-

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a global crisis affecting human, animal, and environmental health. Widespread application and release of AMR-inducing chemicals, such as antibiotics, disinfectants, heavy metals, microplastics, and engineered nanomaterials, have created complex chemical landscapes that promote the spread of AMR[1−3]. These chemicals co-occur in clinical, agricultural, and environmental settings, creating complex exposure landscapes that promote AMR evolution and dissemination. Consequently, tackling AMR requires integrated 'One Health' approaches that combine clinical stewardship and environmental regulations on AMR-inducing chemicals[4,5].

Despite extensive research, most mechanistic studies still focus on single chemicals acting on single species, a framework that overlooks the realities of mixed exposures and diverse microbial communities. Although standardized benchmarks such as minimum selective concentrations (MSCs) and predicted no-effect concentrations (PNECs) have improved risk assessment[6,7], they do not capture the interactive and non-linear dynamics that characterize clinical application or natural environments[8]. Consequently, MSCs and PNECs measured in monocultures are often poor predictors of community-level outcomes, and single-chemical metrics fail to capture non-additive interactions that can amplify or attenuate selective pressure.

Recent research points to three interconnected insights that challenge and extend the single-chemical paradigm. First, chemical mixtures can produce synergistic or antagonistic effects on resistance selection: combinations of chemicals may select even when individual chemicals are at sub-selective concentrations, or, conversely, mask selection potential[9,10]. Second, although mixtures can be chemically complex, low-order interactions (primarily pairwise or three-way) explain most mixture outcomes, suggesting predictable patterns within complex systems[11,12]. Third, microbial diversity can buffer AMR selection, as complex communities display resilience through detoxification, competition, and altered communication networks[13,14].

