-

Aquaculture has increasingly become a vital contributor to global food security, with the cultivation of various crustacean species such as crayfish (Procambarus clarkii) experiencing rapid expansion[1]. As consumer demand for crayfish continues to increase, the imperative to enhance crayfish health and nutrition through optimized management strategies becomes more pronounced. A critical factor influencing crayfish growth, health, and overall metabolism is the composition of their diet[2,3]. Specifically, crayfish, like other aquatic species, require carefully balanced diets to support their metabolic needs, immune function, and resistance to disease. Among the macronutrients, carbohydrates are a significant component of crayfish feed and serve as an essential energy source[4]. However, high-carbohydrate diets, while cost-effective and energy-rich, pose a challenge to crayfish metabolism[4]. Excessive carbohydrate intake can cause metabolic imbalances, impair growth performance, and increase susceptibility to stress and disease[4,5].

As consumer demand for crayfish continues to increase, the imperative to enhance crayfish health and nutrition through optimized management strategies becomes more pronounced One promising approach involves supplementing natural bioactive compounds that regulate metabolic pathways and enhance physiological resilience[6−8]. Among these compounds, berberine (BBR), an isoquinoline alkaloid derived from various medicinal plants, has garnered significant attention for its broad-spectrum biological activities, particularly in improving glucose and lipid metabolism, reducing oxidative stress, and enhancing immune function[9,10]. While extensively studied in mammalian models, recent research has demonstrated its efficacy in aquatic species, such as grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella), where BBR enhances glycolytic enzyme activity to lower blood glucose and lipid levels[11]. In blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala), it significantly boosts antioxidant defenses by increasing superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase activities, thereby mitigating oxidative stress-induced damage[12]. Moreover, studies on yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco) indicate that BBR enhances immune function by promoting the proliferation of beneficial probiotic bacteria, leading to a healthier gut microbiome[13], while in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), it improves growth performance by enhancing feed utilization and metabolic efficiency[14]. These findings suggest that BBR may exert similar benefits in crayfish, particularly in high-carbohydrate diets that can induce metabolic imbalances. By facilitating carbohydrate utilization, regulating key metabolic pathways, and strengthening antioxidant and immune defenses, BBR has the potential to enhance growth, health, and resilience, offering a promising dietary intervention in crayfish aquaculture.

Although BBR has shown promising effects in modulating metabolism and enhancing immune function in various species, the exact mechanisms by which it influences crayfish metabolism, particularly in the context of a high-carbohydrate diet are not yet fully understood. Clarifying these mechanisms is essential for developing effective dietary strategies that can optimize crayfish health and productivity, especially in aquaculture systems where high-carbohydrate diets are commonly employed for cost efficiency. Moreover, with increasing concerns about the environmental sustainability of aquaculture practices, identifying natural, safe, and cost-effective supplements that can improve feed efficiency and reduce disease prevalence is becoming more critical[4].

This study seeks to evaluate the effects of BBR supplementation on the metabolic and immune responses of P. clarkii fed a high-carbohydrate diet, with a specific focus on glucose and lipid metabolism, oxidative stress markers, and immune-related gene expression. By analyzing these physiological parameters, we aim to determine whether BBR can mitigate the negative impacts of excessive carbohydrate intake, thereby enhancing crayfish health. The findings of this research could provide valuable insights into crayfish nutrition, contributing to the development of more health-conscious dietary formulations in aquaculture. As the industry continues to expand, functional feed additives like BBR may play a crucial role in promoting animal health, reducing reliance on chemical treatments, and improving sustainability. Ultimately, this research seeks to advance our understanding of bioactive compounds in aquaculture diets, with the broader goal of optimizing productivity while safeguarding the welfare of cultured species.

-

The formulation and composition of the experimental diets are summarized in Table 1, where corn starch was employed as the principal carbohydrate source to adjust carbohydrate levels. Three specific dietary treatments were designed for this study: a normal carbohydrate diet (NCD) with 33% carbohydrates, a high carbohydrate diet (HCD) containing 41% carbohydrates, and a high carbohydrate diet supplemented with BBR (HCB), which consisted of 41% carbohydrates plus 50 mg/kg of BBR. The BBR was supplied by Nanjing Chunqiu Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China, and its dosage was selected based on prior studies conducted in our laboratory[15].

Table 1. Formulation and proximate composition of the experimental diets.

