-

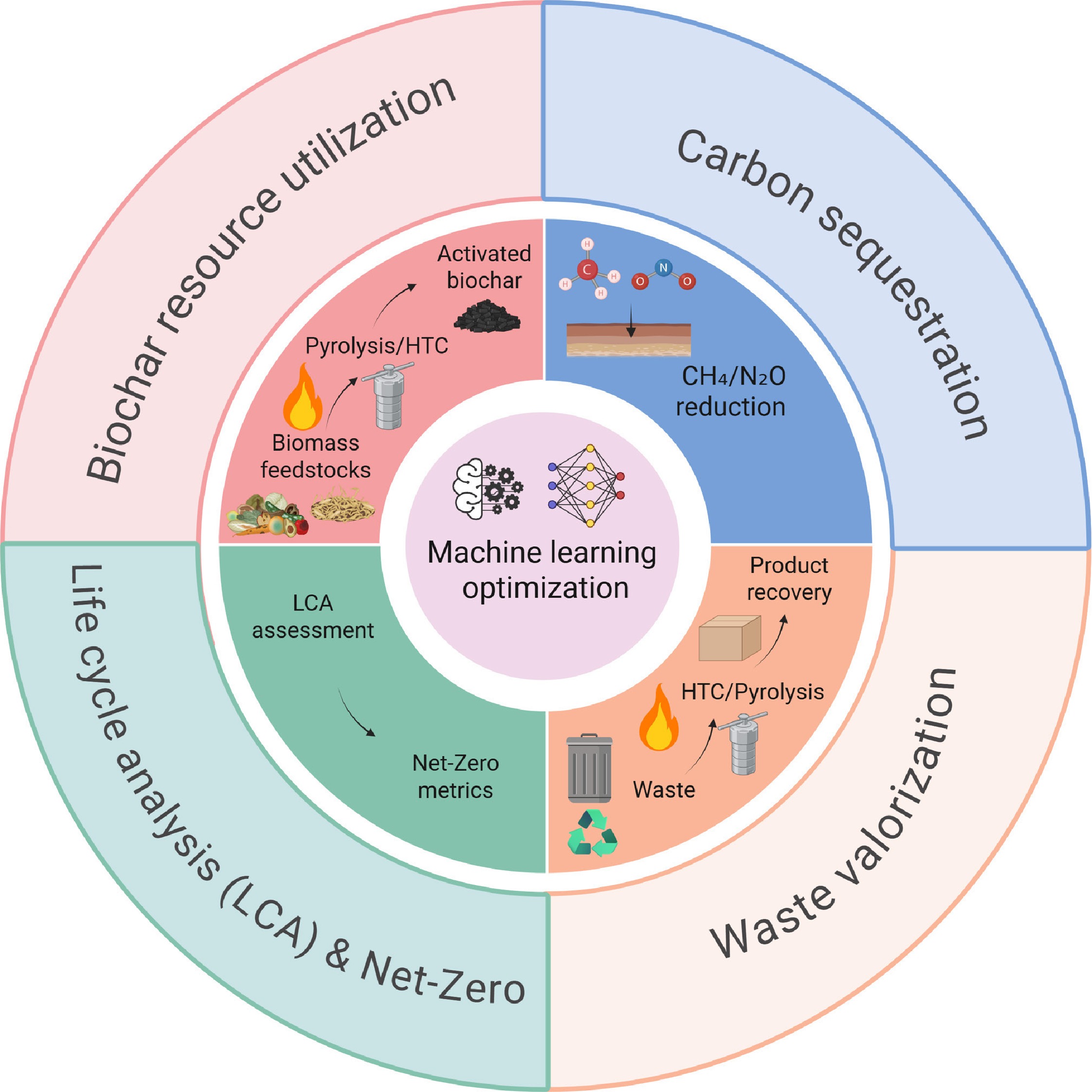

With the escalating challenges of global climate change and the overexploitation of natural resources, the search for sustainable carbon reduction solutions has become one of the most pressing issues facing the international community[1]. Traditional carbon reduction approaches such as Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) are capable of mitigating greenhouse gas emissions to some extent, yet they face challenges including high costs, significant technical complexities, and uncertainties associated with long-term storage safety and scalability[2,3]. Consequently, a growing number of researchers are shifting focus toward Nature-based Solutions (NbS), particularly through the rational utilization of organic waste resources to achieve the dual objectives of greenhouse gas mitigation and environmental remediation[4−8].

Biochar, as a significant natural carbon sink material, has garnered widespread attention due to its unique structure and multifunctional properties[9,10]. Biochar is a black solid material produced through the pyrolysis of organic waste (such as agricultural and forestry residues, municipal solid waste, etc) under oxygen-limited conditions, which converts organic matter into stable carbon[11,12]. The main characteristics of biochar include its ability to sequester carbon over the long term, improve soil quality, enhance water and nutrient retention, and reduce greenhouse gas emissions such as carbon dioxide and methane[13]. These multifunctional properties have led to its widespread application across various fields, including agricultural soil enhancement, wastewater treatment, pollution remediation, and energy production[14].

Despite its significant environmental benefits and economic potential, the practical application of biochar faces several challenges[15]. For example, the production efficiency, product performance, and environmental impacts of biochar vary significantly depending on the feedstock types, production conditions, and application methods[16]. Conventional biochar production and application technologies often rely on empirical knowledge and iterative experimentation, resulting in suboptimal resource utilization efficiency, while the carbon footprint and environmental impacts of production processes have not been systematically optimized[12]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to adopt more scientific and precise approaches to enhance the performance and application efficacy of biochar, thereby facilitating its widespread adoption in climate change mitigation and sustainable agricultural development[17].

With the rapid advancement of data science and artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, machine learning (ML) has emerged as a robust tool for data analysis and process optimization[18], increasingly recognized as a critical enabler for enhancing the functionality and performance of biochar systems[19]. ML can help researchers identify the underlying patterns and relationships through the analysis of large amounts of experimental data, enabling intelligent optimization of biochar production processes[20,21]. In the research and development of biochar, ML not only accelerates the screening of material characteristics and performance but also optimizes production conditions and feedstock selection through predictive models, further enhancing its carbon sequestration efficiency, and soil remediation capabilities[22]. Furthermore, ML can establish precise predictive models linking biochar to its environmental impacts, thereby providing policymakers with scientific evidence to optimize biochar application strategies under diverse environmental conditions[23,24].

Driven by cutting-edge technologies such as self-supervised learning, federated learning, and multiscale modeling, the research, development, and application of biochar are advancing in increasingly intelligent and precise directions[25,26]. Self-supervised learning facilitates the optimization of biochar production parameters by automatically generating labels and enhancing learning efficiency[27]; federated learning enables data sharing and collaboration among research institutions while preserving data privacy, thereby enhancing model accuracy and adaptability[28]; and multiscale modeling, by accounting for factors across multiple scales from microscopic to macroscopic, enables comprehensive analysis of biochar's behavior and efficacy, thereby providing theoretical support for its cross-domain applications[29].

This paper aims to systematically review the latest research advancements in multifunctional optimization and carbon footprint reduction of biochar, with a focused discussion on how machine learning technologies enhance the resource utilization and environmental benefits of biochar. First, we will revisit the fundamental properties and application areas of biochar, and elaborate on the applications of machine learning in biochar performance optimization, intelligent control of production processes, and carbon emission reduction assessment. Next, the paper will analyze the application potential and challenges of various machine learning algorithms—such as supervised learning, self-supervised learning, deep learning, and reinforcement learning—in biochar research and development. Finally, we will outline future trends in biochar research and technological development, propose sustainable development pathways for the multifunctionality and intelligent optimization of biochar materials driven by machine learning, and discuss the technical, data-related, and policy challenges in achieving these goals.