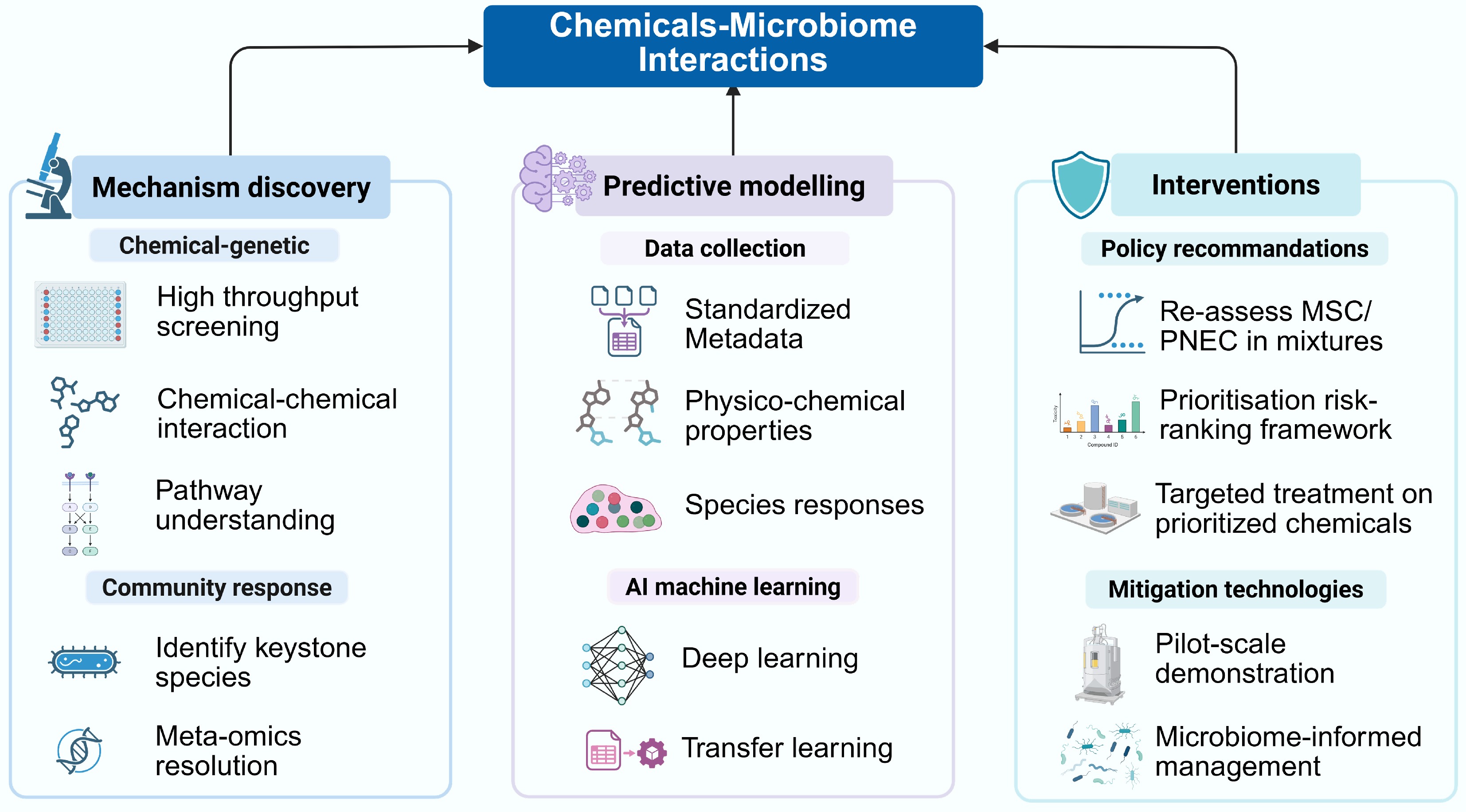

Together, these findings underscore the need to move beyond single-chemical paradigms toward a system-level understanding of how chemicals interact with microbiomes to drive AMR emergence and persistence. By discovering robust, quantitative rules linking chemical interactions, concentration regimes, and community attributes to AMR outcomes, we can train predictive models to anticipate high-risk mixtures and guide regulatory prioritisation. Translating these models into policy-ready decision-support tools, and pilot interventions (e.g., therapeutic recommendations, targeted pollutant removal, microbiome management, treatment upgrades) will allow medical sectors, regulators, and utilities to act pre-emptively rather than reactively. This perspective articulates a research roadmap from mechanistic discovery and predictive modelling to intervention strategies. Such a roadmap recommends experimental, genomic, and computational methods that can deliver actionable tools for public health, environmental management, and industry.

-

Global actions against AMR, including clinical guidelines, antibiotic stewardship, and environmental regulation, are grounded in science. Measures include, but are not limited to, European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) breakpoints and Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) breakpoints to advise antimicrobial therapy; MSC of an antimicrobial agent to provide competitive advantages for resistant bacterial strain over a susceptible strain; PNECs to estimate chemical concentrations below which adverse effects on ecosystems are unlikely to occur[15−17]. However, all current measures that follow OECD, EPA, and ISO standards adopt a reductionist approach, focusing on the response of a single bacterial species to a single chemical, which leads to several significant limitations. First, chemical co-occurrence alters selection. Interacting compounds, such as antibiotics and metals, can result in non-additive interactions (synergy/antagonism), meaning chemicals with negligible effects in isolation may combine into potent selectors or vice versa[18−20]. Second, species-specific assays ignore ecological interactions. Competition, cooperation, and spatial structuring within communities influence how resistance traits are selected and spread[21,22]. Third, AMR dynamics, especially antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) carried by mobile genetic elements (MGEs), depend on community context and MGEs' host range that are not captured in monocultures[23]. Fourth, many single-chemical MSCs and thresholds were measured under well-mixed laboratory conditions that do not reflect conditions in natural matrices (chemical gradients, nutrient limitation, sorption to solids, partitioning to microplastics, transformation to metabolites, etc.), that alter chemical bioavailability and community responses[24].

Thus, risk assessments based solely on single-chemical data may misrepresent real-world AMR risks. In clinical practice, policymaking, and environmental management, this knowledge gap creates uncertainty: which chemicals should be prioritised, what monitoring thresholds for individual chemicals are informative across different chemical mixtures, and which treatment upgrades will yield the most effective AMR-reduction benefit across different community contexts? Closing these gaps requires experiments and models that reflect the complexity of mixtures and community ecology.

