-

Biochar, a carbon-rich material produced through the pyrolysis of organic matter such as agricultural waste, forestry residues, and other biomass, has garnered significant attention for its role in soil remediation and contaminant treatment[1]. Its unique physicochemical characteristics, such as high surface area, hierarchical porosity, and strong adsorption affinity, make it highly effective in improving soil quality[2], enhancing crop productivity, and mitigating multiple pollutant impacts[3]. Extensive research has demonstrated its ability to immobilize heavy metals[4], adsorb persistent organic pollutants[5], and buffer soil acidity[6,7], thereby contributing to agricultural sustainability and ecological protection. These well-recognized functions have established biochar as one of the most promising materials for soil and contaminant management.

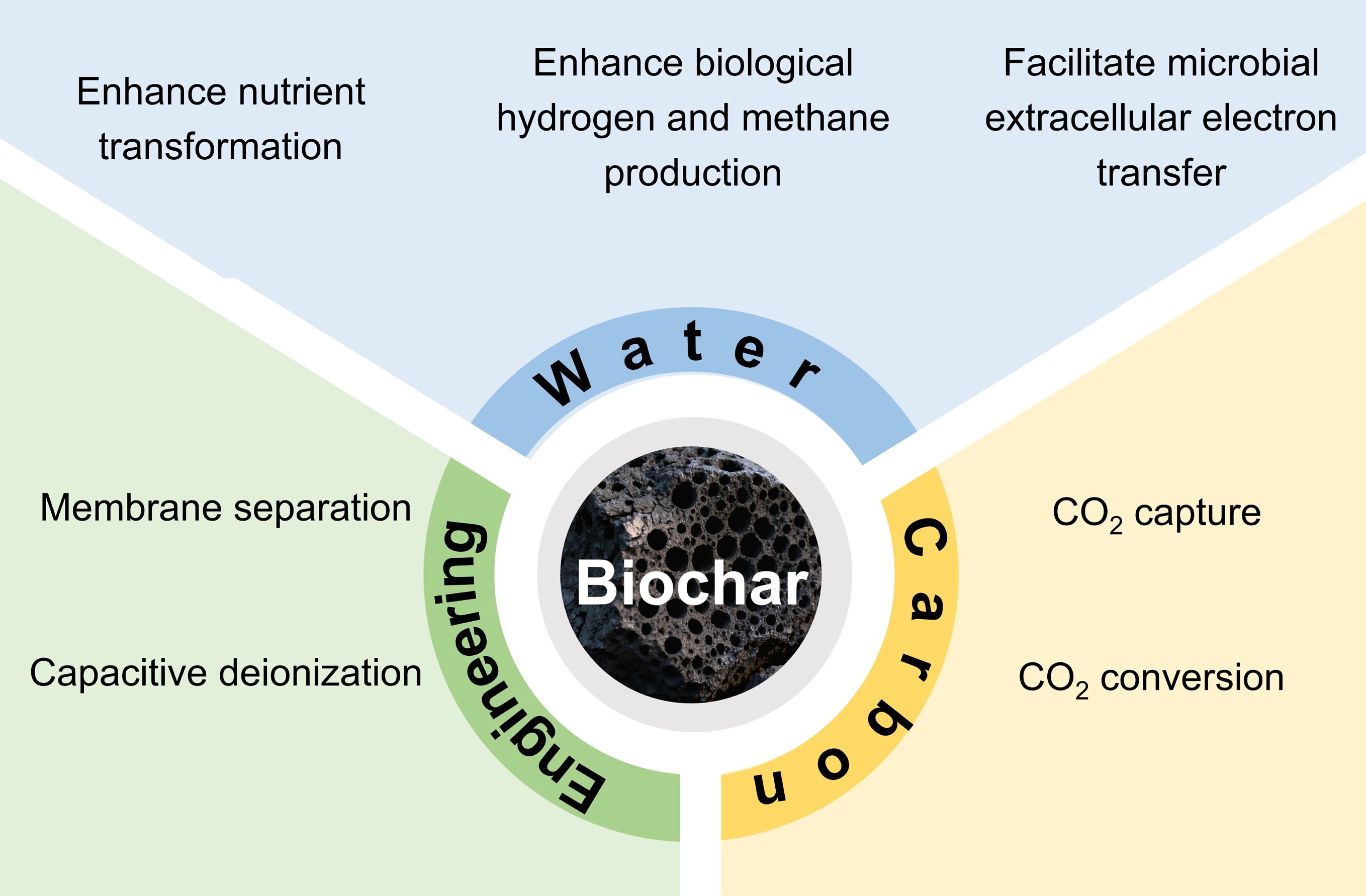

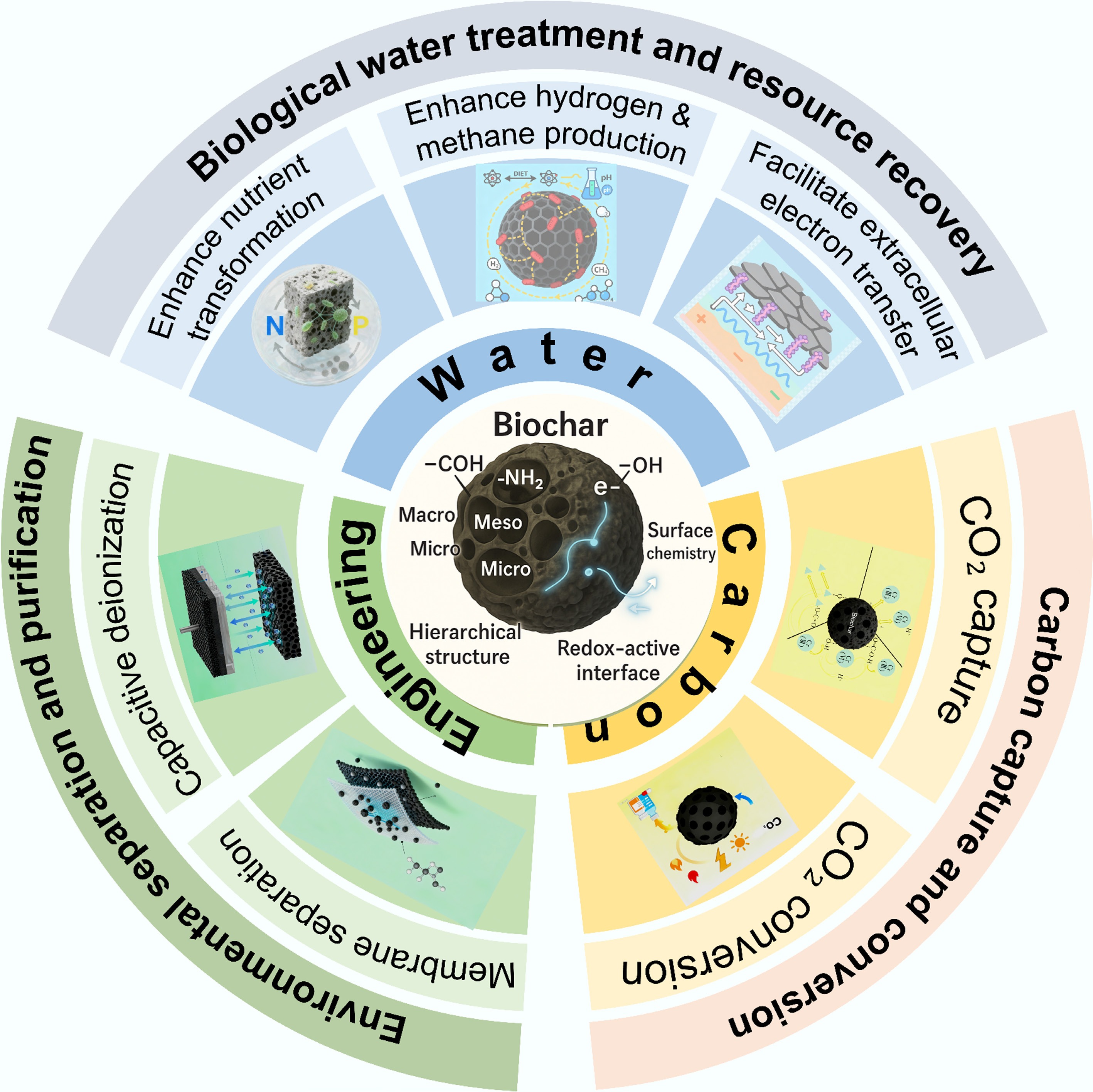

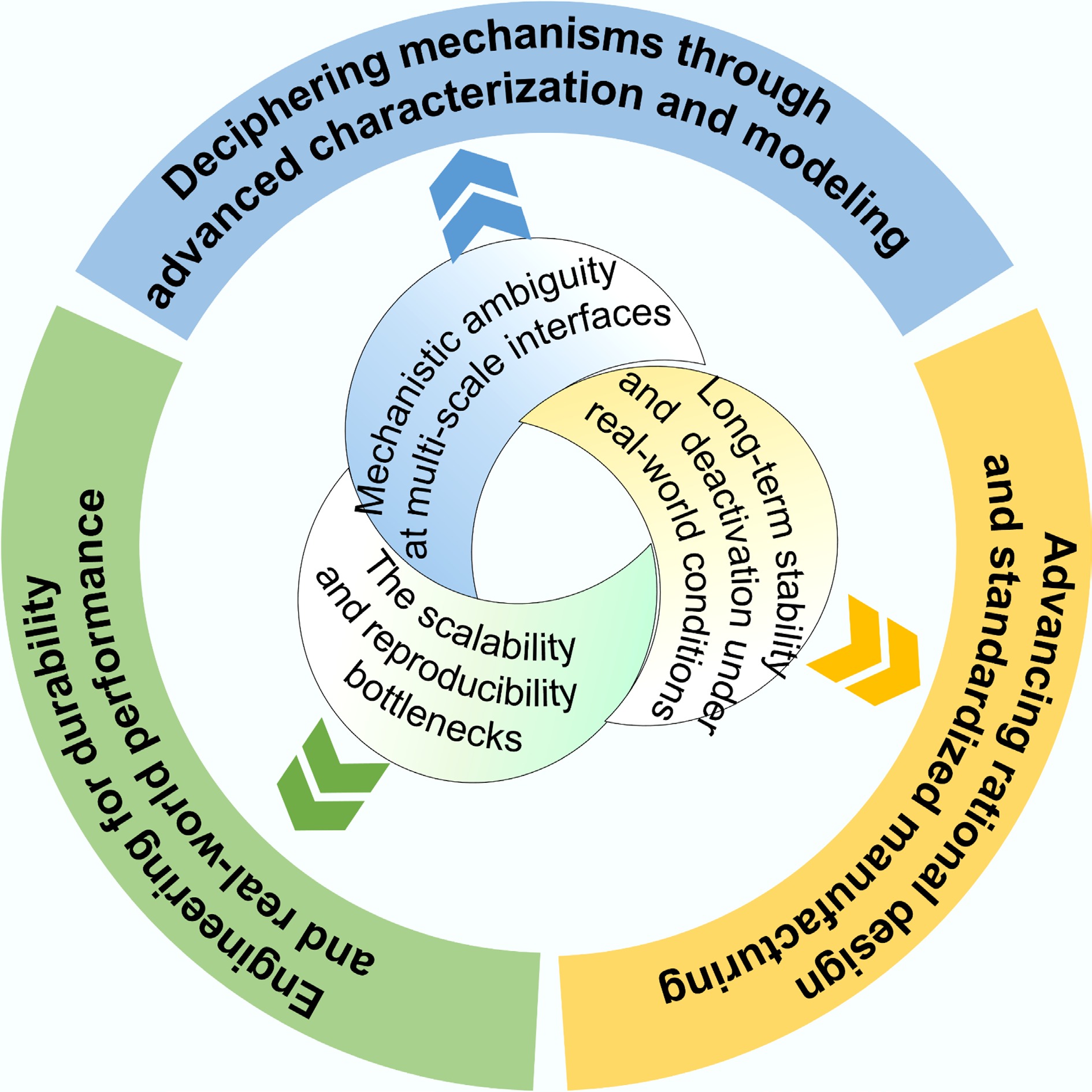

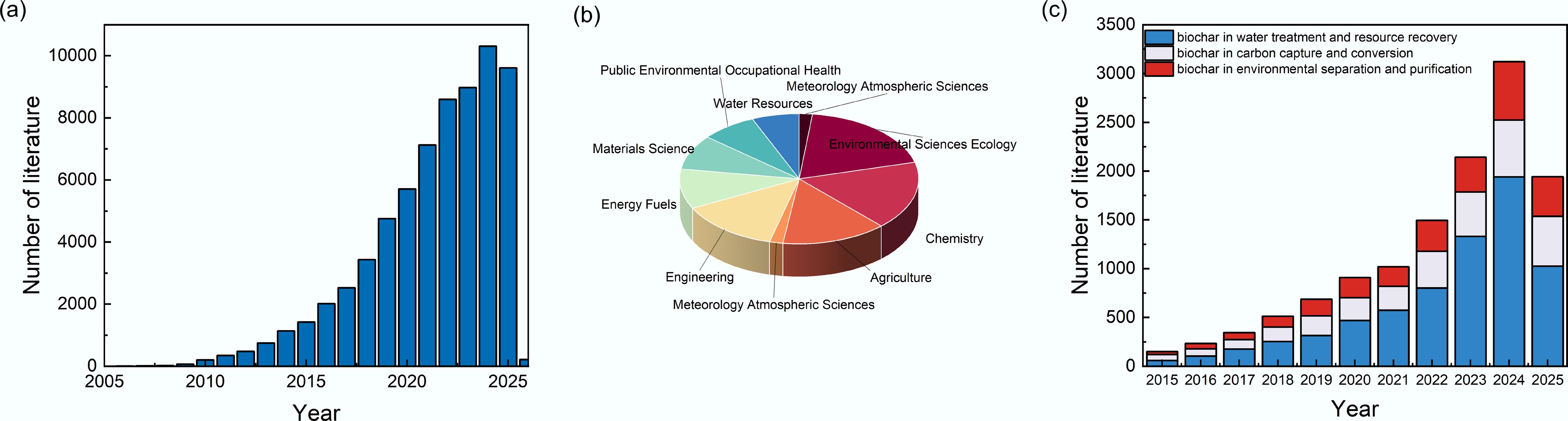

In recent years, the application landscape of biochar has significantly expanded (Fig. 1b) beyond traditional roles such as heavy metal adsorption. A paradigm shift is currently being witnessed in biochar research, driven by the urgent global demand for sustainable technologies to address interconnected crises of climate change, resource depletion, and environmental pollution. Biochar is evolving beyond passive adsorption functions into a versatile platform material for advanced environmental applications, aligning with carbon neutrality and circular economy goals by transforming waste biomass into functional materials that manage water, energy, and carbon cycles simultaneously. This multifunctionality arises from the synergy between its hierarchical porosity, tunable surface chemistry, and intrinsic redox activity[1,5]. These features enable its multifunctional roles in microbial colonization and electron transfer in biological wastewater treatment, CO2 adsorption and activation, and integration into separation/adsorption/membrane composite systems. Recent reviews and empirical studies consistently highlight these three emerging applications as the fastest-growing and most practically promising biochar-enabled directions. According to bibliometric analyses, since 2015, biochar research has witnessed a sharp growth trajectory (Fig. 1a)—not only in soil amendment—but also in fields such as water purification, carbon capture and utilization, and separation membrane technologies (Fig. 1c). Under the global sustainability and circular economy framework, biochar is increasingly recognized as a critical material nexus linking water, energy, and carbon flows. As a sustainable and often carbon-negative material, biochar is now enabling novel applications in biological water purification[8], renewable energy generation, carbon capture and utilization[2,9], as well as environmental separation and purifications[10]. In the biological water treatment and resource recovery, biochar's ability to adsorb nutrients and support microbial growth can significantly enhance the efficiency of nutrient transformation and biogas production processes[11]. In bioelectrochemical systems, biochar facilitates extracellular electron transfer, boosts microbial electrocatalysis, and improves overall energy conversion efficiency[12,13]. For carbon capture and conversion[9,14,15], biochar's high surface area and reactive sites enable efficient CO2 adsorption and catalytic reduction into value-added chemicals and fuels. In environmental separation and purification, biochar's adsorption capacity and intrinsic conductivity enhance the performance of membrane filtration and capacitive deionization (CDI) processes[16]. These three directions represent not only the most dynamic and high-potential arenas in contemporary biochar research and utilization, but also align with global imperatives in sustainability, resource circularity, carbon mitigation, and water security[17,18]. Despite promising progress, its emerging environmental applications remain underexplored, and the fundamental mechanisms linking structure to function, long-term operational stability, and large-scale implementation require further clarification.

