-

Dissolved organic matter (DOM) consists of multiple constituents, including humic substances, polysaccharides, proteins, lignins, carbohydrates, and low molecular weight acids, and is ubiquitously distributed in water and soil systems[1,2]. More than trillions of tons of DOM in aquatic carbon reservoirs have crucial roles in carbon cycling, biological activities, and pollutant transport[3]. It has been well documented that hydrogeochemical cycling, watershed land cover, and microbial dynamics significantly change the concentrations, molecular compositions, and molecular size of DOM in the environment[2,4]. Global climate warming exerts a strong influence on these environmental processes by enhancing temperature, precipitation, irradiation, organic matter decomposition, and transport from terrestrial systems. Therefore, the dynamic variations of DOM source, concentration, quality, and turnover patterns are regulated by global climate change, such as temperature elevation, glacier and permafrost thawing, precipitation pattern shifts, forest fires, and extreme climate events. On the other hand, DOM concentration and composition changes may buffer or amplify climate change processes. Global climatic warming alters the molecular composition of DOM, potentiating carbon metabolism functions of Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria in deep soil horizons, thereby elevating the risk of deep soil carbon loss[5]. Concurrently, climate-induced eutrophication may escalate aquatic CO2 emissions by increasing the fluxes of readily mineralizable DOM, while accelerated humification could promote carbon sequestration[6]. This poses challenges for comprehending DOM-mediated environmental processes and biological responses to global warming. The objectives of this review are to: (1) provide a comprehensive understanding of biogeochemical transformations of DOM quality in the context of global climate change; (2) clarify the multiple roles of DOM as affected by climate change on pollution behaviors (including migration and transformation) and biological processes; and (3) reveal the feedback mechanisms of DOM transformation in response to climate change. Finally, the research challenges and opportunities for identifying DOM characteristics and roles in climate warming are discussed.

-

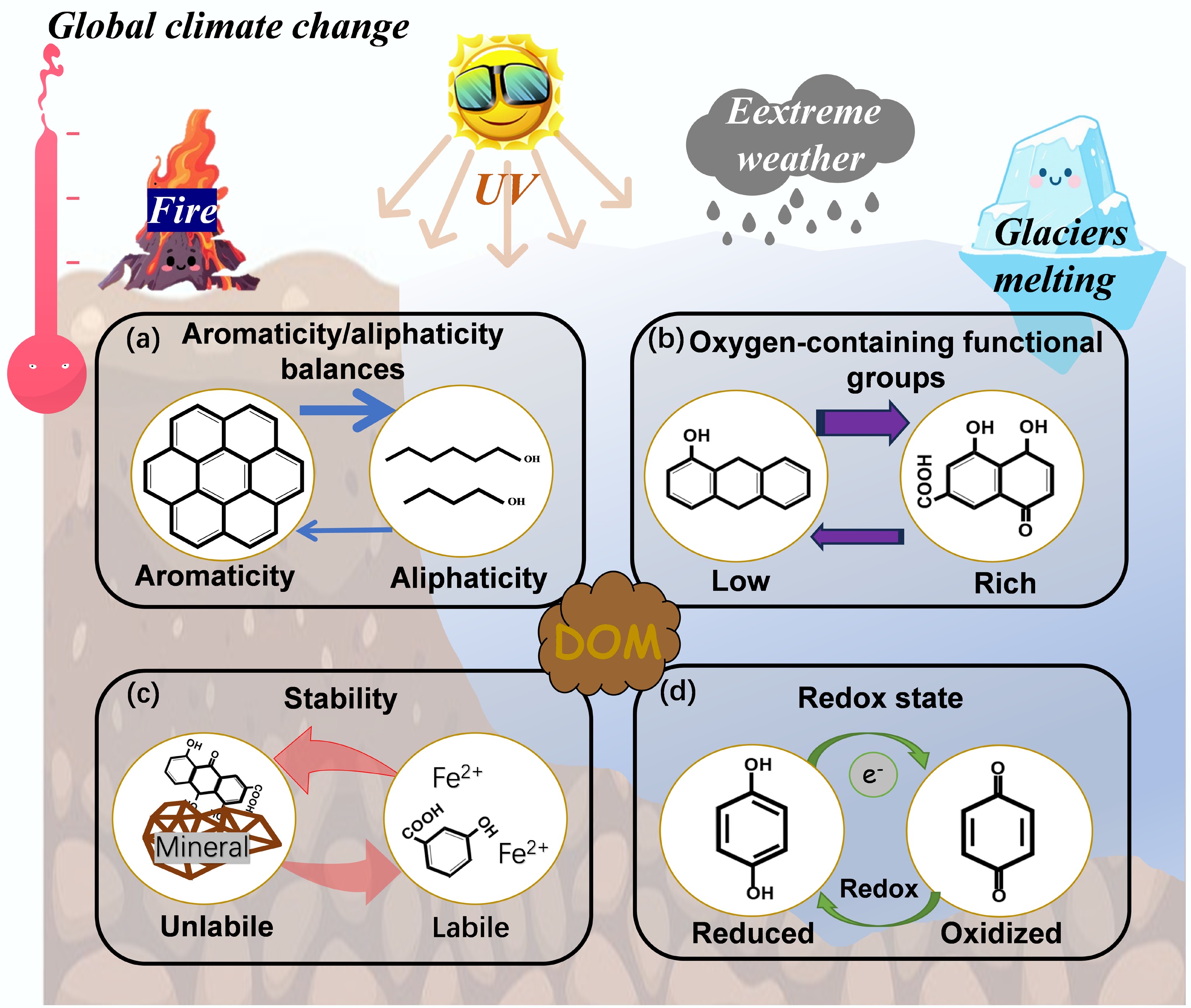

The quality of DOM directly determines its functions in the ecosystem, including interactions with organisms[7], and is sensitive to environmental changes[8,9]. Here, the variability of DOM compositional traits is discussed, including aromaticity/aliphaticity balances, oxygen-containing functional groups, molecular weight distributions, and redox characteristics in the context of climate change.

Aromaticity/aliphaticity balances

-

Global warming-induced processes, including drought, wildfires, and permafrost thawing, may enhance the aromatic character of DOM while reducing aliphatic molecular constituents[10,11]. During glacial retreat, the release of ancient DOM rich in aromatic ring structures substantially elevates DOM aromaticity due to microbial metabolites and lignin residues[12]. Thus, the aromaticity of DOM is a sensitive indicator of climate change. Studies revealed that aromatic components are primarily released from the active layer, while permafrost strata lacking plant debris may contain higher proportions of aliphatic substances. Consequently, continuous thawing of permafrost driven by persistently rising temperatures may also increase aliphatic fractions in DOM[12,13]. Therefore, the transformation of DOM constituents exhibits pronounced dynamic variability under global climate change.

Generally, aromatic components (abundant in humic and fulvic acids, and tannins) exhibit higher chemical stability (the concept of "DOM stability" seen in Supplementary File 1) and lower bioavailability compared to aliphatic components (e.g., fatty acids, amino acids, and amino sugars)[2,14]. Elevated temperatures accelerate the decomposition of terrestrial soil organic matter, generally resulting in greater aromaticity of DOM[15]. However, due to shifts in the microbial communities responsible for DOM transformation, warming can yield results contrary to or even opposed to traditional notions. Recent research reported that under warming conditions, aromatic and highly unsaturated compounds with lower Gibbs free energy are preferentially decomposed by microbes, leading to their reduced abundance. DOM thus evolves toward thermodynamically stable forms (e.g., aliphatic compounds) whose decomposition requires higher activation energy, potentially prolonging carbon residence time[16]. This shift depends on microbial taxa. A modest warming of 1.3 to 1.5 °C elevates the Q10 of tropical soils by 8%–11%[17]. The warming process favors and activates subtropical microorganisms, enhancing their secretion of high-efficiency enzymes that accelerate the decomposition of aromatic DOM components.

Photochemical degradation is one of the most important processes in DOM transformation. The increased input of aromatic DOM into aquatic systems triggers water browning, consequently altering the photochemical dynamics of DOM. Terrestrial-derived DOM rich in chromophores (e.g., aromatic rings and conjugated double bonds) substantially enhances the contents of colored DOM, amplifying light absorption. Simultaneously, aromatic DOM serves as a strong photosensitizer, increasing the production of reactive oxygen species such as singlet oxygen, hydroxyl radicals, and excited triplet-state DOM, thereby accelerating the photodegradation of DOM itself[18,19]. It is commonly believed that photochemical degradation diminishes aromaticity[20]. But recent investigations revealed that after photochemical transformation, ponds with higher DOM contents showed increased DOM aromaticity, contrasting with the reduced aromatic components in organic-poor ponds[21]. Unlike the direct CO2 generation via partial oxidation of aliphatic functional groups and photo-decarboxylation in DOM, this unique photodegradation-induced enhancement in aromaticity stems from the synergistic effects of: (1) photolytic release of aromatic DOM precursors from particulate organic carbon; (2) demethylation yielding highly unsaturated compounds and polyphenols; and (3) photooxidative ring-opening of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons generating monomeric monocyclic aromatic acids (e.g., benzoic acid derivatives). Owing to their molecular complexity and the comprehensive biogeochemical processes affected by climate change, no unified model currently exists to fully explain the processes and associated mechanisms of DOM aromatic/aliphatic transformation. This remains a crucial research frontier warranting further investigation.

