-

In the natural environment, plants engage in continuous interactions with a wide variety of microorganisms, including protists, fungi, bacteria, viruses, and nematodes[1]. These microorganisms inhabit various plant structures or tissues, such as the rhizosphere (soil‒root interface), phyllosphere (air‒plant interface), and endophytes (plant tissue interior)[2]. Numerous lines of evidence have consistently indicated that fungi and bacteria are dominant within the microbial community and significantly influence the overall performance and survival of plants. The crucial role of microbial interactions in the rhizosphere is to increase plant health and productivity by facilitating plant nutrient absorption, promoting nitrogen fixation, and stimulating hormone production[3]. Some microorganisms can release bioactive substances or change the balance of nutrients, thus improving the ability of plants to withstand abiotic and biotic stresses[4]. However, microbial competition for resources and space with plants, as well as the potential induction of disease, can have detrimental effects on plant yield and quality[5]. Therefore, elucidating the variety and organization of microorganisms to achieve superior and abundant agricultural output is crucial.

Initial investigations have focused primarily on examining the structural and functional attributes of rhizosphere microorganisms, which can promote plant growth[6]. Notably, the parts of plants that are visible above the ground, especially the leaves, serve as extremely plentiful environments for microorganisms on a global scale. Bacteria dominate the phyllosphere, with cell densities ranging from 106 to 107 cells per square centimetre of leaf area[7]. Filamentous fungi, yeast strains, protists, and bacteriophages also colonize this environment[7]. Phyllosphere microbiomes play a critical role in leaf surface environments and can influence plant fitness in natural communities as well as agricultural quality and productivity. Several studies have demonstrated that epiphytic bacteria can produce biosurfactants, which facilitate the movement of nutrients through a hydrophobic cuticle and into favourable growth conditions[8,9]. Certain species of Methylobacterium have been found to utilize methanol as their primary carbon source during the colonization of various plant species, with some of these strains exhibiting the ability to increase plant fitness and improve survival prospects[10]. Some specific ecological groups of fungi have demonstrated the capacity to generate a wide variety of unique bioactive compounds that efficiently alleviate environmental pressures such as ultraviolet rays, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and drought[11]. Certain species within the Pseudomonas, Bacillus, and Trichoderma genera have been extracted from the abundant leaf microbiota and effectively employed as biological control agents for safeguarding plants[12,13]. However, investigations of phyllosphere microbial structure and function are relatively limited.

While microorganisms affect plants, these plants in turn influence the microbial community composition and quantity in their leaves, resulting in an adaptive coevolutionary relationship between phyllosphere microbes and plants[14]. Phytochemicals, secondary metabolites synthesized by plants, are recognized as significant regulators of microbial activity[15]. Microorganisms rely primarily on plant metabolites as their main sources of carbon and nitrogen[16]. The beneficial role of flavonoids in facilitating the establishment of endosymbiotic relationships between legume roots and nitrogen-fixing bacteria has been firmly established[17]. Citric and fumaric acids can be released by tomato roots and are reportedly used to attract plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria[18]. The microbial community in soils and cucumber growth have been shown to be influenced by p-coumaric acid[19]. Moreover, some plants, such as camomile, thyme, and eucalyptus plants, can even exude unique antimicrobial metabolites to resist pathogen infections[20].

Tea, derived from the young foliage of the tea plant (Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze), has become widely popular worldwide as a drink because of its wide range of beneficial compounds, such as flavonoids, alkaloids, and theanine[21]. Given their preference for warm and humid climates, tea plants are vulnerable to various fungal pathogens[22]. Tea blister blight, caused by Exobasidium vexans, poses a significant threat to tea production. This disease primarily affects young tea leaves, leading to yield losses of up to 25%–30%, particularly in susceptible cultivars[23]. Spraying fungicides is still the primary method of controlling this disease in tea fields and might involve significant costs and fungicide residue problems[23]. Investigating the response of the phyllosphere microbiome at the community level following pathogen invasion could increase the understanding of the interactions between microbes and plants, as well as the relationships between pathogens and other microbes, and could provide guidance for developing and applying biocontrol microorganisms for tea plants.

The present study examined the temporal variations in phyllosphere bacterial and fungal communities during the progression of tea blister blight. A comparative analysis was conducted to assess microbial diversity, community composition, and intramicrobial interactions between healthy and infected leaves. Furthermore, we examined the effects of tea blister blight on the biochemical compounds found in tea leaves. These investigations enhance the overall understanding of the relationships among microbes, hosts, and pathogens, providing valuable insights for the development and application of biological control microorganisms in tea cultivation.

-

Tea plant (C. sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze 'Fuding Dabaicha') was grown in gardens at the Northwest A&F University Tea Experimental Station (located in Xixiang, Shaanxi, China, at coordinates 32°57'43'' N, 107°40'12'' E). In September 2022, fresh third leaves with only one typical tea blister-blight symptom were collected and classified into the following three groups on the basis of established criteria: yellow, transparent patches that formed in the early stage (S1); circular blisters that appeared and were coated by white powdery basidiospores in the middle stage (S2); and necrotic spots that formed in the late stage (S3)[24]. Healthy leaves in the same position were used as control samples. For further analysis, the samples were kept at −80 °C.

Determination of biochemical compounds

-

To determine the overall polyphenol content (TP), the Folin–Ciocalteu technique was used[25]. In accordance with the China National Standard (GB/T 8314-2013), the ninhydrin reaction at 570 nm was used to determine the amino acid concentration. The soluble protein concentration was assessed via the Coomassie brilliant blue G250 method. The amount of water-soluble carbohydrates was determined as described by Morris[26]. High-performance liquid chromatography with UV detection (HPLC-UV, Agilent 1100VL, Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used to identify and measure caffeine, gallic acid, and catechins. The SPME-GC-MS technique was utilized to analyse the volatile compounds by employing a solid-phase microextraction device coupled with gas chromatography (Agilent 7697A)/mass spectrometry (Agilent 7890A). Our previous work provided a description of the parameters and conditions employed in the HPLC-UV and SPME-GC-MS analyses[27,28].

Genomic DNA extraction and sequencing

-

Following thawing at a temperature of 25 °C, 10 g of tea leaves were transferred to polypropylene test tubes containing 40 mL of sterile water and shaken at 150 rpm for 1 h at room temperature. The suspensions were separated using 0.22 μm vacuum filtration units (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), and the filtered sediment was used as a sample for the extraction of microbial DNA via HiPure Soil DNA Kits (Magen, Guangzhou, China). The V5−V7 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene and the internal transcribed spacer (ITS2) region of the fungus were amplified via PCR using the primers listed in Supplementary Table S1. Amplification reactions were performed according to the 50 μL system described in Supplementary Table S2. The amplification procedure is shown in Supplementary Table S3. The genes were purified using an AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit from Axygen Biosciences, Union City, USA, and quantified using an ABI StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies). The sequence libraries were pooled into equimolar quantities and paired-end sequenced (PE250) on the Illumina platform (San Diego, USA).

Bioinformatics analyses

-

The study involved filtering the raw data via FASTP v0.18.0[29] and then merging it with FLASH[30]. Using the UPARSE v9.2.64 pipeline[31], the filtered tags were grouped into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) with a similarity of ≥ 97%. Chimeric sequences were eliminated via the UCHIME algorithm v4.1[32]. Classification of the representative sequences was performed via the RDP classifier v2.2[33] on the basis of the SILVA database v132[34] and UNITE database v8.0[35] with the aid of a Bayesian naive model. The sequence data were stored in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under accession number PRJNA1050022.

