-

Per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are an extensive group of synthetic organic chemicals, distinguished by the presence of fluoroalkyl chains (−CF2), which exhibit a high persistence in the environment[1,2]. PFAS mobilizes in soil, air, and water, disrupting ecosystems and bioaccumulating in the food chain, affecting biota by direct or indirect exposure, including by ingestion[3]. Notably, these contaminants exert toxicity at very low doses, and have been detected in human blood repositories[4], suggesting significant bioaccumulation potential. The adverse effects of PFAS on human health include their association with elevated cholesterol levels, reduced vaccine responsiveness in children, and increased risk of developing cancers[1,5]. Many common PFAS have hydrophilic head groups (e.g., −COOH and −SO3H), and hydrophobic −CF2 backbones, rendering them mobile in the environment, including for plant uptake. There is increasing evidence of PFAS accumulating in various agricultural plant species grown in areas contaminated with PFAS, such as wheat (Triticum aestivum) grown in soil amended with PFOS from 25,000−50,000 ng/g[6]; cucumber (Cucumis sativus) grown in soil containing PFOS and PFOA at 1,000 ng/g[7]; PFOS in rice (Oryza sativa) at 0.57 ng/g, PFBA and PFOA in maize (Zea mays) at 0.24 ng/g, short chain PFCAs in soya bean (Glycine max) at 1.01 ng/g and PFBA and PFOA at 0.542 and 480 ng/g dw in wheat grown in ambient and industrial areas[8]; and other plant species like silver birch (Betula pendula), Norway spruce (Picea abies), bird cherry (Prunus padus), mountain ash (Sorbus aucuparia), ground elder (Aegopodium podagraria), long beech fern (Phegopteris connectilis), and wild strawberry (Fragaria vesca) grown in soil with the sum of 26 PFAS compounds ranging from 16−160 ng/g[9]. In Maine (USA), PFAS contamination was detected in milk from a dairy farm, which was then traced back to the forage the cows were consuming. The source of the PFAS was ultimately found to be biosolids (treated sewage sludge) that had been used as a soil amendment on the fields where the forage was grown, which led to contamination of the plants and subsequently the milk produced by the cows that grazed on them[10−12]. Clearly, the ability of PFAS to bioaccumulate in plants and enter the food chain is of great concern due to their persistence and potential health risks.

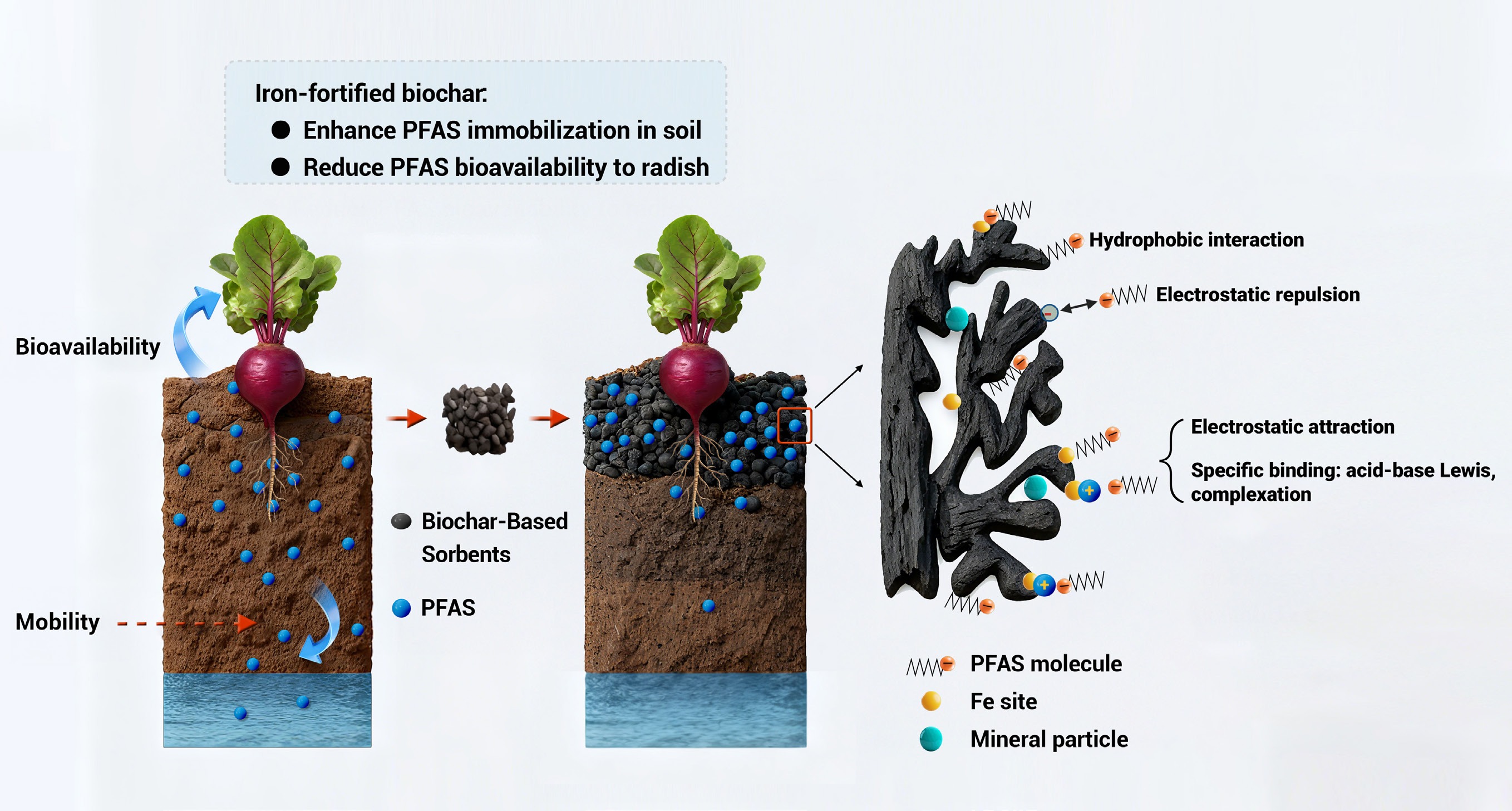

The use of sorbent amendments can minimize the availability, and/or mitigate the toxicity of other persistent soil and sediment contaminants such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs)[13]. This is a potentially cost-effective approach for the immobilization of PFAS in soil[14,15]. Carbon-based materials, e.g., activated carbon (AC) and biochar (BC), are common materials for sorbing and stabilizing PFAS, exerting both hydrophobic and electrostatic mechanisms of interaction[15,16]. Given the relatively low-cost and compatibility for use in agricultural activities[17], BC is a strong candidate for immobilizing PFAS in soil. Given what is known about BC sorption of other contaminants, its effectiveness is expected to be strongly affected by biomass source and pyrolysis conditions. More specifically, tuning the carbon structure with controllable surface area, pore size distribution, and other functionalities may significantly enhance the efficiency of PFAS sorption[18,15].

Previous studies have reported mixed outcomes. For instance, the application of coconut shell–derived activated biochar (at 2% by weight) reduced the leaching of PFOS, PFHxS, PFOA, and PFHxA by more than 99% in soils with both low (1.6%) and high (34.2%) total organic carbon (TOC) content[19]. Conversely, waste timber derived BC (WTBC) at 20 wt.% effectively reduced PFAS leaching by 23%–78% in low TOC soil[19]. Importantly, further activating WTBC (pyrolyzed at 900 °C) under CO2, enhanced efficacy to 63%–95% leaching reduction due to the modified pore structure and increased surface area of the activated BC[20]. In a separate study, BC derived from forest wood waste showed little impact on PFAS leaching from sewage sludge[21]. It is notable that although the ability of BC to immobilize PFAS in soil has become a topic of intense investigation, the effect of BC synthesis conditions and potential modification or activation for PFAS remediation is still poorly understood. In addition, the impact of BC on the bioaccumulation of PFAS in crop species in agricultural systems remains largely unknown. In one of the few studies on this topic, Zhang & Liang compared a commercial BC with AC and the PFAS sorbent RemBind® in soil at 2 wt.% for PFAS immobilization[22]. The authors reported that BC amendment reduced PFAS leaching from soil, although PFAS uptake by timothy-grass was increased. Thus, significant knowledge gaps limit our understanding of the risk of contaminated soil causing PFAS contamination of the food supply, as well as the ability to use sustainable soil amendments to alleviate or eliminate that risk.

