-

Joint disorders are a significant concern in companion animal health, particularly in aging individuals and large-breed dogs, where both developmental and degenerative joint diseases (DJDs) can severely compromise mobility and overall quality of life[1]. Among these disorders, osteoarthritis (OA) is the most prevalent, characterized by progressive cartilage degradation, subchondral bone remodeling, synovial inflammation, and oxidative stress-induced damage[2]. At the molecular level, OA is driven by an imbalance between anabolic and catabolic processes within the extracellular matrix (ECM), primarily regulated by pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), and (interleukin-6) IL-6 through activation of the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signaling pathway[3]. Additionally, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), especially MMP-3 and MMP-13, exacerbate collagen degradation and impair joint homeostasis[4]. Given the increasing prevalence of OA in pets and its multifactorial etiology, a comprehensive understanding of risk factors and management strategies is crucial.

Proper nutritional interventions play a vital role in mitigating these degenerative processes by modulating inflammatory pathways, oxidative stress responses, and chondrocyte apoptosis[5]. Omega-3 fatty acids, including eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), exert anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting the arachidonic acid cascade, reducing prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) synthesis, and suppressing the NF-κB pathway, which in turn limits cytokine-induced cartilage degradation[6]. Glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate, also, have chondroprotective potential and may improve clinical scores with slower onset than non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in canine OA trials[7]. Moreover, polyphenolic compoundssuch as resveratrol, curcumin, and epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) have shown nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 (NRF2)-linked antioxidative and anti-catabolic effects in chondrocytes and animal OA models, while clinical evidence in companion animals remains preliminary[8,9].

Beyond DJDs, nutritional imbalances during critical developmental stages can predispose companion animals to lifelong orthopedic disorders. Excess calcium (Ca) intake during rapid growth impairs endochondral ossification and increases risk for developmental orthopedic disorders in large-breed puppies, as shown in controlled Great Dane feeding studies; appropriate Ca–phosphorus (P) balance and energy control are therefore critical[10]. Dysregulation of the Ihh–PTHrP axis is central to endochondral ossification; nutritional imbalances that disturb mineral homeostasis may secondarily perturb these pathways[11]. Vitamin D deficiency primarily compromises intestinal Ca and P absorption, causing defective mineralization (rickets/osteomalacia) and skeletal deformities in growing animals; its effects are best framed in mineral homeostasis rather than reduced receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand (RANKL) signaling[12,13].

This review aims to explore the nutritional strategies for managing joint health, focusing on evidence-based interventions, the role of specific nutrients, and emerging therapies that may enhance joint health outcomes in companion animals. By elucidating these connections, we hope to create awareness and encourage proactive management approaches that ultimately lead to healthier and more active lives for these beloved pets.

-

As one of the most prevalent joint disorders in companion animals, OA warrants close attention due to its complex etiology and significant impact on mobility and quality of life. This section explores the fundamental aspects of joint health in companion animals, with an emphasis on OA, joint anatomy, and the influence of nutrition on inflammatory processes.

OA is a type of DJD characterized by the progressive breakdown of cartilage, which cushions the ends of bones in joints[14]. This deterioration leads to bones rubbing against each other, causing pain, stiffness, and reduced mobility. Current estimates indicate that OA affects approximately 80% of dogs over the age of eight, making it one of the most prevalent chronic conditions in companion animals[15]. Furthermore, recent studies have identified radiographic evidence of OA—including osteophytes, enthesophytes, subchondral sclerosis, bone erosions, and cysts—in a notable proportion of younger dogs (aged 8 months to 4 years), indicating that OA may be underdiagnosed in early life stages[16]. This highlights the pressing need for effective management strategies to address joint health issues early in life.

Understanding joint anatomy is essential to comprehending how nutritional choices affect joint health. The primary components of a synovial joint include articular cartilage, synovial fluid, ligaments, and the surrounding joint capsule[17]. Articular cartilage is composed of chondrocytes and an ECM rich in collagen and proteoglycans, which provide structural integrity and resilience to the joint[18]. The synovial fluid lubricates the joint, minimizes friction, and serves as a shock absorber. Nutrition plays a critical role in maintaining the health of these structures, with key nutrients such as omega-3 fatty acids, glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and antioxidants being vital for cartilage maintenance and the reduction of inflammation[19–22].