-

Evidence across ecotoxicology and microbiology indicates that mixture effects are frequently non-additive. In AMR contexts, co-selective agents (i.e., heavy metals and some antibiotics) can favour AMR maintenance because metal resistance genes and ARGs are often co-located on the same MGEs, such as plasmids[25]. Moreover, under combined exposures, chemical inducers of stress responses or SOS pathways can increase both mutation rates and conjugation frequency, producing non-linear increases in AMR emergence and spread[26,27]. Physical-chemical interactions (e.g., adsorption of hydrophobic organics to microplastics or changes in partitioning in mixed solvent systems) further complicate chemical exposure for microbes[28].

To decipher the complexity of chemical mixture effects, scientists combine experimental analysis with mathematical and modelling approaches to account for interactions. Synergistic interactions can amplify the growth-inhibition effect even when individual chemicals are below their inhibitory thresholds, whereas antagonistic interactions can suppress the inhibition effect of antibiotics[9,10]. Empirical and modelling evidence indicate that low-order interactions, particularly pairwise effects, explain most mixture outcomes. These effects often arise from overlapping modes of action or co-located resistance genes on MGEs[11]. This simplifies experimental design: mapping pairwise and selected three-way combinations can identify high-impact pollutant pairs, reducing the complexity of mixture testing.

Future research should quantify interaction types and magnitudes using high-throughput screening and interpretable modelling frameworks[29,30]. Clinically, drugs that interact antagonistically with antibiotics should be avoided in co-therapy, while environmental regulations should reassess mixture-based thresholds for synergistic contaminants. Identifying dominant chemical pairs could enable targeted pollutant removal and yield disproportionate reductions in AMR selection across ecosystems.

-

Expanding from single-species studies to community-level analyses reveals that diverse microbiomes often exhibit resilience to chemical stress. As species richness increases, the minimum inhibitory concentrations for many antibiotics also rise, indicating collective protection[31,32]. Mechanisms include bioaccumulation or transformation of chemicals by tolerant taxa, biofilm-mediated refuges for sensitive populations, and competition that reduces the fitness advantage of resistant strains[33].

However, community effects are context-dependent. Communities dominated by taxa that carry conjugative plasmids or metabolize chemicals into more selective intermediates can exacerbate the propagation of AMR[34,35]. Environmental parameters such as nutrient status, redox gradients, and matrix type further influence community composition and selection outcomes[36].

Understanding these dynamics supports microbiome-informed AMR mitigation. Identifying keystone protective taxa and the traits that mediate protection opens the door to microbiome-informed management. In systems with protective taxa, strategies that preserve or strengthen those taxa through biostimulation may be cost-effective for biological AMR mitigation. In systems lacking protective taxa, supporting protective taxa through cautious bioaugmentation could be an alternative treatment option. Yet, a comprehensive understanding of how community composition modulates chemical mixture effects, along with pilot demonstrations, is essential for target monitoring and interventions[37].

-

Despite growing insights, key gaps hinder predictive understanding and translation to policy. Moving from assessing the risk of single chemicals to chemical mixtures, it remains unclear whether chemical interactions occur primarily extracellularly or through intracellular metabolic pathways[38]. If intracellular metabolic activities cause chemical interactions, what are their effects on organelle, enzyme, and metabolite molecular levels? Identifying relevant chemical features (e.g., structure, oxidation state, or functional groups) could clarify mechanistic rules. Further understanding of how synergistic and antagonistic effects accumulate in higher-level interactions might help us simplify the interactions of chemical mixtures by identifying dominant chemical interactions across combinations. In addition to chemical types/numbers, the concentration effects of chemical mixtures are also under-characterised. Shifts in bacteriostatic or bactericidal thresholds within mixtures are poorly defined, and mixture-specific MSCs have not been standardized[39]. Current research faces data fragmentation and metadata gaps. Heterogeneous experimental designs, endpoints, and incomplete metadata prevent meta-analyses and model synthesis.