Statistical analyses

-

Rarefaction curves were drawn to assess the sequencing depth. QIIME v1.9.1 was used to compute the α-diversity indices. A principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) plot was generated using the R 'vegan' package v2.5.3 on the basis of the weighted UniFrac distance. The sequence data for bacteria and fungi were normalized using the centred log-ratio transformation method[36]. The UpSet plot was visualized graphically with the R 'UpsetR' package v1.3.3. Visualization of the abundance statistics for each taxon was conducted using the R 'circlize' package v0.4.7. Heatmap visualizations were performed using TBtools software v2.136[37]. A co-occurrence network was constructed using the R 'igraph' package v1.1.2 on the basis of the Spearman correlation coefficient. Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 26.0). Descriptive statistical, analysis of variance (ANOVA), and Tukey's post hoc test were conducted to evaluate the relationships between different variables. The significance level for all the statistical tests was set at p < 0.05.

-

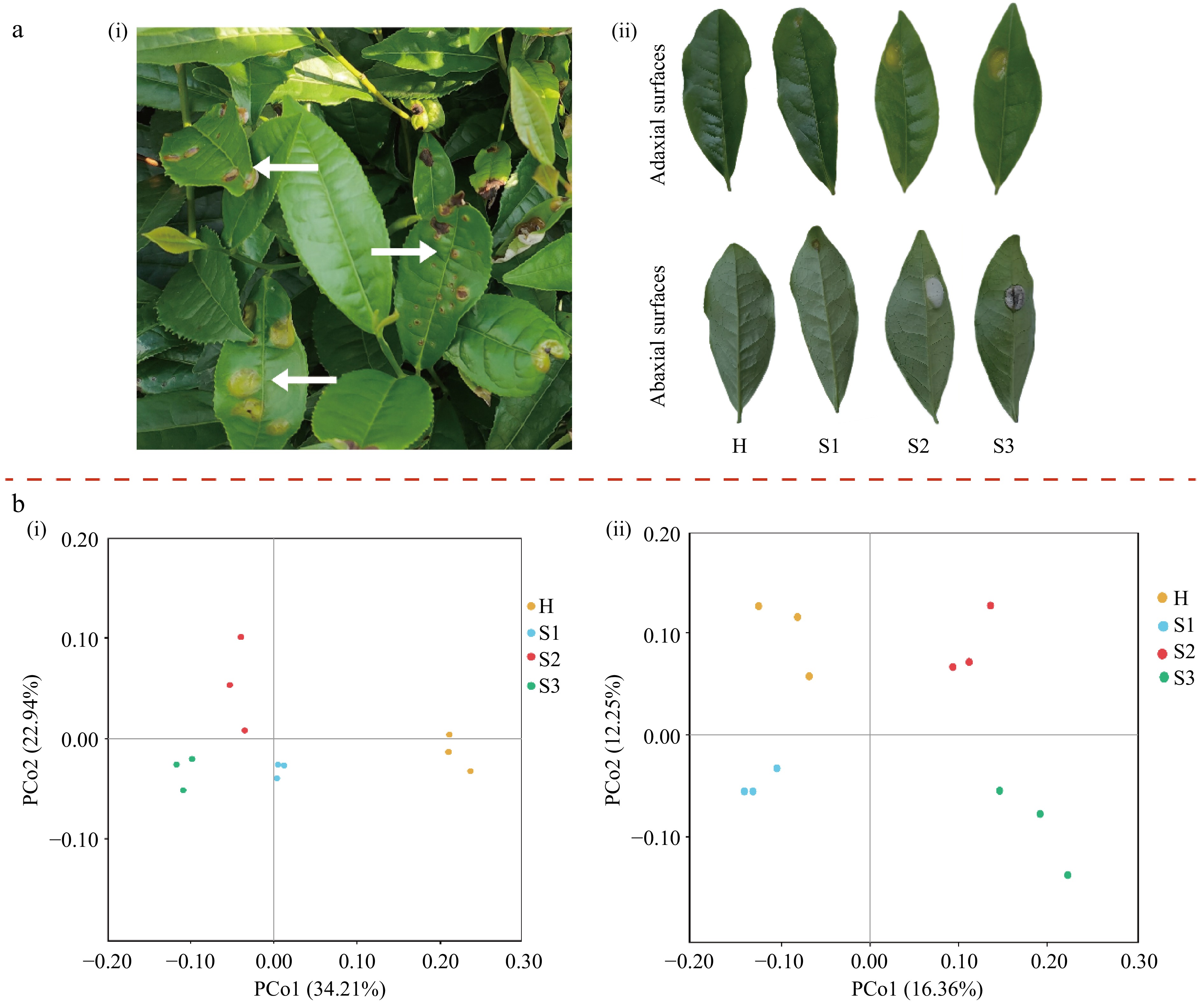

Tea blister blight is a severe disease that affects tea plantations (Fig. 1a). After infection by E. vexans, a pale yellow translucent spot appeared on the leaf (Fig. 1a, S1 stage), which subsequently leads to the formation of circular blisters caused by the indentation and protrusion of both the upper and lower leaf surfaces. As spores were produced, the convex surface on the underside of the leaf assumed a white and velvet-like appearance (Fig. 1a, S2 stage). Following sporulation, the blisters turned brown, and necrotic spots appeared (Fig. 1a, S3 stage). To assess alterations in the microbial community within tea leaves affected by blister blight, high-throughput sequencing was performed. After removing the low-quality reads from 12 samples, a total of 1,550,953 reads from the 16S region and 1,566,187 reads from the ITS region were obtained. From these reads, 14,190 operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were generated, including 3,792 bacterial OTUs and 10,398 fungal OTUs (Supplementary Table S4). All samples displayed a plateau-like pattern in the rarefaction curves (Supplementary Fig. S1), indicating that the sequencing depth was sufficient for further analysis.

Figure 1.

(a) Phenotypes and disease symptoms of leaves infested with tea blister blight. (b) PCoA plots of the microbial community based on unweighted UniFrac distances. (ai) Appearance of tea blister blight disease in tea plantations; (aii) disease phenotypes of tea leaves at different tea blister blight disease stages. (bi) Bacterial community; (bii) fungal community. H, healthy leaves; S1, tea leaves in the early disease stage; S2, tea leaves in the middle disease stage; S3, tea leaves in the late disease stage.

The diversity and microbial community composition of tea leaves were determined during blister blight. In our study, the α-diversity of the fungal communities showed a tendency to decrease in response to disease stress. In the fungal Sobs, Chao1 estimators, and Shannon index, significant differences were observed between healthy (H stage) and blister blight-infected tea leaves at the mid-stage (S2 stage) (Table 1). These findings indicated that the richness and diversity of the fungal community are correlated with the stage of blister blight, with significant differences becoming apparent from the middle stage of leaf disease (S2 stage) compared to healthy leaves (H stage). Tea leaves in the late stage (S3) of blister blight presented the lowest fungal Sobs, Chao1, and Shannon indices, and these values were significantly lower than those in healthy leaves, as shown in Table 1. However, no significant differences were observed in the bacterial Sobs, Chao1 estimator, or Shannon indices between healthy and blister blight-infected tea leaves (Table 1). PCoA analysis revealed that the different tea samples clustered together based on their microbial composition (Fig. 1b). Furthermore, the diversity and composition of microorganisms on the epidermis of tea leaves were significantly influenced by the development of blister blight, as indicated by the β-diversity of bacteria and fungi.

Table 1. Alpha diversity of bacterial and fungal communities on the surface of tea leaves at different blister blight disease stages.