Changes in oxygen-containing functional groups

-

The oxygen-containing functional groups in DOM represent important reactive components and are highly dynamic during climate change. Polarity index (O/C ratio) is frequently used to describe the abundance of oxygen-containing functional groups[22]. Owing to the thermodynamic selectivity of DOM molecules and preferential microbial decomposition, elevated temperatures accelerate the breakdown of aromatic compounds with high O/C ratios, while aliphatic and peptide-like compounds with low oxygen content accumulate due to their recalcitrance, progressively lowering the overall O/C ratio of DOM over time[16]. Terrestrial DOM generally exhibits higher O/C ratios than aquatic DOM[23], but microbial communities govern DOM O/C ratio alterations during climate change. For example, fungal communities actively mineralize litter to generate DOM with a higher O/C ratio, whereas bacterial consortia selectively utilize DOM with a high O/C ratio, thereby reducing O/C ratios[5]. Thus, although initial permafrost thaw releases DOM with high O/C ratios, the following microbial activities, especially promoted by global warming, preferentially degrade high-O/C-ratio compounds[24].

Among the oxygen-containing functional groups, carboxyl groups are the most important acidic functional groups in DOM. Warming-induced glacier melting or storm runoff introduces large amounts of terrestrial DOM rich in small molecular carboxylic acids (e.g., oxalic acid)[25]. Rising temperature also stimulates algal productivity, augmenting the release of biogenic carboxyl moieties. However, warming could enhance microbial respiration, accelerating soil microbial decarboxylation, especially of low molecular weight hydrophilic compounds, leading to a decrease in their relative abundance[26].

Phenolic hydroxyl moieties also demonstrate climate-dependent dynamics characterized by alternating patterns of accumulation and depletion. With increasing temperature, the activated soil oxidases degrade lignin into humic substances rich in phenolic hydroxyl groups, thereby increasing their abundance in DOM[27−29]. Unlike carboxyl groups, phenolic hydroxyl groups are more chemically recalcitrant and typically require oxidative enzymes for degradation. Under oxygen-deficient conditions, the activity of phenol oxidases is inhibited[28], leading to the accumulation of phenolic compounds[30]. But in oxidative conditions, phenolic structures could be preferentially degraded by microbes, thanks to the enhanced catalytic activity of microbial extracellular oxidases (e.g., lignin peroxidase, manganese peroxidase, and laccase) under climate warming[31]. Thus, in permafrost regions, while increased precipitation initially enhances terrestrial lignin inputs (causing temporal phenolic enrichment), subsequent oxidative and photo-degradation rapidly depletes these compounds[32].

Therefore, these oxygen-containing functional groups are highly reactive and readily transformed under climate change. It may not be practical to describe the composition change of all these functional groups. But if the reactivity of DOM could be generally described, it would greatly facilitate the understanding of its environmental implications as affected by climate change, which will be specifically discussed in the following section.

Changes in the reactivity and stability of DOM

-

The importance of studying DOM quality change lies in the fact that the chemical compositions and structures of DOM determine its reactivity and stability. DOM reactivity could be primarily described by its redox potential, which correlates with its electron-transferring active functional groups, such as quinone moieties. Quinone moieties are the most reactive compositions of DOM[33]. They are oxidation products of phenolic hydroxyl groups, and generally increase under high-temperature and oxygen-rich conditions[34]. Increased temperature promotes oxidative conversion of phenolic electron donors to quinonic electron acceptors[31]. The accumulation of quinones results from the irreversible transformation of phenolic hydroxyl groups and the increased resistance of quinones to microbial degradation. In anaerobic permafrost zones, quinones can be reduced to hydroquinones by Geobacteraceae bacteria, but this process is inhibited by elevated dissolved oxygen in meltwater[35]. Notably, frequent wildfires elevate condensed polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, phenolic hydroxyls, and reduced moieties (e.g., thioethers, amines)[36], thereby enhancing electron-donating capacity[37]. Clearly, quinone content variation is highly region-dependent. Understanding the transformation between quinones and semiquinone radicals is essential to evaluating their environmental and ecological roles. However, no study has yet provided a quantitative framework for the impacts of climate change on phenol-quinone redox cycling.

DOM stability is a fundamental parameter to evaluate the alteration from organic carbon to CO2 discharge. Besides the chemical stability determined by their structural compositions (such as aromatics over carboxylic acids as discussed above), physicochemical rearrangement of DOM aggregates is also concurrent with climate change. For instance, warming accelerates dissolution of Ca2+-bearing minerals; liberated Ca2+ engages in ligand exchange with carboxyl groups, forming soluble coordination complexes that enhance net retention of carboxyl functionality within the DOM pool[38]. Under arid conditions, dehydration-driven protonation and cation bridging strengthen interactions between polar DOM functional groups (e.g., carboxyls) and minerals, yielding stable insoluble organo-mineral assemblages[39]. These processes significantly enhance structural stability and suppress CO2 efflux. Conversely, humid conditions trigger reductive dissolution of Fe2+-bound DOM, liberating substrates while sustaining microbial activity in high-OC soils, ultimately accelerating DOM mineralization and CO2 emission[39,40].

Therefore, climate change profoundly shapes the chemical composition, functional group distribution, reactivity, and stability of DOM (Fig. 1). Resolving the molecular architecture of DOM is a critical step in predicting its environmental fate. Contemporary analytical workflows predominantly employ complementary techniques. Among these, spectroscopic methods generally offer non-destructive advantages with minimal sample pretreatment, yet provide limited information. While Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry provides powerful molecular characterization, requisite filtration and acidification pretreatments yield only partial information on the molecular weight because of the possible loss through selective DOM fractionation[41]. These techniques can be used in combination to obtain more comprehensive structural information. For example, while TIMS-FT-ICR MS/MS operates without prior chromatographic separations, its pretreatment requirements are more stringent[42]. Simultaneously, it faces issues such as high testing costs that hinder widespread adoption. To obtain more specific and thorough DOM insights, it remains imperative to either refine pretreatment methodologies or develop non-destructive analytical approaches. Additionally, considering that DOM turnover may have been accelerated during global warming, an instant observation on DOM composition or structural change may not provide complete information to evaluate DOM environmental functions. It may be an important new research demand to obtain the overall residence times of representative structures (not only the bulk carbon content) or properties (such as redox potential) in the background of climate change. Global carbon cycling models will benefit greatly if this parameter is incorporated.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model illustrating climate change-induced alterations to DOM quality, driving transformations across key molecular characteristics: (a) aromaticity vs aliphaticity, (b) oxygen-functional group content, (c) stability (labile vs nonlabile), and (d) redox state. The larger arrows denote transformation pathways under a broader range of global climate change scenarios.

