-

The aquatic product business has suffered severe financial losses in recent years as a result of the harsher water environment brought on by human activity and worsening weather, which has harmed fish health and even caused death[1]. Takifugu fasciatus is a kind of freshwater fish with high nutritional and economic value. The tetrodotoxin (TTX) and collagen in its skin have significant medicinal value. Since the lifting of the ban as a commercial species in 2016, its breeding scale has continued to expand[2]. However, T. fasciatus is highly dependent on natural water bodies, so it is highly susceptible to copper (Cu) pollution in the water. Especially in summer, the copper concentration in the water can often reach 100 μg/L, which poses a serious threat to its growth and survival. In addition, T. fasciatus has poor tolerance of low temperatures. When the water temperature is lower than 16 °C, the fish stops feeding, and it dies at 13 °C. When the water temperature drops below 11 °C, the fish will experience large-scale frostbite, resulting in a large number of deaths[3]. Therefore, Cu2+ exposure and low temperature, two important environmental stress factors, seriously restrict the sustainable development of the T. fasciatus breeding industry.

Autophagy is a highly conserved intracellular degradation pathway activated by cells under stress conditions. It selectively encapsulates misfolded proteins, damaged organelles and other substrates through autophagosomes and finally fuses with lysosomes to form autophagic lysosomes to achieve the degradation and recycling of contents, which plays a key role in maintaining intracellular environmental homeostasis and cell survival[4,5]. Mitochondrial autophagy is a highly specialized form of autophagy, which is specifically used to remove damaged or dysfunctional mitochondria. In this context, lc3, beclin-1 and p62 are three key genes that mark the operation of mitochondrial autophagy. Among these, lc3 is the most important marker of autophagosomes and has two autophagosomal membrane types, lc3-I and lc3-II. After induction of autophagy, proteins and cellular components undergo degradation within the lysosomes[6], and the protein lc3 associates with phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), a critical step for autophagosomes' elongation and formation[7]. Interestingly, lc3-II is changed from lc3-I upon autophagy activation by rapamycin therapy or starvation[8−10] and the rate at which lc3-I converts to lc3-II serves as a marker of autophagic flux. Autophagic flux refers to the dynamic efficiency of autophagy activity in cells from the beginning to the end of the degradation process, which is used to measure the overall functional status of the autophagy system. In addition, p62 is a multifunctional bridging protein, and its expression level and degradation dynamics directly reflect autophagy flux. During the formation of autophagosomes, p62 connects lc3 and polyubiquitinated proteins, and is selectively wrapped in the autophagosomes. The activity of autophagic flux can be evaluated by the expression of p62, as the protein expression is adversely connected with autophagic activity, resulting in accumulation and the development of illness, primarily in the gonads[11], intestine[12] and liver[13]. The degradation of p62 indicates that the autophagy flux has been completed. Lastly, beclin-1, which is expressed in a variety of human and mouse tissues and is primarily found in the cytoplasm, is essential to regulate cellular autophagy. The function of beclin-1 in fish has been better understood as a result of its protective role against oxidative stress responses and viral pathogenicity in Epinephelus akaara[14].

At present, most of the existing research focuses on virus immunity in fish, and there are relatively few studies on environmental stress in T. fasciatus. To determine the effects of environmental stressors like Cu2+ and low temperature on mitochondrial autophagy in T. fasciatus, as well as the gene characteristics and homology with other species, the mitochondrial autophagy genes lc3, beclin-1, and p62 were cloned from T. fasciatus. The findings offer some theoretical basis for investigating the molecular mechanism of mitochondrial autophagy in T. fasciatus in response to various conditions, which will help to combine the research results with broader molecular pathways in subsequent studies, such as mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) or oxidative stress signals, and improve basic theoretical research.

-

Jiangsu Zhongyang Group Co. provided the healthy juvenile T. fasciatus specimens used in this study. For 3 weeks, all of the juveniles were housed in a laboratory aquarium and fed commercial fish feed twice daily, with 24-h food suspension before the treatment, which included 43% protein and 8.0% fat (w/w). Each aquarium's juvenile T. fasciatus were fed under the following conditions: photoperiod, 12 h/d; water temperature, 25 ± 0.5 °C; dissolved oxygen content, > 7 mg/L; pH, 7.1 ± 0.2; salinity, 0.2 ± 0.1 ppt. The water's temperature, dissolved oxygen content and pH level were measured using the Taiwan AZ Instrumentation Co. 8631 AZ IP67 composite water meter. The salinity was measured using the Taiwan AZ Instrumentation Co.'s AZ 8372 salinity meter.

Methodology of the experiment and sample collection

-

Cold stress treatment: 270 fish, weighing an average of 25 g (± 1.85 g) and with an average body length of 13 cm (± 1.55 cm), were temporarily kept for 14 d. After being fed twice a day, they were divided equally among nine aquariums (30 fish per tank, 80 L,) with heating and refrigeration features. Feeding was stopped 24 h prior to sampling. Three replicates were set up for each treatment group. The experiments were set up with different temperature gradients [25 (control), 19 and 13 °C] and sampling time gradients (0, 6, 24 and 96 h). Specific cooling methods were used from 25 °C at 1 °C/h to 19 °C, maintained for 12 h to prevent stress caused by rapid cooling[15,16] and then reduced to 13 °C at the same rate. Throughout the experiment, the pH was kept at 7.0 ± 0.3, the dissolved oxygen concentration was 6.0 ± 0.5 mg/L, and the photoperiod was 12 h light/12 h dark.

Cu2+ treatment: Four treatment groups with varying Cu2+ concentrations of 0 (used as a control group), 20, 100 and 200 µg/L were established, with three replicates for each treatment group, in line with the findings of previous laboratory studies[17]. In order to create a mother liquor with a concentration of 1 g Cu/L, the particular configuration approach used copper sulfate (CuSO4·5H2O, analytically pure) as the Cu source, dissolved in high-purity water. The concentration of Cu in the water was brought to the experimental setting level by adding a suitable amount of the mother liquor to the culture water. The 300 fish, each weighing 7.8 ± 0.4 g and measuring 6.7 ± 0.1 cm in length, were divided into an average of 12 tanks at random. Four groups, each with three replicates and 25 fish, were randomly selected from among the experimental fish. The experiment spanned a duration of 28 d. Each tank was changed daily with half of the pre-formulated culture water containing Cu2+. Commercial river herring feed from Jiangsu Zhongyang Group Co. was used twice daily during the experiment, and feeding was halted 24 h before sampling. The water temperature was 25 ± 0.5 °C, the pH was 7.1 ± 0.2, the dissolved oxygen content was 6.0 ± 0.5 mg/L, and the photoperiod was L12/D12.

