-

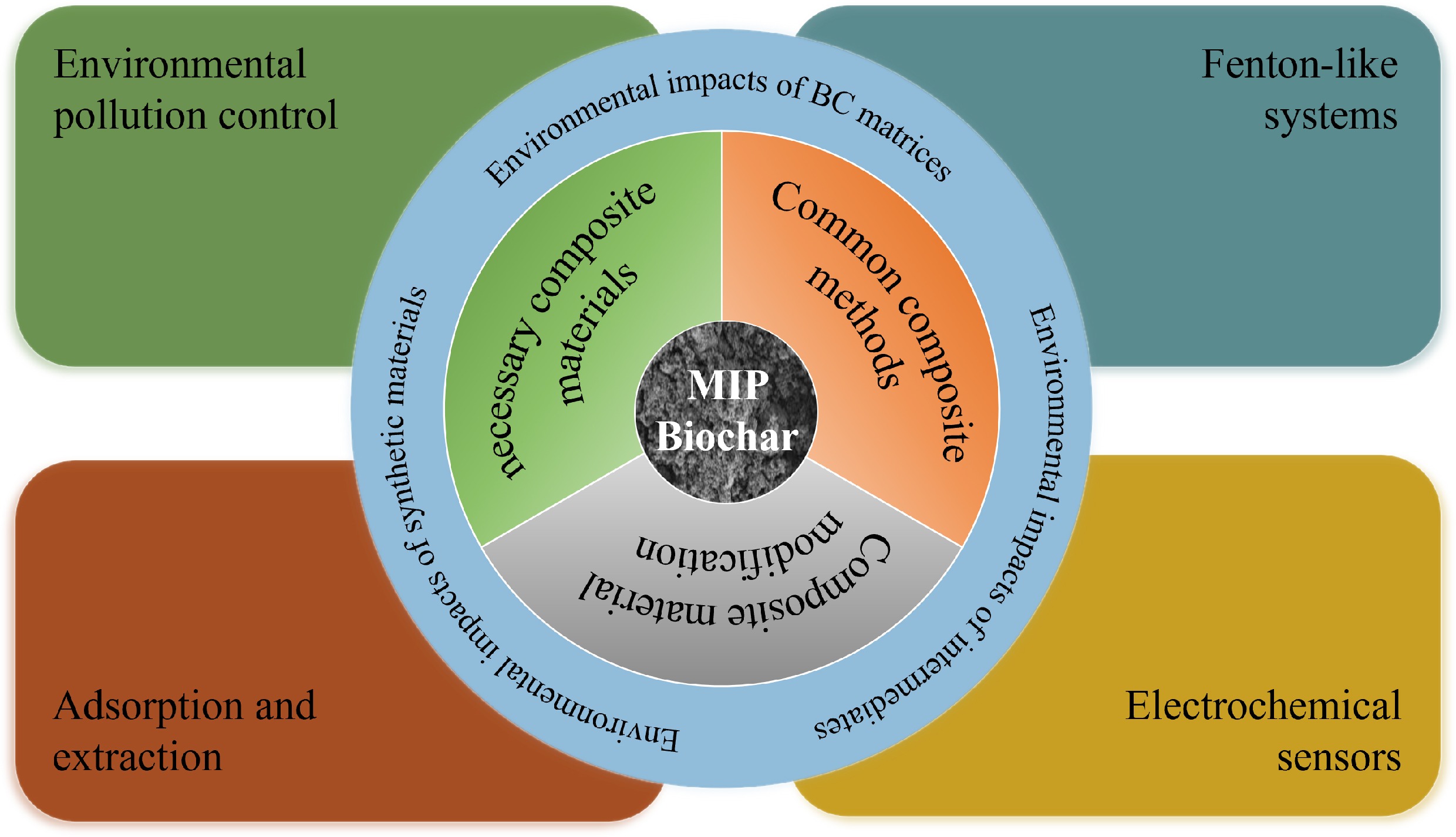

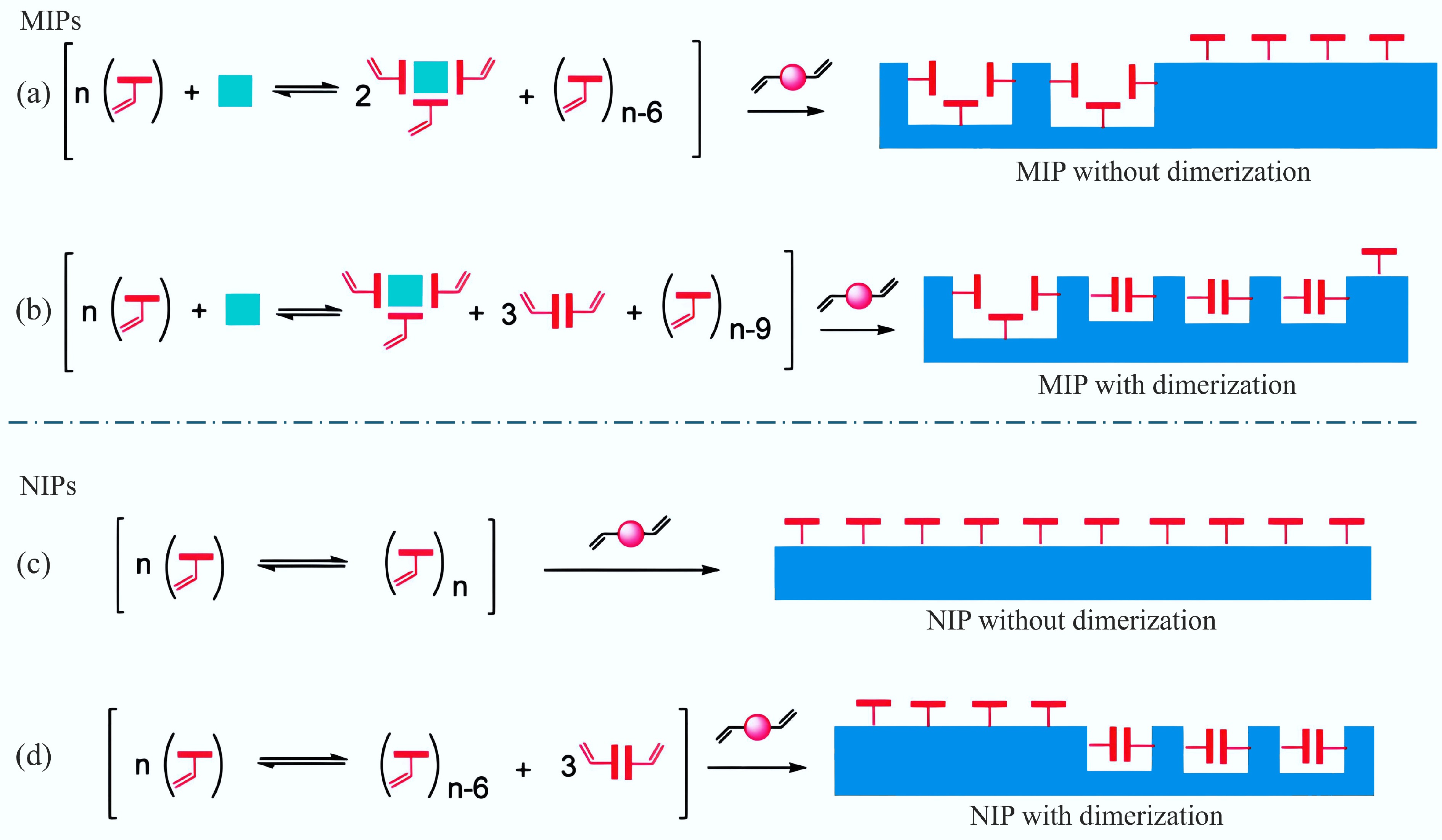

Molecular Imprinting Technology (MIT) is a material synthesis approach based on the principle of molecular recognition. It involves embedding specific template molecules into polymers, leading to the formation of Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) that feature distinct recognition sites. These MIPs, with their tailored recognition sites, facilitate selective, and targeted adsorption[1−3]. The principle of molecular imprinting is illustrated in Fig. 1[4]. Molecularly imprinted materials have gained significant attention in the fields of separation, detection, and catalysis due to their exceptional selectivity and specificity. Biochar (BC) has recently received more attention as a promising multifunctional porous carbon material[5]. The abundant raw materials, large specific surface area, excellent stability, rich functional groups, porous structure, and low cost of BC have led to its wide-ranging potential applications across various fields[6,7]. BC has gradually emerged as a key carrier for MIT due to its promising modification potential and high adsorption performance. The integration of MIT with BC materials not only enhances the selectivity and recognition efficiency of target molecules but also enables the effective use of biomass waste as a valuable resource, aligning with the principles of sustainable development.

Figure 1.

Preparation of MIPs[4].

Recent academic studies have extensively explored the application of BC materials in MIT, with particular attention to exploring the mechanism of synergistic effects. These studies have not only enriched the theoretical foundation in the field of molecular imprinting but also provided new ideas for practical applications. To produce Molecularly Imprinted BC Polymers (MIBs) with enhanced performance, it is crucial to select suitable template molecules, functional monomers, cross-linking agents, and polymerization initiators, while also determining their optimal addition ratios[8]. To date, numerous studies have focused on enhancing the synthesis of MIPs[9,10]. The modification of MIBs can be divided into two types: the surface modification and functionalization to tailor its response properties of BC in specific environments or systems, which effectively enhances the performance of molecularly imprinted materials. The tunability of BC's functional groups, along with its chemical stability and electrical conductivity, makes it a highly suitable platform for supporting a variety of catalytic nanoparticles[11,12]. The excellent electronic conductivity of BC promotes efficient electron transfer, helping to mitigate the complexation of e/h+ pairs in semiconductor photocatalysts[13]. Moreover, the integration of BC enhances the photocatalyst's visible light sensitivity and adsorption capacity, and reduces the tendency for agglomeration[14]. Furthermore, enhancing the surface of the prepared MIBs, such as modifying pre-prepared MIPs with hydrophilic components, can significantly improve their hydrophilicity. Typical modification methods involve the use of hydrophilic polymer brushes, hydrophilic layers, and hydrophilic functional groups[15]. These modifications have broadened the scope of MIBs, allowing for their use in a wide range of fields. In particular, in the field of facilitating pollutant removal, the magnetic modified BC substrate is inherently superparamagnetic, making it an effective adsorbent material; when its selectivity is improved by molecular imprinting techniques, a highly selective magnetic BC is realized that can be easily regenerated and recycled[16]. Additionally, MIBs have more applications in solid-phase extraction[17], Fenton-like systems[18], and sensor detection[19−21].

Few reviews have provided a systematic summary of the research progress on MIBs, covering their preparation, modification, and applications. The main aim of this study is to provide a detailed review of the diverse applications of MIBs in different fields. This includes a thorough discussion of the conventional preparation methods of MIBs, highlighting the key techniques and innovations in the field. The review is supplemented with a discussion on the selection of preparative materials, including functional monomers, cross-linking agents, initiators, and green synthesizers, as well as the multiple modifications and synergistic effects of the composites. Subsequently, the paper provides an overview of the applications of MIBs in the management of pollutants, solid phase extraction, Fenton-like systems, electrosensors, and multi-disciplinary detection. In addition, as a multifunctional and multidisciplinary application-oriented material, eco-friendliness is a crucial property to assess. Thus, the environmental risks associated with composite applications are also discussed. Finally, the potential future developments and research avenues for MIBs are discussed.