-

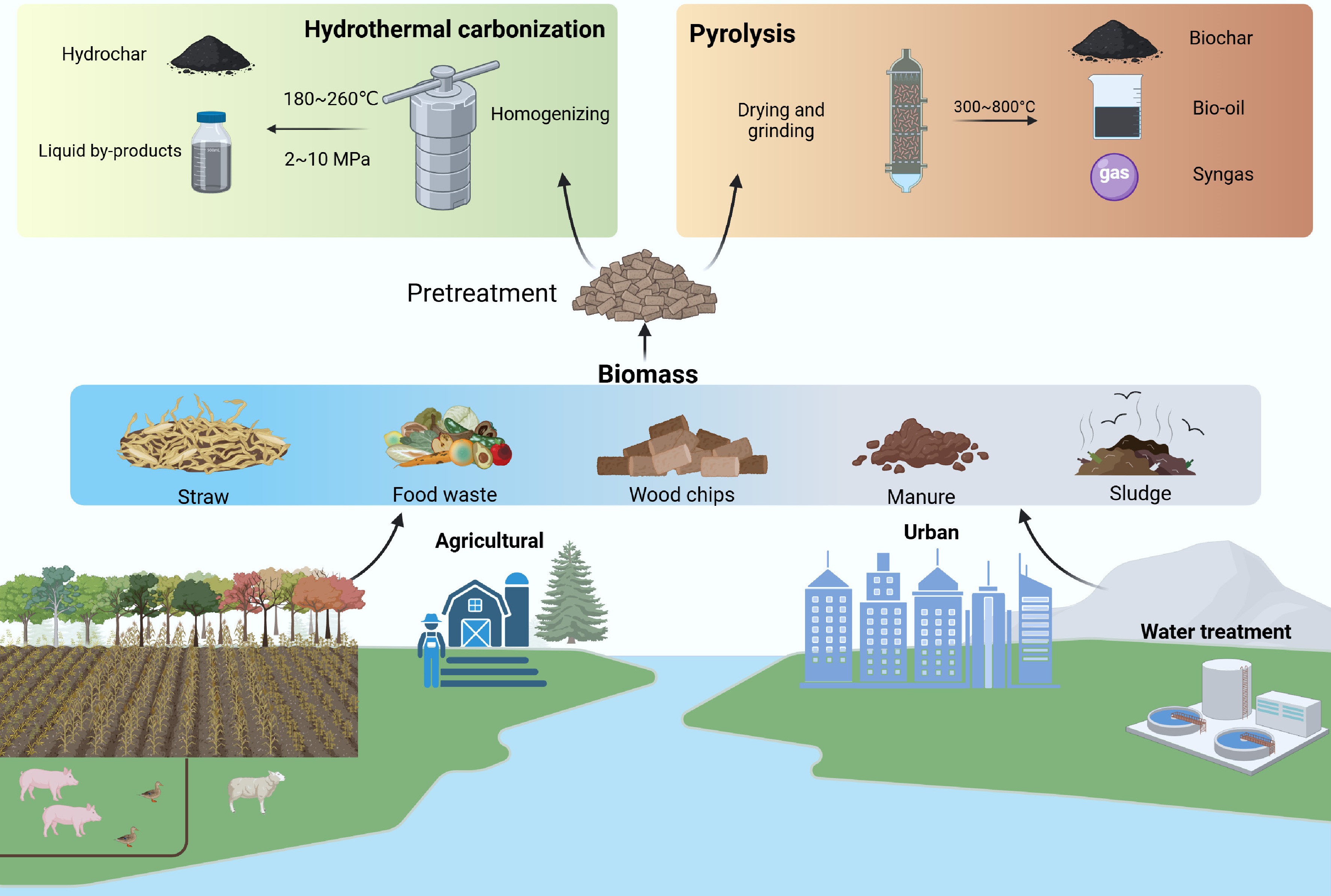

Biochar is a carbonaceous porous solid material produced through thermochemical conversion methods such as pyrolysis and hydrothermal carbonization (HTC) under oxygen-limited or anaerobic conditions, using biomass feedstocks including agricultural waste, forestry residues, sludge, and food waste[30−33]. As summarized in Table 1 regarding feedstock-property correlations, biochar derived from different raw materials exhibits significant variations in key parameters such as specific surface area, pore structure, and surface functional groups. Distinct from conventional charcoal, biochar typically possesses a highly aromatic carbon matrix, which confers long-term environmental stability. The production of biochar not only aids in reducing organic waste accumulation but also mitigates climate change through carbon sequestration, while simultaneously enhancing soil fertility and promoting sustainable resource utilization[34,35]. The specific properties of biochar are influenced by multiple factors, including the type of biomass feedstock, pretreatment methods, pyrolysis temperature, heating rate, and reaction atmosphere. The combined effects of these factors ultimately result in significant variations in the physicochemical characteristics of biochar produced under different conditions[36].

Table 1. Effects of different raw materials on biochar properties

Feedstock type Carbon content Ash content Surface area

(m2/g)Pore size

(nm)pH Porosity CEC

(cmol/kg)Bulk density

(g/cm3)Ref. Wood 75%−85% 2%−5% 300−600 2−10 7−9 65%−75% 15−40 0.25−0.40 [37−41] Crop residues 60%−75% 5%−15% 100−400 5−20 6−8 55%−65% 20−30 0.30−0.50 [38−44] Sludge 30%−50% 20%−40% 50−200 10−50 5−7 40%−55% 4−35 0.45−1.50 [38,45−48] Food waste 40%−60% 10%−30% 50−150 15−40 4−6 50%−65% 15−25 0.35−0.60 [49−55] Animal manure 35%−55% 25%−45% 80−250 5−30 7−10 45%−60% 15−140 0.30−0.50 [48,56−59] The preparation methods of biochar mainly include pyrolysis and hydrothermal carbonization, each of which has distinct reaction mechanisms and application advantages[39]. Pyrolysis is currently the most common method for biochar preparation. Under oxygen-limited conditions, biomass is heated to 300–800 °C to undergo thermal decomposition, generating biochar, gases (such as syngas), and bio-oil[60]. Based on the heating rate and temperature, pyrolysis can be classified into slow pyrolysis and fast pyrolysis. Slow pyrolysis, characterized by a lower heating rate (< 10 °C/min) and longer residence time, enhances biochar yield and improves its carbon sequestration capacity. In contrast, fast pyrolysis employs a higher heating rate (> 100 °C/min) and is primarily used for bio-oil production, resulting in lower biochar yield[61]. In recent years, some improved pyrolysis technologies (such as atmosphere-regulated pyrolysis, catalytic pyrolysis, etc.) have been developed to optimize the pore structure, surface chemical functional groups, and adsorption properties of biochar[62]. The process characteristics and performance comparison of the two preparation methods are shown in Fig. 1 and Table 2, facilitating a more systematic understanding of their applicable scenarios and potential value.

Hydrothermal Carbonization (HTC) serves as another crucial method for biochar preparation, particularly suitable for high-moisture-content biomass such as sewage sludge, food waste, and crop residues[63−65]. Under sealed high-pressure conditions (180–250 °C), biomass undergoes hydrolysis, dehydration, condensation, and other reactions in the aqueous phase, ultimately forming carbon-rich solids (HTC biochar) and liquid by-products[66−71]. Since the HTC process occurs at relatively low temperatures, the resulting biochar has a lower degree of aromatization but contains more polar functional groups (e.g., carboxyl and hydroxyl groups), enabling it to exhibit higher activity in pollutant adsorption and catalytic degradation[72]. In addition, HTC biochar typically has a higher oxygen content and lower ash content, which gives it broad application potential in environmental remediation, water pollution control, and energy storage[73]. In the future, by combining nanotechnology, activation modification, and other technical approaches, the microstructure and functional properties of biochar can be further optimized to meet the application demands across diverse fields.

Table 2. Two methods of biochar preparation

Parameter Pyrolysis Hydrothermal carbonization Ref. Temperature range 300–800 °C 180–250 °C [74−76] Reaction environment Oxygen-limited or anaerobic High-temperature, high-pressure water [60,76] Main products Biochar, syngas, bio-oil Hydrochar, liquid by-products [60,76] By-products Gases (CO2, H2, CH4), tar Soluble organic compounds, acidic substances [34,77] Biochar properties High carbon content, stable structure, highly porous High carbon content, stable structure, highly porous [78] Suitable feedstock Woody biomass, agricultural waste, sludge High-moisture biomass (food waste, sewage sludge, animal wastes) [66,79] Advantages High carbon sequestration efficiency, stable biochar Suitable for wet biomass, no drying needed, rich in functional groups [63,66,67,80] Disadvantages Requires high temperatures, energy-intensive Lower carbon sequestration, less stable biochar [63,80] The preparation methods of biochar directly affects its surface structure, functional groups, specific surface area, and other properties[81]. The biochar prepared by pyrolysis typically possesses higher carbon content and a larger specific surface area, whereas biochar produced through hydrothermal carbonization exhibits stronger hydrophilicity and more oxygen-containing functional groups, rendering it suitable for functional applications such as environmental remediation[82,83].