The relationship between nutrition and inflammation is particularly relevant in the context of joint problems such as OA[23]. Chronic inflammation is a hallmark of OA and contributes significantly to the degeneration of both cartilage and surrounding tissues[24]. Certain dietary components, such as omega-3 fatty acids, possess anti-inflammatory properties that can modulate the inflammatory response and mitigate the symptoms associated with joint disease[25]. Conversely, diets high in processed foods, sugar, and unhealthy fats can exacerbate inflammatory processes, leading to the progression of joint conditions[26]. This underscores the necessity of formulating diets rich in anti-inflammatory nutrients to support joint health and improve the quality of life in affected pets.

In summary, understanding the importance of joint health in companion animals, along with the intricate relationships between OA, joint anatomy, and nutrition, is essential for effective management. A multifaceted approach that includes a tailored diet rich in key nutrients can significantly contribute to the maintenance of joint health and overall quality of life for pets suffering from joint-related issues.

-

Chondrocytes are pivotal in maintaining cartilage homeostasis by balancing the synthesis and degradation of the ECM. This regulation is primarily mediated through pathways such as SRY-box transcription factor 9 (SOX9), a transcription factor essential for chondrogenesis, which upregulates the expression of collagen type II and aggrecan, key components of cartilage that promote its integrity and functional capacity[27,28]. Conversely, catabolic factors such as MMPs and a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs (ADAMTS) drive cartilage degradation. Notably, MMP-13 specifically targets collagen type II for degradation, while ADAMTS-5 primarily degrades aggrecan, thereby facilitating the progression of joint degeneration[29,30]. In addition, mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling promotes chondrocyte anabolic activity, including proliferation and matrix synthesis, while concurrently suppressing autophagy. Sustained hyperactivation of mTORC1 disrupts cellular homeostasis and contributes to OA progression. In contrast, inhibition of mTORC1 restores autophagy and alleviates cartilage degeneration, underscoring its potential as a therapeutic target for OA[31].

Synovial inflammation and joint degeneration

-

The synovial membrane is integral to immune regulation within joints. In pathological conditions such as OA and rheumatoid arthritis (RA), activated fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS) and macrophage-like synoviocytes (MLS) release pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6. These cytokines are instrumental in promoting chronic inflammation and synovial hyperplasia, which exacerbate joint damage[32,33]. Furthermore, dysregulated signaling pathways, notably NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), amplify inflammatory responses by increasing the production of additional MMPs and other inflammatory mediators, contributing to the degradation of articular cartilage[34,35].

