-

Viruses, which are pathogens that specifically infect cells to replicate, pose a profound and ongoing threat to global health[1]. Their pathogenesis typically involves viral entry into host cells, replication using cellular machinery, and subsequent cell lysis or dysfunction, which triggers immune responses that can lead to extensive tissue damage and clinical disease[2]. The consequences of such infections are severe, ranging from widespread morbidity and mortality to large-scale social and economic disruption[3]. Notable outbreaks in the 21st century, such as the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic[4], the 2014 Ebola epidemic in West Africa[5], and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2[6], have demonstrated this devastating impact. These events have resulted in significant loss of human life, placed extreme strain on healthcare infrastructure, and brought global economic activity to a near standstill through travel restrictions, lockdown policies, and disrupted supply chains, crippling vital sectors including tourism, manufacturing, and services[7].

In the fight against viral pathogens, the core strategies employed include vaccination to build pre-exposure immunity[8], the use of antiviral drugs for treatment[9], and the implementation of non-pharmaceutical public health interventions[10]. The effectiveness of all these strategies is fundamentally reliant on a robust and responsive foundation of viral detection, which is the critical first step that enables the timely identification and isolation of cases, guides targeted therapeutic interventions, facilitates effective contact tracing, and provides essential data for surveillance and informed public health decision-making[11]. The current arsenal of detection methods, however, carries significant limitations. Viral culture, historically the gold standard for isolation, is time-consuming, requires specific biosafety conditions, and depends on skilled interpretation of cytopathic effects[12]. Immunoassays, including ELISA and rapid antigen tests, provide faster results but are often challenged by lower sensitivity, leading to false negatives, potential cross-reactivity affecting specificity, and high reagent costs[13]. Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs), such as quantitative PCR (qPCR) and reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR), offer high sensitivity and specificity and can quantify viral load. Still, they require sophisticated laboratory infrastructure, trained personnel, have a longer turnaround time, and carry a high risk of amplicon contamination[14]. Consequently, the critical gaps and compromises inherent in existing viral analytical technologies highlight the urgent necessity to develop and deploy novel detection platforms that are faster, more sensitive, cost-effective, and portable for future pandemic preparedness and response.

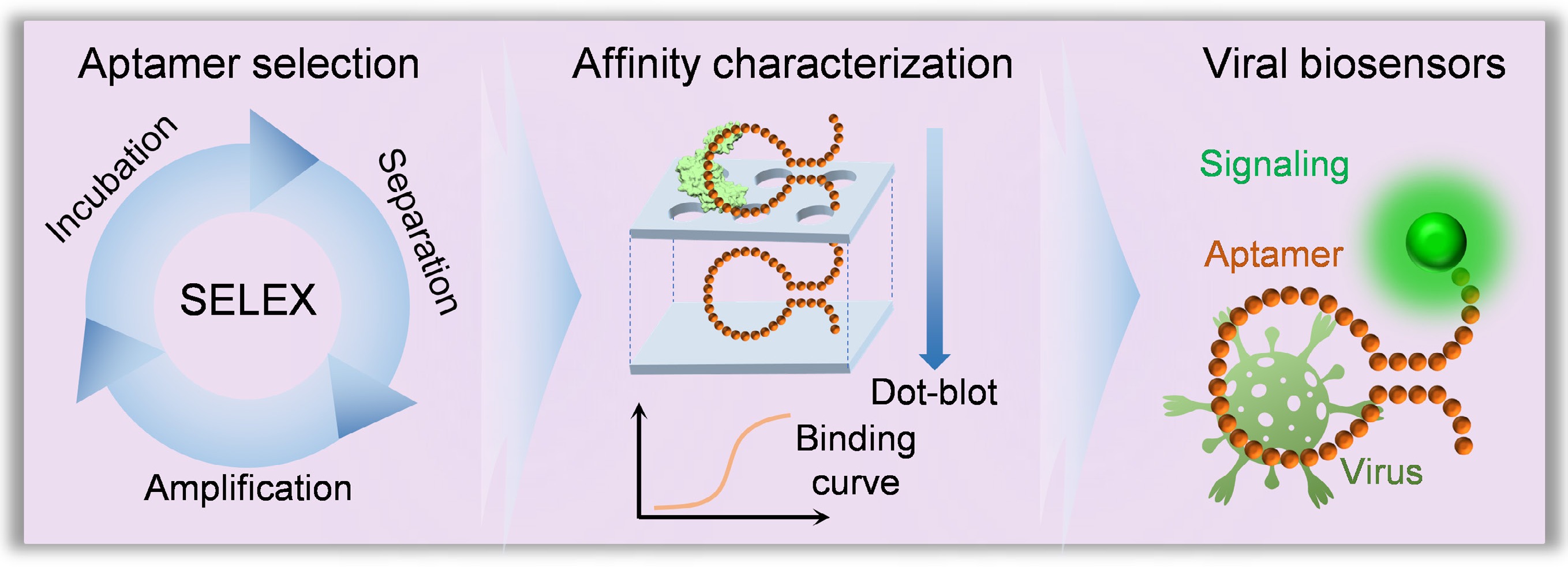

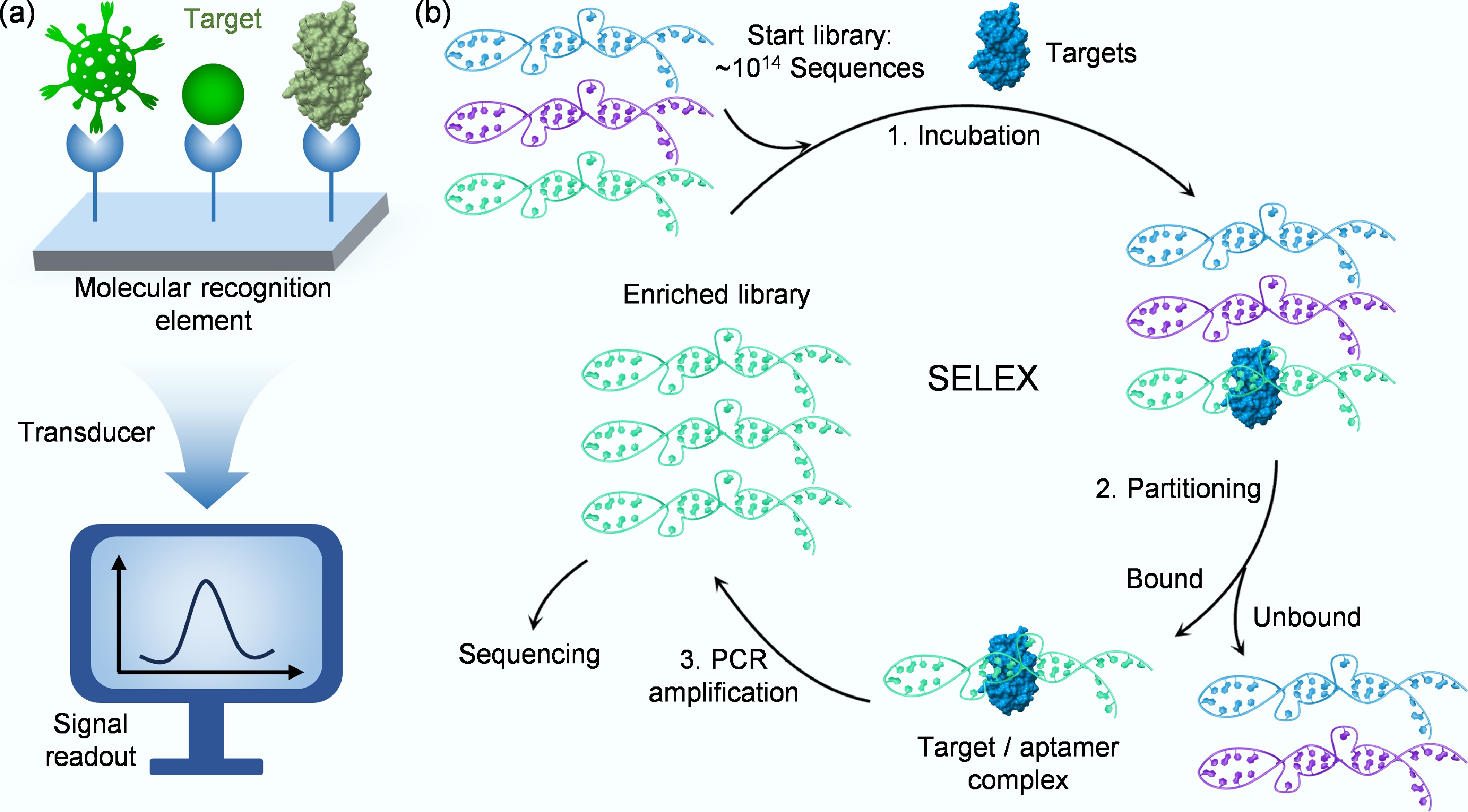

A biosensor is a self-contained analytical device that integrates a biological recognition element with a transducer to provide quantitative or semi-quantitative information about target analytes[15,16]. Compared with traditional detection technologies, the core advantage of biosensors lies in their ability to deliver rapid, specific, and sensitive detection, making them invaluable across diverse fields, including clinical diagnostics, food safety monitoring, and environmental surveillance[17]. According to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) definition[18], a biosensor converts a biological response into an electrically quantifiable signal through three essential components: the molecular recognition element, the signal transducer, and the signal processing/readout system (Fig. 1a)[19]. The molecular recognition elements, including antibodies and enzymes, serve as the fundamental component that determines the biosensor's specificity[18]. Aptamers, often termed 'chemical antibodies', are single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides selected in vitro through systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX)[20]. While antibodies offer high specificity through immunological binding, they face limitations in stability, production consistency, and flexibility for modification[21]. It is important to note that recent developments in nanoantibodies and engineered thermostable proteins have made significant strides in overcoming these stability limitations, offering promising alternatives[22]. Enzymes provide catalytic amplification but often lack the broad target range needed for detection applications[23]. In contrast, aptamers have emerged as superior alternatives, offering comparable affinity to antibodies, enhanced thermal stability, and design versatility[24]. Furthermore, aptamers demonstrate exceptional chemical stability under various conditions, reversible binding capacity for biosensor regeneration, and straightforward chemical synthesis with site-specific modifications for biosensor integration[25]. These unique characteristics position aptamers as ideal recognition elements for developing next-generation biosensors, particularly for rapid and highly sensitive virus detection. Their combination of molecular specificity, structural stability, and engineering flexibility enables the creation of robust viral detection platforms that address emerging viral threats by improving detection performance and operational practicality.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic of a biosensor's key components for detecting target analytes. (b) Schematic illustration of the key steps in SELEX.

In response to the pressing need for advanced viral detection platforms, this review systematically summarizes the latest advancements in the development and application of aptamer-based biosensors for virus monitoring. It provides a comprehensive analysis of key technologies for screening virus-specific aptamers, followed by a detailed examination of various signal transduction mechanisms employed in biosensor design. By critically evaluating both the maturation of aptamer selection techniques and their implementation in biosensing architectures, this work aims to establish a clear conceptual framework that helps researchers understand current developments, address existing challenges, and identify future directions in this rapidly evolving field. Through this organized synthesis of knowledge, the review seeks to facilitate the rational design of next-generation detection tools that combine high sensitivity, specificity, and practicality for effective viral threat management.

-

The development of any aptamer-based detection platform is predicated on the initial isolation of high-affinity, specific aptamers. This process, known as in vitro selection, systematically sifts through vast combinatorial libraries of nucleic acids to identify rare sequences that bind a desired viral target with high specificity. The following sections detail the critical stages of this pipeline, beginning with the foundational principles of the selection methodology, the strategic preparation of viral targets, the application of advanced techniques to overcome key challenges, and culminating in the essential validation of the selected candidates. A thorough understanding of each step is crucial for the successful development of effective aptamer-based biosensors against viral pathogens.