NCD HCD HCB Ingredients (% dry weight) Fish meal 14.80 14.80 14.80 Soybean meal 19.80 19.80 19.80 Peanut meal 11.88 11.88 11.88 Cottonseed meal 11.88 11.88 11.88 Corn starch 17.06 25.18 25.18 α-starch 4.96 4.96 4.96 Fish oil 3.25 3.25 3.25 Beef tallow 3.25 3.25 3.25 Calcium dihydrogen phosphate 2.20 2.20 2.20 Sodium chloride 0.40 0.40 0.40 Premixa 1.00 1.00 1.00 Chitin 0.15 0.15 0.15 Cholesterol 0.10 0.10 0.10 Lecithin 0.15 0.15 0.15 Microcrystalline cellulose 8.12 0 0 BBR 0 0 0.005 Sodium carboxymethyl cellulose 0.50 0.50 0.50 Ethoxyquin 0.50 0.50 0.50 Proximate analysis (%) Water content 10.71 10.25 10.43 Crude protein 31.11 30.42 30.47 Crude lipid 6.78 7.15 6.86 Crude ash 7.65 7.51 7.79 Carbohydrate 32.43 40.88 40.91 Energy 19.46 19.87 19.85 a The micronutrients contained in the premix are as follows: vitamins (mg or IU/kg) include: CoCl2·6H2O, 0.1 g; MnSO4·4H2O, 7g; KI, 0.026 g; FeSO4·7H2O, 25 g; Na2SeO3, 0.04 g; ZnSO4·7H2O, 22 g; CuSO4·5H2O, 2 g; minerals (g/kg) include :Vitamin A, 1,500,000 IU; Vitamin E, 5,000 mg; Vitamin K3, 220 mg; Vitamin B2, 1090 mg; Vitamin B12, 15 mg; Vitamin B1, 320 mg; Vitamin B5, 2,000 mg; Vitamin B6, 500 mg; Vitamin C, 14,000 mg; Pantothenate, 1,000 mg; Folic acid, 230 mg; Choline, 60,000 mg; Biotin, 130 mg; Myoinositol 45,000 mg; Niacin, 3,000 mg; Vitamin D, 200,000 IU. Calculated by difference (100 - moisture - crude protein - crude lipid - ash - crude fiber). All ingredients were carefully weighed and mixed to ensure uniform distribution, then passed through a 0.25 mm mesh for consistency. The mixture was subsequently processed into pellets using a single-screw meat grinder (JR-32, Baicheng Co., Guangzhou, China). These pellets were air-dried for 24 h in a well-ventilated space, broken into sizes suitable for crayfish consumption, vacuum-sealed in plastic bags, and stored at −20 °C until feeding.

Experimental crayfish and feeding management

-

The crayfish used in this study were sourced from a commercial aquaculture facility located in Pukou City, Jiangsu Province, China. After a one-week acclimatization period, during which the crayfish were fed a commercially available diet from Haipurui Feed Co., Ltd. (Taizhou, Jiangsu) that closely mirrors the nutritional profile of the NCD diet, a total of 168 crayfish with an average initial body weight of 14.1 g were selected for the feeding trial. These crayfish were then randomly distributed across 12 cement tanks, each measuring 1.0 m in length, width, and height. Each tank housed 14 crayfish, composed of seven males and seven females, and the experimental design incorporated four replicates per treatment group.

The crayfish were fed twice daily, with a feeding rate equivalent to 3%−5% of their body mass. The feeding period lasted for eight weeks, during which the crayfish were reweighed every two weeks to accurately adjust the feeding quantity based on their growth. To ensure optimal water conditions, water changes were performed every three days, with one-third of the tank's water volume being replaced each time. In conjunction with water changes, uneaten feed, and waste material were removed from the tanks. Key water quality parameters, including temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, and ammonia nitrogen levels, were regularly monitored and maintained within the following ranges: maintaining a temperature of 28 ± 2 °C, pH at 7.39 ± 0.13, dissolved oxygen at 5.72 ± 0.36 mg/L, and ammonia nitrogen concentrations kept below 0.05 mg/L. This meticulous management of water quality and feeding practices ensured a controlled environment for evaluating the effects of dietary interventions on crayfish health.

Sample collection

-

After the eight-week feeding trial, five crayfish were randomly selected from each treatment group and anesthetized by placing them on ice. Hemolymph was collected from each crayfish using a 2-ml syringe preloaded with 1 ml of anticoagulant solution (0.14 M NaCl, 0.1 M glucose, 30 mM trisodium citrate, 26 mM citric acid, and 10 mM EDTA, pH 4.6), which was inserted into the pericardial cavity to extract 1 ml of hemolymph. The collected hemolymph was transferred into a centrifuge tube, and centrifuged at 3,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C[16]. The resulting supernatant was carefully collected and stored at −80 °C for subsequent biochemical analyses.

After hemolymph extraction, the crayfish were dissected to collect tissue samples. Both the hepatopancreas and muscle tissues were harvested, with portions immediately stored at −80 °C for long-term preservation, while other sections were stored at −20 °C for additional analyses. This comprehensive sampling ensured the collection of high-quality biological materials for assessing the physiological and metabolic impacts of the dietary treatments, particularly the influence of BBR supplementation on crayfish under a high-carbohydrate diet.

Analytical procedures

Growth performance evaluation

-

The growth performance of crayfish was assessed using several key metrics, including mass gain rate (MGR), specific growth rate (SGR), feed conversion ratio (FCR), survival rate (SR), hepatopancreas index (HI), and meat yield (MY). These parameters were calculated using the following equations:

$ \mathrm{MGR\,({\text{%}} )=(Mt-M0)\times 100/T} $ $ \mathrm{SGR\, (\text{%}\; day^{-1})=(LnWt-LnW0)\times100/T} $ $ \mathrm{SR\, (\text{%})=Final\; crayfish\; number/Initial\; crayfish\; number\times100} $ $ \mathrm{FCR\, (\text{%})=Feed\; intake/Total\; wet\; weight\; gain} $ $ \mathrm{HI\, ({\text{%}})=(Hepatopancreas\; weight/Body\; weight)\times100} $ $ \mathrm{MY\,({\text{%}} )=Muscle\;weight/Wt} $ T is the rearing duration in days. The total feed intake was estimated based on the calculated feeding regime, provided as a fixed proportion of the crayfish body weight throughout the experiment.