Figure 1.

A statistical analysis of the literature on biochar. (a) Number of research studies on biochar. (b) The main research fields of biochar-related studies published in the past decade. (c) Number of studies on the application of biochar in water treatment, carbon capture, and environmental separation from 2015 to 2025 (data obtained from the Web of Science).

Existing reviews have predominantly focused on soil amendment and contaminant immobilization, with limited systematic evaluation of the underlying mechanisms that enable biochar's multifunctional roles in advanced environmental technologies. Several recent reviews have touched upon specific applications, such as its use in anaerobic digestion or as an adsorbent, but a comprehensive synthesis that connects the fundamental properties of biochar to its performance across the full spectrum of emerging applications, from bioelectrochemical systems and CO2 conversion to capacitive deionization, is lacking. This review aims to fill that critical gap. Herein, this review provides a comprehensive synthesis of recent progress in three key areas of biochar's emerging applications: (1) biological water treatment and resource recovery, (2) carbon capture and conversion, and (3) environmental separation and purification, with a consistent emphasis on the mechanistic insights that govern its performance (Fig. 2). By integrating advances across these disciplines, this review seeks to elucidate how biochar is evolving from a traditional soil amendment into a dynamic, multifunctional material platform, thereby charting a course for its future role in sustainable environmental technologies.

-

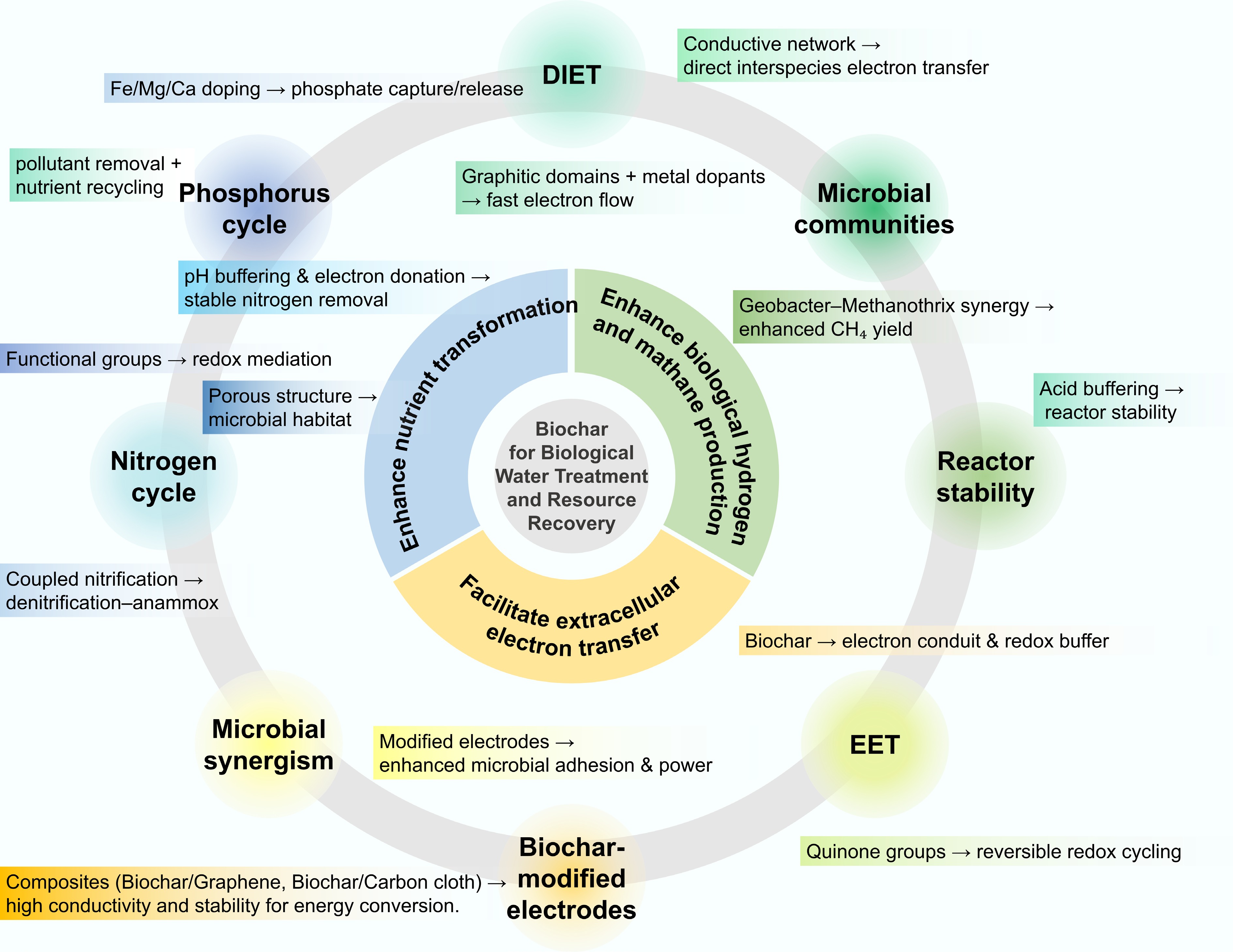

The integration of biochar into biological wastewater treatment upgrades the system from pollutant removal to a multifunctional platform for resource and energy recovery[1,18,19]. Rather than merely acting as a passive adsorbent, biochar functions as a dynamic bio-electrochemical mediator that enhances microbial redox activity, supports microbial colonization, and improves nutrient exchange[13]. These properties enable biochar to facilitate nutrient recovery, bioenergy generation, and microbial electrocatalysis[20,21]. The following sections detail biochar's indispensable roles in nutrient transformation, biofuel production, and bioelectrochemical systems, collectively illustrating its power to mediate a full transition from waste remediation to energy and resource regeneration (Fig. 3).

Enhance nutrient transformation

-

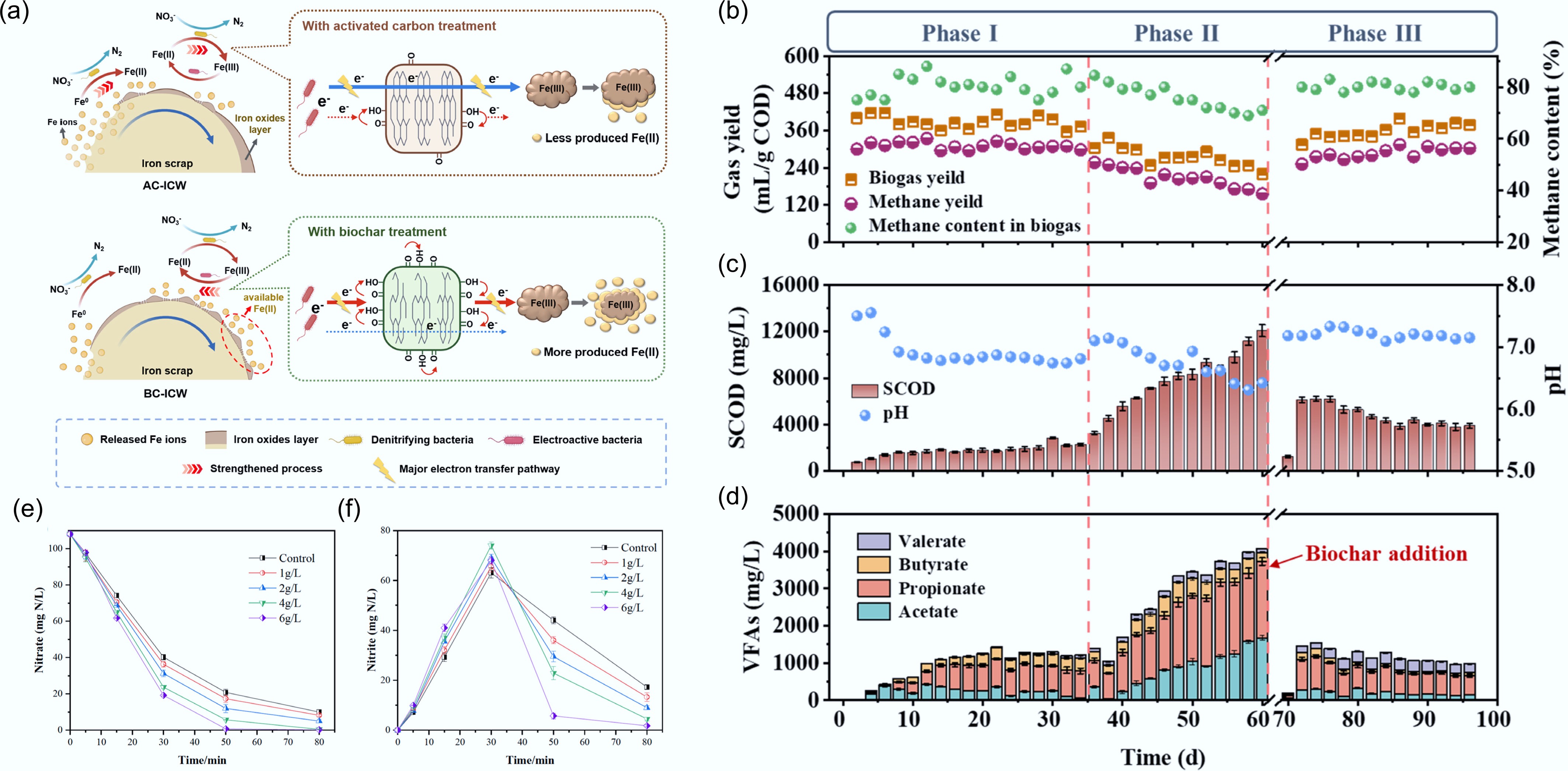

Among the various pathways through which biochar interacts with biological wastewater treatment processes, its ability to regulate nutrient transformation and cycling represents one of the most fundamental and extensively studied mechanisms. In a typical wastewater environment, nitrogen and phosphorus conversions underpin ecosystem stability and determine overall treatment performance. Biochar, with its multifunctional surface chemistry, porous structure, and redox-active moieties, serves as both a microbial carrier and a biogeochemical mediator, facilitating nitrification–denitrification, anammox, and phosphorus recovery processes[22,23]. Acting as a microbial carrier, biochar provides a porous and rough surface architecture that enables stable attachment and colonization of nitrifying, denitrifying, and anammox microorganisms[24]. This three-dimensional habitat not only prevents biomass washout but also promotes syntrophic interactions among functional guilds[13] (Fig. 4a). For instance, Zhou et al.[25] reported that biochar-amended constructed wetland microcosms achieved markedly improved nitrogen removal efficiencies compared to unamended controls. The authors demonstrated that biochar incorporation increased the abundance of key functional genes (e.g., amoA and narG) and facilitated microbial electron transfer through conductive networks, thereby strengthening the coupling between nitrification and denitrification processes. Such results indicate that biochar serves not merely as an inert matrix but as an electro-active interface mediating redox communication between microbial consortia. Within this framework, hierarchical porosity and rough 3D surfaces underpin microbial colonization and mass/electron transport, thereby tightening nitrification–denitrification coupling.

Beyond structural support, biochar actively modulates the local microenvironment, creating favorable pH, redox, and nutrient conditions for biochemical transformations. Its inherent buffering capacity mitigates acidification caused by denitrification, ensuring optimal enzymatic activity and maintaining nitrogen-removal stability[26] (Fig. 4e, f). Moreover, residual organic moieties, quinone-like structures, and redox-active surface groups act as slow-release electron donors, providing continuous reducing equivalents during carbon-limited periods[27,28]. Here, reversible quinone-like moieties and pH buffering—rooted in tunable surface chemistry—sustain electron supply under low C/N and stabilize nitrogen removal. In low-C/N municipal wastewater systems, sludge-derived biochar addition has been shown to enhance total nitrogen removal by maintaining persistent electron flow and accelerating redox cycling through reversible oxidation of surface functional groups[22] (Fig. 4b–d). These features collectively highlight biochar's dual role as both a physical biofilm carrier and a dynamic redox mediator.

Figure 4.

Role of biochar in facilitating nitrification–denitrification. (a) Proposed mechanism of biomass-derived carbon materials facilitating electron transfer in iron-based constructed wetlands[24]. Performance of an anaerobic digestion system using discarded cefradine medicine residues in terms of (b) biogas/biomethane production, (c) COD and pH value, and (d) VFAs concentrations in effluent during operation, showing that biochar enhanced methane production from DCMR under high OLR and achieved a stable AD process[29]. Effects of different biochar dosages on (e) NO3–N concentration and (f) NO2–N accumulation[22].

