-

In recent years, rural and urban areas worldwide have undergone unprecedented expansion and development. Reserved lands, including farmlands in rural regions, are increasingly being converted into residential and commercial buildings, alongside supporting infrastructure. Urban expansion is further driven by large-scale population migration. This trend aligns with projections: the United Nations[1] reported that the world's population reached 8 billion in 2022, with over half living in urban areas. This figure is projected to rise, with an estimated 70% of the global population expected to reside in cities by 2050. However, approximately 1.1 billion people currently live in slums or slum-like conditions, and this number is anticipated to surge to 2 billion over the next three decades.

The development of a city is often measured by progress in the transportation, construction, commercial, and industrial sectors[2]. These sectors have been reported to be the primary contributors to energy consumption, natural resource depletion and degradation, deforestation, and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Furthermore, it has been projected that global raw material consumption will nearly double by 2060; and as the global economy expands and living standards improve, this growth will double the current environmental burden[1]. Consequently, there is a clarion call to develop sustainable cities.

The core content of sustainability is the capacity to meet present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs[3]. This entails the sustainable utilization of natural resources, underpinned by the recognition that such resources are not infinite. Accordingly, sustainable cities must be designed and constructed to minimize adverse environmental impacts and promote a circular economy[4]. To achieve this, the adaptation of materials that can ultimately support the development of net-zero carbon cities is essential. Biochar, a carbon-negative substance, represents one such material. Biochar has been reported to sequester carbon dioxide (CO2), and significantly reduce carbon footprints when incorporated into engineering materials[5−7].

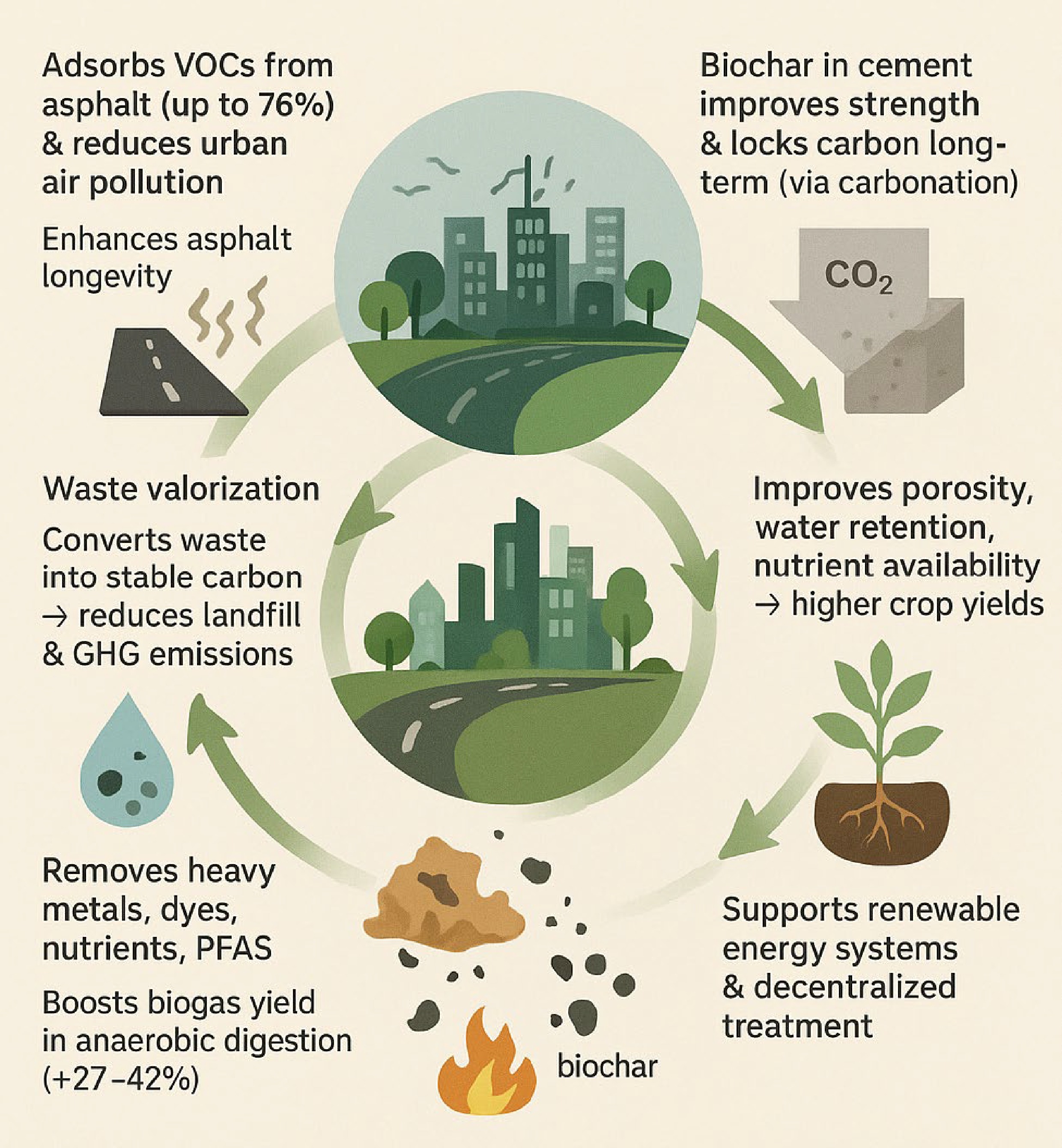

This review presents a novel perspective by synthesizing the multifaceted applications of biochar tailored specifically to the context of sustainable urban development—an area that remains relatively underexplored within the existing literature. Notably, in contrast to prior studies, which frequently concentrate on singular applications of biochar, such as soil enhancement or water treatment, this work uniquely integrates its diverse roles within the framework of circular economy principles for urban systems. Through the synthesis of global case studies from cities such as New York, Singapore, Beijing, Alexandria, and Tokyo, and by highlighting recent advancements in biochar modification techniques (e.g., chemical activation and metal impregnation), this review provides a comprehensive analysis of biochar's potential to address interconnected urban challenges.

