-

Zinc (Zn) is an essential trace element involved in numerous physiological functions in swine, including growth, immune regulation, enzymatic activity, and antioxidant defense[1]. Traditionally, pharmacological doses of inorganic zinc sources, particularly zinc oxide (ZnO), have long been used in piglets' diets for their antimicrobial and gut-protective properties to prevent postweaning diarrhea and enhance growth[2−4]. However, the low bioavailability of ZnO (approximately 20%) results in excessive zinc excretion, contributing to environmental accumulation and soil contamination[5]. Moreover, high-dose ZnO supplementation has been linked to the co-selection of antibiotic resistance genes, including those conferring resistance to tetracyclines, sulfonamides, and methicillin[6−8]. These environmental and public health concerns have led to strict regulatory actions, including the EU-wide ban on medicinal ZnO use from 2022. Consequently, there is growing interest in alternative zinc sources with higher bioavailability, a reduced ecological footprint, and added physiological or immunological benefits.

Cysteamine (CS), a small aminothiol compound derived from the metabolism of Coenzyme A, has been reported to modulate the somatotropic axis, stimulate growth, and enhance antioxidant capacity in livestock[9]. However, its practical application is limited by its chemical instability, susceptibility to oxidation in the air, poor palatability, and strong odor, all of which may negatively affect feed intake[9,10]. In addition, high doses of CS have been shown to induce gastrointestinal damage, including duodenal ulcers and perforation in rodents[11]. To overcome these limitations, cysteamine hydrochloride is commonly used as a more stable substitute in animal nutrition.

Cysteamine-chelated zinc (Zn-CS), as a novel organic trace mineral complex, combines the growth-promoting and metabolic regulatory functions of cysteamine with the structural and catalytic roles of zinc, making it a promising dietary additive in pig production. This chelate combines the biological functions of both cysteamine and organic zinc, potentially enhancing their bioavailability through synergistic interactions. Compared with conventional zinc sources, Zn-CS exhibits several advantages, including improved chemical stability, greater metabolic activity, endocrine modulation, and minimal adverse effects[12]. It may also support hormonal homeostasis, enhance the palatability of feed, and improve feed conversion efficiency.

Although Zn-CS has theoretical potential, its efficacy and safety in pigs have not been comprehensively evaluated. In particular, the dose-response relationship and optimal supplementation level remain undefined. Excessive intake of trace minerals can lead to metabolic imbalance, tissue accumulation, or toxic effects; therefore, determining the appropriate dosage that maximizes the biological benefits without compromising safety is essential. Additionally, improvements in growth performance should be accompanied by enhanced nutrient digestibility, intestinal morphology, and systemic health indicators to substantiate the physiological relevance of Zn-CS supplementation.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the effects of dietary Zn-CS supplementation at graded levels on the growth performance, apparent total tract digestibility (ATTD) of nutrients, intestinal morphology, tight junction protein expression, serum biochemical indices, and histopathological changes in major organs in weaned-to-finished pigs. Furthermore, carcass characteristics and muscle fiber profiles were assessed to investigate the potential impact of Zn-CS on meat quality. These findings aim to provide a scientific basis for the practical application of Zn-CS as a safe and effective feed additive in modern swine production systems.

-

All animal procedures were carried out at the Jilin University Agricultural Experiment Base. The study protocol received approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Jilin University (permit number: SY202505022).

Animals, diets, and experimental design

-

In total, 144 healthy weaned piglets (Dongliao Black pigs; average initial body weight: 10.12 ± 0.03 kg; age: 45 ± 3 days) were selected for the experiment. To minimize potential variations in growth performance caused by differences in the severity of postweaning diarrhea, the trial was initiated at 45 days of age, when the piglets' health status had stabilized, and only clinically healthy individuals were included. The piglets were randomly allocated to four dietary treatments, with each treatment consisting of six replicate pens and six pigs per pen. The control group received a basal diet, whereas the experimental groups were fed the basal diet supplemented with 150, 300, or 450 mg/kg of Zn-CS. The Zn-CS product contained 15% of the active compound (Zn-CS), with zeolite powder serving as the carrier, and was supplied by BAIKANG Biotechnology Engineering Co., Ltd. (Shenzhen, China). Notably, the premix used in the basal diet contained no additional source of zinc, and Zn-CS served as the sole source of dietary zinc. Feed and water were offered ad libitum throughout the trial. The detailed formulation and nutrient composition of the diets are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Ingredient composition and nutrient content of the basal diet (as-fed basis, %).

Ingredients Period 1

0–14 dPeriod 2

15–28 dPeriod 3

29–143 dPeriod 4

144–192 dCorn 60.43 63.57 73.00 71.30 Soybean meal 10.45 12.85 15.10 13.34 Wheat flour 8.00 6.00 Extruded full-fat soybean 8.00 8.00 Wheat bran 4.00 2.30 8.00 12.00 Fish meal 2.00 Soybean oil 1.20 1.00 Limestone 0.77 0.85 1.56 1.61 Dicalcium phosphate 0.75 0.98 0.44 0.35 Sodium chloride 0.40 0.45 0.40 0.40 Premix1 4.00 4.00 1.50 1.00 Calculated nutritional levels CP (%) 17.00 16.50 14.50 14.00 DM (%) 86.64 86.64 86.46 86.46 Ash (%) 4.78 4.71 4.52 4.58 NFE (%) 56.47 57.44 61.48 61.57 EE (%) 5.55 5.21 2.87 2.89 CF (%) 2.84 2.79 3.09 3.42 Ca (%) 0.60 0.60 0.75 0.75 Total P (%) 0.51 0.51 0.40 0.40 GE (kcal/kg) 3,894 3,873 3,777 3,774 Lysine (%) 1.2000 1.2068 0.9606 0.8906 Methionine (%) 0.4043 0.4121 0.2831 0.2492 Threonine (%) 0.8418 0.8156 0.6496 0.5858 Tryptophan (%) 0.2713 0.2648 0.1594 0.1414 1 The premix provided the following per kg of complete diet. Periods 1 and 2: vitamin A, 16,000 IU; vitamin D3, 5,000 IU; vitamin E, 24.0 IU; vitamin K3, 2.8 mg; vitamin B1, 1.2 mg; vitamin B2, 7.35 mg; vitamin B6, 1.14 mg; niacinamide, 35.0 mg; pantothenic acid, 19.85 mg; folacin, 0.7 mg; biotin, 70.00 μg; Fe, 450.0 mg; Cu, 125.0 mg; Mn, 150.0 mg; I, 0.625 mg; Se, 0.5 mg. Period 3: vitamin A, 65,000 IU; vitamin D3, 5,000 IU; vitamin E, 13.6 IU; vitamin K3, 1.4 mg; vitamin B1, 0.7 mg; vitamin B2, 4.6 mg; vitamin B6, 0.75 mg; niacinamide, 16.0 mg; pantothenic acid, 10 mg; Fe, 350.0 mg; Cu, 25.0 mg; Mn, 150.0 mg; Se, 0.5 mg. Period 4: vitamin A, 5,200 IU; vitamin D3, 4,000 KIU; vitamin E, 10.88 IU; vitamin K3, 1.12 mg; vitamin B1, 0.56 mg; vitamin B2, 3.68 mg; vitamin B6, 0.6 mg; niacinamide, 12.8 mg; pantothenic acid, 8.0 mg; Fe, 280.0 mg; Cu, 20.0 mg; Mn, 120.0 mg; Se, 0.4 mg. NFE, nitrogen-free extract; CF, crude fiber. Sample collection