-

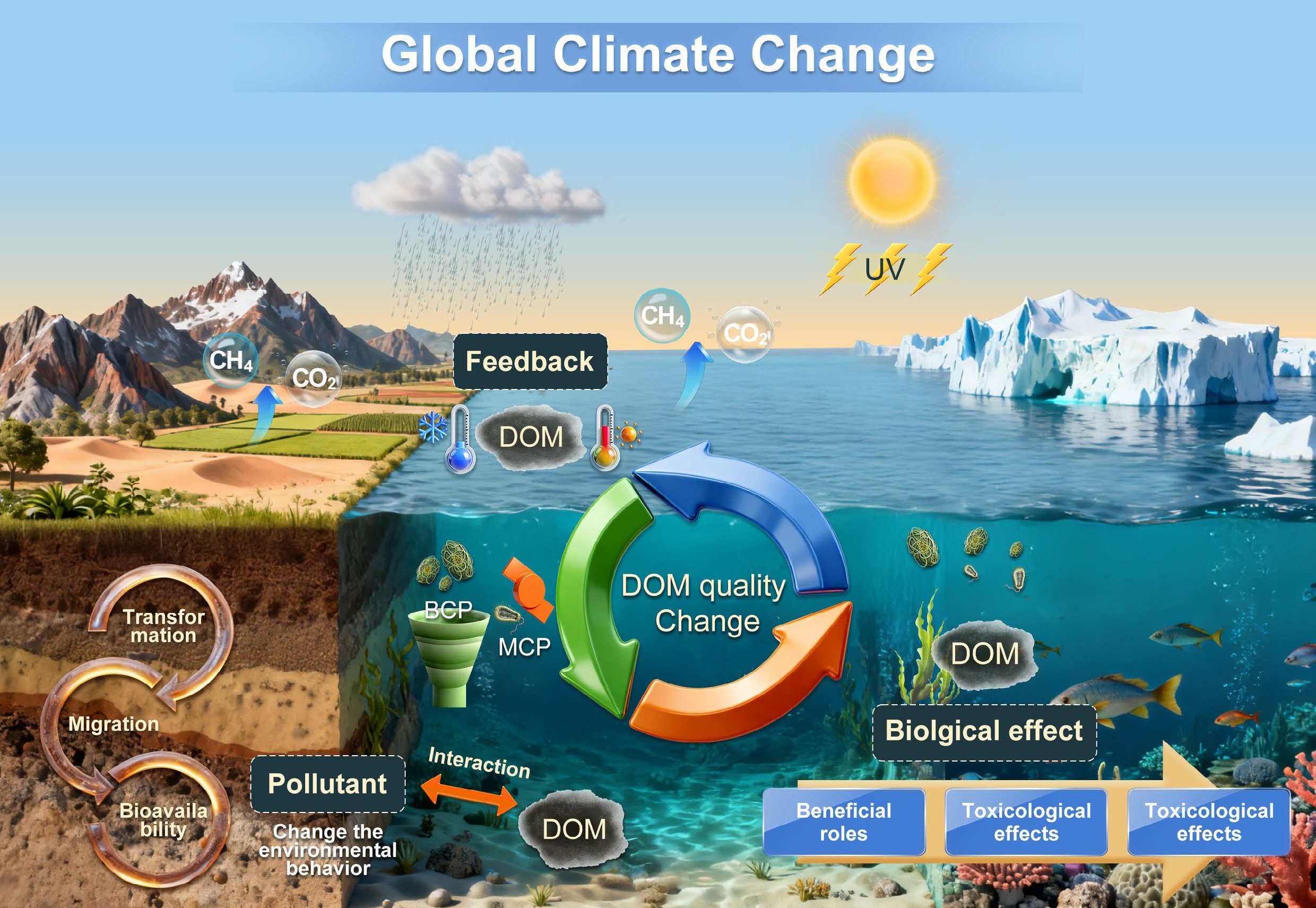

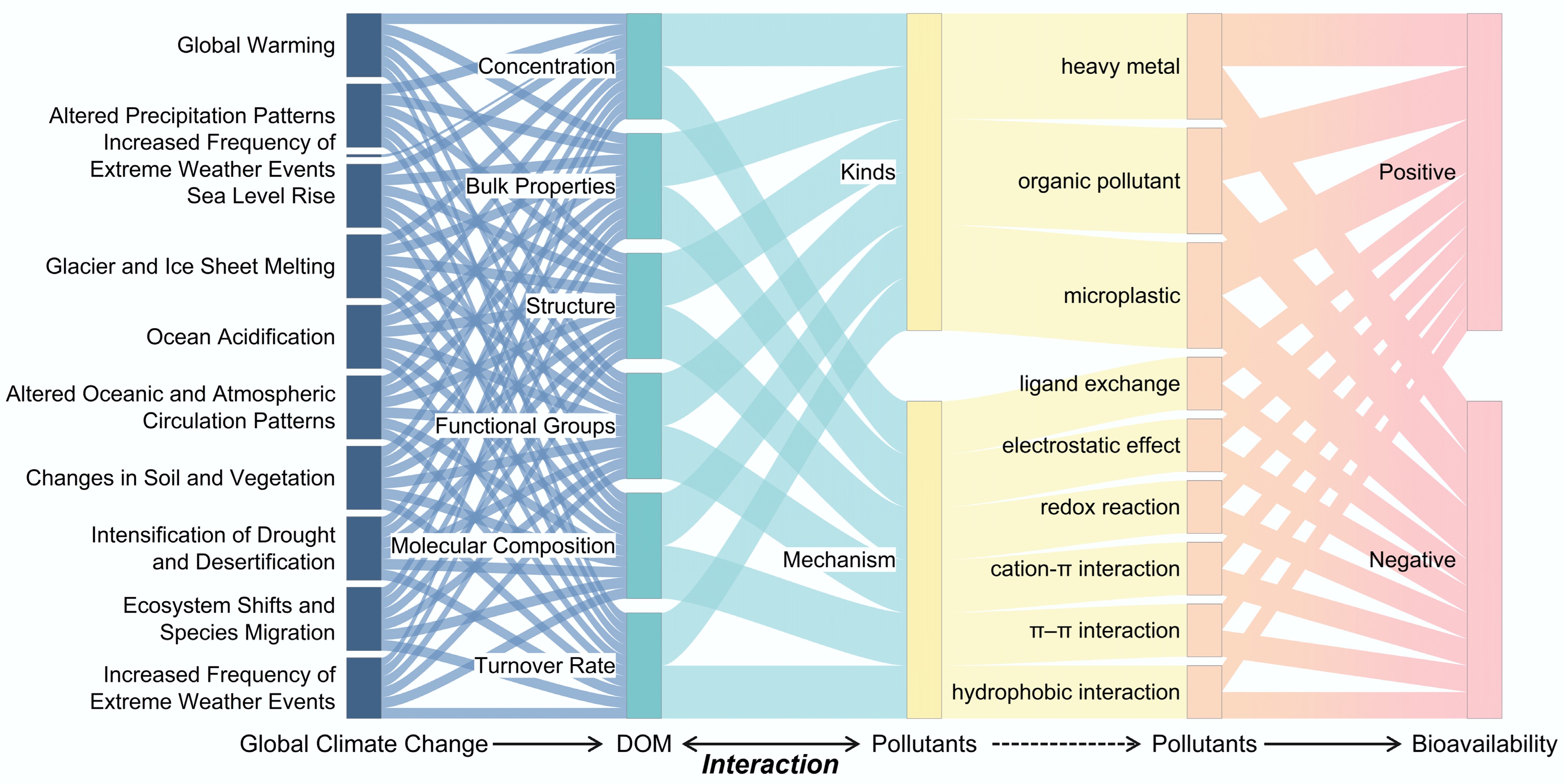

The diverse structure and biogeochemical processes of DOM play a key role in regulating pollutant migration and transformation. As shown in Fig. 2, global climate change alters DOM concentration, molecular composition, and redox properties as well as environmental conditions, which in turn shift DOM-pollutant interactions.

Figure 2.

Influence of global climate change on DOM properties and interaction with pollutants. Global climate change includes ten common events. DOM properties include concentration, bulk properties, structure, functional groups, molecular composition, and turnover rate. The interactions between DOM and pollutants include ligand exchange, electrostatic effect, redeox reaction, and cation–π/π–π/hydrophobic interactions.

DOM-heavy metal interactions

-

The structure of DOM fundamentally dictates heavy metal migration and transformation. For example, the increased oxygen-containing functional groups during climate warming could strengthen DOM-metal coordination through electrostatic attraction or ligand exchange (commonly referred to as inner-sphere complexation). Moreover, climate warming-induced droughts, wildfires, and permafrost thaw increase the proportion of aromatic structures in DOM, promoting heavy metal (e.g., Cd2+ and Zn2+) association through cation−π interactions[43,44].

Conventional understanding holds that heavy metals strongly complexed with DOM exhibit reduced bioavailability[45]. It is noteworthy that the toxicity of certain organometallic species is many times higher than their ionic counterparts, such as methylmercury. On one hand, the increase in temperature enhances the methylation process of microorganisms, resulting in a 10-fold increase of methylmercury in soil[46]. Additionally, Hg-DOM is more prone to bioaccumulation, promoting biomagnification while simultaneously increasing the microbial mercury methylation process[47]. On the other hand, DOM may promote the degradation of methylmercury. Research observed that methylmercury-DOM complexes could be photodegraded primarily through intramolecular electron transfer rather than the action of ROS. Thus, when methylmercury binds with DOM that has sulfur-containing ligands (such as glutathione and thioglycolate), the degradation rate is faster than methylmercury[48].

The generally reduced DOM molecular weight during climate change may enhance the heavy metal-DOM complexation[49]. Thus, the increased abundance of low molecular weight DOM is always accompanied by the increased total metal contents in the water body[50]. However, previous research found that increasing their concentration does not necessarily increase their unit complexation capacity. For instance, the strong electrostatically assisted hydrogen bonding between DOM molecules can actually reduce DOM-Cu complexation[51]. This effect is determined by the balance between the binding energies of the DOM intermolecular interaction and their complexation with heavy metals. Hence, climate-induced DOM concentration change and structural transformation alter its binding with heavy metals directly or indirectly, which is a frequently overlooked process that may impact heavy metal bioavailability predictions.

DOM redox properties are closely associated with the transformation of heavy metal valence states or speciation, but are highly dynamic during climate change. DOM could be enhanced either for its reductive properties, such as during heavy rainfall and flooding[52], or for its oxidative properties, such as light irradiation[53]. The redox processes always determine heavy metal behavior and toxicity. For example, some metals show enhanced toxicity after reduction, such as As(IV) reduction to As(III), whereas other metals are more toxic after oxidation, such as Cr(III) oxidation to Cr(IV). Although the bioavailability of Hg(II) is higher than that of Hg0, its toxicity is lower. Therefore, evaluating heavy metal risks as affected by climate change should carefully consider the change in DOM redox property.

