-

Perfluorinated compounds (PFCs) are a class of linear or branched fluorinated hydrocarbons, with perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) being two typical representatives[1]. PFCs exhibit excellent surface activity, high chemical stability, and hydrophobic/oleophobic properties. These compounds are widely used as surfactants and protective agents in various industries, including textiles, packaging, agriculture, electroplating, and firefighting[2−4]. Throughout the entire life cycle of these products, from manufacturing to disposal, PFCs continuously escape into the environment[5]. They migrate through various pathways and accumulate in biological organisms[6]. In May 2009, the United Nations Environment Programme officially listed PFOS and its salts as persistent organic pollutants. PFCs pose hepatotoxicity, immunotoxicity, and reproductive toxicity, representing serious potential hazards to ecosystems and human health as emerging environmental contaminants[7,8]. There is an urgent need to develop rapid and effective remediation technologies for these compounds.

PFCs can be degraded by oxidative radicals (SO4•− and •OH) and reductive radicals (O2•− and alcohol radicals)[9−13]. Advanced oxidation technologies based on persulfate (PS) or hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) generate highly reactive SO4•− and •OH, effectively degrading PFCs[9,10,14]. However, these reactions require extreme conditions such as high oxidant concentrations and elevated temperatures[9,10]. For example, Shannon et al. degraded 89% of PFOA within 120 min using 1 M H2O2 and 0.5 mM Fe3+[10]. Lee et al. degraded most PFOA in 4–6 h at 90 °C via microwave-assisted thermal activation of PS (50 mM)[9]. Liu et al. achieved 35%–95% defluorination of PFCs in 40 min at 120 °C using base-activated PS, where •OH predominates under alkaline conditions[14]. UV/Fe3+ and electrocatalysis are commonly used for the defluorination of PFOA, but they require significant energy input[15−17]. For example, UV/Fe3+ achieves better defluorination efficiency at 185 nm wavelength[16]. PFOA can also undergo reductive defluorination degradation. Bai et al. found that O2•− could degrade PFOA, but the O2•− reduction capacity is weak, and the PFOA degradation efficiency is limited[11]. Recent research has found that alcohol radicals can effectively degrade PFOA[13]. In recent years, advanced reduction technologies utilizing hydrated electrons (eaq−) have been widely applied for PFC degradation, significantly outperforming both advanced oxidation and conventional reduction methods. Photoactive substances such as sulfite, iodide ions, and indole derivatives generate eaq− under UV irradiation[12,18]. However, the generation of eaq− relies on photosensitizers, which are often costly. Additionally, post-reaction byproducts, such as sulfite, may persist, posing secondary treatment challenges.

The carbon dioxide anion radical (CO2•−), as a strongly reductive radical, has attracted significant attention in recent years for its application in degrading organic pollutants[19]. The generation of CO2•− employs low-cost small-molecule acids (e.g., formic acid [FA], acetic acid) as precursors, with CO2 as the sole reaction byproduct, ensuring both cost-effectiveness and environmental sustainability[20]. Generated primarily by photocatalytic, electrochemical, and radiochemical methods, CO2•− exhibits a high reduction potential of −1.9 V, facilitating efficient degradation of various recalcitrant organic contaminants such as chlorinated compounds and nitroaromatics[20−22]. Liu et al. established a UV/TiO2/formate system to generate CO2•−, achieving high-efficiency dehalogenation and degradation of trichloroacetic acid through single-electron transfer reactions[20]. Ding et al. found that CO2•−-based advanced reduction processes can degrade halogenated antibiotics (including chloramphenicol, thiamphenicol, diclofenac, triclosan, and ciprofloxacin) with exceptional dehalogenation efficiency (> 75%)[22]. However, research on CO2•−-mediated degradation of PFCs remains scarcely investigated, and the underlying mechanisms are still unclear.

Based on this, the present study focuses on the defluorination mechanism of PFOA by reductive radicals in the UV/PS/FA system. The research encompasses several critical aspects, including the comparative analysis of PFOA defluorination across various redox systems. It aims to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the defluorination of PFOA in the UV/PS/FA system. Additionally, the study will investigate the influence of various factors, including PS and FA concentrations, pH levels, and the presence of coexisting anions and organic compounds, on the defluorination of PFOA. These findings provide new perspectives for the efficient defluorination of perfluorinated compounds.

-

PFOA (C7F15COOH, 97%) and methyl viologen were purchased from Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). 5,5-Dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO, 98%) was supplied by Dojindo Molecular Technologies (Shanghai, China). FA (HCOOH, 99%), PS (Na2S2O8, 98%), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 97%), sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 98%), phosphoric acid (H3PO4, 99.5%), and potassium dichromate (K2Cr2O7, 99%) were obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Sodium nitrate (NaNO3, 99%), sodium nitrite (NaNO2, 99%), sodium sulfate (Na2SO4, 99.5%), and sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3, 99.5%) were supplied by Nanjing Chemical Reagents Co., Ltd (Nanjing, China). Methanol (MeOH, HPLC grade) was obtained from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). Deionized water was used for all experiments (Milli-Q, Millipore, resistivity of 18.2 MΩ·cm−1).

Experimental procedure

-

The photodegradation experiments were conducted in a photochemical reactor (Model BXU116, 220 V) equipped with a precision temperature control system. The reactor featured a double-layer quartz-jacketed structure, with a 20 W low-pressure mercury lamp (wavelength 254 nm, calibrated irradiance density 8.5 mW·cm−2) fixed at the center of the inner jacket. The outer jacket housed the 50 mL reaction solution. Appropriate volumes of PFOA, FA, and PS mother solution were sequentially added to the bottle to achieve the optimal reactant concentration. Anaerobic conditions were achieved by deoxygenating the solution with high-purity nitrogen gas (99.999%), bubbling for 0.5 h (gas flow rate 1.5 L·min−1), followed by sealing the reaction tube with a butyl rubber stopper. Dissolved oxygen (DO) concentration was monitored in real-time using a dissolved oxygen meter (HACH HQ30D), maintaining DO < 0.1 mg·L−1. During the reaction, a magnetic stirrer (800 rpm) ensured uniform light exposure and prevented localized overheating. Temperature was maintained at 20.0 ± 0.5 °C using a circulating cooling-water system. For timed sampling, 1 mL aliquots were collected using a gas-tight syringe piercing through the rubber stopper. All experiments included dark and blank controls (covered with aluminum foil), and data represent the mean values from triplicate tests.

Analytical methods

-

PS concentrations were quantified by UV–visible spectrophotometry (UV-2700, Shimadzu, Japan), while DO levels were measured using a calibrated portable DO meter (Seven2Go Pro S9, Mettler Toledo, Switzerland). Solution pH was monitored with a Thermo Orion 5-Star pH/Ion meter (USA) coupled with a Thermo 911600 pH electrode. For radical detection, DMPO (100 mM) served as the spin-trapping agent, and the generated reactive species in the UV/PS/FA system were characterized by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy (E500-9.5/12, Bruker, Germany) under X-band (9.85 GHz) with 1.0 G modulation amplitude.