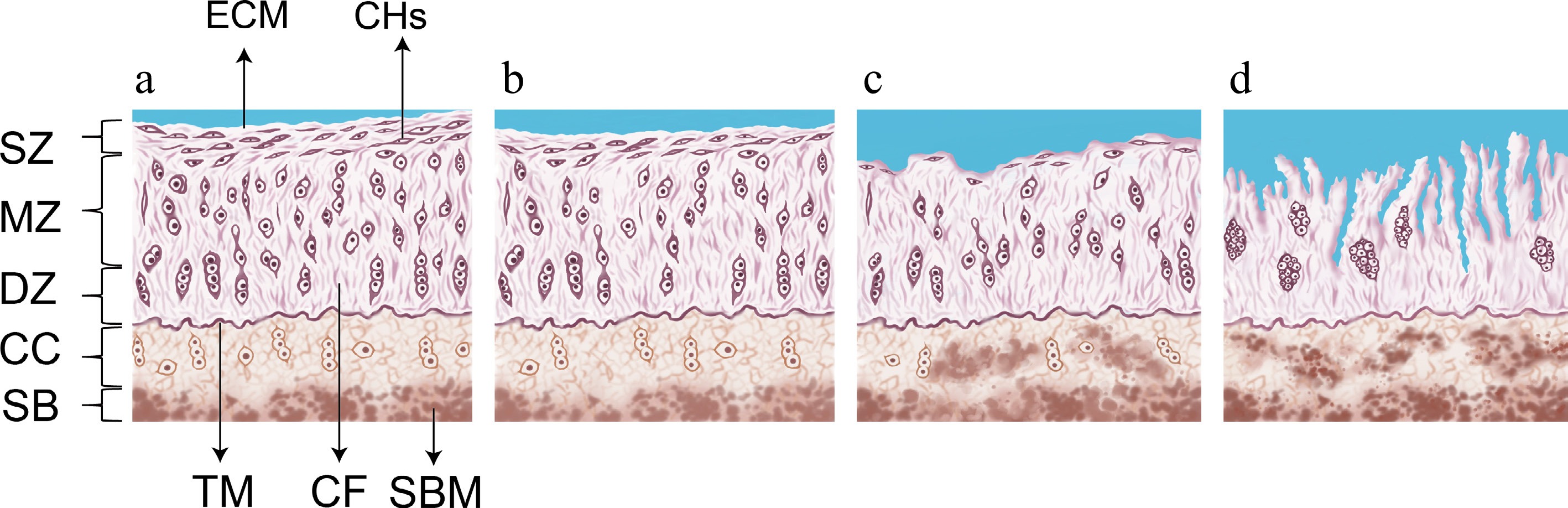

The anatomical structure of synovial joints is largely conserved across companion animal species, including dogs, cats, and horses. A four-stage histological model has been established to characterize the progressive degeneration of articular cartilage (Fig. 1). The process typically begins with the initial loss of proteoglycans and collagen network integrity in the superficial zone (SZ), which constitutes approximately 10%–20% of the cartilage thickness. This layer contains flattened chondrocytes and parallel collagen fibers (CF), providing shear resistance and protecting the underlying structure. As degeneration progresses, the middle zone (MZ)—accounting for 40%–60% of the cartilage volume—exhibits disruption of its obliquely arranged collagen network and sparsely distributed spherical chondrocytes. The damage then extends to the deep zone (DZ), which makes up approximately 30% of the volume and contains vertically oriented collagen fibers and columnar chondrocytes, offering maximal resistance to compressive loads. The tidemark (TM) separates the DZ from the calcified cartilage (CC), a mineralized region containing hypertrophic chondrocytes that anchor the cartilage to subchondral bone (SB). Histological sections (Fig. 1a–d) illustrate this progressive deterioration from superficial disruption to full-depth cartilage loss[36,37].

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the progression of articular cartilage degeneration. (a) Healthy joint cartilage. (b) Stage 0 to 1 of articular cartilage degeneration. (c) Stage 2 of articular cartilage degeneration. (d) Stage 3 of articular cartilage degeneration. ECM, extracellular matrix; CHs, chondrocytes; TM, tidemark; CF, collagen fibres; SBM, subchondralbone marrow; SZ, superficial zone; MZ, middle zone; DZ, deep zone; CC, calcified cartilage; SB, subchondral bone. Note: This figure was illustrated by Yatong Yang, one of the authors of this review. The histological evaluation criteria depicted were adapted from the concepts described in Vincent & Wann[38], with context-specific modifications introduced in this study.

Given the intricate molecular networks governing joint health, a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms that underpin synovial and cartilage homeostasis is critical. Such insights are essential for developing targeted interventions aimed at preserving joint function and preventing degenerative conditions. As many of these molecular pathways are closely influenced by cellular metabolic states, understanding the metabolic context of joint tissues provides additional insight into the development and progression of DJDs. Recent studies have highlighted how nutrient availability and metabolite signaling affect inflammation, cartilage turnover, and chondrocyte viability[39].

-

Despite the molecular mechanism behind joint problems in animals have been thoroughly studied, metabolites—byproducts of cellular processes—have only just come to the attention of medicinal researchers. Despite the negative effects of NSAIDs, nutritional interventions that target metabolic pathways have become viable alternatives. There is increasing evidence that glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, omega-3 fatty acids, and certain amino acids are effective in maintaining joint health[40].

Companion animals' skeletal systems are primarily supported by their bones and joints, which are mostly composed of organic materials called collagen (which is high in glycine, proline, and 4-hydroxyproline) and glycosaminoglycans. Continuous cellular turnover and bone remodeling are necessary for the preservation of these structures, and during these processes, minerals, especially Ca and P and amino acids (AAs) play important functional and metabolic functions. Through nitric oxide (NO) pathways, L-arginine primarily affects bone resorption, whereas taurine, creatine, glycine, serine, and methionine encourage the production of new bone tissue. Additionally, the production of glucosamine, proteoglycans, and glycosaminoglycan (GAGs)—all of which are vital for preserving joint health—requires AAs. The integrity of supporting ligaments and tendons, whose function depends on the collagen content of those tissues, is essential to joint stability. Collagen formation depends on AAs, especially glycine and proline, which makes them vital for total joint integrity. Furthermore, the production of glucosamine, proteoglycans, and GAGs—all essential for preserving joint health—requires certain AAs[41].

A comprehensive strategy is usually used to address OA and joint issues, which includes improving the quality of synovial fluid, controlling weight, and engaging in regulated activity[42]. Pain relief and joint inflammation reduction are greatly aided by anti-inflammatory pharmaceuticals, especially NSAIDs. It is advised to use gabapentin and amantadine as supplements or substitutes, especially in situations of neuropathic pain or NSAID intolerance. Although it works well for severe pain, the bioavailability of tramadol varies from species to species[2].

