-

The worldwide transition toward renewable power is intensifying the search for low-cost, earth-abundant electrocatalysts that can accelerate the oxygen-evolution reaction (OER)—the sluggish half-reaction that currently limits the efficiency of alkaline water-splitting and many metal–air batteries[1,2]. 4 e–/4 H+ transfer, adsorption of *OH/*O/*OOH intermediates and the concomitant lattice reconstruction all impose high kinetic barriers, so state-of-the-art noble-metal oxides (IrO2, RuO2) still outperform most base-metal alternatives[3]. Yet noble metals are scarce, geopolitically constrained and prone to dissolution at industrial current densities[4]. Consequently, mixed transition-metal (Ni, Co, Fe) oxides and (oxy)hydroxides have emerged as the most promising noble-metal-free OER catalysts because Ni2+/Ni3+ redox couples furnish active γ-NiOOH species while Fe incorporation dramatically raises intrinsic activity by tuning the *OOH binding energy[5,6]. Nevertheless, these oxides suffer from low electronic conductivity, nanoparticle agglomeration, and mechanical pulverization under long-term oxygen bubbling, underscoring the need for an architected, conductive, and chemically robust scaffold[7−9].

To simultaneously resolve the trade-offs among conductivity, surface area, mechanical robustness, and cost, integrating transition-metal active phases with a conductive, yet robust support has become the mainstream strategy. Carbon scaffolds are considered ideal because of their high surface area, tailorable porosity, chemical inertness, and excellent electrical conductivity[10,11]. Nonetheless, traditional carbon carriers each have their own shortcomings: polyacrylonitrile-based carbon fibers offer high tensile strength but are limited by low specific surface areas and energy-intensive pre-oxidation/carbonization routines; CVD-grown carbon fibers provide precise structural control and high purity, yet their high energy demand, expensive equipment and low yield hinder scale-up; multi-walled carbon nanotubes possess outstanding conductivity and surface area, yet they readily agglomerate in electrolytes and bind catalysts only through weak physical adsorption, compromising long-term stability. Therefore, developing next-generation carbon supports that combine green processing, tunable architecture and strong interfacial coupling with metal phases remains essential[12,13].

Lignin, the most abundant renewable aromatic polymer on Earth, is primarily obtained as a low-value by-product from the paper and biorefinery industries, with an annual production of over 70 million tons[14−16]. Its intrinsic aromatic-rich structure and abundant functional groups make it a promising carbon precursor for the fabrication of high-performance porous carbon materials[17−19]. LCFs also confer several catalytic advantages that go beyond merely replacing fossil-based precursors. First, their disordered-graphitic microtexture and naturally high O/N/S heteroatom content create abundant defects, edge planes, and electron-rich sites that can anchor ultrafine metal/metal-oxide nanoparticles through covalent bonding or strong interfacial charge transfer, suppressing sintering at elevated potentials[20]. Second, the interconnected fiber network offers straight electronic highways and open macroporous channels, minimizing resistive drop while facilitating bubble detachment and electrolyte infiltration—two factors often overlooked in planar catalyst coatings[21]. Third, the life-cycle carbon footprint of LCFs production is estimated to be < 0.5 kg CO2 eq kg–1, an order of magnitude lower than that of PAN-based carbon fibers, directly aligning electrocatalyst fabrication with circular-bioeconomy principles[22,23]. Prior studies on Pt[24], Fe-N-C[25], and Co-Fe[26,27] nano-assemblies corroborate that lignin-derived carbon hosts can even improve turnover frequencies relative to commercial Vulcan carbon, attesting to the intrinsic catalytic synergy.

Compared with conventional synthetic carbon sources, such as polyacrylonitrile (PAN) or pitch, lignin offers significant advantages, including low cost, renewability, environmental friendliness, and structural versatility[28,29]. By utilizing lignin as a precursor, lignin-derived carbon fibers (LCFs) can be prepared via electrospinning or melt-spinning followed by carbonization. These carbon fibers exhibit a continuous one-dimensional morphology, high electrical conductivity, and hierarchical porous structures, which not only facilitate rapid electron transport but also provide abundant anchoring sites for the uniform dispersion of active nanoparticles[24,30]. Moreover, the fiber morphology enhances mechanical integrity and promotes better catalyst-electrolyte interaction, which is highly beneficial for improving catalytic durability and utilization efficiency[31].

Recent advances have demonstrated that combining transition metal oxides such as NiO and Fe3O4 with carbon supports can significantly enhance OER performance due to synergistic effects between metal sites and conductive matrices[32−35]. NiO possesses a high theoretical OER activity due to its ability to switch between Ni2+ and Ni3+ oxidation states during catalysis, which plays a crucial role in driving the OER intermediate formation and transformation steps[36,37]. Fe3O4, a mixed-valence iron oxide with excellent electronic conductivity and magnetic properties, has also been found to promote charge transport and modulate the electronic structure of Ni-based catalysts[38,39]. The incorporation of Ni into Fe-based systems can tune the local coordination environment, optimize the adsorption energy of reaction intermediates (such as *OH, *O, and *OOH), and thereby improve the intrinsic catalytic activity[40]. Despite the growing interest in using biomass-derived carbon materials for electrocatalysis, reports focusing on NiO/Fe3O4-decorated lignin-derived carbon fibers for OER applications remain scarce. Given the environmental and economic merits of lignin, along with the catalytic potential of Ni-Fe oxides, the rational construction of such a hybrid catalyst system is of considerable significance. It not only provides a sustainable route for the valorization of lignin waste but also introduces a new dimension to the design of low-cost, high-performance OER electrocatalysts.