-

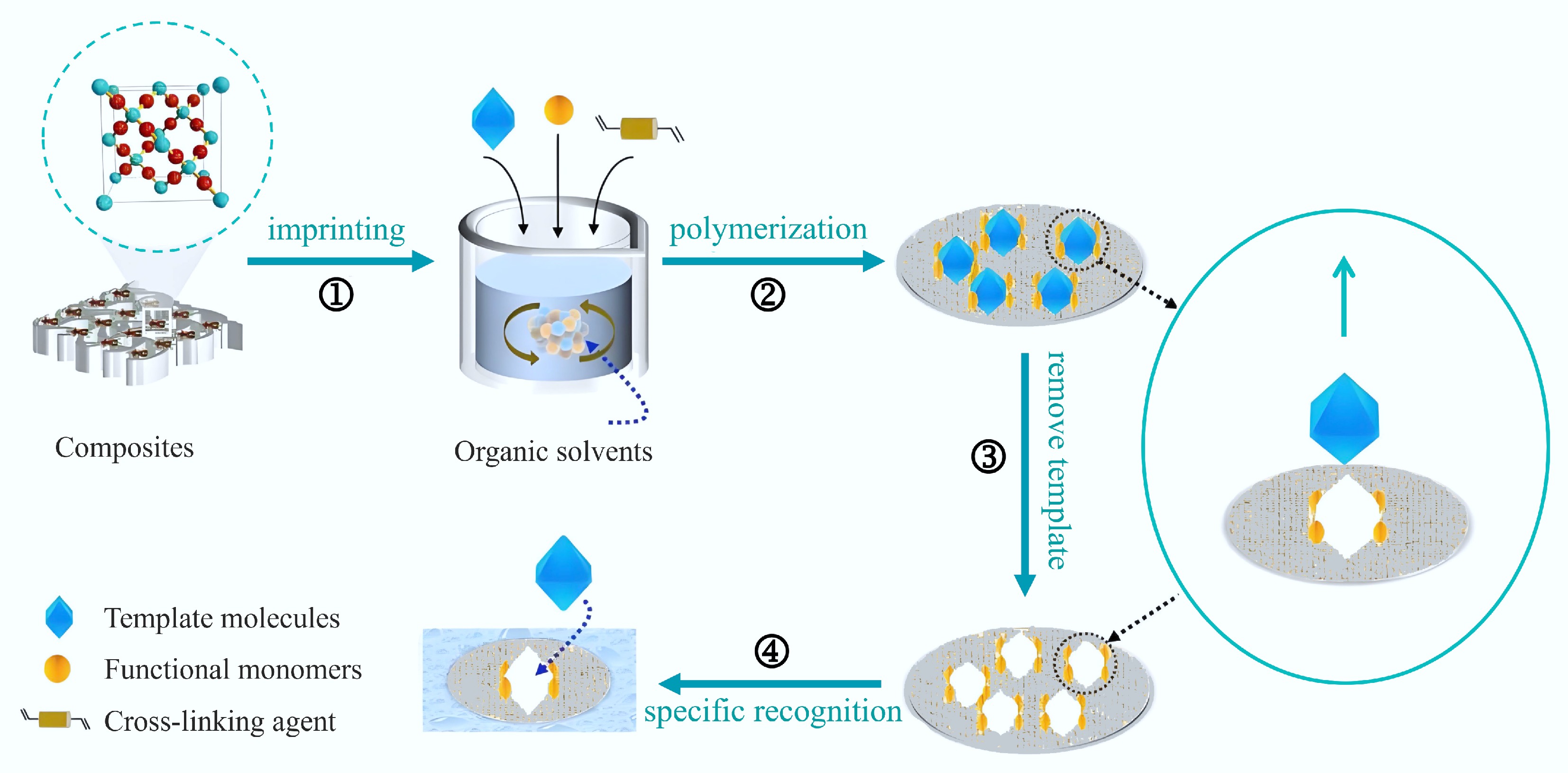

Different methods and forces can be used for the polymerization involved in molecular imprinting; however, the polymerization usually involves three main steps: (1) the formation of a pre-polymerized complex by associating the template molecule with the monomer; (2) initiating the polymerization using a crosslinking agent, typically activated by a free-radical initiator; and (3) removal of the template to obtain the imprinted polymer. The second and third steps are important for removing anything that might interfere with the identification of the target contaminant and ensuring the polymer is loaded correctly and can specifically recognize the target contaminant[4]. Removing the template creates holes that match the shape and position of the template's functional groups, providing the polymer with special areas to recognize other molecules. Three different routes for the preparation of MIPs are distinguished according to the polymerization forces, i.e., covalent, non-covalent, and semi-covalent routes, which yield different binding sites due to the different ways in which the templates are attached to the functional monomers[22].

Covalent imprinting, or the pre-organization approach, entails the formation of a covalent bond between the target molecule and the functional monomer, leading to the creation of an imprinted molecule derivative. The polymer then opens the covalent bond to disengage the imprinted molecule under chemical conditions. The preparation steps are shown in Fig. 2a[23]. Due to their strong covalent bonds, these polymers exhibit greater stability and form more precise recognition sites in their spatial structure. However, the robust covalent bonding also presents challenges when it comes to template removal. After the experiment was over, the template contained in the imprinted layer needs to be removed by chemical methods such as pH adjustment[24]. The reaction conditions in this method are demanding, and the selection of monomers is restricted. Typically, the functional monomers used in covalent bonding methods are small molecular compounds. Commonly reported functional monomers include Schiff bases, chelating agents, and borate silanes[25]. The most representative of them are borate esters, which have the advantage of forming relatively stable triangular-shaped structures. In contrast, tetragonal-shaped borate esters are produced in alkaline aqueous solutions or in the presence of nitrogen-containing compounds like NH3 or piperidine. Generally, the ability to modify all targets with polymerizable groups for involvement in the imprinting process is not always possible, which notably limits the scope of covalent imprinting.

Figure 2.

Preparation of MIPs by (a) covalent, (b) non-covalent, and (c) semi-covalent[23].

Non-covalent imprinting, or self-assembly, was pioneered by Professor Mosbach and his research group in Sweden in the late 1980s[26]. This approach depends on the formation of complexes between the template and monomer, where functional monomers and templates are aligned through non-covalent interactions prior to polymerization, including hydrogen bonding, electrostatic forces, hydrophobic interactions, metal chelation, and liganding[27]. Among these, hydrogen bonding is the most commonly employed. Following the crosslinking polymerization reaction, the template is eluted with a suitable solvent to obtain MIPs. The preparation procedure is shown in Fig. 2b. Imprinted polymers exhibit relatively fast binding and release rates when exposed to mild conditions, without the need for complex chemical reactions. However, non-covalent interactions, which govern these processes, are weaker than covalent bonds and can be affected by external factors, potentially resulting in an unclear imprint profile. As a result, careful selection of polymerization conditions is necessary. To drive the equilibrium towards polymer formation, the mixture typically contains a high concentration of functional monomers. This frequently results in the formation of non-specific binding sites, which diminishes the binding efficiency of MIPs to the template[28].

The semi-covalent interactions involve a combination of covalent and non-covalent bonds. In the imprinting process, a covalent bond forms between the functional monomer and the template, whereas rebinding occurs via non-covalent interactions between the two. This dual interaction mechanism allows for improved stability and selectivity compared to purely non-covalent approaches. The preparation steps are shown in Fig. 2c. Semi-covalent interactions offer the benefits of both approaches: these methods integrate the strong affinity and selectivity of covalent bonding with the gentle recognition conditions and fast binding and release kinetics characteristic of non-covalent interactions. Nevertheless, the method encounters limitations in the use of covalent techniques for template removal, while the complex chemical synthesis and isolation processes impede its further progress[29].

In summary, each of the three imprinting interactions has its advantages and disadvantages. However, in practical applications, attention must be paid to the critical parameter of template molecule removal efficiency. Complete removal of template molecules is a prerequisite for ensuring high recognition performance and low background interference in MIBs. The template removal efficiency and residual levels directly depend on the underlying mechanism of the imprinting strategy. Covalent imprinting constructs precise cavities through reversible covalent bonds, requiring specific chemical cleavage for template removal. This approach involves stringent conditions and is applicable to a limited number of monomers. Non-covalent imprinting relies on self-assembled weak interactions, offering simple elution but carrying risks of cavity heterogeneity and high non-specific adsorption; semi-covalent imprinting combines the advantages of both approaches, employing covalent fixation during preparation and non-covalent interactions during recognition, yet template removal still faces technical bottlenecks related to covalent cleavage. Therefore, selecting the imprinting mechanism fundamentally involves a multi-objective trade-off between template removability, recognition accuracy, and process feasibility, forming the core principle for rational design of MIB materials.

Common methods for molecularly imprinted polymer complexation of BC matrices

-

Various techniques are employed for the polymerization of MIPs, with the most common methods involving alkenyl feedstocks through techniques such as precipitation polymerization, emulsion polymerization, suspension polymerization, native polymerization, in situ polymerization, and others[30,31]. Apart from the methods mentioned earlier, other preparation techniques are also available, including electropolymerization, microwave-assisted polymerization, ultrasonic-assisted polymerization, and theoretical calculation-assisted polymerization, which have also been widely used by researchers[32,33]. A variety of polymerization techniques can be utilized during the preparation process to regulate the morphology, particle size, and characteristics of the imprinted cavities in MIPs[34,35]. This paper summarizes four commonly used methods for preparing molecularly imprinted materials based on biochar as the support material, namely precipitation polymerization, emulsion polymerization, electropolymerization, and the sol-gel method.

Precipitation polymerization method

-

Precipitation polymerization is a technique employed to form a molecularly imprinted layer on the surface of a solid substrate. In this approach, the substrate remains the only insoluble element within the reaction system, causing the imprinted polymer to precipitate directly onto its surface. Consequently, this leads to the creation of a non-homogeneous phase system, where polymerization occurs within this heterogeneous mixture[28]. The method does not require precise reaction conditions, making it relatively easy to control and implement; favorable pore structures in the polymer particles can be formed simply by controlling the solvent conditions, reaction time, and temperature. Moreover, it has low cost and high output rate, so it is most commonly used in current research. In previous studies, MIPs prepared from BC via precipitation polymerization have primarily been utilized for the adsorption of water pollutants, e.g., Yang et al.[36] developed molecularly imprinted polymer-coated Fe3O4-BC composites through precipitation polymerization for the recognition and degradation of salicylic acid during advanced oxidation. Jiao et al.[37] synthesized magnetic biochar (MBC) via precipitation polymerization for the adsorption of hygromycin in aqueous samples. You et al.[38] utilized the precipitation polymerization method to develop an effective and environmentally friendly catalyst, which is based on BC and MIT, for the selective degradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) via peroxomonosulfate activation. In addition, composites have been prepared using this method for solid phase extraction, sensors, and Fenton-like systems. For example, Chen & Tian[39] prepared BC functionalized MIPs using precipitation polymerization. The polymers were utilized in dispersive solid-phase extraction (DSPE) in combination with photodiode array detection (HPLC-PDA) and high-performance liquid chromatography for the sensitive detection of CPF in aqueous samples. Han[40] combined the advantages of BC and molecularly imprinted technology to prepare MIPs on the surface of mauve hull BC by the precipitation polymerization method with both stability and selectivity (A-SBC@MIP). In addition, they designed a solid-phase extraction column utilizing A-SBC@MIP to develop a method for detecting metolachlor residues in cereal samples. Cheng et al.[41] enhanced the performance of an electrochemical sensor by integrating Cr2O3, obtained from a metal-organic framework (MOF), silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs), and BC sourced from walnut shells. Furthermore, incorporating MIP into the composite BC/Cr2O3/Ag surface enhanced the selective recognition of Nitrofurazone (NFZ) by the modified electrode (Table 1). A new electrochemical sensor with molecular imprinting, BC/Cr2O3/Ag/MIP/GCE, was developed using the precipitation polymerization method. This sensor offers a highly sensitive and quick detection technique for NFZ, presenting a dependable method for its analysis in biological fluids.

Table 1. Synthesis methods, materials, target molecules and applications of MIBs

Preparation method Composite material Functional monomer Crosslinker Initiator Target molecule Application Ref. Precipitation polymerization MI-FBC MAA EDGMA AIBN Salicylic acid (SA) Water pollution control [36] MBC@MIPs MAA EDGMA AIBN Oxytetracycline (OTC) Water pollution control [37] MIP@BC MAA EDGMA AIBN Naphthalene (NAP) Water pollution control [38] A-SBC@MIP MAA EDGMA AIBN Carbaryl Solid-phase extraction (SPE) [42] MIP@BC MAA EDGMA AIBN Dimethyl phthalate (DMP) Electrical Fenton system [18] A-SBC@MIP MAA EDGMA AIBN Metanaphos Solid-phase extraction (SPE) [40] BC/Cr2O3/Ag/MIP/GCE AM, MAA EDGMA AIBN Nitrofurazone (NFZ) Electrochemical sensor [41] Emulsion polymerization MMIPMs MAA DVB AIBN Tetracycline (TC) Magnetic solid-phase extraction (MSPE) [43] MIPMs MAA DVB AIBN Tetracycline (TC) Solid-phase extraction (SPE) [44] Electropolymerization MIP/TBC/GCE o-PD, o-AP − − Norfloxacin (NOR) Electrochemical sensor [21] IIP-BBC/GCE

(Pb-IIP-BBC/GCE

Cd-IIP-BBC/GCE)L-Cys − − Pb2+, Cd2+ Electrochemical sensor [20] MIP-DBP-CTS/F-CC3/GCE CTS Glutaraldehyde − Dibutyl phthalate (DBP) Electrochemical sensor [45] Emulsion polymerization method

-

During the emulsion polymerization process, a biphasic system is formed by dispersing a pre-polymerized mixture containing an initiator (polar phase) into an oily solvent (nonpolar phase). Surfactants are used to stabilize the system and act as templates for creating spherical micellar MIPs[46]. Zhao et al.[43] introduced the Pickering emulsion polymerization method combined with MIT to prepare magnetic BC composite microspheres. Unlike traditional surfactants, Pickering emulsions are stabilized by solid particles[47,48]. This method offers three main advantages: (1) Pickering emulsion polymerization enables the fabrication of spherical materials with consistent morphology, and the polymerization conditions can be tailored to regulate both the particle size and morphology. (2) BC is effectively dispersed at the interface of the two phases in the Pickering emulsion, addressing the issue of uneven chemical modification. (3) Pickering emulsions are versatile and can accommodate a variety of functional nanomaterials. Their biphasic system is particularly effective in dissolving functional monomers with varying polarities, making them suitable for diverse applications. He et al.[44] utilized BC as a stabilizer for oil-in-water (o/w) Pickering emulsions. They successfully prepared tetracycline-imprinted BC composite microspheres (MIPMs) through emulsion polymerization, achieving customized sizes and excellent homogeneity (Table 1). The adsorption properties of these MIPMs for tetracycline were examined. MIPMs can be used as adsorbents in solid phase extraction (SPE) for the efficient extraction of tetracycline from various samples, including drinking water, fish, and chicken.

