-

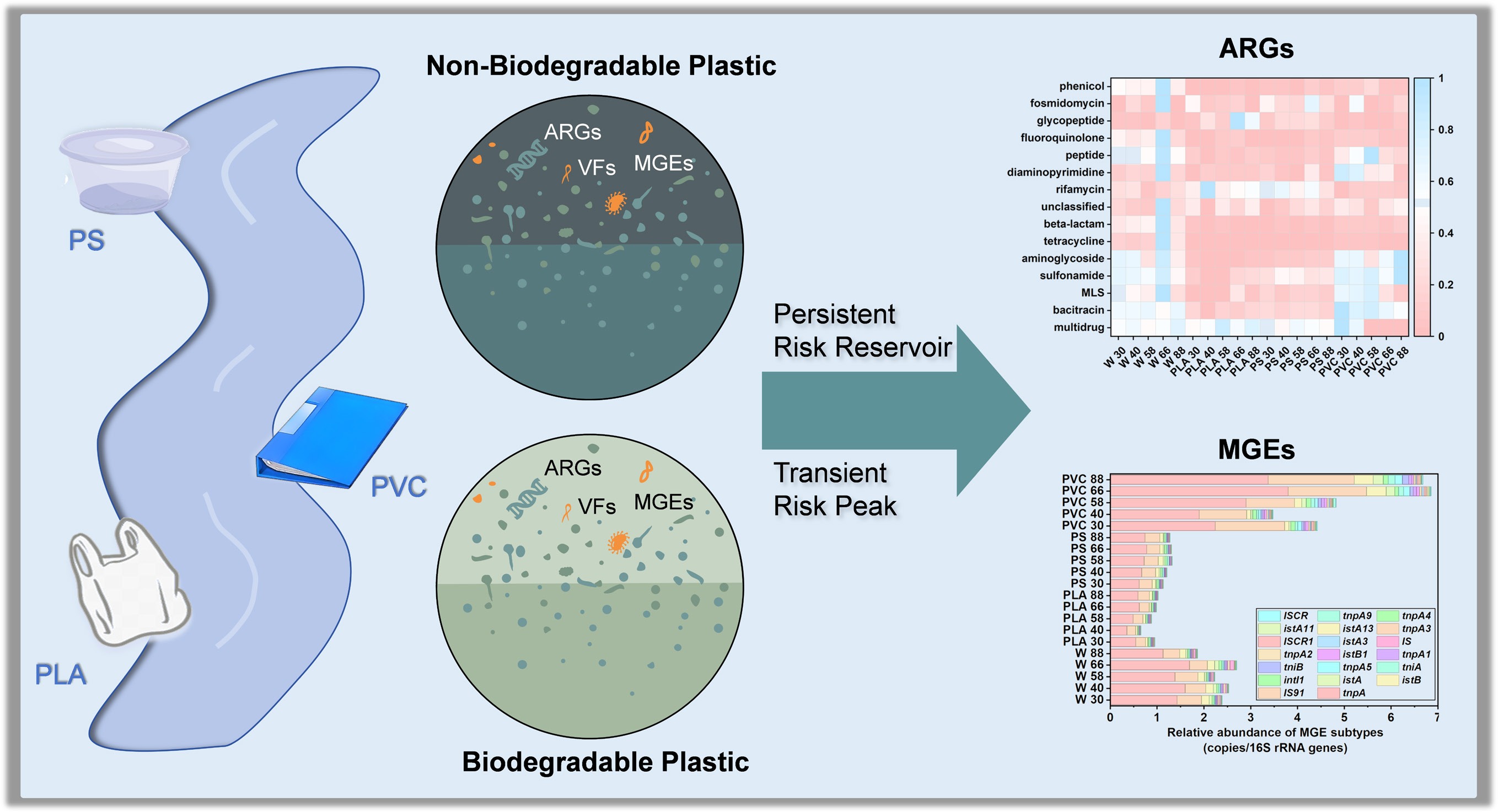

The extensive use and improper disposal of plastic products have caused the accumulation of plastic across diverse environments, especially in aquatic systems[1,2]. Discarded plastics entering water bodies undergo physical and chemical weathering, fragmenting into smaller pieces and microplastics (MPs; plastic particles < 5 mm)[3]. As an emerging contaminant, MPs have attracted global attention because of their environmental impacts[4]. Beyond their physical impacts, plastic fragments serve as novel substrates for microbial colonization, leading to the formation of distinct biofilm communities known as the "plastisphere". This anthropogenic microhabitat is now widely recognized as far more than a passive surface; it is an active ecological niche that selectively enriches microbial taxa distinct from those in the surrounding water column[5]. Initially conceptualized by Zettler et al.[6], the plastisphere is an anthropogenic microenvironment that supports distinct microbial assemblages compared with the surrounding water[7−9]. Plastisphere-associated microorganisms display unique biogeochemical capabilities[10]. For example, genes involved in carbon fixation and denitrification are often enriched in plastisphere biofilms[11], thereby influencing greenhouse gas emissions such as carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide[12], and affecting global biogeochemical cycles. Moreover, the formation of the plastisphere can promote specific bacterial taxa that reshape the surrounding microbial communities and alter ecosystem functions[11,13,14]. Consequently, the plastisphere has emerged as an ecological and health concern because of its complex interactions and potential environmental impacts.

Critically, the plastisphere has been identified as a reservoir and potential vector for public health and environmental risks, concentrating pathogenic bacteria, antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), and virulence factors (VFs)[15,16]. These biofilm communities can facilitate horizontal gene transfer mediated by mobile genetic elements (MGEs) and enhance the persistence of resistant or pathogenic strains in the environment[17,18]. However, under natural conditions, the surface properties of plastics change dynamically through aging, weathering, and biofilm development, leading to shifts in the microbial community's composition and functional potential. How these alterations influence the abundance and diversity of ARGs, VFs, and pathogens remains a critical yet insufficiently studied issue. Previous studies have demonstrated that ARGs and VFs often coexist and exhibit significant correlations in various environments[19,20]. For instance, in soil and wastewater systems, ARGs and VFs are frequently co-located on the same microbial hosts or MGEs, suggesting potential co-selection and synergistic propagation mechanisms[21−23]. However, whether similar associations occur within the plastisphere, particularly on biodegradable plastics, remains largely unknown. The interactions between the plastisphere and the genetic determinants of ARGs and VFs, as well as their potential coupling patterns, have not been systematically characterized, leaving a significant gap in understanding their ecological and health implications.

The plastisphere plays an important role in ecosystems, and its formation and persistence are closely related to the degradability and material characteristics of plastic polymers[20,24]. Conventional non-biodegradable plastics (non-BPs), such as polystyrene (PS) and polyvinyl chloride (PVC), exhibit strong chemical stability, resisting microbial degradation and persisting in natural environments for decades[25]. PS is a hydrophobic polymer with a high surface area that can adsorb organic pollutants. In contrast, PVC contains chlorine atoms in its polymer backbone, which enhance its chemical resistance and environmental persistence[26,27]. These characteristics lead to long-term environmental accumulation and continuous production of microplastic fragments. The stable surfaces of non-BPs not only adsorb co-occurring environmental pollutants, such as heavy metals and organic pollutants, but also facilitate the formation of long-lived plastisphere biofilms that can serve as persistent and mobile microbial habitats, potentially enriching and spreading specific pathogenic bacteria and ARGs[21,28]. Recently, biodegradable plastics (BPs) such as polylactic acid (PLA) and polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) have been developed as potential alternatives to non-BPs, because BPs can be decomposed by microorganisms under favorable environmental conditions[29]. However, BPs exhibit distinct environmental behaviors from non-BPs. Their accelerated degradation would generate smaller fragments, and their continuously degrading surfaces would promote more rapid, unstable microbial succession[30,31]. This process could inadvertently create a nutrient-rich niche that fosters the proliferation of opportunistic pathogens and enhances genetic exchange. However, whether this transient process mitigates or, paradoxically, exacerbates the risks associated with ARGs and pathogens compared with the long-term presence of non-BPs remains a critical and largely unaddressed question.