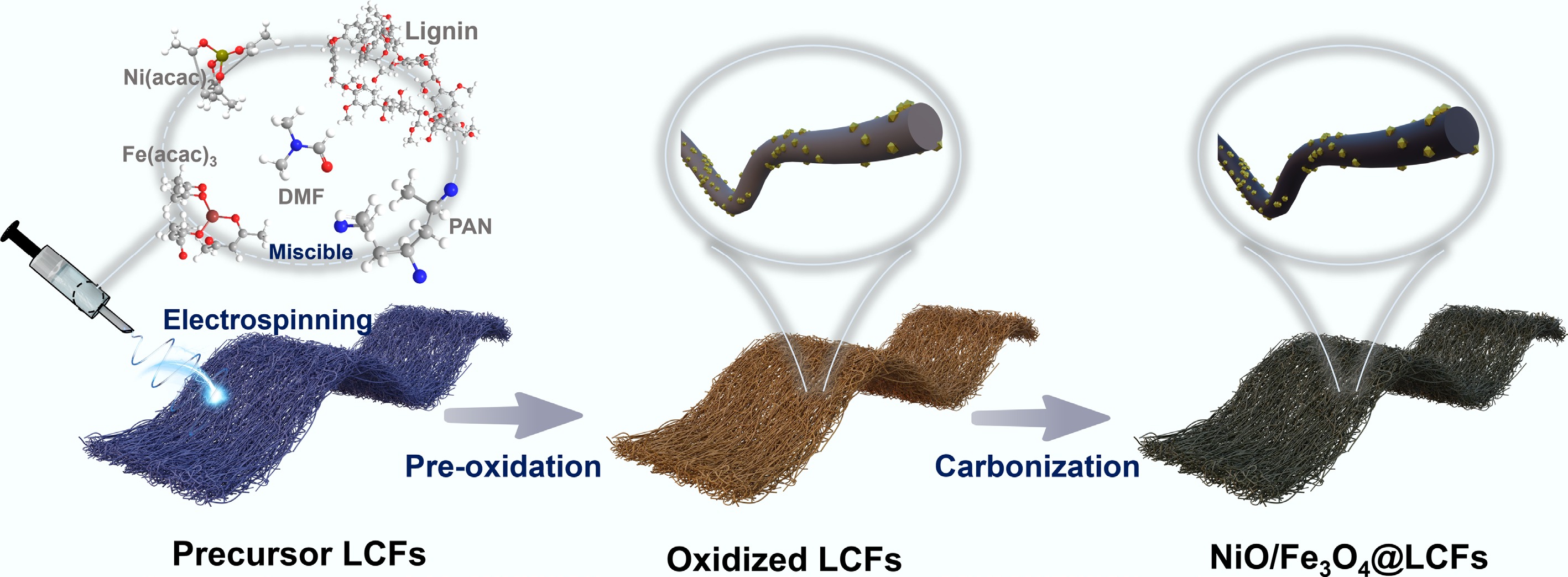

In this study, a rational and scalable approach was designed to construct a lignin-derived carbon fiber-supported bimetallic oxide catalyst for enhanced OER performance. Lignin, polyacrylonitrile (PAN), and metal precursors (Ni2+, Fe3+) were co-dissolved in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), and processed via electrospinning to form uniform precursor fibers. This ensures homogeneous incorporation of metal ions into the lignin/PAN matrix. Through subsequent pre-oxidation and carbonization, NiO and spinel-structured Fe3O4 nanoparticles are in situ generated and uniformly embedded within the conductive carbon fiber network. The resulting NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs composite provides abundant active sites, improved electrical conductivity, and a robust three-dimensional architecture that facilitates rapid electron/ion transport during OER. To elucidate the structure–function relationship, detailed characterizations were conducted using SEM, TEM, XRD, XPS, and BET surface area analysis. These techniques confirm the uniform dispersion of metal oxides, formation of crystalline phases, and high porosity of the composite. Electrochemical measurements further demonstrate the catalyst's enhanced activity and durability in alkaline media, validating the effectiveness of this biomass-based hybrid architecture for oxygen evolution catalysis.

-

Alkali lignin (AL) was supplied by Shandong Longli Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shandong, China), with an average molecular weight of 6,400 g mol–1. Methanol (chromatography grade, ≥ 99.9%), N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, GC, > 99.9%), iron acetylacetonate (98%), nickel(II) acetylacetonate (95%), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, AR, 96%), and ethanol (C2H5OH, AR, moisture content ≤ 0.3%) were supplied by Shanghai Aladdin Bio-Chemical Technology Co., Ltd., China. Ammonium formate (ultra-pure, ≥ 99.0%), polyacrylonitrile (PAN, average Mw 150,000), and potassium hydroxide (KOH, 95%) were supplied by Shanghai Maclin Bio-Chemical Co., Ltd., China. Hydrochloric acid (HCl, AR), and acetone (AR) were purchased from Guangzhou Chemical Reagent Factory, China. Nafion solution (D520, 5 wt%) was provided by DuPont. Carbon paper (TGP-H-060, 20 × 20 cm, 0.19 mm) was produced by Toray Corporation (Japan). All chemicals were used as received without further purification.

Lignin treatment

-

First, 20 g of alkali lignin (AL) was dissolved in 250 mL of 1 M NaOH solution. The pH of the mixture was then adjusted to 12 using NaOH solution and stirred continuously at room temperature for 2 h. Subsequently, a dilute hydrochloric acid solution (pH = 2) was prepared and slowly added to the lignin solution until the pH dropped back to 2. The mixture was placed in an ice bath and allowed to react under continuous stirring for 2 h. It was then transferred to room temperature, and stirring was continued for 24 h to allow the lignin to fully precipitate and separate. The resulting precipitate was washed three times with the aforementioned dilute hydrochloric acid (pH = 2), and deionized water, respectively, and then centrifuged. Finally, the lignin sample obtained by centrifugation was freeze-dried for 24 h to obtain the final processed product.

Catalyst preparation

-

Iron acetylacetonate (0.706 g, 2 mmol), nickel acetylacetonate (0.262 g, 1 mmol), AL (1.673 g), and PAN (1.673 g) were dissolved in 20 mL of DMF, resulting in a polymer (AL and PAN) concentration of 15 wt% in DMF. The resulting solution was stirred at room temperature for 12 h to form a uniform spinning solution. The prepared spinning solution was then injected into a 5 mL syringe equipped with a 22 G stainless steel needle (inner diameter 0.70 mm, length 38 mm). Electrospinning was performed under the following conditions: a voltage of 19 kV, a needle tip-to-aluminum foil receiver distance of 12 cm, and a solution feed rate of 0.6 mL h–1. The resulting lignin fibers were vacuum-dried at 60 °C for 24 h. The dried lignin fibers were then placed in a muffle furnace and pre-oxidized under an air atmosphere with the temperature raised from room temperature to 250 °C at a heating rate of 1 °C min–1, and held at 250 °C for 1 h. Subsequently, the pre-oxidized thermally stabilized lignin fibers were transferred to a tube furnace and heated from room temperature to 800 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere at a rate of 3 °C min–1, followed by isothermal treatment at 800 °C for 2 h to achieve carbonization. Next, the resulting lignin carbon fibers (LCFs) were placed in a muffle furnace and heated from room temperature to 300 °C at a rate of 2 °C min–1 under an air atmosphere, followed by isothermal treatment at 300 °C for 2 h, yielding the transition metal-loaded lignin carbon fiber catalyst, denoted as NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs. The Fe3O4@LCFs and NiO@LCFs catalysts were prepared using an identical procedure, with the only difference being the metal precursor used (iron acetylacetonate or nickel acetylacetonate, respectively), while all other steps remain unchanged. Structural characterisation parameters, electrochemical measurement methods, and density functional theory calculation method are detailed in Supplementary File 1.