Treatment Bacteria Fungi Sobs Chao1 Shannon Sobs Chao1 Shannon H 269.00 ± 11.36a 296.34 ± 11.97a 4.57 ± 0.46a 756.00 ± 29.60a 829.84 ± 36.32a 4.85 ± 0.31a S1 243.00 ± 38.69a 293.12 ± 28.85a 4.51 ± 0.48a 712.33 ± 13.58ab 812.52 ± 24.39ab 4.25 ± 0.49ab S2 268.67 ± 11.59a 307.35 ± 15.27a 4.79 ± 0.03a 684.67 ± 13.05bc 761.59 ± 6.78bc 3.58 ± 0.14bc S3 282.00 ± 60.23a 308.86 ± 57.81a 4.54 ± 0.42a 642.00 ± 51.18c 721.74 ± 33.74c 3.25 ± 0.38c H, healthy leaves; S1, tea leaves in the early disease stage; S2, tea leaves in the middle disease stage; S3, tea leaves in the late disease stage. The values are expressed as the means ± standard errors. Lowercase letters in the same column indicate significant differences at p < 0.05. Dynamics of the microbial community throughout the development of blister blight disease on tea leaves

-

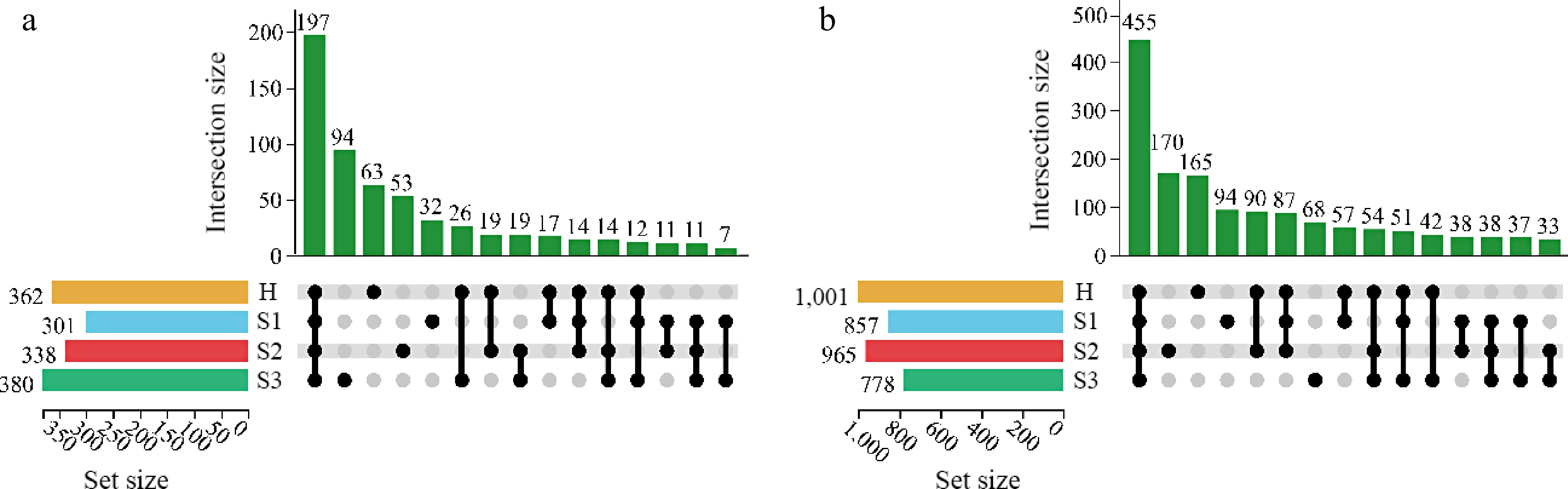

An UpSet plot was created to visualize unique OTUs across different developmental stages of blister blight (Fig. 2). Among the 589 distinct OTUs, 197 (33.62%) were found in all samples, indicating relatively low bacterial diversity across the blister blight stages. Specifically, 63 OTUs were unique to the H stage, while 32, 53, and 94 OTUs were unique to S1, S2, and S3, respectively. For fungal sequences, 455 OTUs (30.76% of the total OTUs) were shared among all samples. Additionally, 165, 94, 170, and 68 OTUs were uniquely presented at the H, S1, S2, and S3 stages, respectively.

Figure 2.

UpSet plot of OTUs of the microbial community at different disease development stages. (a) Bacterial community; (b) fungal community; H, healthy leaves; S1, tea leaves in the early disease stage; S2, tea leaves in the middle disease stage; S3, tea leaves in the late disease stage; Dark circles indicate samples containing accessions, while connecting bars indicate multiple overlapping samples.