Fundamentals of SELEX

-

SELEX represents a revolutionary in vitro methodology for selecting specific aptamers against diverse target molecules. First established independently by Ellington & Szostak in 1990[20], this technique leverages the fundamental principles of molecular evolution to isolate high-affinity binders from vast random oligonucleotide libraries containing up to 1015 unique sequences. The SELEX process operates through an iterative cycle of target incubation, bound-sequence separation, and PCR amplification (Fig. 1b)[26], systematically filtering nucleic acid populations to identify rare sequences with optimal binding characteristics. The technical workflow begins with library design, where a central randomized region flanked by fixed primer sequences provides both structural diversity and amplification capability[27]. The fixed primer-binding regions must be optimized to minimize primer-dimer formation during PCR and to prevent internal base-pairing that could otherwise constrain the folding of the aptamer's random region[28]. Through repeated selection rounds, the initial heterogeneous pool becomes progressively enriched with target-specific aptamers. Each cycle employs increasingly stringent conditions to favor the strongest binders, while advanced techniques like emulsion PCR help maintain sequence diversity by minimizing amplification biases[29]. Typically requiring eight to 15 cycles, the process culminates in a dramatically enriched library where high-affinity sequences dominate, ready for sequencing and characterization[30].

The strategic advantages of SELEX are substantial. As a completely in vitro process, it bypasses biological systems, allowing the development of aptamers against toxins, non-immunogenic targets, and molecules incompatible with traditional antibody production. The resulting aptamers demonstrate remarkable stability, minimal batch-to-batch variation, and straightforward chemical modification capabilities[31]. These characteristics have established SELEX as a cornerstone technology in molecular recognition, with selected aptamers finding extensive applications in biosensing platforms, diagnostic assays, targeted therapeutics, and environmental monitoring systems[32]. The methodology continues to evolve through numerous modified protocols, expanding its utility across basic research, clinical diagnostics, and biotechnology development.

Target considerations for viral aptamer selection

-

While understanding the core SELEX workflow is essential, the success of any selection experiment is profoundly influenced by the nature and preparation of the target itself. In viral detection, the choice of target is a foundational decision that dictates the sensitivity, specificity, and practical applicability of the analytical method. The two primary targets are specific viral proteins and whole viral particles. Targeting specific viral proteins is a cornerstone of point-of-care testing (POCT). This strategy offers high specificity and controllability, as these proteins can be safely produced in vitro, eliminating the need to handle live viruses. Furthermore, protein-based assays are highly amenable to standardization and large-scale production, making them ideal for the development of rapid detection kits. This is exemplified by aptamers selected against influenza hemagglutinins (H5N1 and H7N7), as well as by aptamer-based biosensors developed for targets such as the SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain (RBD) and the S1 protein[33]. Cennamo et al. used the RBD of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein as the SELEX target to develop an optical aptamer biosensor (Fig. 2a)[33]. They immobilized a specific DNA aptamer onto a polyethylene glycol-modified gold nanofilm on a D-shaped plastic optical fiber and detected binding through surface plasmon resonance. The aptamer biosensor showed precise and selective recognition of the spike protein over non-target proteins and maintained specificity in diluted human serum.

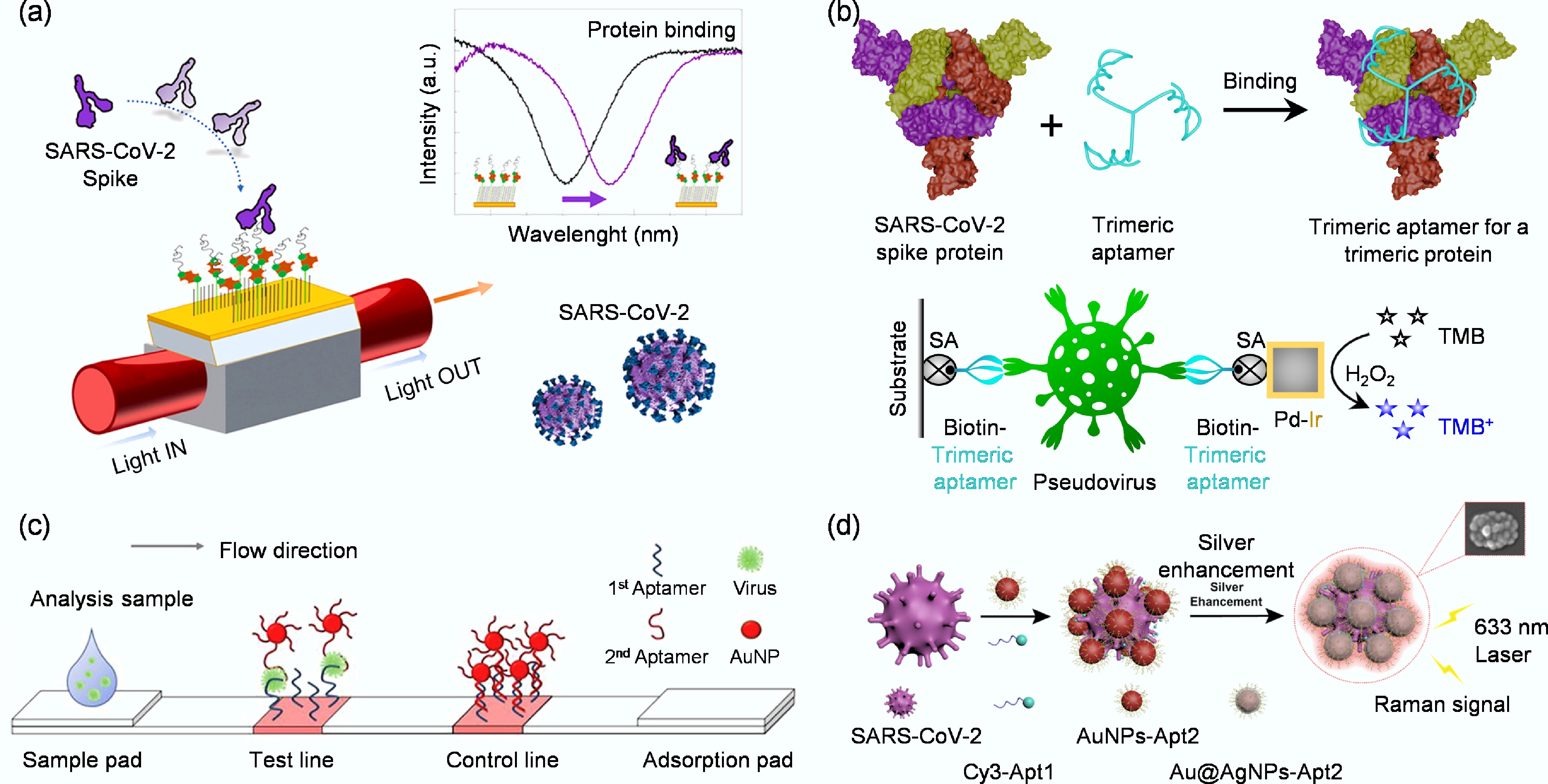

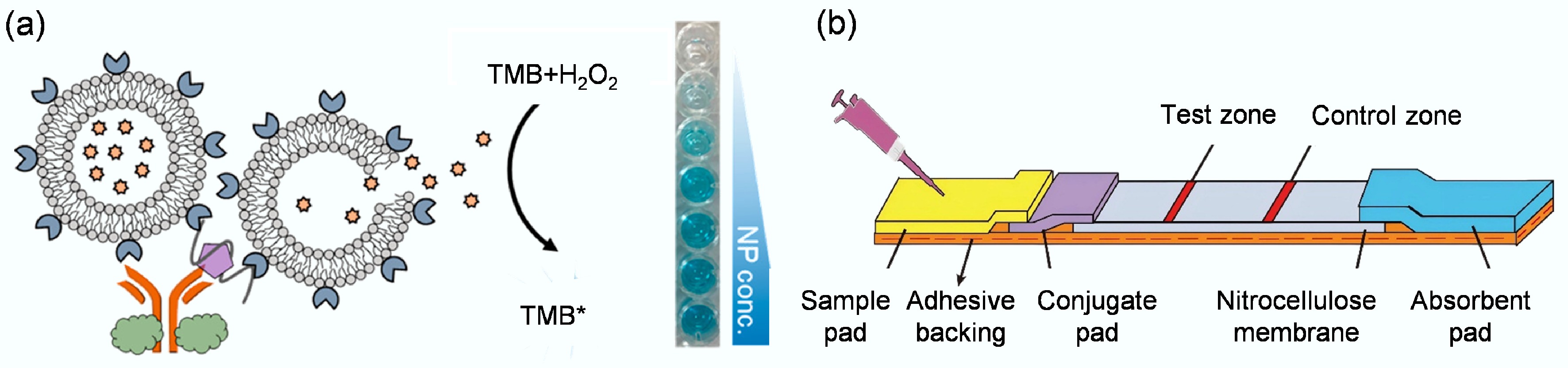

Figure 2.

(a) Schematic representation of a highly specific and sensitive SARS-CoV-2 spike protein biosensor[33]. (b) Design of an enzyme-linked aptamer binding assay for colorimetric detection of SARS-CoV-2 using trimeric aptamer TMSA52[34]. (c) Diagram of the whole virus particle detection system using a cognate pair of aptamer-based lateral flow strip[35]. (d) Schematic diagram of SERS aptamer biosensor for SARS-CoV-2 detection by assembling hotspots via S proteins on the surface of SARS-CoV-2[36].

Li et al. constructed a trimeric aptamer, TMSA52, based on a SELEX-derived monomeric aptamer (MSA52) that binds the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (Fig. 2b)[34]. They linked three identical MSA52 units through a trebler phosphoramidite and a flexible thymine spacer to create a branched structure complementary to the trimeric symmetry of the viral spike. The trimeric aptamer enabled a colorimetric sandwich assay that captured and detected pseudotyped SARS-CoV-2 particles with high affinity and specificity. These results demonstrate that the spike glycoprotein serves as an effective SELEX target and that structural matching between the trimeric viral protein and TMSA52 significantly enhances molecular recognition and detection sensitivity. However, this protein-centric approach faces significant limitations. The in vitro expressed protein may not perfectly mimic its native conformation on the virus, potentially reducing detection efficiency. More critically, the high mutation rate of viral proteins can lead to changes in epitopes, resulting in reduced sensitivity or false negatives during rapidly evolving outbreaks[37,38]. Finally, a single protein cannot fully capture the structural complexity of an entire virus, potentially missing valuable analytical information[39]. To mitigate these issues, the protein-based strategy can be enhanced by employing multi-epitope targeting[40], multiplexed aptamer panels[41], and continuously updated aptamer libraries to keep pace with viral evolution[42]. These refinements aim to bolster robustness while preserving the scalability of protein-based detection.

As a complementary strategy, targeting whole viral particles for aptamer selection addresses several limitations of the protein-based approach. By presenting a multitude of epitopes in their native conformations, intact viruses enable the selection of aptamers that recognize a broader range of structural features[43]. This often confers some resilience against mutations, as aptamers may bind to conserved regions across viral variants[44]. Successful examples include aptamers that selected against whole avian influenza H5N2 and H5Nx viruses, which exhibit broad or cross-reactive binding[35]. In this study, Kim et al. employed whole H5N2 viral particles as targets to establish a sandwich-type lateral flow biosensor based on a cognate aptamer pair (Fig. 2c)[35]. The test line on the nitrocellulose membrane was coated with the biotinylated capture aptamer J3APT via a streptavidin linkage, while the reporter aptamer JH4APT was conjugated to 13 nm gold nanoparticles to generate a visible signal. During the assay, the sample containing whole H5N2 particles first migrated along the strip and was captured by immobilized J3APT. The bound virions then interacted with the flowing AuNP–JH4APT conjugates, forming a sandwich complex that produced a red band on the test line, visually confirming the presence of viral particles. A poly(A) sequence served as the control line to validate proper flow. This configuration enabled direct recognition of native virus particles without prior disassembly or antigen purification, demonstrating a simple yet effective platform for whole-virus detection. By directly using intact virus rather than isolated proteins, their approach preserved the native surface epitopes and enabled the aptamers to recognize the virus in its authentic structural context.

