-

Solar radiation is the main energy source for the surface ecosystem, and it is the original driving force for the ecosystem to maintain its normal operation and development[1]. The energy captured by plant photosynthesis is recognized as the main driver for the formation of organic matter utilized by soil microorganisms, particularly when the vadose zone is unsaturated[2]. In contrast to the conventional biophotoelectrochemistry in phytoplankton through photosynthesis, recent studies suggested that non-phototrophic microorganisms in soils and sediments are able to harvest extracellular electrons, including the photoexcited electrons from photosensitizers, such as minerals and photosynthetic bacteria[3,4]. This discovery suggested that solar energy may have a more extensive impact on microbial metabolism and geochemical processes, even in saturated soils and sediments.

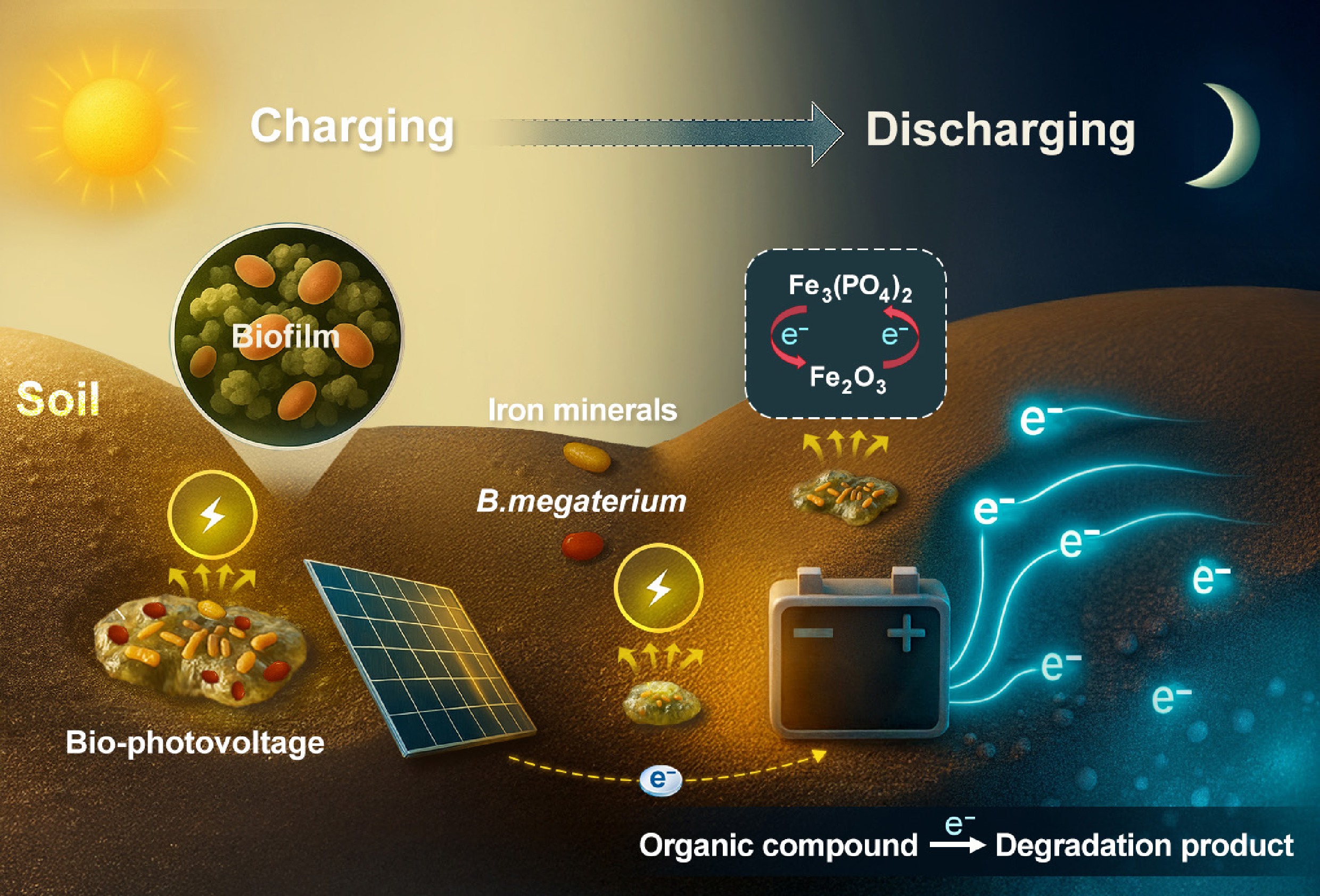

This emerging field of biophotoelectrochemistry leverages live microbial biofilms to harness sunlight for electricity generation[5], potentially channeling photoexcited electrons into the opaque zones of soil. The 'mineral films' formed through the interaction of semiconductor minerals such as Fe, Cu, Mn, or Ti minerals and microorganisms can absorb sunlight and promote the growth of chemosynthetic autotrophic microorganisms, which have been discovered in three distinct habitats in China, including the rock paintings of the northwest Gobi Desert, the karst landforms in the southwest, and the red soil in the south[3]. These discoveries suggest mineral-microbial biofilms may extend electron transport chains beyond conventional limits, enabling novel energy cascades in dark environments. This generally overlooked process may have played critical roles in biogeochemical functions such as contaminant mitigation in soils and sediments via photoelectron-driven redox reactions. Notably, transient photocurrents in abiotic systems decay within milliseconds, preventing energy utilization beyond the photic zone. While recent studies confirm non-phototrophic microbes harvest photoelectrons from mineral photosensitizers[6−8], the mechanistic linkage between photoelectron transfer and microbial energy utilization remains unresolved. Specifically, how do biofilms convert ephemeral photoelectrons into persistent metabolic energy for dark-phase biogeochemical processes?

Bacillus is a group of bacteria with high abundance in soil. Bacillus megaterium (B. megaterium) has been demonstrated to be electrochemically active. This study employed hematite (Fe2O3) and goethite (FeOOH) as the model minerals and B. megaterium as the model microbe to explore the transfer and utilization of photoelectrons following the interaction between bacteria and iron minerals. Our primary focus is on the accumulation, storage, and release of electrons during light-dark cycles following the interaction between B. megaterium and iron minerals, as well as the subsequent effects on organic compound degradation in the dark. This line of study not only sheds light on biogeochemical processes but also explores sustainable techniques to mediate pollution control.