The fluoride ion (F−) concentration is measured using a fluoride-selective electrode. The primary instrument is the Leici PXSJ-270F ion meter fitted with a PF-1-01 fluoride electrode (detection limit: 10−6 mol·L−1). Measurements are performed at room temperature and quantified via the external standard method. A calibration curve is generated by gradient dilution of NaF standard solutions (0.1–100 mM), yielding a linear range of 0.1–50 mM (R2 > 0.99). For sample preparation, 2 mL of quenched reaction solution is combined with an equal volume of total ionic strength adjustment buffer (TISAB) composed of 0.5 M KNO3, 0.1 M sodium citrate, and 1% HNO3 (pH = 5.0) to counteract interference from competing ions. During analysis, samples are stirred at 300 rpm under constant magnetic stirring. The defluorination efficiency of PFOA is defined as the ratio of F− released during degradation to the initial fluorine content in PFOA, calculated using the formula:

${\rm{ PFOA\; defluorination}}\; ({\text{%}}) = \dfrac{\left[{\text{F}}^{-}\right]}{\left[\text{PFOA}\right]\times{\rm n}} \times 100{{\text{%}}} $ where, [F−] represents cumulative fluoride ions measured and [PFOA] denotes initial PFOA concentration, n represents the number of fluorine atoms in a PFOA molecule, where n = 15 in this study.