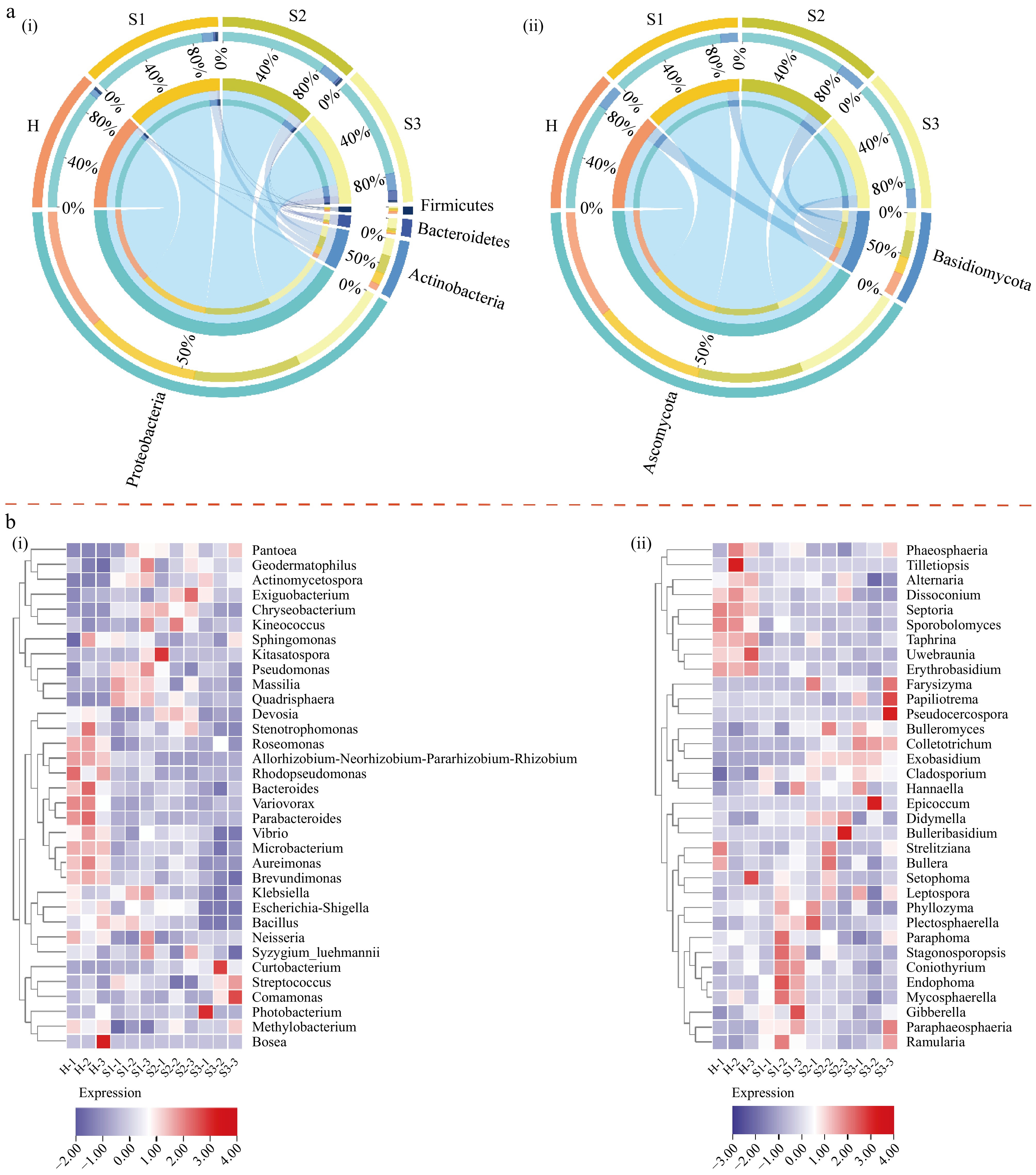

Fungal and bacterial community succession during the onset of tea blister blight was further investigated (Fig. 3a; Supplementary Table S5). The predominant bacterial phylum in the tea leaf samples was Proteobacteria. Its abundance in the H period reached 93.62% and decreased as the disease progressed. In contrast, the abundance of Actinobacteria, the second most prevalent phylum, increased from 4.43% to 13.26% during blister blight development (Fig. 3a). The abundance of Bacteroidetes was also affected by the disease, with values of 0.37%, 1.72%, 1.94%, and 7.73% at the H, S1, S2, and S3 stages, respectively (Fig. 3a). In addition, the fungal community was predominantly composed of Ascomycota and Basidiomycota, accounting for 79.31%−86.23% and 12.84%−20.23% of the total fungi detected, respectively (Fig. 3a).

Figure 3.

(a) Differences in the microbial community at different disease development stages at the phylum level. (b) Heatmap of the 35 most abundant genera in the bacterial and fungal communities at different disease development stages. (ai) Bacterial community; (aii) fungal community; (bi) bacterial community; (bii) fungal community. H, healthy leaves; S1, tea leaves in the early disease stage; S2, tea leaves in the middle disease stage; S3, tea leaves in the late disease stage. The samples are clustered according to the similarities among their constituents and arranged in a horizontal order. Red represents the more abundant genera in the corresponding group, while blue represents the less abundant genera.

A heatmap was created for an in-depth analysis using the 35 genera with the greatest abundance. Figure 3b shows a substantial difference between the H stage and S1−S3 stages, indicating a significant shift in the composition of bacteria and fungi between the infected and uninfected tea samples. In the diseased tea samples, the abundances of bacteria such as Aureimonas, Bacteroides, Microbacterium, Roseomonas, Variovorax, Brevundimonas, Parabacteroides, Rhodopseudomonas, Allorhizobium-Neorhizobium-Pararhizobium-Rhizobium, Sphingomonas, Escherichia-Shigella, Bacillus, Stenotrophomonas, and Vibrio decreased, whereas the abundances of Actinomycetospora, Geodermatophilus, Exiguobacterium, Chryseobacterium, Kineococcus, Kitasatospora, Pseudomonas, Massilia, Quadrisphaera, Curtobacterium, Streptococcus, Comamonas, and Pantoea increased (Fig. 3b). Among the fungi, the abundances of Erythrobasidium, Septoria, Sporobolomyces, Phaeosphaeria, Alternaria, Dissoconium, Uwebraunia, and Taphrina were significantly lower in the diseased tea samples compared to the healthy leaves. Conversely, the abundances of Cladosporium, Colletotrichum, Exobasidium, Didymella, Bulleromyces, Hannaella, Plectosphaerella, Paraphaeosphaeria, Ramularia, Pseudocercospora, Leptospora, and Gibberella were higher in the diseased samples (Fig. 3b).