-

Biochar is an innovative material derived from organic waste, specifically designed to address challenges and risks associated with environmental management and sustainable urban development. The term 'biochar' is a relatively recent term referring to bio-derived carbon or char derived from various feedstocks or biomass, with applicability across multiple domains[8]. However, the utilization of charcoal to improve soil fertility has been a longstanding practice in agriculture for thousands of years[9]. In air quality improvement, biochar has demonstrated effectiveness in adsorbing volatile organic compounds (VOCs), including both aromatic and non-aromatic pollutants, owing to its high surface area, porous structure, and adjustable surface chemistry through various modification methods[10,11]. In the construction sector, biochar functions as a sustainable cement substitute and asphalt additive, enhancing mechanical properties, aging resistance, and carbon sequestration potential while improving infrastructure durability and mitigating emissions[12,13]. For soil regeneration, its utility is well documented in improving soil structure, nutrient retention, and microbial activity, thereby fostering the sustainability of urban agriculture and green spaces[14,15]. Moreover, biochar's application in water and wastewater treatment has gained considerable attention, with proven efficacy in removing heavy metals, organic contaminants, dyes, nutrients, and emerging pollutants, alongside supporting microbial-mediated biodegradation processes[16,17]. Additionally, biochar acts as an additive in anaerobic digestion systems, accelerating methane production and bolstering process stability. It further supports the selective removal of methane from atmospheric or landfill sources by enhancing methane-oxidizing bacteria activity[18]. Collectively, these applications position biochar as a multifaceted material pivotal to the advancement of sustainable and resilient urban environments.

Sources and methods of producing biochar

-

Biochar can be produced using feedstocks derived from various biomass sources, with a preference for waste. These wastes encompass industrial by-products, municipal sewage sludge, household waste, as well as agricultural and forest residues. Notably, the agricultural sector has been identified as the largest contributor to waste generation[19]. It has been reported that approximately 998 million tonnes of agricultural waste are generated annually in developing countries. Organic waste constitutes an estimated 80% of the total solid waste in typical farm settings[20]. The produced biochar can be pristine (i.e., pure or undiluted) or subjected to modification, functionalization, or engineering via physical, chemical, and thermal alterations[21].

Numerous thermochemical conversion technologies are employed for biochar production from various biochar types, which are commonly referred to as feedstocks in the process. These technologies include combustion, gasification, pyrolysis, and liquefaction. Research findings have shown that the characteristics of the produced biochar are contingent on a multitude of factors, including biomass type, moisture content, particle size, reaction temperature, residence time, ambient conditions, reactor type, and catalysts used, among others[22]. A concise summary of the production requirements for these technologies is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Production requirements for some thermochemical conversion technologies of biomass

Production requirement Thermochemical conversion technologies of biomass Combustion Gasification Fast pyrolysis Torrefaction (slow pyrolysis) Liquefaction Pre-treatment of biomass Drying and appropriate particle sizes Drying and appropriate particle sizes Drying and appropriate particle sizes Wet processing under high pressure can be used without first drying Not required Moisture content in biomass < 50% < 30% < 10% Subjective > 90% Temperature range (°C) 800−1,000 800−1,200 400−500, low residence time and rapid cooling of the vapour (< 1 h) 200−350 and long reaction time 150−450 Pressure Not required Not required Not required Not required Pressurized solvent

1−240 barOxygen Require Partial oxidation or air atmosphere Not required Not required Not required Energy produced Direct use as heat Stored as chemical energy Stored as chemical energy Product (low grade charcoal) can be densified into pellets or briquettes to obtain higher energy density Liquid product Nayeripour & Kheshti[23] reported that the yields and characteristics of the products vary significantly across these thermochemical processes. Biomass gasification is optimized for syngas production, including carbon monoxide (CO), hydrogen (H2), carbon dioxide (CO2), and methane (CH4). However, this process typically yields only small quantities of biochar[24]. Products derived from gasification and combustion processes are characterized by low carbon content and high ash content, in contrast to products produced via pyrolysis and hydrothermal carbonization, which generally exhibit high carbon content and low ash content. Specifically, typical biochar yields are approximately 12%, 25%, and 35% for fast, intermediate, and slow pyrolysis, respectively[25]. Temperature and residence time are widely recognized as the primary determinants of biochar yield[26−28]. Kumar et al.[28] reported that ball milling, a mechanochemical activation technology, can be used to increase the fineness, reactivity, and specific surface area of biochar. Additionally, such engineered biochar has been shown to exhibit improved adsorptive, catalytic, and electrochemical properties.

Characteristics of biochar

-

Biochar exhibits substantial variability in its characteristics, which are significantly influenced by feedstock type and process conditions. The physical, chemical, and nutrient properties of biochar can be manipulated through the applied process to align with the intended end use. For example, temperature has been identified as a more influential factor on biochar properties than other production conditions. The increasing temperatures enhance surface area and pore size, which is beneficial for soil water retention, pH regulation, pollutant absorption, and prevention of nutrient leaching. Higher temperatures also increase oxygen and hydrogen content, resulting in biochar with enhanced hydrophobicity[29−32].

Unprocessed feedstocks exhibit high hydrogen-to-carbon (H/C) and oxygen-to-carbon (O/C) ratios, coupled with low resistance to degradation. However, when subjected to combustion, increases in temperature and heating time reduce H/C and O/C ratios, promoting the formation of a more aromatic structure in the resulting biochar. The resulting biochar resembles a graphite-like material, has lower H/C and O/C ratios, and is thus more stable and less prone to degradation[33,34].

-

As urban areas undergo ongoing expansion and confront mounting environmental challenges, the integration of sustainable practices into city planning has become imperative. Building on the foregoing discussion, biochar presents substantial potential to advance urban sustainability. Its applications span soil quality improvement in urban green spaces, stormwater management optimization, greenhouse gas emission mitigation, and the promotion of circular waste practices. By facilitating carbon sequestration and improving resource efficiency, biochar contributes to climate resilience, environmental health, and sustainable urban development. This section investigates the primary applications of biochar, including air quality improvement, carbon sequestration, waste valorization, soil regeneration, and water and wastewater management.

Air quality improvement

-

The sustained increase in VOCs and their detrimental impacts on human health and the environment have driven the establishment of the Gothenburg Protocol, a comprehensive regulatory framework aimed at reducing emissions. This protocol mandates a 50% reduction in VOC emissions relative to 2000 levels by 2020[35]. As of 2019, most of the 34 parties had not yet met their 2020 VOC emission reduction targets. Projections for 2030 indicate that several Parties will still require additional efforts to achieve these goals. Fulfilling VOC emission reduction commitments necessitates the implementation of supplementary policies and measures to ensure substantial progress by 2030. Key challenges include delays in policy implementation, activity levels exceeding expectations, slow replacement of outdated equipment, insufficient political will, and weak enforcement—particularly in sectors such as road transport, agriculture, and domestic wood combustion. Addressing these obstacles will demand intensified efforts to fulfill emission reduction targets[36]. One promising strategy involves the application of innovative materials. Biochar exhibits potential in removing VOCs from asphalt and acting as an inhibitor of VOC emissions[37−39]. Its effectiveness in adsorbing VOCs stems from several key properties, which can be further enhanced through various modification techniques.