-

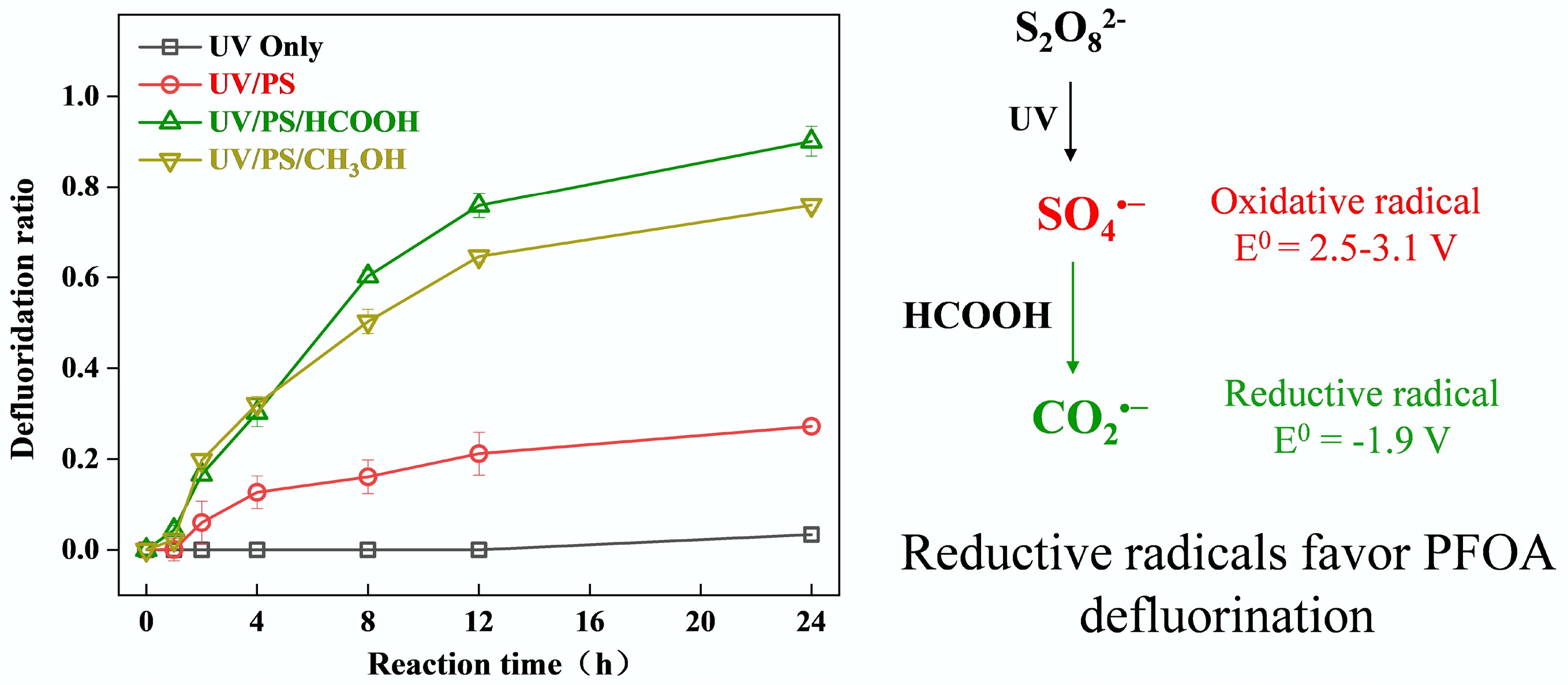

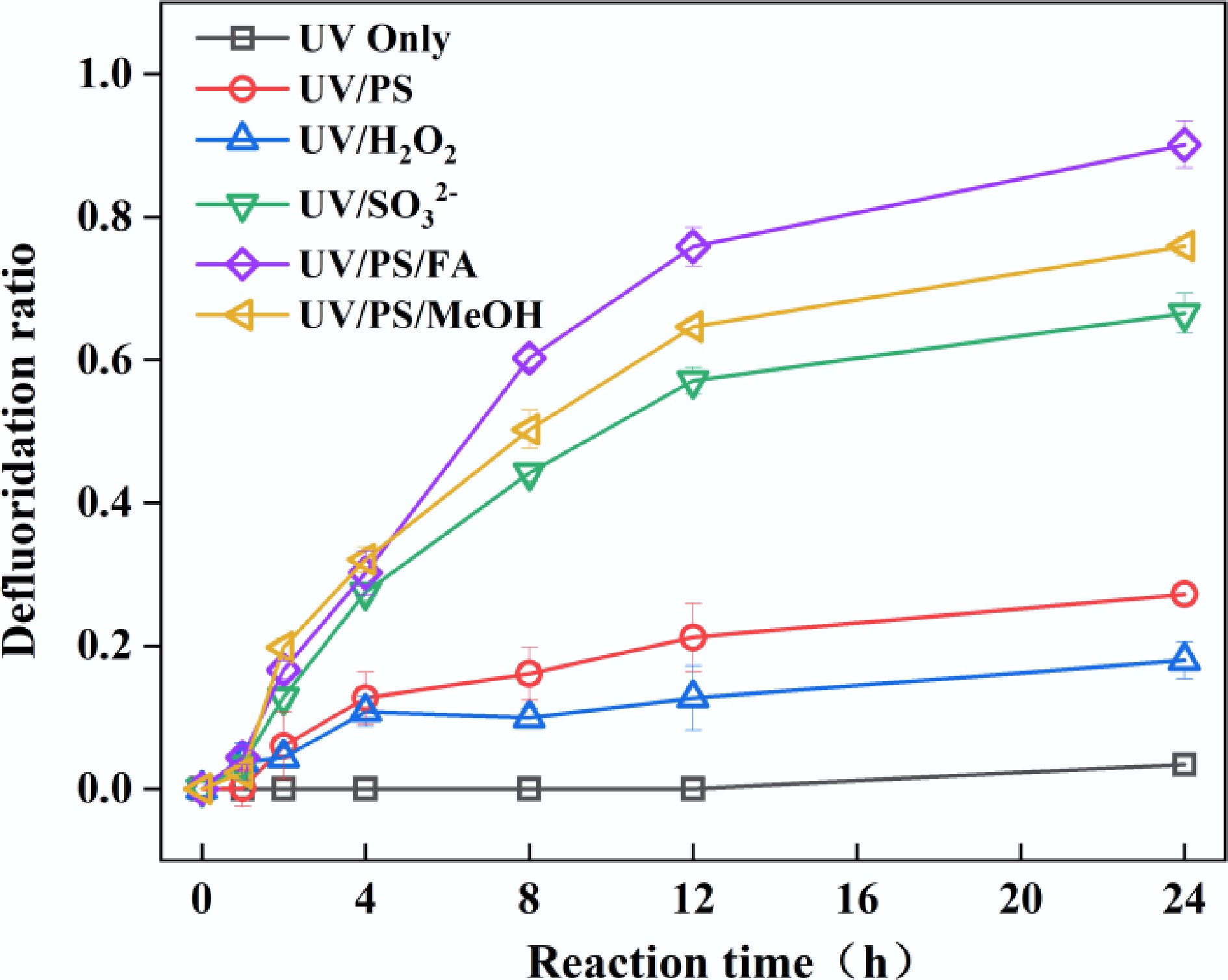

PFOA poses a significant challenge in water pollution control due to the high dissociation energy of its C–F bonds and environmental persistence, making the development of efficient defluorination methods imperative. Although ultraviolet activation technologies are widely used for the degradation of aquatic pollutants, conventional UV-254 irradiation cannot directly cleave PFOA's C–F bonds due to insufficient energy[23]. Recent studies demonstrate that UV-coupled reductive/oxidative systems can effectively degrade perfluorinated compounds[12,24,25]. This study compares the defluorination efficiencies of three UV-activated systems UV/SO32−, UV/PS, and UV/H2O2 (Fig. 1). UV/SO32− achieved a higher defluorination efficiency for PFOA (67% at 24 h), attributed to strongly reductive eaq− (E0 = −2.9 V) that directly attack perfluorinated carbon chains via electron transfer[26]. Oxidative systems showed lower efficiencies: UV/PS (27%) and UV/H2O2 (18%), where SO4•− (E0 = 2.5–3.1 V) and •OH (E0 = 2.8 V) primarily target PFOA's carboxyl groups rather than C–F bonds[27]. This divergence originates from PFOA's molecular properties: fluorine atoms exert a strong electron-withdrawing effect that drastically reduces electron density along the carbon chain, rendering PFOA more susceptible to accepting electrons for reductive degradation than to oxidative attack. These findings showed that reductive systems exhibit an inherent advantage in cleaving C–F bonds.

Figure 1.

Defluorination of PFOA in UV, UV/PS, UV/ H2O2, UV/SO32−, UV/PS/FA, and UV/PS/MeOH systems. Reaction conditions: PFOA = 20 µM, PS = 5 mM, H2O2 = 5 mM, SO32− = 10 mM, FA = 2 mM, MeOH = 2 mM, initial pH of 2.5, anaerobic environment for UV/SO32−, UV/PS/FA and UV/PS/MeOH systems, aerobic environment for the rest of the systems.

$ \mathrm{S}_{ \mathrm{2}} \mathrm{O}_{ \mathrm{8}}^{ {2-}} + \mathit{h\nu } \to \mathrm{{2SO}_{ \mathrm{4}}}^{ {{\text•}-}} $ (1) $ {\mathrm{SO}_{ \mathrm{4}}}^{ {{\text•}-}}+ {\rm H}_{{2}} {\rm O} \to {\text {•OH}}+{\rm SO}_{ \mathrm{4}}^{ {2-}} +\mathrm{H}^{ +} $ (2) $ \mathrm{H}_{ \mathrm{2}} \mathrm{O}_{ \mathrm{2}} + \mathit{h\nu }\to2{\text{•OH}} $ (3) $ \mathrm{SO}_{ \mathrm{3}}^{{2-}} + \mathit{h\nu } \to{\mathrm{SO}_{{3}}}^{ {{\text •}-}} + \mathrm{e}_{ \mathrm{aq}}^{{-}} $ (4) Previous studies have demonstrated that introducing small-molecule organic compounds into oxidative systems can generate reductive radicals by reacting with oxidative radicals, thereby significantly enhancing the reductive degradation of pollutants[21,28,29]. Building on this foundation, this study systematically investigated the enhancing effects of FA and MeOH as organic additives on PFOA defluorination in UV/PS systems. The UV/PS/FA and UV/PS/MeOH systems achieved defluorination efficiencies of 89% and 76%, respectively, after 24 h of reaction. The underlying mechanism involves three critical steps: (1) SO4•− generated from PS photolysis reacts with H2O to form •OH, yet both radicals exhibit limited efficiency in directly cleaving C–F bonds; (2) Added FA/MeOH are preferentially oxidized by SO4•−/•OH, transforming into highly reductive CO2•− (E0 = −1.9 V vs NHE) and •CH2OH (E0 = −1.18 V vs NHE), respectively[30,31]; (3) These secondary radicals selectively attack the C–F in PFOA via single-electron transfer, initiating a stepwise defluorination chain reaction. In this study, the defluorination efficiency of PFOA in UV/PS/FA is higher than that in the UV/SO32− system under acidic conditions. This phenomenon may be attributed to the reaction between eaq− and hydrogen ions under acidic conditions, which generates hydrogen atoms[32]. Notably, CO2•− exhibits superior C–F bond cleavage capability compared to •CH2OH due to its more negative reduction potential, which fundamentally explains the 13% higher efficiency of the UV/PS/FA system. This work confirms that precisely regulating radical transformation pathways (SO4•−→ CO2•−) can overcome limitations of traditional oxidative systems for PFOA treatment. With 89% defluorination efficiency and robust operational stability, the UV/PS/FA system emerges as the most promising technology combination for engineering applications.

$ {\mathrm{SO}_{ \mathrm{4}}}^{{{\text •}-}}+ \mathrm{HCOO}^{ \mathrm{-}}\to {\mathrm{CO}_{ \mathrm{2}}}^{ {{\text •}-}}+ \mathrm{SO}_{ \mathrm{4}}^{ \mathrm{2-}}+ \mathrm{H}^{+} $ (5) $ \mathrm{{\text •}OH}+{\rm{HCOO}}^{ \mathrm{-}}\to {\mathrm{CO}_{ \mathrm{2}}}^{ {{\text •}-}} +\mathrm{H}_{ \mathrm{2}} \mathrm{O} $ (6) $\rm {SO_4}^{{\text •}-} + CH_3OH \to {\text •}CH_2OH + SO_4^{2-} + H^+$ (7) $\rm {\text •}OH + CH_3OH \to {\text •}CH_2OH + H_2O$ (8) Identification of reactive radicals

-

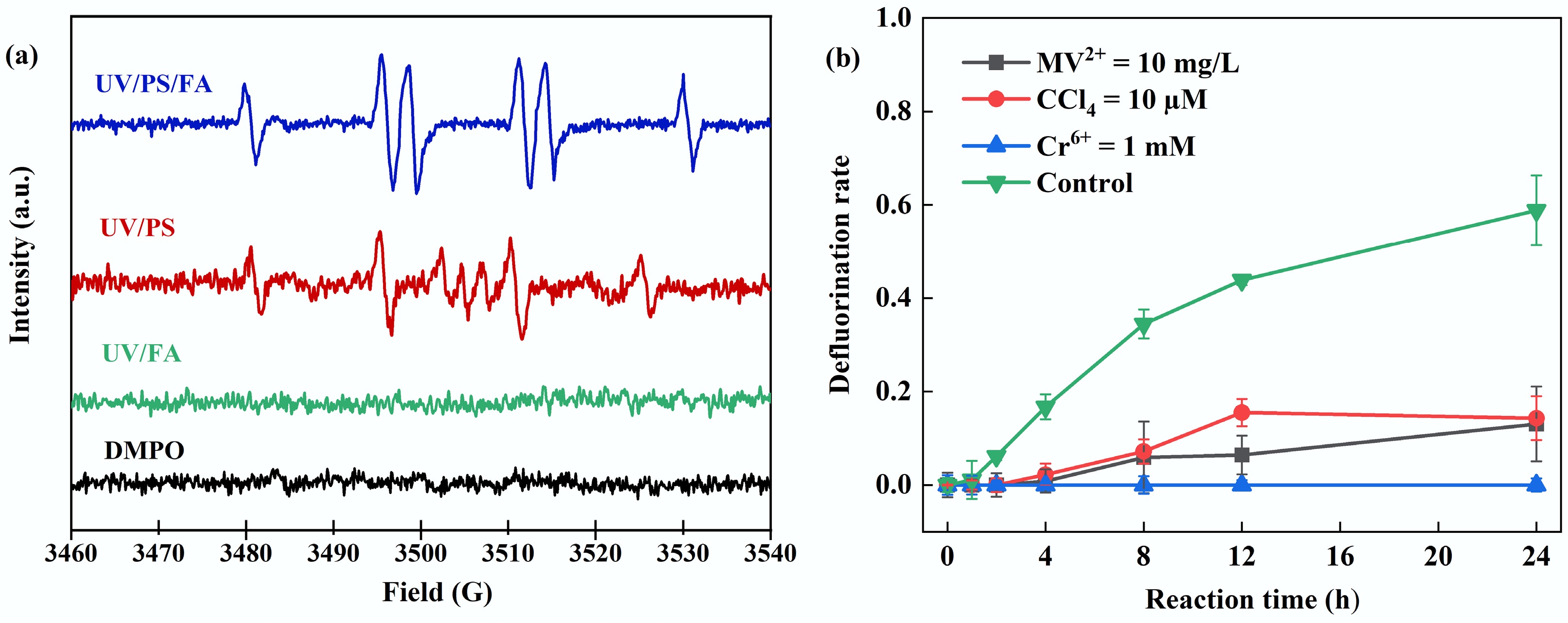

The study identified the key active radicals in the reaction system by combining electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) analyses and radical-quenching experiments. EPR results revealed no characteristic radical signals were detected in the UV/FA system; the UV/PS system exhibited characteristic peaks of DMPO-OH adducts (with peak intensities of 1:2:2:1), confirming •OH generation; whereas in the UV/PS/FA system, a new split peak pattern (with peak intensities of 1:1:1:1:1:1) was observed, with parameters fully consistent with the standard spectrum of DMPO-CO2 adducts, confirming the generation of CO2•− (Fig. 2a)[33]. To verify the role of CO2•− on PFOA defluorination, three quenchers, methyl viologen (MV2+), CCl4, and Cr(VI), were selected for the quenching study (Fig. 2b)[21,34,35]. MV2+, CCl4, and Cr(VI) are all highly reducible compounds, making them effective quenchers for reductive radicals[21,35−37]. MV2+ was used as a competitive scavenger of CO2•− with a reaction rate of (6.3 ± 0.7) × 109 M−1·s−1 [21,37]. The reaction rate of CCl4 and Cr(VI) with CO2•− is (1–5) × 109 and (6–12) × 107 M−1·s−1 [36,38]. The results demonstrated that 1 mM Cr(VI) completely terminated defluorination, while defluorination efficiency of PFOA decreased to 13% and 14% in the presence of MV2+ and CCl4, respectively. Results from radical-quenching experiments and EPR characterization confirm the generation of CO2•− in the UV/PS/FA system, with this reductive radical serving as the primary active species responsible for PFOA degradation. The extremely low reduction potential of CO2•− facilitates its preferential attack on the electron-deficient fluorinated carbon chain of PFOA.

Figure 2.

(a) EPR analysis of UV/PS/FA, UV/PS, and UV/FA systems. (b) Free radical quenching experiments. Reaction conditions: PFOA = 20 µM, initial pH of 2.5, anaerobic environment. (a) PS = 2 mM, FA = 15 mM, DMPO = 100 mM, reaction time = 5 min, anaerobic environment. (b) PS = 4 mM, FA = 2 mM, MV2+ = 10 mg/L, CCl4 = 10 µM, Cr(VI) = 1 mM.