-

The B. megaterium strain was isolated from soil (Kunming, China)[9]. The 16S rDNA sequences were analyzed using the National Center for Biotechnology Information database, GenBank. The culture methods for B. megaterium cells are detailed in previous literature[9]. B. megaterium cells were obtained by centrifugation at 6,577 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, followed by freeze-drying. Various proportions of B. megaterium cells and Fe2O3 were dispersed in sterile distilled water for 1 d at 30 °C with shaking at 150 rpm in a constant temperature shaker, centrifuged at 8,000 × g, and washed 10 times with distilled water. The obtained Fe2O3−B. megaterium composites were freeze-dried separately for further use.

Photoelectrochemical testing

-

Three different types of electrodes, based on a saturated calomel electrode, indium-tin oxide, or a platinum wire, were used. The photoelectrodes were prepared by the drop-coating method[10]. Six mg of the composites were dispersed with 600 μL 30% ethanol, 100 μL 3.75% acetic acid, and 50 μL Nafion, and the mixture was sonicated for 1 h[11]. Acetic acid serves as a multifunctional additive that stabilizes dispersion through protonation-induced electrostatic repulsion, enhances charge transfer via proton-coupled redox mediation, and controls film morphology by modulating solvent evaporation dynamics[12]. The electrodes were then coated with 200 μL of the mixture to form a thin film. Subsequently, the sample solution was loaded onto the conductive surface of indium-tin oxide conductive glass with a physical area of 1 cm2 and dried at room temperature for 12 h to form a thin film. Open circuit potential-time (OCPT), Electrochemical impedence spectroscopy (EIS), Amperometric i-t curve (i-t curve), and Tafel analysis were performed.

Analysis of physicochemical properties and electronic structure of composites

-

The morphologies of the composites were analyzed using field emission scanning electron microscopy (Hitachi Regulus 8,100, Zeiss Sigma 300). The composition of surface elements was analyzed using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (X-Max N, Oxford Instruments). The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were recorded in the range of 5°–80° at 40 kV and 30 mA to determine any changes in the crystal structure of the minerals. The chemical composition of the samples was characterized by a Fourier transform infrared spectrophotometer (Nicolet iS50, Thermo). Additionally, the Raman spectra were obtained using a Raman microscope (Renishaw inVia, USA) equipped with a 532 nm laser.