The VOCs adsorption capacity of biochar is attributed to its high surface area, porous structure, and functional groups[11,40]. Understanding these properties is essential, as research has demonstrated that biochar's adsorption capacity for various VOCs can be significantly enhanced through specific modification. Biochar derived from different feedstocks has been shown to effectively capture both aromatic and non-aromatic VOCs through a combination of physical and chemical interactions. Treatment methods to enhance biochar's VOC removal efficiency include: chemical activation using alkali agents (e.g., KOH) and acidic agents (e.g., H2SO4) to increase surface area and pore volume[41], thereby improving adsorption capacity; thermal treatments or pyrolysis at varied temperatures to optimize pore structure and surface functional groups[42]; surface modification through acid treatments to introduce oxygen-containing functional groups (e.g., hydroxyl, carboxyl), enhancing chemical interactions with VOCs[43]; physical activation to develop microporosity tailored for selective VOC adsorption, and impregnation with metals or other catalysts to facilitate the catalytic degradation of certain VOCs[44]. These treatment approaches improve biochar's sorption performance by tailoring its physicochemical properties, such as porosity, surface chemistry, and adsorption affinity, making it more effective in removing aromatic and aliphatic VOCs from air and water. The effectiveness of these treatments has been validated across various feedstocks and VOC types, with considerations that optimal conditions depend on specific VOC molecular characteristics and mixture compositions.

In subsequent sections, the application of biochar in the removal of aromatic and non-aromatic VOCs, as well as the reduction of sulfur-containing VOCs, is briefly introduced.

Aromatic VOCs removal

-

Extensive research in recent years has unequivocally confirmed the effectiveness of biochar in removing aromatic VOCs. Detailed analyses of specific aromatic VOC reduction efficiencies consistently validate biochar's performance across various studies. For instance, Zhou et al.[37] demonstrated that biochar—particularly that derived from waste wood—can reduce emissions of specific VOCs (e.g., C15H30, C16H32, C19H40, and C21H44 by 50%. Zhang et al.[45] reported a significant improvement in benzoic acid degradation under UV light, with efficiency increasing from 78.7% to 95.2%. Similarly, Zhou et al.[46] observed substantial reductions in aromatic VOC emissions using rice husk-derived biochar, underscoring that biochar's origin and structure are critical determinants of its adsorptive capacity.

In the context of aromatic VOCs abatement, toluene and p-xylene are of particular concern due to their widespread usage and inherent toxicity. A study by Mosleha & Rajabi[11] investigating wheat straw- and hardwood-derived biochars revealed a significant improvement in adsorption capacities following chemical modification with NaOH and benzoic acid. Specifically, the toluene adsorption capacity increased from 32.5 mg/g (untreated wheat straw biochar) to 125.3 mg/g (modified version). For p-xylene, the capacity rose from 27.6 mg/g (untreated hardwood biochar) to 83.3 mg/g post-modification. These results underscore that chemical modifications substantially enhance biochar's affinity for aromatic VOCs, emphasizing its potential for more effective environmental applications.

He et al.[47] demonstrated that corncob-derived biochar, particularly the CC-3-700 sample, effectively absorbs benzene (a carcinogenic aromatic VOC) owing to its high specific surface area and distinctive pore structure. This highlights the potential of corncob biochar to significantly reduce benzene concentrations. The same biochar also achieved a notable toluene absorption capacity of up to 573.5 mg/g, further validating its efficacy in VOC removal. In a separate study, Wołowiec et al.[48] investigated the enhanced removal of BTEX compounds (benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene) using biochar modified with hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (HDTMA-Br). Although specific reduction percentages were not provided, the modification markedly improved the biochar's sorption properties. The study further documented adsorption capacities of 6.82 mg/g for p-xylene, and 0.65 mg/g for dibenz[a,h]anthracene, demonstrating the modified biochar's effectiveness in removing various aromatic compounds from aqueous solutions.

Table 2 summarizes the removal mechanisms of aromatic VOCs by various types of biochar, based on findings from different studies.

Table 2. Summary of removal mechanisms of aromatic VOCs by various types of biochar

Biochar feedstock/modification Target aromatic VOS (s) Adsorption capacity (mg/g) Key mechanism/finding Ref. Wheat straw, hardwood; NaOH-benzoic acid modification Toluene p-xylene ~2× increase vs unmodified Increased surface area, oxygen functional groups (hydroxyl, carboxyl) enhance adsorption [11] biochars from various feedstocks, pyrolyzed at 300–600 °C Toluene, acetone, cyclohexane 5.58–91.2 Surface area and noncarbonized organic matter are key; lower pyrolysis temperature resulted in higher capacity [35,38] Wheat straw, corn straw, bagasse Toluene, p-xylene, hexane, acetone 51–110 (single), 50–109 (mixed) Bagasse biochar had highest capacity; surface area and pore volume critical [49] Algae Non-polar aromatics, e.g., benzene derivatives Emission reduction: 76%

(iron-rich) vs 59% (low-iron)Fe content and N–Fe bonds boost adsorption and catalytic degradation [50] Rapeseed cake, walnut shells; H2SO4 and KOH activation Toluene, acetone Up to 166.7 (H2SO4-activated) Acid activation increases surface area and pore volume, enhancing adsorption [51] Engineered biochar

(hydrophobic, porous)Benzene, toluene Benzene: 136.6, toluene: 94.6 Hydrophobicity and porosity increase selectivity for aromatics, reduce water vapor uptake [52] Straw–sludge blend, CO2/H2O activation Toluene 5.1× higher than activated biochar, 3.2× than commercial Physical activation with CO2/H2O is cost-effective and environmentally friendly [53] Non-aromatic VOCs removal

-

Biochar's applications extend beyond aromatic compound adsorption, with demonstrated efficacy in reducing non-aromatic VOCs. For instance, Mousavi et al.[50] reported that iron-rich biochar effectively adsorbed heptane and cycloheptane from asphalt emissions, highlighting the critical role of biochar composition in determining adsorption performance. The specific reduction efficiencies non-aromatic VOCs by biochar, as documented in the literature, are discussed in detail below.

A study investigating biochar's inhibitory effects on asphalt-derived VOC emissions confirmed its effectiveness against various non-aromatic compounds, including alkanes and alkenes. Zhou et al.[46] observed that biochars derived from rice husk, straw, and coffee grounds significantly reduced emissions of these compounds during paving operations. Among these, rice husk-derived biochar exhibited the highest VOC reduction efficiency, emphasizing that feedstock type and morphological characteristics are key determinants of adsorptive performance.

In the context of non-aromatic VOC reduction, hexane is particularly noteworthy due to its widespread use as a solvent and high volatility. Kaikiti et al.[54] investigated the hexane adsorption by pomegranate peel-derived biochar, reporting a 100% hexane removal within 480 min, demonstrating the biochar's substantial adsorption capacity. This process was facilitated by hydrophobic interactions and Van der Waals forces, which contributed to the efficient hexane molecule capture. The authors also examined reduction of alcohols and ketones using biochar produced via slow pyrolysis of cattle manure, highlighting its dual potential in agricultural waste management and odor control. The biochar's porous structure and large surface area provide an effective platform for VOC adsorption, playing a crucial role in capturing and retaining non-aromatic compounds.