Proximate composition analysis

-

The proximate composition of crayfish and experimental diets was determined using standardized methods as outlined by the Association of Official Analytical Chemists[17]. The moisture content was determined by drying the sample to a constant weight at 105 °C. Crude protein content was measured via an automated Kjeldahl nitrogen analysis system (KT260; Foss, Zürich, Switzerland). Crude ash content was determined after combusting the samples in a muffle furnace at 550 °C for 4 h. Ether extraction using the Soxhlet method was employed to quantify crude lipid content, while crude fiber was measured using a glass crucible method with an automated fiber analyzer (ANKOM A2000i, USA). Total energy content was determined using a bomb calorimeter (Parr 1281; Parr Instrument Company, Moline, IL, USA), ensuring a comprehensive assessment of the nutritional composition of both feed and crayfish samples.

Immune function and antioxidant capacity assays

-

To evaluate the immune response and antioxidant defenses of crayfish, several key enzymatic activities were measured in the hemolymph and hepatopancreas using commercial kits from the Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China). Hemolymph samples were analyzed for acid phosphatase (ACP; Cat. No. A060-2), alkaline phosphatase (AKP; Cat. No. A059-1), alkaline phosphatase (ALP; Cat. No. A059-2), aspartate aminotransferase (AST; Cat. No. A010-2), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT; Cat. No. A009-2). In hepatopancreas tissue, superoxide dismutase (SOD; Cat. No. A001-3), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-px; Cat. No. A005-1), and malondialdehyde (MDA; Cat. No. A003-1) levels were measured, assessing the oxidative stress and antioxidant capacity of crayfish.

The assays were carried out following the manufacturers' protocols, with enzyme activity measured through colorimetric analysis, and the absorbance readings taken using a UV-visible spectrophotometer. These measurements allowed for precise quantification of the crayfish's physiological response to the experimental diets, particularly regarding immune competence and oxidative stress management.

Glucose metabolism and biochemical analysis

-

Glucose metabolism was assessed by measuring glucose (Cat. No. A006-1), triglyceride (Cat. No. A110-1), and total cholesterol (Cat. No. A111-1) concentrations in hemolymph samples using commercially available kits from Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China). Glycolytic enzyme activity was evaluated by analyzing pyruvate kinase (PK) and hexokinase (HK) activities in the hepatopancreas, with a UV spectrophotometer used to determine their kinetic profiles.

Glycogen levels in tissues were determined following the method of Roehrig & Allred[18]. Total RNA was extracted from hepatopancreas samples using the RNAiso Plus Kit (Cat. No. 9109, TaKaRa, Co. Ltd., Dalian, China) as per the manufacturer's instructions. The quality and concentration of RNA were assessed using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). RNA purity was confirmed by analyzing the absorbance ratio at 260 and 280 nm, and RNA integrity was evaluated via formaldehyde denaturation agarose gel electrophoresis.

Complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis was conducted using the PrimeScript™ RT Master Mix Kit (Cat. No. RR036A, TaKaRa, Co. Ltd., Dalian, China), following the manufacturer's instructions. The cDNA was diluted in diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water and used as the template for quantitative PCR. Real-time PCR reactions were conducted using the TB Green™ Premix Ex Taq™ (Tli RNaseH Plus) Kit (Cat. No. RR420A, TaKaRa, Co. Ltd.) on an ABI7300 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Each PCR reaction was prepared in a 20 μL volume, comprising 10 μL of TB Green™ Premix, 0.8 μL each of forward and reverse primers (10 μM), 0.4 μL of ROX reference dye (50×), 2.0 μL of cDNA template, and 6.0 μL of distilled water. The amplification protocol consisted of an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s, and 60 °C for 30 s. Specificity was verified via melting curve analysis and agarose gel electrophoresis. Gene expression was quantified using the 2−ΔΔCᴛ method[19], with eukaryotic translation initiation factor (EIF) serving as the reference gene[20]. All primer sequences used for quantitative PCR are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Primer sequences for real-time fluorescence quantification of PCR.

Target gene Primer sequence (5'-3') Amplicon size (bp) GLUT1 F: TTTTCGAGTTCGTCGGAGGG 100 R: ATCTGGCCGCAGTACACAAA Gys F: AGCTTCGCTGAAGGGAACAA 197 R: CACAGCTTGGCTTGGAACAC HK F: GTGGGGTGCGTTTGGAGATA 147 R: ACCTCCCGATACAGGTCTCC PK F: AGCGGACTGTGTCATGTTGT 76 R: ATTAGCCATTGTTCGCACGC PFK F: GGAATGTACGTAGGGGCTCG 151 R: CCTTGCACCTAGCTGAACCA PEPCK F: TGTCCCATCATTGACCCTGC 120 R: GTGCTTCCAGTCGTAGGCTT G6P F: CGGAGCGGACTGTTCTTCAT 143 R: TTGGACCACTCGCAGAAGAC PC F: ACTCCCCAGGGATGTGCTAT 130 R: AAGCACCGTCAAGGCGAATA Glucose transporter 1, GLUT 1; Glycogen synthase, Gys; Hexokinase, HK; Pyruvate kinase, PK; Phosphofructokinase, PFK; Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, PEPCK; Glucose-6-phosphatase, G6P; Pyruvate carboxylase, PC. Statistical analysis

-

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied to compare data from the NCD, HCD, and HCB treatment groups, followed by Tukey's post-hoc test to assess statistical significance between means. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 24.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

-

To assess the impact of BBR supplementation on the growth performance of crayfish subjected to a HCD, an 8-week feeding experiment was conducted using three dietary treatments: NCD, HCD, and HCB. Several growth parameters were analyzed, including initial and final weights, FCR, SR, WGR, SGR, HI, and MY, as shown in Table 3. Although crayfish fed with the HCD exhibited a trend of reduced growth performance compared to those on the NCD, these differences did not reach statistical significance. However, the addition of BBR in the HCB group appeared to mitigate some of the negative impacts associated with the HCD, though these improvements were not statistically significant.

