-

Antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) are regarded as biocontaminants due to their transmissibility, heritability, and potential risks to human health[1]. The widespread occurrence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) and ARGs has been increasingly recognized as a critical threat to global public health[2,3]. Accelerated climate change is reshaping Earth's environmental systems by driving global temperature increases, triggering large-scale glacier melting, and contributing to rising sea levels[4]. Meanwhile, the spatial extent of human activities has progressively expanded, encroaching upon remote and previously pristine environments[5]. The stresses arising from global change (including climate change and anthropogenic activities) have profoundly influenced the composition and function of microbial communities and may further contribute to the development and evolution of bacterial antibiotic resistance and virulence factors (VFs)[6,7]. Viewed through the One Health framework, the convergence of global change and stress resistance highlights the urgent need to integrate environmental, animal, and human health considerations to develop effective strategies to mitigate microbial drug resistance[8].

Global change is severely impacting the glacier continuum, a connected sequence of environments influenced by glacier meltwater that extends from the glacier itself to downstream ecosystems[9]. Glaciers, which preserve microorganisms and genetic material under extreme cold, low-nutrient, and low-light conditions[10,11], are now warming at rates several times higher than the global average[12,13]. This rapid warming destabilizes long-standing microbial and genetic archives. The accelerated release of ancient microbes, potential pathogens, and ARGs from glacier meltwater raises increasing concerns about their downstream impacts[14]. Crucially, as meltwater flows through the glacier continuum, it transports microbial communities and resistance genes across interconnected aquatic habitats, thereby transforming localized ARG reservoirs into dynamic dissemination pathways.

Despite the growing recognition of ARGs in glacial environments, existing studies seldom regard different glacier habitats as a unified, connected ecological system. Most research isolates supraglacial ice, cryoconite, rivers, or lakes as separate units[15,16], leaving the spatiotemporal dynamics of ARG transmission along the glacier continuum poorly characterized. This represents a significant knowledge gap because glacier-fed freshwater ecosystems serve as critical water sources and ecological hubs in both polar and high-altitude regions.

Microbial communities inhabiting glaciers represent valuable genetic repositories for exploring ancient, naturally occurring antibiotic resistance predating the antibiotic era[17−19]. Resistance determinants in glacial bacteria are acquired through natural selection and mainly disseminated through vertical inheritance[20] and horizontal gene transfer[21,22]. Compared to anthropogenically impacted environments, glaciers exhibited a relatively low abundance of ARGs[7]. The expansion of human activities may enhance the spread of ARGs within glacial microorganisms. Investigating ARG profiles in remote natural environments could provide valuable insights into the evolution of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria. Growing evidence also shows that mobile genetic elements (MGEs) and VFs co-occur with ARGs in polar and Xizang glaciers[23−25], raising concerns about the emergence of multi-resistant and potentially pathogenic strains under warming conditions[26,27]. As glacier meltwater is a primary freshwater source for many regions[28], elucidating ARG transport, transformation, and co-selection along the glacier continuum is essential for assessing microbial risks within the One Health context.

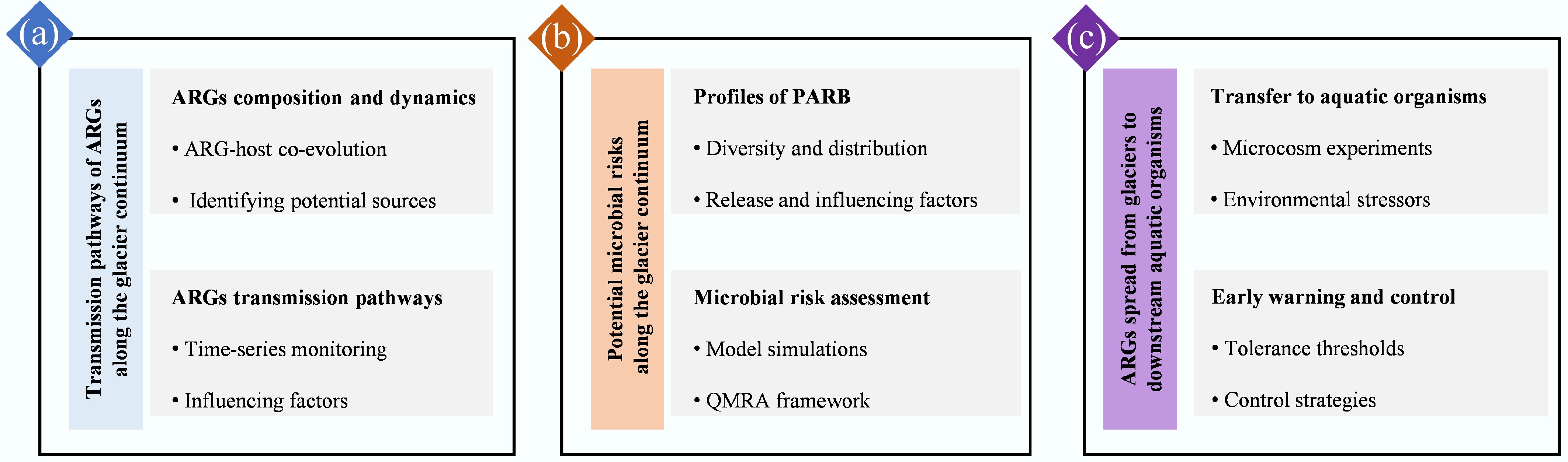

Here, a comprehensive review is provided that: (1) synthesizes current knowledge on the occurrence, diversity, source, and dissemination mechanisms of ARGs in glaciers under the influence of global change; (2) highlights the importance and necessity of viewing glacier-connected habitats as an integrated system; (3) proposes future research directions for ARG surveillance and risk assessment within the One Health framework.