-

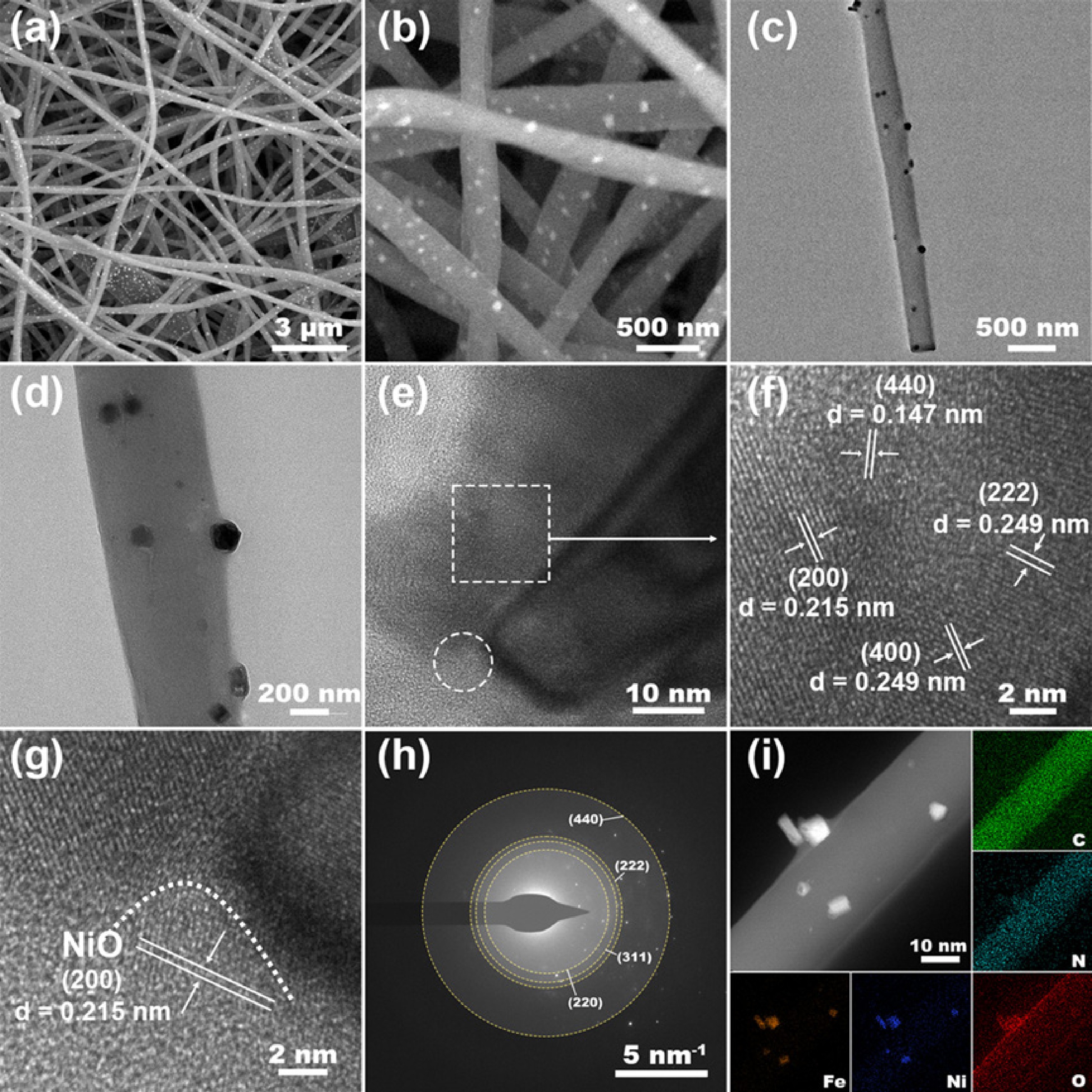

To prepare the lignin-derived carbon fibers (LCFs) catalyst, the precursor solution was first electrospun into a three-dimensional (3D) membrane composed of one-dimensional carbon nanofibers embedded with nickel and iron. Subsequently, pre-oxidation was performed to stabilize the microstructure and prevent fiber fusion during the following carbonization step. Finally, the material underwent thermal carbonization to form the NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs catalyst, featuring NiO/Fe3O4 nanoparticles anchored onto the lignin-derived carbon fibers (Fig. 1). As shown in Fig. 2, a series of microscopic characterizations were conducted to reveal the morphology, crystal structure, and elemental distribution of the NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs catalyst. Figure 2a, b show the low-magnification and high-magnification SEM images of NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs, respectively. The analysis results indicate that through electrospinning and subsequent carbonization processes, the lignin precursor was successfully converted into a carbon matrix (LCFs) with a fibrous morphology. Additionally, metal oxide (NiO/Fe3O4) particles are uniformly loaded onto these well-defined carbon fiber carriers. The catalyst exhibits a unique 'embedded' structural feature, where cubic-shaped metal oxide particles are firmly embedded within a relatively uniform carbon fiber network. Numerous nanoscale particles are uniformly distributed on the fiber surfaces, indicating successful spatial confinement of metal precursors during electrospinning and their subsequent in situ conversion to metal oxides during thermal treatment. TEM images in Fig. 2c, d further corroborate the SEM observations, clearly revealing the embedded structure of metal oxide particles on the LCFs carrier. TEM results indicate that the LCFs carrier provides an excellent dispersion platform for spinel-type metal oxide (NiO/Fe3O4) nanoparticles, suggesting strong interactions between the modified spinel nanoparticles and the carbon nanofiber carrier. Additionally, the high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) image of NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs (Fig. 2f) successfully resolved the lattice fringes of the Fe3O4 spinel phase, clearly identifying its (511), (400), (440), and (311) crystal planes. Notably, a magnified observation of the region marked with a white circle in Fig. 2e shows that the lattice fringes in this region appear blurred (Fig. 2g), forming a distinct interface with the adjacent clear Fe3O4 spinel crystal plane regions. In the interfacial region (Fig. 2g), lattice distortion is observed, and the (200) plane of NiO is clearly resolved, demonstrating the formation of a nanoscale heterojunction between NiO and Fe3O4. This interface is expected to facilitate interfacial electron transfer and boost OER activity. The selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern shown in Fig. 2h further confirms the crystal structure of the Fe3O4 spinel phase, with diffraction rings corresponding to the (222), (220), (440), and (311) crystal planes. Elemental distribution information is provided by the energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) surface scan pattern in Fig. 2i. The pattern clearly shows that C, O, and N elements exhibit highly uniform spatial distribution on the LCFs carrier, while Fe and Ni elements are primarily enriched in the embedded particle regions, further validating that metal particles are loaded onto the carbon fiber carrier in an embedded mode. It is worth emphasizing that the EDS results confirm the presence of abundant in situ-doped nitrogen (N) elements on the LCFs carrier, whose origin can be attributed to polyacrylonitrile (PAN) in the precursor. This in situ N doping not only significantly enhances the conductivity of carbon fibers but also improves the metal coordination ability of the catalyst by regulating the local electronic structure. Additionally, N doping effectively improves the inherently weak conductivity of the NiO/Fe3O4 spinel phase, thereby facilitating rapid electron transfer during the catalytic reaction and significantly enhancing the overall electrochemical performance of the catalyst[41,42]. In summary, this study successfully constructed an integrated catalyst (NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs) composed of cubic spinel-type metal oxide (NiO/Fe3O4) nanoparticles uniformly embedded in a nitrogen-doped carbon fiber (LCFs) carrier. Its unique embedded structure, heterojunction interface, and effective nitrogen doping synergistically form the foundation for the material's outstanding catalytic performance.

Figure 2.

Structural and elemental characterization of NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs: (a), (b) Low and high magnification SEM images of NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs; (c)–(g) TEM image, HRTEM image of NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs; (h) Electron diffraction pattern of NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs; (i) EDS elemental mapping images of C, N, O, Fe, and Ni elements.

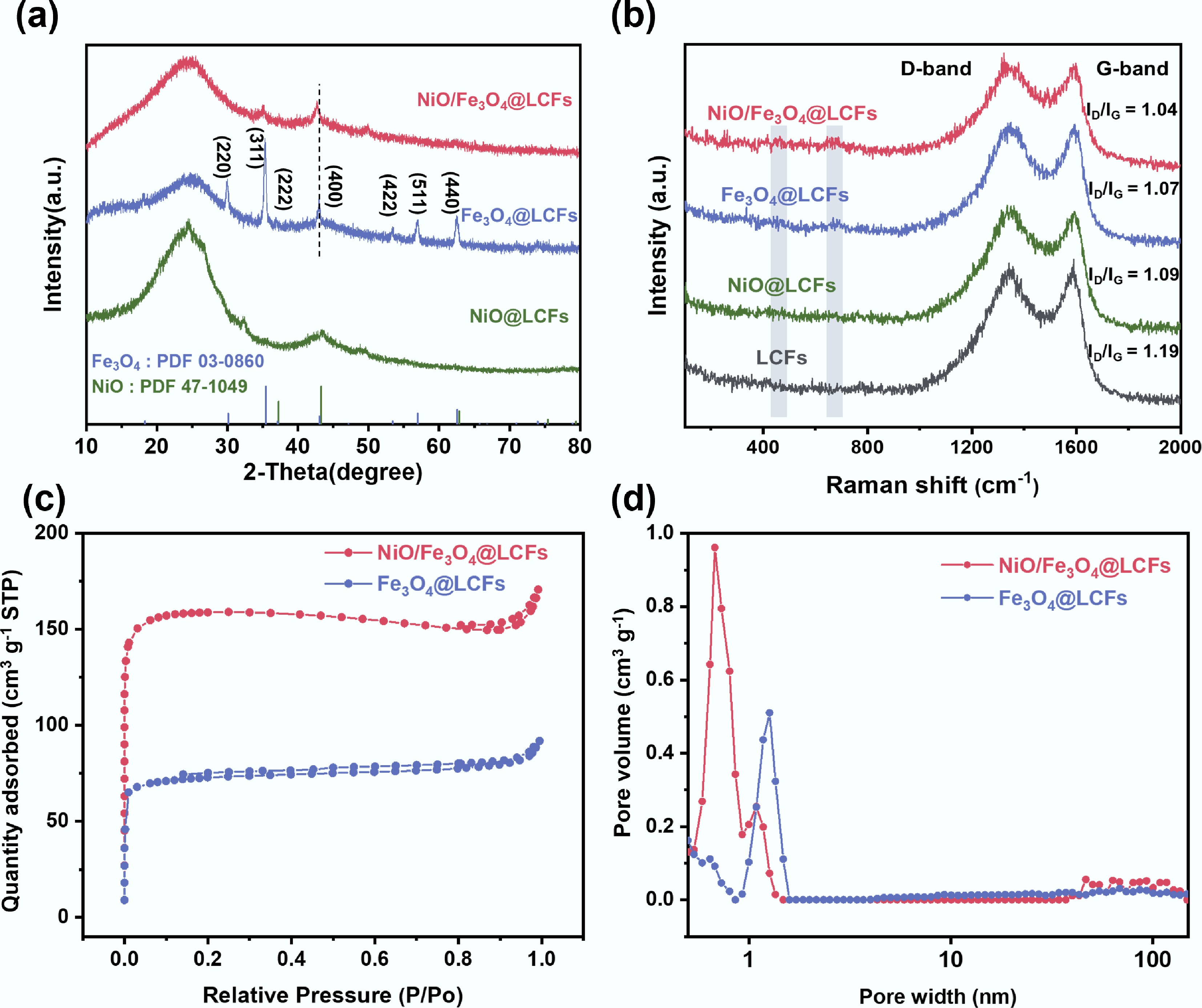

The structural composition of the catalyst was elucidated by X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis (Fig. 3a). For Fe3O4@LCFs, the diffraction peaks appear at 30.1, 35.4, 37.1, 43.1, 53.4, 57.2, and 62.8°, corresponding to the (220), (311), (222), (400), (422), (511), and (440) crystal planes, confirming the presence of the Fe3O4 inverse spinel structure. In the XRD pattern of NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs, the characteristic peaks of Fe3O4, such as the (311), (440) characteristic peaks of Fe3O4, are also clearly observed in the XRD pattern of NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs. Notably, compared to Fe3O4@LCFs, the diffraction peak of the (400) crystal plane in NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs shifts to the left, indicating that some Ni may occupy part of the tetrahedral center sites in Fe3O4[43,44]. Additionally, NiO@LCFs exhibits a (200) diffraction peak attributable to NiO (PDF#47-1049). However, in both NiO@LCFs and NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs, the intensity of the NiO characteristic peaks is relatively weak, which may be due to the broad diffraction peaks of the amorphous carbon substrate masking some of the characteristic signals of the metal oxides[31]. Combining the above XRD results with the TEM observations of NiO and Fe3O4 forming a heterojunction and being embedded in the carbon fibers, it can be concluded that the NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs catalyst with a spinel structure loaded on lignin-based carbon fibers (LCFs) has been successfully synthesized. The interaction between the two metal oxides may play a significant role in enhancing the electrocatalytic-related physical properties of the material, such as electron transport.

Figure 3.

Structural and physicochemical properties of the catalysts: (a) XRD patterns; (b) Raman spectra; (c) Specific surface area of Fe3O4@LCFs, NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs; (d) Pore size distribution of Fe3O4@LCFs, NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs.

Raman spectroscopy was used to assess the graphitization degree and defect characteristics of the catalyst's carbon matrix (Fig. 3b). Characteristic peaks were observed near ~1,350 cm–1 (D band) and ~1,580 cm–1 (G band) in all samples. The D band originates from sp3-hybridized carbon, reflecting defects or disordered structures in the material; the G band originates from sp2-hybridized carbon, representing ordered graphitized structures. The ratio of D band intensity to G band intensity (ID/IG) can be calculated to quantify the degree of disorder in the material. A higher ID/IG ratio indicates a greater contribution from defects or disordered structures in the material[45]. The ID/IG ratio of NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs (1.04) is lower than that of the metal-free (LCFs) and single-metal (NiO@LCFs and Fe3O4@LCFs) catalysts, indicating that the introduction of transition metal oxides (NiO, Fe3O4) effectively enhances the graphitization degree of the carbon matrix. This is attributed to the transition metal-catalyzed conversion of amorphous carbon to graphitized carbon, which may also improve the overall conductivity of the composite material[46]. Additionally, in the Raman spectra of metal-containing catalysts (NiO@LCFs, Fe3O4@LCFs, NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs), additional characteristic peaks appeared around 480 and 680 cm–1, which were not observed in the absence of metal catalysts. These peaks correspond to the typical vibrational modes of Ni–O or Fe–O bonds, consistent with the detection of metal oxide phases in the XRD results.