Beyond climate-induced DOM structural changes, global warming drives a series of environmental condition shifts, including temperature rise, hydrological changes, and water acidification, that also influence DOM-heavy metal interactions. Since DOM-heavy metal complexation is a thermodynamically controlled process and most reactions are endothermic, rising temperatures can accelerate the rate of DOM-metal binding, but decrease the extent of their binding. It is still unknown how to incorporate these processes in heavy metal toxicity evaluation, especially considering the generally non-equilibrium systems in the environment.

Interestingly, DOM and heavy metals show their mutual buffering during climate change. The warming enhances metal dissolution, which increases their mobility and potentially toxicity[54]. For example, glacier melt-induced flooding events can release metals (e.g., Pb, As, and Pt) at levels over ten times higher than non-flooded conditions due to massive terrestrial DOM inputs[55]. DOM may promote the release of heavy metals and metalloids[56], but the simultaneously increased DOM release could efficiently bind with heavy metals and decrease their toxicity. On the other hand, although DOM release is enhanced during climate warming, the greater DOM-metal binding generally decreases DOM bioavailability and potentially increases DOM persistence. Some research also found that during freeze-thaw cycles, high molecular weight-rich humic acids in neutral-pH water bodies can form colloidal flocculation precipitates through complexation with Fe/Al/Mn, thereby decreasing DOM mobility and increasing their persistence[50].

DOM-organic pollutant interactions

-

Climate change, such as elevated temperatures and shifting precipitation patterns, typically increases DOM concentration in waterbodies and consequently the formation of DOM-pollutant complexes. This enhanced complexation often reduces the immediate bioavailability of organic pollutants, but may facilitate their transport over longer distances, generally because of the solubility enhancement and/or physical protection from degradation. However, because of the diverse properties of vast organic pollutants, the apparent impacts should be evaluated in DOM-pollutant pairs. For hydrophobic organic pollutants, usually the DOM aromaticity is crucial[57]. Therefore, the changes in DOM hydrophobic compositions, such as aromatic content from humification processes or thermal alteration[58], are the major research focus[59]. But for weak hydrophobic organic pollutants (such as pharmaceuticals and personal care products), the hydrophilic compositions of DOM may have a more profound impact from the following three aspects: (1) They may compete with each other on mineral particles for sorption sites and thus promote the transport of organic pollutants; (2) they may form complexation in cation-rich environments through cation bridging; and (3) hydrophilic DOM may elevate microbial activity and promote organic pollutant degradation.

Studies suggest that DOM could form micelle or pseudo-micelle structures at proper water chemistry conditions[60], and in some cases, critical micelle concentration was even applied to describe DOM characteristics, especially when studying hydrophobic organic compound (HOC) behavior[61]. HOCs are reported to partition in the hydrophobic domains of DOM, which could greatly enhance their solubility and thus transport[62]. DOM molecular structures with both hydrophobic and hydrophilic ends are beneficial for micelle formation. Clearly, the decreased DOM molecular size due to climate warming will not favor micelle formation. It is still unknown how and to what extent the change in the DOM molecular reorganization will alter the environmental behavior of HOC.

Global climate change significantly accelerates DOM turnover rates, thereby further complicating the non-equilibrium processes of DOM-mediated organic pollutant behavior. DOM has the most dynamic composition in terrestrial systems. Its interaction with organic pollutants could hardly be described by any static model. For example, DOM is continuously released from soil or sediment, with highly heterogeneous compositions. DOM is selectively adsorbed on mineral particles, with specific fractions selectively adsorbed. DOM molecular configuration is always changing with water chemistry conditions, especially in waterbody confluence and estuary areas. Accelerated DOM turnover will surely coincide with these processes. The kinetic rates of the above-mentioned processes should all be adjusted with climate change, with a highlighted consideration of DOM turnover rate change.

DOM-microplastics interaction

-

The large-scale release of microplastics into the environment has received considerable attention due to their inherent environmental risks and role in carrying other pollutants. Their interactions with DOM are ubiquitous and should be investigated in the context of climate change, particularly with respect to changes in the structural and molecular composition of DOM induced by climate change. Increased humification under warmer conditions or during prolonged droughts typically enhances DOM aromaticity, which strengthens π−π stacking and hydrophobic interactions with hydrophobic microplastic surfaces, such as polyethylene, polypropylene, polystyrene, and polyvinyl chloride[63,64], and thus further enhances the stability of DOM-microplastic aggregates.

Conversely, elevated microbial activity and higher temperatures, combined with increased photochemical reactions (such as intense UV exposure and wildfires), promote the formation of smaller but more reactive DOM fractions. These labile DOM molecules exhibit weaker binding affinity to microplastics but greater chemical reactivity[64,65], facilitating microplastic mobility and bioavailability in ecosystems. As discussed earlier, reactive DOM fractions generate ROS under UV exposure, directly accelerating microplastic surface oxidation and fragmentation into smaller, biologically available nanoplastics[66,67]. Nanoplastics are more easily taken up by planktonic organisms and can cross biological membranes more easily. This significantly increases their potential for trophic transfer, bioaccumulation, and ecological risk. Additionally, quinone and phenolic groups facilitate electron-transfer reactions and ligand-exchange processes at the DOM-microplastics interface[68,69], driving the leaching of additives such as brominated flame retardants. This simultaneous oxidative degradation and additive release profoundly alter the toxicological profiles of microplastics.

Climate change accelerates the degradation of microplastics, which are becoming an increasingly important part of DOM. Elevated temperatures directly accelerate hydrolytic and oxidative degradation processes in polymer matrices, increasing the leaching rates of chemical additives from microplastics[70,71]. Intensified solar radiation (particularly UV-B radiation) amplifies the photodegradation of microplastics, facilitating DOM generation from the plastics themselves[72,73]. These interactions form a positive feedback loop, where photochemically aged DOM further enhances microplastic surface oxidation, erosion, and fragmentation[69,74], thereby increasing microplastic exposure and ecological risks across various ecosystems.

Therefore, considering the massive application of plastics and that the DOM generated from microplastic degradation is always reactive, it is important to identify DOM compositions or fractions contributed by microplastics. Currently, no technique has been established to quantify the chemical compositions of plastics in DOM, but extensive investigation is warranted. Research is recommended to incorporate the technique concepts from molecular markers, isotope tracing, and spectral analysis[75]. Molecular biomarker approaches, which track specific plastic additives or polymer-derived monomers in DOM, are limited by variable degradation rates and overlapping markers among different plastics. Natural DOM background similarly complicates signal attribution, undermining specificity and quantitative accuracy[76]. Isotope-based methods (e.g., δ13C, δ14C) offer reliable insights into carbon origin, yet the small isotopic offsets between plastics and terrestrial or aquatic organic matter blur their distinctions[77,78]. Moreover, isotopic signatures shift during environmental aging and mixing, complicating source apportionment, and require extensive isotope fractionation characterization across polymer types. Spectroscopic techniques such as UV–vis, fluorescence, and FTIR can rapidly screen for plastic-derived DOM by identifying chromophoric or structural spectral features[79]. However, their low resolutions struggle to resolve signals within complex DOM matrices, and common spectral overlap between plastic photo-products and natural DOM limits detection specificity and quantification reliability. To improve plastic-DOM quantification, future research should integrate multiple analytical approaches, for example, high-resolution mass spectrometry combined with targeted molecular markers to resolve polymer-specific signatures, compound-specific stable isotope analysis with calibration for different plastic types and aging processes, as well as multimodal spectro-hyphenated techniques (e.g., spectroscopy coupled with MS and online isotopic tracking). Here, an integrated analytical approach is proposed to provide a practical framework to identify and measure DOM contributions from microplastic degradation. First, polymer-specific molecular markers in DOM can be targeted. Plastic degradation releases unique low-molecular-weight compounds. For example, polystyrene produces distinctive styrene oligomers (e.g., styrene trimers), which serve as chemical signatures of microplastic-derived DOM[80]. Detecting such oligomeric byproducts or plastic additives (like bisphenol A or phthalate plasticizers) in DOM indicates the presence of DOM from microplastic sources[81]. High-resolution mass spectrometry can be employed to identify and quantify these markers, as recent advances allow detection of specific plastic-derived formulas in the complex natural DOM matrices. Second, stable carbon isotope tracing offers a quantitative means of determining the contribution of fossil carbon from plastics. Petroleum-based plastics are 'radiocarbon-dead' (Δ14C ≈ −1,000‰) and often exhibit δ13C values distinguishable from modern organic matter[82]. Thus, measuring the δ13C of DOM can reveal an isotopic offset that quantifies the microplastic-derived fraction. Finally, spectroscopic characterization of DOM provides an additional operational tool for quantification. Ultrahigh-resolution mass spectrometry can resolve thousands of DOM components to detect polymer-derived compounds at the molecular level[76]. By integrating these methods, targeted molecular markers, isotope ratios, and spectroscopic fingerprints, researchers can more confidently detect and quantify DOM derived from microplastics in environmental samples. Additionally, building a global database of plastic-specific DOM fingerprints, including molecular, isotopic, and spectral data across polymer types and environmental conditions, will be essential to standardize methods and improve quantitative discrimination of plastic-derived DOM in natural waters.