Table 3. Growth performance of Procambarus clarkii.

Parameter NCD HCD HCB IM (g) 14.19 ± 0.13 14.29 ± 0.14 14.22 ± 0.22 FM (g) 29.92 ± 0.54 29.11 ± 0.48 29.14 ± 0.76 FCR 2.67 ± 0.08 2.87 ± 0.16 2.87 ± 0.14 SR (%) 100 ± 0.00 94.64 ± 3.42 98.21 ± 1.79 MGR (%) 112.01 ± 2.03 104.30 ± 5.24 105.86 ± 6.21 SGR (% day−1) 1.33 ± 0.19 1.27 ± 0.02 1.28 ± 0.07 HI (%) 4.81 ± 0.23 4.47 ± 0.22 4.72 ± 0.10 MY (%) 10.02 ± 0.18 10.42 ± 0.28 9.92 ± 0.20 IM, initial body mass; FM, final body mass; FCR, feed conversion ratio; SR, Survival rate; MGR, mass gain rate; SGR, specific growth rate; HI, hepatopancreas index; MY, meat yield. There were no significant differences by ANOVA. Whole-body composition

-

The proximate composition of the crayfish body was analyzed, and the results are presented in Table 4. Neither the increase in dietary carbohydrate levels nor the inclusion of BBR in the HCB diet produced significant changes in the body composition of crayfish. Measured components such as crude protein, crude fat, ash, and moisture content remained comparable across all dietary treatments, indicating that BBR supplementation did not induce any measurable alterations in nutrient storage or allocation in the crayfish body.

Table 4. Body composition of Procambarus clarkii (wet mass basis, %).

Whole-body composition NCD HCD HCB Water content 67.06 ± 1.11 67.26 ± 1.82 65.61 ± 1.42 Crude protein 12.84 ± 0.02 12.05 ± 0.03 12.14 ± 0.22 Crude lipid 2.40 ± 0.16 2.27 ± 0.11 2.17 ± 0.06 Crude ash 11.89 ± 0.07 12.20 ± 0.56 12.43 ± 0.25 Energy 14.70 ± 0.02 15.15 ± 0.19 14.70 ± 0.14 There were no significant differences among the groups by ANOVA. Immunity and antioxidant capacity

-

To explore the potential of BBR in counteracting the immune and oxidative stress impairments caused by an HCD, a range of immunological and antioxidant parameters were evaluated (Table 5). No significant changes were observed in hemolymph levels of AKP, ACP, ALT, and AST among the different diet groups. However, the antioxidant activity, particularly SOD, was significantly reduced in the HCD group compared to the NCD group, suggesting oxidative stress induced by the high carbohydrate intake. Notably, BBR supplementation in the HCB group significantly restored SOD activity to near-normal levels, mitigating the oxidative damage observed in the HCD group. Additionally, MDA and GSH-px activities were significantly elevated in the HCD group relative to the NCD group (p < 0.05), but BBR supplementation effectively reduced these elevated levels, indicating improved antioxidant defenses in crayfish fed the HCB diet.

Table 5. The immunity and antioxidant capacity of Procambarus clarkii.

Parameter NCD HCD HCB Hemolymph ACP (KA unit/100 ml) 2.08 ± 0.07 1.93 ± 0.09 2.01 ± 0.06 AKP (KA unit/100 ml) 1.28 ± 0.05 1.20 ± 0.05 1.28 ± 0.09 ALT (U/L) 17.81 ± 0.62 19.46 ± 0.45 19.12 ± 0.68 AST (U/L) 1.26 ± 0.17 1.49 ± 0.14 1.28 ± 0.20 Hepatopancreas SOD (U/mg protein) 53.08 ± 1.09a 46.28 ± 1.47b 55.90 ± 2.45a GSH-px (U/mg protein) 2.27 ± 0.24a 5.03 ± 0.26b 2.67 ± 0.56a MDA (nmol/mg protein) 2.27 ± 0.24a 5.03 ± 0.26b 2.67 ± 0.56a ACP, phosphatase; AKP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; SOD, superoxide dismutase; GSH-px, glutathione peroxidase; MDA, malondialdehyde. Means in the same rows with different superscripts were significantly different (p < 0.05) by ANOVA. Glucose metabolism and biochemical parameters