Analysis of the co-occurrence network among microbial communities

-

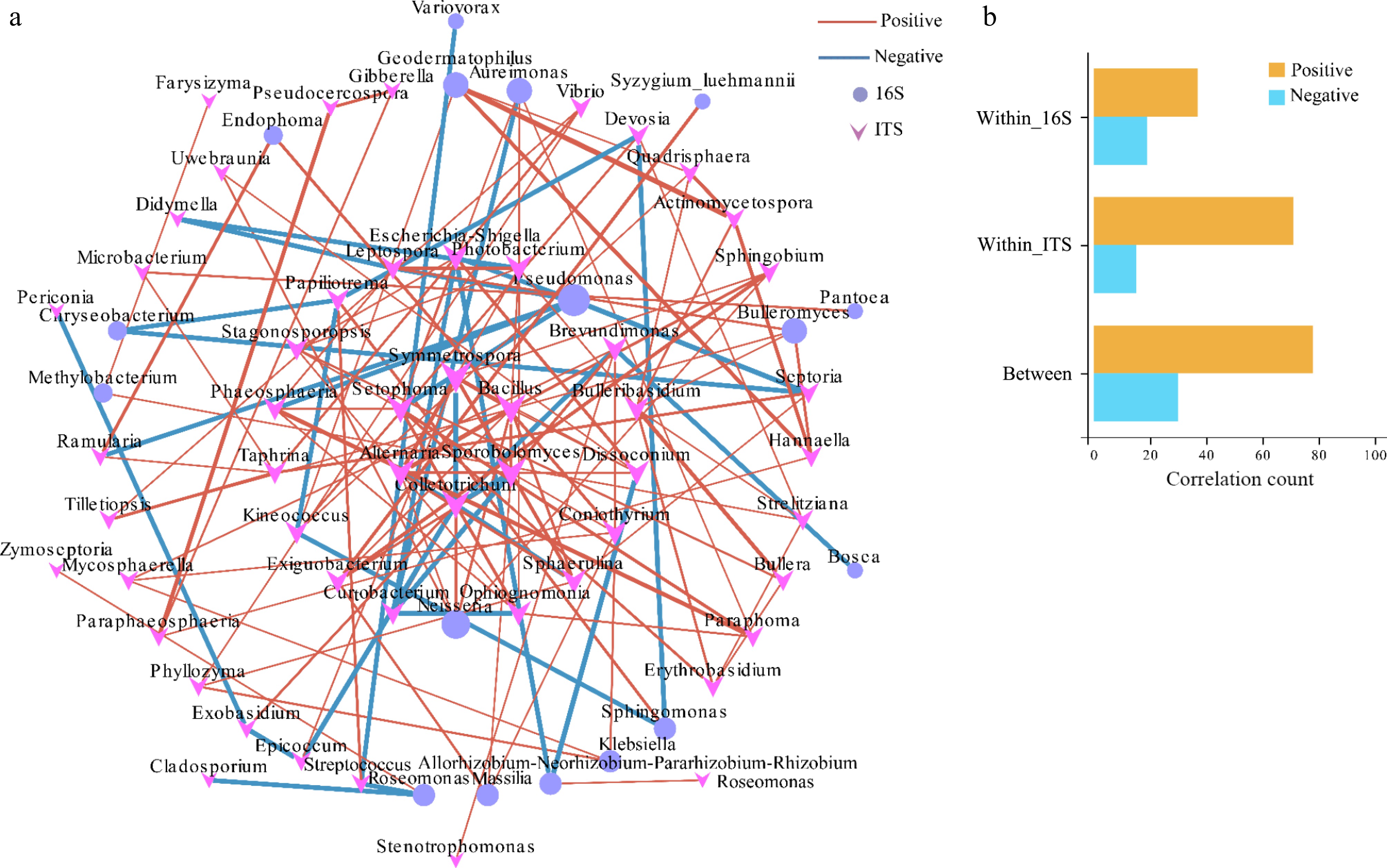

To investigate the connections between microorganisms, a co-occurrence network was constructed using Spearman correlation analysis (with correlation > 0.65 for positive correlations and < −0.65 for negative correlations, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05). The resulting network contained 73 nodes and 137 edges (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table S6). Node size was proportional to the importance of the genus within the microbial community. In addition, the network connectivity analysis revealed that bacterial genera such as Aureionas, Bulleromyces, Geodermatophilus, Pseudomonas, and Neisseria were among the hubs. For fungi, the genera Alternaria, Bulleribasidium, Colletotrichum, Coniothyrium, Sporobolomyces, Sphaerulina, Setophoma, Symmetrospora, and Ophiognomonia served as the main connecting nodes. Analysis of the microbial communities showed both positive and negative correlations. Visualization of the network revealed that a majority of the edges were positively correlated (105 edges) and that a smaller number of edges were negatively correlated (32) (Fig. 4a). Positive correlations were most commonly observed within fungi (43 edges) or between fungi and bacteria (44 edges), whereas negative correlations primarily occurred between fungi and bacteria (15 edges) (Fig. 4b). Bulleribasidium was positively correlated with Bulleromyces, Strelitziana, Quadrisphaera, Actinomycetospora, Erythrobasidium, and Bullera. Alternaria was positively correlated with Photobacterium, Neisseria, Dissoconium, Sporobolomyces, Sphaerulina, and Symmetrospora. In contrast, Alternaria was negatively correlated with Colletotrichum, and Spaerullina was negatively correlated with Septoria, Setophoma, Phaeosphaeria, Leptospora, and Ramularia.

Figure 4.

Co-occurrence network and correlation analysis among the bacterial and fungal communities. (a) Co-occurrence network. (b) Correlation analysis; all correlated OTUs were visualized in a network, where OTUs were set as nodes and the correlations were set as edges. OTUs that were identified as indicator OTUs in an indicator analysis and that also appeared in the co-occurrence were shown as larger nodes.