It is worth noting that prolonged use of NSAIDs can be harmful, particularly in animals that have renal dysfunction at the same time, such as those with chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). It is necessary to take NSAIDs sparingly in these individuals to prevent further impairment of renal function[43]. As a result, nutritional supplementation-based metabolic therapies have become viable treatment options. Through anti-inflammatory and chondroprotective processes, recent research has shown the effectiveness of targeted nutrient supplementation, including glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, omega-3 fatty acids, and certain AAs, in promoting joint health.

-

The bioactive compounds that are commonly included in prescription diets for supporting joint function in dogs and cats include leucine and other AAs, glucosamine and chondroitin, omega-3 fatty acids and green-lipped mussels, Type II collagen, plant polyphenols, minerals, antioxidants, and other combinations that have been identified by modern research as important nutrients that promote joint health and mobility[44].

Leucine and other amino acids

-

Leucine, a branched-chain amino acid, promotes the mTOR signaling pathway to boost muscle protein synthesis and preserve muscle mass, particularly during periods of elevated physiological stress, such as joint-related disorders or age-associated muscle atrophy. Leucine supplements improve muscular strength and function, which are essential for maintaining joint stability and general musculoskeletal health when paired with a sufficient protein diet and regular exercise[45,46].

The potential of collagen hydrolysates (CH), a blend of peptides and AAs made from collagen, as a dietary aid for dogs with OA was examined by Blees et al. Based on in vitro and animal research, the review examined CH absorption, bioavailability, and mechanisms of action, indicating possible chondroprotective benefits through decreased synovial inflammation, enhanced collagen synthesis, and decreased cartilage breakdown. After taking CH supplements, dogs with OA showed improvements in their lameness and pain levels in clinical studies. The authors did, however, point out several shortcomings in the existing literature, such as the use of non-validated outcome measures, the absence of consistent dosage, and the requirement for bigger, more carefully planned trials. Future studies should focus on determining CH bioavailability in dogs, identifying bioactive peptides, and using objective outcome measures to assess CH efficacy in managing canine OA[47]. AlRaddadi et al. investigated the anti-inflammatory effects of several creatine- and amino acid-based supplements—including creatine monohydrate (CM), creatine hydrochloride (CHCl), creatinine (CRN), and Ethyl-α(guanido-methyl) ethanoate (AlphaGEE)—in IL-1β-stimulated primary canine chondrocytes as an in vitro model of OA. All compounds significantly reduced the release of PGE2 and TNF-α in a time- and dose-dependent manner, with AlphaGEE showing the strongest effect (76% PGE2 inhibition at 8 h). These effects were associated with decreased COX-2 expression and reduced NF-κB phosphorylation. In contrast to the NSAID carprofen, which increased TNF-α despite suppressing PGE2, all supplements consistently reduced TNF-α levels. The compounds also modulated oxylipin profiles—suppressing pro-inflammatory metabolites such as 12-HETE and dihomo-PGF2α, while restoring anti-inflammatory oxylipins including 18-HEPE and 20-HDoHE—indicating multi-pathway anti-inflammatory potential. Interestingly, even creatinine, typically regarded as an inactive metabolite of creatine, demonstrated notable anti-inflammatory activity[48].

Glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate

-

In articular cartilage, the main substrate for the formation of GAG is the amino monosaccharide glucosamine[49]. Because of its hydrophilic nature and resistance to compression, chondroitin sulfate, a sulfated GAG, preserves cartilage homeostasis[50]. Both substances are structurally incorporated into the ECM of cartilage, where they support the biomechanical characteristics of joints[51]. Whereas chondroitin sulfate is taken from sources of animal cartilage, commercial glucosamine is made from bacterial fermentation or chitin found in crab shells[52]. In a randomized, controlled study, Gupta et al. showed that dogs given glucosamine hydrochloride (2,000 mg/d) and chondroitin sulfate (1,600 mg/d) showed a significant reduction in pain by day 90. On day 150, the effects peaked, with observational assessments showing a 51% reduction in overall pain, a 48% reduction in limb manipulation pain, and a 43% reduction in post-exercise pain. Nevertheless, over the 150-d treatment period, objective ground force plate tests revealed no appreciable variations in peak vertical force and impulse area[53].

Fatty acid balance and green-lipped mussels

-

Marine organisms represent the main source of the essential omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, EPA, and DHA[54]. The conversion of these fatty acids into specific pro-resolving mediators (SPMs), such as protectins and resolvins, regulates inflammatory responses[55]. Dietary supplements are required to maintain optimal levels for maintaining joint health through anti-inflammatory mechanisms because endogenous production is restricted in mammals[56].