Effects of PFOA, FA, and PS concentrations on PFOA defluorination

-

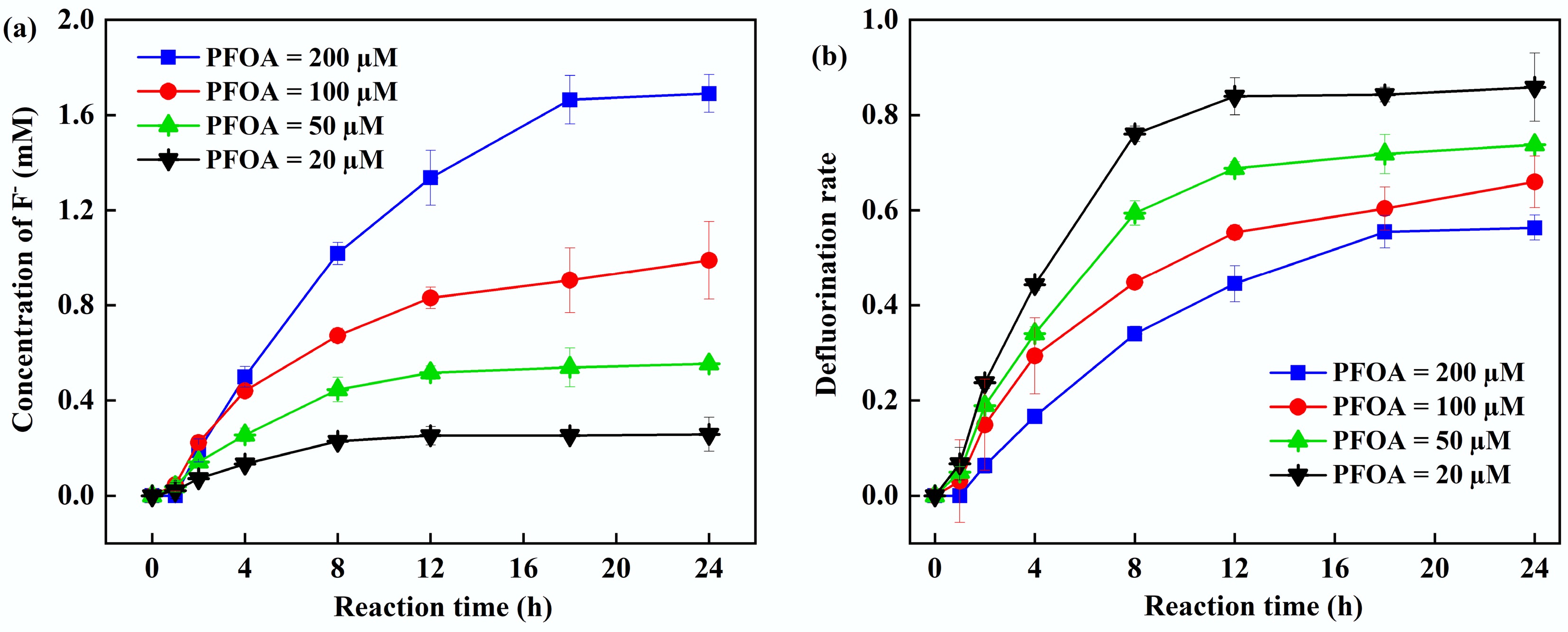

To systematically evaluate the defluorination efficacy of the UV/PS/FA system for PFOA, this study investigated defluorination over the concentration range of 20–200 µM. Figure 3 showed that when the initial PFOA concentration increased from 20 to 200 µM, the F− concentration in the solution after 24 h of reaction increased significantly from 0.26 to 1.69 mM, while the defluorination efficiency decreased from 85% to 55%. This phenomenon is primarily attributed to two mechanisms: (1) Under fixed PS/FA dosages, the CO2•− generated per unit time must act on more PFOA molecules, reducing the probability of radical acquisition per molecule; (2) Short-chain perfluorocarboxylic acids produced during degradation competitively scavenge reactive radicals with PFOA[18,39]. Previous studies have shown that both oxidative and reductive degradation pathways of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances can generate short-chain PFAS, which are more persistent and difficult to degrade[12,40]. Preliminary research revealed that alcohol radicals can produce short-chain PFAS during the degradation of PFOA[13]. It was hypothesized that CO2•− donated an electron to PFOA to make it decarboxylated, and the degradation of PFOA in the PS-FA system would also yield short-chain PFAS (such as C6F13COOH, C5F11COOH, and C4F9COOH)[41]. Notably, despite the efficiency decline under high-concentration conditions, the 55% defluorination rate at 200 µM still significantly surpasses that of traditional Fenton or persulfate oxidation, demonstrating the unique advantage of the UV/PS/FA system in treating high-concentration PFCs pollution.

Figure 3.

(a) Fluoride ion concentration. (b) Defluorination rate at different initial PFOA concentrations. Reaction conditions: PFOA = 20–200 µM, PS = 5 mM, FA = 2 mM, initial pH of 2.5, anaerobic environment.

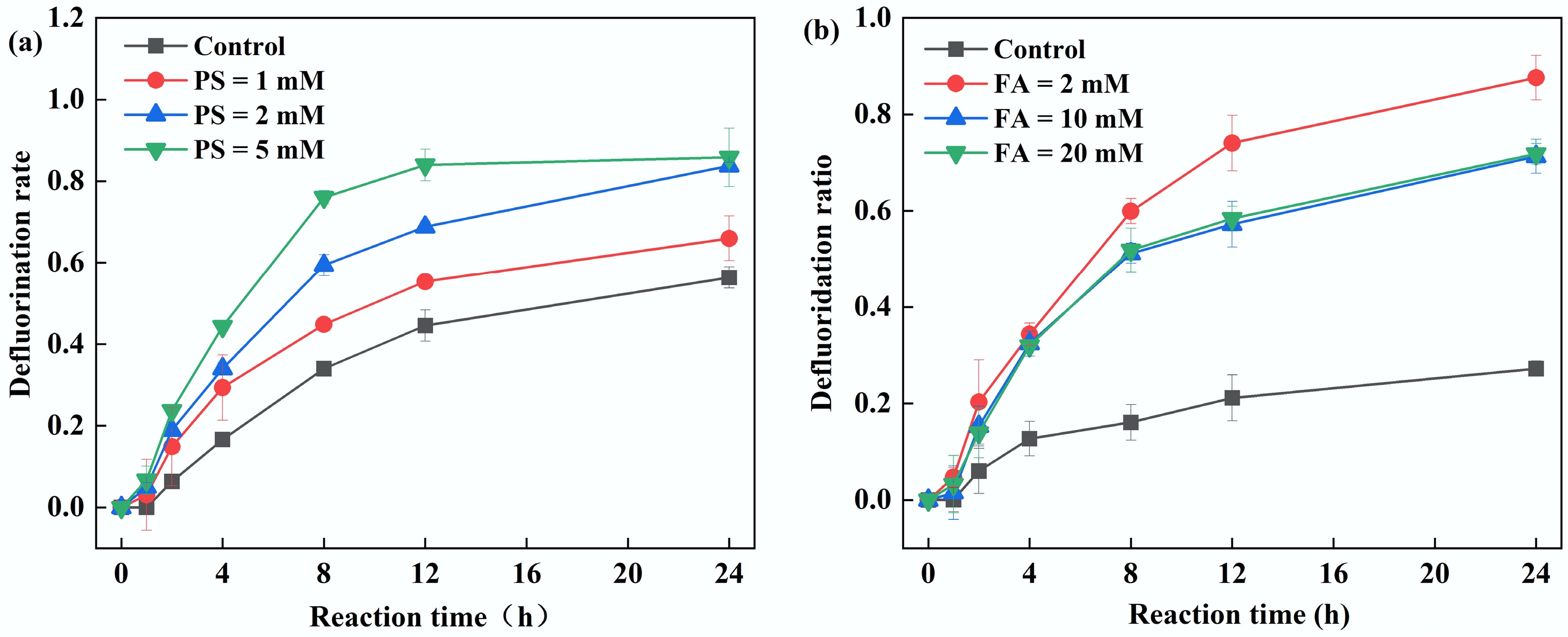

This study further investigated the effects of PS concentration and FA on PFOA defluorination. As shown in Fig. 4a, when the PS concentration increased from 1 to 2 and 5 mM, the defluorination efficiency after 24 h of reaction significantly improved from 66% to 84% and 86%, respectively. This enhancement primarily stems from increased PS concentration, elevating the yield of SO4•− via PS photolysis, which subsequently reacts with FA to generate more CO2•−, thereby promoting PFOA defluorination. Notably, the standalone UV/FA system exhibited a defluorination efficiency of 56%, likely due to direct excitation of FA by 254 nm ultraviolet radiation, producing CO2•−, which can directly attack PFOA. The UV/FA system enables the defluorination of PFOA; however, no CO2•− signal is detected in the EPR spectrum (Fig. 2a). This phenomenon is mainly attributed to the following reason. In the UV/PS/FA system, the oxidative radicals can react with FA to produce abundant CO2•−, and an excessive amount of DMPO (0.1 M) can capture most of these CO2•−. In comparison, the photolysis of FA proceeds relatively slowly, generating only a small quantity of CO2•−. In the PS–FA system, although CO2•− is produced at a high rate, significant side reactions occur. For instance, the reactions of CO2•− with oxidative radicals and PS itself, thereby inhibit the defluorination of PFOA. In contrast, the FA-alone system is free of other strong oxidants, leading to far fewer side reactions. Consequently, even though the production of CO2•− is lower in the FA-alone system, it exhibits higher PFOA degradation efficiency.

Figure 4.

Effect of (a) PS, and (b) FA concentration on PFOA defluorination by the UV/PS/FA system. Reaction conditions: PFOA = 20 µM, initial pH of 2.5, anaerobic environment. (a) PS = 1–5 mM, FA = 2 mM. (b) PS = 5 mM, FA = 2–20 mM.

For the standalone UV/PS system, the defluorination efficiency of PFOA was only 27%, indicating that SO4•− alone has limited defluorination capability. Upon adding 2 mM FA, the PFOA defluorination efficiency significantly increased to 88% (Fig. 4b). However, when the FA concentration was further elevated to 10 and 20 mM, the defluorination efficiency declined to 71% and 72%, respectively. This demonstrates a dual-effect relationship between FA concentration and defluorination efficiency: lower FA concentrations optimally promote PFOA degradation, whereas higher FA concentrations (e.g., 20 mM) partially inhibit defluorination. The inhibitory effect likely stems from the electron-transfer reaction between FA and CO2•−, in which FA acts as an electron acceptor and is subsequently reduced to CO2, HCHO, and H2O as in Eq. (9). Consequently, elevated FA concentrations would competitively suppress the reaction between CO2•− and PFOA.