-

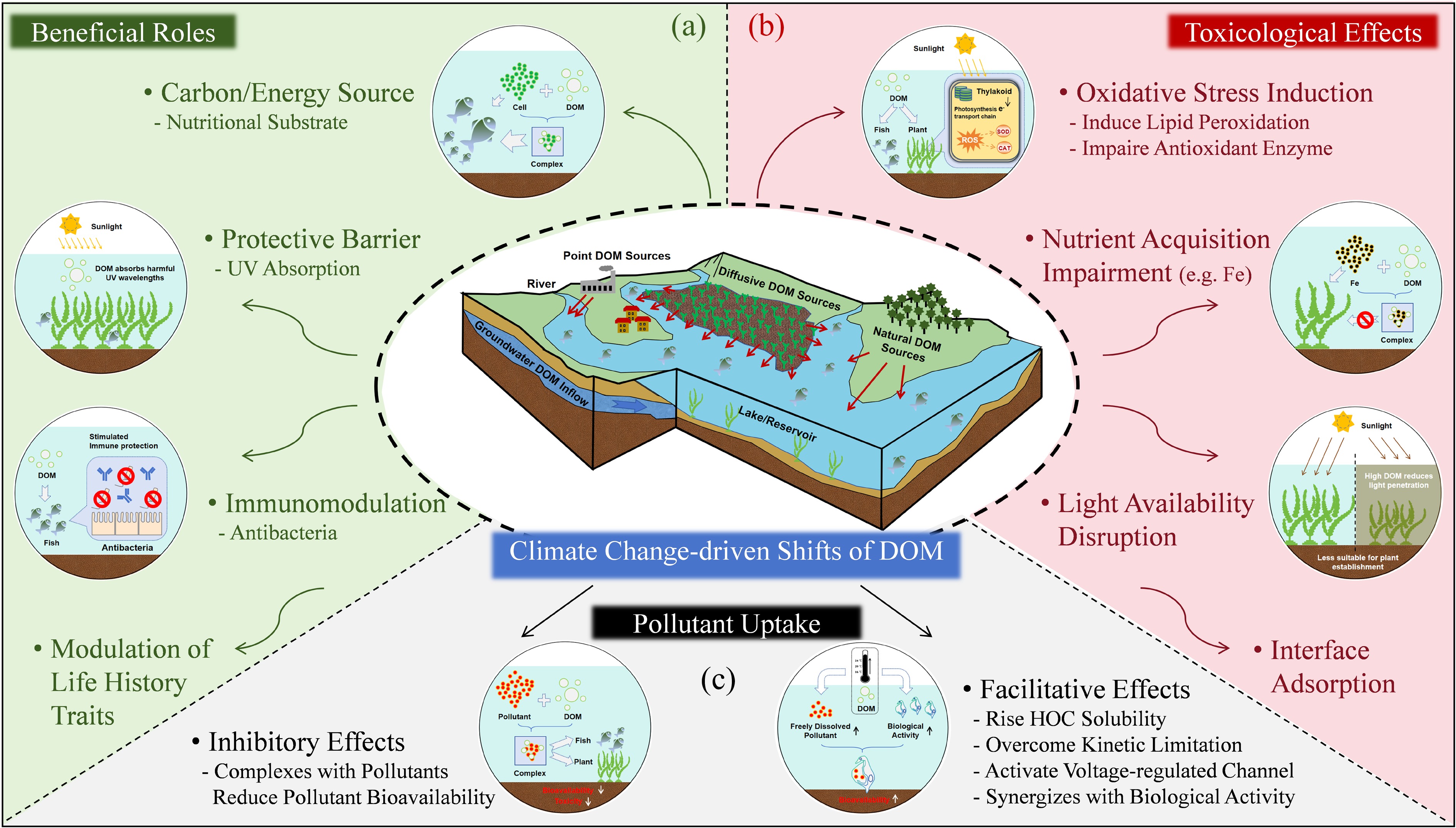

Climate change-driven shifts in the quantity and quality of DOM are profoundly altering its biological effects. The biological effects of DOM are summarized in Table 1. Here, the biological roles of DOM are reviewed through three aspects (Fig. 3): (1) its beneficial roles as a carbon/energy source, protective barrier, immunomodulator, and longevity drug; (2) its toxicological effects, including induction of oxidative stress, impairment of nutrient acquisition, and disruption of light availability; and (3) its complex effect on the uptake of pollutants by organisms.

Table 1. Biological effects of DOM

Classification Effect type Mechanism Ref. Beneficial role Carbon/energy source (i) Acts as a fundamental carbon/energy source; [83] (ii) Provides a nutritional substrate with low-nutrition-level organisms. [84] Protective barrier (i) Stimulates mucus secretion and antibacterial effectors; [91] (ii) Reshapes mucosal microbiota; [93] (iii) Absorbs harmful UV wavelengths to reduce DNA damage and maintain photosynthetic efficiency. [94] Protection Delay the aging of photosynthetic apparatus. [96] Modulation of life history traits Concentration- and quality-dependent effects:

(i) Low-to-moderate levels: enhance immune competence, antioxidative protection;[97] (ii) Increase hatching of fish larvae; [87] (iii) Induce multiple and transgenerational stress resistance; [88] (iv) Extends lifespan of invertebrates; [121] (v) Increase offspring numbers; (vi) Hydroxybenzene-enriched DOM improves thermal stress. [86] Toxicological effect Oxidative stress induction Generates ROS via redox-active functional groups (e.g., quinones), inducing lipid peroxidation and impairing antioxidant enzymes. [99,122] Nutrient acquisition impairment Complexes with essential elements (e.g., Fe(III) via -COOH, -OH groups) to form non-labile complexes, reducing free nutrient availability and inhibiting photosynthetic electron transport. [101] Light availability disruption (i) Chromophoric DOM absorbs sunlight, reducing its transmission depth and bioavailability; [102] (ii) High levels of humic substances enhance light absorption, constraining photosynthesis of submerged plants. [105] Interface adsorption (i) Adsorbs on mineral surfaces: Reshapes microenvironments and reduces microbial colonization. [106] (ii) Adsorbs on biological surfaces: Impairs physiological processes. [107] Pollutant

uptakeInhibitory effects Binds/complexes with pollutants, decreasing their free dissolved fraction and bioavailability, thus lowering bioavailability/bioaccumulation. [108] Facilitative effects (i) Increases solubility of HOCs via complexation, facilitating uptake by filter feeders; [112,114] (ii) Overcomes kinetic limitations: Rapidly donates pollutants to transporters, accelerating uptake; [117] (iii) Activates voltage-regulated channels for pollutant (mostly ionic pollutant) uptake; [119] (iv) Synergizes with biological activity: Warming-induced metabolic acceleration increases uptake of both free and DOM-associated pollutants. [120]

Figure 3.

Biological effects of DOM under climate change, illustrated through three aspects: (a) Beneficial roles as a carbon/energy source, protective barrier, immunomodulation, and modulation of life history traits; (b) Toxicological effects including oxidative stress induction, nutrient acquisition impairment, light availability disruption, and interface adsorption; and (c) Complex effect on the uptake of pollutants by organisms.

