-

Nitrogen (N) is a fundamental nutrient element of living organisms, and its biogeochemical cycle maintains the stability of ecosystems. The global nitrogen biogeochemical cycle plays a foundational role in maintaining ecosystem stability—it not only supports biodiversity conservation by regulating primary productivity but also contributes to carbon sink formation through its coupling with terrestrial and aquatic carbon cycles[1,2]. The large-scale application of synthetic fertilizer since the 19th century has provided approximately 48% of the global grain production[3], serving as a core pillar for safeguarding food security. However, excessive nitrogen input and extensive management have triggered multi-sphere environmental problems, leading to nitrate pollution in groundwater[4], soil acidification[5], and air pollution[6]. More critically, driven by global population growth, the demand for nitrogen fertilizers continues to rise at a rate of 2.8% to 3.7% per year[7]. This trend has further intensified the inherent contradiction between 'ensuring nitrogen supply for food production' and 'preventing and controlling nitrogen-related environmental pollution'—a dilemma that has become a key constraint on global sustainable development. Consequently, the importance of scientific nitrogen management in reconciling food security, environmental protection, and climate goals has become increasingly prominent, highlighting its crucial role in advancing global sustainable development agendas[8].

Over the past three decades, agricultural activities have been the dominant driver of increased nitrogen emissions and environmental impacts-accounting for two-thirds of the total growth in global nitrogen inputs to terrestrial ecosystems. Specifically, agricultural nitrogen contributes 60% to 70% of global N2O emission[9], and ammonia emissions from crop and livestock systems have increased by 128% and 45% respectively[10]. Economically, the global annual losses associated with nitrogen pollution—including costs of water treatment, crop yield losses due to soil degradation, and public health expenditures-amount to tens of billions of US dollars annually[11]. The crop-livestock system is the core carrier of the nitrogen cycle. Circular agriculture that integrates crop production with livestock is an efficient approach to reducing the use of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers, promoting the recycling of livestock manure, and alleviating global nitrogen surplus[12]. However, this integrated system has been disrupted by rapid agricultural intensification and specialization: for example, in China, the number of smallholder farmers engaged in both crop cultivation and livestock breeding decreased by 59% from 1986 to 2017[13]. The current situation of separation between crop and livestock production has led to low nutrient use efficiency. Compounding this issue, intensive livestock operations generate large amounts of manure that are often discharged disorderly due to high treatment costs, and technical limitations, further exacerbating environmental risks[14,15].

Basins are complex systems crossing natural geographical and administrative boundaries. Endowed with fertile soils and abundant water resources, they are global core regions for crop cultivation and livestock rearing, making them hotspots of anthropogenic nitrogen cycling. Meanwhile, basins are also key links in the multi-medium migration of nitrogen across the 'crop − livestock − soil − atmosphere − water body' chain. In typical agricultural basins, nitrogen input from chemical fertilizers, food and feed import accounts for 58% to 97% of the total nitrogen input[16]. Consequently, agricultural nitrogen loss directly exacerbates surface water pollution and lake eutrophication[17,18]. The ecological health of basins is also closely tied to achieving water resource management (SDG 6), and ecosystem protection (SDG 15)[19]. China has a dense network of river systems and a variety of river basin types. Currently, the basins are confronted with such challenges as river dry-up, worsening non-point source pollution, and prominent contradictions between human activities and ecological carrying capacity[8], which have forced the transformation of crop and livestock production models in these basins. Therefore, basin-scale crop and livestock nitrogen management has become a critical point for breakthrough in operationalizing green development.

To address the aforementioned gaps and challenges in current basin nitrogen management, this review systematically synthesizes domestic and international research findings across four interrelated themes: (1) driving factors of nitrogen flow in the basin; (2) the establishment of science-based environmental goals; (3) the efficacy and applicability of nitrogen reduction measures; and (4) existing proposals for optimizing basin nitrogen management. Building on this synthesis, a collaborative, regionalized, and refined basin nitrogen management system is proposed. This system aims to provide theoretical and practical support for promoting the green transformation of agriculture—specifically, enhancing nitrogen use efficiency, reducing environmental pollution, and reconciling food security with ecological protection in basin contexts.

-

The nitrogen flow in a basin is a comprehensive manifestation of the 'source–sink' process, encompassing the identification of nitrogen source and sink, as well as the transfer pathways between them. The analysis of its characteristics and driving forces forms the basis for implementing precise management. Domestic and international research has gradually conducted in-depth attribution analysis through various models, exploring different driving factors in various aspects, thereby providing a scientific basis for identifying key control nodes in basin nitrogen management.