-

The recognition of ARGs as biocontaminants due to their ability to persist in diverse environments and their potential to negatively impact the environment and pose risks to human health. Antibiotic resistance is a natural, ancient evolutionary phenomenon that predates human use of antibiotics[17]. However, the prevalence, development, and spread of resistance to modern antibiotics have been too rapid and widespread to be attributed solely to spontaneous mutations[1,29]. Unlike traditional chemical pollutants, ARGs are biological entities embedded within microbial genomes or MGEs. Their capacity to spread via horizontal gene transfer (HGT) enables resistance traits to rapidly disseminate among microbial communities, including opportunistic and pathogenic bacteria, thereby elevating the risk of antimicrobial resistance-associated infections[30].

Furthermore, ARGs can remain stable in soils, sediments, and cold environments such as glaciers and permafrost for extended periods[8]. Such persistence raises concerns about the re-emergence of ancient ARGs driven by climate change, including glacier retreat and permafrost thaw. With glacial meltwater increasingly contributing to downstream freshwater systems, the potential spread of ARGs into drinking water resources intensifies global health risks. Therefore, the release of ARGs from glaciers into the environment emphasized the need to study and monitor these environments.

-

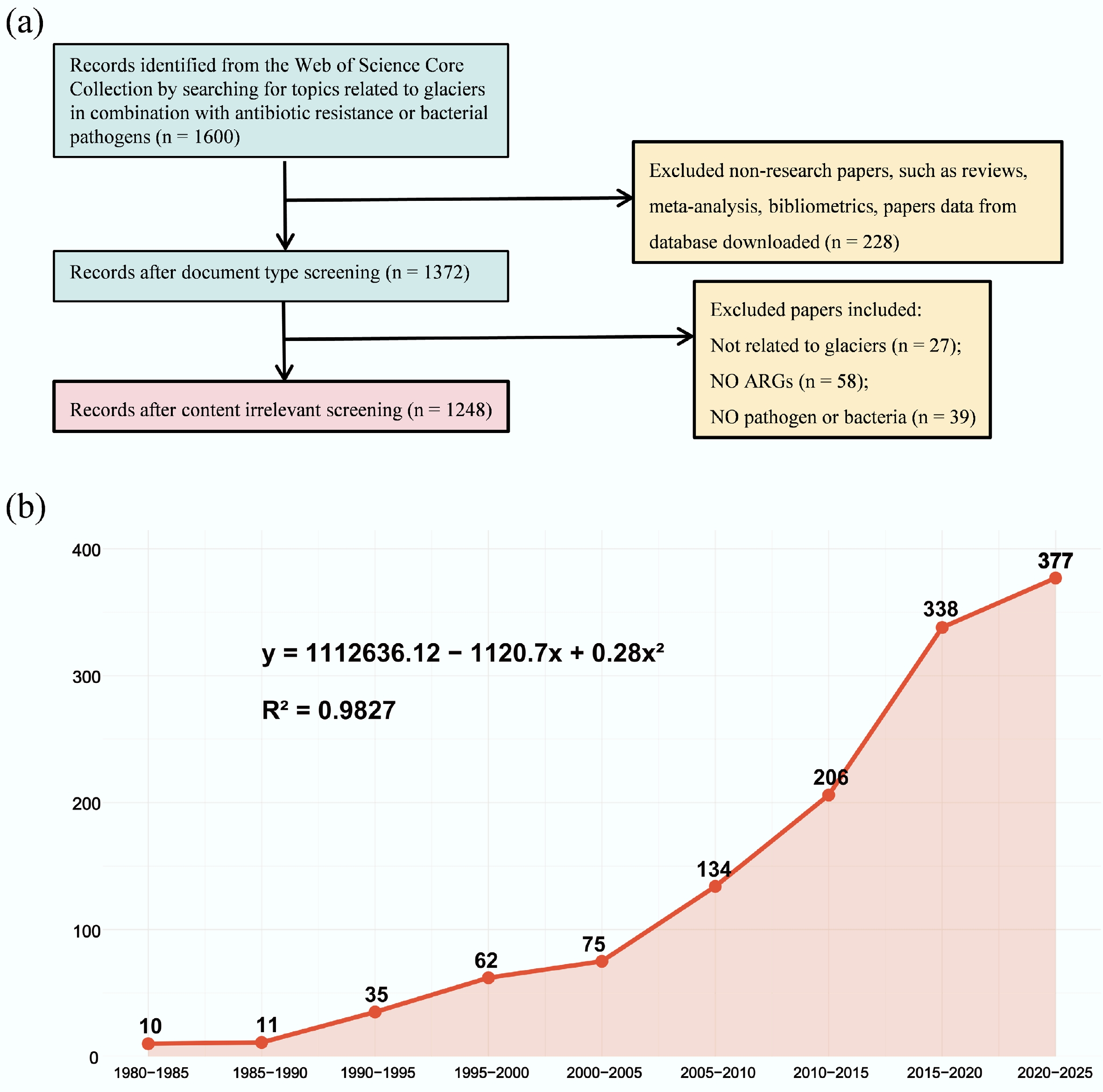

Recently, several studies have revealed the high prevalence of resistomes and ARBs in glacial environments[20,31,32]. A total of 1,248 studies on ARG profiles in the glacier were obtained in this study. The annual number of publications from 1980 to 2025 is shown in Fig. 1a. Over the last 15 years, the number of research reports on ARGs in the field of glaciers has rapidly increased. The increase in the number of publications fitted in the quadratic equation (R2 = 0.9827; Fig. 1b). Generally, surveys of ARGs have surged in the past 15 years, which has attracted wide attention from researchers. Table 1 summarizes the ARG gene types, resistance mechanisms, and drug classes in glacial environments worldwide. Genes encoding β-lactamases, bacitracin, and glycopeptides were enriched in glacial environments[31−35]. Notably, the distribution and characteristics of ARGs differ among glaciers due to variations in geographic location and environmental conditions.

Figure 1.

(a) Number of documents at each stage of the screening process. (b) Development trend of papers and research fields from 1980 to 2025.

Table 1. Examples of ARGs, resistance mechanisms, and drug classes detected in glacial environments worldwide

Class Mechanism type Gene type Location Approach Ref. Aminocoumarin Drug efflux mdtB King George Island, West Antarctica Metagenomic analysis [36] mdtC Abisko, Sweden Metagenomic analysis [37] Aminoglycosides Drug inactivation aac, ant Mackay Glacier, South Victoria Land, Antarctica Metagenomic analysis [20] aac, aph Chongce glacier, and Eboling mountain, Xizang Metagenomic analysis [38] aac(6')-Ib3, aph(2')-Id Tianshan Mountain Urumqi No.1 glacier Metagenomic analysis [39] Drug efflux amrB King George Island, West Antarctica Metagenomic analysis [36] Beta-lactam Drug efflux acrB, mexB, tolC Lake Namco, Qiangyong glacier, Xizang Metagenomic analysis [33] Drug inactivation Class A: bla(GES, VEB, NPS, CTX, PSE);

Class C: bla(EC);