In addition, Song et al. used intact SARS-CoV-2 particles as SELEX targets to develop a surface-enhanced Raman scattering aptamer biosensor for direct virus detection on solid surfaces (Fig. 2d)[36]. They designed two aptamers: one carrying a Raman dye and the other linked to gold and silver nanoparticles, which specifically bound to spike proteins on the viral surface and induced the assembly of nanoparticles into plasmonic hotspots. This configuration allowed rapid, sensitive in situ detection of intact viral particles without complex sampling. The aptamer-guided assembly on the virus surface produced strong Raman signals, confirming that complete virus particles can serve as effective SELEX targets for optical biosensing. Nevertheless, the whole-virus approach introduces its own set of challenges. It often requires higher biosafety containment, complicates sample preparation, and raises the risk of cross-reactivity with structurally similar viruses. The production of standardized, intact viral materials for routine testing is also more complex. To overcome these hurdles, researchers are developing safer alternatives, such as pseudotyped viruses, and employing rigorous counter-selection methods during SELEX to minimize cross-reactivity[45]. Ultimately, the most potent solution may lie in a hybrid approach that strategically combines whole-virus selection for broad recognition with protein-based detection for precise and scalable assay development.

In summary, target selection in viral detection is not a binary choice but a strategic spectrum. The protein-based approach prioritizes precision and manufacturability, while the whole-virus strategy emphasizes comprehensiveness and resilience. The future of robust viral detection likely rests on intelligent designs that integrate the strengths of both paradigms to create assays that are both highly accurate and adaptable to viral evolution.

Advanced SELEX methodologies for viruses

-

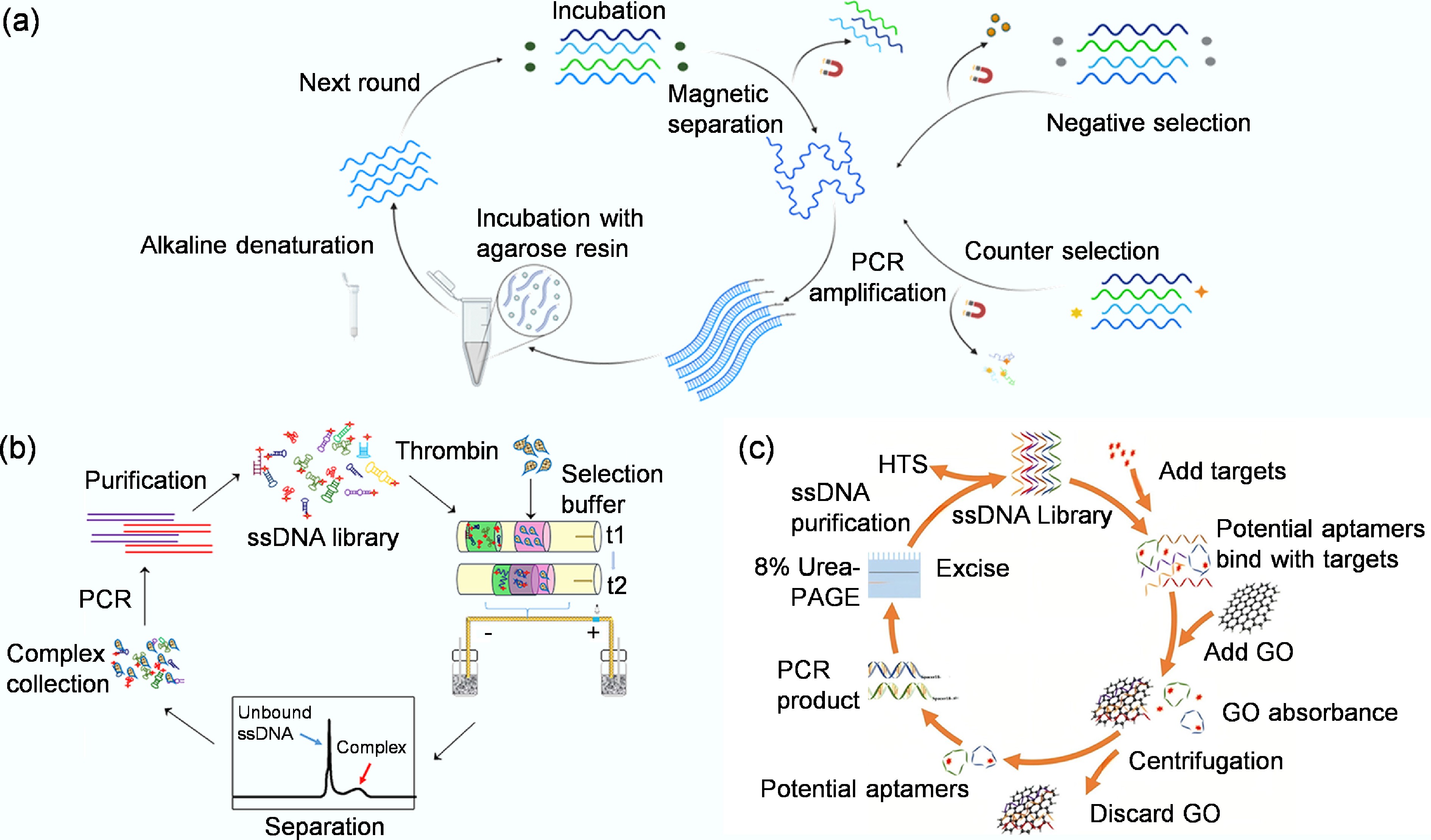

Given the complex and diverse nature of viral targets, the standard SELEX process has been extensively refined with advanced methodologies to enhance efficiency and the functional properties of the resulting aptamers. Following the strategic selection of an appropriate target, the next critical phase in aptamer development is choosing a SELEX methodology. The classical SELEX process has been refined into numerous advanced techniques to improve the efficiency and success of aptamer selection against diverse targets, including viruses. This section reviews three prominent SELEX variants particularly relevant to viral aptamer screening: magnetic bead-based SELEX (MB-SELEX), capillary electrophoresis SELEX (CE-SELEX), and graphene oxide SELEX (GO-SELEX), highlighting their core principles and illustrative applications.

MB-SELEX leverages the convenience of magnetic separation. In this method, target molecules, such as viral proteins or inactivated whole virions, are immobilized onto magnetic beads. Following incubation with the oligonucleotide library, a magnetic field is applied to rapidly separate the bead-bound sequences from the unbound fraction (Fig. 3a)[46]. This allows for efficient washing and subsequent elution of specific binders for PCR amplification. A key advantage of this approach is its ability to preserve the native conformation of the target, which is crucial for selecting aptamers with high functional affinity. Furthermore, specificity can be enhanced by introducing negative selection steps against non-target molecules[47]. For instance, Shrikrishna et al. employed MB-SELEX for aptamer selection, in which His-tagged SARS-CoV-2 RBD proteins were immobilized on Nickel-Nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) magnetic beads as the target[48]. A random single-stranded DNA library was incubated with these RBD-coated beads, allowing specific sequences to bind while unbound DNA was removed by washing. The bound sequences were eluted and PCR-amplified to generate new single-stranded DNA pools for subsequent rounds. To improve specificity, counter-selections were performed with bare Ni-NTA beads to eliminate nonspecific binders. After several rounds of selection and enrichment, high-affinity aptamers specifically recognizing the viral RBD were identified and validated for sensitive SARS-CoV-2 detection in clinical samples. Xi et al. used MB-SELEX by immobilizing hepatitis B surface antigen on carboxylated magnetic nanoparticles, allowing rapid magnetic separation during selection[49]. After multiple rounds, they obtained high-affinity aptamers that specifically bound the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and built a chemiluminescent aptamer biosensor with high sensitivity for hepatitis B detection.

CE-SELEX introduces a high-resolution separation mechanism based on electrophoretic mobility. This technique capitalizes on the fact that aptamer-target complexes migrate differently from free oligonucleotides under an electric field within a capillary. This physical separation eliminates the need for immobilization and traditional elution, significantly reducing kinetic bias by directly isolating the tightest-binding complexes. The process involves incubating the library with the target, injecting the mixture into a capillary, and collecting the distinct peak corresponding to the complexes for amplification[53]. Zhu et al. developed an online reaction-based single-step capillary electrophoresis SELEX (ssCE-SELEX) system for rapid and efficient aptamer selection (Fig. 3b)[51]. In this approach, human thrombin served as the model target, and ssDNA, together with the protein, was sequentially injected into a capillary, where they mixed, reacted, and formed complexes in situ under an applied electric field. The entire workflow integrated the key stages of mixture, incubation, reaction, separation, detection, and collection within a single continuous run. The collected complex fraction was amplified by PCR to produce enriched ssDNA pools for subsequent selection. This streamlined ssCE-SELEX procedure markedly enhanced binding affinity and specificity compared with conventional multi-step SELEX, providing a rapid, low-consumption, and high-resolution platform for aptamer screening. In addition, Martínez-Roque et al. demonstrated the power of this approach by combining CE-SELEX with next-generation sequencing to identify high-affinity DNA aptamers against the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein[54]. A randomized single-stranded DNA library was incubated with purified spike protein, and bound complexes were separated from free DNA inside a capillary based on their electrophoretic mobility. The collected complexes were amplified and subjected to further selection with lower protein concentrations to increase stringency. This approach efficiently enriched high-affinity sequences, and two aptamers, C7 and C9, showing nanomolar affinity and high specificity, were obtained and later used in sensitive fluorescent and electrochemical virus detection assays.

GO-SELEX utilizes the unique adsorption properties of graphene oxide (GO). Single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules are strongly adsorbed onto GO sheets via π-π stacking and hydrophobic interactions. In GO-SELEX, the oligonucleotide library is incubated with the target and then exposed to GO (Fig. 3c)[52]. Unbound or weakly bound sequences are captured by the GO, while aptamers that have formed stable complexes with the target are shielded and remain free in solution[55]. These complexes are then easily collected from the supernatant for amplification. This method offers a simple and efficient solution-phase separation. Kim et al. successfully applied GO-SELEX to select aptamer pairs for the whole H5N2 avian influenza virus[35]. The random DNA library was adsorbed onto graphene oxide, and only target-binding sequences were released upon viral addition due to conformational changes. After several rounds of counter-selection against other subtypes, two aptamers, J3APT and JH4APT, binding to different viral sites were identified and confirmed by Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) and SPR. These aptamers were then used to construct a sandwich-type lateral flow biosensor that specifically detected the H5N2 virus with high sensitivity and selectivity.

In summary, the development of advanced SELEX methodologies has been pivotal in addressing the unique challenges inherent in selecting aptamers against viral targets. Techniques such as MB-SELEX, CE-SELEX, and GO-SELEX have significantly accelerated the selection process by enhancing the efficiency of partitioning bound sequences from unbound sequences. Collectively, these sophisticated approaches have substantially improved the success rate, efficiency, and functional utility of aptamer selection, paving the way for the development of more robust and reliable aptamer-based viral detection platforms.