Research on basin nitrogen management started relatively early overseas. Nutrient flows in foreign basins exhibit diverse characteristics. For instance, the assessment results of NANI/NAPI (net anthropogenic nitrogen/phosphorus inputs) in the Baltic Sea basin show a pattern of low levels in the north and high levels in the south, with a strong correlation between nitrogen inputs and total nitrogen fluxes in rivers[20]. A comprehensive hydrological model of the Rhine and Elbe river basins in Europe confirms that nitrogen emissions are positively correlated with soil nitrogen surpluses, and nitrogen emissions show significant seasonal fluctuations[21]. Water quality model analysis indicates that the Finnish river basin is dominated by bioavailable nitrogen output, and nitrogen loads present a spatial pattern of high levels in the southwest and low levels in the northeast, which is affected by the distribution of intensive agricultural areas[22]. Marine ecosystem models have diagnosed that nitrogen enrichment in the Mediterranean Sea basin has continued to intensify from 1950 to 2030, with reactive nitrogen inputs doubling and potentially continuing to increase until 2030[23]. In the Po River basin in northern Italy, which is strongly influenced by human activities, the temporal and spatial variations of nitrogen budgets are significantly correlated with reactive nitrogen loads[24]. In contrast, basins in China are characterized by the dominance of agricultural sources. Studies on the Lizixi Basin of the Jialing River combined global climate models and distributed hydrological models[25]. In the Yangtze River basin, by integrating the WOFOST (WOrld FOod STudy) model, the NUFER (NUtrient flows in Food chains, Environment and Resources use) model, and the MARINA (Model to Assess River Input of Nutrient to seAs) model, the crop type-dominated nitrogen input structure was analyzed, and the temporal-spatial dynamics and retention effects of nitrogen flow were clarified[26,27].

The driving factors affecting basin nitrogen cycles can be categorized into two types. Among anthropogenic factors, agricultural chemical fertilizer application, livestock and poultry breeding waste, and food trade are common drivers. The coupling relationship between agricultural production and nutrient management directly affects the degree of nitrogen pollution in water bodies[28], and the acceleration of urbanization has also influenced changes in nitrogen flows[29]. Studies by Zhao et al.[30] and Yang et al.[31] found that the sources of nitrogen and phosphorus emissions in the Baiyangdian basin have shown a trend of shifting from traditional agricultural sources to domestic human sources. Research has found that atmospheric nitrogen deposition is an important contributor to the annual total nitrogen load in densely populated areas of the Yellow River basin[32]. Meanwhile, driven by land use changes and agricultural expansion, the nitrogen input hotspots in the Yellow River basin have shifted northwestward in the past 40 years[33]. In the Chaohu basin, the INFA (Integrated Nutrient Flux Analysis) model was developed and analysis based on this model revealed that agricultural management, urbanization rate, and changes in population consumption structure were the key factors driving changes in nutrient flow patterns over the past 40 years. Meanwhile, changes in basin land use have promoted the intensification of nitrogen flow, which also reflects the profound impact of human activities on basin nitrogen cycles[34]. Natural factors are mainly dominated by climate warming[23], cropping structure[26], and topographic regulation[27], and the interactive effects of climate change and cropping structure adjustments on basin runoff and nitrogen loss are significant. Atmospheric nitrogen deposition is gradually becoming an important nitrogen source for eutrophic lakes and should be incorporated into basin nitrogen management systems[28]. In addition, the Chesapeake Bay watershed is affected by multiple driving factors, where livestock and poultry manure, chemical fertilizers, and atmospheric deposition collectively contribute more than 90% of the nitrogen load[29]. Recently, a comprehensive model (CHANS-CN) for quantifying carbon and nitrogen fluxes has been developed in China. The research results indicate that integrated carbon and nitrogen management is a key direction for optimizing the cost-effectiveness of environmental policies[35].

In summary, existing studies have clarified the dominant role of agricultural activities in basin nitrogen flow using model tools. Although there are numerous types of nutrient flow models, most of them focus on the analysis of a single system and a single factor (Table 1). Given this cross-system nature of the nitrogen cycle, the traditional single-system, single-factor modeling approach is no longer sufficient. Instead, it is essential to adopt a multi-model coupling strategy: this method enables integrated analysis across multiple systems, thereby aligning with the holistic characteristics of nitrogen flow. To enhance the practical value of such research, greater attention must be paid to analyzing how interactions between multiple factors influence nutrient processes. Only by incorporating these multi-factor interaction effects can we develop nutrient management plans that are more comprehensive, scientifically robust, and adaptable to real-world complexity.

Table 1. Overview of nutrient flow model.