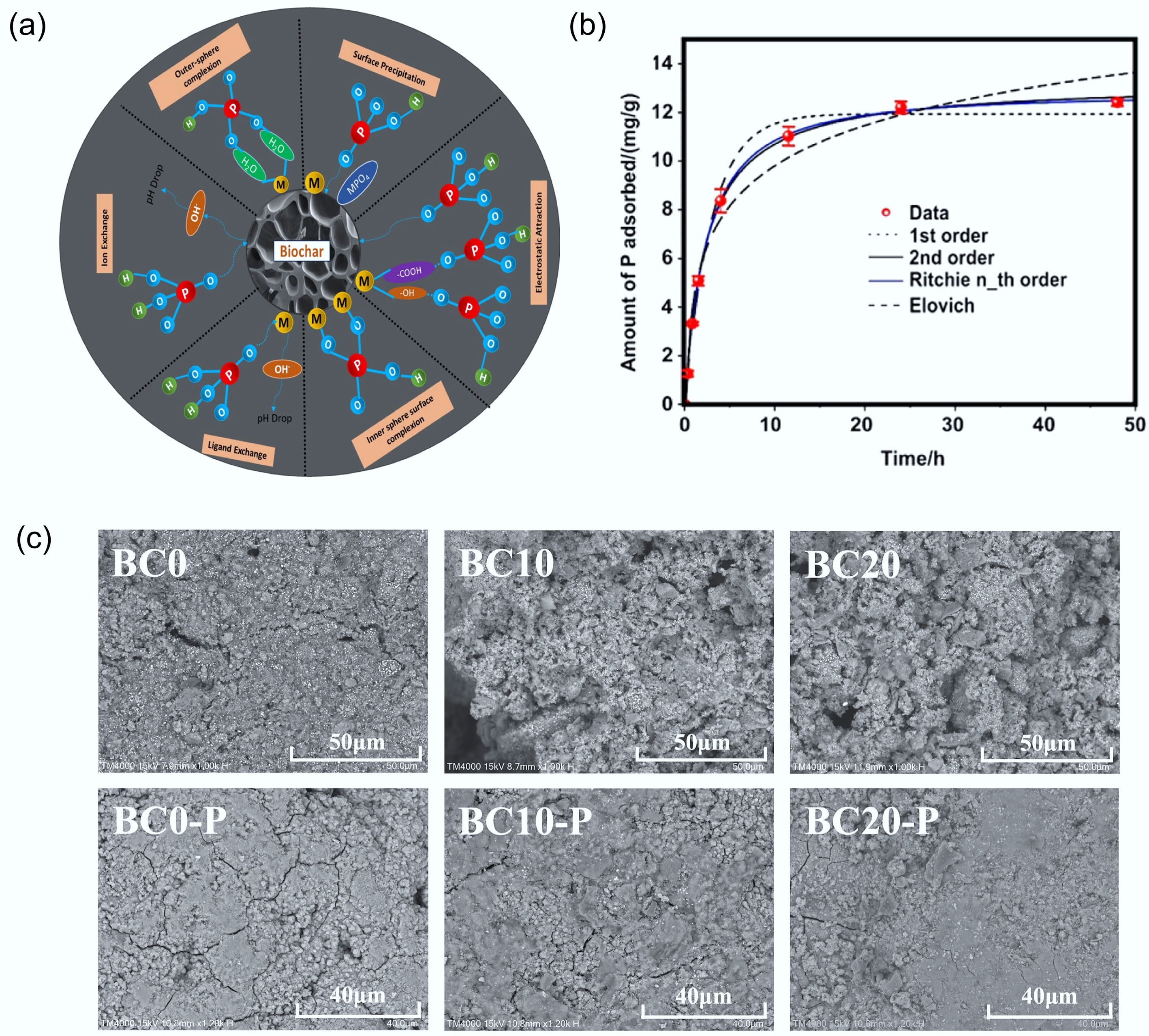

In addition to nitrogen transformation, biochar also significantly contributes to phosphorus cycling and recovery. The surface of biochar contains abundant oxygenated and mineral functional sites (–OH, –COOH, –PO42−), which enable effective phosphate adsorption through electrostatic attraction, ion exchange, and surface complexation[30,31] (Fig. 5a). Modified biochars, particularly those loaded with Mg, Fe, or Ca oxides, have exhibited superior phosphate uptake capacities, combining strong affinity adsorption with controlled desorption that allows for slow-release fertilizer reuse[32,33]. Recent spectroscopic analyses further reveal that these metals promote the formation of stable inner-sphere P–O–metal complexes, preventing leaching losses while enabling bioavailability upon soil application. In another high-impact work, Buss et al.[2] demonstrated that mineral-enriched biochar, produced by doping biomass with potassium-bearing minerals, enhanced plant-available phosphorus release while simultaneously preserving the carbon sequestration capacity of the original biochar. These findings emphasize the potential of engineered biochar as a multifunctional nutrient reservoir capable of coupling pollution mitigation with resource recycling (Fig. 5b).

In summary, the 'structure' elements of engineered biochar—namely hierarchical pore architecture, tunable surface chemistry, and optional mineral/metal phases—jointly define key 'properties' such as electrical conductivity, pH buffering, and interfacial selectivity, which in turn enable targeted 'functions', including enhanced nitrification, denitrification, and anammox, as well as efficient phosphorus capture and controlled release. At scale, however, cyclic adsorption–desorption or redox operation can lead to site attenuation and fouling[34] (Fig. 5c); competing anions and dissolved organics in complex matrices undermine selectivity[35]; and feedstock/pyrolysis heterogeneity complicates standardization[36].

Figure 5.

Role of biochar in phosphorus recovery processes. (a) Mechanism involved in adsorption of P on biochar surface (where P = Phosphorus, O = oxygen, M = metals, H = Hydrogen, C = carbon)[37]. (b) Adsorption kinetic data and modeling for phosphate on the engineered biochar, where symbols are experimental data, and lines are model results[38]. (c) SEM images of BCs before and after P adsorption[39].

Enhance biological hydrogen and methane production

-

Apart from nutrient transformation, biochar has also demonstrated remarkable potential in bioenergy-oriented anaerobic processes, particularly in promoting hydrogen and methane production[40,41]. In conventional anaerobic digestion and dark fermentation systems, imbalanced microbial syntrophy, acid accumulation, and inefficient electron transfer frequently constrain energy yield and process stability. The introduction of biochar offers a multifunctional solution, to name a few, its conductive carbon matrix facilitates direct interspecies electron transfer (DIET), its buffering capacity mitigates acidification, and its porous microenvironment shelters sensitive methanogens and fermentative bacteria[42,43] (Fig. 6a). These properties collectively improve substrate conversion efficiency, accelerate methanogenesis and hydrogenogenesis, and enhance system resilience under organic or hydraulic shock conditions[44].

In a typical anaerobic bioenergy production system, the efficiency of hydrogen and methane generation largely depends on the effectiveness of microbial electron transfer pathways. Traditional syntrophic metabolism relies on diffusible intermediates such as hydrogen or formate to shuttle electrons between fermentative bacteria and methanogens. However, this process is often kinetically constrained and energetically inefficient. In recent years, the concept of DIET has emerged as a more thermodynamically favorable route for syntrophic cooperation (Fig. 6b). Biochar, with its intrinsic conductivity and redox-active surface chemistry, has been widely recognized as a promising material to facilitate DIET and thereby enhance anaerobic digestion and hydrogen fermentation efficiency[45,46] (Fig. 6c, d). A central mechanism underlying biochar-enhanced hydrogen and methane production is DIET[46], which enables syntrophic bacteria and methanogens to exchange electrons directly through conductive materials rather than diffusible intermediates such as H2 or formate. This direct electron sharing accelerates methanogenesis and hydrogen evolution by minimizing energy losses during substrate oxidation. In biochar-amended anaerobic systems, the carbonaceous matrix functions as a solid-state electron conduit, mediating microbial electron exchange[11,47] (Fig. 6e).

Biochar's electrochemical properties, including its degree of graphitization, aromatic carbon structures, and redox-active surface groups (e.g., quinone, phenol, Fe–O clusters), are critical to facilitating the DIET[48]. Graphitized conductive domains and moderate N-doping increase electron mobility and the density of reversible redox sites, thereby shortening extracellular/interspecies electron-transfer pathways and raising CH4/H2 production rates. Highly graphitized biochars, particularly those produced above 700 °C or doped with transition metals, exhibit superior electrical conductivity and electron mobility. For instance, Fe- and Mn-modified biochars not only promote microbial adhesion but also catalyze interfacial redox reactions, accelerating electron transfer between Geobacter and Methanothrix species[49]. Apart from the conductivity, biochar may also modulate the microbial ecology by enriching DIET-relevant taxa and reorganizing syntrophic consortia[50,51]. Beyond serving as an electron conduit, biochar also plays an essential role in regulating the physicochemical microenvironment of anaerobic systems, particularly by mitigating acidification and preserving microbial activity[52,53]. The inherent alkalinity derived from mineral ash and functional groups such as –COO− and –OH could provide pH-buffering capacity, which neutralizes accumulated VFAs and sustains favorable conditions for methanogens. Mineral components like K2CO3 and CaCO3 can further stabilize pH and provide supplementary electron donors.

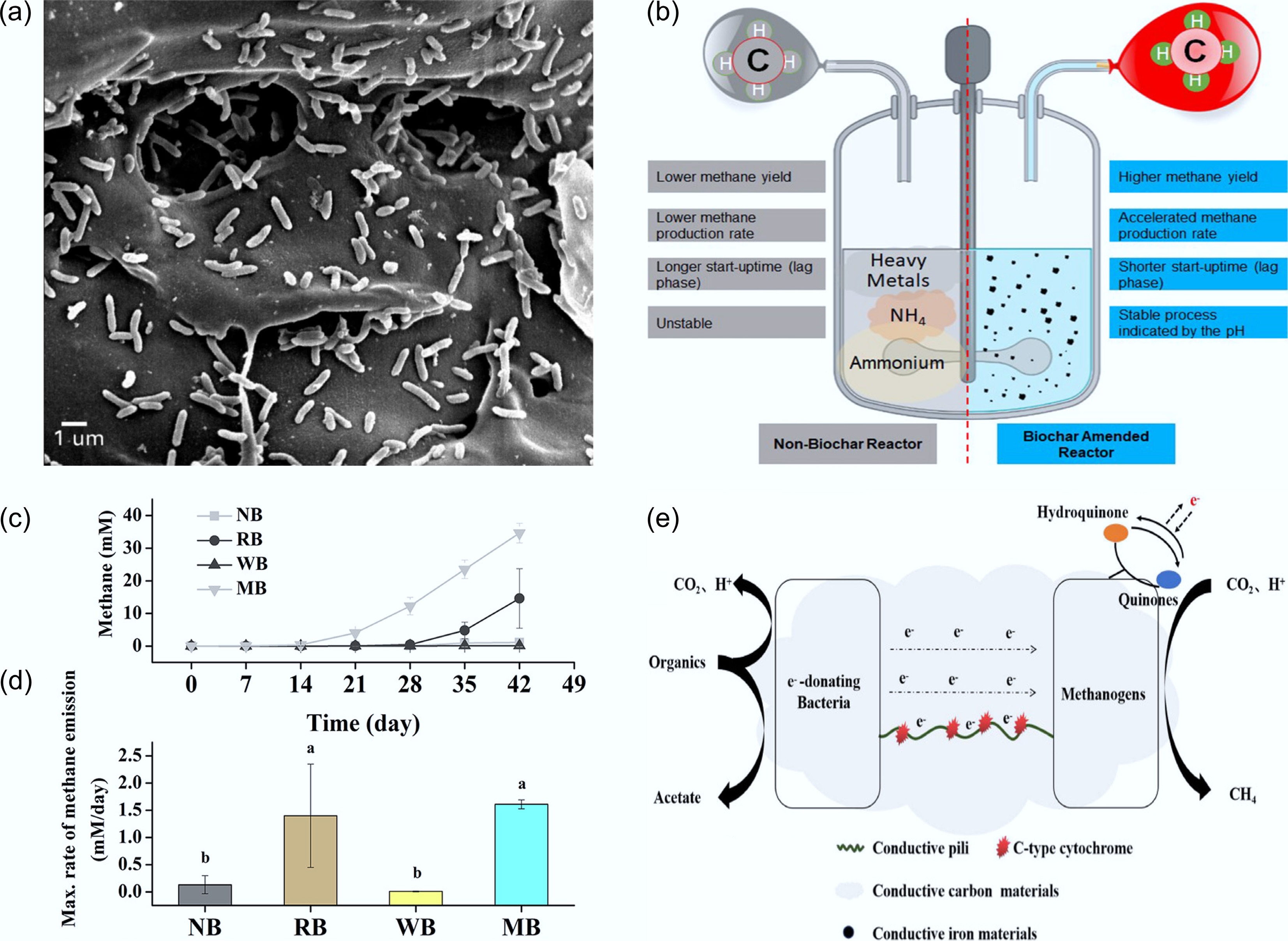

Figure 6.

Biochar-promoted methane production via DIET. (a) Scanning electron micrograph of the biochar tested (BEC) with a syntrophic co-culture of G. metallireducens and G. sulfurreducens[11]. (b) Comparison of anaerobic digester following DIET metabolic pathway against anaerobic reactor following non-DIET pathway[44]. Effects of biochar on methanogenic activities of paddy soil microbial communities, showing (c) time-courses of methane concentrations in the enrichment cultures with ethanol as a substrate in the absence or presence of biochar, and (d) the maximum methanogenic rates estimated from curves in (c). Methane concentrations are expressed as mM by assuming that methane was present in the aqueous phase. Different letters above the bar represent a significant (p < 0.05) difference in the maximum methanogenic rates among different treatments. Data are presented as the means of three independent experiments, and error bars represent standard deviations[50]. (e) Electron transfer mechanisms conductive carbon material mediating DIET[46].

Accordingly, mineral/metal phases and oxygen-containing surface groups provide pH buffering, complexation/selective adsorption, and microenvironmental stability, which translate into greater tolerance to acidification/inhibitors and more stable gas production. Biochar adsorbs or immobilizes inhibitory compounds, including free ammonia (NH3/NH4+), hydrogen sulfide, and long-chain fatty acids, thus alleviating microbial inhibition[54]. Its porous architecture and redox-active sites offer dual detoxification mechanisms through adsorption and redox conversion. Furthermore, the porous microstructure of biochar provides a protective habitat for microbial colonization. Hierarchical pores and connected mesopores enhance mass transport of substrates/intermediates and the robustness of biofilm colonization, thereby maintaining high conversion and gas-production resilience under load fluctuations or short-term shocks. Methanogens and syntrophic acetogens can attach to biochar surfaces, forming biofilms that buffer them from environmental fluctuations[55]. These biofilms promote microbial aggregation and electron sharing, synergistically reinforcing DIET networks[40]. Overall, biochar mitigates acidification and supports microbial resilience by buffering VFAs, adsorbing inhibitors, and providing microhabitats for colonization. In summary, pore architecture, surface chemistry, conductive domains, and mineral/metal phases collectively determine electron/mass transport, buffering, and selective interactions at the material scale, which at the system level manifest as faster kinetics, more resilient biofilms, and higher biological H2/CH4 productivity. These functions stabilize both the physicochemical environment and microbial ecology, complementing the DIET mechanism and collectively improving bioenergy yield and system robustness.

Facilitate microbial extracellular electron transfer (bioelectrochemical systems)

-

Extending beyond anaerobic digestion and bioenergy recovery, biochar's conductive and redox-active nature has also positioned it as a promising material for bioelectrochemical systems (BESs), where microbial extracellular electron transfer (EET) governs overall performance. In microbial fuel cells (MFCs) and microbial electrolysis cells (MECs), inefficient electron exchange between electroactive microorganisms and electrodes often limits energy output and pollutant conversion efficiency. The incorporation of biochar offers a unique strategy to bridge this gap: its graphitic carbon domains and functionalized surface groups facilitate microbial adhesion, accelerate electron transport, and lower interfacial resistance[56,57]. Active sites arising from mineral/metal phases and heteroatom doping govern electron donation/acceptance and the kinetics of peroxide/reactive-oxygen generation, thereby accelerating key bond cleavage and intermediate conversion while suppressing side reactions. By simultaneously acting as a conductive scaffold, electron mediator, and microbial habitat, biochar establishes a micro–electrochemical interface that enables efficient charge flow across biofilms[58]. Moreover, its hierarchical porosity and chemical stability allow integration into large-scale electrode assemblies, expanding the operational potential of BESs toward practical wastewater-to-energy conversion[59] (Fig. 7a).