-

The experiment continued until the pigs reached a final body weight of approximately 100 kg, corresponding to Day 192 of the trial. Body weight (BW) and feed intake were recorded per pen on Days 0, 14, and 28 and the end of the trial. Based on these data, the average daily gain (ADG), average daily feed intake (ADFI), and feed-to-gain ratio (F:G) were calculated. Blood samples were obtained on Days 14 and 28. From Days 25 to 28, fresh fecal samples were collected, pooled by treatment, and subsequently analyzed for nutrient digestibility.

The first slaughter was conducted on Day 28. On the basis of the growth performance data, the optimal dosage group (150 mg/kg) was identified. One pig with a body weight close to the pen average was chosen from each pen of both the control and the optimal treatment groups. The selected pigs were humanely euthanized by electrical stunning followed by exsanguination. Samples of the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and longissimus dorsi muscle were collected.

At the end of the trial (Day 192), the same slaughter procedure was carried out. Duodenal, jejunal, ileal, liver, kidney, and longissimus dorsi muscle samples were collected for further analysis.

Nutrient digestibility

-

The ATTD of dry matter (DM), crude protein (CP), ether extract (EE), gross energy (GE), calcium (Ca), and phosphorus (P) was determined using the indigestible marker method, with acid-insoluble ash (AIA) as the internal marker. Determination of DM in fecal and diet samples followed AOAC Method 930.15[13]. Ash, CP, and EE were analyzed according to AOAC (2007) Methods 942.05, 990.03, and 996.01, respectively. GE was measured using an adiabatic bomb calorimeter (Parr 1281, Automatic Energy Analyzer; Moline, IL, USA), whereas Ca and P were quantified following standard procedures. The ATTD of nutrients was calculated using the following equation:

$ \mathrm{A}\mathrm{T}\mathrm{T}\mathrm{D}\;\mathrm{o}\mathrm{f}\;\mathrm{n}\mathrm{u}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{t}\;\left({\text{%}}\right)=\left(1-\frac{\mathrm{A}\mathrm{I}{\mathrm{A}}_{\mathrm{d}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{t}}\times \mathrm{N}\mathrm{u}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{n}{\mathrm{t}}_{\mathrm{f}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{c}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{s}}}{\mathrm{A}\mathrm{I}{\mathrm{A}}_{\mathrm{f}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{c}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{s}}\times \mathrm{N}\mathrm{u}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{n}{\mathrm{t}}_{\mathrm{d}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{t}}}\right)\times 100 $ Blood analysis

-

On Days 14 and 28, blood samples (5 mL) were obtained from six randomly chosen pigs per group (control and 150 mg/kg Zn-CS groups) via puncture of the anterior vena cava. Following collection, samples were kept at room temperature for 2–3 h and then centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 10 min. The separated serum was aliquoted and stored at −80 °C until further analysis. Serum triiodothyronine (T3), thyroxine (T4), and insulin concentrations were quantified using an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay system (Elecsys 2010 analyzer, Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Blood glucose levels were determined with an automatic biochemical analyzer (Hitachi 7020, Japan).

Intestinal and organ histology

-

Segments of the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum were collected on Days 28 and 192 after carefully removing the luminal contents. The tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, sectioned into 4-μm slices, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Slides were examined using a light microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ci, Japan) equipped with a digital camera (Nikon DS-FI2, Japan). Villus height and crypt depth were measured on 10 villi and 10 crypts across five representative fields, focusing on regions where the villi were intact and attached to the lumen. All histological evaluations were conducted by a qualified histopathologist.

On Day 192, liver and kidney tissues were collected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, processed as above, and subjected to histopathological examination by the same expert. The histopathological scoring criteria for the intestine, liver, and kidney were based on a semi-quantitative system evaluating the degree of epithelial damage, inflammatory cell infiltration, and tissue architecture integrity, following previously described methods[14].

Western blot analysis

-

Jejunal samples were homogenized on ice in a radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Bosterbio, USA) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Apexbio, China). After 30 min of incubation, the homogenates were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, and the supernatants were collected. Protein concentration was measured with a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay kit (Cwbiotech, Beijing, China) and normalized to 5 µg/µL for uniform loading.

Equal amounts of protein (30 µg, 6 µL per lane) were mixed with 5× sodium dodecyl-sulfate (SDS) loading buffer (250 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8; 10% SDS; 50% glycerol; 0.02% bromophenol blue; 10% β-mercaptoethanol), boiled for 5 min at 95 °C, and separated on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) gels. Proteins were electrophoretically transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, USA) using a wet transfer system (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, and 20% methanol; pH 8.3) at 100 V for 90 min at 4 °C. After blocking with 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline–Tween (TBST) (20 mM Tris-HCl, 137 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20; pH 7.6) for 1 h, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies (details in Table 2). Following three washes in TBST (10 min each), horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies were applied for 1 h at room temperature. After additional washes, protein bands were visualized using the ECL Plus™ reagent (Millipore, USA) and imaged with a ChemiDoc™ XRS+ system (BIO-RAD). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) served as the internal reference protein.

Table 2. Primary and secondary antibodies used for Western blot labeling.

Antigen Host Dilution Source Cat# Occludin Rabbit 1:40,000 Proteintech 80545-1-RR Claudin-1 Rabbit 1:3,000 Proteintech 28674-1-AP ZO-1 Rabbit 1:10,000 Proteintech 21773-1-AP GAPDH Rabbit 1:10,000 Proteintech 10494-1-AP RNA extraction andreal-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

-

Total RNA was isolated from longissimus dorsi samples using the HiPure Total RNA Mini Kit (Magen, Guangzhou, China). cDNA synthesis was carried out with the PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit (Takara, Japan). RNA purity and concentration were verified with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and integrity was checked by agarose gel electrophoresis. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of RNA in a 20-µL reaction system with gDNA Eraser (Takara Biotechnology Co. Ltd., Otsu, Shiga, Japan).

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed using TB Green™ Premix Ex Taq™ II (Takara, Japan) on a LightCycler® 480 System (Roche, Germany). Each 20-μL reaction included 10 μL of Premix, 0.4 μL of each primer (10 μM), 0.4 μL of ROX reference dye, 2 μL of the cDNA template, and 6.8 μL of nuclease-free water. The thermocycling conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 30 s. A melting curve from 65 to 95 °C (0.5 °C increments every 5 s) confirmed product specificity. The primer sequences are shown in Table 3. GAPDH was used as the internal control. All reactions were performed in triplicate, and amplification efficiency was assessed with standard curves. Relative expression was determined by using the 2-∆∆Ct method.