$ {\mathrm{2CO}_{ \mathrm{2}}}^{ {{\text •}-}} +\mathrm{HCOOH}+{\rm 2H}^{+}\to \mathrm{2CO}_{ \mathrm{2}}+ \mathrm{HCHO}+{\rm H}_{ \mathrm{2}} \mathrm{O} $ (9) The study also investigated the effect of FA concentration on the PFOA defluorination efficiency in the UV/H2O2 system. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S1, the defluorination efficiency reached only 18% in the UV/H2O2 system alone. Upon addition of 2 mM FA, the efficiency increased to 64%. However, as the FA concentration was further raised to 10 and 20 mM, the defluorination efficiency decreased instead to 59% and 42%, respectively. These results indicate that controlling FA concentration is essential in the UV/H2O2/FA system, as excessively high concentrations inhibit PFOA defluorination.

Effects of solution pH and oxygen on PFOA defluorination

-

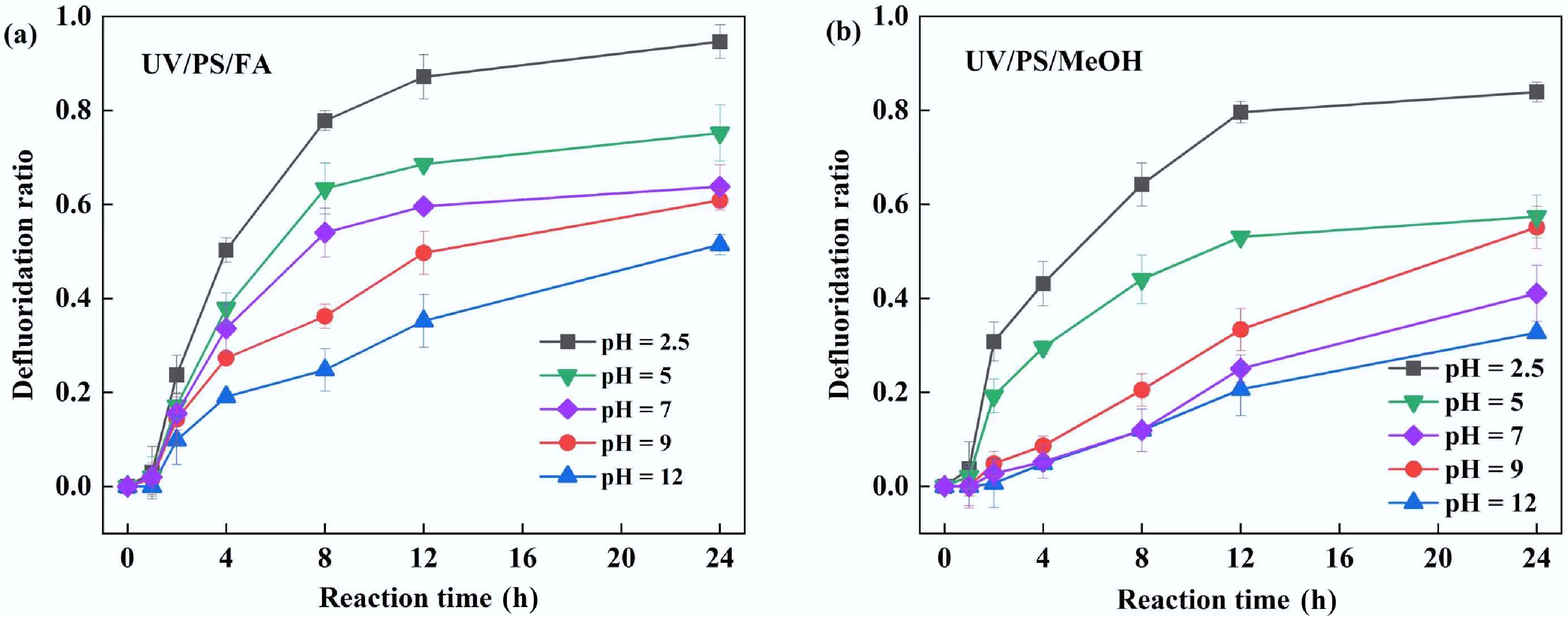

The solution pH can alter the chemical properties, solubility, reactivity, and interactions of pollutants with other substances, thereby influencing pollutant removal efficiency[42,43]. Therefore, this study investigated PFOA defluorination rates across different solution pH levels (Fig. 5). In the UV/PS/FA system, optimal PFOA defluorination occurred under acidic conditions (pH = 2.5), achieving a defluorination rate of 95% after 24 h (Fig. 5a). When pH increased to 5, 7, 9, and 12, the defluorination rates decreased to 65%, 54%, 61%, and 51%, respectively. Similar results were observed in the UV/PS/MeOH system, confirming that acidic conditions favor PFOA defluorination (Fig. 5b). The reaction rate constant of the reaction HCOOH/SO4•− and HCOO−/SO4•− was 4.6 × 105 and 6.1 × 107 M−1·s−1[44]. The solution pH affects the speciation of FA, with its pKa being 3.77. Under strongly acidic conditions, FA primarily exists in its molecular form, whereas under neutral and alkaline conditions, it remains molecular. Therefore, an increase in pH is beneficial for the reaction between SO4•− and FA to generate CO2•−. However, acidic conditions are more favorable for the reaction between CO2•− and PFOA. The suppression of defluorination at elevated pH may be attributed to two factors: First, CO2•− is an anionic radical, while PFOA (pKa = 2.2) exists in an anionic state under neutral or alkaline conditions[45]. Electrostatic repulsion between them hinders the contact and reaction. Under acidic conditions, PFOA exists in a molecular state, free of electrostatic repulsion, facilitating its reaction with CO2•−. Second, both FA (pKa = 2.75) and MeOH (pKa = 15.5) predominantly exist as molecular species at low pH[46]. This allows PFOA to adsorb onto the carboxylic acid group via hydrogen bonding, forming localized micro-reaction domains that promote directed attack on C–F bonds by CO2•− and alcohol radicals. These experimental results demonstrate that an acidic environment enhances the reaction between CO2•− and PFOA.

Figure 5.

Effect of initial pH on PFOA defluorination in (a) UV/PS/FA and (b) UV/PS/MeOH systems. Reaction conditions: PFOA = 20 µM, PS = 4 mM, initial pH = 2.5, 5, 7, 9, 12, anaerobic environment. (a) FA = 2 mM. (b) MeOH = 2 mM.

pH changes were also monitored during the reactions in the UV/PS/FA and UV/PS/MeOH systems (Supplementary Fig. S2). Across different initial pH values, the solution pH in both systems decreased progressively as the reaction progressed, with the addition of formic acid or methanol accelerating acidification. This phenomenon primarily arises from two mechanisms: 1) the decomposition of PS continuously releases H+ ions[29,47]; and 2) the reducing radicals generated from formic acid or methanol react with PS, accelerating its decomposition (Supplementary Fig. S3)[29]. Additionally, reactions between formic acid/methanol and SO4•− also release H+ as in Eqs (6) and (8), collectively driving a progressive pH decline throughout the reaction process.