Table 3 outlines the mechanisms by which different biochar types remove non-aromatic VOCs, based on findings from various studies.

Table 3. Summary of removal mechanisms of non-aromatic VOCs by various types of biochar

Biochar feedstock/modification Target aromatic VOS (s) Adsorption capacity (mg/g) Key mechanism/finding Ref. Rice husk, straw, coffee grounds Alkanes, alkenes (from asphalt) Rice husk biochar showed highest VOC reduction Feedstock type and morphology critical for adsorption performance [55] Pomegranate peel biochar Hexane 100% reduction within 480 minutes Hydrophobic interactions and Van der Waals forces drive efficient hexane capture [56] Iron-rich biochar Heptane, cycloheptane 76% emission reduction (iron-rich) vs. 59% (low-iron) Iron content and N–Fe bonds enhance adsorption and catalytic degradation [50] Poultry litter, swine manure,

oak, coconut shell biocharsVolatile fatty acids, reduced sulfur compounds (e.g., acetic acid, DMDS, DMTS) Oak biochar (500 °C) showed high sorption capacity; plant-biomass biochars better than manure-based Sorption capacity varies with feedstock; plant-based biochars better for sulfur compounds; potential soil amendment reuse [57] Wood shaving, chicken litter biochars (activated and

non-activated)Gaseous ammonia (NH3) Adsorption capacity: 0.15–5.09 mg N/g Phosphoric acid activation greatly increases NH3 adsorption; surface acidic oxygen groups important [58] Pine needle biochars

pyrolyzed at 100–700 °CNonpolar non-aromatic VOCs (e.g., naphthalene) Sorption capacity varies with pyrolysis temperature Sorption mechanism shifts from partitioning to adsorption with increasing pyrolysis temperature [29] Reduction of sulfur VOCs

-

Given the harmful effects and pungent odor of sulfur-containing VOCs, the application of biochar for mitigating their emissions has emerged as a prominent research focus. Meiirkhanuly[59] specifically evaluated biochar's potential in reducing emissions of sulfur compounds, such as hydrogen sulfide, from swine manure.

Similarly, Li et al.[60] investigated the adsorptive desulfurization capacity of lignin-derived biochar toward dibenzothiophene (DBT), a sulfur-containing aromatic VOC. Modified using potassium hydrogen phthalate, this biochar significantly reduced DBT levels, though the study did not specify exact reduction percentages. Yang et al.[61] explored the use of bamboo-derived porous biochar for DBT adsorption from model fuel oils, achieving a DBT reduction efficiency of up to 92% with 0.5 g of biochar. This high efficiency is attributed to the biochar's high micropore ratio and surface oxygen-containing acid functional groups, which enhanced the adsorption process. The study further emphasized biochar's potential for removing sulfur compounds from fuel oils, thereby contributing to the production of cleaner fuel.

Chen et al.[62] focused on developing nitrogen-doped magnetic biochar for the removal of sulfamethoxazole (a sulfur-containing compound). While specific reduction data were not provided, the biochar exhibited high sorption efficiency, suggesting strong potential for mitigating sulfur-containing VOCs.

Mhemed et al.[63] examined the use of biochar derived from spent coffee grounds for thiophene reduction from waste tire pyrolysis oils, reporting a 49% decrease at saturation. Additionally, this biochar also influenced the reduction of toluene and facilitated the conversion of limonene, demonstrating its broad VOC adsorption capability. Key properties underpinning the biochar's effectiveness included its mesoporous volume, acidic pH, mineral content (P, K, Ca), nitrogen presence, and functional groups. These characteristics promoted VOC decomposition through dehydrogenation and coke formation, thereby enhancing the removal of both sulfur compounds and aromatic hydrocarbons from pyrolysis oils.

Dehydrogenation refers to a reaction that removes hydrogen atoms from organic molecules, typically increasing their reactivity or susceptibility to further transformation[64]. Coke formation involves the generation of a solid carbonaceous residue (referred to as 'coke') from organic molecules via intense thermal or catalytic cracking processes[65]. In this context, coke formation occurs when VOC molecules, particularly aromatic hydrocarbons, undergo polymerization and condensation reactions during pyrolysis or catalytic treatment, leading to the formation of solid carbon deposits[66]. This solid coke can trap or immobilize sulfur compounds and aromatic hydrocarbons, effectively removing them from the liquid or gas phase being treated. Additionally, coke formation can enhance overall removal efficiency by preventing these harmful compounds from remaining in pyrolysis oils or emissions, acting as a form of physical and chemical capture. By converting volatile pollutants into less mobile solid carbon materials, coke formation aids in reducing sulfur-containing compounds and aromatic hydrocarbons in treated streams, ultimately improving pyrolysis oil quality and minimizing the environmental impact of emissions.

Waste valorization

-

Utilizing waste biomass for biochar production is aligned with the principles of the circular economy, enabling cities to reduce both waste disposal costs and the environmental impacts linked to landfilling or incineration[67].

The asphalt paving industry faces growing pressure to enhance sustainability and reduce environmental impacts. Biochar—a carbonaceous material produced through thermochemical conversion of biomass under oxygen-limited conditions—has emerged as a promising modifier for asphalt binders and mixtures. As a renewable resource derived from waste biomass, biochar provides multiple advantages, including improved asphalt performance, reduced emissions, and carbon sequestration[37].

Numerous studies have demonstrated that biochar modification can enhance the high-temperature performance and aging resistance of asphalt binders. Specifically, biochar typically increases the complex shear modulus (G*) and decreases the phase angle (δ) at high temperatures, which indicates enhanced rutting resistance[68]. However, the reported effects of biochar on low-temperature performance are mixed. While some studies have noted reduced low-temperature cracking resistance with biochar addition[69], others have observed minimal impact[70]. The high specific surface area and porous structure of biochar are believed to contribute to its stiffening effect, whereas improvements in aging resistance are often attributed to its antioxidant properties[71]. Furthermore, researchers have explored the use of biochar to enhance the self-healing capability of asphalt. The porous structure of biochar has been reported to act as a reservoir for rejuvenating agents, promoting crack healing over time[72]. Within the asphalt matrix, biochar functions as a reservoir, gradually releasing components that aid in restoring the maltene fractions lost during aging, thereby promoting self-healing and crack closure over time[10,72]. This property could potentially extend the service life of asphalt pavements and reduce maintenance costs. However, the effects of biochar appear to depend on its type and dosage; thus, optimizing biochar properties and identifying optimal dosage levels remain important ongoing research areas. It is noteworthy that the success of self-healing is dependent on substrate materials (i.e., the asphalt and its aging degree) as well as the size of cracks and crevices.

While laboratory studies on biochar-modified asphalt are abundant, field implementations remain limited. A few small-scale field trials have been conducted, which generally show performance comparable to that of conventional asphalt in the short term[12,73]. However, long-term field performance data remains scarce. Comprehensive field studies evaluating durability, environmental impacts, and life-cycle costs are required to validate the benefits of biochar modification at full scale. One challenge in field implementation is ensuring consistent biochar quality and properties across different production batches. Developing standardized testing and characterization methods for biochar intended for asphalt applications will be crucial for its widespread adoption. Additional key challenges include achieving uniform dispersion of biochar in asphalt, as well as maintaining consistent biochar quality and properties across different production batches.

Carbon sequestration

-

Biochar has emerged as a promising material for enhancing carbon sequestration in construction applications, particularly in cementitious composites. Its porous structure and high carbon content enable it to act as a stable reservoir for long-term carbon storage when incorporated into building materials. Studies[10,12] have highlighted the dual benefits of biochar in building and road materials: in addition to improving material durability, it significantly enhances carbon capture through both physical entrapment and chemical reactions within the matrix. The sustainable utilization of biochar as a cement substitute has been shown to enhance the mechanical properties of concrete composites, while simultaneously contributing to carbon sequestration through increased carbon storage capacity and reduced cement consumption[13].

Rani et al.[74] further elaborated that biochar incorporation in cement and concrete improves microstructural properties, which in turn, facilitate enhanced carbonation. This process promotes the fixation of CO2 within the hardened cement matrix. Their findings confirm that biochar acts synergistically, as it provides reactive surfaces for carbonation alongside traditional cementitious phases. Experimental and simulation studies by Zou et al.[75] have qualified the carbon sequestration potential of encapsulated biochar and accelerated carbonation in aggregates and concrete, demonstrating a marked increase in carbon fixation efficiency via combined physical and chemical processes. Complementing these findings, Chen et al.[76] have shown that the use of biochar with dual-particle-size gradation optimizes mechanical performance while maximizing carbon sequestration in accelerated carbonation-cured cement-based materials, suggesting the need for a tailored approach to biochar design in sustainable construction.

Yang et al.[77] have explored the internal and external synergistic effects of modified biochar on CO2 capture in cement-based materials, emphasizing biochar's role in enhancing both immediate and long-term carbonation reactions, thereby significantly improving overall carbon capture rates. Several researchers have demonstrated that the use of biochar accelerates carbon mineralization, refines microstructure, and enhances mechanical properties, thus providing an integrated strategy for green construction[78,79]. Moreover, Kua & Tan[79] have proposed a novel accelerated carbonation method that utilizes both dry and pre-soaked biochar to precisely regulate carbon sequestration capacity and mortar performance. This work underscores biochar's versatile role in optimizing carbon capture technologies for cementitious systems.

Collectively, these studies illustrate the multifaceted benefits of biochar for carbon sequestration, reinforcing its potential to transform sustainable construction practices by simultaneously improving material performance and mitigating atmospheric CO2 levels.

Soil regeneration

-

Biochar improves soil structure by increasing porosity and reducing bulk density, which enhances root penetration and aeration in compacted urban soils. Its high surface area and porous nature improve water retention and nutrient-holding capacity, particularlly in sandy or degraded soils. These properties are especially valuable in urban green spaces, where soil quality is typically poor, and irrigation resources are limited. Furthermore, biochar acts as a long-term soil amendment by enhancing cation exchange capacity (CEC), thereby improving nutrient availability and reducing leaching losses. Collectively, these attributes promote healthier plant growth, stimulate microbial activity, and elevate soil organic matter—all key indicators of soil regeneration[14].

Coconut-derived residues, including husks, leaf petioles, and coir pith, were successfully converted into biochar via low-tech pyrolysis methods suitable for smallholder use. These biochars exhibited alkaline pH (> 7.5), favorable for acidic tropical soils, and high potassium content (> 2.5%), making them beneficial for plant nutrition and resilience. Application of this biochar, either alone or in combination with coconut leaf vermicompost, enhanced soil NPK (nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium) levels, stimulated microbial activity, and improved enzymatic functions. Additionally, improvement in seed germination, increased mycorrhizal colonization, and enhanced root nodulation in cowpea were observed. Field trials showed a 50% increase in chili yield when tender husk biochar was applied with vermicompost, confirming its potential to support regenerative agriculture by improving soil fertility and crop productivity[80].

Recently, de Lima et al.[15] assessed the impact of two biochars, derived from grape stalks (B1) and grape fermentation residues (B2), when applied individually and in combination with Trichoderma aureoviride URM 5158 (F1) and T. hamatum URM 6656 (F2), on soil chemical and microbial properties in maize-cultivated soils under natural regeneration. Biochar treatments significantly improved soil phosphorus, potassium, total organic carbon (TOC), and microbial biomass carbon (MBC) content, as well as activities of alkaline phosphatase and β-glucosidase. These findings demonstrate the potential of integrating biochar with beneficial fungi to restore soil health and functionality in degraded environments.

Water and wastewater management

-

The application of biochar in water treatment has demonstrated its multifaceted potential and effectiveness[81]. Biochar exhibits exceptional adsorption properties, enabling it to efficiently remove contaminants from water sources. Owing to its porous structure and high surface area, biochar can effectively trap various pollutants, including heavy metals, organic compounds, and pathogens, thereby improving water quality[82]. For heavy metal removal, electrostatic attraction and ion exchange are facilitated by surface charges in biochar; complexation reactions occur between heavy metals and biochar's functional groups, such as hydroxyl, carboxyl, and phenolic groups; and co-precipitation of insoluble metal compounds may also occur, a process influenced by factors such as solution pH[83]. For organic contaminant removal, adsorption is driven by hydrophobic interactions and chemical bonding, often enhanced through biochar modification methods that increase surface area and functional groups[84].

Additionally, biochar's chemical composition and surface functionalities allow it to catalyze redox reactions, which in turn facilitate the degradation of recalcitrant pollutants[85]. Its renewable nature and low-cost production further emphasize its potential as a sustainable solution for water treatment.

Biochar also serves as a valuable tool for wastewater treatment, facilitating the removal of contaminants including organic matter, nutrients, pathogens, and emerging pollutants[86]. Integrating biochar into filtration systems or treatment processes can enhance the quality of treated wastewater prior to discharge or reuse. Moreover, biochar's ability to promote microbial activity supports the breakdown of pollutants, making it a versatile solution for treatment systems spanning individual households to small communities. Its sustainability and cost-effectiveness position it as a highly promising option[87]. Table 4 summarizes the diverse applications of biochar in water and wastewater management. In subsequent sections, the specific applications of biochar in water and wastewater treatment are discussed.