-

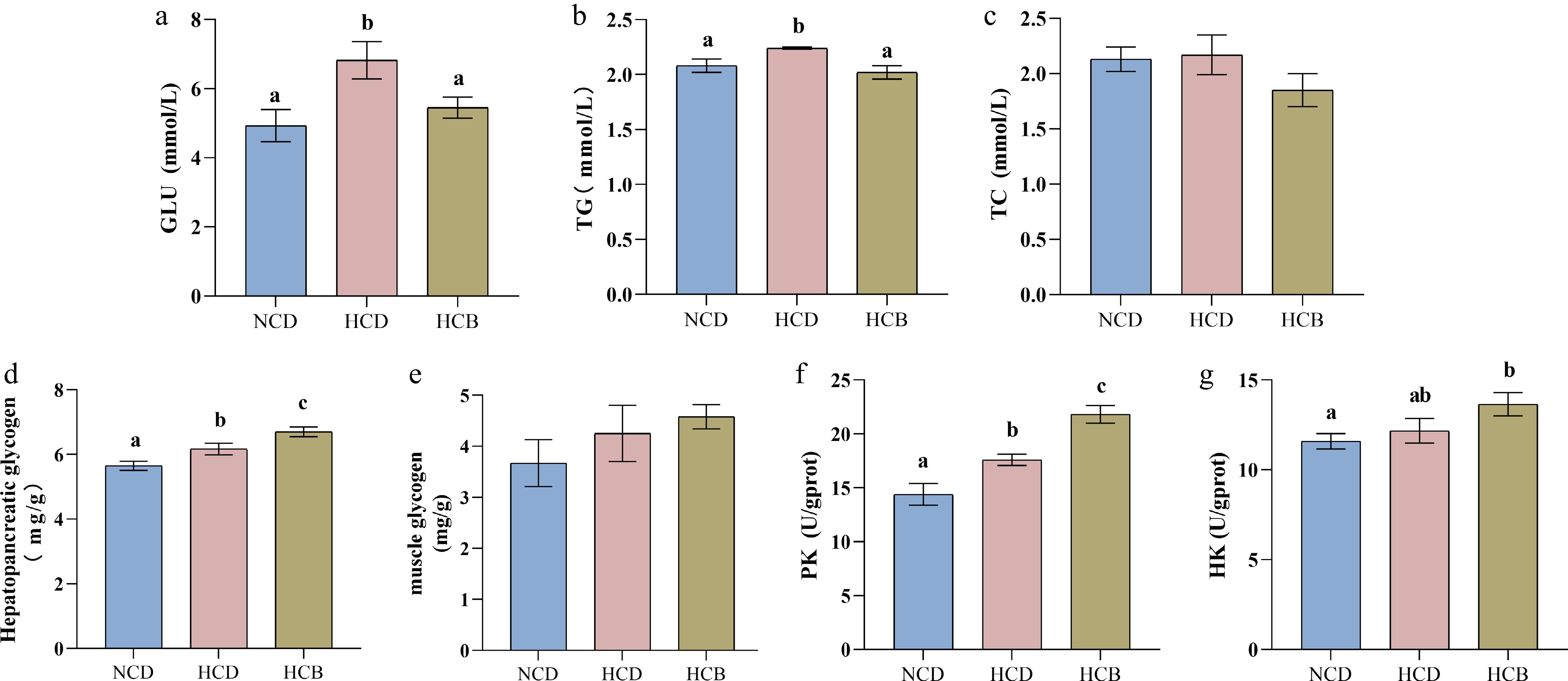

The effects of dietary treatments on hemolymph biochemical markers were also investigated. Crayfish fed the HCD exhibited significantly elevated blood glucose and TG levels compared to those in the NCD group, suggesting that excessive carbohydrate intake negatively affected glucose and lipid metabolism (Fig. 1a, b). Interestingly, BBR supplementation in the HCB group significantly reduced both blood glucose and TG levels, indicating an amelioration of the metabolic disturbances induced by the HCD. No significant changes in total cholesterol were detected across all dietary groups (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1.

Effect of BBR on blood biochemistry and glycolysis in Procambarus clarkii. (a), glucose (GLU) in the hemolymph, (b) triglyceride (TG) in the hemolymph, (c) total cholesterol (TC) in the hemolymph, (d) hepatopancreatic glycogen, (e) muscle glycogen, (f) hexokinase (HK) in the hepatopancreas, and (g) pyruvate kinase (PK) in the hepatopancreas. The notable difference of the means of each group in the same indicator is represented by different lowercase letters (p < 0.05) by ANOVA.

Muscle glycogen content showed no statistically significant differences between treatments, though an increasing trend was observed across the HCD and HCB groups (Fig. 1e). In contrast, liver glycogen content was significantly higher in crayfish fed the HCD compared to those on the NCD (Fig. 1d), suggesting enhanced glycogen storage in the hepatopancreas as a result of carbohydrate overconsumption. Furthermore, BBR supplementation further increased liver glycogen storage compared to the HCD group alone. Consistent with these observations, the activities of key glycolytic enzymes, PK and HK, were significantly elevated in the hepatopancreas of crayfish fed the HCD relative to the NCD group (Fig. 1f, g). Notably, BBR supplementation resulted in a further increase in the activities of PK and HK, indicating an enhanced glycolytic flux in response to BBR in crayfish fed a high-carbohydrate diet.