Age-dependent cellular and functional changes were found when Lorke et al. examined the effects of dietary supplementation enhanced with antioxidants, mitochondrial cofactors, and omega-3 fatty acids on aging biomarkers in 74 shepherd dogs. Perhaps as a result of increased telomerase activity and musculoskeletal tissue support, the enriched food markedly increased the minimum telomere length and shoulder joint mobility in older dogs. According to these results, certain dietary treatments can slow down age-related physiological deterioration, with the benefits being most noticeable in elderly animals[57]. The effects of a diet with a modified omega-6 : omega-3 ratio on dogs with OA were assessed in another investigation. At 6, 12, and 24 weeks, dogs fed a diet that reduced the omega-6 : omega-3 ratio by 34 times exhibited elevated blood omega-3 fatty acids and enhanced mobility in a randomized, double-blind, controlled study. Therefore, OA symptoms may be reduced by altering the omega-6 : omega-3 ratio in dog diets[58]. Building on this, current research supports targeting an n-6 : n-3 fatty acid ratio below 10:1 for dogs and cats to optimize anti-inflammatory benefits and overall health[59].

A variety of vital vitamins and minerals, omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, including EPA, and aminoglycans like chondroitin sulfate are among the bioactive substances found in abundance in green-lipped mussels (Perna canaliculus)[60]. Eason et al. comprehensively reviewed veterinary trials investigating the therapeutic potential of GreenshellTM mussels in managing joint-related disorders across companion animals. The analysis included research on horses, dogs, and cats and found consistent evidence that nutritional supplements can reduce the symptoms of DJD and OA. A complex matrix of bioactive substances, such as carotenoids, omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, and newly discovered pro-resolving lipid mediators, were thought to be responsible for the therapeutic effectiveness. Research has shown that supplementation dosages ranging from 4 to 49 mg/kg/d can increase mobility and reduce joint discomfort[61].

Type II collagen

-

The main structural protein in articular cartilage, type II collagen, creates a fibrillar network that is necessary for the mechanical characteristics of the tissue[18]. It comes in both native and denatured (hydrolyzed) forms and is mostly derived from animal cartilage[62]. A new immunomodulatory nutraceutical that targets companion animal joint health, undenatured type II collagen (UC-II) has a distinct molecular approach from conventional supplements. To successfully mitigate immune-mediated cartilage deterioration, UC-II induces oral tolerance, which in turn activates T-regulatory cells in Peyer's patches. These cells then move to articular tissues and emit anti-inflammatory cytokines. Extensive research conducted on a variety of companion animal models (canine, horse, and feline) has methodically proven the therapeutic effectiveness of UC-II, showing notable improvements in locomotor function, mobility enhancement, and joint pain reduction with no side effects. Significantly, UC-II performed better than traditional glucosamine and chondroitin supplements, with recommended daily doses falling between 10 and 160 mg. Its safety profile has been thoroughly confirmed by rigorous toxicological tests, establishing UC-II as a potential, immunologically advanced treatment for osteoarticular diseases in companion animals[63].

Plant polyphenols

-

Joint dysfunction and persistent pain are the results of OA, a multifactorial DJD marked by subchondral bone sclerosis, synovial inflammation, and gradual cartilage degradation. Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress are key components of its pathophysiology, and they reinforce one another. Anabolic activities are suppressed, chondrocyte death is induced, and ECM breakdown occurs when reactive oxygen species (ROS) overproduction upsets redox equilibrium. Pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 also increase cartilage degradation by triggering catabolic enzymes and sustaining oxidative stress via signaling pathways like MAPK and NF-κB. Tea polyphenols, curcumin, and resveratrol are polyphenolic compounds whose anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties have been confirmed in both in vitro and in vivo models of OA[9].

Tea polyphenols

-

Tea polyphenols, a family of bioactive compounds found in green tea, are mostly catechins such as EGCG and are well known for their potent anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties[64]. According to Singh et al., OA chondrocytes' generation of NO was markedly suppressed by EGCG when IL-1β was present. The inhibition of inducible NO synthase (iNOS) mRNA and protein expression were linked to this impact in a dose-dependent manner. By blocking the breakdown of its inhibitor, IκBα, EGCG mechanistically decreased NF-κB activation by interfering with NF-κB nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity. These findings suggest that EGCG effectively mitigates IL-1β-driven inflammatory responses in OA chondrocytes through the inhibition of the NF-κB/iNOS pathway[65]. Akhtar & Haqqi demonstrated that EGCG significantly suppressed IL-1β-induced inflammatory responses in human OA chondrocytes. EGCG reduced the production of key pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, interleukin-8 (IL-8), and TNF-α, in a dose-dependent manner. The study further revealed that these inhibitory effects were mediated through the suppression of NF-κB and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) activation. Additionally, EGCG modulated the expression of chemokines and matrix-degrading enzymes, identifying new potential therapeutic targets[66]. Ahmed et al. demonstrated that EGCG effectively inhibited IL-1β-induced GAG release and the expression of MMPs (MMP-1 and MMP-13) in human chondrocytes. EGCG exhibited a differential, dose-dependent inhibitory effect on MMP expression and activity, as well as on transcription factors NF-κB and AP-1[67].