Response of the main chemical constituents of tea leaves to tea blister blight

-

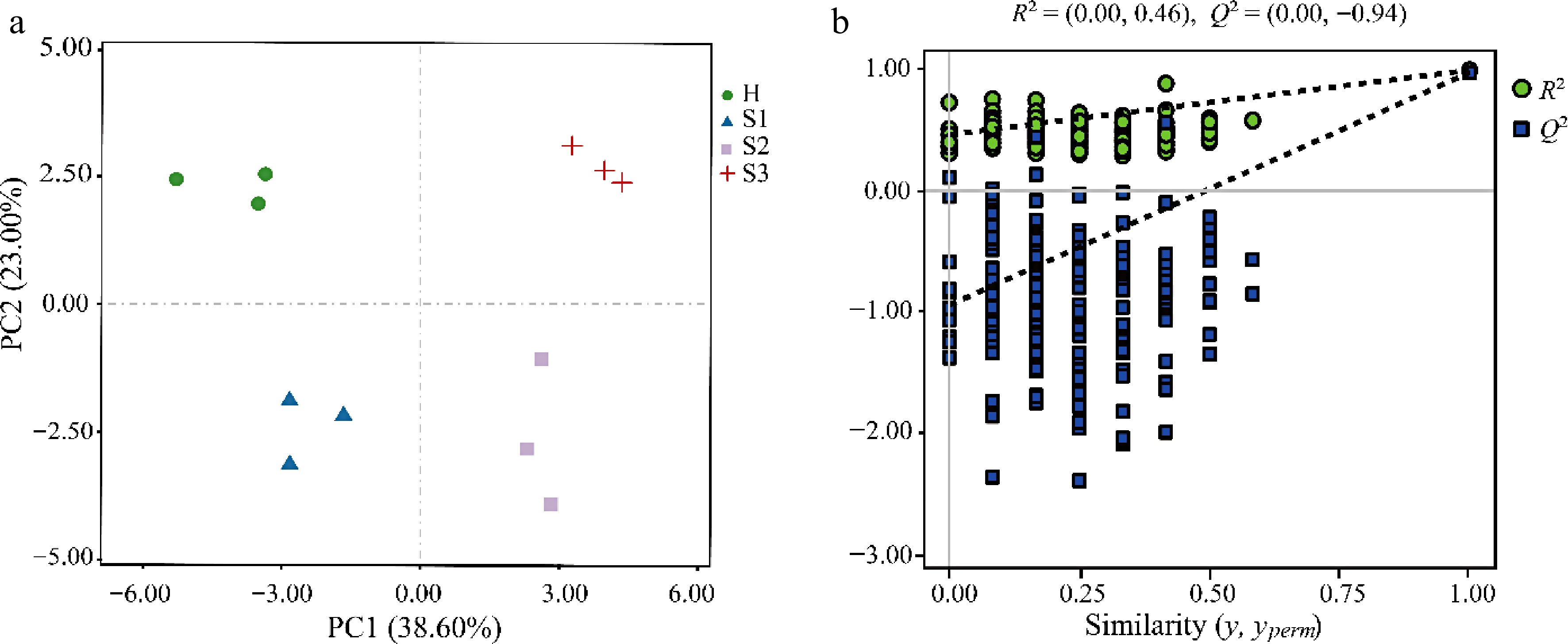

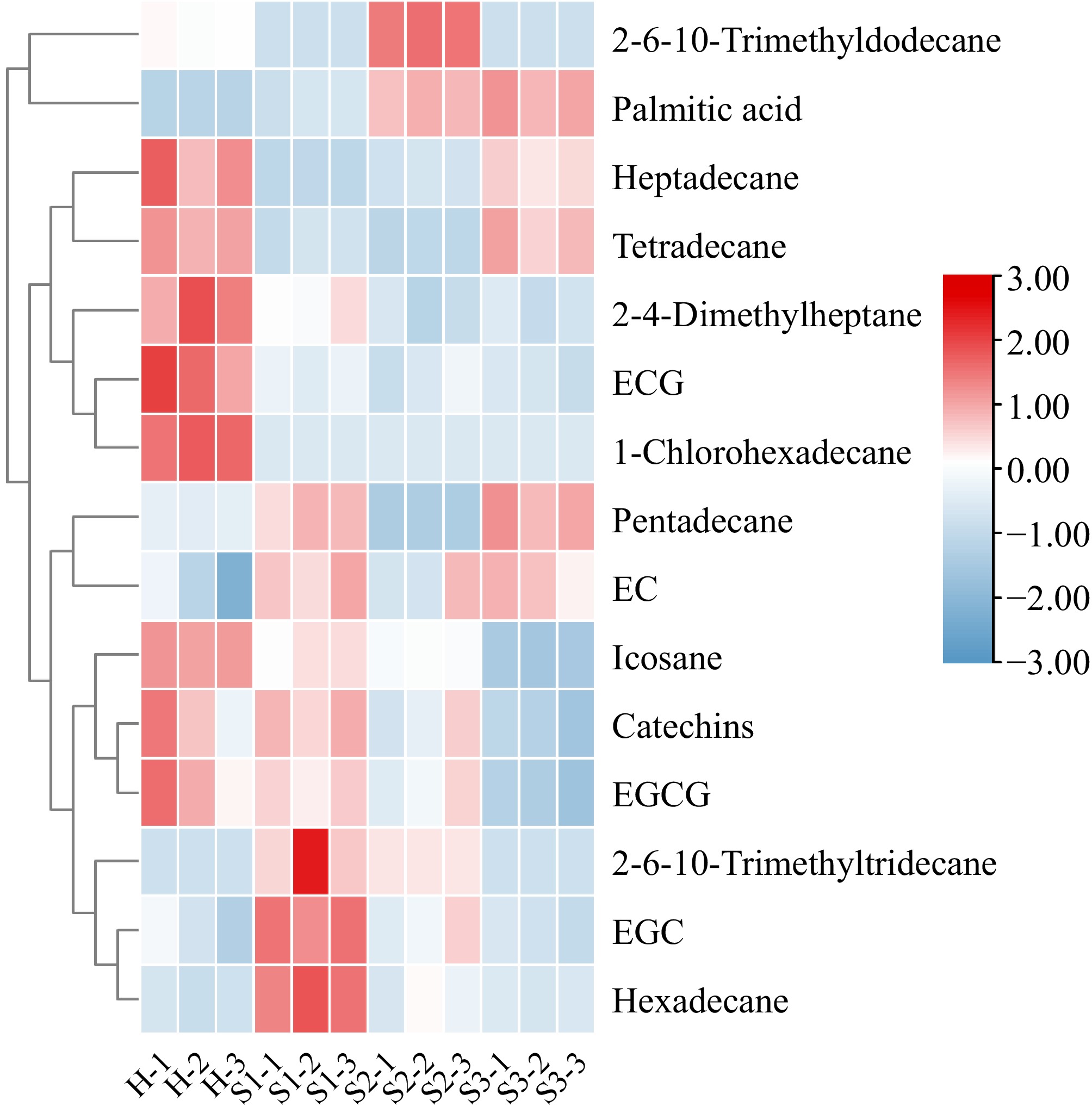

The microbial communities on leaves are closely related to the biosynthesis of plant metabolites. During the development of blister blight, both the microbial communities and the chemical composition of tea leaves undergo significant changes. The bioactive substances synthesized by plants can influence the composition of the associated microbial community. To investigate the responses of the main chemical constituents in tea leaves during blister blight progression, we analysed the contents of tea polyphenols, catechins, alkaloids, and volatile constituents in tea leaves at different stages of the disease progression (Supplementary Tables S7 & S8). Figure 5a presents a PLS-DA score plot that displays distinct segregation among the H, S1, S2, and S3 samples, suggesting notable variations in the main chemical constituents of tea leaves at different stages of blister blight development. The predictive effectiveness of the PLS-DA model, without overfitting, was confirmed through R2 and Q2 permutation tests (Fig. 5b). A total of 15 significantly different metabolites were identified (variable importance projection > 1 and p < 0.05) and visualized using heatmap analysis (Fig. 6). Catechins content decreased significantly during infection. Moreover, EGCG showed the same pattern as total catechins. Additionally, ECG levels decreased during infection, while EC was primarily detected during the S1 and S3 stages, and EGC was mainly detected in the S1 stage. Alkane components were identified as characteristic volatiles across the disease stages. Levels of 2,4-dimethylheptane, icosane, 2,6,10-trimethyltridecane, and hexadecane decreased as the disease progressed. In contrast, the levels of tetradecane and heptadecane increased substantially. The levels of pentadecane decreased initially and then increased with the intensity of infection, reaching its lowest point at the S2 stage. The levels of 1-chlorohexadecane remained largely unchanged throughout the course of infection. Levels of 2,6,10-trimethyldodecane were significantly higher in the S2 stage than in the S1 and S3 stages. Additionally, palmitic acid levels were significantly higher in the S2 and S3 stages.

Figure 5.

Multivariate statistical analysis for the differences in the metabolites of tea leaves at different disease development stages. (a) PLS-DA score plot; (b) permutation tests for the PLS-DA score plot. H, healthy leaves; S1, tea leaves in the early disease stage; S2, tea leaves in the middle disease stage; S3, tea leaves in the late disease stage.

Figure 6.

Heatmap analysis of differentially abundant metabolites. H, healthy leaves; S1, tea leaves in the early disease stage; S2, tea leaves in the middle disease stage; S3, tea leaves in the late disease stage. The samples are clustered according to the similarities among their constituents and arranged in a horizontal order. Red represents the more abundant metabolites in the corresponding group, and blue represents the less abundant metabolites.

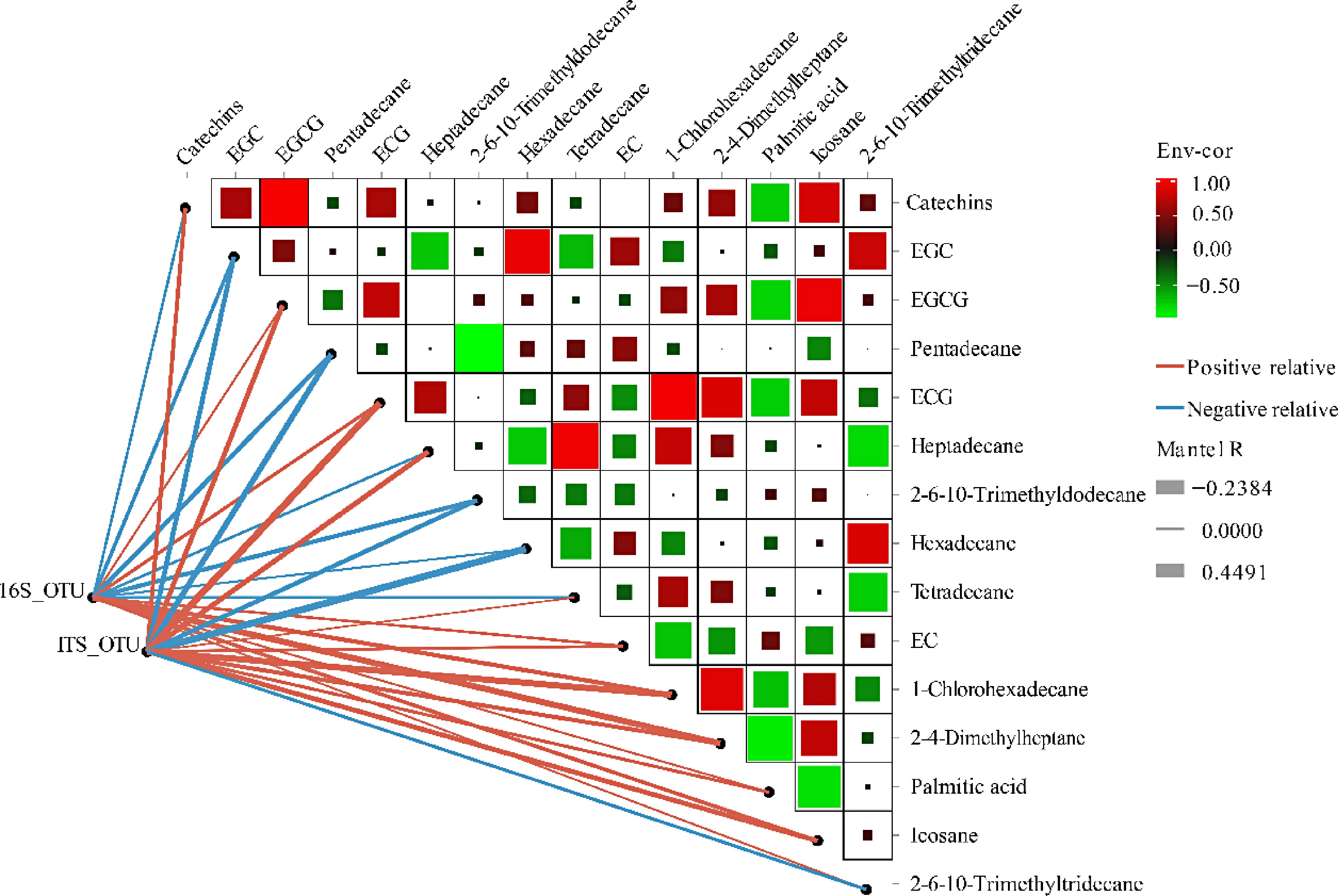

A partial Mantel test was performed to compare the distance-corrected dissimilarities of microbial communities with those of the main chemical components (Fig. 7). The results revealed positive correlations between microbial community OTUs and several chemical compounds, including ECG, 1-chlorohexadecane, heptadecane, icosane, EGCG, 2,4-dimethylheptane, and catechins, with Mantel's r = 0.45, 0.40, 0.31, 0.29, 0.29, 0.23, and 0.22, respectively. In contrast, hexadecane exhibited a negative correlation with the OTUs of the fungal community, according to Mantel's r = −0.24. Among the bacterial sequences, 2,4-dimethylheptane, and 1-chlorohexadecane showed strong positive correlations with the OTUs, with Mantel's r = 0.39 and 0.24, respectively.