Gene expression related to carbohydrate metabolism

-

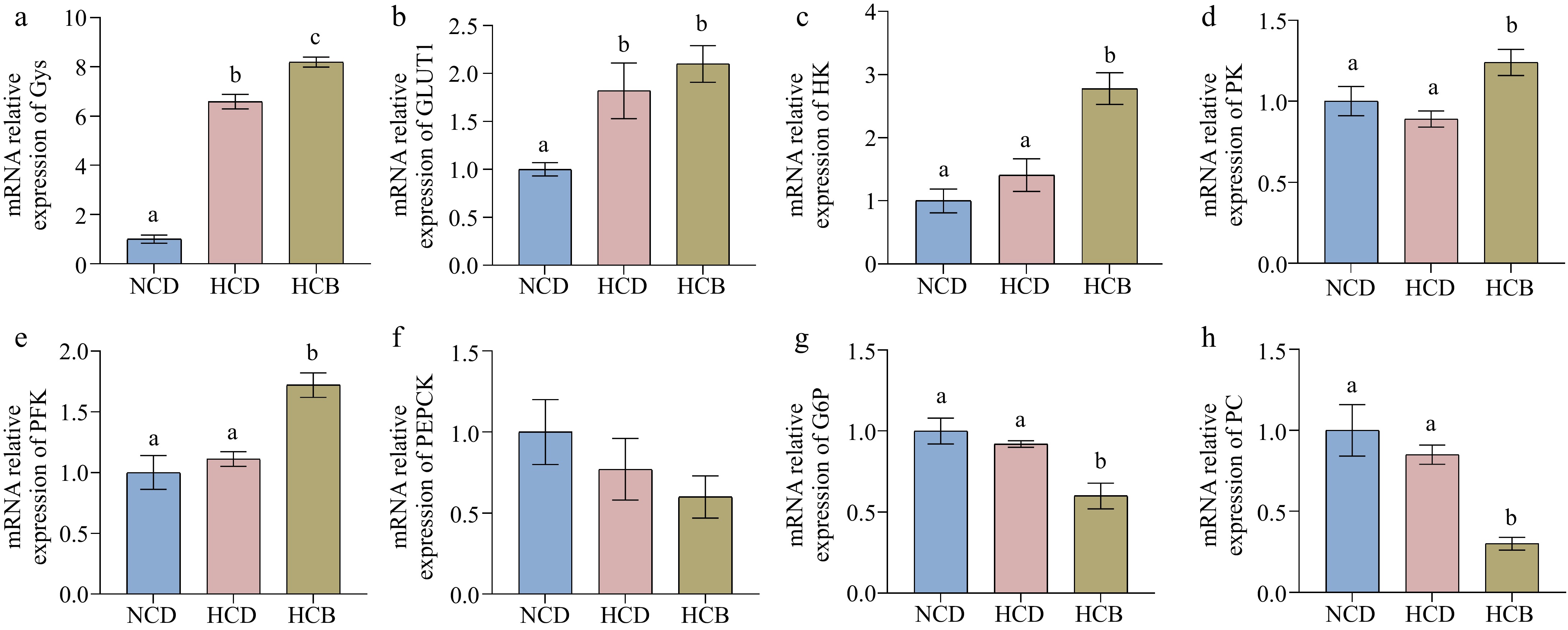

The expression of genes involved in carbohydrate metabolism was assessed in the hepatopancreas to further elucidate the mechanisms by which BBR influences metabolic responses (Fig. 2). The mRNA expression of glycogen synthase (Gys), a key enzyme in glycogen synthesis, was significantly upregulated in the HCD group compared to the NCD group. Moreover, BBR supplementation in the HCB group further enhanced Gys expression compared to the HCD group alone, suggesting that BBR promotes glycogen accumulation (p < 0.05, Fig. 2a). Glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) expression was also higher in both the HCD and HCB groups than in the NCD group (p < 0.05, Fig. 2b), indicating increased glucose uptake in response to higher carbohydrate intake.

Figure 2.

Effect of BBR on glucose metabolism related genes in the hepatopancreas of Procambarus clarkii. (a) Glycogen synthase (Gys), (b) glucose transporter 1 (Glut1), (c) hexokinase (HK), (d) pyruvate kinase (PK), (e) phosphofructokinase (PFK), (f) phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, (PEPCK), (g) glucose-6-phosphatase (G6P), and (h) pyruvate carboxylase (PC). The notable difference in the means of each group of the same indicator is represented by different lowercase letters (p < 0.05) by ANOVA.

The mRNA expression of other glycolytic enzymes, including hexokinase (HK), pyruvate kinase (PK), and phosphofructokinase (PFK), did not differ significantly between the NCD and HCD groups. However, these genes showed a notable increase in expression in the HCB group compared to both the NCD and HCD groups (Fig. 2c−e), implying that BBR supplementation enhances glycolytic activity at the transcriptional level.

Conversely, genes associated with gluconeogenesis, such as glucose-6-phosphatase (G6P) and pyruvate carboxylase (PC), showed no significant differences in expression between the NCD and HCD groups (Fig. 2g, h). However, their expression levels were significantly reduced in the HCB group, suggesting that BBR suppresses gluconeogenic activity in crayfish fed a high-carbohydrate diet. Similarly, the expression of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK), another key enzyme in gluconeogenesis, followed a similar trend, although the differences were not statistically significant across the groups (Fig. 2f).

