-

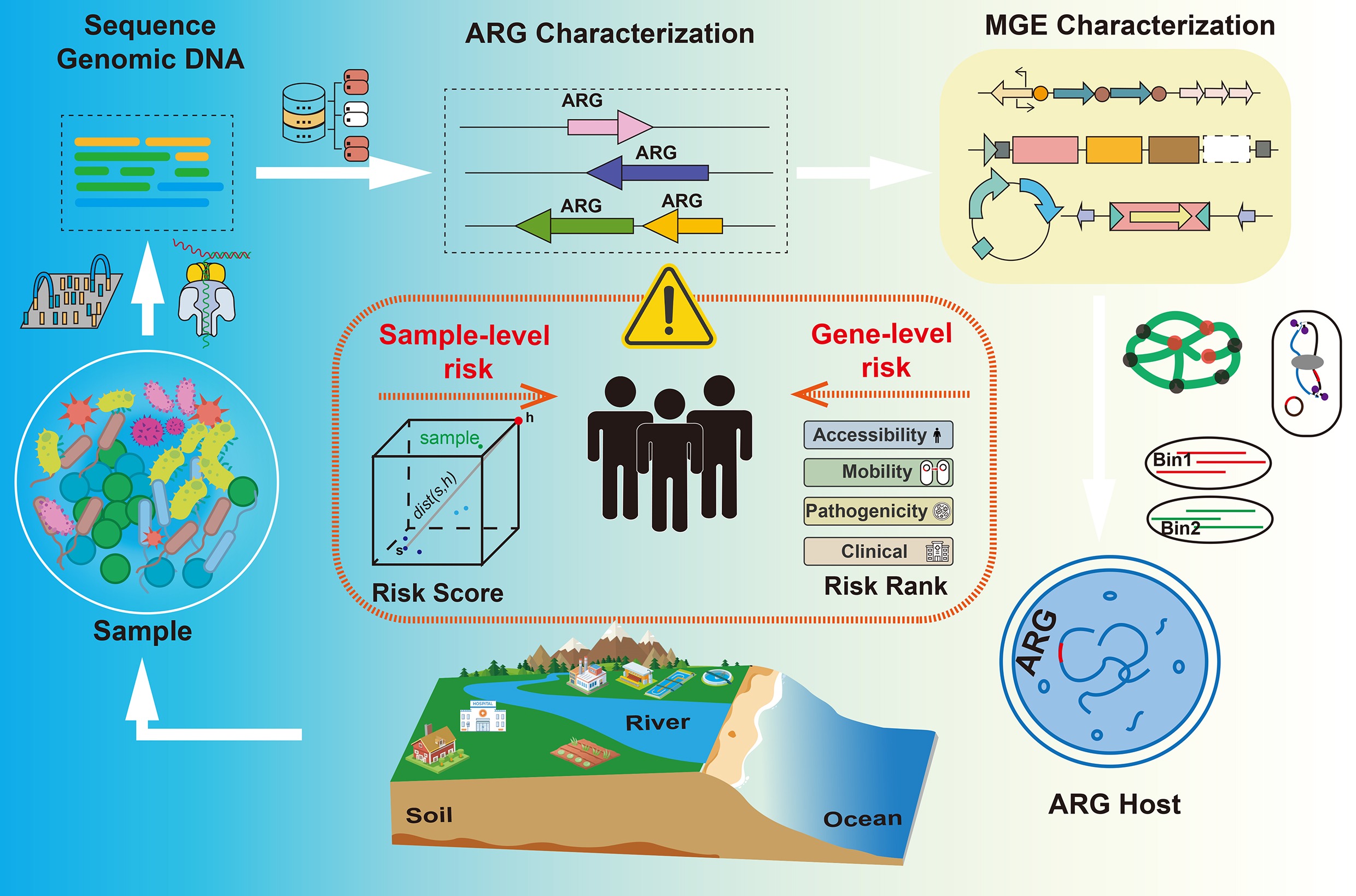

Antibiotic resistance has been recognized as a global threat to the environment and human health, with multidrug-resistant infections contributing significantly to the rising number of deaths worldwide[1,2]. Moreover, antibiotic resistance hinders modern medical advances, making common infections difficult to treat. Antibiotic resistance has been widely detected not only in clinical settings but also across various environments[3]. Its widespread distribution highlights the need to tackle the problem under the One Health framework[4,5]. The One Health concept emphasizes the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health, recognizing that resistant bacteria and genes flow between these domains at local and global scales[4,5]. For example, antibiotic overuse in clinical and agricultural settings contributes to the release of antibiotic residues and the spread of resistant microorganisms. These have made diverse environments reservoirs of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), which may facilitate the transfer of resistance genes to pathogenic bacteria. Consequently, addressing antibiotic resistance requires a multidisciplinary One Health approach that integrates environmental surveillance alongside traditional clinical monitoring.

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) plays a significant role in the rapid dissemination of ARGs[6]. In contrast to vertical gene transfer, HGT facilitates the transfer of ARGs across different bacterial species. This process is mediated by mobile genetic elements (MGEs), including plasmids, transposons, integrons, phages, and integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs), which serve as vehicles for gene transfer[7−10]. The mobility of ARGs via MGEs significantly accelerates the spread of resistance, connecting environmental and clinical resistomes. Consequently, environmental hotspots serve as breeding grounds for novel ARGs, which pathogenic bacteria may subsequently acquire via HGT[11−13]. ARGs located on conjugative plasmids or within transposable elements are generally considered to have a higher potential for dissemination than chromosomal genes[14]. As a result, current surveillance strategies increasingly incorporate the detection and characterization of plasmid-borne ARGs and integron diversity, in addition to profiling ARG abundance and diversity in environmental samples.

In response to the global antibiotic resistance crisis, advanced molecular detection technologies have become essential for identifying ARGs and assessing their associated risks[15,16]. In particular, metagenomic sequencing has greatly improved ARG surveillance by enabling culture-independent analysis of entire microbial communities[17,18]. High-throughput second-generation sequencing remains widely used for profiling ARG diversity and abundance in complex samples. Shotgun metagenomic sequencing of DNA extracted directly from samples such as water, soil, air, or feces enables the detection of ARGs in both culturable and unculturable bacteria, providing a comprehensive overview of the resistome profile[15,19]. However, the short read lengths of second-generation sequencing often impede the reconstruction of complete ARG loci or the determination of their genetic context, such as their association with MGEs or identification of hosts[20]. To overcome these limitations, third-generation (long-read) sequencing platforms have been increasingly employed, such as Oxford Nanopore and PacBio[21,22]. These technologies can span entire ARG regions along with flanking sequences, providing information for host or plasmid inference. In parallel, advances in assembly algorithms, binning strategies, and proximity ligation methods have enhanced the resolution of host-ARG associations[23−25]. Additionally, specialized bioinformatics pipelines supported by curated reference databases have been developed to accurately identify and classify ARGs[26,27]. These tools can even detect novel or divergent resistance gene variants[28]. These developments have also enabled quantitative frameworks for assessing the public health relevance of ARGs, based on factors such as mobility, host pathogenicity, and clinical relevance[29].

This review summarizes current sequencing technologies and bioinformatics pipelines for detecting and quantifying antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) in metagenomic datasets. It also examines recent technical innovations and conceptual developments, emphasizing how metagenomics has broadened detection capabilities and enhanced understanding of ARG-host associations and the ecological risks associated with resistance genes. While previous reviews have addressed individual aspects of ARG research in environmental contexts, such as sequencing strategies or database development, few have integrated these components within a unified framework. This review addresses this gap by integrating ARG detection, host identification methods, quantification strategies, and risk assessment into a comprehensive synthesis. By consolidating these topics, the review offers a thorough overview of methodological and analytical advances in ARG investigation within environmental research.

-

The development of DNA sequencing technologies has significantly deepened the understanding of microbial taxonomy and functions in complex environmental samples. Since the introduction of first-generation sequencing by Frederick Sanger in 1977, the field has undergone a series of technological revolutions[30]. For example, the emergence of second- and third-generation sequencing over the past decades has significantly reduced sequencing costs while markedly improving throughput and speed (Table 1). These advances have made large-scale genomic and metagenomic studies feasible on an unprecedented scale. Nowadays, both second- and third-generation sequencing technologies are widely used to study antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) and ARGs[17,31].