Figure 7.

Correlation of microbial communities with main biochemical components determined by the partial Mantel test. Pairwise comparisons of metabolites are shown with a color gradient denoting Spearman's correlation coefficients. OTU composition in relation to metabolites determined by partial Mantel tests. Edge width corresponds to Mantel's R statistic for the corresponding distance correlations.

-

The phyllosphere encompasses a diverse array of microorganisms that interact with host plants, influencing their health and function. While numerous studies have investigated plant-pathogen interactions and disease mechanisms, the regulatory mechanisms governing the defence of the entire phyllosphere community against plant diseases have been largely overlooked. Therefore, our study primarily examined changes in the diversity and composition of microorganisms in tea leaves across different developmental stages of tea blister blight. This study is crucial for assessing the role of microorganisms in maintaining a healthy ecosystem and aiding in the identification of specific microorganisms with antagonistic properties against pathogens.

To examine the variety of microbial communities, this study employed α-diversity analysis, specifically the Sobs, Chao1, and Shannon indices. The results revealed a significant reduction in the richness and diversity of the fungal community (Table 1). This decrease indicates a strong negative correlation between fungal α-diversity and the progression of tea blister blight. Conversely, the bacterial α-diversity remained largely unaffected during pathogen infection. This difference suggests that the bacterial and fungal communities exhibit distinct dependencies on the host plant, as noted by Li et al.[38]. Specifically, fungal communities appear more susceptible to disturbances when the host plant is attacked by plant-pathogenic microorganisms. PCoA was employed to visualize β-diversity and demonstrate clear clustering patterns between control samples and tea leaves at different disease stages. Additionally, the microbiota composition was significantly dissimilar among the different disease stages (Fig. 1b). This dissimilarity was further supported by the presence of distinct proportions of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) in leaves at various disease stages (Fig. 2). Previous studies have reported changes in the diversity and community structure of plant-associated microbes when exposed to pathogenic microorganisms[39−41]. The observed alterations in the phyllosphere microbiota of healthy and diseased tea leaves imply the occurrence of interactions between beneficial and pathogenic organisms within the phyllosphere regions. These potentially influencing the activation or suppression of plant immune responses.

It is widely believed that the majority of these phyllosphere bacteria are nonpathogenic and confer benefits to plant growth and resistance against pathogens[42]. Examination at the phylum level indicates that Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria are the primary constituents of bacterial communities found in different plants, such as lettuce, spinach, wheat, apple, and naturally existing plants[43,44]. These findings are consistent with previous reports, suggesting that Proteobacteria is the main phylum discovered on tea leaves, making up a percentage ranging from 77.85% to 93.62% (Fig. 3a). Among the Proteobacteria, Sphingomonas, a member of the α-Proteobacteria class, was the most prevalent community member. Previous studies have highlighted the plant-protective effects of Sphingomonas, including the suppression of disease symptoms and a reduction in pathogen growth[12,43]. The observed disease suppression did not result in a significant alteration in the abundance of Sphingomonads (Fig. 3b). Sphingomonads can utilize a wide range of substrates, facilitated by the presence of various transport proteins, including TonB-dependent receptors[45]. This ability serves as an alternative adaptive mechanism for competing with pathogenic microorganisms in resource-limited environments, resulting in a remarkable affinity. Additionally, Methylobacterium represents a prevalent and beneficial bacterial population within the phyllosphere, offering advantages to plants. In the S1 stage, the abundance of Methylobacterium decreased to 56.5% of that in healthy leaves (Fig. 3b). However, in the S2 and S3 stages, the relative abundance of Methylobacterium rebounded to a level comparable to that of healthy leaves (Fig. 3b). Methylobacterium species can utilize plant-derived methanol as their primary carbon source, thereby enhancing plant immune defense and protecting against UV radiation. However, the specific mechanisms underlying these defense processes remain unidentified[46]. The genus Klebsiella is widely distributed in various environments, including humans, animals, and plants[47]. Under normal circumstances, Klebsiella bacteria are typically nonpathogenic to plants[48]. For example, Klebsiella pneumoniae, a nitrogen-fixing plant endophyte, is known to promote plant growth, but it is also a common opportunistic pathogen that causes pneumonia in humans[49]. The prevalence of Klebsiella was found to be highest during the S1 stage of tea leaf growth (Fig. 3b), potentially increasing the risk of microbial transmission to humans. Several Aureimonas strains have been obtained from plant leaves[50,51]. Notably, in healthy tea leaves, Aureimonas, which encompasses several species that participate in the cycling of carbon and nitrogen[52], was more prevalent (Fig. 3b).

Ascomycota is the largest phylum of the fungal kingdom[53] and aligns with the findings of our study. The genera Cladosporium, Didymella, and Colletotrichum within the Ascomycota phylum were more prevalent in diseased S1–3-stage tea leaves than in healthy leaves, suggesting their role as aetiological agents. Cladosporium species are commonly observed in various plant species, such as wheat, Heterosmilax japonica, and Atriplex canescens, where they serve as significant plant pathogens[54,55]. Two Didymella species (D. theae and D. theifolia) have been identified and characterized as the causative agents responsible for the occurrence of tea leaf brown-black spot disease[56]. Colletotrichum, a genus comprising more than 189 species, is widely recognized as a prominent plant pathogen on a global scale[57]. Among these species, Colletotrichum camelliae is a dominant fungal pathogen affecting tea plants, causing anthracnose disease in tea leaves, which significantly reduces both tea yield and quality[58]. In contrast, disease stress led to a significant reduction in the populations of Septoria and Taphrina, potentially attributable to the loss of their competitive advantage in the acquisition of space and nutrients in the face of pathogenic competition. Basidiomycota presented a relatively lower abundance. The genus Exobasidium within Basidiomycota encompasses more than 170 species worldwide[59]. E. vexans, which belongs to a certain group within Exobasidium, primarily affects the delicate foliage and stems of tea plants[24]. During the S1−S3 stage, the relative abundance of Exobasidium was 2.3-fold, 15.8-fold, and 15.4-fold greater than that in healthy leaves. The noted increase aligns with the changes occurring in tea leaves at various phases of tea blister blight. Our findings were consistent with the changes observed in endophytic fungal communities, indicating an increase in the proportion of Exobasidium[60]. Additionally, the progression of tea blister blight led to a slight increase in the relative abundance of Bulleromyces and Hannaella, while the relative abundance of Sporobolomyces, Tilletiopsis, and Erythrobasidium showed a minor decrease.

