-

Heat stress (HS) is a major environmental challenge threatening male reproductive efficiency in livestock, particularly during peak breeding seasons that coincide with high ambient temperatures. Elevated scrotal temperature impairs spermatogenesis and epididymal function, resulting in decreased sperm density and motility, increased morphological defects, and disrupted acrosomal integrity[1]. These thermal effects compromise endocrine homeostasis by disturbing the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal (HPG) axis and further disrupt spermatogenic microenvironments, ultimately lowering fertility and reproductive success[2].

At the testicular level, heat exposure alters the integrity of the blood–testis barrier (BTB), induces germ cell apoptosis, and impairs steroidogenesis by damaging Leydig cells' ultrastructure and reducing the expression of key enzymes such as Steroidogenic Acute Regulatory protein (StAR) and Cytochrome P450 family 11 subfamily A member 1 (CYP11A1)[3,4]. Sertoli cells, essential for germ cell support, are particularly sensitive to oxidative and inflammatory stress, which compromises their structural and metabolic functions[5,6]. Maintaining testicular homeostasis under thermal stress is therefore critical for sustaining reproductive performance.

Melatonin (MT), a pleiotropic molecule synthesized primarily by the pineal gland and derived from tryptophan, has gained increasing attention for its potent antioxidative, anti-apoptotic, and immunomodulatory properties[7,8]. Recent studies have confirmed that melatonin can improve male fertility under stress by enhancing antioxidant defenses[9] and regulating reproductive hormones[10]. However, whether melatonin also acts through metabolic reprogramming, particularly via amino acid pathways, to exert testicular protection under HS conditions remains largely unexplored.

Functional amino acids, especially arginine (Arg) and tryptophan (Trp), play vital roles in spermatogenesis, immune defense, and energy metabolism[11,12]. Arginine contributes to nitric oxide and polyamine biosynthesis, enhancing sperm quality and testicular perfusion[13], whereas tryptophan is a key precursor of serotonin and melatonin, influencing oxidative balance and reproductive signaling[14,15].

This study investigates whether melatonin alleviates HS-induced testicular damage by modulating amino acid metabolism. Using both dairy goats and a mouse model, we applied nontargeted metabolomics to identify the key metabolic pathways involved in reproductive adaptation to HS. Our findings provide new mechanistic insights into the interplay between melatonin and amino acid metabolism in testicular protection, offering a novel strategy for improving male fertility under HS.

-

All experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by the Animal Ethical and Welfare Committee of Northwest A&F University (Approval No. 201902A299, date: 2019-02-25), and all procedures were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines for animal care and use. A total of nine clinically healthy male Guanzhong dairy goats, aged between 1.5 and 3.5 years and weighing 65–75 kg, were enrolled in the study. These animals were obtained from Shaanxi Aonike Dairy Goat Breeding Co., Ltd. (Shaanxi, China). Animals were provided with approximately 1 kg/day of a total mixed ration, comprising 0.25 kg of roughage (alfalfa, peanut vines, corn husks) and 0.75 kg of concentrate to meet their nutritional requirements. Male Kunming mice (12 weeks old, initial body weight 36 ± 5 g) were purchased from Chengdu Dashuo Experimental Animal Co., Ltd. and housed under controlled environmental conditions (22 ± 2 °C, 12-h light–dark cycle) with ad libitum access to food and water. The mice were fed a commercial standard rodent diet obtained from Chengdu Dashuo Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd.

Dairy goat experiment

-

Throughout the trial, goats in the HS and HS+MT groups were exposed to natural sunlight outdoors from 12:00 to 16:00 daily, with unrestricted access to food and water. Ambient temperature and relative humidity were recorded daily, and the temperature–humidity index (THI) was calculated using the formula: THI = (0.8 × Ambient temperature) + ([Relative humidity %/100] × [Ambient temperature − 14.4]) + 46.4. A continuous 14-day period with THI values ranging between 73 and 80 was selected as the modeling phase of HS. The HS+MT group was pretreated by subcutaneous implantation of slow-release melatonin (Regulin®, Ceva) implants behind the ear 15 days before HS exposure at a dosage of 1 mg/kg body weight. Concurrently, a natural condition control group (NC) was established in autumn, following identical experimental protocols except without heat exposure.

Mouse experiment

-

To investigate the protective effects of melatonin and the involvement of arginine and tryptophan metabolism under heat stress, 30 male mice were randomly assigned to five groups: NC, HS, HS+MT, HS+Arg, and HS+Trp. Mice in the NC and HS groups received daily intraperitoneal injections of 0.2 mL saline, whereas the HS+MT group received melatonin (2 mg/kg in 0.2 mL saline). The HS+Arg and HS+Trp groups were administered intraperitoneal injections of arginine (20 mg/kg)[16] and tryptophan (20 mg/kg)[17], respectively, in 0.2-mL volumes. Except for the NC group, all mice were subjected to heat stress by being housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled chamber (38 ± 0.5 °C, 65% ± 5% relative humidity) for 12 h/day (08:00–20:00) over 7 consecutive days. Following treatment, testis and epididymis tissues were collected, and sperm were retrieved from the epididymal tail.

Semen collection and quality testing

-

Semen samples from dairy goats were collected using a false vagina with does in estrus as sexual stimuli. Ejaculate volume and color were assessed visually, and the samples were immediately processed. Sperm quality parameters, including the sperm's density, motility, and viability, were evaluated using a fully automated computer-assisted sperm analysis (CASA) system (Meilang, Nanjing Songjing Tianlun Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). Semen smears were prepared and stained with crystal violet to assess the sperm's morphology and abnormality rates.

Serum collection

-

Blood samples were collected via jugular venipuncture from dairy goats and via orbital sinus puncture from mice. Samples were left to clot at room temperature for 30 minutes and centrifuged at 1,200 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. Serum was aliquoted and initially stored in liquid nitrogen, followed by transfer to a −80 °C freezer for long-term storage.

Collection of testes and epididymides

-

Testes and epididymides from mice were dissected into appropriate sections. Samples were either fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (BL539A, Biosharp) for histological analysis or snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for subsequent assays.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

-

Serum concentrations of interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, nitrous oxide (NO), tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, MT, testosterone (T), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), Arg, and Trp were measured using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits for goats and mice (Shanghai Kexing Trading Co., Ltd.).

Oxidative stress indices

-

Serum concentrations of reactive oxygen species (ROS), superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione (GSH), and total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC) were measured using commercially available colorimetric assay kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China), following the manufacturer's instructions. Blood samples were collected from the jugular vein and centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C to separate the serum. Absorbance was measured using a microplate reader (BioTek Epoch, USA), and data were calculated according to the standard curves provided in each kit. All measurements were performed in triplicate.

Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry analysis

-

Serum metabolites were extracted using a methanol: acetonitrile: water solution (2:2:1, v/v/v), vortexed, and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was subjected to liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis using a Q Exactive Plus mass spectrometer coupled with an ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Data were acquired in both positive and negative ion modes. Raw mass spectrometry data were processed using MS-DIAL (v4.70) for peak alignment and feature extraction. Metabolites were identified on the basis of accurate molecular mass (mass error < 10 ppm) and tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) spectral matching (mass deviation < 0.02 Da), with only features detected in ≥ 50% of the samples being retained for further analysis.

Data were normalized in R (v4.2.2), and statistical models including partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) were constructed to explore the metabolic differences among the groups. The model's robustness was assessed using 200 random permutations. Differential metabolites were selected based on a variable imporance in projection (VIP) > 1.0 (PLS-DA) and p < 0.05 (t-test or analysis of variance [ANOVA]). Kyoto Enclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment was conducted using Fisher's exact test with false discovery rate (FDR) correction (adjusted p < 0.05).

Histological analysis (hematoxylin and eosin staining)

-

Testicular and epididymal tissues fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde were processed through graded ethanol dehydration, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned into 2-μm slices. For histological assessment, tissue sections were further fixed in Bouin's solution and subjected to hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining following the standard protocols.

Immunohistochemical and immunofluorescence staining

-

Paraffin-embedded sections were deparaffinized in xylene (twice for 10 min each), rehydrated with descending concentrations of ethanol, and subjected to antigen retrieval using a citrate buffer (pH 6.0) with microwave heating. After blocking with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at room temperature for 1 h, the sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies. For immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis, the primary antibodies used included occludin (Abcam, ab216327), ZO-1 (Abcam, ab221547), IL-1β (Wanlei Bio, WL02257), and TNF-R2 (Wanlei Bio, WL02956). The horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (e.g., goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin [Ig]G-HRP) were applied for 1 h at 37 °C, followed by visualization with diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogen (1–3 min) and counterstaining with hematoxylin. The sections were dehydrated and mounted with resin. For the immunofluorescence (IF) assay, occludin (Abcam, ab216327) was used as the primary antibody, and the sections were incubated with fluorophore-labeled secondary antibodies (e.g., goat anti-rabbit IgG-Alexa Fluor®594) for 4 h at 4 °C in the dark, followed by nuclear staining with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and mounting with an anti-fade medium. The IHC images were captured using a brightfield microscope, whereas the IF images were acquired using a confocal laser scanning microscope, selecting three random fields per sample.