Electropolymerization

-

Electropolymerization is a distinct form of MIT, where the polymerization reaction occurs directly on the surface of a conductive electrode, such as gold, platinum, or glassy carbon electrodes. The modes of electropolymerization mainly include constant potential, constant current, and cyclic voltammetry scanning methods, which can effectively control the morphology and thickness of the MIP, etc., through the regulation of parameters such as potential, current, polymerization rate, and potential window[49]. Compared with the traditional block polymerization, electropolymerization is faster and simpler. Furthermore, electropolymerization can be carried out in situ on the working electrode's surface (Fig. 3)[50], allowing real-time monitoring of the entire process on a computer screen. The thickness of the resulting polymer film can also be precisely controlled by adjusting the applied potential, thereby improving the method's reproducibility and accuracy[20]. Chen et al.[21] utilized electropolymerization to create an environmentally friendly electrochemical sensor based on molecular imprinting for the detection of norfloxacin (NOR). Potassium carbonate-activated tea branch bacterial cellulose (K-TBC), known for its high efficiency in waste utilization, was coated onto the surface of a glassy carbon electrode (GCE). The modified electrode was subsequently subjected to electropolymerization to form an MIP layer. The electrochemical sensor was developed, and its electrochemical performance for detecting NOR was extensively studied. Zhou et al.[45] designed the MIP-DBP-CTS/F-CC3/GCE electrochemical sensor, which demonstrates exceptional selectivity and sensitivity for the detection of dibutyl phthalate (DBP) via electropolymerization. By utilizing the benefits of MIT and F-CC3 biomass material, the sensor achieved enhanced selectivity and sensitivity for the detection of DBP, with the results proving to be highly satisfactory. Mao[20] designed an innovative electrochemical sensor with high conductivity and selectivity, specifically for the detection of Pb2+ and Cd2+ ions. They used nano-ball milling BC (BBC), which was prepared through a high-temperature pyrolysis and ball milling process, as the electrode substrate material (Table 1). Electropolymerization was then applied to create the ion-imprinted polymer, improving the sensor's selectivity and sensitivity for Pb2+ and Cd2+ detection.

Figure 3.

Simplified schematic of MIP electropolymerization on the electrode surface[50].

Sol-gel method

-

MIPs based on sol-gel polymer matrices are synthesized by condensing organo-modified silanes, which results in hybridized sol-gel or dry gel materials[51]. The sol-gel reaction occurs in environmentally friendly solvents such as ultrapure water and ethanol, which facilitate straightforward pH adjustments and proceed at moderate temperatures (usually ranging from 0 to 100 °C). This versatile reaction environment is particularly advantageous for imprinting templates that are sensitive to pH and temperature, such as biomolecules[52]. This approach provides a distinct benefit in the preparation of water-compatible MIPs, making them ideal for use in environmental and biological applications. The high cross-linking density of these MIPs imparts thermal stability, rigidity, and a porous structure. Moreover, the sol-gel technique allows for the fabrication of MIP films on specific substrates, offering precise control over their thickness[31]. Consequently, sol-gel-based MIPs present several advantages over traditional MIPs, such as a more straightforward fabrication process, the chemical stability of the substrate, the use of an environmentally friendly solvent (aqueous solution), and the application of mild reaction conditions (ambient temperature)[53]. Luo et al.[54] synthesized magnetic molecularly imprinted graphene (MGR@MIPs) by utilizing magnetic graphene as the support matrix and 4-nitrophenol (4-NP) as the template. This composite was then integrated with HPLC for the analysis and isolation of 4-NP in real sample matrices. Güney & Cebeci[55] developed an imprinted sol-gel membrane-modified electrode immobilized on a carbon nanoparticle (CNP) layer for the selective and sensitive electrochemical determination of theophylline (TP). The sensor was fabricated using the sol-gel method. The imprinted sol-gel membrane, modified with the electrode and immobilized on a CNP layer, leverages the advantages of carbon nanoparticles. These include reactive surface sites, a very high surface area, excellent electrical conductivity, and abundant adsorption sites, all of which enhance the performance of the electrochemical sensor for TP detection[56]. The properties of the utilized carbon nanoparticles are similar to those of BC, which lays the foundation for future BC preparation applications.

In summary, the characteristics, advantages, and disadvantages of the four methods have been compiled in Table 2 to provide a clearer illustration of their differences.

Table 2. Advantages and disadvantages of precipitation polymerization, emulsion polymerization, electrochemical polymerization, and sol-gel methods

Preparation method Key feature Advantage Limitation Ref. Precipitation polymerization Heterogeneous reaction, polymer precipitation on substrate surface Simple operation, controllable pore structure, low cost, high yield Imprint sites may be buried, high mass transfer resistance, high solvent consumption [28] Emulsion polymerization Biphasic system, surfactant-stabilized micelles as templates Enables preparation of nano-/micron-scale spherical materials with tunable particle size and morphology, featuring uniform biochar dispersion Requires surfactant removal, involving complex processes with poor reproducibility [43] Electropolymerization Electrochemical in-situ polymerization on conductive substrates Precise film thickness control, process monitoring capability, excellent reproducibility, and rapid response Limited to conductive substrates, restricted monomer selection, and film uniformity dependent on parameter optimization [49] Sol-gel method Silane precursors undergo hydrolysis and condensation

to form gelsMild conditions, aqueous phase compatibility, high thermal stability and mechanical strength, excellent film-forming properties Gel shrinkage may cause cavity deformation, slower mass transfer, and complex kinetic control [51] Selection of synthetic materials

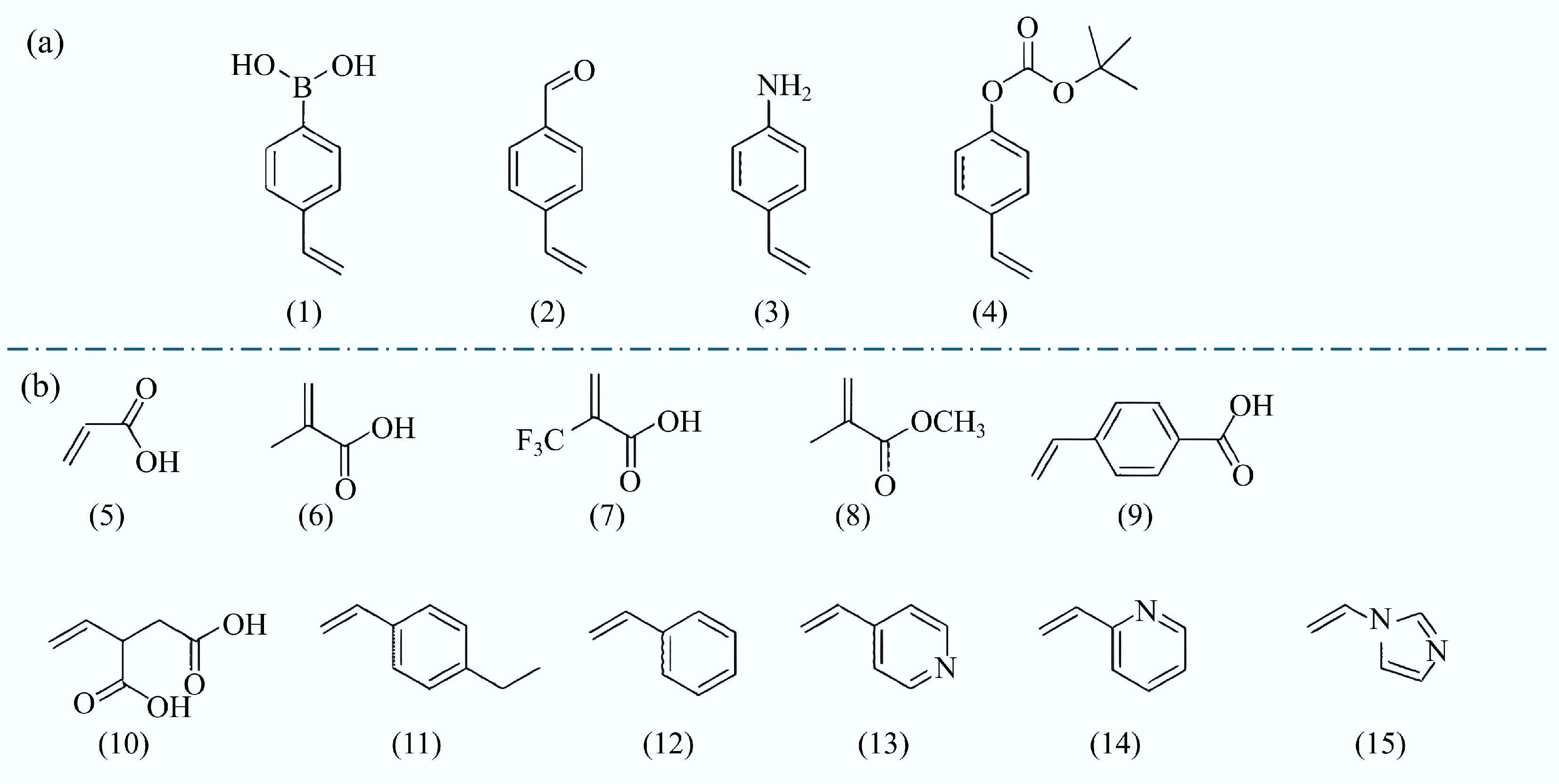

Functional monomers

-

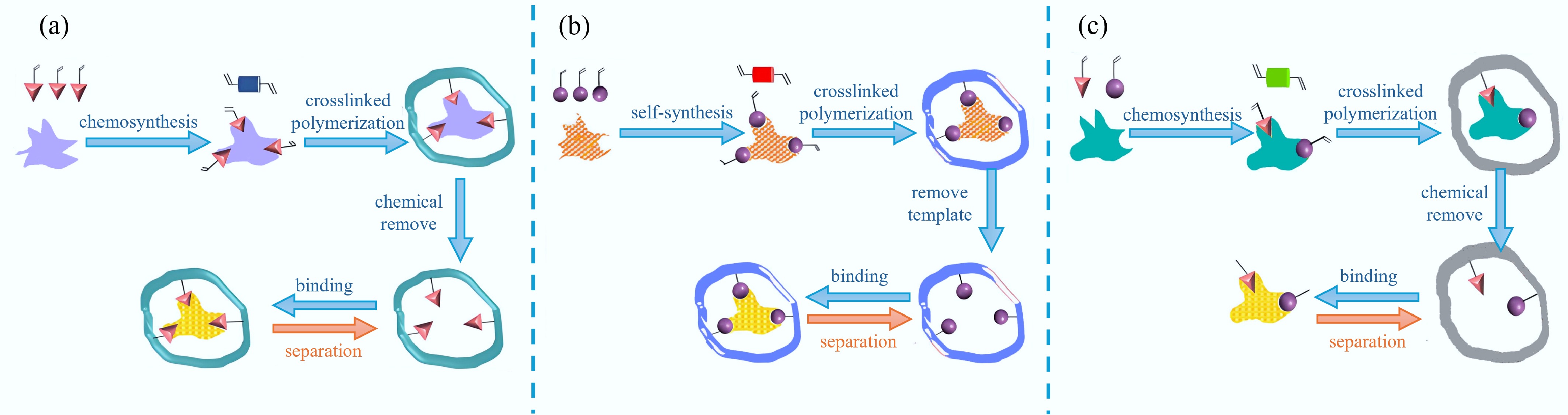

Functional monomers play a key role in the synthesis of MIPs. These monomers possess functional groups, such as amino, carboxyl, and pyrrolyl groups, which enable specific interactions with template molecules. These interactions may be non-covalent, including hydrogen bonding, electrostatic forces, and π-π stacking, or covalent, which results in the creation of a complex between the functional monomer and the template. This interaction allows the template molecules to 'embed' into the polymer, creating specific recognition sites. Once the template molecules are removed, the vacant sites within the polymer are capable of selectively identifying target molecules that share structural similarities with the initial template. The common functional units are shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4.