To address these knowledge gaps, we conducted an 88-day in situ incubation experiment in a natural tidal river, tracking the temporal dynamics of plastisphere communities on a representative BP (PLA) and two common non-BPs (PVC and PS) under realistic natural aquatic environmental conditions. Unlike previous studies that have examined the plastisphere's behavior in isolated or simplified settings, this work uniquely integrates temporal metagenomic profiling with in situ environmental monitoring to uncover plastic-type-specific patterns in the enrichment of pathogenic bacteria, ARGs, and VFs. Employing time-series metagenomic sequencing and genome-resolved analysis, this study aimed to (1) determine if the degradation of PLA corresponds with a verifiable transient peak of pathogenic bacteria and ARGs, (2) assess whether non-BPs evolve into persistent hotspots for ARGs and MGEs over time, and (3) identify the key microbial hosts of these risk-associated genes using metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) to uncover the co-occurrence patterns between ARGs and VFs. By elucidating these distinct, material-specific risk mechanisms, this research provides critical insights for a more comprehensive, lifecycle-aware environmental risk assessment of current and future plastic polymers.

-

The in situ experiment was conducted in a tidal river (2 m depth) in Shanghai, China, a tributary of the Huangpu River (31°223" N 121°27'32" E). To examine microbial communities' establishment on different plastic polymers, three polymers were selected as experimental substrates: PVC, PS, and PLA. PVC and PS were chosen as representative non-BPs because of their widespread use and persistence in aquatic environments, though they also differ in their physicochemical properties. Specifically, PVC was polar and chemically resistant because of the chlorine atoms in its backbone, whereas PS was nonpolar and highly hydrophobic[32,33]. PLA was selected as a representative biodegradable plastic (BP) because of its wide application and good degradability[34,35]. The PVC, PS, and PLA used in this study were all obtained from single-use items, including document folders, take-out boxes, and plastic bags. Each was cut into 2 × 2 cm2 squares and rinsed with ultrapure water.

Considering the hydrodynamic conditions and microbial activity, the plastic samples were suspended 30 cm below the water surface using nylon mesh bags (15 cm × 20 cm, 40-mesh size) attached to floating frames. This depth maintained moderate dissolved oxygen (DO) levels and prevented intense solar exposure, promoting biofilm formation[36]. Plastic and river water samples (W) were collected on Days 30, 40, 58, 66, and 88 to capture the temporal dynamics of colonization. The nylon bags were gently rinsed with river water on Day 40 to remove excessive sediment without disturbing the biofilms. All collected water samples were stored in sterile containers at –20 °C for further analysis.

DNA extraction and sequencing

-

Collected plastic samples retrieved after exposure were rinsed three times with sterile water to remove loosely attached particles, whereas the water samples were filtered through 0.22-μm membranes. Both the membranes and plastic pieces were transferred into sterile bead-beating tubes. DNA was extracted using the PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (MoBio, USA) according to the protocol of the manufacturer. DNA purity and concentration were verified by a microvolume spectrophotometer, and the extracted DNA samples were stored at –20 °C until metagenomic sequencing was conducted by Shanghai Meiji Biological Co., Ltd.

Metagenomic assembly and binning

-

Paired-end metagenomic sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeq platform (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA)[37]. Raw reads were quality-controlled using Fastp (v.0.20.0)[38] and aligned by BWA (v. 0.7.9a)[39]. Clean reads were assembled using MEGAHIT (v.1.1.2), and contigs with ≥ 500 bp were retained[40]. CD-HIT (v.4.6.1) was used to construct a nonredundant gene catalog, and SOAPaligner (v. 2.21) was used to map reads and estimate genes' abundance[41]. Taxonomic annotation was performed using the NR database[16].

Metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) were generated with MetaWRAP (v.1.3.2) using the CONTACT, MaxBin2, and MetaBAT binning approaches[42]. Bin refinement integrated the results and retained bins with ≥ 70% completeness and ≤ 5% contamination. The quant_bins procedure estimated the scaffold abundance and relative abundance. Taxonomic annotation of the MAGs was carried out using GTDB-tk (v. 2.1.1)[43].

Determination of ARGs, VFs, and MGEs

-

To comprehensively assess the relative abundance of ARGs and MGEs within the total microbial community, sequencing-based analyses were first conducted. Specifically, high-quality metagenomic reads that passed quality control were analyzed using ARGs-OAP (v.3.2.3) and its integrated database for the quantification and functional annotation of ARGs and MGEs within the samples[44].

To identify potential pathogenic hosts carrying these risk genes and to determine the key species–gene combinations constituting the core risk, a genome-resolved analysis based on MAGs was subsequently performed. Bins that were functionally annotated by Prokka (v.1.14.6) were aligned against the ARG and MGE databases defined by ARGs-OAP and the Virulence Factor Database (VFDB), respectively, using DIAMOND (e-value ≤ 1e–5, identity ≥ 70%)[45−47].

The selected bins that carried both ARGs and VFs located on the MGEs were classified as "high-risk" microorganisms, indicating a potential for disseminating resistance and virulence traits. Their relative abundances were quantified to evaluate ecological health risks across samples. By quantifying the relative abundance of high-risk MAGs and their associated key genes in the samples, the key species and genes contributing to significant ecological health risks were identified.

Statistical analysis

-

All statistical analyses and visualizations were performed in R (v.3.3.2) and Origin Lab 2021. Statistical analyses were conducted to assess variations in the community structure and identify key risk associations. The β diversity of microbial communities at the genus level was visualized using principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity matrices. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. Correlation analysis was performed among microbial species, ARG subtypes, and MGE subtypes. Network diagrams were constructed using Gephi based on significantly correlated pairs (|R| ≥ 0.95, p < 0.05).

