-

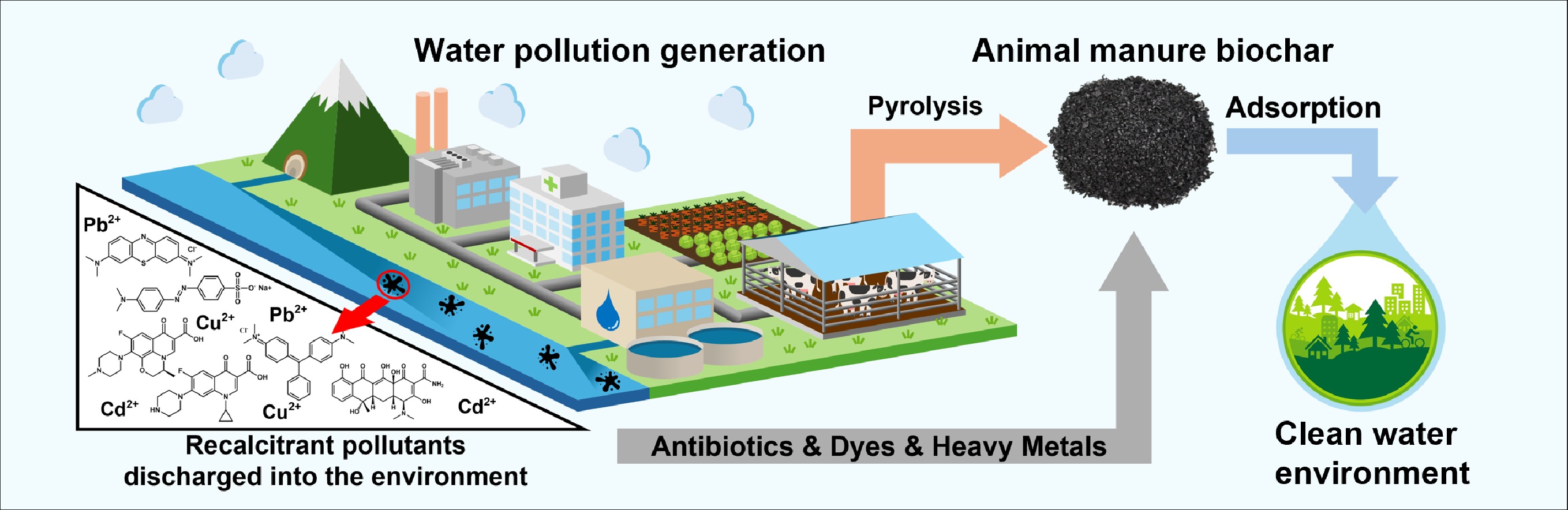

Water is an essential resource for humanity because it is fundamental to sustaining life, supporting agriculture, and maintaining public health[1]. Economic growth, technological advancement, and urbanisation have further driven the expansion of water-intensive industries, such as power generation, textiles, chemicals, and food processing, thereby intensifying the demand for water[2,3]. As water consumption has increased, the generation of wastewater containing chemicals, heavy metals, fertilisers, pharmaceuticals, and other contaminants from various sectors has also increased[4]. Without proper treatment prior to discharge, this wastewater pollutes the surrounding water bodies, including rivers, groundwater, and oceans, leading to severe impacts on ecosystems and public health[5]. Consequently, the implementation of an effective water treatment strategy is imperative for securing clean water resources and protecting the surrounding ecosystems[6].

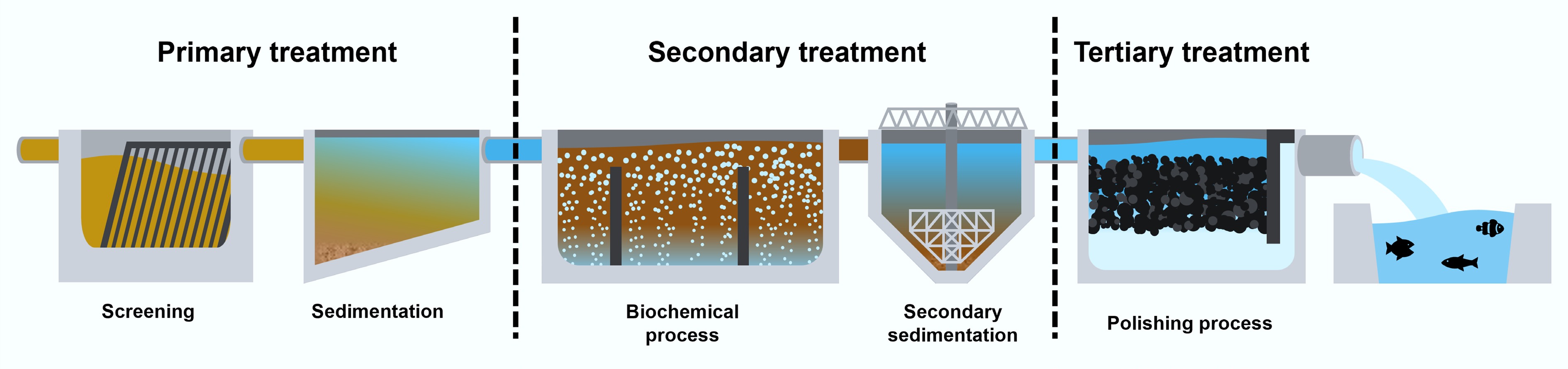

Conventional wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), which are effective in removing organic matter and suspended solids through primary (physical) and secondary (biological) processes, face limitations in eliminating specific industrial pollutants[4].Recalcitrant organic compounds (e.g., dyes, antibiotics, and pesticides) exhibit complex molecular structures that resist biodegradation during conventional biological treatment[5]. Similarly, heavy metals (e.g., Pb, Cu, and Cd) cannot be degraded. Therefore, as illustrated in Fig. 1, the development and implementation of advanced treatment technologies, including membrane filtration, precipitation, coagulation-flocculation, electrochemical treatment, ion exchange, and adsorption, as tertiary processes in WWTPs have received significant attention for the removal of recalcitrant organic pollutants and heavy metals[6]. Among them, adsorption has emerged as a versatile and cost-effective method for removing diverse heavy metals and organic pollutants and can be tailored with various adsorbents for specific contaminants[7]. Furthermore, adsorption can remove trace-level and nonbiodegradable pollutants[8]. Notably, adsorbents such as activated carbon, biochar, clay minerals, and engineered nanomaterials offer high surface areas and functional groups, enabling the immobilisation of pollutants through physical or chemical binding[9−11]. Among these, biochar has emerged as an advantageous adsorbent because of its cost-effectiveness and commitment to environmental sustainability. Biochar is a carbon-rich material typically generated through the thermal decomposition of biomass in an oxygen-free environment, known as pyrolysis[12]. Furthermore, the physicochemical properties of biochar that enhance its efficacy in pollutant removal can be optimised through careful feedstock selection and the regulation of pyrolysis conditions.

To utilise biochar as a sorptive material, a constant supply of raw feedstock at low cost must be ensured[13]. Among biomass sources, animal manure represents a promising and economically viable option owing to its high availability as a stockbreeding byproduct. Animal manure is generated during the massive breeding of livestock globally because of constant population growth and meat consumption[14]. This abundance enables large-scale and sustainable use of biochar in wastewater treatment applications[15].dditionally, animal manure is often costly to manage and poses a risk of environmental pollution and pathogen transmission[16]. Therefore, using animal manure as biochar feedstock contributes to reducing waste management burdens while transforming problematic materials into valuable resources.

Animal manure biochar has distinct physicochemical advantages that enhance its efficacy as an adsorbent. Compared with lignocellulosic residues, animal manure is characterised by higher concentrations of N, P, and inorganic elements such as Ca, K, and Mg, which originate from undigested feed and bedding materials[17]. These components impart unique physicochemical properties to the resulting biochar, including enhanced surface functionality, ion exchange capacity, and mineral-rich phases (e.g., carbonates and phosphates)[18]. These features facilitate physical (hydrophobic interactions, van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding, and pore-filling) and chemical (electrostatic attraction, π−π electron donor–acceptor [EDA] interactions, ion exchange, precipitation, and surface complexation) interactions, enabling the effective adsorption of various pollutants, including dyes, pharmaceutical residues, and heavy metals[19,20]. Despite these advantages, comprehensive studies on the utilisation of animal manure biochar have rarely been reported. This review provides a comprehensive overview of the production, activation, and application of animal manure biochar for the removal of hazardous pollutants (dyes, antibiotics, and heavy metals) from wastewater. It offers practical insights into how the pyrolysis conditions, manure type, surface modifications, and intrinsic mineral composition influence the adsorption performance. Conclusively, the dominant adsorption mechanisms are elucidated to inform pollutant-specific strategies for the effective application of manure-derived biochar. Additionally, this review highlights the economic feasibility, limitations, and future research directions necessary to advance the practical use of manure biochar in wastewater treatment applications.

-

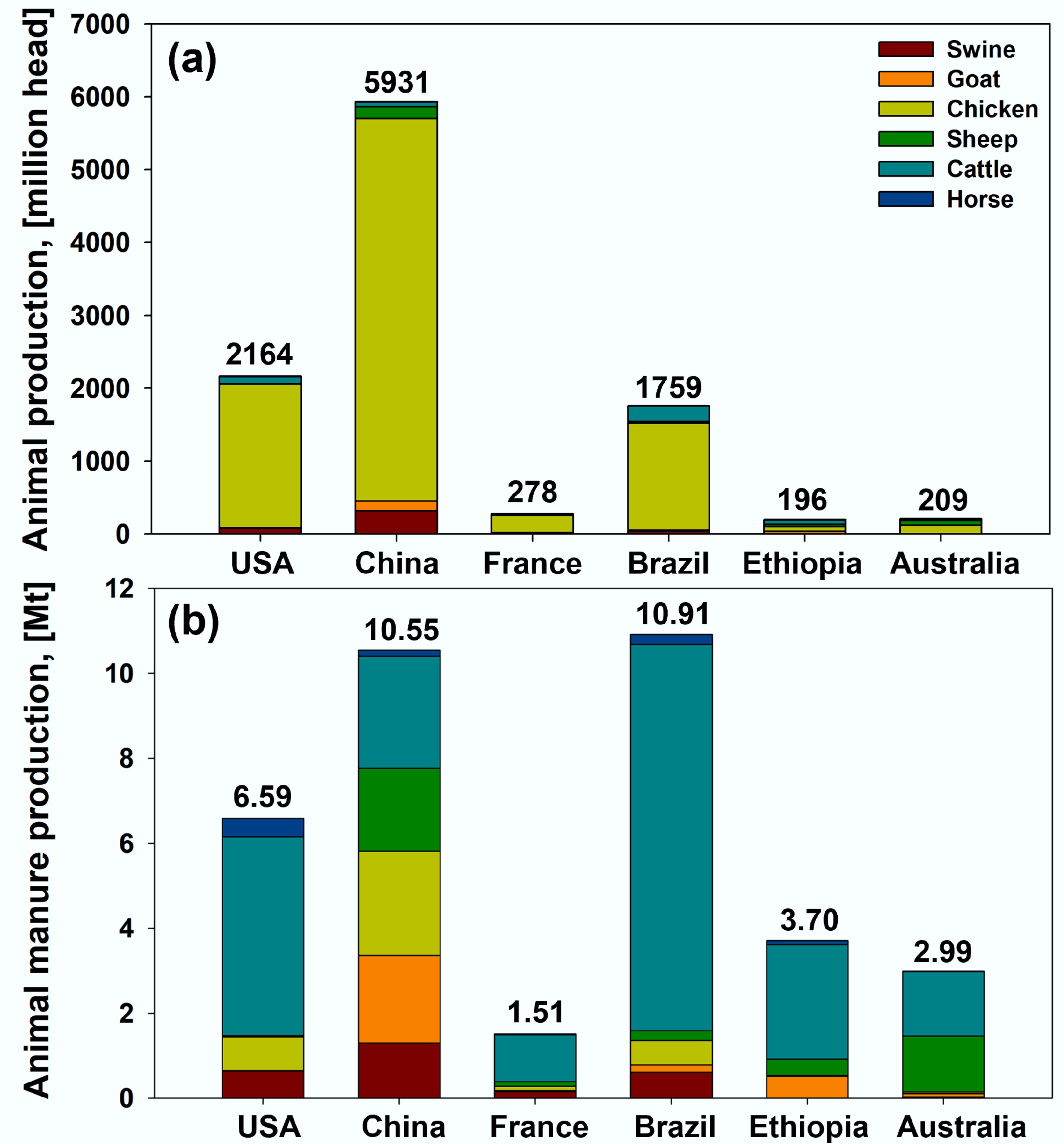

With rapid population growth and the need for protein consumption, the global demand for meat has increased significantly in recent decades. According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development statistics, global meat consumption has increased from 227 Mt in 2000 to 324 Mt in 2019 and is expected to increase by another 11% by 2029[21]. The continuous increase in meat consumption has resulted in an increase in the animal population and manure. Figure 2 illustrates the animal populations and manure production in representative countries on six continents in 2019. The total population of animals raised is highest in China, followed by the USA, Brazil, France, Australia, and Ethiopia (Fig. 2a). Despite its numerical dominance, the generation of animal manure in Brazil was higher than that in China (Fig. 2b). The majority of global animal manure production is attributed to cattle and sheep, which contribute over 80% of the total output (Fig. 2b). This is because manure generation is closely correlated with the animal's weight.