Table 3. Primers for real-time PCR.

Gene Primer sequence (5'–3') MHC I Forward (F): CGTGGACTACAACATCATAGGC Reverse (R): CTTTGCCCTTCTCAACAGGT MHC IIa F: GGAGATCGACGACCTTGCTA R: CTCCTTGGATTTCAGCTCGC MHC IIx F: GAAACCGTCAAGGGTCTACG R: CGCTTCCTCAGCTTGTCTCT MHC IIb F: GTTCTGAAGAGGGTGGTAC R: AGATGCGGATGCCCTCCA GAPDH F: CTGCCGCCTGGAGAAACCT R: GCTGTAGCCAAATTCATTGTCG Carcass traits and meat quality

-

On Day 192, one representative pig per pen (n = 6 per group) was selected from both the control and optimal Zn-CS groups (150 mg/kg) and slaughtered in a commercial facility. The dressing percentage was calculated as the ratio of carcass weight to live body weight. Carcass length was measured both straight (from the atlanto-occipital joint to the pubic symphysis) and oblique (from the first rib–sternum junction to the pubic symphysis).

Backfat thickness was measured at the shoulder, last rib, and lumbosacral regions, with three replicates at each site, and averaged to a precision of 0.1 mm. The dimensions of the longissimus dorsi at the last rib were recorded, and the loin eye area was estimated as loin eye area (cm2) = length of the longissimus dorsi (cm) × width of the longissimus dorsi (cm) × 0.7.

Meat color was assessed on-site after slaughter using the official NPPC color standards (USA). Meat color (Minolta CR410, Japan) was measured 45 min postmortem, and pH was determined at 3 and 24 h postmortem using a portable pH meter (Testo 205, Germany), with each measurement performed in triplicate and averaged.

For drip loss, approximately 100 g of the longissimus dorsi muscle was collected within 1–2 h postmortem, sealed in plastic, and suspended at 4 °C for 24 h without direct contact between the tissue and the bag. Weight loss was expressed as the percentage of drip loss. For shear force, another 100-g sample was stored at 4 °C for 24 h then heated in water until it reached 70 °C at the core. After blotting, 10 cylindrical cores were prepared perpendicular to the fibers, and shear force was measured using a tenderness meter (C-LM 3B, Tenovo, China).

Free amino acid analysis

-

Because hydrolyzed amino acids reflect nutritional value, whereas free amino acids contribute to meat's flavor, profiling free amino acids is critical for characterizing the flavor of Dongliao Black pig, a breed known for superior meat quality.

Approximately 0.3 g of freeze-dried longissimus dorsi samples was mixed with 8 µL of an internal standard (2.5 mM D-phenylalanine) and 5 mL of methanol/water (8:2, v/v). Ultrasonic extraction was performed for 5 min at 1-min intervals, repeated six times. Samples were then kept on ice for 2 h and centrifuged at 9,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected, then the pellet was re-extracted under identical conditions. Combined supernatants were subjected to ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS) analysis using an ACQUITY UPLC I-Class (Waters, USA) coupled with a Q-Exactive Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

Statistical analysis

-

The normality of the residuals and the homogeneity of variance were assessed using the UNIVARIATE procedure of SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). No outliers were detected. Data meeting the assumptions of a normal distribution and homogeneity were analyzed by PROC GLIMMIX, with the dietary treatment as a fixed effect and replicate as a random effect. Multiple comparisons were performed by using Tukey's test. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. In addition, linear discriminant analysis (LDA) and quadratic discriminant analysis (QDA) were performed using the LDA and QDA functions of the scikit-learn (v1.3.0) package in Python to evaluate the classification accuracy of growth performance parameters (BW, ADG, ADFI, and F:G) among the dietary treatments and to visualize group separation patterns.

-

The effects of dietary Zn-CS supplementation on the growth performance of pigs are summarized in Table 4. There were no significant differences in initial BW among the treatment groups (p > 0.05). From Day 0 to Day 14, pigs supplemented with 150 or 300 mg/kg Zn-CS showed significantly higher ADG and lower F:G compared with the control and 450 mg/kg groups (p < 0.05), with no difference between the 150 and 300 mg/kg treatments. Although pigs in the 300 mg/kg group reached the highest BW numerically on Day 14, secondary analysis of overall growth (Days 0–28) revealed an inflection point, with 150 mg/kg supplementation providing the most favorable improvement in growth performance. Moreover, no significant differences in final BW were observed among the groups (p > 0.05), but the 150 mg/kg Zn-CS group exhibited the numerically highest value. Collectively, these findings indicate that Zn-CS supplementation at 150 or 300 mg/kg improves ADG and feed efficiency during the early growth phase, but the overall growth response shows an inflection pattern, with 150 mg/kg representing the optimal dose.

Table 4. Effects of dietary Zn-CS supplementation on growth performance.

Items Zn-CS (mg/kg diet) SEM1 p-value Linear Quadratic 0 150 300 450 BW 0 d (kg) 10.20 10.12 10.04 10.10 0.333 > 0.99 0.9 0.92 14 d (kg) 15.95 17.17 17.29 16.04 0.357 0.62 0.93 0.2 28 d (kg) 22.77 24.54 23.67 23.07 0.391 0.72 0.99 0.33 192 d (kg) 105.08 109.15 110.58 101.63 1.79 0.36 0.25 0.56 0–14 d ADG (g) 411b 504ab 518a 424b 27 < 0.01 0.58 < 0.01 ADFI (g) 661 664 683 620 13 0.56 0.47 0.3 F:G 1.61a 1.32b 1.32b 1.47ab 0.069 < 0.01 0.06 < 0.01 14–28 d ADG (g) 487 527 455 502 15 0.23 0.8 0.88 ADFI (g) 870 926 823 877 21 0.59 0.73 0.99 F:G 1.80 1.78 1.81 1.75 0.013 0.98 0.82 0.87 0–28 d ADG (g) 449 515 486 463 15 0.10 0.87 0.03 ADFI (g) 773 804 757 757 11 0.81 0.6 0.69 F:G 1.73 1.57 1.56 1.63 0.039 0.24 0.28 0.08 Means in the same row with different superscript letters differ (p < 0.05, n = 6). BW, body weight; SEM, standard error of the mean; ADFI, average daily feed intake; ADG, average daily gain; F:G, feed-to-gain ratio. Apparent total tract digestibility of nutrients

-

Compared with the control group (Table 5), supplementation with 150 and 300 mg/kg Zn-CS significantly increased the ATTD of DM, CP, EE, Ca, and P (p < 0.05). In contrast, supplementation with 450 mg/kg Zn-CS did not significantly affect the ATTD of these nutrients (p > 0.05). These findings are consistent with the growth performance results and collectively indicate that the beneficial effects of Zn-CS are not dose-dependent.