Previous studies have demonstrated that DO is a critical factor influencing pollutant degradation in advanced reduction systems[29]. To elucidate the impact of DO on the reductive-radical-mediated defluorination of PFOA, this study compared the defluorination efficiencies of UV/PS/FA and UV/PS/MeOH systems under aerobic conditions. The defluorination rates for both systems dropped below 10% within 24 h. This significant reduction is primarily attributed to the competitive reactions between dissolved oxygen and reductive radicals (CO2•− and alcohol radicals)[29,48], as seen in Eqs (10) and (11), which quench the reductive radicals responsible for PFOA degradation.

To further investigate oxygen production and consumption in the reaction system, the dynamic changes in DO during the reaction were monitored (Supplementary Fig. S4). Under aerobic conditions, the DO concentration in the UV/PS/FA system gradually decreased from 8.5 to 4.5 mg·L−1. In contrast, no significant changes were observed in the UV/PS system or the control group. This phenomenon is attributed to the continuous consumption of DO through reactions between reductive radicals and O2. The UV/PS system, lacking the radical conversion induced by FA, exhibited no DO consumption. The DO can affect the oxidative degradation of pollutants, but overall, its impact on degradation is not very significant, especially in homogeneous systems[29,49]. However, reductive radicals readily react with oxygen, so oxygen has a greater influence on their pollutant degradation efficiency. These findings confirm that maintaining an anaerobic environment is a critical prerequisite for ensuring reductive radicals dominate the PFOA defluorination.

$ \mathrm{O}_{ \mathrm{2}} +{\mathrm{CO}_{ \mathrm{2}}}^{{{\text •}-}} \to{{\rm O}_{ \mathrm{2}}}^{ {{\text •}-}} +\mathrm{CO}_{ \mathrm{2}} $ (10) $ \mathrm{O}_{ \mathrm{2}}+ \mathrm{{\text •}CH}_{ \mathrm{2}}{\rm OH} \to {\rm HCHO}+{{\rm HO}_{ \mathrm{2}}}^{ \text{•}} $ (11) Effects of anions and organic matter on PFOA defluorination

-

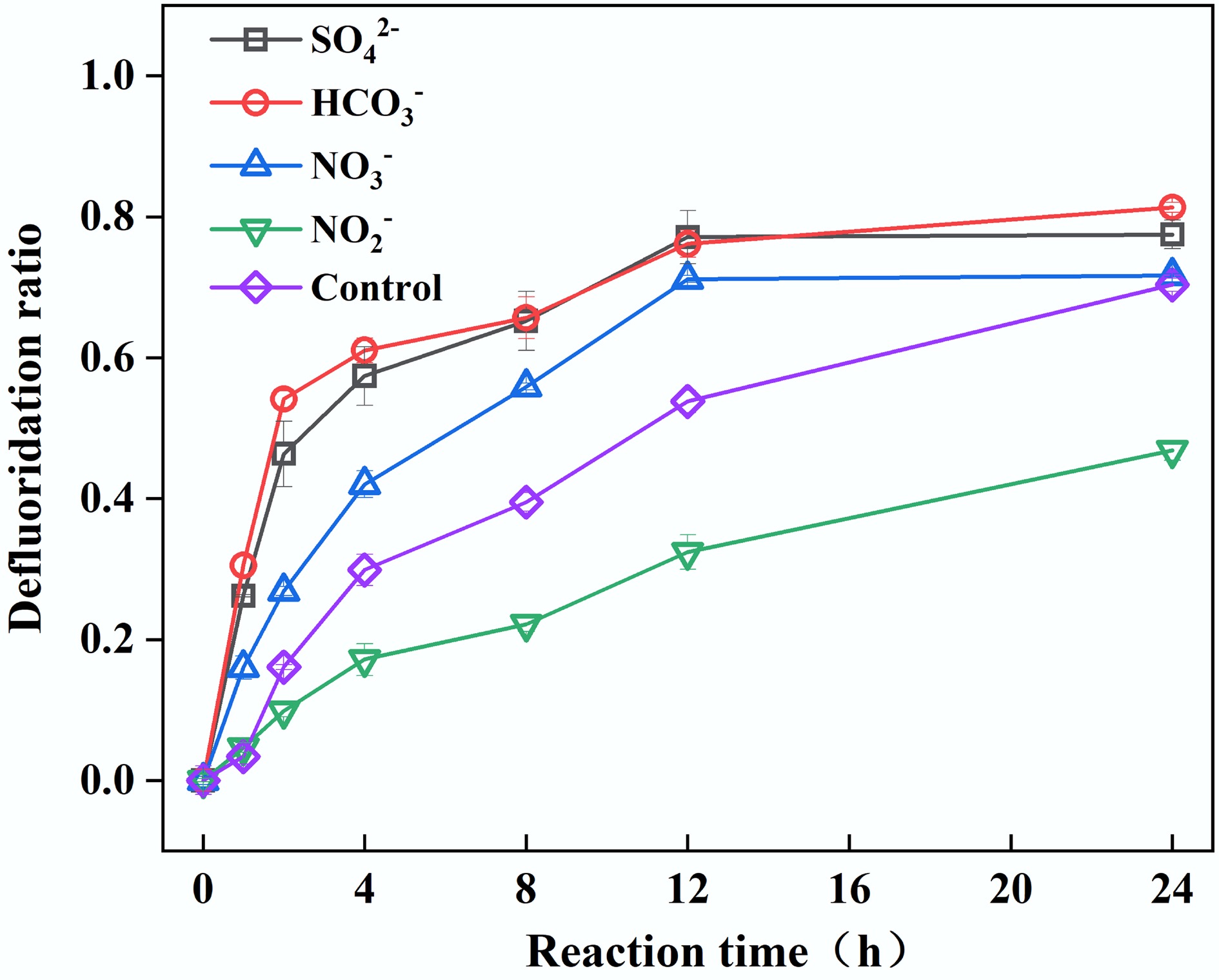

In aquatic systems, anions such as SO42−, HCO3−, NO3−, and NO2− are ubiquitously present[50,51]. This study investigates the mechanisms by which they influence PFOA defluorination in a UV/PS/FA system. Figure 6 demonstrated that at a coexisting anion concentration of 10 mM, SO42−, HCO3−, and NO3− all enhance PFOA defluorination efficiency. This promotion likely occurs because both PFOA (R-COO−) and the CO2•− radical carry negative charges, generating electrostatic repulsion that hinders effective contact; the introduction of exogenous anions mitigates this repulsion through ionic strength effects, compressing the diffuse double layer (charge neutralization mechanism), thereby improving radical attack efficiency. In contrast, the addition of NO2− significantly reduces PFOA defluorination efficiency from 70% in the control group to 47%, primarily attributed to the efficient quenching reaction between NO2− and SO4•− (k = 8.8 × 108 M−1·s−1)[52]. This reaction depletes SO4•−, consequently inhibiting CO2•− generation and subsequent PFOA defluorination reactions. Collectively, apart from NO2−, other anions exhibit minor impacts on the CO2•−-dominated PFOA degradation pathway. Specific synergistic/competitive mechanisms require further exploration.

Figure 6.

Effect of NO3−, NO2−, SO42−, and HCO3− on PFOA defluorination. Reaction conditions: PFOA = 20 µM, PS = 4 mM, FA = 2 mM, NO3−, NO2−, SO42−, HCO3− = 10 mM, unadjusted pH, anaerobic environment.