-

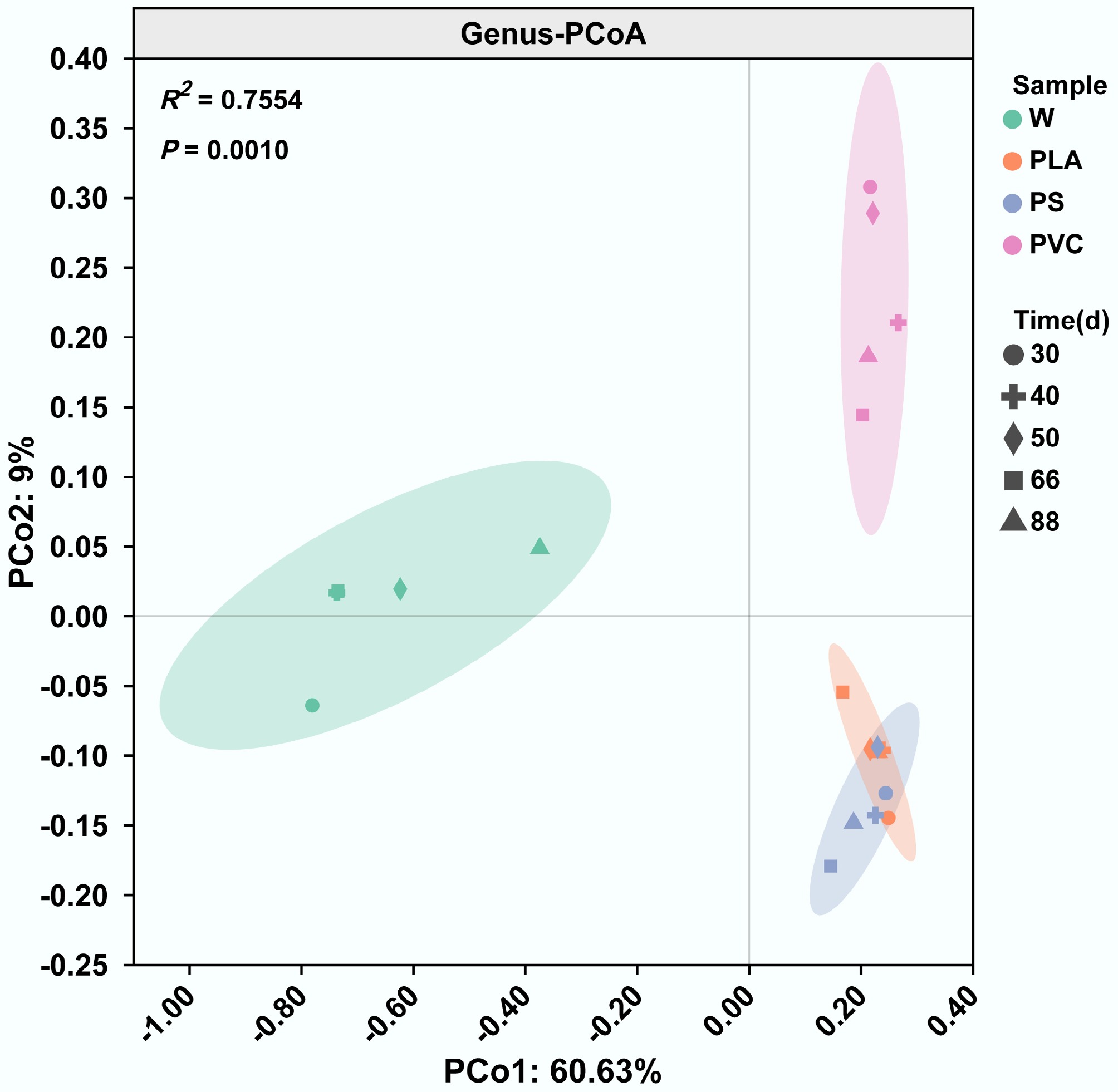

In order to systematically assess the ecological health risks posed by different types of plastics, this study sought to determine whether different plastic polymers create unique microbial habitats in a natural riverine environment. A PCoA of the microbial community's composition at the genus level unequivocally demonstrated that all three plastic types fostered distinct biofilm communities, significantly different from that in the surrounding river water (Fig. 1). This confirms the pronounced niche effect of the plastisphere, where plastic surfaces selectively recruit and cultivate specific microbial consortia in contrast to the river. In the two-dimensional ordination space, microbial communities on the surfaces of PLA, PS, and PVC were significantly separated from those in the river water, demonstrating that all three plastic types were selectively enriched in specific microbial taxa from the aquatic environment and developed distinct biofilm architectures[48]. Although PLA and PS differ in their chemical properties, their microbial communities showed a partial overlap in the PCoA plot, suggesting convergent enrichment of specific colonizing taxa. Notably, although PVC clustered closely with PLA and PS along principal coordinate (PCo) 1, it showed clear separation along PCo2, indicating unique enrichment patterns for specific phylogenetic groups. These findings demonstrate that different plastic types formed unique microbial community structures through selective enrichment processes[49], with the material properties significantly influencing the community's composition[50].

Figure 1.

Distinct microbial community structures assemble on plastic surfaces. Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity of microbial communities at the genus level. Each point represents a sample from either river water (W) or the plastisphere of polylactic acid (PLA), polystyrene (PS), or polyvinyl chloride (PVC). Ellipses represent the 95% confidence interval for each group.