Model Scale and type Advantages Disadvantages VEMALA A national scale nutrient loading model for Finnish catchments. The detailed information such as the soil type, slope and crop distribution of the farmland

can precisely quantify the contribution of agricultural non-point source pollution.Simulation deviation under complex environmental conditions, high reliance on real-time water quality data, with limited application. WMS A simulating the hydrology and hydraulics

of a river basing model.Support multi-level simulation from sub-basins to the entire basin, which can quantify the impact of agricultural non-point source pollution on downstream water quality. The core of WMS lies in hydrological process simulation, but it is relatively weak in depicting the key elements of agricultural production. SWAT A distributed hydrological model in which the watershed is used as a scale and a daily time unit. Comprehensive process simulation of hydrology - water quality - vegetation in the basin. The model mainly focuses on the simulation of hydrology and water quality, but it lacks in the simulation of various aspects of agricultural production. MARINA A multi-domain and multi-version environmental assessment model that quantifies the migration process of pollutants from land to water bodies. Identify the sources of pollutants and predict the environmental impacts. Insufficient detailed analysis of the entry of nutrients into the water body's front end. WOFOST A crop growth model based on physiological and ecological mechanisms, applicable to global, regional, and field-scale. Predict the impacts of climate change and field management on crop production. The model focuses on the study of crop mechanism growth and requires the integration of other models to assess the impact of the crop production environment. NUFER A model that covers different levels such as global, national, river basin, and farmers, and quantifies the entire nutrient flow of the food system. The full-chain simulation of nutrients can identify the key links where nutrients are inefficiently utilized. Specialized modules can

be developed for different crops and animals production.The model does not incorporate a multi-factor synergy algorithm and ignores the interaction effects of multiple nutrients. GCM A simulating global climate change model. The model can understand the mechanisms of climate change, predict future climate scenarios, and assess the impacts of climate change. It is necessary to couple with models from other industries in order to assess the impact of climate change on multiple fields. CHANS-CN A comprehensive model for quantifying the historical evolution and future trends of carbon and nitrogen emissions in China. It integrates 16 subsystems related to humans and nature, covering the entire chain of the carbon and nitrogen cycles. Applied to large-scale studies, but insufficient for detailed analysis on smaller scales. -

To achieve green development in agriculture, clear management goals need to be set. The nitrogen environmental threshold serves as the scientific basis for balancing agricultural production and environmental risks. The concept of nitrogen environmental thresholds traces back to the 1970s, when Swedish scientists first proposed the idea of a 'critical load'. They defined this term as the largest amount of pollutants an ecosystem can take without causing long-term harm to itself[36]. The proposal of this concept marked the official entry of nitrogen overload into the research focus of the academic community. Since then, the international scientific community has launched a number of assessment programs centered on nitrogen thresholds. Early research focused on optimizing agricultural production while controlling nitrogen inputs. For instance, through long-term field experiments, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) found that the increase in crop yield was no longer significant when nitrogen application for corn exceeded 200 kg·hm−2. This conclusion became an important reference for early farmland nitrogen application thresholds[37]. The European Union (EU) issued the Nitrates Directive in 1991, which clearly stipulated that the threshold for nitrate concentration in groundwater should be ≤ 50 mg·L−1, and the nitrogen load from manure should be limited to 170 kg·hm−2·yr−1[38,39]. This directive became a crucial milestone in the transition of nitrogen management from theoretical research to policy practice, providing a policy framework for subsequent cross-border and cross-regional nitrogen control. In 1998, a study by Aber et al. proposed the nitrogen saturation threshold for forest ecosystems. They pointed out that when nitrogen input exceeded 10–20 kg N hm−2·yr−1, the nitrogen leaching rate of forest ecosystems would increase exponentially—a trend that threatens the stability of the ecosystem[40]. In 2009, Rockström et al. proposed the theoretical framework of planetary boundaries and pointed out that human activities at that time, human utilization of synthetic ammonia, exceeded the safe threshold by 150%[41]. When updating the framework in 2015, they further emphasized that excessive nitrogen is a core driver of multiple pollution problems[42]. The latest research shows that six out of the nine planetary boundaries have been crossed, and the safe operating space for the Earth's environment is continuously shrinking[43]. The current definition range of relevant thresholds is generally wide, and in research and application, global or national unified threshold standards are mostly adopted. In contrast, localized threshold studies for specific regions are extremely scarce, which directly leads to a lack of scientifically precise threshold targets at the regional level as the basis for decision-making.

In recent years, research on thresholds at regional and industry scales has become a hot topic. In the UK, for instance, studies have examined how nitrogen and phosphorus limits in streams and rivers influence eutrophication processes. These investigations revealed that even when phosphorus levels are controlled, high nitrogen loads continue to pose a significant threat to aquatic ecosystem health[44]. Meanwhile, in the US corn belt—a major agricultural region characterized by intensive corn cultivation—a 30-year long-term field experiment provided critical data on nitrogen application thresholds. The study demonstrated that when nitrogen application rates exceeded 224 kg N hm−2, two key issues arose: nitrogen use efficiency (the proportion of applied nitrogen taken up by crops) declined sharply; and the risk of nitrate leaching (a primary cause of groundwater contamination) increased dramatically[45].