Beneficial roles of DOM

-

In general, DOM serves as a fundamental carbon and energy source for soil and aquatic organisms. For instance, paddy soil-derived humic acid-like DOM enhances Microcystis aeruginosa growth by augmenting nutrient availability, photosynthetic efficiency, and stress tolerance[83]. DOM adsorbed on bacterial cells also provides a nutritional substrate for nematodes, which is an important route for DOM uptake by Caenorhabditis (C.) elegans[84]. The generally enhanced DOM concentration due to climate change will surely provide more energy support to biological processes. In addition to the function of DOM as 'emergency' food ('survival in nutritional deserts' as phrased by Forward Jr et al.[85]), it is a longevity drug[7,86−88] and a source of epigenome methylation[89]. In the nematode C. elegans and the water flea Daphnia magna, DOM expands lifespan and enhances resistance to hyperosmotic stress in the water flea Moina macrocopa. This longevity effect could be enhanced by increasing the hydroxybenzene moieties in the DOM source[86]. Furthermore, stress tolerance can be transferred to the offspring[87], likely due to DOM-mediated DNA methylation[89]. These beneficial effects can be increased when increased global temperatures result in phenol-enriched DOM, as discussed above. However, these beneficial effects may be offset or even overcompensated by adverse effects due to increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as singlet oxygen, as has been shown recently[90]. This suggests that the biological effects of DOM quality and quantity on biological interactions warrant extensive future study. Beyond its role as a carbon and energy source and longevity drug, DOM constructs an adaptive outer protective barrier for organisms, mitigating environmental stresses from climate change. It stimulates mucus secretion, releasing antibacterial effectors (e.g., immunoglobulins, lysozymes, and phosphatases) and reshaping mucosal microbiota, a critical component of the innate defense system[91−93]. Under intensified UV exposure, DOM preferentially absorbs harmful wavelengths (280−320 nm), reducing DNA damage (e.g., by 50% in Chlamydomonas sp.) and maintaining photosynthetic efficiency in surface waters[94]. Moreover, terrestrial plants with DOM-coated leaves maintain stomatal conductance during drought by minimizing UV-induced oxidative stress and optimizing water use efficiency[95]. Additionally, in the bristly stonewort (Chara hispida), humic substances delay the aging of the photosynthetic apparatus[96]. However, to some extent, DOM photolysis generates ROS, which may induce some negative impacts. This dualistic role of DOM warrants targeted investigation into its dose-dependent protective thresholds.

With global climate change, the increasing input and structural transformation of DOM in aquatic environments have profoundly altered its role as an immunomodulatory barrier for organisms. When evaluating the role of DOM in biological processes, two parameters should be carefully considered: (1) Biological impact is DOM-concentration dependent. For example, low-to-moderate DOM contents (20–50 mg C/L) enhance immune competence, whereas higher DOM doses (≥ 300 mg C/L) trigger oxidative stress, pro-inflammatory responses, and cellular cytotoxicity[97]; (2) Biological impact is DOM-quality dependent. For example, DOM enriched with hydroxybenzene moieties can enhance thermal stress tolerance and extend C. elegans lifespan by delaying linear growth, retarding reproductive onset, and reinforcing pharyngeal pumping activity[86]. With climate change-driven increases in aquatic DOM, long-term studies are essential to characterize DOM protective efficacy across organism life stages and trophic levels. In the study of two cladoceran clones, Menzel et al. demonstrated that DOM prepared using humic substances is a substrate for DNA methylation reactions[89]. The exposed animals responded to abiotic environmental stress. However, DOM-induced epigenetic responses may also be triggered by biotic stress. A recent paper shows that, in addition to histone acetylation, histone methylation is central to the development of trained immunity triggered by mannan-oligosaccharides[98]. One may hypothesize that DOM is a substrate not only for DNA methyltransferase reactions but also for histone methyltransferase reactions. Thus, DOM may contribute to trained immunity, as Lieke et al. have suggested. This aspect may become more important as global warming increases the number and survival rate of pathogens in the environment[97].

Toxicological effects

-

DOM induces ROS generation and thus can induce tissue damage through lipid peroxidation or impair antioxidant enzymes through cellular oxidative stress[91,99]. The ROS-inducing capacity of DOM correlates with its redox-active functional groups (such as quinones mentioned earlier)[100]. Unfortunately, these redox-active compositions may be enhanced during climate warming, such as by increased wildfire frequency and light irradiation.

In addition to oxidative stresses to organisms, DOM imposes a nutrient uptake barrier in aquatic organisms primarily through complexation with essential elements. In freshwater ecosystems, DOM chelates Fe(III) via oxygen-containing functional groups (-COOH, -OH), sequesters Fe(III) into non-labile complexes, reduces free Fe(III), and thus inhibits photosynthetic electron transport chains[101]. The extent to which increased DOM concentrations decrease nutrient uptake by organisms with climate warming is unknown.

It is also noted that DOM is a light screening medium. The increased DOM concentration in water bodies reduces the depth of sunlight through water, because the chromophoric DOM strongly absorbs sunlight and notably diminishes its transmission and bioavailability, which constrains the photosynthesis of submerged plants[102]. In general, chromophoric DOM exhibits spatiotemporal variability, which is associated with the seasonal release of autochthonous DOM from macrophytes or microalgae, the catchment-scale leaching of allochthonous DOM, and the extent of DOM decomposition and photolysis[103]. These dynamics regulate the concentration and composition of chromophoric DOM, wherein high levels of chromophoric DOM and dominance of humic substances confer significant sunlight-absorbing capacity[104,105]. However, how chromophoric DOM changes with climate warming, and its synergistic interactions with other factors such as suspended particles and phytoplankton growth in affecting sunlight attenuation, remain poorly understood.

The increased DOM concentration in the aqueous phase also promotes its attachment to inorganic or biological interfaces. With climate change, the increased DOM adsorption on mineral surfaces reshapes the micro-environment and reduces microbial colonization. For example, DOM adsorption on oligotrophic lake sediment depletes sediment O2 and severs carbon supply from host submerged plants, and thus, reduces arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi colonization and hyphal growth[106]. Moreover, DOM adsorption on cell and biological tissue surfaces restricts physiological processes, such as substance exchange and respiration. It has been reported that DOM adsorption on fish gill surfaces reduces ionic transport (e.g., decreased flux of Na+/Cl–) and lowers permeability properties[107]. Recently, with climate warming, the input of DOM in water bodies increases, and its negative impacts on the metabolism, proliferation, and colonization processes of organisms still require further research.

Pollutant uptake as affected by DOM

-

As global climate change alters DOM concentration and composition, its role in modulating pollutant-organism interactions becomes more complex. As discussed above, DOM can interact with various pollutants via complexation or binding[108]. Studies also suggested that the freely dissolved chemicals are more bioavailable, and thus, DOM-pollutant interactions generally decrease pollutant bioavailability and thus bioaccumulation[109]. If this were a definite situation, organism-pollutant interactions as affected by DOM could be easily modeled based on DOM-pollutant interactions. It would thus be practical to include the climate warming-induced DOM concentration and composition changes to predict organism uptake and food chain transfer of pollutants. However, climate change may have generated more complicated situations than a model can predict. For example:

(1) DOM could concentrate pollutants and increase pollutant exposure to organisms, and thus, the generally increased DOM concentration in due to climate warming may significantly promote pollutant uptake. The transportation of some pollutants, especially HOCs, is low because of their low solubility in water. Therefore, their toxicity is always evaluated with a focus on the accumulation in lipid tissue or through the food chain[110,111]. However, DOM-pollutant interactions will greatly enhance their solubility, and the DOM-concentrated pollutants may be trapped by the feeding apparatus of filter feeders[112,113], released after entering the digestive systems[114], or digested together with DOM[115].

(2) It is important to keep in mind that low DOM concentrations or certain DOM qualities are likely to block cell membrane-bound exporters[7] and lead to disproportionate bioaccumulation of organic pollutants[116]. Future studies are needed to determine if or how increased DOM concentrations or modulated DOM qualities may interfere with this process.

(3) In addition, DOM-complexed pollutants may overcome the kinetic limitations and accelerate pollutant uptake, which is apparent as increased pollutant uptake. In some cases, pollutant transport may be restricted by the slow complexation with the uptake transporters, known as kinetic limitation. If DOM can quickly donate pollutants to the transporters, pollutant uptake will be greatly facilitated[117]. However, it is unknown how changes in DOM properties in climate warming determine its shuttling ability for the pollutants.

(4) DOM opens voltage-regulated channels for pollutant (mostly ionic pollutant) uptake. For example, Gauthier[118] and Sánchez-Marín et al.[119] discussed that DOM may open voltage-regulated Ca2+ channels, through which several trace metal ions such as Pb2+ and Cd2+ could enter cells through membrane permeability. Similar voltage-regulated channels are also applicable to Na+ and K+[107]. However, the mechanism by which DOM properties activate Ca2+ channels remains unclear, which is crucial for the absorption of ionic pollutants.

(5) The activity of organisms may be significantly altered during climate change. The warming generally enhances the activities of organisms, and thus, a fast metabolism may be accompanied by a change in DOM input. For example, the uptake of pyrene by D. magna increased by 41.5% when the temperature increased from 16 to 24 °C[120]. The enhanced metabolic rates of D. magna may be a major reason for the increased uptake of both freely dissolved and DOM-associated pyrene. Similarly, DOM quality change is associated with its reactivity and caloric content, which will greatly affect the activity of organisms as discussed in two preceding sections.

-

Climate change has a diverse impact on the structural and functional features of DOM, while DOM transformation exhibits significant climate feedback effects that reciprocally regulate climate dynamics. The process includes both positive feedback loops that increase greenhouse gas emissions and negative feedback mechanisms that support carbon sequestration (Fig. 4). Consequently, a detailed understanding of climate feedback and DOM regulating mechanisms is critical for formulating evidence-based mitigation strategies to address current global climate change.