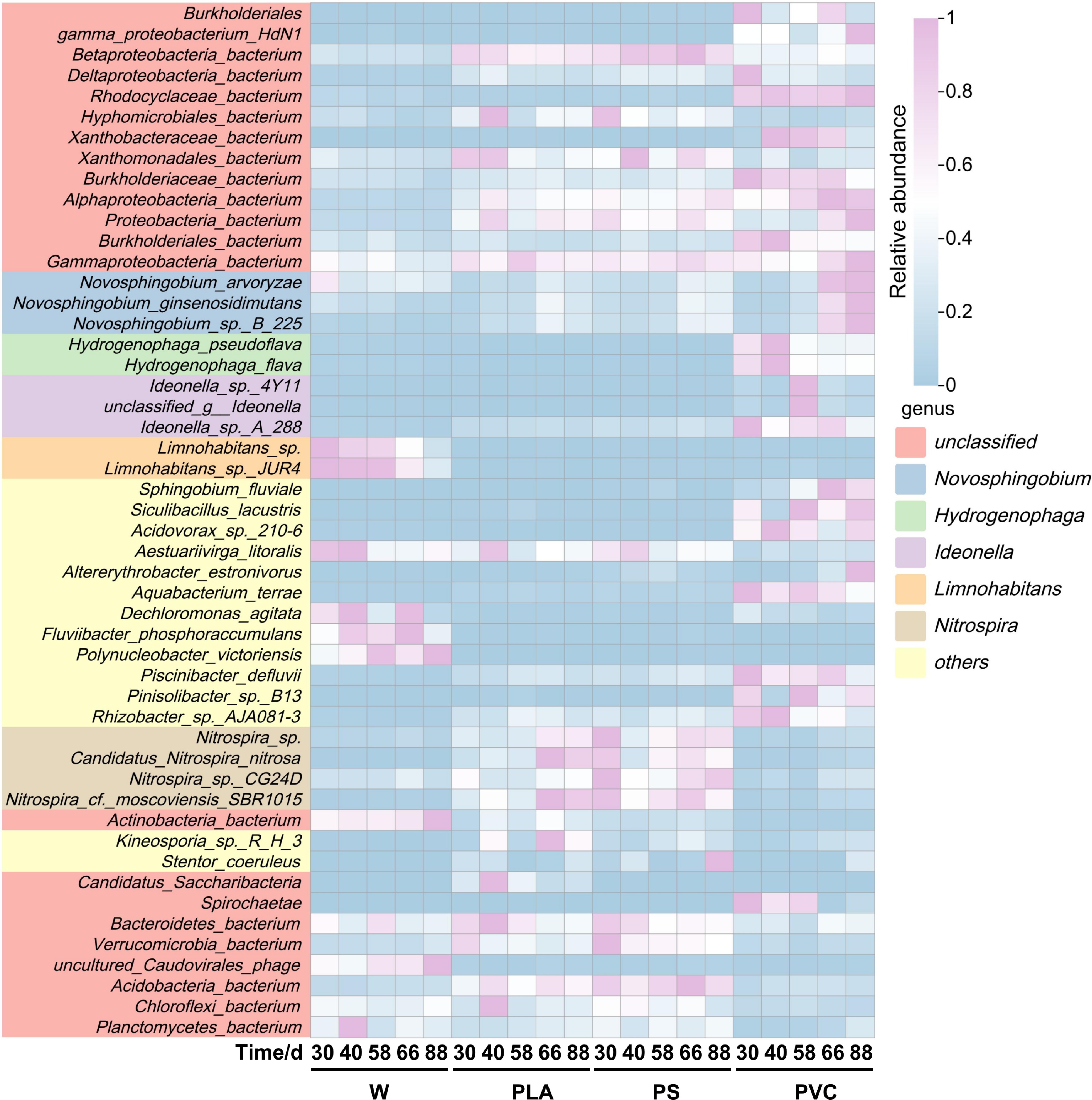

Looking more closely into the specific taxa driving these community differences, we identified key colonizers that thrived on the plastic surfaces. Three taxa, Limnohabitans sp., uncultured_Caudovirales_phage, and Burkholderiales_bacterium_JOSHI_001 were significantly enriched in the plastisphere. Among these, Limnohabitans sp. and Burkholderiales_bacterium_JOSHI_001 belong to the phylum Proteobacteria, whereas uncultured_Caudovirales_phage was classified as Uroviricota (Fig. 2). From a functional perspective, the enrichment of Limnohabitans sp. (affiliated with the genus Limnohabitans) may be attributed to its distinctive ecological adaptations. This strain harbors motility-related genes (e.g., flagellar assembly genes) and chemotaxis genes (e.g., cheABRW and mcp), allowing active movement toward and colonization of plastic surfaces[51]. The genome of Limnohabitans sp. encodes a high-affinity adenosine triphopshate (ATP)-binding cassette transporter that efficiently scavenges dispersed organic and inorganic nutrients (e.g., phosphates and amino acids) from the environment, thereby supplying resources for synthesis and accumulation of the biofilm matrix[52].

Figure 2.

Heatmap showing the relative abundance of the top 50 most abundant microbial species. Rows are clustered according to species abundance profiles, and columns are clustered by sample. The color key indicates the log-transformed relative abundance.

Furthermore, Limnohabitans exhibits stable gene expression and rapid growth under oligotrophic conditions, facilitating early niche occupation during colonization. Strain-level microdiversity also allows it to adapt to local environmental variations, collectively promoting the initiation and stable development of microbial biofilms[53]. Notably, although plastisphere-enriched taxa demonstrated some specificity, the predominant phyla, Proteobacteria and Uroviricota, were also abundant in river water communities[54], alongside other prominent phyla such as Acidobacteria. This pattern indicates that microorganisms enriched in the plastisphere were not independent of the background aquatic community but originated through selective colonization and amplification from the water, reflecting the screening effect on microbial assembly of plastic surfaces as specific ecological niches[55]. While establishing this unique community structure, we also observed several opportunistic pathogenic genera, including Acinetobacter and Vibrio, within the plastisphere, prompting a deeper investigation into the specific health risks associated with each plastic type.

Divergent risk trajectories of ARGs and MGEs

-

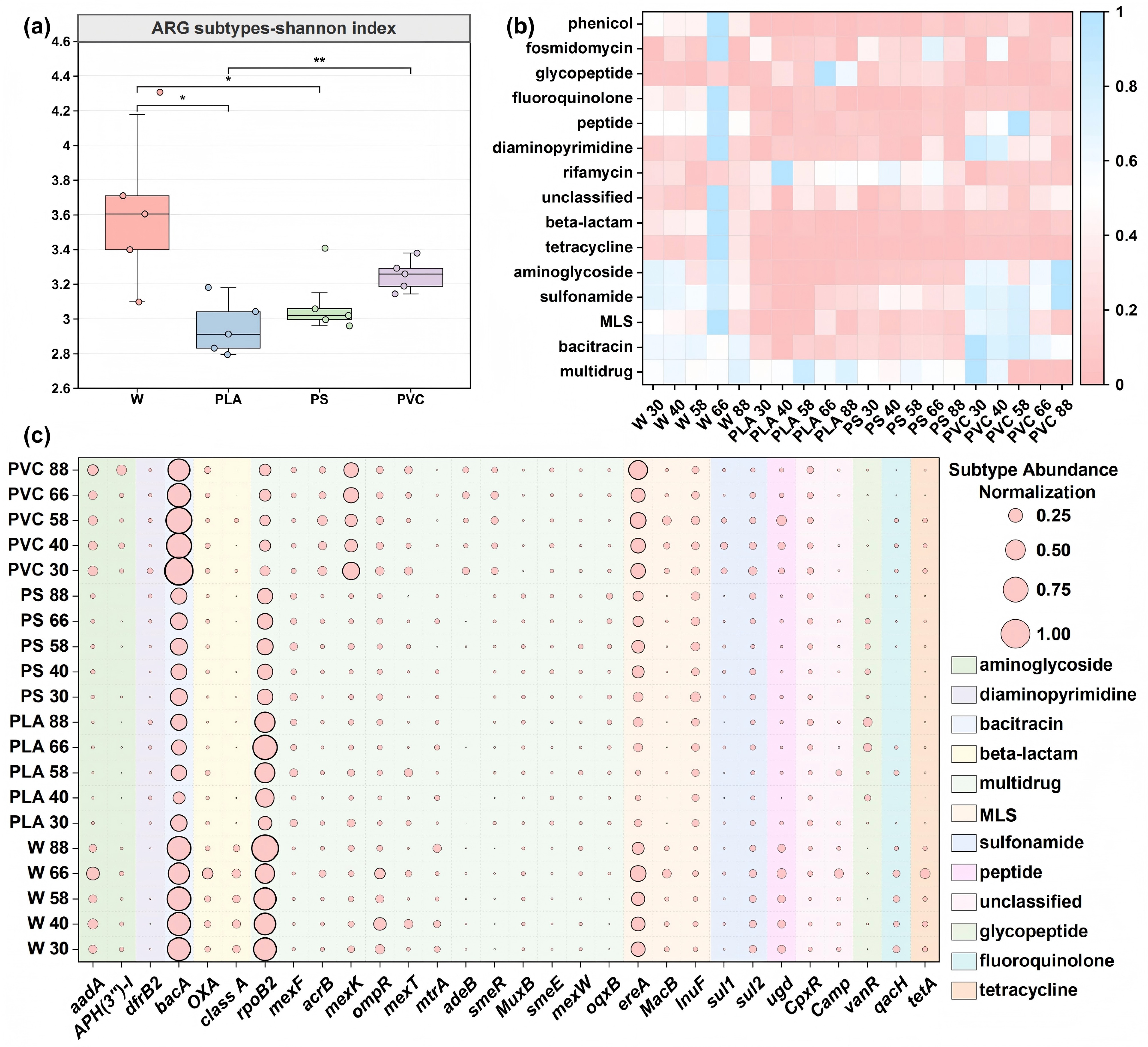

To clarify the role of plastic types in shaping microbial communities, we further analyzed their effects on the enrichment of functional genes, especially ARGs and MGEs, to reveal their potential risk trajectories. After establishing distinct microbial niches, it was important to verify the central hypothesis that BPs and non-BPs foster fundamentally different risk profiles over time. The diversity of ARG subtypes on the surfaces of the three plastics was lower than that in the river water, indicating that the plastic environment's resistance genes were selectively enriched, leading the community to exhibit a specific resistance phenotype[56]. Regarding alpha diversity, Fig. 3a shows that the Shannon index of the PLA group was the lowest (about 3.3), followed by the PS group (about 3.5). The diversity of the PVC group (about 3.7) was slightly higher than that of PLA and PS, but the difference was not statistically significant. These results indicate that plastic type significantly influences ARGs' diversity, likely through material-specific selective enrichment of ARGs[57].

Figure 3.

Dynamics of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) reveal distinct risk profiles for different plastic types. (a) Alpha diversity (Shannon index) of ARG subtypes across sample groups. Boxplots display the median and interquartile range. (b) Relative abundance of major ARG types across all samples over the 88-d incubation. Abundances are normalized as copies per 16S rRNA gene. (c) Heatmap of the relative abundance of the top 30 most abundant ARG subtypes. The color intensity corresponds to the z-score normalized abundance of each subtype across all samples.