Class D: bla(OXA)Chongce glacier, and Eboling mountain, Xizang Metagenomic analysis [38] Target replacement mecA River Lena region in Central Yakutia, Russia Bacterial genomic sequencing [40] Bacitracin Target modification bacA, bcrA Chongce glacier, and Eboling mountain, Xizang Metagenomic analysis [38] bacA King George Island, West Antarctica Metagenomic analysis [36] Glycopeptide Target modification vanHA Bear Creek, Yukon, Canada Metagenomic analysis [17] vanR McMurdo Dry Valleys, East Antarctica Microarray GeoChip 4.0 [41] Macrolides Drug efflux macB King George Island, West Antarctica Metagenomic analysis [36] oleC Kongsfjorden Region of Svalbard in the High Arctic SmartChip Real-Time PCR [42] Target protection ermC River Lena region in Central Yakutia, Russia Bacterial genomic sequencing [40] ermC Northern Bering Sea qPCR [43] Drug inactivation mph River Lena region in Central Yakutia, Russia Bacterial genomic sequencing [40] MLSB (macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B) Target protection msrA River Lena region in Central Yakutia, Russia Bacterial genomic sequencing [40] Target modification erm(K, 34, 36) Kongsfjorden Region of Svalbard in the High Arctic SmartChip Real-Time PCR [42] Quinolones Drug efflux qepA Northern Bering Sea qPCR [43] Target protection qnr(A, B, D, S) Northern Bering Sea qPCR [43] Target modification gyrA Abisko, Sweden Metagenomic analysis [37] Sulfonamides Target replacement sul(1, 2, 3) Northern Bering Sea qPCR [43] sul(1, 2) Chongce glacier, and Eboling mountain, Xizang Metagenomic analysis [38] Target modification folP Abisko, Sweden Metagenomic analysis [37] Tetracyclines Drug efflux tet(A, B, C, D) Northern Bering Sea qPCR [43] tet(D, L, G, Y, 33, 39) Chongce glacier, and Eboling mountain, Xizang Metagenomic analysis [38] Target protection tet(M) Northern Bering Sea qPCR [43] tet(M, O, 36) Chongce glacier, and Eboling mountain, Xizang Metagenomic analysis [38] Trimethoprim Target replacement dfrA Mackay Glacier, South Victoria Land, Antarctica Metagenomic analysis [20] dfrE King George Island, West Antarctica Metagenomic analysis [36] Multidrug Drug efflux acrE King George Island, West Antarctica Metagenomic analysis [36] acr(A,R) Kongsfjorden Region of Svalbard in the High Arctic SmartChip Real-Time PCR [42] mepA Kongsfjorden Region of Svalbard in the High Arctic SmartChip Real-Time PCR [42] Antarctic glaciers are among the least affected by human activity. However, the presence of scientific stations and the increase in anthropogenic activity have favored the introduction of ARG-harbouring bacteria[11,44,45]. Several studies have shown that the dissemination of ARGs in the Antarctic environment can be influenced by the presence of both humans and animals[8,46−49]. Bacterial isolates from areas under human influence were resistant to several antibiotic groups. They were mainly associated with genes encoding aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes (AMEs) and extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs), in contrast with those recovered from areas with low human intervention, which were highly susceptible to antibiotics[50,51]. Moreover, the presence of resistance to synthetic and semisynthetic antibiotics, identified in zones associated with human activity, suggests that these resistant isolates could be linked to human presence[50,52]. Alternatively, samples from far-inland Antarctica indicated interspecies competition and vertical inheritance contributed to the presence of ARGs, suggesting that antibiotic resistance originated naturally prior to the antibiotic era[11,17,20].