Table 1. Comparison of commonly used sequencing platforms

Sequencing Technology Platform Read length Bias PCR-free Real-time sequencing Base modification detection Accuracy Cost Second generation Illumina ~150 to 300 bp PCR-related bias No No No > 99.9% Low DNBSEQ ~150 to 300 bp PCR-related bias No No No > 99.9% Low Third generation PacBio SMRT Tens of kb Low bias due to single-molecule sequencing Yes No Yes > 99.9% High ONT Nanopore Tens of kb Signal fluctuations Yes Yes Yes > 99.75% High Second-generation sequencing technologies

-

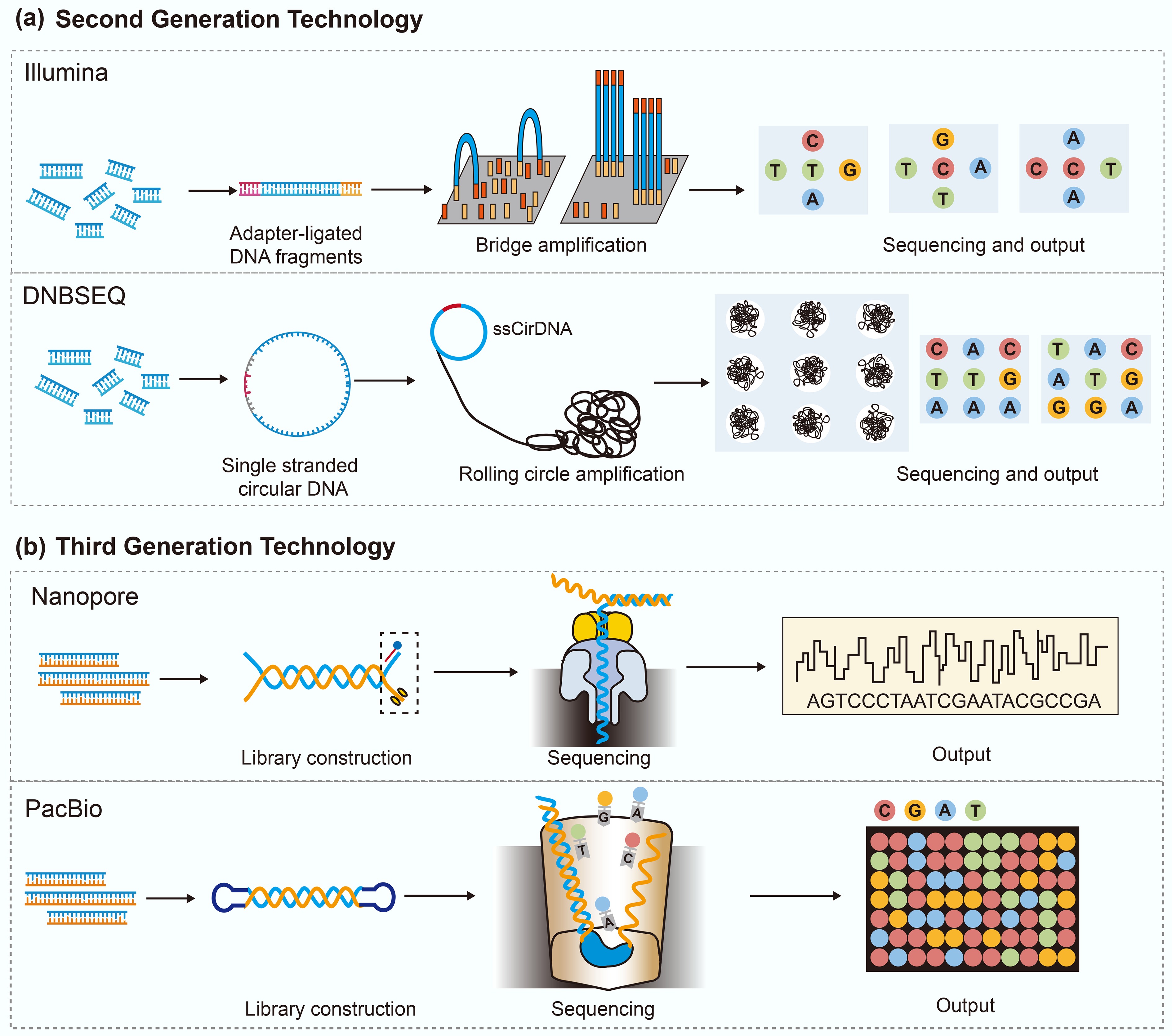

Second-generation sequencing technologies marked a critical paradigm shift from the linear, low-throughput nature of traditional methods to massively parallel high-throughput approaches[32]. Second-generation sequencing introduced massively parallel DNA sequencing, allowing millions of fragments to be read simultaneously and significantly increasing sequencing throughput[33]. In contrast to labor-intensive, time-consuming Sanger sequencing, second-generation sequencing technology can complete whole-genome sequencing within days or even hours. The workflow of second-generation sequencing usually involves several steps, including fragmentation, tagging, and amplification[34]. Specifically, the target DNA is first broken into short fragments. These fragments are then tagged with adapters, followed by bridge PCR or cluster amplification to create sequencing templates (Fig. 1a). The actual sequencing is performed using reversible terminators or other chemical methods to identify the bases.

Second-generation sequencing is currently the most widely used sequencing technology, sequencing platforms including 454 pyrosequencing (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), SOLiD sequencing (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), Illumina sequencing-by-synthesis (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), Ion Torrent semiconductor sequencing (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and DNA nanoball sequencing (DNBSEQ, Beijing Genomics Institute/MGI Tech Co., Shenzhen, China). Among these, Illumina's sequencing-by-synthesis and BGI's DNBSEQ platforms have become the dominant technologies owing to their high throughput, accuracy, and cost efficiency. Several distinct advantages support its widespread use[35]. First, it provides high sequencing throughput, capable of processing millions of DNA fragments in a single run, thereby enabling large sample batches to be sequenced within days or even hours. Second, the per-base cost of sequencing has been significantly reduced by continuous technological advancements and increasing commercial competition, making comprehensive sequencing accessible to a wide range of laboratories. Third, second-generation sequencers deliver high accuracy for short reads and can detect low-frequency variants with high accuracy and depth. Fourth, second-generation sequencing workflows are highly automated, with most steps performed on automated instruments or liquid-handling platforms. However, second-generation technologies also have notable limitations. A primary drawback of second-generation sequencing technology is its short read length (typically 150–300 base pairs), which makes it difficult to resolve complex genomic regions. In addition, PCR-based clonal amplification of DNA libraries can introduce biases and errors, with some fragments amplifying more efficiently than others, leading to uneven coverage. Lastly, second-generation sequencing results in massive datasets, posing substantial demands on data processing, storage, and interpretation[32,36,37].

Third-generation sequencing technologies

-

The application of third-generation sequencing has expanded, serving both as a supplement to and a replacement for second-generation methods[34]. At present, third-generation sequencing is dominated by two platforms, Single-Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing from Pacific Biosciences and nanopore sequencing from Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT)[38] (Fig. 1b). SMRT sequencing relies on the real-time observation of nucleotide incorporation by a DNA polymerase immobilized at the base of a zero-mode waveguide[39]. As deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs) are added to the growing DNA strand, their fluorescent labels emit base-specific signals that are detected with high temporal resolution. The identity of each incorporated nucleotide is inferred based on the distinct spectral and kinetic properties of these fluorescent emissions[40]. In contrast, nanopore sequencing detects DNA molecules as they pass through membrane-embedded nanopores under an electric field, allowing direct, real-time reading of nucleotide sequences. The passage of nucleotides through the nanopore produces characteristic fluctuations in the ionic current, which can be decoded to identify the DNA sequence[41]. These changes are sequence-dependent and are decoded in real time to reconstruct the underlying nucleotide sequence. Furthermore, several companies have developed platforms based on third-generation sequencing technologies, including Axbio Biotechnology, Qi-Tan Gene Sequencing Pioneer, Beijing Polyseq Biotech, and BGI.