Common functional monomers used in the molecular imprinting process. (a) Covalent. (1) 4-vinyl phenylboric acid, (2) 4-vinyl benzaldehyde, (3) 4-Vinyl aniline, and (4) Tert-butyl p-phenyl carbonate. (b) Non-covalent. (5) Acrylic acid (AA), (6) Methacrylic acid (MAA), (7) Trifluoromethylacrylic acid (TFMAA), (8) Methyl methacrylate (MMA), (9) P-vinylbenzoic acid, (10) Itaconic acid, (11) 4-ethylstyrene, (12) Styrene, (13) 4-vinylpyridine (4-VP), (14) 2-vinylpyridine (2-VP), and (15) 1-vinyl imidazole[58].

Methacrylic acid (MAA) is one of the most widely utilized functional monomers, often regarded as a 'universal' monomer due to its ability to both donate and accept hydrogen bonds. Zhang et al.[58] further discussed the reasons behind MAA's versatility in molecular imprinting, explaining that its tendency to dimerize enhances the imprinting effect, thereby increasing the efficiency of the MIP synthesis process, as illustrated in Fig. 5. Yang et al.[36] utilized methacrylic acid as the functional monomer within Fe3O4-based BC-coupled surface-imprinted polymers, aiming to selectively recognize and degrade salicylic acid in the context of advanced oxidation processes. When selecting functional monomers, it is important to consider their affinity for the target molecule, ensuring that those with a higher affinity are chosen for optimal performance. Chai et al.[59] utilized 3-aminophenylboronic acid (APBA) as a functional monomer, with grapefruit peel serving as the raw material for BC, to develop a highly sensitive sensor for the detection of ribavirin (RBV) in food and water resources. Borate affinity ligands, commonly used as functional monomers for the adsorption of cis-diols like ribavirin makes the use of APBA as a functional or self-polymerizing monomer an effective approach, simplifying the synthesis process. The boronic acid groups in APBA selectively interact with the cis-diol groups of RBV, enhancing the sensor's selectivity and sensitivity for ribavirin detection[60]. So the choice of functional monomers is based on their suitability for detecting the target molecule. In addition to their versatility, functional monomers come with certain limitations. Commonly used monomers for electropolymerization include o-phenylenediamine[61], phenol[62], pyrrole[63], thiophene[64], and dopamine[65]. The binding of these monomers to template molecules is typically achieved through non-covalent interactions, such as hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, or π-π stacking. For instance, Hosseini et al.[66] developed xanthan gum-BC-Fe3O4 molecularly imprinted biopolymer hydrogels, which served as magnetoresponsive electrochemical enantioselective sensors for recognizing L-Trp, using dopamine as the functional monomer. Furthermore, functional monomers can also be used as bifunctional monomers. In this context, Chen et al.[21] employed NOR as a template molecule, in conjunction with o-phenylenediamine (o-PD) and o-aminophenol (o-AP) serving as bifunctional monomers, to develop an electrochemical sensor. Utilizing bifunctional monomers facilitates the creation of more stable and selective recognition sites, thereby improving the sensor's ability to detect target molecules effectively.

Figure 5.

(a), (b) Illustration of a comparison of imprinted polymers, and (c), (d) non-imprinted polymers formed from functional monomers with or without dimerization ability[58].

Crosslinking agents

-

Crosslinking agents play a critical role in the synthesis of MIPs. As polymer growth occurs, it typically 'traps' around the template molecules, resulting in the formation of specific cavities tailored to the template[57]. They are usually chemicals with multifunctional groups. Cross-linkers make the polymer network structure more stable during the polymerization process by forming chemical crosslinks. The use of crosslinking agents can effectively control the spatial structure of polymers and improve the physical stability of polymers so that they can withstand the effects of the external environment (e.g., temperature, pH changes, etc.) during use. It can also control the polymer's pore structure and surface properties, thus affecting its molecular recognition selectivity and efficiency. The choice and amount of cross-linker play a crucial role in determining the selectivity and binding capacity of MIPs[67]. Generally, using an inadequate quantity of cross-linker results in weak mechanical stability, as the degree of crosslinking remains low. Conversely, excessive cross-linker can lead to a lower density of recognition sites per unit mass within the MIPs[57]. Jiao et al.[37] fabricated molecularly imprinted magnetic BCs (MBC@MIPs) by incorporating ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA) as the cross-linker, illustrating their selective adsorption efficiency for oxytetracycline (OTC) in aqueous samples[38]. In a similar approach, Li et al.[68] developed magnetic BC for the adsorption of sulfamethoxazole, employing 40% glyoxal as the cross-linking agent and MMBC as the functional monomer. Furthermore, recent advancements in cross-linker development have been reported, for example, Hamdan et al.[69] synthesized vinyl imidazolium ionic liquid cross-linkers to overcome molecular imprinting under aqueous conditions using non-covalent interactions and demonstrated that the newly developed cross-linked ionic liquids overcame the problem of synthesizing aqueous MIPs. Moreover, the biggest direction of BC-based molecularly imprinted polymer application is water pollution control. The non-covalent method is widely used as a fast and straightforward method of molecularly imprinted polymer synthesis, so using vinyl imidazolium ionic liquids as a crosslinking agent might make BC-based MIPs more stable in water treatment.

Initiator

-

The initiator is a chemical substance that initiates the polymerization reaction to synthesize MIPs. The initiator decomposes under certain conditions, generating free radicals or ions that initiate the polymerization of monomers. The choice of the initiator is crucial in controlling the polymerization process, as it influences the polymerization rate, molecular weight, and ultimately the polymer's properties. These factors affect the rate of polymerization, reaction temperature, and the final characteristics of the polymer, including its structure, porosity, and recognition ability. Adjusting polymerization conditions can further impact these attributes. Among the initiators commonly employed in the synthesis of MIPs are benzoyl peroxide (BPO)[70,71], 2,2-dimethoxy-2-phenylacetophenone (DMPA)[72], and azo compounds such as 2,20-azino-bis(2-methylpropionitrile) (AIBN)[30,73] and 2,20-azino-bis(2-methylpropanenitrile)[30,73], 20-azobis(2,4-dimethyl)valeronitrile (ABDV)[74]. Azo compounds are commonly employed as initiators, with azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) being particularly favored due to its ease of use at decomposition temperatures ranging from 50 to 70 °C[57]. For example, Yao et al.[75] used azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) as an initiator to construct an electrochemical sensor using ZnWO4/γ-Fe2O3 magnetic MIPs modified on a glassy carbon electrode for the determination of chloramphenicol (CAP). Viltres-Portales et al.[76] reported the use of an amidine-functionalized initiator, 2,2'-Azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride (AAPH) is often used as an initiator in the synthesis of MIPs due to its ability to initiate polymerization under mild conditions. In the context of electrochemical sensors, AAPH has been employed to synthesize MIPs specifically designed for the selective recognition of methotrexate. By utilizing AAPH as the initiator, the polymerization process can be carefully controlled, leading to the formation of imprinted sites that can selectively bind methotrexate molecules. Moreover, it is even possible to use no initiator in case certain conditions are reached during the synthesis, for example, Panagiotopoulou et al.[77] demonstrated through several embodiments that it is possible to synthesize MIPs without the addition of any external initiator. This can be achieved by using at least one monomer in the precursor mixture that undergoes self-initiated photopolymerization or thermal polymerization. Their approach showed that high polymerization yields could be obtained even at high monomer dilutions, which are common in precipitation polymerization. Additionally, this method produced high-fidelity imprinted sites, making it a promising approach for the synthesis of MIPs without the need for traditional initiators.

-

BC is a highly effective substrate material for applying molecular imprinting techniques, and its combination exhibits significant synergistic effects. In many applications, the synergistic effect of combining these two components can significantly enhance the performance of the materials. In the process of pollutant removal, MIT enhances the molecular recognition capacity of BC, allowing it to effectively adsorb specific target pollutants. Additionally, the high specific surface area and abundant functional groups of BC further boost the adsorption performance of the imprinted materials. Furthermore, BC's good electrical conductivity and catalytic properties enable it to play a synergistic role with the imprinted molecules in the catalytic reactions, thus improving the catalytic efficiency. To further improve the performance of the composites, they can be modified. There are two primary methods of modification: one involves the surface modification of BC prior to molecularly imprinted polymerization; the second involves the surface modification of pre-formed BC-based MIPs with hydrophilic components to enhance their hydrophilicity after the polymerization of BC-based MIPs is completed.

Synergistic effects

-

The synergy between MIT and BC extends far beyond simple addition, rooted in the deep integration of multiple elements: First, BC itself provides a non-selective, high-capacity adsorption background through physical adsorption and functional group complexation, while the MIPs layer offers highly selective recognition sites. Their collaboration enables a cascading process of 'rapid capture-precise targeting' of analytes within complex matrices, proving particularly crucial in systems where structurally similar compounds like antibiotics coexist. Second, BC serves as an electron donor or conductor. For instance, in Fenton-like reactions, BC promotes Fe(III)/Fe(II) cycling while pollutants enriched by MIPs are degraded by reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated in situ on the BC surface. This achieves integrated 'recognition-enrichment-catalytic degradation', enhancing catalytic efficiency. Additionally, the porous BC framework provides robust support for MIPs, preventing their collapse due to shrinkage during drying or operation. This effectively maintains the three-dimensional structure of imprinted cavities, thereby enhancing the material's long-term stability and regeneration capacity.

As shown in Table 3, the MIB composite successfully integrates the advantages of its components, forming complementary properties. It inherits BC's high adsorption capacity, low cost, and excellent stability while combining the high selectivity of MIPs. Compared to emerging crystalline porous materials like MOFs and COFs, MIB demonstrates significant advantages in aqueous stability and preparation cost. Particularly when treating complex environmental samples—such as wastewater containing high concentrations of background interferents—its integrated 'recognition-enrichment' capability offers irreplaceable potential for selective environmental remediation and complex matrix sensing. However, MOFs/COFs retain advantages in pore size uniformity and specific surface area, making them suitable for scenarios requiring ultra-precise separation.

Table 3. Performance comparison of MIB composite materials with other adsorption/recognition materials

Material type Adsorption capacity Selectivity (imprinting factor) Recyclability Cost Primary application scenario Unmodified BC Medium-high Low Medium Low Non-selective adsorption water purification Standard MIPs Medium High High Medium-high Solid-phase extraction, sensor identification MIB composite material High High High-very high Medium Selective environmental remediation, sensing, advanced catalysis Metal-organic framework (MOF) Very high Medium-high Low-medium (poor water stability) High Gas storage, catalysis, specific adsorption Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) High Medium-high Medium High Chromatographic separation, catalysis, precision adsorption Surface modification of BC

-

Through surface modification of BC, different functional materials can be introduced to enhance the material’s properties and its selectivity to specific molecules. The modified BC carries a specific material or moiety that can undergo a specific chemical reaction with the target molecule, thus improving the adsorption capacity and selectivity. Two modifications that have a significant synergistic effect on molecular imprinting are described below.