In the Arctic, humans have inhabited for millennia, and industrial development has been intense, resulting in the local biota being exposed to anthropogenic pressure[26,47]. In Canada's high Arctic, 84% of coliform isolates from glacial ice and water were resistant to cefazolin, 71% resistant to cefamandole, and 65% resistant to ampicillin[53]. Some isolates were resistant even toward broad-spectrum antimicrobials, such as ciprofloxacin and chloramphenicol[54]. A study in the Kamchatka Peninsula and the Commander Islands assessed antibiotic resistance in heterotrophic bacterial isolates and determined that one isolate carried ESBL type CTX-M genes blactx-m-14 and blactx-m-15[55]. Resistant phenotypes to these ESBLs are considered clinically relevant[56]. Sulfonamide genes (sul1, sul2, and sul3) were most prevalent, and 87% of targeted ARGs were detected in the Arctic and sub-Arctic samples[43]. These genotypes were the most abundant in regions heavily impacted by humans[57]. The fact that these genotypes are found in remote parts of the Arctic may support the theory that the ARGs in the polar region arose from a mix of human influence and natural processes.

Similarly, the microflora in the glacial environment on the Xizang Plateau developed resistance mechanisms to multiple antibiotics, including β-lactams, glycopeptides, tetracyclines, chloramphenicol, and fluoroquinolones[33,38,58]. These antibiotic resistance mechanisms are mainly encoded by ARGs, which can be spontaneous mutations or acquired features[59]. Compared with human-impacted environments, the relatively low abundance of ARGs in glacial environments on the Xizang Plateau[33,38,60] indicates that central Asian and Himalayan glaciers had the highest levels of ARG detection compared to Arctic and Antarctic glaciers. Quantitative microbial risk assessment (QMRA) is a framework for quantifying the human infection risks posed by ARB and is an effective tool for predicting potential transmission. However, its application in glacier-associated ARB research remains limited; to date, only one study has applied QMRA to assess ARB risks on the Xizang Plateau. The results indicated that the infection risk associated with ARB in this region is low and remains below safety thresholds[21].

Behaviors of ARGs in glacial environments are often associated with two genetic mechanisms, e.g., genetic flow both vertically[20] and horizontally[38]. Indeed, positive correlations between MGEs and ARGs were identified in the absence of antibiotic selective pressure[32,40,61]. Specifically, the spread of ARGs as genetic elements can be mediated by conjugation, transduction, and transformation[62]. As ARGs can flow along melting streams and conjugate with other functional genes (e.g., VFs and metal resistance genes)[31,35,38] through horizontal gene transfer from other microbes, public health-oriented microbiological risk studies would benefit from devoting specific attention to ARGs in glaciers.

The spatial heterogeneity of ARGs across different glacial regions is driven by the combined effects of geographical and climatic factors, local microbial ecology, and anthropogenic impacts[63]. Geographical and climatic factors shape regional ARGs by regulating microbial activity and the potential for gene exchange. In extremely oligotrophic and cold environments, intense interspecies competition acts as a potent natural selective force, favoring broader-spectrum intrinsic ARGs as defense strategies[64]. In addition to being naturally occurring, human activities can also influence the profiles of ARGs in glacier environments. The Arctic is the most severely affected region due to long-term human habitation and industrial activities[65]. Although the Xizang Plateau is remote, it is still influenced by pollutants transported from South Asia via atmospheric circulation systems such as the Indian monsoon[21].