From a microbial perspective, responses to the same chemicals can vary among strains, which have not been broadly assessed. Microbial strains differ in their biotransformation capacity and stress responses, yet generalizable principles linking traits to AMR outcomes remain limited[40]. Although several factors (key gene sets, resistance traits, phylogenetic relatedness, etc.) have been proposed to affect the cross-species response, a comprehensive understanding of the determining mechanism remains deficient[41]. Considering that microbes rely on metabolites and signal molecules to communicate, cataloguing microbes by their roles in chemical metabolic or signaling pathways could unify responses across microbial species/taxa to chemical exposure. Such knowledge is essential for generalizing and streamlining responses across diverse microbial species.

The structural diversity of microbial communities adds another level of consideration to their responses to chemical mixtures. Current quantitative models cannot describe how diversity, keystone taxa, and plasmid transfer rates shape AMR propagation in mixtures. For the selection of resistance strains, there is also a lack of understanding of how different microbial community structures affect their fitness and comparative advantages under chemical stress, and how each species is weighed under different community compositions. For evaluating the HGT risk under mixture exposures, the rates and triggers of plasmid transfer in structured, diverse communities also need robust quantification and improved measurement standards[42].

In general, we lack generalizable, quantitative rules to assess and predict interactions between chemicals and microbes. Current research faces data fragmentation and metadata gaps. Heterogeneous experimental designs, endpoints, and incomplete metadata prevent meta-analyses and model synthesis. Addressing these gaps requires integrated experimental, genomic, and modelling strategies, coupled with data standards and stakeholder engagement to ensure translation.

-

To close the gaps and deliver tools for regulators and utilities, a research roadmap is proposed to integrate mechanistic discovery by high-throughput experiments, predictive modelling, and technical interventions. Each step should be augmented by cross-cutting recommendations to ensure uniform data stewardship and establish a standard towards interdisciplinary implementation (Fig. 1).

The first aspect is to develop a mechanistic understanding of chemical interactions in bacteria. A recent microcosm study assessed the growth of model bacterial strains across 255 combinations of eight chemical stressors using a multi-stressor assay matrix. The assay tested the growth of 12 model and environmental bacterial strains in response to higher-order interactions among multiple stressors. Results demonstrated that growth under chemical mixtures was inconsistent among bacterial strains, indicating a strain-specific response to chemical mixtures[11]. The net responses are primarily driven by lower-order interactions among a small subset of chemicals, suggesting a limited role for complex higher-order interactions. This simplification, observed across diverse bacterial taxa, significantly enhances the predictability of microbial responses to complex pollution, streamlining efforts to model multi-stressor effects[43]. For future testing on chemicals with potential interactions on AMR spread, the selection process of chemical candidates should focus on: co-selective agents (e.g., heavy metals and antibiotics, due to co-location on MGEs), chemical inducers of stress responses or SOS pathways, and high-impact pollutant pairs identified through high-throughput screening and interpretable modeling frameworks, which will be discussed in the following section.

To further assess the responses of different bacteria to chemicals (individually or in combination), traditional chemical experiments are inefficient and require extensive laboratory work. Some bacterial species are challenging to grow in media or have long doubling times. High-throughput mixture experiments with ecological realism show great potential to overcome such limitations[30]. Using fluorescence dyes to quantify cellular stress indicators, such as reactive oxygen species or membrane permeability, allows bacterial response to chemical mixtures to be monitored within 2 h, without the prolonged cell replication cycle required by MIC testing. For example, a rapid, cost-effective optrode system using SYTO 9 and propidium iodide dyes was developed for on-site, real-time live/dead bacterial quantification. It quantified live bacteria from 108 to 106.2 bacteria/mL (potentially down to 105.7 bacteria/mL) within hours[44]. Recent advances in fluorescence-based dyes for bacterial viability detection focus on specific interactions with the cell wall, intracellular enzymes, and peptidoglycan synthesis. Various fluorescence probes can simultaneously detect the antimicrobial effects of chemicals. The validation of these advanced dyes is demonstrated across various biological models, including Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, highlighting their broad applicability[45]. These tests can also be extended to the microbial community level to assess the chemical mixture's effect on actual microbiota samples. By implementing robotics-enabled microcosm platforms, these systems show great potential in rapid, scalable evaluation of interactions across diverse chemical classes.