In this study, the dynamic changes and diversity of ARG types and subtypes were systematically analyzed to explore the occurrence characteristics and differences of ARGs across different plastics. The concentration of ARGs in river water was generally higher than that in the plastic environment, indicating that river water is an essential reservoir for ARGs (Fig. 3b)[58]. According to the ARG-OAP platform, 374 ARG subtypes out of 32 major ARG types were identified. Previous studies have also reported high absolute abundances of ARGs on plastic debris[24].

Of the 32 ARG subtypes identified, most were assigned to multidrug-, acitracin-, and Macrolide-Lincosamide-Streptogramin (MLS)-resistant genes in the plastisphere, followed by genes encoding resistance to sulfonamide and rifamycin in PLA and PS, and those for resistance to aminoglycoside and sulfonamide in PVC. Multidrug resistance genes exhibited the highest abundance among all detected ARGs (Fig. 3b), with a peak at 30 d in PVC (0.984 copies/16S rRNA genes), suggesting substantial dissemination potential[59]. PVC showed rapid but transient enrichment of bacitracin, MLS, and aminoglycoside resistance genes during early exposure, which correlated with the acute toxicity of leaching additives (e.g., phthalates) that selected for efflux pump-mediated multidrug-resistant bacteria[60]. In contrast, PS demonstrated stable and sustained enrichment of rifamycin and other resistance genes, attributable to its persistent surface microenvironment and its capacity to adsorb hydrophobic contaminants, thereby maintaining continuous selective pressure. Compared with the persistent, high-risk state on non-BPs, a transient, acute-risk phase was found for PLA. PLA displayed phase-dependent resistance gene dynamics: initial suppression during early exposure, followed by a marked peak in multidrug resistance (0.852 copies/16S rRNA genes) and elevated glycopeptide resistance during the mid-degradation phase. These patterns imply that degradation of PLA facilitates biofilm development and horizontal gene transfer, potentially activating high-risk resistance mechanisms. Subtype-specific analysis further revealed material-driven selection: PVC transitioned from efflux pump genes (mexK, acrB) to enzymatic resistance determinants (sul1, APH(3''-I)), whereas PS maintained a consistent enrichment in MacB and sul1, and PLA selectively accumulated mexF, mexT, and vanR during its degradation (Fig. 3c).

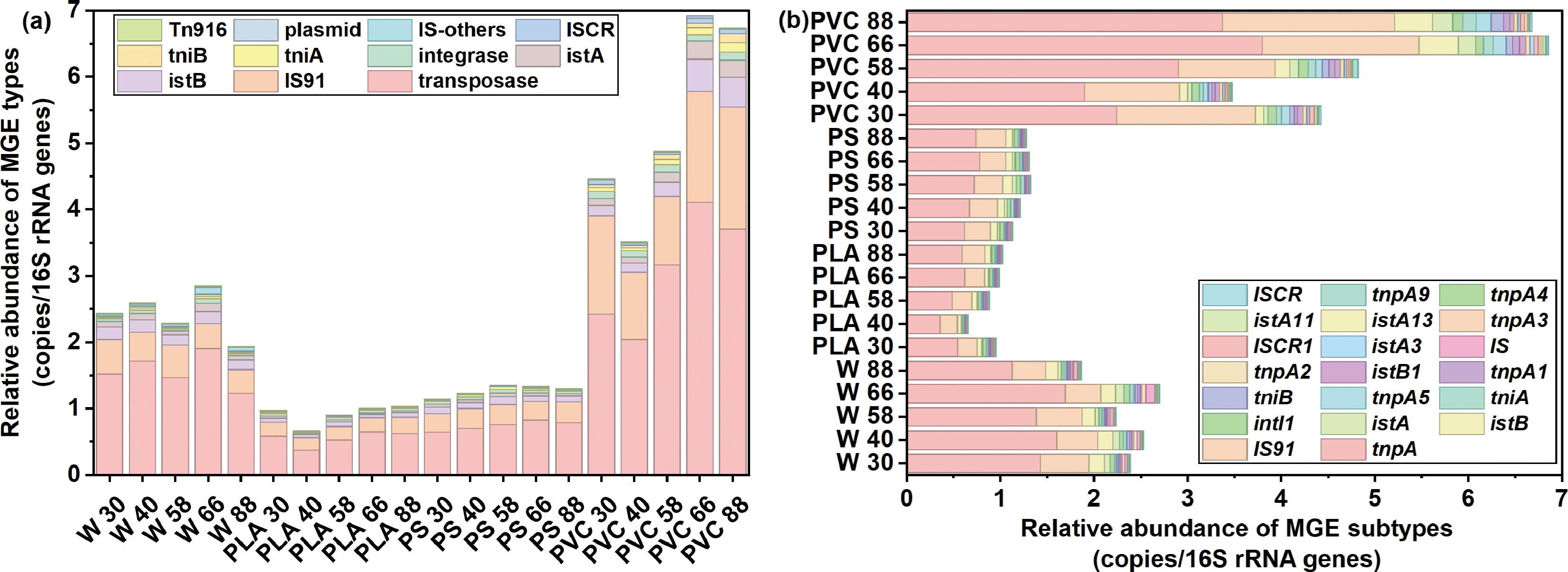

These ARGs can be widely disseminated among bacteria via MGEs, highlighting the need to further investigate the role of MGEs in facilitating the environmental transmission of ARGs. The overall abundance of MGEs in PVC samples was significantly higher than in other plastic types (Fig. 4a). For instance, the abundance of transposase in PVC ranged from 2.428 to 4.109 copies/16S rRNA genes, and IS91 abundance ranged from 1.016 to 1.838 copies/16S rRNA genes, substantially exceeding those in PLA and PS samples. These results indicate that PVC may serve as an essential reservoir of MGEs in the environment, potentially enhancing horizontal gene transfer among microorganisms. Given the crucial role of MGEs in ARGs' dissemination[61], the presence of PVC materials could significantly facilitate the spread of ARGs in environmental settings.

Figure 4.

Relative abundance of (a) types and (b) subtypes of mobile genetic element (MGE) in river water and plastispheres.

In contrast, MGEs were relatively low in both PLA and PS. Transposase levels in PLA ranged from 0.378 to 0.651 copies/16S rRNA genes, whereas PS samples showed transposase abundances between 0.612 and 0.828 copies/16S rRNA genes. These results suggested that PLA and PS have a weaker capacity for adsorption of and enrichment in MGEs, consequently exhibiting limited potential to promote the transmission of ARGs.

Further analysis of the top 20 MGE subtypes revealed significant differences in their abundance and distribution patterns among different plastic types (Fig. 4b). The tnpA subtype, for example, was consistently more abundant in PVC samples compared with PLA and PS, possibly attributable to PVC's high chlorine content and strong hydrophobicity, which may enhance its adsorption and enrichment capacity for specific MGE subtypes like tnpA. Additionally, the istA subtype showed relatively higher abundance in PS samples but lower levels in PVC samples, potentially related to the relative hydrophilicity of PS, leading to distinct MGE subtype adsorption and enrichment profiles across materials.

Therefore, this study demonstrates that the plastic type significantly influences MGEs' composition and abundance, with distinct MGE distribution characteristics observed across different plastic materials. Because of their elevated MGE levels, PVC plastics may play a more substantial role in promoting the environmental dissemination of ARGs.

