, reducing dependence on conventional feed ingredients while maintaining optimal growth performance and feed efficiency in broilers.

Building on the potential of fish byproducts, Asrat et al.[7] evaluated dried tilapia byproducts in poultry feed, finding that it serves as an excellent source of protein and collagen. Their study showed that up to 50% inclusion significantly improved growth performance in broiler chickens. However, not all studies report positive outcomes with fish byproducts. For instance, Navidshad[73] observed that broiler chickens’ weight gain and growth parameters declined with the inclusion of fish oil after several weeks of feeding. In contrast, Avi et al.[74] found that broilers supplemented with 2% and 3% fish oil showed significantly higher live weight, feed intake, weight gain, and feed conversion ratio after 30 d, suggesting a positive impact on growth and feed efficiency under certain conditions.

Incorporating fish byproducts such as silage, offal, skin, and scales into poultry diets can significantly enhance growth performance. These byproducts improve weight gain, feed conversion, growth rates, and body composition by providing essential nutrients like proteins, omega-3 FAs, amino acids, and minerals. As a result, they offer a sustainable and cost-effective means to boost poultry productivity, making them a valuable addition to poultry nutrition strategies.

Effect of fish waste and byproducts on hen egg quality

-

Fish waste, including silage, offal, skin, and scales, enhances hen egg production by improving egg quality, yolk color, and shell strength. Rich in omega-3 FAs, amino acids, collagen, and minerals, it boosts egg nutrition[75]. Proper inclusion levels are crucial to maximize benefits without harming egg quality or hen health. Research shows that adding a small amount of fish waste oil to a hen's diet had little effect on egg quality. However, excessive amounts can negatively impact egg flavor, feed intake, and egg mass, potentially causing a fishy taste and reduced egg production[76,77]. When used in moderation, fish oil can enrich eggs with beneficial omega-3 FAs (EPA and DHA), enhancing their nutritional value. However, high levels of fish waste oil can cause a noticeable fishy flavor in the eggs and may reduce egg production by affecting feed intake and egg laying rates[76]. Studies suggest that including around 2% fish waste oil in a hen's diet is unlikely to significantly impact egg quality, provided the oil is highly quality and minimally oxidized[76].

Several authors have emphasized the importance of carefully balancing oil inclusion in laying hens' diets, as excessive amounts can negatively impact eggshell quality[78,79]. High oil levels are known to disrupt mineral metabolism, particularly calcium absorption and retention, due to the formation of insoluble soaps during digestion. This inhibits calcium’s effective utilization by the birds. Research has also highlighted that the quality of eggs, especially the yolk, is most affected by the inclusion of fat sources in poultry diets[80].

Supporting these findings, Grobas et al.[81] observed that feeding laying hens diets with various lipid sources led to an increase in egg weight. This change was attributed to fat deposition in the yolk, particularly from linoleic acid. Keshavarz & Nakajima[82] further suggested that this increase in egg weight could be due to changes in nutrient absorption, driven by the faster passage rate caused by the added fat source. The composition of FAs in the yolk also reflects the dietary FA profile, with variations in yolk FAs corresponding directly to changes in the levels of FAs in the diet[83].

However, not all studies agree on the effects of oils. For example, Cherian et al.[84] found that adding fish oil to hens' diets resulted in a decline in egg flavor, with the fish byproduct directly responsible for these sensory changes. In contrast, Brelaz et al.[76] reported that while incorporating fish waste oil into laying hens' diets did not affect egg quality, high inclusion levels negatively impacted feed intake, egg mass, and flavor. These mixed results underscore the need for careful management of fish waste inclusion to maximize the benefits while minimizing potential drawbacks. The effects of fish waste and byproducts on poultry production are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Effect of fish waste on hen egg quality.

Poultry species Maturity rate Types of fish byproduct/waste Inclusion levels Experimental findings Ref. Hisex White laying hens 29 weeks Fish waste oil 0.5%, 1.0%, 1.5%, 2.0%, 2.5%, 3.0%, and 3.5% for 105 d Incorporating fish waste oil into laying hens' diets did not impact egg quality. However, its high inclusion adversely affected feed intake, egg mass, and flavor. [76] Local hens 27–34 weeks Skipjack fish waste 0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% Including 10% Skipjack fish waste in hens, diets improved egg characteristics like color, aroma, texture, and flavor compared to the control. It did not significantly affect SAFA, MUFA, n-3, n-6, or the n-3 ratio. Increasing the inclusion to 20% also had no significant impact on these fatty acids. [85] White leghorn layers 5 months Locally processed fish waste meal 5%, 10%, 15% at 90 d Hen day egg production and mass were higher in diets with 5%, 10%, and 15% FWM than in the control. Yolk quality met standards, with no consistent trends in egg quality. Eggs from hens fed 10%, and 15% FWM had a moderate fishy flavor. FWM inclusion improved egg-laying performance and profitability but caused a moderate fishy flavor at levels above 5%. [86] Native chicken 27–34 weeks Skipjack fish waste 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% skipjack wastes for 8 weeks Skipjack waste had no significant effect on hen-day production (HDP), egg weight, yolk color, saturated fatty acids (SAFAs), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), omega-3 (En-3), omega-6 (En-6), or the omega-3 to omega-6 ratio compared to the control group. [87] Laying hen 12 months Sardine fish oil waste 0%, 5%, 10%, and 15% Adding 5% waste sardine fish oil significantly enhanced the chemical quality of laying hen eggs, including improved protein, fat, moisture, carbohydrate, ash, total energy content, and egg cholesterol levels. [88] Laying hen - Fish viscera silage (fresh, acid-preserved, ensiled, and ensiled concentrated viscera) 20% and 40% No significant differences in the quality of eggs from hens fed different diets were found. The inclusion of viscera waste did not significantly affect the sensory quality of the eggs but was better compared to the control. [89] Laying hens 22 weeks fish waste silage and fish fat 50 g/kg fish silage and fish fat (1.8, 8.8, 16.8 or 24.8 g/kg) Fish waste silage did not influence egg production, yolk color, or fatty acid composition. Diets with 16.8 or 24.8 g/kg fish fat reduced egg production but increased yolk color. The highest levels of C22:1 and PUFAs (C18:2 n-6, C20:5 n-3, C22:5 n-3, C22:6 n-3) were in diets with 24.8, 16.8, or 8.8 g/kg fish fat, while the lowest was in the 1.8 g/kg diet. C18:1 and C20:1 level was lowest in the 16.8 and 24.8 g/kg diets. Yolk cholesterol levels were unaffected. [90] Laying hens - Marine byproducts (scallop or squid viscera, shrimp heads, or whole mackerel waste) 5% 5% marine byproduct waste improves egg yolk composition by boosting omega-3 highly unsaturated fatty acids (HUFAs) compared to fishmeal. Additionally, these meals enhance astaxanthin levels and yolk pigmentation without altering egg sensory attributes. [91] ISA brown line laying hens (Gallus gallus domesticus) 16 weeks Silage waste from red tilapia viscera (Oreochromis sp.) 17.18% for 13 weeks Fish waste silage at a dry matter level of 17.18% did not yield statistically significant differences in egg quality parameters or their bromatological composition compared to the control. [92] Incorporating fish byproducts such as silage, offal, skin, and scales into poultry diets can improve egg quality, including yolk color, egg size, shell strength, and nutritional content. These benefits are primarily due to bioactive compounds like omega-3 FAs, amino acids, collagen, and minerals found in fish byproducts. By enhancing the physical characteristics and nutritional profile of eggs, these byproducts offer a sustainable and effective way to boost poultry egg production. To optimize the benefits of fish oil for egg production and quality, an inclusion level of 1% to 5% is ideal, as it supports improved egg production, increased omega-3 content, and better overall health for the hens. However, higher inclusion levels, especially above 10%, can lead to reduced egg production, diminished egg quality (such as a fishy flavor), and potential metabolic issues. Fish oils are generally rich in omega-3 FAs and low in omega-6, with linoleic acid content also being low (< 2%)[93]. The FAs are incorporated into the yolk for hens, making it more vulnerable to lipid degradation due to oxidation, hydrolysis, polymerization, or pyrolysis. These processes alter several characteristics of the egg, particularly flavor, aroma, texture, and color[94].

Effect of fish waste on poultry carcass characteristics

-

Carcass evaluation is a key method for determining the commercial value of livestock and is one of the most frequently conducted quality control tests in the meat industry[95]. The quality attributes of a carcass include cut size, tenderness, and the color of meat and fat. Marbling and fat cover, while composition attributes include lean meat, the proportions of fat, bone, and salable meat yield. Carcass evaluation helps describe livestock quality regarding suitability and commercial value for various end-uses, including processed meat products and retail cuts[96].

The effect of fish waste on carcass characteristics in poultry has been widely studied, yielding mixed results. While many studies report no significant differences, some note both reductions and improvements in carcass quality when compared to control groups. For example, replacing fish meal with FWS significantly reduced broiler carcass quality after 9 weeks[97]. This negative outcome was attributed to issues with amino acid balance and the presence of lipid oxidation products, which are limited in dried FWS. On the other hand, a study by Widjastuti et al.[98] found that 4% tuna fish silage resulted in optimal carcass percentage and meat protein conversion in broilers, highlighting the potential benefits of FWS under specific conditions.

In contrast, other studies have shown minimal changes in carcass yield despite incorporating FWS. For instance, no notable differences were observed in the sensory quality of broiler meat carcass yield or chemical composition when varying levels of FWS were used[68]. However, when broiler chicks were fed chemical silage made from rainbow trout viscera waste (at 0%, 10%, 20%, and 30% inclusion), significant differences in carcass yield were observed. The best results were achieved with 10% and 20% silage, suggesting that chemical waste silage provides valuable protein in broiler diets[71].

Further studies have explored the effects of fish viscera waste on carcass characteristics in both broilers and laying hens. For example, Krogdahl[89] assessed the impact of various fish viscera waste products, including fresh, acid-preserved, and ensiled viscera, on laying hens. They found that acid preservation and ensiling did not significantly affect the digestibility of most carcass amino acids. However, tryptophan content was reduced, and its digestibility was lower compared to the control group. Similarly, when up to 10% of the diet consisted of fish waste, no negative effects on dressed percentage or the relative weights of key carcass components, such as the heart, liver, and gizzard, were observed in day-old Vencobb broiler chicks[66].

Additionally, a study on varying levels of sardine fish silage fed to broilers in both closed- and open-sided housing systems found no significant differences in meat quality compared to the control group[69]. Another investigation found that including up to 3% pirarucu waste acid silage in laying hen diets improved nutrient digestibility and carcass characteristics, with the added benefit of acting as an energy source[99]. Furthermore, Cobb-500 strain day-old broiler chicks showed significant improvements in breast weight, drum-thigh weight, and eviscerated carcass yield when FWM was supplemented at 7%, 13.5%, and 20% levels, compared to the control group. The authors suggested that adding 20% FWM could enhance carcass yield and make broiler production more financially feasible[7].

Finally, incorporating fish waste oil into poultry feed can also significantly alter carcass characteristics, primarily by enriching the meat with omega-3 FAs. These FAs, which are beneficial for human health, can improve breast muscle yield and overall fat composition depending on the inclusion rate and the quality of the fish waste oil[7]. However, excessive inclusion of fish waste oil can negatively affect palatability, cause digestive issues, and lead to inconsistent responses across different poultry breeds. The quality of the fish waste oil – particularly its FA composition and the presence of contaminants – greatly influences its effects on the carcass. Some studies suggest that fish waste oil can slightly increase breast muscle mass and yield, thus enhancing the commercial value of the carcass. Additionally, it can shift the fat profile toward a higher proportion of unsaturated fats, which is more desirable[99].

Incorporating fish byproducts such as silage, offal, skin, and scales into poultry diets can positively influence carcass characteristics by improving meat yield, enhancing the FA profile, and contributing to better meat quality and texture. These effects are primarily attributed to fish byproducts' high protein, omega-3 FAs, and collagen content. These nutritional improvements can lead to healthier poultry products and potentially higher market value for producers.

Effect of fish waste and byproducts on poultry hematology parameters

-

Blood chemistry can reveal information about kidney function, blood glucose levels, and the balance between electrolytes and fluids[67]. Consequently, the evaluation of blood parameters in poultry-fed fish waste is important. Numerous studies have examined the effect of fish waste on blood parameters in poultry diets. For instance, a study on broiler chickens fed processed fish waste, including fish waste acid silage and surimi waste powder, over 3 weeks showed no significant differences in serum albumin, globulin, or total protein levels across the groups, with these markers positively correlating with age. Liver markers such as ALT, AST, SOD, Catalase, GSH, and LPO remained similar across all groups, although they increased with age. This suggests that the inclusion of fish waste in the diet did not cause liver damage. Typically, elevated AST, ALT, and LPO levels, alongside decreased SOD, Catalase, and GSH, would signal liver damage, but these were not observed in this study. Moreover, electrolyte levels of Na, K, Ca, Mg, and iron remained normal and consistent across all groups[100], indicating that the inclusion of fish waste did not disrupt electrolyte distribution in the body.

In contrast, another study investigated the effects of fish waste fermented with 15% molasses and 5% starter culture (containing Lactobacillus plantarum and Aspergillus oryzae) as a replacement for soybean meal in broiler diets. The experimental diets included 0%, 3%, 6%, 9%, and 12% fish waste from ages 11 to 42 d. The results showed that, after 23–42 d, serum levels of triglycerides, LDL, VLDL, and total cholesterol were significantly lower in the groups fed fermented fish waste compared to the control[65]. Additionally, significant increases in EPA and DHA concentrations were observed in the serum, liver, and meat of these groups, while total cholesterol levels in serum and liver were notably reduced[101]. These findings suggest that fermented fish waste may improve lipid profiles in broilers, enhancing both their health and nutritional quality.

Similarly, when Vanraja chickens were fed acid-ensiled fish waste for 45 d, cholesterol levels were significantly reduced, although other parameters such as triglycerides, glucose, hemoglobin (Hb), urea, creatinine, and total protein levels remained unaffected[72]. In line with this, a study by Darsana et al.[100] reported a significant reduction in triglycerides, glucose, total cholesterol, and uric acid in four-week-old Vencobb broilers, with no significant changes in hematological parameters like Hb, VPRC, TEC, and TLC. These results support the notion that fish waste can positively influence lipid metabolism in poultry without negatively affecting blood parameters.

In a similar vein, the inclusion of 10% acid-treated FWS in broiler diets led to a significant increase in the albumin-to-globulin ratio, as well as higher levels of triglycerides and cholesterol, compared to control groups and those fed 5% fish silage[66]. The authors concluded that up to 10% inclusion of acid-treated fish silage can be used in broiler diets without adversely affecting performance. This further suggests that FWS could be a viable protein source for poultry diets, with beneficial effects on metabolic and lipid profiles.

Another study found no significant changes in total protein, albumin, albumin-globulin ratio, total lipids, triglycerides, NEFA, VLDL, and total cholesterol levels in fish fed acid silage (fish waste) compared to those fed a fishmeal diet. Similar results were observed for serum enzyme and mineral (Ca, K, Fe, and Na) levels in day-old Vencobb broiler chickens over 7 weeks[100]. These findings suggest that, although FWS can have a positive impact on certain aspects of poultry health, its effects on some key metabolic and lipid markers may be neutral, indicating that the inclusion level and type of fish waste may influence the overall outcomes. Therefore, incorporating fish waste into broiler diets is recommended to reduce feed costs, improve profitability, and minimize environmental pollution without affecting growth or meat quality. Feeding fermentatively recovered fish waste lipids reduced total cholesterol concentrations in the serum, meat, and liver of broilers compared to the control groups. However, no significant difference in triglyceride concentrations was observed between the treatments. Notably, as the fish waste lipid concentration increased, higher levels of EPA and DHA were found in the serum of the FFO-fed groups compared to both control groups[101].

In a different study, the effects of FWS were evaluated in Isa-Brown laying hens. After 16 weeks, the red blood cell count (erythrocytes, hemoglobin, and hematocrit) and white blood cell count (leukocytes and lymphocytes) were higher in the control diet than in the silage diet. This suggests that hens fed the waste silage diet experienced improved physiological function, including better oxygen and nutrient transport, which could enhance metabolism, immune response, and overall productivity in the hens[92]. This study showed that replacing dietary protein with viscera waste silage in laying hens did not significantly alter blood parameters. Nevertheless, the albumin-to-globulin ratio and triglyceride levels increased significantly in broilers fed 10% acid-treated FWS, and serum cholesterol levels rose with increasing silage from 5% to 10% compared to the control diet. It was concluded that up to 10% acid-treated fish silage can be incorporated into broiler diets without adversely affecting performance[66].

Impact of fish byproducts on gut microbiota and digestive health in poultry

-

The gut microbiota plays a crucial role in poultry's overall health and productivity, influencing various factors such as digestion, nutrient absorption, immune function, and disease resistance[102]. In recent years, there has been growing interest in how fish byproducts like fishmeal, fish oil, and fish silage can positively influence poultry gut health by promoting a balanced gut microbiome. These fish-derived ingredients contain bioactive compounds, including omega-3 FAs, protein hydrolysates, amino acids, and antioxidants, which can modulate the microbial environment within the gastrointestinal tract.

One of the key ways fish byproducts impact gut health is through their potential to act as prebiotics. Prebiotics are compounds that stimulate the growth of beneficial microorganisms in the gut. Fish byproducts, especially fish silage and fish hydrolysates, have been shown to encourage the growth of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and bifidobacteria, which are known to promote gut health[103]. For instance, birds fed FWS60 and FWS120 had lower coliform and E. coli counts and higher Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus levels in the ceca than those fed the control diet. Additionally, FWS60 and FWS120 diets increased cecal butyrate and lactic acid levels. Birds on the FWS120 diet showed higher intestinal amylase and protease activity than those on the control diet. However, no significant differences in pancreatic digestive enzyme activity were observed between the treatment groups[104]. These beneficial microbes help maintain a healthy balance by outcompeting harmful pathogens, thereby reducing the risk of gastrointestinal diseases. Additionally, fish-derived proteins and peptides can help enhance the digestibility of feed, leading to more efficient nutrient absorption and improved growth performance in poultry.

Furthermore, omega-3 FAs (particularly EPA and DHA) found in fish oil can influence gut health by reducing inflammation and supporting the integrity of the gut lining[105]. These FAs have anti-inflammatory properties, which help maintain a healthy balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory signals in the gut. Inflammation is a major factor in digestive issues such as leaky gut syndrome and intestinal diseases. By improving gut barrier function, fish byproducts may reduce the incidence of gastrointestinal disorders, enhance feed efficiency, and promote better overall health in poultry. Additionally, fish byproducts are rich in antioxidants like vitamin E and selenium, which can help combat oxidative stress in the gut[106]. Oxidative stress is detrimental to gut health, damaging gut cells and disrupting normal microbial activity. By counteracting this oxidative damage, fish-derived antioxidants contribute to gut mucosal protection, allowing for better digestion and nutrient absorption, directly impacting growth and overall productivity.

Incorporating fish byproducts into poultry diets can significantly enhance digestive health, leading to a more balanced and resilient gut microbiota. This not only supports optimal nutrient absorption and growth performance, but it also plays a vital role in strengthening the poultry's immune system, reducing disease susceptibility, and improving the overall welfare of the birds. As the poultry industry moves toward more sustainable and natural feeding strategies, utilizing fish byproducts for their potential gut health benefits represents a promising and innovative approach to enhancing poultry production.

-

The sustainability of the entire supply chain can be enhanced by adding fish waste to chicken feed. Farms can reduce their ecological impact by sourcing local fish byproducts, lowering shipping costs and carbon emissions. In addition, utilizing these byproducts can improve waste management practices in the fish processing sector, where disposing of fish waste can be expensive. As a result, adding fish waste to chicken feed promotes the efficient use of resources across multiple industries. It supports more sustainable agricultural methods, benefiting the fishing and poultry industries. This knowledge can then be broadened into different categories, potentially expanding its applications and benefits.

Nanotechnology in the utilization of fish byproducts on poultry feed

-

Nanotechnology presents a novel approach to enhancing chicken feed's nutritional content and sustainability derived from fish waste[107]. Although fish byproducts, such as fish oil, fish hydrolysates, and fishmeal, are high in protein, omega-3 FAs, and essential amino acids, they often face issues with stability, digestibility, and bioavailability. In this context, by altering these elements' molecular or nanoscale physical characteristics, nanotechnology can address these problems and improve the nutritional value of poultry feed.

One notable application of nanotechnology is enhancing the bioavailability of nutrients, especially omega-3 FAs in fish oil. Poultry health benefits greatly from omega-3 FAs, which promote development, immune system performance, and meat and egg quality. However, omega-3 FAs are susceptible to oxidation, which, in turn, can reduce their nutritional content[108]. To counter this, omega-3 FAs are protected from oxidative degradation by being encapsulated in nanoparticles, ensuring stability and effective absorption in the poultry's digestive tract. As a result, this controlled release enhances the overall utilization of these essential fats.

Furthermore, fishmeal's enzymatic hydrolysis can be improved through nanotechnology, which enhances poultry's ability to digest the protein. The complex proteins in fishmeal can be broken down into smaller peptides or amino acids using nanosized enzymes, increasing feed conversion rates and reducing the need for artificial protein sources[109]. In addition, by improving flowability, reducing clumping, and stabilizing the feed during storage, nanomaterials such as nanoclays or nanopolymers can enhance the physical properties of fishmeal[110]. Nanotechnology can also boost the antibacterial and antioxidant qualities of fish byproducts, providing a safe and natural alternative to antibiotics and improving the overall quality of chicken feed. Ultimately, these advancements have significant potential to improve poultry feed's efficiency, sustainability, and nutritional value, though further research is needed.

The role of fish byproduct in enhancing omega-3 enrichment in poultry product

-

Fish byproducts, including fishmeal, fish oil, and fish skins, are high in omega-3 FAs, such as DHA and EPA, which offer several health benefits, including enhanced immune response, reduced inflammation, and improved cardiovascular health[111]. As a result, as consumer demand for healthy meat and eggs continues to rise, these byproducts provide an ideal way to add omega-3s to poultry products. By incorporating fishmeal or fish oil into poultry feed, we can increase the omega-3 content of eggs and meat, thus making them a healthier alternative to conventional poultry products. Moreover, fish skins and other underutilized fish byproducts also contribute additional omega-3 FAs and other beneficial nutrients, such as collagen and gelatin, which improve the overall quality of poultry products while reducing waste and promoting sustainability[112].

The processing method used to incorporate fish byproducts is crucial in maximizing their nutritional benefits. For instance, nanoencapsulation can protect omega-3s from oxidation, improving their stability and bioavailability in the poultry’s digestive system. Compared to plant-based omega-3 sources like flaxseed or algae, fish byproducts offer a more sustainable and natural source of long-chain omega-3s (EPA and DHA)[112]. Given that consumer demand for sustainable and nutritious products grows, omega-3-enriched poultry products can be sold at a premium, providing economic benefits for poultry producers and improving public health outcomes.

Optimizing the use of fish byproducts in poultry feed for organic and free-range poultry farming

-

Optimizing fish byproducts in organic and free-range poultry production has potential benefits and challenges, especially when upholding organic certification standards and ensuring the birds' health. Careful feed ingredient selection is necessary for organic systems, which prioritize sustainability, animal welfare, and natural feeding. Rich in protein and omega-3 FAs, fish byproducts such as fishmeal and fish oil can improve the nutritional content of chicken products[113]. Still, they must come from responsibly harvested and certified organic sources. Farmers can uphold the integrity of organic and free-range farming principles, encourage sustainable practices, and reduce reliance on traditional feed sources like soy by utilizing these byproducts.

Fish byproducts can be added to the diet of free-range chickens, which naturally forage for insects and plants, to maximize the omega-3 content of their meat and eggs. These FAs help create a more nutrient-dense end product by boosting the immune system, lowering inflammation, and enhancing cognitive function[114]. However, since natural fodder may not provide enough omega-3s, adding fish waste is a useful supplement. This way, free-range farming principles can be upheld while ensuring feed quality and aligning with ethical standards by purchasing fish byproducts from environmentally conscious aquaculture operations or sustainable fisheries.

Advanced processing methods like fermentation, enzymatic hydrolysis, and nanoencapsulation can enhance digestibility and maintain nutrient integrity to optimize the benefits of fish waste in poultry feed. While enzymatic hydrolysis facilitates the digestion of larger protein molecules, fermentation can improve nutritional absorption by converting fishmeal into more easily digested peptides[115]. In addition, by preventing deterioration, nanoencapsulation can prolong the shelf life of omega-3s without artificial preservatives. Moreover, by decreasing waste and encouraging circular farming methods, which turn fish waste into valuable resources for poultry feed, these techniques increase feed efficiency and promote sustainability.

Circular economy approaches: integrating fish byproducts into poultry farming systems

-

In agriculture, the idea of a circular economy is becoming more popular as it provides long-term ways to reduce waste and improve resource efficiency. A major factor in supporting this paradigm in chicken farming is the incorporation of fish byproducts into the production cycle[116]. The fish processing industry frequently discards fish byproducts, such as heads, bones, skins, and offal, high in proteins, amino acids, and omega-3 FAs. Farmers can promote sustainability and lessen their environmental impact by utilizing these byproducts to make poultry feed instead of relying on materials that require a lot of resources, such as corn and soy. This method supports the systems for producing fish and poultry, reduces waste, and creates resources with added value.

Locally sourcing fish byproducts for chicken feed can improve the circular economy model by reducing emissions and shipping expenses. Using locally available fish byproducts, chicken farms can lessen their reliance on long-distance imports, such as soya meal, in coastal areas where fish processing is prevalent[117]. As a result, the carbon impact of feed production is reduced, and there is less reliance on resource-intensive crops like soy, which further harm the environment. Moreover, poultry farming can upcycle captured fish byproducts to build a more sustainable agricultural system by converting waste into higher-value products and encouraging efficiency and sustainability across sectors.

A mutually beneficial interaction between the fisheries and poultry industries is promoted by incorporating fish byproducts into chicken rearing. Fish processing facilities provide poultry farms with affordable, nutrient-rich feed, which, in turn, creates a consistent market for these wastes, reducing waste while optimizing resource value. Furthermore, adding omega-3 FAs to poultry products like eggs and meat can improve their nutritional profile by incorporating fishmeal and fish oil into poultry feed[118]. As a result, by appealing to health-conscious consumers, farmers can tap into specialized markets and potentially increase the price of omega-3-enriched products. In addition, the digestibility and bioavailability of fish byproducts may also be enhanced by developments in biotechnology and nanotechnology, which would maximize their use in chicken feed and promote a more productive, sustainable agricultural strategy.

-

Potential advantages of using fish waste and byproducts in poultry production include cost-effectiveness and sustainability; however, several restrictions must be considered to ensure their safe and efficient integration into chicken feed. Concerns over nutrient fluctuations, potential contamination, processing difficulties, and consumer acceptability are some of these restrictions.

Microbial contamination

-

The abundance of bacterial pathogens in fish waste and byproducts used in chicken feed is a major issue because of the nutrient-rich environment that breeds harmful bacteria such as Salmonella, Escherichia coli, Vibrio spp., and Listeria monocytogenes[119]. These bacteria can grow and contaminate the final chicken feed if processing or storage conditions are not optimal. Among the factors influencing the growth and survival of bacteria in fish waste are temperature, organic matter, and moisture content. One effective method of lowering the moisture content is drying[120]. Drying methods like spray and drum drying lower water activity, which inhibits the metabolism of microorganisms and prevents their growth. Another technique is pasteurization, which preserves the nutritional value of the feed while killing the majority of harmful bacteria by heating it to 70–85 °C for 15–30 min. Furthermore, antimicrobial substances such as organic acids (like lactic acid) and essential oils (like thyme and oregano) can break down bacterial cell walls and stop their growth[47]. Additionally, probiotics like Bifidobacterium or Lactobacillus can be employed to compete with pathogens for nutrients. Frequent microbiological monitoring throughout production is essential for early contamination detection and feed safety through the regulation of environmental factors like moisture, pH, and temperature.

Nutrient variability

-

The inherent heterogeneity in the nutritional composition of fish waste and byproducts is one of the main drawbacks of employing them[17]. The protein, fat, and mineral content of fish byproducts, including fishmeal, fish oil, and other offal, can vary significantly based on the species of fish, the processing techniques used, and the environmental circumstances in which the fish were produced. It may be challenging to create consistent and balanced poultry feed because of this unpredictability. Variations in nutrients can cause nutritional imbalances in the diet of poultry, which could have an impact on the birds' general productivity, growth, and health[121]. Extensive testing and exact control during the processing phase are frequently necessary to guarantee that the nutrient content of fish byproducts stays within the required specifications, which might raise costs and complexity.

Risk of contaminant accumulation

-

Fish feces, particularly those from wild-caught fish, may contain trace levels of environmental pollutants such as heavy metals (like cadmium and mercury), persistent organic pollutants (POPs), and other toxins that accumulate over time in the fish's body[122]. During processing, fish oil and fishmeal can absorb these pollutants. Although the risks can be reduced by strict regulations and quality control procedures, the presence of these toxins remains a serious concern. The accumulation of pollutants in poultry feed can lead to the bioaccumulation of toxic compounds in the birds' tissues, which may then affect human consumers[123]. Fish byproducts must be closely monitored for contaminant levels to ensure they remain within acceptable limits for both human and poultry consumption.

Processing complexity

-

Fish waste and byproducts are processed into chicken feed by a series of procedures, including drying, grinding, and, in certain cases, heat treatment or fermentation[124]. Each of these procedures necessitates careful monitoring to prevent nutrient deterioration and the elimination of dangerous microbes. The complexity and cost of processing may limit the widespread use of fish waste and byproducts, particularly in small-scale businesses. Furthermore, certain feed makers may be unable to process these materials due to the need for specific equipment and knowledge, making the method less accessible or economically viable for particular producers.

Ethical and consumer acceptability issues

-

Some consumer organizations may have ethical questions about the use of animal-based byproducts, particularly those from fish, in chicken feed. Incorporation of animal-derived byproducts in chicken feed, particularly those sourced from fish, may elicit ethical apprehensions among some customer demographics[125]. Furthermore, some customers might be worried about food safety, allergies, or the environmental effects of employing fish waste, particularly in areas where fish populations are under stress. Therefore, even if the feed is thought to be safe and nutrient-dense, public opinion may restrict the demand for chicken items produced on it.

Sustainability and resource competition

-

Although employing fish waste can be regarded as a sustainable technique in terms of waste reduction, there is continuous discussion on whether fish byproducts should be utilized for animal feed or directed for human consumption. The growing demand for animal feed could put alternative uses – such as feeding humans or supporting the aquaculture industry – in competition with fishmeal, a good supply of protein and essential FAs. The sustainability benefits of employing byproducts could be undermined if there is an over-reliance on fish-based products for poultry feed, as this could increase demand for wild-caught fish and worsen pressures on fish populations[126].

Innovation and future research

-

The use of fish waste and byproducts in poultry farming offers a promising avenue for innovation, particularly in sustainability, nutrition, and waste management. One of the most compelling innovations lies in developing efficient and cost-effective methods to process fish waste into high-quality poultry feed. Traditionally, fish byproducts, including offal, bones, and scales, are discarded or used in limited applications like pet food or aquaculture feed. However, through advanced processing techniques such as hydrolysis, enzymatic treatments, and fermentation, it is possible to enhance the nutritional value of these byproducts, making them more digestible and beneficial for poultry diets[127]. Future research could focus on refining these processing technologies to increase the bioavailability of essential nutrients in fish waste, optimizing their incorporation into poultry feed formulations.

In addition to processing innovations, future research could explore novel ways to diversify the types of fish waste used in poultry diets. While fishmeal is the most commonly used byproduct in poultry feed, several other possible sources of fish waste could offer different nutritional profiles. For example, fish oils, scales, and even fish viscera can produce nutritionally rich feed ingredients that may provide additional health benefits, such as improved immune function and enhanced egg quality[128]. Researchers could develop tailored feed solutions that cater to specific poultry breeds or production systems by investigating the nutritional compositions of different fish species and their byproducts. This further enhances poultry health and productivity.

Sustainability will be a critical focus for future research on fish waste in poultry farming. One promising area of innovation is the potential for reducing the environmental impact of feed production by utilizing fish byproducts as a sustainable, local alternative to conventional agricultural feed ingredients like soy or corn. Culturing these crops requires extensive land, water, and energy resources, contributing to deforestation, habitat loss, and greenhouse gas emissions[129]. In contrast, fish waste is often available in coastal regions where poultry farming may not be as land-intensive, thus offering an opportunity to reduce the carbon footprint of poultry feed production. Future studies could investigate life cycle assessments (LCAs) to compare the environmental impact of fish waste-derived feed versus traditional feed ingredients, ultimately demonstrating the sustainability benefits of this approach.

Another area ripe for innovation is the improvement of the economic viability of fish waste in poultry farming. One of the key challenges of using fish byproducts in feed is the cost of processing and transportation, which can be a barrier to widespread adoption, particularly in regions without established fishmeal industries. However, new research into cost-effective processing techniques, such as on-site production of fishmeal using local fish waste, could help reduce costs and improve the scalability of this solution[130]. Furthermore, integrating fish waste into poultry farming could create a symbiotic relationship between local fisheries and poultry farms, enabling a more localized and resilient agricultural supply chain. Future research could focus on developing economic models demonstrating the potential for cost savings and economic growth in areas where both industries coexist.

From a technological standpoint, future studies could explore the most effective ways to incorporate fish byproducts into chicken feed systems through automation and digital tools. For instance, blockchain technology and smart sensors could be employed to monitor fish waste's sourcing, processing, and quality control, ensuring that feed components are reliable and of the highest quality. Additionally, large datasets from chicken farms could be analyzed using machine learning algorithms to determine the optimal inclusion rates of fish-based nutrients for different stages of poultry production (growth, laying, etc.). These technologies could help reduce waste and inefficiencies in feed production while streamlining the feed formulation process and ensuring that chicken diets are balanced and tailored to promote maximum health and productivity[73].

Lastly, there is a significant opportunity to investigate the broader impacts of using fish waste in poultry farming on food security and global supply chains. As the demand for protein-rich food continues to rise, particularly in developing countries, using locally sourced fish byproducts in poultry feed could play a crucial role in enhancing the availability of affordable animal-based protein[131]. Research could focus on the scalability of this approach, exploring how fish waste can be effectively incorporated into poultry farming systems in different geographical regions, from small-scale operations to large commercial farms. Additionally, by promoting the use of fish waste in animal feed, there may be potential for reducing food waste in both the fisheries and poultry industries, contributing to more sustainable and resilient global food systems.

-

Fish waste poses significant environmental and economic challenges, necessitating improved management practices to address these issues. Consequently, developing sustainable fish waste management strategies has become crucial, aligning with directives like the Waste Framework Directive, which emphasizes minimizing waste generation and utilizing generated waste as a resource through reuse, recycling, and recovery efforts. Considering various advantages and drawbacks, the study suggests that fish waste and byproducts can be incorporated into broiler poultry diets at specific levels without compromising performance, egg quality, hematological parameters, or carcass characteristics. This indicates that supplementing poultry rations with fish waste is sufficient to meet the protein requirements of various poultry species while maintaining body weight, weight gain, feed efficiency, and carcass yield comparable to control diets in most commercial poultry operations. The balanced fat, mineral, and protein content of fish waste makes it suitable for inclusion in poultry, fish, and livestock feed formulations. Therefore, integrating fish waste into poultry rations increases revenue without compromising feed efficiency, nutritional status, serum biochemistry, growth, or overall bird performance. It also provides an opportunity for the fish industry to enhance income while mitigating pollution associated with fish waste.

-

Not applicable.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Abasubong KP, Uwem GU, Desouky HE; writing − original draft: Amin AB, Abasubong KP; writing − editing & review: Abasubong KP. All authors reviewed the results and approved thefinal version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Abasubong KP, Amin AB, Uwem GU, Desouky HE. 2025. A review of fish waste and byproducts in poultry production: effects on growth, egg quality, carcass traits, and broader knowledge beyond physiological response. Animal Advances 2: e021 doi: 10.48130/animadv-0025-0027

A review of fish waste and byproducts in poultry production: effects on growth, egg quality, carcass traits, and broader knowledge beyond physiological response

- Received: 04 February 2025

- Revised: 25 March 2025

- Accepted: 06 June 2025

- Published online: 05 August 2025

Abstract: Fishery waste has become a significant global concern in recent years, driven by biological, technical, operational, and socioeconomic factors. As global fish production has increased, so has the amount of material available for processing, resulting in higher waste quantities. These materials, including bones, skin, fins, and organs, contain valuable substances such as proteins, lipids, enzymes, pigments, and vitamins. Therefore, converting these wastes into marketable products is crucial for adding value and mitigating environmental pollution. By utilizing non-traditional, locally available feed components, poultry farms can develop cost-effective feed formulations that help reduce feed costs. Enhancing poultry's efficiency in converting feed into body growth is essential for the sustainable intensification of poultry production. Numerous studies have shown that supplementing poultry diets with fish waste or byproducts can meet protein requirements without significantly affecting growth performance, feed efficiency, egg quality, serum composition, or carcass yield compared to control diets in most commercial poultry species. Beyond nutritional benefits, utilizing fish waste supports sustainable agricultural practices by reducing waste, lowering the environmental impact of feed production, and promoting circular economy principles. This review highlights the benefits of incorporating fish byproducts into poultry diets and underscores the need for additional research to optimize their use in commercial poultry farming.

-

Key words:

- Fish byproducts /

- Fish waste /

- Recycling /

- Poultry /

- Omega-3 fatty acid /

- Egg production /

- Recycling