In the current study, a series of hemp-derived BC sorbents produced by varying pyrolysis temperatures between 500 and 800 °C, with or without iron fortification (~8 wt.%), were prepared and characterized for PFAS immobilization potential in contaminated soil. Fortification of biochar with metals like iron can significantly enhance the functional properties and increase the efficiency of biochar used as a sorbent in different polluted environments. Iron introduces iron oxides and hydroxides rich in active sites that increase adsorption, electrostatic redox reactions, and PFAS immobilization in the soil[22]. Based on this rationale, iron was selected in the present study to introduce these iron oxides and hydroxides, aiming to increase surface functional groups and active sites to enhance PFAS sorption.

Evaluation of the bioaccumulation of PFAS in radish (Raphanus sativus L., variety: cherry belle) grown in soils amended with 2 or 5 wt.% BC was the focus of the present study. Before plant growth, sorbent-amended soils were incubated for 90 d to assess PFAS immobilization, guiding the selection of the most promising materials for the bioaccumulation experiments. This work significantly increases our understanding of the impact of BC sorbents on PFAS immobilization in soil, as well as the suitability of this management strategy for promoting overall food safety.

-

A mixed reference standard solution of 24 native PFAS was purchased from AccuStandard Inc. (Connecticut, USA). An isotopically labeled analog mixture was purchased from Wellington Labs (Canada). A full compound list is provided in Supplementary Table S1. Solvents used included methanol, acetonitrile, and formic acid; all were analytical grade and acquired from Fisher Scientific. Ammonium acetate (ACS reagent grade), and Supelclean ENVI-Carb 120/400 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Hemp seeds (Cannabis sativa L.; 'BaOx' variety) were purchased from Fortuna (Grand Junction, Colorado, USA), and radish (Raphanus sativus L., variety: cherry belle) seeds were purchased from Plantation Products LLC.

Soil was collected from a historical fire-fighting site in Connecticut, USA, with known PFAS contamination (depth between 20–60 cm). The soil from this area was selected because it is contaminated with PFAS from the repeated use of aqueous film-forming foams (AFFFs), a major source of legacy long-chain PFAS compounds in the environment. While PFAS concentrations at this site may be higher than those typically found in agricultural fields, utilizing this soil enabled the testing of materials under conditions that closely represent real PFAS-polluted sites, rather than relying on artificially spiking the contaminants to evaluate the performance of the present treatments. The soil was air-dried and sieved through 2-mm mesh. The fraction that passed through the sieve was collected and stored at 4 °C for subsequent use. The soil type was characterized as a fine sandy loam structure (Supplementary Table S2). The soil was extracted and analyzed as described below, and was found to have a 575 ± 117 ng/g PFAS concentration. PFOS (350 ± 107 ng/g), PFUnA (61.9 ± 2.7 ng/g), and PFNA (43.9 ± 3.3 ng/g) were the analytes at the highest concentration. The lowest concentration detected analytes were PFTeA (0.2 ± 0.1 ng/g), and PFBS (1.0 ± 0.01 ng/g) (Supplementary Table S2). Promix® potting mix growth media without amendment was used as a control.

PFAS analysis

-

Methods for the extraction and analysis of PFAS from soil and radish tissues were performed according to Nason et al.[23]. The mass of dry soil and radish tissues used for the extraction was 4 and 0.1 g, respectively, although lower masses of radish tissues were used when necessary. Before extraction, all the samples were amended with a mixture of isotope-labeled internal standard (listed in Supplementary Table S1) at 1.0 ng/mL in the final extract, and were kept undisturbed overnight. Briefly, the samples were extracted three times with 4 mL of methanol containing 400 mM ammonium acetate. The extract was evaporated under N2 in a 60 ºC water bath for 90 min. Methanol was added to bring the volume to 1 mL; the sample was vortexed and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 min. The extract was cleaned up using 40 ± 5 mg of ENVI-Carb, followed by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 30 min, and filtered through a 0.2 µm regenerated cellulose membrane. The filtered extract was transferred to a polypropylene autosampler vial with a polyethylene cap. The analysis was carried out with a 1290 ultra-performance liquid chromatograph (Agilent) coupled with a SciEx 7500 triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer with negative electrospray ionization mode, and the quantitative software SciEx OS. A Thermo Hypersil Gold C-18 column (100 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.9 µm particles) equipped with an Accucore aQ guard column (10 mm × 2.1 mm, 2.6 μm particles). The mobile phase gradient was 0.1% formic acid in ultra-pure water (A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (B) as detailed in Supplementary Table S3. The calibration range for PFAS was 0.01 to 100 ng/mL. Ratios of peak areas between the IS to native PFAS were determined for the calibration curve and quantified samples. Further details on the method and instrumental parameters are as reported by Nason et al.[23].

To verify the method, control plants (not exposed to PFAS) were analyzed in which no PFAS were detected. In addition, spike recoveries were performed on radish bulbs purchased from a local grocery store. The blank radish tissues were spiked at 1 and 10 ng/mL of the native PFAS standard mixture, extracted, and analyzed as described above. The PFAS recoveries were 75%–125% (Supplementary Fig. S1), which is consistent with the accuracy expected from established analytical methods, with the exception being PFOA (142.90% at a spike of 1 ng/mL), and PFUnA (136.10% at both concentrations).

Preparation of biochar-based sorbents

-

Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) biomass was collected from Lockwood Farm in Hamden, Connecticut (USA). Briefly, hemp seeds were germinated in a greenhouse, and five-week-old seedlings were transplanted into the field. The plants were watered as needed by drip irrigation, and weeds were controlled with plastic mulch. Hemp stems and leaves (about 8 weeks of age) were harvested and oven-dried at 90 °C in a Fisher IsoTemp oven. The dry biomass was homogenized with a mortar and pestle and sieved through a 1 mm mesh, rendering it suitable for BC preparation.

The preparation of BC was conducted in a tube furnace under oxygen-depleted conditions achieved by continuous purging with N2 gas. Briefly, 100 g of the dry ground biomass was placed into a custom-made stainless-steel container, and subjected to pyrolysis at 500, 700, or 800 °C. The temperature program adhered to the specifications outlined in Supplementary Table S4. For the synthesis of iron-fortified BC (FBC), both the iron source and biomass were mixed before pyrolysis: The dry hemp biomass (~100 g) was soaked in 200 mL solution of iron (III) sulfate with continuous agitation for 30 min, and afterwards dried in a Fisher IsoTemp oven at 90 °C. The concentration of iron (III) sulfate was adjusted according to the mass ratio of Fe/biochar to achieve approximately 8–10 wt.% of iron content in the final product. The resulting dry powder underwent the same BC preparation protocol as described above. Overall, six biochar sorbents were produced: BC500, BC700, BC800, FBC500, FBC700, and FBC800, and were stored in the dark until use. Incorporation of iron into BC provided additional PFAS sorption sites.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

-

BC surface functionality, i.e., the presence of surface functional groups like –OH, –COOH, and –C=O, were determined using FTIR (Model, BRUKER, INVENIO-S) with a resolution range of 400–2,800 cm–1. The ground sample was placed on an ATR (attenuated total reflectance) crystal and exposed to a broad spectrum of infrared light. The interferometer splits and recombines the light to create a time-domain signal, i.e., interferogram. Using the Fourier Transform mathematical equation, the interferogram was converted into a conventional IR spectrum (cm–1). Peaks obtained showed specific bond vibrations and final IR spectra were compared with known reference spectra to identify functional groups. Multiple FTIR measurements were taken, but only one representative spectrum was presented in the study.

Specific surface area and pore volume/size

-

Specific surface area (SSA), and pore volume/size of biochar were determined using the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method with a Quantachrome BET analyzer. SSA and pore volume were measured, before and after thermal reactivation of samples, with carbon dioxide gas absorption using an Autosorb iQ-MP (1 Stat.) Viton automated gas sorption analyzer (Model No. 195336). Biochar samples were vacuum dried at a temperature range of 200 °C to remove excess moisture and contaminants for 4 h before assessing the absorption of carbon dioxide at 273 K (–0.15 °C). The amount of CO2 gas adsorbed at different relative pressures (P/P0) was measured, and surface area and pore volume were calculated.

Elemental composition

-

For elemental analysis, oven-dried BC samples were digested by the addition of hydrochloric acid and nitric acid (ratio, 3:1), further diluted to a final volume of 25 mL with deionized water. Calcium (Ca), potassium (K), magnesium (Mg), phosphorus (P), and iron (Fe) were analyzed using inductively coupled plasma—mass spectrometry (ICP-OES, Thermo iCAP Pro XP). For quality control, continuing calibration verification (CCV) was run after a batch of 10 samples showing % recovery of 94.3% to 115%. Certified reference material (CRM) and spiked samples of a known elemental concentration were also run with the samples. Yttrium was used as an internal standard. The injection needle was washed before and after every sample run with a mixture of nitric acid solution.