Magnetic BC

-

Active metal substances are incorporated into the BC structure through the combination of feedstock and metal precursors, leading to the creation of active interfaces and binding sites[78]. This method can notably enhance the adsorption capacity, catalytic performance, and magnetic properties of BC-based catalysts[79]. Molecularly imprinted magnetic BC materials (magnetic BC materials) are characterized by introducing magnetic substances, such as magnetic nanoparticles. This approach allows for the quick separation and recovery of materials through the application of a magnetic field during use. Furthermore, magnetic materials tend to exhibit greater stability and maintain strong performance over multiple cycles of reuse. For example, Cui et al.[80] designed magnetic surface MIPs to effectively remove quinoline, which exhibited only a slight decrease in adsorption capacity after undergoing eight cycles. Similarly, Tan et al.[81] created a magnetic MIP for ofloxacin, which proved to be reusable and easily recyclable via magnetic separation. Zhao et al.[43] synthesized magnetic BC-based MIPs using BC and iron oxide to achieve highly selective removal of tetracycline from water. Identifying the optimal preparation conditions during the modification process is essential, as it plays a key role in ensuring the high selectivity of magnetic BC and facilitates its subsequent regeneration and recycling[82]. In addition, magnetic BC materials are more susceptible to further surface modification and functionalization, combining the advantages of other materials, such as photocatalytic properties. This can lead to their application in environmental treatment, drug release, and food safety testing.

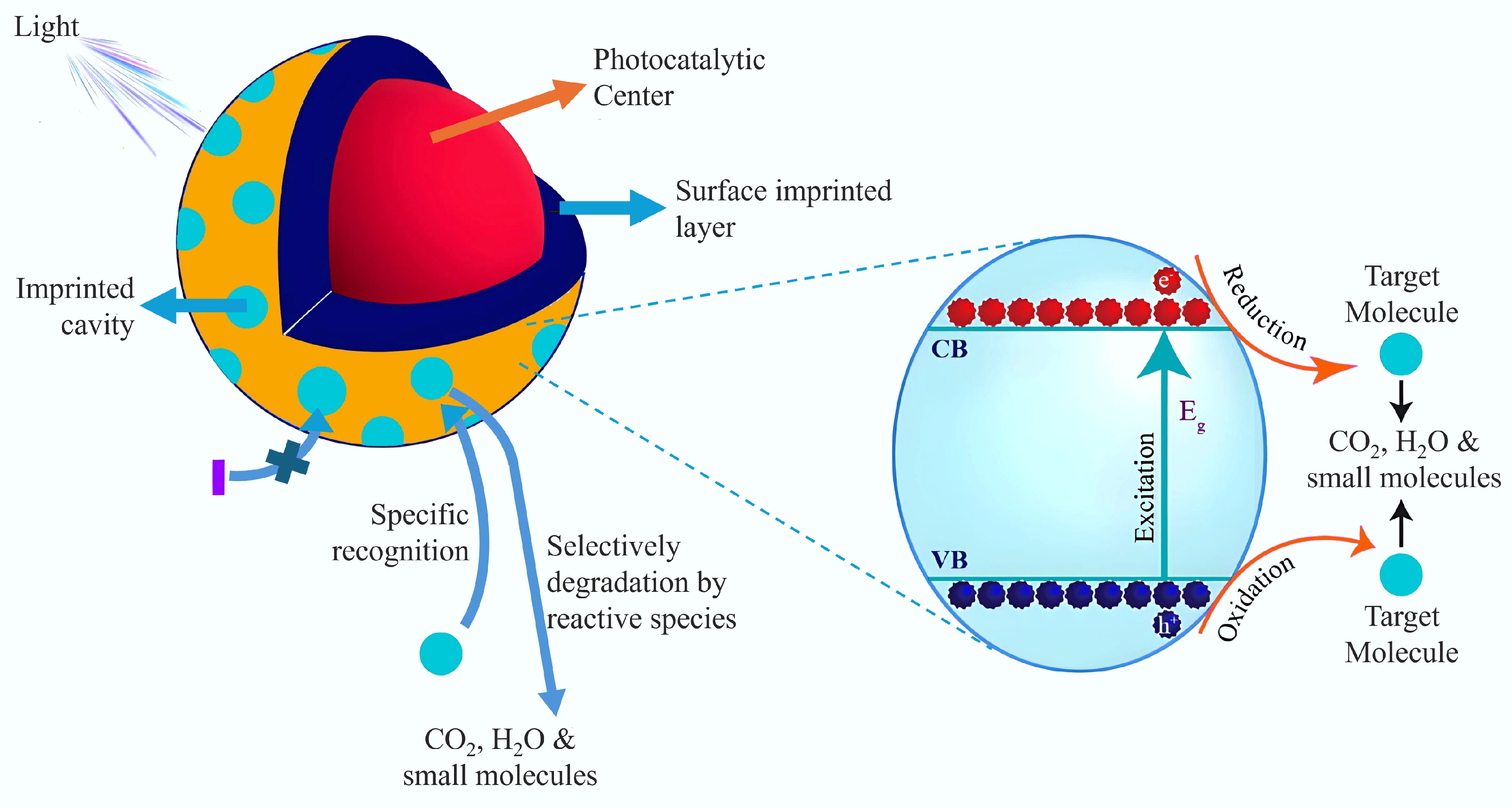

Loaded photocatalytic materials

-

The process of photocatalysis has found widespread use in the degradation of organic pollutants[83]. By combining molecular imprinting with BC photocatalytic materials, the materials can be targeted to adsorb and degrade the target pollutants. The photocatalyst's imprinted cavities selectively recognize and capture the target pollutants, facilitating their initial photodegradation, even in the presence of other competing contaminants[84−86], as whose degradation principle is shown in Fig. 6[87]. This process is capable of capturing light energy to transform pollutants into non-toxic byproducts, including water and carbon dioxide, which is especially important in environmental remediation. Moreover, the photocatalytic process does not require the addition of chemicals, which reduces secondary pollution and chemical usage. Commonly used photocatalysts include TiO2[88], g-C3N4[89], Zn2S4[90], WO3[91], metal-organic frameworks[92,93], CeO2[94], and SrTiO3[95]. Moreover, besides photodegradation and selectivity advantages, MIPs can still show unconventional benefits for photocatalysts. A synergistic effect with the target molecule can be achieved by selecting the appropriate template polymer and photocatalyst. In a study conducted by Shen et al.[96], a MIP coating was applied to P25 TiO2 for the photodegradation of the toxic pentachlorophenol (PCP). Rather than utilizing PCP as the template molecule, they chose 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP) as a pseudo-template to create imprinted cavities, thereby reducing toxicity during the synthesis process. These imprinted cavities specifically recognize and bind to the PCP molecule via molecular interactions, including hydrogen bonding. This interaction establishes a distinct microenvironment that arranges the PCP molecules in a particular orientation within the cavity[96]. MIP photocatalysts facilitate a more controlled and selective degradation pathway by guiding the degradation process through precise binding and orientation within the imprinted cavities. This selective interaction helps reduce the generation of harmful by-products during the pollutant degradation process[87]. In addition, BC as a substrate accelerates the transfer of photogenerated carriers and enhances the adsorption capacity for the target pollutants. Lyu et al.[83] developed a novel catalyst, MIP-CeO2@BC, for the targeted identification and removal of pollutants. This composite photocatalyst, constructed with specifically imprinted cavities on the surface of CeO2, was tailored for the removal of p-chlorophenols (4-CPs) through both adsorption and photodegradation processes. The material demonstrated resistance to interference from dissolved organics in complex aqueous matrices, achieving more than 60% removal of 4-CPs even in the presence of high concentrations of glucose, humic acid, or tryptic proteins. Mechanistic analysis revealed that the composite selectively uptakes 4-CP, modifying the main degradation pathways. These pathways involve photogenerated electrons (e), holes (h), and hydroxyl radicals (–OH), which were identified as the primary active species for degrading 4-CP. Part of the photogenerated electrons can be transported through BC via 'tunneling' to activate the degradation of 4-CP captured in the imprinted cavities, thus enhancing the overall photocatalytic degradation process.

Figure 6.

Principle of MIP selective photocatalytic degradation[87].

Molecularly imprinted BC photocatalytic materials have dual functions of adsorption and catalysis. They can remove pollutants while further degrading or transforming them by a photocatalytic process. This multifunctional property enables photocatalytic BC to be applied in a broad range of applications, including water treatment, air purification, sludge treatment, and energy recovery.

Surface hydrophilic modification of molecularly imprinted materials

-

Since the application environment of composites is usually aqueous, the hydrophilicity of the materials is crucial. In addition to using hydrophilic functional monomers, cross-linkers, or co-monomers, another promising approach involves modifying MIBs after polymerization. This post-modification strategy enhances the surface hydrophilicity of MIPs, offering greater versatility and broader potential applications compared to methods that rely solely on the use of specially designed hydrophilic monomers or co-monomers during synthesis. Post-modification of preformed MIP particles bypasses the need for complex and time-consuming optimization of the MIP formulation, allowing for more flexible and efficient preparation methods[30]. By enhancing the hydrophilicity of MIPs, the post-modification process can significantly reduce nonspecific adsorption, which is often driven by hydrophobic interactions. This improvement facilitates the recognition of target molecules in aqueous environments, making the MIPs more selective and effective in various sensing and separation applications. This strategy also offers the advantage of tailoring the surface properties of MIPs to meet specific requirements without needing to redesign the entire polymerization process[97]. In other words, the hydrophilicity of pre-prepared MIPs can be greatly improved by modifying their surface with hydrophilic components. Common modification techniques typically include the alteration of hydrophilic layers, functional groups, and similar structures[15].

Modification of the hydrophilic layer

-

Modifying the hydrophilic layer of MIPs provides a practical approach for developing water-responsive MIPs. Song et al.[98] developed two types of hydro-compatible MIPs by directly applying an ultrathin hydrophilic shell onto the surface of non-grafted imprinted microspheres, allowing for the control of shell thickness and uniform particle size. For the hydrophilic functional monomers, MAA, NIPAAm (an uncharged monomer), and a charged monomer were chosen and incorporated into a single-pot process for two subsequent modifications. To achieve the optimal interaction factor (IF), the polymerization kinetics were closely monitored by adjusting the irradiation time, which controlled the thickness of the hydrophilic layer. The hydro-compatible MIPs exhibited improved performance over unmodified MIPs, with reduced nonspecific adsorption and enhanced specific recognition. Additionally, the hydrophilic layer effectively inhibited the interference from undesired substances[99−101]. Furthermore, the MIPs based on PNIPAAm exhibited enhanced recognition properties, attributed to their appropriate hydrophilic surface. These hydro-compatible MIP microspheres, with their ultrathin hydrophilic shell, offer a promising method for detecting specific substances, particularly in complex matrices.

Modification of hydrophilic groups

-

In addition, post-modification of MIP by introducing hydrophilic groups to the MIP surface is another way to improve its hydrophilicity[30]. As a result, many researchers have concentrated on attaching hydrophilic groups to the surface of pre-formed MIPs by employing chemical methods, including ester hydrolysis and the ring-opening reactions of epoxy groups. Ji et al.[102] developed MIPs by utilizing 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetylglucopyranoside as the functional monomer. They then hydrolyzed the ester groups on the pre-formed MIPs to introduce hydroxyl groups. The findings revealed that the hydrolysis of ester groups significantly enhanced the water dispersion stability and hydrophilicity of the MIPs, while preserving the integrity of the specific recognition sites in the pre-formed MIPs. This modification led to an increased adsorption capacity compared to the original MIPs. The hydrophilic MIPs obtained under optimal SPE conditions were successfully used to selectively separate and detect five cyclic enol ether terpene glycosides in aqueous media, and satisfactory analytical results were obtained. In addition, Manesiotis et al.[103] detailed the fabrication of hydro-compatible MIPs aimed at the selective extraction of riboflavin from beverages, achieved through the addition of hydrophilic functional groups on the MIP surface[76]. They first synthesized riboflavin tetraacetate imprinted polymers through noncovalent molecular imprinting. The functional monomer 2,6-bis(acrylamido)pyridine was employed, with PETA acting as the cross-linking agent, chloroform serving as the solvent for pore formation, and AIBN used as the initiator for free radical polymerization. The MIP underwent an alkaline post-treatment to hydrolyze residual acrylate groups on the polymer matrix, thereby enhancing its hydrophilicity by performing alkaline hydrolysis on the unreacted acrylate groups on the pendant chains. The properties of the final MIP were significantly affected by the conditions used during the alkaline treatment. It was found that using bulky bases and shorter hydrolysis times effectively reduced hydrophilic nonspecific template binding in aqueous solution, while preserving the integrity and recognition capability of the template binding sites. Similarly, He et al.[104] and Puoci et al.[105] prepared specific recognition MIPs with hydrophilic outer layers to selectively extract organophosphorus pesticides and acetaminophen from different aqueous media samples, respectively. However, when hydrophilic functional groups are introduced onto the MIP surface, it is crucial to carefully optimize the reaction conditions to ensure the preservation of the binding site integrity.