In China, long-term field experiments in farmland provide a foundation for setting these thresholds. For example, a study on the wheat-corn rotation system in the North China Plain found that when nitrogen application exceeds 200 kg·hm−2·yr−1, the crop yield increase rate is less than 1%, while the risk of nitrogen leaching rises by three to five times[46]. At the county level, China has released nitrogen fertilizer application quotas for major food crops. Practice shows these quotas can reduce fertilizer use by 21%–28%, increase nitrogen productivity by 26%–33.2%, and cut nitrogen loss by 23.2%–28.9%[44]. For water environment thresholds, a national-scale study was conducted to establish safe nitrogen capacity thresholds for freshwater environments in each province[47]. In some basins, studies have worked backward to set the maximum allowable nitrogen input for farmland based on water quality goals[31]. This creates a management system linking water quality and nitrogen input. In the livestock system, China's Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs proposed a method for calculating livestock breeding capacity centered on nitrogen balance for the first time in 2017. At the same time, supporting technical standards were released—such as wastewater discharge standards for livestock farms and nutrient content standards for compost products.

In the past, the setting of thresholds was significantly limited in terms of considerations, mostly focusing on a single isolated production process, or only considering a single environmental interface such as the atmosphere, water body, or soil. It failed to cover the interactive effects of multiple links and the interplay of multiple media. Recent studies have shifted towards assessing environmental impacts from the atmosphere, water bodies, and soil collectively, and have established a calculation method for multi-indicator nitrogen thresholds in crop-livestock systems of basins[48]. Emerging studies have comprehensively incorporated the effects of multiple nutrients, based on the temporal variabilities in key periods of total nitrogen (TN), total phosphorus (TP) loss, and methane emissions. It proposed novel multi-objective irrigation strategies to optimize water management[49]. Likewise, leveraging pollution emission inventories and source apportionment results, researchers have delineated regional emission thresholds for chemical oxygen demand, ammonia nitrogen, TN, and TP[50]. However, there are still few relevant studies, and most of them use static thresholds. Moreover, future research needs to take into account more nutrient elements and combine joint dynamic monitoring points to regularly set more detailed thresholds. There is an urgent need to develop a regional threshold target-setting method that integrates multiple interfaces and multiple elements (Fig. 1).

-

The separation of crop and livestock is the main cause of nitrogen imbalance in basins. In contrast, the integrated crop and livestock approach, which achieves a closed-loop of nutrients between manure and farmland, has become a key path to reduce the reliance on synthetic nitrogen fertilizers and improve the efficiency of nitrogen cycling. Globally, including in both domestic and international contexts, practical experiences with this integrated approach have been accumulated across multiple scales.

In the process of global agricultural intensification transformation, the separation of crop and livestock areas has led to a worsening of nutrient imbalance[51]. The regional distribution of crop and livestock in China is uneven[52,53]. Over the past 30 years, the number of rural households engaged in both crop growing and livestock raising has dropped by 59%[13]. A large amount of livestock manure cannot be returned to the fields nearby, which not only causes waste of nitrogen resources but also increases the risks of ammonia volatilization in the atmosphere and water body eutrophication[17,18]. Globally, the livestock supply chain emits 65 teragrams (Tg) of nitrogen annually, accounting for one-third of all human-caused nitrogen emissions. Asia accounts for 66% of these emissions, with China contributing a large share[54]. Given this context, improper manure management has become a critical source of nitrogen loss in river basins.

Research has confirmed that the integration of crop and livestock can achieve a win-win situation for both production and ecology. Internationally, the European Union adopted the 'Nitrate Directive' to ensure that the scale of livestock farming is in line with the nitrogen absorption capacity of local farmland[38]. Denmark enacted the 'Agricultural Nitrogen Management Law' to set a threshold for the nitrogen input from pig farms, and at the same time implemented the 'nitrogen tax' policy to promote the cross-regional transfer of manure, or the processing of organic fertilizers[55]. In the Midwestern United States, a limit on the annual application of manure nitrogen was set for intensive dairy farming to reduce the risk of eutrophication in the Mississippi River basin[56]. Domestic practices have more regional characteristics. The research on integrated farming and breeding in northern China (based on Life Cycle Assessment LCA and Data Envelopment Analysis DEA) shows that farms with abundant arable land can achieve a high level of integration of crop and livestock. In the integrated system, the nitrogen footprints of crop production and pig production were 12.02% and 19.78% lower than those in the separated system, respectively. The total nitrogen footprint of the integrated system decreased by 17.06%[12]. Researchers have built a conceptual model for agricultural waste. They suggested that in multi-village agricultural complexes, adjusting crop planting structures to match livestock breeding scales and agricultural product processing industries can achieve 'zero waste emission'[52]. At the basin scale, the optimal ratio of manure substitution for chemical fertilizer was identified, while the spatial configuration of large-scale crop-livestock integration was proposed[57]. Additionally, in 2017, China launched initiatives for 'recycling livestock manure', and 'replacing chemical fertilizers with organic fertilizers in fruit, vegetable, and tea cultivation'. In 2021, pilot counties for green circular agriculture were established to speed up the application of these technologies.