Cation exchange capacity (CEC) of soil after addition of BC sorbents was determined using the formula given below:

Step 1: cmol (+)/kg = i∑ (mg/g) i × 100 × zi/Atomic wti

where, zi is the ion charge; for Na+, K+ = 1 and for Ca2+, Mg2+ = 2.

Step 2: CEC (cmol (+)/kg) = cmol (+)/kg (Na mg/g) + cmol (+)/kg (Ca mg/g) + cmol (+)/kg (K mg/g) + cmol (+)/kg (Mg mg/g)

where, Na mg/g, Ca mg/g, K mg/g, and Mg mg/g are the amounts calculated from ICP-OES.

PFAS immobilization in soil

-

To guide material selection for the plant study, the sorbents based on their capacity to immobilize PFAS in soil were first screened, rather than selecting materials arbitrarily. PFAS retention was assessed indirectly by measuring leaching over a 7-d period (the less PFAS found in leachates, the higher the PFAS retention or immobilization in soil). Specifically, 4 g aliquots of dry soil were moistened with DI water (65% moisture content), and mixed with one of the BC sorbents at mass ratios of either 2 wt.% or 5 wt.% dry mass in a 50 mL centrifuge tube; soil without BC amendment was used as a control. The soils were vortexed for 30 s, shaken end-over-end on a paint shaker for 15 min, and subsequently incubated at 4 °C for 90 d to simulate environmental conditions that may affect the soil's leaching properties[24,25]. This incubation period was selected based on literature, where Albalasmeh et al. and Alghamdi et al. found significant effects of olive pomace (Olea europaea L.) based biochar on soil infiltration rate in response to different pyrolytic temperatures after 90 d[24,25]. After the incubation period, 40 mL of deionized water (DI) water was added to each tube for the leaching test, and the samples were shaken on a rotary shaker for 7 d, followed by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 20 min. The supernatants were transferred to Eppendorf tubes and centrifuged again at 10,000 rpm for 20 min. The supernatants were collected and analyzed to measure PFAS in these leachates.

The PFAS immobilization was assessed using Eq. (1):

$ \text{%}\mathit{\mathit{\mathrm{\; \mathit{PFAS}\; \mathit{retention\; }\mathit{in\; soil}}}}=\dfrac{\mathrm{\left[\mathit{PFAS}\right]\mathit{_{unamended\; soil}}-\left[\mathit{PFAS}\right]\mathit{_{amended\; soil}}}}{\mathrm{\left[\mathit{PFAS}\right]_{\mathit{unamended\; soil}}}}\times100 $ (1) where, [PFAS]unamended soil and [PFAS]amended soil (µg/L) are the PFAS concentrations in leachate from the unamended soil and the BC-amended soil samples, respectively. Biochar sorbents that showed potential to immobilize PFAS (expressed as % PFAS retention) were selected to evaluate their impact on PFAS accumulation in radish plants (Raphanus sativus L., variety: Cherry Belle) during a 6-week growth period.

Pot experiment

-

The materials BC500 and FBC500 were selected as sorbents to evaluate the impact on PFAS accumulation in radish. Radish (Raphanus sativus L.) was the model plant for the study due to its wide consumption, short growth cycle, and defined root–bulb–shoot structure that can provide a comprehensive assessment of PFAS uptake, translocation, and accumulation. Radish seeds were germinated in Promix® media in a greenhouse. Two-week-old seedlings were transplanted to individual pots containing 200 g of soil (dry mass), either amended with sorbents (2 wt.%), or left unamended. PFAS-exposed plants were grown in field soil contaminated with legacy firefighting foams (described above), and control plants were grown in unamended Promix® media. The soil was moistened to 75% of its water-holding capacity to prevent leaching during cultivation. Five replicate pots were established per treatment. Throughout the growth period, plants were bottom watered as needed. After 4 weeks of treatment, plants from the control and treated groups were harvested, with the shoot and bulb tissues separated for subsequent analysis. Plant biomass and shoot length were also measured. The plant tissues were stored frozen at –20 °C, followed by freeze-drying and homogenizing before PFAS analysis. Radish tissues from the control plants were used to monitor the potential for contamination from the surrounding environment, as well as trace contamination of the growth media. No PFAS was detected in any of the control plant tissues.

PFAS concentrations (ng/g) in soil, radish shoot ([PFAS]shoot), bulb ([PFAS]bulb), and whole plant (shoot + bulb) was used to calculate PFAS bioaccumulation factors (BAF), and translocation factors (TF), as expressed in Eqs (2) and (4). ([PFAS]whole plant) was calculated by taking into consideration PFAS concentrations of shoot and bulb and their corresponding tissue mass.

$ BAF=\dfrac{{\left[PFAS\right]}_{whole\; plant}}{{\left[PFAS\right]}_{Soil}} $ (2) where,

${\left[PFAS\right]}_{Whole\; plant}=\dfrac{{\left[PFAS\right]}_{Shoot}\times {m}_{Shoot}+{\left[PFAS\right]}_{bulb}\times {m}_{bulb}}{{m}_{Shoot}+{m}_{bulb}} $ (3) $ TF=\dfrac{{\left[PFAS\right]}_{Shoot}}{{\left[PFAS\right]}_{Bulb}} $ (4) Data analysis

-

Results for PFAS immobilization in soil are presented as mean values of n = 2. Data for PFAS bioaccumulation in radish are presented as mean ± SE of n = 5, and the significance of differences among different amendments was determined by a one-way ANOVA and Student's t-test. The analysis was carried out using SigmaPlot 16, and Microsoft Excel was used to draw relevant graphs, organize initial data, and conduct primary analysis.

-

The physicochemical properties, nutrient content, and PFAS content of the contaminated field soil were determined (Supplementary Table S2). The soil was a sandy loam with a pH of 5.6 with an initial PFAS concentration of 576 ± 117 ng/g. Of the total 24 PFAS analyzed, 20 compounds were detected, including perfluoroalkyl sulfonic acids (C4−C10-PFSAs), perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids (C4−C11, C13−C14-PFCAs), fluorotelomer sulfonates (6:2, 8:2-FTS), and perfluorooctane sulfonamide (PFOSA). Among the detected PFAS, PFOS was the predominant analyte, comprising up to 60.7% of the total contaminant content, followed by PFUnA (10.8%), PFNA (7.6%), and PFHxS (6.9%). The high PFOS content is indicative of the historical use of aqueous film-forming foams (AFFF) at this site, and aligns well with the literature on PFAS contamination at AFFF-impacted sites. Notably, reported PFOS concentrations vary significantly in the literature, ranging from 0.4−460,000 ng/g, depending on the PFAS-related activities involved[26].