Aptamer affinity characterization

-

Following successful SELEX using these advanced methodologies and the sequencing of enriched DNA libraries, individual aptamer candidates must be rigorously characterized to validate their binding affinity and guide subsequent optimization, such as truncation analysis to identify the minimal functional sequence. This process involves a comprehensive evaluation of affinity, specificity, kinetics, and structural stability, which is critical for assessing their practical utility[55]. The binding affinity, most commonly quantified by the equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd), is a fundamental parameter reflecting the strength of the aptamer-target interaction. Several analytical techniques are employed for this purpose, including dot-blot assay, flow cytometry, SPR, and biolayer interferometry (BLI).

Firstly, the dot-blot assay provides a cost-effective approach for rapid estimation of aptamer binding affinity. In this method, labeled aptamers (typically with radioactive or fluorescent tags) are incubated with target molecules, then filtered through nitrocellulose and nylon membranes[56]. The fundamental separation mechanism relies on differential binding properties: nitrocellulose membranes retain target-bound aptamers through physical adsorption of proteins, while nylon membranes capture unbound aptamers via electrostatic interactions. After the washing steps, the signal intensity of the resulting dot on nitrocellulose directly correlates with the amount of bound aptamer. By testing against a dilution series of target proteins, researchers can generate binding curves to estimate apparent Kd. For example, Li et al. used a dot-blot assay to measure the binding affinities of aptamers MSA1 and MSA5 toward the SARS-CoV-2 S1 protein[57], in which 32P-labeled aptamers were incubated with the target and the bound fractions visualized on nitrocellulose membranes (Fig. 4a). Although dot-blot assay cannot provide kinetic parameters, its operational simplicity, low cost, and capacity for parallel processing make it particularly valuable for aptamer identification and sequence truncation analysis.

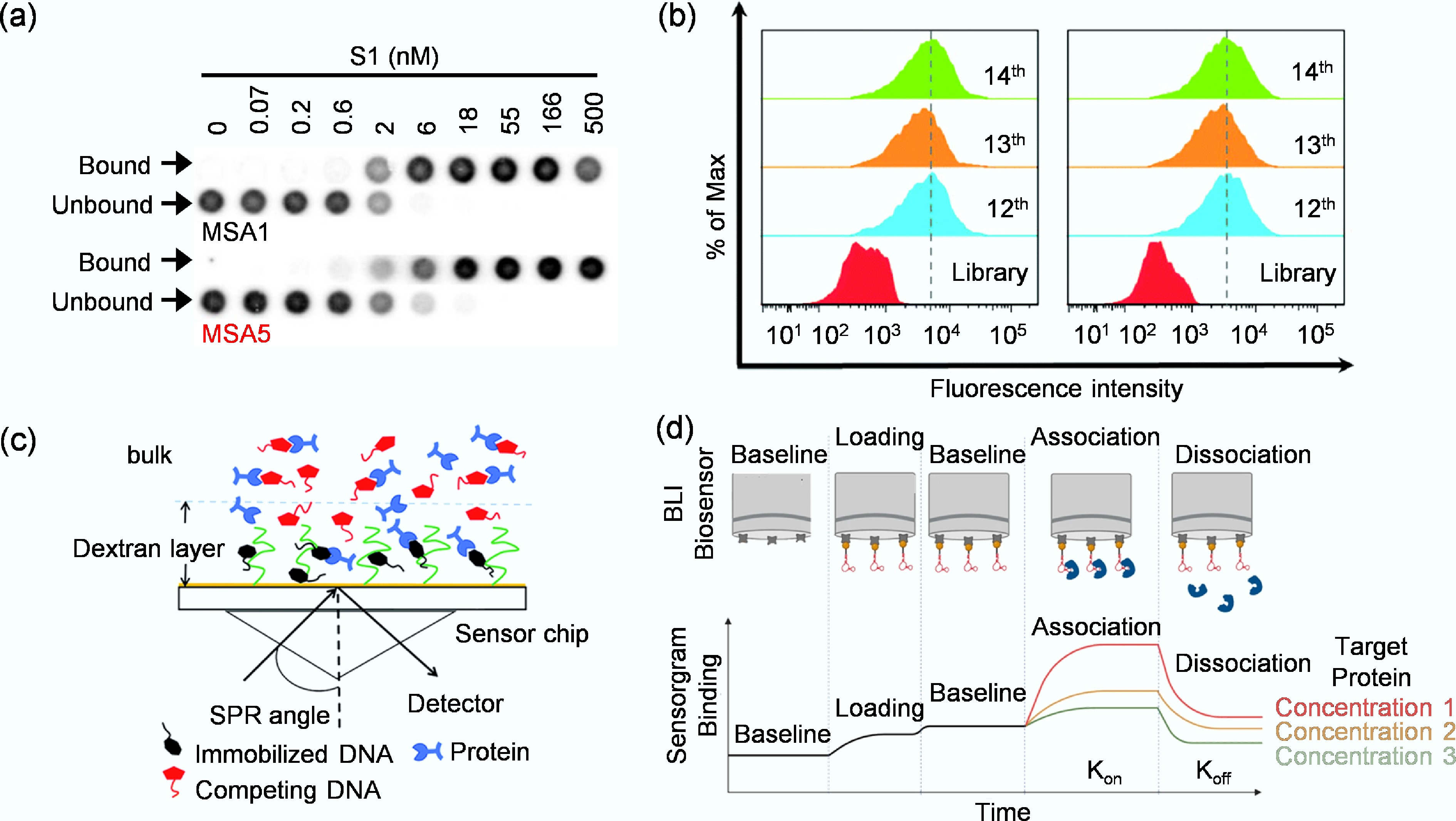

Figure 4.

(a) Assessment of binding affinity of MSA1 and MSA5 to the SARS-CoV-2 S1 protein by dot blot assay[57]. (b) Monitoring the binding ability of the enriched libraries to target KYSE150 cells and control KYSE30 cells by flow cytometry[59]. (c) Working principle of SPR for target binding analysis[60]. (d) The binding of a target protein to an immobilized aptamer ligand induces a change in the interference pattern[61].

Secondly, flow cytometry provides a powerful approach for characterizing aptamer affinity against targets presented on intact particles, such as magnetic beads or agarose beads. In this method, target-conjugated particles are incubated with a fluorescently labeled aptamer[58]. The mixture is then passed through a flow cytometer, where individual particles are analyzed for fluorescence intensity. By measuring the mean fluorescence intensity across a range of aptamer concentrations, a binding curve can be constructed and the Kd value calculated. For instance, Chen et al. employed flow cytometry to monitor the enrichment of aptamer libraries during the cell-SELEX process and to determine binding affinities of the selected aptamers toward Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma (ESCC) cells (Fig. 4b)[59]. Flow cytometry is particularly valuable for its ability to assess binding in complex mixtures and evaluate aptamer performance under physiologically relevant conditions.

Thirdly, as a label-free technique, SPR provides high-sensitivity, real-time analysis of biomolecular interactions[62]. The principle relies on detecting changes in the refractive index at a biosensor chip surface (Fig. 4c)[60], typically coated with a thin gold film. For characterization, either the target molecule or the aptamer is immobilized on the biosensor chip, while the complementary partner in solution is flowed over it. The binding event is recorded in real-time as a biosensorgram, from which the association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rate constants are derived. The equilibrium dissociation constant is then calculated as Kd = koff/kon. The label-free nature and dynamic data provided by SPR make it a cornerstone for evaluating aptamer interactions with diverse targets, from viral proteins to whole virus particles[63]. For example, Lu et al. used SPR to determine the affinity of ssDNA aptamers selected against the hemagglutinin (HA) protein of influenza B virus[64]. The HA protein was immobilized on a biosensor chip, and candidate aptamers were passed through the detection channels at varying concentrations. Among the five sequences tested, aptamer A573 showed the strongest and most stable binding signal, indicating the highest affinity for the target protein. The SPR results confirmed a specific and robust interaction between A573 and influenza B HA, establishing it as a promising recognition element for sensitive virus detection.

Finally, BLI is another powerful, label-free technology that operates on optical interferometry. It measures the shift in the interference pattern of white light reflected from a biosensor tip[65]. When a target immobilized on the tip binds aptamers in solution, the increase in optical thickness causes a wavelength shift, which is monitored in real time. Similar to SPR, this generates kinetic data for calculating kon, koff, and Kd[65]. Compared to SPR, BLI is often more straightforward to operate because it does not require a complex microfluidic system and allows high-throughput, parallel analysis, making it exceptionally suitable for rapid affinity ranking of numerous aptamer candidates. Uppal et al., for example, characterized the binding affinity of three DNA aptamers (tNSP1, tNSP2, and tNSP3) toward the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid (N) protein using BLI[61]. As illustrated in Fig. 4d, a biotinylated aptamer was immobilized on a streptavidin-coated biosensor, which was then dipped into serial dilutions of the N protein solution to monitor real-time association and dissociation events. The BLI sensorgram reflected the dynamic change in optical interference caused by target binding, allowing precise determination of kinetic parameters. Through this method, the authors obtained Kd in the low-nanomolar range, demonstrating potent and specific aptamer–protein interactions. This BLI-based approach provided quantitative affinity data and revealed fast association and slow dissociation rates, underscoring the suitability of BLI for real-time evaluation of aptamer binding kinetics.

In summary, the choice of characterization method depends on the required throughput, precision, and available resources. Dot-blot offers a cost-effective approach, flow cytometry excels at analyzing binding in complex mixtures, while SPR and BLI provide complementary, high-fidelity platforms for detailed kinetic profiling. Looking ahead, integrating these technologies with microfluidics and computational analysis will further accelerate the development of high-performance aptamers for viral detection and therapeutics.

-

Aptamer-based biosensors employ structure-specific aptamers to recognize targets such as ions, molecules, proteins, viruses, or cells[66]. Following target binding, the biometric event is converted into a measurable signal through various transduction mechanisms. These biosensors are primarily categorized by their readout method, with electrochemical, fluorescent, colorimetric, SPR, and SERS being the most common. Table 1 summarizes the affinity characteristics of selected aptamers and the performance of their corresponding biosensors for viral detection.

Table 1. Summary of aptamer affinity and biosensor performance for viral detection

Virus Target Detection method Aptamer name Kd LDR LOD Detection time HIV HIV-p24 Electrochemical[67] − − 0.93–93 μg/mL 51.7 pg/mL 30–60 min Zika Zika SF9 envelope protein Electrochemical[68] Zika–aptamer − − 2.4 × 107 Viruses 7.45 min YFV NS1 protein Electrochemical[69] YFV-37 aptamer 119.88 ± 27.93 nM − 2.366 pM 3 h HAdV HAdV-2 (VR-846) Electrochemical[70] HAdV-Seq4 0.9 ± 0.1 nM − 1 pfu/mL 30 min HNV (GII. 2) NoV VLP Electrochemical[71] APTL-1 148.13 ± 6.53 nM 1 ng/mL–

10 μg/mL0.28 ng/mL 30 min MNV (GII. 3) Capsid protein Electrochemical[72] AG3 − 20–120 aM 10 aM or 180 virus particles 60 min HPV-16 HPV-16 L1 Electrochemical[73] HPV-16 L1 aptamer − 0.2–2 ng/mL 0.1 ng/mL or

1.75 pM− HPV-16 HPV-16 E7 proteins Electrochemical[74] Sc5-c3 − − 100 pg/mL or

1.75 nM− WNV WNV envelope proteins Electrochemical (ACEF)[75] Tr-WNV aptamers 63.94 ± 11.05 nM − 1.06 pM 10 min DENV Virus envelope protein Electrochemical

(ACEF)[76]Isol-7 aptamer 261.1 ± 12.9 nM − 76.7 fM 10 min SARS-CoV-2 Pseudotyped SARS- CoV-2 virus Electrochemical[70] SARS2-AR10 − − 1 × 104 copies/mL 30 min SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein Electrochemical

(EIS)[77]DSA1N5 0.12 ± 0.02 nM − 1,000 VP/mL 5 min SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein Electrochemical[78] CoV2-RBD-1C 5.8 nM 0.5–8 μg/mL 72 ng/mL 70 min SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid protein Fluorescence[79] NP-A48, NP-A58 − 10 fg–1.0 ng 5.87 pg 30 min H5N1 Magnetic MIPs Fluorescence[10] ZGO-H5N1 Apt − − 0.0128 HAU/mL 15 min SMV (GII. 2) Capsid proteins Fluorescence[80] Aptamers 25 232 nM 1–5 µg/mL 1 log10 RNA copies per 3 g lettuce 15 min HBV e antigen Fluorescence[81] − − 42–420 nM 26.5 nM

(609 ng/mL)2 min HBV HDs Fluorescence[82] sLet-1, sLet-2 − − 0.0009 μM 4 min HPV-16 HPV-16 L1 Fluorescence[83] S4 10−99 nM 10−1−104 ng/mL 0.1 ng/mL > 240 min SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid protein Fluorescence

(PIFE)[84]PCL-Apto3 − 1–40 nM 0.05 ng/μL 1–2 min SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein Fluorescence

(NSET)[85]CoV2-RBD-4C 19.9 nM 10–500 virus/mL 130 fg/mL (antigen), 8 particles/mL (virus) 10 min HBV Surface antigen Fluorescence[49] H01, H02, H03 − 1–200 ng/mL 0.1 ng/mL − ASFV p30 Colorimetric[86] Atc-20 140 ± 10 pM − 0.61 ng/mL − BVDV Glycoprotein E2 Colorimetric[87] Apt 31 − − 0.27 copies/mL 15–20 min SFTS virus Nucleocapsid protein Colorimetric[88] SFTS-apt3 0.8 ± 0.2 μM − 0.009 ng/mL 60 min SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein Colorimetric[89] MBA5SA1 0.12 nM − − 30 min SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein Colorimetric[90] TMSA52 8.8–23.7 pM − 3.2 × 103 cp/mL 60 min SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein Colorimetric[91] TMSA5 6.8–14.8 pM − 4 ×105 cp/mL 30 min H5N2 Virus particles Colorimetric[35] JAPT, JHAPT − − 2.09 × 105 EID50/mL 20 min HIV HIV-1 gp120 Colorimetric[92] HD2, HD3, HD4, HD5 − 1–1,000 ng/mL 8.0 ± 1.2 ng/mL 5–10 min HIV HIV-1 gp120 Colorimetric[93] B40t77 RNA aptamer − 0.1–8 μg/mL 0.2 μg/mL 60 min HIV HIV-I Tat Colorimetric[94] − 120 pM 1.0–500 nM 1 pM (1.5 pg/mL) − Influenza B Nucleoprotein Colorimetric[95] INFA-apt4 77.6–125.7 nM 1–105 pg/mL 0.16 pg/mL − ASPV Coat proteins (PSA-H, MT32) SPR[96] − 55, 8 nM − − − SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein SPR[66] CoV2-RBD-1C 5.8 nM − 36.7 nM 10 min H5N1 HA SPR[97] − 4.65 nM 0.128–1.28 HAU − 1.5 h Noroviruses

(GII. 4)VP1 SPR[98] Aptamer I−IV − 70–200 aM 70 aM > 60 min SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein SERS[36] Apt1-Cy3

Au@AgNPs-Apt2− − 5.26 TCID50/mL 10 min H1N1 HA SERS[99] V46, V57 19.2, 29.6 nM 1–106 PFU/mL 0.62 HAU/mL − H1N1 A/H1N1 target SERS[100] Cy3-labeled aptamers − − 97 PFU/mL 20 min H1N1 HA SERS[101] RHA0385 2–5 nM − 2 × 105 VP/mL 15 min LDR: Linear Detection Range; LOD: Limit Of Detection; ASFV: African Swine Fever Virus; BVDV: Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus; SFTS: Severe Fever With Thrombocytopenia Syndrome; H5N1: Avian Influenza Virus H5N1; HA: Hemagglutinin; HAU: Hemagglutination Units; ASPV: Apple Stem Pitting Virus; BPMV: Bean Pod Mottle Virus; HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus; Tat: Trans-Activator of Transcription; WNV: West Nile Virus; ACEF: Alternating Current Electrothermal Flow; NSET: Nanoparticle Surface Energy Transfer; PIFE: Protein-Induced Fluorescence Enhancement; EIS: Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy; FRET: Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer; DENV: Dengue Virus; YFV: Yellow Fever Virus; PBS: Phosphate-Buffered Saline; HAdV: Human Adenovirus; H5N2: Avian Influenza Virus H5N2; LFD: Lateral Flow Devices; H1N1: Influenza A H1N1 virus; SERS: Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering; HBV: Hepatitis B Viruses; HDs: HBV DNA segment complementary sequences; HNV: Human Norovirus; MNV: Murine Norovirus; SMV: Snow Mountain Virus; '−' indicates data not available. Electrochemical detection

-

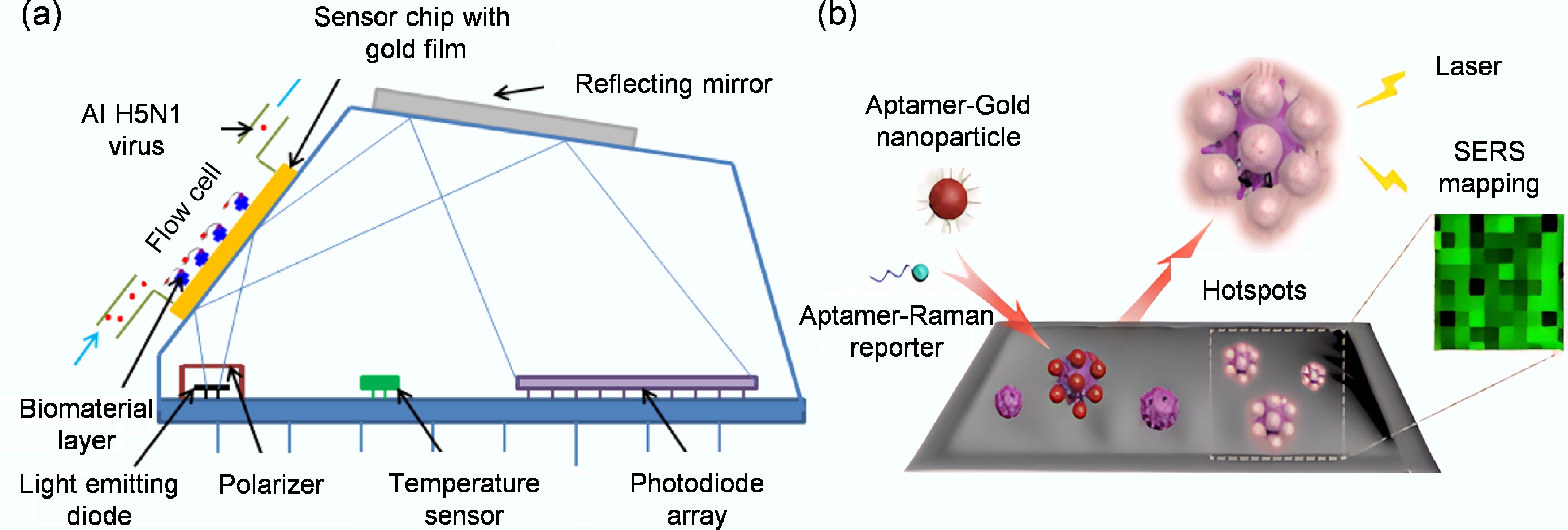

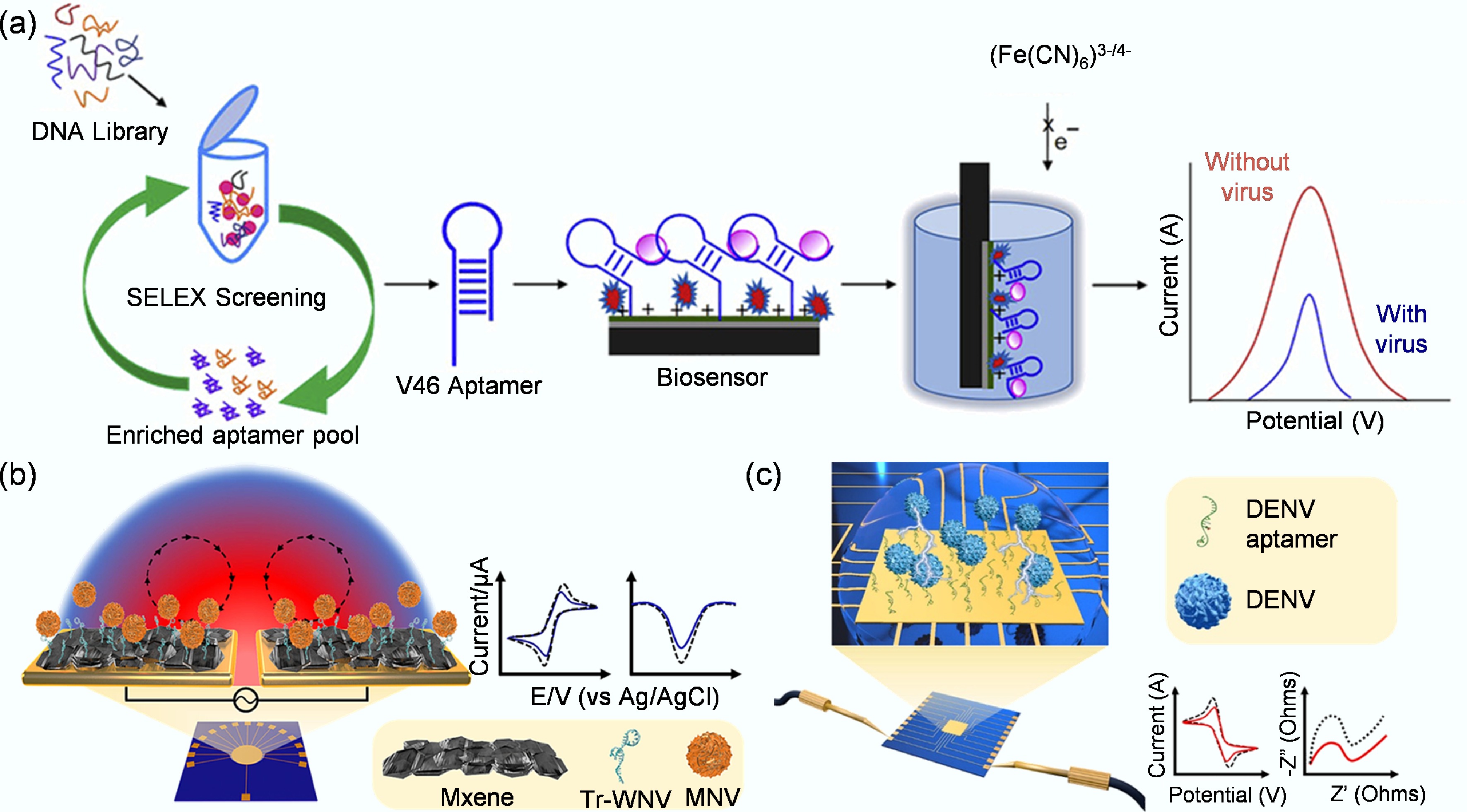

Electrochemical biosensors detect viruses by measuring changes in electrical parameters that occur when the aptamer binds to the viral target[102]. These parameters include current (amperometry and voltammetry methods), potential (potentiometry method), or impedance (impedance method)[103]. Among them, the amperometry and voltammetry methods measure the current generated by the interaction between aptamers and targets. The difference is that amperometry measures the current over time at a fixed voltage[104]. Lubin et al. used the current signal generated by the binding of the Tat protein to a methyl blue-labeled aptamer immobilized on a gold electrode to achieve highly sensitive and specific detection of HIV Tat protein, with a detection limit at the nanomolar level[105]. Voltammetry measures changes in current over a variable voltage range. Jyoti Bhardwaj et al. adopted a label-free electrochemical aptamer biosensor with Indium Tin Oxide (ITO) electrode[99], used high-affinity DNA aptamer V46 as the recognition element, and monitored the surface current changes of the electrode by differential pulse voltammetry, which successfully achieved highly sensitive and specific detection of various H1N1 virus subtypes (Fig. 5a). The results showed a low detection limit of 3.7 PFU/mL (Plaque Forming Unit per milliliter), and could effectively distinguish H1N1 from other influenza virus subtypes.

Figure 5.

(a) Label-free electrochemical aptamer biosensor based on differential pulsed voltammetry for the detection of H1N1 virus[99]. (b) Schematic representation of a rapid electrochemical biosensor for West Nile virus detection, featuring an MXene/Tr-WNV aptamer complex and fabricated by ACEF technology[75]. (c) Schematic representation of a biosensor for rapid electrochemical dengue virus detection by ACEF technology[76].

Park et al. used a label-free electrochemical biosensor based on a truncated aptamer and MXene heterojunction to achieve ultra-sensitive and rapid detection of West Nile Virus (WNV) by alternating current electrothermal flow (ACEF) technology, with a detection limit as low as 1.06 pM in 10% human serum (Fig. 5b)[75]. Potentiometric aptamer sensors measure the voltage difference between two electrodes. It is widely used because of its ease of operation, portability, and low cost[102]. Subhashish Dolai's study used a paper-based potentiometric aptamer biosensor to detect intact Zika virus by measuring changes in open-circuit potential upon virus binding to the immobilized aptamer, with a sensitivity of up to 0.26 nV/virus and a detection limit of 2.4 × 107 viruses, and can directly drive the liquid-crystal display (LCD) screen for reading[68].

Finally, the impedance aptamer biosensor characterizes the interaction between the aptamer and the target by the changes in the electrical conductivity and capacitance of the electrode surface, that is, changes in conductivity[104]. This aptamer biosensor is widely used due to its simple preparation method, rapid detection process, and high sensitivity. It has been applied to detect various targets ranging from small molecules[106], proteins[107], to live viruses[108]. Park et al. used an electrochemical impedance aptamer biosensor based on gold crossbar micro-gap electrodes and ACEF technology[76]. By screening and truncating the specific aptamer for dengue virus, high-sensitivity detection of the virus envelope protein and spiked samples was achieved within 10 min, with a detection limit of 76.7 fM (Fig. 5c). Kwon et al. used an electrochemical biosensor composed of a truncated DNA aptamer/MXene hetero-layer to specifically detect the NS1 protein of yellow fever virus (YFV)[69]. The limit of detection (LOD) of this biosensor in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was 2.757 pM, and the detection limit in 10% human serum was 2.366 pM. Zhang et al. employed a high-affinity dimeric DNA aptamer (called DSA1N5) as a molecular recognition element. They used electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) as a signal transduction method to detect SARS-CoV-2 virus by measuring the change in charge transfer resistance (ΔRct/Rct) without pretreatment of saliva samples[77]. The sensor achieves a low detection limit (1,000 virus particles/mL) in untreated saliva, a detection time of less than 10 min, a clinical sensitivity of 80.5%, and a specificity of 100%. It can effectively detect wild-type, Alpha, and Delta variants and is the first reported rapid antigen test for emerging variants. The aptamer-based biosensor developed by Zhang et al. effectively bridges the critical gap between laboratory RT-PCR and rapid antigen tests for SARS-CoV-2 detection[77]. While RT-PCR offers high sensitivity, its reliance on centralized labs and long processing times hinders rapid deployment, with turnaround times of 5 to 10 d and results reported within 12 to 48 h[109]. Conversely, commercial rapid antigen tests, though fast, have poor sensitivity in saliva (2%–23%) and require nasopharyngeal swabs collected by professionals, limiting their use in asymptomatic screening[110]. The sensor developed by Zhang et al. overcomes these limitations by combining the non-invasive convenience of saliva sampling with a 10 min detection time, while achieving 100% specificity and 80.5% sensitivity, which significantly outperforms existing saliva-compatible tests[77]. This hybrid approach positions the platform as a robust tool for decentralized and home-based screening. Overall, electrochemical aptamer biosensors play a crucial role in promoting the development of biosensing technology due to their high sensitivity, strong stability, low detection limit, high specificity, and real-time detection capabilities[104].

Unlike the above methods, Peinetti et al. developed a DNA aptamer-based solid-state nanopore sensor[70]. This biosensor detects by measuring the change in the rectification efficiency of the ionic current resulting from the binding of the virus to an aptamer immobilized on the inner wall of the nanopore. The biosensor provides ultrasensitive, label-free, and direct detection of intact viral particles without sample pretreatment. The detection limit is as low as 1 pfu/mL for human adenovirus and 1 × 104 copies/mL for SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus. More importantly, the biosensor can effectively distinguish infectious viruses from non-infectious viruses inactivated by chlorine or ultraviolet light. The biosensor has been successfully validated in complex samples, including real water samples, serum, and saliva, and its quantitative results are highly consistent with gold-standard methods, such as plaque assays. It is a tip branch in electrochemical biosensors.

Fluorescent detection

-

Fluorescent aptamer biosensors are among the most prevalent sensing techniques due to their ease of implementation and the facile conjugation of fluorescent tags to aptamers[103]. Their operation typically relies on detecting changes in fluorescence intensity, caused by aptamer-target binding, which are quantified using fluorescence spectroscopy. A common 'molecular beacon' design involves a fluorophore and a quencher paired on a single aptamer. In the absence of the target, the aptamer's flexible structure brings the fluorophore and quencher into proximity, suppressing the fluorescence signal. Upon target binding, a conformational change in the aptamer separates the pair, restoring fluorescence and generating a detectable signal[111]. For instance, leveraging this 'molecular beacon' principle, Escudero-Abarca et al. developed aptamers against the norovirus capsid protein[80]. This approach enabled precise detection and discrimination between different virus strains without complex sample preparation, providing a powerful tool for food safety monitoring. An alternative design utilizes two fluorophores in a FRET pair. Huang et al., combining colorimetric and fluorescence dual-detection modes, developed a dual-mode RNA cleavage aptamer biosensor (Fig. 6a)[112]. The biosensor uses two RNA fragments (Tat Apt 01-FAM and Tat Apt 02) to assemble into a ternary complex in the presence of the target HIV Tat peptide and to induce aggregation of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) via thioflavin T (ThT). At the same time, the fluorescence signal was quenched and recovered by FRET. The linear range of the biosensor was 2–60 nM (detection limit of 1.47 nM) in colorimetric mode, 0.5–25 nM (detection limit of 0.28 nM) in fluorescence mode, and the recovery rate in serum was 96.0%–104.7%, showing high selectivity, stability, and reliability. It provides a low-cost, high-precision tool for early HIV detection.

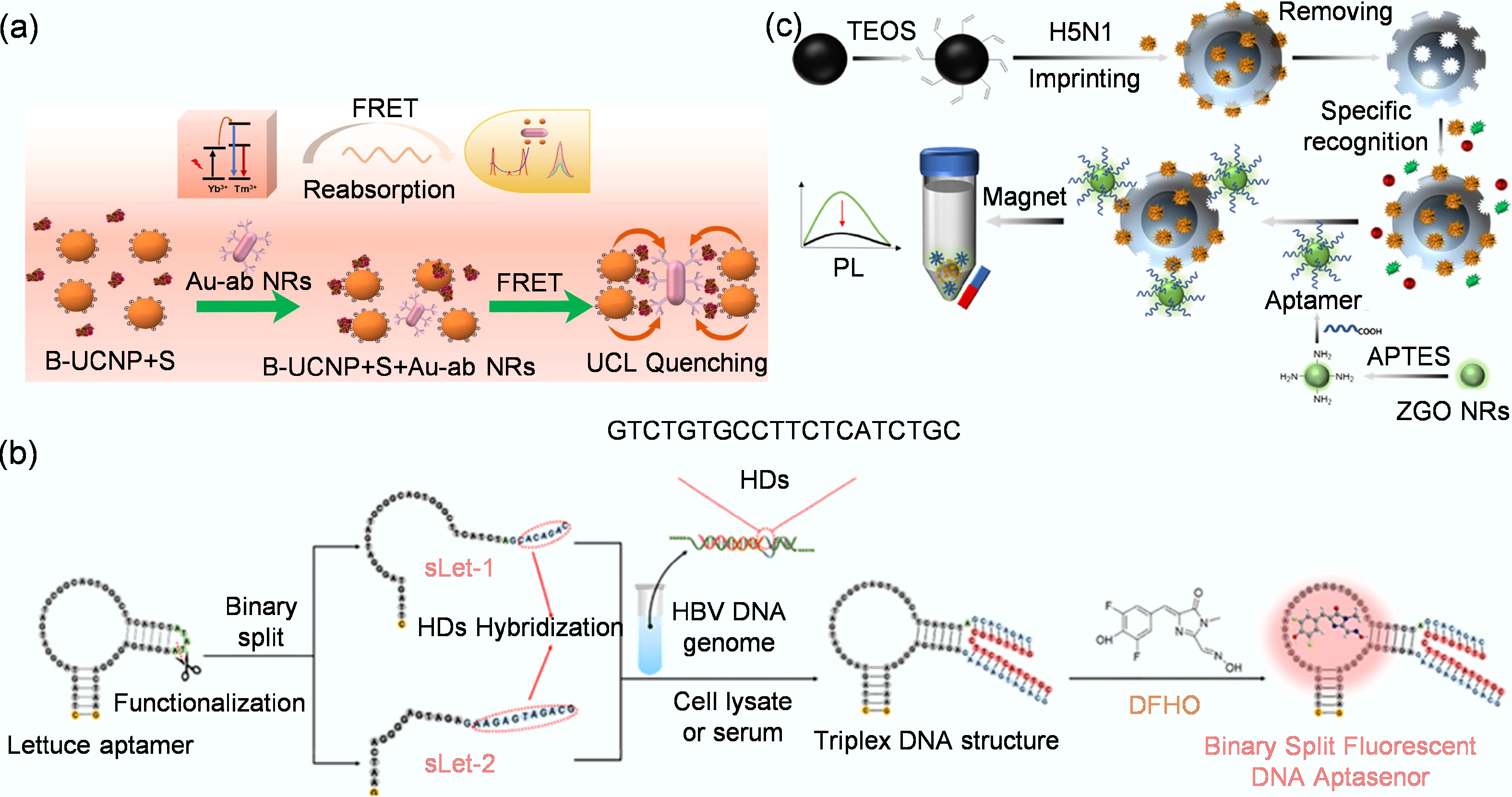

Figure 6.

(a) Detection system that utilizes the FRET effect to achieve highly sensitive, rapid, quantitative, and on-site detection of the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2[114]. (b) Schematic diagram for detecting HBV DNA fragments using the bifurcated fluorescent DNA aptamer biosensor[82]. (c) The preparation of MIP-aptamer biosensor for H5N1 detection[113].