-

While high-carbohydrate (HC) diets offer economic advantages in aquaculture, numerous studies have documented their adverse effects on aquatic species, particularly concerning metabolism and growth[4]. Additives such as resveratrol, taurine, and alpha-lipoic acid have been investigated for their potential to alleviate HC diet-induced metabolic disturbances, particularly in glucose metabolism, insulin sensitivity, and lipid accumulation[21−23]. However, side effects such as increased fat deposition limit their long-term application[21−23]. In contrast, BBR, a bioactive compound extensively studied in mammals, shows promise for improving metabolic health due to its broad bioactivity and minimal side effects[24]. In mammalian models, BBR has been shown to regulate energy metabolism, improve blood glucose control, enhance lipid metabolism, and reduce inflammation, primarily through activation of the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway[25]. Its role in reducing hepatic lipid accumulation and improving insulin sensitivity supports its potential as a functional feed additive[13,14]. However, studies on BBR in aquatic species, particularly crustaceans, remain limited. Aquatic species, with generally lower carbohydrate utilization capacities, are more prone to metabolic disorders such as glucose intolerance and lipid accumulation when fed HC diets[4]. In species like Nile tilapia, BBR has demonstrated the potential to improve glucose and lipid metabolism, enhance growth performance, and boost antioxidant capacity[9]. This study is the first to investigate the metabolic effects of BBR in crayfish, addressing a significant gap in the literature.

Our study assessed whether BBR supplementation could mitigate the negative effects of HC diets on crayfish growth performance. Results indicated no significant differences in key growth parameters, including SGR, WGR, FCR, and SR, among crayfish fed a NCD, HCD, and HCB. These findings align with previous research on other species, such as M. amblycephala and C. idella, where BBR showed no significant impact on growth performance[11,26]. This lack of effect could be due to an insufficient BBR dosage or the possibility that BBR's influence is more pronounced in metabolic regulation than growth promotion.

While not statistically significant, the HCD group exhibited a trend of reduced growth, consistent with studies suggesting that excessive carbohydrate intake can disrupt metabolic homeostasis and impair growth[27]. HC diets are known to cause glucose intolerance and lipid accumulation, which can hinder optimal growth[28]. The absence of growth improvement in the HCB group suggests that BBR's effects, under the conditions tested, may be more focused on metabolic regulation rather than directly enhancing growth[25]. Additionally, the distinct metabolic and physiological characteristics of crayfish, compared to fish, may account for the lack of growth enhancement[29]. Further research is required to optimize BBR dosage, supplementation strategies, and environmental conditions to fully explore its potential benefits for crayfish growth performance.

The body composition analysis confirmed that BBR supplementation did not significantly affect nutrient storage and utilization in crayfish, with no notable differences in crude protein, lipid, moisture, or ash content among groups. These results are consistent with findings in M. amblycephala and black seabream, suggesting that BBR has limited effects on body composition in aquatic species[10,12]. The key takeaway is BBR's neutral impact on lipid accumulation, avoiding excessive fat deposition commonly seen with other metabolic regulators such as resveratrol or alpha-lipoic acid[23,30]. While these regulators may improve glucose metabolism, their tendency to promote fat accumulation limits broader use in aquaculture. In contrast, BBR's neutral effect on lipid storage suggests it may serve as a safer long-term supplement, without compromising nutritional efficiency in aquaculture systems. Thus, BBR holds promise, particularly for balancing growth performance and metabolic regulation.

Further investigation into BBR's metabolic effects revealed its significant role in mitigating metabolic imbalances induced by HC diets. Crayfish in the HCB group showed significantly lower blood glucose and TG levels compared to the HC group, highlighting BBR's role in addressing metabolic disturbances. These findings are consistent with previous studies demonstrating BBR's broad effects on glucose and lipid metabolism. For example, Liu et al. reported that BBR significantly reduced blood glucose and improved lipid metabolism in Nile tilapia[14]. In this study, the upregulation of genes associated with glucose metabolism, such as GLUT1 and Gys, in the HCB group suggests that BBR enhances energy utilization in crayfish by promoting glucose uptake and glycogen storage. These metabolic improvements may not only counteract the negative effects of HC diets but also support better growth performance in aquatic animals.

Although the specific molecular mechanisms of BBR in crayfish were not fully explored in this study, it is likely that BBR acts through pathways similar to those seen in mammals. In mammalian models, BBR activates the AMPK signaling pathway, a key regulator of cellular energy balance that responds to energy deficiency or metabolic stress. AMPK activation promotes glucose uptake, glycogen synthesis, and fatty acid oxidation while inhibiting lipid synthesis[31]. Previous studies have shown that BBR lowers blood glucose and improves lipid metabolism in mammals and fish through AMPK activation[31,32]. In our study, the increased expression of glycolytic enzymes such as HK and PK, as well as Gys, in the HCB group suggests a similar AMPK-dependent mechanism in crayfish[33]. This mechanism reinforces the potential of BBR as a functional additive in aquaculture, mitigating the metabolic stresses of HC diets in aquatic species.

Another key finding of this study was the enhancement of antioxidant capacity. BBR supplementation significantly restored SOD activity and lowered MDA levels, indicating a substantial reduction in oxidative stress induced by HC diets. This is consistent with Ming et al. in Juvenile Black Carp, where BBR improved antioxidant capacity and reduced oxidative stress markers[34]. These results suggest that BBR helps alleviate HC diet-induced oxidative stress by modulating antioxidant defense mechanisms, thereby improving crayfish resilience to environmental stress. Interestingly, BBR supplementation did not significantly affect immune-related indicators in crayfish, which aligns with previous studies[35,36]. Moderate carbohydrate intake can enhance immune function, but excessive intake may impair it[37]. The absence of immune function enhancement could also be attributed to immune fatigue, a phenomenon where prolonged exposure to immune stimulants leads to weakened immune responses over time[12,38]. Research in shrimp and other crustaceans suggests that intermittent supplementation with immune-enhancing compounds may be more effective than continuous feeding[38,39]. This approach could potentially improve the immunomodulatory effects of BBR in crayfish. Future studies should explore optimal supplementation protocols, including frequency and dosage, to determine whether BBR can enhance immune function in crayfish. Although no significant changes in immune-related enzyme expression were observed, the improvement in antioxidant defenses suggests that BBR may still contribute to enhanced immune resilience. Previous research has shown that BBR can modulate immune responses by reducing inflammatory markers and enhancing immune cell activity, potentially increasing disease resistance in aquatic species[40].