RNA extraction and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

-

Total RNA was extracted from tissue samples (~50 to 100 mg) using TRIzol reagent (Takara, Japan), following the manufacturer's protocol. RNA quality and concentration were evaluated using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) with optical density (OD260/280) ratios between 1.8 and 2.0 considered acceptable. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using the FastKing RT Kit (Tiangen Biotech, China) with a genomic DNA removal step. Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was performed using ChamQ SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme, China) on a BIO-RAD CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System (BIO-RAD, USA; serial No. 788BR08727, Singapore). Each reaction (20 μL) was conducted in triplicate under the following thermal cycling conditions: Initial denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 30 s. Melt curve analysis was performed to verify the amplification specificity. Gene-specific primers are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCᴛ method, with GAPDH as the internal control.

Western blotting

-

Testicular tissues were homogenized in a radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (Beyotime, Beijing, China) supplemented with phosphatase inhibitors and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). After centrifugation at 13,200 × g, the supernatants were collected, mixed with a sample loading buffer (Beyotime, Beijing, China), and denatured by boiling at 100 °C for 8 min. Proteins were separated via sodium dodecyl–sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, USA). Membranes were blocked with 8% skim milk for 2 h and incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary antibodies, followed by incubation with appropriate secondary antibodies for 4 h at 4 °C. Immunoreactive bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection kit (Dining, Beijing, China) and captured using a multifunctional imaging system (SHENHUA, Hangzhou, China). β-Actin was used as the internal control. Detailed information on all reagents and kits used in this study is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Statistical analysis

-

Data are presented as the means ± standard deviation (SD) based on at least three independent experiments. Comparisons between two groups were analyzed using Student's t-test, while differences among multiple groups were assessed by one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test. Prior to performing ANOVA, the assumptions of independence, normality, and homogeneity of variance were evaluated. The independence of the observations was ensured by the experimental design. The normality of the data distribution was visually assessed using histograms and boxplots, and no significant deviations were observed. Homogeneity of variance was tested using both Brown–Forsythe and Bartlett's tests, and the results indicated no significant differences among the groups' variances (p > 0.05), confirming the suitability of ANOVA.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 26.0 (IBM, USA), and graphical representations were generated with GraphPad Prism 8.0.2 (GraphPad Software, USA). Statistical significance was considered at * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001, with "ns" indicating no significant difference.

-

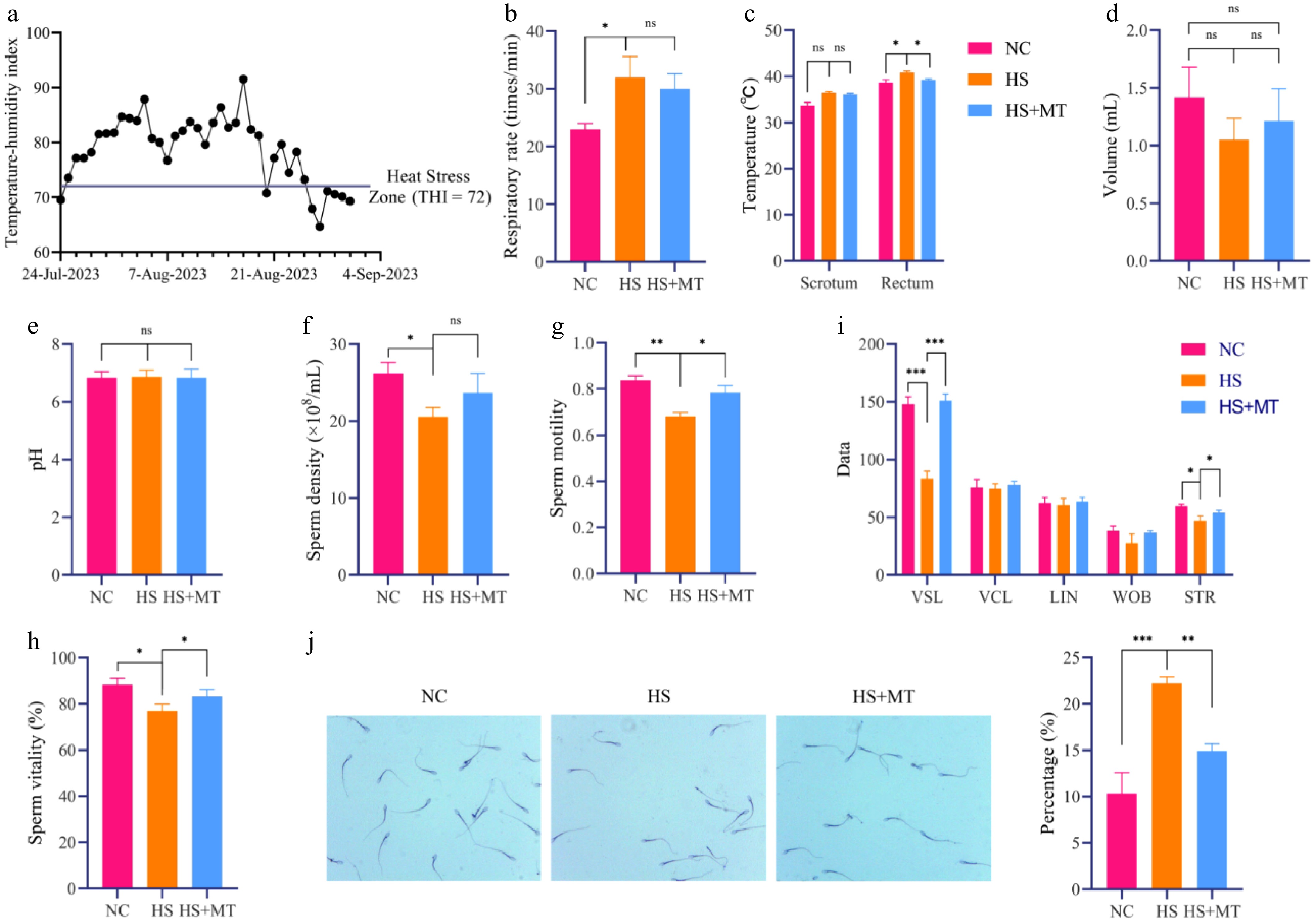

To investigate the protective effect of melatonin on the decline in male reproductive performance under high-temperature conditions in summer. Compared with the NC group, dairy goats in the HS group exhibited a significantly increased respiratory rate and rectal temperature (p < 0.05), while scrotal temperature remained unchanged among the groups. Melatonin treatment markedly reduced rectal temperature under heat stress, approaching the level of the NC group (Fig. 1b, c). Heat stress significantly decreased sperm's density, motility, and viability (p < 0.05), whereas melatonin alleviated these reductions (Fig. 1f–h). No differences in semen volume or pH were detected among the groups (Fig. 1d, e). Additionally, melatonin improved sperm's linear velocity (VSL) and straightness (STR), which were impaired by HS (p < 0.05, Fig. 1i). The sperm abnormality rate was elevated in the HS group but significantly decreased after the melatonin intervention (Fig. 1j). These findings indicate that melatonin significantly alleviates the decline in sperm quality caused by HS and has good protective potential.

Figure 1.

Protective effects of melatonin on sperm quality in heat-stressed dairy goats. (a) Daily temperature–humidity index (THI) during the experimental period. (b) Respiratory rate of dairy goats in each group. (c) Scrotal and rectal temperatures. (d) Semen volume. (e) Semen pH. (f) Sperm concentration. (g) Sperm motility. (h) Sperm viability. (i) Sperm motility parameters including straight-line velocity (VSL), curvilinear velocity (VCL), linearity (LIN), wobble (WOB), and straightness (STR). (j) Crystal violet staining and sperm abnormality rate. Statistical significance was as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001; ns, no statistical significance.