Technology system and integrated application for nitrogen reduction in basins

-

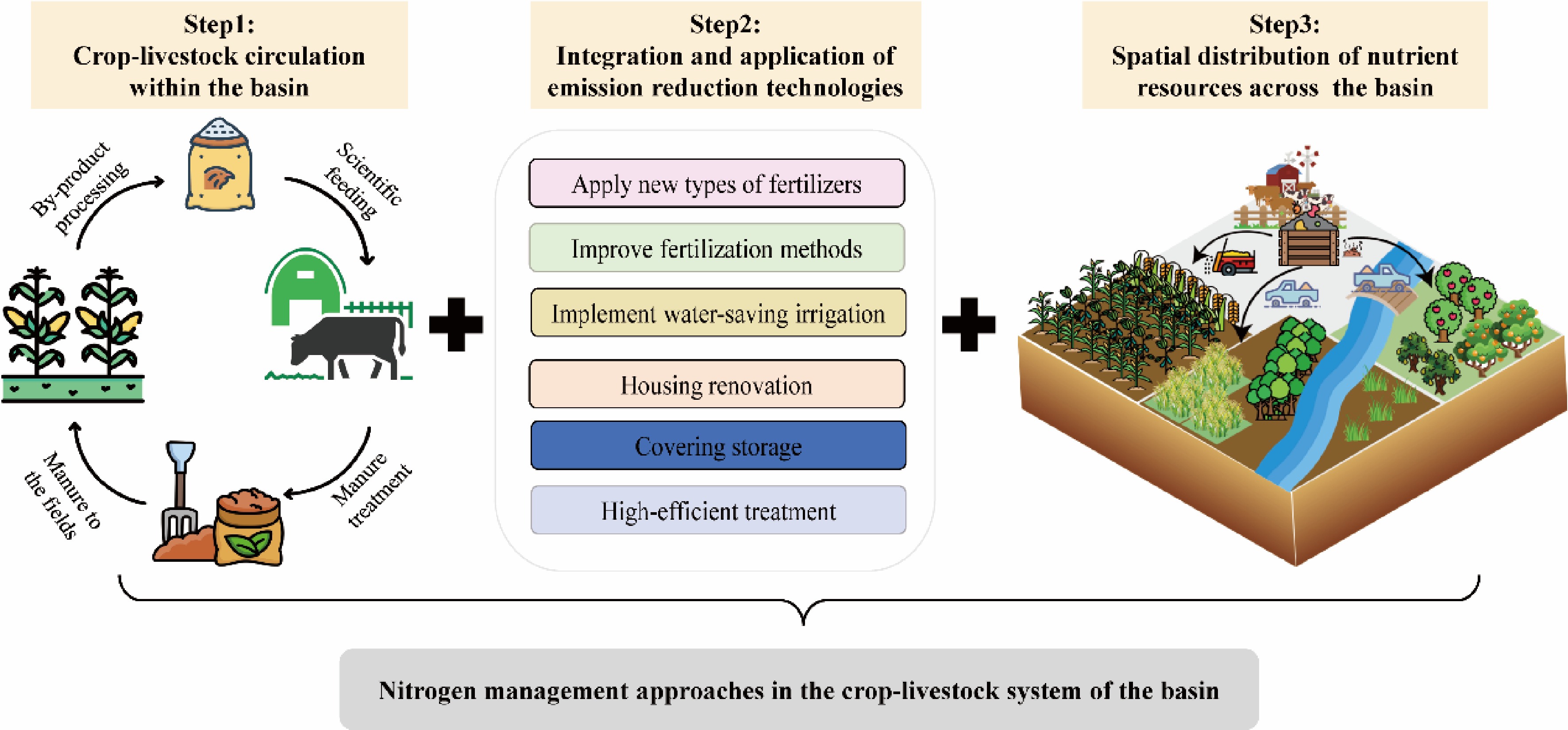

Regarding the nitrogen loss pathways in the crop and livestock industries, Studies have developed a complete chain of emission reduction technologies. They are gradually moving towards regional adaptation and multi-technology integration, providing technical support for nitrogen control in basins.