Table 5. Effects of dietary Zn-CS supplementation apparent total tract digestibility (ATTD, %) of DM, CP, EE, Ca, and P in weaned piglets.

Items Zn-CS (mg/kg diet) SEM p-value 0 150 300 450 DM 82.35c 85.49b 89.44a 81.00c 1.88 < 0.01 CP 75.87c 80.84b 85.64a 74.88c 2.48 < 0.01 EE 82.36b 87.06a 89.14a 80.75b 1.96 < 0.01 Ca 50.76c 63.65b 74.31a 47.93c 6.10 < 0.01 P 59.55c 67.52b 76.27a 57.12c 4.33 < 0.01 Means in the same row with different superscript letters differ (p < 0.05, n = 6). DM, dry matter; CP, crude protein; EE, ether extract; Ca, calcium; P, phosphorus. Small intestinal health index

-

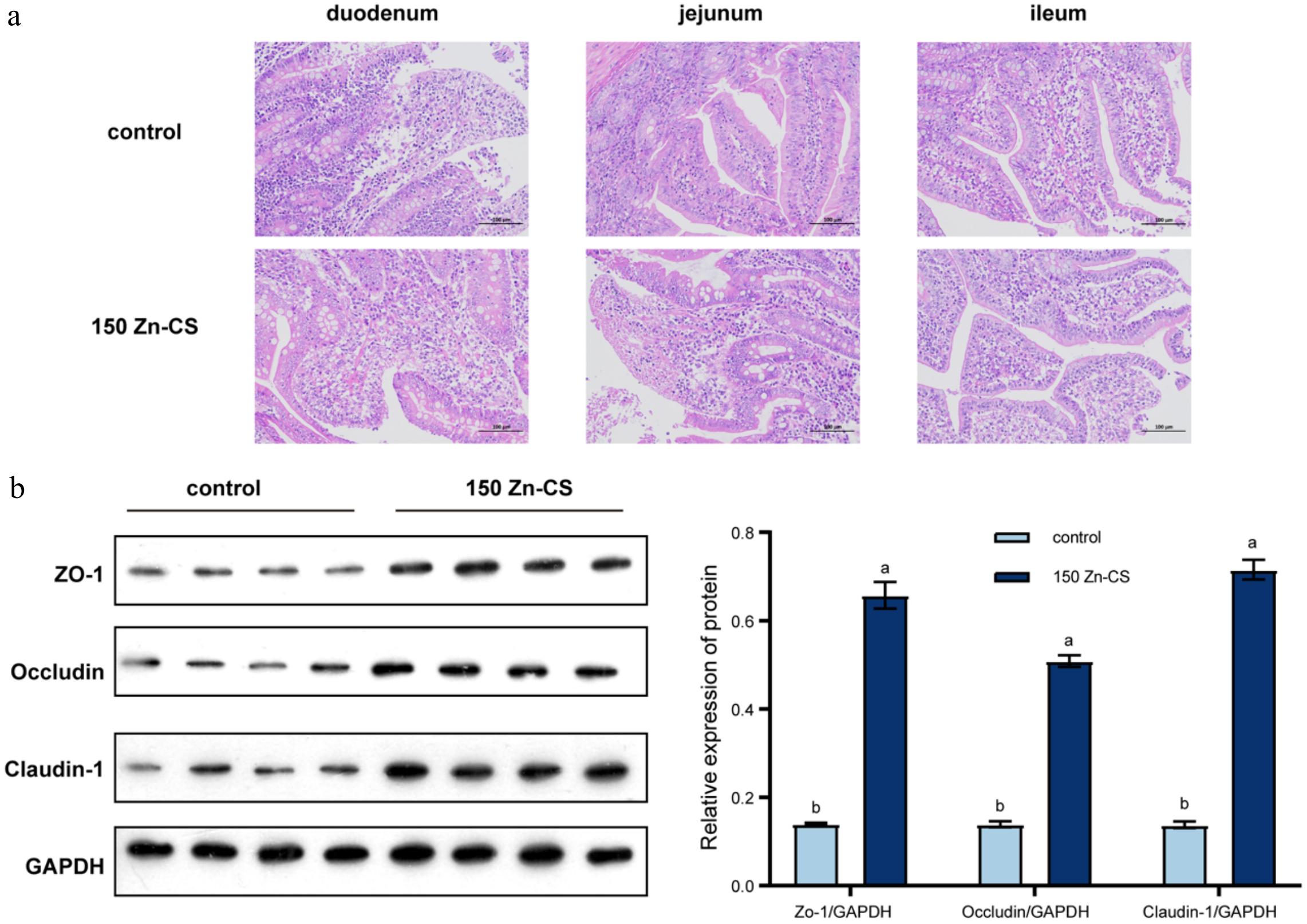

The effects of the graded levels of Zn-CS supplementation on small intestinal health are shown in Fig. 1a and Table 6. In each treatment group, the intestinal villus epithelial cells remained intact, the structure of the lamina propria appeared normal, and no edema or other lesions were observed. There were no significant differences in pathological scores among the groups (p > 0.05).

Figure 1.

Effects of Zn-CS supplementation on small intestinal morphology and the expression of jejunal tight junction proteins. (a) Representative histological images of the jejunum (H&E staining, 200× magnification). (b) The protein expression levels of ZO-1, occludin, and Claudin-1 in the jejunum were detected via Western blot analysis. Data are presented as the means ± SEM (n = 4). Different lowercase letters indicate significantly different values (p < 0.05, by analysis of variance).

Table 6. Effects of dietary Zn-CS supplementation on small intestine health indices (D 28).

Items Zn-CS (mg/kg diet) SEM p-value 0 150 Pathological score Duodenum 2.80 3.00 0.60 0.13 Jejunum 3.17 3.33 0.27 0.55 Ileum 3.17 3.00 0.60 0.79 Villus height (mm) Duodenum 0.46 0.54 0.06 0.27 Jejunum 0.47b 0.58a 0.04 0.01 Ileum 0.35 0.38 0.05 0.52 Crypt depth (mm) Duodenum 0.47 0.44 0.05 0.63 Jejunum 0.37 0.36 0.03 0.85 Ileum 0.24 0.30 0.04 0.10 Villus height/

crypt depthDuodenum 1.03 1.23 0.17 0.27 Jejunum 1.30b 1.73a 0.16 0.02 Ileum 1.49 1.28 0.19 0.27 Means in the same row with different superscript letters differ (p < 0.05, n = 6). As shown in Table 6, dietary supplementation with 150 mg/kg Zn-CS significantly increased jejunal villus height and the villus height-to-crypt depth ratio compared with the control group (p < 0.05).

The jejunum, as the primary site of nutrient absorption, plays a critical role in intestinal health and function. Further analysis of intestinal tight junction proteins demonstrated that Zn-CS supplementation at this level significantly upregulated the expression of ZO-1, Claudin-1, and occludin in the jejunum (p < 0.05, Fig. 1b), indicating an enhancement in intestinal barrier integrity.