Melatonin alleviates the systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, and reproductive hormone imbalance induced by HS in dairy goats

-

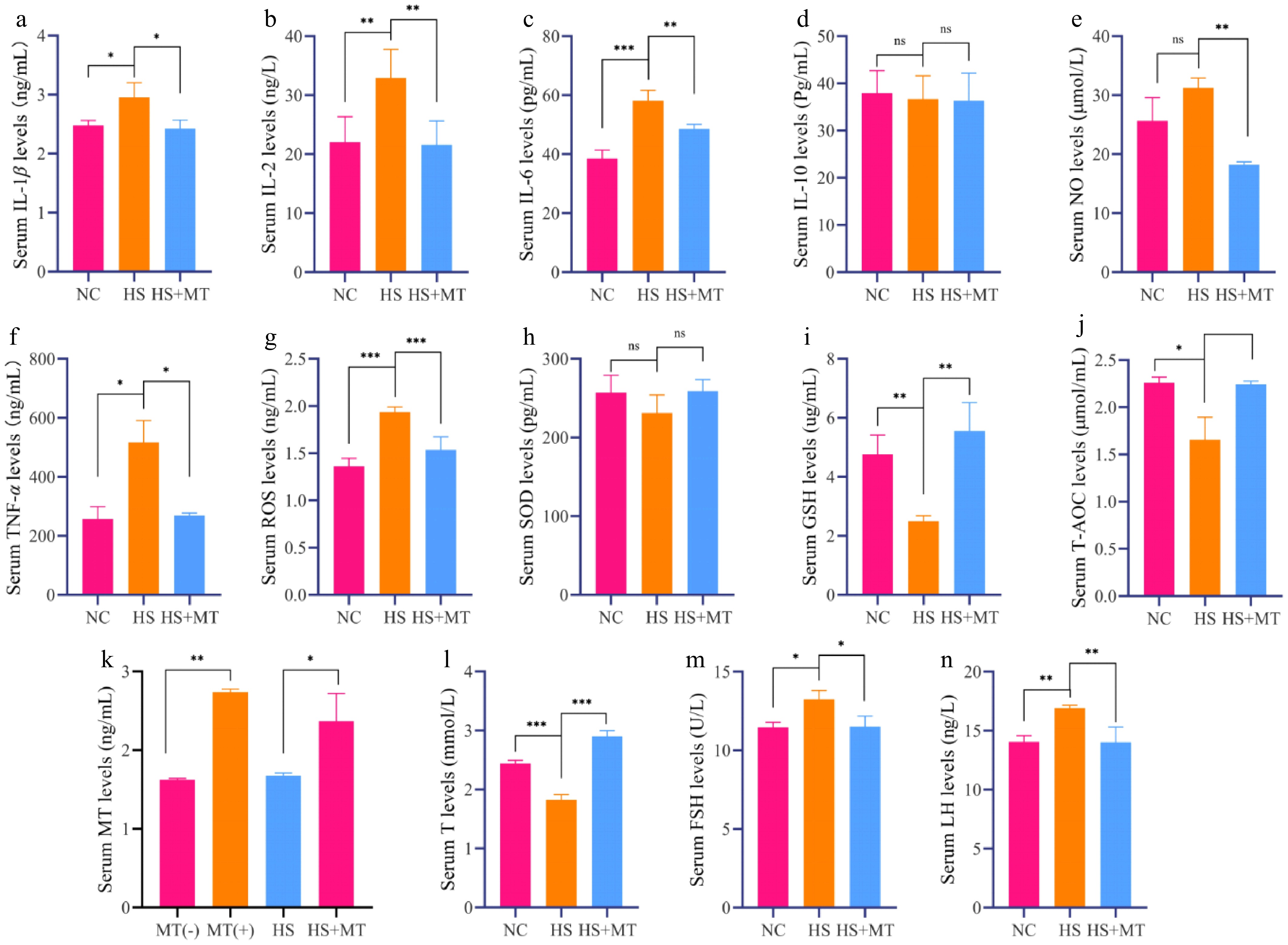

To evaluate the protective effects of melatonin against systemic inflammation and oxidative stress under HS, serum biochemical parameters were analyzed. The results of ELISA showed that the levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, and TNF-α were significantly elevated in the HS group compared with the NC group (p < 0.05), whereas melatonin supplementation markedly reduced these levels (Fig. 2a–c, f). No significant changes in IL-10 levels were observed among the groups (Fig. 2d), indicating that melatonin primarily exerted its anti-inflammatory effects by downregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines. Heat stress significantly increased serum ROS and decreased the antioxidant indicators GSH and T-AOC (p < 0.05), which were partially restored by melatonin (Fig. 2g, i, j), suggesting a protective antioxidant effect. Additionally, the serum melatonin concentration was significantly increased after treatment and remained elevated in the HS+MT group compared with the HS group after 15 days, confirming the sustained release and effectiveness of melatonin implants during HS (Fig. 2k). To explore the endocrine regulatory effects of melatonin, levels of T, FSH, and LH were measured. Heat stress induced typical hormonal disruption, characterized by a significant decrease in T and increases in FSH and LH. These alterations were reversed by the melatonin treatment, with hormone levels in the HS+MT group returning to those of the NC group (Fig. 2i–n). Collectively, these findings indicate that melatonin mitigates systemic inflammation and oxidative stress, stabilizes testosterone levels, and modulates the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis, thereby alleviating HS-induced reproductive dysfunction in dairy goats.

Figure 2.

Effect of melatonin on serum biochemical indicators and reproductive hormones in heat-stressed dairy goats (a) Serum IL-1β levels. (b) Serum IL-2 levels. (c) Serum IL-6 levels. (d) Serum IL-10 levels. (e) Serum NO levels. (f) Serum TNF-α levels. (g) Serum ROS levels. (h) Serum SOD levels. (i) Serum GSH levels. (j) Serum T-AOC levels. (k) Serum melatonin levels before and after injection of melatonin implants, as well as in the HS group and HS+MT group. (l) Serum T levels. (m) Serum FSH levels. (n) Serum LH levels. Statistical significance was as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, ns, no statistical significance.