B. megaterium activity

-

The investigated particles were dispersed into sterile distilled water and cultured on Luria-Bertani agar plates[9]. The dead and live conditions of bacteria in the investigated systems were characterized by a confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss LSM880) using the LIVE/DEAD BacLight viability stain kit from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA). B. megaterium biofilms were imaged on an Olympus Fluoview FV3000 confocal microscope (Olympus, Japan).

Light-induced degradation of antibiotics

-

This study investigated the transformation of chloramphenicol (CPL) and tetracycline hydrochloride (TCH) by Fe2O3/B. megaterium or FeOOH/B. megaterium. Degradation of these antibiotics in Fe2O3/B. megaterium or FeOOH/B. megaterium was investigated under dark conditions after exposure to sunlight for 0, 20, and 60 min.

Antibiotics in solid and liquid phase after reaction were evaluated by HPLC (Agilent 1,260 Infinity II HPLC equipped with a C18 column) at 30 °C. CPL was measured by a fluorescence detector at an excitation wavelength of 278 nm; the mobile phase was methanol/water (60:40, v/v) at a flow rate of 1 mL·min−1[13]. For TCH, the detection conditions were as follows: the mobile phase comprised acetonitrile and ultrapure water in a ratio of 35:65, with a detection wavelength of 280 nm, a flow rate of 1.0 mL·min−1, an injection volume of 10 μL, and a column temperature also maintained at 30 °C[14]. The retention time for TCH was approximately 3.4 min.

Statistics and reproducibility

-

All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and statistical analyses and graphs were performed using GraphPad Prism 10.0.2. Significant differences were determined by Duncan's multiple range test at p < 0.05. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess the data (means ± SD, n = 3) using IBM SPSS statistics 20.0.