-

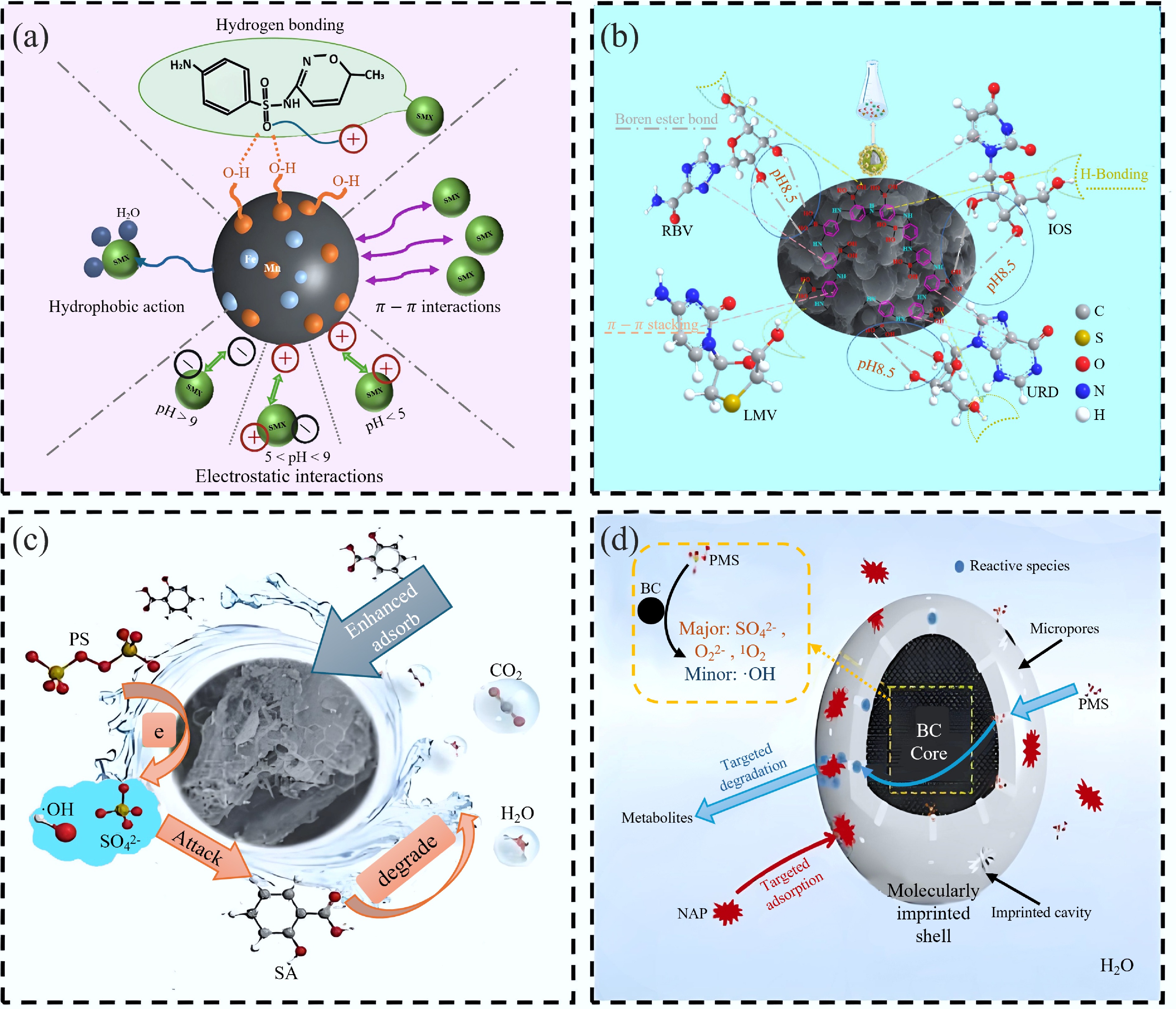

MIBs based on MIT have many applications in environmental pollution control, especially in water treatment. Molecularly imprinted BC can selectively adsorb and degrade target pollutants through its specific recognition ability. They are primarily used to adsorb organic pollutants in aquatic environments that are low in concentration but highly toxic, and their efficient adsorption can reduce the use of adsorbents[106]. For example, Jiao et al.[37] synthesized molecularly imprinted magnetic BC (MBC@MIPs). The material demonstrated selective OTC adsorption in complex aqueous samples and possessed good reusability. Li et al.[68] developed MIP-MBCs by modifying BC with Fe-Mn in an organic solution for the selective adsorption of sulfamethoxazole (SMX) from aqueous solutions (Fig. 7a). The presence of mesopores and oxygen-containing functional groups in MIP-MBCs promoted the development of imprinted cavities within the pores; as a result, the adsorption efficiency for SMX was notably improved. The adsorption capacity for SMX reached a maximum of 25.65 mg/g, exceeding that of non-molecularly imprinted magnetic BC (NIP-MBC) by a factor of 1.34. This study offers valuable insights into improving the practical applications and economic benefits of targeted BC materials in wastewater purification, specifically for SMX capture. Similarly, Chai et al.[59] synthesized novel BC-based boronate affinity MIPs (C@H@B-MIPs) for the adsorption and degradation of ribavirin (RBV) in the environment (Fig. 7b). The C@H@B-MIPs exhibited fast equilibrium kinetics (within 15 min), and an adsorption capacity of 18.30 mg/g was observed, along with outstanding reusability for RBV, highlighting their potential for environmental applications.

Figure 7.

(a) Main and other mechanisms of SMX adsorption onto MIP-BC[68]. (b) Adsorption mechanism of C@H@B-MIPs on RBV, LMV, URD, and IOS[59]. (c) Performance and specific recognition mechanism of Fe3O4/BC as an efficient persulfate activator for removing salicylic acid from wastewater[36]. (d) Mechanisms controlling NAP-targeted degradation in the MIP@BC/PMS system[38].

The adsorption properties of molecularly imprinted BC can also be utilized to adsorb the contaminants together before removing them by the addition of a redox agent. For example, Yang et al.[36] developed a novel Fe3O4-based BC-coupled surface-imprinted polymer for the recognition and degradation of salicylic acid through advanced oxidation (Fig. 7c). After reaching adsorption equilibrium, persulfate (PS) powder was added to the system, continuing the reaction. The material demonstrated an excellent adsorption capacity of 118.23 mg/g and an efficient degradation performance, with an 87.44% removal rate in 240 min. You et al.[38] developed an efficient and eco-friendly catalyst based on BC and MIT for the selective degradation of PAHs using activated peroxymonosulfate (PMS) (Fig. 7d). Their findings demonstrated that the molecularly imprinted BC (MIP@BC) achieved 82% equilibrium adsorption for naphthalene (NAP) within 5 min, exhibiting excellent targeting efficiency. The degradation of NAP was primarily driven by SO4–, O2–, and O2 radicals generated by BC-activated PMS. Additionally, it was proposed that once the imprinted cavities were vacated after NAP degradation, they could continue to selectively adsorb NAP, thereby enhancing the material's reusability.

For the removal of contaminants from soil, there are different conditions, Kurczewska et al.[107] developed composite hydrogel beads based on chitosan (CS) and eclogite-loaded MIPs synthesized by a procedure in which the two solvent volumes were significantly different (Hal@MIPa [b]) and used for the adsorption of antibiotics. The hydrogel beads showed remarkable selectivity, even when other antibiotics were present, and proved highly effective in eliminating tetracycline (TC) from real water samples. When added to the soil, the beads enhanced the adsorption capacity. Pore filling was the main mechanism responsible for tetracycline adsorption onto the hydrogel beads, although other interactions, including hydrogen bonding, π-π stacking, and electrostatic attraction, also contributed. The application of MIBs in soil remains relatively rare. However, since BC can alter soil properties and potentially affect the composition and activity of soil microbial communities[108], BC, as a substrate, may offer better treatment outcomes and lower risks compared to chitosan. In addition, the choice of molecularly imprinted BC catalysts for the oxidation and reduction of pollutants should consider factors such as the properties of BC, cost, and potential environmental risks.

Additionally, real-world environments typically involve multi-pollutant coexistence systems, making the performance of MIBs under such conditions critical for practical applications. Existing studies indicate that when multiple pollutants coexist, MIBs generally maintain high selective adsorption toward their specific template pollutants. Even in the presence of competing substances, their adsorption capacity remains relatively stable. For instance, Yang et al.[36] prepared MI-FBC, which exhibited excellent stability and regenerability across a wide pH range. Beyond significant inhibition by Ca2+ and PO43–, the material demonstrated tolerance toward coexisting anions. Adsorption tests in both mono-compartmental and binary systems using BA as a structural analog revealed outstanding selective adsorption capabilities. Jiao et al.[37] evaluated the selectivity of MBC@MIPs toward OTC, demonstrating minimal impact on OTC adsorption by the presence of five structurally similar competitive antibiotics. Despite interference, the material maintained high OTC adsorption. Secondly, the non-selective adsorption sites provided by the BC substrate simultaneously adsorb other coexisting pollutants. While this may increase the total adsorption capacity for the template pollutant, the apparent selectivity (imprinting factor) decreases. This dual characteristic of 'broad-spectrum adsorption + precise recognition' may offer unique advantages in scenarios requiring simultaneous removal of multiple pollutants. Future designs may incorporate cascaded systems or combine MIBs tailored for different pollutants to achieve hierarchical, deep purification of complex contaminated systems.

Adsorption and extraction

-

Molecularly imprinted materials are extensively utilized in extraction and sample processing, with their primary advantage being a high level of specificity and selectivity when compared to other materials. However, the advantages of MIPs extend beyond these properties. They offer the ability for easy surface modification, enhancing compatibility with aqueous sample environments, and can be integrated with naturally sourced materials, reducing environmental impact without sacrificing their distinctive features. Furthermore, MIP adsorbents' capabilities for analyte preconcentration, enrichment, and efficient cleanup render MIP-based SPE processes highly competitive with traditional extraction methods[17].

Solid phase extraction (SPE)

-

MIP-based solid-phase extraction (MISPE) is a powerful analytical technique used for chemical and biological analysis in complex matrices, offering numerous advantages such as simplicity, high throughput, low cost, robustness, and excellent selectivity[109,110]. Over the past two to three decades, due to its versatility and ease of use, SPE has become the most popular preconcentration method for trace analysis. The widespread adoption of MIPs as SPE adsorbents has led to the development of MISPE. In this process, the adsorbent demonstrates exceptional selectivity for template molecules and their structural analogs, efficiently extracting the target compounds while avoiding the retention of other substances. Since Sellergren[111] first introduced the use of MIPs as SPE adsorbents, their application has gained broad acceptance, particularly due to their high selectivity across a variety of matrices, including biological[112−114], environmental[115−120], and food[121−123] samples, enabling the highly selective extraction of specific analytes of interest. In addition, the good adsorption properties of BC have aroused scholars' interest in applying them in sample pretreatment[124]. Moreover, the synergistic benefits of BC and MIPs enhance the adsorption of the target. Chen et al.[42] synthesized MIPs (A-SBC@MIP) on the surface of activated BC for the adsorption and detection of carbaryl. At optimal ionic strength and pH, the ASBC@MIP adsorbent demonstrated a carbaryl adsorption capacity of 8.6 mg/g, with an imprinting factor of 1.49. Kinetic and isothermal data indicated rapid mass transfer and a high binding capacity (Qmax = 47.9 mg/g). The ASBC@MIP exhibited excellent regeneration properties, and its adsorption of carbaryl was superior to that of its structural analogs. A SPE column packed with ASBC@MIP was developed for the determination of carbaryl in rice and maize, yielding recoveries between 93% and 101% for spiked carbaryl under optimized conditions. The method achieved a detection limit (LOD) of 3.6 μg/kg, with good linearity in the range of 0.01–5.00 mg/L (R2 = 0.994). These results suggest that the MIPs-SPE method developed can serve as a specific, cost-effective approach for enriching carbaryl from food samples. Additionally, He et al.[44] successfully prepared BC molecularly imprinted composite microspheres with tailored size and excellent homogeneity by utilizing BC as a stabilizer in a Pickering emulsion, coupled with the polymerization technique. The composite microspheres could be used for the specific adsorption of tetracycline antibiotics. The use of these materials for extracting tetracycline antibiotics from water, chicken, and fish, when incorporated as fillers in SPE columns, has shown detection limits (LODs) between 3.51 and 3.64 μg/kg, with recoveries ranging from 73.35% to 94.84%. Han[40] utilized the combined benefits of BC and MIP, emphasizing the stability and selectivity of A-SBC@MIP. They explored the preparation technique, morphology, and adsorption characteristics of A-SBC@MIP, and subsequently developed an A-SBC@MIP-based SPE column. This led to the establishment of a method to determine carbinol residues in cereal samples. The A-SBC@MIP-SPE column was developed using A-SBC@MIP as the adsorbent, and the extraction process was optimized through a one-way test. The optimal conditions were determined to be a sample volume of 4 mL, an eluent mixture of methanol : acetic acid (8:2, v/v), and a dosage of 4 mL. The method achieved a limit of detection (LOD) of 2.88 μg/L, with good linearity in the range of 0.01 to 5.00 mg/L (R2 = 0.994). The recoveries for spiked carbinol grains ranged from 93.74% to 101.17%, highlighting that the A-SBC@MIP-SPE-HPLC-UV method developed provides a precise and economically viable solution for both identifying and quantifying carbinol in food samples.