The diversity and composition of the microbiota in healthy and diseased tea leaves suggest the occurrence of potential interactions between beneficial and pathogenic microorganisms in the phyllosphere region. Within host plants, nonpathogenic microorganisms rapidly proliferate and compete for limited resources[61,62]. Various antimicrobial compounds, including phenazines, pyoluteoria, pyrrolnitrin, cyclic lipopeptide surfactants, and bacteriocins, can antagonize and inhibit the colonization and propagation of pathogens[49,63]. Furthermore, interactions between plants and microorganisms can trigger induced systemic resistance (ISR), priming the entire plant to respond to both abiotic and biotic stressors[13]. Co-occurrence analysis further revealed the intricate nature of microbial interactions, encompassing both positive and negative relationships (Fig. 4). Highly connected OTUs were identified as the main connecting nodes and major players in microbial community formation[15]. These OTUs, which included Pseudomonas, Aureimonas, and Bulleromyces, were found to be nonpathogenic microorganisms and have the potential to be utilized as beneficial biological control agents against tea blister blight.

The phyllosphere microbiome is closely linked to the biosynthesis of plant metabolic substances. The presence of carbon-based nutrients in leaves is widely believed to be a significant determinant of the colonization of phyllosphere microbes[11]. In turn, plants can actively influence their associated microbial communities through the synthesis of bioactive substances. Among these, phenolic compounds are the primary chemical defense agents in plants, accumulating notably at infection sites and triggering the production of reactive oxygen species[64]. Leaves infected with grey blight exhibited increased levels of GCs and ECs, which may enhance the tea plants' resistance to pathogen-induced damage[65]. Following inoculation with C. fructicola, the levels of EGCG and C in the ZC108 cultivar (resistant) increased more significantly than those in the LJ43 cultivar (susceptible). However, no notable changes in the levels of EC and EGC were observed in ZC108[66]. This study revealed significant accumulation of the nonester catechins EC and EGC after infection with tea blister blight (Fig. 6). It is reasonable to hypothesize that catechin monomers fulfill distinct functions in safeguarding tea plants against various pathogens. Researchers have consistently focused on the role of volatile compounds in inter- and intra-plant communication. These compounds have been shown to trigger herbivore resistance through jasmonic acid and to enhance both cold and to drought tolerance in tea plants[67,68]. The availability of volatile compounds in plant roots as a means of fighting infection has been highlighted in several studies[69]. The antimicrobial activity of various alkane components, including tetradecane, pentadecane, hexadecane, heptadecane, heneicosane, and docosane, has been demonstrated[70]. In tea leaves affected by blister blight disease stress, increased concentrations of 2,6,10-trimethyldodecane and pentadecane (Fig. 6) may enhance the immune response against fungal infection. Moreover, palmitic acid showed a similar trend. Positive and negative correlations between operational taxonomic units (OTUs) and main biochemical components were observed (Fig. 7), which could lead to the selective enrichment of phyllosphere microorganisms. These findings may provide a theoretical basis for developing effective biocontrol agents against tea blister blight and enhance our understanding of the relationship between the phyllosphere microbiome and tea plant health.

This study analysed the changes in the composition and diversity of tea leaf microbial communities during the development of tea blister blight. However, the distribution patterns of bacteria and fungi in tea leaves were not examined, and it was not possible to confirm whether the microorganisms were evenly distributed or concentrated in tea leaves. With the continuous deepening of related research, the analysis of microbial community structure will play an important role in the study of microbial pathogenic mechanisms and green prevention and control in tea gardens.

-

The objective of our research was to examine the changes in phyllosphere microorganisms throughout the various phases of tea blister blight infection. As the disease progressed, the fungal population exhibited a decrease in both richness and diversity, whereas no notable differences were detected in the bacterial Sobs, Chao1, or Shannon indices between healthy and diseased tea leaves. Compared with those in the phyllospheres of unaffected plants, the compositions of the bacterial and fungal communities in the phyllospheres of tea plants affected by blister blight disease exhibited notable differences. The co-occurrence analysis conducted in this study delved deeper into the primary connecting microorganisms and revealed the occurrence of intricate interactions among them. The biosynthesis of plant metabolic substances was influenced by the occurrence of tea blister blight. Certain components, such as catechins and alkanes, exhibited strong correlations with alterations in the microbial community, suggesting their potential for mitigating fungal infection in tea plants. Understanding the fluctuating dynamics of phyllosphere microbial communities during various stages of disease progression will facilitate the cultivation of biocontrol microorganisms, curtail reliance on chemical interventions, and yield superior tea products.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Liu S; data curation: Guo N, Jin J, Zhang Q; visualization: Guo N, Jin J, Jiang Q; formal analysis: Jin J, Jiang Q; funding acquisition: Liu S, Yu Y; investigation: Zhang Q, Guo N; supervision: Liu S, Yu Y; draft manuscript preparation: Liu S; project administration: Guo N; review and editing: Yu Y, Jin J. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The data presented in this study are deposited in the NCBI database under BioProject accession number PRJNA1050022.

-

We thank Guangzhou Goldenovo Biotechnology Co., Ltd, for sequencing the samples. We thank the instrument-sharing platform of the College of Horticulture of Northwestern A&F University for instrument sharing.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Nini Guo, Jiayi Jin

- Supplementary Table S1 Primer information used in the study.

- Supplementary Table S2 Gene PCR amplification system.

- Supplementary Table S3 Gene PCR amplification procedure.

- Supplementary Table S4 Quantitative statistics of microbial OTUs and tags.

- Supplementary Table S5 Abundance of the dominant OTUs.

- Supplementary Table S6 Co-occurrence network.

- Supplementary Tables S7 Relative contents of nonvolatile components in leaves at different disease development stages.

- Supplementary Tables S8 Relative contents of volatile components in leaves at different disease development stages.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Rarefaction curves for the observed operational taxonomic units (OTUs) for all the samples. (a) Bacterial community; (b) Fungal community.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Guo N, Jin J, Zhang Q, Jiang Q, Yu Y, et al. 2025. Characterizing the alterations in the phyllosphere microbiome in relation to blister blight disease in tea plant. Beverage Plant Research 5: e015 doi: 10.48130/bpr-0025-0004

Characterizing the alterations in the phyllosphere microbiome in relation to blister blight disease in tea plant

- Received: 02 September 2024

- Revised: 12 January 2025

- Accepted: 03 February 2025

- Published online: 06 June 2025

Abstract: Tea blister blight is a significant leaf disease that affects tea plant (Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze), severely impacting global tea production. This study provides a dynamic characterization of the phyllosphere microbiome of tea leaves in response to the progression of this disease. For this investigation, we utilized a blend of 16S ribosomal RNA (16S rRNA) and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) amplicon information to analyse the changes in the phyllosphere microbiome concerning different degrees of blister blight disease. The results indicated that the α-diversity of the fungal community was higher on healthy tea leaves than on diseased ones. However, no significant differences were observed in the bacterial Sobs, Chao1, or Shannon indices between healthy and diseased leaves. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA), linear discriminant analysis (LefSe), and redundancy analysis revealed potential interactions between beneficial and pathogenic microorganisms within the phyllosphere. Co-occurrence network analysis identified key microbial taxa that serve as central nodes in the microbial interaction network. Some nonpathogenic microorganisms showed promise as potential biological control agents against tea blister blight. Additionally, changes in key biochemical constituents of the tea leaves were examined. The presence of abundant epicatechin gallates and specific alkane compounds was found to potentially enhance the tea plants' resistance to fungal infection. These findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the relationship between the phyllosphere microbiome and the health of tea plants.

-

Key words:

- Tea plant /

- Phyllosphere microbiome /

- Tea blister blight /

- Microbiome diversity /

- Microbial community