-

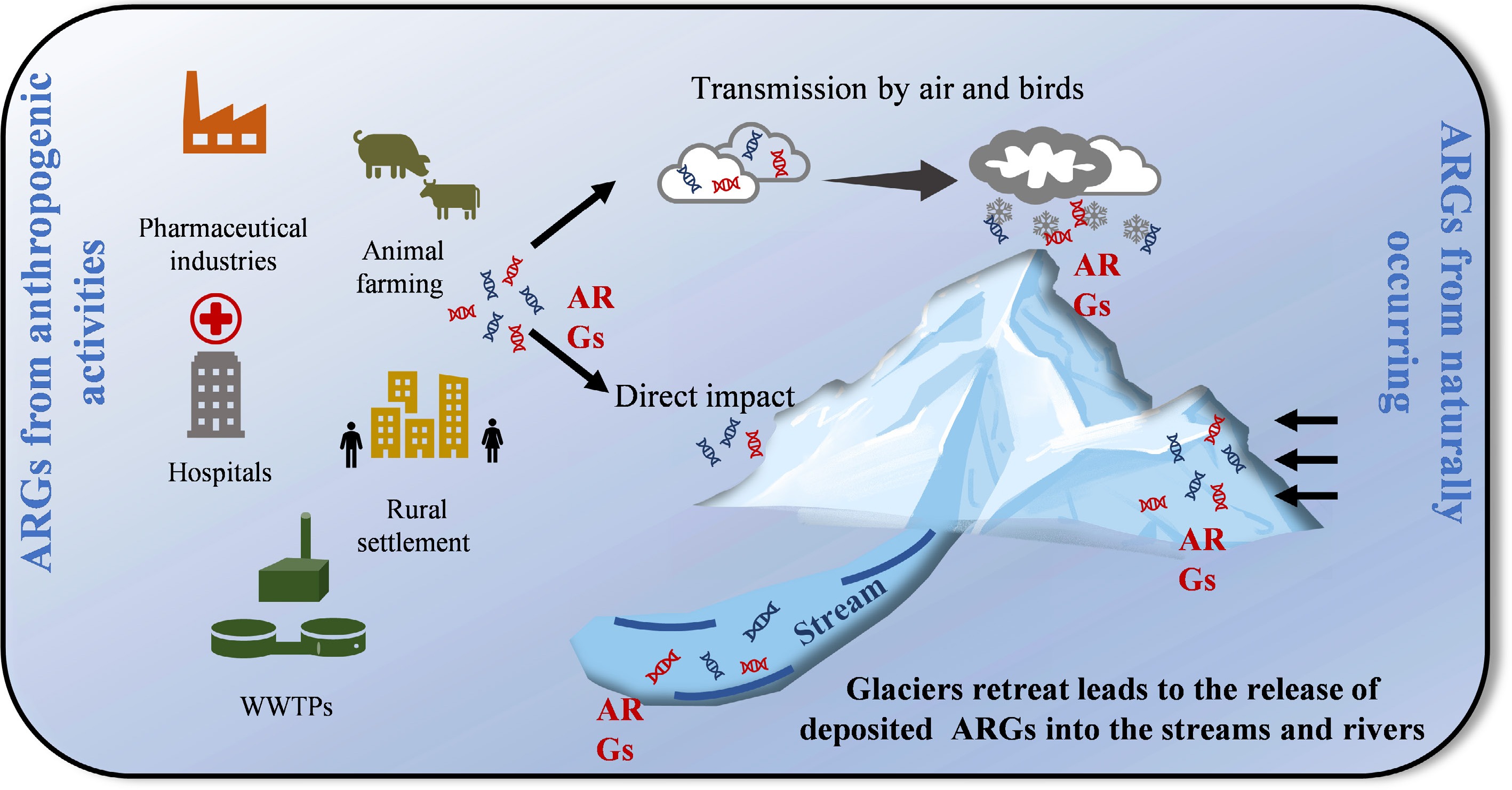

The sources of ARGs in glaciers can be divided into two types: native and from human activities (Fig. 2). The extreme environmental conditions have fuelled resistance, particularly broad-spectrum resistance. In harsh environments, bacteria that produce antibiotics would provide a competitive advantage in the fight for limited nutrients[66]. Along with antibiotic production, antibiotic resistance is a protective mechanism in bacteria, serving as a defense against their own antibiotics or as a by-product of proximity to antibiotic-producing neighbors[67]. This competitive advantage was validated by a study in Antarctica, which found that ARG abundance was negatively correlated with species richness[20]. Recently, several studies reported the presence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and ARGs in remote, pristine glaciers. For example, ARGs (sul2, strA, and strB) were detected in the 1,200–1,400-year-old Antarctic ice core during the pre-antibiotic era[68]. Segawa et al.[60] described 45 ARGs in snow and ice from glaciers distant from human activities. Naturally occurring ARGs were reported in the Mackay Glacier region of Antarctica, and these genes are ancient acquisitions of horizontal transfer events[20]. These findings support that glaciers are a known source of ancient ARGs[17].