Third-generation sequencing offers notable improvements over second-generation sequencing[42,43]. First, third-generation sequencing can produce long reads spanning several kilobases, significantly improving the resolution of complex genomic regions. Second, third-generation sequencing workflows are PCR-free, enabling the direct sequencing of native DNA molecules and thereby reducing amplification-associated biases and errors. Third, nanopore sequencing provides real-time access to sequencing information during the run, facilitating rapid turnaround, adaptive sampling, and time-sensitive decisions. Lastly, third-generation sequencing can detect base modifications, such as DNA methylation, allowing simultaneous capture of both genetic and epigenetic information from the same molecule. However, third-generation sequencing technologies are still limited by several technical and financial factors. First, the sequencing cost per base of third-generation sequencing remains higher than that of second-generation sequencing. Second, third-generation sequencing platforms generally exhibit higher raw error rates, thereby requiring consensus sequencing or hybrid correction strategies. Third, their data throughput per run is comparatively lower, which can be a constraint in applications requiring deep coverage, such as metagenomic profiling. Finally, long read data present unique analytical challenges, including error correction and structural variant detection, which require specialized bioinformatics tools and workflows.

-

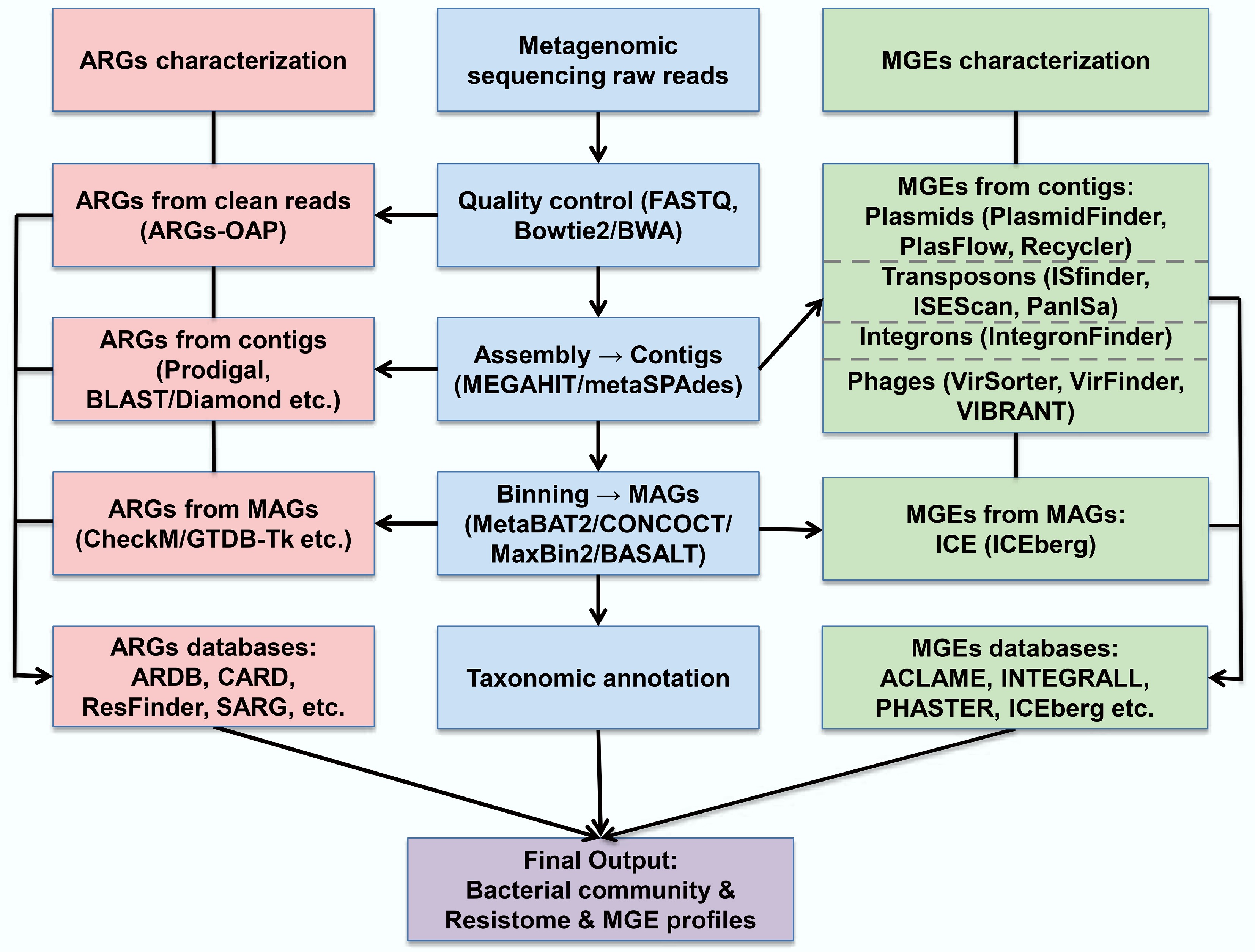

In recent years, metagenomics has dramatically improved the identification of ARGs and MGEs, providing crucial insights into the occurrence and dissemination of antibiotic resistance[44,45] (Fig. 2). The second-generation sequencing technology has become the mainstream platform for metagenomic research due to its high throughput, high accuracy, and relatively low cost[46]. Furthermore, third-generation sequencing technology, i.e., long-read sequencing, has significantly expanded the scope of metagenomic analysis[47,48].

Metagenomics data analysis workflow

-

In studies using the metagenomics method for the detection of ARGs and MGEs, bioinformatics is critical. The initial step involves quality control of raw sequencing reads, including the removal of low-quality reads, trimming of adapter sequences, and filtering for potential contaminants[49]. In bacterial metagenomic analysis, host-derived reads are also commonly removed by aligning them to a reference host genome using tools such as Bowtie2 or BWA[50,51]. Once quality control and host removal are completed, the clean reads are assembled de novo into contiguous sequences (contigs). Common assemblers used in metagenomic contexts include MEGAHIT and metaSPAdes, both of which are optimized for the complexity and uneven coverage of environmental microbial communities[24,52] (Fig. 3).

Assembly enables the reconstruction of longer genomic fragments, facilitating the detection of novel genes and gene clusters that are difficult to identify from unassembled short reads. This step significantly enhances the ability to characterize the diversity and genomic context of ARGs and MGEs in complex microbial environments. Subsequently, contigs can be grouped into metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) using binning algorithms such as BASALT, MetaBAT2, CONCOCT, or MaxBin2[23,53−55]. These MAGs provide draft-level genomes that support downstream functional annotation, taxonomic classification, and comparative genomic analyses, offering a more complete picture of the resistome and mobilome architecture.

Metagenomic characterization of ARGs and ARG abundance units

ARG profiling from metagenomic data

-

In metagenomic studies of microbial communities, detecting ARGs relies on sequence comparisons against curated reference databases. Depending on the research objectives, alignments can be performed using short reads, assembled contigs, or metagenome assembled genomes. For analysis based on contigs and MAGs, open reading frames (ORFs) are first predicted from assembled sequences, and candidate ARGs are identified using sequence similarity and alignment criteria. Matches that meet the required identity and coverage criteria are annotated as ARGs utilizing a variety of established databases and tools. These databases differ in gene coverage, update frequency, classification strategy, and underlying curation methods.

ResFinder is one of the earliest ARG databases, maintained by the Center for Genomic Epidemiology and focusing on acquired resistance genes in clinically relevant bacteria[56]. It employs BLAST for homology searches and performs well on assembled draft genomes from cultured isolates[57]. However, its gene coverage is relatively limited, which can be a drawback for complex or environmental samples. The Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) provides a more comprehensive, functionally annotated set of ARGs[58]. It includes annotations on resistance mechanisms, drug classes, and functional characteristics. When paired with the Resistance Gene Identifier (RGI) tool, CARD supports both homology-based and model-based detection, providing a reliable framework for studies of clinical and environmental resistomes[59]. Its frequent updates and structured ontology enhance its reliability for high-confidence identification. For studies focusing on environmental samples, the Structured Antibiotic Resistance Gene (SARG) database provides a valuable framework[60]. It incorporates entries from CARD and the Antibiotic Resistance Genes Database (ARDB) and reclassifies ARGs into a unified three-level hierarchy (type, subtype, and reference sequence), facilitating standardized comparative analyses across datasets. The accompanying ARGs-OAP pipeline integrates gene prediction, quality filtering, and abundance normalization, and is widely used for resistome profiling in environmental metagenomics. Later, the CARD database also incorporated ARDB content, expanding its coverage[61].

In addition to the databases described above, several other ARG databases and tools have been applied in various contexts, including ARDB, DeepARG, and AMRFinder[26,62,63]. While these databases are not discussed in detail here, they serve as valuable alternatives.