Blood indexes

-

Compared with the control group (Table 7), no significant differences were observed in serum glucose, T3, or T4 levels among the treatment groups on Day 14 of the trial (p > 0.05). Similarly, on Day 28, these serum parameters remained statistically unchanged between the control group and the group supplemented with 150 mg/kg Zn-CS, which exhibited the best phenotypic performance (p > 0.05). Nevertheless, pigs in the Zn-CS-supplemented groups exhibited numerically higher serum T3 and T4 levels at both time points, suggesting a potential enhancement of thyroid function without inducing adverse effects such as hyperthyroidism.

Table 7. Effects of dietary Zn-CS supplementation on serum hormone levels.

Items Zn-CS (mg/kg diet) SEM p-value 0 150 300 450 Day 14 Glucose (mmol/L) 5.27 4.90 4.92 5.72 0.19 0.20 T3 (nmol/L) 2.05 2.28 2.13 2.52 0.10 0.52 T4 (nmol/L) 64.17 69.67 68.02 67.13 1.15 0.96 Day 28 Insulin (mU/L) 0.74 1.57 0.41 0.20 Glucose (mmol/L) 6.22 6.58 0.18 0.30 T3 (nmol/L) 2.69 3.00 0.16 0.31 T4 (nmol/L) 91.40 101.40 5.00 0.35 Means in the same row with different superscript letters differ (p < 0.05, n = 6). T3, tri-iodothyronine; T4, thyroxine. Small intestinal, liver, and kidney morphological characteristics

-

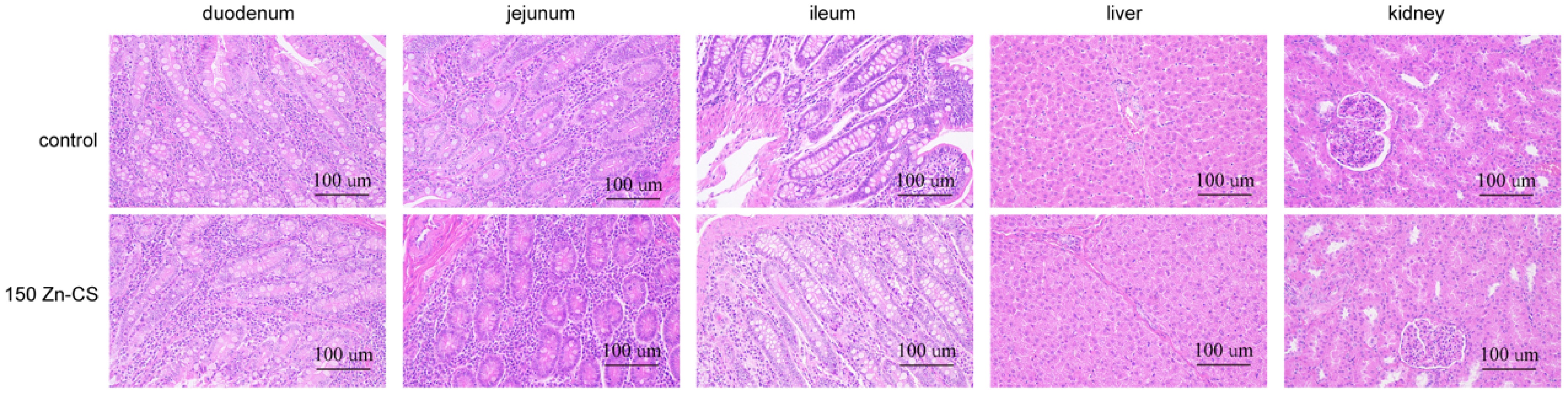

To assess the long-term safety of Zn-CS supplementation, histological examinations were conducted on the small intestine, liver, and kidneys of finishing pigs at the end of the trial (Day 192, BW > 100 kg). The results revealed that the intestinal villus epithelial cells in all treatment groups remained intact, with no signs of necrosis, shedding, or inflammatory cell infiltration. The structure of the lamina propria was normal, and no edema or other lesions were observed; the overall tissue morphology appeared to be normal, with no evident pathological changes (Fig. 2). Furthermore, dietary supplementation with 150 mg/kg Zn-CS tended to increase duodenal crypt depth (p < 0.1) and significantly increased ileal crypt depth (p < 0.05) compared with the control group, suggesting enhanced intestinal tissue renewal and reparative capacity (Table 8).

Figure 2.

Representative histological images of the small intestine, liver, and kidney with H&E staining (magnification: 200×).

Table 8. Effects of dietary Zn-CS supplementation on villus height and crypt depth in the small intestine of finished pigs.

Items Zn-CS (mg/kg diet) SEM p-value 0 150 Villus height (μm) Duodenum 830.3 839.6 137.6 >0.99 Jejunum 607.3 594.1 97.92 0.89 Ileum 607.3 597.4 95.66 0.92 Crypt depth (μm) Duodenum 724.1 605 57.86 0.06 Jejunum 547.0 488.8 69.86 0.42 Ileum 547.0a 370.9b 55.62 0.01 Villus height/

crypt depthDuodenum 1.19 1.39 0.21 0.37 Jejunum 1.29 1.32 0.44 0.94 Ileum 1.29 1.65 0.42 0.40 Means in the same row with different superscript letters differ (p < 0.05, n = 6). In the liver, the hepatic lobule structure was clear, the hepatic cords were arranged regularly, and the hepatocytes exhibited abundant cytoplasm and a normal morphology. The hepatic sinusoids were evenly spaced without obvious dilation or compression, and no pathological abnormalities were detected (Fig. 2).

In the kidney, a clear distinction was observed between the renal cortex and medulla. Renal tubular epithelial cells were morphologically normal and tightly arranged (Fig. 2). Overall, no histopathological abnormalities were found in any of the examined organs. Combined with the growth performance results, these findings suggest that long-term dietary supplementation with Zn-CS does not induce toxic side effects.