Figure 2.

(a) Annual animal (swine, goat, chicken, sheep, cattle, and horse) populations and (b) their manure production in the USA, China, France, Brazil, Ethiopia, and Australia (2019)[22].

For large-scale animal production, animals are bred in facilities designed to maximise the population density for intensive farming. This high-density practice influences the properties of the resulting manure. The manure generated in such systems is not solely in solid form; it is typically produced as a slurry owing to its simultaneous generation with urine[23]. Additionally, it contains a complex mixture of lignocellulosic biomass, including undigested feed (crops) and bedding materials (grass and straw)[24]. Manure produced in livestock facilities comprises animal excreta and organic biomass[25]. Table 1 summarises the proximate composition and organic and inorganic contents of animal manure in comparison with those of representative crop residues.

Table 1. The proximate, organic, and inorganic contents of animal manure with reference to representative crop residues

Y Parameter Lignocellulosic biomass (wt.%) Animal manure waste (wt.%) Wheat straw Rice straw Swine manure Goat manure Chicken manure Sheep manure Cattle manure Proximate analysis (dry sample basis) Moisture 1.8–6.3 Not determined 4.4–13.6 6.0–8.7 5.6–10.0 8 1.6 Volatile matter 61.0–83.3 65.5–76.1 52.1–69.4 62.7–69.5 61.3–74.6 59.98 60.9–73.5 Fixed carbon 10.3–29.5 14.3–19.2 10.5–22.8 4.5–12.9 6.2–22.8 12.79 10.3–16.3 Ash 1.4–17.6 9.6–19.6 10.2–35.8 17.3–29.0 11.6–28.1 16.1–19.2 10.2–31.9 Ultimate analysis (dry sample basis) C 41.0–46.7 30.5–40.4 37.7–52.2 26.5–40.1 28.2–43.9 41.5–42.4 34.4–42.4 H 2.3–6.0 3.9–5.6 3.8–7.8 3.7–5.9 3.5–6.5 5.2–6.1 4.9–5.9 O 40.6–51.4 39.6–47.3 28.9–44.2 37.4–41.2 32.8–35.5 31.4–32.1 28.7–42.3 N 0.1–0.8 0.4–1.4 1.1–5.8 1.5–2.0 3.7–8.1 2.1–2.9 1.9–2.3 S 0.1–0.2 0.6 > 0.2–0.7 0.03 0.2–1.5 0.4–0.6 0.3–0.6 Inorganic material (dry sample basis) P 0.1 > 0.5–0.7 1.6–4.9 1.0–1.9 0.4–2.4 0.4–1.4 0.2–1.5 Ca 0.3–0.4 0.3–0.6 0.2–5.0 2.1–3.9 1.8–5.9 0.8–5.11 0.1–8.3 K 1.8–2.6 1.5–2.3 0.4–7.8 1.6–3.4 0.7–3.1 1.9–3.3 0.9–6.2 Mg 0.1–0.2 0.2–0.5 0.5–2.0 0.8–1.8 0.3–0.7 0.5–0.7 0.1–1.1 Na 0.2–0.3 0.3 > 0.1–0.4 − 0.4–0.9 0.4 0.2–0.4 Fe 0.1 > 0.1 > 0.1–1.3 0.2 0.1 > − 0.3–0.4 Al 0.1 > 0.3 > 0.1–0.4 0.2 0.1 > − 1.6 Si 2.4 5.0–13.9 0.1 > − − − − As summarised in Table 1, animal manure contains higher levels of N, P, and inorganic (Ca, K, Mg, Na, Fe, Al, and Si) components than wheat or rice straw. These components originate from the undigested residues of essential nutrients supplemented in the feed to support the animals' optimal growth and productivity[26,27]. Given that elements such as N, P, and inorganic components are essential for all living organisms, animal manure has potential as a nutrient source in agriculture to enhance soil fertility[28]. Despite the abundance of nutrients, the direct application of animal manure is limited by sanitation concerns, including the potential transmission of pathogens and toxicants[16]. Thermochemical conversion has gained attention as a promising valorisation pathway, enabling the recovery of valuable products such as syngas, bio-crude, and biochar from organic matter while simultaneously stabilising hazardous substances[29]. In particular, the abundance of heteroatoms and metals in animal manure makes biochar an efficient sorptive material[30]. These elements alter the electron density of the C matrix in biochar, enhancing its adsorption performance.

-

Biochar is a C-rich porous material characterised by a high surface area, well-developed porosity, and surface functional groups[31]. Because of its physicochemical properties, it has been widely applied as an adsorbent for the removal of pollutants from wastewater. Therefore, it is essential to develop appropriate surface properties to utilise biochar effectively as an adsorbent. Biochar is typically produced through the thermochemical decomposition of biomass under oxygen-free conditions, which is known as pyrolysis[32]. During pyrolysis, biochar is formed via primary and secondary thermal cracking processes. Under primary cracking, rising temperatures break the covalent bonds in biopolymers, leading to the release of volatile matter (VM; gaseous and liquid pyrolysates) and the formation of a solid carbonaceous residue (biochar)[33]. In secondary reactions, the released VM undergoes further thermal decomposition and reduction (repolymerisation), resulting in additional C-rich solid residues, commonly referred to as coke[34]. The surface properties and yield of the resulting biochar are influenced by the extent of these pyrolytic reactions, which, in turn, are affected by operational parameters such as reaction temperature, heating rate, and residence time[35]. Depending on these parameters, the pyrolysis is typically classified as flash, fast, or slow.

Pyrolysis

-

Flash pyrolysis is generally conducted at high temperatures (400–1,200 °C) with rapid heating rates (> 1,000 °C min–1) and a reaction time of < 2 s[36−38]. Fast pyrolysis is conducted at high temperatures (400–1,000 °C), fast heating rates (300–1,200 °C min–1), and short residence times (0.5–10 s)[36,37]. Flash and fast pyrolysis processes typically do not produce biochar because they tend to yield VM (Table 2). This is attributed to the high heating rates and reaction temperatures, which facilitate primary decomposition reactions while simultaneously inhibiting secondary reactions such as the repolymerisation of volatiles into coke. In contrast, slow pyrolysis is conducted at lower temperatures (300–900 °C), slower heating rates (5–60 °C min–1), and longer residence times (5–360 min)[36,39]. The slow heating rate naturally results in a prolonged residence time at low reaction temperatures, facilitating the secondary reaction of the bio-crude product and promoting the formation of coke through repolymerisation[40]. Therefore, slow pyrolysis is preferred for producting biochar owing to its high yield.

Table 2. Operation conditions, biochar production yields, and target products of different thermo-chemical processes

Process Temperature (°C) Heating rate (°C min–1) Reaction medium Residence time Biochar yield (wt.%) Target product Flash pyrolysis 400–1,200 > 1,000 Inert gas (N2, Ar, etc.) < 2 s 10–20 Pyrolytic oil Fast pyrolysis 400–1,000 300–1,200 0.5–10 s 15–35 Pyrolytic oil Slow pyrolysis 300–900 5–60 5 min–12 h 25–50 Biochar Activation of animal manure biochar

-

The adsorption performance of biochar is influenced by its surface properties, including specific surface area, pore structure, and reactive functional groups[31]. However, biochar produced through conventional pyrolysis often exhibits limited surface development as a result of pore blockage or collapse during carbonisation, which restricts its adsorption capacity[41]. Additionally, elevated pyrolysis temperatures destroy or alter the surface functional groups, further reducing its adsorption potential[42]. In this context, activating biochar can enhance its surface properties by generating porosity and introducing various functional groups before its application as an adsorbent[42]. Various activation strategies have been explored, including physical and chemical treatments, and metal impregnation.

Physical activation

-

Physical activation involves activating biochar at elevated temperatures with or without the presence of oxidising agents such as air, steam, CO2, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), or their mixtures. The CO2 and H2 gases evolved during pyrolysis in the presence of oxidising agents contribute to the activation of the biochar's surface. This activation promotes the development of micropores and mesopores, resulting in a wider pore size distribution[43]. It should be noted that CO2 activation can effectively enhance the formation of micropores through controlled gas–solid reactions, while steam activation primarily increases the surface area and mesopore volume[44]. In addition, physical activation can introduce oxygen (O)-containing functional groups, such as phenolic and carboxylic groups, onto the biochar's surface[45]. For instance, H2O2 treatment expands the micropores of biochar and increases the abundance of O-containing functional groups, primarily carbonyl (C=O) and hydroxyl (–OH) groups[46].

Chemical activation

-

The chemical activation of biochar significantly enhances the adsorptive and structural properties of raw biochar. It is generally performed by mixing biochar with activating agents, such as acids (e.g., H2SO4 and HNO3) and alkalis (e.g., KOH and NaOH)[47]. Chemical activation typically involves mixing biochar with chemical agents, followed by thermal treatment. This process dehydrates the biochar and increases carbonization, there by promoting the formation of pores, including nanopores and functional groups[48]. After activation, the residual chemicals are removed by washing with deionised water, and the surface pH may be adjusted using acid or basic solutions[42]. The physicochemical properties of chemically activated biochar are affected by the chemical reagent[49].

Acid activation enhances the surface properties of biochar by introducing additional O-containing functional groups, while improving the surface area. Acidic agents facilitate the formation of carbonyl and hydroxyl groups on the biochar's surface by oxidising aromatic rings and aliphatic chains[50]. In addition, acid hydrolysis induces dehydration and degradation, leading to the formation of ketones and other carbonyl-containing functional groups[51]. For instance, Wang et al.[52] demonstrated that HNO3 activation effectively improved the specific surface area and enriched the presence of O-containing functional groups, such as carboxyl and carbonyl groups, in swine manure biochar.

Activation with alkaline agents improves the surface properties of biochar by introducing O-containing functional groups and imparting basicity to its surface[53]. These modifications provide ionic exchange sites that facilitate the removal of pollutants, including anionic species and heavy metals, from wastewater[54]. For example, KOH activation promotes the formation of functional groups such as hydroxyl (R–OH), carbonyl (C=O), alkene (C=C), and aromatic structures[55]. In addition, Wang et al.[52] reported that KOH-modified swine manure biochar exhibited a significantly higher surface area than pristine biochar.

Metal-impregnated biochar

-

Metal and metal oxide impregnation promotes the development of biochar's properties such as surface area[56] and functional groups, thereby improving its adsorption capacity[57,58]. Metal impregnation is performed using a dissolved metal solution containing metal salts (e.g., MgCl2, AlCl3, and FeCl3) and/or metal oxides (e.g., MnO, ZnO, and FeO). This process is typically achieved by mixing the precursors with biomass before pyrolysis for in-situ activation, or by impregnating the produced biochar followed by thermal treatment for post-pyrolysis activation[47]. Among metal salts/oxides, iron impregnation has gained significant interest owing to its nontoxic nature, stable adsorption performance, and ease of separation from wastewater using an external magnetic field[59]. Notably, Fe-impregnated biochar exhibits particularly stable adsorption behaviour for the removal of heavy metals. This effectiveness is attributed to the chelation of Fe3+ ions with surface functional groups, which facilitates the formation of metal oxides that are critical in the removal of heavy metal ions[60].