Conductive scaffold and interface formation

-

At the heart of enhanced EET is the provision of a low-resistance conductive network for microbial electrons to travel from bacterial redox centres (e.g., cytochromes, conductive pili) to the bulk electrode[60]. Biochar prepared under high pyrolysis temperatures, or doped with heteroatoms/metals, often displays enhanced graphitic domains and higher electrical conductivity[61]. Graphitized conductive domains and ordered aromatic structures increase electron mobility and the density of reversible redox sites in both interfacial and bulk phases, which directly results in shorter electron-transfer pathways, faster interfacial reaction rates, and lower energetic barriers. The biochar conductive matrix, which collects electrons from microbial structures and the external circuit, completes the flow of electrons[62]. By enhancing the conductivity of the layer, biochar reduces voltage loss and eases electron transfer, thereby improving overall BES performance. For example, Zhao et al.[63] demonstrated that using biochar electrodes in MFCs significantly reduced charge transfer resistance and boosted power density, attributing the gain to improved electron flow across the microbe–electrode interface. Another review[64] noted that activation, doping, and structural control of biochar strongly affect its electrochemical behaviour and hence EET facilitation. Together, these studies highlight that the proper design of biochar (pyrolysis conditions, pore structure, and doping can markedly influence electrode behaviour (Fig. 7e–h).

Microbial adhesion, biofilm structuring, and pathway facilitation

-

In addition to conductivity, biochar's porous and rough surface topography, plus surface functional groups (–OH, –COOH), enhance microbial colonization and intimate contact with the electrode[60]. Dense biofilm formation shortens electron travel distance, lowers internal resistance, and stabilises the microbe–electrode interface under varying operational conditions. One practical study[65] demonstrated that straw-derived macroporous biochar electrodes facilitated the enrichment of Geobacter and Shewanella species, and increased current production in MFCs by virtue of enhanced microbial–material interaction. In addition, mineral ash and basic surface groups afford pH buffering and ion-exchange capacity, and together with pore-mediated sheltering, the system maintains high removal efficiency and reproducibility under load fluctuations and coexisting interferents. And it can also adsorb inhibitory compounds (e.g., sulfide, ammonia), maintaining favourable environments for microbial EET. Therefore, it acts not only as a physical support but as an active mediator of microbial–electrode electron exchange (Fig. 7b–d).

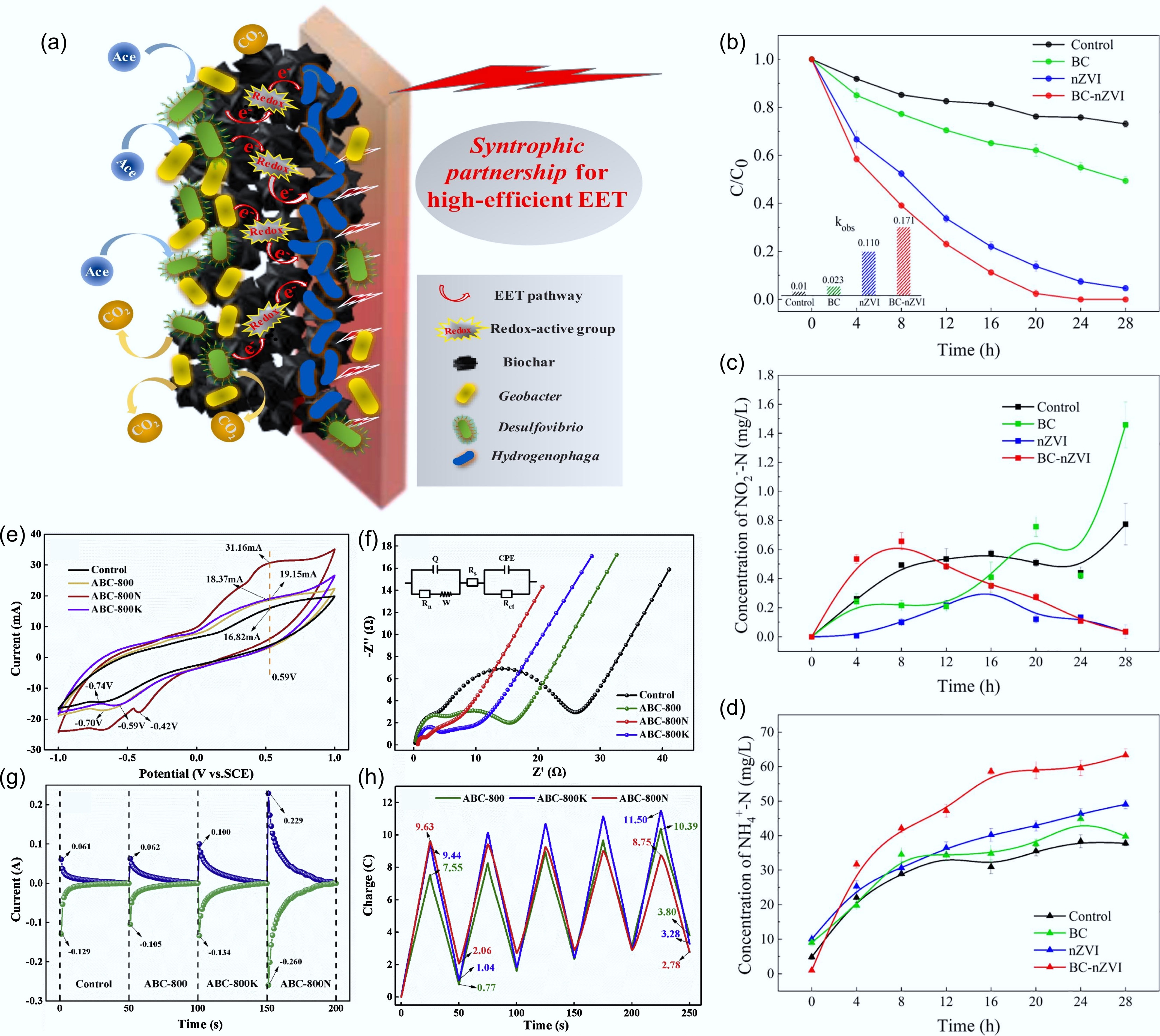

Figure 7.

Biochar facilitates microbial extracellular electron transfer in BES. (a) Proposed mechanism of redox-active biochar boosting EET in anode chamber of BES[66]. Changes in (b) nitrate, (c) nitrite, and (d) ammonia concentration for the control, activated biochar (BC), nano zero-valent iron (nZVI), and biochar-supported nano zero-valent iron (BC-nZVI) groups[67]. (e) CV curves, (f) EIS curves, (g) reductive and oxidative current responses by chronoamperometry, and (h) changes in the amounts of electrons during five successive cycles of charge and discharge of biochar made from Taihu blue algae with four different pretreatments[68].

In summary, pore architecture, surface chemistry, conductive domains, and mineral/metal phases collectively define adsorption/activation capacity, electron/mass transport, and interfacial selectivity at the material level, which at the process level manifest as higher removal efficiency, more controlled intermediate evolution, and more robust operation. Despite these promising mechanistic insights, there remain key challenges: long-term durability, material heterogeneity, and system integration/scale-up with cost and life-cycle considerations.

A coherent chain from structural units → measurable properties → application functions is now evident for biochar in water treatment: hierarchical pores, tunable surface chemistry, graphitized conductive domains, and optional mineral/metal phases jointly define mass-transfer connectivity, electron delivery/interfacial resistance, pH buffering, and selectivity, thereby enabling nutrient transformation and recovery, DIET-assisted bioenergy enhancement, and efficient EET at electroactive interfaces.

For environmental and health impacts, recent studies have begun to systematically evaluate the environmental benefits and health risks of biochar in water treatment. Key concerns for biochar in water treatment include PAHs and metal/inorganic leaching (governed by feedstock and pyrolysis/post-treatment), micro/nanoparticle release and surface/pore aging during long-term use/regeneration, and burdens from cleaning/regeneration effluents and fabrication solvents/consumables. Process-level LCA indicates that, when regeneration and energy use are included, overall performance can match or exceed conventional options but remains highly sensitive to the functional unit and system boundary, requiring harmonized reporting[69]. From an EHS/HH perspective, PAH loads are closely tied to the pyrolysis unit and process control, and biochars derived from sludge or slag warrant particular scrutiny for metal mobility[70,71]. This study recommends, under humid/complex matrices and extended operation, a minimal panel tracking PAHs, metal leachates, particle release, and fate of cleaning/regeneration wastes, aligned with IBI/EBC thresholds and explicit energy/carbon accounting to ensure comparability, transferability, and compliance[72,73].

For engineering deployment, three cross-cutting bottlenecks remain: limited transferability of structure–function mappings across feedstocks and processes; insufficient evidence for long-term stability and regeneration under realistic matrices; and gaps in standardization and scalable integration. For high-temperature graphitized biochars, despite their notable advantages in conductivity and stability, energy consumption and industrial scalability remain significant concerns. The high-temperature pyrolysis required for graphitization is energy-intensive and leads to higher production costs, which can limit large-scale industrial applications. This issue is particularly critical when biochar is produced for large-scale environmental technologies such as water treatment. To address these challenges, low-temperature alternatives such as catalytic graphitization or doping processes can offer viable solutions. These methods, though slightly less effective in terms of conductivity and stability compared to high-temperature graphitization, generally result in lower energy consumption and production costs. Additionally, shorter processing times and more sustainable heat sources may further reduce the energy footprint. Future efforts should prioritize three fronts: validation under real matrices and long-term operation, establishing practical operating and regeneration windows for performance retention, shock resistance, and recoverability; harmonized evaluation, standardizing reporting for removal/conversion, selectivity, energy use, and stability to enable comparability and transferability across feedstocks and processes; and engineering integration and scale-up, co-developing materials with reactor design and process control toward pilot/continuous operation, coupled with TEA/LCA to identify cost–energy–stability constraints and improvement pathways. Scenario-specific choices are needed to resolve the highlighted trade-offs, ensuring benchmarkable and scalable deployment.

-

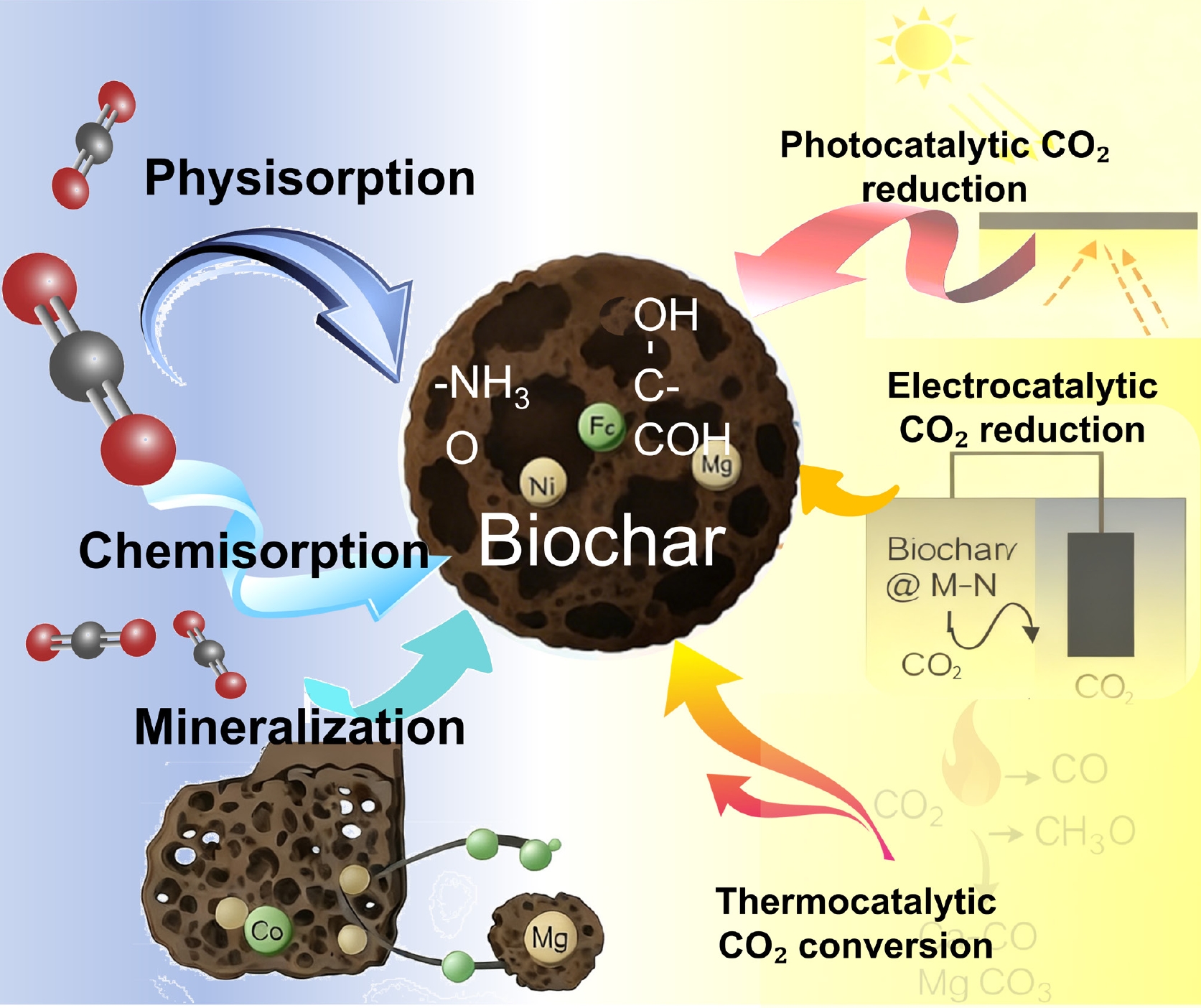

As global decarbonization becomes an urgent scientific and societal goal, biochar has attracted growing interest as a versatile platform for carbon capture, storage, and utilization (CCUS)[14,74,75] due to its high surface area, porous structure, and tunable surface chemistry. It can act as a low-cost CO2 sorbent and as an active catalyst or support for catalytic CO2 conversion into valuable products[15]. Furthermore, when coupled with photocatalytic, electrocatalytic, or thermocatalytic processes, engineered biochar can facilitate the transformation of captured CO2 into fuels and chemicals[76]. These developments position biochar not only as a carbon sink but also as a reactive interface bridging carbon sequestration and carbon utilization. The following sections detail two major research directions—CO2 capture, focusing on structure-activity design, functional modification, and mineralization mechanisms; and CO2 conversion, highlighting photocatalytic, electrocatalytic, and thermocatalytic pathways (Fig. 8).

CO2 capture

-

The continuous increase of atmospheric CO2 and its contribution to global warming have created an urgent demand for low-cost, high-efficiency, and sustainable CO2 sorbents[74]. Biochar, derived from renewable biomass through pyrolysis, has emerged as an attractive candidate due to its carbon-rich matrix, tunable porosity, and versatile surface chemistry (Fig. 9c). Recent studies have shown that biochar exhibits not only strong physical adsorption capacity but also tunable chemisorption reactivity and long-term mineralization potential, forming an integrated platform for both reversible capture and permanent sequestration.

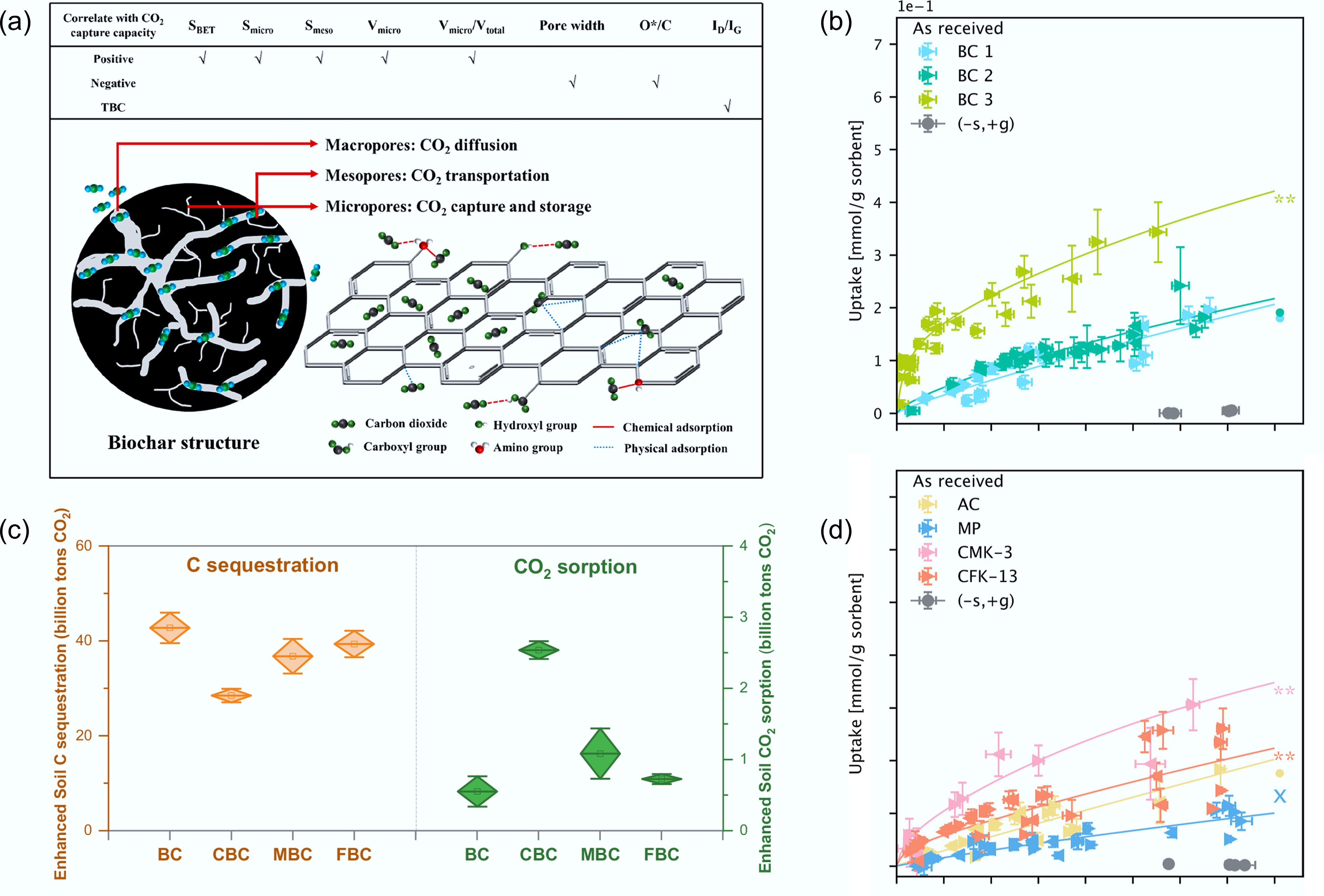

Figure 9.

Performance of biochar in CO2 capture. (a) Potential mechanism of CO2 physisorption by a porous biochar material[74]. (b) Adsorption (forward arrows), and (d) desorption (reverse arrows) of CO2 in balanced air on BC1, BC2, BC3, MP, AC, CFK-13, and CMK-3 as received[75]. (c) Carbon sequestration and enhanced CO2 sorption potential of biochar in cultivated soil across China[14].

Porous structure–controlled physisorption

-

Biochar's hierarchical pore system—composed of interconnected micro-, meso-, and macropores—governs the physisorption process by providing abundant adsorption sites and enhancing gas diffusion (Fig. 9a). Micropores (< 2 nm) dominate low-pressure CO2 adsorption through pore-filling and van der Waals interactions, while mesopores facilitate molecule transport and improve kinetics[14]. Faggiano et al.[77] reported that chemical activation of woodchip-derived biochar increased micropore volume by > 40%, yielding an uptake of 4.5 mmol/g at 25 °C and 1 bar. Such results highlight that optimized pore distribution enhances not only capacity but also the adsorption rate and reversibility. In general, the CO2 adsorption capacity scales with the ratio of micropore volume to total pore volume (V_micro/V_total), which serves as a critical structural descriptor for biochar design. At the microscopic level, the physisorption process follows a potential-field model in which CO2 molecules are confined within narrow pore spaces, experiencing overlapping dispersion potentials from opposite pore walls. This confinement lowers the system energy and stabilizes CO2 molecules, leading to enhanced isosteric heat of adsorption (q_st ≈ 20–40 kJ/mol)—a range intermediate between pure physisorption and chemisorption[74]. Under this mechanism, a narrow-micropore network combined with connected mesopores provides a high accessible surface area and low diffusion resistance, thereby increasing low-pressure adsorption capacity and alleviating mass-transfer limitations during cycling.

Surface functional groups and chemical interactions

-

While porosity dictates storage capacity, surface chemistry determines selectivity and affinity. Functional groups such as hydroxyl (–OH), carboxyl (–COOH), carbonyl (–C=O), and nitrogen-containing species (–NH2, –CN) introduce Lewis basic sites that can form strong dipole–quadrupole interactions with the acidic CO2 molecule[78,79]. Nitrogen functionalities and basic oxygenated groups increase Lewis basicity and polarization capability, enabling reversible coordination/activation of CO2 and thus maintaining high selectivity and working capacity under humidity or mixed-gas conditions. Tian et al.[78] demonstrated that amine-grafted biochar effectively captured CO2 from flue gas via –NH2 + CO2 → –NHCOO− + H+ (carbonate-like carbamate formation) (Atmosphere). This mechanism is particularly relevant under humid conditions, where water molecules act as proton shuttles, facilitating carbamate–bicarbonate conversion. The electronic interaction between surface functionalities and CO2 can also be modulated through heteroatom doping (e.g., N, S, P)[79,80]. XPS and DFT analyses reveal that electron-rich dopants increase local electron density and polarize CO2, lowering adsorption energy barriers and promoting charge transfer to antibonding orbitals (π*). This process resembles initial activation steps in CO2 reduction catalysis, illustrating how capture and conversion are structurally interlinked at the molecular level.

Mineralization-coupled fixation

-

Beyond reversible adsorption, biochar-facilitated mineralization offers a pathway toward long-term sequestration[81]. Basic mineral/metal phases offer sites for chemisorption and cooperative activation, both promoting bicarbonate/carbonate formation and stabilizing CO2/CO intermediates in electrochemical or thermocatalytic routes, thereby achieving higher working capacity or more controllable conversion selectivity at lower energy input. When enriched with Ca2+ or Mg2+, biochar can catalyze the conversion of CO2 into solid carbonates (CaCO3, MgCO3) via surface reactions such as CO2 + Ca(OH)2 → CaCO3 + H2O[82]. Gui et al.[75] reported that Mg-modified biochar in soil environments enhanced net CO2 uptake by 35% through mineral carbonation (Fig. 9b, d). Similarly, Roy et al.[83] highlighted that Ca/Mg-rich biochars serve both as alkaline buffers and nucleation templates for carbonate precipitation, effectively transforming transient adsorption into permanent storage.

In summary, micro/mesoporosity, basic and N-containing surface sites, basic mineral/metal phases, and graphitized conductive domains collectively define physical enrichment and chemical coordination/activation of CO2, electron/mass transfer, and interfacial selectivity at the material level, which at the process level manifest as higher capture capacity, better tolerance to mixed/humid feeds, and more controllable product distributions (Table 1). Key barriers persist under practical conditions: site competition/deactivation by H2O/O2/SOₓ/NOₓ[84], weakened physisorption at elevated temperature, pore collapse or amine leaching during regeneration, and reproducibility/scale-up uncertainties from feedstock/pyrolysis heterogeneity.

Table 1. Performance and optimal conditions of biochar for adsorbing carbon dioxide

Biochar precursor Modifier Pyrolysis temperature Adsorption mechanism Adsorption

performanceRef. Bamboo charcoal ZnCl2, H3PO4, or KOH 823 K Porous structure–controlled physisorption 2.35 mmol/g (298 K) [74] Celery None 923 K Porous structure–controlled physisorption

and chemical adsorption4.2 mmol/g (298 K) [85] Walnut shells FeCl3·6H2O, and Mg(NO3)2·6H2O + TEPA 873 K Porous structure–controlled physisorption

and chemical adsorption3.31 mmol/g (273 K) [78] Wheat straw KOH + Na2CO3, MgCl2·6H2O and NaOH 973 K Porous structure–controlled physisorption

and chemical adsorption6.65 mmol/g (273 K) [86] Albizia procera leaves NaHCO3 973 K Porous structure–controlled physisorption

and chemical adsorption2.54 mmol/g (273 K) [87] Pine saw dust None 823 K Porous structure–controlled physisorption 1.67 mmol/g (298 K) [88] Bagasse and hickory

chipsNH4OH 873 K Porous structure–controlled physisorption

and chemical adsorption1.18 mmol/g (298 K) [89] Cotton stalk NH3·H2O 1,073 K Mainly chemical adsorption 2.25 mmol/g (293 K) [90] Vine shoot KOH 873 K Porous structure–controlled physisorption 2.44 mmol/g (273 K) [91] Coffee ground MgO 873 K Porous structure–controlled physisorption

and chemical adsorption1.57 mmol/g (298 K) [92] Black locust KOH + ammonia solution 923 K Porous structure–controlled physisorption

and chemical adsorption5.05 mmol/g (298 K) [93] Celtuce leaves KOH 873 K Porous structure–controlled physisorption 5.05 mmol/g (273 K) [94] Coconut shells Nitrogen-doped + KOH 773 K Porous structure–controlled physisorption

and chemical adsorption4.8 mmol/g (298 K) [95] Jujun grass KOH 973 K Porous structure–controlled physisorption 5.0 mmol/g (298 K) [96] Pine nut shell KOH 773 k Porous structure–controlled physisorption 7.7 mmol/g (273 K) [97] CO2 conversion

-

Building on the progress in CO2 capture, the next frontier lies in its conversion into value-added fuels and chemicals, coupling climate mitigation with resource valorization. Biochar has recently attracted attention as a catalytic scaffold, electron mediator, and active component, participating in three primary pathways, namely, photocatalytic, electrocatalytic, and thermocatalytic CO2 reduction.

Photocatalysis: biochar as an electron mediator and semiconductor partner

-

In photocatalytic systems, biochar serves either as a visible-light absorber or as a co-catalyst coupled with semiconductors such as TiO2, ZnO, or g-C3N4[98,99]. Its high surface area and hierarchical porosity enable effective CO2 adsorption, while the graphitic or heteroatom-doped domains of biochar act as electron reservoirs, facilitating charge separation and prolonging carrier lifetime[100] (Fig. 10b). Meanwhile, biochar can effectively influence the growth of crystals, shorten the distance for photogenerated charges to migrate from the bulk to the catalyst surface, facilitate the separation of e/h pairs, and thereby enhance the photocatalytic performance (Fig. 10c–e). Lourenço et al.[101] demonstrated that biochar/ZnO composites significantly enhanced the photocatalytic CO2 reduction to CH4 and CO under visible light, owing to synergistic interactions between ZnO conduction bands and biochar's π-conjugated carbon network, which improved electron mobility and CO2 activation. Here, π-conjugated carbon domains and heteroatom sites enhance charge separation and interfacial electron delivery at the material level, which lowers CO2 activation barriers and improves CO/CH4 formation rates and product selectivity under illumination. The photogenerated electrons transfer from the semiconductor conduction band to biochar, where they are stabilized and delivered to adsorbed CO2 molecules, reducing activation barriers for C–O bond cleavage and promoting the formation of CO and CH4. This electron-shuttling behavior illustrates biochar's dual role as both a light absorber and charge-transfer medium (Fig. 10a).

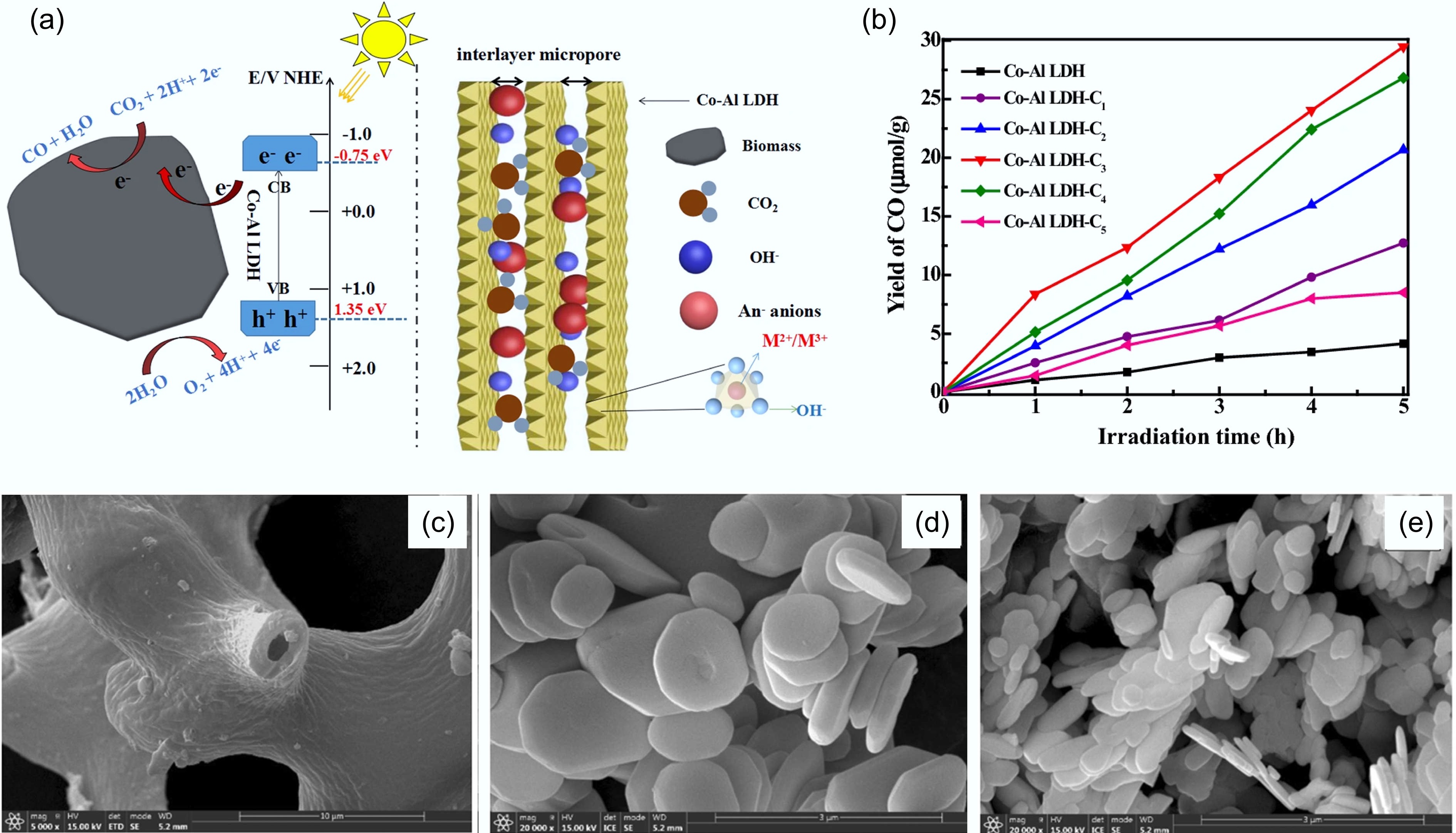

Figure 10.