Overall, this study has important implications for aquaculture, especially in improving crayfish health under HC diets. BBR improved glucose utilization, reduced lipid accumulation, and enhanced antioxidant defenses, highlighting its potential as a functional feed additive to counter the negative effects of HC diets. By improving metabolic efficiency and reducing oxidative stress, BBR may enhance overall health and disease resistance in crayfish, potentially improving growth performance and reducing disease risks. Additionally, BBR's regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism without significantly altering body composition suggests it is a safe and sustainable option for improving crayfish growth performance and survival, ultimately enhancing the economic efficiency and sustainability of crayfish aquaculture.

Future research should further evaluate BBR's effects across various aquatic species and explore its long-term impact and dose-response relationships. Investigations into the feasibility of large-scale commercial application of BBR, including its economic viability, environmental impact, and stability during feed processing, are also necessary.

-

In conclusion, although BBR supplementation did not significantly improve growth performance in crayfish fed an HC diet, it played a crucial role in regulating glucose and lipid metabolism, enhancing glycogen storage, and improving antioxidant defenses. These metabolic improvements suggest that BBR could be a valuable tool for mitigating the negative effects of HC diets in aquaculture. Future research should explore the long-term effects of BBR supplementation and optimize its dosage and application methods to maximize its benefits in crayfish and other aquatic species. By advancing our understanding of bioactive compounds in aquaculture, this study contributes to the development of more sustainable and health-oriented feeding strategies.

-

All experimental procedures involving animals were reviewed and preapproved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Nanjing Agricultural University (Permit number: IACUC2019548, approval date: 2020.09). The study strictly followed institutional and international ethical guidelines for animal research. The research also adhered to the principles of Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement to minimize animal harm. Details regarding animal housing, care, and pain management are provided to ensure minimal impact on the animals during the experiment.

This work was supported by the Jiangsu Agricultural Industry Technology System (Grant Nos JATS [2023] 471 and JATS [2023] 441).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Wen C, Zhang D; methodology: Wen C, Jia X, Zhu C; investigation, formal analysis: Wen C; visualizations: Wen C, Ma S; writing - draft manuscript preparation: Wen C, Jia X, Tian H; software: Jia X, Zhu C, Tian H, Ma S, Jiang W; data analysis: Jia X, Ma S, Jiang W; validation: Tian H; funding acquisition: Wang A (lead), Liu W; funding securing, project administration: Zhang D; resources: Wang A, Liu W; study design: Wang A; project supervision: Liu W, Zhang D; writing - critical reviews: Fang X; writing - manuscript editing: Fang X, Zhang D. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare no conflicts of interest that could have affected the outcomes or interpretations presented in this work. Dingdong Zhang is the Editorial Board member of Animal Advances who was blinded from reviewing or making any decisions on this manuscript. The article followed the journal's standard procedures, with peer review conducted independently of this Editorial Board member and the research groups.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Abstract graphic for this study.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wen C, Jia X, Zhu C, Fang X, Tian H, et al. 2025. Berberine supplementation enhances antioxidant defense and glucose metabolism in crayfish (Procambarus clarkii) fed a high-carbohydrate diet. Animal Advances 2: e020 doi: 10.48130/animadv-0025-0018

Berberine supplementation enhances antioxidant defense and glucose metabolism in crayfish (Procambarus clarkii) fed a high-carbohydrate diet

- Received: 08 January 2025

- Revised: 14 March 2025

- Accepted: 14 April 2025

- Published online: 23 July 2025

Abstract: This study evaluated the impact of berberine (BBR) supplementation on growth, immune function, antioxidant capacity, and glucose metabolism in Procambarus clarkii fed a high-carbohydrate diet (HCD). Crayfish were assigned to three groups: a normal-carbohydrate diet (NCD, 33%), HCD (41%), and HCD with 50 mg/kg BBR (HCB). After an 8-week trial, no significant differences were observed in growth performance or body composition. However, BBR supplementation significantly improved antioxidant capacity by restoring superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity and reducing levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px). BBR also mitigated HCD-induced hyperglycemia and hypertriglyceridemia, while increasing hepatic glycogen content and promoting glycolytic enzyme activities (pyruvate kinase and hexokinase). Additionally, BBR elevated the expression of glycogen synthase and glycolysis-related genes (HK, PK, PFK) and decreased gluconeogenesis markers (G6P, PC). These findings suggest that BBR improves glucose metabolism and antioxidant defenses without negatively affecting growth in crayfish fed a high-carbohydrate diet. The abstract graphic is shown in

-

Key words:

- Berberine /

- Procambarus clarkii /

- High-carbohydrate diet /

- Antioxidant capacity /

- Glucose metabolism