Curcumin

-

Turmeric (Curcuma longa) contains a bioactive component called curcumin, which is well known for its strong anti-inflammatory and antioxidant qualities[68]. According to Zeng et al.'s comprehensive review and meta-analysis, curcumin and extract from Curcuma longa considerably reduced OA symptoms, including joint stiffness and function as well as pain (VAS and WOMAC-pain ratings). Curcumin had significant therapeutic benefits with a safety profile similar to that of a placebo. It showed fewer side effects and was just as effective as NSAIDs. Additionally, the combination of curcumin with NSAIDs further enhanced symptom relief and functional improvement without increasing adverse effects, reinforcing its value as a safe and effective supplement for OA, particularly with long-term use of 12 weeks or more[69]. Chandran & Goel conducted a randomized pilot study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of curcumin in patients with active RA. The study demonstrated that curcumin (500 mg) significantly improved Disease Activity Score (DAS28) and American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria scores (ACR20, ACR50, and ACR70) compared to diclofenac sodium (50 mg) or their combination. Curcumin alone achieved the highest percentage of improvement, particularly in pain reduction and inflammatory markers like CRP, without adverse effects. These findings suggest curcumin as a safe and effective therapeutic option for RA, meriting further investigation in larger trials[70]. Chen et al. demonstrated that curcumin effectively attenuates MSU crystal-induced inflammation by inhibiting the degradation of IκBα and suppressing NF-κB activation. Curcumin treatment reduced mitochondrial damage, decreased ROS production, and inhibited nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome activation in macrophages. In mouse models, curcumin alleviated joint swelling, neutrophil infiltration, and inflammatory cytokine levels (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, COX-2, PGE2)[71]. In an explant model of cartilage inflammation, Henrotin et al. found that curcumin effectively mitigates IL-1β-induced ECM degradation and GAG release. Treatment with 100 μmol/L curcumin reduced GAG release triggered by IL-1β by 20% at 10 ng/mL and 27% at 25 ng/mL, bringing levels back to those of unstimulated controls, which suggests curcumin's capability to counteract cytokine-driven cartilage degradation, positioning it as a promising candidate for therapeutic use in managing OA[72].

Resveratrol

-

Resveratrol, a naturally occurring polyphenolic compound predominantly found in grape skin, red wine, and berries, has emerged as a pivotal molecule with multifaceted biological activities[73]. Collins et al. demonstrated that low oxygen tension and acidic microenvironments induce significant cellular dysfunction in equine articular chondrocytes, characterized by reduced viability, increased glycosaminoglycan release, mitochondrial membrane depolarization, and altered ROS generation. Notably, targeted antioxidant interventions using resveratrol and N-acetylcysteine effectively mitigated these deleterious processes by restoring mitochondrial membrane potential, attenuating ROS accumulation, and normalizing antioxidant enzyme expression. Mechanistically, N-acetylcysteine exhibited superior efficacy in glutathione redox balance restoration, while resveratrol primarily modulated mitochondrial function and ROS scavenging[74]. Ememe et al. investigated the effects of a joint supplement containing resveratrol and hyaluronic acid (RH supplement) on biochemical parameters in aged lame horses, which revealed that the RH supplement significantly reduced creatine kinase (CK) levels in the third week and decreased blood glucose levels in the second and third weeks compared to the control group. Other biochemical parameters, including cholesterol, urea, and electrolytes, remained within normal ranges without significant differences between groups, so these findings suggest that the RH supplement may alleviate oxidative stress-related muscle damage and hyperglycemia in aging horses, offering potential benefits for joint health and overall well-being[75].