-

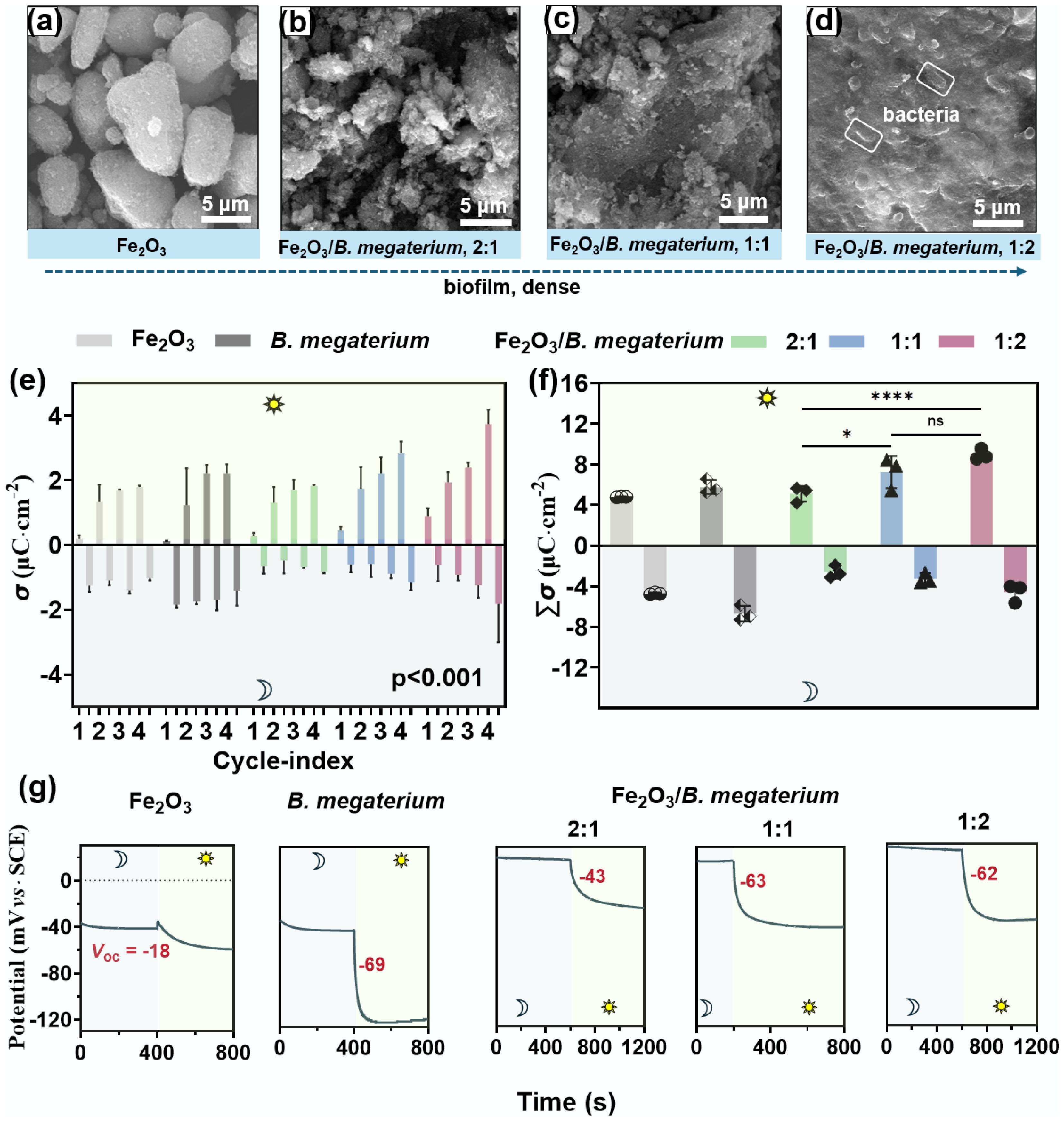

The accumulation and release of electrons during light-dark alternation was investigated in co-cultures of B. megaterium and Fe2O3 or FeOOH. The morphology and structure of iron mineral surfaces were altered by B. megaterium. For example, a multiphase structure characterized primarily by flake-like and granular morphologies was observed after co-culturing with Fe2O3 (Fig. 1a−d), and the bacteria remained active (Supplementary Fig. S1). Interestingly, this co-cultured system exhibited distinctive continuous charge-discharge characteristics under light-dark alterations. As the number of light-dark cycles increased, the photocurrent density gradually rose, while the dark current density consistently decreased (Supplementary Fig. S2). A denser biofilm (i.e., a higher ratio of bacterial content) corresponded to a greater photocurrent density (Supplementary Fig. S2). The difference between charge accumulations (σ) induced in light and released in dark showed fewer variations in pure Fe2O3 or B. megaterium systems compared to the co-culturing systems (Fig. 1e). After three cycles, their total accumulated charge (∑σ) approximately equaled the overall released charge (Fig. 1f). However, the σ values of the co-culturing systems under illuminated conditions consistently exceeded those released in dark, and this disparity gradually increased with the number of cycles. Consequently, the ∑σ values of the co-culturing system in light were significantly higher than those released in the dark (p < 0.001). Notably, more microbial biomass corresponded to a higher ∑σ, indicating that a dense biofilm may be more conducive to capturing and storing photo-generated charges. It should be noted that some electrons that were not fully released during the dark period became 'residual charge' accumulated in the system. The net accumulated charge increased from 2.87 to 4.08 μC·cm−2 (p < 0.001). Comparative analysis of adjacent mixing ratios (2:1 vs 1:1; 1:1 vs 1:2) revealed no statistically significant differences in ∑σ values (p > 0.05). However, with extended cultivation, the system developed well-defined lamellar architectures under the 1:1 ratio condition (Supplementary Fig. S3). These structurally optimized biofilms showed a 3.2-fold increase in net charge accumulation, from 3.98 to 12.60 μC·cm−2 (p < 0.0001; Supplementary Fig. S3). These findings highlighted the critical role of bacteria in regulating the optoelectronic storage performance of the co-cultured systems.

Figure 1.

The biofilms formed in Fe2O3–B. megaterium systems showed photovoltaic effects. (a)–(d) The surface morphologies of the biofilm on Fe2O3 displaying a lamellar structure. (e) This Fe2O3-B. megaterium system showed electro-charging and discharging processes under alternating light and dark conditions (p < 0.001). (f) The summarized ∑σ values of the co-culturing system in light were significantly higher than those released in dark. (g) This biofilm exhibited a photovoltaic effect in dark-light cycles. The interaction between FeOOH and B. megaterium followed a similar pattern as presented in Supplementary Figs S5−S7.