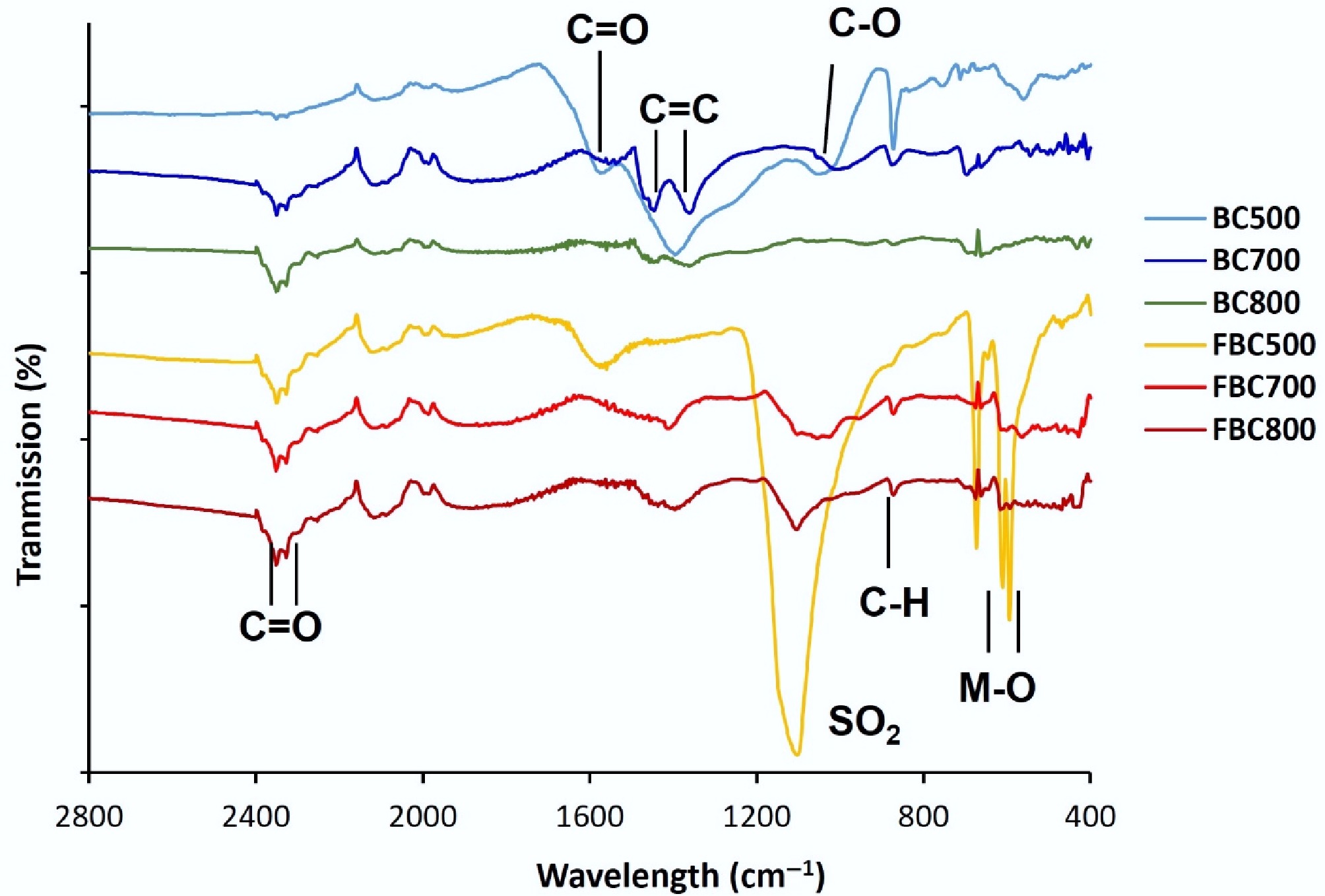

The binding interactions of PFAS in soil to amended sorbents will be a function of the material surface and structural properties. To investigate BC surface functionality, FTIR spectra were obtained (Fig. 1). The BC500 spectra showed several strong vibration signals at 2,400–1,000 cm–1 that can be assigned to C–O, C=O, and C=C groups. This aligns with previous studies identifying oxygen-based functional groups of BC, such as carboxyl, alcohol, and phenol groups[27,28]. With increasing pyrolysis temperatures between 500 and 800 °C, the overall peak intensities in these wavelengths substantially decreased, indicating a loss of surface functional groups and greater condensation of aromatic structures with increasing temperature[29]; these results align with previous studies[30]. A similar trend was observed for the iron-fortified BC materials. Interestingly, these losses correspond to increases in macro-element content in the BC materials with increasing temperatures, including Ca, K, Mg, and P (Table 1). For the iron fortified BC, the Fe concentration was approximately 8.0 wt.%, while the non-fortified material contained approximately 0.03 wt.% of iron.

Figure 1.

FTIR spectra of the biochar-based sorbents at varying pyrolysis temperatures, and with iron fortification.

Table 1. Elemental composition (ICP-MS), and surface properties (FTIR) measured in the biochar-sorbents

Sorbent Element content (wt.%) BET surface area (m2/g) Pore volume (cm3/g) Ca K Mg P Fe CEC (cmol (+)/kg) * BC500 6.2 6.6 0.9 0.8 0.03 555 233 0.054 BC700 7.1 7.3 1.1 0.9 0.03 630 19.3 0.006 BC800 7.3 7.6 1.1 0.9 0.03 652 17.7 0.006 FBC500 4.8 4.7 0.7 0.6 7.8 425 300 0.072 FBC700 7.0 6.3 0.9 0.9 8.0 595 343 0.089 FBC800 7.0 6.8 1.1 0.9 8.1 616 288 0.070 * Reported data is mean value for n = 2. The BET SSA and pore volume substantially decreased from 233–17.7 m2/g, and from 0.054–0.006 cm3/g, respectively, as the pyrolysis temperature increased from 500–800 °C. However, the pore volume showed no further change beyond a certain temperature increase (Table 1). The higher pyrolysis temperature (≥ 700 °C) likely caused structural ordering and collapsing of pores, thereby decreasing SSA and pore volume[31]. In addition, minerals in hemp-derived BC in the present study may form nanoscale particles at higher pyrolysis temperatures, and subsequently block the BC pores; this is supported by the XRD results, where temperature and Fe fortification markedly influenced mineral composition and crystallinity. More information is provided in Supplementary Text S1 and Supplementary Fig. S2. The reduction in surface area could be attributed to deformations, cracks, or blockages in the micropore structure[32]. It is also known that the feedstock source significantly impacts the physicochemical characteristics of BC. Previous reports on BC derived from mineral-rich sources such as manure and rice husk showed similarly low SSA[33,34].

Importantly, iron fortification increased the BC surface area from 300–343 m2/g and pore volume from 0.072–0.089 cm3/g, particularly at FBC500 and FBC700. These changes in surface properties are expected to play an important role in PFAS sorption capacity. Wang et al. reported a significant increase in SSA of softwood shavings-derived biochar from 219 to 698 m2/g at a pyrolysis temperature of 500–600 °C. They attributed this SSA increase to biochar properties becoming more aromatic and less polar, which enhanced the adsorption capacity of biochar[18]. There was a decrease in the SSA (288 m2/g), and pore volume (0.070 cm3/g) when the temperature was increased from 700 to 800 °C. Interestingly, other authors have reported increases in the SSA and porosity with an increase in the pyrolysis temperatures, and attributed this to the degradation of organic substances that can result in the formation of more pores, as well as the generation of bundled channels or channel structures[27,35].

Cation exchange capacity (CEC) was found to increase with increasing temperature from BC500 (555 cmol (+)/kg) to BC800 (652 cmol (+)/kg). The same trend was observed after Fe-fortification of BC, where CEC of FBC500 was 425 cmol (+)/kg, and for FBC800, CEC was 616 ± cmol (+)/kg (Table 1). At high temperatures, there was an apparent increase in CEC, which can be attributed to the property of biochar ash in retaining more inorganic minerals such as K, Ca, Mg, and P from the feedstock and an increase in the total exchangeable cation sites due to the large surface area[36]. Also, there was a decrease of 30.5%, 5.94%, and 5.84% in CEC of iron-fortified biochar amendments FBC500, FBC700, and FBC800, respectively, in the present study as compared to their respective BC amendments. This can be attributed to the presence of Fe coatings, which block negative exchange sites[37]; blocking of the active functional groups responsible for ion exchange and production of C-O-Fe complexes; and alteration in the surface chemistry, which reduces the number of available sites for cation exchange[38].

Effect of sorbent amendments on PFAS immobilization in soil

-

A leachate screening assay was carried out to evaluate the potential of BC materials to immobilize PFAS and retain them in soil, with the goal of selecting the most promising material for follow-up plant studies. PFAS analysis remains a challenge due to the high cost of reagents, availability of specialized instrumentation, and the considerable time required to process each sample, among others[3]. To optimize the use of analytical resources, PFAS measurements in leachates were limited to duplicate samples (n = 2), allowing the prioritization of a robust replication in the subsequent plant tissue analysis (n ≥ 5). Rather than relying on random choice, this leachate screening aided in the selection of BC sorbents based on their PFAS immobilization efficiency, as determined by the percentage reduction of PFAS concentration in leachates Eq. (1).

The concentrations of PFAS in soil leachates are presented in Supplementary Table S5 and Supplementary Fig. S3, which shows the percent PFAS retention in soil amended with biochar and iron-fortified biochar amendments. Analytes below the LOD in unamended soil leachate (PFDS, PFTrA, PFTeA, and PFOSA) were left out of the retention screening assay. It was expected that sorbent amendments would reduce the leachability of most PFAS compounds. Supplementary Fig. S3 presents the PFAS analyzed in the leachates, arranged from shorter to longer carbon-chain lengths for each biochar (BC) treatment, separately for sulfonyl-PFAS (Supplementary Fig. S3a), and carboxylate-PFAS (Supplementary Fig. S3b). Positive bars represent an increase in PFAS retention with amendment addition, while negative bars indicate a decrease in retention (i.e., higher PFAS concentrations detected in the leachate from amended soil). Limited statistical power prevents definitive comparison of biochar sorbent performance. Nonetheless, a clear trend was present for biochars processed at 500 °C, both unmodified (BC500) and Fe-functionalized (FBC500), which overall suggests a higher retention for most PFAS. This suggests their superior potential among the tested materials for PFAS immobilization. Therefore, BC500 and FBC500 were selected for the subsequent plant studies.