Table 4. A summary of the diverse applications of biochar in water and wastewater management

Application Biochar functionality Key findings/advantages Ref. Heavy metal removal Adsorption of heavy metals (Pb2+, Cd2+, Cu2+, Zn2+, Ni2+) through biochar's porous structure and functional

groups- High affinity for Pb2+ over Cd2+

- Maintains > 70% removal efficiency after multiple cycles

- More cost-effective than activated carbon[88,89] Dye removal Adsorption of complex dye molecules utilizing mesoporous and nanostructured biochar with high surface area. - Removal efficiencies up to 95% (e.g., Rhodamine B)

- Effective against various dye types ( direct, acid, reactive)

- Reusability over multiple cycles[90,91] Nutrient (N & P) removal Adsorption of nitrogen (ammonium, nitrate) and phosphorus (phosphate) via ion exchange and surface complexation, often enhanced by metal loading. - Iron-loaded biochar removes > 85% TP and 60% TN with minimal desorption

- Effective removal of organic and inorganic phosphorus from industrial wastewater[92] Organic contaminants removal Adsorption and catalysis of recalcitrant organic

pollutants (pesticides, antibiotics, herbicides) through surface functional groups and porous matrices.- Up to 70% removal rate of sulfonamide antibiotics

- Maximum adsorption capacity ~ 80 mg/g for glyphosate

- Facilitates degradation via catalyzed redox reactions[85,93,94] Emerging contaminants (PFAS) Functionalized biochar with enhanced surface

chemistry for adsorption of PFAS through electrostatic, hydrophobic interactions and ion exchange.- Functionalized biochars improve PFAS removal efficiency

- Long-chain PFAS adsorbed more effectively than short-chain

- Optimal biochar dosage required[95] Pathogen removal Adsorption and entrapment of pathogens within biochar's porous structure and antimicrobial surface functionalities. - Effective removal of bacterial and viral pathogens

- Enhances microbial activity beneficial for pollutant biodegradation[87] Additive in anaerobic digestion Enhancement of anaerobic digestion process by improving microbial activity, accelerating methane production, and speeding up degradation reactions. - Reduction of lag time by up to 30%

- Increase methane yield by 27%–42%

- Enhances COD removal by 50%[96−98] Adsorbent for the removal of contaminants from water and wastewater

Heavy metal removal

-

In recent years, the use of biochar for removing heavy metals from polluted water and wastewater streams has attracted significant attention. This is attributed to the toxicity of heavy metals, which can exert an adverse impact on the ecosystem and human health[16]. Traditional treatment approaches have shown limited efficacy in addressing such toxic water and wastewater, prompting the adoption of biochar as a more efficient and cost-effective alternative to activated carbon[99]. Researchers have explored the efficiency of various types of biochar in removing heavy metals from polluted flows. Ni et al.[100] demonstrated in their study that biochar produced from anaerobically digested sludge through pyrolysis can effectively remove heavy metals such as Pb2+ and Cd2+. Their findings revealed that the biochar exhibited a higher affinity for Pb2+ than for Cd+2 in single and dual metal systems. Similarly, Truong et al.[101] investigated biochar derived from the pyrolysis of the algae Sargassum hemiphyllum for heavy metal adsorption. The research indicated that the optimal pyrolysis temperature for this biochar production was 700 °C, and the resulting biochar exhibited exceptional adsorption capacity for heavy metals such as Cu2+, Zn2+, Ni2+, and Cd2+. Additionally, it retained 70% of its Cu+2 removal efficiency even after 10 cycles.

Dyes removal

-

Dye molecules exhibit complex structures, which renders their removal from water and wastewater particularly challenging[102]. However, studies have demonstrated that biochar can effectively absorb a wide range of dye molecules[90]. Chen et al.[103] synthesized biochar via co-pyrolysis of sewage sludge and rice husk in a 1:1 ratio at 500 °C for 2 h, and tested its efficacy in removing dyes including Reactive Blue 19, Acid Orange II, Direct Red 4BS (DR), and Methylene Blue (MB). The results indicated that the biochar effectively adsorbed all tested dyes, with the highest efficiency observed for direct dyes, followed by acid and reactive dyes. In another study, Behera et al.[91] investigated the potential of biochar derived from Calophyllum inophyllum seeds as a bio-adsorbent for the removal of Rhodamine B dye. The mesoporous and nanostructured properties of the biochar were responsible for its high adsorption performance. At a biochar dosage of 1.2 g/L, the removal efficiency reached 95%, and its maximum equilibrium adsorption capacity was determined to be 169.5 mg/g. Moreover, the study confirmed that the mesoporous biochar could be effectively reused for up to three cycles.

Nitrogen and phosphorus removal

-

Biochar exhibits the capacity to adsorb nutrients (e.g., nitrogen and phosphorus) commonly present in water and wastewater[104]. These nutrients are typically present as ammonium, nitrate, and phosphate, which can induce eutrophication[105]. Numerous studies have investigated the adsorption of nitrogen and phosphorus by different biochar types, yielding significant findings. Min et al.[106] prepared iron-loaded biochar from corn stalks via impregnation with FeCl3, followed by pyrolysis at 550 °C for 30 min. The biochar was used to remove total nitrogen (TN) and total phosphorus (TP) from wastewater. The results indicated that the biochar achieved a TP removal efficiency of over 85%; moreover, less than 0.5% of adsorbed TP was desorbed during desorption experiments. Additionally, the biochar removed 60% of TN, with only 1% of adsorbed TN desorbed. The maximum adsorption capacity of the biochar was over 14 mg/g for TN and 90 mg/g for TP. Pan et al.[107] investigated the use of biochar for phosphorus removal from industrial discharged circulating cooling water. This type of water is commonly used in industrial settings to cool equipment and ensure smooth system operation of the system, but it often contains high concentrations of organic and inorganic phosphorus. To produce biochar, Pan et al.[107] subjected wheat straw to pyrolysis at 600 °C for 60 min. The study found that the biochar achieved TP and PO4−3 removal efficiencies of 90.54% and 87.62%, respectively.

Organic contaminant removal

-

Organic contaminants represent a significant category of pollutants in aquatic environments, encompassing pesticides, herbicides, antibiotics, and various other substances. These pollutants often exhibit toxicity and can reduce dissolved oxygen levels in water, posing risks to both aquatic ecosystems and human health[86]. Multiple studies have shown that biochar can effectively adsorb organic matters in water and wastewater treatment processes. Sun et al.[108] investigated the effectiveness of biochar produced from shredded cotton stalks through pyrolysis for removing sulfonamide antibiotics—compounds frequently detected in the environment. Pyrolysis was performed under oxygen-free conditions at 350 °C. With a biochar dosage of 1 g/L, the adsorption process reached equilibrium in approximately 24 h, achieving a removal rate of up to 70%. Similarly, Jiang et al.[94] explored the use of biochar to adsorb glyphosate, a widely used agricultural herbicide notorious for posing health risks and adversely affecting crops. The biochar in their study was prepared by pyrolyzing palm waste at 500 °C for 8 h. It exhibited maximum adsorption capacity of 80 mg/g at pH 4, indicating its potential for treating glyphosate-contaminated agricultural wastewater.