ARG abundance units in the metagenomic method

-

Metagenomic sequencing is widely used to quantify ARGs in samples from various environments, and ARG abundance has been reported in multiple units across studies. Parts per million (PPM), originally introduced by Yang et al., was among the earliest units used to quantify ARG abundance and represents the number of ARG-like sequences per one million metagenomic reads[64]. Although PPM offers a straightforward way to describe relative abundance, but it does not account for gene length. Therefore, some studies have employed normalized units such as Reads Per Kilobase per Million reads (RPKM), which adjust read counts based on both gene length and sequencing depth[65]. This method allows comparisons between ARGs of different sizes, offering a more refined representation of relative abundance. However, both PPM and RPKM remain relative measures and do not directly reflect the number of ARG copies per microorganism or per cell. Therefore, more biologically meaningful units have been proposed[66]. A commonly adopted approach is to express ARG abundance as the number of copies per 16S rRNA gene, providing an estimate of ARG prevalence per bacterium and allowing direct comparison with those obtained via qPCR in other studies[19]. A further refinement is to normalize ARG counts to the number of microbial cells, yielding a unit of copies per cell, which allows for more direct ecological and risk-related interpretations[60,66].

Absolute quantification of ARGs via the metagenomic method

-

As mentioned above, metagenomic sequencing provides relative abundance data for ARGs, rather than direct measurement of absolute abundance. While relative abundance is useful for within-sample comparisons, it is often unreliable for comparing across samples. Therefore, absolute quantification has become increasingly important for accurately assessing the burden and dynamics of ARGs across samples. To address this, additional experimental measurements are combined with metagenomics to quantify absolute abundance. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) is among the most commonly used techniques. It can estimate the total number of 16S rRNA gene copies per sample[67]. These values are then used to normalize the sequencing-based ARG counts, yielding estimates of gene copy numbers per unit volume. However, these indirect approaches rely on multiple experimental platforms and are susceptible to variability introduced by differences in amplification efficiency or sample processing protocols.

To overcome these limitations, the spike-in internal standard method has been developed for the direct quantification of ARGs[68−70]. This approach involves adding a known quantity of exogenous materials to each sample. There are two types of internal standard, namely synthetic DNA fragments and cellular internal standards (for example, Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria). DNA fragment standards are typically introduced after DNA extraction but before library preparation, to correct for variations in library construction and sequencing depth[69]. In contrast, cellular internal standards are added before DNA extraction, allowing correction for biases in cell lysis and DNA recovery efficiency[70]. The internal standard sequence must not be present in the original sample, as confirmed by PCR. After spiking, a defined number of internal standard copies are added, and the sample is processed and sequenced alongside the native microbial DNA. During downstream analysis, sequencing reads are mapped to both the internal standard reference and the ARG database. By comparing the read counts of the internal standard with its known input amount, a conversion factor can be calculated, allowing inference of the absolute copy number of ARGs in the sample. These methods improve quantification accuracy by controlling for variation in library construction and sequencing depth, and enables more reliable comparisons of ARG loads across different samples and studies.

Characterization of mobile genetic elements (MGEs)

-

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) is the primary pathway for ARG dissemination and is mediated by mobile genetic elements, including plasmids, transposons, phages, integrons, and ICEs. Identifying MGEs in metagenomic datasets is essential for elucidating the mechanisms underlying ARG dissemination. There are different strategies and tools for identifying various MGEs (Fig. 3).

Plasmids are extrachromosomal DNA molecules that often carry multiple resistance genes and can move between different bacterial species[71]. The identification of plasmids from metagenomic data relies on a combination of computational tools and curated databases. Alignment-based methods, such as PlasmidFinder, detect known plasmid replicon sequences through BLAST[72]. These methods offer high precision when matching known replicon types but are limited by database coverage and the fragmented nature of contigs in complex samples. In contrast, sequence composition-based approaches such as PlasFlow and cBar use machine learning models to classify DNA sequences as plasmid- or chromosome-derived[73,74]. Assembly-based methods like PlasmidSPAdes reconstruct putative plasmid sequences by identifying subgraphs with uneven coverage or circularity features, while Recycler specifically targets circular contigs indicative of closed plasmids[75,76].

Composite transposons, which often mediate the horizontal transfer of ARGs, are mobile genetic elements composed of one or more cargo genes flanked by insertion sequences, i.e., IS elements. Most detection approaches identify transposase genes and flanking repeats by either directly aligning sequences to databases such as ISfinder or by applying profile-based tools such as ISEScan, which employs HMMs built from curated IS protein families[77,78]. Alternatively, read-mapping tools like panISa look for signs of novel insertions by identifying split or anomalous read pairs[79]. However, the fragmented nature of short-read assemblies often prevents the reconstruction of large complete composite elements.

Integrons are genetic elements that are capable of capturing and expressing gene cassettes, often carrying ARGs. They are identified by the presence of the integrase gene (intI) and the associated recombination site (attC). A widely used tool for this purpose is IntegronFinder[80]. It combines HMM searches for integrase proteins with covariance models that detect attC structures, enabling the identification of full-length integrons and incomplete forms, such as integrase-only or cassette-only arrays. Its design allows the application to isolate both genomes and complex metagenomes.

Bacteriophages contribute to the spread of ARGs by mediating transduction. However, their identification in metagenomic datasets remains challenging due to the lack of conserved marker genes and high sequence variability. To overcome this, homology-based tools such as VirSorter and VirSorter2 have been developed to scan metagenomic contigs for known viral hallmark genes[81]. These tools are effective for identifying well-characterized viral sequences and generally yield high precision, though they may miss novel or highly divergent phages. In contrast, k-mer-based methods such as VirFinder, DeepVirFinder, and Seeker rely on oligonucleotide frequencies or on deep learning models trained on viral genomic signatures[82,83]. These methods tend to have higher sensitivity for novel phages, but are also more prone to false positives, especially when host-derived sequences share similar sequence features. More recently, geNomad has emerged as a widely used tool for viral identification. Built on a foundation model framework, geNomad integrates gene content information and deep neural network representations, using deep-learning-derived protein embeddings for sequence classification and HMM-based profile searches for functional gene annotation[84]. Furthermore, CheckV has become the standard tool for downstream quality and completeness assessment, ensuring reliable interpretation of viral genomes[85]. Hybrid tools like VIBRANT and viralVerify incorporate both gene content and structural genome features, such as coding density and genome length, to improve classification accuracy[86].