Nitrogen loss in crop systems mainly occurs through three ways: ammonia volatilization, nitrification-denitrification, and runoff/leaching. Globally, 40%–70% of the nitrogen applied to farmland is lost via these paths annually[58]. In the 1960s, compound fertilizers and coated slow-release fertilizers were developed, marking an improvement in fertilizer use efficiency[59]. The meta-analysis indicates that the use of controlled-release nitrogen fertilizer in combination with agricultural practices can maximize crop productivity and environmental benefits[60]. Additionally, sulfur-coated urea can reduce nitrogen leaching by 63.2%, and nitrification inhibitors can cut emissions by 13.8%–32.6%[61]. In 2005, China promoted soil-test-based formulated fertilization and released the Technical Specifications for Soil-Test-Based Formulated Fertilization. In 2009, the International Plant Nutrition Institute (IPNI) put forward the '4R' nutrient management concept—Right Source (correct fertilizer type), Right Rate (proper amount), Right Time (ideal timing), and Right Place (accurate application location). This gave a framework for scientific fertilization[62]. Applying urea deeply into the soil reduces ammonia volatilization by 61.7%, and saves 30% of urea[63]. Optimizing the best amount of nitrogen for wheat-corn planting systems can cut nitrogen fertilizer use by 30%–60%, and avoid the doubling of nitrogen loss caused by excessive nitrogen[64]. By analyzing 1,521 global field experiments, Gu et al.[65] selected 11 key measures. These measures are capable of reducing nitrogen loss to the atmosphere or water by 30%–70%, while simultaneously increasing crop yields by 10%–30%, and nitrogen use efficiency by 10%–80%. Furthermore, adjusting irrigation volume and frequency can alter the migration of nitrogen in soil, thereby reducing nitrogen loss[66].

While developing technologies for emission reduction, efforts have also been made to establish a technology integration application model. For the livestock sector, nitrogen emission reduction technologies cover the entire chain: feed production − manure management − manure storage − manure treatment − manure application to fields. Reducing the nitrogen content in livestock feed by 8% can cut ammonia-nitrogen emissions by 40%[67]. Adding urease inhibitors to manure reduces ammonia volatilization from the manure by 55.5%[68]. Treating the surface of manure with different types of acids can reduce ammonia emissions by 60%–80%. A technology using breathable membrane tubes with acid solutions in chicken coops can recover 96% of ammonia[69]. Solid-liquid separation technology for pig manure reduces ammonia emissions by 90%, and covering the manure with specific materials can further lower ammonia volatilization[70]. Composting manure in sealed reactors cuts ammonia volatilization by 61%; when combined with ammonia washing and recovery technology, the total emission reduction rate reaches 82%[71]. Injecting liquid pig manure directly into fields reduces ammonia volatilization by 29% during the base fertilizer period for wheat and corn[69]. Integrating spatially focused measures with generic emission reductions are expected to be most effective in reducing ammonia concentrations in natural areas[72].

The integrated application of emission reduction technologies has brought significant improvements to the environment. However, there are various types of existing emission reduction technologies, and when selecting for application, more attention should be paid to the characteristics of regional industries and regional compatibility. At the same time, economic costs should also be taken into account to propose the optimal management approach within the region.

Spatial analysis of crop and livestock production in basins and management of cross-regional distribution

-

Under the current context of intensive crop and livestock development, single emission reduction technologies can no longer meet regional emission reduction requirements. Effective approaches now rely on the integration of crop and livestock systems, the adoption of combined technical models, and the spatial coordination of resources. However, the geographical conditions, crop and livestock structures, and environmental pressures within basins vary significantly. The 'one-size-fits-all' model is difficult to apply. It is necessary to optimize the distribution based on spatial heterogeneity to achieve precise control. Basin nitrogen management is gradually moving towards a refined approach of 'river basin-county-plot'. Using GIS spatial analysis, assess the spatial matching degree between crop nutrient demand and livestock manure nitrogen supply in different areas. This will help identify hotspot areas where crop cultivation and livestock production are unbalanced. For example, a study on the Huang-Huai-Hai River basin identified 202 counties with high total nitrogen loss (mostly in Henan and Hebei provinces)[73]. China has divided the country into nitrate-vulnerable areas and put forward different control measures for each area[74]. However, there are also studies indicating that the control measures within the region may not be able to fully meet the environmental standards[48]. Further exploration of alternative solutions is still necessary. If the excessive nutrients within the region cannot be absorbed, then optimization of the distribution across regions will be required. In large-scale agricultural regions, studies use geospatial simulations to predict farmland sizes and livestock distribution. They also assess ammonia emissions, air quality, and economic impacts[75]. Based on environmental thresholds, some studies have also proposed nitrogen reduction and control pathways for county-level crop and livestock production within basins, targeting different environmental zones[76]. Regional spatial analysis and cross-regional management have divided the river basin into three functional zones: core ecological protection areas, agricultural priority control areas, and comprehensive living management areas. For each zone, management priorities and the rational spatial distribution of nutrients have been clearly defined.

Based on the above analysis, a future management path for crop and livestock nitrogen in the basin has been formed, encompassing three core components: 'regional crop-livestock recycling, integrated application of emission reduction technologies, cross-regional spatial distribution' (Fig. 2).

-

The current nitrogen-related environmental status in crop-livestock systems within the basin is influenced not only by technical and managerial constraints but also by socioeconomic factors such as farmer behavior and economic investment. As the primary decision-makers and implementers of agricultural practices, farmers play a critical role in determining the efficiency and environmental outcomes of nitrogen management. One study indicates that farmers' cognitive biases and personal attitudes can reduce the adoption rate of sustainable agricultural practices by 20%–70%, whereas positive social influences can increase adoption by up to 40%[77]. From a technical and managerial perspective, studies suggest that the implementation of a fertilizer tax in the Pearl River Basin leads farmers to reduce fertilizer application while simultaneously expanding the scale of livestock breeding to maintain income levels[78]. This behavioral shift may alter the structure of pollution sources. At the policy response level, the effectiveness and implementation of regulations, subsidies, and ecological compensation mechanisms are strongly influenced by the differential responses of farmers. Understanding and guiding farmer behavior serves as a critical bridge linking technical nitrogen management strategies with broader environmental objectives in river basins. Promoting the adoption of sustainable agricultural practices requires moving beyond the current heavy reliance on economic incentives. To effectively promote sustainable agricultural practices, greater emphasis must be placed on diversified incentive mechanisms—particularly those enhancing transparency, communication, and training—to address behavioral and psychological barriers among farmers[79]. Future policy optimization should sustain focus on key dimensions, including the scientific basis of social behaviors, regional economic disparities, and the coordination of cross-sectoral responsibilities. Furthermore, this process necessitates the collaborative engagement of policymakers, farmers, researchers, and the general public.

The long-term implementation of policies not only exerts constraints on production management but also undergoes systematic adaptive adjustments in practical production contexts. For instance, the pilot implementation of environmental policies may result in the transfer of certain pollution[80]. China's long-term water pollution control policies are under continuous refinement, characterized by a profound transition from fragmented regulation to systematic governance. Early policies were predominantly centered on single indicators. In contrast, the current national development blueprint has shifted toward holistic dimensions such as water ecosystem management, marking a multi-faceted transformation in policy orientation. From uniform standards to precise management by zones, management is becoming more refined and scientific, at the same time, strengthening river basin collaboration and shared responsibility. To address cross-administrative-region river pollution issues, policies are actively promoting the river and lake chief system collaboration mechanism to promote coordinated governance upstream and downstream, and left and right banks. In addition to traditional command-control policies, economic means such as environmental taxes are also being explored for application, guiding farmers to adjust their production behaviors through cost impacts. At the same time, through industrial transformation and upgrading, pollution is reduced at the source. Long-term policies not only constrain behavior but also reshape the entire river basin agricultural nitrogen management system and guide it towards the ultimate goal of sustainable development.

-

In response to the growing demand for green agricultural development and to address the current research gap in nitrogen management within river basin. This study aims to tackle issues such as the lack of regional thresholds, poor regional adaptability of technical models, and incomplete nutrient management approaches. We propose a holistic framework that integrates grain production, economic benefits, and ecological protection into a unified planning system. The objective is to achieve synergistic outcomes across agricultural productivity, ecological sustainability, and economic viability, thereby establishing a comprehensive and integrated nitrogen management system for river basin agriculture (Fig. 3).

First, a dynamic threshold updating mechanism should be established to tackle the lag in static management. By leveraging long-term monitoring network of nitrogen flow across multiple environmental media (such as soil, water, and atmosphere) and integrating multiple models, an interconnected updating system can be formed. This system would allow for periodic calibration of nitrogen input thresholds for sub-basins based on monitoring data, ensuring that thresholds dynamically reflect environmental changes and structural shifts in crop-livestock systems, thereby avoiding the disconnect often caused by static management approaches. Second, multi-factor coordinated management should be enhanced to address the deficiency in factor coupling. Beyond focusing on nitrogen-related indicators, it is essential to integrate nitrogen management with the regulation of phosphorus and carbon cycles. Incorporate indicators for phosphorus loss control and carbon sink enhancement into goal-setting to avoid other ecological problems caused by single nitrogen management. Third, differentiated zoning management should be implemented to improve regional adaptability. By employing GIS-based spatial analysis and dividing different regions in combination with environmental goals, a new approach has been developed that integrates 'regional crop-livestock recycling, combined application of emission-reduction technologies, and cross-regional spatial planning'. Fourth, a multi-system coupled management framework should be established to enhance systematic comprehensiveness. Centered on the core workflow of 'target values clarification − technology integration − spatial distribution − institutional support', a closed-loop management system is constructed. Economic goals are also incorporated: priority is given to promoting 'low-cost, high-emission-reduction' models in technology selection, and collaboration with government departments is pursued to implement corresponding subsidy policies. This ensures that multi-factor coordinated management achieves not only ecological benefits but also has economic viability and social feasibility.

Integrated nitrogen management in basins can precisely identify the key source areas and pathways of nitrogen loss and effectively alleviate environmental problems through scientific regulation. Simultaneously, it contributes to the optimization of agricultural production and facilitates a balance between crop productivity and ecological conservation. It maintains basin-scale ecological functions and establishes a solid foundation for the green development of crops and livestock within the basin.

-

Nitrogen management is a key approach to promoting basin ecological protection. Globally, substantial findings have been accumulated across key areas—including optimized agricultural management practices, the establishment of environmental nitrogen thresholds, and the development of nitrogen emission reduction technologies—laying a solid foundation for addressing basin nitrogen-related challenges. Nevertheless, several critical gaps remain in current research and practice. First, the integration of multiple systems (e.g., crop-livestock systems, environmental monitoring systems, and policy regulation systems) remains insufficient, limiting the holistic coordination of nitrogen management. Second, most existing studies rely on static nitrogen thresholds, while dynamic thresholds that adapt to changes in climate, land use, or agricultural practices are still lacking, hindering timely and flexible nitrogen control. Third, technical models and management measures often lack regional adaptability, failing to account for the heterogeneity of geographical conditions, crop-livestock structures, and environmental pressures across different basins. To address these limitations, future efforts should focus on three major directions. First, system-level integration should be enhanced through coordinated efforts in setting nitrogen thresholds, deploying emission reduction technologies, and optimizing agricultural structures. This integrated approach would support a transition from standardized to adaptive nitrogen management—one capable of dynamically responding to real-time variations in water purification capacity, crop nutrient demands, and climatic conditions—thereby enabling more intelligent, responsive, and efficient regulatory mechanisms. Second, a more comprehensive perspective must be adopted in both research and practice to achieve a balanced integration of resource utilization, environmental protection, and sustainable socioeconomic development. It is essential that nitrogen management strategies safeguard food production or rural livelihoods. Improved coordination of nitrogen-related objectives and interventions is required across upstream and downstream regions, urban and rural areas, and between developed and less-developed regions. Mechanisms such as ecological compensation and shared responsibility can help mitigate policy inconsistencies and prevent the transboundary transfer of pollution, thus maximizing environmental and socioeconomic benefits at the basin scale. Finally, an intelligent nitrogen management framework should be established, integrating dynamic threshold models, targeted technological strategies, and spatially differentiated policies. Such a framework would ensure strict compliance with environmental boundaries while preserving the long-term sustainability of agricultural production systems and broader socioeconomic functions.

The authors acknowledge support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32002138).

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Ma W, Ma L, Fan X; theoretical framework: Bai Z; data collection and manuscript writing: Zhang X; providing critical feedback and shaping the research and manuscript: all authors. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang X, Fan X, Ma W, Ma L, Bai Z. 2025. Nitrogen optimization management for green transition of crop and livestock systems in river basins: a systematic review. Circular Agricultural Systems 5: e014 doi: 10.48130/cas-0025-0015

Nitrogen optimization management for green transition of crop and livestock systems in river basins: a systematic review

- Received: 26 September 2025

- Revised: 18 November 2025

- Accepted: 25 November 2025

- Published online: 10 December 2025

Abstract: Nitrogen plays a crucial role in the cycling balance at the basin scale, which is essential for sustainable agricultural development and ecological security. Currently, the world is facing a sharp contradiction between 'ensuring nitrogen supply' and 'preventing nitrogen pollution'. As the critical carrier for the cross-media (water-soil-atmosphere-plant) transfer of nitrogen, basins have become a key breakthrough point in addressing this contradiction. This review systematically synthesizes the latest progress in the field of basin nitrogen management. It focuses on aspects such as identifying nitrogen flow characteristics and driving factors, setting environmental goals, and exploring nitrogen reduction pathways. By integrating domestic and international research findings, as well as practical case studies, this review further identifies three key limitations currently present in nitrogen emission reduction and management: (1) an overemphasis on single-factor effects while insufficient consideration of multi-factor constraints; (2) a reliance on static environmental thresholds rather than dynamic adaptation to changing basin conditions; and (3) a focus on individual technology development with inadequate attention to regional integration. Finally, a coordinated, precise, and differentiated basin nitrogen management framework is proposed to provide theoretical references and practical guidance for promoting agricultural green transformation, and enhancing basin ecological protection.