Additive for anaerobic digestion

-

Biochar has been demonstrated as a valuable additive in anaerobic digestion processes. Research has shown that it can enhance the reaction rate, increase methane yield, improve chemical oxygen demand (COD) removal, and reduce lag time[96]. These benefits are largely attributed to biochar's ability to create a favorable environment for microbial activity, owing to its porous structure, functional groups, and abundant micro- and macro-nutrients[109]. Wang et al.[18] introduced a novel approach to accelerate methanogenesis recovery in severely acidified anaerobic digestion systems using sawdust-derived biochar produced at 500 °C. The addition of 20 g/L of this biochar reduced lag time and increased the maximum methane production rate by 30%. Similarly, Tiwari et al.[97] investigated the co-digestion of wheat husk and sewage sludge, finding that hardwood biochar at a dosage of 20 g/L enhanced COD removal by 50% and methane production by 27%. In another study, Sun et al.[98] demonstrated that incorporating 10 g/L of corn straw-derived biochar (produced at 600 °C) into the anaerobic co-digestion of glucose and food waste, increased cumulative methane production by 42%.

Biochar can also enhance selective methane removal from the atmosphere or exhaust gases, particularly in applications such as landfill soil covers and biocovers[110]. Studies have shown that biochar amendment improves methane oxidation efficiency by providing a habitat for methane-oxidizing bacteria (MOB), which metabolize methane into less harmful carbon dioxide. For example, biochar-amended landfill soil covers exhibited methane removal efficiencies up to around 90%, significantly higher than non-amended controls, especially when combined with active aeration to maintain oxygen availability and stimulate microbial activity[111,112]. This enhanced methane capture capability is attributed to biochar's porous structure, high surface area, and alkaline properties, which create favorable conditions for MOB proliferation and activity.

Global use of biochar for water and wastewater treatment

-

Biochar-based water treatment technologies have been explored and deployed in New York City (USA)[95]. Regional studies have demonstrated the efficacy of biochar in removing contaminants such as pharmaceuticals, organic pollutants, and heavy metals from water sources. For instance, Mer et al.[113] conducted a study at the State University of New York (USA) to investigate the potential of biochar produced via co-pyrolyzing of sawdust with iron-rich biosolids and polyaluminum sludge. The study assessed the performance of the resulting biochar in removing perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) from both drinking water and sludge digestate filtrate. Results showed that biosolids-sawdust biochar and aluminum sludge-sawdust biochar achieved PFOS removal efficiencies of 71.4% and 66.9% from drinking water, and 77.9% and 87.9% from sludge digestate filtrate, respectively. The maximum PFOS adsorption capacities were 27.2 mg/g for biosolids-activated biochar and 19.2 mg/g for aluminum sludge-activated biochar, compared to only 6.2 mg/g for sawdust biochar alone. Field trials in New York (USA) have confirmed that biochar application can significantly improve water and wastewater treatment efficiency. This is attributed to biochar's porous structure and high surface area, which provide abundant adsorption sites for pollutants. Moreover, its stability ensures long-term efficacy in water treatment applications. Additionally, using locally sourced feedstocks for biochar production aligns with New York's sustainability goals, as this approach facilitates effective waste management and reduces the environmental impact associated with conventional water treatment methods. Research in Singapore has shown biochar's efficacy in removing emerging contaminants from water and wastewater effluent. For instance, researchers in Singapore reported that biochar has been effectively utilized as a low-cost adsorbent for Rhodamine B dye removal, exhibiting a maximum adsorption capacity of 189.83 mg/g, and a surface area of 776.46 m2/g[114].

In China, biochar-based water treatment technologies are being explored as part of Beijing's broader initiatives to improve water quality. Studies in Beijing have verified biochar's effectiveness in removing heavy metals, organic pollutants, and nutrients from contaminated water and wastewater. Recently, the Centre for Urban Environmental Remediation at Peking University, conducted a field study evaluating the use of novel biochar/Fe-modified biocarriers in tidal-flow constructed wetlands for enhanced nitrogen removal from eutrophic water under low-temperature conditions. The study reported an average nitrogen removal efficiency of 80% at temperatures ranging from 8 to 16.7 °C—a result that underscores the practical applicability of such systems for treating eutrophic water in colder climates[115]. Zhu et al.[116] investigated the removal of EDTA-Cu (II) complexes using a combination of the Fenton reaction and adsorption via nano manganese oxide-modified biochar. This approach achieved copper and total organic carbon removal efficiencies of 94.67% and 92.79%, respectively. The modified biochar was noted for its high stability, cost-effectiveness, broad availability, and strong performance in removing Cu complexes, indicating its potential for future application in treating other metal-ligand complexes.

In Alexandria, Egypt, biochar has been employed to adsorb contaminants, reduce pollutant levels, and improve the efficiency of treatment processes. The Egypt-Japan University of Science and Technology (E-JUST) conducted a study to investigate the application of eggshell-modified biochar as an adsorbent for the treatment of petroleum-contaminated wastewater. In mono-component systems, at pH 10 with an adsorbent dosage of 2 g/L and a contact time of 60 min, the biochar achieved xylene and toluene removal efficiencies of 86.6% and 79.1%, respectively. Furthermore, the modified biochar successfully treated real wastewater over five adsorption-regeneration cycles, demonstrating its potential for scalable applications[117]. Additionally, a study by Moharm et al.[118] focused on developing and characterizing a biochar-based biosorbent derived from agricultural waste, specifically sugarcane bagasse, for the removal of cationic dyes from wastewater. Under optimized conditions, the removal rates for methylene blue and crystal violet exceeded 98%, with maximum adsorption capacities of 114.42 and 99.50 mg/g, respectively. These findings highlight the viability of using locally sourced biomass to produce cost-effective, high-efficiency biochar for wastewater treatment in Alexandria (Egypt).

In Tokyo (Japan), biochar-based water treatment technologies have emerged as a viable solution for addressing water quality issues in Tokyo's reservoirs and rivers. Regional studies have shown that biochar exhibits effectiveness in removing a variety of contaminants, including organic compounds, heavy metals, and pathogens, from polluted water sources.

One such study, conducted by Kohira and colleagues[17] at Soka University in Tokyo, examined biochar produced from water hyacinth and chemically treated with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and potassium hydroxide (KOH) for the removal of ammonium-nitrogen (NH4+−N) from wastewater. The findings demonstrated that modified biochar exhibits potential as an alternative adsorbent for NH4+−N removal. Specifically, the adsorption capacity of untreated biochar (2.14 mg/g) increased approximately eightfold (17.1 mg/g) after KOH modification and tenfold (21.5 mg/g) following H2O2 treatment.