Melatonin alleviates HS-induced systemic metabolic disruption in dairy goats

-

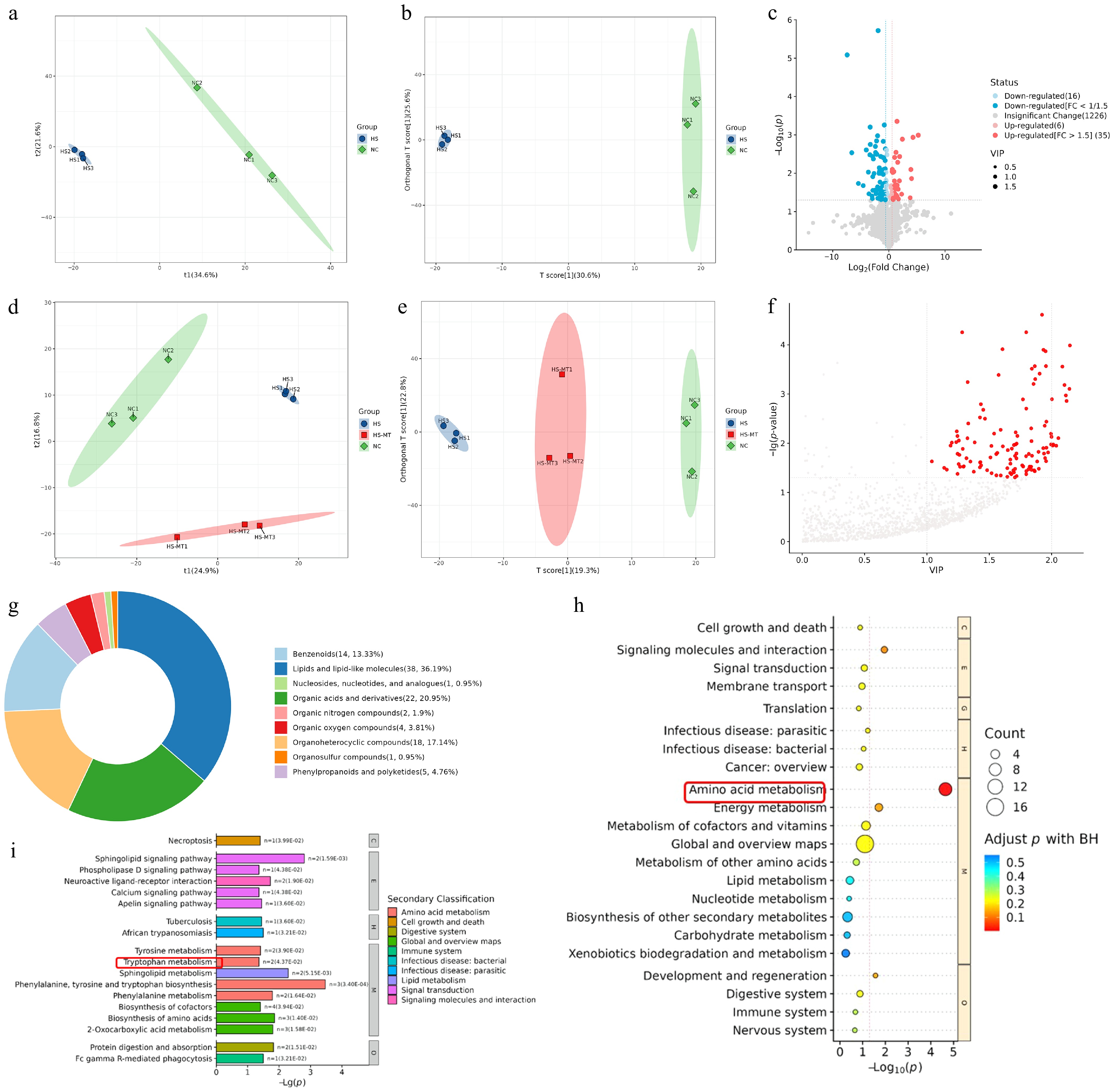

To investigate whether HS alters systemic metabolism in dairy goats, we conducted untargeted metabolomic profiling of serum samples using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS). PLS-DA and orthogonal PLS-DA (OPLS-DA) analyses showed a clear separation between the NC and HS groups, indicating that HS induced global metabolic reprogramming in serum (Fig. 3a, b). Under the criteria of VIP > 1.0, fold change (FC) ≥ 1.5 or ≤ 0.67, and p < 0.05, a total of 55 and 63 differentially expressed metabolites were identified in positive and negative ion modes, respectively. Among them, 15 and 23 metabolites were upregulated, whereas 40 were downregulated in the HS group compared with the NC group (Fig. 3c), suggesting that HS significantly disrupted metabolic homeostasis in dairy goats. To examine whether melatonin alleviates HS-induced metabolic disruption, we further analyzed serum samples from the NC, HS, and HS+MT groups using the same LC-MS-based untargeted metabolomics approach. PLS-DA and OPLS-DA revealed distinct metabolic profiles among the three groups (Fig. 3d, e). A total of 107 significantly altered metabolites were identified under the criteria of VIP > 1 and p < 0.05 (Fig. 3f). Hierarchical clustering analysis revealed four major classes of differential metabolites, including lipids and lipid-like molecules (36.19%), organic acids and derivatives (20.95%), heterocyclic compounds (17.14%), and benzenoids (13.33%) (Fig. 3g). KEGG pathway analysis indicated that these metabolites were enriched in amino acid metabolism, with tryptophan metabolism showing the most prominent differences among the groups (Fig. 3h, i). These findings suggest that melatonin ameliorates HS-induced metabolic disruption, possibly by regulating amino acid pathways, particularly tryptophan metabolism, thereby contributing to the improvement in reproductive performance in dairy goats under thermal stress.

Figure 3.

Effects of heat stress and melatonin on serum metabolomic profiles in dairy goats (a) The PLS-DA score plot of the NC group versus the HS group is used to measure the degree of differences in metabolites between and within groups. (b) The OPLS-DA score plot of the NC verus the HS group is used to measure the degree of the differences in metabolites between and within groups. (c) The volcano plot of the NC vs. HS group was generated using FC ≥ 1.5 or FC ≤ 1/1.5 and p < 0.05 as the screening criteria. Two vertical dashed lines indicate the threshold range of log2 (1/1.5) and log2 (1.5); red dots represent significantly upregulated metabolites, while blue dots indicate significantly downregulated metabolites. (d) NC: The PLS-DA score plot of the NC versus HS+MT groups is used to measure the degree of the differences in metabolites between and within groups. (e) The OPLS-DA score plot of NC vs. HS vs. HS+MT groups was used to measure the degree of differences in metabolites between and within groups. (f) The scatter plot of the NC vs. HS+MT groups uses VIP > 1 and p < 0.05 as screening criteria, with the horizontal axis representing the VIP value of OPLS-DA and the vertical axis representing the log (p-value). The red dots represent metabolites with VIP > 1 and p < 0.05. (g) The substance classification results obtained by classifying and statistically analyzing the differential metabolites of each comparative group on the basis of their structure and function. (h) KEGG Level 1 pathways. (i) KEGG Level 2 pathways.

Melatonin alleviates HS-induced metabolic disruption by modulating amino acid metabolism in dairy goats

-

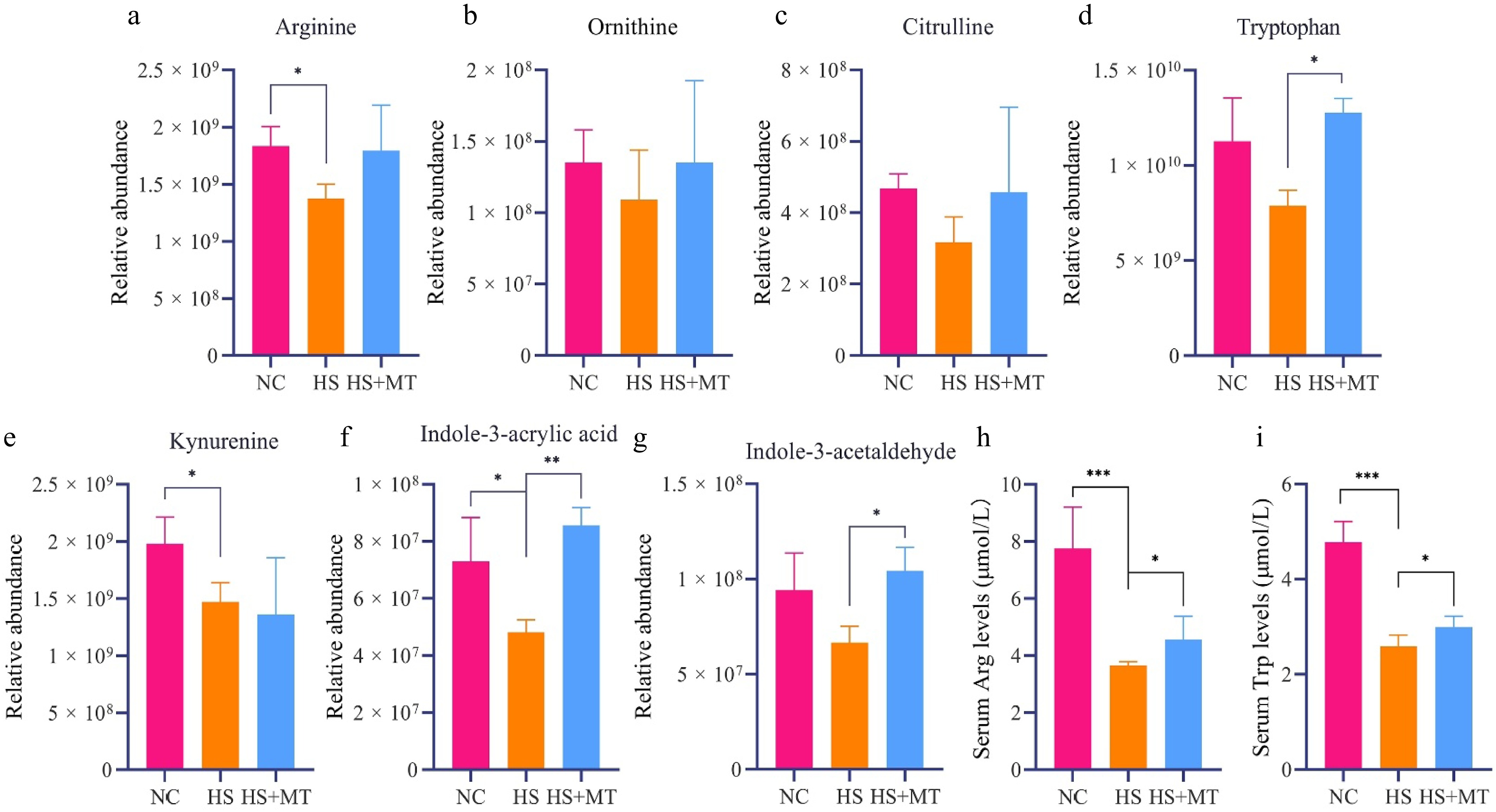

According to the untargeted metabolomic data, KEGG pathway enrichment analysis (Q < 0.05) revealed that arginine biosynthesis and tryptophan metabolism were significantly affected by HS. To verify changes in the key metabolites within these pathways, we performed targeted LC-MS/MS quantification of arginine, ornithine, tryptophan, and kynurenine using isotope-labeled standards and calibration curves (R2 > 0.99). Compared with the NC group, serum arginine levels were significantly decreased in the HS group, along with a downward trend in its downstream products, ornithine and citrulline. In the HS+MT group, these metabolites were partially restored (Fig. 4a−c), indicating that melatonin mitigated HS-induced metabolic disturbance of arginine. Similarly, the levels of tryptophan and its derivative kynurenine were significantly reduced in the HS group but significantly increased following melatonin treatment (Fig. 4d−g), suggesting that melatonin alleviated disruption of the tryptophan metabolism pathway. To validate the untargeted metabolomics results, ELISA was conducted to measure serum concentrations of arginine and tryptophan. The results confirmed that both amino acids were significantly downregulated under HS and elevated under melatonin supplementation (Fig. 4h, i). These findings support that melatonin restores amino acids' metabolic homeostasis after disruption by HS, particularly via the arginine and tryptophan pathways, which may indirectly contribute to improved sperm quality and structural integrity. This provides a potential metabolic intervention strategy to enhance reproductive performance in dairy goats under high-temperature conditions.

Figure 4.