Carcass and meat quality

-

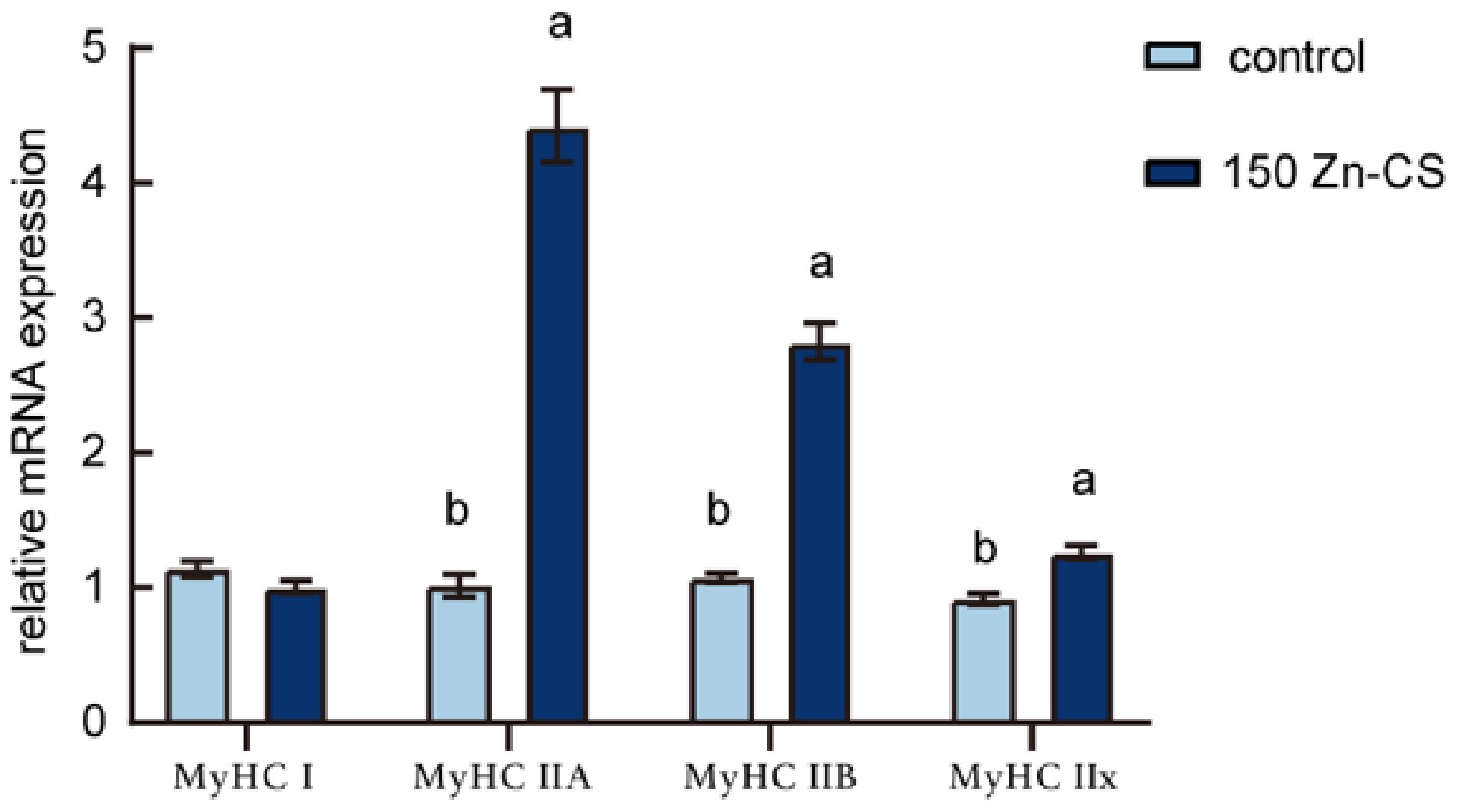

The effects of dietary supplementation with 150 mg/kg Zn-CS on the expression of muscle fiber typesin weaned piglets are presented in Fig. 3. Compared with the control group, the Zn-CS-supplemented group showed significantly increased expression levels of all three fast-twitch (Type II) muscle fiber types (p < 0.05). As the early postweaning period represents a critical window for the transformation of muscle fiber types in piglets, and the number of muscle fibers is closely associated with the potential for muscle growth, these findings suggest that Zn-CS supplementation may enhance muscle development and contribute to improved meat quality.

Figure 3.

Effects of Zn-CS supplementation on the mRNA expression of muscle fiber-related genes. Data are the means ± SEM (n = 6). Different lowercase letters indicate significantly different values (p < 0.05, by analysis of variance).

Carcass and meat quality parameters were assessed when the pigs reached a market weight of 100 kg (Table 9). Compared with the control group, pigs receiving 150 mg/kg Zn-CS exhibited significantly higher hot carcass weight, straight carcass length, and diagonal carcass length (p < 0.05). Moreover, Zn-CS supplementation significantly increased muscle pH at 24 h postmortem (p < 0.05), indicating improved regulation of postmortem acidification and potential enhancement of meat quality.

Table 9. Effects of dietary Zn-CS supplementation on the carcass traits and meat quality of finished pigs.

Items Zn-CS (mg/kg diet) SEM p-value 0 150 Carcass weight (kg) 74.93 92.57 8.82 < 0.01 Dressing percentage (%) 71.38 71.73 0.18 0.78 Straight carcass length (cm) 77.67 83.83 3.08 < 0.01 Diagonal carcass length (cm) 74.50 80.33 2.92 < 0.01 Longissimus dorsi length (cm) 102.02 98.74 1.64 0.68 Longissimus dorsi width (cm) 38.12 41.84 1.86 0.14 Loin eye area (cm2) 27.15 28.94 0.90 0.50 Deltoid muscle length (cm) 91.37 91.36 < 0.01 0.99 Deltoid muscle width (cm) 20.13 17.86 1.13 0.43 Back fat depth (mm) Shoulder fat thickness 41.44 42.77 0.66 0.56 Last rib fat thickness 25.73 26.95 0.61 0.71 Lumbosacral fat thickness 18.83 18.81 0.01 0.99 pH3h 6.08 5.87 0.10 0.35 pH24h 5.93 6.12 0.10 < 0.01 Flesh color score 74.43 78.18 1.88 0.30 Drip loss (%) 4.13 4.01 0.06 0.76 Shear force (N) 54.89 64.10 4.60 0.34 Means in the same row with different superscript letters differ (p < 0.05, n = 6). Indicators with significant differences are displayed in bold. Free amino acid profiles in the longissimus dorsi muscle of finished pigs