Biochar amendments may reduce the mobility/retention of selected PFAS analytes through desorption or changes in soil chemistry[20,32]. The superior efficacy of BC500 and FBC500, as compared to BC700, BC800, FBC700, and FBC800, underscores the critical influence of pyrolysis temperature on BC properties with regard to PFAS interactions. Future studies are needed that focus on understanding and optimizing dosing for overall PFAS immobilization in soil. PFAS analytes interact with carbon-based sorbents primarily through hydrophobic interactions (with a carbon backbone), and through electrostatic interactions with surface functional groups[15]. Generally, BC with greater porosity and specific surface area interact more pronouncedly with PFAS[18]. The substantial decrease in surface area and pore volume of the prepared BCs with increasing temperature from 500 to 800 °C likely restricted PFAS interactions, which could diminish the effectiveness of PFAS immobilization. In addition, the notable decrease in surface functional groups in BC700 and BC800, clearly limited the extent of electrostatic interactions with PFAS compounds, although this chemical change would also enhance carbon backbone hydrophobicity. Although the limited sample size prevents definitive conclusions, the data suggest that BC700 and BC800 could be more effective at immobilizing long-chain PFAS compared to short-chain analytes, despite their lower overall adsorption efficiency due to reduced surface area. Xu et al. reported that, along with hydrophobic interactions between carbon spheres and C-F chain, PFOA can be adsorbed on the carbon backbone by π-CF interactions with fluorine atoms[28]. Interestingly, BC500 exhibited greater immobilization of PFSAs than PFCAs, particularly for short-chain PFSAs, which could be attributed to the greater electrostatic interactions and ligand exchange with the sulfonic functional group, compared to the carboxylic acid groups[37].

The mineral elements in BC, such as Ca2+ and Mg2+ (Table 1), could produce a bridge effect between the surface charges of BC and short-chain anionic PFAS, thereby enhancing sorption potential[15]. The increased crystallinity of the mineral elements at higher temperatures would decrease free cations responsible for this charged bridge effect. Variation in BC interaction with different PFAS compounds has been reported in the literature, with critical factors being pyrolysis conditions (e.g., temperature, activation), and feedstock used for BC[15]. For example, activation with CO2 at 900 °C enhanced the porosity of waste timber BC, thereby increasing PFAS interactions upon soil amendment[20]. Similarly, mesoporous BC exhibited PFBA and PFBS sorption that was six-fold greater than with granular AC[16]. The present study showed that the fortification of BCs with iron enhanced SSA and pore volume, both of which improved material adsorption performance. The Fe/biochar mass ratio of 8 wt.%–10 wt.% iron used in the present study increased the anionic adsorption capacity and reduced pore blockage in biochar. Wu et al. reported that loading of Fe (FeCl3)/BC (derived from switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), and water oak (Quercus nigra) leaf) mass ratio of 5 wt.%–10 wt.% enhanced BC's porosity, pore volume and surface area, subsequently increasing the removal of long chain PFOA from wastewater at a rate of 23.4–42.2 mg/g, as compared to pristine biochar[38]. Furthermore, the presence of iron species in hemp derived BC would have provided active hydrophilic sites for enhanced electrostatic interactions while simultaneously maintaining the hydrophobicity of the BC carbon backbone. Campos-Pereira et al. studied sorption behavior of 12 PFAS compounds onto ferrihydrite using sulfur-based K-edge X-ray absorption near-edge structure spectroscopy (XANES), to demonstrate that charged interactions were critical to PFAS sorption on the sorbent surface[39]. Similarly, Feng et al. observed that interactions among PFSAs on hydrated hematite surface included both physical and chemical pathways, governed by weak hydrogen bonds formed between F (p) and H (s) orbitals and electrostatic interactions[40]. Additionally, it was observed that the BC sorption capacity increased with increasing PFAS C-F chain length. Several studies have reported that complexation with iron species facilitates PFAS remediation[41,42]. PFCAs can form Fe-carboxylate complexes by ligand exchange (Lewis acid/base) with the Fe species/carbon surface, while PFSAs may form outer-sphere complexes with iron species and possibly hydrogen bonds with Fe-coordinated water molecules[43]; this could explain the improvement in PFCAs immobilization with FBC sorbents in the present study. Liu et al. studied PFOA adsorption on Cr-organic frameworks and reported that hydrogen bonding between PFOA and Cr-coordinated water molecule to form Lewis acid/base complexes was about 33% weaker than that of between PFOA and Cr-coordinated unsaturated metal sites[44]. Similarly, Wang et al. observed that hydrophobic/electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonding governed PFAS sorption on nutrient-amended montmorillonite clay[45]. Thus, the synergistic interactions between BC and iron species may have significantly enhanced the PFAS sorption through multiple pathways.

Effect of sorbent amendments on PFAS bioaccumulation in radish

-

Figures 2, 3, and Supplementary Figs S4–S6, show the uptake and bioaccumulation of PFAS in radish shoot, bulb, and whole radish plant (shoot + bulb) cultivated in contaminated soil, both with and without BC500 and FBC500, amendments at 2 wt.% and 5 wt.%. No phytotoxic or phenotypic impact on radish growth in PFAS-contaminated soil was evident as compared to Promix-grown radish. Radish biomass (bulb and whole plant) under BC and FBC treatments showed a significant increase (ANOVA, p ≤ 0.05) by 47.8% and 23.6% as compared to the unamended soil treatment, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S4). Twenty PFAS compounds were detected in radish shoot and bulb tissues (Supplementary Table S6). The PFAS concentration in the radish plant in the unamended controls was 4,175 ± 1,136 ng/g. No PFAS were detected in the control (PFAS uncontaminated) group, suggesting that the uptake of PFAS from contaminated soil by the roots was the sole pathway.

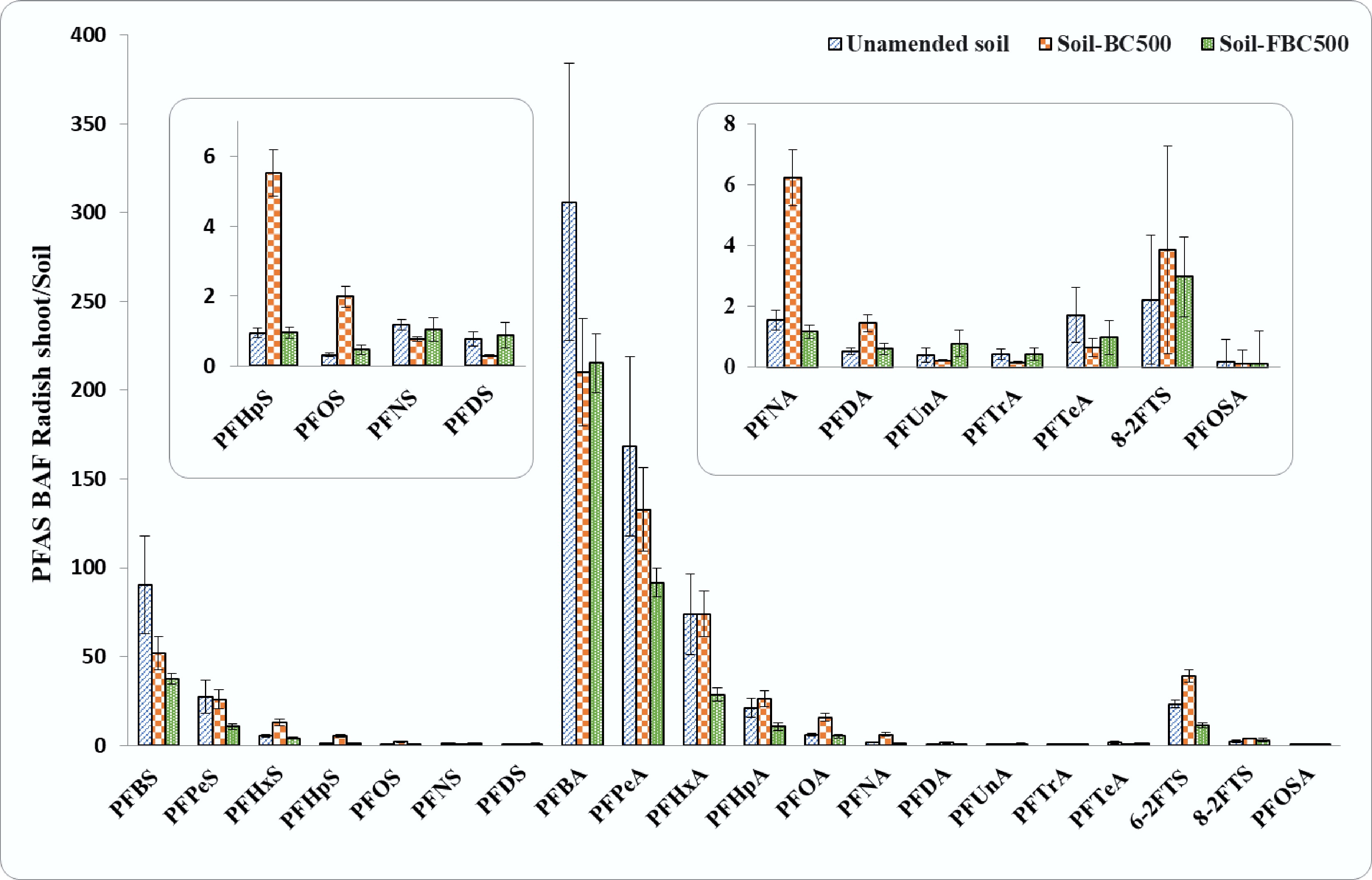

Figure 2.