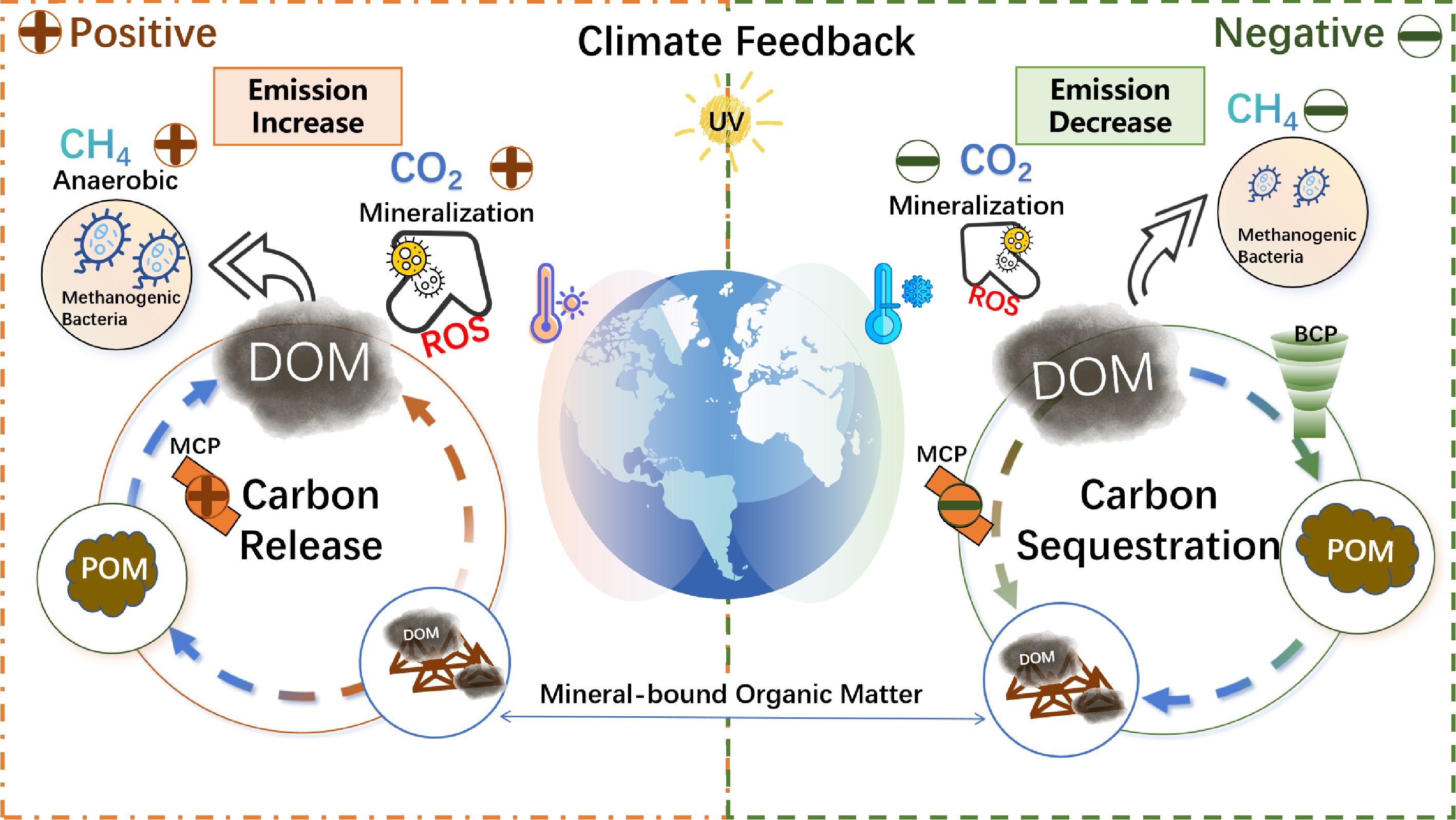

Figure 4.

Dual feedback mechanisms in climate regulation mediated by DOM dynamics. Global climate change modulates DOM transformation pathways, generating antagonistic climate feedbacks: positive feedback through greenhouse gas amplification (Positive) and negative feedback via carbon sequestration (Negative).

Positive feedback: DOM intensifies global warming

-

Rising temperatures cause permafrost thaw, which boosts microbial metabolic activity and CO2 emissions. Specifically, massive releases of permafrost-derived DOM could be directly photo-degraded or enhance microbial metabolic activity, thereby intensifying DOM mineralization through a synergistic positive feedback loop[123]. These conversions are also heavily influenced by redox circumstances. Under oxic conditions, oxygen acts as a metabolic gate, promoting organic carbon mineralization and allowing direct CO2 emission. In contrast, anoxic settings preferentially speed up the conversion of particulate organic matter to DOM, resulting in a temporary DOM concentration increase[124,125], or support the metabolic evolution of DOM towards more labile forms, particularly aliphatic molecules and nitrogen-rich lignin derivatives[126]. The conversion of nonlabile carbon to labile carbon alters organic carbon composition and mobility, whereas aquatic systems gradually move from carbon sinks to potential carbon sources.

CH4 has a significantly higher global warming potential (25 times higher than CO2), and thus attracted a great deal of scientific attention on its generation as affected by climate change[127]. In wetland ecosystems, high atmospheric CO2 concentrations could increase plant productivity while expanding substrate, such as DOM, availability for methanogenic archaea. This sets up a self-reinforcing cycle in which warmth encourages vegetation growth, which in turn provides more organic carbon for greenhouse gas generation (CO2 and CH4).

The positive feedback of DOM is also noted during eutrophication driven by warming. Climate-induced snowmelt enhances DOM concentrations in water bodies, which may promote eutrophication. In addition, UV light preferentially breaks down humic compounds, making surface water DOM more vulnerable to further breakdown[128]. The chromophoric DOM also enhances the light energy absorbance[103], which further increases water temperature and speeds up algal succession[129]. Additionally, hypoxic conditions created by eutrophication facilitate the production of CH4 in lakes[130].

Besides snowmelt and eutrophication, warming-induced increases in wildfire frequency raise concentrations of highly oxidized, mobile DOM molecules. Rising temperatures in subtropical forests increase the activity of oxidative enzymes[131], which could efficiently break down aromatic DOM released under pyrogenic conditions[132], thus enhancing positive feedback. When combined, these mechanisms provide a series of climatic feedback effects that exacerbate the effects of global warming.

Negative feedback: DOM buffers climate warming

-

The first negative feedback of DOM to climate warming is that the solubility of CO2 and CH4 will be enhanced in water bodies with elevated DOM concentration[133]. DOM generally provides a hydrophobic environment or micelle-like structures to trap the nonpolar molecules of CO2 and CH4, enhancing their apparent solubility beyond Henry's Law[134]. DOM may also buffer climate warming during its stabilizing processes. The increased DOM concentration in the aqueous phase is associated with the increased solid phase concentration through adsorption. This is probably why, although initial permafrost thaw emits greenhouse gases, long-term data show strong compensation by carbon sequestration[135]. Slowly building peat deposits in permafrost settings can retain over 50% of the carbon input. In some cases, methane sink intensities can even reverse carbon budgets.

The negative feedback of DOM to climate change is also determined by its chemical structures. It is widely accepted that various DOM compositions behave differently with environmental change. For example, Wang et al. observed a decline in the DOM fraction readily available to microbial utilization in four and a half years of warming[136]. The decreased DOM biodegradability will counteract the initial DOM increase and partly alleviate carbon loss. A similar phenomenon was observed in the situation of the accelerated oceanic deoxygenation driven by global warming, where recalcitrant DOM characterized by higher molecular weight, reduced saturation, and carboxyl-rich structures was accumulated[137]. In addition, in anaerobic conditions, phenolic compounds accumulate and inhibit hydrolytic enzymes[138]. Thus, increased DOM, especially lignin-derived DOM, could effectively impair the carbon mineralization pathway and present negative feedback to global warming.

Challenges in the assessment of DOM climate feedback

-

Atmospheric CO2 and CH4 concentrations have continuously escalated since the Last Glacial Maximum (~21 kyr BP). While melting glaciers drive terrestrial carbon loss, peatland formation over millennia has concurrently facilitated the emergence of novel carbon sinks[139]. Understanding and assessing the climate feedback of DOM remains a significant challenge. This challenge primarily stems from the molecular complexity of the DOM. Current knowledge regarding DOM structural characteristics remains limited, which consequently constrains the understanding of its climate feedback effects. To comprehend DOM climate feedback, it is essential to investigate its chemical and photochemical stability, thermal stability, and bioavailability, as these properties collectively determine DOM climate feedback mechanisms. For instance, aromatic DOM components exhibit greater chemical stability and lower bioavailability, yet demonstrate higher thermal stability and greater susceptibility to photochemical degradation[16]. The comprehensive evaluation of how these DOM characteristics influence climate feedback constitutes a critical research gap. DOM not only possesses complex molecular structures but also undergoes intricate source dynamics and transformation processes. Under global climate change scenarios, DOM sources have become increasingly heterogeneous, incorporating multiple complex inputs. Examples include enhanced terrestrial inputs from extreme precipitation events, pyrogenic carbon inputs following wildfires, and the release of ancient carbon from thawing permafrost[12,37]. Concurrently, these shifting DOM sources have altered DOM turnover processes, including intensified photochemical degradation, modified microbial metabolic strategies, and changes in mineral stabilization processes[140]. Such alterations ultimately affect DOM mineralization pathways (e.g., CO2 or CH4 production), contributing to substantial uncertainty in quantifying DOM-mediated climate feedback[141].