Following high-throughput characterization of chemical interactions, integrating genomic and metabolic pathway data (e.g., KEGG) can reveal shared or disrupted pathways that drive synergistic or antagonistic effects. Combining genomes, biological pathways, diseases, drugs, and chemical substances, KEGG pathways offer an ideal collection of pathway maps of molecular interaction, reaction, and relation networks. By mapping the affected KEGG pathways between interacting chemical pairs, we could decode the interaction modes between chemicals. For example, synergistic chemical combinations might affect substances in the same metabolic pathway, such as the TCA cycle, or key substances connecting different KEGG pathways[11]. Mapping these interactions helps predict the impacts of mixtures across taxa that share similar metabolic networks.

Understanding the response to a chemical mixture at the species level is critical for linking species and community responses. Keystone species may mediate the response of the whole microbial community, such as via bioaccumulation or biotransformation of chemicals, cross-feeding, quorum sensing, and biofilm formation[11]. Even within the same species, additional AMR traits, such as the types of ARGs and MGEs they carry, may alter their response to chemical mixtures. Those AMR traits could provide them with selective advantages or promote the spread of their MGEs[27]. Targeted experiments should consider a reductionist approach to identify keystone taxa and AMR traits that modulate mixture effects. Combining phenotypic assays with metagenomics, plasmidome reconstruction, conjugation assays, and transcriptomics can reveal stress responses and transfer dynamics[46,47]. In particular, research should focus on clinically relevant taxa and MGEs. Including panels of ESKAPE pathogens and clinically important plasmids in controlled donor–recipient assays can quantify cross-taxon transfer risk and selective effects among clinical or environmentally relevant microbiota[27].

Future research should establish standardized synthetic microbial communities composed of well-characterized model species representing key ecological and functional roles. Examples include: Escherichia coli (model conjugation strain with genome reference), Pseudomonas spp. (biofilm former; environmental and clinical model), Acinetobacter spp. (naturally competent strains with clinical relevance), Aeromonas spp. (non-virulent strain, plasmid host), Enterococcus spp. (representative Gram-positive, fecal indicator, plasmid host), Bacteroides or other anaerobes (if anaerobic workflows are possible), Nitrosomonas spp. (relevant to wastewater processes). These defined consortia can be used to systematically test single and mixed chemical exposures under controlled, reproducible conditions. Standardized protocols for cultivation, chemical dosing, and meta-omic analyses, along with unified metadata reporting, will enable quantitative comparisons across laboratories. To identify keystone species and functional guilds mediating mixture responses, addition and removal experiments will be performed using the aforementioned model species as reference species to prepare a standard mixed community. Community-wide responses to chemical exposure will be monitored by adding or removing reference species to determine keystone species. Findings from the controlled microcosm will be extended to mixed communities and will generate important parameters for further modelling at the ecosystem level.

Machine learning models can integrate the aforementioned chemical properties, microbial traits, and environmental conditions to forecast AMR risk. To predict chemical interactions, microbial growth, or plasmid transfer kinetics, mechanistic insights such as chemical degradation kinetics and key rationale (chemical backbone, functional groups, and physico-chemical parameters) can be combined with machine learning to generate interpretable models that capture chemical interactions while retaining mechanistic insight. One recent study pioneers antibiotic discovery by using a deep neural network model trained on 2,335 molecules, and then screening against > 10 million compounds. This machine learning approach led to the discovery of Halicin, a structurally unique, broad-spectrum compound that treats pan-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections in mice. Furthermore, testing 23 predicted candidates yielded eight new antibacterials, including two that overcome multiple resistance mechanisms in E. coli. This validates the power of combining computation and empirical methods to predict chemicals with antibiotic properties[48]. To ensure future models inform AMR risk assessment by predicting chemical/chemical interactions with antibiotic-like properties, active learning will guide targeted validation experiments. These will test machine-learning-derived hypotheses in controlled microcosms, verifying whether predicted drivers (e.g., redox-active compounds or stress-tolerant taxa) indeed govern AMR emergence. Experimental validation is essential to close the loop between computation and wet-lab research. Validated predictors will be scaled through transfer learning using field datasets from wastewater and soil microbiomes. Model transparency and uncertainty will be quantified to support regulatory adoption.