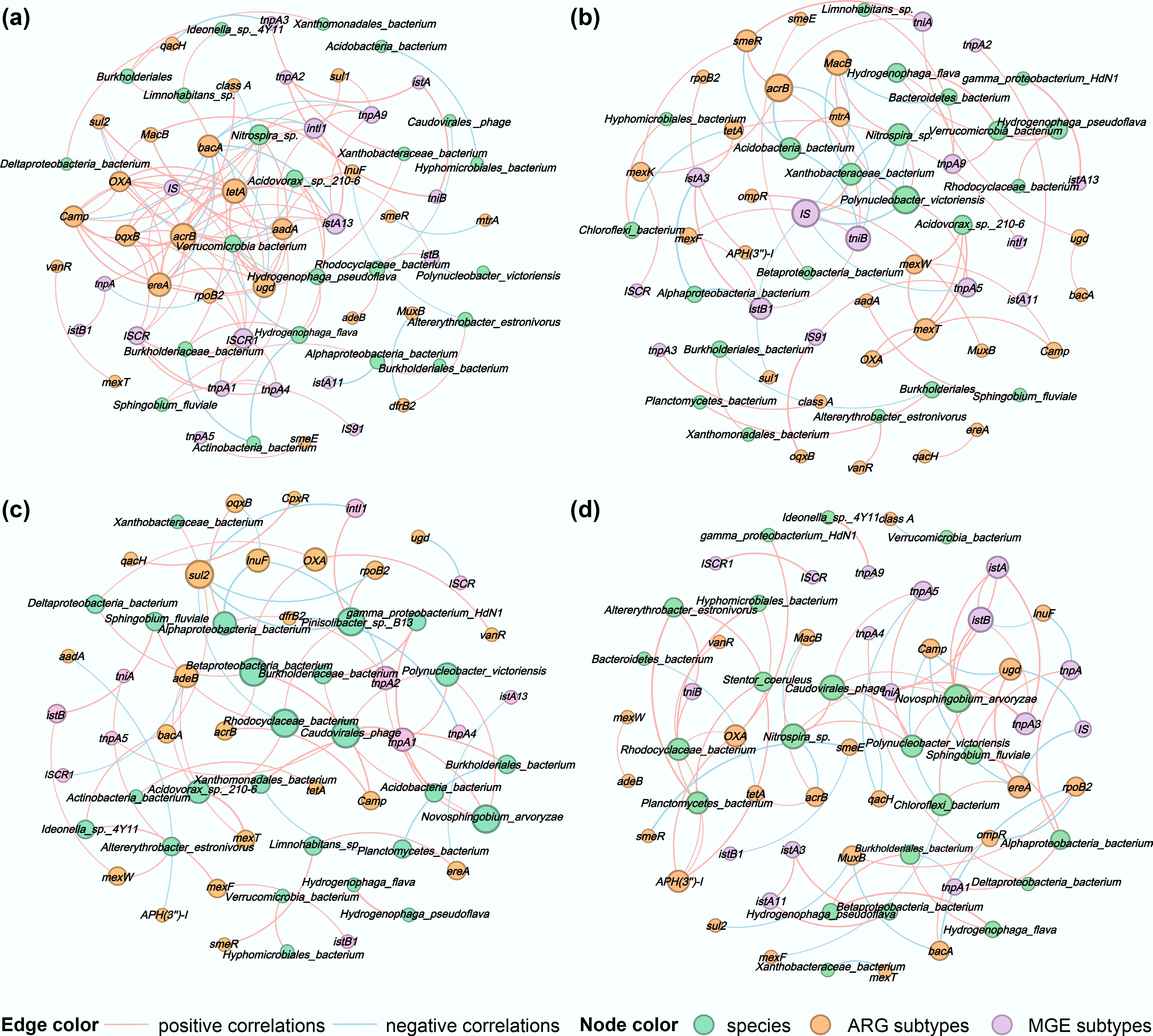

To elucidate the contribution of microbial communities to variations in ARG and MGE subtypes, correlation analyses were performed between the top 30 most abundant species and ARG subtypes, as well as between the top 20 most abundant MGE subtypes. Network diagrams (Fig. 5) were constructed using groups with correlation coefficients |R| ≥ 0.95 and p < 0.05.

Figure 5.

Correlation network diagrams of surface microorganisms at the species level, ARG subtypes, and MGE subtypes for (a) water, (b) PLA, (c) PS, and (d) PVC. The nodes were colored by species, ARG, and MGE subtypes, and node size was ranked by degree (number of connections). The pink and blue edges represent positive and negative correlations, respectively. The thicker the line, the stronger the correlation.

The number of potential host species identified in the water samples and on the surfaces of PLA, PS, and PVC was 28, 24, 26, and 22, respectively. A relatively higher number of ARG subtypes showed significant positive correlations with the hosts in the PS and PLA groups. In the PS group, Limnohabitans sp. exhibited strong positive correlations with smeR and ereA, whereas the Betaproteobacteria bacterium showed strong positive correlations with OXA and acrB. However, the Rhodocyclaceae bacterium and Pinisolibacter sp. B13 were strongly negatively correlated with the sul2 gene (Fig. 5c). In the PLA group, Acidovorax sp. 210-6 demonstrated strong positive correlations with OXA, mexT, and mexW, whereas Xanthobacteraceae showed a significant negative correlation with MacB (Fig. 5d).

In contrast, the potential for horizontal gene transfer was more prominent in the PVC group, where species correlated positively with 10 MGE subtypes, followed by the water group, which correlated positively with 7 MGE subtypes. Although the PLA and PS groups harbored the most diverse ARG subtypes, they displayed the fewest direct associations with MGE subtypes (six and five, respectively), suggesting that their ARG subtypes' dissemination mechanisms may differ or rely on specific MGE subtypes.

Therefore, further investigation into the correlations between ARGs and MGEs revealed that the water group showed the strongest positive correlations. The aminoglycoside resistance gene aadA co-occurred not only with multiple ARG subtypes (including OXA, acrB, MacB, and tetA) but also showed significant positive correlations with MGE subtypes such as the integrase intI1 and transposase tnpA1. Concurrently, the efflux pump gene acrB also showed strong positive correlations with MGE subtypes, such as the transposase ISCR1. These results indicate that ARG subtypes and MGE subtypes form a dense synergistic network in the water group, facilitating the dissemination of multidrug resistance.

In the PLA group, ARG subtypes and MGE subtypes also exhibited significant positive correlations. The tetracycline resistance gene tetA showed strong positive correlations with the integrase intI1 and transposase istA3, whereas the efflux pump gene acrB was significantly associated with the transposition-related genes tniA and tniB. Particularly noteworthy, gamma_proteobacterium_HdN1 showed an extremely strong positive correlation with the transposase istA13, further confirming the important role of specific microbial species in promoting the co-occurrence of ARGs and MGEs.

In comparison, the correlation patterns between ARG and MGE subtypes in the PVC and PS groups were more specific. In the PVC group, although strong positive correlations existed between MGE subtypes such as istA and tnpA3, negative correlations were observed between acrB and MacB in specific species. In the PS group, sul2 showed a significant negative correlation with intI1, and ugd also exhibited a negative correlation with ISCR. These negative correlations may restrict the dissemination range of specific ARGs.

Overall, significant positive correlations were observed between ARGs and MGEs, indicating that horizontal gene transfer is a key mechanism driving the dissemination of antibiotic resistance in these environments. However, the strength and patterns of these correlations demonstrated notable differences among the groups.