Comparison of modification methods

-

Balancing performance enhancement with practical viability, including operational convenience, cost, and technical feasibility, is essential when determining modification methods for manure-derived biochar. Physical modification of manure-derived biochar is technically convenient because of its simplicity, scalability, and minimal chemical requirements, making it suitable for large-scale applications. The key advantages include lower operational costs compared with chemical methods, reduced environmental risks from reagent use, and ease of integration into existing pyrolysis systems. However, physical modification generally requires higher activation temperatures and longer processing times, which increase energy consumption[61], and its ability to introduce new functional groups is limited, often necessitating an additional chemical or metal impregnation step for targeted contaminant removal. Moreover, some methods, such as oxygen/air activation, can lead to uncontrolled carbon loss and random pore development. Overall, physical modification offers high technical feasibility and operational convenience but is less effective than chemical routes in tailoring the surface chemistry for specific applications.

Chemical modification of manure-derived biochar can substantially improve the surface functionality, porosity, and adsorption performance by introducing O-containing functional groups (e.g., –COOH, –OH, C=O) and altering the pore structures[62]. Acid treatments are effective in removing mineral impurities and enhancing the affinity for cationic pollutants, whereas alkaline treatments can dissolve ash, unblock pores, and increase adsorption sites for both metals and oxyanions[63]. These methods offer high-performance gains and allow adjustment of the surface chemistry, making them technically feasible for targeted pollutant removal. However, they require the use of chemical reagents, corrosion-resistant equipment, and substantial post-treatment washing to remove residual chemicals, which generates large volumes of wastewater and increases the operational costs[47]. Additional expenses stem from purchasing and storing chemical agents, as well as neutralising spent solutions. Because of these environmental and safety considerations, they demand greater caution than physical modification methods.

Metal modification of manure-derived biochar is achieved either by in situ impregnation of the feedstock before pyrolysis or post-pyrolysis impregnation. In situ methods integrate chemical loading and thermal activation into a single step, reducing handling and energy use, while post-pyrolysis methods offer better control over the metal's distribution at the cost of increased complexity and additional thermal treatment[47]. Key advantages include the ability to impart targeted functionalities, such as magnetic recovery using Fe-based biochars or improved oxyanion removal with Mg-, Al-, or Mn-modified biochars[60]. However, these methods' large-scale feasibility is constrained by potential reductions in surface area caused by pore blockage and the risk of corrosion from acidic solutions. In addition, the modification process generates metal-containing wastewater that demands dedicated post-treatment facilities, and ensuring uniform metal loading on the biochar requires greater operational expertise. Thus, while technically viable for high-value applications in treatment facilities with an appropriate infrastructure, metal modification is generally less practical than simpler physical or alkaline activation methods.

In summary, physical modification is the most practical choice for large-scale, low-cost manure biochar production, offering simple integration, low environmental impact, and minimal operational hazards. Alkaline and acid treatments yield substantial performance improvements while requiring more advanced infrastructure and careful waste management. Metal modification provides high selectivity and additional functionalities for specific applications, but its implementation requires specialised expertise. Considering the advantages and disadvantages of each method, the optimal approach should be selected according to the specific end-use, the available technical capacity, and the balance between improved performance and operational feasibility.

-

Conventional water treatment processes commonly use activated sludge because of its cost-effectiveness. Although this method efficiently removes most organic pollutants, recalcitrant compounds persist because of their resistance to microbial degradation[64]. Consequently, these pollutants are discharged into the surrounding environment, where they persist and accumulate over time. Among the recalcitrant organic pollutants, dyes and antibiotics are considered representative compounds because of their complex molecular structures, such as azo (–N=N–) bonds and aromatic rings, which contribute to their inherent resistance to degradation[65]. The chemical structures and properties of typical dyes and antibiotics are presented in Table 3. Indeed, dyes and antibiotics in the environment seriously threaten human health and ecological systems through bioaccumulation and disruption of biological processes. Therefore, it is crucial to implement strategies to reduce the wastewater concentration of these substances prior to discharge.

Table 3. Chemical structures and properties of dyes (methylene blue, methyl orange, and malachite green) and antibiotics (tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, and levofloxacin)

Class Chemical Molecular formular Structure Molecular weight (g mol–1) λmax (nm) Ref. Dye Methylene blue C16H18ClN3S

319.85 672 [66] Methyl orange C14H14N3NaO3S

327.33 467 [66] Malachite green C52H56N4O12

364.91 614 [67] Antibiotics Tetracycline C22H24N2O8

444.435 359 [68] Levofloxacin C18H20FN3O4

361.368 289 [69] Ciprofloxacin C17H18FN3O3

331.346 277 [70] Industrial applications of dyes in sectors such as textiles, dyeing, paints, pharmaceuticals, and papermaking have expanded with industrialisation and improvements in living standards. However, this increased use has led to the generation of dye-containing wastewater. However, the structural diversity and complexity of dyes hinder their effective removal by some wastewater treatments, including coagulation, sedimentation, and biological treatment[71]. The presence of dyes can disrupt aquatic ecosystems by blocking sunlight, which inhibits photosynthetic organisms such as algae and aquatic plants, thereby reducing dissolved oxygen levels in the water[72]. Moreover, dyes possess diverse toxic properties that pose significant risks to human health and the environment, such as neurological disorders, organ toxicity, DNA damage, and adverse effects on aquatic organisms[73,74].

Antibiotics are antimicrobial agents that inactivate bacteria or inhibit their growth and reproduction. However, the extensive and indiscriminate use of antibiotics in various sectors, including human medicine, veterinary practices, agriculture, livestock, poultry, and aquaculture, has led to significant release of these drugs into the environment. Additionally, the chemical stability and resistance to complete metabolism of pharmaceuticals often result in their incomplete removal from wastewater[75]. Antibiotic contamination is predominantly observed in water sources, including surface water, groundwater, sediments, soil, and drinking water[76]. Antibiotics pose considerable risks to living organisms and environmental health. In living organisms, they can cause organ toxicity, allergic reactions, and gut microbiota disruption[77,78]. Environmentally, antibiotics are toxic to aquatic organisms, inhibit algal growth, and disrupt the ecological balance by affecting nontarget species[77,79]. In addition, their presence in water fosters genetic mutations and promotes the emergence of antibiotic-resistant pathogenic bacteria[80]. The major sources and the health and environmental impacts of the representative dyes (methylene blue [MB], methyl orange [MO], and malachite green [MG]) and antibiotics (tetracycline [TC], ciprofloxacin [CIP], and levofloxacin [LEV]) are summarised in Table 4.

Table 4. The major pollution sources and adverse effects of representative dyes (methylene blue, methyl orange, and malachite green) and antibiotics (tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, and levofloxacin) on human health and the environment

Class Chemical Source of pollutants Human health Environmental hazard Ref. Dye Methylene blue Industrial: textile, paint, paper, cosmetics, plastic, leather manufacturing, food processing,

and the pharmaceutical industryCyanosis, Heinz body, eye irritation, tachycardia, delirium, jaundice, tissue necrosis, gastrointestinal disturbances (nausea, vomiting, gastritis, and diarrhoea) Growth inhibition (microalgae), pigment formation (microalgae), aquatic ecosystem imbalance [81] Methyl orange Industrial: textile, paint, paper, leather manufacturing, food processing, printing, and the pharmaceutical industry Teratogenesis, mutagenesis, carcinogenesis, eye irritation, hypersensitivity, allergies, dermatitis, tachycardia, cyanosis, jaundice, quadriplegia, tissue necrosis, gastrointestinal disturbances (vomiting and diarrhoea) Growth inhibition (bacterial), water colouration, sunlight penetration reduction, photosynthesis disturbance, reduction in dissolved oxygen and gas solubility, eutrophication [72,82] Malachite green Industrial: textile, paper, cosmetics, plastic, leather manufacturing, food processing, and the pharmaceutical industry

Aquacultural: fungicide

and antiseptics for aquacultureTeratogenesis, mutagenesis, carcinogenesis, respiratory

issues, chromosomal aberrationsGrowth inhibition (bacterial, plant, and animal), genotoxicity, cytotoxicity, reproduction disturbance, mitochondrial dysfunction [83] Antibiotics Tetracycline Hospital wastewater treatment plants

Industrial: pharmaceutical manufacturing

Agricultural: livestock excreta, agricultural fertiliser, and aquacultureDisturbs intestinal microflora, allergies, kidney and liver dysfunction, chromosomal aberrations, reproductive issues, tooth discolouration, gastrointestinal disturbances, intracranial hypertension, skin infections (rosacea), inhibition

of protein synthesisGenetic mutation, emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, impact on nontarget organisms, aquatic ecosystem imbalance [76−78] Ciprofloxacin Hospital wastewater treatment plants

Industrial: pharmaceutical manufacturing

Agricultural: livestock excreta, agricultural fertiliserGenotoxicity, gastrointestinal disturbances (bleeding), leukopenia, neurological

disorders, allergiesGenotoxicity, cytotoxicity, oxidative stress induction, emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, growth inhibition (plant), toxicity to cyanobacteria [79,84] Levofloxacin Wastewater treatment plants Industrial: pharmaceutical manufacturing Hormonal imbalance, reproductive toxicity, respiratory issues, carcinogenesis Growth inhibition (algal), phytotoxicity, embryotoxicity, enhancement of plasmid transformability, toxicity to aquatic organisms (bacterial, plant, and animal) [75] Inorganic pollutants

-

Inorganic pollutants, particularly heavy metals, have become increasingly prevalent in the surrounding environment, primarily because of anthropogenic activities such as mining, industrial discharges, and agricultural practices. Heavy metals are highly soluble in aquatic environments and exist primarily as cations and oxyanions[60]. However, heavy metals are not biodegradable, which results in their persistence in the environment. The accumulation of heavy metals in the soil, groundwater, and surface water poses a serious risk to ecosystems. Moreover, their nonbiodegradability allows them to bioaccumulate throughout the food chain, leading to toxic effects on living organisms[85]. Exposure to heavy metals such as Pb, Cu, and Cd can result in substantial physiological damage, including liver toxicity, neurological disorders, and dermatological conditions[86]. Additionally, given the complex and unpredictable behaviour of aquatic environments, effective strategies for removing heavy metals from these ecosystems remain limited. The major sources and adverse effects of representative heavy metals (Pb, Cu, and Cd) on human health and the environment are summarised in Table 5.

Table 5. The major pollution sources and adverse effects of representative heavy metals

Metal Source of pollutants Human health Environmental hazard Ref. Pb Industrial: steel, battery, pigment, paint, paper manufacturing, mining, smelting, electroplating, and petroleum refining Agricultural: pesticides and fertilisers Gastrointestinal disturbances, kidney and liver dysfunction, neurological disorders (anaemia), reproductive toxicity, cognitive impairment − [87] Cu Industrial: steel, brass, pigments, paint, explosives manufacturing, mining, smelting, metallurgy, metal finishing, electroplating, and petroleum refining

Agricultural: pesticides and fertilisersGastrointestinal disturbances (nausea, vomiting, and bleeding), kidney and liver dysfunction, neurotoxicity, reproductive

issues (Wilson’s disease), headacheInhibition of microbial activity, affects earthworms, slows decomposition of organic matter [88,89] Cd Industrial: electronics, electrode, battery, paint, ceramics manufacturing, mining, metallurgy, electroplating, and welding Gastrointestinal disturbances, kidney and

liver dysfunction, neurological effects (anosmia), reproductive issues (urolithiasis), bone fragility, and carcinogenesisGrowth inhibition (plant), metabolism inhibition, photosynthesis disturbance, reduction of agricultural productivity [90,91] Mobility of heavy metals in aqueous solutions

-

The pH of an aqueous solution influences the distribution of heavy metal species and the efficiency of their adsorption onto biochar. At a low pH, heavy metals tend to exist predominantly as free ions, which are more soluble and mobile. These positively charged heavy metal ions are easily attracted to negatively charged biochar surfaces through electrostatic interactions, enhancing their adsorption capacity. As the pH increases, heavy metals may form hydroxide complexes that are less soluble and mobile. Within this pH range, biochar can effectively remove heavy metals through surface precipitation or complexation, thereby enhancing their immobilisation. Therefore, optimising the pH of an aqueous solution is crucial for maximising the adsorption capacity for heavy metal removal[92]. Furthermore, understanding the speciation changes in heavy metals as a function of pH is important. Pb predominantly exists as Pb2+ at pH < 6, Pb(OH)+ at pH 6–9, Pb(OH)2 at pH 9–12, and Pb(OH)3– at pH > 12[93]. The prevalent species of Cu at pH < 6 are Cu2+ and Cu(OH)+ whereas at pH > 6, it is Cu(OH)2[94]. The dominant Cd species at pH < 8 is Cd2+ and those in the range of 8–11 are Cd2+, Cd(OH)+, Cd(OH)2(aq), and Cd(OH)3– [95]. The primary Zn species are Zn2+ and Zn(OH)+ at pH < 10 and Zn(OH)2(aq), Zn(OH)3–, and Zn(OH)42− at pH > 10[96].