To guide technology and policy translation, standardized datasets should underpin risk-ranking systems to identify priority chemical combinations based on selection potential and persistence. Firstly, the MSCs and PNECs of chemicals with various combinations should be determined using standardized protocols from organizations such as the CLSI or the EUCAST. Those tests should ensure consistent use of specific parameters, including inoculum size, growth media, incubation conditions, and viability assessment methods like colony counting or time-kill curves. When testing, chemical interactions, defined media formulation, and rigorous quality control measures should be carefully controlled to ensure accurate and comparable results. Based on the risk of AMR selection potential, exposure limits, persistence, and sensitivities across species, a risk-ranking system can be established to guide monitoring and regulation of prioritized chemical combinations[49]. Moreover, it is essential to evaluate the efficiency of both existing and emerging treatment processes, such as adsorption, advanced oxidation, membrane filtration, and constructed wetlands, specifically in removing prioritized chemical combinations. When necessary, targeted or tailored treatment steps should be developed. Additionally, microbiome-informed mitigation strategies, including biostimulation and controlled bioaugmentation, should be tested in clinical and pilot-scale systems, supported by genomic and economic analyses[50]. Close collaboration with clinical settings, utility providers, and agricultural managers is essential during technology translation for testing interventions in clinical or pilot-scale environments. This approach pairs genomic and ecological monitoring with economic analyses to quantify co-benefits and trade-offs.

-

Addressing the spread of AMR requires a step change: moving from isolated single-chemical, single-species studies to integrated programmes that combine high-throughput, ecologically realistic experiments, high-resolution genomics, and interpretable machine learning models. Focusing on low-order interactions, dominant pollutants, and protective community structures offers leverage points for policy and engineering solutions. Through data standardization, transparent modelling, and interdisciplinary collaboration, the scientific community can deliver decision-support tools and interventions to reduce AMR emergence at its environmental origins. Achieving this will protect ecosystems, reduce clinical AMR risk, and offer regulators and utilities cost-effective strategies to manage chemical complexity in an era of accelerating anthropogenic impacts.

-

The author confirms sole responsibility for the following: study conception and design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

This work was funded by the Australian Research Council for funding support through the DECRA project (DE240100842) awarded to Dr Lu.

-

The author declares that there is no conflict of interests.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Lu J. 2025. Chemicals–microbiome interactions and antimicrobial resistance: a roadmap for prediction and interventions. Biocontaminant 1: e009 doi: 10.48130/biocontam-0025-0010

Chemicals–microbiome interactions and antimicrobial resistance: a roadmap for prediction and interventions

- Received: 15 October 2025

- Revised: 07 November 2025

- Accepted: 13 November 2025

- Published online: 26 November 2025

Abstract: Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a growing global threat to human, animal, and environmental health. Effective mitigation requires evidence-based regulation of chemicals that promote resistance. However, most current studies and risk assessments focus on single chemicals acting on single bacterial strains, overlooking the complexity of real-world chemical mixtures and microbiomes. Emerging evidence indicates that chemical mixtures can exert synergistic or antagonistic effects on AMR selection and that microbial community diversity often buffers resistance propagation. This perspective outlines a roadmap for integrating chemical–microbiome interaction research with predictive and intervention frameworks. This perspective synthesizes these insights and outlines a research agenda built on: (1) mechanistic discovery to uncover how chemical mixtures interact and drive AMR emergence and mobility; (2) predictive modelling that links high-throughput data and literature to forecast AMR outcomes across taxa and matrices; and (3) translation into interventions by including risk prioritization, microbiome-based mitigation, and regulatory strategies. Together, these approaches can generate actionable tools for public health agencies, regulators, and water utilities to manage AMR risk.