Genome-resolved analysis identifies high-risk pathogenic hosts

-

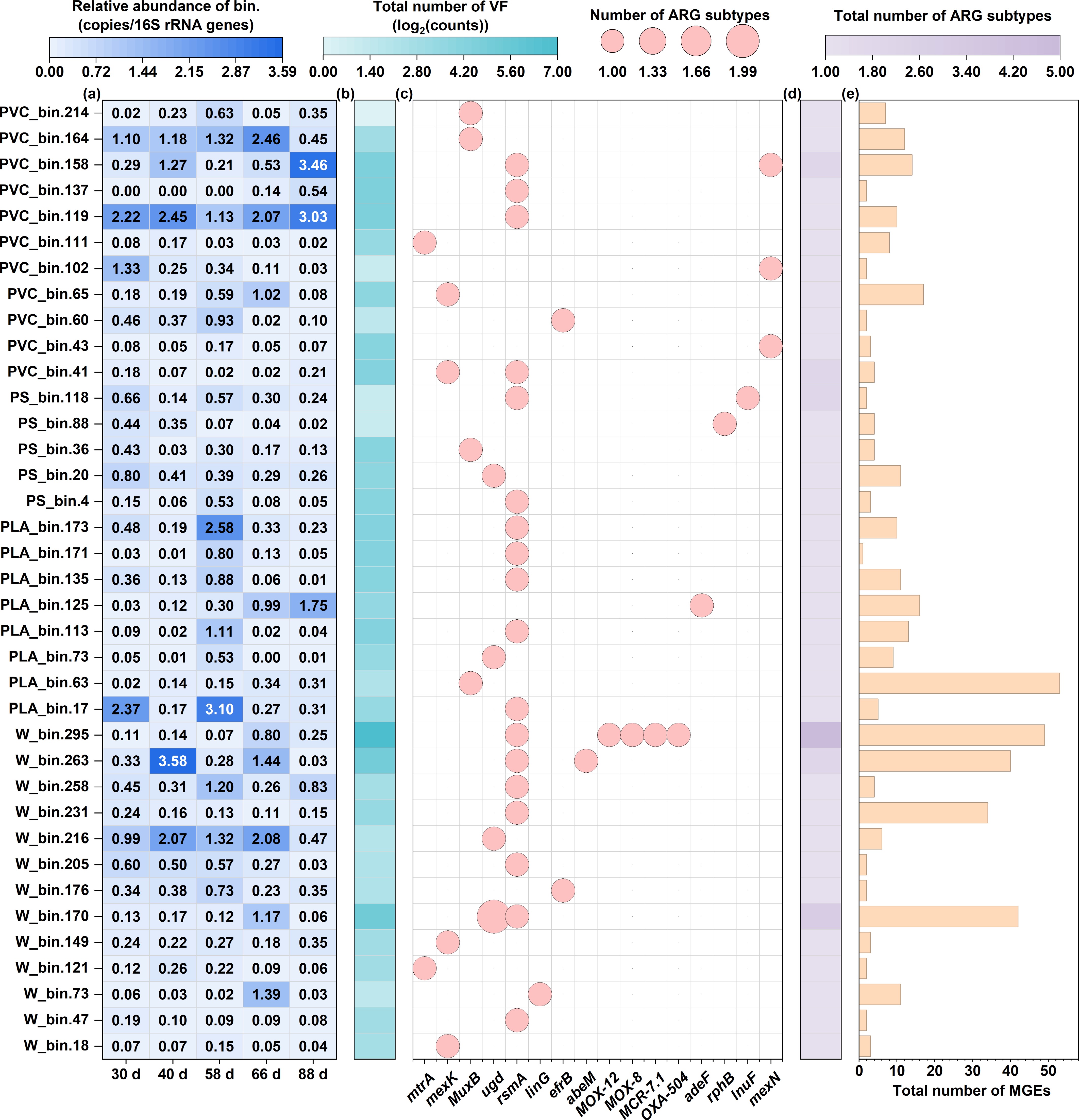

Building on the community and functional gene profiles, we employed a genome-resolved approach to pinpoint the specific microbial hosts that carry both ARGs and VFs, thereby identifying high-risk pathogenic bacteria. The taxonomic annotation of the bins is presented in the Supplementary Table S1. By reconstructing 37 high-quality MAGs, we could directly link ARGs and VFs to individual microbial populations, revealing the mechanistic basis of the observed risks. The pathogenic host bacteria primarily belonged to the phyla Proteobacteria, Desulfobacterota, and Actinobacteriota. The overall genomic abundance in the water group remained stable, although some strains, such as W_bin.216, exhibited significant increases at 40 and 66 d, indicating strong environmental adaptability. In the PLA group, genomic abundance fluctuated considerably at different time points, with PLA_bin.17 reaching its peak abundance of 3.10 at 58 d, suggesting that the PLA's degradation process may have created phase-specific optimal growth conditions for specific microorganisms. Genomic abundance in the PS group generally remained low and showed gradual changes over time. In contrast, the PVC group exhibited a polarized pattern of genomic abundance, with some strains, such as PVC_bin.119, showing a significant increase in abundance at 88 d, maintaining a higher level thereafter (Fig. 6a).

Figure 6.

The genome-centric analysis reveals the distribution of risk-associated genes across 37 high-quality MAGs. (a) Relative abundance heatmap of each MAG across all samples. (b) Total count of VFs identified per MAG. (c) Presence/absence matrix of ARG subtypes across the MAG. (d) Total count of unique ARG subtypes identified per MAG. (e) Total count of MGEs identified per MAG, indicating the potential for horizontal gene transfer.

Significant differences were observed in the number of VFs among the river water samples, with W_bin.295 having a total of 112 VFs, far exceeding that of other strains, indicating the presence of potentially high-pathogenicity strains in the river water[62]. The total VFs in the PLA samples were generally at moderate levels (5–21), with no anomalously high values. The PS samples exhibited uniformly low VF counts (2–18), with PS_bin.88 and PS_bin.118 having a total of only two VFs. Conversely, the PVC samples showed a higher overall VF count, with PVC_bin.119 and PVC_bin.158 having totals of 25 and 24 VFs, respectively, suggesting that the PVC environment may be rich in potential pathogenic microorganisms (Fig. 6b).

A total of 16 types of ARGs were detected, with their distribution showing significant differences across the treatment groups (Fig. 6c). The rsmA gene exhibited the broadest distribution, being detected in the water group (7 strains), PLA group (5 strains), PS group (2 strains), and PVC group (4 strains), with a total of 18 strains showing detection, indicating its widespread occurrence among environmental microorganisms. The mexK and MuxB genes were identified in five and four strains, respectively, predominantly in the W and PVC groups. Notably, several ARGs exhibited a distinct group-specific distribution pattern, with the β-lactamase genes MOX-12, MOX-8, MCR-7.1, and OXA-504 detected exclusively in W_bin.295, which carried a total of five ARGs, reflecting classic multidrug resistance characteristics. Similarly, the adeF gene was found in the PLA group strain PLA_bin.125, wherease the lnuF and mexN genes were detected exclusively in the PS group strain PS_bin.118 and the PVC group strain PVC_bin.43, respectively. This distribution pattern indicates that different plastic processing environments may select for microorganisms carrying specific resistance mechanisms, with the PLA environment potentially enriching for the adeF resistance gene, and the PVC environment favoring the survival of strains carrying efflux pump genes such as mexK.

Our analysis uncovered compelling evidence of coupled risks, with ARGs and VFs coexisting within the identical microbial genomes, suggesting potential pathogens that are also treatment-resistant. This was most evident in MAGs from the river water (e.g., W_bin.295, carrying 5 ARGs and 112 VFs) and the PVC plastisphere (e.g., PVC_bin.119 and PVC_bin.158), which harbored significant numbers of both gene types (Fig. 6b, d). This co-localization highlights a severe public health risk, as these organisms represent a confluence of pathogenicity and determinants of resistance.