Performance of biochar in CO2 photocatalysis conversion. (a) Schematic illustration of the mechanism for photocatalytic reduction of CO2 by biochar-modified Co–Al LDH and charge carrier transfer under UV-light irradiation. (b) Yields of a CO for photocatalytic conversion of CO2 over Co–Al LDH, Co–Al LDH–C1, Co–Al LDH–C2, Co–Al LDH–C3, Co–Al LDH–C4, and Co–Al LDH–C5 (referred to biochar derived from withered cherry blossoms) after 5 h under UV-light irradiation[102]. SEM images of (c) rush biochar, (d) BiOCl, and (e) a 0.5% sample. Compared with the reference BiOCl, the 0.5% sample has a thinner lamellar thickness and smaller particle size, which solidly proves that BC affects the growth of BiOCl crystals[103].

Electrocatalysis: biochar as a conductive scaffold for metal–carbon composites

-

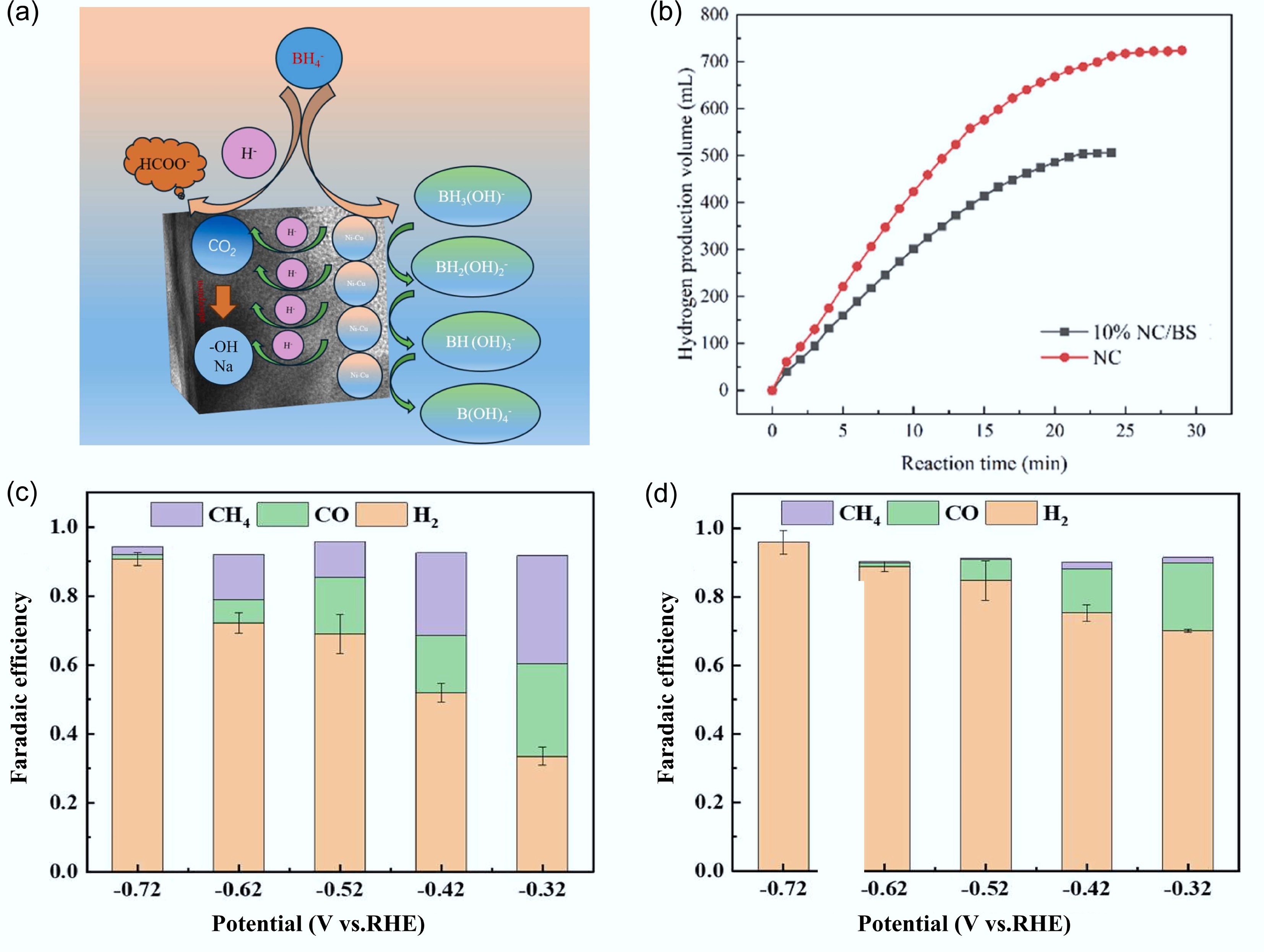

In electrocatalytic CO2 reduction (CO2RR), efficient electron transfer and catalyst stability are crucial. Biochar's intrinsic conductivity and tunable surface functionalities make it ideal for supporting metal or metal-nitrogen-carbon (M–N–C) active centers (Fig. 11a). M–N–C sites/metal–carbon interfaces together with the conductive carbon framework tune the near-Fermi electronic structure and intermediate binding, thereby redistributing selectivity among CO, formate/methanol, and C2+ pathways and increasing the corresponding partial current densities. Fu et al.[15] reported that nitrogen-doped biochar could precisely modulate the electronic structure and adsorption strength of intermediates, achieving high Faradaic efficiencies toward CO and formate. The authors attributed the enhanced selectivity to electron-donating N species that tune the binding of CO2* and HCOO*, thereby stabilizing rate-determining steps. Similarly, biochar–Cu composites have shown improved dispersion of metallic nanoparticles and optimized CO2 activation energy pathways, promoting CO2→CO and formate conversion through biochar-mediated electron conduction (Fig. 11c, d). The electron-transfer pathway typically includes charge conduction through the biochar matrix, adsorption and reduction of CO2 on active metal sites, and desorption of reduced products. Heteroatom doping (e.g., N, S, P) can further modify the d-band center of the metal–support interface, thereby controlling product selectivity toward CH4 or C2 species such as C2H4[104] (Fig. 11b).

Figure 11.

Performance of biochar in CO2 electrocatalysis conversion. (a) Conceptual diagram of CO2 reduction with NaBH4 catalyzed by 10% NC/BS (sodium hydroxide-modified biochar-supported nickel-copper bimetallic alloy). (b) Catalytic performance of 10% NC/BS for CO2 reduction: hydrogen production volume vs reaction time[105]. Products distribution of CO2 RR using (c) Cu/C-BN, and (d) Cu/C materials[106].

Thermocatalysis: biochar-based interfaces for CO2 hydrogenation

-

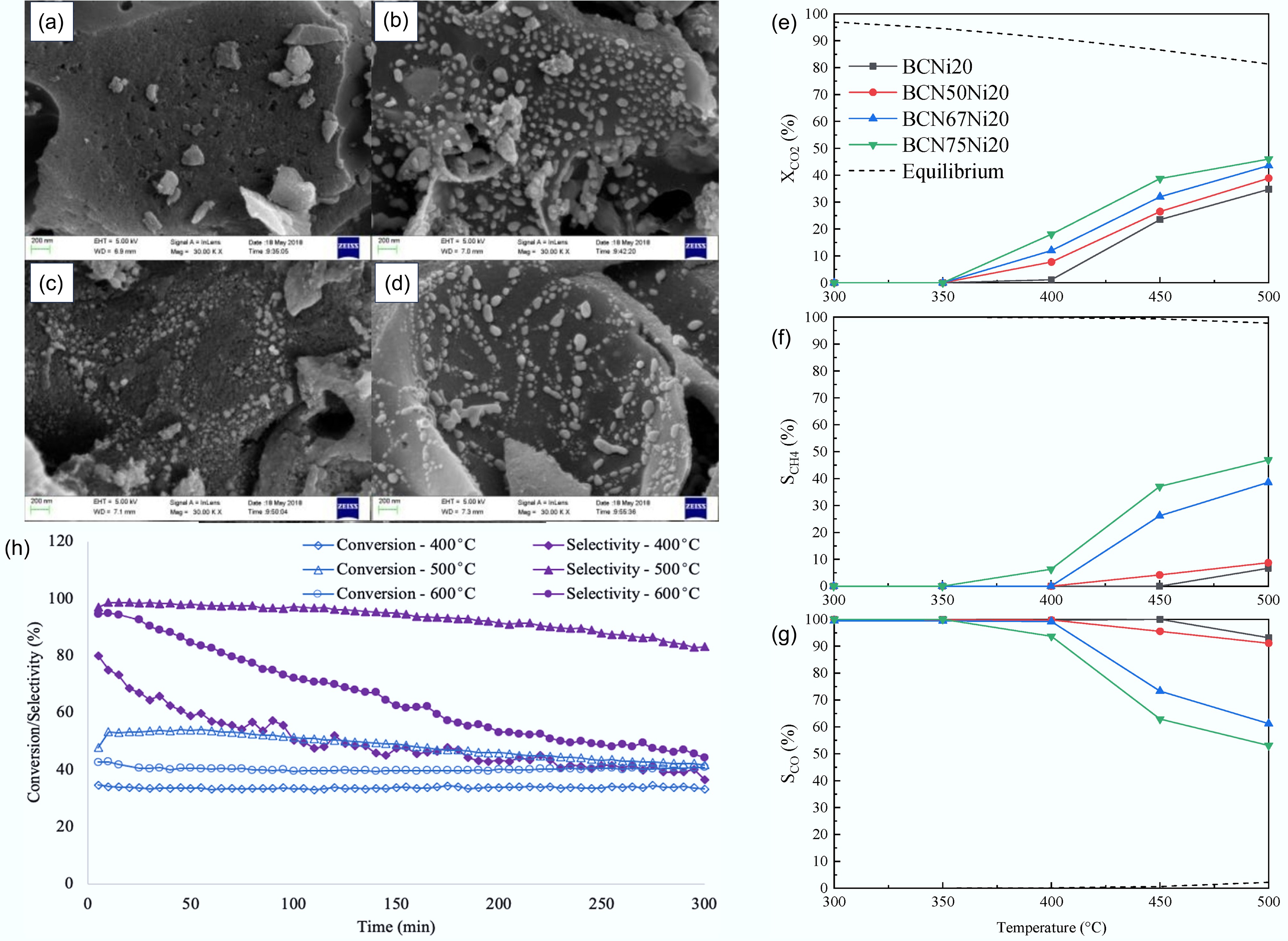

In thermocatalytic systems, biochar provides a robust and high-surface-area carbon matrix that stabilizes dispersed metal nanoparticles (Ni, Ru, Co) and promotes efficient heat and mass transfer. These composites are widely used in CO2 methanation and dry reforming reactions[76,107]. The metal–biochar interface facilitates CO2 activation via CO2 + * → CO* + O*, followed by stepwise hydrogenation to CH4 or methanol. Recent reviews summarize that defect-rich biochars can create oxygen vacancies and enhance hydrogen spillover, lowering reaction temperatures and increasing turnover frequencies[108]. Also, defects and graphitized domains, together with metal–carbon interfaces, promote hydrogen spillover and O–C bond-cleavage steps, enabling higher turnover at lower temperatures with more stable product distributions. These findings highlight that biochar not only acts as a thermal support but also serves as an active participant in hydrogenation chemistry through synergistic metal–carbon interactions (Fig. 12).

Figure 12.

Performance of biochar in CO2 thermocatalysis conversion: SEM micrographs of biochar materials before and after the reaction. (a) Coconut shell carbon CSC, (b) fresh Ni/CSC, (c) fresh Ni-Mg 0.26/CSC, and (d) used Ni/CSC[109]. (e)–(g) for the Ni-based catalysts produced with wheat-straw-derived activated biochar doped with CeO2, the CO2 methanation experiment was conducted under 30 NLgh conditions, and the (e) CO2 conversion rate, (f) methane selectivity, and (g) carbon monoxide selectivity were compared. (h) Biochar-based catalyst performance for CO2 methanation at 400, 500, and 600 °C. Ni loading: 7 wt%; reaction conditions: 37.5 mL/g/min, H2 : CO2 ratio 4:1. Values accurate to ± 6.2% for CO2 conversion and ± 4.8% for CH4 selectivity[76].

In summary, pore architecture, surface chemistry, mineral/metal phases, and graphitized conductive domains jointly define CO2 physical enrichment and chemical activation, electron/mass transport, and intermediate stabilization at the material scale, which at the process scale manifest as higher activity and selectivity, lower energy input, and longer-term stability. Remaining issues include product-distribution broadening from competing multi-electron pathways[110] and durability loss from photo/electro/thermal aging (surface oxidation, graphitic degradation). Tight control over electronic structure and interfacial reactions is needed to consolidate selectivity and longevity.

In CO2 capture and conversion processes, the environmental and health impacts of biochar arise from the superposition of three primary sources. First, the preparation and modification of adsorbents/catalysts (such as amination, metal/mineral phase introduction, and graphitization) are accompanied by solvent use and energy consumption, both of which contribute to environmental and health impacts. These factors need to be considered within a unified lifecycle boundary for synthesis–operation–regeneration assessments. Second, long-term operation and regeneration processes may cause the deactivation of functional groups, leaching of metals or inorganic compounds[111], and the release of nano/microparticles, which are particularly sensitive under humid conditions or in real flue gases containing SOₓ/NOₓ/impurities[112]. Third, the management of by-products and unreacted gases (such as trace CO, hydrocarbons, and small oxygenates) is critical for safety and regulatory compliance[113].

Recent studies have begun to assess the environmental impact of biochar in CO2 capture and conversion. These studies show that, when regeneration and energy consumption are accounted for, climate change and eutrophication metrics can be comparable or better than conventional methods. However, results are highly sensitive to functional units and system boundaries, emphasizing the need for standardized reporting for comparability and transferability[114]. Regarding health and environmental risks, PAH content is closely related to pyrolysis conditions, and biochars derived from certain feedstocks (e.g., sludge, slags) require extra caution regarding metal leaching. In long-term operations and regeneration in complex water systems, it is essential to monitor leaching and changes in morphology and composition before and after operation to support safety assessments and enhance engineering feasibility.