Structural properties of biochar

-

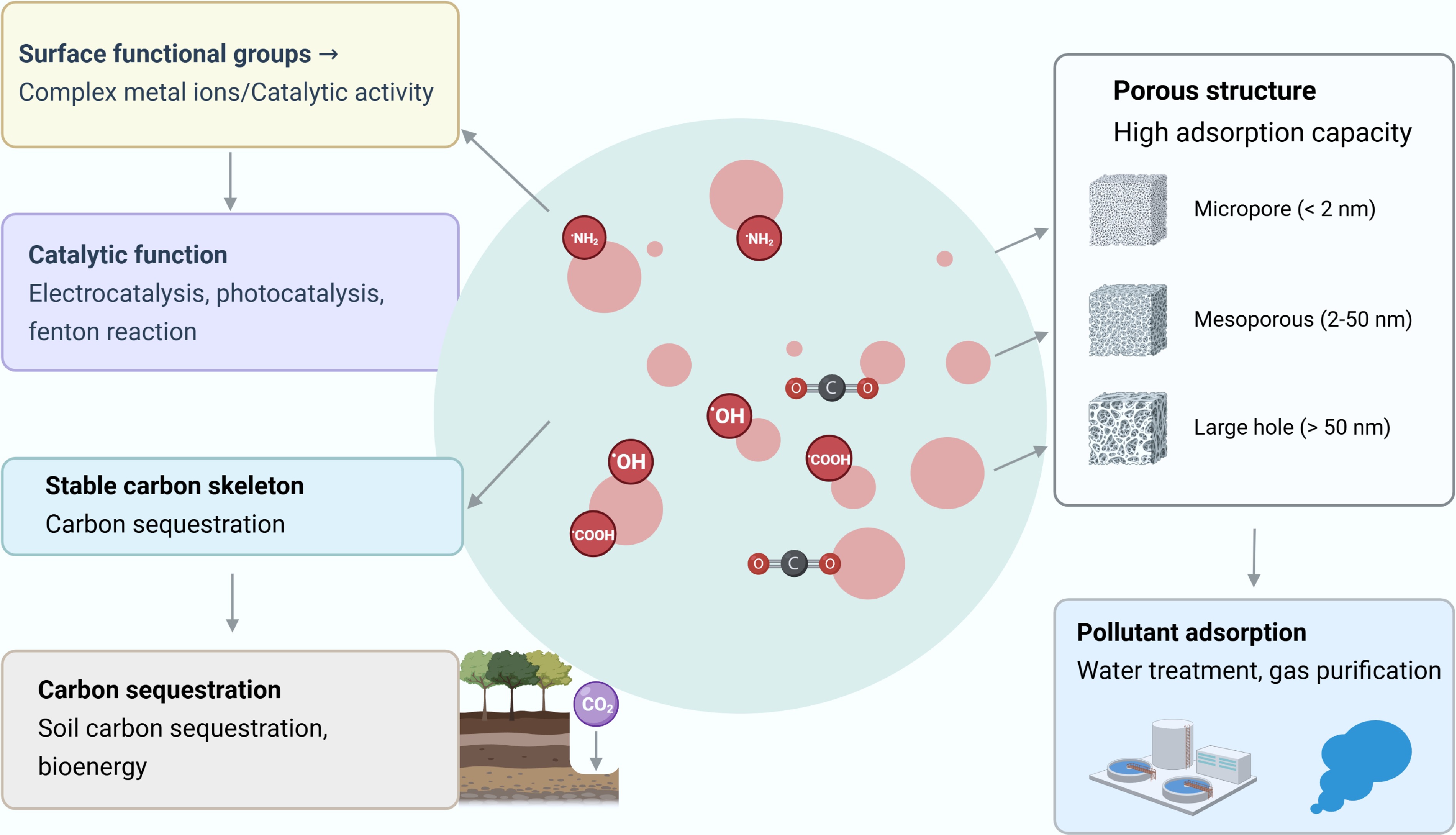

The structural characteristics of biochar are fundamental determinants of its performance and application[84]. Specific surface area, pore structure, surface functional groups, and elemental composition directly govern its effectiveness in soil amelioration, pollutant adsorption, and carbon sequestration[56,85].

The microstructure of biochar is primarily characterized by a highly developed pore system, endowing it with a large specific surface area and high adsorption capacity, as illustrated in Fig. 2. This pore structure is jointly determined by the cell walls of the raw materials and the cracks formed during the pyrolysis process; moreover, higher pyrolysis temperatures generally lead to better pore development[86,87]. In addition, the surface of biochar is typically rich in various oxygen-containing functional groups (such as hydroxyl, carboxyl, carbonyl, and phenolic hydroxyl groups), which not only enhance the interactions between biochar and pollutants but also determine its hydrophilicity, ion exchange capacity, and catalytic activity. Owing to these properties, biochar exhibits significant application potential in fields such as water pollution control, soil remediation, air purification, and energy storage. For instance, in water treatment processes, biochar can remove heavy metals, antibiotics, pesticide residues, and organic pollutants through mechanisms like physical adsorption, electrostatic interactions, and complexation[61].

In terms of chemical composition, biochar primarily consists of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), oxygen (O), nitrogen (N), and certain inorganic minerals. The specific content of these elements depends on the feedstock composition and production process[33,88]. Generally, as the pyrolysis temperature increases, the C content in biochar increases, while the contents of H and O decrease, leading to a higher degree of aromaticity and enhanced thermal stability, along with a reduction in polar functional groups. Biochars produced at lower pyrolysis temperatures retain more O-containing functional groups, making them suitable for soil improvement and pollutant adsorption. In contrast, high-temperature biochars, due to their higher crystallinity and stability, are more appropriate for C sequestration and energy storage applications[89]. Additionally, some biochars are rich in mineral elements such as potassium (K), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), and phosphorus (P), which can serve as soil amendments to enhance nutrient availability. In recent years, researchers have further optimized biochar performance through methods such as metal doping, oxidation, and acid-base modification, expanding its applications in catalysis, energy storage, and environmental remediation[90,91].

Functionalization and composite strategies

-

To further enhance the functionality of biochar, researchers have developed various functionalization and composite strategies[92−95]. These strategies not only enhance the adsorption performance, catalytic capacity, and water purification efficiency of biochar but also confer additional functionalities related to environmental remediation and energy utilization[94,96].

Functionalization refers to the introduction of specific functional groups or the alteration of pore structure on the surface of biochar through chemical modification or physical treatment methods, to improve its performance[96]. Common functionalization methods include acid-based treatment, redox reactions, and high-temperature plasma treatment, as shown in Table 3. For example, acid treatment can introduce more carboxyl functional groups on the surface of biochar, enhancing its adsorption capacity for metal ions and organic pollutants; while alkali treatment helps increase the alkalinity of biochar, thereby improving its adsorption effect on acidic pollutants[97]. Oxidation treatment can introduce oxidative functional groups (such as carboxyl and hydroxyl groups), further enhancing the water solubility and ion exchange capacity of biochar[98].

Table 3. Effects of different biochar modification methods on its properties

Modification method Change in surface area Functional group changes Application field Ref. CO2 activation 50%–100% Increased carboxyl, phenol groups Water pollution treatment [99,100] Fe3+ doping 20%–60% Increased catalytic active sites Catalytic degradation of pollutants [92] Sulfonation 10%–40% Increased SO3H groups Acidic catalysis [101−103] KOH activation 80%–150% Enhanced hydroxyl, carbonyl groups CO2 capture, energy storage [104,105] N-doping 20%–80% Introduced amine, pyridinic-N Electrochemical catalysis [106−110] Composite strategies involve combining biochar with other materials, such as inorganic minerals, nanomaterials, and activated carbon, to enhance its multifunctionality and properties[111]. Through such combinations, the overall performance of biochar in environmental remediation, catalytic degradation, and energy conversion can be improved. For example, combining biochar with iron-based materials can enhance its catalytic ability in pollutant removal[112]; combining biochar with plant extracts can increase its adsorption capacity for heavy metals and improve its effectiveness in agricultural soil improvement[113]. In addition, biochar-based composite materials also show great application potential in areas such as water treatment and exhaust gas purification.

Recent research progress

-

With the development of science and technology, biochar research has gradually expanded from traditional directions such as carbon sequestration and soil amendment to the development and application of high-performance materials. In recent years, significant progress has been made in the design of novel biochar materials. For example, by introducing carbon-based materials such as graphene and carbon nanotubes, biochar can be endowed with higher electrical conductivity and catalytic activity[114,115]. In addition, nanostructure regulation techniques have been widely applied to adjust pore size, specific surface area, and surface defect structure, thereby enhancing the application potential of biochar in energy storage, electrocatalysis, and environmental remediation. For instance, hierarchical porous biochar can simultaneously possess the high adsorption capacity of micropores and the macromolecular transport capacity of mesopores, thus improving its performance in pollutant removal and energy storage devices[116]. The properties and specific applications of related novel composite materials are shown in Table 4. Moreover, functional modification has become an important direction in biochar research. Methods such as sulfonation, nitrogen doping, and metal loading can further improve the catalytic degradation capacity, ion exchange capacity, and electrochemical stability of biochar[96,117]. In the future, with the integration of machine learning technology, researchers can more precisely regulate the nanostructure and surface chemical properties of biochar through big data analysis and intelligent optimization algorithms, thereby developing more efficient and environmentally friendly biochar materials and promoting their wide application in fields such as energy, environment, and agriculture[118,119].

Table 4. Performance and applications of novel biochar composite materials

Composite type Specific surface area (m2/g) Functional properties Application scenarios Performance improvement Ref. Graphene-biochar 800–1,200 High conductivity, catalytic activity Supercapacitors, electrocatalysis 200%–300% [120] Fe3O4-loaded biochar 300–500 Magnetic recovery, redox capacity Heavy metal adsorption, Fenton reaction 150%–200% [121,122] N-doped porous biochar 600–900 High nitrogen content, alkaline sites CO2 capture, Soil pH regulation 80%–120% [107,123] Chitosan-biochar membrane 50–150 Antibacterial property, biodegradability Water treatment 90%–130% [124] Fe/Cu bimetallic-loaded biochar 200–400 Bimetallic synergistic adsorption,

magnetic recoveryHigh-efficiency Pb2+/Cd2+ adsorption 400%–500% [125] Data collection and bibliometric analysis

-

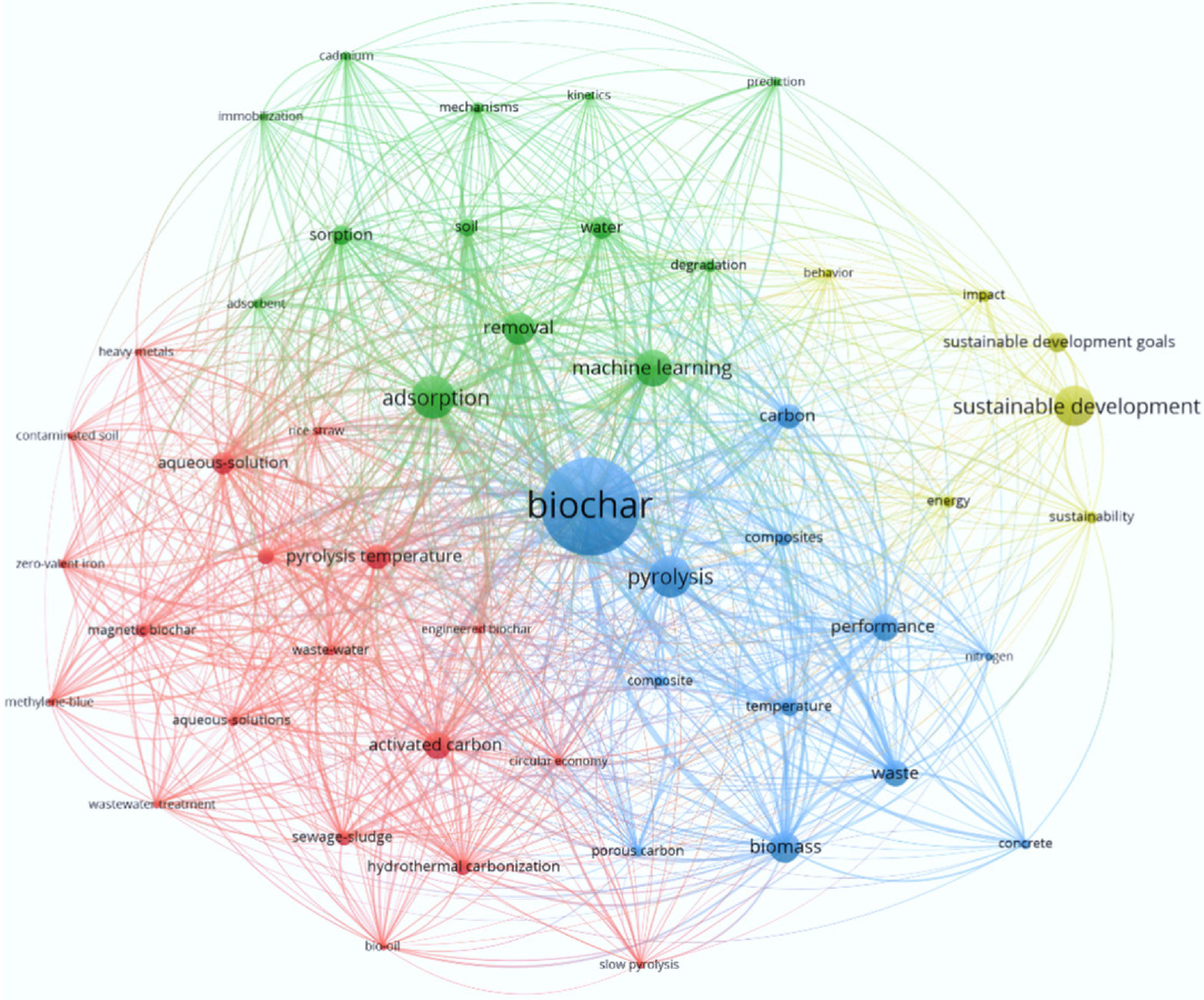

To quantitatively assess the research trends and thematic evolution in the field of biochar and its integration with machine learning and sustainability, a bibliometric analysis was conducted using the Web of Science Core Collection (Clarivate Analytics). The data source was the Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI-Expanded, 1990–present), and the publication period was limited to 2020–2025 to reflect recent advancements. The search strategy applied to in the Web of Science Core Collection was: TS = ('biochar' AND 'machine learning') OR ('biochar materials') OR ('sustainable development'), targeting recent developments at the intersection of biochar technology, data-driven modeling, and sustainability.

From the retrieved dataset, a total of 4,339 unique keywords were identified. To ensure analytical clarity and reduce noise from infrequent terms, the minimum co-occurrence threshold was set at 10 occurrences per keyword. Under this criterion, 162 keywords met the threshold. To enhance the interpretability of the network visualization, the top 50 keywords with the highest total link strength were selected for further analysis. A keyword co-occurrence network was then constructed using VOSviewer, where each node represents a keyword, with node size corresponding to its frequency and link thickness indicating the strength of co-occurrence between keyword pairs. Cluster colors were assigned automatically based on a modularity optimization algorithm, revealing the major thematic groupings within the field.

As shown in Fig. 3, the resulting clusters represent the major research directions and knowledge domains in this field:

Figure 3.

Keyword co-occurrence network (2020–2025) visualized using VOSviewer. Node size represents keyword frequency; line thickness indicates co-occurrence strength. Colors denote thematic clusters: red (remediation & engineered biochar), green (adsorption & modeling), blue (material synthesis), yellow (sustainability & policy).

Cluster 1 (Red): Environmental remediation and engineered biochar

This cluster includes keywords such as 'wastewater treatment', 'activated carbon', 'magnetic biochar', and 'pollutant removal', highlighting the widespread application of engineered biochar materials in environmental pollution control, especially in water treatment.

Cluster 2 (Green): Adsorption mechanisms and data-driven modeling

Comprising keywords like 'adsorption', 'removal', 'kinetics', 'machine learning', and 'prediction', this cluster reflects an increasing integration of mechanistic studies with predictive algorithms for performance optimization.

Cluster 3 (Blue): Biochar production and physicochemical properties

This cluster is dominated by terms such as 'pyrolysis', 'biomass', 'porous carbon', and 'material properties', focusing on biochar synthesis techniques, feedstock characteristics, and structure–function relationships.

Cluster 4 (Yellow): Sustainability and systems-level integration

Featuring keywords like 'sustainable development', 'energy', and 'sustainability goals', this cluster highlights the strategic importance of biochar in supporting global environmental targets and long-term sustainable development goals (SDGs).

This bibliometric analysis illustrates a significant expansion of biochar research from traditional production and material characterization toward integrated, interdisciplinary approaches that leverage artificial intelligence and sustainability science. The emergence of terms such as 'machine learning', 'optimization', and 'life cycle assessment' underscores the field's transition toward intelligent design, system-level evaluation, and policy relevance.

-

With the in-depth exploration of biochar's structural and functional properties, it has demonstrated broad application prospects in resource utilization. Benefiting from its well-developed porous structure, high specific surface areas, diverse surface functional groups, and environmentally friendly carbon-based properties, biochar enables efficient utilization across multiple domains, including water pollution control, solid waste resource recovery, and soil remediation, facilitating the synergistic achievement of ecological environment governance and carbon emission reduction goals[126,127].

Water pollution control

-

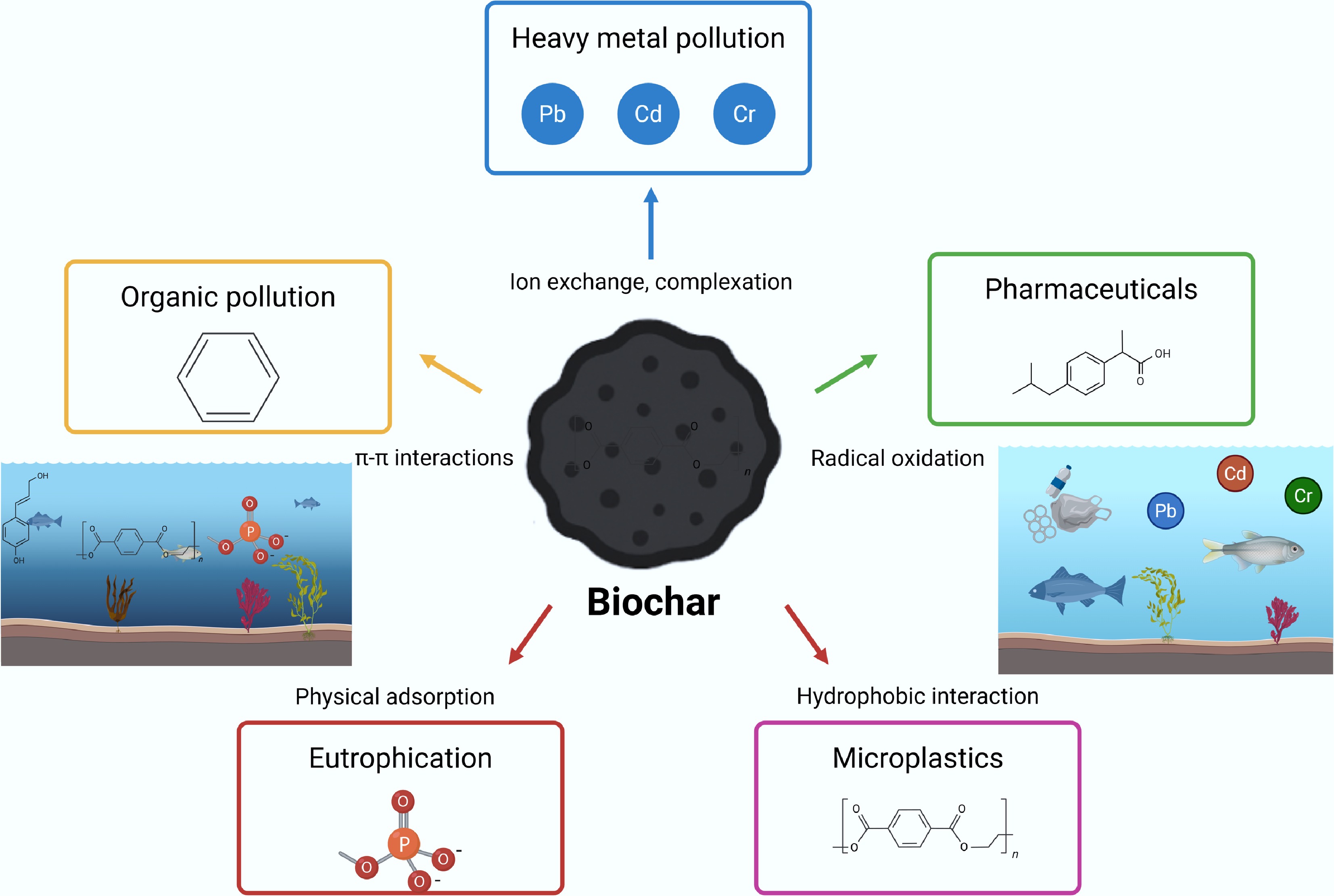

Biochar demonstrates excellent adsorption capacity and remediation potential in water pollution control, and is widely applied in removing various pollutants, including heavy metals, organic pollutants, nutrient pollution (e.g., N and P), and other contaminants.

The remediation of water pollution by biochar primarily relies on mechanisms such as physical adsorption, chemical adsorption, complexation, ion exchange, and co-precipitation[128]. As shown in Fig. 4, the application efficiency of biochar in water pollution control is closely related to its underlying mechanisms of action. For heavy metal pollution (e.g., Pb2+, Cd2+, Cr3+), biochar achieves high removal rates (typically 70%–95%) primarily through ion exchange and surface complexation, whereby abundant oxygen-containing functional groups—such as carboxyl and hydroxyl groups—form stable complexes with metal ions[98,129−132]. In the case of organic pollutants (e.g., antibiotics, pesticides, dyes), adsorption efficiencies of 60%–85% are often obtained via π–π interactions and hydrophobic effects facilitated by the aromatic carbon structure and porous morphology of biochar[133−136]. For nutrient pollution leading to eutrophication, biochar can remove 50%–75% of phosphates and nitrogen oxides through physical adsorption and precipitation processes, thereby preventing algal blooms and improving water quality[135,137,138]. In addition, its porous structure effectively captures microplastics (e.g., polyethylene, polypropylene) with efficiencies reaching 95%–99% via hydrophobic interactions and pore entrapment[139,140]. For pharmaceutical contaminants such as ibuprofen and carbamazepine, functionalized biochars can achieve 75%–88% degradation through adsorption combined with catalytic activation, with the redox-active sites (e.g., Fe3+, quinone groups) promoting radical oxidation (•OH, SO4•−) reactions[141,142]. Overall, the synergistic contribution of high specific surface area, abundant functional groups, alkaline surface properties, and redox capacity enables biochar to act not only as an adsorbent but also as a reactive medium for pollutant transformation and degradation, significantly reducing contaminant loads in aquatic environments.

Research shows that bamboo-derived biochar prepared at a pyrolysis temperature of around 500 °C exhibits high-efficiency performance in adsorbing heavy metals such as lead (Pb2+) and cadmium (Cd2+), with a maximum adsorption capacity exceeding 150 mg/g[143]. In practical applications, the addition of iron-modified biochar to phosphorus-contaminated water bodies significantly reduces total phosphorus concentration and delays algae blooms[144]. Furthermore, biochar rich in oxygen-containing functional groups produced via hydrothermal methods demonstrates effective removal of antibiotics (e.g., tetracycline) and organic pesticide residues. Case studies have also indicated that biochar can serve as a filler material in constructed wetland systems, synergizing with microbial interactions to achieve sustained water purification[145].

Solid waste treatment and material substitution

-

Guided by the 'Reduction-Resource Recovery-Harmless Treatment' concept, biochar has gradually become one of the critical technical pathways for solid waste treatment and functional material substitution.

On one hand, biochar can serve as an adsorbent for pollution control in solid wastes such as municipal sludge, food processing residues, and livestock waste. During the adsorption process, it reduces the release of hazardous substances and enhances overall resource utilization efficiency[146]. On the other hand, biochar itself can act as a structural reinforcement agent or additive for constructing novel composite materials, replacing traditional high-energy-consumption and non-renewable materials, thereby expanding its applications in construction materials, geotechnical materials, and energy storage materials[147].

For example, incorporating an appropriate amount of biochar into cement and concrete preparation processes enhances the material's pore structure regulation capability and crack resistance while achieving carbon sequestration[148,149]; adding biochar to agricultural film materials improves their UV resistance and biodegradability[150]; furthermore, introducing biochar into lithium-ion battery anode materials is expected to enhance conductivity and cycling stability, providing green material alternatives for clean energy systems[151].

Improvement of soil physical properties

-

Although biochar exhibits certain effectiveness in improving soil physicochemical properties, its role in soil physical improvement typically serves as a supplementary function compared to its applications in pollution remediation and material substitution.

The addition of biochar can reduce soil bulk density, enhance aggregate structure stability and water retention capacity, thereby improving soil aeration and moisture retention, particularly showing notable effects in sandy soils and degraded soils[152,153]. Its porous structure facilitates microbial colonization, promoting the restoration of soil ecological functions. However, these improvement effects are constrained by multiple factors, including feedstock type, application rate, and soil type, resulting in region-specific adaptability and time-dependent efficacy that require careful evaluation in practical contexts[154].

-

As a carbon-rich material, biochar demonstrates significant potential in carbon footprint control and climate change mitigation. Its primary carbon reduction effects can be attributed to two aspects: first, its inherent high stability enables long-term sequestration of organic carbon retained during pyrolysis; second, it indirectly reduces greenhouse gas emissions through a series of physicochemical and biological processes in environmental media. The stability of biochar mainly originates from its high aromaticity and low-polarity structure. Particularly under high-temperature pyrolysis conditions, the carbon structure tends to become graphitized, endowing it with strong resistance to decomposition, allowing it to persist stably in the environment over timescales of decades to centuries[155]. In soils, biochar typically exists in free states, mineral-bound states, or embedded within aggregate structures, with these physical and chemical barriers further enhancing carbon sequestration efficiency[156]. Even after undergoing an 'aging' process, its core structure remains stable, maintaining undiminished contributions to carbon sequestration.

Meanwhile, biochar can significantly reduce emissions of major greenhouse gases by regulating and N cycling processes. In agricultural systems, its application reduces CO2 emission sources through two pathways: first, by delaying carbon release via solid carbon storage forms, and second, by replacing waste natural decomposition or open burning pathways through the pyrolysis process itself, thereby reducing carbon emission loads[3]. In environments such as paddy fields, sludge, or organic waste incorporation, biochar optimizes microbial community structure and improves aeration conditions, thereby inhibiting methanogenesis and reducing CH4 emissions. Additionally, its adsorption capacity for ammonium nitrogen and nitrate nitrogen helps mitigate N2O release during denitrification processes, achieving dual benefits of nutrient retention and emission reduction[157,158]. As analyzed in Table 5 regarding feedstock-performance correlations, studies demonstrate that after biochar application, total greenhouse gas emissions in agricultural systems can decrease to varying degrees, with reduction rates ranging from 20% to 70% depending on feedstock type, application methods, and soil environmental conditions.

Table 5. Correlation between biochar feedstock types and carbon sequestration-emission reduction efficiency

Feedstock type Pyrolysis

temperature (°C)Carbon

sequestration rateTotal GHG emission reduction rate Key mechanisms Ref. Crop residues 400–600 60%–75% 40%–60% Inhibition of denitrification enzyme activity; NH4+ adsorption [159,160] Municipal sludge 300–500 40%–50% 30%–50% Heavy metal immobilization; NO3− adsorption; pH regulation [161,162] Wood waste 500–700 85%–90% 20%–40% Landfill diversion; Physical barrier formation to delay decomposition [163] Food waste 250–400 30%–45% 25%–45% Promotion of methanotroph proliferation; C/N ratio adjustment [164,165] Algal biomass 500–700 75%–85% 40%–60% High-temperature stabilized carbon structure, promotes soil carbon-fixing microbial communities [166,167] Poultry manure 300–500 50%–60% 35%–50% Reduces N2O emissions, adsorbs NH3 [168,169] However, it is important to note that in some cases, increased GHG emissions have been observed during biochar production and application, particularly when low-efficiency pyrolysis systems, wet feedstocks, or improper handling conditions are used. In these instances, elevated emissions of CO2 and methane can occur due to incomplete pyrolysis or inefficient gas capture systems. These emissions can offset the positive environmental impact of biochar, particularly if suboptimal pyrolysis temperature and residence time result in the release of volatile gases.

Several key factors contribute to increased emissions:

• Feedstock quality: the use of wet or high-volatile feedstocks can lead to incomplete carbonization and increased methane release during pyrolysis.

• Inefficient pyrolysis conditions: low-temperature or poorly controlled pyrolysis processes may fail to fully carbonize the biomass, resulting in higher CO2 and methane emissions.

• Post-production handling: improper storage or transportation conditions, particularly with high moisture content, may also contribute to GHG emissions after biochar production.

To mitigate these negative impacts, several strategies can be adopted:

• Optimization of pyrolysis processes to ensure complete carbonization and minimize emissions.

• Selection of dry, high-carbon feedstocks that are less likely to produce methane during pyrolysis.

• Improvement of pyrolysis system efficiency, such as through the use of closed-loop systems that capture and recycle gases.

From a global perspective, biochar demonstrates considerable carbon reduction potential. Based on current estimates of globally available agricultural waste annually, converting approximately 10% of it into biochar and applying it scientifically could achieve an annual greenhouse gas reduction of about 0.3–0.6 Gt CO2 equivalent, accounting for roughly 1%–2% of total global anthropogenic emissions[170]. This pathway holds particular implementation feasibility and synergistic benefits in developing countries and agriculture-dominated regions. To accurately quantify biochar's carbon effects, recent studies widely employ life cycle assessment (LCA) methods to systematically analyze its carbon budget across the entire process—from feedstock acquisition and production to final application—supplemented with agricultural greenhouse gas simulation models (e.g., DNDC, DayCent) and global carbon sequestration models (e.g., CBal, BiocharPlus), enabling multi-scale, multi-scenario assessments of emission reduction benefits[171]. These models not only provide a basis for policymaking and pathway optimization but also reveal biochar's strategic value as a 'Nature-based Climate Solution', offering strong support for achieving global carbon neutrality goals[172].

-

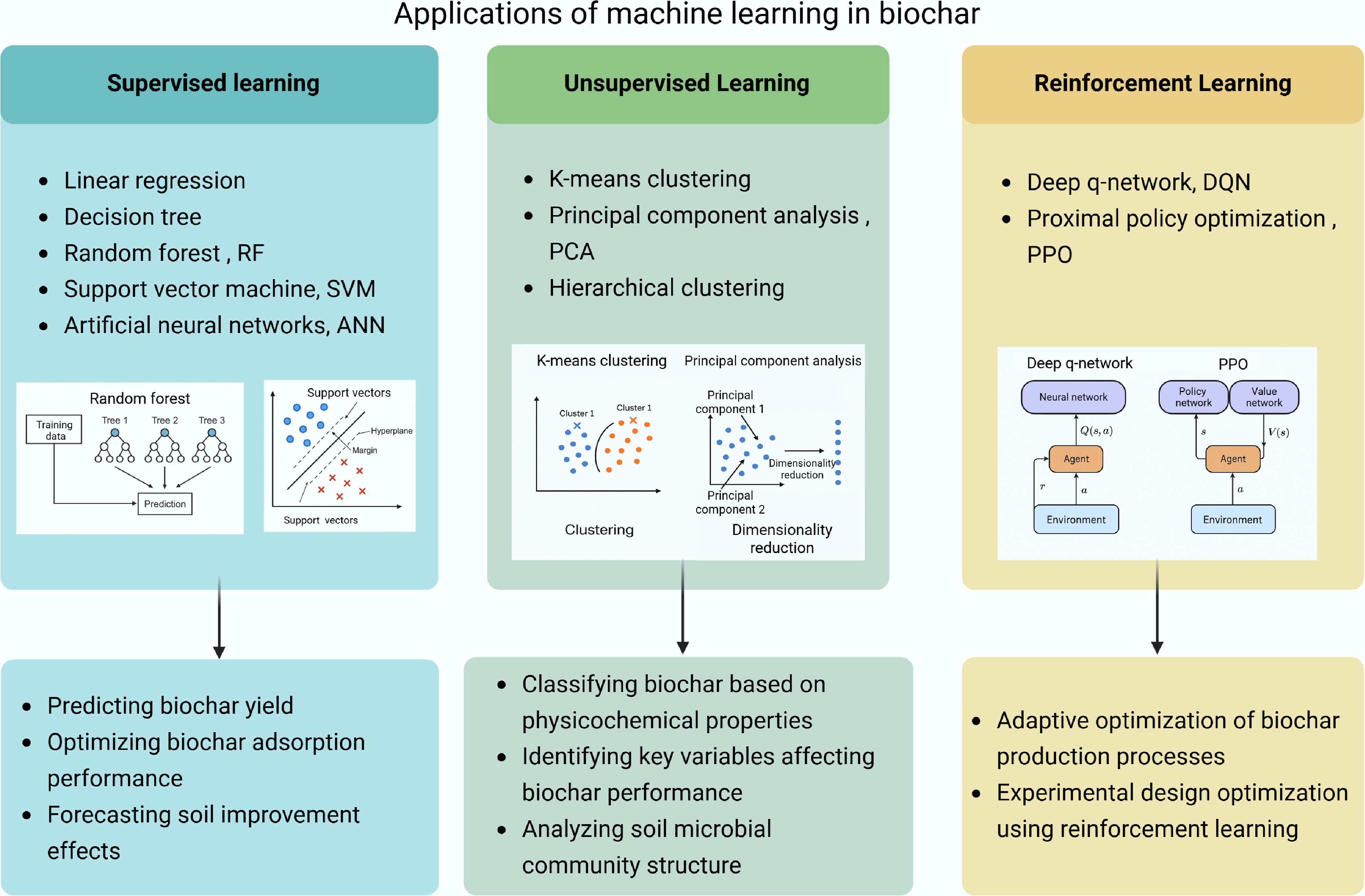

Machine learning is a data-driven modeling approach, and in the field of biochar research, it is primarily divided into three categories: supervised learning, unsupervised learning, and reinforcement learning, with the classification framework as shown in Fig. 5. Supervised Learning is the most common machine learning method, mainly used for predicting the physicochemical properties of biochar and optimizing production processes. Supervised learning models are trained by input data and corresponding labels to establish mapping relationships between input variables and target variables[173]. For example, algorithms such as Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Deep Neural Network (DNN) can predict biochar yield, specific surface area, and pore size distribution under specific pyrolysis conditions for different biomass feedstocks. These models effectively reduce experimental costs and enhance the controllability of biochar materials[174,175]. Furthermore, supervised learning is widely applied to predict biochar's pollutant adsorption capacity, aiding researchers in optimizing its environmental remediation performance.

Unsupervised Learning is primarily used for data pattern recognition and classification in biochar research, commonly applied to analyze the characteristics of different biomass feedstocks and their pyrolysis products[176,177]. For example, methods such as K-Means Clustering (K-Means) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) can classify various biochar samples to identify key factors influencing biochar performance. Unsupervised learning can also analyze degradation patterns of biochar during long-term applications, assessing its stability in soil improvement and carbon sequestration. Reinforcement Learning (RL), which learns through interactions between agents and environments, is suitable for optimizing biochar preparation processes[177]. In biochar production, reinforcement learning can automatically adjust experimental parameters such as pyrolysis temperature, reaction time, and catalyst dosage to achieve optimal material performance. In the future, with the continuous advancement of machine learning technologies, the integrated application of supervised learning, unsupervised learning, and reinforcement learning will provide more efficient solutions for intelligent design and precise regulation of biochar.

Machine learning in biochar material design

-

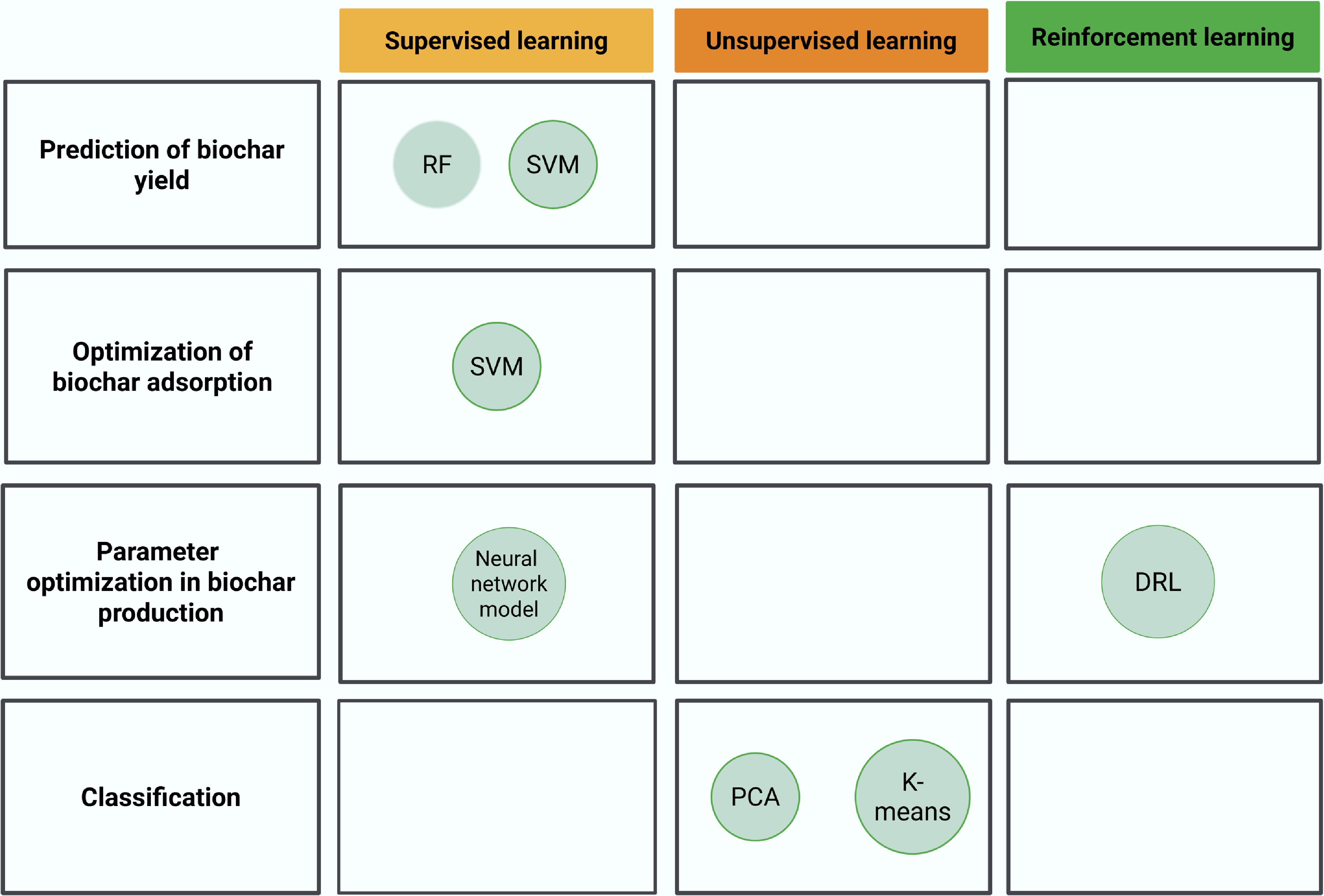

Machine learning plays a significant role in the design of biochar materials, enabling efficient analysis of the complex relationships between feedstock properties, process parameters, and end-product performance, thereby guiding optimized design[178]. Different biomass feedstocks (e.g., wood, crop straw, sewage sludge) under varying pyrolysis conditions produce biochar with distinct porous structures, surface chemical properties, and adsorption capacities. As shown in Fig. 6, supervised learning methods such as Random Forest (RF) and Support Vector Machine (SVM) have been widely applied in predictive modeling and optimization. RF models can accurately predict biochar yield and key physicochemical properties—such as specific surface area, pore size distribution, and carbon content—based on feedstock characteristics and pyrolysis parameters, while effectively reducing overfitting and handling noisy datasets[175,179−182]. SVM has been successfully used to optimize adsorption performance, particularly for heavy metal removal, leveraging its ability to model complex nonlinear relationships in small datasets[178,179,182,183].

Process parameter optimization has also benefited from the application of artificial neural networks (NN), which can learn complex nonlinear patterns and flexibly handle diverse input variables, thereby enabling fine-tuning of pyrolysis conditions for targeted biochar characteristics[179,182,184−186]. In the realm of unsupervised learning, clustering algorithms such as K-means have been applied to classify biochars based on their physicochemical attributes, facilitating rapid identification of material categories and potential applications[174,187−190]. Dimensionality reduction techniques like principal component analysis (PCA) further assist in identifying key factors influencing biochar performance, improving data interpretability while minimizing information redundancy[191−195].

In addition, reinforcement learning (RL) has emerged as a promising tool for adaptive process optimization and automation. Deep reinforcement learning (DRL) enables real-time control of biochar production by dynamically adjusting operational parameters in response to feedback signals[176,196−199], while multi-agent RL has been explored for autonomous experimental design, accelerating the discovery of optimal synthesis pathways[200−202]. Overall, the integration of these algorithms—ranging from supervised to unsupervised and reinforcement learning—provides a comprehensive toolkit for predictive modeling, optimization, classification, and adaptive control, ultimately enhancing the efficiency, reproducibility, and performance of biochar materials in environmental remediation, energy storage, and sustainable agricultural applications.

Machine learning in the life cycle assessment of biochar

-

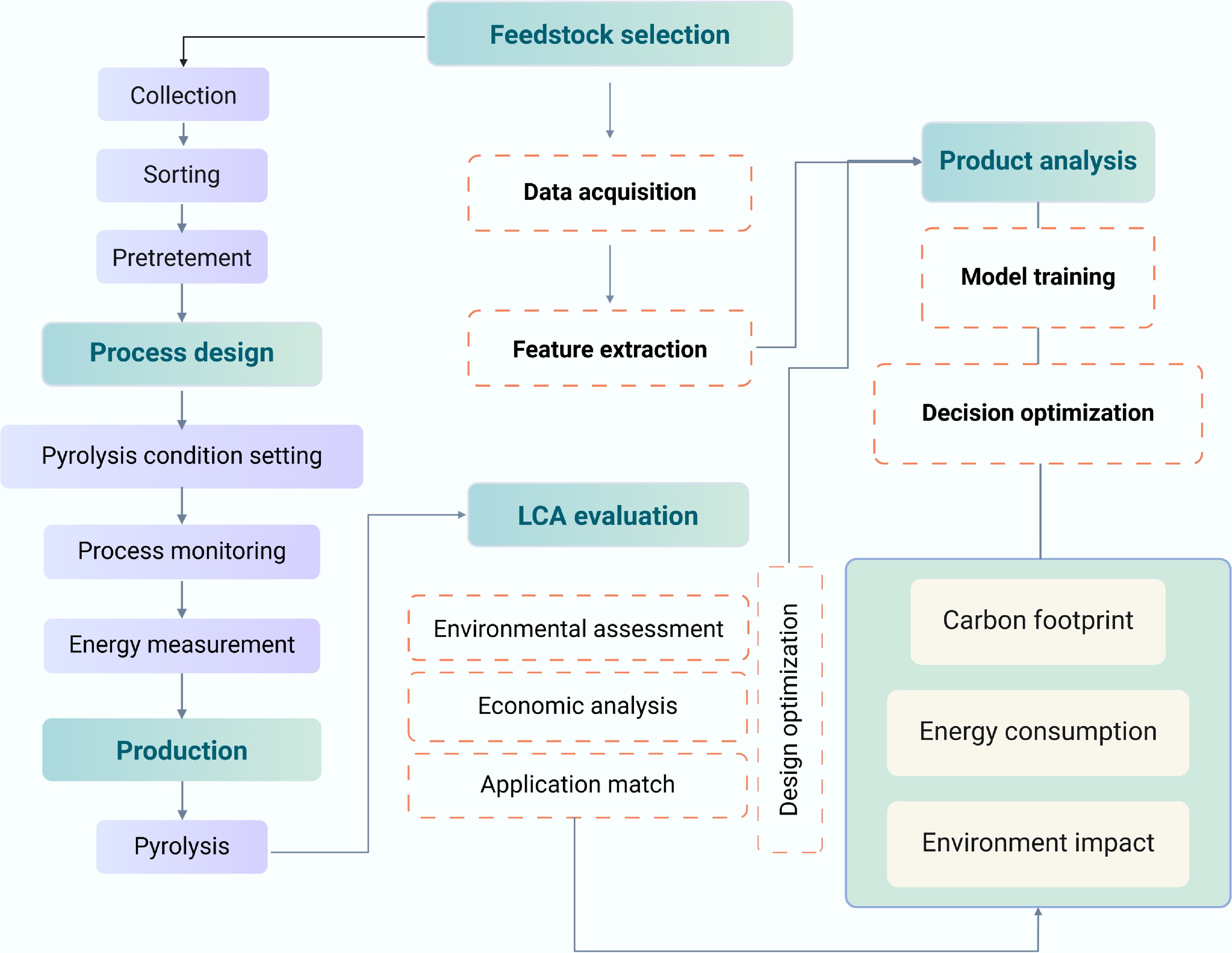

The life cycle analysis of biochar encompasses a closed-loop process of 'feedstock–production–application–assessment–feedback'. First, agricultural, forestry, and urban organic wastes are collected and preprocessed to form standardized feedstocks. Subsequently, preparation is completed by regulating parameters through pyrolysis or hydrothermal carbonization processes. Next, transportation routes are optimized, and functional modifications are applied based on requirements such as soil remediation or water treatment. Following this, dynamic assessment is performed by quantifying full-chain energy consumption, carbon emissions, and pollution control efficiency. Finally, the results are fed back into feedstock selection and process optimization, establishing a sustainable system that integrates 'resource cycling—environmental benefits', with its phased workflow illustrated in Fig. 7.

Life cycle analysis (LCA) is a critical tool for assessing the environmental impacts of biochar, and the integration of machine learning can enhance the accuracy and efficiency of LCA. In terms of environmental impact assessment, machine learning can predict energy consumption, carbon footprint, and pollutant emissions during biochar production, aiding researchers in optimizing production processes to reduce environmental burdens[176]. For example, using regression models or deep learning algorithms, carbon emissions under different feedstocks and pyrolysis conditions can be predicted based on historical data, enabling the formulation of greener production strategies[203,204]. Regarding sustainability indicator development, machine learning can integrate multi-source data to establish a comprehensive sustainability evaluation system for biochar. Through cluster analysis, principal component analysis (PCA), and other methods, key factors influencing biochar sustainability can be identified, and scientifically sound indicator systems can be constructed[191]. In terms of optimization decision support, machine learning algorithms can be applied to optimize the entire biochar supply chain, including feedstock selection, process parameter optimization, and product application scenario matching. For instance, genetic algorithms and reinforcement learning can be employed to develop intelligent optimization models, achieving dynamic optimization of the biochar supply chain and improving resource utilization efficiency.

Recent advances in research

-

In recent years, significant progress has been made in the application of deep learning and multi-objective optimization algorithms in biochar research. Deep learning techniques, such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN), can predict the microstructure, specific surface area, and pore size distribution of biochar formed from different biomass feedstocks under specific pyrolysis conditions by analyzing large-scale experimental data and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images, thereby improving the precision of biochar material design[205,206]. Building on this, multi-objective optimization algorithms can balance key performance indicators such as adsorption capacity, mechanical strength, and carbon sequestration efficiency in high-dimensional parameter spaces, achieving comprehensive optimization of biochar performance[186,207]. For example, in water pollution control applications, researchers have employed genetic algorithms and particle swarm optimization to identify optimal preparation conditions, improving pollutant removal rates while reducing production costs[28,208]. Typical applications are summarized in Table 6. In addition, an intelligent optimization framework integrating deep learning and optimization algorithms is gradually emerging, combining experimental data and computational simulation to enable real-time prediction and dynamic optimization of biochar performance[176,209]. With the advancement of computing power and the expansion of data resources, the integration of deep learning and multi-objective optimization will further drive the intelligent design of biochar, providing more efficient solutions for its application in environmental remediation, energy storage, and sustainable agriculture.

Table 6. Typical applications of deep learning and multi-objective optimization in biochar research

Method type Application direction Representative applications Technical advantages Ref. CNN Image structure recognition Predicting specific surface area and pore size Extracts microstructural image features [212] RNN Dynamic data modeling Analyzing performance variations during pyrolysis Adapts to time-series data [206] Multi-objective optimization Comprehensive performance optimization Simultaneously optimizing yield, adsorption rate,

and energy consumptionCollaborative optimization with high efficiency [213] GA/PSO Rapid process optimization Identifying optimal pyrolysis temperature and modifier dosage Broad search range & rapid convergence [214] MTDL (Multi-task

deep learning)Multi-objective collaborative optimization Simultaneously optimizing biochar's adsorption

of cadmium (Cd) and methane (CH4) emission reduction efficiencyCross-task parameter sharing, maximization of synergistic effects [215] Notably, recent studies have applied machine learning methods to the lifecycle assessment (LCA) framework of biochar to achieve efficient prediction and management of carbon footprints and environmental impacts. For example, some studies have developed a carbon emission prediction system that integrates random forest models with LCA databases, enabling precise estimation of greenhouse gas emissions under different feedstocks and pyrolysis conditions, with prediction accuracy exceeding 90% and significantly reducing analysis time[204,210]. Other research has employed a deep reinforcement learning (DRL) framework to simulate the dynamic interaction between the pyrolysis process and LCA feedback, thereby gradually optimizing biochar production pathways to minimize greenhouse gas emissions across the entire lifecycle[211]. These cases demonstrate that machine learning shows promising prospects and practical value in LCA modeling, with the potential to provide strong data support for low-carbon design of biochar, environmental policy evaluation, and decision-making support.

Researchers have utilized machine learning to construct sustainability evaluation systems for biochar, enabling a more comprehensive quantification of its environmental, economic, and social impacts. For instance, based on supervised learning algorithms such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Random Forest (RF), researchers can predict the environmental impacts of different biochar production methods and develop dynamic, visualized evaluation models to assist policymakers in formulating more scientifically grounded sustainability strategies[216]. In addition, with the growing demand for closed-loop supply chain optimization, the application of machine learning in supply chain management has attracted increasing attention. Algorithms such as reinforcement learning and Bayesian optimization can be employed to optimize various stages of the biochar supply chain, including production, transportation, storage, and end-use, thereby enhancing resource utilization, reducing carbon footprints, and achieving more efficient waste-to-resource pathways[25]. In the future, as the integration of machine learning and sustainability research deepens, the biochar industry is expected to move toward greater intelligence and greenness, offering new technological support for global carbon neutrality goals and ecological sustainability.

-

Despite the significant promise shown by machine learning (ML) in biochar research, several limitations remain. First, ML model performance is highly dependent on the quality of input data. Incomplete, noisy, or fragmented datasets can introduce significant bias into predictions[217]. Second, although many deep learning models deliver high accuracy, their 'black-box' nature leads to poor interpretability, making it difficult for researchers to understand how individual parameters influence biochar properties. Additionally, training and optimizing complex ML models—particularly for high-dimensional, multivariate data—requires substantial computational resources, which can limit their scalability and widespread use in biochar applications[218].

Challenges in data acquisition, processing, and sharing

-

The success of ML models depends heavily on access to large-scale, high-quality, and standardized datasets. However, biochar data acquisition is often hindered by discrepancies in experimental protocols, feedstock types, and measurement techniques across different studies. These inconsistencies complicate data integration and reduce the reproducibility of ML models. Moreover, intellectual property concerns and data privacy issues often restrict open sharing of experimental datasets, thereby limiting model generalization[219]. To address this, future efforts should prioritize the establishment of unified data processing protocols, standardized reporting formats, and secure data-sharing platforms to ensure data consistency and promote high-quality model training.

Importance of interdisciplinary collaboration

-

Biochar research spans multiple domains, including materials science, environmental engineering, agronomy, and data science. Effective integration of ML requires researchers to either possess interdisciplinary knowledge or collaborate closely with experts in computer science and artificial intelligence. Interdisciplinary collaboration can accelerate the development of innovative modeling approaches and bridge the gap between theoretical model design and practical applications. Furthermore, assessing the sustainability and societal benefits of biochar calls for integration with ecology, economics, and policy research. Such cooperation will not only support the development of unified biochar databases but also drive holistic strategies for efficient biomass utilization and sustainable development.

Future research directions

-

In the future, biochar research will increasingly benefit from advanced machine learning methods, driven by continuous improvements in computational power and algorithm optimization. Emerging technologies such as self-supervised learning and federated learning are expected to enhance model generalization in data-scarce or distributed environments. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and density functional theory (DFT) calculations will continue to play a key role in understanding biochar's microstructure and performance, while the integration of these methods with machine learning will facilitate multi-scale modeling, allowing accurate predictions from the molecular scale to macroscopic behavior[40,220−223]. These combined approaches will be pivotal in optimizing biochar materials, enabling more precise and efficient design. In the context of sustainability-driven design, intelligent optimization algorithms will also be applied across the entire life cycle of biochar, including feedstock selection, production, environmental impact minimization, and supply chain management. The fusion of machine learning and experimental research will ultimately drive biochar studies toward a more efficient and sustainable development pathway.

-

This review provides a comprehensive overview of the multifunctional applications of biochar in resource utilization and carbon footprint control, emphasizing its roles in structural regulation, pollution remediation, and greenhouse gas mitigation. By comparing pyrolysis and hydrothermal carbonization techniques, it discusses how feedstock characteristics and process parameters significantly influence biochar properties and examines recent advances in functionalization and composite strategies to enhance environmental performance. Building on this, the review focuses on the application potential of machine learning technologies in biochar material design, performance prediction, process optimization, and life cycle analysis, showcasing their key roles in improving research efficiency, accelerating material screening, and enabling intelligent decision-making.

However, the application of machine learning in the biochar field still faces challenges such as poor model interpretability, low data standardization, and insufficient interdisciplinary collaboration. To achieve large-scale deployment of biochar and contribute to global carbon neutrality goals, it is necessary to strengthen foundational data infrastructure, build unified open-access databases, and promote deep integration among materials science, environmental engineering, and artificial intelligence. In summary, the synergistic development of biochar and machine learning holds considerable promise for supporting waste resource utilization, maximizing carbon reduction benefits, and laying the technological foundation for building a green, low-carbon, and circular bioeconomy.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design, manuscript review: Jiang Y, Xie S, Abou-Elwafa SF, Mukherjee S, Singh RK, Tran HT, Shi J, Trindade H, Zhang T, Chen Q; Material preparation, data collection, and analysis: Jiang Y, Xie S, Zhang T; draft manuscript preparation: Jiang Y. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The research was sustained by a grant from the National Key Research and Development Program of China 'Intergovernmental Cooperation in International Science and Technology Innovation' (Grant No. 2023YFE0104700), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31401944).

-

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

-

Biochar enables effective waste valorization and long-term carbon sequestration.

Machine learning boosts efficiency in biochar design, modification, and assessment.

Integrating ML with LCA enhances climate benefits and supports green innovation.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang Y, Xie S, Abou-Elwafa SF, Mukherjee S, Singh RK, et al. 2025. Machine learning-enabled optimization of biochar resource utilization and carbon mitigation pathways: mechanisms and challenges. Biochar X 1: e002 doi: 10.48130/bchax-0025-0003

Machine learning-enabled optimization of biochar resource utilization and carbon mitigation pathways: mechanisms and challenges

- Received: 13 June 2025

- Revised: 10 August 2025

- Accepted: 27 August 2025

- Published online: 11 September 2025

Abstract: As an environmentally friendly and carbon-rich material, biochar holds significant application potential in waste valorization, water pollution remediation, and carbon sequestration. In recent years, machine learning has emerged as a powerful data-driven tool and is being increasingly applied in biochar research. This review systematically summarizes the fundamental concepts, preparation methods, and key application areas of biochar, with a particular focus on recent advances in its roles in carbon footprint reduction and resource utilization. The applications of machine learning in process optimization, material design, and life cycle assessment are thoroughly discussed. Moreover, the challenges related to data acquisition, model interpretability, and interdisciplinary collaboration are critically analyzed. Importantly, the review highlights that biochar application can reduce total greenhouse gas emissions by 20%–70%, with carbon sequestration rates reaching up to 90% depending on feedstock and pyrolysis conditions. Machine learning models such as random forest and deep neural networks have achieved prediction accuracies exceeding 90% in forecasting biochar yield, surface area, and adsorption capacity, significantly improving design efficiency and environmental performance. Looking ahead, the integration of advanced techniques such as deep learning, multi-objective optimization, and self-supervised learning is expected to further enhance the environmental benefits and intelligent design of biochar, thereby offering strong technical support for global climate mitigation and the circular economy development.

-

Key words:

- Biochar /

- Machine learning /

- Waste utilization /

- Hydrothermal carbonization /

- Pyrolysis /

- Modified biochar