Following the low-temperature and Cu2+ treatments, three fish were chosen at random from each treatment group and euthanized with MS-222 anesthesia. Normal saline (0.85%) was used to soak the liver and other tissues. The mixture was then precooled to 4 °C, rinsed twice to get rid of any remaining bodily fluids and blood, and then stored at –80 °C.

Molecular cloning of autophagy cDNA

-

The whole genome of T. fasciatus was obtained, then lc3, beclin-1, and p62 intermediate expressed sequence tag (EST) sequences were screened in the transcriptome cDNA library of T. fasciatus. The primers for T. fasciatus lc3, beclin-1 and p62 are listed in Table 1. Particular primers that target lc3, beclin-1 and p62 cDNA were created and used to amplify portions of these genes in T. fasciatus. Using the SMARTerTM RACE cDNA Amplification Kit (Clontech), full-length cDNA of lc3, beclin-1 and p62 was produced by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Two steps were used in the amplification process: touchdown PCR was used in the first round, and nested PCR was used in the second. For this, 1 μL of dNTP (10 mM), 5 μL of cDNA, 5 μL of the PCR buffer, 2 μL of abridged anchor primer (10 μM), 0.5 μL of Taq polymerase (5 units/μL) and 31.5 μL of ultrapure water made up the touchdown PCR reaction. The touchdown PCR procedure included a 3-min initial denaturation step at 95 °C, 35 cycles of 95 °C for half a minute, 54 °C for half a minute, 1 min at 72 °C and a 5-min extension at 72 °C to finish. A 50 μL reaction volume mixture comprising 5 μL of the diluted touchdown PCR product, 5 μL of the PCR buffer, 1 μL of universal amplification primer (UAP) or abridged universal amplification primer (AUAP) (10 μM), 0.5 μL of Taq DNA polymerase (5 units/μL) and 33.5 μL ultrapure water was then used to perform the nested PCR using the PCR product from the first round as the template. The PCR process involved 35 cycles, which included denaturation at 94 °C for half a minute, annealing at 61 or 62 °C [for rapid amplification of cDNA 3' ends (3' RACE) and rapid amplification of cDNA 5' ends (5' RACE)] for half a minute, DNA extension at 72 °C for 1 min and a final step at 72 °C for 5 min. The second round of the PCR protocol started with an initial denaturation step for 2 min at 94 °C. The sequencing was finished after the 5' and 3' RACE PCR products were subcloned using the previously described protocol.

Table 1. Primer sequences used in PCR.

Category Name Primer 5' RACE amplification M36-1 (GSP1) TCTCCGCCTGTTTACT M36-2 (GSP2) GCGGTCGAGGACATTAAAG M36-3 (GSP3) GCACCGCTGACACACGAA M37-1 (GSP1) CATGTTTACGTGGTCC M37-2 (GSP2) TCTCTCCTTTATACCGCTCG M37-3 (GSP3) ACGGGTATCTTGTTGGGG B962-1 (GSP1) GCAGAGGTACTCAAAG B962-2 (GSP2) CGTCCTGGTCCACCGCAAAC B962-3 (GSP3) TTGACCACCTCGTCCTTC 3' RACE amplification Y14-1 (GSP1) AGGAGGCTTGAGGTTCTTCTGGGACA Y14-3 (GSP2) AACTCGGAGGAGCAGTGGACCAAAGC Y15-1 (GSP1) TCAGAAAAGACCTTCAAACAAAGACGGAGC Y15-3 (GSP2) TTCCCATGCTGGACAAGACCAAGTTC C590-1 (GSP1) CTGCCTTCAGGTGGACAGCAACAT C590-2 (GSP2) AGTAGAGTCTTTGGCTCAGATGCT Bioinformatic analysis of autophagy genes in T. fasciatus

-

The core sequence of the autophagy cDNA was obtained by splicing the full-length cDNA sequence of the sequenced autophagy gene using DNAMAN software, and BLASTX was used for homology analysis. Then ORF Finder was used to infer the amino acid sequence of the autophagy gene. To estimate the molecular mass and theoretical isoelectric point (pI) of the collagen protein, the Compute pI/Mw tool was used. ClustalX2 was used to align the autophagy amino acid sequences, and the alignment outcomes were contrasted with those of other species found in the GenBank database. A phylogenetic tree was subsequently generated by applying the neighbor-joining method in MEGA 4.0 software, then chromosome location, further gene structure analyses and in silico predictions were conducted. The sequences of mitochondrial autophagy genes were searched with BLASTP to determine their positions in the animal group database. The genomic database of our laboratory was used to determine the specific chromosomal location of mitochondrial autophagy genes. The molecular weight, theoretical isoelectric point and grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY) for each autophagy protein were assessed using the ProtParam tool available on the ExPASy server. The Euk-mPLoc 2.0 algorithm was used to estimate the autophagy genes' subcellular location.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR analysis

-

Trizol (Leagene Biotechnology, Beijing) was used to extract total RNA from tissues in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The SuperMix (Yeasen, Shanghai) was used to reverse transcribe 500 ng of RNA from each tissue into cDNA for quantitative PCR (qPCR). The resulting cDNA was then kept at −80 °C for real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). The qRT-PCR conditions were as follows: an initial denaturation step at 94 °C for half a minute, then 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 10 s and annealing at 60 °C for half a minute, and a final dissociation step at 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for a minute and lastly for 2 min at 94 °C. Three repetitions of each experiment were conducted, using β-actin as the housekeeping gene control. qRT-PCR was performed using the primers and the product sizes listed in Table 2, and the 2−ΔΔCᴛ calculation method was utilized to ascertain the relative expression levels of each gene.

Table 2. Primer sequences used in qRT-PCR.

Gene Forward (5'–3') Reverse (3'–5') Product size lc3 AGCGAACTCATCAAGATCATCAGGAG ATCCCGCTCTTGCTCGTAGACC 132 beclin-1 CAGAGAACGAATGCCAGAATTACAAGC CCTCCACCGTCTCCAGTTCCTC 144 p62 ACAGATGAAGGCGGTTGGTTGAC GTTAGGTTGTCTGGCGTACTGGATG 96 β-actin AAGCGTGCGTGACATCAA TGGGCTAACGGAACCTCT 155 Immunoblotting

-

A commercial extraction kit was used to treat tissue samples in order to isolate proteins. After protein extraction, 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was used to separate the proteins, and they were blotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore, Germany) for further examination. The membrane was treated with a blocking solution comprising 5% skim milk powder in Tris-buffered saline plus Tween 20 (TBST) for 2 h at 26 °C in order to prevent nonspecific binding. Primary antibodies were applied for 12 h at 4 °C; these included rabbit polyclonal antibodies against mouse β-actin, lc3, p62 and beclin-1 (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai). The membrane was incubated with either goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (TransGen, Beijing) or goat anti-rabbit IgG (TransGen, Beijing) following three rounds of washing. Reagents (Vazyme, Nanjing) were used for chemiluminescent detection, and ImageJ software was used to assess the signal intensities.

Statistical methods and data analysis

-

Tukey's post-hoc test was used to compare the means of each group after one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to ascertain the overall differences between groups in the experimental data. The results are provided as the means ± standard error of the mean (SE) based on triplicate studies (n = 3), with a significance level of p < 0.05 being deemed statistically significant. Version 22.0 of SPSS software was used to process the data.

-

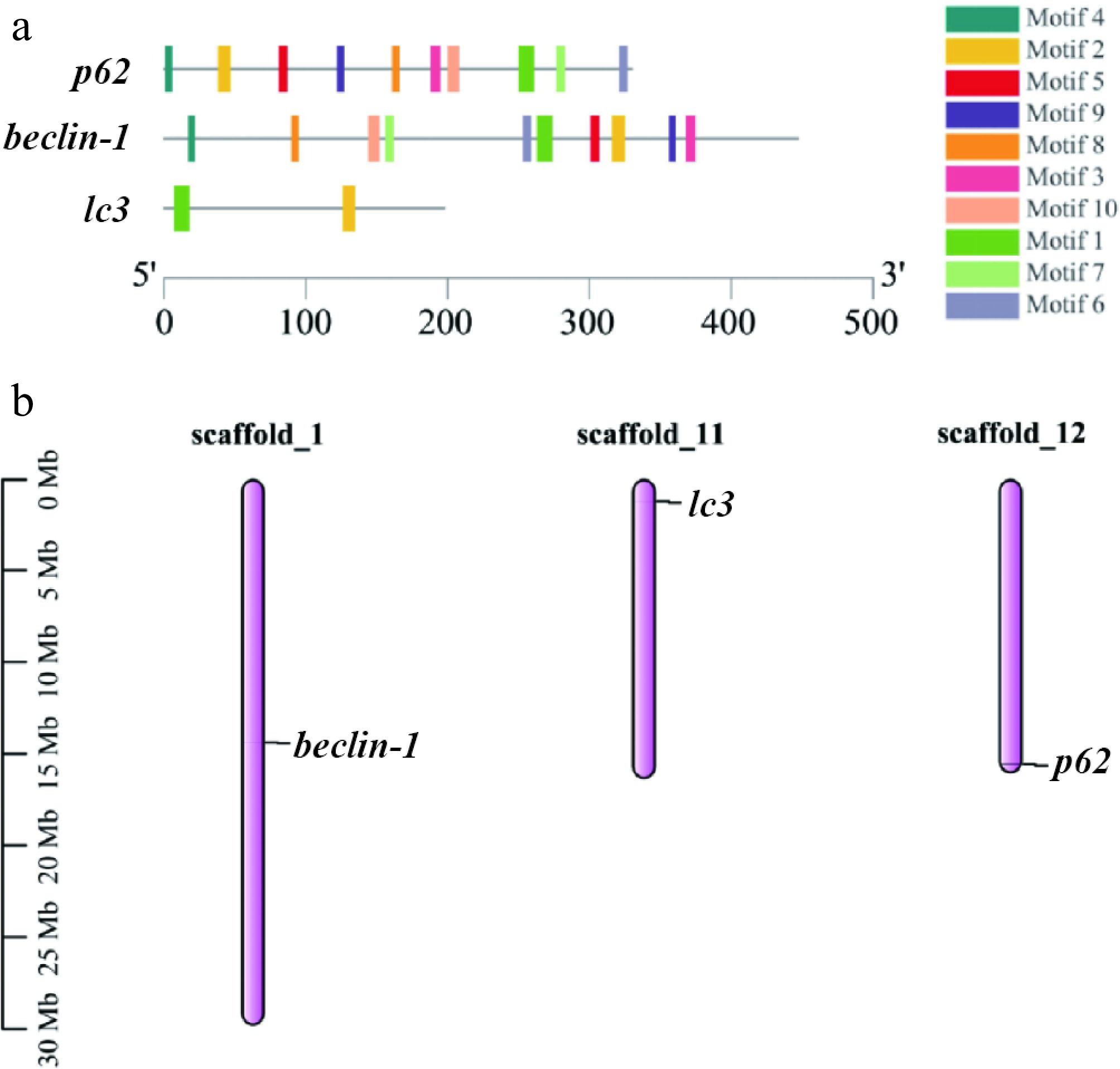

The relative molecular weights of lc3, beclin-1, and p62 were 14.72, 51.23 and 45.49 kDa, respectively. Their sizes ranged from 125 to 447 amino acids (aa), and PI ranged from pH 4.57 to 8.96. The subcellular localization prediction of the three autophagy factors indicated that they are localized in the cytoplasm. Figure 1a illustrates the 10 conserved motifs that are common across autophagy proteins. Among these, lc3 contains Motifs 1 and 2, whereas beclin-1 and p62 contain the most motifs. As shown in Fig. 1b, beclin-1 exists on chromosome 1, lc3 is on chromosome 11 and p62 is on chromosome 12. Their irregular distribution indicates that they play a role in the genome. The positions of three autophagy genes on T. fasciatus were estimated, and the three genes were located at different positions on different chromosomes.

Figure 1.

Three autophagy genes are compared on the basis of their basic characteristics. (a) Conserved motifs in the three autophagy proteins, with the black line indicating nonconserved regions, and motif lengths proportionally represented. (b) The gene positions on the graph represent the average of their endpoints, with chromosome numbers above the bars and scale in megabases (Mb) on the left.

Sequence analysis and phylogenetic comparison of lc3, beclin-1, and p62

-

The amino acid sequences of lc3, beclin-1, and p62 (Supplementary Figs S1−S3) were obtained in this study. This study also aligned the lc3, beclin-1 and p62 sequences of other species with the amino acid sequences of T. fasciatus. The similarity between the lc3 sequence of T. fasciatus and the sequence of Takifugu rubripes was 99% at the highest (Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Fig. S4). Moreover, the sequences exhibited 60%–95% homology with those of mammals and amphibians. The sequence of beclin-1 of T. fasciatus showed the highest similarity with the sequence of Takifugu rubripes, reaching 100% (Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Fig. S5). In addition, there was 80%–95% homology with mammalian and amphibian sequences. The sequence of p62 of T. fasciatus had the highest similarity with the sequence of Takifugu rubripes, reaching 99% (Supplementary Table S3 and Supplementary Fig. S6). In addition, the sequences shared 38%–45% homology with mammalian and amphibian sequences.

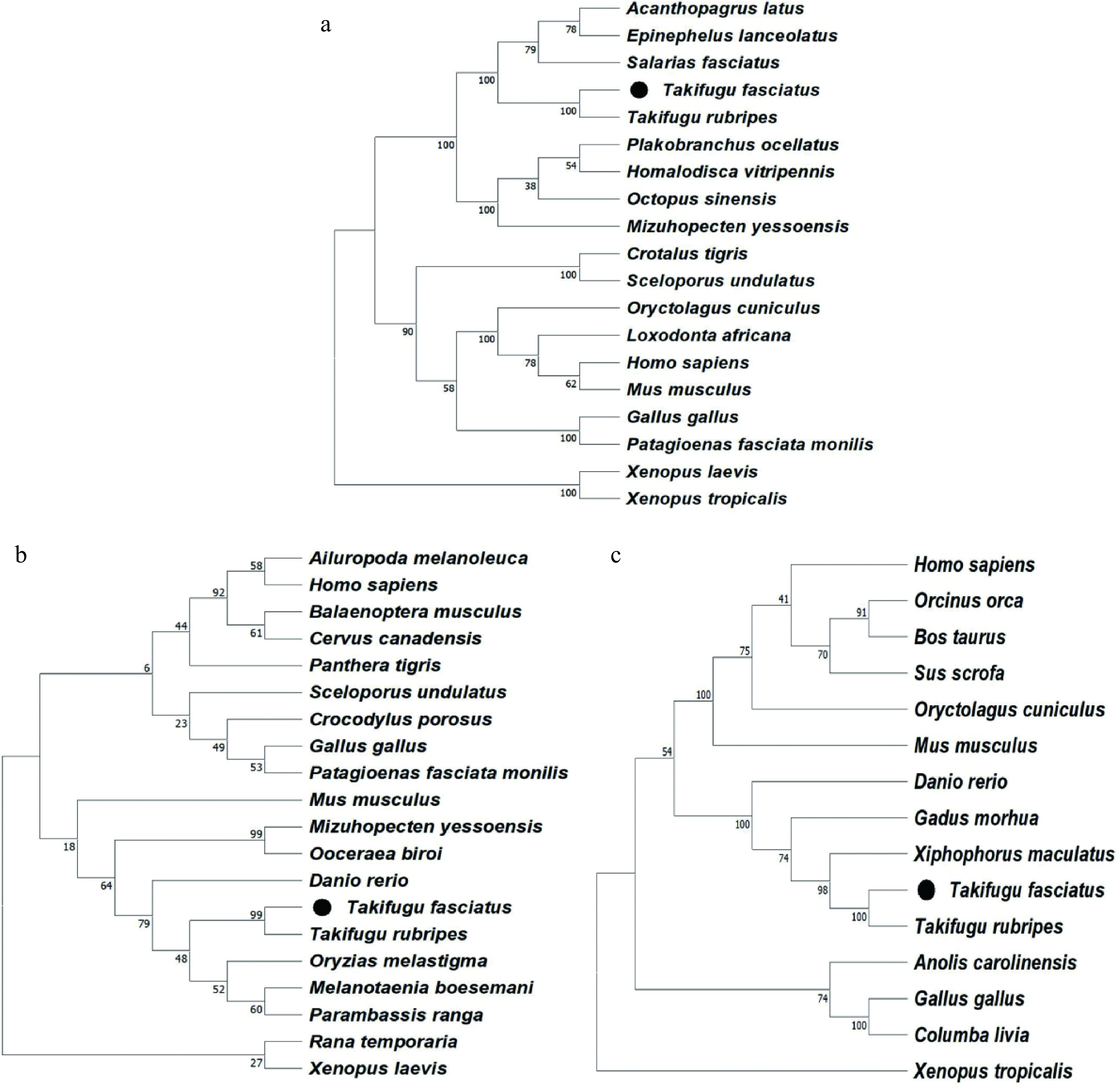

In this study, a phylogenetic analysis was conducted using MEGAX software and the neighbor-joining method. The analysis revealed that the lc3 (Fig. 2a), beclin-1 (Fig. 2b), and p62 (Fig. 2c) genes of T. fasciatus are highly conserved throughout teleosts' evolution.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of (a) lc3, (b) beclin-1, and (c) p62 from T. fasciatus and other animals.

Tissue distribution and expression patterns of autophagy-related genes in T. fasciatus

-

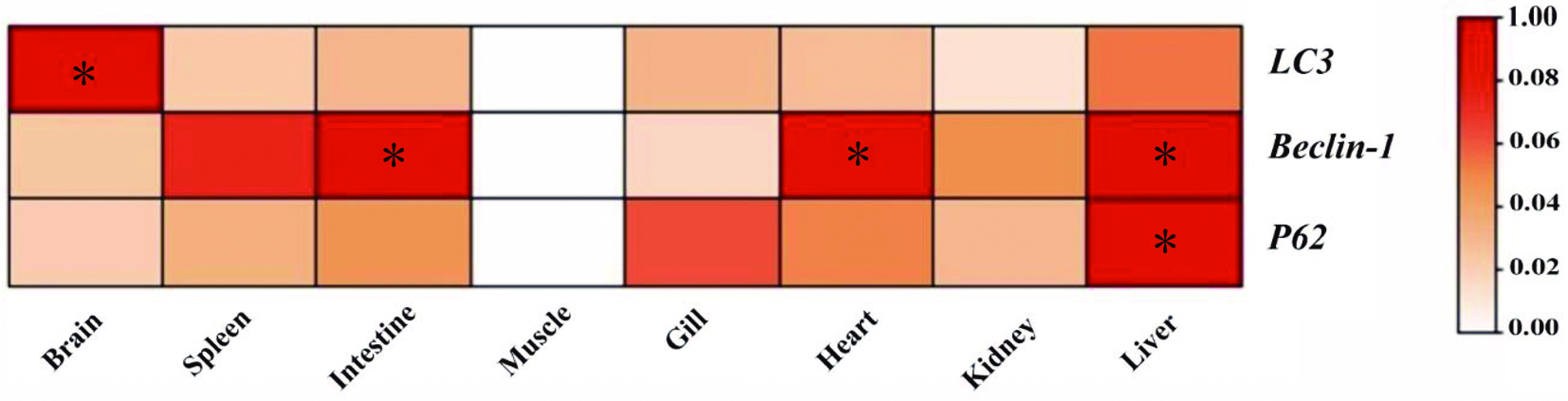

This study investigated the relative expression of autophagy genes in various tissues, including the brain, spleen, intestine, gill, muscle, heart, kidney and liver, with the tissue distribution of lc3, beclin-1, and p62 being as shown in Fig. 3. Patterns of autophagy gene expression were seen in every tissue that was examined. The brain and liver showed the highest levels of lc3 mRNA expression. The liver, heart and gut all had similar levels of beclin-1 expression, which was significantly greater than in other organs. The liver showed the highest expression of p62.

Figure 3.

Tissue-specific expression of autophagy genes in T. fasciatus. Figures marked with * represent significant differences at p < 0.05.

Expression of autophagy-related genes under various environmental stresses

-

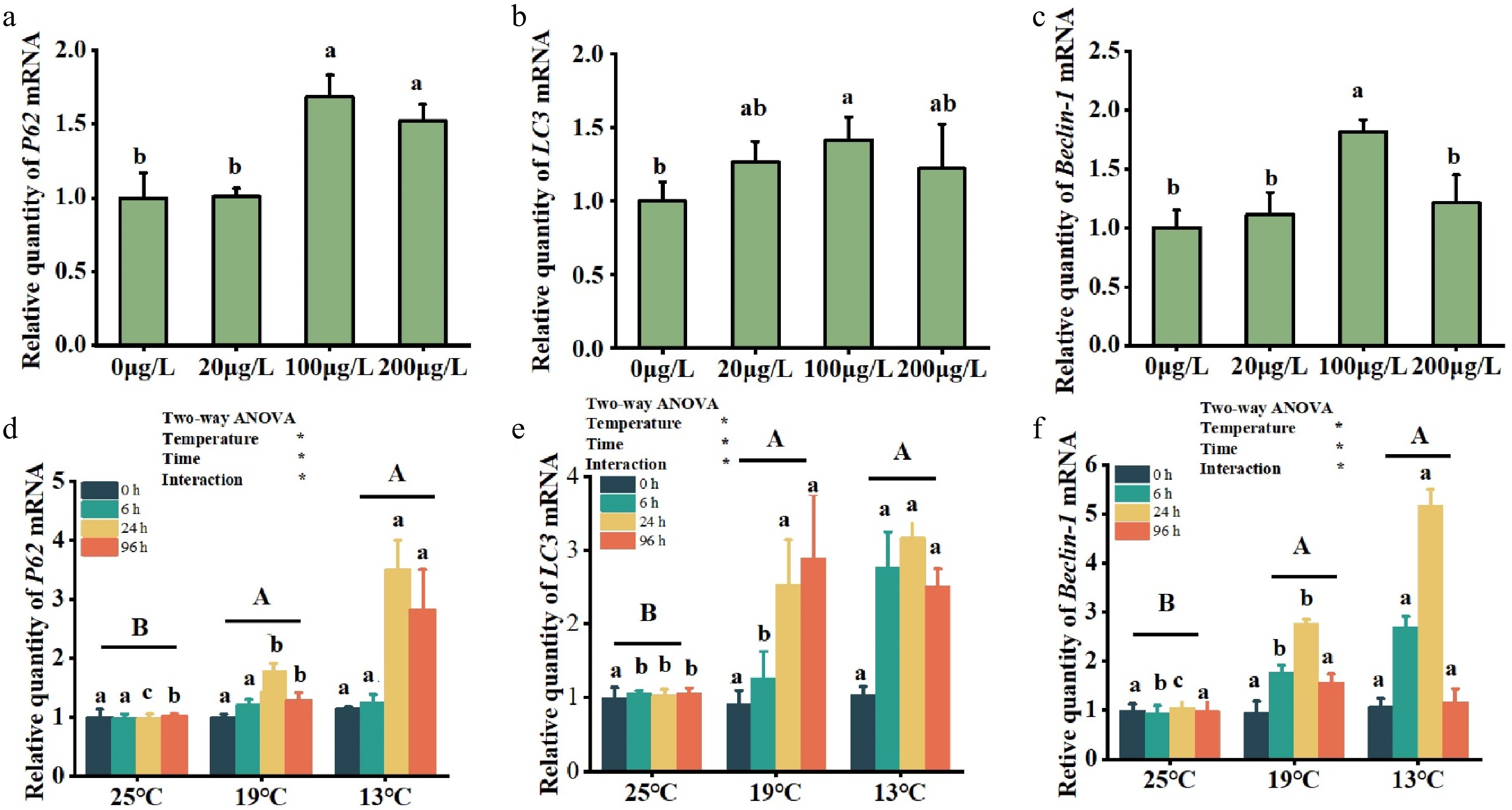

qRT-PCR was used to analyze the expression levels of lc3, beclin-1 and p62 in the liver of T. fasciatus under Cu2+ and low-temperature stress.

Under the Cu2+ treatment, no significant increase in the expression of lc3 (Fig. 4b) and beclin-1 (Fig. 4c) was observed in the 20 and 200 μg/L treatment groups, while a notable upregulation (p < 0.05) was detected in the 100 μg/L treatment group compared with the control. In contrast, p62 expression (Fig. 4a) showed no significant change at 20 μg/L, but significantly increased (p < 0.05) in both the 100 and 200 μg/L groups compared with the control.

Figure 4.

Effect of different environmental factors on autophagy gene mRNA levels under Cu2+ treatment (a, b, c) and low temperatures (d, e, f). The means ± standard error of the mean (SEM) (n = 3) are used to express the data. Significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments within the same timeframe are denoted by different lowercase letters.

Under the low-temperature treatment, at 25 °C, there was considerable upregulation of the expression levels of p62 (Fig. 4a), lc3 (Fig. 4b) and beclin-1 (Fig. 4c) in comparison with the control. In the 19 °C treatment group, lc3 expression showed a consistent increase over time, with a significant rise at 24 h (p < 0.05), reaching its peak at 96 h. In the 13 °C treatment group, lc3 expression initially increased, peaked at 24 h and then declined. In both the 19 and 13 °C treatment groups, the expression levels of beclin-1 and p62 initially increased, peaked at 24 h and then decreased.

Protein immunoassay to verify the expression of autophagy-related genes

-

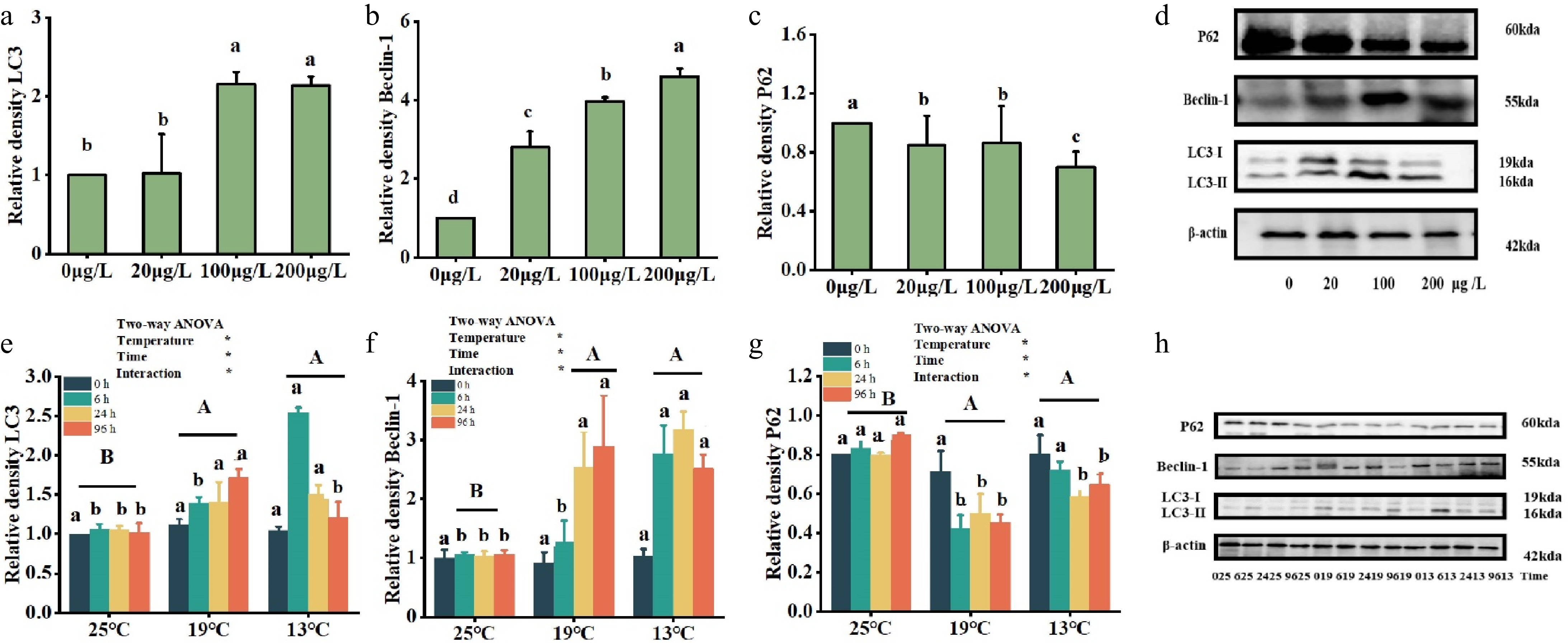

Under the Cu2+ treatment, the expression of lc3 protein (Fig. 5a) remained unchanged in the 20 μg/L treatment group relative to the control group (0 μg/L), whereas it notably increased in the 100 and 200 μg/L treatment groups (p < 0.05); the expression of beclin-1 protein (Fig. 5b) showed a significant increase in the 20, 100 and 200 μg/L treatment groups relative to the control group (0 μg/L) (p < 0.05), with the highest levels observed in the 200 μg/L treatment group. Lastly, p62 protein expression (Fig. 5c) notably decreased (p < 0.05) in the 20, 100 and 200 μg/L treatment groups relative to the control group, with the lowest expression observed in the 200 µg/L treatment group. Figure 5d shows the expression levels of lc3 (Fig. 5a), beclin-1 (Fig. 5b) and p62 (Fig. 5c) proteins in T. fasciatus treated with varying concentrations of 0, 20, 100 and 200 µg/L.

Figure 5.

Effects of multiple environmental factors on protein levels of autophagy genes udner Cu2+ treatment (a, b, c) and low-temperature treatment (e, f, g). Data are expressed as the means ± standard error of the mean (SEM) (n = 3). Significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments within the same timeframe are denoted by different lowercase letters. (d, h) The abscissa is the temperature variables of 25 °C, 19 °C and 13 °C, with 25 °C as the control group, where each temperature is divided into four timeframes (0, 6, 24 and 96 h). Significant differences in the impact of various temperatures over the same time period are indicated by distinct lowercase letters (p < 0.05). Different capital letters represent significant variations in the effects of different temperature treatments (p < 0.05), while identical letters denote no significant difference.

Under the low-temperature treatment, in the 19 °C treatment group, both lc3 (Fig. 5e) and beclin-1 (Fig. 5f) had the highest protein expression at 96 h. In the treatment group (13 °C), the peak protein expression of lc3 occurred at 6 h, while beclin-1 showed its highest expression at 24 h. Moreover, p62 protein expression (Fig. 5g) was lowest in the 13 °C treatment group at 24 h, while it was at a minimum in the 19 °C treatment group after 6 h. The expression levels of lc3 (Fig. 5a), beclin-1 (Fig. 5b) and p62 (Fig. 5c) in T. fasciatus treated with various concentrations of 0, 20, 100 and 200 µg/L are shown in Fig. 5h.

-

Autophagy is a vital cellular mechanism in eukaryotic cells that involves the degradation of cytoplasmic proteins and damaged organelles through lysosomal activity, with its regulation controlled by specific autophagy-related genes. Although it has been cloned from Barchydanio rerio[18], Pelteobagrus fulvidraco[19] and blunt snout bream[20], identification, analysis and characterization of autophagy in T. fasciatus have not been carried out. In this study, the molecular characteristics of the autophagy genes of T. fasciatus were successfully cloned and studied. In general, the homology with other animals is 38% to 99%, indicating that autophagy proteins are highly conserved in eukaryotes. Phylogenetic analysis showed that lc3, beclin-1 and p62 were closely related to the evolution of T. fasciatus and clustered with other fishes, indicating a large distance between them and amphibians and mammals.

In terms of the genes' structural composition, lc3 contains Exons 1–4 and Introns 1–3, beclin-1 contains Exons 1–10 and Introns 1–10, and p62 contains Exons 1–7 and Introns 1–6. Exon/intron structures often play a role in gene evolution and can lead to different gene functions[21]. Among the three autophagy genes, beclin-1 and p62 had more introns than lc3. The number of introns in beclin-1, as a regulator, indicates a higher degree of regulatory complexity, while the number of exons indicates a more diverse degree of conservation and function. The subcellular distribution of proteins is closely related to their function. The comparison of three autophagy genes in different species is shown in Table 3. The research shows that autophagy genes are primarily found in the cytoplasm. Therefore, more research is required to determine how different autophagy genes work.

Table 3. Comparative analysis of lc3, beclin-1 and p62 in different fish species.

Features lc3 beclin-1 p62 Sequence similarity (fish–mammal) > 85% > 80% > 75% Chromosome location (Danio rerio) Chr5 Chr5 Chr11 Chromosome location (Oryzias latipes) Chr16 Chr18 Chr14 Chromosome location (Oreochromis) Chr7 Chr5 Chr9 Major subcellular localization Autophagosome membrane Endoplasmic reticulum–mitochondria contact sites Protein aggregates Localization-related function Autophagosome formation Autophagy initiation Selective autophagy Organizational distribution

-

qRT-PCR was employed to analyze the expression levels of lc3, beclin-1 and p62 across eight different tissues of T. fasciatus. The results indicated that the three autophagy genes of T. fasciatus were consistently expressed in these eight tissues, and the three genes had different tissue expression patterns. This suggests that autophagy is present in different tissues[22]. The results indicated that lc3 was highly expressed in the brain, which may be due to the fact that in neuronal cells, exogenous mitochondrial cardiolipin can bind to lc3 and induce autophagy[23]. Hematopoietic organs (spleen and kidney) had low expression and presumably play an important role with respect to erythrocytes and the immune system[24]. The beclin-1 gene is highly expressed in the intestine. As the main digestive and important immune organ of fish, the intestine is the tissue in fish that has direct contact with farmed and natural water bodies and is highly susceptible to harmful substances in the external environment and accumulates toxic substances. Autophagy removes cytoplasmic material to generate energy and regulate intestinal homeostasis, and intestinal autophagy prevents apoptosis[25]. The elevated p62 expression in the liver aligns with the findings of increased lc3 mRNA expression in mouse livers[26], probably because the liver is considered to be an important metabolic organ[27], intimately associated with anabolic processes (such as the synthesis and storage of fatty acids, glucose) and catabolic processes (including the oxidation of glucose and fatty acids)[28].

Furthermore, the expression levels of all three autophagy genes in the liver were notably high, aligning with the findings from Zhang et al's[29] study, speculating that the liver performs essential functions that are crucial for maintaining homeostasis in the organism. A vital metabolic organ, the liver is engaged in many different processes, including detoxification, gluconeogenesis and the synthesis of plasma proteins. The active expression of lc3, beclin-1 and p62 in this tissue is probably a result of these essential processes. In this experiment, it is speculated that the liver of T. fasciatus is the main organ of mitochondrial autophagy and plays a key regulatory role, and it is possible to focus on the liver for in-depth mitochondrial autophagy research in future experiments.

Response patterns of autophagy under different environmental stress

-

Changes in some important factors in the aquatic environment often affect the normal growth and development of fish. This study explored how Cu2+ and low temperature affected the autophagy genes' mRNA and protein levels in the liver in T. fasciatus. The mRNA expression of lc3, beclin-1 and p62 in the liver of T. fasciatus was increased by both Cu2+ and low- temperature stress; the increase in p62 at the mRNA level may be regulated by oxidative stress pathways[22]. In mice, oxidative stress activates the Nrf2 pathway, which directly enhances p62 mRNA expression[30]. At the protein level, upregulation of lc3-I/lc3-II and beclin-1 expression was detected, while p62 showed a decreasing trend. This may be due to the degradation of p62 through the autophagy pathway under stress conditions, resulting in a decrease in protein[22]. Additionally, the results indicated that the abovementioned environment stress treatments increased the expression of the beclin-1 protein, which consequently promoted the formation of the mitochondrial autophagic membrane, the conversion of lc3-I to lc3-II protein, and the degradation of p62 protein. This suggests that various environmental factors may trigger the mitochondrial autophagic response in the liver of T. fasciatus.

This study represents the first investigation into the impact of Cu2+ on the mRNA and protein expression of mitochondrial autophagy genes in the liver of T. fasciatus. The results demonstrated a significant upregulation in the mRNA levels of three mitochondrial autophagy genes in the 100 μg/L treatment group. Elevated activity of glutathione transferase (GT) and expression of beclin-1 and lc3 in mice exposed to Fe3+ and Cu2+ have been demonstrated[31], and these results are consistent with those observed in the current experiment. However, under heavy metal (Pb) exposure, the p-mTOR/mTOR ratio was reduced and the levels of beclin-1 protein expression, autophagy-related 12 (atg12) and autophagy-related 7 (atg7) were upregulated in mice, while the lc3-II/lc3-I ratio and p62 protein expression levels were upregulated, ultimately leading to impaired autophagic flux. This could be attributed to the varying resistance levels to different heavy metals and the distinct properties of these metals across species[32]. Therefore, we demonstrated that Cu ion exposure resulted in upregulation of beclin-1 expression, an increased lc3-I/lc3-II ratio and decreased p62 protein expression, thus indicating that hepatic autophagic degradation occurs normally in T. fasciatus.

Fish exhibit a high sensitivity to fluctuations in water temperature[33], and the expression of autophagy-related genes in fish undergoes significant changes in the face of cold stress. The current study demonstrated that exposure to low-temperature stress increased the gene expression levels of beclin-1, lc3 and p62, which is consistent with the up-regulation of mitophagy in zebrafish at low temperature[34]. Furthermore, at 13 °C, the conversion rate of lc3-II protein in T. fasciatus peaked at 6 h, whereas the highest levels of p62 protein degradation and beclin-1 expression were observed at 24 h. Therefore, we speculated that the expression of these three mitochondrial autophagy proteins is sequential. In studies on zebrafish, it was found that cyhalothrin (FEN) inhibits mTOR by activating p38 MAPK, which activates autophagy in the zebrafish liver, causing damage to the fish. Previous work in our laboratory[35] has found that MAPK (ERK, JNK and p38 MAPK), an important pathway regarding cell proliferation and differentiation in T. fasciatus under cold stress[36,37], showed an upregulation of its MAPK protein expression levels with a decrease in temperature. The findings of this study revealed that exposure to low-temperature stress led to a significant increase in the expression of lc3 and beclin-1 proteins, whereas p62 protein levels significantly decreased in the liver of T. fasciatus. It is hypothesized that the mTOR signaling pathway is a pathway of mitochondrial autophagy in response to internal and external environmental stress in T. fasciatus and is an important inhibitory regulator in the autophagy process. Low temperature inhibits mTOR through the activation of MAPK, thereby activating the mitochondrial autophagic response in the liver of T. fasciatus.

-

In conclusion, lc3, beclin-1 and p62 are key genes involved in mitochondrial autophagy. These were identified in T. fasciatus, and their responses to Cu2+ and cold stress were examined for the first time. According to the mRNA and protein expression patterns of the lc3, beclin-1 and p62 genes in T. fasciatus under Cu2+ and low-temperature stress, both environmental stresses were able to activate the mRNA and protein expression of lc3, beclin-1 and p62 genes, and the liver beclin-1 gene is more sensitive to different stresses than the lc3 and p62 genes. This study provides a theoretical basis for understanding the molecular mechanism of T. fasciatus in response to different environmental stress factors, and lays a foundation for further exploration of the relationship between autophagy genes and mTOR, MAPK and other signaling pathways. These findings are conducive to the development of molecular markers based on autophagy-related genes, which can be used for the breeding of stress-resistant varieties and provide better varieties for aquaculture.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32473131), the 'JBGS' Project of Seed Industry Revitalization in Jiangsu Province [JBGS(2021)034], Jiangsu Agriculture Science and Technology Innovation Fund [CX(22)2029], Jiangsu Province '333 High-level Talents Cultivating Project'.

-

All procedures were reviewed and preapproved by the Ethics Committee of Experimental Animals of Nanjing Normal University (Nanjing, China), identification number: IACUC-20220255, approval date: 2022-02-17. The research followed the 'Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement' principles to minimize harm to animals. This article provides details on the housing conditions, care, and pain management for the animals, ensuring that the impact on the animals is minimized during the experiment.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: data, original drafting: Tang Z; Wang H; fish sample collection: Peng C; conceptualization and review: Wang T; project administration: Yin S. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Zhongxing Tang, Haoze Wang

- Supplementary Table S1 Accession numbers of amino acid sequences of LC3.

- Supplementary Table S2 Accession numbers of amino acid sequences of Beclin-1.

- Supplementary Table S3 Accession numbers amino acid sequences of P62.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Nucleotide and amino acid sequences of LC3 of T. fasciatus.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Nucleotide and amino acid sequences of Beclin-1 of T. fasciatus.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Nucleotide and amino acid sequences of P62 of T. fasciatus.

- Supplementary Fig. S4 Multiple alignment of the LC3 amino acid sequence of T. fasciatus with other animals.

- Supplementary Fig. S5 Multiple alignment of the Beclin-1 amino acid sequence of T. fasciatus with other animals.

- Supplementary Fig. S6 Multiple alignment of the P62 amino acid sequence of T. fasciatus with other animals.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Tang Z, Wang H, Peng C, Yin S, Wang T. 2026. Molecular characterization of LC3, Beclin-1 and P62 and their response patterns under low temperature and copper ion exposure in Takifugu fasciatus. Animal Advances 3: e002 doi: 10.48130/animadv-0025-0033

Molecular characterization of LC3, Beclin-1 and P62 and their response patterns under low temperature and copper ion exposure in Takifugu fasciatus

- Received: 07 February 2025

- Revised: 18 June 2025

- Accepted: 08 July 2025

- Published online: 09 January 2026

Abstract: In recent years, excessive human activities and climate deterioration have led to changes in the aquatic environment, causing frequent diseases in Takifugu fasciatus and huge economic losses. However, it is not clear whether the liver, an important immune organ for fish, can activate autophagy in response to stress caused by environmental changes (e.g., low temperature and Cu2+). Microtubule-associated proteins light chain 3 (lc3), beclin-1 and sequestosome 1 (p62) are important markers of mitochondrial autophagy. In this study, lc3, beclin-1 and p62 were cloned and analyzed for their molecular characteristics, homology and evolutionary relationships with other species using T. fasciatus as the study target. In addition, this experiment also studied the expression and distribution of lc3, beclin-1 and p62 genes in the brain, muscle, intestine, spleen, gill, heart, kidney and liver, and the expression levels in the liver under Cu2+ and a low-temperature environment. Cu2+ and water temperature were able to activate the mRNA and protein expression of lc3, beclin-1 and p62, and beclin-1 was more sensitive than lc3 and p62 in their livers in response to Cu2+ and the low-temperature environment. This study can help to elucidate the molecular mechanism of mitochondrial autophagy genes of T. fasciatus in response to Cu2+ and low-temperature environments, and provide a theoretical basis for guiding the culture of T. fasciatus.

-

Key words:

- Liver /

- Mitochondrial autophagy /

- Low-temperature stress /

- Cu2+ /

- Takifugu fasciatus