Furthermore, the superposition of multiple global climate change drivers amplifies the complexity of DOM dynamics. Climate warming concurrently occurs alongside altered freeze-thaw cycles, drought-flood transitions, enhanced solar irradiance, and eutrophication processes. These interacting factors may yield synergistic or antagonistic effects on DOM transformations. For instance, concurrently occurring warming and eutrophication synergistically enhance DOM mineralization, eutrophication promotes algae proliferation that stimulates microbial activity, thereby amplifying temperature-driven DOM mineralization and greenhouse gas emissions[16]. Conversely, coupled warming and wetting exhibit antagonistic effects, where increased moisture suppresses the warming-induced acceleration of microbial activity[40]. This creates significant challenges in quantifying CO2 emissions from DOM mineralization processes. The increasing frequency and abrupt transitions of extreme weather events under climate warming have become markedly evident in recent decades. These non-linear perturbations heighten the stochasticity of DOM dynamics and exacerbate uncertainties in predicting DOM-mediated climate feedback.

Critically, DOM climate feedback exhibits temporally dependent mechanisms. Short-term warming, for example, induces hypoxic conditions that destabilize Fe-DOM complexes, deplete sedimentary carbon stocks, and accelerate DOM mineralization, resulting in a positive climate feedback. Conversely, sustained oxygen depletion reduces bulk DOM decomposition rates, enhances carbon sequestration, and generates a negative feedback effect[142]. During permafrost thaw, short-term mineral sorption mitigates lateral DOM transport and reduces CO2 production, yielding negative feedback. However, upon mineral saturation, concentrated-release events intensify downstream mineralization and trigger long-term positive climate feedback[143]. Consequently, accurate assessment of temporally resolved DOM climate feedback requires elucidating the mechanisms of DOM biogeochemical transformation pathways across scales.

Furthermore, ecosystem complexity fundamentally modulates the climate feedback of DOM. The biological carbon pump (BCP) and microbial carbon pump (MCP) constitute two key drivers of DOM transformation. Phytoplankton-derived organic carbon generated via the BCP is enzymatically processed into labile DOM substrates, which, through synergistic BCP-MCP interactions, become reprocessed into recalcitrant DOM pools that sequester carbon and mitigate climate change[144]. However, this dampening mechanism exhibits ecosystem specificity. Under anaerobic conditions with active methanogenesis, such recalcitrant DOM fractions are enzymatically hydrolyzed by methanogenic archaea, ultimately generating CH4 that amplifies positive climate feedback[145]. Consequently, assessment of DOM climate feedback needs to take into account the composition of DOM, environmental conditions, and the interrelationship between the ecosystems.

-

DOM, serving as both a responder and regulator in global climate change, significantly influences global carbon cycling, contaminant modulation, biological effects, and ecosystem regulation through its own transformation. Here, the dual environmental effects of DOM under climate change are summarized, and current knowledge gaps alongside future research directions are discussed.

The double-edged environmental effect of DOM

-

The environmental effects of DOM exhibit dual-directional dynamics (e.g., source and sink interconversion), particularly under climate change scenarios, due to its compositional and structural complexity and diverse biogeochemical processes.

(1) DOM undergoes structural and property transformations under climate change. Global warming enhances its aromaticity and the abundance of carboxyl functional groups, yet its stability is determined by ambient environmental regulation and biogeochemical processes.

(2) Under climate change, DOM structural transformations typically promote its binding with heavy metals and organic contaminants, thereby reducing their bioavailability. However, climate-transformed DOM may facilitate the aging processes of microplastics, consequently increasing their ecological risks.

(3) Climate change may enhance the biological effects of DOM. DOM functions mainly through two pathways: (a) Positive: by serving as an energy source and enhancing immunomodulatory adaptation to promote organismal growth, effects contingent upon DOM concentration and molecular structure; (b) Negative: the promoted generation of ROS can inhibit metabolic processes, and the facilitated contaminant uptake will induce adverse biological impacts.

(4) DOM exhibits a bidirectional climate feedback mechanism. It can function either as a carbon source or a carbon sink. Although current literature predominantly reports DOM as contributing to positive climate feedback, this effect is highly context-dependent. Due to its structural complexity and the synergistic effects of climatic influences, the net impact remains uncertain.

Knowledge gaps and future directions

-

Current understanding of the transformation of DOM under climate change remains inadequate; systematic interdisciplinary research is needed to reduce existing knowledge gaps. As climate change manifests globally through intensifying extreme weather events, these processes concomitantly alter the environmental effects of DOM, warranting prioritized attention.

(1) Limitations in DOM structural characterization methodologies constrain the understanding of DOM transformation dynamics under global climate change, consequently restricting insights into its environmental impacts. Technological innovations in DOM structural analysis represent a critical pathway toward deciphering DOM behavior in environmental systems.

(2) Climate-driven DOM turnover engages multidimensional environmental biogeochemical processes intersecting meteorology, hydrology, geochemistry, mineralogy, ecology, environmental science, microbiology, and so on. Cross-disciplinary integration, specifically coupling meteorology with environmental chemistry to address intensifying extreme weather, must be prioritized. Quantitative parameters characterizing microbial functions and hydrogeological processes require urgent incorporation into climate change impact assessments.

(3) Climate change constitutes a global challenge, therefore, governments and research institutions worldwide are urged to enhance monitoring of dynamic DOM quality indicators (such as H/C and O/C ratios, composition and abundance of functional groups, and their redox potential) by establishing long-term observation networks, thereby capturing DOM variability across ecosystems to inform climate mitigation strategies.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: review conception and design: Zhao J, Steinberg CEW, Pan B, Xing B; data collection: Zhao J, Yuan Q, Lei X, Lieke T, Liu Y; manuscript drafting: Zhao J, Yuan Q, Lei X; revision and editing of the manucript: Steinberg CEW, Pan B, Xing B; supervision, project administration, and investigation: Pan B. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 42130711, 42107258, and 42407338), and the Yunnan Provincial Scientific and Technological Projects (Grant Nos 202202AG050019, 202501AT070307, 202501AS070138, and 202403AP140037).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Global warming enhances DOM aromaticity and carboxyl functional groups.

Warming-induced DOM transformations promote its binding with pollutants.

Climate change enhances DOM biological effects, both positively and negatively.

DOM can be a carbon source or a carbon sink depending on the circumstances.

The prediction of DOM impacts on climate change faces various challenges.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Supplementary File 1 Glossary of the associated terms: chemical stability and thermal stability.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao J, Yuan Q, Lei X, Lieke T, Liu Y, et al. 2025. The double-edged environmental effect of dissolved organic matter in global climate change. Environmental and Biogeochemical Processes 1: e009 doi: 10.48130/ebp-0025-0009

The double-edged environmental effect of dissolved organic matter in global climate change

- Received: 25 July 2025

- Revised: 11 September 2025

- Accepted: 23 October 2025

- Published online: 19 November 2025

Abstract: Dissolved organic matter (DOM) constitutes a core vector connecting organic carbon cycles in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, playing significant roles in various biogeochemical processes. Commencing from DOM quality variations, this review analyzes transformations in its structural properties (e.g., aromatic/aliphatic components, oxygen-containing functional groups, reactivity and stability) and biogeochemical processes (e.g., microbial and photochemical reactions and interaction with aquatic organisms) under global climate change with an emphasis on global warming. This study analyzes and synthesizes the current knowledge on climate-induced modifications to transport-transformation behaviors and bioavailability of environmental pollutants (heavy metals, organic pollutants, microplastics) governed by DOM, while assessing impacts of climate-driven DOM alterations on modulating functions in biological growth and metabolic processes, toxicological ramifications, and xenobiotic toxicity. Furthermore, DOM possesses a bidirectional climate feedback mechanism; its positive/negative feedback is dissected through carbon source-sink switching under climate change. The structural complexity of the DOM, together with the non-equilibrium state and multi-effect superposition characteristic of global climate change, collectively pose significant challenges to the accurate assessment of the climate feedback of DOM. Bidirectional environmental effects of DOM are critical for ecosystem functioning and human survival/development. Global climate change is altering the environmental effects of DOM by modifying its biogeochemical cycling; yet, current understanding remains constrained by system complexity. Systematic comprehension demands interdisciplinary collaboration to generate the necessary data for society to proactively mitigate climate change.