Nitrogen (N2) adsorption/desorption isotherms indicate that at a relative pressure (P/P0) of 0.1, the isotherm rises, with NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs exhibiting the largest specific surface area (495 m2 g–1) (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Table S1). Additionally, the pore size distribution includes micropores and mesopores (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Table S1), and compared to Fe3O4@LCFs, NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs exhibits a larger pore structure. This pore structure facilitates electrolyte penetration, and provides a larger surface area for high-load active electrode materials[47]. Therefore, the reasonable structural design enables NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs to expose abundant active sites and exhibit rapid mass transfer pathways and high conductivity, thereby promoting rapid electrolyte penetration/diffusion and accelerating ion/electrolyte transport. It also guaranteed excellent electron conduction and allowed the generated O2 to spread freely[48].

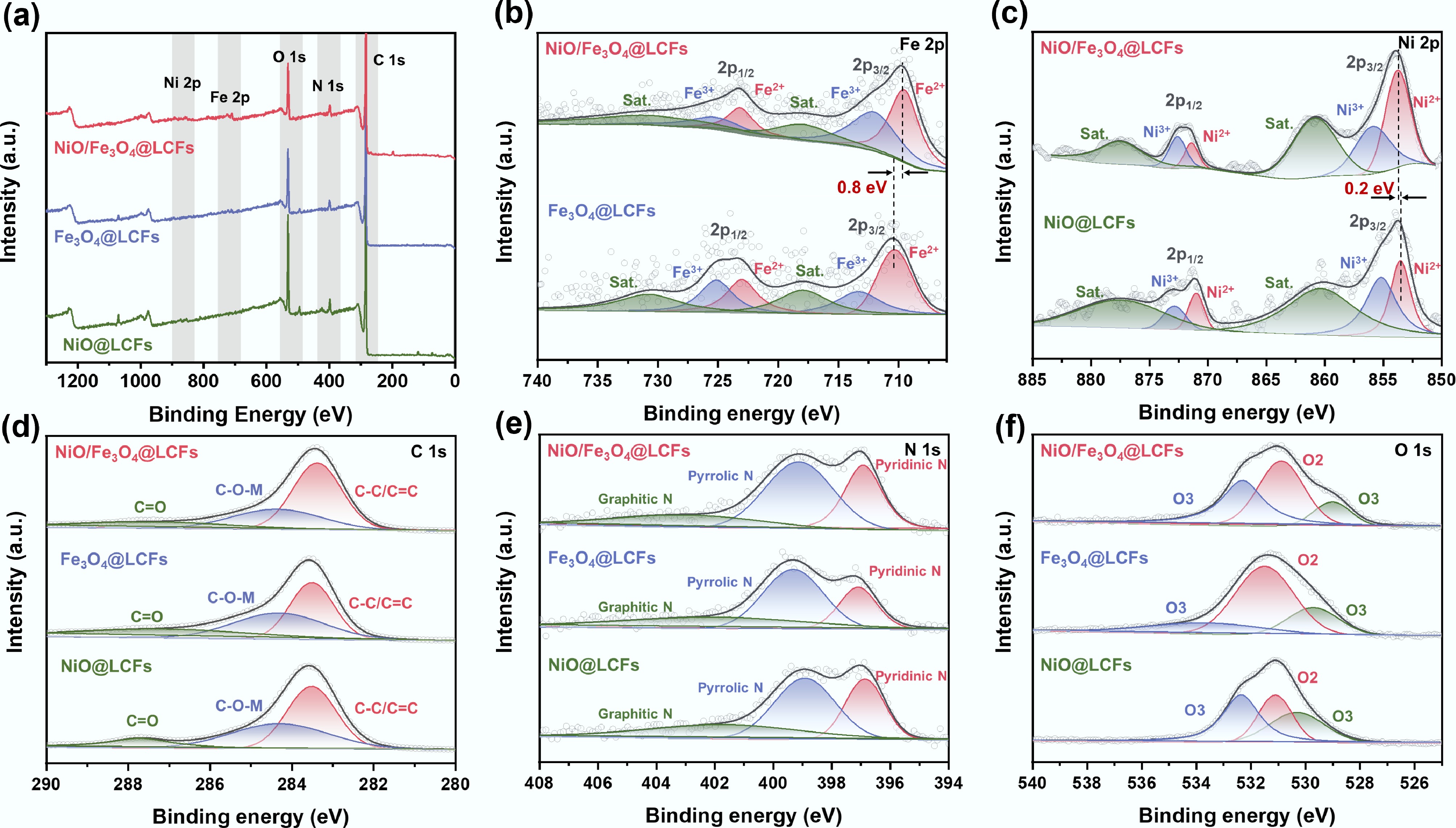

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was used to analyze NiO@LCFs, Fe3O4@LCFs, and NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs to gain a deeper understanding of their surface valence states and chemical composition. The XPS spectra of NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs showed the presence of C, N, O, Fe, and Ni (Fig. 4a). In the Fe 2p spectrum, two subpeaks resulting from spin-orbit splitting indicate Fe3+ (725.2, 712.0 eV) and Fe2+ (723.1, 709.5 eV). Additionally, two broad peaks at 730.7 and 717.9 eV, were identified as typical satellite peaks (Sat.) of Fe 2p 1/2 and Fe 2p 3/2(Fig. 4b)[49,50]. Compared to Fe3O4@LCFs, the Fe 2p peaks of NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs are shifted 0.8 eV toward lower energy. This is because the introduction of Ni atoms may have occupied some of the tetrahedral sites originally occupied by Fe atoms, leading to a reduction in Fe2+ content. This indicates that the introduction of Ni has caused a redistribution of charge structure in the spinel, consistent with the shift in XRD diffraction peak signals. The Ni 2p spectrum also exhibits similar characteristic peaks: Ni3+ (871.4 and 853.7 eV), and Ni2+ (872.6 and 855.9 eV) (Fig. 4c)[16]. Similarly, compared to NiO@LCFs, the Ni 2p spectrum exhibits a minor shift of 0.2 eV toward higher energies, indicating that the electronic structure of Ni in the Ni oxide has changed after the introduction of Fe3O4[51]. This alteration enhances electron transfer from Ni sites to Fe sites, leading to an increase in the content of high-valent Ni species—active sites for the oxygen evolution reaction (OER)—thereby improving electrocatalytic performance. These results reveal the coexistence of NiO and Fe3O4 spinel in the NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs catalyst.

Figure 4.

XPS analysis of the surface composition and chemical states of NiO@LCFs, Fe3O4@LCFs, and NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs: (a) survey scan spectra; (b) Fe 2p; (c) Ni 2p; (d) C 1s; (e) N 1s; (f) O 1s.

In the C 1s spectrum (Fig. 4d), peaks at 283.4, 284.3, and 287.4 eV correspond to C=C/C–C, C–O–M, and C–O/C–N, respectively. This indicates successful carbonization of lignin, with lignin and PAN serving as the carbon and nitrogen sources for LCFs formation[31,52]. Fig. 4e shows the N 1s spectrum, which can be divided into three peaks at 396.9, 399.1, and 401.9 eV, corresponding to pyridine–N, pyrrole–N, and graphite–N, respectively[53−55]. Since pyridine–N is an electron-withdrawing group, it can adjust the local electronic structure of C. Compared to Fe3O4@LCFs, NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs has a higher content of pyridine–N with lone pair electrons, providing effective coordination sites with adjacent metal species, making it an effective electrocatalytic active site for OER[56]. Figure 4f shows the O 1s spectrum. At 529.0 eV, a distinct binding peak corresponding to oxygen atoms (O1) bound to metal can be observed. The peak at 531.0 eV is associated with defect sites of low-coordination oxygen (O2), while the peak at 532.3 eV indicates hydroxyl species adsorbed on the deoxidized surface (O3)[57] (Fig. 3f). Notably, the O 1s spectrum of NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs exhibits a distinct peak shift toward lower binding energies. The formation of the NiO/Fe3O4 heterostructure indicates strong electronic coupling between Ni, Fe, and O, further facilitating rapid electron transfer at the interface[58].