-

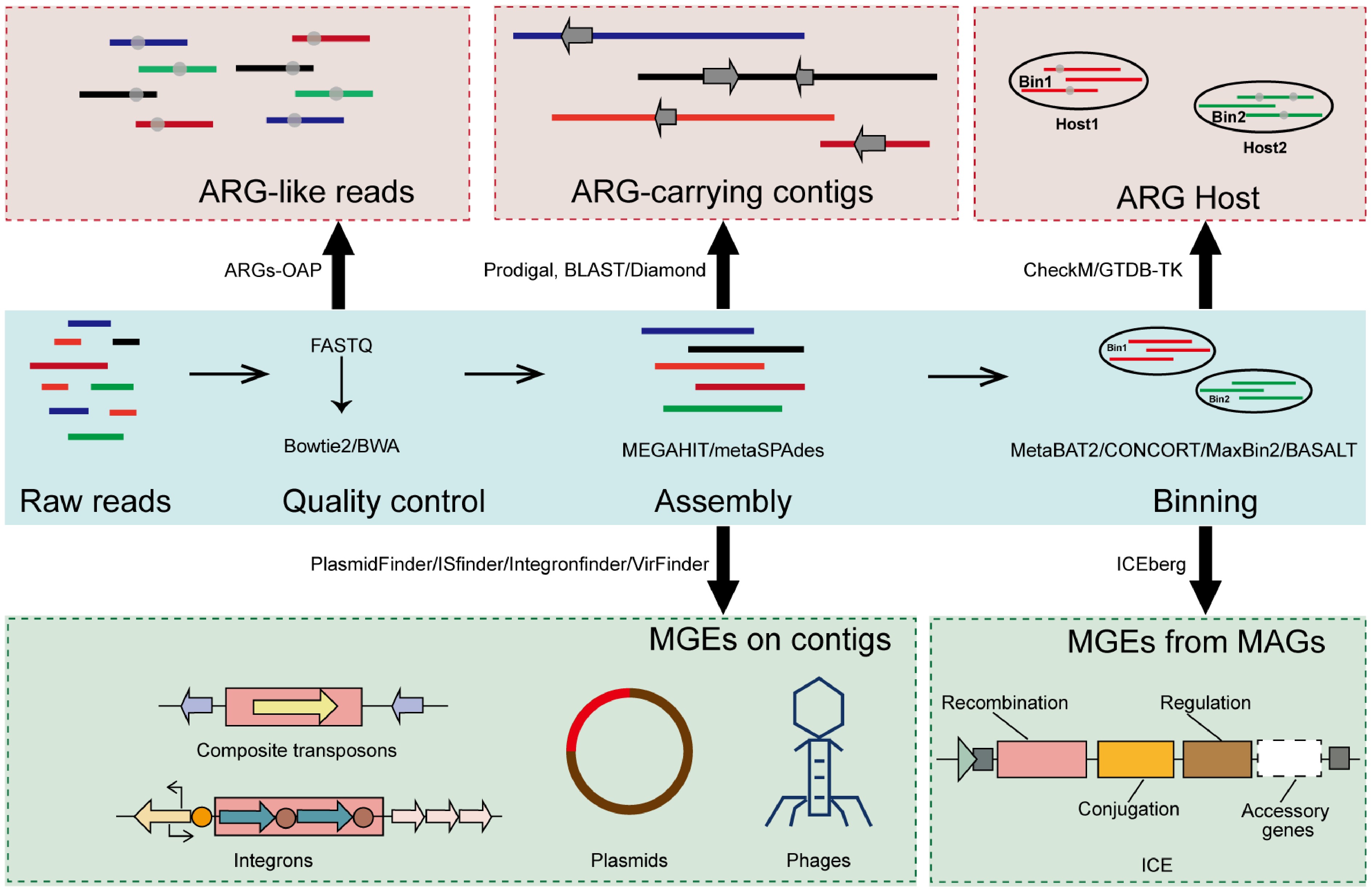

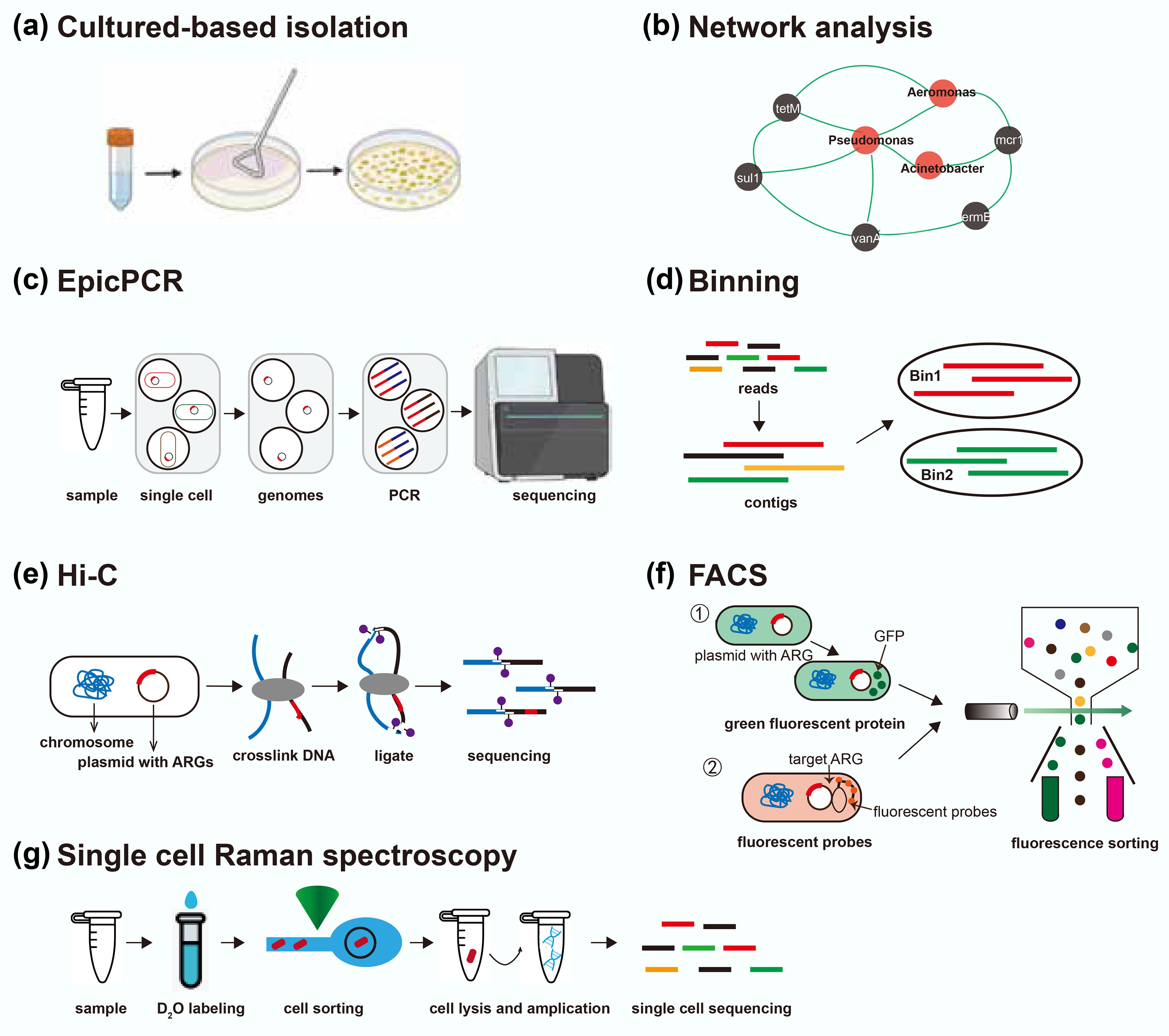

Metagenomic techniques have significantly expanded the understanding of ARGs and MGEs in both environmental and clinical settings. However, linking these elements to their microbial hosts remains a significant challenge. Determining the host microorganisms of ARGs and MGEs is essential for elucidating their ecological distribution, assessing their potential for HGT, and evaluating public health risks. To address this gap, a variety of complementary approaches have been developed (Table 2), ranging from traditional cultivation and genome binning to single-cell and proximity-ligation techniques (Fig. 4)[87].

Table 2. Comparison of primary methods for identifying the hosts of ARGs and MGEs

Method Principle Advantages Limitations Culture-based isolation Selective cultivation of resistant bacteria on antibiotic-containing media High specificity; linking genotype to phenotype; preservation of native genomic and mobile context Most bacteria unculturable; labor-intensive, and biased toward fast-growing strains Network analysis Statistical correlation of ARG abundance with microbial taxa abundance across samples Culture-independent; predicting large-scale candidate associations Indirect; spurious correlations;

low-abundance taxa introduce noise; no physical linkageEpicPCR Droplet encapsulation of single cells; fusion PCR linking the ARG fragment with the 16S rRNA gene Culture-independent; direct gene-host linkage PCR bias; primer limitations; multi-cell droplets cause false positives; Binning Short reads are first assembled into contigs, which are then clustered into MAGs Culture-independent; providing genomic context; linking ARGs to host genomes ARG regions fragmentation; assembly bias; mis-binning; inability to link plasmids to host genomes Hi-C Cross-linking DNA in cells; proximity ligation yields read pairs linking contigs from the same cell Culture-independent; physical linkage capture; linking ARG-carrying plasmid to host genomes; no prior targeting Complex pretreatment; specialized bioinformatics; variable cross-linking efficiency; high sequencing-depth requirements FACS Flow cytometric sorting of fluorescently labeled bacteria Culture-independent; isolation of target cells with high purity; support for conjugation studies Requires fluorescent labeling; low throughput Single cell Raman spectroscopy Isotopic probing (D2O) identifies metabolically active ARB via Raman spectral shifts Culture-independent; label-free operation; identify active ARB Low throughput; low accessibility of single-cell Raman platforms EpicPCR refers to emulsion paired isolation and concatenation PCR; Hi-C refers to high-throughput chromosome conformation capture; FACS refers to fluorescence-activated cell sorting.

Figure 4.

Overview of current approaches for identifying hosts of ARGs. EpicPCR refers to emulsion paired isolation and concatenation PCR; Hi-C refers to high-throughput chromosome conformation capture; FACS refers to fluorescence-activated cell sorting. This figure is modified from Rice et al.[87].

