-

Biochar, a carbon-rich material derived from biomass pyrolysis under limited oxygen, aligns theoretically with CE goals of resource recovery, emissions reduction, and ecosystem regeneration[1]. Nevertheless, centuries of traditional use and surging academic interest have not translated it into real-world integration. Qualitative evidence across recent stakeholder assessments indicates persistent variability in biochar quality due to inconsistent feedstock properties and uneven reactor performance, particularly in small-scale systems. End-users often report uncertainty about proper application practices and face fragmented supply chains, reinforcing slow adoption. Project developers describe carbon-durability verification as administratively complex, with methodological demands that smaller producers struggle to meet. Producers also characterize markets as unstable, largely because financing and pricing remain tied to fluctuating carbon-credit instruments. Policymakers and practitioners further note regulatory ambiguity around waste classifications and land-application standards, which continues to delay permitting and restrict broader sectoral expansion.

First and foremost, feedstock variability and divergent reaction conditions yield biochars with highly heterogeneous physicochemical properties[2]. Consequently, results obtained in one region or application domain are difficult to replicate elsewhere. Although researchers have attempted to classify biochars by source or pyrolysis temperature, as yet, no universal quality or safety standards exist to refer to. Secondly, the economic viability of biochar remains contested. Market forecasts suggest potential growth, from USD