In addition to being naturally occurring, human activity can also influence the profiles of ARGs in glacier environments. Atmospheric particles and migratory birds can transport ARGs from human-impacted regions to glacier environments[21]. A study found that some ARGs resistant to synthetic antibiotics (e.g., tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones) are more abundant in Central Asian and Himalayan glaciers[60]. This is linked to the overuse of antibiotics in neighboring countries (India and Nepal)[69], which leads to ARG-harboring bacteria and airborne ARGs settling on glacier surfaces via the Indian monsoon. Multiple studies have shown that the spread of ARGs in the Antarctic environment is influenced by both human and animal activities[11,45,70]. In contrast, the Arctic has supported human habitation for thousands of years and has experienced intensive industrial development, imposing substantial anthropogenic pressure on its native ecosystems[47,71]. Consequently, the Arctic displays markedly higher ARG levels—up to one to two orders of magnitude greater than those observed in Antarctica[47,60]. More than 570 antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains have been isolated from Arctic environments, including those resistant to fluoroquinolones and cephalosporins, with some even showing resistance to broad-spectrum antimicrobials such as ciprofloxacin and chloramphenicol[54]. Nonetheless, it is challenging to differentiate anthropogenically influenced ARGs from naturally occurring ARGs in areas with limited anthropogenic impacts.

-

Glaciers are the most important water source. These glaciers are melting due to the recent trend of global warming. ARGs stored in glaciers can undergo substantial horizontal gene transfer upon release into downstream environments. Traditionally, studies on ARGs in glacier-fed ecosystems have treated glaciers, rivers, and lakes as discrete entities[15,16]. However, this isolated approach makes it challenging to capture the dynamic processes by which ARGs are transported from glaciers to downstream lakes. We propose investigating the dissemination of ARGs within the glacier continuum. This continuum serves as a crucial pathway for the dissemination of ARGs from glaciers to downstream environments (Fig. 3). Within the glacier continuum, glaciers and lakes are closely connected via river systems. Rivers transport both biotic and abiotic materials from glaciers to downstream environments[72]. ARB and their associated ARGs exhibit different characteristics along this continuum. The cold, oligotrophic conditions of glaciers favour the preservation of resistant bacteria and ARGs, making glaciers an important reservoir of ARGs. Rivers can impose multiple environmental selection pressures that may facilitate the transfer and spread of ARGs among environmental microbes and hosts, thereby becoming hotspots for ARG-microbe exchange. When ARGs enter lakes, the convergence of upstream and native microbial communities can facilitate recombination between ARGs and indigenous microbes[35], transforming lakes into reservoirs for ARG accumulation. More importantly, ARGs may be transmitted and amplified through the lake food web, thereby exacerbating threats to ecological systems and human health.

Bacteria carrying ARGs released by glacier melting may incorporate and conjugate other functional genes under co-selective agents (e.g., heavy metals and pharmaceutical products) in downstream environments, potentially causing adverse ecological and human health effects. The issue of environmental antibiotic resistance can be addressed within the One Health paradigm. Previous studies indicated that heavy metal exposure can promote resistance to a wide range of antibiotics[31,73]. In addition, pharmaceutical products may share mechanisms of action with antibiotics, leading to the emergence of resistant and virulent clones[10,74]. ARG-VF coexistence patterns are important targets in microbiological risk assessment[25] because VFs confer on bacteria the ability to overcome host defense systems and cause disease, and the acquisition of antibiotic resistance contributes to survival under antibiotic therapy[75,76]. In one study of an Antarctic glacier, pathogenic phyla that harbor many clinical pathogens were found to harbor the most significant number of ARGs[20]. Similarly, ARG-VF coexistence in glacier cross-habitats was detected by metagenomic analysis[38]. Studies have begun to demonstrate the potential mobility of these ancient ARGs[77]. For example, the identification of identical ARG sequences shared between ancient bacteria and modern clinical isolates provides compelling evidence for the historical mobility and contemporary relevance of these resistance determinants[40]. Therefore, identifying ARGs and ARG-carrying bacteria and understanding their fates in the glacier continuum is vital for microbiological risk assessment from glaciers into downstream environments.

-

A plethora of methodologies, incorporating both culture-dependent and culture-independent approaches, have been established for the detection and quantification of ARGs in glacial environments. The Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method, a classic culture-dependent phenotypic technique, effectively screens for potential antibiotic-resistant strains by measuring the diameter of inhibition zones around antibiotic-impregnated discs on agar plates[31,32]. However, given that 99% of microbial taxa in glacial environments are unculturable under standard laboratory conditions, this method has significant limitations for comprehensive surveys of ARG diversity and quantitative analysis across large-scale glacial habitats.

In molecular biology, culture-independent techniques such as Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) have overcome the technical limitations associated with microbial culturability[78]. However, the efficacy of their detection is constrained by the specificity of pre-designed primers, which allows only for the targeted detection and relative quantification of ARGs with known sequence structures. It is noteworthy that the advent of shotgun metagenomics has engendered a pioneering research paradigm for the comprehensive elucidation of the composition and abundance distribution of genetic elements within environmental samples. This technique involves unbiased high-throughput sequencing of total genomic DNA from environmental samples, coupled with multidimensional bioinformatics analysis pipelines that include sequence assembly, open reading frame prediction, and gene annotation. This enables the systematic identification and precise quantification of ARGs. The application of functional metagenomic analysis strategies has been extensively explored for ARG profiling and environmental health risk assessment across a range of cryospheric habitats, including polar and alpine glaciers. These strategies leverage the comprehensive detection capability afforded by metagenomic analysis, a field of research that has seen significant advancements in recent years[79,80].