Effects of melatonin on the serum concentrations of arginine, tryptophan, and related metabolites in heat-stressed dairy goats. (a) Relative abundance of arginine in the serum of dairy goats. (b) Relative abundance of ornithine. (c) Relative abundance of citrulline. (d) Relative abundance of tryptophan. (e) Relative abundance of kynurenine. (f) Relative abundance of indole-3-acrylic acid. (g) Relative abundance of indole-3-acetaldehyde. (h) Serum arginine levels. (i) Serum tryptophan levels. Statistical significance was as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Arginine and tryptophan metabolism can be regulated by melatonin to alleviate HS-induced sperm defects in male mice.

-

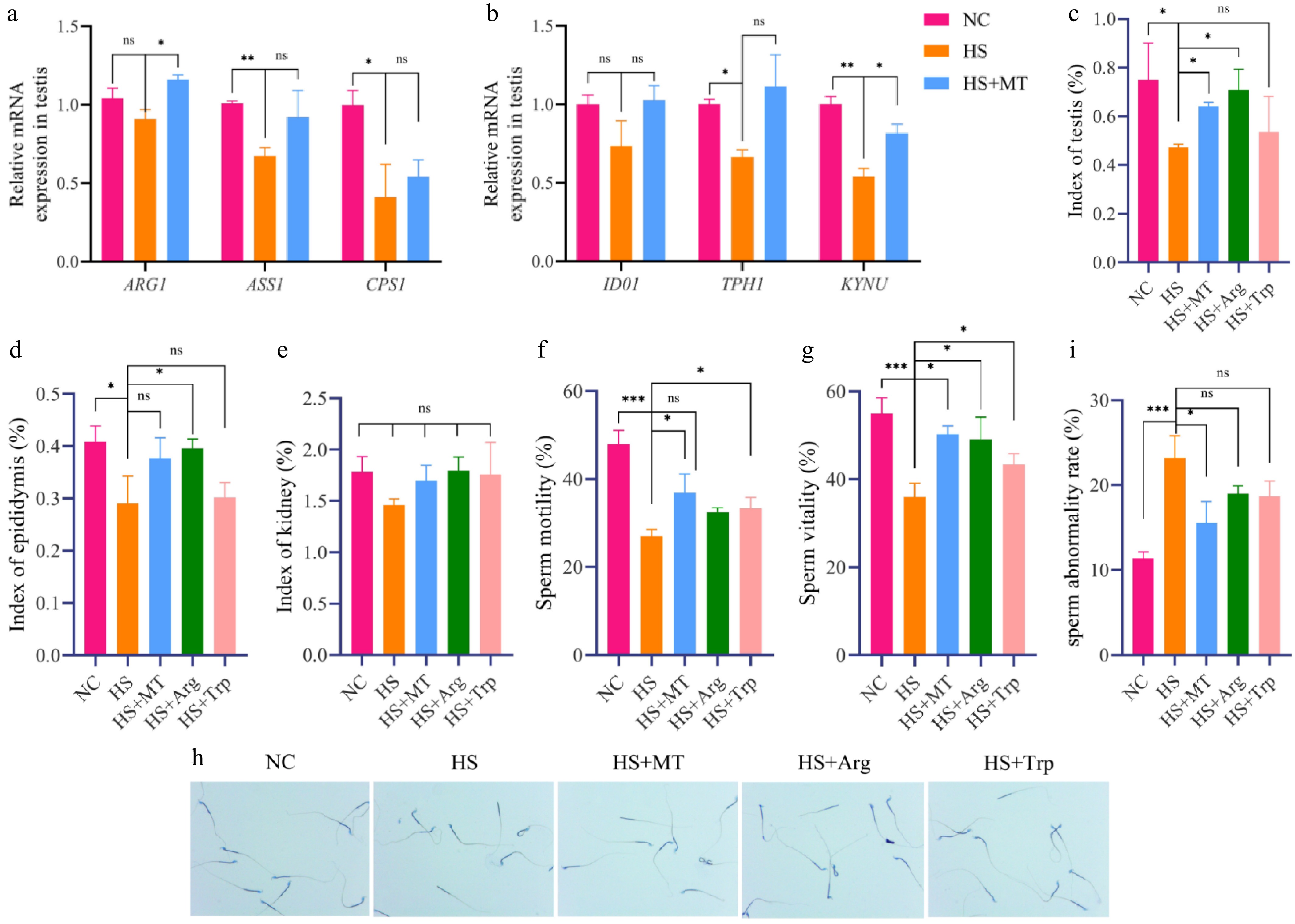

To explore whether melatonin modulates amino acid metabolism by regulating the expression of rate-limiting enzymes, we measured the mRNA levels of key metabolic enzymes in the testes of the NC, HS, and HS+MT groups. Heat stress significantly suppressed the expression of arginase-1 (ARG1), whereas melatonin treatment restored its expression (p < 0.05, Fig. 5a). In the tryptophan pathway, melatonin significantly upregulated the expression of tryptophan hydroxylase 1 (TPH1) and kynureninase (KYNU) (p < 0.05, Fig. 5b). This suggests that it may alleviate HS-related testicular injury, at least in part, by regulating the amino acid metabolism pathway. To further evaluate the protective roles of arginine and tryptophan on the testicular phenotype under HS, and to determine whether their effects resemble those of melatonin, additional groups were treated with arginine (HS+Arg) or tryptophan (HS+Trp). We assessed the morphology of the testes and epididymides in each group. Heat stress significantly decreased the testicular and epididymal organ indices (p < 0.05). Melatonin treatment significantly increased the testis index (Fig. 5c), while arginine supplementation notably improved the epididymis index (Fig. 5d). In contrast, kidney organ indices remained unchanged across all groups (Fig. 5e). Compared with the NC group, HS significantly reduced sperm's motility and viability and increased the sperm abnormality rate (p < 0.05, Fig. 5f−i). Tryptophan treatment significantly improved sperm's motility and viability, whereas arginine improved viability but had no significant effect on motility. Both treatments showed a decreasing trend in sperm abnormality rates, although the differences were not statistically significant. Crystal violet staining confirmed that HS led to structural sperm damage, which was partially alleviated by melatonin, arginine, and tryptophan. These findings indicate that arginine and tryptophan can mitigate HS-induced sperm damage and improve sperm quality, with protective effects similar to those of melatonin.

Figure 5.

Melatonin-regulated arginine and tryptophan metabolism improves sperm quality in heat-stressed mice. (a) Arginine metabolism related genes: expression levels of ARG1, ASS1, and CPS1. (b) Tryptophan metabolism-related genes: IDO1, TPH1, and KYNU expression levels. (c) Testicular organ index of mice in each group. (d) Epididymal organ index. (e) Kidney organ index. (f) Sperm motility of each group of mice. (g) Sperm vitality. (h) Crystal violet staining of sperm. (i) Sperm abnormality rate. Statistical significance was as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001; ns, no statistical significance.

Arginine and tryptophan alleviate testicular damage, inflammation, and apoptosis in heat-stressed male mice