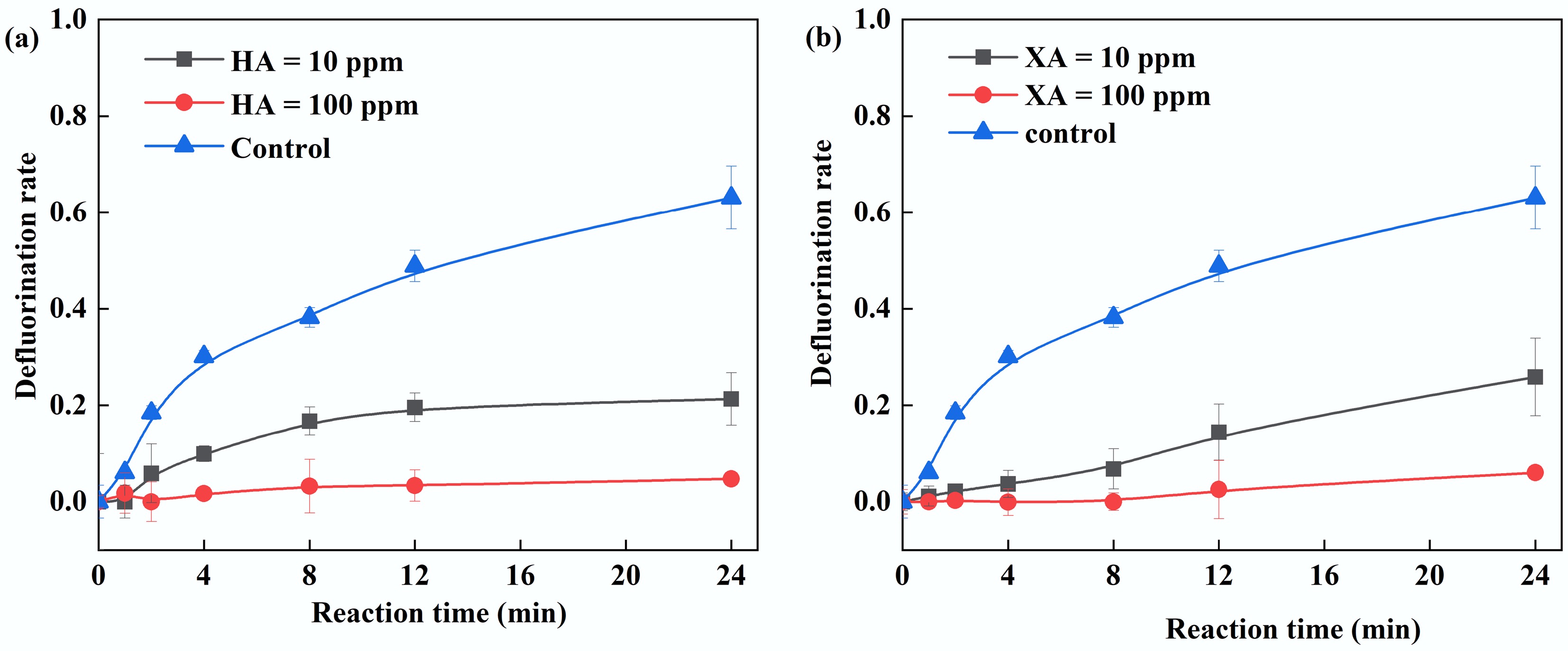

Humic acid (HA) and xanthohumic acid (XA), as representative components of natural organic matter, possess molecular structures rich in redox-active functional groups such as phenolic hydroxyl and quinonyl moieties[53,54]. These constituents can interfere with advanced oxidation processes by competing for radicals or altering reaction pathways. This study investigates the inhibitory effects and mechanisms of HA/XA on PFOA degradation in the UV/PS/FA system. The findings indicate a significant dose-dependent inhibitory effect of HA/FA on the defluorination of PFOA. Notably, the defluorination efficiency fell below 10% at 10 ppm HA/XA and approached near complete cessation at 100 ppm (Fig. 7). This inhibition originates from the preferential reaction between phenolic/quinonoid groups in HA/XA and reactive radicals (SO4•−, •OH)[55], which prevents the formation of the critical intermediate CO2•−. Additionally, carbonyl groups (C=O) in HA/FA can further react with CO2•−, ultimately suppressing PFOA defluorination.

-

Among various redox systems compared, the UV/PS/FA system demonstrates superior PFOA defluorination performance, achieving 89% defluorination efficiency within 24 h. This high efficiency originates from FA's targeted regulation of radical reaction pathways: PS photolysis generates SO4•−, which preferentially oxidizes FA to produce highly reductive CO2•−. This potential is markedly lower than that of the reference •CH2OH, enabling CO2•− to more effectively attack the lowest electron density sites in C–F bonds of the PFOA carbon chain, thereby initiating stepwise defluorination. FA concentration exhibits characteristic dual-phase regulatory behavior. A total of 2 mM elevates defluorination efficiency in the UV/PS system from 27% to 87%, whereas 20 mM reduces efficiency due to radical quenching. Environmental factor analysis reveals that common anions (e.g., SO42−/HCO3−/NO3−) enhance reactivity by weakening electrostatic repulsion between PFOA (R-COO−) and CO2•− through ionic strength effects, while humic/fulvic acids (HA/FA) inhibit defluorination as their phenolic hydroxyl/quinone groups competitively scavenge SO4•− and CO2•−. These findings provide new perspectives for the efficient defluorination of perfluorinated compounds.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/ebp-0025-0012.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: Changyin Zhu: methodology, investigation, writing - original draft; Qiang Zhang: investigation, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing; Xiaolei Wang: methodology; Dongmei Zhou: methodology, writing - review & editing, resources, funding acquisition. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets used or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 22176091, 42377010), and the State Key Laboratory of Water Pollution Control and Green Resource Recycling Foundation (Grant No. PCRRF25048).

-

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

-

PFOA undergoes reductive defluorination more readily than oxidative defluorination.

FA reacts with oxidative radicals to generate CO2•−, which defluorinates PFOA.

Acidic pH facilitates the defluorination of PFOA in the UV/PS/FA system.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- The supplementary files can be downloaded from here.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu C, Zhang Q, Wang X, Zhou D. 2025. Synergistic enhancement by formic acid in the oxidation system for perfluorooctanoic acid defluorination: efficiency and mechanism. Environmental and Biogeochemical Processes 1: e013 doi: 10.48130/ebp-0025-0012

Synergistic enhancement by formic acid in the oxidation system for perfluorooctanoic acid defluorination: efficiency and mechanism

- Received: 07 August 2025

- Revised: 09 October 2025

- Accepted: 29 October 2025

- Published online: 05 December 2025

Abstract: Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), a persistent organic pollutant with high oxidative resistance, presents significant challenges for efficient defluorination. This study demonstrates a novel approach to enhance PFOA defluorination efficiency in a UV-activated persulfate (PS) system by introducing formic acid (FA). Results showed that the UV/PS system alone achieved merely 27% PFOA defluorination in 24 h, whereas adding 2 mM FA significantly enhanced defluorination efficiency to 89%. Quenching experiments and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) analyses identified carbon dioxide radical anions (CO2•−) as the dominant active radicals driving PFOA reduction. The oxidative radicals (SO4•− and •OH) derived from PS activation react with FA to generate CO2•−, thereby facilitating efficient PFOA degradation. PS and FA concentrations, solution pH, and the presence of common anions (SO42−, HCO3−, NO3−, and NO2−) were systematically evaluated for their impact on PFOA defluorination. This study presents a simple yet effective method for PFOA defluorination, offering new insights into the defluorination of perfluorinated compounds.

-

Key words:

- PFOA /

- Defluorination /

- Carbon dioxide radical anion /

- Formic acid