The synthesis of findings across different glacial studies is often hampered by the use of disparate sampling designs, detection platforms (e.g., qPCR vs metagenomics), and data normalization methods (e.g., per 16S rRNA gene copy, per cell, RPKM/TPM for metagenomes). To facilitate cross-study comparisons and more robust quantitative trend analyses, we propose greater methodological standardization. Table 2 summarizes key methodologies and proposes considerations for future work.

Table 2. Comparison of methods for detecting ARGs in glacial environments

Method category Specific technique Principle Advantages Limitations Recommendations for standardization Culture-dependent Kirby-Bauer Disk Diffusion[81] Measures the zone of inhibition around the antibiotic disc Simple, low-cost, provides phenotypic resistance data Misses > 99% of unculturable microbes; low throughput Use as a complementary method to characterize isolated strains. Standardize media and incubation conditions Targeted molecular Quantitative PCR (qPCR)[82] Amplifies and quantifies specific, known ARG sequences using primers Highly sensitive and quantitative for targeted genes Limited to pre-selected targets; primer bias Use universal 16S rRNA gene normalization for bacterial abundance; Report detection limits; Use standardized primer sets when available High-Throughput qPCR (SmartChip)[83] Allows simultaneous quantification of hundreds of pre-defined ARGs High-throughput for targeted genes; broad profiling Still limited to pre-designed assays; high cost Normalize data per 16S rRNA gene. Clearly report the targeted gene panel Untargeted molecular Shotgun Metagenomics[84,85] Random sequencing of all DNA in a sample, followed by bioinformatic annotation Captures both known and novel ARGs; provides context (MGEs, hosts) Computationally intensive; depth of sequencing affects detection sensitivity Recommendation for primary use. Use deep sequencing. Normalize using reads per kilobase per million (RPKM/TPM) or cell count; Use standardized, curated databases (e.g., CARD, SARG); Deposit raw data in public repositories Emerging: Long-Read Sequencing (e.g., Nanopore, PacBio)[86] Sequences long DNA fragments Resolves complete ARG contexts (plasmids, chromosomes); links ARGs to hosts Higher error rate (Nanopore); lower throughput; higher cost Use for resolving genetic context and host association; Combine with short-read data for hybrid assembly for accuracy Taking traditional and emerging approaches into account, we propose an integrative metagenomics-based framework for retrieving ARGs profiling in glaciers. Briefly, three key components will be integrated: (1) The procedures, including sample preparation, sequencing, and output quality check, should be performed following a consistent and standardized workflow; (2) Metagenomic datasets will be annotated using a high-quality reference database (e.g., CARD, SARG, and ARDB); (3) Further laboratory experiments are used to study characteristics of phenotype.

-

The glacier continuum reflects the up–down relationships in ARGs dissemination and reveals how glacial melt influences their downstream transport[32,87,88]. However, most studies are limited in spatial and temporal scope, overlooking seasonal climatic variations, human activities, and key hydrological or atmospheric factors[89−91]. Glacier melt can release ARGs into downstream ecosystems, and identifying their potential sources remains a challenge. Long-read sequencing and ARG-host coevolution approaches are used to trace the evolutionary history of ARGs, enabling differentiation between ancient intrinsic ARGs and those introduced by anthropogenic contamination. Elucidating the dynamics of ARGs along the glacier continuum and clarifying the role of human activities are critical for tracking ARG sources in glacier ecosystems.

Future studies should implement time-series monitoring frameworks. Integrating high-resolution environmental sampling with metagenomic and hydrometeorological data will allow researchers to quantify ARGs export fluxes and identify 'seasonal hot moments' of ARGs release. Sequence similarity analyses were performed to compare ARG variants across glaciers, rivers, and lakes, thereby elucidating the temporal and spatial trajectories of ARG transmission. By incorporating environmental factors and antibiotic concentrations, the key factors influencing ARG transport along the glacier continuum were identified (Fig. 4a).

Identifying pathogenic antibiotic-resistant bacteria (PARB) released from glaciers to downstream environments and assessing their potential risks

-

PARB, which carries both VFs and ARGs, serves as a key indicator of microbial risk. Research on their survival and risk assessment remains limited, primarily focusing on abundance and genetic composition[11, 44,45]. Increasing evidence shows that both glacier microenvironmental factors (e.g., temperature, pH, conductivity, chemical pollutants, and microbial communities) and macro-scale human activity indicators (e.g., population density, land use, and industrialization) influence the transfer and transformation of VFs and ARGs among PARB[92,93], causing habitat-specific variation in potential risks. Therefore, tracing PARB transmission along the glacier continuum is essential for evaluating ecological risks.