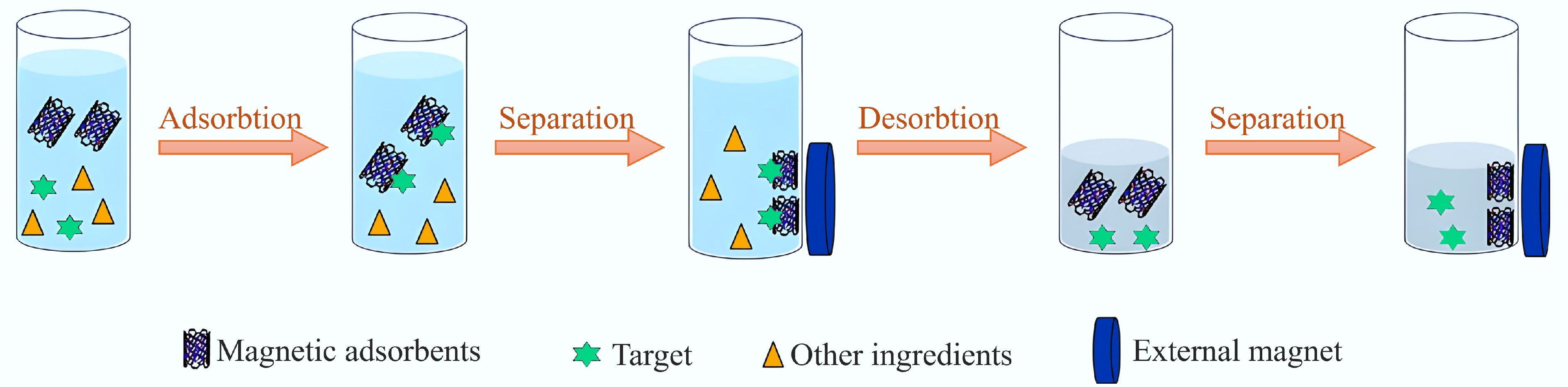

Magnetic solid phase extraction (MSPE)

-

MSPE is an innovative sample pretreatment technique that offers several benefits, including environmental friendliness, a fast separation process, high adsorption efficiency, and ease of automation[125]. MSPE is a magnetic interaction-based SPE sample preparation technique that requires only the magnetic adsorbent and no additional extraction columns[126−128]. In the MSPE process (Fig. 8)[125], the magnetic material is distributed within a suspension or solution that contains the analyte, where it selectively adsorbs the target analyte over time. Importantly, by applying an external magnetic field, the magnetic material can be swiftly separated from the solution or suspension, thereby eliminating the necessity for filtration or high-speed centrifugation. Following desorption, the solution undergoes analysis. This extraction method is more efficient and time-saving compared to conventional approaches. Furthermore, magnetic materials can be easily functionalized through molecular imprinting, improving the adsorbent's selectivity for the target analyte[129−131]. The use of magnetic carbon-based materials has gained popularity, particularly due to their exceptional adsorption capacity for carbon-based cyclic compounds[125]. For example, peanut shell porous carbon has been utilized in the preparation of magnetic porous carbon for SAs MIP[132]. In this method, magnetic porous carbon materials were efficiently synthesized by using peanut shells as the carbon source, which were then modified into vinyl magnetic porous carbon through the reaction with acryloyl chloride. Following this, MIPs were prepared by utilizing vinyl magnetic porous carbon along with MAA as a dual-functional monomer. These materials were then used as adsorbents in MSPE for selectively enriching SAs from real samples before HPLC analysis. The developed method was applied for the quantitative analysis of the four SAs in fish, demonstrating exceptional sensitivity. When compared to NIPs, the selectivity coefficients of the MIPs for the target SAs were found to range from 1.0 to 1.4 times higher. This method exhibits not only excellent sensitivity but also precision and dependability. However, further modification is required to improve their adsorption capacity due to the hydrophobicity of carbon-based materials and their weak interactions with polar or ionic compounds. The advancement of magnetic functionalized composites also includes incorporating ionic surfactants, polymers, ionic liquids, supramolecular compounds, and various other additives. As an illustration, Chen et al. developed a new Fe3O4@SiO2@G@PIL composite, modified with ionic liquids, for the extraction of preservatives from vegetables, and it was found that the ionic liquids not only enhanced the hydrophilicity of the material, but also increased the overall polarity of the material[133−135]. Studies have been carried out to create molecularly imprinted magnetic BC-based materials for magnetic solid-phase extraction through different methods. For example, Zhao et al.[43] utilized BC and Fe3O4 nanoparticles as co-stabilizers in oil-in-water (o/w) Pickering emulsions. The emulsion was then utilized to prepare magnetic BC composite microspheres imprinted with tetracycline (MMIPMs), which exhibited excellent homogeneity and notable selectivity. These MMIPMs were used as adsorbents for the MSPE of tetracycline from a range of samples, such as drinking water, milk, fish, and chicken. When optimal conditions were applied, recovery percentages varied from 88.41% to 106.29%, and the relative standard deviations (RSDs) were found to be between 0.35% and 6.83%.

Figure 8.

Schematic of the MSPE program[125].

Fenton-like systems

-

Recent research indicates that MIT can be applied to modify Fenton-type catalysts, thereby improving their effectiveness in treating recalcitrant pollutants through the Fenton reaction. In a study by Zhang et al.[136], molecularly imprinted iron zeolite (MI-FZ) Fenton catalysts were fabricated through molecular imprinting to selectively target and remove methylene blue (MB). The results indicated that MI-FZ could efficiently and specifically remove MB from a mixture containing both MB and bisphenol A (BPA). However, a significant challenge identified in these studies is that the molecular imprinting process may cause material agglomeration, which subsequently leads to a decrease in their specific surface area. As a solution, porous BC emerges as an optimal option, owing to its high specific surface area, superior electron transport properties, and abundant defect sites. Additionally, BC materials possess intrinsic catalytic properties, and integrating molecular imprinting with catalysis can enhance their catalytic selectivity. Furthermore, porous carbon doped with nitrogen atoms[137−139] has been employed to prepare electro-Fenton anode materials, improving the catalytic performance and ensuring long-term stability of the catalysts.

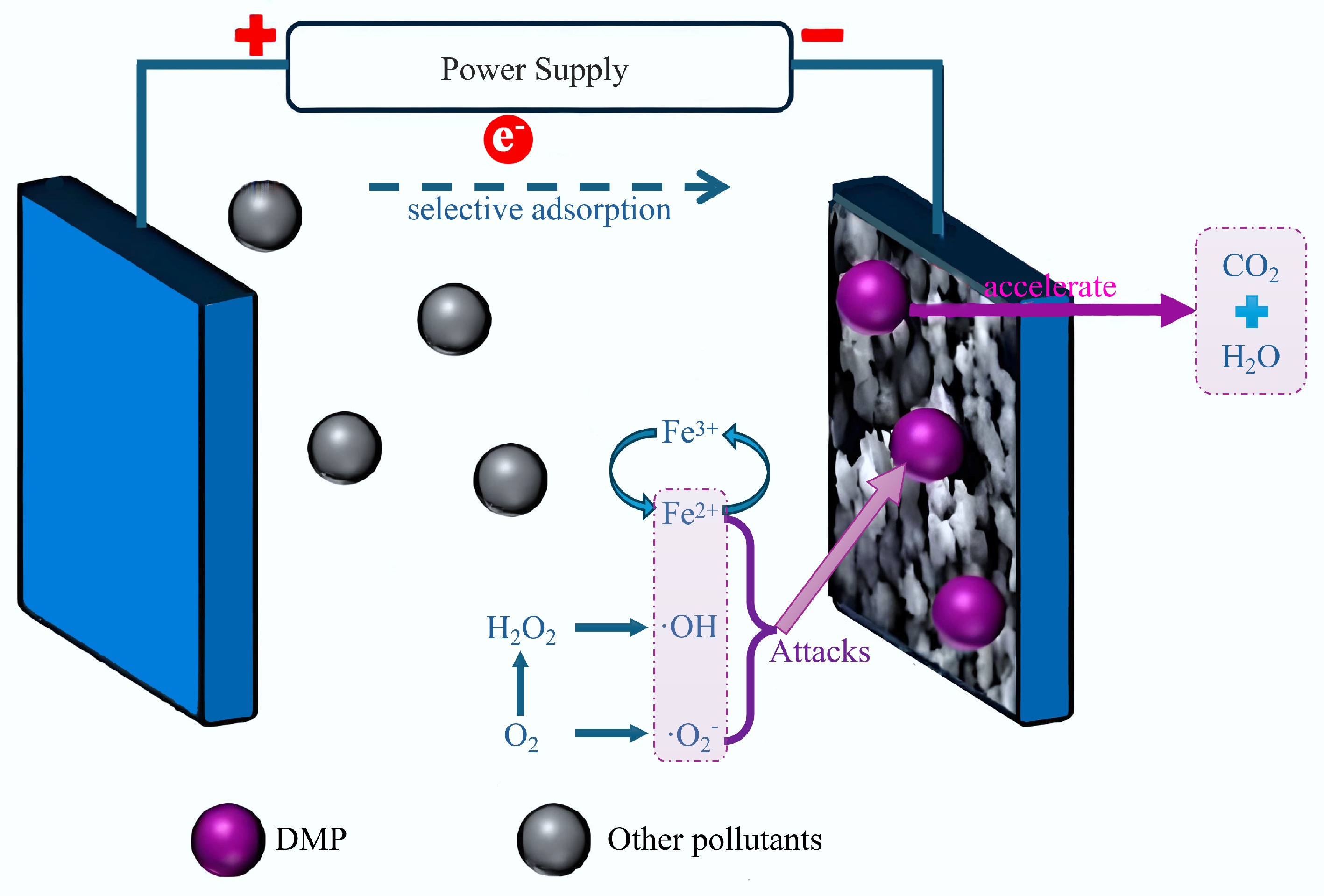

Liu et al.[18] developed an innovative MIP@BC catalyst, this material was modified with a virtual template of phthalates, tailored for its application as a cathode material. This catalyst demonstrated excellent performance in electron-oxygen reduction and H2O2 generation, which significantly enhanced its efficiency in the selective degradation of phthalates within the electro-Fenton process (Fig. 9)[18]. When applied as an electro-Fenton cathode, the catalyst exhibited superior 2-electron oxygen reduction performance and was capable of completely degrading dimethyl phthalate (DMP) within 15 min. Molecular imprinting enhanced the adsorption capacity of MIP@BC for DMP by 40%. The electro-Fenton process mediated by MIP@BC increased DMP degradation by 72% compared to non-imprinted BC (NIP@BC). Additionally, the degradation rates of DMP in river water and domestic wastewater were increased by 51% and 104%, respectively. The degradation was primarily facilitated by reactive oxygen species, particularly OH and O2, with a synergistic effect between targeted adsorption and catalysis. This study offers valuable insights into the selective breakdown of emerging, highly toxic pollutants in complex aqueous environments. The electro-Fenton system demonstrated here has promising practical implications, by degrading dimethyl phthalate in river and domestic wastewater, the toxicity of intermediate by-products is effectively diminished. This study opens up possibilities for the selective detection and removal of phthalates.

Figure 9.

Reaction mechanism for the degradation of DMP using an electrofenton system[18].