Fluorescent aptamer biosensors leverage the versatility of optical signaling and the high specificity of aptamers, allowing the development of assays with high sensitivity, low detection limits, and real-time capabilities. A key advantage is the adaptability of fluorescence readouts, which can be integrated with a diverse array of aptamer configurations. This design flexibility is exemplified by several innovative approaches. For instance, Zhang et al. developed a label-free and enzyme-free biosensor using a split lettuce DNA aptamer[82]. In this system, the aptamer segments reassemble upon hybridization with Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) DNA targets, restoring fluorescence to achieve rapid and highly sensitive detection with a detection limit of 0.9 nM, while also effectively distinguishing between mutant strains (Fig. 6b). In another configuration aimed at overcoming autofluorescence in complex samples, Chen et al. created a biosensor based on the dual recognition of persistent luminescent nanoparticles and a molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP)-aptamer[113]. This sandwich-structured MIP-aptamer biosensor recognizes the H5N1 virus, achieving a highly sensitive detection limit of 0.0128 HAU/mL (Hemagglutinating Unit per milliliter) with excellent selectivity in serum (Fig. 6c). Despite their significant advantages in sensitivity and cost-effectiveness, fluorescence-based aptamer biosensors are not without limitations. Their performance can be compromised by challenges such as background fluorescence interference and matrix effects in complex biological samples[102].

Colorimetric detection

-

Colorimetric aptamer biosensors function by generating a measurable change in color or absorbance upon the binding of an aptamer to its target[115]. This signal transduction is commonly achieved using materials such as AuNPs, horseradish peroxidase (HRP), and nanozymes with peroxidase-mimicking activity[116]. These biosensors are particularly valued for their low cost, operational simplicity, and ease of visual interpretation of results. AuNPs serve as excellent colorimetric reporters due to their unique optical properties. Their surface plasmon resonance confers a strong visible color that shifts from red to blue upon aggregation, enabling detection at nanomolar to picomolar concentrations[117]. Furthermore, the surface of AuNPs can be easily functionalized, enhancing their adaptability. For example, Parisa et al. combined AuNPs with a G-quadruplex aptamer to develop a biosensor that rapidly and highly sensitively detects bovine viral diarrhea virus, with a limit of detection of 0.27 copies/mL[87], demonstrating high precision and accuracy in real samples.

An alternative, highly sensitive approach uses peroxidase-based enzymatic amplification. HRP is widely employed for its ability to catalyze the oxidation of chromogenic substrates such as tetramethylbenzidine (TMB), 2,2'-Azinobis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic Acid) (ABTS), and o-phenylenediamine (OPD) in the presence of hydrogen peroxide, producing a strong color change[118]. This principle was leveraged by Yeom et al., who identified DNA aptamers (SFTS-apt1, SFTS-apt2, SFTS-apt3) that specifically bind the nucleocapsid protein of the severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS) virus[88]. He then constructed a highly sensitive detection platform based on the aptamers and RPA70A (human replication protein A 70 kDa)-conjugated liposomes. This biosensor achieved ultra-sensitive detection of the target nucleocapsid protein (with a detection limit as low as 0.009 ng/mL), and demonstrated excellent specificity and accuracy in human serum (Fig. 7a). To further enhance performance, nanozymes with high peroxidase-mimicking activity can be integrated. Tan et al. developed a dual-aptamer biosensor with a core design focused on constructing an efficient catalytic signal-amplification system[119]. The key detection step is that Au@Pt NPs, as a highly efficient nanoenzyme, possess excellent peroxidase activity and can catalyze the reaction between hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and the chromogenic substrate TMB, generating blue oxidized TMB (oxTMB), which has a characteristic absorption peak at 652 nm. What is particularly important is that this biosensor also incorporates metal-organic framework MIL-53 as a co-catalyst. When the enriched sandwich complex is mixed with MIL-53, Au@Pt NPs, and MIL-53, the system forms a synergistic catalytic system that significantly accelerates the TMB-H2O2 chromogenic reaction, thereby converting a weak protein-binding signal into a strong, measurable color signal. This ingenious 'dual aptamer + dual catalyst' (Au@Pt NPs and MIL-53) design strategy not only ensures high specificity of the detection through the sandwich structure, but also achieves extremely high signal amplification efficiency through the synergistic catalytic effect of the nanoenzyme and metal-organic framework (MOF), ultimately achieving ultra-sensitive detection of 8.33 pg/mL of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein. This work demonstrates the great potential of combining multifunctional nanomaterials with aptamers in the development of a next-generation highly sensitive color-based biosensor[119].

Figure 7.

(a) Depiction of a colorimetric biosensor designed to target the nucleocapsid protein of the severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus[88]. (b) Aptamer-based LFD that integrates strand-displacement amplification with a gold nanoparticle probe for highly sensitive detection of Siniperca chuatsi iridovirus[120].

In addition, Wang et al. developed a colorimetric enzyme-linked aptamer sorbent assay[89]. The core of the biosensor is to combine a high-affinity DNA aptamer (MBASSA1) as a recognition element with a Pd-Ir nanocube nanoenzyme with peroxidase-like activity to produce a color change by catalyzing the oxidation of the TMB substrate. The aptamer biosensor successfully detected the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant in clinical saliva samples, with a sensitivity of 86.5% and a specificity of 100%. The results show that the biosensor performance is comparable to that of expensive commercial detection kits, demonstrating that a single high-affinity aptamer can achieve highly sensitive detection without the need to build more complex multivalent aptamers. Chang et al. combined the powerful signal amplification capability of rolling circle amplification with the simplicity of the urease-mediated litmus test, achieving detection of the target substance by monitoring the color change caused by pH variations[90]. In testing 77 clinical saliva samples, this biosensor achieved 83.8% sensitivity for SARS-CoV-2 and 100% specificity, demonstrating excellent potential for clinical viral detection. Liu et al. developed a colorimetric sandwich-type biosensor, AUT, that uses two functionalized ligands[91]. When viruses are present, a 'magnetic bead - virus - urease' complex is formed. Urease catalyzes the hydrolysis of urea, increasing pH and causing a visible color change (from yellow to pink) with the phenol red indicator, enabling non-invasive visual detection. The trimeric ligand biosensor has the highest affinity (Kd ≈ 6.8–14.8 pM), with a sensitivity of 70.8% in clinical samples (specificity 100%), significantly superior to the dimeric (62.5%) and monomeric (50%) versions. It can also detect samples with low viral loads (Ct value ≤ 25). The study also established a sensitivity-affinity mathematical model, predicting that a Kd of ≤ 0.51 pM is required to achieve 80% sensitivity, highlighting the crucial role of high-affinity ligands in precise viral detection.

Unlike the electrochemical approach of Zhang et al.[77], the colorimetric biosensors by Wang et al.[89], Chang et al.[90], and Liu et al[91]. prioritize ultimate simplicity and accessibility, positioning them as superior alternatives to standard rapid antigen tests without the technical demands of PCR[109]. While rapid antigen tests are simple, their poor performance with saliva and reliance on nasal swabs are significant limitations[110]. These colorimetric biosensors directly overcome these flaws. They retain the crucial advantage of a visual, instrument-free readout familiar from antigen tests, but achieve dramatically higher reliability with saliva. For instance, the assay by Wang et al.[89] (86.5% sensitivity) and the assay by Chang et al.[90] (83.8% sensitivity) significantly surpass the 2%–23% sensitivity of antigen tests in saliva[110]. Furthermore, the work by Liu et al. provides a critical engineering insight, demonstrating that systematically optimizing ligand affinity (from monomer to trimer) directly enhances clinical sensitivity[91], a principled design strategy not typically employed in conventional lateral flow test development. Thus, these platforms deliver PCR-level specificity (100%) with the naked-eye simplicity of an antigen test, making them ideally suited for truly decentralized, low-resource settings where even portable electronic readers are impractical.

Despite their advantages, conventional colorimetric assays can be limited by lengthy procedures and operational complexity. To address this need, lateral flow devices (LFDs) provide an ideal platform for POCT, enabling the rapid visual readout of optical signals. For instance, Zhang et al. developed an aptamer-based LFD that integrates strand displacement amplification (SDA) with a gold nanoparticle probe for the highly sensitive detection of Siniperca chuatsi iridovirus (Fig. 7b)[120]. This sensor employed a pair of high-affinity aptamers to form an aptamer-target-aptamer sandwich structure, leveraging SDA for exponential signal amplification. It achieved a detection limit of 80 cells/mL within 1 h and demonstrated strong potential for analysis of actual fish samples. Similarly, Liu et al. constructed a dual-aptamer LFD for red-spotted grouper nervous necrosis virus (RGNNV), incorporating magnetic bead enrichment and SDA[121]. This assay exhibited high specificity, with detection limits of 5 ng/mL for viral protein and 5 × 103 for infected cells, completing detection within an hour and showing high concordance with RT-PCR in real samples. These studies underscore the significant potential of aptamer-based LFDs for the rapid, on-site detection of aquatic viruses.

SPR-based detection

-

SPR-based aptamer biosensors are a powerful tool for viral detection, enabling real-time, label-free analysis of biomolecular interactions. In this technique, an aptamer is immobilized on a thin metal film. When the target analyte, such as a viral protein, binds to the aptamer, it alters the refractive index at the biosensor surface, which is detected as a shift in the SPR angle[122,123]. This allows for the direct and quantitative monitoring of binding kinetics and affinity[124,125]. The utility of SPR extends throughout the development and application of aptamer biosensors for viral detection. In an early demonstration, Misono and colleagues used SPR as a screening platform to select high-affinity RNA aptamers against the hemagglutinin protein of influenza A virus, achieving a dissociation constant of 115 pM through real-time binding monitoring[126]. Since then, SPR has been widely reported for virus detection[127]. A key advancement has been the transition to more practical and portable SPR systems. Hua et al. developed the first portable SPR aptamer biosensor for the detection of avian influenza virus (H5N1)[97]. By immobilizing a biotinylated DNA aptamer on a streptavidin-modified sensor, they achieved rapid and specific detection with a limit of 0.128 HAU in both pure cultures and poultry swab samples within 1.5 h (Fig. 8a). Cennamo et al. further demonstrated biosensor innovation with a novel SPR biosensor that uses a plastic optical fiber and an aptamer to target the novel coronavirus's spike protein[33]. Unlike traditional, expensive prism SPR systems, this team used a cost-effective, easy-to-operate D-shaped plastic optical fiber as the signal transmission medium. They precisely processed and deposited a layer of gold nano-film on the polished surface of the optical fiber to construct the SPR sensing interface. Experimental results show that its detection limit for the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 is 37 nM, and it exhibits high specificity, effectively distinguishing the spike protein of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS), and can also work stably in diluted human serum. The research conducted by Lautner et al. highlights the high reliability of SPR biosensors in handling complex samples[128]. The innovation of this study lies in combining SPR imaging with aptamer technology, creating a high-throughput platform for the direct detection of viruses in complex plant matrices. During the detection process, they directly added unpurified, complex plant extract samples to the chip. Using SPR imaging technology, the binding state of each aptamer array area on the chip can be monitored in real time and synchronously. When the sample contains the target viral capsid protein, it binds to the specific aptamer, altering the refractive index of the array area, which is then displayed as an increase in signal intensity on the SPR imaging graph. Although the plant extract contains a large amount of plant pigments, polysaccharides, proteins, and other secondary metabolites that may interfere with the detection, this aptamer biosensor still demonstrated excellent performance. This powerful ability to perform precise analysis directly in complex actual samples without labeling or complex sample pre-treatment provides a highly valuable tool for the early detection and on-site monitoring of agricultural diseases. In summary, SPR aptamer biosensors offer high sensitivity and the unique ability to analyze binding events in real-time. However, the technology faces challenges, including higher costs and the technical difficulty of detecting low-molecular-weight targets or optimizing assays for large macromolecules[129].