-

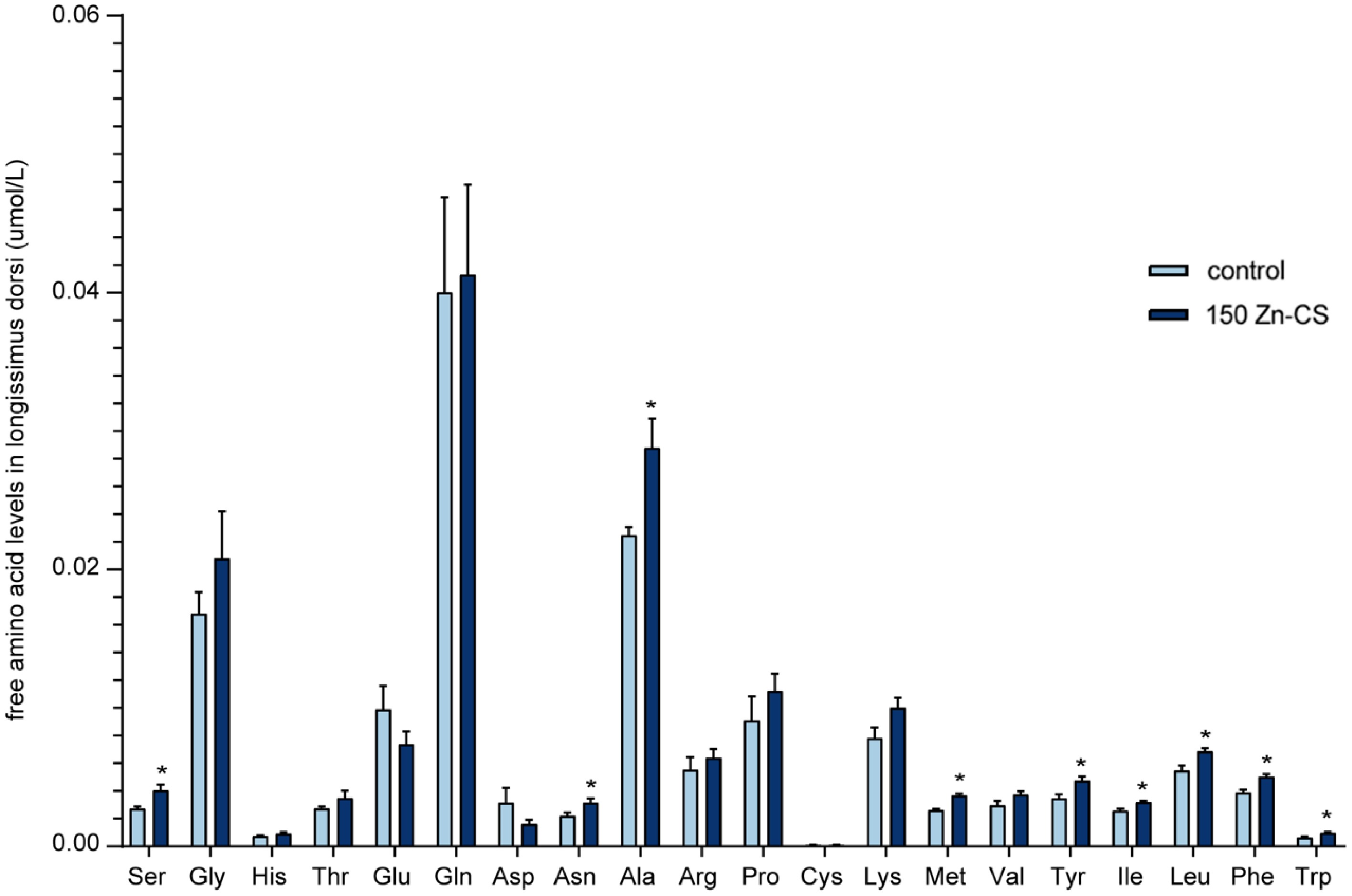

As shown in Figure 4, dietary supplementation with 150 mg/kg Zn-CS significantly increased the concentrations of nine individual free amino acids in the longissimus dorsi muscle, including serine, asparagine, alanine, methionine, tyrosine, isoleucine, leucine, phenylalanine, and tryptophan (p < 0.05). Despite these increases in specific amino acids, the total free amino acid content did not differ significantly between groups, suggesting that Zn-CS may selectively promote the accumulation or metabolic retention of certain amino acids without affecting the overall amino acid pool. Among these, aspartic acid is recognized as an important precursor of umami taste, whereas serine and alanine both contribute to the perception of sweetness.

Figure 4.

Effects of Zn-CS supplementation on free amino acid concentrations in longissimus dorsi muscles. Data are the means (n = 6; *, p < 0.05, by analysis of variance). Ser, serine; Gly, glycine; His, histidine; Thr, threonine; Glu, glutamic acid; Gln, glutamine; Asp, aspartic acid; Asn, asparagine; Ala, alanine; Arg, arginine; Pro, proline; Cys, cysteine; Lys, lysine; Met, methionine; Val, valine; Tyr, tyrosine; Ile, isoleucine; Leu, leucine; Phe, phenylalanine; Trp, tryptophan.

-

With the growing demand for animal protein, enhancing growth performance in pigs has become a key objective in livestock research. Cysteamine (CS), a nonhormonal regulator, has been used as a feed additive in swine to improve growth, feed efficiency, protein deposition, and reproductive traits[15]. It also exerts antioxidant, gut-protective, and immunomodulatory effects[16,17]. However, its poor palatability, strong odor, and risk of gastrointestinal damage at high doses limit its application[10,11]. Chelating CS with Zn improves its stability and bioavailability while combining the metabolic benefits of CS with the catalytic and structural roles of zinc[12,18], making Zn-CS a promising alternative additive.

The present study investigated the effects of dietary supplementation with Zn-CS at different levels on the growth performance, nutrient digestibility, intestinal morphology, systemic health indicators, and carcass traits in pigs from weaning to market weight. The results demonstrated that Zn-CS at 150–300 mg/kg improved early growth performance, enhanced nutrient digestibility, maintained intestinal and systemic health, and positively influenced carcass characteristics, supporting its potential as an effective feed additive.

Improved ADG and reduced F:G observed during the early growth phase (Days 0–14) in the 150 and 300 mg/kg Zn-CS groups suggest that Zn-CS can enhance feed efficiency in weaned piglets. These results are consistent with previous findings that Zn and CS individually support growth through their roles in protein synthesis, endocrine regulation, and antioxidant defense[19−22]. The absence of further benefits at 450 mg/kg in our study suggests a plateau in the response, possibly caused by saturation of the metabolic pathways or negative feedback regulation, consistent with observations in trace mineral supplementation studies[23,24].

The improvements in the ATTD of DM, CP, EE, Ca, and P in the 150 and 300 mg/kg groups are likely attributable to the synergistic effects of Zn-CS on digestive function and nutrient metabolism. Zn plays a key role in maintaining mucosal integrity and enzyme activity, whereas cysteamine has been shown to stimulate the secretion of growth hormones and digestive enzymes[25,26]. Enhanced jejunal villus height and villus height-to-crypt depth ratio in the 150 mg/kg group further support the notion that Zn-CS promotes intestinal absorptive capacity. Moreover, the upregulation of the tight junction proteins ZO-1, Claudin-1, and occludin suggests that Zn-CS contributes to improved gut barrier function, which is critical for nutrient absorption and protection against enteric pathogens.

Serum biochemical analyses showed no significant differences in glucose, T3, or T4 levels among the treatment groups; however, the numerical increase in T3 and T4 concentrations in the Zn-CS groups implies a potential stimulatory effect on thyroid function. This aligns with the known role of CS in modulating the hypothalamic–pituitary axis[25]. Importantly, these hormonal changes occurred without signs of hyperthyroidism or other adverse effects, indicating that Zn-CS may enhance endocrine activity in a controlled and safe manner.

In terms of safety, dietary supplementation with Zn-CS for a duration of 192 days did not elicit any adverse effects on growth performance in pigs. Histological examinations of the small intestine, liver, and kidney revealed no pathological alterations, further confirming the long-term safety of Zn-CS at inclusion levels up to 150 mg/kg. This contrasts with high-dose ZnO and CS, which have been associated with epithelial damage and increased oxidative stress[10,27]. Additionally, the increased crypt depth observed in the duodenum and ileum of pigs receiving Zn-CS may indicate enhanced mucosal turnover and regenerative capacity. Such morphological adaptations are likely beneficial for maintaining intestinal homeostasis and structural integrity during periods of rapid growth.