Electrochemical sensors

-

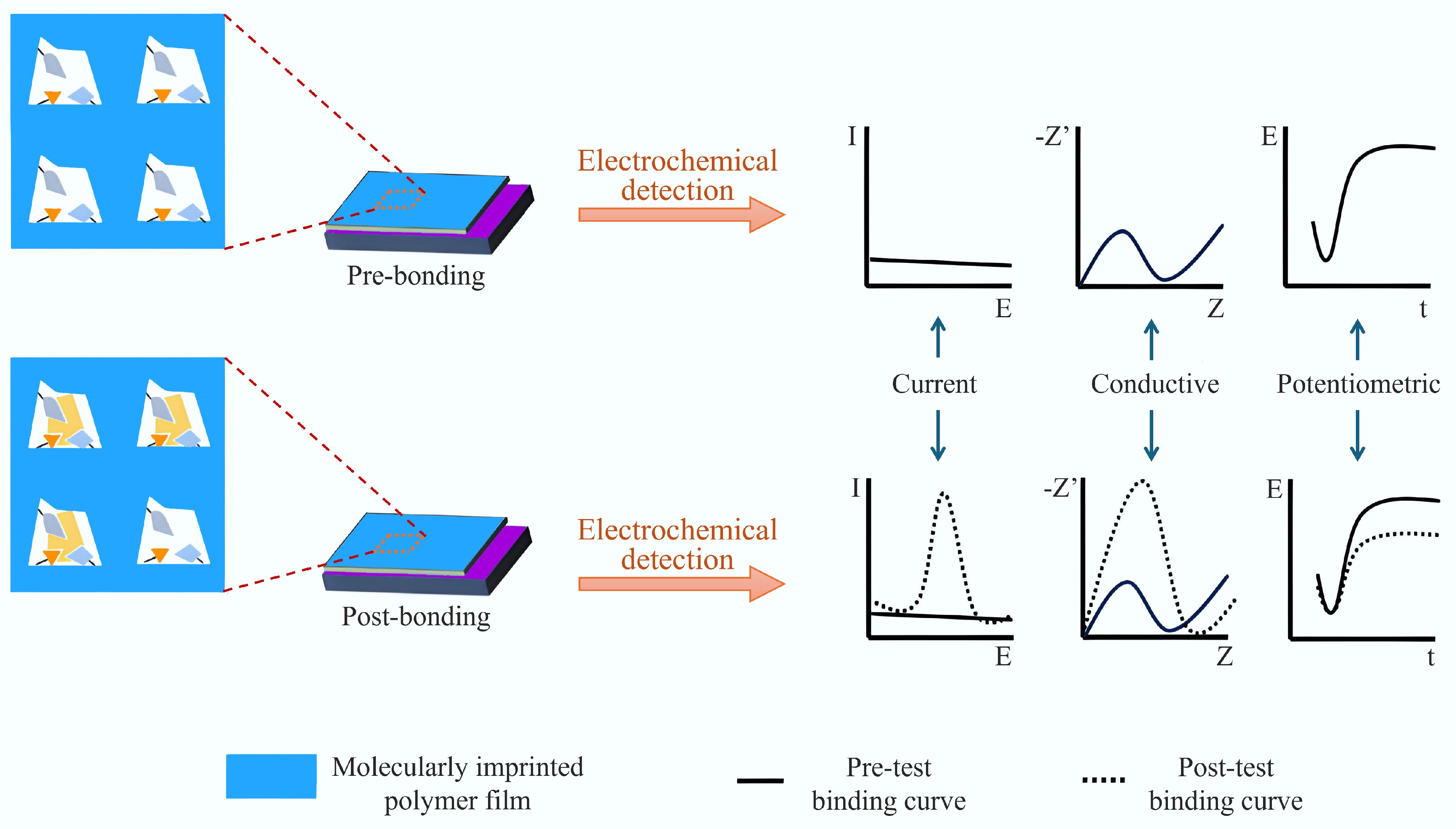

Electrochemical sensors can generally be divided into amperometric, conductometric, and potentiometric types. In amperometric sensors, a specific voltage is applied to induce a redox reaction in the analyte, generating a current; the specific voltage can distinguish the type of substance, and the size of the current can directly reflect the concentration of the substance, so amperometric sensors have the broadest range of use among the three types[140]. Electrochemical sensors based on MIPs have gained significant attention due to their excellent stability, rapid preparation via electropolymerization, and exceptional specificity for target analytes[141,142]. Additionally, MIP electrochemical sensors offer several other advantages, including reusability, low LOD, ease of fabrication, and cost-effectiveness[143,144]. Due to their high specificity, MIP-based electrochemical sensors outperform conventional analytical techniques such as liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS)[27,145]. Currently, MIPs are being directly electropolymerized onto electrode surfaces for the electrochemical detection of target analytes. These high-performance, MIP-based sensors enable precise targeted analysis while ensuring high environmental sustainability, making them a promising tool for various applications in environmental monitoring and other fields[146]. The working principle and classification of molecularly imprinted electrochemical sensors are shown in Fig. 10[20]. BC acts as a carrier and stabilizer for immobilized magnetic agents, owing to its extensive biophilic surface area, eco-friendly properties, and non-toxic nature[147]. These attributes make BC an ideal candidate for use in sensors, particularly in enhancing electron transfer, biocompatibility, and conductivity[148,149]. Thus, MIBs can develop sensors and detectors with good selectivity and sensitivity as the recognition proxies therein. For example, Zhou et al.[45] created a very precise and sensitive electrochemical sensor to find DBP in rice wine by using BC and molecular imprinting, with a detection limit of 0.0026 μM. Chen et al.[21] created an electrochemical sensor for detecting NOR using tea branch BC and molecular imprinting, achieving a detection limit of 0.028 nM. This sensor demonstrated effective performance in detecting NOR in food products like milk, honey, and pork. Hosseini et al.[66] introduced a novel magnetically responsive electrochemical enantioselective sensor for L-Trp recognition, which incorporated filament-derived BC, Fe3O4 nanoparticles, and xanthan gum hydrogel, along with molecularly imprinted polydopamine (MIPDA). The performance of this electrochemical can be enhanced further through stepwise modification of BC. Mao[20] created a highly effective and specific electrochemical sensor to detect Pb2+ and Cd2+, using BC prepared by high-temperature pyrolysis and ball milling as the electrode material, and constructed the sensor through electropolymerization. The electropolymerization method was used to construct a new highly conductive and selective ion-imprinted electrochemical sensor to detect Pb2+ and Cd2+. The results showed that the electrode has excellent reusability and can be reused at least seven times without degrading the sensing signals. To enhance the selectivity and stability of ion-imprinted electrochemical sensors, other research aims to develop an ion-imprinted electrochemical sensor for the sensitive detection of Pb2+ in complex samples. Such a sensor can be constructed by modifying the functional groups on the BC surface using the II hydrothermal method, and carefully selecting appropriate functional monomers. Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs)-doped molecularly imprinted electrochemical sensors (Au@MIP/KHPC/GCE) have been prepared by co-electropolymerization (chloroauric acid, p-phenylenediamine, and bisphenol A), and DFT has been used to investigate the binding mechanism of p-phenylenediamine and BPA. Recently, there has been a focus on a new generation of nanomaterials (e.g., MOF and COF)[150] for modifying electrodes to enhance sensor-related sensitivity and efficiency. Furthermore, the combination of MIPs with covalent organic frameworks (COFs) or MOFs holds promise for enhancing the accessibility of imprinted sites. This synergy offers several advantages, such as improved mechanical strength and a higher specific surface area[151]. Additionally, BC can be integrated with MOF materials to co-modify electrodes, further enhancing the performance of electrochemical sensors. For instance, Cheng et al.[41] introduced a composite material, BC/Cr2O3/Ag, for sensor modification, which utilized Cr2O3 and Ag NPs derived from MOF, and BC sourced from walnut shells. This composite enhances the electrode's effective surface area and electron transfer efficiency, thereby improving the current response. Under optimized conditions, the differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) current response of the modified BC/Cr2O3/Ag/MIP/GCE electrode to NFZ displays a clear linear relationship. The development of this sensor offers a dependable approach for detecting NFZ in biological fluids for practical use.

Figure 10.

Working principle and classification of molecularly imprinted electrochemical sensors[20].

-

Although MIBs have shown promising advantages in environmental pollution control, sensors, and solid-phase extraction, the potential environmental impacts in real-world applications remain largely unexplored and not well understood. Generally, the environmental risks associated with BC-based catalysts primarily arise from the potential release of toxic pollutants during their production and use in environmental remediation. These risks highlight the need for further investigation into the long-term sustainability and environmental safety of BC-based materials in practical applications[152]. Examples include the presence of toxic substances in the material during preparation, the formation of toxic intermediates, the degradability of the materials, and the material's ecotoxicity. Although MIBs are potentially environmentally friendly materials, their synthesis process, waste disposal after use, and ecological impacts still require further research and optimization. To minimize environmental problems, attention should be paid to the development of green synthesis methods, assessment of degradability and ecotoxicity, and the advancement of pollutant recycling and treatment technologies for these materials to ensure their long-term sustainability in environmental protection.

Environmental impacts of BC matrices

-

The synthesis of MIBs usually requires high-temperature pyrolysis and other chemical synthesis methods. Although BC is a low-cost and renewable material, its production process may consume significant energy, especially when high-temperature processing is required, which may lead to greenhouse gas emissions or the release of other hazardous substances[152]. During the preparation of BC, pyrolysis generates various toxic pollutants, such as aromatic hydrocarbons, aldehydes, and ketones. These substances are typically highly toxic, volatile, have low water solubility, and exhibit significant environmental mobility, making them a potential environmental concern[153,154]. Furthermore, pyrolysis can produce hazardous compounds like PAHs, which act as ligands for the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), contributing to their toxicological impact[155]. In fact, the total concentration of PAHs in BC, measured as the sum of 16 PAHs from the EPA list, can be as high as 33.7 mg/kg (dry weight)[156−158]. The pyrolysis temperature of BC ranges from 400 to 500 °C, which may lead to the maximum concentration of PAHs in BC[159].

Meanwhile, PAHs have the potential to harm the growth, reproduction, development, and immune systems of invertebrates and fish, leading to mutagenic effects[160]. Furthermore, when BC substrates are used for environmental remediation, they may release heavy metals. For instance, highly toxic substances like dioxins[161], as well as potentially harmful elements such as lead, cadmium, chromium, copper, nickel, zinc, and arsenic[162], and PAHs present in BC have been identified and may potentially be released into the environment. One study suggested that BC could suppress urease activity, which was attributed to the release of these contaminants[163].

Environmental impact of materials used in the synthesis of BC-based molecularly imprinted catalysts

-

In addition, some metal oxides or organic materials are used to prepare and modify BC-based molecularly imprinted catalysts. In particular, the modification of BC involves the use of acids/alkalies/metal oxidants, and thus these modifiers may become a source of pollution when applied in an aqueous environment[164]. Iron oxide particles, including Fe3O4 and Fe2O3, are non-toxic or low-toxic substances when magnetic BC modification is involved[165]. However, semiconducting materials used in BC-loaded photocatalyst modification, such as TiO2, CuO, and ZnO, are generally considered toxic[166,167]. The release of these metal oxides into the environment may occur, which could result in secondary pollution. For instance, TiO2 nanoparticles have been shown to have harmful effects on the health of various vertebrates, with potential damage to the human heart and reproductive system[168]. Research indicates that factors such as particle size and shape significantly influence toxicity[169]. Generally, toxicity increases as particle size decreases, with angular particles being more chemically and biologically reactive. Furthermore, small spherical particles tend to be more toxic than their rod-shaped counterparts, as they have a higher tendency to damage cell membranes[170,171]. Metal oxide nanoparticles may undergo structural alterations as a result of various environmental factors, potentially increasing their toxicity[172]. Thus, it is crucial to optimize the fabrication and modification procedures of BC to improve the stability of the material. This strategy is essential for minimizing or preventing the release of harmful pollutants into the environment[173]. In addition, the synthesis of molecularly imprinted materials typically involves functional monomers, cross-linking agents, and initiators, most of which are organic compounds with intricate functional groups. Additionally, certain functional monomers are regarded as toxic; for instance, the harmful effects of acrylic monomers, including acrylic acid and methacrylic acid, on both freshwater and marine organisms have been well established, along with acrylamide, which is classified as 'possibly carcinogenic to humans'[174]. Additionally, imprinting reactions typically occur at moderate temperatures (50–80 °C), at which MIP reagents may evaporate and be released into the air. Furthermore, after the polymerization reaction, any remaining unreacted chemicals are discarded as waste. Over time, components of the three-dimensional network in the MIP may be released due to exposure to solvents or physical impact, contributing to contamination by functional monomers. Therefore, focusing on the green synthesis of molecularly imprinted monomers is important, utilizing environmentally friendly materials and techniques[175,176] for better biocompatibility.

Toxicity and life cycle impact assessment of reaction intermediates

-