Cultured-based isolation method

-

The culture-based method is one of the earliest and most fundamental approaches for identifying antibiotic-resistant bacteria. This method recovers resistant bacteria by cultivating environmental and clinical samples on selective media containing specific antibiotics[88] (Fig. 4a). Isolates obtained through this process can subsequently be characterized using whole-genome sequencing or other molecular techniques to determine species identity as well as the presence of ARGs and MGEs[88]. The culture-based method could offer high resolution and specificity, with the added advantage of linking genotypic data to phenotypic resistance traits. Moreover, this allows for the direct association of ARGs with their native genomic and mobile contexts. However, most environmental bacteria remain unculturable under standard laboratory conditions. As a result, these methods often capture only a small and potentially biased subset of the resistome. Additionally, culturing is time-consuming and labor-intensive, and the selective conditions may favor the growth of strains that are not representative of the broader microbial community.

Network analysis for host-gene association inference

-

Network analysis infers potential ARG hosts by calculating statistical co-occurrence patterns across multiple samples[19,89] (Fig. 4b). In this approach, the relative abundances of ARGs and microbial taxa are quantified, and pairwise correlations are calculated to identify associations between them. A co-occurrence network is then constructed, with nodes representing ARGs or taxa and edges indicating statistically significant correlations, suggesting possible host-gene relationships. While this method can identify candidate associations at scale, it is inherently indirect and does not provide definitive evidence of physical linkage. Additionally, complex microbial communities and the presence of low-abundance taxa may introduce noise and spurious correlations, limiting the reliability of inferred associations. Therefore, network analysis is best used in combination with other methods that provide direct host-gene linkage.

Emulsion paired isolation and concatenation PCR (epicPCR)

-

EpicPCR is a culture-independent method for directly associating functional genes with phylogenetically marked genes from the same microbial cell[90]. In this approach, individual cells are encapsulated within polyacrylamide beads and lysed inside microdroplets. A subsequent fusion PCR step amplifies both a portion of the 16S rRNA gene and a target ARG, generating a chimeric amplicon that links the functional gene to the taxonomic identity of its host. Sequencing these chimeric products provides high-resolution host-ARG associations without the need for genome assembly (Fig. 4c). EpicPCR is a high-throughput method that can process millions of droplets in parallel[91]. However, as a PCR-based method, it is subject to limitations such as primer mismatch, nonspecific amplification, and amplification bias across taxa. Additionally, more than one cell may be encapsulated within a single droplet in some single-cell or droplet-based assays, which can lead to false positives. The method is semi-quantitative, as variations in cell lysis efficiency and PCR performance can affect the relative representation of different taxa. Moreover, the detection range is constrained by primer design, limiting the approach to predefined target genes. Despite these limitations, epicPCR offers a powerful tool for mapping gene–host relationships in complex microbial communities[91,92].

Genome binning approach

-

For the binning-based approach, short reads are first assembled into contigs, which are then clustered into MAGs using sequence composition and abundance profiles across multiple samples[45] (Fig. 4d). By assigning a taxonomy to each MAG, any ARG found on a MAG can be linked to that host[93]. This approach allows recovery of a near-complete genome, including both chromosomal and plasmid sequences, thus preserving the genomic context of ARGs. MAGs also provide high-resolution taxonomic assignments and can reveal the co-occurrence of multiple ARGs within the same genome, offering valuable insights into multidrug resistance and gene linkage[94]. However, the binning-based method is limited by its reliance on assembly, which typically utilizes only a fraction of the total sequencing reads. Conserved ARGs or repetitive elements often disrupt contig assembly, resulting in short or fragmented ARG-containing sequences that are difficult to bin accurately. Consequently, crucial contextual information may be lost, such as the taxonomic origin or mobility of a gene. Additionally, contigs can be misassigned to incorrect bins, producing chimeric MAGs, and mobile genetic elements such as plasmids may remain unbinned due to their distinct sequence characteristics[52].

High-throughput chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C)

-

Chromosome conformation capture (3C), and 3C-based methods, including Hi-C, were initially developed to study chromatin interactions in eukaryotic cells through proximity ligation. Hi-C begins with formaldehyde fixation of intact cells to cross-link DNA regions that are in close spatial proximity[95]. After DNA fragmentation and re-ligation, paired-end sequencing of the Hi-C library yields read pairs that link genomic regions originally co-localized within the same cell (Fig. 4e). In metagenomic applications, this linkage information can be combined with shotgun assembly to assign contigs, including plasmids or fragments containing ARGs, to specific microbial genomes[96]. Unlike traditional 3C approaches, which depend on predetermined primers to detect selected loci, Hi-C captures chromatin interactions without prior sequence targeting. However, the Hi-C technique requires complex sample preparation and specialized bioinformatics to interpret the interaction data, and cross-linking efficiency can vary, potentially biasing the detection of DNA proximities. Additionally, resolving the genomes of low-abundance microorganisms in highly diverse communities from metagenomic Hi-C data can be challenging.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)

-

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) is a technique that integrates flow cytometry with downstream molecular analysis, such as metagenomics, to sort and isolate target cells based on fluorescence. In this approach, the target ARGs or ARB must be fluorescently labeled to be detected and isolated[97] (Fig. 4f). One advantage of FACS is the ability to physically separate and collect fluorescently tagged cells with high purity, facilitating targeted study of their genomic or phenotypic properties. For example, FACS has been applied to study the conjugative transfer of ARGs in environmental samples by sorting donor cells carrying labeled ARGs and recipient cells that acquire them during horizontal gene transfer[97]. Despite these strengths, FACS is not well-suited for comprehensive profiling of ARG hosts in complex microbial communities, because only pre-selected or labeled targets can be detected. Combining FACS with techniques such as rolling-circle amplification FISH (RCA-FISH) or catalyzed reporter deposition FISH (CARD-FISH) may enable in situ detection of ARG hosts and broaden their use in environmental microbiology. However, these combined approaches are constrained by low throughput, the high cost of fluorescent probes, and the need for specialized instrumentation and expertise.

Single-cell Raman spectroscopy (SCRS)

-

Single-cell Raman spectroscopy is an emerging, culture-independent method for identifying ARB at single-cell resolution. Single-cell Raman spectroscopy is often combined with isotopic probing (e.g., D2O-labeled water) to distinguish metabolically active ARB cells from non-resistant or inhibited cells under antibiotic exposure[98] (Fig. 4g). Cells that grow and incorporate deuterium exhibit characteristic shifts in their Raman spectra (due to C-D bond formation), allowing resistant and metabolically active bacteria to be distinguished from susceptible or inactive cells under antibiotic exposure. SCRS combined with Raman-activated cell sorting (RACS) enables single-cell isolation based on Raman spectral profiles, enabling further analyses such as genome sequencing or ARG detection. A significant advantage of SCRS is that it does not require prior knowledge of specific resistance genes or the use of fluorescent labels, making it particularly valuable for detecting unknown or unculturable resistant taxa. However, the technique is limited by low throughput, complex instrumentation, and the inability to directly identify ARG sequences, necessitating its use in conjunction with complementary molecular methods for comprehensive characterization.

-

Metagenomic sequencing has significantly improved the ability to characterize ARGs profiles in diverse environments. However, not every resistance gene poses the same risk, and identifying which ARGs pose a threat to human health is not straightforward. Therefore, comprehensive risk assessment frameworks are needed to assess the threat posed by ARGs. In recent years, studies have reported ARG risk evaluation at two complementary levels: one focusing on the inherent risk of individual genes based on their genetic context, mobility, and host range; and the other assessing the overall resistome risk at the sample level by integrating abundance, potential for HGT, and pathogen association.

Gene-level risk evaluation of ARGs

-

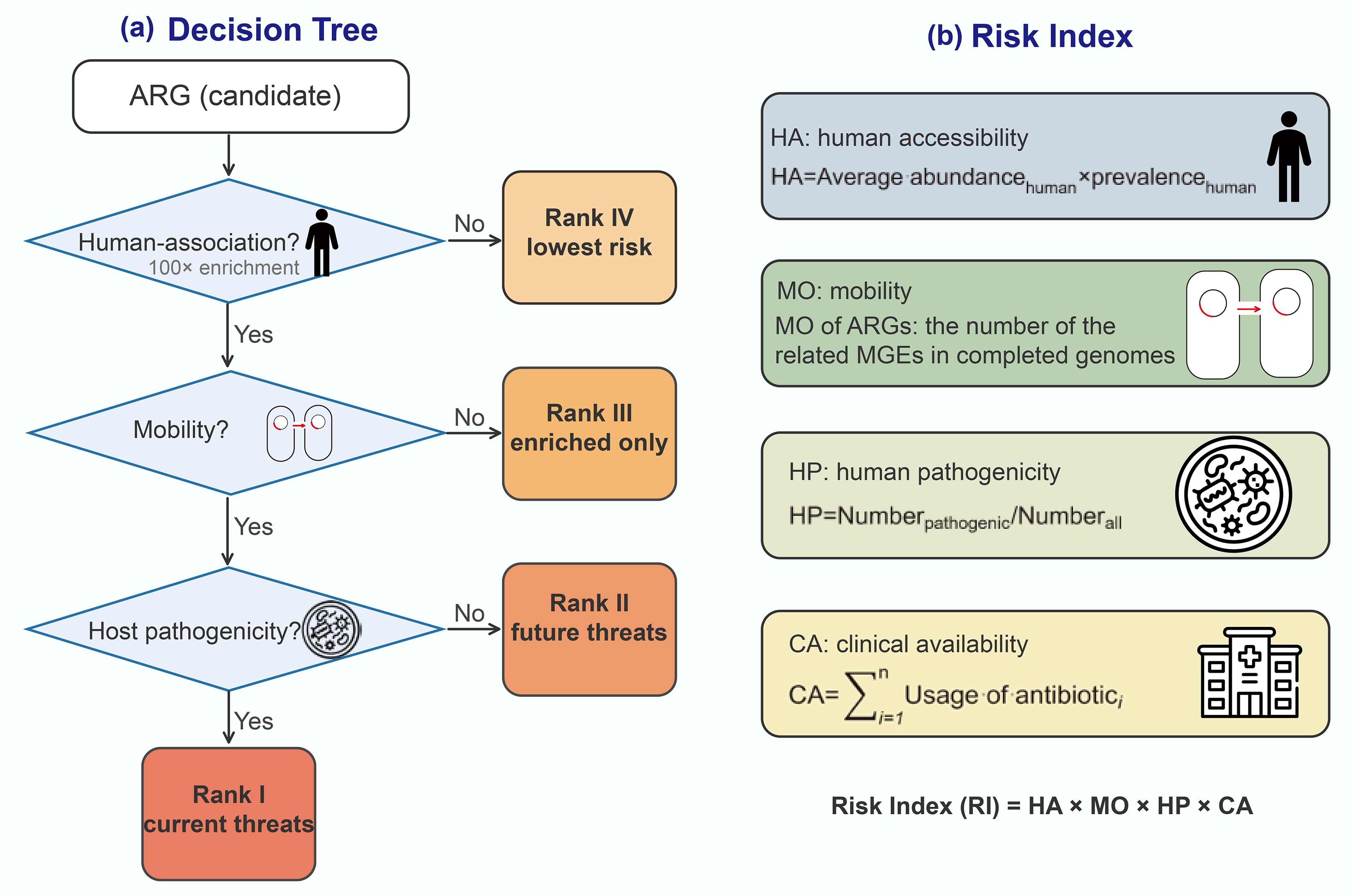

Recent methods score individual resistance genes using ecological and genomic criteria. Zhang et al. first reported a simple decision tree based on three key criteria: (1) human-association (enrichment in anthropogenic environments); (2) mobility (presence on mobile genetic elements); and (3) host pathogenicity (presence in known human pathogens)[99]. Using these criteria, ARGs are classified into four risk ranks[29] (Fig. 5a). ARGs that do not meet the first criterion are designated 'Rank IV' (lowest risk). Those meeting only enrichment are Rank III, those meeting enrichment and mobility (but not yet in pathogens) are Rank II ('future threats'), and those meeting all three are Rank I ('current threats'). This framework clearly differentiates high-risk ARGs (Rank I and II) from the lower-risk pool (Rank III and IV), and aligns well with expert assessments of clinical importance.

Other gene-centric approaches assign a continuous risk index rather than discrete ranks. For example, Zhang et al. define four quantitative indicators capturing different risk dimensions: human accessibility (HA), mobility (MO), human pathogenicity (HP), and clinical availability (CA)[99] (Fig. 5b). In this framework, HA is the average abundance multiplied by the prevalence of the ARG in human-associated samples; MO is the number of MGEs known to carry the ARG; HP is the fraction of ARG-hosting taxa that are human pathogens; and CA sums the clinical usage of antibiotics the ARG can resist. The gene-level risk index (RI) is then calculated as RI = HA × MO × HP × CA, so that high values indicate that an ARG is abundant in humans, widely mobile, present in pathogens, and confers resistance to heavily used drugs. These gene-level frameworks are directly interpretable: each ARG is classified or scored for risk and can be monitored or reported as a priority. They rely on metagenomic surveillance data and reference databases to determine human enrichment, mobility, and presence in pathogen genomes. However, a limitation is that these assessments are based on sequence homology and co-occurrence data rather than on direct experimental confirmation of resistance phenotypes.