Overall, the integration of structure and interfacial chemistry enables a coherent capture-to-conversion pathway for CO2: pore architecture governs low-pressure capacity and diffusion resistance; surface functionalities with amination/heteroatom doping provide selectivity and initial activation; and mineral/metal phases with conductive/defective domains sustain electron transport and interfacial reactions. This yields a continuum from reversible adsorption to mineralization-based sequestration, and onward to photo-/electro-/thermo-reduction. The principal cross-cutting bottlenecks are selectivity dilution by competing pathways, long-term stability and regeneration decay under realistic conditions, and standardization/scale-up challenges arising from material heterogeneity. For deployment, validation should be conducted under real flue gas/complex matrices and extended operation, with reproducible structure–energetics correlations and process norms to enhance comparability and transferability; in parallel, co-design with reactor architecture, process control, and scale-up, coupled with TEA/LCA, should clarify cost–energy–stability constraints and guide scenario-specific optimization toward scalable implementation.

-

Water purification technologies such as pressure-driven membrane filtration and ion exchange face challenges such as high energy consumption, membrane fouling, and limited selectivity. Benefiting from its porous architecture, tunable surface chemistry, and electrical conductivity, biochar has recently emerged as a multifunctional additive and electrode material capable of improving separation performance while maintaining low cost and environmental compatibility[115].

Recent studies have demonstrated that integrating biochar into separation and purification systems can not only enhance flux recovery and pollutant selectivity but also mitigate secondary pollution by replacing synthetic carbon materials with renewable biomass-derived alternatives. Nonetheless, operational stability, membrane–biochar compatibility, and large-scale manufacturability remain key challenges. This section, therefore, highlights the emerging applications of biochar in membrane separation and capacitive deionization, emphasizing structure–function relationships, performance improvement mechanisms, and future opportunities toward sustainable water purification.

Membrane separation

-

In membrane-based water treatment systems, membrane fouling—caused by accumulation of colloids, organic macromolecules, biofilms, and suspended solids—remains a significant bottleneck, leading to flux decline, elevated trans-membrane pressure (TMP), and reduced operational lifespan. Conventional mitigation strategies (e.g., high back-wash frequency, chemical cleaning) often entail high energy and maintenance costs, prompting the search for functional additives and novel membrane materials. In this regard, biochar has emerged as a promising additive/modifier for composite membranes owing to its renewable biomass origin, tunable porosity, surface functionality, and low cost.

Composite incorporation and foulant mitigation mechanisms

-

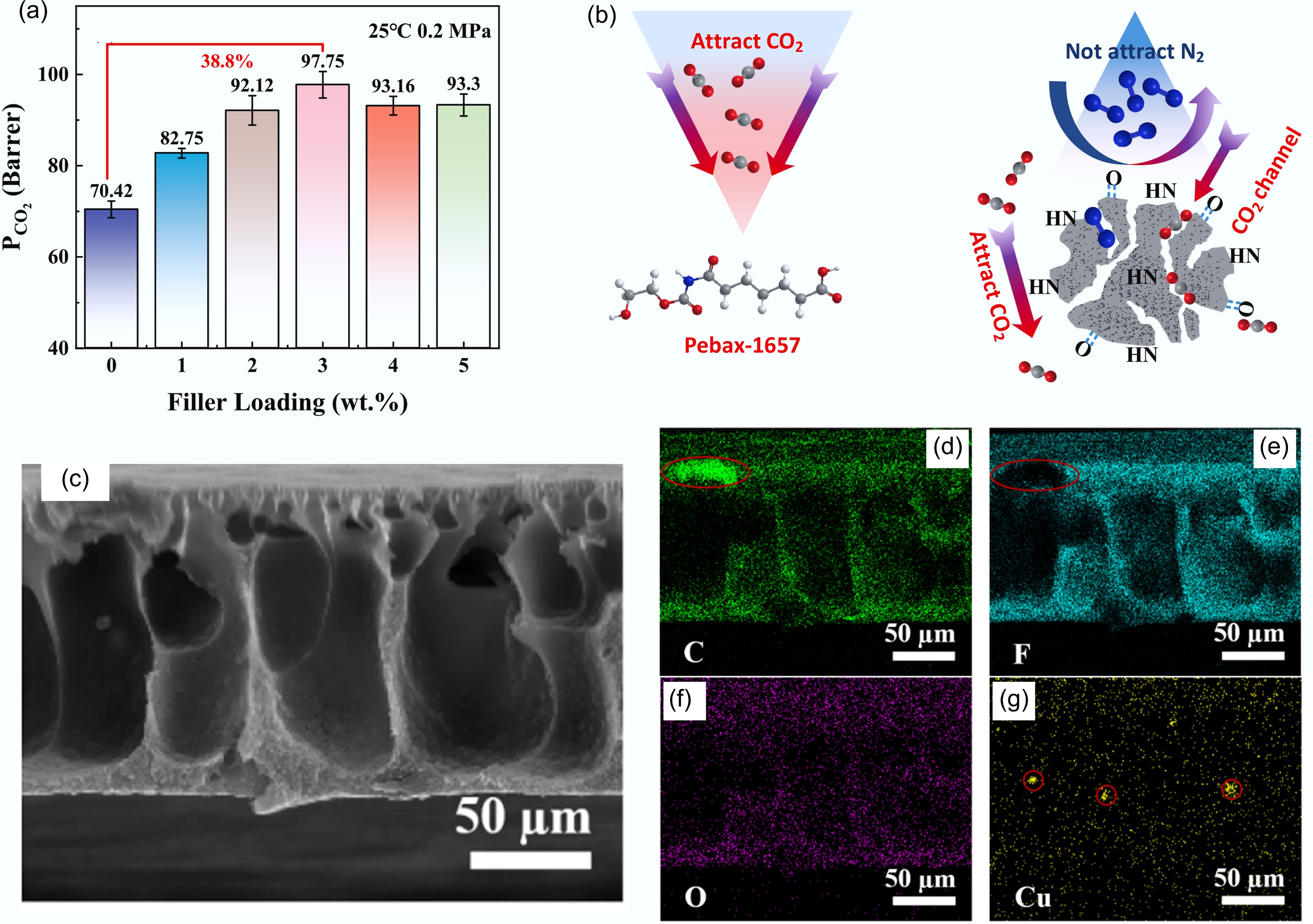

Biochar nanosheets or microparticles can be embedded into polymeric membranes (such as PVDF, PES, PSF) or coated onto membrane surfaces, producing so-called biochar-composite membranes. Their performance improvements arise from improved hydrophilicity, Surface charge modification, roughness alteration and adsorptive pre-capture of foulants (Fig. 13a, b). First of all, hierarchical/connected mesopores provide accessible surface area and low diffusion resistance, and O/N functionalities tailor surface wetting and interfacial charge, which reduces adhesion of hydrophobic foulants and supports higher water flux[116]. For example, the study by Wang et al.[117] found that adding 1 g/L of biochar into an MBR context reduced soluble microbial product (SMP) concentration by ~14% and increased sludge floc size from ~68 to ~113 µm, thereby alleviating fouling. Secondly, biochar particles change membrane surface roughness and zeta potential, which influences foulant deposition[118]. In addition, within the membrane matrix or on the surface, biochar acts as an internal adsorbent for organics or colloids, delaying their deposition on active membrane pores[119]. Jiao et al.[115] reported that biochar addition reduced fouling rate by ~25%–40% and suggested that delayed cake-layer formation was attributable to biochar's internal fouling buffer zone.

Mechanistic pathways at the interface

-

Fouling mitigation in biochar-modified membranes can be understood as the concerted action of three interlinked interfacial processes operating across scales—surface hydration, electrostatic exclusion, and internal scavenging. The synergy of these interfacial processes translates into lower TMP rise, extended cleaning intervals, and sustained effective flux, offering practical design levers such as biochar loading/dispersion, surface-group tuning, and particle-size/porosity matching. Together, they suppress initial adhesion, slow cake-layer growth, and delay irreversible pore blocking. Hydrophilic oxygen-/nitrogen-containing functionalities on biochar (e.g., –OH, –COOH, –NH–) recruit a tightly bound hydration layer that lowers interfacial free energy, screens hydrophobic/van der Waals attractions, and promotes shear-assisted detachment of weakly adhered species during crossflow, thereby reducing primary adsorption and flux decline[120] (Fig. 13c−g). In parallel, deprotonated groups increase the membrane's negative zeta potential, enhancing Donnan-type repulsion of like-charged organic macromolecules and colloids and limiting their approach to pore mouths under neutral-alkaline conditions, which curtails cake accumulation and pore narrowing[116]. Complementing these surface effects, biochar domains embedded within the membrane matrix provide high-surface-area 'pre-trap' sites that preferentially capture residual foulants before they penetrate the selective skin layer, redistributing deposition to noncritical pathways, delaying irreversible blockage, and sustaining higher effective permeability over time[119]. The synergy of these processes underpins the macroscopic improvements in TMP control and cleaning intervals, and it suggests practical design levers—tuning biochar loading and dispersion to maintain a continuous hydration/charge landscape, tailoring surface chemistry to modulate zeta potential without sacrificing permeability, and selecting particle size/porosity that maximizes internal buffering while preserving mechanical integrity.

Performance benefits and design parameters

-

Empirical studies show that membranes with ~0.5 wt%–2 wt% biochar loading can achieve slower flux decline, lower TMP rise, and longer operation before cleaning. For instance, in an MBR, the time to reach TMP = 35 kPa increased from ~44 h (control) to ~94 h with biochar addition[121]. From a materials design perspective, key parameters include: biochar particle size (nano vs micro), dispersion uniformity, surface modification (e.g., oxidation, amination), membrane polymer compatibility, and loading fraction. Higher pyrolysis temperature biochars (700 °C+) often exhibit higher graphitic content, fewer surface oxygen groups, and may need further functionalisation to optimise hydrophilicity. Notably, while enhanced wettability and internal scavenging improve antifouling and flux retention, they may compromise solute rejection/selectivity; thus, loading fraction, functionalization degree, and particle size should be co-optimized to balance permeability/selectivity and fouling resistance.

In summary, pore/morphology, surface chemistry, conductive/graphitized domains, and mineral/metal phases collectively define wetting, interfacial charge, and transport/electron behavior at the material level, which translates into lower TMP rise, slower flux decay, and longer stable operation—a design logic that also informs electrosorption-based CDI. Deployment is constrained by membrane lifespan and mechanical integrity[122], trade-offs between permeability/selectivity and antifouling, scale-up of dispersion and fabrication[123], and solvent/casting burdens in LCA[119]. Coordinated optimization of loading, functionalization, and particle size/porosity—validated under realistic feeds and long-cycle operation—will be key to high-flux, low-maintenance separations.

Figure 13.

The role of biochar in membrane modification. Gas separation performance of mixed matrix membranes fabricated from hydrogen peroxide-modified ball-milled biochar. (a) CO2 permeability. (b) Schematic diagram of MMMs separation mechanism[124]. (c)–(g) EDAX mapping images of PVDF-1 membrane in the cross-section direction, and the complementary regions in the mapping images of C and F elements are associated with the introduced biochar particle[125].

Capacitive deionization (CDI)

-

In the context of increasing scarcity of freshwater and rising importance of brackish water and wastewater reuse, electrosorption-based desalination technologies have emerged as promising alternatives to conventional high-energy processes such as reverse osmosis[126]. Among them, capacitive deionization (CDI), which uses porous carbon electrodes to adsorb ions under a low voltage, is particularly attractive because of its low energy consumption, modularity, and potential for selective ion removal[127]. For CDI to become commercially viable, one of the core challenges lies in the development of electrode materials that combine high specific surface area, fast ion transport, good electrical conductivity, and long-term cycling stability—while remaining cost-effective[128]. In this regard, biochar derived from biomass is gaining increasing attention as an electrode component due to its renewable origin, tunable pore structure, and carbonaceous conductivity.

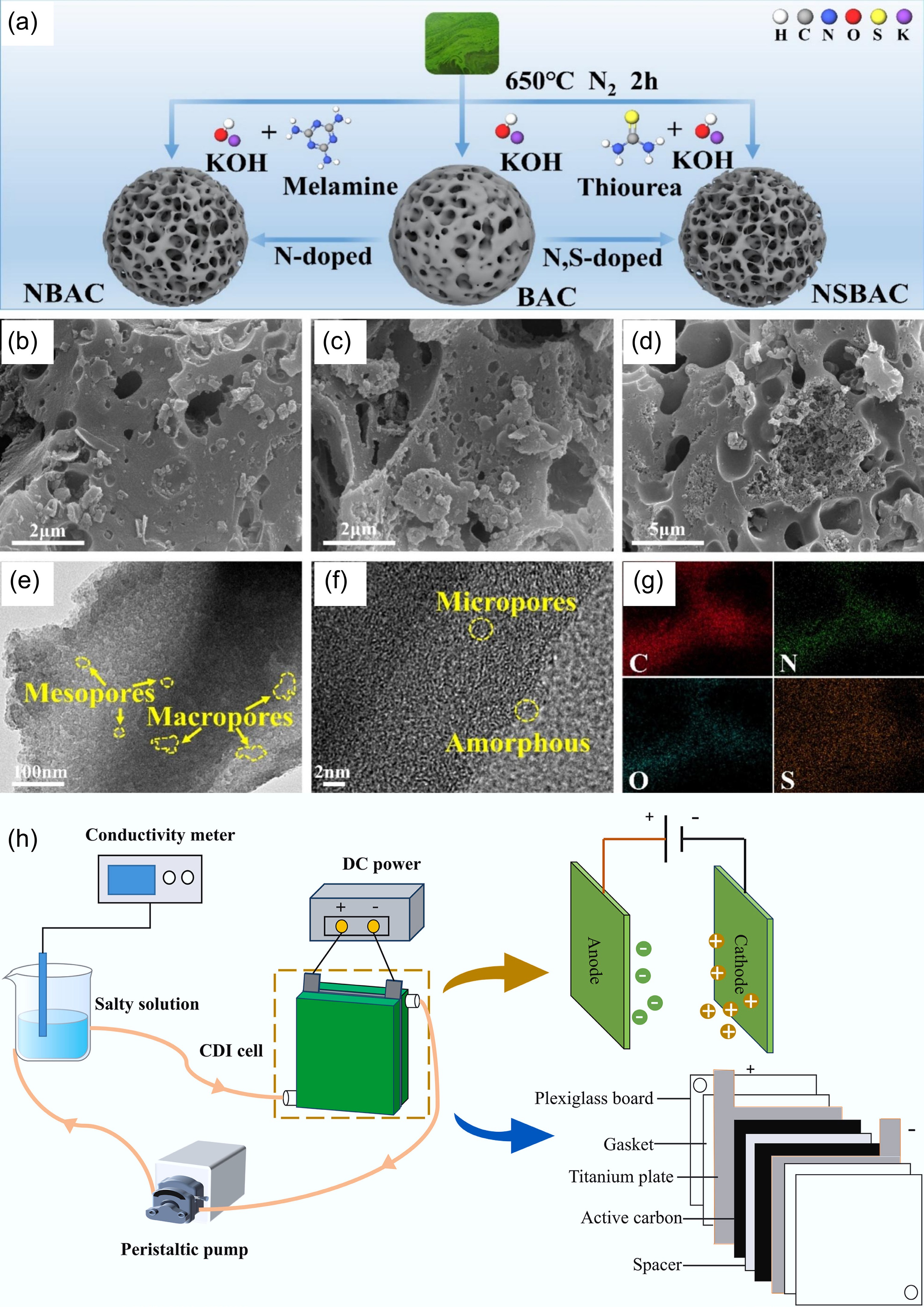

Biochar obtained via pyrolysis and activation can yield hierarchically porous carbon with abundant micropores/mesopores, which are essential for ion electrosorption and double-layer formation[64,129] (Fig. 14a−g). Narrow micropores provide volumetric charge density, while connected mesopores serve as low-resistance highways, jointly boosting low-pressure/low-salinity isotherm capacity and shortening diffusion paths to enhance desalination rate and reversible regeneration. For instance, chitin-derived biochar electrodes achieved an electrosorption capacity of 11.52 mg/g in a CDI setup, with good regeneration and stability. Table 2 presents more application cases. The mechanism of ion storage in these biochar electrodes involves formation of electric double layers (EDLs) at the pore surfaces, adsorption of cations and anions under applied voltage, and release upon voltage reversal, enabling repeated desalination cycles[127]. To further enhance performance (conductivity, capacitance, stability), researchers have explored composites of biochar with graphene, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), metal oxides, or heteroatom doping. For example, recent work shows that biomass-derived carbons with controlled pore structure outperform many commercial activated carbons in CDI setups. Biochar/graphene and biochar/CNT composites improve electron transport pathways, reduce charge-transfer resistance, and enhance cycling stability, which are critical for practical desalination systems[119].