Future work will evaluate risks based on the antibiotic resistance and virulence effects of PARB. Model simulations will be conducted to identify the major drivers shaping microbial risks across the glacier continuum. To strengthen the health relevance of glacial ARG research, it is essential to move beyond descriptive abundance data and integrate a QMRA framework (Fig. 4b).

Elucidating the transmission of ARGs from glaciers to downstream aquatic organisms

-

ARGs can move through food webs, with studies showing their transfer to higher-trophic organisms via MGEs in soil[94] and similar accumulation in aquatic animals, such as fish, as they pass along the food chain[95]. Glacial melt releases resistant bacteria and ARGs into downstream waters, where they may undergo horizontal transfer, be absorbed by organisms, or persist in sediments. ARGs can bioaccumulate in lower-trophic organisms and be passed to higher-trophic organisms. However, the transmission patterns and ecological risks of ARGs in high-altitude lake food webs remain poorly understood. Clarifying how ARGs and their host spread from glaciers to downstream aquatic organisms is essential for anticipating and mitigating these risks.

Future work will establish microcosm experiments to investigate how PARB influences the resistance and toxicity responses of aquatic organisms under various environmental stressors (e.g., antibiotics and warming) (Fig. 4c). The tolerance thresholds of aquatic organisms to PARB and the corresponding antibiotic risk levels will be determined, and early-warning strategies will be developed based on these thresholds.

-

Glaciers, once considered pristine environments, are increasingly recognized as reservoirs and potential sources of ARGs in a rapidly changing world. Accelerated glacier melting, driven by global climate change and intensified human activities, facilitate the release and downstream dissemination of ARGs from glaciers, posing potential biosecurity risks. This study reviewed evidence showing that ARGs in glaciers originate from both natural sources and atmospheric circulation. ARGs interact with indigenous microbial communities, MGEs, and co-selective stressors, enhancing their persistence, transfer, and potential amplification in downstream environments. The convergence of ARGs and PARB highlights the escalating ecological and health risks associated with glacial meltwater, particularly in high-altitude and polar regions that serve as critical freshwater sources.

To safeguard ecosystem and public health within the One Health framework, it is essential to view glacier-connected habitats as an integrated system, elucidate the spatiotemporal dynamics of ARGs along the glacier continuum, and identify key transmission pathways from glaciers to aquatic organisms. Future research should adopt holistic approaches that integrate model frameworks and predictive analyses better to forecast the potential resurgence of ancient resistance genes, mitigate ARG dissemination, and develop strategies to preserve microbial and environmental safety within the glacier continuum under a warming climate.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Guannan Mao; analysis and interpretation of results: Huiling Ying, Yadi Zhang, Wei Hu; data collection: Guannan Mao, Huiling Ying; draft manuscript preparation: Guannan Mao, Huiling Ying; review and editing: Guannan Mao, Wentao Wu; funding acquisition: Guannan Mao. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

This study was supported by the The National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 92451301 and 42101128).

-

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this paper.

-

Glaciers are a potential reservoir of ARGs.

A systematic comparison reveals ARGs distribution across major glacial regions.

Future studies should focus on ARGs transmission along the glacier continuum.

Focus is needed on downstream risks from ARGs released by glacier melt under climate change.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Ying H, Zhang Y, Hu W, Wu W, Mao G. 2025. Glaciers as reservoirs of antibiotic resistance genes: hidden risks to human and ecosystem health in a warming world. Biocontaminant 1: e021 doi: 10.48130/biocontam-0025-0022

Glaciers as reservoirs of antibiotic resistance genes: hidden risks to human and ecosystem health in a warming world

- Received: 11 October 2025

- Revised: 23 November 2025

- Accepted: 25 November 2025

- Published online: 18 December 2025

Abstract: Antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) are biocontaminants that pose a growing threat to environmental and public health, a challenge further intensified by the impacts of climate change on glaciers. Glaciers act not only as exceptional natural archives preserving microbial communities and ARGs for thousands to millions of years, but also as critical upstream sources for freshwater systems. The release of ARGs from glaciers into downstream freshwater environments raises serious concerns because glacier-fed rivers and lakes function as essential ecological and drinking water resources across high-altitude and polar regions. Although ancient antibiotic resistance has long existed in natural environments, how ARGs are transformed and disseminated along the glacier continuum remains poorly understood. This review synthesizes current knowledge on the characteristics, sources, transmission pathways, and potential ecological and health risks of ARGs in the glacier continuum. Importantly, this review highlights a key conceptual gap: existing studies typically treat distinct glacier habitats in isolation, failing to consider them as an integrated system. We therefore propose the glacier continuum, emphasizing that glacier surface ice, proglacial streams, and downstream lakes collectively shape the transport and transformation of ARGs. Moreover, developing early-warning frameworks based on the toxicological responses of aquatic biota will be crucial for assessing and mitigating the ecological risks posed by glacier-released ARGs. These integrative approaches are crucial for mitigating emerging risks and protecting these fragile and relatively pristine environments under a warming climate.

-

Key words:

- Biocontaminants /

- Antibiotic resistance genes /

- Glacier continuum /

- Potential risks /

- Global change