OER performance evaluation of NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs

-

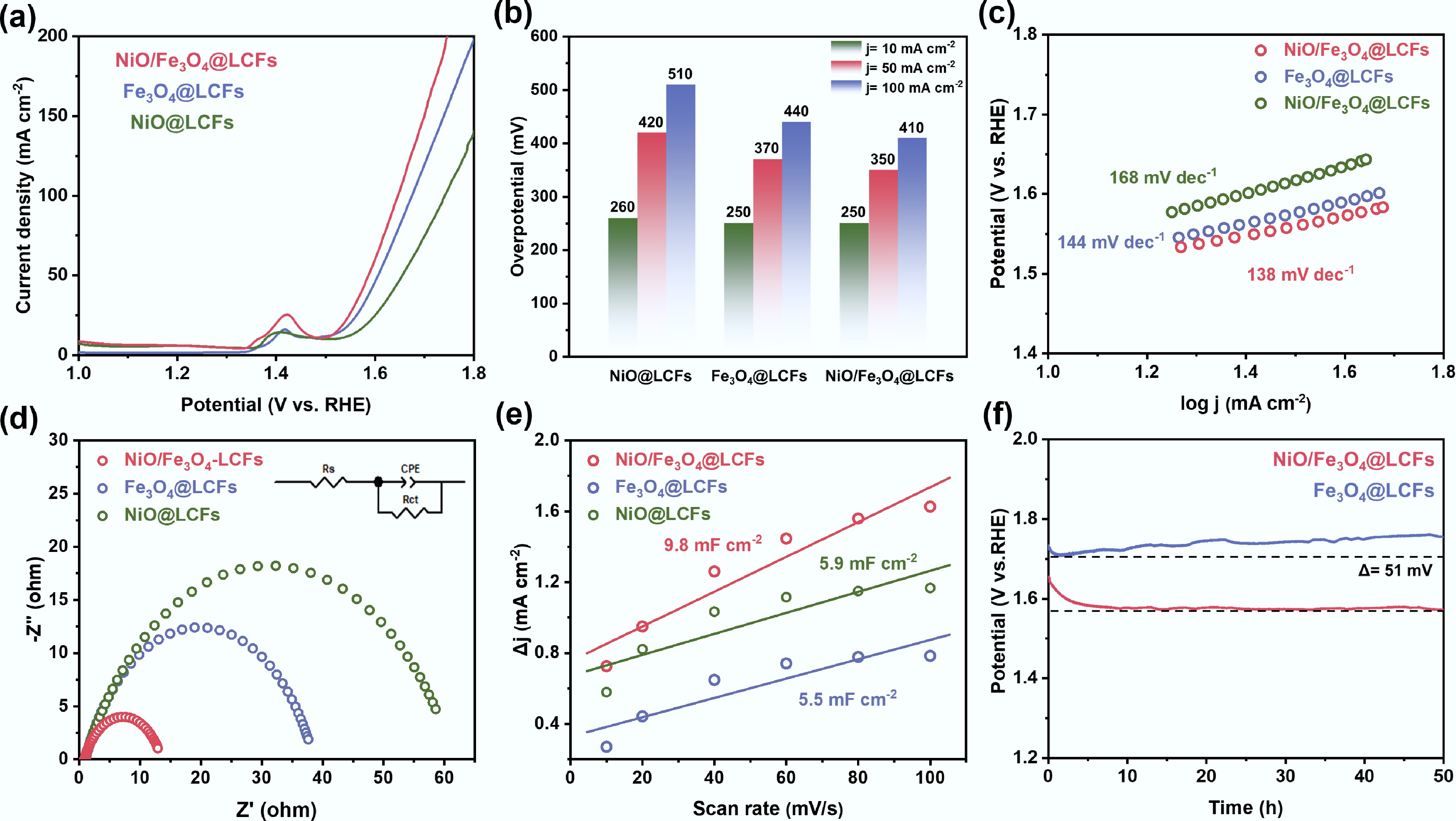

In a 1.0 M KOH electrolyte, using a standard three-electrode system, the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) polarization curves of NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs and other reference catalysts were tested by linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) at a scan rate of 2 mV s–1. Figure 5a shows the LSV curves of Fe3O4@LCFs, NiO@LCFs, and NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs. Compared to the single-metal oxide catalysts (NiO@LCFs and Fe3O4@LCFs), NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs exhibited the most outstanding OER electrocatalytic activity. This performance enhancement stems from the excellent electronic synergy between the two metal oxides, which effectively promotes the OER process. Figure 5b summarizes the overpotentials (η) at different current densities. At a current density of 10 mA cm–2, the overpotentials of NiO@LCFs, Fe3O4@LCFs, and NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs are similar, at 250, 250, and 260 mV, respectively. However, at higher current densities (50 and 100 mA cm–2), the overpotentials of NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs significantly decrease to 350 and 410 mV, respectively, showing a clear advantage over Fe3O4@LCFs (370, 440 mV) and NiO@LCFs (420 mV, 510 mV). The Tafel slope directly reflects the kinetics of the OER reaction, with smaller values indicating faster kinetics. The Tafel curves, calculated from the LSV curves, are shown in Fig. 5c. The Tafel slope of NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs (138 mV dec–1) is significantly lower than that of NiO@LCFs (168 mV dec–1), and Fe3O4@LCFs (144 mV dec–1), further confirming that NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs exhibits faster OER reaction kinetics. As analyzed above, this kinetic advantage can be attributed to the synergistic interaction between the electronic and geometric structures of the bimetallic oxides. Additionally, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements revealed the intrinsic charge transfer characteristics of the catalyst. The Nyquist plot in Fig. 5d shows that the semicircle diameter (corresponding to the charge transfer resistance Rct) of NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs is significantly smaller than that of other catalysts. Based on equivalent circuit fitting, the Rct value of NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs is only 13.0 Ω, indicating faster charge transfer kinetics. Electrochemical surface area (ECSA) is an important indicator for evaluating the number of active sites on a catalyst, and it usually has a linear relationship with electrochemical double layer capacitance (Cdl)[59]. Cdl values were calculated via cyclic voltammetry (CV) testing at different scan rates (1.009 to 1.207 V vs RHE) (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Figs S1–S3). The Cdl of NiO/ Fe3O4@LCFs is 9.8 mF cm–2, higher than that of Fe3O4@LCFs (5.9 mF cm–2), and NiO@LCFs (5.5 mF cm–2). This is primarily attributed to its high-surface-area porous structure, which provides a richer supply of active sites. The long-term stability of the catalyst is a critical indicator for practical applications. Chronopotentiometric testing was conducted at a high current density of 100 mA cm–2 (Fig. 5f). After 50 h of continuous operation, the operating voltage of Fe3O4@LCFs increased significantly by 51 mV, while the voltage of NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs remained largely stable, demonstrating excellent stability.