Figure 14.

The role of biochar in capacitive deionization. (a) Preparation process of BAC, NBAC, and nitrogen and sulfur co-doped blue algae-derived activated carbon (NSBAC), SEM images of (b) NBAC, (c) BAC, (d) NSBAC, (e) TEM, and (f) HRTEM images of the NSBAC, (g) EDS mappings of NSBAC[131]. (h) Electrosorption process flow diagram[132].

Table 2. Performance and optimal conditions of biochar for capacitive deionization

Biochar procursor Modifier Pyrolysis temperature Application field Performance Ref Coffee grounds None 1,023 K As electrode materials for MCDI for the selective removal and recovery of lithium ions (Li) from synthetic wastewater The highest lithium recovery of 46.9 mg/g [133] Palm leaflets NaOH 973 K As AC electrodes in CDI system for removing and degrading the salt ions

and methylene blue (MB) organic dye molecules.The maximum salt adsorption capacity achieved 5.38 mg/g for 100 ppm of NaCl solution and 85% of degradation was achieved within

130 min of process duration.[134] Peanut shells KOH 873 K As electrodes in CDI system for seawater desalination The salt adsorption capacity achieved

22.40 mg/g (at 1.2 V and 500 mg/L NaCl), exhibiting an average salt adsorption rate

of 14.93 mg/g/min[135] Coffee grounds KOH 1,023 K As activated-WCG electrodes for capacitive deionization The electrosorption capacity reached 12.50 and 16.50 mg /g in NaCl solution at cell voltages of 1.2 and 1.4 V [136] Coffee grounds KOH 1,023 K As electrode materials for membrane capacitive deionization The specific capacitance reached 108 F/g at a scan rate of 10 mV/s within a potential window of −0.6 to 0.4 V [137] Shrimp shell None 1073 K As membrane capacitive deionization electrodes for electrochemical desalination The desalination capacity reached 10.8 mg/g [138] Cyanobacteria-nitrogen-fixing algae Thiourea and KOH 923 K As capacitive deionization electrodes for the removal of heavy metal ions such as lead (Pb2+) from aqueous solutions The specific capacitance of 270.69 F/g at a current density of 0.5 A/g and in the CDI system Pb2+ adsorption capacity reached 30.42 mg/g (1.2 V, 100 mg/L) [131] Rice straw K2FeO4 1,073 K As electrodes in CDI system for desalination The salt adsorption capacity reached 15.44 mg/g in a 500 mg/L NaCl solution at 1.2 V voltage [139] Longan shells Phosphoric acid + melamine 873 K As electrodes in CDI system for removing the prevalence of norfloxacin (NOR) The maximum adsorption capacity reached

14.9 mg/g[140] Chestnut inner

shellDicyandiamide + KOH + H2SO4 873 K As electrodes in CDI system for removing Zn2+ ions from industrial wastewater The adsorption of Zn2+ reached 706.4 μmol/g at 1.0 V and the selectivity factor reached 14.9 against Na [138] Black locust biochar MgO 673 K As flow electrodes for the removal of NH4+ from water through FCDI The capacitance reached 238 F/g and attained an average removal rate of 17.3 mg/m2/min [141] Ginkgo biloba leaves Baking soda 1,073 K As (M)CDI dechlorination electrode The dechlorination capacity reached 14.35CDI and 20.60MCDI mg/g at an applied voltage of 1.2 V [142] Food waste biogas residue Tobacco stalk + KOH 1,073 K As electrodes in CDI system for

removing Cu2+The removal capacity of ABTC800 electrode can be up to 171.26 mg/g at 3 h in 50 mg/L Cu2+ solution at a voltage of 0.8 V [143] Hermetia illucens pupae casings KOH 773 K As electrodes in CDI system for removing Cd2+ from water The cadmium removal efficiency was 91 % and electro-sorption capacity was 10.9 mg/g [144] Casuarina leaves A novel organic potassium salt PIPES-K2 773 k As electrodes in asymmetric CDI in the treatment of electroplating wastewater The adsorption capacity reached 36.86 mg/g [145] Several interlinked factors govern CDI electrode performance with biochar components. In capacitive deionization, the performance of biochar-based electrodes is governed by a coupled structure–transport–electronic framework (Fig. 14h)—pore size distribution and connectivity govern ion accessibility and diffusion polarization, while conductive domains dictate charge injection and interfacial impedance; together they determine capacity, rate, and coulombic/energy efficiency. First of all, micropores (< 2 nm) provide high volumetric charge density via electric-double-layer filling, while mesopores act as ion highways that shorten diffusion paths and mitigate transport polarization. Consequently, materials with a balanced micropore/mesopore ratio deliver superior desalination rates. Secondly, the high conductivity and low charge transfer impedance brought by graphitized domains or their combination with conductive nanocarbon can reduce ohmic losses, increase the number of energy storage sites that can be effectively driven by electrons, thereby lowering resistance and enhancing the available capacitance[129]. Thirdly, ion selectivity emerges from the interplay of pore size, surface functionality, and electrode design, enabling preferential uptake (e.g., Na+ over K+) and co-ion exclusion that raises charge efficiency and overall desalination performance[128]. Additionally, cycle stability and regeneration efficiency determine engineering availability, as frequent adsorption/desorption cycles, chemical fouling, carbon oxidation, or structural collapse can degrade electrode performance over time. Therefore, it is necessary to maintain pore integrity, conductive pathways, and mechanical robustness over hundreds to thousands of cycles to sustain long-term performance.

Despite promising results, multiple hurdles remain before biochar-based CDI electrodes can be widely adopted. Despite encouraging lab-scale metrics, the pathway to practical deployment of biochar-based CDI is constrained by four coupled challenges that span materials, modules, and systems. First, cycle durability remains insufficiently quantified under realistic brackish or seawater chemistries: hundreds-to-thousands of charge–discharge cycles with variable ionic strength, organic/inorganic foulants, and pH drift can induce capacity fade via carbon oxidation, pore collapse, and binder fatigue; standardized protocols should therefore report ≥ 103-cycle salt-removal retention, energy per mole of salt, and state-of-health trajectories. Second, the cost–performance balance is non-trivial: although raw biochar is inexpensive, activation, heteroatom doping, and composite assembly add processing, solvent, and energy costs; optimization must minimize processing intensity and prioritize scalable, low-toxicity routes and inexpensive current collectors/binders to reduce levelized water cost without sacrificing kinetics or capacity. Third, scaling and integration demand uniform, large-area electrodes compatible with roll-to-roll casting and reproducible dispersion of biochar domains, as well as stack architectures that deliver even current distribution and acceptable pressure drop while managing brine streams and shunt currents in modular flow-by/flow-through cells. Finally, selective removal and energy efficiency require tuning pore size distributions and surface functionalities to favor target ions (e.g., Li+, Na+/K+ discrimination) while limiting co-ion expulsion and parasitic losses; coupling with renewables and hybridizing can raise charge efficiency and cut specific energy for resource-centric separations[130].

In summary, biochar offers a renewable, tunable, and potentially cost-effective platform for next-generation CDI electrodes. By leveraging its porous structure, surface chemistry, and compatibility with conductive carbon modifications, biochar-based materials are poised to enhance desalination efficiency, reduce energy consumption, and support sustainable water purification[146]. Yet practical deployment hinges on long-term durability and regeneration, cost–performance balance, roll-to-roll-compatible electrode fabrication and stack integration, and coupled control of selectivity and energy use. Priorities include quantifying cycle retention and energy under real brackish/contaminated waters and optimizing pore size distribution, surface functionalities, and electrode architecture for manufacturable, scalable desalination and resource recovery.

In separation applications, biochar enhances performance via surface wettability/charge layers that govern interfacial selectivity and antifouling, connected mesopores that reduce mass-transfer resistance and sustain flux, and conductive networks that mitigate ohmic losses and stabilize electrosorption in CDI; optional mineral/metal phases further tune local pH and co-ion exclusion, enabling a coherent pathway across adsorption, membrane rejection, and capacitive deionization.

In membrane and CDI/MCDI separations, lifecycle burdens and EHS risks are dominated by solvent and energy use during membrane/electrode fabrication, cleaning/regeneration in long-term operation, and management of by-products/concentrates. Recent studies identify solvent choice and fabrication energy as high-leverage nodes in membrane LCAs[119]: conventional NMP/DMF entails notable health risks and tightening regulation, whereas greener solvents can reduce multiple impact categories without sacrificing performance. This motivates integrated accounting of synthesis–operation–regeneration under a unified system boundary with an explicit functional unit. For CDI/MCDI, operational energy and materials/chemical use typically dominate LCA outcomes, while solution switching/mixing conditions can materially shift energy efficiency and by-products; thus, cleaning/regeneration frequency, reagent use, and waste handling should be co-reported. In addition, composite carbon and metal-containing electrodes may undergo nano/microparticle release or inorganic leaching over extended cycles, warranting concurrent leachate/particle monitoring and pre-/post-characterization. To enable engineering benchmarking, this study recommends harmonized LCA reporting (unified boundary and functional unit), and, under complex feeds and long durations, co-reporting solvent usage and greener alternatives, cleaning/regeneration frequency, waste fate, particle/metal release metrics, and pre/post electrode/membrane characterization to strengthen comparability, transferability, and compliance.

The main cross-cutting bottlenecks are the persistent trade-offs between antifouling and flux and between selectivity and energy use, the need for stronger evidence of long-term stability and reproducible cleaning/regeneration under real waters, and standardization/scale-up challenges arising from material and module variability. For deployment, validation under complex matrices and continuous operation should define practical operating and regeneration windows; co-design with module architecture and process control, coupled with TEA/LCA, can clarify cost–energy–stability constraints and guide scenario-specific optimization toward scalable implementation.

-

Biochar has evolved from a conventional soil additive into a multifunctional, tunable material platform enabling next-generation environmental technologies. This review has highlighted its diverse applications across biological water treatment, carbon capture and conversion, and environmental separation, all underpinned by its hierarchical porosity, surface chemistry, and redox-active functionalities. Here, biochar can also be conceptualized as a four-knob, tunable materials system—micro/mesopore network, O/N/S surface functionalities, graphitized conductive domains, and mineral/metal phases—where each knob governs a set of key properties that collectively determine performance. Micro/mesoporosity controls low-pressure site density, diffusion resistance, and wetting/biofilm accommodation; O/N/S groups set Lewis basicity, polarization, interfacial affinity/selectivity, and pH buffering; graphitized domains regulate electron mobility and charge separation, shaping onset potentials and polarization losses; mineral/metal phases (e.g., M–Nₓ/M–Oₓ, basic ash) provide local alkalinity and chemisorption/activation sites, stabilizing intermediates and suppressing side reactions. Via the reflection of 'Mapping structure → properties → function', these property families translate into application-level KPIs: biological water treatment, carbon capture & conversion, and environmental separation/CDI.

Moving forward, realizing biochar's full potential requires harmonizing validation under realistic, long-term conditions to define transferable operating and regeneration windows. And secondly, materials–module–process co-design coupled with TEA/LCA to establish criteria and boundaries for standardization and scale-up. Pursuing these lines will translate laboratory gains into benchmarkable, scalable deployments. Through such efforts, biochar can mature into a scalable, circular, and carbon-negative material for sustainable environmental solutions (Fig. 15).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Tingyu Zhang: draft manuscript preparation, material preparation, data collection and analysis; Wujun Liu: study conception and design, manuscript revision, editing, supervision, and conceptual guidance. Both authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets used or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 22122608 and 22476192).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Biochar connects water, carbon, and energy systems through multifunctional environmental roles.

Engineered biochars enable cleaner water, lower carbon emissions, and sustainable resource recovery.

Emerging designs turn biochar into a key material for circular and carbon-neutral technologies.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang TY, Liu WJ. 2026. Beyond soil remediation and contaminant treatments: emerging environmental applications of biochar. Biochar X 2: e002 doi: 10.48130/bchax-0025-0015

Beyond soil remediation and contaminant treatments: emerging environmental applications of biochar

- Received: 06 November 2025

- Revised: 03 December 2025

- Accepted: 18 December 2025

- Published online: 20 January 2026

Abstract: In the face of escalating global challenges, including climate change, water scarcity, and the urgent need for a circular economy, biochar has rapidly evolved from a traditional soil conditioner into an advanced, multifunctional platform material. This transition positions biochar at the nexus of integrated water, carbon, and energy management systems. Owing to its hierarchical porosity, tunable surface chemistry, and intrinsic redox activity, biochar now enables simultaneous pollution control, resource recovery, and renewable energy conversion within a unified and sustainable framework. While its roles in soil remediation are well-documented, a systematic review of its emerging applications beyond these traditional uses is critically needed. This review addresses that gap by synthesizing recent advances in biochar-enabled technologies across three key areas: (1) biological water treatment and resource recovery, where it enhances microbial electron transfer and nutrient cycling; (2) carbon capture and conversion, utilizing functionalized biochars for CO2 adsorption and catalytic reduction to fuels; and (3) environmental separation, through its integration into advanced membranes and capacitive deionization electrodes. Despite promising progress, challenges in linking material structure to function, ensuring long-term stability, and achieving scalable implementation persist. This review not only catalogs these emerging applications but also outlines a forward-looking research agenda, emphasizing the need for rationally engineered biochars with quantifiable structure-activity relationships, coupled with rigorous life-cycle and techno-economic assessments. By providing this comprehensive overview, this work underscores biochar's transformative potential as a versatile and sustainable material to advance carbon-neutral technologies and circular resource flows.

-

Key words:

- Biochar /

- Nutrient recycling /

- Electron transfer /

- Carbon capture and conversion /

- Separation