In addition to promoting growth performance and gut health, dietary Zn-CS supplementation enhanced the expression of fast-twitch muscle fibers and improved carcass traits, such as hot carcass weight and carcass length. The lactation period is recognized as a critical window for the remodeling of muscle fiber types, a process that is essential for maintaining energy homeostasis, mitigating fatigue, and optimizing meat quality in livestock. Given that slow-twitch fibers have smaller diameters, a higher proportion of fast-twitch fibers indicates larger fiber size and thus greater capacity for muscle hypertrophy[28]. Since total muscle fiber number is a key determinant of muscle growth potential, the observed shift toward teh expression of fast-twitch fibers suggests that Zn-CS may promote muscle development and enhance meat quality in pigs.

Additionally, Zn-CS supplementation selectively increased the concentrations of several functional free amino acids, which serve not only as essential substrates for muscle protein synthesis but also contribute to the key sensory properties of pork, such as flavor and umami intensity. While hydrolyzed amino acids mainly reflect the nutritional value of meat, free amino acids are more directly linked to flavor formation; therefore, profiling free amino acids is particularly important for evaluating the flavor characteristics of Dongliao Black pig, a breed renowned for its superior meat quality. Among these, leucine and isoleucine are recognized for their ability to stimulate protein synthesis and regulate energy metabolism[29]. Methionine plays an important role in enhancing antioxidative capacity[30]. Furthermore, both leucine and methionine have been shown to influence the conversion of muscle fiber type by promoting the formation of fast-twitch fibers[31,32]. The elevated concentrations of these amino acids in the 150 mg/kg Zn-CS group may help explain the increased expression of fast-twitch muscle fibers, indicating a potential connection between amino acid availability and muscle fiber remodeling. Notably, Zn-CS did not alter the levels of bitter-tasting amino acids such as lysine, arginine, histidine, and valine[33], suggesting that the improvement in muscle quality was achieved without compromising the meat's palatability. Collectively, these results suggest that Zn-CS supplementation not only modulates amino acid metabolism but also holds potential for improving the flavor attributes of Dongliao Black pig meat, thereby adding value to its characteristic meat quality.

Moreover, a rapid decline in postmortem muscle pH can lead to increased muscle temperature and protein denaturation; therefore, maintaining a higher pH postmortem is crucial for preserving the quality attributes of fresh pork and processed meat products[34]. The significantly higher postmortem muscle pH observed in the 150 mg/kg group further supports the beneficial effect of Zn-CS on meat quality.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate that dietary Zn-CS at 150 mg/kg can serve as an effective strategy to promote growth, improve digestive and intestinal function, support endocrine balance, and enhance meat quality in pigs. Given the environmental and regulatory concerns associated with traditional high-dose ZnO supplementation, Zn-CS represents a promising alternative with both functional and sustainable advantages. It is worth noting, however, that precise nutritional requirements for indigenous pig breeds such as black pigs have not yet been well established. Therefore, it is possible that Zn-CS may exert even more pronounced benefits when incorporated into more optimized dietary formulations tailored to the specific needs of these breeds. Further research is warranted to elucidate the precise mechanisms of action and to evaluate its application under commercial production settings.

-

In summary, dietary supplementation with Zn-CS at 150 mg/kg improved early growth performance, enhanced nutrient digestibility, promoted intestinal development and barrier integrity, and supported endocrine and systemic health in pigs from weaning to finishing. Notably, Zn-CS supplementation also improved carcass traits, several functional free amino acids, and muscle fiber characteristics, indicating potential benefits for meat quality. No adverse effects on the major organs were observed, supporting the safety of long-term use. These findings suggest that Zn-CS is a safe and effective alternative to conventional zinc sources and CS, with the potential to enhance productivity and meat quality in modern swine production.

-

All procedures were reviewed and preapproved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Jilin University (identification number: SY202505022; approval date: 01/12/2025). The research followed the "replacement, reduction, and refinement" principles to minimize harm to animals. This article provides details on the housing conditions, care, and pain management for the animals, ensuring that the impact on the animals was minimized during the experiment.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: resources: Liang S; conceptualization: Liang S, Shang L; investigation: Xiang D, Qu H, Pan H, Pan H; data curation: Xiang D; writing – original draft: Zhou H; formal analysis: Qu H; validation: Pan H; visualization: Zhang S; supervision: Shang L; writing – review and editing: Shang L, Zhang Y, Zhang G, Chen M. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

This study was supported by the State Key Laboratory of Animal Nutrition and Feeding (2004DA125184H2517).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Shuang Liang, Dao Xiang

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Liang S, Xiang D, Zhang Y, Zhang G, Chen M, et al. 2026. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of cysteamine-chelated zinc in weaned-to-finished pigs. Animal Advances 3: e010 doi: 10.48130/animadv-0025-0047

Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of cysteamine-chelated zinc in weaned-to-finished pigs

- Received: 29 September 2025

- Revised: 28 October 2025

- Accepted: 30 October 2025

- Published online: 12 February 2026

Abstract: This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of dietary cysteamine-chelated zinc (Zn-CS) supplementation in weaned-to-finished pigs. In total, 144 weaned piglets (45 days old, 10.12 ± 0.03 kg) were randomly assigned to four dietary treatments: A basal diet or the basal diet supplemented with 150, 300, or 450 mg/kg Zn-CS. Supplementation with 150 or 300 mg/kg Zn-CS significantly improved the average daily gain and apparent total tract digestibility of several indexes (p < 0.05), and reduced the feed-to-gain ratio (p < 0.05). Although pigs receiving 300 mg/kg showed the highest body weight numerically on Day 14, secondary analysis of overall growth (Days 0–28) indicated an inflection point, with 150 mg/kg producing the optimal improvement. Moreover, histological examination revealed intact intestinal structures across groups; notably, 150 mg/kg Zn-CS significantly increased jejunal villus height, villus height-to-crypt depth ratio, and the expression of tight junction proteins (p < 0.05), reflecting enhanced intestinal barrier integrity. Unlike traditional high-dose ZnO and cysteamine, which may cause epithelial damage or organ toxicity, long-term Zn-CS supplementation showed no pathological effects on the small intestine, liver, or kidney (p > 0.05), confirming its safety. Furthermore, Zn-CS supplementation promoted fast-twitch muscle fiber expression and improved carcass traits, including hot carcass weight and carcass length, along with a higher pH at 24 h postmortem (p < 0.05), suggesting benefits for muscle growth and meat quality. Collectively, these results demonstrate that dietary Zn-CS at 150 mg/kg is a safe and effective strategy to enhance growth performance, nutrient absorption, intestinal health, and meat quality in pigs.

-

Key words:

- Cysteamine-chelated zinc /

- Safety /

- Growth performance /

- Nutrient digestibility /

- Meat quality