The Fe2O3/B. megaterium biofilm demonstrated a photovoltaic effect according to OCPT results, which increased with the proportion of bacteria (Fig. 1g). However, the photoelectric conversion mechanism of this biofilm differs from that of the traditional photoelectric effect. When shifting from dark to light exposure, all the investigated systems demonstrated photovoltaic effects. The photovoltage (Voc) of B. megaterium reached −69 mV, surpassing the −18 mV observed for Fe2O3. The Voc values in the co-culturing systems increased from −43 to −62 mV with the increased bacterial concentration (Fig. 1g). The EOCP of co-culturing systems shifted to more negative values with increased bacterial concentration under light exposure, but to more positive values in the dark. This phenomenon probably indicated that co-culturing was a photo-regenerative electronic capacitor: The compact biofilm enhances the electron storage and conversion capacity, achieving efficient photonic energy conversion and slow release. Notably, the EOCP of the biofilm always recovered after the light was turned off, suggesting that this co-culturing system possesses a photoelectric memory function (Supplementary Fig. S4).

In general, these results indicate that the biofilm formed through the interaction of Fe2O3 and B. megaterium exhibited a capability of continuous photo-charging. This charging process was enhanced with light-dark cycles and the proportion of bacteria in the co-culture system. The interaction between FeOOH and B. megaterium followed a similar pattern (Supplementary Figs S5−S7). These findings may provide new insights into carbon and nitrogen cycles in soil, as well as strategies for pollution control. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis: photoelectrons stored during light radiation at the iron-microbe biofilm can facilitate the transformation of pollutants in soil and even groundwater.

Organic degradation in the dark after photo-charging of the composites

-

Iron mineral-bacterial biofilms exhibit photon memory, distinguishing them from single-component systems. The Fe2O3/B. megaterium composite system demonstrated minimal degradation of TCH and CPL under continuous darkness (light exposure of 0 min). In the following experiment, the Fe2O3/B. megaterium composite was subjected to continuous light for 20 min. Then the light was turned off, and pollutants were introduced. The degradation efficiency of TCH reached 12% within the first 20 min of the reaction, while CPL degradation was 15% at 20 min (Fig. 2a). When the light illumination was extended to 60 min, the following degradation efficiencies in dark reached up to 20% (TCH), and 22% (CPL), representing significant enhancements of 66.7% and 46.7%, respectively (Fig. 2a). However, the separated systems of Fe2O3 or B. megaterium showed negligible degradation after both 20 min and 60 min of light exposure. These results indicated that the Fe2O3/B. megaterium co-culturing systems can degrade antibiotics in the dark after being charged in light. Again, the FeOOH-based system demonstrated a similar trend (Fig. 2b). These photonic memory properties of iron mineral/bacterial composites could degrade organic pollutants, which may play a significant role in their environmental behavior.

Figure 2.

Prolonging the illumination duration of the iron mineral/B. megaterium co-culturing systems enhances both the rate and extent of antibiotics degradation. When TCH or CPL was introduced to the systems after being illuminated for 0, 20, and 60 min, (a) the Fe2O3/B. megaterium, and (b) FeOOH/B. megaterium co-culturing systems promoted pollutant degradation of TCH or CPL in a dark environment. Notably, the degradation of antibiotics by the biofilm formed through biofilm was independent of free radicals (Supplementary Text 1).

Conversion of iron minerals in the co-culturing systems

-

To elucidate the degradation mechanism of organic pollutants in bacteria-iron mineral systems, the photoelectrical response, interfacial architecture, and compositional evolution of the biofilm were investigated. Elemental mapping revealed a homogeneous distribution of Fe, O, C, N, P, and S across the biofilm surface, with C, N, P, and S originating from bacterial incorporation (Supplementary Figs S8 and S9). The enhanced electrochemical activity of the iron mineral/B. megaterium could be attributed to the incorporation of these biological elements. High-resolution XPS spectra of the Fe2p orbitals displayed a negative shift in the binding energies of Fe(III) at 710.8 and 723.5 eV following interaction with B. megaterium[15] (Fig. 3a). Notably, two new peaks emerged at 708.9 eV (2p3/2) and 721.7 eV (2p1/2), representing Fe(II) species[16] (Fig. 3a). The Fe(II) content increased from 17.4% to 28.4% with a rise in the initial proportions of B. megaterium (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. S8), confirming microbial-driven reduction of Fe2O3. The peaks for PO42– (131.86 eV), Fe–N (398 eV)[17], pyridinic-N/amino-N (399 eV), and C–N (273.5 eV) were observed in the biofilm[16] (Supplementary Fig. S9). These results demonstrate that B. megaterium was able to reduce Fe2O3 while introducing C, N, P, O, and S in the system, forming Fe3(PO4)2 and modulating its electronic and chemical properties to favor antibiotic degradation.

Figure 3.

B. megaterium reduces the Fe(III) in Fe2O3 to Fe3(PO4)2, along with the altered elemental composition and electronic structure of the mineral. The content of Fe(II) increased with the increase of (a) bacteria proportion, (b) crystal type, and (c) Raman intensity also changed after B. megaterium and Fe2O3 co-culturing.

XRD analysis also revealed weakened diffraction peaks and the emergence of new Fe3(PO4)2 peaks at 20o, 38o, and 54o in the co-culturing systems[18,19] (Fig. 3b), confirming Fe(III) reduction, which was consistent with XPS results. Fe(II) content increased up to 41.3% over time (Supplementary Fig. S10). The mixed Fe(II)/Fe(III) in Fe2O3/B. megaterium biofilm enabled photoelectron storage, as evidenced by their stronger Raman peaks over Fe2O3-only systems (Fig. 3c). B. megaterium also reduced Fe(III) in FeOOH to Fe(II) as presented in Supplementary Figs S11−S13. In general, metabolic products such as pyridinic-N, amino-N, and PO43− could reduce charge-transfer resistance. The co-culturing systems synergistically enhanced charge storage, carrier separation, and interfacial electron transfer, which were critical for redox-driven degradation.

Electrochemical characterization of the co-culturing systems

-

The electron storage, transfer, and release are determined by the resistance R and capacitance, which can be reliably analyzed using EIS under an open circuit voltage[20]. The phase angle Bode plot was employed to assess the number of interfacial electrochemical processes involved in EIS. For individual systems of Fe2O3 and B. megaterium, a peak in the middle-low frequency (MF-LF) region was observed (Supplementary Figs S14 and S15), indicating the presence of one-time constant τ. In comparison, the Bode plot of Fe2O3/B. megaterium composites showed one peak in the MF-HF region and two troughs, corresponding to two time constants. The maximum phase angle of Fe2O3/B. megaterium systems (52.6°–55.4°) was lower than those of Fe2O3 or B. megaterium (Supplementary Fig. S14), suggesting the enhanced charge transfer in the composites. The slopes of Bode modulus plots for the investigated composites are close to −1 in MF-HF region (Supplementary Fig. S14), indicating a typical capacitive behavior[21]. The τ values of Fe2O3/B. megaterium composites were 2–3 magnitudes lower than that of the individual components of Fe2O3 or B. megaterium (Fig. 4a), indicating that the interaction between bacteria and iron minerals significantly enhanced the migration rate of photogenerated charge carriers (electron-hole pairs). B. megaterium forms coordination bonds with the Fe2O3 surface through functional groups such as carboxyl and amino groups, creating efficient electron transfer pathways[22,23], which suppresses carrier recombination and accelerates their migration to the electrode interface.

Figure 4.

The Fe2O3/B. megaterium biofilm is conducive to electron transfer. (a) Time constant τ values of the composites were significantly lower than that of Fe2O3 or B. megaterium under light. (b) The interface double-layer capacitance Q1 of the composite system increased by 5 to 9 times compared to the individual system, and a new pseudo-capacitance Q2 was formed. (c) The Rct of Fe2O3/B. megaterium composites decreased by approximately three orders of magnitude compared to that of Fe2O3 or B. megaterium alone. (d) The exchange current density j of biofilm surpasses that of Fe2O3. The results of FeOOH and B. megaterium are presented in Supplementary Table S2.

The electrochemical processes were conceptualized using the equivalent electric circuit model (Supplementary Table S1). The interfacial capacitance (Q1) increased by 5–9 times and was accompanied by the formation of a series capacitance (Q2) (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table S1). The electron transfer resistance (Rct) of Fe2O3/B. megaterium composites were reduced by about three orders of magnitude compared to Fe2O3 or B. megaterium alone (Fig. 4c). These results suggested that the bacteria-mineral interface forms a pseudocapacitive structure, promoting charge separation and storage through interfacial polarization effects. The Tafel curve further revealed that the exchange current density (j) of the biofilm reaches up to 5.7 × 103 A·cm–2, which was six orders of magnitude higher than that of a single component, indicating that the heterojunction significantly reduced the charge transfer energy barrier and optimized the kinetics of redox reactions (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. S16).

These comprehensive descriptions indicate that Fe2O3 and B. megaterium interact to form a large 'biological capacitor', which can buffer transient photonic current fluctuations, enhance photoelectric conversion efficiency, and enable pollutant degradation in the dark after light charging. The photocurrent response of the Fe2O3/B. megaterium biofilm exhibits a unique stepwise growth characteristic, achieving the dark-state degradation of TCH and PCL after light charging. This phenomenon may be attributed to: (1) the synergistic effect of the Fe(II)/Fe(III) redox pair on the surface of Fe2O3 and microbial electron shuttles forming a distributed charge storage network; (2) the biologically mediated transmembrane transfer of the stored electrons to sustain pollutant degradation; (3) the smooth photocurrent buffered by capacitive effects to ensure operational stability.

The sustained pollutant degradation of the light-activated composites in the dark suggests effective trapping and storage of photogenerated electrons. Bacterial metabolites from B. megaterium, such as extracellular polysaccharides and electron shuttles, synergistically formed a 'biological capacitor' with hydroxylated iron mineral surfaces, facilitating the transmission of stored electrons to pollutant molecules.

-

The iron-metabolizing bacterium B. megaterium is widely distributed in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, particularly in plant rhizospheres (colonizing at 105–107 CFU·g–1 on crops like rice and alfalfa) and tidal sediments, where it frequently interfaces with iron oxides. Through controlled experiments mimicking natural iron-rich environments, we observed bio-photovoltage memory in Fe2O3/B. megaterium systems. The composite at a 1:2 mass ratio reached ∑σ of 8.06 μC·cm−2, with the net charge increasing from 2.87 to 4.08 μC cm−2. A higher microbial density corresponds to an increased ∑σ and Fe(II) content, suggesting that a dense biofilm enhances Fe(II)-mediated processes, which facilitate the capture and storage of photo-generated charges. We propose that after the light is turned off, the enriched photogenerated electrons are released in the dark, generating a photovoltaic effect that drives pollutant degradation. This biofilm demonstrates sustained electron storage and release capability without continuous illumination, as evidenced by continued degradation of TCH and CPL for 1 h in the dark post-illumination. Notably, extended charging time enhances both the rate and extent of TCH and CPL degradation under dark conditions. These results provide new insights into the treatment of soil, sediment, and groundwater pollutants, and contribute to our understanding of element cycling and pollutant degradation in soil and sediment.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/ebp-0025-0006.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Li S, Chen Y, Wu M, Zhang P, Cui P, Duan W, Pan B, Xing B; material preparation, data collection and analysis: Li S, Chen Y; writing − draft manuscript preparation: Li S, Pan B, Chen Y; writing − review & editing: Pan B, Xing B, Wu M, Cui P, Zhang P, Duan W. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42130711, 42377250, and 42267003), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFC3709100), the Yunnan Major Scientific and Technological Projects (202202AG050019), the Yunnan Fundamental Research Projects (202301AU070078, 202201BE070001-040), and Guided by the Central Government for Local Science and Technology Development Funds (202407AB11026).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

A bio-photovoltage soil-microbe battery for antibiotic degradation in the dark is proposed.

Iron mineral−B. megaterium biofilms function as geochemical capacitors, enabling photon-to-electron conversion, charge storage, and controlled release for antibiotic degradation.

Fe2O3/B. megaterium achieves 8.06 μC·cm−2 charge storage via interfacial capacitance absent in single-component systems.

Sixty-min illumination enables 20%−22% antibiotic degradation in dark phase, outperforming 20-min treatment by 47%−67%.

Mineral−bacterial interface forms a redox relay system, channeling stored electrons for contaminant degradation.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Supplementary Text 1 Supplementary characterization of free radical trapping and quenching effects.

- Supplementary Table S1 Equivalent circuit fitting parameters of Fe2O3, B. megaterium, and Fe2O3/B. megaterium under sunlight and dark conditions.

- Supplementary Table S2 Equivalent circuit fitting parameters of FeOOH, B. megaterium, and FeOOH/B. megaterium under light and dark conditions.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 (a) Fluorescence image of B megaterium, (b-c) Fluorescence images of Fe2O3/B. megaterium composite before and after the chloramphenicol degradation reaction. b, before and c, after. (d) live bacterial counts in the biofilm under dark and light conditions.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 This Fe2O3-B. megaterium system showed electro-charging and discharging processes under alternating light and dark conditions.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Enhanced charge storage capacity (Σσ) in Fe2O3/B. megaterium biofilms during prolonged cultivation. (a-b) SEM images showing structural evolution of the mineral-bacteria biofilm after (a) 1 d and (b) 7 d of co-culture, demonstrating increased microbial density and mineral surface coverage. (c) Quantitative comparison of Σσ values reveals a significant, time-dependent increase in charge storage capacity (p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA).

- Supplementary Fig. S4 Fe2O3-B. megaterium system shows a photoelectric memory function. The open circuit potential can be restored to its initial potential when transitioning from light to darkness.

- Supplementary Fig. S5 SEM images and elemental mapping of FeOOH/B. megaterium.

- Supplementary Fig. S6 Photocurrent response of FeOOH, B. megaterium, and FeOOH/B. megaterium under light-dark cycles.

- Supplementary Fig. S7 Open circuit potential-time curves of FeOOH, B. megaterium, and FeOOH/B. megaterium under dark-to-light and light-to-dark conditions.

- Supplementary Fig. S8 B. megaterium was co-cultured with nano-hematite to form lamellar structure (similar to soil biological crust) and introduce biological elements. Bacillus megaterium (a), an iron mineral consisting of small spherical particles (b), and B. megaterium co-cultured with nanohematite formation lamellar structure (c).

- Supplementary Fig. S9 XPS spectra of Fe2O3/B. megaterium.

- Supplementary Fig. S10 XPS spectra of Fe2O3/B. megaterium (a) O 1s spectra (b) N 1s spectra (c) C 1s spectra (d) P 2p spectra. Compared with Fe2O3, there are new peaks of hydroxyloxygen (b), PO42− (c), amino acids -N, Fe-N (d), and C-N (e) in the hybrid film.

- Supplementary Fig. S11 Fe2O3/B. megaterium composites Fe 2p XPS spectra and magnified region plots at different incubation times 1 day (a), 4 days (b), 7 days (c); Relative contents of Fe(III) and Fe(II) in Fe2O3/B. megaterium at different incubation times (d) Figure.

- Supplementary Fig. S12 Fe 2p XPS spectra of FeOOH and FeOOH/B. megaterium.

- Supplementary Fig. S13 Raman spectra of FeOOH and FeOOH/B. megaterium.

- Supplementary Fig. S14 Microbial-mediated promotion of electron transfer at the hematite interface. Nyquist plot before and after co-culture of B. megaterium with Fe2O3.

- Supplementary Fig. S15 The Fe2O3/B. megaterium biofilm was conducive to electron transfer. Bode plot of before and after interaction between B. megaterium and Fe2O3 in the light (a) and dark (b).

- Supplementary Fig. S16 Tafel curves of Fe2O3, B. megaterium, and Fe2O3/B. megaterium under light and dark conditions.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li S, Chen Y, Wu M, Zhang P, Cui P, et al. 2025. A bio-photovoltage soil-microbe battery for antibiotic degradation in the dark. Environmental and Biogeochemical Processes 1: e004 doi: 10.48130/ebp-0025-0006

A bio-photovoltage soil-microbe battery for antibiotic degradation in the dark

- Received: 01 July 2025

- Revised: 06 August 2025

- Accepted: 22 August 2025

- Published online: 15 September 2025

Abstract: Solar energy sustains biogeochemical functions in soils. However, its utilization in saturated subsurface zones remains constrained by limited light penetration. In this study, it was revealed that iron mineral-Bacillus megaterium (B. megaterium) biofilms function as geochemical capacitors, wherein a redox pseudo-capacitance enables photon-to-electron conversion and dark-phase electron release for contaminant degradation. Fe2O3/B. megaterium composite at a 1:2 mass ratio reached a total accumulated charge (Σσ) of 8.06 μC·cm−2 during light-dark cycles, with net charge increasing from 2.87 to 4.08 μC·cm−2. Electrochemical analysis indicated that capacitance exclusively forms at mineral-microbial interfaces, but not in single-component systems. A higher microbial density corresponded to increased ∑σ and Fe(II) contents, demonstrating that the biofilm enhances the Fe(II)/Fe(III) cycle for the capture and storage of photo-generated charges. Notably, 60 min illumination resulted in a significant degradation in dark phase for tetracycline hydrochloride (20%) and chloramphenicol (22%), outperforming the systems subjected to 20 min illumination by 46.7%–66.7%. The interactions between iron minerals and bacteria formed a biofilm acting as a 'biocapacitor', wherein Fe(II)/Fe(III) cycle, coupled with bacteria, establishes a redox relay system, channeling stored electrons toward pollutants.

-

Key words:

- Bio-photovoltage /

- Bacillus megaterium /

- Fe2O3 /

- Antibiotic degradation /

- Iron minerals /

- FeOOH