SERS-based detection

-

SERS-based aptamer biosensors represent a powerful technique for ultra-sensitive viral detection. SERS relies on signal enhancement from Raman reporter molecules, which is dramatically amplified when they are in proximity to nanostructured metal surfaces, typically gold or silver. These metal nanostructures create 'hotspots' that can enhance Raman signals by several orders of magnitude, enabling the detection of low-abundance targets, such as viral particles[130,131]. The core principle of a SERS aptamer biosensor involves using an aptamer to capture a target virus, which, in turn, alters the signal of a Raman reporter, allowing for highly sensitive and specific quantification. The exceptional sensitivity of SERS is demonstrated in its application to multiplexed virus detection. Chen et al. achieved simultaneous and cross-reactivity-free identification of both SARS-CoV-2 and influenza viruses by co-immobilizing specific DNA aptamers on a popcorn-like gold nanoparticle substrate[132]. Binding each virus to its corresponding aptamer decreased a unique Raman signal, Cy3 or Rhodamine Red-X (RRX), achieving detection limits of 0.78 PFU/mL for SARS-CoV-2 and 0.62 HAU/mL for influenza, with an internal standard ensuring quantitative accuracy.

A significant challenge in SERS, however, is the random and heterogeneous distribution of signal-enhancing hotspots, which can lead to poor reproducibility and hinder reliable quantification[133]. To address this, strategies such as Raman imaging, which scans across multiple hotspots to measure an average collective SERS intensity, have been successfully employed to improve data reliability[134]. Using a refined three-dimensional nano-popcorn substrate and this averaging approach, Chen's group later achieved highly repeatable detection of the influenza A (H1N1) virus with a limit of 97 PFU/mL, a sensitivity three orders of magnitude greater than traditional ELISA[100]. The power of SERS also lies in its ability to enhance other detection platforms. Song et al. developed an aptamer biosensor based on self-assembled SERS hotspots on viral surfaces for in situ detection on solid surfaces[36]. As shown in Fig. 8b, they ingeniously used the densely distributed spike protein (S protein) on the surface of the SARS-CoV-2 virus as a natural scaffold to anchor the Raman reporter molecule Cy3 and gold-silver core-shell nanoparticles to the same viral particle via two distinct specific aptamers. These nanoparticles are closely packed on the virus surface and form numerous electromagnetic field 'hot spots', thereby greatly enhancing the SERS signal of Cy3. Using this sensor, they successfully achieved in situ, highly sensitive detection of SARS-CoV-2 pseudoviruses on solid surfaces such as packaging materials, with the entire detection process taking only 20 min. With a detection limit as low as 5.26 TCID50/mL, the method showed 100% sensitivity and 100% accuracy in a blind test on 20 contaminated packaging samples, which could be used for rapid and accurate on-site screening of surface viruses without complex sampling. This confirms that SERS is among the most sensitive optical techniques available[135]. In addition, a potential drawback of solid SERS substrates is cost and consumption[136]. To create a more economical system, Gribanyov et al. developed a homogeneous SERS aptamer biosensor using functionalized colloidal silver nanoparticles[101]. This solution-based approach, which optimized for rapid aptamer-target binding, allowed a cost-effective and quantitative detection of influenza A virus (H5N1) in less than 15 min with a limit of 2 × 105 VP/mL (Viral Particles per milliliter). This progression from solid to colloidal substrates underscores the versatility of SERS and its potential for developing both ultra-sensitive and cost-effective viral detection tools.

Comparative analysis of biosensing platforms

-

The diverse aptamer-based biosensing platforms discussed each possess unique strengths and limitations, making them suited for different application scenarios. As consolidated in Table 2, a comparative analysis of electrochemical, fluorescent, colorimetric, SPR, and SERS biosensors reveals clear performance trade-offs. For instance, electrochemical and colorimetric platforms stand out for decentralized POCT, with the former offering excellent sensitivity and portability, and the latter providing the ultimate simplicity for naked-eye readout at a very low cost. Conversely, while SPR and SERS systems often involve higher costs and more complex instrumentation, they deliver unparalleled, high-information content—SPR through real-time, label-free kinetic analysis and SERS through ultra-high sensitivity down to the single-virus level and inherent multiplexing capabilities. Fluorescent biosensors strike a versatile balance, offering high sensitivity and robust multiplexing potential, though they can be hampered by background interference. Ultimately, the choice of an optimal biosensor is dictated by the specific requirements of the detection context, balancing the critical priorities of sensitivity, speed, cost, portability, and the need for quantitative precision vs simple yes/no readouts.

Table 2. Comparative analysis of aptamer-based biosensors for viral detection

Biosensor type Typical sensitivity Detection time Cost Portability Multiplexing Key advantages Major limitations Electrochemical fM–pM Minutes Low High Moderate High sensitivity, portability,

low cost, miniaturizableSusceptible to electrode fouling in complex samples Fluorescent pM–nM Minutes to hours Low-moderate Moderate High High sensitivity, versatile designs, suitable for imaging Background fluorescence requires a light source/detector Colorimetric pM–nM Minutes Very low Very high Low Naked-eye readout, simple,

low cost, ideal for POCTLower sensitivity, semi-quantitative SPR pM–nM Real-time High Low Moderate Label-free, real-time kinetics, high-information content Bulky equipment, high cost, sensitive to bulk refractive index changes SERS fM - single virus Minutes Moderate-high Moderate High Ultra-high sensitivity, fingerprinting, multiplexing Signal heterogeneity, substrate reproducibility -

Building on their distinct performance characteristics, these aptamer-based biosensors hold significant yet differentiated promise for clinical translation. The electrochemical and colorimetric platforms are prime candidates for rapid deployment in resource-limited settings. Their potential lies in enabling near-patient testing for early outbreak containment, home-based self-monitoring for chronic viral infections, and fast screening at ports of entry. Conversely, the high information content of SPR and SERS systems positions them not for decentralized testing but as powerful tools for centralized clinical laboratories. Here, they could be employed for confirmatory diagnostics, detailed viral load monitoring to track therapeutic efficacy, and advanced research into viral-host cell interactions and variant emergence. Furthermore, the multiplexing capability inherent in fluorescent and SERS biosensors paves the way for the development of syndromic panels that can simultaneously differentiate among multiple pathogens with similar symptoms (e.g., influenza, SARS-CoV-2, and Noroviruses), thereby guiding precise treatment decisions. Realizing this full clinical potential will require concerted efforts to standardize aptamer production, rigorously validate assays against gold-standard clinical methods using diverse patient samples, and seamlessly integrate these biosensing platforms into user-friendly, automated devices for routine healthcare use.

Despite compelling clinical prospects, translating aptamer-based biosensors from laboratory research to practical applications remains challenging. From the perspective of aptamer properties, some aptamers exhibit insufficient specificity and are prone to cross-reactivity with related viral subtypes or host proteins, potentially leading to false-positive results[137]. This issue is particularly critical in detection scenarios involving complex viral populations, where optimizing aptamer sequences and improving selection conditions to reduce cross-reactivity are key research priorities. In practical detection settings, proteins and lipids present in complex biological matrices (such as blood and saliva) can form biofouling that adheres to the biosensor surface, while nucleases in these matrices may degrade aptamers[138]. Under the combined effects of these two factors, it is difficult to ensure the sensitivity and specificity of the biosensor. Additionally, as nucleic acid molecules, aptamers are susceptible to degradation in both in vivo and in vitro environments. Their compromised nuclease stability significantly limits the scope of application and the timeliness of detection, making the development of stability-enhancing strategies (such as circularization) a high-priority[139].

In response to the challenges above and aligned with technological development trends, biosensors based on viral aptamers can pursue breakthroughs in multiple directions to expand their application value. To mitigate cross-reactivity and enhance specificity, the rational design of structure-switching aptamer beacons has proven highly effective[140]; these probes undergo a specific conformational change only upon binding the intended target, facilitating direct, wash-free detection in complex samples such as blood serum and reducing false positives. Concurrently, the critical issue of aptamer degradation is being addressed through innovative stabilization strategies that go beyond simple chemical modifications. The emergence of covalent aptamers[141], which are functionalized with electrophilic groups to form permanent bonds with their target proteins, dramatically increases binding resilience and resistance to displacement. Furthermore, encapsulating aptamers within protective virus-like particles (VLPs) has been demonstrated to effectively shield them from nucleases and thermal stress[142], thereby substantially improving their functional longevity in harsh biological environments. Finally, to combat biofouling and maintain sensor performance in complex matrices, advanced interface engineering using click chemistry for directional aptamer immobilization on novel nanocomposite surfaces has shown remarkable success[143], enabling ultra-sensitive and rapid detection directly in challenging samples. These targeted advances, grounded in recent experimental success, provide a robust toolkit for translating aptamer-based biosensors from sophisticated laboratory prototypes into reliable, real-world viral detection tools.

In summary, significant progress has been made in the research on biosensors based on viral aptamers. From the optimization of aptamer screening and improvement of biosensor performance to the expansion of application scenarios, their potential to revolutionize viral detection paradigms has become increasingly prominent. These biosensors also offer key advantages, including high sensitivity, strong specificity, versatile functionality, and easy deployment, enabling rapid viral detection and adaptation to resource-constrained settings. To advance the translation of such biosensors from laboratory research to clinical and practical applications in the future, in-depth interdisciplinary collaboration among chemistry, biology, engineering, and data science is essential. Only in this way can key challenges, such as those related to specificity, stability, and adaptability to complex matrices, be effectively addressed. Overall, this technology holds significant application value in disease prevention and control as well as public health security assurance, and interdisciplinary collaborative innovation is the key pathway to moving it from theory to practice and unleashing greater effectiveness.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: Jiuxing Li and Furong Wang wrote the manuscript; Jiuxing Li and Meng Liu supervised and conceived the review; Qihan Meng conducted a literature review and prepared the figures; Zhimei Huang, Yiming Ren, Zijie Zhang, Yangyang Chang, Rui Zhang, Yingfu Li, Jiuxing Li, and Meng Liu revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable requests.

-

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC; Grant Nos 22425602, 22176014), Dalian Science and Technology Talent Innovation Support Program (Grant No. 2024RJ001), the Programme of Introducing Talents of Discipline to Universities (Grant No. B25041), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. DUT25RC(3)033).

-

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

-

Aptamers are superior recognition elements, rivaling antibody affinity while offering enhanced thermal stability and design flexibility.

This review systematically analyzes aptamer selection methodologies and their integration with diverse biosensing mechanisms.

These biosensors address critical analytical gaps by enabling rapid, sensitive, and portable detection for pandemic preparedness.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Furong Wang, Qihan Meng

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wang F, Meng Q, Huang Z, Ren Y, Zhang Z, et al. 2025. Recent advances in aptamer-based biosensors for viral detection. Biocontaminant 1: e020 doi: 10.48130/biocontam-0025-0018

Recent advances in aptamer-based biosensors for viral detection

- Received: 16 October 2025

- Revised: 08 November 2025

- Accepted: 19 November 2025

- Published online: 18 December 2025

Abstract: Viral pathogens pose a persistent and devastating threat to global health, as starkly demonstrated by recent pandemics. The cornerstone of an effective response is rapid and reliable viral detection. Yet, conventional methods like viral culture, immunoassays, and nucleic acid amplification tests are hampered by limitations in speed, cost, sensitivity, and portability. Aptamers, single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides selected in vitro, have emerged as powerful molecular recognition elements that rival antibody affinity while offering superior thermal stability, manufacturability, and design flexibility. These attributes make them ideal for integration into next-generation biosensors. This review systematically summarizes recent advancements in aptamer-based biosensors for viral detection. It provides a comprehensive analysis of key methodologies for selecting virus-specific aptamers and a detailed examination of the various signal transduction mechanisms employed, including electrochemical, fluorescent, colorimetric, Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), and Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) biosensors. By critically evaluating the integration of high-affinity aptamers with diverse biosensing architectures, this work aims to establish a clear framework for understanding current progress and future directions. The review underscores the potential of these biosensors to deliver the rapid, sensitive, and field-deployable devices urgently needed for pandemic preparedness and effective viral outbreak management.

-

Key words:

- Aptamer /

- Viral detection /

- Biosensors /

- SELEX /

- Biocontaminant