Cannabidiol

-

Cannabidiol (CBD) is a non-psychoactive phytocannabinoid derived from Cannabis sativa[76]. It acts through multiple pathways, including modulation of cannabinoid receptors and inflammatory mediators[77]. CBD's therapeutic potential is attributed to its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, mediated through activation of cannabinoid type-2 (CB2) receptors and regulation of inflammatory cytokines[78]. In a study, the researchers assessed pet owners' perceptions and experiences with CBD use in companion animals. A survey of 1,238 participants revealed that CBD, primarily in the form of treats/chews and oils, was commonly administered to dogs and cats for conditions like anxiety, stress, and joint pain. While dosage and frequency of use were inconsistent, many owners reported improvements in their pets' condition with mild or no side effects. However, uncertainty about CBD's efficacy and safety prevented wider adoption[79].

Minerals

-

Minerals such as P and Ca are important for preserving joint health. Proteoglycan function and chondrocyte survival are unaffected by short-term Ca depletion, but low Ca concentrations severely hinder GAG synthesis; total Ca deficit reduces synthesis to 52% of normal levels. The prolonged deficit may lower proteoglycan content, which might affect cartilage's biomechanical characteristics[80].

Other antioxidants

-

Sick animals, such as those suffering from joint disorders or stress, produce more free radicals, which can contribute to oxidative damage and hasten the deterioration of joint tissue. In comparison to a placebo group, antioxidants such as vitamin C, vitamin E, and taurine are essential for scavenging free radicals, lowering oxidative stress, and safeguarding joint structures by halting cellular damage and promoting tissue healing processes[81].

Other combinations

-

To maximize the advantages of these dietary supplements for companion animals' joint health, several researchers have looked at different combinations of these nutrients. However, a thorough assessment of the formulations' safety is crucial when creating mixtures with several ingredients. Glucosamine reached a maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) of 9.69 μg/mL at 2 h post-administration and was detectable for up to 8 h, according to a pharmacokinetic study on Phycox®, a multicomponent joint supplement sold for both dogs and horses. In contrast, polyphenols were not detectable in plasma. Glucosamine and specific polyphenols were quantified using validated LC-MS/MS techniques; the results indicate that the Phycox® formulation may improve glucosamine absorption in comparison to data found in the literature[82].

Comblain et al. reported that a diet supplemented with curcuminoids extract, hydrolyzed collagen, and green tea extract (CCOT) reduced pain in dogs with OA, particularly manipulation-induced pain and pain severity scores. Although no significant improvements were observed in objective measures like ground reaction forces or OA biomarkers, the CCOT group showed a significant improvement in the ability to rise from lying down, which indicate potential benefits of CCOT in alleviating chronic pain and improving specific daily activities in osteoarthritic dogs[83]. Chen et al. demonstrated that the combination of curcumin (CUR) and catalase (CAT) effectively mitigates oxidative stress and protects chondrocytes from damage in both in vivo and in vitro models of knee osteoarthritis (KOA). In vivo, CUR and CAT synergistically reduced cartilage degradation and alleviated KOA progression, as evidenced by improvements in histopathological analysis and reduced oxidative damage. In vitro studies using primary chondrocytes isolated from SD rats demonstrated that the combination scavenged ROS, reduced lipid peroxidation, restored mitochondrial membrane potential and inhibited IL-1β-induced chondrocyte apoptosis. Mechanistically, CUR and CAT jointly activated the NRF2/heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) signaling pathway and enhanced the level of antioxidant enzymes, while reducing the levels of matrix-degrading enzymes (MMP3, MMP13) and promoting anti-apoptotic protein expression (BCL2)[84]. Martello et al. demonstrated in a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial (n = 40 dogs) that a novel multicomponent dietary supplement significantly improved clinical signs of canine OA after 60 d, as assessed by veterinary-assigned lameness scores and owner-reported HCPI, without adverse effects[85].

-

Being overweight significantly exacerbates OA because it restricts physical activity and increases mechanical stress on the joints[86,87]. Gilbert et al. found that dogs weighing above 35 kg and boxers had significantly higher OA scores in the stifle joint at the time of the diagnosis of cranial cruciate ligament (CCL) impairment[88].

Apart from the joint stress caused by obesity, excessive physical activity has also been found to be a significant risk factor for the development of OA, especially in companion animals like dogs. A series of inflammatory processes are triggered in injured joints when they are exposed to severe mechanical loading and recurrent stress. Several evidence-based lifestyle changes are advised to preserve ideal joint health and delay the onset of OA: (1) the use of structured, moderate exercise regimens that prevent excessive mechanical stress; (2) the inclusion of sufficient rest intervals in between physical activities; (3) the maintenance of healthy body weight to lessen the mechanical stress on weight-bearing joints; and (4) prompt action when joint stress symptoms are noticed, such as adjusting the duration and intensity of activity[89].

In clinical settings, body condition scoring (BCS) systems provide a standardized and objective method to assess and monitor the weight status of companion animals. Widely used 5-point or 9-point BCS scales allow veterinarians and pet owners to evaluate adiposity and guide nutritional interventions. Regular BCS assessments are essential for detecting early overweight trends and implementing timely lifestyle modifications to reduce mechanical stress on weight-bearing joints and prevent OA progression.

Nutritional interventions at different stages of the life cycle

-

In large-breed, fast-growing dogs, where excess nutrients (Ca and energy) and rapid growth increase the risk of developing skeletal problems, proper nutrition is especially important for orthopedic health. Furthermore, fatty acids can alter inflammatory and immunological responses, which can have a direct impact on the course of OA[90].

It is equally important not to overlook the role of joint-supporting nutritional supplements during energy intake management. These supplements, which often include chondroprotective agents such as glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate, and omega-3 fatty acids, play a critical role in mitigating cartilage degradation, reducing inflammation, and promoting joint health. Integrating these supplements into dietary strategies ensures a comprehensive approach to joint health, particularly in elderly animals with heightened nutritional demands and age-related metabolic changes. Older dogs exhibited more pronounced degenerative changes in cruciate ligaments and increased severity of synovitis in the stifle joint compared to younger individuals[91]. Given that many animals requiring joint-support diets are elderly, their age and associated metabolic changes must also be carefully considered when developing early intervention and age-specific management strategies to mitigate the progression of joint degeneration and inflammation. Integrating energy regulation with targeted supplementation establishes cornerstone strategies for optimizing therapeutic outcomes and enhancing the quality of life. In addition, effectively managing Lyme disease-associated joint disorders necessitates comprehensive preventive strategies, ranging from routine vaccination programs and regular tick checks to applying insect repellents before woodland exposure, especially for animals in endemic regions[92].

-

Maintaining joint health is fundamental to enhancing mobility, comfort, and overall quality of life in companion animals. Nutritional strategies—encompassing essential fatty acids, chondroprotective agents, amino acids, antioxidants, and targeted supplements—play a central role in mitigating inflammation, supporting cartilage integrity, and slowing the progression of OA. Weight control and structured physical activity further complement these interventions.

Despite encouraging evidence, critical knowledge gaps remain regarding the precise mechanisms, optimal formulations, and long-term effects of nutritional therapies. Future research should prioritize well-controlled clinical trials integrating molecular, biochemical, and biomechanical assessments to validate efficacy. Moreover, the development of personalized nutrition, informed by genetic, metabolic, and lifestyle factors, represents a promising direction for tailoring joint health interventions. Collaborative efforts among veterinarians, researchers, and the pet food industry will be key to translating these insights into effective, evidence-based dietary solutions that improve the longevity and quality of life of companion animals.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Li L; manuscript preparation: Yuan X; analysis and interpretation of results: Guo X; figure design: Yang Y; draft manuscript preparation: Guo X; manuscript revision: Farooq N, Zhu Z, Li L. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The data will be made available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Guo X, Yuan X, Farooq N, Yang Y, Zhu Z, et al. 2025. Nutritional strategies for managing joint health in companion animals. Animal Advances 2: e022 doi: 10.48130/animadv-0025-0019

Nutritional strategies for managing joint health in companion animals

- Received: 16 March 2025

- Revised: 10 April 2025

- Accepted: 15 April 2025

- Published online: 28 August 2025

Abstract: Joint health is crucial for the quality of life of companion animals, influencing their mobility, physical activity, and overall well-being. Nutritional strategies play an essential role in mitigating joint degeneration, managing inflammation, and enhancing musculoskeletal resilience across different life stages. This review explores the impact of dietary interventions, including macronutrient balance, bioactive compounds, and specialized supplementation, in maintaining joint integrity and function. Emerging evidence highlights the significance of omega-3 fatty acids, chondroprotective agents, and antioxidant-rich diets in modulating inflammatory pathways, and slowing disease progression. Additionally, tailored nutrition during growth phases is essential to prevent developmental orthopedic diseases, particularly in large-breed dogs. A lifelong, nutrition-centered approach to joint health-integrating dietary modifications with veterinary oversight offers a proactive framework for enhancing mobility, reducing disease burden, and improving the quality of life in companion animals. This review underscores the need for further research into molecular mechanisms linking diet and joint homeostasis, facilitating evidence-based dietary recommendations for veterinary practice.

-

Key words:

- Joint disorder /

- Inflammation /

- Metabolism /

- Antioxidants /

- Dietary modification /

- Companion animals