Bioaccumulation factors (BAF) for PFAS analytes in radish shoot grown in contaminated soil, with and without sorbent amendments. Error bars represent the standard errors for each analyte (n = 5). Inserts represent magnifications of PFAS compounds with concentrations too low to observe in the main graph.

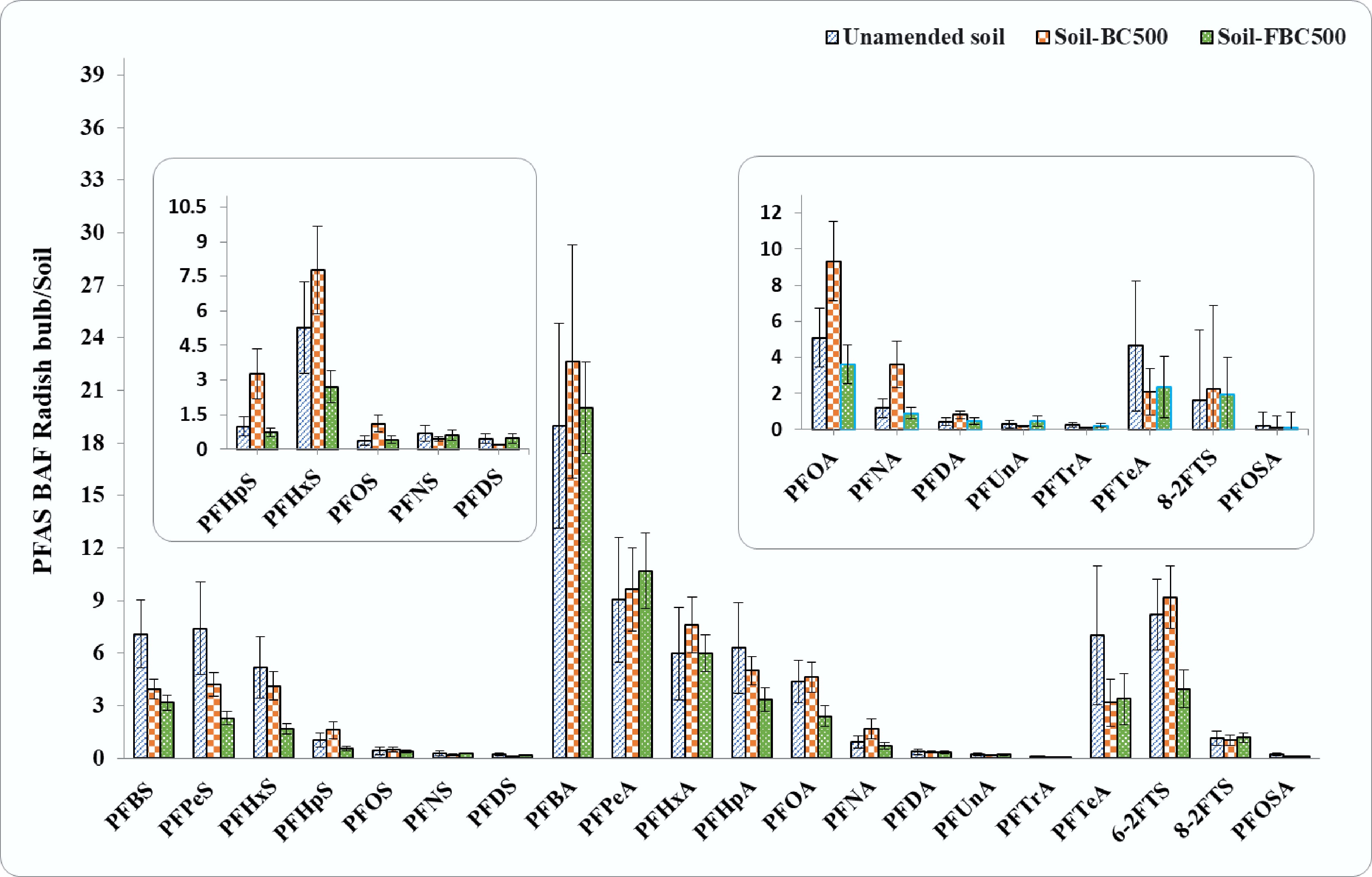

Figure 3.

Bioaccumulation factors (BAF) for PFAS analytes in radish bulb tissues grown in contaminated soil, with and without sorbent amendments. Error bars represent the standard errors for each treatment (n = 5). Inserts represent magnifications of PFAS compounds with concentrations too low to observe in the main graph.

Consistent with the literature[40−42], the extent of PFAS analyte uptake by radish shoot from soil was dependent on PFAS chain length, with reduced accumulation occurring with increasing C-F chain length, following the order of FtS (BAF from 2.2 ± 0.7 for C10 to 23.3 ± 2.1 for C8) > PFSAs (BAF from 0.3 ± 0.1 for C10 to 90 ± 27 for C4) > PFCAs (BAF from 0.5 ± 0.1 for C10 to 306.0 ± 78.0 for C4) (Fig. 2). For example, for carbon chain length C4−C9 PFAS, the BAF of PFCAs was 3.3–13.3 times greater than that of PFSAs. Short-chain PFAS compounds showed notably high BAF in the whole radish plant, with values exceeding 140 for PFBA, whereas long-chain PFAS compounds, such as those of C7−C10-PFSAs, C9−C13-PFCAs, and PFOSA had BAF values less than 1.0 (Fig. 3). BAF values reported in plant tissue above 1.0 indicate PFAS accumulation in the plant relative to the soil concentration. Bulb tissue also showed accumulation of PFAS from soil, dependent on the analyte chain length, with high BAF values for PFBA ranging from 22.7 ± 6.7 to 18.9 ± 5.9, and the lowest for PFTeA (0.1 ± 0.0 to 0.1 ± 0.0).

There was a high bioaccumulation of short-chain PFAS in the whole plant from unamended soil with levels of 421 ± 130 ng/g for PFPeA, 174 ± 46.3 ng/g for PFBA, 200 ± 72.6 ng/g for PFHxS, and 116 ± 36.6 ng/g for PFHxA compared to PFOS (104 ± 33.9 ng/g), even though PFOS was the dominant contaminant in the soil. The edible radish bulb accumulated a higher concentration of PFHxS (27.9 ± 14.7 ng/g), followed by PFPeA (12.7 ± 6.9 ng/g), PFOS (11.8 ± 3.0 ng/g), PFBA (5.5 ± 2.6 ng/g), and PFHxA (4.9 ± 2.9 ng/g) compared to long-chain PFAS analytes (0.024 ± 0.0 to 0.01 ± 0.0 ng/g) (Supplementary Fig. S4). Shorter C-F chain compounds are more hydrophilic and mobile due to their lower molecular weight and reduced sorption to soil, thereby facilitating accumulation by plants[46]. Liu et al. reported that BAF values are a function of plant species, PFAS compounds, and soil conditions. For example, vegetable species showed high BAF values (for shoot vegetables: 6.6–24.3; fruit vegetables: 2.9–6.6; flower vegetables: 1.9–4.2; and root vegetables: 1.8–3.6) compared to cereal crops (0.5–4.1), possibly due to the higher protein and lipid content of vegetables, which have a high affinity for PFAS[47]. These variations overall affect the bioavailability of PFAS compounds and must be considered to design comprehensive strategies for PFAS remediation.