Figure 5.

Electrochemical properties of NiO@LCFs, Fe3O4@LCFs, and NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs: (a) LSV curves; (b) Overpotential required at j = 10, 50, and 100 mA cm−2; (c) Tafel plots; (d) Nyquist plots; (e) Scan rate as a function of ECSA of bilayer capacitance; (f) Stability of Fe3O4@LCFs and NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs at a current density of 100 mA cm−2.

OER reaction mechanism on NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs catalyst

-

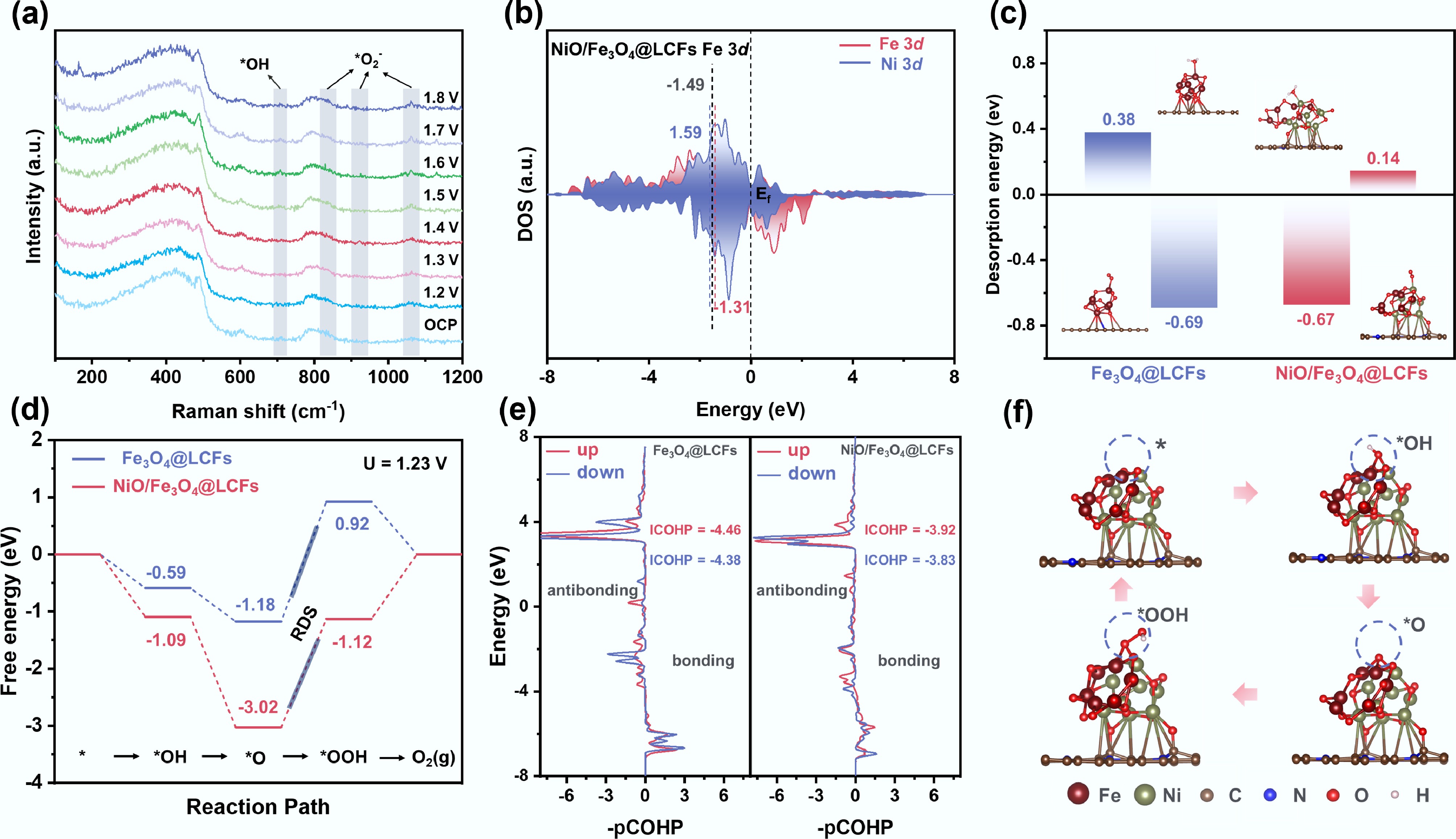

Understanding the reversible conversion of oxygen at atomic and molecular levels is crucial for elucidating catalytic reaction mechanisms. Figure 6a displays the in situ Raman spectra of NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs in 1 mol L−1 KOH electrolyte, clearly documenting the characteristic evolution of OER intermediates with potential. As the potential gradually increases, the positions and intensities of the bulk vibration peaks of NiO and Fe3O4 remain nearly unchanged, indicating no significant structural rearrangement in the metal oxide frameworks[57]. However, once the potential reaches 1.5 V (vs RHE), new Raman responses simultaneously emerge at 708, 808, 921, and 1,063 cm−1. The peaks at 708 and 1,063 cm−1 correspond to the characteristic stretching vibrations of OH− and *O2− oxygen-containing intermediates, respectively, which continuously intensify and sharpen with increasing overpotential[60,61]. These results consistently indicate that the OER reaction follows an adsorption-evolution mechanism (AEM) pathway, wherein OH−/*O2− gradually accumulate on the catalyst surface and directly participate in the oxygen evolution process.

Figure 6.

Mechanistic insights into the enhanced OER activity via in situ spectroscopy and DFT calculations. (a) In situ Raman spectrum of the OER on NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs in 1.0 M KOH; (b) Density of states onto Fe and Ni 3d orbitals for NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs; (c) Adsorption energies of H2O and O2 on Fe3O4@LCFs and NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs; (d) Gibbs free energy change diagram of Fe3O4@LCFs, and NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs during the OER process; (e) The pCOHP plot of the O–OH bond after OOH adsorbs on Fe3O4@LCFs and NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs; (f) Interface configuration of NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs at four different stages during the OER.

To corroborate the experimentally inferred AEM route, Fe3O4@LCFs and NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs models were constructed based on density functional theory (DFT) calculations. Stable adsorption configurations of key oxygen evolution reaction (OER) intermediates (OH, O, and OOH) were optimized, and their corresponding Gibbs free energy changes were calculated. The OER pathway follows the adsorption evolution mechanism (AEM): active sites first adsorb OH− ions, which undergo deprotonation to form O; subsequent O–O bond coupling generates OOH; finally, O2 molecules desorb from the catalyst surface via a second deprotonation. Moderate adsorption energy between oxygen intermediates and active sites facilitates OER kinetics[62].