-

Organic pollutants are the most pervasive and detrimental contaminants affecting water quality worldwide. These pollutants, originating from diverse sources, such as industrial waste, agricultural runoff, and household waste, pose considerable challenges to environmental safety and public health[97]. In particular, nonbiodegradable dyes and antibiotics cause significant environmental challenges, including toxicity to aquatic organisms, inhibition of algal growth, and disruption of the ecological balance[74,77,79]. They are bio-refractory organic substances that can be harmful to aquatic organisms and human health. Therefore, the management and control of water contamination by organic dyes and antibiotics are critical. Among the existing wastewater treatment methods, adsorption has attracted attention for its ability to remove organic pollutants from wastewater.

Mechanisms of organic contaminant adsorption

-

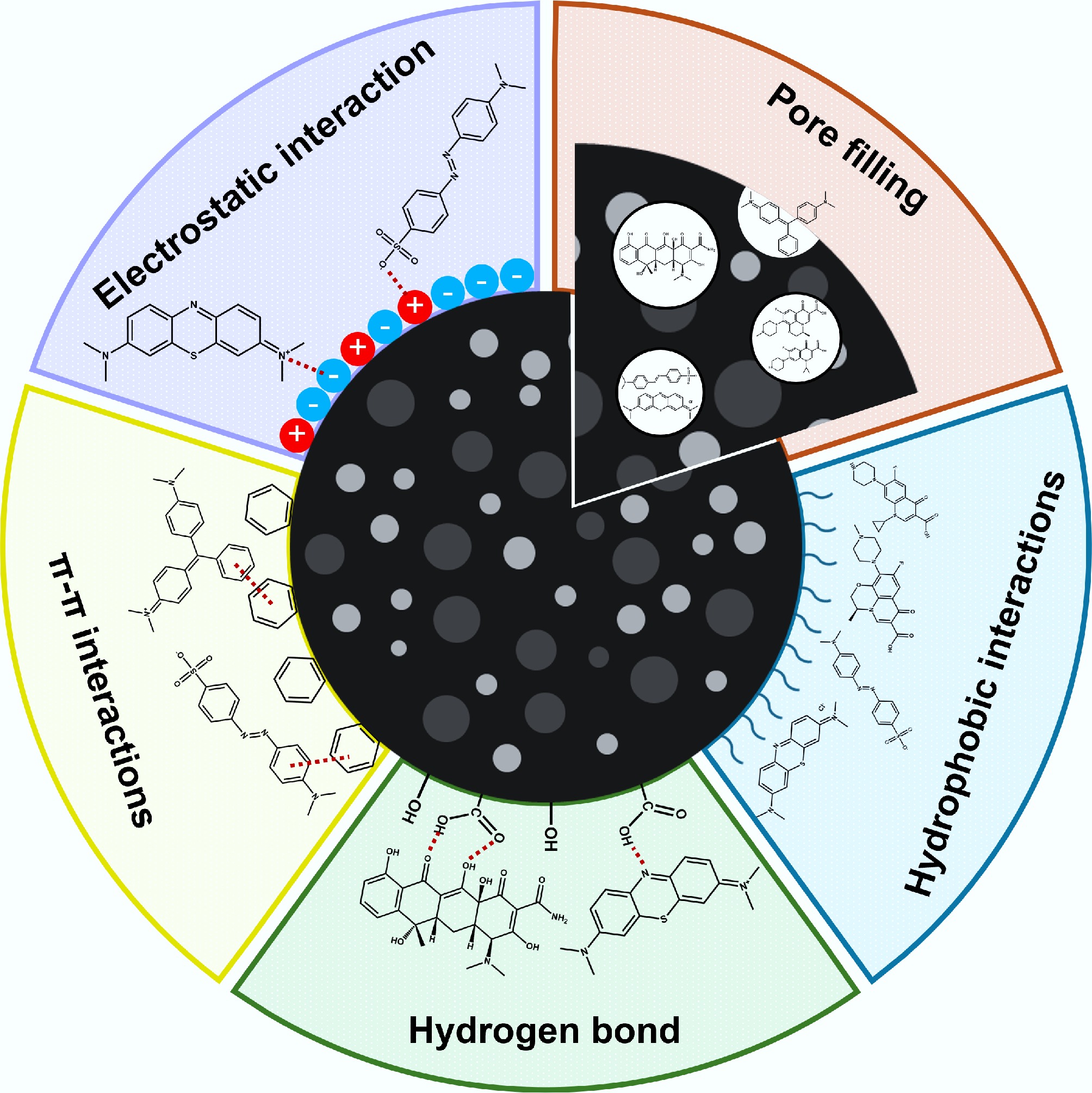

The adsorption of organic contaminants by manure biochar is driven by physical and chemical mechanisms. The porous properties of biochar, including its surface area, pore volume, and pore diameter, enable physical adsorption through hydrophobic interactions, van der Waals interactions, and pore filling. Chemically, O-containing functional groups (e.g., –COOH, –OH, =O) on the biochar's surface form hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions, whereas aromatic C domains mediate π–π electron donor–acceptor interactions[98]. Additionally, the mineral components inherent in manure biochar (e.g., Ca2+ and Mg2+) facilitate surface precipitation through complexation with ionic pollutants or chelation of organic compounds. The combined effects of these mechanisms allow manure-derived biochar to immobilise diverse organic pollutants effectively. Fig. 3 shows the different adsorption mechanisms of organic contaminants on biochar.

Physical adsorption mechanisms

Hydrophobic interactions and van der Waals forces

-

The hydrophobic interactions in biochar are primarily attributed to the attraction between its nonpolar surface and hydrophobic organic contaminants[99]. The nonpolar surface of biochar results from C-rich and aromatic C structures within the biochar matrix. Therefore, biochar's hydrophobicity significantly influences its adsorption capacity for hydrophobic and neutral organic contaminants in wastewater. Van der Waals forces in biochar-based adsorption involve weak, transient dipole-induced interactions between the nonpolar C-rich surfaces of biochar and the hydrophobic contaminants[100]. These interactions are facilitated by fluctuations in the electron distribution, which generate instantaneous dipoles[101]. Hydrophobic interactions and van der Waals forces can be enhanced by developing aromatic C structures and increasing the biochar's surface area[102]. The desired modifications can be accomplished by increasing the pyrolysis temperature, which facilitates carbonisation and graphitisation while increasing the accessibility of adsorption sites on the biochar's surface. Tsui & Roy[103] investigated the adsorption capacity of compost-derived biochar for atrazine, a hydrophobic organic compound, and observed that the adsorption capacity increased with the pyrolysis temperature across a range from 320 to 720 °C. This increase was attributed to the enhanced hydrophobicity resulting from the decrease in O content of the biochar. Hydrophobic interactions and van der Waals forces synergise with pore-filling mechanisms, whereby contaminants are physically located within the pores.

Pore-filling

-

Pore-filling is a key adsorption mechanism whereby contaminants are physically retained within the porous network of biochar because of their size compatibility. Since the pore-filling process depends on the pore size of the biochar, enhancing its porosity and surface area is crucial because it provides a more accessible adsorption area[104]. Porosity and surface area are particularly significant in biochars produced at high pyrolysis temperatures. In addition, because pore-filling in biochar is primarily governed by hydrophobic interactions and van der Waals forces, a nonpolar surface further enhances its adsorption capacity[105]. The surface's nonpolarity can be evaluated by assessing the atomic H/C ratio. Wei et al.[106] reported that when the H/C ratio decreased below 0.5, the contribution of pore-filling to the overall adsorption of herbicides increased significantly. This finding is supported by a study by Wang & Jang[107], who investigated LEV adsorption using swine manure-derived biochar. Using a dual-mode adsorption model, their study demonstrated that pore-filling dominates in biochar produced at higher pyrolysis temperatures. The dual-mode model reflects preferential interactions between the solutes and the pore-filling domains within the biochar matrix[106]. Elevated pyrolysis temperatures improved the pore structure, as reflected by the higher specific surface area, pore volume, and mean pore diameter, and decreased the H/C ratio, collectively amplifying the role of pore-filling in the adsorption of recalcitrant organic pollutants. Although pore-filling dominates under these conditions, it is important to recognise that physical and chemical adsorption processes occur simultaneously. Therefore, a comprehensive investigation of the chemical adsorption mechanism of biochar is essential to fully understand its adsorption behaviour.

Hydrogen bonds

-

Hydrogen bonds refer to the electrostatic attraction between a hydrogen atom bonded to an electronegative atom (such as N, O, or F), and another electronegative atom in other molecules. Hydrogen bonding is primarily driven by the partial positive charge of hydrogen, induced by electronegative atoms, which enables electrostatic attraction with the neighbouring electronegative atoms[108]. Biochar typically contains abundant O-containing functional groups such as hydroxyl (–OH), carboxyl (–COOH), carbonyl (–C=O), and amine (–N-H) groups[109]. These functional groups can act as hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, facilitating strong and selective interactions with pollutants bearing complementary functional moieties[110]. Consequently, organic compounds that contain complementary functional groups, including dyes, pharmaceuticals, and pesticides, can be effectively adsorbed onto biochar via hydrogen-bonding interactions. Zhuo et al.[111] demonstrated that the adsorption mechanism of TC on Ca-modified corn stover biochar was caused by hydrogen bonding between the O-containing functional groups (C–O and O–C=O) on the biochar and the complementary functional groups of TC molecules.

Chemical adsorption mechanisms

Electrostatic interactions

-

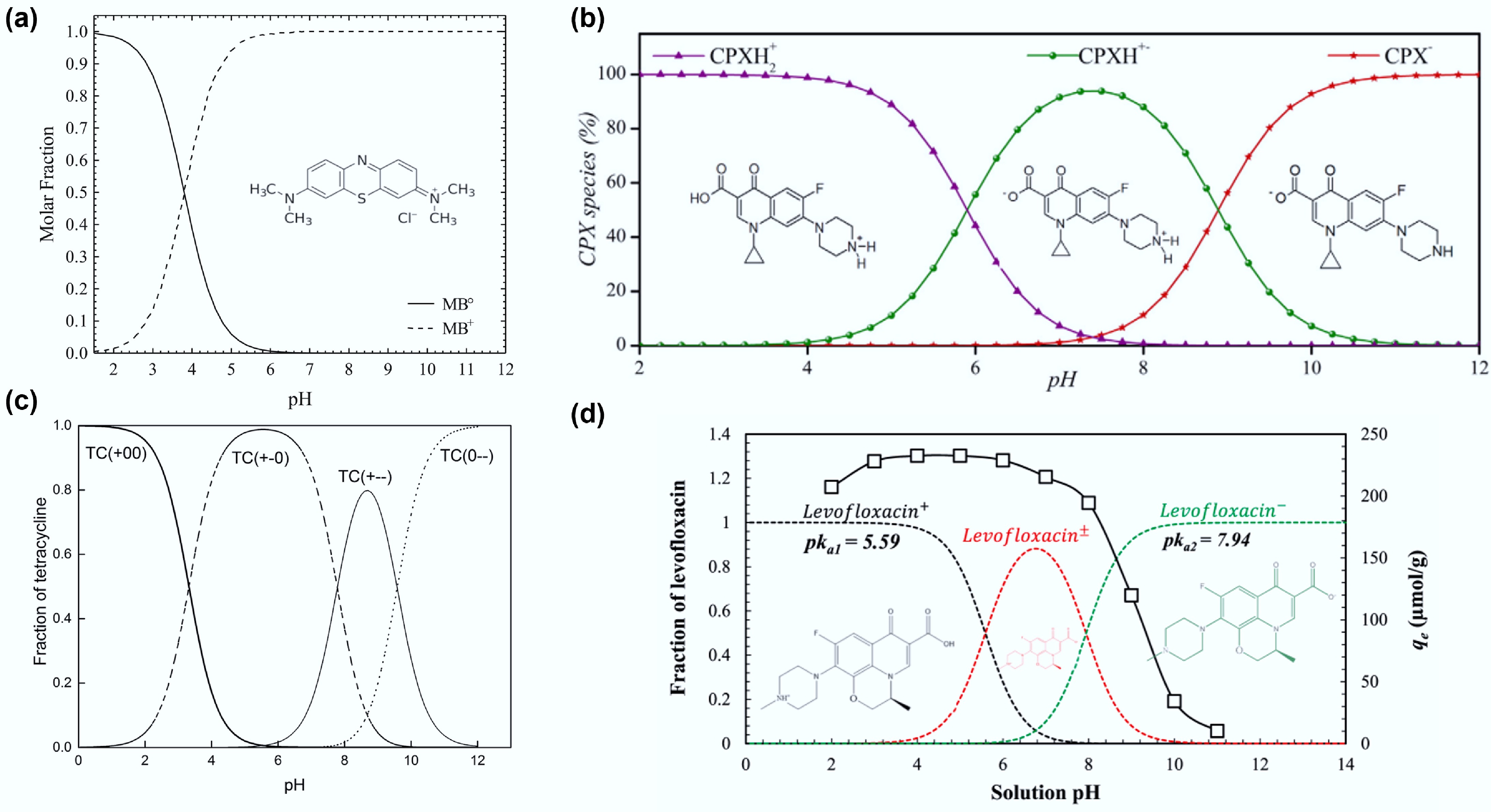

Electrostatic interactions in biochar adsorption refer to the attraction between the charged sites on the biochar's surface and oppositely charged pollutant molecules. Biochar's surfaces typically exhibit a net negative charge, primarily owing to the presence of O-containing functional groups such as carboxyl and hydroxyl groups. This negative surface potential promotes the adsorption of positively charged species, including metal ions and certain cationic pollutants. The strength and selectivity of the electrostatic interactions are governed by factors such as the ash content and the abundance and type of surface functional groups[112]. In addition, the solution's pH has a significant influence on the electrostatic interactions by modifying the surface charge of the biochar. A key concept in this context is the point of zero charge (pHpzc), at which the biochar surface exhibits a net neutral charge owing to an equal balance of positive and negative surface charges[113]. When the solution's pH is below the pHpzc, the biochar surface acquires a net positive charge, favouring the adsorption of negatively charged species (anions). In contrast, when the pH exceeds the pHpzc, the surface adopts a negative charge, facilitating the adsorption of positively charged species (cations). This transition in the surface charge with increasing pH can be attributed to the deprotonation of functional groups, which leads to a more negatively charged surface[114]. In addition to the charge characteristics of biochar, the ionic nature of the target pollutants significantly influences the electrostatic interactions[115]. For example, the efficiency of removing MB, a cationic dye, improves with an increase in pH (from 2 to 10) because the negatively charged surface of biochar at an elevated pH enhances the electrostatic attraction[116]. The adsorption capacity of biochar for TC tends to decrease with an increase i pH, as TC becomes negatively charged at higher pH levels (TC+ at pH < 3.3, TC0 at pH 3.3−7.7, TC− at pH 7.7−9.7, and TC2− at pH > 9.7)[117]. This results in electrostatic repulsion between the negatively charged TC and similarly charged surfaces of the biochar[118]. Figure 4 shows the distribution of recalcitrant organic pollutant species as a function of the pH value[119−121].

Figure 4.

Distribution of (a) methylene blue (reprinted from Salazar-Rabago et al.[119] with the permission of Elsevier), (b) ciprofloxacin (reprinted from Roca Jalil et al.[122] with the permission of Elsevier), (c) tetracycline (reprinted from Wang et al.[120] with permission; copyright 2018 Royal Society of Chemistry), and (d) levofloxacin (reprinted from Shaha et al.[121] with the permission of Elsevier) at different pH values.

The π−π EDA interaction

-

The π−π EDA interaction or π−π stacking is primarily driven by electrostatic attraction arising from differences in electron density between π-systems. In these interactions, an electron-rich π-system (donor) engages with an electron-deficient π-system (acceptor) via orbital overlap and charge transfer, resulting in attractive forces. The electron-rich π-system typically stems from the incorporation of electron-donating groups (e.g., hydroxyl and amine groups) into a conjugated structure (e.g., aromatic rings), whereas the electron-deficient π-system is formed by the presence of electron-withdrawing groups (e.g., carboxylic acid, nitro, and ketone groups)[100]. Biochar typically possesses O-containing functional groups, including hydroxyl (–OH) and carbonyl (–C=O) groups, attached to aromatic rings, which can serve as electron acceptors and facilitate π–π EDA interactions[123]. These interactions are particularly pronounced with organic pollutants that exhibit complementary π-systems, such as pharmaceuticals and dyes (Table 3)[124]. Accordingly, to enhance the adsorption capacity of biochar for organic pollutants via π–π EDA interactions, implementing activation treatments is crucial. These treatments introduce or modify the surface functional groups that impart suitable electron-donating or electron-accepting characteristics, depending on the target contaminants.

Adsorption of dyes

-

Dyes are used extensively in various industries, resulting in the discharge of wastewater containing residual dyes. Because of their complex molecular structures, dyes are resistant to conventional treatments such as coagulation, sedimentation, and biological processes. Their persistence in aquatic environments disrupts photosynthesis, reduces O levels, and poses toxic risks to ecosystems and public health[125]. Consequently, adsorption has gained increasing attention as an effective method for removing recalcitrant organic pollutants from wastewater. Table 6 presents dye adsorption from wastewater by animal manure biochar. The adsorption of dyes by biochar is largely attributed to the functional groups present on its surface, which facilitate various interactions with the dye molecules[109].

Table 6. Application of animal manure biochar for dye adsorption

Target Adsorbent Pyrolysis and activation conditions Surface area (m2 g−1) Total pore volume (cm3 g−1) Average pore diameter (nm) Ash content (wt.%) H/C ratio O/C ratio Qmax

(mg g−1)Ref. Methylene blue Bovine Biochar: 500 °C for 3 h 17.50 [126] Methylene blue Sheep Biochar: 500 °C for 2 h 160.53 0.172 10.03 17.82 0.037 0.244 202.72 [127] Methylene blue Rabbit Biochar: 500 °C for 2 h 21.14 0.041 8.64 15.38 0.064 0.165 86.85 [127] Methylene blue Swine Biochar: 500 °C for 2 h 13.36 0.025 7.33 13.14 0.128 0.079 46.95 [127] Methylene blue Bovine Biochar: 200 °C 0.3276 0.00613 75.02 192.31 [133] Methyl orange Chicken Biochar: 600 °C for 2 h 39.47 [128] Methyl orange Sheep Biochar: 600 °C for 2.5 h 181.76 0.245 0.035 0.191 42.51 [129] Malachite green Sheep Biochar: 450 °C 11.731 208.33 [130] Methylene blue Swine Biochar: 700 °C for 2 h;

Activation: alkali fusion pretreatment of fly ash209.1 0.369 7.10 0.43 142.86 [135] The viability of animal manure biochar as an adsorbent for dye removal was demonstrated in a comparative study by Ahmad et al.[126]. This investigation focused on removing MB from an aqueous solution using biochar produced from bovine manure, rice husks, and sludge. Compared with that of rice husk and sludge biochar, bovine manure biochar demonstrated consistently high MB removal efficiency, maintaining a removal rate of 97.0%–99.0% across a pH range of 2.0–11.0. This high efficiency is likely attributable to the abundance of carboxyl (–COO) groups and the larger pore size on the surface of bovine manure biochar, providing active sites for adsorption.

The properties of manure vary depending on the animal species, which, in turn, influence the surface properties of the resulting biochar. Therefore, comparative analyses of the adsorption capacity of biochar derived from the manure of various animals are required. Huang et al.[127] evaluated the adsorption performance of three manure biochars (sheep, rabbit, and swine manure) for the removal of MB from aqueous solutions. The surface area, pore volume, and pore size of sheep manure biochar (160.53 m2 g−1, 0.172 cm3 g−1, and 10.03 nm, respectively) were larger than those of rabbit (21.14 m2 g−1, 0.041 cm3 g−1, and 8.64 nm, respectively) and swine manure biochar (13.36 m2 g−1, 0.025 cm3 g−1, and 7.33 nm, respectively). Furthermore, sheep manure biochar demonstrated a higher O/C ratio and a lower H/C ratio than rabbit and swine manure biochars. These characteristics indicate that sheep manure biochar offers more adsorption sites for MB, and its greater polarity and aromaticity enhance physical and chemical adsorption mechanisms, including pore-filling, electrostatic interaction, hydrogen bonding, and π−π EDA interactions. Sheep manure biochar exhibited a higher adsorption capacity for MB (202.729 mg g−1) than rabbit (86.852 mg g−1) or swine manure biochar (46.958 mg g−1).

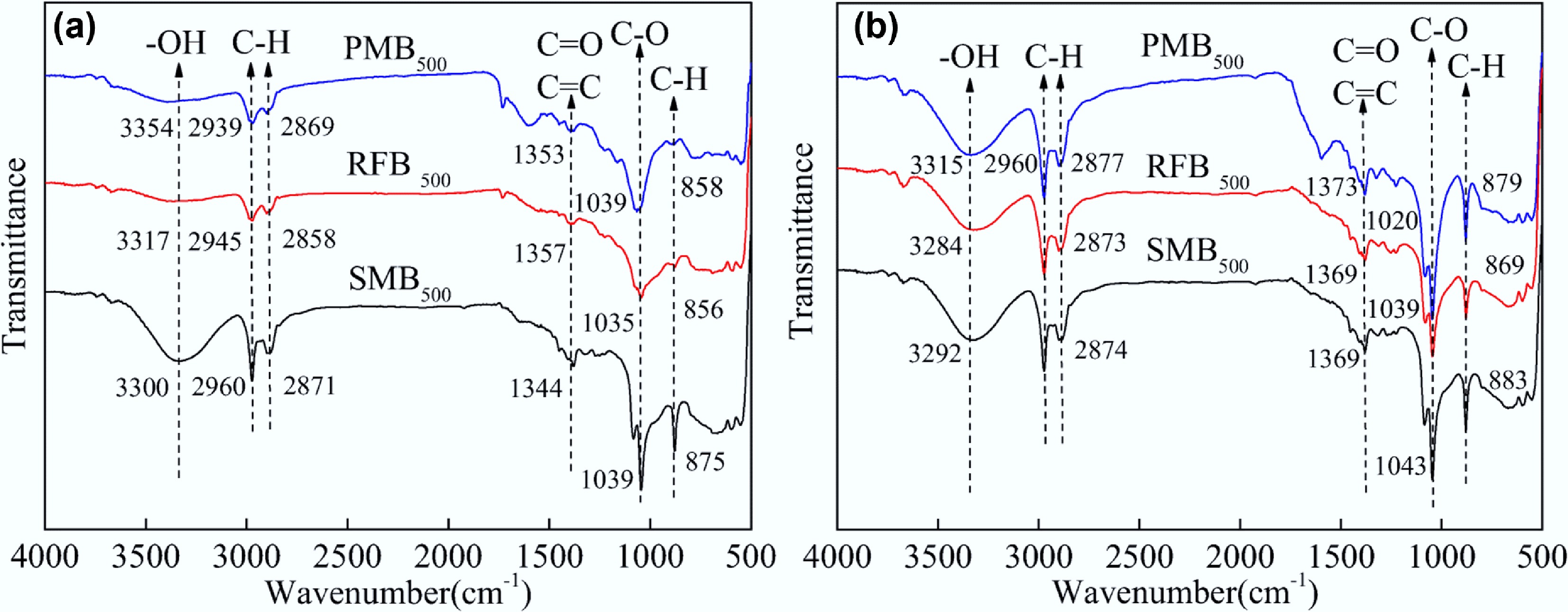

In recent years, studies on the adsorption-based treatment of MO in wastewater have increased. Nevertheless, research investigating the use of manure biochar as an adsorbent for MO remains limited. Yu et al.[128] investigated the adsorption of MO using chicken manure biochar, pyrolyzed at 600 °C for 120 min, and reported a maximum adsorption capacity of 39.47 mg g−1. Similarly, Lu et al.[129] evaluated sheep manure biochar produced at 600 °C for 150 min, which demonstrated a higher MO adsorption capacity of 42.51 mg g−1. These results indicate that the adsorption capacity of MO using sheep manure biochar was more significant than that of chicken manure biochar. This is consistent with MB removal, and sheep manure biochar showed greater adsorption performance than other animal manure biochars. This enhanced performance may be attributed to the higher plant fibre content in sheep manure, which likely contributes to the greater specific surface area and higher content of O-containing functional groups in the resulting biochar (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

FT-IR spectra of pig (blue), rabbit (red), and sheep (black) manure biochar (a) before and (b) after adsorption of methylene blue. Reprinted from Huang et al.[127] with the permission of Springer Nature.

The detailed adsorption mechanisms of using sheep manure biochar as an adsorbent were studied by Dilekoğlu[130] with MG. The biochar was produced at 450 °C, and the maximum adsorption capacity was 208.33 mg g−1. To investigate the adsorption mechanism of MG, changes on the biochar surface were observed using Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy. After the adsorption of MG, the FT-IR spectra of the biochar showed shifts in the –OH and C–H peak regions. This indicated the involvement of multiple interactions, including electrostatic attraction between MG and –the OH groups, hydrogen bonding between the N-heterocyclic ring of of MG and the –OH groups, and π−π EDA interactions between the aromatic rings of MG and the C–H groups[131]. These findings are consistent with the thermodynamic parameters of MG adsorption, with a calculated change in enthalpy of 56,674 kJ mol−1. Notably, the value of > 60 kJ mol−1 suggests that chemical adsorption is the predominant mechanism governing this process[132].

Adsorption parameters such as the solution's pH and biochar's surface properties were investigated to optimise the performance of biochar for organic pollutant removal. Notably, the solution's pH affects the ionisation state of the biochar's surface and the pollutants, thereby altering the electrostatic interactions and adsorption capacity. Dilekoğlu[130], using sheep manure biochar, demonstrated that the capacity to adsorb MG, a cationic dye, reached equilibrium at high pH values (≥ 4 pH). This was attributed to competition between the MG and excess hydrogen ions for adsorption sites under acidic conditions. When the solution's pH exceeded the pHpzc of the biochar, the surface became negatively charged, which enhanced the electrostatic attraction between the biochar and MG. In contrast, Yu et al.[128] reported that chicken manure biochar exhibited a higher adsorption capacity for MO, an anionic dye, under acidic conditions. Notably, at an elevated pH, competition from hydroxide ions (OH−) reduces the adsorption of MO. Furthermore, under acidic conditions, protonation of the surface functional groups (e.g., –OH2+ and –NH3+) promotes the electrostatic attraction of anionic MO. Optimising the solution's pH according to the ionic nature of the target dye is critical for maximising the adsorption performance.

Surface properties, such as surface area, porosity, and the abundance of functional groups, are key factors governing the availability of adsorption sites on biochar and, consequently, their overall adsorption capacity. The pyrolysis temperature significantly influences these properties, thereby affecting the adsorption capacity. Zhu et al.[133] investigated the effect of the pyrolysis temperature on the adsorption capacity of bovine manure biochar for MB. As the temperature increased from 200 to 800 °C, the surface area and pore volume of the biochar increased from 0.3276 m2 g−1 and 0.00613 cm3 g−1 to 3.627 m2 g−1 and 0.0107 cm3 g−1, respectively. However, the pore size decreased from 75.02 to 12.979 nm. Interestingly, despite exhibiting a greater specific surface area and higher porosity, bovine manure biochar produced at 800 °C showed lower adsorption performance than that produced at 200 °C. This could be attributed to the substantial loss of O-containing functional groups, including carboxyl, lactonic, and phenolic groups, at elevated pyrolysis temperatures. These functional groups are critical for facilitating various adsorption mechanisms such as electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and cation exchange.

In addition to modifying the operational parameters, the activation of biochar to enhance its adsorption capacity for dye removal was also investigated. This is commonly achieved through impregnation with iron oxide, manganese oxide, or alkaline earth metals[134]. This treatment improved the specific surface area, porosity, and the number of O-containing functional groups on the biochar's surface. Wang et al.[135] modified swine manure biochar using alkali-fused fly ash (AFFA) to increase its capacity for MB adsorption. This modification improved the surface area and porosity of the swine manure biochar. Furthermore, it preserved O-containing functional groups, such as –OH and C=O, at a pyrolysis temperature of 700 °C. The abundant O-containing functional groups, along with the aromatic structure of AFFA-activated biochar facilitate multiple adsorption mechanisms, including π–π EDA interactions, electrostatic interactions, and hydrogen bonding. Notably, the aromatic structure increases with increasing pyrolysis temperature. Additionally, the notable concentration of Na+ in the activated swine manure biochar potentially contributed to its ion exchange capacity. Consequently, AFFA-activated swine manure biochar exhibited a 10.7%–112.3% increase in MB adsorption capacity.

Dye removal by animal manure biochars is driven by electrostatic interactions, π–π EDA interactions, and hydrogen bonding, with the relative contribution of each mechanism determined by both the ionic nature of the dye and the surface chemistry of the biochar. In unmodified biochars, electrostatic attraction occurs between oppositely charged dye molecules and the biochar's surface, π–π EDA interactions arise from the association between aromatic dye structures and graphitic domains in the biochar, and hydrogen bonding is facilitated by O-containing functional groups such as –OH and –COOH. Among various feedstocks, sheep manure biochar consistently achieves higher adsorption capacities for MB, MO, and MG because of its greater specific surface area and higher O/C ratio compared with other animal manures. The pH-dependent behaviour reflects the charge characteristics of the dye, with cationic dyes such as MB and MG exhibiting maximum adsorption when the surface is negatively charged (pH > pHpzc,). In contrast, anionic dyes such as MO show higher adsorption under acidic conditions through protonation of the surface's functional groups. Given the inherently high ash content of manure, which imparts alkalinity, manure-derived biochar tends to be more suitable for cationic dye adsorption. In alkali-metal-modified biochars, enhanced dye removal performance is achieved through increased surface area, porosity, and O-containing functional groups, which intensify hydrogen bonding and π–π EDA interactions, while alkaline metals introduced during activation can contribute to additional ion exchange mechanisms.

Adsorption of antibiotics

-

Antibiotics are antimicrobial agents used across the human, veterinary, and agricultural sectors, which has led to their widespread release into the environment. Their chemical stability and incomplete metabolism hinder their removal during conventional wastewater treatment, resulting in contamination of surface water, groundwater, soil, and sediment. These compounds pose significant risks to living organisms by causing organ toxicity, allergic reactions, and disruption of gut microbiota. In the environment, antibiotics harm aquatic organisms, suppress algal growth, and disturb the ecological balance by affecting nontarget species[136]. Moreover, their persistence in water promotes genetic mutations and accelerates the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria[137]. Therefore, the development of effective treatment strategies, such as biochar-based adsorption, is essential for mitigating antibiotic contamination in aquatic environments. Antibiotics adsorption from aquatic environments using animal manure biochar is presented in Table 7.

Table 7. Applications of animal manure biochar for the adsorption of antibiotics

Target Adsorbent Pyrolysis and activation conditions Surface area (m2 g–1) Total pore volume (cm3 g–1) Average pore diameter (nm) Ash content

(wt.%)H/C ratio O/C ratio Qmax

(mg g–1)Ref. Tetracycline Swine Biochar: 600 °C for 2 h 10.56 0.044 12.36 0.05 0.250 8.125 [120] Tetracycline Bovine Biochar: 700 °C 5.82 [117] Tetracycline Swine Biochar: 700 °C for 2 h 319.04 0.25 43.9 0.01 0.06 160.3 [142] Activation: 14% H3PO4 solution for 24 h at 25 °C Levofloxacin Swine Biochar: 900 °C for 2 h 512.11 0.51 4.008 18.39a 0.014 0.093 158.07 [107] Ciprofloxacin Rabbit Biochar: 700 °C for 2.5 h 91.52 0.237 12.64 19.06 0.032 0.276 57.626 [140] a After acid washing. Understanding the adsorption mechanism is essential for optimising the adsorption capacity of antibiotics. Wang et al.[120] investigated TC adsorption on swine manure biochar and compared it with that on rice straw biochar. The adsorption data fitted both the Freundlich and Langmuir models well, suggesting the involvement of both physical and chemical mechanisms[138]. In particular, a strong correlation between the specific surface area and Langmuir adsorption capacity was observed. However, the poor fit of the Temkin model and the weak correlation with O-containing functional groups suggest that electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonding were not dominant[109]. Higher adsorption capacities were observed at pH 3.5–8.0, where TC exists as a zwitterion and interacts with the negatively charged biochar surface via π–π EDA interactions. The conjugated enone structure of TC acts as a π-electron acceptor, whereas the graphite-like biochar serves as a π-electron donor[139]. These findings suggest that π–π EDA interactions are crucial in the adsorption of TC onto swine manure biochar. These results are consistent with those of Zhao et al.[117], who investigated the TC adsorption mechanisms of bovine manure biochar at pyrolysis temperatures ranging from 500 to 700 °C. An increase in the pyrolysis temperature improved the maximum adsorption capacity of the bovine manure biochar. However, this was accompanied by a reduction in the number of surface functional groups, including acidic, phenolic hydroxyl, carbonyl, and lactone groups. This suggests that the primary mechanisms responsible for the adsorption of TC by bovine manure biochar were hydrophobic interactions and π–π EDA interactions. Nevertheless, given that TC contains multiple O-containing functional groups, the overall adsorption capacity remained low, suggesting that activation strategies aimed at enriching the surface functional groups of manure-derived biochar are essential.

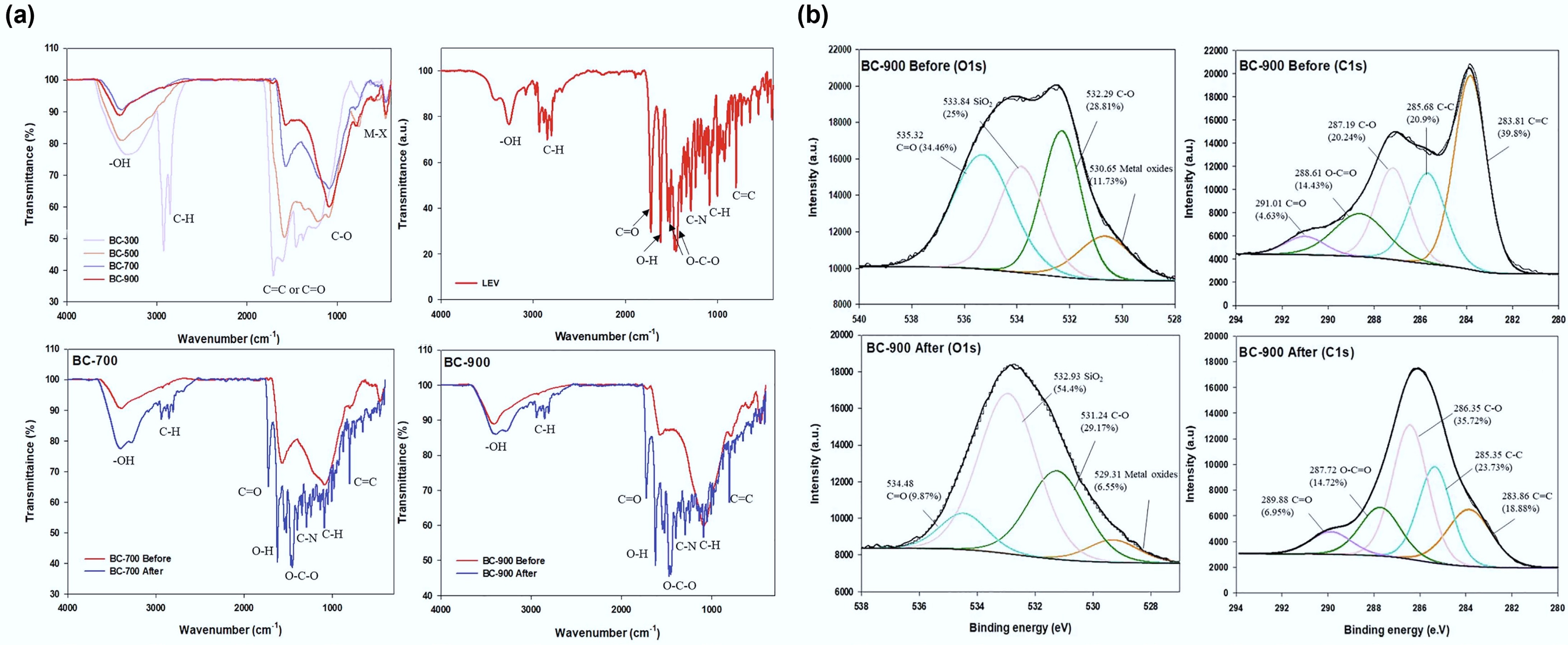

Similarly, Wang & Jang[107] conducted an investigation on LEV's adsorption mechanism using swine manure biochar produced at pyrolysis temperatures ranging from 300 to 900 °C. The highest adsorption capacity (158 mg g–1) was achieved with swine manure biochar produced at 900 °C. To evaluate the adsorption behaviour and maximum capacity, five isotherm models, namely, the Langmuir, Freundlich, Temkin, Dubinin–Radushkevich, and dual-mode models, were employed. The results indicated that LEV's adsorption onto high-temperature swine manure biochar followed a multilayer adsorption pattern involving chemical mechanisms, such as electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding, cation−π, and π−π EDA interactions, and physical mechanisms, including pore-filling (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

(a) FT-IR spectra and (b) X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra (O1s and C1s) of swine manure biochar before and after adsorption of levofloxacin. Reprinted from Wang & Jang[107] with the permission of Elsevier.

Additionally, Huang et al.[140] investigated the removal mechanism of CIP using rabbit manure biochar (RMB) produced at pyrolysis temperatures ranging from 400 to 700 °C. RMB produced at 700 °C exhibited the highest adsorption capacity (70.17 mg g–1) for CIP. Isothermal and thermodynamic analyses revealed that the adsorption behaviour was better described by the Langmuir model, indicating monolayer adsorption[138]. The enthalpy change (ΔH = 31.88 kJ mol–1) suggested that hydrogen bonding was the primary adsorption mechanism[141], involving interactions between the N-containing heterocyclic ring, –COOH, and −F groups in CIP and the O-containing functional groups on RMB. Indeed, as the pyrolysis temperature increased, the degree of graphitisation and aromaticity in RMB also increased, enhancing π−π EDA interactions. These π−π interactions were facilitated by the electron-accepting groups in CIP (−COOH and −F) and the π-electron-donating sites in RMB (e.g., C−H in aromatic structures).

Animal manure biochar exhibits a limited surface area, pore structure, and functional group availability because of the inherent characteristics of the raw material, which constrain its maximum capacity to adsorb antibiotic compounds. Therefore, the modification of animal manure biochar has been investigated to enhance its capacity to adsorb antibiotics. Chen et al.[142] modified swine manure biochar using acid (14% H3PO4) for adsorbing TC. This modification increased the surface area from 227.56 to 319.04 m2 g–1, and the pore volume from 0.14 to 0.25 cm3 g–1. Additionally, H3PO4 modification enhanced the O-containing functional groups (–COOH and –OH) on the biochar's surface[143]. After H3PO4 modification, the adsorption capacity of swine manure biochar increased. In conclusion, the enhanced TC adsorption was attributed primarily to chemisorption mechanisms, including hydrogen bonding and π−π EDA interactions.

Animal manure biochar effectively adsorbs TC, with optimal performance observed at pH 3.5–8.0 where TC exists as a zwitterion. Adsorption occurs mainly via π−π EDA interactions between the conjugated enone structure of TC and the aromatic domains of biochar. Higher pyrolysis temperatures enhance hydrophobicity, which strengthens π−π EDA interactions and increases the adsorption capacity despite the loss of acidic and phenolic groups. Nevertheless, due to the presence of numerous O-containing functional groups in TC, adsorption using manure-derived biochar is negligible. As such, surface modification is necessary. Surface modification with H3PO4 further improves TC adsorption by increasing the surface area, enhancing the O-containing functional groups, and promoting hydrogen bonding alongside π−π EDA interactions. For LEV, swine manure biochar pyrolysed at 900 °C achieved the highest adsorption capacity, with removal governed by multilayer chemical and physical mechanisms including electrostatic attraction, hydrogen bonding, cation–π interactions, π−π EDA interactions, and pore filling. Rabbit manure biochar produced at 700 °C exhibited the highest adsorption capacity for CIP, characterised by monolayer adsorption dominated by hydrogen bonding between CIP functional groups (–COOH, –F, N-heterocycles) and O-containing sites on the biochar's surface, supplemented by π−π EDA interactions enhanced by greater aromaticity at higher temperatures. The differing properties of each antibiotic result in distinct adsorption mechanisms. Therefore, biochar should be tailored to the specific characteristics of each antibiotic.

-

Heavy metals are prevalent pollutants in wastewater, primarily originating from industrial activities such as battery production, electroplating, and mining. Their nonbiodegradable nature and high toxicity render them hazardous to humans, animals, and plants, even at low concentrations. Consequently, various treatment technologies, including redox processes, chemical precipitation, and membrane separation, have been developed for their removal. Among these methods, adsorption has gained attention because of its technical simplicity and low cost[144]. Biochar is considered a promising adsorbent owing to its high porosity, high surface activity, and the abundance of functional groups. However, its adsorption capacity depends on factors such as the type of heavy metal and the pyrolysis conditions, highlighting the need for performance evaluation for targeted applications.

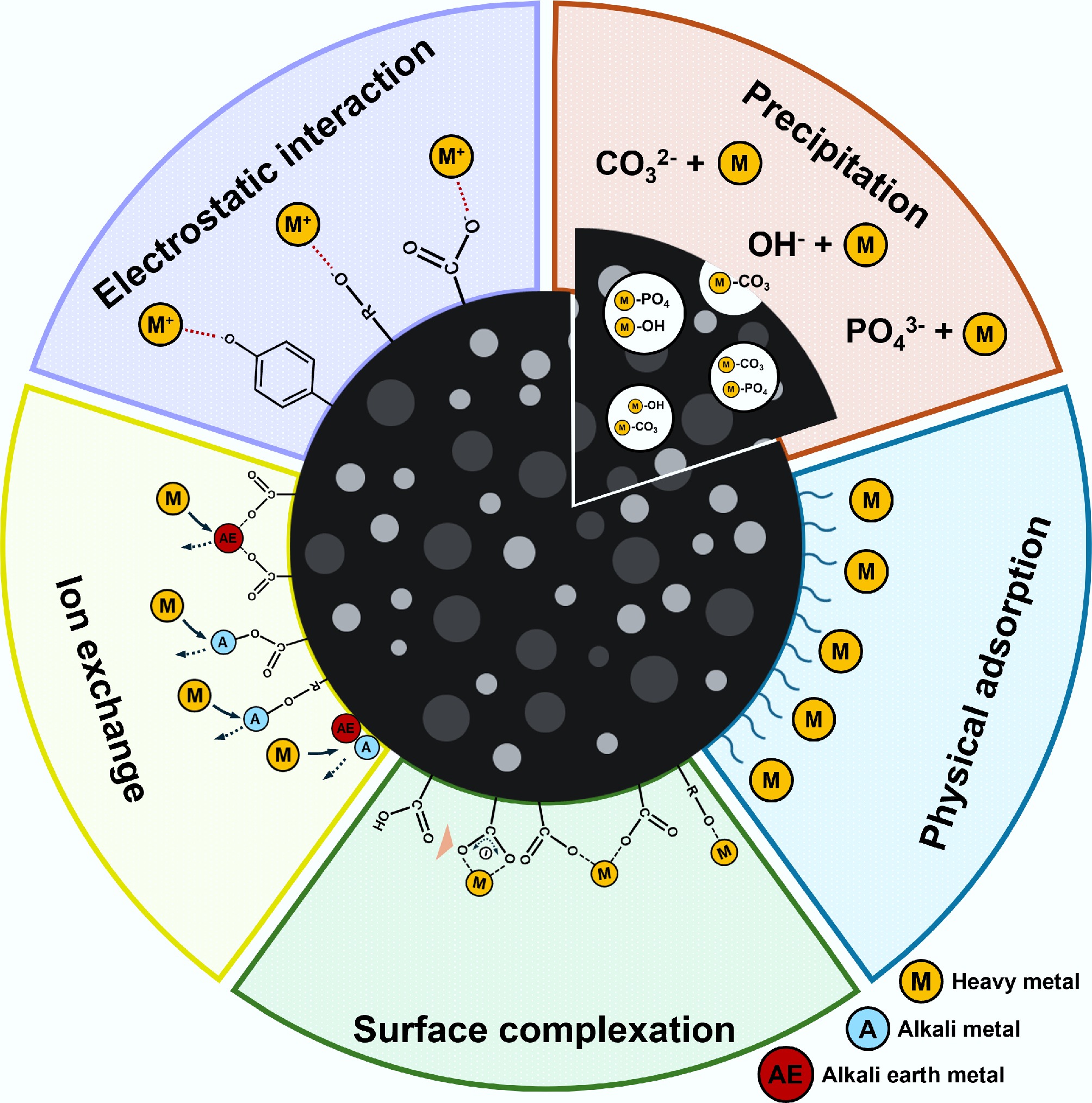

Mechanisms of heavy metal adsorption

-

Adsorption of heavy metals by biochar involves a combination of various mechanisms, including physical adsorption, electrostatic interactions, precipitation, ion exchange, and surface complexation (Fig. 7)[144]. The predominant adsorption mechanisms can vary depending on the target metals and physicochemical properties of the biochar.

Physical adsorption

Hydrophobic interactions and van der Waals forces

-

The physical adsorption mechanism of heavy metals onto biochar primarily involves nonspecific interactions, particularly van der Waals forces, existing between the surface of the biochar and the heavy metal ions[145]. Biochar typically possesses a porous structure with a large surface area that allows metal ions to diffuse into its pores. Generally, the efficiency of physical adsorption is strongly determined by the pore size distribution and surface area of the biochar[146]. Accordingly, increasing the porosity and surface area of the biochar may improve its capacity to adsorb heavy metal ions. However, physical adsorption is typically not the dominant mechanism for used heavy metal adsorption because of its relatively weak adsorption affinity compared with chemical adsorption. For instance, Xu et al.[147] reported that rice husk biochar, despite having a larger surface area (27.8 m2 g–1) than dairy manure biochar (5.61 m2 g–1), exhibited five times lower adsorption capacities for Pb(II), Cu(II), Cd(II), and Zn(II). This suggests that chemical interactions play a more influential role in heavy metal adsorption.

Chemical adsorption

Electrostatic interaction

-

Electrostatic interactions refer to attractive forces that occur between the surface charges on the biochar and heavy metal ions[148]. In particular, negatively charged biochar, resulting from the presence of O-containing functional groups, such as carboxylic (–COOH), hydroxyl (–OH), and phenol (Ar–OH) groups, can effectively attract heavy metal cations, including Pb2+, Cd2+, and Cu2+, in wastewater[149]. Considering that the charge on the biochar's surface and metal ions varies with solution pH, the effectiveness of the electrostatic interactions is highly dependent on the pH. For instance, when the solution's pH exceeds pHpzc, the functional groups in biochar undergo deprotonation[150]. This results in the biochar imparting a negative charge, which facilitates its ability to attract positively charged metal ions via electrostatic interactions. Although electrostatic interactions contribute to adsorption, they are relatively weak compared with other mechanisms such as precipitation, ion exchange, and surface complexation, which play a more significant role in heavy metal adsorption. These processes involve stronger chemical interactions, leading to more stable and irreversible binding of metal ions. In this context, these mechanisms contribute significantly to the overall adsorption capacity and efficiency.