The PFAS concentration in the whole radish plant grown in unamended soil was 4,175 ± 1,136 ng/g. In comparison, soil amended with BC500 resulted in a higher PFAS accumulation of 4,866 ± 764 ng/g in radish, while amendment with iron-fortified biochar (FBC500) reduced the concentration to 2,630 ± 367 ng/g, showing a 45.9% decrease relative to the BC500 treatment, and a 37% decrease relative to the unamended soil. (Supplementary Table S6). BC500 resulted in increased PFAS accumulation in radish plants due to a reduction in polarity, which resulted in fewer sorption sites, high SSA, and hydrophobicity that potentially resulted in PFAS desorption and improved soil conditions, such as better aeration, nutrients, and water retention, that supported enhanced root growth and high uptake of PFAS[52]. There was a decrease in PFAS bioaccumulation in radish plant (shoot + bulb) under FBC500 amendment, showing greater reduction in BAF values compared to BC500 amendment. FBC500 resulted in reduced bioaccumulation of PFHxS, PFHpS, PFOS, PFOA, PFNA, PFDA, 6-2FtS, and 8-2FtS by 47.4% ± 1.9%, 230% ± 1.1%, 194% ± 0.3%, 82.9% ± 2.2%, 203% ± 1.3%, 86.1% ± 0.2%, 46.7% ± 4.7%, and 38.5% ± 0.7%, respectively, in the whole radish plant compared to BC500 amendment. Specifically, in terms of chain length, FBC500 showed a decreasing trend for BAF values in the whole radish plant (shoot + bulb) for PFSAs and PFCAs; that is, bioaccumulation of PFAS analytes decreases with an increase in the PFAS chain length or number of carbon atoms (reduction by 11.4% ± 0.2% to 59.4% ± 2.8% and 7.8% ± 0.1% to 29.5% ± 15.8% for PFSAs- and PFCAs compounds, respectively). The minimal changes in bioavailability of some long-chain PFAS (such as C8−C10-PFSAs and C10−C13-PFCAs) were likely due to the low mobility and high hydrophobicity of these particular analytes.

PFAS concentration in the radish bulb treated with soil amended with BC500 was slightly higher (724 ± 135 ng/g) than in the unamended soil (705 ± 266 ng/g), whereas iron-fortified biochar (FBC500) resulted in a 25.7% reduction in PFAS bioaccumulation in the bulb (524 ± 103 ng/g) (Supplementary Table S6). The decrease in bioaccumulation can be attributed to a dilution effect, where more radish biomass results in more distribution of PFAS in tissues. Considering the edible bulb tissue, the bioaccumulation of PFAS analytes across the different treatments was similar to the whole plant data, with the BAF values showing notable decreases for short-chain PFASs, particularly with FBC500 (Fig. 3). For example, the PFHxS concentration in the bulb showed a 20% reduction with BC500 (166 ± 33 ng/g), which further reduced to 67.7% with iron fortified FBC500 (67 ± 12 ng/g), as compared to un-amended soil (208 ± 70 ng/g). The same trend was observed for PFPeS in the radish bulb, with a concentration of 22.9 ± 8.1 ng/g for the unamended soil, and a reduction of 43.2% with BC500 (13 ± 2.1 ng/g), and 68.9% with FBC500 (7.1 ± 1.1 ng/g). For PFHpA, the concentration was reduced by 20.3% with BC500 (17.2 ± 2.5 ng/g), and by 46.7% with FBC500 (11.5 ± 2.2 ng/g). Similarly, a significant 51.3% decrease in the bioaccumulation of the 6:2 FtS analyte in the bulb was also observed with FBC500 (22.4 ± 6.0 ng/g), as compared to the unamended soil (46 ± 11 ng/g).

Conversely, the PFCAs accumulated in the radish bulb with no consistent trends, except for the reduced BCF values for PFHpA and PFOA with FBC500 amendment. Comparing the different tissues, PFAS compounds showed a greater accumulation in the shoot tissues than in the bulb, resulting in translocation factors (TF) exceeding 1.0 for most analytes across all treatments (Supplementary Fig. S5). Notably, higher TF values (shoot to bulb ratio) were observed for certain short-chain PFAS compared to other compounds, which aligned with their corresponding BAF values. For instance, TF values for PFBS were 12.8 ± 5.2, 13.1 ± 2.9, and 11.8 ± 1.9 in unamended soil, biochar (BC) amended soil, and Fe-fortified BC amended soil, respectively. Similarly, PFPeS showed TF values of 3.7 ± 1.8, 6.2 ± 1.6, and 4.7 ± 1.0; PFBA had values of 16.1 ± 6.4, 9.3 ± 3.0, and 10.8 ± 1.6; PFPeA showed 18.6 ± 9.2, 13.8 ± 4.1, and 8.6 ± 1.9; PFHxA showed 12.4 ± 6.6, 9.7 ± 2.5, and 4.8 ± 0.9; and PFHpA values were 3.4 ± 1.6, 5.2 ± 1.2, and 3.2 ± 0.8 across those same soil treatments, respectively. PFAS compounds present in soil can dissolve in the pore water, subsequently be absorbed by root tissues, and eventually be distributed to other parts of the plant via the xylem or phloem[47]. Additional information on TF is presented in Supplementary Text S2[48−51]. Overall, the present study shows that Fe fortified BC significantly (one way ANOVA, p ≤ 0.05) reduced the uptake of most short-chain PFAS analytes by 27.2%–82.9%, 19.3%–65.0%, and 26.7%–78.9%, and long-chain PFAS analytes by 30.9%–81.4%, 21.4%–57.6%, and 28.1%–76.2% in radish shoot, bulb, and whole plant relative to BC, respectively. These changes may be attributed to the presence of Fe, which improved sorption capacity, electrostatic and ligand exchange interactions with anionic PFAS molecules, surface polarity, and pore structure, as well as improved chemical and electrostatic binding and provided high structural stability[38,52].

BC has been utilized as a soil amendment in agricultural practices to enhance soil structure and properties, including porosity and water holding capacity; importantly, this amendment effectively immobilized a range of PFAS analytes on the BC structure via hydrophobic interactions and electrostatic interactions, inhibiting their uptake and translocation[51,53]. Notably, few studies have investigated the uptake of PFAS in plants after soil amendment with biochar. Bräunig et al. investigated AC and RemBind and reported that RemBind at 15.0% in soil decreased the accumulation factor for PFCAs and PFSAs by 2 and 3 log units in timothy grass, respectively[46]. However, this amendment also reduced plant growth by up to 51% to 7%, possibly due to strong binding of nutrients in soils[46]. Zhang & Liang observed increased PFAS uptake in timothy-grass (Phleum pretense) cultivated in soil amended with a commercial BC (2%) and other carbon-based sorbents (e.g., 0.2% of RemBind and AC)[36]. Higher doses of RemBind and AC (≥ 2%) effectively reduced PFAS uptake due to their stronger analyte interactions, compared to BC. Melo et al. investigated the impacts of organoclay amendment on PFAS binding, as well as on the growth, reproduction and survival of earthworms (Eisenia fetida), and on plant growth (oat—Avena sativa and turnip—Brassica rapa L. silvestris). Although PFAS accumulation was not measured, the authors reported that both plant species treated with soil containing adsorptive organoclay (Intraplex A®) and PFAS yielded less fresh and dry shoot biomass as compared to PFAS alone[54]. Li et al. reported a 90.5% decrease in PFAS uptake (e.g., short-chain PFMOAA) in lettuce (Lactuca sativa) shoots and 30.7%–86.3% in soil pore-water under commercial compost amendments, highlighting the high risk for these compounds in edible vegetables[55]. In the current study, Fe fortification (FBC500) and low pyrolysis temperature were shown to be promising factors in PFAS immobilization in soil, which resulted in low bioaccumulation of PFASs analytes in radish bulbs.

-

The present findings demonstrate the importance of pyrolysis temperature on BC structure and surface properties, which subsequently mediate PFAS interactions and stabilization in soil. Importantly, incorporating iron with BC was shown to increase the immobilization efficacy in soil. Almost all the contamination in the studied soil was due to PFOS, which was not expected to degrade at all, but there are likely precursor PFAS present in the soil that might degrade (including the FTSs that were detected). Based on the overall results, we believe that iron fortification of hemp-derived biochar can: (i) increase the positively charged functional groups, thereby attracting anionic PFAS molecules; (ii) enhance surface reactivity, leading to increased surface porosity and the generation of new sorption areas; (iii) increase polarity, which allows instantaneously stronger and irreversible binding of Fe with PFAS hydrophobic and hydrophilic parts; and (iv) lower the freely dissolved PFAS fraction in soil pore water, thereby reducing PFAS uptake into plants (Supplementary Fig. S7). There was a significant reduction in PFAS mobility in the soil and low PFAS bioaccumulation in radish due to enhanced surface area and pore volume of biochar. There was an increase in CEC and nutrients like Na, Mg, K, and Ca, which competed with PFAS for binding sites, thereby reducing soil leaching. Changes in translocation factors of PFAS in radish were reported which could be due to biochar's capability of shifting the rhizosphere or in-planta microbial community in a way that impacts transfer and/or degradation of the more mobile or degradable analytes. It is also possible that the change can be due to the PFAS retention in the soil, which subsequently altered the fraction available for translocation.