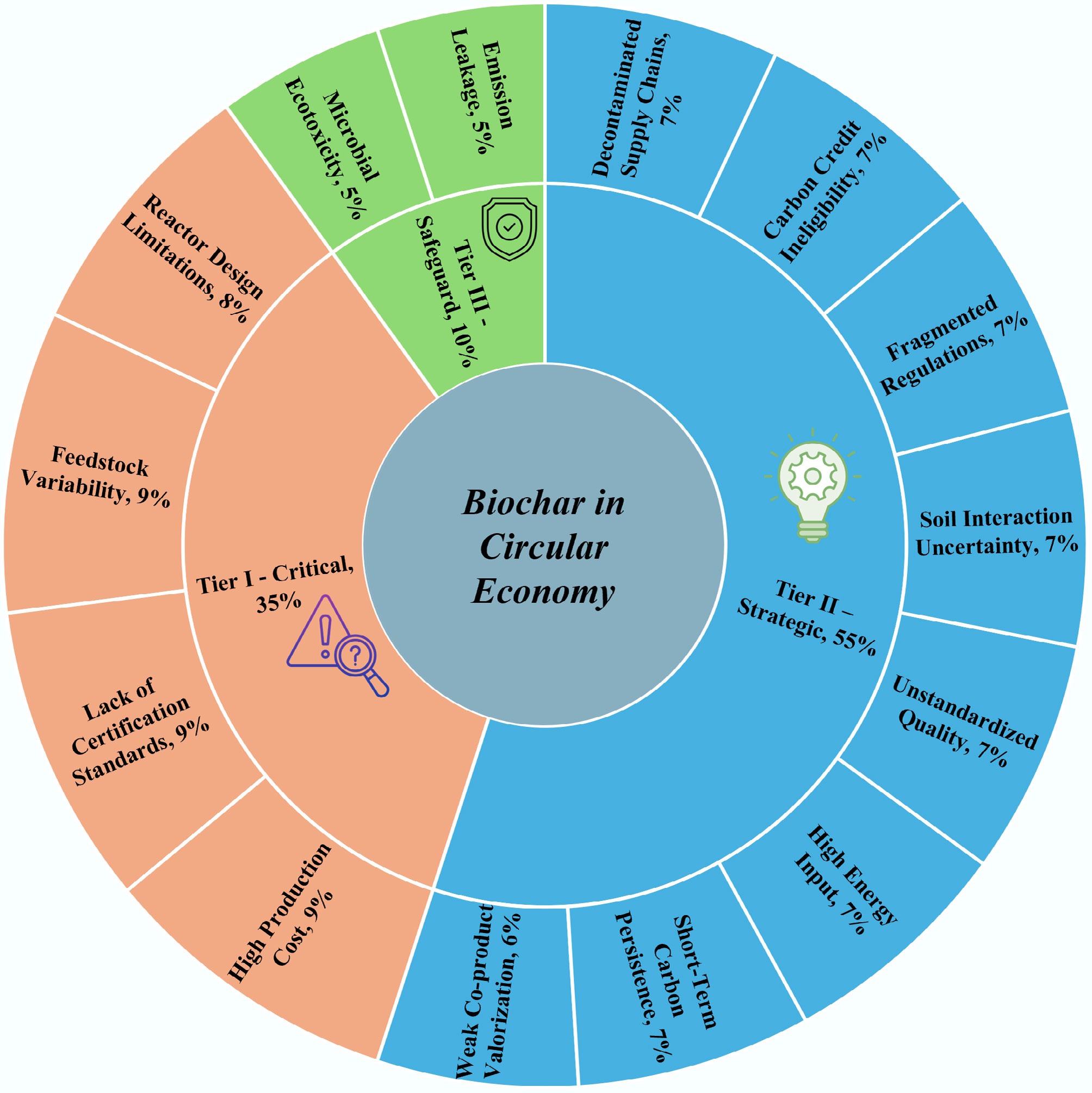

${\$} $ ${\$} $ Moreover, the agronomic and environmental performance of biochar is highly context-specific. Soil type, climate, application rate, and co-treatments all mediate efficacy. Meta-analyses that overlook these dependencies often generate overly generalized claims that lack longitudinal field support[6]. In turn, the dearth of harmonized life cycle assessments (LCAs) and techno-economic analyses (TEAs) leaves decision-making speculative and frequently misaligned with local agroecological realities. Collectively, these technical, regulatory, and economic barriers risk relegating biochar to the periphery of CE systems unless addressed through systemic coordination. Such coordination can be further optimized by applying the analytical hierarchy process in alignment with deployment scenarios[7] (Fig. 1). For example, the pie chart in Fig. 1 illustrates the proposed proportional significance of barriers constraining biochar's integration into the circular economy. Each segment reflects not only the severity of the constraint but also its strategic importance for targeted interventions. The most pressing barriers, categorized as Tier I, Critical Leverage Points (≥ 8%), include feedstock variability (9%), reactor design limitations (8%), lack of certification standards (9%), and high production costs (9%). These high-impact challenges necessitate urgent attention through standardized feedstock processing, modular reactor innovations, harmonized certification frameworks, and cost reduction strategies such as utilizing low-value residues and economies of scale[8]. The Tier II, Strategic Priority Areas (6%–7%) encompass issues such as weak co-product valorization (6%), short-term carbon persistence (7%), unstandardized quality (7%), soil interaction uncertainty (7%), fragmented regulations (7%), decentralized supply chains (7%), carbon credit ineligibility (7%), and high energy input (7%). Addressing these requires systemic interventions, including improved value chain integration, pyrolysis optimization, long-term field validation, harmonized regulatory mechanisms, and logistics coordination. Finally, Tier III, Safeguard and Risk Considerations (< 6%), comprising emissions leakage (5%) and microbial ecotoxicity (5%), though of relatively lower systemic weight, remain essential for ensuring environmental safety and public trust. These can be managed through closed-loop reactor systems and targeted ecological risk assessments. By framing the barriers in these three tiers, the pie chart functions not merely as a descriptive tool but as a diagnostic framework, highlighting both leverage points and systemic vulnerabilities. This tiered prioritization supports research clarity, policy coherence, and technology deployment strategies for advancing biochar within the circular economy.

Figure 1.

Systemic barriers to biochar integration in circular economy pathways. The pie chart illustrates proportional constraints hindering deployment, grouped into three tiers. Tier I (35%) includes feedstock variability, reactor design limitations, lack of certification standards, and high production cost. Tier II (55%) covers high energy input, soil uncertainties, fragmented regulations, decentralized supply chains, unstandardized quality, carbon credit ineligibility, weak co-product valorization, and short-term carbon persistence. Tier III (10%) comprises emissions leakage and microbial ecotoxicity. These barriers highlight leverage points for targeted technological, policy, economic, and environmental interventions.

Biochar's multifunctionality across soil remediation, wastewater treatment, stormwater management, and construction materials is consistently reported in updated reviews, which emphasize its role within integrated circular economy systems[9−11]. The TEA framework further demonstrates that pyrolysis co-products, bio-oil, syngas, and process heat significantly influence system profitability, with detailed evaluations showing that co-product valorization can offset production costs and expand market feasibility[12,13]. Empirical studies of biomass pyrolysis, such as investigations into oil-palm residues and integrated biogas–biochar systems, also validate the economic and energy contributions of these co-products, highlighting their importance in TEA frameworks and deployment planning[14,15]. Collectively, these findings support the inclusion of expanded application domains and co-product economics, strengthening the conceptual linkage between technical bottlenecks, economic incentives, and scalable biochar deployment.

-

If biochar is to move beyond pilot projects and demonstration narratives, deployment must be anchored in integrated assessment frameworks. These must account for both its techno-economic feasibility and its ecological trade-offs across contexts[16]. LCAs, enriched with uncertainty and sensitivity analysis, can reveal variation in greenhouse gas savings, energy use, and co-product valorization. Similarly, TEAs stratified by reactor type, energy inputs, and geographic scale expose where economic thresholds are viable under current or potential policy regimes. For instance, marginal abatement cost curves contextualize biochar within dynamic carbon pricing, highlighting relative competitiveness. Besides, environmental risks must not be sidelined[17]. While often marketed as environmentally benign, biochar may carry contaminants, including heavy metals or persistent organic pollutants, depending on feedstock origin and pyrolysis conditions. High pH values may alter soil microbial communities, and long-term ecological effects remain insufficiently understood[18]. These risks must be systematically incorporated into LCAs and TEAs, rather than being excluded as externalities. Spatial modeling, using remote sensing and GIS, enables region-specific deployment pathways by integrating biomass availability, land use constraints, and logistical considerations. Coupled with dynamic soil carbon models (e.g., RothC, CENTURY), these tools correct simplified sequestration assumptions and facilitate predictive, regionally tailored planning.

Mitigating deployment risks: policy instruments and spatially differentiated strategies

-

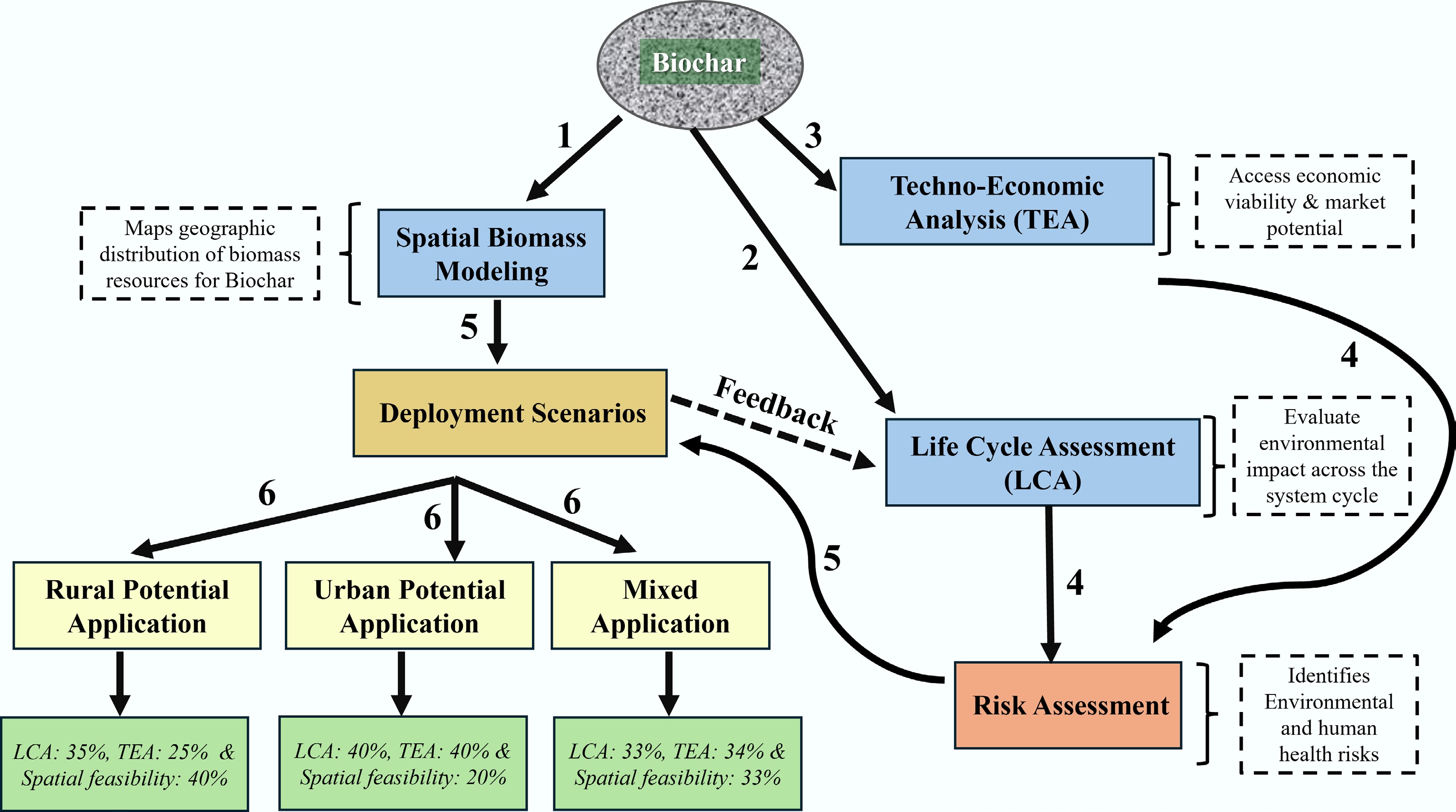

Furthermore, deployment must be coupled with market instruments that internalize externalities and de-risk investment. These include carbon crediting schemes, payments for ecosystem services, public procurement guarantees, and infrastructure subsidies. However, such instruments are not panaceas. They require robust metrics and verification protocols grounded in scientific evidence and calibrated to local conditions. Figure 2 presents an integrated framework combining Spatial Biomass Modeling, LCAs, and TEAs to inform evidence-based biochar deployment. Overall, the flow pattern in the diagram reflects a sequential and integrative systems approach, beginning with Step 1: Spatial Biomass Modeling, which identifies and maps the geographic distribution of biomass resources suitable for biochar production. This modeling feeds into the core component, Biochar, from which the analysis branches into two major streams. Step 2: LCA evaluates the environmental impacts of biochar systems, while Step 3: TEA assesses the economic viability and market potential. Outputs from the LCA inform Step 4: Risk Assessment, addressing potential environmental and human health concerns. A feedback loop from LCA then connects to Step 5: Deployment Scenarios, where insights from earlier assessments are synthesized to design adaptive strategies. Finally, these scenarios inform Step 6: Application Pathways, directing biochar use across three domains: rural, urban, and mixed applications. The structured flow underscores a circular and iterative decision-making framework that integrates sustainability, risk, and economic performance into practical biochar deployment. In rural deployment contexts, spatial feasibility holds the highest weight (~40%) due to infrastructure limitations and the critical role of biomass accessibility and logistics, while LCA and TEA contribute moderately (35% and 25%, respectively). In urban settings, LCA and TEA are equally prioritized (~40% each) owing to stringent regulatory environments and economic constraints, with spatial feasibility being less critical (20%). For mixed or integrated applications, all three factors, LCA, TEA, and spatial modeling, are weighted nearly equally (~33%), reflecting the need for balanced consideration in regional or national deployment strategies. This enables spatially resolved, context-specific strategies to mainstream biochar within circular economy systems. Rural applications of biochar target soil improvement and carbon sequestration using local biomass, while urban applications focus on waste valorization, water treatment, and green infrastructure[19]. Mixed applications bridge rural production and urban use through decentralized systems and regional bioeconomy integration.

Figure 2.

Linking spatial modeling, LCA, and TEA to guide biochar deployment contexts. The framework aligns multi-scalar evidence streams to develop scenario-based strategies. Risk assessment gates each deployment pathway, ensuring safeguards are embedded from the outset.

Inclusively, a specific field-oriented interpretation suggests that spatial feasibility is particularly influential in ecological restoration and environmental geochemistry applications, where biomass availability, site-specific soil properties, and carbon stabilization pathways determine the effectiveness of biochar interventions. The LCA becomes central in sustainable development and carbon-footprint–oriented fields, as these domains prioritize emissions reduction, environmental compliance, and long-term systemic impacts. The TEA holds greater weight in economic planning and resource-management contexts, where cost structures, market readiness, and policy incentives shape deployment viability. When considered together, the near-equal relevance of spatial modeling, LCA, and TEA across environmental restoration, geochemistry, sustainability planning, and economic analysis underscores the need for integrative strategies that balance ecological performance, environmental burdens, and financial feasibility. Such alignment positions biochar as a cross-cutting tool capable of contributing simultaneously to soil rehabilitation, climate-impact mitigation, waste valorization, and the broader transition toward circular and resilient environmental systems.

-

Currently, biochar research and deployment suffer from three mutually reinforcing deficits: fragmented science, inconsistent policy, and an overreliance on techno-optimist narratives. To break this deadlock, biochar must be repositioned. It should be viewed as a systems-level intervention, rather than a stand-alone material or panacea. Achieving this shift requires a coherent and interdisciplinary transition. This entails synthesizing agronomic, ecological, economic, and regulatory domains within integrated governance frameworks. Concepts from socio-technical transitions theory and sustainability science provide useful analytical frameworks for understanding how innovation ecosystems can be better aligned through collaborative processes. These perspectives emphasize the importance of co-producing knowledge among researchers, policymakers, and practitioners to support effective and inclusive sustainability transitions. Biochar should be redefined not as a secondary or experimental output, but as a critical infrastructural component within circular economy frameworks. Advancing this perspective requires robust metrics to evaluate its impact, the establishment of internationally recognized quality standards, the development of adaptive policy instruments, and the integration of risk governance mechanisms into institutional practices. Overall, while the future of biochar depends on our institutional capacity to integrate, regulate, and adapt it within context-sensitive and multi-actor systems, this capacity must be firmly grounded in a rigorous understanding of its chemical potential, which underpins both its functional efficacy and regulatory legitimacy. A coherent strategy grounded in systems thinking is essential for its transition from margin to mainstream in the circular economy.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Muhammad Faheem: methodology, formal analysis, writing−original draft preparation. Bing Wang: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing−review & editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

This work was supported by the Key Project of Science and Technology Department of Guizhou Province (Grant No. ZK[2022]016), the Special Fund for Outstanding Youth Talents of Science and Technology of Guizhou Province (Grant No. YQK2023[014]), and the Science and Technology Support Program of Science and Technology Department of Guizhou Province (Grant No. QKHZC[2025]100).

-

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Faheem M, Wang B. 2026. Biochar in circular economy and sustainable development: addressing technical variability, policy gaps, and sustainability constraints. Biochar X 2: e001 doi: 10.48130/bchax-0025-0014

Biochar in circular economy and sustainable development: addressing technical variability, policy gaps, and sustainability constraints

- Received: 31 October 2025

- Revised: 08 December 2025

- Accepted: 17 December 2025

- Published online: 16 January 2026

Abstract: Biochar exhibits multiple functions and has a long history of application. Its potential for carbon sequestration, soil remediation, and high-value waste disposal has also been extensively demonstrated. However, mainstream research often overstates biochar scalability prospects and pays insufficient attention to structural uncertainty and social ecological trade-offs, resulting in the underutilization of this technology in circular economy and sustainable development strategies. These unresolved challenges, including feedstock heterogeneity, ambiguous life-cycle performance, insufficient policy integration, and misaligned economic signals, collectively hinder its large-scale deployment. This commentary critiques the dominant techno-optimist narratives and brings attention to systemic barriers, particularly technical variability and regulatory incoherence. An integrative approach is advocated that couples spatially resolved techno-economic and life cycle assessments with coherent governance mechanisms. By repositioning biochar as a systems-level intervention, operating across interconnected domains of resource recovery, climate mitigation, and agro-ecological transformation, a more pragmatic roadmap for its deployment within circular economy frameworks is proposed. Scenario-based modeling and spatial risk integration are advanced as tools to contextualize trade-offs and operational constraints, thereby enabling a more grounded and policy-relevant discourse.