Furthermore, we assessed the potential for horizontal gene transfer by examining the co-occurrence of ARGs and MGEs within these MAGs. The water group exhibited the most complex coexistence pattern of resistance genes and mobile elements, with W_bin.295, with the highest number of ARGs (5) and a very high number of MGEs (49), indicating the strain's significant potential for disseminating multidrug resistance. Similarly, W_bin.170 (3 ARGs, 42 MGEs) and W_bin.263 (2 ARGs, 40 MGEs) also exhibited a strong co-occurrence of ARGs and MGEs, further confirming the risk of horizontal gene transfer in river water environments. In the PLA group, a unique phenomenon was observed where PLA_bin.63, although only carrying ARGs (1), had the highest number of MGEs (53) among all samples, suggesting that this strain could serve as a potential gene transfer vector, capable of rapid dissemination upon acquiring foreign resistance genes (Fig. 6d, e). In comparison, strains in the PS group exhibited low totals of ARGs (1–2) and MGEs (2–11), indicating limited potential for horizontal gene transfer.

In the PVC group, PVC_bin.41 carried 2 ARGs and 4 MGEs, whereas PVC_bin.158 carried 2 ARGs along with 14 MGEs. This "multiple ARGs–multiple MGEs" combination suggests that the PVC environment may facilitate a synergistic effect promoting the accumulation and dissemination of resistance genes. Notably, a positive correlation trend was observed between the number of ARGs and MGEs across the treatment groups, particularly among strains carrying multiple ARGs, which typically also exhibited relatively higher MGEs counts. In summary, our genome-centric investigation provides direct evidence that specific microorganisms, differentially enriched in water and plastic types, act as reservoirs of combined virulence and resistance, with a high potential for mobilization, thereby deepening our understanding of the plastisphere as a formidable environmental health hazard.

High-risk strains possessing combined pathogenicity, antimicrobial resistance, and transmission potential were identified by detecting the co-occurrence of ARGs, VFs, and MGEs in individual MAGs. For instance, MAGs such as PVC_bin.119 and PVC_bin.158 were found to carry multiple ARGs along with numerous VFs and MGEs, demonstrating their potential as high-risk pathogenic reservoirs. Furthermore, the widespread distribution of transposases and other MGEs within these MAGs, particularly in PVC-associated genomes, indicates a heightened potential for horizontal gene transfer of resistance traits. By associating ARGs and MGEs with specific taxa and quantifying their co-occurrence patterns, our analysis provides a mechanistic basis for assessing the plastisphere's role as a reservoir of mobilizable resistance and virulence genes, thereby bridging genetic findings with public health implications.

-

This study provides a comprehensive, in situ investigation into the environmental health risks posed by both BPs and non-BPs, revealing that their threats are not merely different in scale but are fundamentally distinct in nature. The results indicated that plastic surfaces are selectively enriched in specific microbial taxa, thereby establishing unique biofilm ecosystems. Complex co-occurrence patterns were observed among microbial community structures, ARGs, and MGEs in the microplastic plastisphere. Different types of plastics significantly influenced the microbial community's composition, with certain bacteria exhibiting strong multidrug resistance, indicating a potential risk of horizontal gene transfer in riverine environments. Our results suggested that non-BPs and BPs foster two divergent risk trajectories: conventional plastics, such as PVC, establish a persistent risk reservoir that continuously accumulates and harbors high levels of ARGs and MGEs over the long term. In contrast, biodegradable PLA creates a transient but acute risk peak during its degradation, temporarily becoming a hotspot for opportunistic pathogens and select ARGs. The discovery of these distinct pathways overturns the simplistic notion that biodegradability inherently equates to reduced ecological risk. The genome-resolved analysis showed that PVC enriched a greater number of potential pathogenic microorganisms carrying high numbers of VFs and ARGs. Bacterial strains with high ARG and MGE levels were identified in river water, highlighting their role as an important reservoir for ARG transmission. Plastic surfaces, particularly PVC, increase the risk of horizontal gene transfer in the environment by enriching MGEs and ARGs, potentially facilitating the spread of resistance genes with public health relevance. This study provided direct evidence of high-risk microorganisms that couple pathogenicity, resistance, and mobility, suggesting that the plastisphere functions as a hotspot for microorganisms of public health concern. Future work should further clarify how different environmental conditions and polymer types shape the temporal dynamics of plastisphere-associated pathogens and resistance genes, thereby supporting the development of strategies to mitigate their public health and environmental risks.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/biocontam-0025-0026.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Fengying Li: contributed to the study conception and design, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript; Hangru Shen: contributed to the study conception and design, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript; Ruirui Pang: performed material preparation, data collection, and analysis, and contributed to visualization, investigation, and validation; Xueting Wang: performed material preparation, data collection, and analysis; Bing Xie: supervised the project and acquired funding; Min Zhan: contributed to project supervision and manuscript review; Yinglong Su: as the corresponding author, supervised the study, acquired funding, and contributed to manuscript review and editing. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript, reviewed the results, and approved the final manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

This work was financially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 42577422 and 42377410), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, and Shanghai Engineering Research Center of Biotransformation of Organic Solid Waste (Grant No. 19DZ2254400).

-

All authors declare that there are no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work in this paper.

-

The polyvinyl chloride plastisphere acts as a persistent hotspot for antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs).

Biodegradable plastic shows a transient but acute risk peak during its degradation.

Genomes from plastispheres reveal the co-localization of ARGs and virulence factors.

The risk profile of the plastisphere must be assessed across its entire lifecycle, not just its persistence.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Fengying Li, Hangru Shen

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - The supplementary files can be downloaded from here.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li F, Shen H, Pang R, Wang X, Xie B, et al. 2026. Biodegradable and non-biodegradable plastics foster unique regimes of antibiotic resistance and virulence factors in aquatic plastispheres. Biocontaminant 2: e001 doi: 10.48130/biocontam-0025-0026

Biodegradable and non-biodegradable plastics foster unique regimes of antibiotic resistance and virulence factors in aquatic plastispheres

- Received: 01 November 2025

- Revised: 18 November 2025

- Accepted: 02 December 2025

- Published online: 09 January 2026

Abstract: The plastisphere, the biofilm community on plastic debris, is recognized as a reservoir for antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and pathogens. However, the comparative risks of biodegradable (BPs) versus non-biodegradable (non-BPs) plastics remain unclear. This study tested the hypothesis that BPs and non-BPs foster distinct risk trajectories through distinct underlying mechanisms. We investigated microbial succession and the fate of ARGs and virulence factors (VFs) on polylactic acid (PLA, one of the BPs), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and polystyrene (PS) during an 88-day in situ incubation in a tidal river. Metagenomic analysis revealed that PVC consistently harbored the highest abundance of ARGs and mobile genetic elements (MGEs), acting as a persistent hub for resistance, with multidrug resistance genes enriched up to 3.5-fold compared with river water. In contrast, the biodegradable PLA exhibited a distinctly transient risk profile during the mid-degradation stage, creating a hotspot for opportunistic pathogenic genera like Vibrio and Acinetobacter, coinciding with a significant spike in ARGs' abundance. Genome-resolved metagenomics further confirmed the co-localization of ARGs and VFs within high-risk metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs). These findings demonstrate that both BPs and non-BPs pose significant but fundamentally different risks of ARGs and VFs. Risk assessments must therefore consider the entire lifecycle of plastics, accounting for the transient, degradation-driven hazards posed by BPs and the persistent, accumulative threats posed by non-BPs.