Precipitation

-

The precipitation of heavy metals involves the formation and subsequent deposition of insoluble metal compounds within biochar's pores during the adsorption process. This process involves the reaction between metal ions and anions, including hydroxides (OH–), carbonates (CO32–), or phosphates (PO43–), released from the biochar, leading to the formation of precipitates[151]. The proposed precipitation reaction of Cu(II) is shown in Eqs. (1) and (2)[152]. Thus, manure biochar is a viable option because it contains soluble PO43– and CO32–, which promote the precipitation of heavy metals and enhance its adsorption capacity[153]. For instance, Cao et al.[154] observed an increase in Pb phosphate precipitates on a bovine manure biochar's surface, accompanied by a decrease in PO43–. This suggests that Pb(II) was removed via the formation of Pb phosphate precipitates on the biochar.

$ 3{{\mathrm{Cu}}}^{2+}+2{{{\mathrm{PO}}}_{4}}^{3-}\to {{\mathrm{Cu}}}_{3}{\left({{\mathrm{PO}}}_{4}\right)}_{2}\downarrow $ (1) $ {{\mathrm{Cu}}}^{2+}+{{{\mathrm{CO}}}_{3}}^{2-}\to {\mathrm{Cu}}{{\mathrm{CO}}}_{3}\downarrow $ (2) Ion exchange

-

Ion exchange is an adsorption mechanism in which exchangeable cations present on the surface of biochar, such as H+, Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+, are replaced by heavy metal ions from wastewater. This process is primarily driven by the tendency of metal ions with higher charge densities and/or smaller hydration radii to replace these cations[155]. To enable this mechanism, the presence of both ion-binding sites, i.e., O-containing functional groups and exchangeable cations, is essential. Accordingly, biochar with these characteristics is highly conducive to facilitating ion exchange processes[156].

Surface complexation

-

Surface complexation involves the removal of heavy metals from a solution by forming multiatom complexes (inner- and outer-sphere complexes) between heavy metal ions and ligands[157]. Atoms such as S, N, and O in the functional groups act as ligands[158]. This indicates that the abundant O-containing groups, such as carboxyl and hydroxyl groups, on a biochar's surface can serve as adsorption sites for heavy metal ions[159].These ligands act as electron donors, whereas the heavy metal ions function as electron acceptors[160]. This mechanism involves covalent or ionic coordination bonds between metal ions and surface ligands. Chemical binding (covalent bonding) leads to the formation of inner-sphere complexes, whereas electrostatic binding (ionic coordination) results in outer-sphere complexes[161].

Adsorption characteristics for different heavy metals

Pb(II) adsorption

-

Pb pollution is a global issue caused by mining, smelting, battery manufacturing, and industrial wastewater discharge. Despite these regulations, improper disposal of Pb-containing waste continues to contaminate water bodies and landfills. Global Pb production has increased by 232% in recent decades, reaching 11.3 million tons annually, contributing to widespread wastewater contamination[162]. Pb(II) is highly toxic and nonbiodegradable, posing serious health risks—particularly to children and pregnant women—and affecting multiple organ systems[85]. As such, regulatory agencies have established strict limits, with the World Health Organization (WHO) and the European Union permitting a maximum concentration of 10 µg L–1 in drinking water[87,163]. Physicochemical treatment methods are commonly adopted to reduce Pb concentrations in wastewater. However, they are often associated with high costs, the generation of secondary waste, and the use of hazardous chemicals. Therefore, biochar has gained attention as a promising, low-cost, and environmentally friendly alternative for removing Pb(II) from wastewater. Therefore, numerous studies have investigated the adsorption of Pb(II) from aqueous solutions using animal manure biochar (Table 8).

Table 8. Applications of animal manure biochar for adsorption of Pb(II)

Adsorbent Pyrolysis and activation conditions Surface area (m2 g–1) Total pore

volume (cm3 g–1)Average pore diameter (nm) Ash content (wt.%) pH H/C ratio O/C ratio Qmax

(mg g–1)Ref. Bovine Biochar 500 °C for 150 101 [164] Chicken Biochar: 800 °C for 2 h 64.63 10.1 0.04 0.83 242.57 [166] Chicken Biochar: 550 °C for 2 h 7.09 7.09 87.2 9.95 0.06 0.49a 120.383b [167] Yak Biochar: 350 °C for 2 h 6.36 23.91 1.2 0.55 155.36 [170] Activation: 10% H2O2 solution at room temperature Bovine Biochar: 300 °C for 4 h 25.94 0.055 27.13 9.98 0.15 0.92 175.53 [92] Activation: 2 M NaOH (shaking for 12 h at 65 °C) Swine Biochar: 500 °C;

Activation: Fe2+ and Fe3+ solutions (stirred for 20 min at 20–25 °C)225.08 [52] a Calculated from the results of a proximate analysis of biochar; b The molecular weight of Pb(II) was assumed to be 207 g mol–1. The viability of animal manure biochar for Pb(II) adsorption was demonstrated by Xu et al.[164]. This research utilised biochar produced at 500 °C from bovine manure and rice straw as adsorbents. To elucidate the adsorption mechanism of Pb(II) on biochar, surface analysis was performed, which revealed the formation of Pb-containing precipitates, such as PbCO3, Pb3(CO3)2(OH)2, and Pb5(PO4)3Cl, after adsorption. These precipitates are attributed to the CO32– and PO43– originating from the inorganic constituents of the biochar. To further investigate the mechanism, the inorganic and organic fractions of the biochar were separated, and adsorption experiments were conducted on each fraction independently. The results showed that approximately 99% of Pb(II) adsorption was attributable to the inorganic fraction. Visual MINTEQ modelling confirmed that precipitation was the dominant mechanism. Bovine manure biochar exhibited a higher maximum adsorption capacity (101 mg g–1) than rice straw biochar (70 mg g–1), which was attributed to the higher carbonate and phosphate ion contents in bovine manure biochar. These findings indicate that animal manure biochar, particularly bovine manure biochar, is a highly effective adsorbent for removing Pb(II) from aqueous solutions.

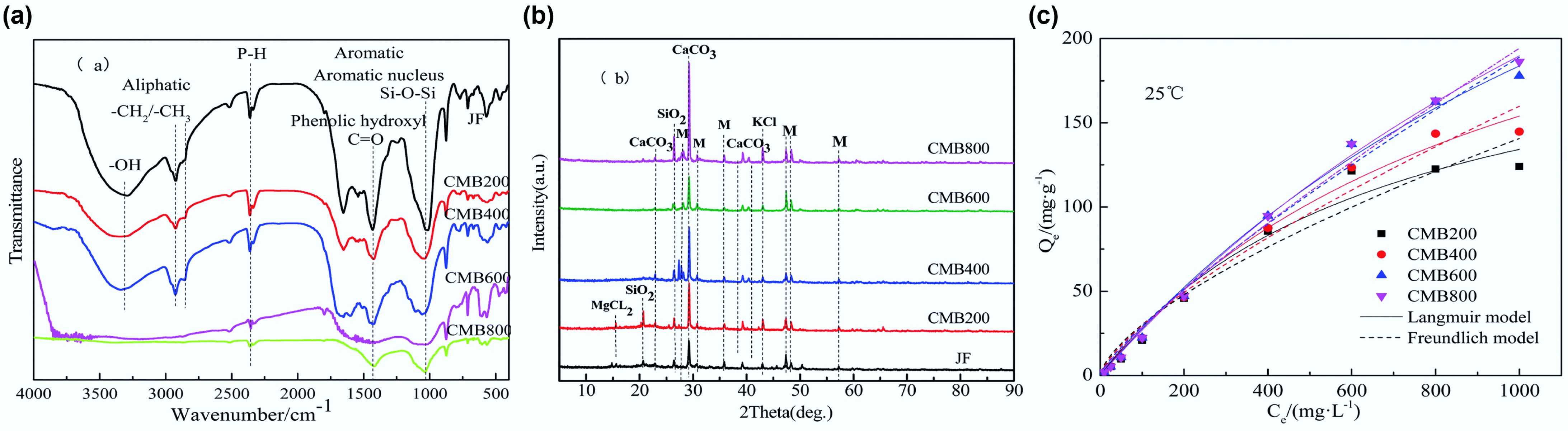

Pyrolysis temperature plays a crucial role in determining the physicochemical properties of biochar, including its surface area, pore volume, and ash content[165]. These characteristics subsequently affect the adsorption capacity of biochar and the mechanisms of heavy metal removal. Yan et al.[166] demonstrated the effect of pyrolysis temperature on the adsorption performance of chicken manure biochar for removing Pb(II). The maximum adsorption capacity of Pb(II) increased with the pyrolysis temperature, reaching 242.57 mg g–1 at 800 °C. The adsorption data fitted the Langmuir isotherm model better than the Freundlich model, indicating that Pb(II) adsorption follows a monolayer and is primarily driven by chemical interactions. Considering that the functional groups on the biochar decreased with an increase in pyrolysis temperature while the ash content increased, ion exchange and precipitation appear to be the dominant mechanisms of Pb(II) removal (Fig. 8). The role of precipitation has been demonstrated in bovine manure biochar. In the case of ion exchange, Zhao et al.[167] demonstrated its effectiveness by releasing alkaline metals, specifically Ca2+ and Mg2+, when chicken manure biochar was used as an adsorbent for Pb(II).

Figure 8.

(a) FT-IR and (b) XRD spectra of chicken manure biochar and as a function of temperature and (c) their adsorption isotherm curves. Reprinted from Yan et al.[166] with permission. Copyright 2019 Royal Society of Chemistry

Biochar produced at high pyrolysis temperatures typically shows an increased surface area, microporosity, and ash content[165]. Studies have confirmed that the adsorption of Pb(II) is enhanced by increasing the pyrolysis temperature. However, the high energy demand for increasing the pyrolysis temperatures highlights the necessity for low-temperature alternatives owing to their energy efficiency and economic feasibility[168]. However, biochar produced at low temperatures typically exhibits a relatively low surface porosity[169]. Numerous studies have explored enhancing the Pb(II) adsorption capacity at low pyrolysis temperatures by activating biochar with oxidising agents, alkalis, or acids. Wang & Liu[170] reported that yak manure biochar activated using an oxidising agent serves as an adsorbent for Pb(II). To modify the yak manure biochar, H2O2 was employed, and the pyrolysis process was conducted at 350 °C. Following modification, the adsorption capacity of Pb(II) increased to 169.57 mg g–1, which was more than double that of pristine yak manure biochar. Additionally, the contents of O and carboxyl groups in yak manure biochar increased by 63.4% and 101%, respectively, whereas the ash content decreased by 42%. The reduction in the ash content after H2O2 modification led to diminished Pb precipitation, whereas the increased number of O-containing functional groups facilitated complexation, which became the dominant removal mechanism. This was further supported by the better fit of the yak manure biochar data to the pseudo-second-order kinetic model, indicating the involvement of inner-sphere complexation[171]. These findings suggest that H2O2-modified biochar can serve as an effective surface sorbent for removing heavy metals from aqueous solutions.

Chen et al.[92] investigated the effectiveness of alkaline activation for Pb(II) adsorption using bovine manure biochar. The biochar, pyrolysed at 300 °C and subsequently activated with sodium hydroxide (NaOH), showed a significant increase in adsorption capacity, reaching 175.53 mg g–1, compared with 51.32 mg g–1 for the pristine bovine manure biochar. The alkaline treatment process led to an increase in the specific surface area, ion-exchange capacity, and abundance of O-containing functional groups. The adsorption equilibrium data fitted the Langmuir isotherm model, indicating the dominance of monolayer adsorption via chemical mechanisms. Additionally, the formation of Pb precipitates (2Pb(CO3)·Pb(OH)) and the complexation of Pb(II) with carboxyl and hydroxyl functional groups were detected on the biochar's surface. These findings demonstrate that alkaline activation significantly improves the Pb(II) adsorption capacity of bovine manure biochar.

In Wang et al.[52], the surface area of iron-doped swine manure biochar (magnetic biochar, 225.08 m2 g–1) was higher than that of pristine biochar and acid/base-activated biochar, which provided more adsorption sites. After the magnetic treatment, iron oxide was introduced into the biochar, thus increasing the ash content and providing additional electrostatic adsorption sites and precipitation ability[172]. Consequently, the adsorption capacity for Pb(II) increased from 30.02 to 95.94 L mg–1. Additionally, they found that the adsorption rate of magnetic biochar was higher than that of acid/base-activated biochar. Although metal/metal oxide-impregnated animal manure biochar has a higher adsorption capacity for heavy metals than most crop residue biochars, few studies have focused on this approach.