-

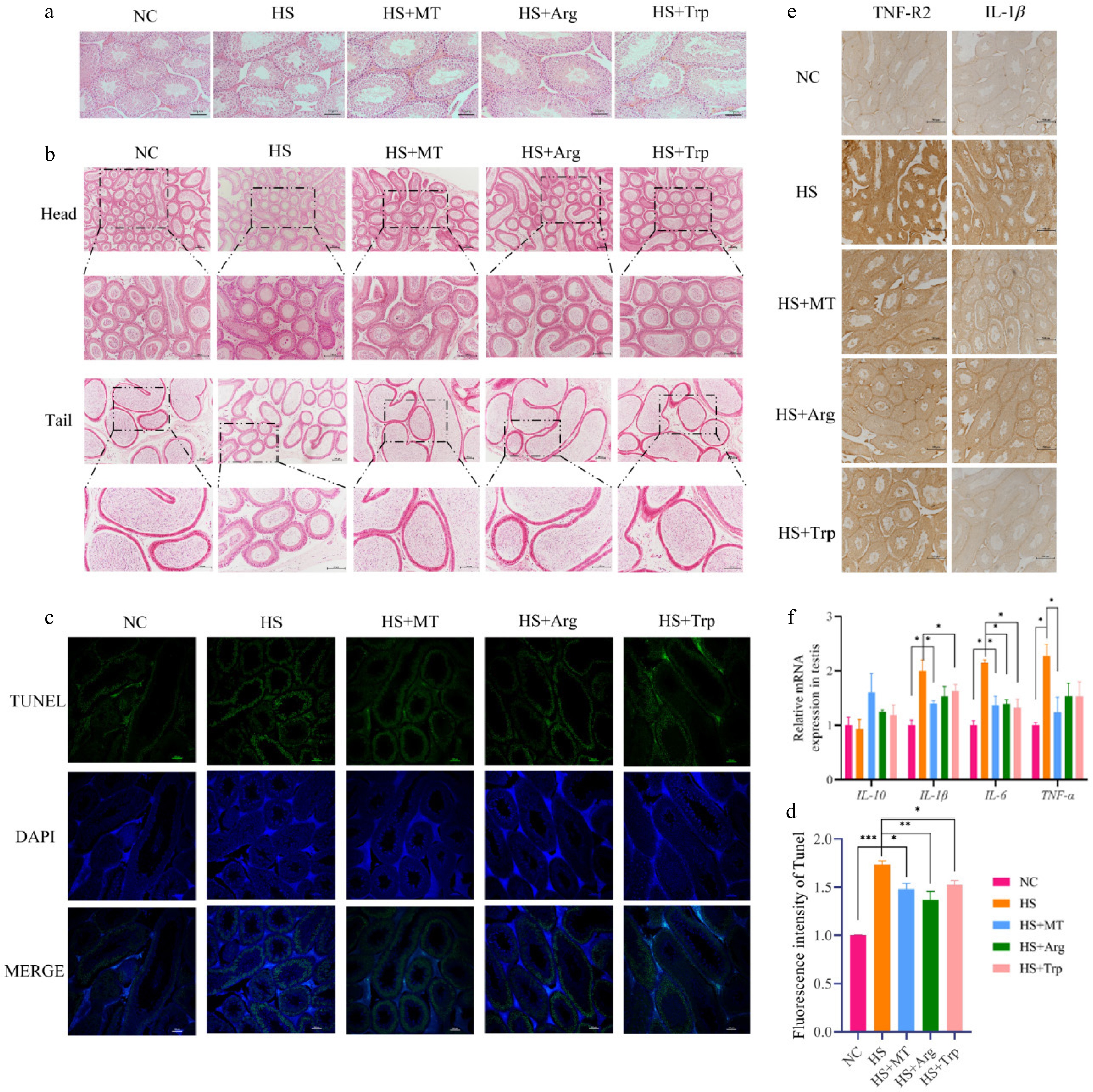

To evaluate whether arginine and tryptophan protect the testes from HS-induced damage and produce similar effects to melatonin, we examined the testicular structure using H&E staining. Compared with the NC group, the HS group exhibited severe testicular damage, characterized by disrupted seminiferous tubules, disorganized germ cells, cellular exfoliation, and expanded interstitial spaces between Sertoli and interstitial cells. In contrast, the HS+Arg and HS+Trp groups showed considerable structural improvement, including normalized tubule architecture, enlarged tubular diameter, and well-aligned spermatogenic cells, resembling the effects of melatonin (Fig. 6a). H&E staining of the epididymis revealed that HS impaired sperm maturation and storage, evidenced by narrowed the lumen in the caput and reduced sperm presence in the cauda. Arginine and tryptophan supplementation ameliorated these pathological changes and restored caudal sperm reserves (Fig. 6b). Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining demonstrated significantly increased apoptosis in Sertoli cells of the HS group, suggesting that these cells are highly vulnerable to thermal injury. Arginine and tryptophan significantly reduced testicular apoptosis compared with the HS group, with even stronger anti-apoptotic effects than melatonin (Fig. 6c). To investigate the inflammatory responses, RT-qPCR showed that mRNA levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α were significantly increased in the testes of HS mice compared with the NC group (p < 0.05), indicating local testicular inflammation. Arginine primarily reduced IL-6 expression, while tryptophan more effectively inhibited IL-1β (Fig. 6d). Immunohistochemical staining further confirmed elevated TNF-R2 and IL-1β protein levels in the HS group, which were markedly reduced following arginine or tryptophan treatment, with tryptophan showing a suppression effect similar to melatonin, particularly on IL-1β (Fig. 6e). These findings indicate that arginine and tryptophan can both inhibit the activation of pro-inflammatory pathways, effectively alleviating the testicular inflammatory responses caused by HS while also reducing apoptosis of the supporting cells, producing similar effects to melatonin.

Figure 6.

Effects of arginine and tryptophan on testicular tissue in heat-stressed mice. (a) H&E staining of testicular tissue; scale bar = 50 μm. (b) H&E staining of epididymal tissue; scale bar = 100 μm. (c) TUNEL staining was used to detect testicular cell apoptosis (green); scale bar = 100 μm. (d) Expression of inflammation-related genes in testicular tissue. (e) Immunohistochemical detection of TNF-R2 and IL-1β; scale bar = 500 μm. Statistical significance was as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Arginine and tryptophan alleviate heat stress-induced disruption of the BTB in male mice

-

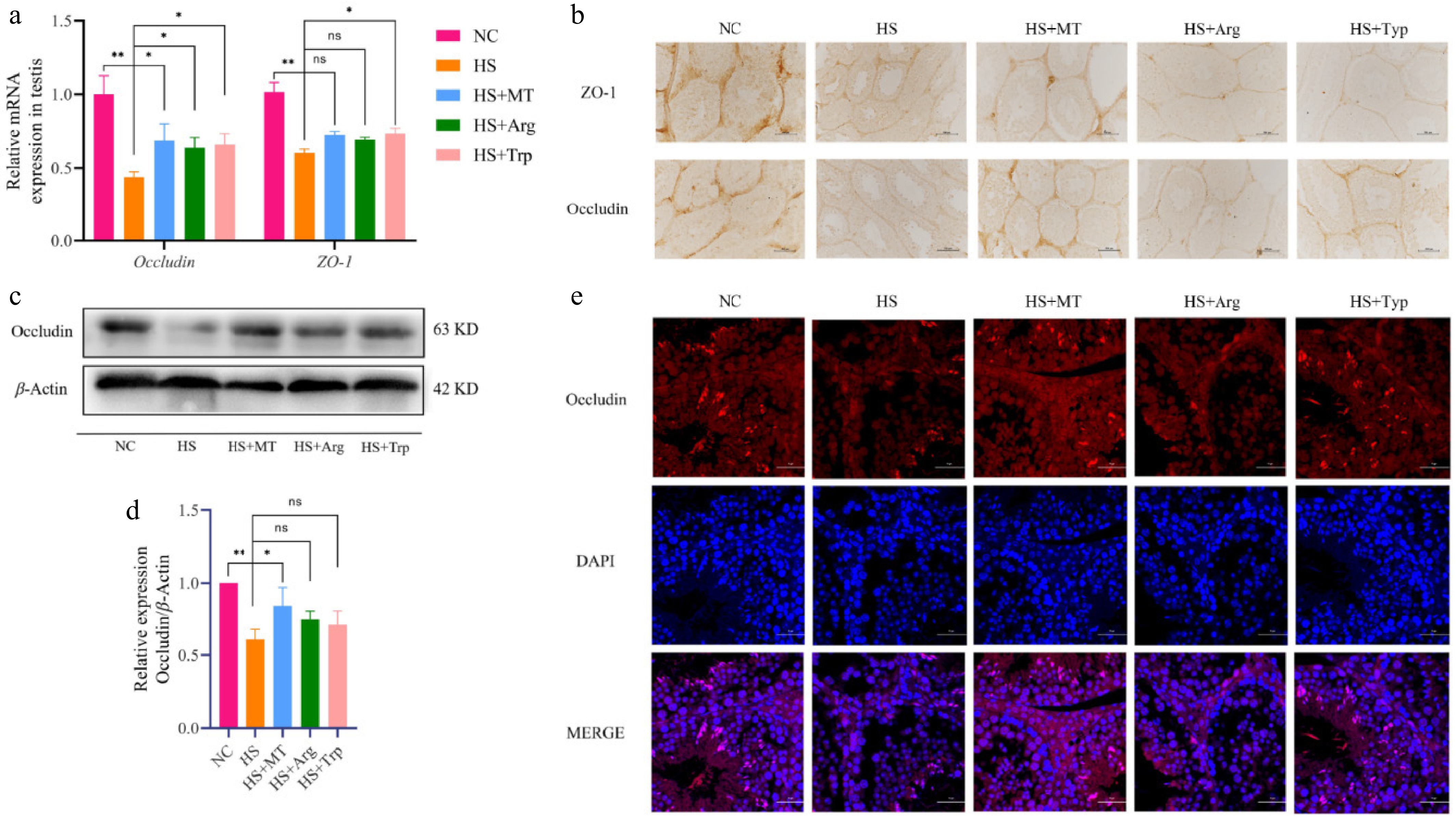

To assess whether arginine and tryptophan protect the integrity of the BTB, we examined the expression of these proteins at multiple levels. The RT-qPCR results revealed that occludin and ZO-1 mRNA levels were significantly reduced in the HS group compared with the NC group, whereas both arginine and tryptophan supplementation elevated their expression, with a more pronounced effect on occludin (Fig. 7a). Immunohistochemical analysis showed that protein expression of occludin and ZO-1 levels were weakened under HS but partly restored following tryptophan treatment, reaching levels similar to the NC group. Arginine also exerted a moderate restorative effect (Fig. 7b). Western blotting confirmed that protein levels of occludin were significantly reduced in the HS group and markedly increased in both the HS+Arg and HS+Trp groups, approaching the levels seen in the HS+MT and NC groups (Fig. 7c, d). Immunofluorescence staining further indicated that the localization of occludin in the HS group was disorganized and diffused around Sertoli and interstitial cells, suggesting the BTB's structural breakdown. In contrast, arginine and tryptophan restored occludin's localization, showing clearer membrane contours, continuous distribution, and improved nuclear and cytoplasmic integrity (Fig. 7e). In summary, arginine and tryptophan significantly promote the expression and localization of spermatogenic tight junction proteins and enhance the stability of the BTB's structure, thereby alleviating barrier damage caused by HS, similar to melatonin.

Figure 7.

Effects of arginine and tryptophan on the expression of tight junction-related genes and proteins in testicular tissue of heat-stressed mice. (a) mRNA expression levels of tight junction-related genes. (b) The expression levels of ZO-1 and occludin were analyzed using immunohistochemistry; scale bar = 500 μm. (c) Western blot analysis of protein expression of occludin in testicular tissues from each group. (d) Grayscale analysis of the proteins of occludin. (e) Immunofluorescence staining showing the localization of occludin (red) in testicular tissue, with the nuclei counterstained by DAPI (blue); scale bar = 20 μm. Statistical significance was as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01; ns, no statistical significance.

Arginine and tryptophan alleviate HS-induced impairment of testosterone synthesis in male mice

-

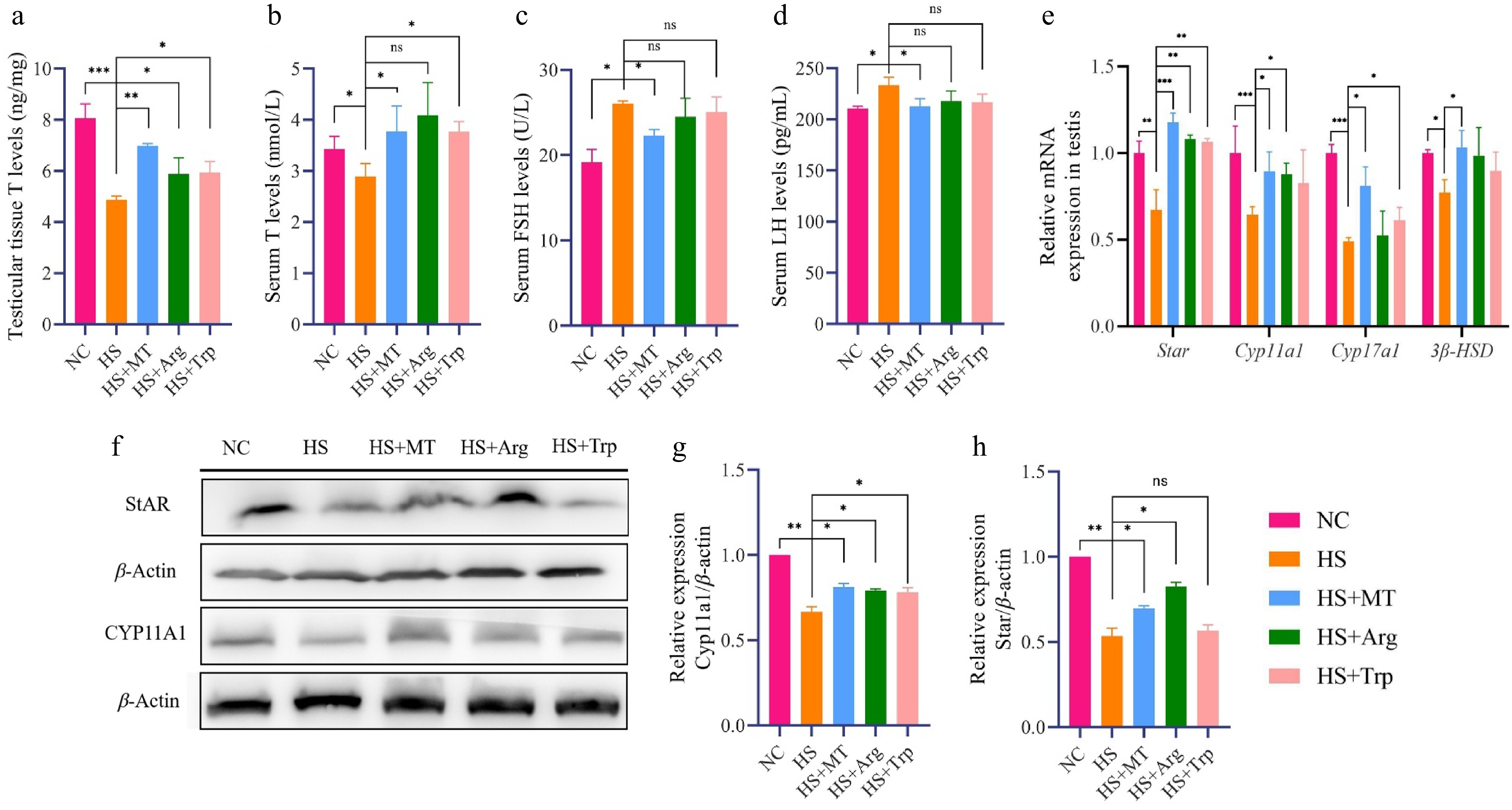

To explore the mechanisms by which arginine and tryptophan mitigate spermatogenic dysfunction under HS, testosterone levels were measured in both testicular tissue and serum. As shown in Fig. 8a, b, HS significantly reduced testosterone levels compared with the NC group. Arginine and tryptophan supplementation restored testosterone concentrations to similar levels to those in the HS+MT and NC groups, indicating a reversal of HS-induced testosterone synthesis disorder. Heat stress also markedly increased serum FSH and LH levels (Fig. 8c, d). Although arginine and tryptophan did not significantly alter these gonadotropins, a trend toward normalization was observed, suggesting a potential stabilizing effect on reproductive hormone balance, albeit not as pronounced as that of melatonin. To further investigate their role in steroidogenesis, we assessed the expression of key steroidogenic genes. RT-qPCR showed that mRNA levels of Star, Cyp11a1, Cyp17a1, and 3β-HSD were significantly downregulated in the HS group, whereas arginine significantly upregulated Star and Cyp11a1, and tryptophan elevated the expression of Star and Cyp17a1 (Fig. 8e). Protein-level analysis via Western blotting confirmed these findings: The expression levels of StAR and CYP11A1 were suppressed under HS but significantly restored by the arginine and tryptophan treatments (Fig. 8f−h). Arginine and tryptophan can activate the steroidogenesis pathway, enhance testosterone synthesis capacity, and restore the homeostasis of reproductive hormone synthesis, thereby alleviating reproductive hormone secretion disorders caused by HS.

Figure 8.

Effects of arginine and tryptophan on the expression of testosterone synthesis-related genes and proteins in heat-stressed mice. (a) Testosterone concentrations in the testicular tissue of each group. (b) Serum testosterone (T) concentrations. (c) Serum FSH concentrations. (d) Serum LH concentrations. (e) RT-qPCR analysis of steroidogenesis-related gene expression levels in testicular tissue. (f) Western blot analysis of steroidogenic proteins in testicular tissue. (g) Grayscale analysis of the proteins of StAR. (h) Grayscale analysis of the proteins of CYP11A1. Statistical significance was as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001; ns, no statistical significance.

-

Heat stress is a major environmental factor that negatively impacts male reproductive performance, primarily by disrupting spermatogenesis and impairing sperm quality. In this study, heat-stressed dairy goats exhibited decreased sperm density, motility, and viability, along with an increased rate of abnormal sperm morphology, consistent with previous reports[18,19]. These alterations were accompanied by systemic oxidative stress and elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines. Melatonin supplementation, administered before HS, restored serum melatonin concentrations and effectively improved sperm parameters, underscoring its protective potential.

Mechanistically, oxidative stress plays a central role in heat-induced sperm dysfunction. Excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) damage sperm membranes that are rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids, resulting in DNA fragmentation and structural abnormalities[20]. Additionally, heat-induced mitochondrial ROS overproduction can lead to premature capacitation, reduced fertilization potential, and germ cell apoptosis[21]. Melatonin significantly reduced serum ROS concentrations, increased antioxidant capacity (GSH, T-AOC, and SOD), and downregulated pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α), indicating its dual antioxidative and anti-inflammatory effects. These findings are consistent with earlier studies demonstrating that melatonin not only scavenges ROS directly but also upregulates antioxidant enzymes while stabilizing mitochondrial function, thereby alleviating oxidative damage under HS conditions[22]. By preventing ROS accumulation and supporting antioxidant defense systems, melatonin helps preserve membranes' integrity and sperm function[23].

Heat stress also impaired endocrine homeostasis by decreasing testosterone levels and elevating serum FSH and LH levels, suggesting dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal (HPG) axis[24]. Melatonin treatment restored testosterone concentrations and partly normalized gonadotropin levels, potentially by reducing oxidative damage in Leydig cells and modulating the secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)[25]. This highlights melatonin's ability to maintain hormonal balance and support spermatogenesis under thermal stress. This hormonal dysregulation likely results from oxidative and inflammatory injury to Leydig cells, disrupting steroidogenesis and triggering a compensatory rise in gonadotropins due to reduced negative feedback[26]. Previous work showed that melatonin alleviates this effect by modulating the release of GnRH and suppressing excessive LH and FSH secretion[27]. This dual mechanism—protecting Leydig cells and restoring the HPG axis homeostasis—emphasizes melatonin's endocrine-modulating properties under thermal stress.

Importantly, untargeted metabolomics revealed substantial changes in amino acid and lipid metabolism in response to HS. Among the altered pathways, tryptophan and arginine metabolism were significantly affected. Melatonin partly corrected these metabolic disruptions. Arginine is a precursor for nitric oxide and polyamines, both of which are essential for testicular blood flow, germ cell proliferation, and Sertoli cell function[28]. Tryptophan, through the serotonin and kynurenine pathways, participates in endocrine regulation and immune tolerance[29,30]. Our results further confirmed that heat stress suppressed arginine and tryptophan levels in the serum, aligning with findings from human and animal studies linking amino acid deficiencies to impaired fertility and metabolic imbalance[15,31]. Melatonin's ability to reverse these reductions, particularly via regulation of key enzymes such as ARG1 and KYNU, suggests a direct metabolic axis through which it restores amino acid homeostasis and testicular function[32].

Targeted quantification confirmed that melatonin restored serum levels of arginine and tryptophan. Additionally, melatonin upregulated the expression of key rate-limiting enzymes (ARG1 and KYNU), activating amino acid metabolic pathways in the testes. These findings were further supported by supplementation experiments, in which arginine and tryptophan alone alleviated HS-induced sperm defects and histological damage, similar to melatonin. Moreover, administration of arginine and tryptophan partly rescued testicular morphology and function by improving sperm's motility and viability and by reducing morphological abnormalities. This supports their independent roles in promoting spermatogenesis and protecting germ cells' integrity under HS[33,34]. Emerging evidence also indicates that dietary tryptophan may influence gut microbiota-derived metabolites, which, in turn, modulate testicular oxidative stress and inflammation, providing an additional pathway for systemic protection[35] Interestingly, tryptophan showed a more prominent effect on testosterone's recovery, whereas arginine exerted stronger upregulation of StAR and Cyp11a1, pointing to differential regulatory routes in steroid biosynthesis[36,37].

Moreover, HS significantly downregulated the expression of tight junction proteins occludin and ZO-1, indicating disruption of the BTB. Both arginine and tryptophan restored the transcription, translation, and membrane localization of these proteins, thereby enhancing the BTB's integrity and improving the testicular microenvironment's stability. These changes were accompanied by reduced testicular apoptosis, improved germ cell arrangement, and lower inflammation, as shown by the downregulation of IL-1β and TNF-R2 in the histological analyses[38]. Recent evidence suggests that amino acid supplementation may directly enhance the BTB's integrity by modulating autophagy and the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway. For example, dietary folic acid was shown to improve semen quality in aging roosters by activating autophagy via the mTOR pathway and restoring tight junction protein levels (Beclin-1, ATG5, LC3-II/LC3-I) while suppressing the expression of phosphorylated mTOR[39]. This highlights that BTB repair is central to reversing heat-induced testicular injury and that amino acid supplementation may stabilize the BTB via anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory signaling[40].

At the molecular level, heat stress inhibited the transcription of steroidogenic genes (Star, Cyp11a1, Cyp17a1), leading to reduced testosterone synthesis[41]. Arginine and tryptophan treatment restored both mRNA and protein levels of StAR and CYP11A1, suggesting their involvement in steroidogenic recovery. Interestingly, tryptophan showed stronger effects on testosterone restoration, whereas arginine more potently upregulated StAR expression, possibly because of distinct downstream signaling pathways (e.g., serotonin/cAMP vs. NO/cGMP)[36,37].

In conclusion, melatonin protects against HS-induced reproductive dysfunction through antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, hormonal, and metabolic regulatory mechanisms. Arginine and tryptophan partly replicate these effects, highlighting the central role of amino acid metabolism in adaptation to HS. These findings provide novel insights into integrative strategies for improving reproductive resilience in male livestock under thermal stress. These insights extend our understanding of how systemic metabolism intersects with reproductive function, and we propose a multi-level strategy targeting redox balance, endocrine integrity, and metabolic pathways to enhance reproductive resilience in heat-stressed males[42,43]. Further studies integrating metabolomics, transcriptomics, and functional assays are warranted to elucidate the coordinated network underlying this protection.

-

This study reveals that melatonin enhances testicular arginine and tryptophan metabolism by regulating body metabolism, alleviates the decline in sperm quality caused by HS in dairy goats, enhances intercellular connectivity in testicular tissue by reducing inflammation and oxidative stress reactions in the body, and promotes the synthesis of steroid hormones. Melatonin effectively alleviates the impaired sperm production caused by HS in dairy goats.

This work was supported by the Grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China [2022YFD1300200], Central Government Guidance Fund for Local Science and Technology Development Program of Qinghai Province (2025-ZY-069), Horizontal Research Funding from Ningbo Second Hormone Factory (TG20250168). The authors gratefully acknowledge all members of the research team for their technical assistance and valuable discussions.

-

All experimental procedures were reviewed and approved in advance by the Animal Ethical and Welfare Committee of Northwest A&F University (Approval No. 201902A299, date: 2019-02-25). The study strictly adhered to the principles of replacement, reduction, and refinement (the 3Rs) to minimize animal use and suffering. Details regarding the animals' housing, care, and handling were thoroughly documented to ensure minimal impact on the animal's welfare during the course of the experiment.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization, project administration, and supervision: Peng S, Ma BH; methodology and experimental investigation: Wang M, Fu TS, Wang XQ, Chen MW, Zhou HD, Bai XN, Li FE; data curation and analysis: Wang M, Fu TS, Zhou HD, Li Y; visualization and figure preparation: Wang XQ, Chen MW, Wang M, Aierken A; writing – original draft: Wang M, Zhou HD; writing – review and editing: Peng S, Ma BH, Hu LY. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Summary of reagents and materials.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wang M, Fu TS, Wang XQ, Chen MW, Zhou HD, et al. 2026. Melatonin alleviates the heat-stress-induced decline in sperm quality in dairy goats by regulating amino acid metabolism. Animal Advances 3: e008 doi: 10.48130/animadv-0025-0041

Melatonin alleviates the heat-stress-induced decline in sperm quality in dairy goats by regulating amino acid metabolism

- Received: 20 May 2025

- Revised: 04 August 2025

- Accepted: 08 September 2025

- Published online: 11 February 2026

Abstract: Heat stress severely impairs male reproductive performance in dairy goats by disrupting testicular function, antioxidant defense, and metabolic homeostasis. This study investigated the protective mechanisms of melatonin using both natural and artificial heat stress models in dairy goats and mice. In goats, we found that heat stress significantly reduced sperm's motility, viability, and density while increasing the levels of oxidative stress markers (reactive oxygen species [ROS], malondialdehyde [MDA]) and pro-inflammatory cytokines (interleukin [IL]-1β, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-α). Pre-treatment with melatonin implants restored serum melatonin levels, enhanced antioxidant capacity (glutathione [GSH], total antioxidan capacity [T-AOC]), and ameliorated inflammatory responses, ultimately improving sperm quality. Untargeted metabolomic profiling uncovered that heat stress induced systemic metabolic dysregulation, with significant enrichment in the arginine and tryptophan pathways. Melatonin supplementation partly corrected these disruptions and restored the serum levels of both amino acids. In the murine model, melatonin significantly alleviated the testicular damage induced by heat stress by reducing apoptosis, preserving the integrity of the blood–testis barrier (BTB) through the upregulation of occludin and ZO-1, and improving the histological architecture of the seminiferous tubules and epididymis. Further, we observed that melatonin increased the expression of key rate-limiting enzymes involved in arginine (ARG1) and tryptophan (TPH1, KYNU) metabolism and activated steroidogenic genes (Star, Cyp11a1), restoring testosterone production under heat stress conditions. Supplementation with arginine or tryptophan alone also alleviated heat stress-induced sperm abnormalities and testicular injury, confirming the functional relevance of these pathways. These findings demonstrate that melatonin protects against heat stress-induced male reproductive dysfunction by modulating oxidative stress, inflammation, amino acid metabolism, and steroidogenesis. Targeting arginine and tryptophan metabolism may represent an effective strategy for improving livestock's fertility under thermal stress.

-

Key words:

- Sperm /

- Amino acid /

- Melatonin /

- Heat stress /

- Dairy goat