Sample-level risk evaluation of ARGs

-

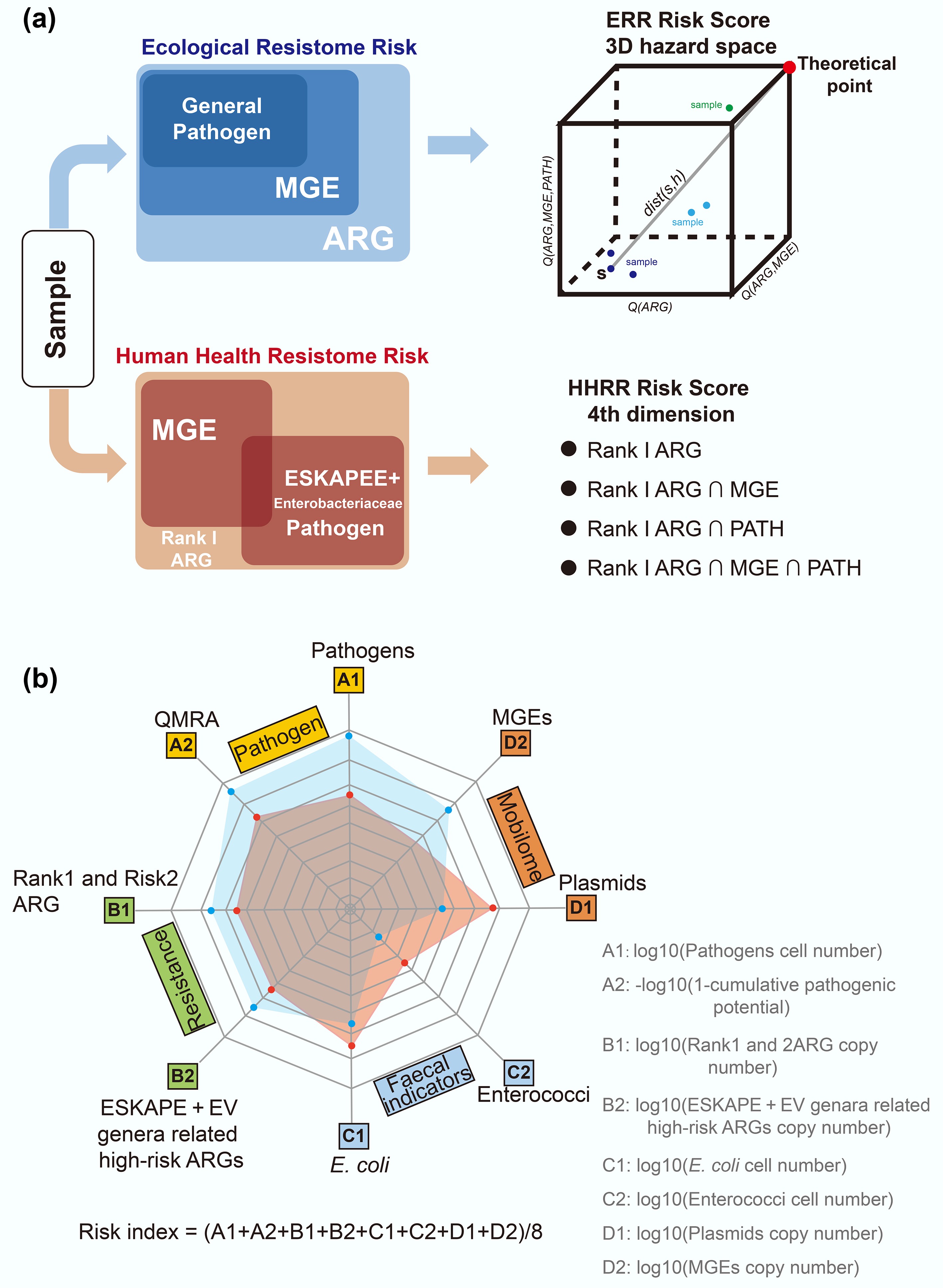

Rather than evaluating individual genes, sample-level approaches assign a risk score to an entire metagenomic sample or environment, based on its collective resistome. These methods integrate gene occurrences and their context to rank environments or hosts by overall ARG threat. A well-known pipeline is MetaCompare, which estimates resistome risk by analyzing assembled metagenomic contigs for ARG presence and co-occurrence with mobility and pathogen markers[100] (Fig. 6a). The MetaCompare pipeline first de novo assembles the metagenomic sequencing reads, then screens the assembled contigs for three categories of features: (1) contigs containing any ARG; (2) contigs containing an ARG co-located with an MGE; and (3) contigs containing an ARG co-located with both an MGE and a pathogen-associated sequence. The proportions of contigs in each category are normalized, and each sample is placed in a three-dimensional hazard space, with samples assigned a resistome risk score. In effect, samples with more ARGs co-localized with MGEs and pathogens rank as higher risk. The output is a single quantitative score for each sample, allowing comparison across environments or treatments.

Figure 6.

Sample risk assessment framework. (a) Risk score assessment workflow based on MetaCompare 2.0[101]. (b) The risk assessment framework integrates four key components, including absolute quantification[70]. ARG refers to antibiotic resistance gene; MGE refers to mobile genetic element, PATH refers to pathogen; ESKAPE refers to Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species; EV refers to Escherichia coli and Vibrio.

Furthermore, Zhang et al. extended their gene-level index into a sample-level metric[99]. In their framework, once each ARG is assigned a gene RI as described above, the risk index of a sample is calculated as the abundance-weighted sum of the RIs of all ARGs in that sample (Fig. 6b). That means a sample's risk reflects both how many high RI genes it carries and how abundant they are. In principle, this approach yields a continuous risk index for each metagenome, leveraging the same underlying data (ARG annotations, abundances, MGE/host associations) computed in the gene-level analysis, but aggregating them to the sample level. Other sample-level metrics have been proposed. For instance, the MetaCompare pipeline has been updated to version 2.0 to distinguish between human health-related resistome risk and broader ecological resistome risk for each sample[101]. In general, sample-level frameworks emphasize the mobility potential of ARGs, along with overall ARG load and the taxonomic composition of the community.

More recently, Shi et al. have developed a comprehensive framework for sample risk assessment that integrates four key components: pathogens (A), resistance (B), facial indicators (C), and the mobilome (D)[70]. This framework quantifies multiple risk dimensions, including pathogens abundance (A1) and cumulative likelihood of infection (A2); absolute abundance of high-risk ARG categories such as rank 1, 2 (B1) and ESKAPE (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species) + EV (Escherichia coli and Vibrio)-related genes (B2); abundance of faecal indicators E. coli (C1) and Enterococci (C2); and the prevalence of plasmids (D1) and other MGEs (D2). An overall environmental risk index is then derived as the arithmetic mean of these eight criteria, with higher values indicating greater sample-level environmental risk.

It should be noted that the data requirements and outputs differ between gene- and sample-metric approaches. Gene-level schemes require large reference databases of ARGs, MGEs, and pathogen genomes, as well as broad metagenomic surveys to determine where each ARG is enriched. While read-based methods are suitable for gene-level profiling, assembly-based strategies are often employed to recover genomic context and improve annotation. Building on these, sample-level pipelines typically involve de novo assembly and integration with curated databases, making them computationally intensive. The interpretability of the results also differs: gene-level scores directly label specific ARGs as high-risk (facilitating targeted monitoring), whereas sample risk scores provide a single index per environment that must be contextualized (e.g., comparing hospitals vs soils). Both levels of assessment are complementary, and together they contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of antibiotic resistance risks in different environments.

Quantification strategies and their implications for risk assessment

-

Several of the above-mentioned risk assessment frameworks rely on relative abundance derived from metagenomic sequencing. While relative metrics allow comparisons of ARGs within a sample, they have several limitations. First, changes in relative abundance may reflect shifts in other community members rather than an actual change in the absolute burden of resistance. Second, relative abundance values cannot be readily compared across studies or environments because microbial biomass and community composition vary among samples. As a result, risk scores derived solely from relative abundance may overestimate risks in low-biomass environments or underestimate risks in high-biomass settings where absolute ARG loads are high.

With the increasing application of absolute quantification approaches, some recent frameworks have begun to incorporate absolute ARG abundance into risk evaluation[70]. Accumulating evidence demonstrates that absolute quantification is essential for correcting compositional biases. Integrating absolute abundance into risk assessment captures not only the genetic attributes of ARGs but also their real-world concentrations, which more accurately reflect transmission potential and public health relevance. This distinction is critical because the ecological impact and public health risk posed by ARGs are ultimately determined by the absolute number of resistance genes, their hosts, and the biomass that carries them. For example, two samples may display similar relative ARG profiles yet differ by orders of magnitude in their total microbial biomass; only absolute measurements can reveal whether an environment harbors a negligible number of resistance determinants or discharges large quantities of high-risk ARGs into downstream ecosystems.

-

Metagenomic approaches have expanded the ability to detect, quantify, and characterize ARGs across diverse environments. They facilitate the identification of both known and emerging resistance genes, reveal their association with MGEs, and allow inferences about their microbial hosts. These insights are essential for understanding the mechanisms and pathways driving the dissemination of antibiotic resistance.

Looking ahead, several technological developments are likely to influence how ARGs are monitored and evaluated. Improvements in long-read and real-time sequencing are beginning to provide clearer resolution of plasmids, genomic islands, and other mobile elements that are often difficult to assemble from short reads. Advancements in host-linking technologies will allow more accurate assignment of ARGs to their native hosts. At the computational level, hybrid assembly pipelines, deep learning-based ARG prediction, and comprehensive risk modeling frameworks are expected to enhance the detection of novel resistance determinants and refine assessments of their mobility and pathogenicity. Additionally, progress in absolute quantification and standardized methodology will also help improve comparisons of ARGs across different studies and environments.

By integrating these technological advances with coordinated international monitoring and data sharing, future work can achieve more precise identification of high-risk ARGs, improve the design of targeted interventions, and ultimately support efforts to safeguard antibiotic effectiveness and public health.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Peiju Fang: writing−original draft, validation, writing−review and editing; Zehui Yu: writing−original draft, validation, writing−review and editing; Jin Huang: validation, writing−review and editing; Bing Li: conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision, validation, writing−review and editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

This study was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2022YFE0103200), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 22176107 and 22476108), Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Bureau (Grant Nos SGDX20230821091559021 and GJHZ20240218113559006).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Summarized metagenomic technologies and computational tools for ARGs and MGEs profiling.

Compared methodological advances in host identification and absolute quantification of ARGs.

Integrated resistome risk assessment framework at gene and sample levels.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Peiju Fang, Zehui Yu

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Fang P, Yu Z, Huang J, Li B. 2026. Profile surveillance and risk assessment of the environmental dimension of antibiotic resistance via the metagenomic approach. Biocontaminant 2: e002 doi: 10.48130/biocontam-0025-0027

Profile surveillance and risk assessment of the environmental dimension of antibiotic resistance via the metagenomic approach

- Received: 09 November 2025

- Revised: 08 December 2025

- Accepted: 10 December 2025

- Published online: 23 January 2026

Abstract: Antibiotic resistance has been recognized as a global environmental and public health challenge. Over the past decades, methods of studying antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) have rapidly evolved. This review summarizes progress in metagenomic approaches for profiling ARGs, mobile genetic elements (MGEs), and their microbial hosts. The transition from second-generation to third-generation sequencing technologies, developments in ARG detection pipelines, and emerging strategies for absolute quantification are highlighted. In addition, novel approaches for linking ARGs to their hosts and assessing resistome risks at both gene and sample levels are discussed. Continuous improvements in methodologies are deepening the understanding of resistance dissemination, and providing a foundation for environmental surveillance and risk control.