In another study[119], researchers investigated the effectiveness of treating water hyacinth juice in a sequential batch reactor using biochar derived from local waste biomass (coffee husk). The biochar achieved an 88.6% total organic carbon removal efficiency and facilitated the production of abundant biogas (CH4), with a yield of 472 mL/g-VS. This approach not only demonstrates an efficient method for organic waste treatment using locally sourced biomass but also highlights the dual benefits of pollutant reduction and energy recovery. Field trials conducted in Tokyo's aquatic systems have confirmed the significant potential of biochar in reducing pollutant levels and enhancing water clarity.

-

As the global imperative for urban sustainability intensifies, biochar emerges as a versatile, transformative material capable of addressing multifaceted environmental challenges in cities. This perspective has revealed biochar's diverse applications across air quality improvement, waste valorization, carbon sequestration, soil regeneration, and water and wastewater treatment, positioning it as a cornerstone for sustainable urban development within circular economy frameworks. Its capacity to convert organic waste into a high-value, carbon-rich product not only mitigates waste disposal issues but also enhances urban ecosystems through pollutant capture, soil enhancement, and carbon storage. Biochar's porous structure, large surface area, and chemically active functional groups enable effective adsorption of VOCs, heavy metals, and emerging contaminants. Additionally, its integration into construction materials such as asphalt and concrete improves durability while facilitating carbon sequestration on centennial timescales. Field trials across cities, including New York, Singapore, Beijing, Alexandria, and Tokyo, demonstrate biochar's global applicability, with promising outcomes in reducing VOC emissions, improving soil fertility, and treating water. These results underscore its potential to foster climate-resilient urban environments.

Despite these advancements, notable research gaps persist in fully harnessing biochar's potential within the built environment. Standardization of biochar production to ensure consistent quality across feedstocks and applications is critical, as variations in physicochemical properties can affect performance. Optimizing modification techniques for specific urban challenges such as VOC adsorption or heavy metal removal demands further investigation to enhance efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Long-term field studies are needed to validate laboratory findings, particularly for biochar-modified asphalt and concrete, where durability, life-cycle costs, and environmental impacts remain underexplored. Additionally, integrating biochar with microbial inoculants for soil regeneration holds promise but requires deeper investigation to optimize microbial interactions and scalability in urban green spaces. Emerging contaminants such as microplastics represent a critical area for future research. While biochar's adsorption capabilities for pollutants such as PFAS are well-documented, its potential to capture microplastics—a current global concern highlighted in UN discussions—remains largely unexplored. Preliminary studies suggest biochar's porous structure and surface chemistry may trap microplastics in water or soil, but systematic research is required to assess its efficacy, optimal feedstock, and modification strategies for this application. Similarly, biochar's role in mitigating other pressing urban issues—such as urban heat island effects through reflective or thermal-regulating pavement additives, or its use in green roof systems to enhance water retention and reduce runoff—warrants further investigation.

Addressing these research gaps will require interdisciplinary collaboration, encompassing materials science, environmental engineering, and urban planning. Developing comprehensive regulatory frameworks and standards to support large-scale biochar deployment is imperative to ensure safety, efficacy, and environmental benefits. Public-private partnerships and pilot programs serve to bridge the gap between research and implementation, fostering innovation in biochar applications. By addressing these challenges, biochar can evolve from a promising material to a foundational component of sustainable urban systems, in alignment with global goals for climate resilience and circularity. Its capacity to address interconnected urban challenges—ranging from waste management to pollution control and climate change mitigation—positions biochar as a pivotal tool for creating greener, more livable cities of the future.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: formal analysis: Alayaki FM; data curation: Alayaki FM, Hajikarimi P; writing – original draft: Alayaki FM, Hajikarimi P, Meky N, Rashid S; writing – review and editing, supervision: Fini EH. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Biochar improves air and water quality, soil health, carbon storage, and waste management in cities.

It can absorb up to 76% of harmful VOCs from asphalt, reducing urban air pollution.

In concrete, biochar boosts strength and locks in CO2− in water treatment, it removes pollutants and increases methane yields.

It enhances soil fertility and crop productivity through better water retention and nutrient availability.

Widespread adoption faces challenges like cost, technical limits, and lack of supportive policies.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Alayaki FM, Hajikarimi P, Meky N, Rashid S, Fini EH. 2025. Global applications of biochar in sustainable cities of the future: a perspective. Biochar X 1: e010 doi: 10.48130/bchax-0025-0009

Global applications of biochar in sustainable cities of the future: a perspective

- Received: 24 July 2025

- Revised: 31 August 2025

- Accepted: 13 October 2025

- Published online: 20 November 2025

Abstract: As urbanization intensifies, cities are facing escalating challenges related to environmental degradation and resource management, necessitating innovative and sustainable solutions. Biochar, a carbon-rich material derived from the pyrolysis of organic waste, has emerged as a versatile tool for advancing urban sustainability. This perspective synthesizes key findings regarding the global applications of biochar in promoting sustainable urban development, demonstrating its efficacy across multiple domains, including air quality improvement, waste valorization, carbon sequestration, soil regeneration, and water purification. By converting organic waste into a stable form of carbon, biochar provides a practical strategy to reduce landfill use and mitigate greenhouse gas emissions. Notably, biochar also contributes to reducing airborne pollutants. Recent studies have shown that certain metal-rich biochars can adsorb volatile organic compounds emitted from asphalt surfaces (up to 76%). Asphalt represents a less recognized yet significant source of urban air pollution, and this finding highlights an additional pathway through which biochar can improve air quality and extend infrastructure longevity. In the construction sector, the incorporation of biochar into cement and concrete not only enhances mechanical properties but also enables long-term carbon sequestration via carbonation processes. For soil regeneration, biochar improves porosity, water retention, and nutrient availability, increasing crop yields (e.g., 50% for chili in field trials). In water and wastewater treatment, biochar removes heavy metals (> 70% Pb2+), dyes (up to 95%), nutrients, and emerging contaminants such as PFAS. Additionally, it boosts methane yields in anaerobic digestion by 27%–42%. Furthermore, the potential of biochar in renewable energy systems and decentralized water treatment solutions underscores its value in building more resilient urban infrastructure. When integrated into circular economy models, biochar can facilitate the closure of resource loops, reduce environmental footprints, and support regenerative city planning. Despite its promising prospect, the large-scale adoption of biochar is hindered by several challenges, including technical limitations, economic constraints, and the lack of supportive policies and standards. By synthesizing current research findings and emerging applications, this perspective positions biochar as a versatile and foundational component in the transition toward climate-resilient, sustainable cities.

-

Key words:

- Biochar /

- Sustainability /

- Circular economy /

- Biomass /

- Environment /

- Carbon footprint /

- Volatile organic compounds /

- Water purification /

- Water retention