The electronic structures of both models were analyzed. Bader charge calculations indicate electron transfer from NiO to Fe3O4 in NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs, increasing the charge on Fe and yielding an average valence state of +0.93, lower than that in Fe3O4@LCFs (+1.05)[43] (Supplementary Fig. S4). An additional 1.89 |e| flows from the N-doped lignin-derived carbon layer into the oxide cluster, further enriching the electron density of the active phase (Supplementary Fig. S5). This electronic structure change directly affects the d-band center position: as shown in Fig. 6b and Supplementary Figs S6–S8, the d-band center of Fe in Fe3O4@LCFs (–1.14 eV) is higher than that in NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs (–1.31 eV). Meanwhile, the d-band center of Ni in NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs is –1.59 eV, and the overall system d-band center is –1.49 eV. These results suggest that Ni introduction weakens the adsorption strength of certain oxygen intermediates, as overly strong adsorption is detrimental to intermediate evolution[63]. The H2O adsorption energy on both catalysts was calculated. The results showed a significantly higher H2O adsorption energy on NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs than on Fe3O4@LCFs. Notably, H2O primarily adsorbs on Ni sites, indicating that the NiO/Fe3O4 heterojunction promotes electron transfer, effectively activating Ni sites for H2O adsorption. Meanwhile, O2 adsorption energy on NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs is lower than on Fe3O4@LCFs, indicating easier O2 desorption from the NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs surface. This optimized H2O adsorption and O2 desorption behavior collectively enhances the OER kinetics of NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs (Fig. 6c).

Figure 6d presents the OER free energy step diagrams for both catalysts. The rate-determining step (RDS) for both is *O → *OOH. Crucially, the RDS free energy change (ΔGRDS) for NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs (1.9 eV) is significantly lower than that for Fe3O4@LCFs (2.1 eV), indicating superior OER activity of NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs. Bader charge and differential charge analysis further reveal that *OOH gains more electrons on NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs (0.42 |e| vs 0.35 |e| for Fe3O4@LCFs), signifying stronger interactions between *OOH and the NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs active sites (Supplementary Fig. S9). Crystal orbital Hamiltonian population (COHP) analysis of OOH interactions with both catalysts shows that for both spin-up and spin-down, the integrated COHP (ICOHP) values for the O–O bond in *OOH on NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs (–3.92 and –3.83) are greater (less negative) than those on Fe3O4@LCFs (–4.46 and –4.38) (Fig. 6e). This indicates a weaker O–O bond in *OOH on NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs, meaning the *O → *OOH step is more favorable, consistent with the reduced RDS energy barrier.

In summary, by studying the evolution of different intermediate configurations during OER (Fig. 6f), the NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs interface, with the lowest energy barrier, was identified as an efficient electroactive site. This interface allows optimal regulation for moderate adsorption of reaction intermediates and desorption of products.

-

In conclusion, a highly active and stable OER electrocatalyst has been developed—NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs—by embedding NiO and Fe3O4 nanoparticles within a nitrogen-doped lignin-derived carbon fiber matrix via electrospinning and controlled thermal treatment. Structural analysis confirmed the formation of spinel-phase metal oxides and the construction of a nanoscale NiO/Fe3O4 heterojunction, while EDS mapping and XPS revealed strong metal–carbon interactions and successful in situ nitrogen doping. The optimized NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs catalyst delivered superior electrochemical performance, including a low overpotential of 250 mV at 10 mA cm–2, a small Tafel slope of 138 mV dec–1, and a high double-layer capacitance of 9.8 mF cm–2. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) further confirmed its low charge-transfer resistance, while chronoamperometric tests showed remarkable stability over 50 h with minimal voltage decay at 100 mA cm–2. These results demonstrate that the combination of a renewable carbon fiber scaffold, in situ-formed bimetallic oxide heterojunctions, and nitrogen doping synergistically enhances the intrinsic activity and durability of the catalyst. This work offers a green and scalable strategy for designing next-generation biomass-based electrocatalysts for water splitting applications.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/bchax-0025-0011.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: investigation: Zeng X, Pan Y, Qi Y, Qin Y; visualization: Zeng X, Qin Y, Qiu X; methodology: Pan Y, Qi Y; formal analysis: Pan Y, Qi Y, Qin Y, Qiu X; supervision: Qin Y, Qiu X; writing—review and editing: Zeng X; study design: Qiu X. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22422802, U23A6005, and 22408057).

-

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

-

NiO/Fe3O4 nanoparticles embedded in N-doped lignin-derived carbon fibers (NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs).

Co-action of embedded nanoparticles and conductive N-doped carbon network delivers abundant active sites, facilitated electron/ion transfer, and robust structural stability.

NiO/Fe3O4 heterojunction accelerates OER kinetics via facilitated charge transfer, modulated d-band center, and balanced H2O*/O2* adsorption-desorption.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Supplementary File 1 Supplementary experimental section to this study.

- Supplementary Table S1 Physicochemical properties of Fe3O4@LCFs and NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 The ECSA of NiO@LCFs.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 The ECSA of Fe3O4@LCFs.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 The ECSA of NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs.

- Supplementary Fig. S4 Valence states of Fe atoms in Fe3O4@LCFs and NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs.

- Supplementary Fig. S5 Differential charge density of NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs.

- Supplementary Fig. S6 Density of states onto Fe 3d orbitals for Fe3O4@LCFs.

- Supplementary Fig. S7 Density of states of Fe3O4@LCFs.

- Supplementary Fig. S8 Density of states of NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs.

- Supplementary Fig. S9 The differential charge density plot of OOH adsorbed on Fe3O4@LCFs and NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zeng X, Pan Y, Qi Y, Qin Y, Qiu X. 2025. Lignin-derived carbon fibers loaded with NiO/Fe3O4 to promote oxygen evolution reaction. Biochar X 1: e011 doi: 10.48130/bchax-0025-0011

Lignin-derived carbon fibers loaded with NiO/Fe3O4 to promote oxygen evolution reaction

- Received: 26 July 2025

- Revised: 06 October 2025

- Accepted: 05 November 2025

- Published online: 27 November 2025

Abstract: The sluggish kinetics and high overpotential of the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) remain key challenges limiting the efficiency of alkaline water electrolysis. Developing cost-effective, durable, and high-performance electrocatalysts from sustainable resources is therefore of great significance. Herein, we report a NiO/Fe3O4 heterojunction catalyst uniformly anchored on lignin-derived carbon fibers (NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs), synthesized via an integrated electrospinning–preoxidation–carbonization strategy using alkali lignin and PAN as dual carbon–nitrogen sources. The embedded NiO/Fe3O4 nanoparticles and nitrogen-doped carbon fiber network synergistically provide abundant active sites, rapid electron/ion transport, and strong structural stability. Benefiting from this architecture, NiO/Fe3O4@LCFs exhibits a low overpotential of 250 mV at 10 mA cm–2 and excellent durability with less than 10 mV degradation after 50 h at 100 mA cm–2. The present approach demonstrates a scalable and renewable route to design efficient electrocatalysts by integrating biomass carbon supports with engineered bimetallic oxide interfaces, offering new insights for green energy conversion technologies.

-

Key words:

- Electrospinning /

- Lignin carbon fibers /

- Spinel /

- Heterostructure interface /

- Oxygen evolution reaction