-

This study underscores the critical need for controlling PFAS contamination in soil due to its potential for leaching into the surrounding environment over time, and for accumulation by agricultural crops, thereby posing a threat to both environmental and human health. While the application of BC as a soil amendment has shown promise in reducing PFAS bioaccumulation, overall efficacy is heavily dependent on synthesis conditions and functionalization. However, under certain conditions, BC amendments can increase bioaccumulation in plants, highlighting the importance of understanding the governing mechanisms of interaction at the molecular scale. We anticipate that Fe was highly stable in the biochar matrix. The addition of Fe could facilitate biochar recovery magnetically; however, such a strategy would be difficult and expensive on a field scale. The intent of our strategy was to reduce PFAS bioavailability and risk of transfer to food crops over a single or multiple growing seasons. Although the positive impacts of iron-modified BC on reducing PFAS bioavailability are significant, BC can influence the activities of the microbial community, leaving several questions unanswered.

Future work

-

Several aspects remain unexplored and unanswered in the current study. We did see an increase in the PFAS % retention in the soil when biochar was added, so this would be an interesting topic for future research with high resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), and the total oxidizable precursor (TOP) assay, though significant investigation of precursors was beyond the scope of the present study. In future, we plan to further investigate the influence of PFAS sorption in soil and radish on the microbial communities, and the possible mechanisms of biochar in changing the PFAS translocation factors inside radish. We are also planning to comprehensively assess the molecular-level characterization and comparison of biochar properties before and after PFAS treatment and to elucidate the functional groups and chemical bonds involved in FBC-PFAS interactions. The impact of biochar iron fortification on the Fe mineral phase of soil, its long-term performance, and possible catalyzation of some reactions for PFAS degradation is one of the future works being envisaged. In addition to the BET analysis, more characterization and distribution of biochar pore size will be performed in the future, as would further mechanistic studies involving FBC-PFAS interactions, identification of distinct interactions (e.g., adsorption, complexation, and electrostatic attraction), and the relative contributions of each mechanism. These types of studies raise the need for further investigation with different biochar feedstocks; Fe loading methods under different pyrolysis conditions to evaluate long-term field performance and assess effectiveness across a broader PFAS spectrum. Further investigations are warranted to optimize dosing regimens and iron fortification strategies for maximum PFAS retention. In addition, the role of soil type and PFAS contamination extent, and tracking and estimation of transformation products must be explored. Additional studies are also needed to evaluate biochar performance over a broader range of PFAS contamination levels in the environment. Last, and perhaps most importantly, the conditions under which the immobilized PFAS may be re-mobilized and made bio-available for plant uptake must be evaluated. Such studies will provide critical insight into the sustainable use of modified biochars to promote food safety and agricultural productivity.

The authors acknowledge Dr. Joseph J. Pignatello and Dr. Zhengyang Wang for their assistance with biochar preparation and BET analysis, Dr. Itamar Shabtai for his assistance with FTIR analysis, Shannon Pociu, Raymond Frigon from Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection, Richard J. Desrosiers, and Michael Lambert from GZA GeoEnvironmental for their assistance for soil collection, and CAES greenhouse coordinator Joseph Liquori. The authors also acknowledge US HHS FDA award 5U19FD007094 for funding support.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/ebp-0025-0010.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: all authors; material preparation, data collection and analysis: Bui TH, Zuverza-Mena N, Nason SL, Jones JP, Kaur M; writing the first draft of the manuscript: Bui TH, draft editing: Kaur M. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable requests.

-

This project was funded by the US HHS FDA award 5U19FD007094.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Biochar (BC) produced at 500 °C resulted in the highest surface area for retaining PFAS in soil.

Larger PFAS had higher bioaccumulation in radish shoots than in bulb tissues.

Iron-fortified BC in soil lowered PFAS bioaccumulation in radish bulbs.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Trung Huu Bui, Mandeep Kaur

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - Supplementary Table S1 Twenty-four native and isotopically labeled PFSA compounds used for analyzing PFAS.

- Supplementary Table S2 Soil properties and PFAS concentration.

- Supplementary Table S3 LC solvent gradient conditions.

- Supplementary Table S4 Temperature conditions for preparing biochar from hemp biomass.

- Supplementary Table S5 PFAS concentrations in un-amended soil leachate.

- Supplementary Table S6 PFAS concentrations found in radish shoot and bulb along different amendments.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Recovery tests of PFAS from radish sample (bulbs) spiked at 1 and 10 ng/g. Error bars represent the standard errors for each treatment (n = 3).

- Supplementary Fig. S2 XRD spectra of the prepared BC sorbents with and without iron fortification at varying pyrolysis temperatures.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Screening data for material selection in plant studies. Graphs show the percent retention of (a) sulfonyl-PFAS and (b) carboxylate-PFAS in soils amended with biochar (BC) sorbent materials processed at different temperatures (500, 700 or 800 °C) alone or Fe-fortified (F).

- Supplementary Fig. S4 Wet biomass of (a) whole plant (whole radish plant) and (b) bulb grown in contaminated soil without and with BC amendments.

- Supplementary Fig. S5 Bioaccumulation factors (BAF) for each PFAS compound in the whole plant grown in contaminated soil with and without sorbent amendments. Error bars represent the standard errors for each treatment (n = 5). Inserts represent magnifications of PFAS compounds with concentrations too low to observe in the main graph.

- Supplementary Fig. S6 Shoot/bulb translocation factors (TF) for each PFAS compound in the whole radish plant grown in contaminated soil without and with sorbent amendments. Error bars represent the standard errors for each treatment (n = 5).

- Supplementary Fig. S7 Schematic representation of key differences between iron-fortified hemp-derived biochar which resulted in reduced leaching and uptake of PFAS in comparison with the pristine biochar.

- Supplementary Text S1 Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR).

- Supplementary Text S2 Translocation factor (TF).

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Bui TH, Kaur M, Zuverza-Mena N, Nason SL, Dimkpa CO, et al. 2025. Iron-fortified hemp-derived biochar reduces per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances bioaccumulation in radish (Raphanus sativus L.). Environmental and Biogeochemical Processes 1: e010 doi: 10.48130/ebp-0025-0010

Iron-fortified hemp-derived biochar reduces per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances bioaccumulation in radish (Raphanus sativus L.)

- Received: 22 July 2025

- Revised: 23 September 2025

- Accepted: 31 October 2025

- Published online: 27 November 2025

Abstract: Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in soil are a global concern because of their persistence and adverse effects on environmental health and food safety. Biochar (BC) is a cost-effective sorbent that can immobilize PFAS in soil, potentially reducing bioavailability to food crops. This study examined the capability of hemp-derived BC to immobilize PFAS in a field soil contaminated with legacy firefighting foams. The soil contained a total PFAS concentration of 576 ± 117 ng/g, with a notably high PFOS concentration of 350 ± 107 ng/g. BC produced at 500–800 °C and fortified with iron (8 wt.%) was incorporated into soil at 2 wt.% or 5 wt.%, and incubated for 90 d to examine impacts on PFAS bioaccumulation in a food crop (radish; Raphanus sativus L.). BC produced at 500 °C had the highest surface area (232.90 m2/g) and demonstrated superior performance in retaining PFAS in soil. Incorporation of iron into BC resulted in the generation of iron oxide/hydroxide sorption sites. PFAS accumulation in radish plants (shoot + bulb) was reduced by 45.9% when grown in soil amended with iron-fortified BC produced at 500 °C, as compared to unamended soil. Importantly, radish bulb showed 25.7% less PFAS bioaccumulation, with notable efficacy for short-chain sulfonic acids (26.9%–63.9%), and carboxylic acids (29.5%–56.8%). Collectively, these findings underscore the potential of BC, particularly when fortified with iron, to mitigate the risks of PFAS contamination in agricultural soils and promote food safety.

-

Key words:

- Biochar /

- Iron fortification /

- PFAS /

- Hemp /

- Radish /

- Bioaccumulation /

- Food safety /

- Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry