-

Iron (oxyhydr)oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) are ubiquitous in soils, sediments, and aquatic environments, where they can substantially influence the biogeochemical cycles of nutrients and contaminants[1−3]. The formation pathways of IONPs and their interactions with metal ions, organics, minerals, and microbes have been detailed in our earlier review[4]. Once formed, IONPs undergo aggregation and phase transformation processes, which control their long-term stability. Here, the environmental stability of IONPs, controlled by their interactions with metal ions, organics, and microbes, after their formation, is summarized. Together, the two reviews provide an integrated understanding of IONP evolution—from formation to transformation—in complex natural environments.

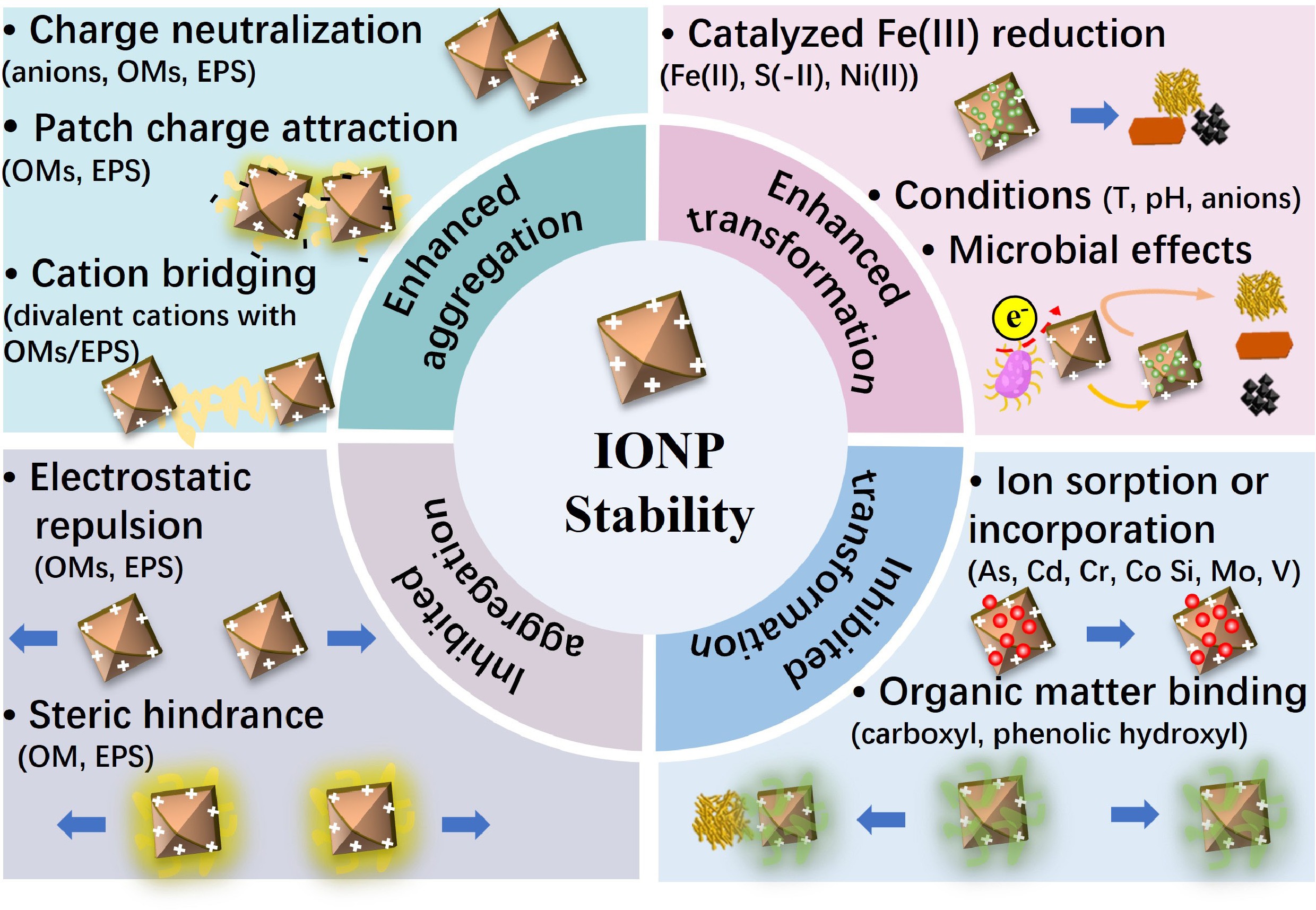

Whether IONPs rapidly aggregate and subsequently settle, or remain as stable colloids over extended periods strongly influences the transport and fate of IONPs and associated elements[5−9]. The extent of IONP aggregation depends upon interparticle forces, such as electrostatic repulsion/attraction, van der Waals attraction, external bridging forces (bridging flocculation) and steric hindrances, which are also dependent on environmental parameters, such as pH, ionic strength, and the presence of metal ions, organics, and extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) from microbial activity.

The transformation of IONPs into more stable phases strongly determines their stability as well. Indeed, metastable, poorly crystalline IONPs, such as ferrihydrite, can spontaneously transform into more stable phases, such as goethite or hematite, following a dissolution-reprecipitation or solid-state conversion pathway, respectively[9,10]. Transformation profoundly alters particle morphologies, surface area, and reactivity, thereby controlling elemental binding capacities and affecting the environmental transport and long-term biogeochemical cycling of associated contaminants and nutrients[11]. Transformation can be affected by environmental factors, such as the extent of iron oxidation (i.e., Fe2+/Fe3+ ratio) and the presence of metal ions, organics, and microbes.

Metal ions exert strong, concentration-dependent control over IONP aggregation. Adsorbed cations can compress the electrical double layer (EDL), neutralize surface charges, and create inter-particle 'cation bridges' to drive diffusion-limited aggregation as a function of cation valence[12−14]. Trivalent ions such as Fe3+ or Al3+ can also hydrolyze to form polynuclear surface complexes that bind neighboring particles into compact flocs[14]. For transformation, certain metal ions can substitute into the ferrihydrite lattice during coprecipitation to potentially hinder or delay subsequent Ostwald ripening[11,15]. Conversely, aqueous Fe(II) generated under reducing conditions rapidly catalyzes the transformation of ferrihydrite into lepidocrocite, goethite or magnetite[16,17] . Thus, the speciation and valence state of co-occurring metal ions dictate whether freshly precipitated IONPs remain as dispersed nano-colloids, form dense metal-bridged aggregates, or transform into more crystalline minerals.

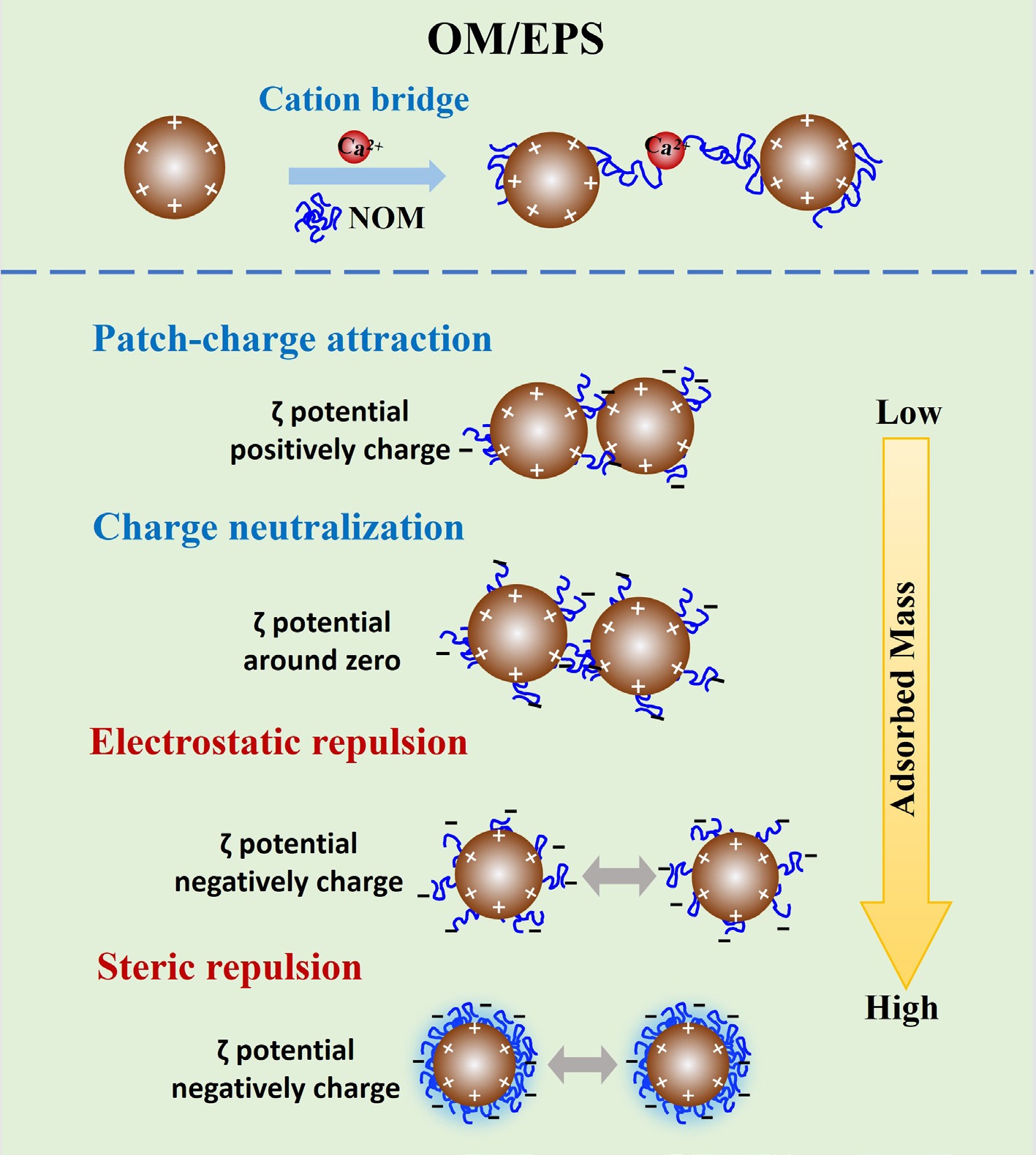

Natural organic matter (NOM) also plays essential roles in modulating IONP stability. The sorption of NOM to IONP surfaces through electrostatic interactions or covalent bonds facilitated by ligand exchange substantially affects IONP surface charge and hydrophobicity, which in turn control particle aggregation. Depending on NOM concentrations, ligand types, and molecular characteristics (e.g., molecular weight [MW]), NOM can either stabilize IONPs via electrostatic and/or steric repulsion, promote their aggregation through bridging or patch-charge effects[5,6,18] and charge-neutralization flocculation[18−20], or inhibit aggregation through repulsive electrostatic interactions and steric hindrances as a function of surface coverage[21−25]. NOM-IONP interactions can also alter transformation pathways or suppress transformation entirely, which is attributable to NOM blocking reactive surface sites, stabilizing structural Fe species, or affecting electron transfer processes with reactive species[11,26], thereby potentially preserving ferrihydrite or lepidocrocite against conversion to goethite or magnetite[27−31].

Microbial processes are intimately involved in both the aggregation and transformation of IONPs. Bacterial, algal, and fungal EPS adsorb onto nanoparticle surfaces, typically dispersing IONPs. However, partial EPS coverage, combined with Ca2+ or Mg2+ cross-linking, can reverse this behavior and induce strong flocculation[12,32−34]. Iron-reducing bacteria (FeRB), such as Geobacter and Shewanella, use Fe(III) as a terminal electron acceptor under anaerobic conditions, leading to the reductive dissolution of IONPs. The dynamic cycling between oxidation and reduction driven by microbial activity substantially affects the environmental stability of IONPs[35]. The rate of abiotic transformation of metastable IONPs to more stable phases was widely reported to be enhanced by the presence of aqueous Fe2+ or increased temperature. The former, referred to as 'Fe(II)-catalyzed transformation', could thus be strongly affected by microbial activities.

Overall, the stability of IONPs in natural environments, with a focus herein on both their aggregation tendencies and phase transformation processes, is a crucial factor controlling their environmental fate and the fate of associated contaminants and nutrients. This review summarizes the present understanding of how metal ions, organics, and microbial processes affect IONP stability. Understanding these mechanisms will improve our ability to predict the transport of these nanoparticles and associated species, and will guide management strategies for soil and water quality.

-

IONPs are ubiquitous in natural waters, soils, and sediments, where their mobility and reactivity are strongly influenced by their colloidal stability. Due to their high surface energy, these particles readily undergo aggregation that can alter their transport behavior, surface reactivity, and interactions with contaminants. The aggregation of IONPs is governed by a delicate balance of electrostatic repulsion, van der Waals attraction, and additional effects such as steric hindrances or cation bridging effects. Environmental conditions such as pH, ionic strength, the presence of multivalent ions, NOM, and microbial EPS collectively shape this balance. For instance, while NOM and microbial products often enhance colloidal stability through electrostatic effects, divalent and trivalent cations can neutralize surface charges or bridge particles to promote aggregation. A sound understanding of the mechanisms controlling aggregation is crucial for predicting the fate and transport of IONPs in environmental systems. This section provides a review of recent advances in our understanding of IONPs aggregation, with a focus on the roles of metal ions, organic matter (OM), and microbial EPS in governing IONP stability under environmentally relevant conditions.

Metal-driven aggregation

-

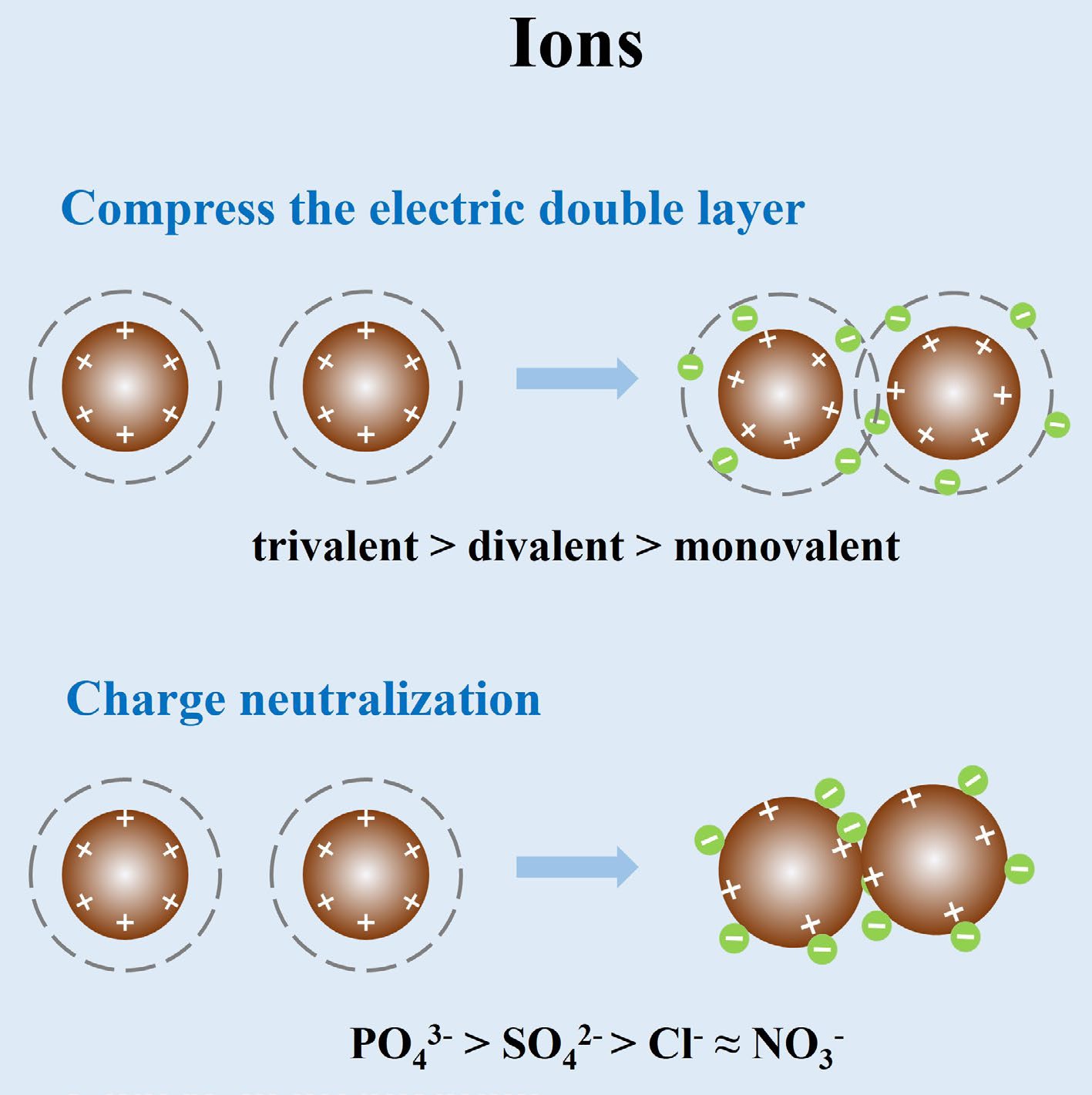

The aggregation behavior of IONPs is highly sensitive to the surrounding ionic composition. In aqueous environments, common electrolyte ions can drastically alter colloidal stability through several mechanisms. Higher ionic strengths promote aggregation by compressing the EDL, which reduces electrostatic repulsion and allows van der Waals attractions to dominate (Fig. 1)[12]. According to the classic Derjaguin–Landau–Verwey–Overbeek (DLVO) theory, increasing salt concentrations drive a transition from a reaction-limited aggregation regime (particles collide but often repel) to a diffusion-limited regime (particles stick upon collision) once the 'critical coagulation concentration' (CCC) is exceeded[13]. For example, goethite nanoparticles required on the order of 10–50 mM of monovalent NaCl or NaNO3 to reach rapid aggregation, whereas only ~0.3 mM of a divalent electrolyte (Na2SO4) was needed due to stronger electrostatic screening by the divalent ions[12]. This dramatic decrease in CCC with divalent ions exemplifies the general trend that multivalent ions induce aggregation at much lower concentrations than monovalent ions[14]. Such findings underscore how increased ion valence and hence charge can lead to enhanced double-layer compression and charge neutralization, greatly facilitating nanoparticle aggregation. Consistently, the effectiveness of cations in aggregating negatively charged IONP colloids follows a Hofmeister-like series relating to ionic charge density and hydration: e.g., Ba2+ > Sr2+ > Ca2+ > Mg2+ >> Na+. Further, trivalent metal cations, such as Al3+ or Fe3+, which are commonly used coagulants in water treatment, can neutralize surface charges even more strongly, causing rapid coagulation[14].

In addition to general EDL screening, specific ion adsorption and charge neutralization mechanisms play critical roles during aggregation. The surface charges of IONPs often exhibit a dependence on pH, being positively charged in acidic conditions and negative in alkaline conditions. Ions of opposite charges can adsorb onto the nanoparticle surface to neutralize or even reverse its surface charge. When the net surface charge approaches zero, electrostatic repulsion vanishes, and particles readily aggregate upon collision[36]. Indeed, conditions near the point of zero charge (PZC) of the IONPs often produce the most unstable suspensions. Similarly, adsorbing ions can induce 'charge-neutralization coagulation': a low concentration of multivalent counter-ions can neutralize the surface charge of IONPs and cause them to coalesce following a classical coagulation mechanism (Fig. 1)[37]. Notably, phosphate exhibits unique behavior: at low levels, phosphate adsorption neutralized positively charged IONP surfaces, triggering aggregation via charge neutralization, but at higher phosphate levels, the particles acquired a net negative charge due to extensive phosphate adsorption, restabilizing the suspension until eventually the increasing ionic strength from Na+ counter-ions in Na3PO4 again causes aggregation at very high concentrations[14]. These complex effects demonstrate that ion adsorption chemistry can control the extent of aggregation.

Another important mechanism for aggregation is cation bridging, a form of specific ion effect particularly relevant in the presence of NOM or other surface-bound ligands (Fig. 2). Divalent cations, such as Ca2+ and Mg2+, can function as bridges that link together negatively charged functional groups on different particles. For example, IONPs in environmental media often associate with NOM coatings rich in carboxylate groups. Ca2+ has a strong affinity for these groups and can cross-link particles by forming ternary complexes, effectively 'gluing' NOM-coated nanoparticles into aggregates[38]. This cation-bridging mechanism is distinct from pure electrostatic screening: Ca2+ not only shields charge but also creates chemical bonds between colloids. Wang et al. observed that the aggregation tendency of magnetite (Fe3O4) nanoparticles in NOM-rich waters increased in the order Na+ < Mg2+ < Ca2+, corresponding to each cation's ability to complex with NOM on the particle surfaces[38]. In their tests, low levels of Ca2+ caused a dramatic destabilization of NOM-coated Fe3O4, whereas Na+ had a comparatively minor effect. Likewise, Chekli et al. reported that low concentrations (~1 mg/L) of CaCl2 induced rapid flocculation of DOM-coated IONPs that were otherwise stable in high ionic strength NaCl solutions, due to charge neutralization and inter-particle bridging by Ca2+[21]. Beyond alkaline earth cations, certain transition-metal cations can also bridge particles: for example, trivalent Fe3+ or Al3+ can precipitate as polynuclear complexes that bind colloids together, further highlighting that ionic composition can induce aggregation via both electrostatic interactions and coordinative bonding pathways[14].

Organics affect colloidal stability

-

OM can profoundly affect the aggregation behavior of IONPs through multiple mechanisms[22,39,40]. The adsorption of OM onto IONPs can drastically alter particle surface charge and hence colloidal stability. If a positively charged IONP, associated with a pH below its PZC, binds a small amount of negatively charged OM, the resulting effects on particle aggregation depend on adsorbed OM amounts and surface coverage. Where adsorbed OM amounts are insufficient for complete surface coverage, OM sorption occurs as isolated patches to create localized negative regions across positively charged particle surfaces. Attractive electrostatic interactions between oppositely charged regions on different particles can dramatically enhance aggregation[18], a phenomenon termed 'patch-charge attraction' (Fig. 2). Previous studies used single particle inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (SP-ICP-MS), and static light scattering (SLS) to characterize this mechanism[5,6], and identified that low MW, low carboxyl richness OMs, which adsorbed to IONPs in low masses, preferentially caused this mechanism.

With increasing adsorbed amounts of negatively charged OM, IONP surface charges gradually shift from positive to zero. In turn, overall electrostatic repulsion between particles, as suggested by the DLVO theory, decreases, and aggregation is promoted. Subsequent destabilization was predominantly associated with charge neutralization, as reported for several representative iron oxides such as hematite and magnetite upon OM addition at environmentally-relevant pH values[18−20]. It is noteworthy that patch-charge attraction occurs when low levels of organic ligands create charged 'patches' on IONP surfaces, promoting strong, non-DLVO aggregation even below the CCC. In contrast, charge neutralization uniformly reduces surface charge and follows classical DLVO behavior. Because patch-charge attraction is much stronger, it can dominate IONP destabilization in natural waters containing low concentrations of small, low-MW organics.

The adsorption of a large amount of OMs or of OMs with a large number of deprotonated acidic functional groups, such as carboxyl groups, may eventually cause a reversal in surface charge and subsequently stabilize the particles[22]. For instance, Chekli et al.[21] found that IONPs aggregated at low Suwannee River NOM (SRNOM) concentrations due to a decrease in surface charge from positive to near zero, but IONP aggregation was inhibited when the SRNOM concentration further increased as particles became negatively charged and repulsive electrostatic forces dominated[21]. This demonstrates the significance of accounting for C/Fe ratios on aggregation behaviors and the important role of the intrinsic properties of OMs (Fig. 2).

In addition to electrostatic repulsion, steric repulsion can present a significant mechanism and, in many conditions, can be dominant over the effects of electrostatic interactions. Adsorbed OM can form a layer on the particle surface and, if the adsorbed layer thickness exceeds the Debye length, electrostatic interactions can have a limited effect on aggregation. Works focused on the stability of various organic coated magnetite nanoparticles (MNPs) reported that while the stabilization mechanisms of these particles without NOM additions differed due to distinct thicknesses of coatings, steric repulsion dominated in the presence of NOM[23,24]. Such results are inconsistent with particle aggregation following classical DLVO theory, and an extended DLVO theory, which incorporates steric interactions, should be applied instead. Wu et al. successfully employed an extended DLVO theory that included steric, gravitational, and magnetic attraction forces to explain the effects of water chemistry on aggregation and sedimentation of natural goethite and artificial Fe3O4 nanoparticles[25].

OM can complex with multivalent cations such as Ca2+ and induce bridging flocculation. Such bridging flocculation cannot be directly described by the extended DLVO theory, and a molecular model for the adsorbed layer and its interactions is needed to combine with the extended DLVO theory. It has been reported that long molecules are prone to complexation with multivalent cations and can lead to flocculation[39]. Chen et al. proposed that Ca2+ formed bridging interactions with alginate adsorbed on the hematite surface through complexation, thus enhancing aggregation. Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images, which showed hematite primary particles and lower-order aggregates trapped within an extended network of an alginate gel supported the proposed mechanism[41]. In contrast, such bridging effects did not take place in the presence of Na+ or Mg2+. Previous works reported the effects of MW and carboxyl richness of OM on its adsorption onto ferrihydrite nanoparticles (FNPs) and the resulting aggregation. For OM with low carboxyl richness, aggregation was promoted through a bridging effect at low adsorbed masses, while aggregation was facilitated at medium adsorbed masses of OM with high carboxyl richness through patch-charge attraction effects and was inhibited at high adsorbed masses due to steric repulsion[6]. Again, this highlights the effects of diverse characteristics of OM and their interactions with electrolytes. Aromaticity, functional group identities and amounts, and MW, are all key factors which should be considered when investigating the effects of OM on particle stability.

Microbes influence aggregation

-

In natural environments, the aggregation behavior of IONPs is strongly modulated by microorganisms, primarily through the production of EPS. This section discusses the dominant mechanisms, especially those mediated by EPS, by which microbes influence IONP aggregation, including electrosteric stabilization, polymer and cation bridging, local pH and redox alterations, and direct microbe–mineral interactions.

EPS, representing complex mixtures of high-MW biopolymers (e.g., nucleic acids, lipids, polysaccharides, and proteins), ubiquitously coat mineral nanoparticle surfaces[42]. Adsorbed EPS often imparts a net negative surface charge to IONPs due to deprotonated ligands in EPS (e.g., carboxyl, phosphoryl, and sulfate groups), thereby shifting the particle zeta potential and modifying electrostatic interactions[12]. For example, Lin et al. showed that adding Bacillus subtilis EPS to goethite (α-FeOOH) nanoparticles (NPs) markedly affected aggregation depending on pH and ionic strength[12]. When goethite NPs were positively charged (pH 6, below their PZC ~8), trace EPS adsorption led to charge neutralization and inter-particle bridging, promoting aggregation[12]. In contrast, under higher ionic strength conditions, a more complete EPS coating for goethite rendered the NPs significantly more stable: the CCC in NaCl, NaNO3, and Na2SO4 increased 3–5 fold upon EPS addition[12]. This stabilization reflects an electrostatic and steric repulsion: EPS molecules on the IONP surface provide an electrostatic barrier (negative charge), and alongside steric hindrances, inhibit particle aggregation (Fig. 2)[32]. Such EPS-induced electrosteric stabilization has also been observed with other nanoparticles (e.g., Ag, TiO2), where EPS or similar biopolymers adsorbing as a corona led to more negative surface charges, and suppressed aggregation rates[33]. Thus, in many natural waters, the presence of microbial EPS can keep IONP colloids dispersed by increasing their surface charge and introducing steric repulsion, especially when EPS fully coats the particles.

Paradoxically, the same EPS under different conditions can cause destabilization and aggregation of IONPs via bridging flocculation. If EPS adsorption is partial or patchy, or if polymer chains extend sufficiently from the surface, a single EPS molecule can form bridges to bind multiple nanoparticles together. This tends to occur when EPS and particle charges are opposite or when EPS concentrations are sufficient to form inter-particle links but insufficient for complete monolayer coverage. Divalent cations common in natural waters (such as Ca2+ and Mg2+) greatly facilitate this process. These multivalent ions can cross-link anionic functional groups on EPS coated IONP surfaces, or bind two EPS-coated particles together, effectively acting as ionic bridges[32]. As a result, the presence of Ca2+ often triggers rapid flocculation of EPS-laden IONP colloids. Empirical studies support this view: oleate-coated IONPs have a CCC in NaCl that is two orders of magnitude higher than in CaCl2 (710 and 10.6 mM, respectively), underscoring the potent aggregation caused by divalent cation bridging compared to simple charge screening by monovalent ions[34]. Similarly, in heteroaggregation experiments, adding Ca2+ enhanced the coalescence of EPS or humic-coated iron oxides and other particles by neutralizing surface charge and forming intermolecular bridges[32]. The propensity for cation bridging can vary with EPS composition. For instance, EPS rich in acidic polysaccharides may bind Ca2+ more readily than protein-rich EPS, leading to stronger flocculation in the former[32]. Overall, EPS can both stabilize IONPs via electrosteric effects and destabilize them via bridging, with the net outcome governed by factors like pH (relative to the IONP's pHpzc), ionic composition, and the molecular makeup of the EPS[12].

Microbial EPS is a major component of NOM in many systems and often coexists with humic and fulvic substances. Notably, EPS and humic substances may compete or synergize in coating IONPs. One recent comparison found that a given concentration of algal EPS had differing effects on IONP heteroaggregation with other colloids relative to humic acid, likely because humic substances, being smaller and more aromatic, can more effectively promote Ca2+ bridging and charge neutralization, whereas high-molecular-weight EPS might impart greater steric stabilization[32].

In addition, the EPS can coat microbes as biofilms, creating a distinct microenvironment affecting IONP heteroaggregation with (deposition onto) biofilms. Biofilm EPS is spatially arranged as a viscoelastic network that can physically trap nanoparticles in its gel-like structure[43]. Indeed, biofilms spanning pore spaces have been shown to retain colloidal particles by sieving and adhesion, a mechanism of capture independent of classic DLVO forces[43]. Trapped within a biofilm, IONPs may aggregate locally to form cell-EPS-mineral clusters. Bacterial cells are typically negatively charged, so positively charged iron oxides or oppositely charged EPS-coated NPs readily adhere to cell envelopes[44]. This attachment can be mediated by electrostatic attraction or more specific ligand exchange and coordination bonds (e.g., between Fe3+ sites and phosphoryl groups on cell surfaces)[44]. The result is often a bacterium–mineral assemblage that may settle out or become enmeshed in biofilm. In natural waters, such heteroaggregates of microbes, EPS, clays, and iron (oxy)hydroxide nanoparticles contribute to the formation of larger flocs ('microbial iron floc') that control the mobility and sedimentation of iron nanoparticles.

Finally, microbial metabolism can also influence IONP aggregation indirectly by altering local solution chemistry. As microbes respire and produce metabolites, they can create pH microgradients within biofilms or sediment pores. For example, microbial production of organic acids or CO2 can locally lower pH, potentially approaching the PZC of iron oxides and thus reducing their surface charge, which promotes aggregation. Conversely, alkalinization by photosynthetic microbes could increase negative surface charges and enhance stability. In addition, microbes drive redox transformations of Fe that also affect particle aggregation. Iron-reducing bacteria (e.g., Geobacter, Shewanella) convert Fe(III) (insoluble oxide) to Fe(II), which often leads to partial dissolution of IONPs and the release of smaller colloidal fragments[45]. In one study, stimulating Fe(III)-reducing bacteria in soil aggregates led to a pulse of Fe(II) and new colloid generation, which initially dispersed previously aggregated iron oxide, increasing the mobility of nanoparticles[45]. However, prolonged bioreduction had the opposite effect: the breakdown of soil aggregates and production of secondary iron phases eventually caused more nanoparticle retention (re-aggregation and filtration) as the system re-equilibrated[45]. These biomineralization processes illustrate that microbial redox activity can transform dispersed nanoscale iron into larger crystalline or aggregate forms within the microbial matrices. In essence, microbes not only contribute passive organic coatings but actively remodel the physicochemical environment (pH, redox state, and ion balance), thereby indirectly governing whether iron nanoparticles remain colloidally stable or assemble into larger aggregates.

In summary, the presence of microbes and their EPS tends to moderate IONP aggregation behavior, potentially inhibiting aggregation by forming protective organic coatings, while potentially promoting aggregation by acting as natural flocculants. Basically, the effect of EPS and NOM on IONP aggregation is similar (Fig. 2). It is noteworthy that the interaction between OMs/EPS and metal ions can largely control the IONP aggregation. As discussed below, in monovalent ions such as Na+, the copresence of OMs/EPS could inhibit the aggregation by steric repulsion or electrostatic repulsion, while enhancing the aggregation by patch-charge attraction. However, in the presence of di-/tri- valent ions, the aggregation is always enhanced by the bridging effect. Recognizing this dynamic interplay is crucial for accurately predicting IONP transport, bioavailability, and deposition in environmental and engineered contexts. The aggregation state of IONPs in nature is thus not an intrinsic constant but an outcome of continuous metal-organic-microbe interactions.

-

As metastable phases, ferrihydrite and lepidocrocite spontaneously transform into more crystalline IONPs such as goethite and magnetite following Ostwald's rule of stages[17,46], following a dissolution-reprecipitation framework in ambient temperature near-neutral solutions[47,48]. At low pH (1.5–2.5), Fe(OH)3 clusters form lepidocrocite and goethite directly by Ostwald ripening, while higher pH (≥ 3.0) conditions favor ferrihydrite formation[49]. Metal ions, organics, and microbes can then promote or hinder transformation, as discussed in the following subsections.

Metal ion-induced ripening and phase transformations

-

The kinetics of transformation can be greatly promoted or hindered by the presence of aqueous ions. This subsection first discusses the acceleration of transformation by aqueous Fe(II), focusing on the role of 'labile Fe(III)' as a highly reactive intermediate species, before discussing the effects of cadmium (Cd), arsenic (As), and chromium (Cr) surface sorption and structural incorporation on transformation kinetics and pathways. Finally, the effects of silicon (Si) on transformation are discussed, focusing on Si-O-Fe bonding (Table 1).

Table 1. Effects of aqueous ions on Fe(II)-catalyzed ferrihydrite/lepidocrocite transformation

Ion Inhibitory effect Mechanism Impact on transformation pathway Redox behavior during transformation Cd2+[67−69] Strong inhibition at high concentrations Substitution into goethite > lepidocrocite; defect-related sorption Delays ferrihydrite transform to goethite/lepidocrocite; favors

ferrihydrite retentionNo significant redox change; immobilized by structural incorporation As(V/III)[75,77,92] Strong inhibition, especially As(V) Surface complexation and structural incorporation Stabilizes lepidocrocite, inhibits

goethite crystallizationAs(V) → As(III) (under reducing conditions); re-adsorption occurs Cr(VI)[81−83] Moderate inhibition Formation of Fe(III)-Cr(III) coprecipitates Enhances lepidocrocite/goethite formation if reduction is partial Cr(VI) → Cr(III), with Cr(V) intermediate; Cr(III) incorporated Si (H4SiO4)[85,89,91] Strong inhibition Surface complexation (Si–O–Fe), charge reversal Suppresses lepidocrocite/goethite/hematite crystallization; stabilizes ferrihydrite No redox role; purely structural/surface interference Mo(VI)[93] Dose-dependent effect Surface-sorbed; potential incorporation Low Mo: favors magnetite; high Mo: favors goethite Reduced to Mo(IV) (e.g., MoO2); retained in solid Co2+[94] Inhibits magnetite formation Incorporated into tetra-/

octahedral Fe sitesAlters Fe(II)-to-magnetite pathway; enhances goethite instead Incorporated without redox change; modifies magnetic properties Ce(III)[95] No inhibition; facilitates retention Strong association with Fe mineral surface Promotes Ce retention; less release Oxidized to Ce(IV) during transformation Sb(V)[96] Minor inhibition Adsorption/incorporation

in Fe mineralsNo significant pathway shift No redox change; remains Sb(V), structurally trapped V(V)[97] Inhibitory at high concentrations Substitution into Fe2+/Fe3+ sites Favors goethite over magnetite V(V) → V(IV)/V(III) reduction under microbial mediation The transformation of ferrihydrite and lepidocrocite is greatly catalyzed by the presence of aqueous Fe(II)[50]. In near-neutral solutions (pH ~7.0), Fe(II) catalyzes the transformation of ferrihydrite predominantly into lepidocrocite and goethite, while lepidocrocite has been reported to transform into magnetite[7,51]. The mechanisms of Fe(II)-catalyzed transformation have been described following a dissolution-reprecipitation framework: aqueous Fe(II) sorbs to the Fe oxyhydroxide surface, injecting electrons into the mineral phase through Fe(II)-ferrihydrite sorption complexes during the oxidation of the sorbed Fe(II) fraction, and the transfer of electrons to structural Fe(III) units leading to their reductive dissolution[52−54]. This oxidized sorbed Fe(II) is more loosely bonded than structural Fe(III) species[55], as demonstrated by its near-selective removal using an Fe(III) complexing agent (xylenol orange disodium salt, termed 'XO extractions')[17], such that its presence substantially increases the overall extent of chemical lability of Fe(III) in the system relative to solely structurally bound Fe(III). In turn, this chemically labile oxidized Fe(II) is broadly referred to as 'labile Fe(III)', where higher Fe(II) concentrations may promote labile Fe(III) formation[16].

Early works assumed labile Fe(III) to be a more reactive form of ferrihydrite[52]. However, through studying the early stages of Fe(II)-catalyzed ferrihydrite transformation that precede the formation of crystalline phases detectable by conventional laboratory powder X-ray diffraction (XRD), Mössbauer spectroscopy with XO extractions and electron microscopy were used to correlate labile Fe(III) formation with the emergence of quasi two-dimensional, lepidocrocite-like nanosheets with increased magnetic ordering relative to ferrihydrite. Based on this, labile Fe(III) was proposed to be an intermediate phase with a 'proto-lepidocrocite' structure that resembled individual layers of lepidocrocite lamellae[56,57]. This view was corroborated by earlier reports of lepidocrocite crystallisation preceding the emergence of goethite[50,58].

Based upon initial observations of: (1) labile Fe(III) amounts first increasing with time before subsequently decreasing once crystalline transformation products emerged (detectable by micro-XRD); and (2) labile Fe(III) consumption rates correlated with goethite formation rates (pseudo-first order rate constants), it was proposed that labile Fe(III) concentrations controlled transformation product crystallization following classical nucleation theory (CNT)[17]. This was later supported by experiments that varied the Fe(II) solution volume to ferrihydrite mass ratio, wherein the rate of ferrihydrite transformation into lepidocrocite/goethite was shown to be a function of solution supersaturation with respect to labile Fe(III) rather than the system total labile Fe(III) amounts[16]. Alongside isotope tracer (57Fe) experiments showing that these tracers were rapidly 'buried' in highly crystalline phases during transformation[56], likely following a dissolution-reprecipitation mechanism, these results showed that labile Fe(III) acts as a reactive, intermediate phase during transformation product formation.

The pathways of the lepidocrocite to magnetite transformation process remain debated: some authors have observed that a green rust (a mixed-valence Fe oxyhydroxide) intermediate forms, while others reported direct transformation[51,59]. Usman et al. reported that green rust is more likely to form as an intermediate in neutral to slightly alkaline, Fe(II)-rich, anoxic environments[60].

Temperature and ionic composition also control IONP transformation[61,62]. A previous investigation studied the impact of temperature on the ferrihydrite transformation rate, and found that ferrihydrite transformed to hematite and goethite as the temperature increased from 25 to 100 °C[61]. Different ionic compositions were also studied for their impact on IONP transformation. Ferrihydrite predominately transformed to lepidocrocite in Cl– medium, while to goethite in SO42– and HCO3– medium, due to the ionic control on (FeO3[OH]3) octahedral spatial arrangement and the suppression of lepidocrocite nucleation[63,64]. The transformation rate in the Cl– system was faster than that in the SO42– system[63].

Recent works have shown that the pathways and kinetics of Fe(II)-catalyzed transformation depend upon labile Fe(III) concentrations following CNT[16]. In turn, factors which control labile Fe(III) concentrations and production rates, such as Fe(II) concentrations or ferrihydrite amounts, control transformation pathways and kinetics[16,51]. Notably, Fe(II)-ferrihydrite electron transfer rates are a function of ferrihydrite particle redox potential. Ferrihydrite with varying degrees of crystallinity is ubiquitously present in natural environments. Low-crystallinity ferrihydrite typically precipitates under ambient temperature conditions, whereas high-crystallinity ferrihydrite tends to form at elevated temperatures. As redox potentials decrease with increasing particle crystallinity, less crystalline particles are associated with the rapid transformation of ferrihydrite to lepidocrocite/goethite. Contrastingly, more crystalline ferrihydrite particles, which have higher energy barriers to lepidocrocite nucleation, undergo transformation into goethite/magnetite[7]. This control of labile Fe(III) concentrations also explains observations of magnetite formation typically only at higher Fe(II) concentrations and the dependence of the goethite to lepidocrocite ratio at a given time on Fe(II) concentrations[58]. Labile Fe(III) concentrations have also been proposed to control Ostwald ripening processes, where the appearance of lath-shaped goethite particles at the expense of smaller acicular goethite particles was proposed to indicate a dissolution-reprecipitation process[7].

Ferrihydrite acts as an important sorbent of contaminant (e.g., heavy metals), and nutrient species in soils[65], where the association of aqueous species with ferrihydrite affects its properties and hence transformation pathways. Further, the resulting crystalline phases control the release, sorption, structural incorporation or physical trapping (the latter two as immobilization) of these species during transformation. For example, the association of Cd-treated ferrihydrite with kaolinite was shown to decrease particle sizes and increase redox potentials, resulting in more reactive ferrihydrite which transformed (Fe[II]-catalyzed) into goethite and lepidocrocite, with larger fractions of Cd immobilized through structural incorporation into goethite than into lepidocrocite (Table 1)[66].

Early works on Cd-treated ferrihydrite focused on heat-catalyzed transformation in aqueous solutions (hydrothermal transformation): with increasing aqueous Cd concentration, Cd incorporation into goethite and hematite distorted their unit cells until goethite formation was entirely suppressed[67]. Similarly, the addition of Cd during ferrihydrite precipitation slowed subsequent Fe(II)-catalyzed ferrihydrite and lepidocrocite transformation rates as a function of the Fe(III)/Cd ratio[68]. Cd is predominantly incorporated into lepidocrocite and goethite during Fe(II)-catalyzed transformation, but may also be structurally incorporated into magnetite at higher Fe(II) concentrations. Further, Cd is also associated with an increase in crystalline phase defect fractions, increasing subsequent aqueous Cd uptake through sorption[69]. Further, where pre-existing goethite or lepidocrocite were added, ferrihydrite transformation into that mineral was promoted and larger aqueous Cd fractions were associated with the resulting substantially decreased surface area[70]. Indeed, the release of ferrihydrite-sorbed Cd was reported to be hindered where the transformation (hydrothermal) of Cd-treated ferrihydrite was inhibited by the presence of clay minerals (kaolinite and montmorillonite)[71].

Arsenic (As) is commonly present alongside Cd as an environmental contaminant (e.g., acid mine drainage sites), where both As(V) and Cd(II) can strongly inhibit Fe(II)-catalysed transformation (Table 1). However, As(V) was reported to have a stronger effect on secondary mineral crystallization, consequently inhibiting the release of Cd(II) during transformation[72]. This stronger effect for As might relate to a faster rate of As-ferrihydrite complexation than pure ferrihydrite precipitation[73]. Indeed, As-treated ferrihydrite transformation rates (hydrothermal, 40 °C) have been shown to strongly decrease with increasing solid-associated As concentrations[74]. Both As(V) and As(III) can inhibit Fe(II)-catalyzed transformation: As(V) was reported to inhibit goethite formation to stabilize lepidocrocite, while As(III) initially was associated with a weaker inhibitory effect (goethite formation) which intensified following oxidation to As(V) (lepidocrocite preservation) (Table 1)[75]. In natural anoxic groundwater systems, the reduction of As(V) to As(III) and its release during the reductive dissolution of ferrihydrite are associated with the subsequent uptake of As(III) into secondary minerals during their crystallization through Ostwald ripening[76]. At low As concentrations, the rates of Fe(II)-catalyzed ferrihydrite and lepidocrocite transformation and goethite recrystallization were unaffected by As, but As was released from the surface of lepidocrocite faster relative to ferrihydrite and goethite[77].

Chromium (Cr) presents an important environmental contaminant, with the compositions of (Fe[III],Cr[III])(OH)3 coprecipitates depending upon bulk solution conditions and mineral surface properties for heterogeneous precipitation[78−80]. Fe(II) can reduce Cr(VI) to Cr(III), with a strong pH dependence (minimum at pH 4 to 5)[81]. In Fe(II)–Cr(VI) ferrihydrite sorption experiments, the reduction of Cr(VI) to Cr(III) by Fe(II) resulted in a larger fraction of Cr remaining following desorption through forming Fe(III)–Cr(III) coprecipitates at the ferrihydrite surface (hydroxides) or in transformation products (lepidocrocite and goethite)[82]. Co-precipitates can incorporate Cr(VI) where reduction is incomplete, with Cr(VI) also being structurally incorporated into hematite during the hydrothermal transformation of Cr-ferrihydrite[83].

While silicon is a metalloid, silicates, and associated colloids are ubiquitous in natural settings[84], and natural ferrihydrite is commonly associated with relatively high (up to 9%) silicon (Si) concentrations[65]. Early work by Schwertmann and colleagues noted that the surface binding of orthosilicic acid (H4SiO4) at sufficiently high Si/Fe(II) molar ratios can inhibit crystallization and preserve ferrihydrite[85,86]. Indeed, the heat-catalyzed (hydrothermal), Fe(II)-catalyzed and uncatalyzed ferrihydrite transformation rate, alongside clay minerals, diminishes with increasing aqueous Si concentrations arising from clay mineral dissolution[71,87,88]. In Fe(II)-catalyzed systems, this effect was attributable to slowed electron transfer due to the promotion of physisorption through changes in ferrihydrite surface charges with silica incorporation (from positive to negative) and Si-O-Fe bonds limiting Fe(II)-structural Fe(III) interactions (Table 1)[89−91]. In natural environments, these silica-ferrihydrite interactions effectively stabilize ferrihydrite[86].

Organic ligand-mediated transformation pathways

-

Fe-(oxyhydr)oxide-organic ligand interactions have been demonstrated to profoundly affect transformation kinetics and pathways, with these effects particularly sensitive to OM ligand species, number, MW, and concentration. This section focuses on organic ligand binding effects on ferrihydrite transformation.

Carboxyl groups can strongly bind Fe in INOPs through ligand exchange mechanisms to form carboxylate-Fe bonds, with the number of carboxylate-Fe bonds with ferrihydrite correlated with molecular carboxyl richness[98]. This bonding can lead to the stabilization of otherwise metastable phases, inhibiting the transformation of ferrihydrite and lepidocrocite (Table 2)[27]. For example, increasing the molar carbon to Fe(III) (C/Fe) ratio at high Fe(II) concentration (5.0 mM) for ferrihydrite-polygalacturonic acid coprecipitates inhibited magnetite formation, while at low Fe(II) concentrations (0.5 mM) increasing the C/Fe ratio eventually inhibited goethite and lepidocrocite crystallization (Table 2)[28]. However, using NOM (Ultisol), lepidocrocite formation was instead observed to be relatively promoted at 0.2 and 2.0 mM Fe(II) as the crystallization of goethite and magnetite were suppressed by ligand binding effects[11]. Such results highlight that the effects of carboxyl ligands on ferrihydrite transformation cannot be described solely using a C/Fe ratio.

Table 2. Effects of organic matter on Fe(II)-catalyzed ferrihydrite transformation

OM property Effect on transformation Mechanism Carboxyl group richness[27,98] Inhibits Fh and Lp crystallization; stabilizes Fh Strong Fe–carboxylate binding; complexation with labile Fe(III) C/Fe molar ratio[28,114] Higher C/Fe inhibits Gt and Mt formation; favors Fh retention Controls surface coverage and Fe(II) interaction; not sufficient alone to predict outcome Molecular weight (MW)[30,31] Low MW + carboxyl-rich → inhibit; High MW →

promote Gt formationBinding affinity to labile Fe(III) varies with MW; steric/bridging effects at high MW Labile Fe(III) complexation[17,56,57] Prevents nucleation/crystallization of secondary minerals Fe(III)-ligand complexation inhibits polymerization Surface site blocking[28,101] Minor/secondary effect in some systems Blocks Fe(II) adsorption and electron transfer Thiol (–SH) and amino (–NH2) ligands[102,103] Promote Gt over Hm via dissolution–reprecipitation Reduce surface Fe(III) and shift transformation pathway Sulfide (S2–) + OM systems[105,106] OM modulates identity of Fe–S minerals formed (e.g., greigite vs pyrite) Carboxyl ligand effects on Fe–S–OM interactions Variations in organic properties, such as MW or carboxyl richness, and initial mineral phase properties can result in seemingly paradoxical changes when only C/Fe ratios are examined. Zhao et al. reported that the binding strength of carboxylate ligands onto ferrihydrite correlated with the inhibition of transformation during hydrothermal aging (75 °C), where organic carbon (pentanoic acid, hexanedioic acid, and butane 1,2,4-tricarboxylic acid) with low and high binding strengths became increasingly and decreasingly mobile, respectively, with time (0.1 M NaOH desorption). Such an effect was attributed to the strength of OM binding controlling mineral properties following aging, which, in turn, controlled the extent of OM preservation, but the exact underpinning mechanisms were not discussed[29]. Similar effects have also been reported for Fe(II)-catalyzed ferrihydrite transformation, where this organic inhibitory effect on transformation diminished with increasing MW of OM and a correlation with carboxyl richness was only observed at low MWs[30,31]. Indeed, high MW OM enhanced transformation to goethite, while lepidocrocite transformation was slowed with increasing carboxyl richness at low MW. This effect has been proposed to be related to the number of binding sites per molecule, affecting the strength of organic-mineral binding, with steric constraints also allowing larger molecules to act as bridges to aggregate numerous particles to promote goethite formation with high defect concentrations[30].

Studying Fe(II)-catalyzed ferrihydrite transformation in the presence of citrate, Sheng et al. showed that labile Fe(III)-carboxylate complexation disrupted polymerization for secondary mineral crystallization[99]. Indeed, results for ferrihydrite-polygalacturonic acid coprecipitates were inconsistent with surface site blocking limiting Fe(II)-ferrihydrite interactions[28]. Such an effect on labile Fe(III) is also supported by observations of a poorly crystalline proto-lepidocrocite, postulated to be associated with labile Fe(III) (Table 2)[28,56,57]. Further, isotope tracer studies of Fe(II)-catalyzed transformation observed that complete atom exchange could be achieved without measurable crystalline phases in the presence of carboxyl ligands, showing that the inhibition of electron transfer is not a requirement for inhibiting the crystallization of lepidocrocite or goethite[100]. However, studies of the Fe(II)-catalyzed transformation of surface soils showed that Fe(II)-soil mineral electron transfer was inhibited by the presence of OM for goethite but not ferrihydrite, attributing this effect to soil OM blocking surface sites to inhibit Fe(II)-mineral surface associations (Table 2)[101].

While less studied than OM with carboxyl ligands, thiol (R-SH), and amino (R-NH2) ligands can coordinate with Fe(II) and Fe(III) metal centers[102]. In the hydrothermal aging (70 °C) of L-cysteine sorbed to ferrihydrite, thiol ligands were proposed to reduce structural Fe(III) at ferrihydrite surfaces to increase surface reactivity and promote goethite formation following a dissolution-reprecipitation pathway[103]. Such an effect was weak at low cysteine to Fe ratios (< 0.2 mol/mol), but was shown to gradually shift ferrihydrite transformation from a solid state reorganization pathway (hematite formation) to a dissolution-reprecipitation pathway (goethite formation) with increasing cysteine to Fe ratios[104].

Redox reactions between ferrihydrite and aqueous sulfide (S[-II]) can lead to ferrihydrite transformation through a dissolution-reprecipitation pathway similar to Fe(II)[105], and OM can inhibit secondary mineral crystallization in this system (Table 2)[27]. ThomasArrigo et al. studied the S(-II)-catalyzed transformation of ferrihydrite alongside organic ligands (ferrihydrite coprecipitates), reporting that smaller carboxylic organics (galacturonic acid and citric acid) hindered transformation to a greater extent than larger carboxylic organics (polygalacturonic acid). Further, OM modulated the identity of the formed minerals, with pyrite or greigite ultimately forming depending upon the presence of excess carboxyl groups[106].

The presence of multiple functional group types can strongly affect organic-IONP interactions, and in turn could affect transformation processes. For example, Eitel & Taillefert reported that the rate-limiting step of ferrihydrite reductive dissolution by thiol ligands changed from surface species coordination for amine-bearing thiol ligands (e.g., cysteamine) to electron transfer for carboxyl-bearing thiol ligands (e.g., cysteine). Further, increasing the number of amine and carboxyl groups (e.g., glutathione) increased the overall extent of reductive dissolution[107]. Similarly, Liu et al. reported a dual effect of functional groups on the heat-catalyzed transformation of lignin-ferrihydrite coprecipitates, whereby: (1) phenolic or primary alcohol groups were postulated to be oxidized as lignin facilitated the reductive dissolution of ferrihydrite and subsequent Fe(II) catalyzed transformation: and (2) carboxyl and phenolic hydroxyl groups blocked ferrihydrite surface sites and bound Fe(II) and labile Fe(III) species to inhibit transformation. The relative importance of these two processes, and hence the overall effect of lignin on transformation, was dependent upon these organic oxidation and organic-Fe species binding mechanisms as a function of conditions (e.g., pH and organic concentration)[108]. Further, from previous X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) studies of Fe(III)/Fe(II)-SRNOM interactions, it was shown that whilst NOM functional groups can act as redox buffers or complex with Fe(II)/Fe(III) species, complexation by carboxyl groups principally occurred over Fe(II)/Fe(III) binding by other functional group types[109,110]. Such results indicate that multiple functional groups can synergistically or competitively affect transformation processes to an extent dependent upon the relative importance of the associated organic-Fe species interactions, where carboxyl-Fe species interactions in particular could be expected to be dominant over interactions with other functional group types during transformation.

The presence of OM can also affect contaminant and nutrient-ferrihydrite interactions and hence the behavior of aqueous ions during transformation. For example, while humic acid hindered the Fe(II)-catalyzed transformation of ferrihydrite through carboxyl/hydroxyl group-Fe binding effects, the occupation of surface sites by humic acid also limited Cd sorption for humic acid-ferrihydrite-Cd coprecipitates both before and after transformation[111]. The inhibiting effect of OM on ferrihydrite transformation also controls metal ion sorption and incorporation. Notably, the hindered transformation of Cr-ferrihydrite coprecipitates by OM derived from rice straw reduced the fraction of readily extractable Cr(III) by limiting its mobilization during the reductive dissolution of ferrihydrite[112]. OM-metal complexation and redox reactions can also affect contaminant/nutrient mobility during transformation: during the Fe(II)-catalyzed transformation of Cr(VI) adsorbed to ferrihydrite-humic acid coprecipitates at 70 °C, large Cr fractions were immobilized through the reduction of Cr(VI) to less soluble Cr(III) by both Fe(II) and humic acid and the formation of humic acid carboxyl group-Cr complexes, alongside Cr structural incorporation into transformation products (goethite and hematite) and Cr(III)-Fe(III) coprecipitates[83]. The uptake of Cr through either adsorption or structural incorporation (substitution or occlusion) also depends upon the transformation product phase assemblages, which are in turn partly controlled by the presence of OM. For example, simple carboxylic acids (e.g., pentanoic acid and hexanedioic acid) inhibited goethite formation during Fe(II)-catalyzed ferrihydrite transformation, thereby lowering solid-incorporated Cr amounts and increasing Cr mobility. Such an effect was dependent not only upon the pH of transformation, but also the carboxyl richness of the OM[113].

Aqueous ions and OM sorption can also yield similar inhibitory effects on ferrihydrite transformation processes, suggesting synergistic ion-OM effects can control transformation. For example, Si and NOM were reported to both inhibit ferrihydrite transformation through the same mechanisms of limiting Fe(II) sorption and transformation product crystallization[90].

Microbial-driven transformations

-

Bacteria are ubiquitous and found in large numbers in soil and marine mud (e.g., 108 cells/g) and in lake and river waters (e.g., 105 cells/mL)[115−117]. The coexistence of bacteria and IONPs (e.g., ferrihydrite) is widespread in nature and has been observed in many geochemical environments, such as rivers[118,119], lakes[120,121], and marine sediments and detritus[115,122,123].

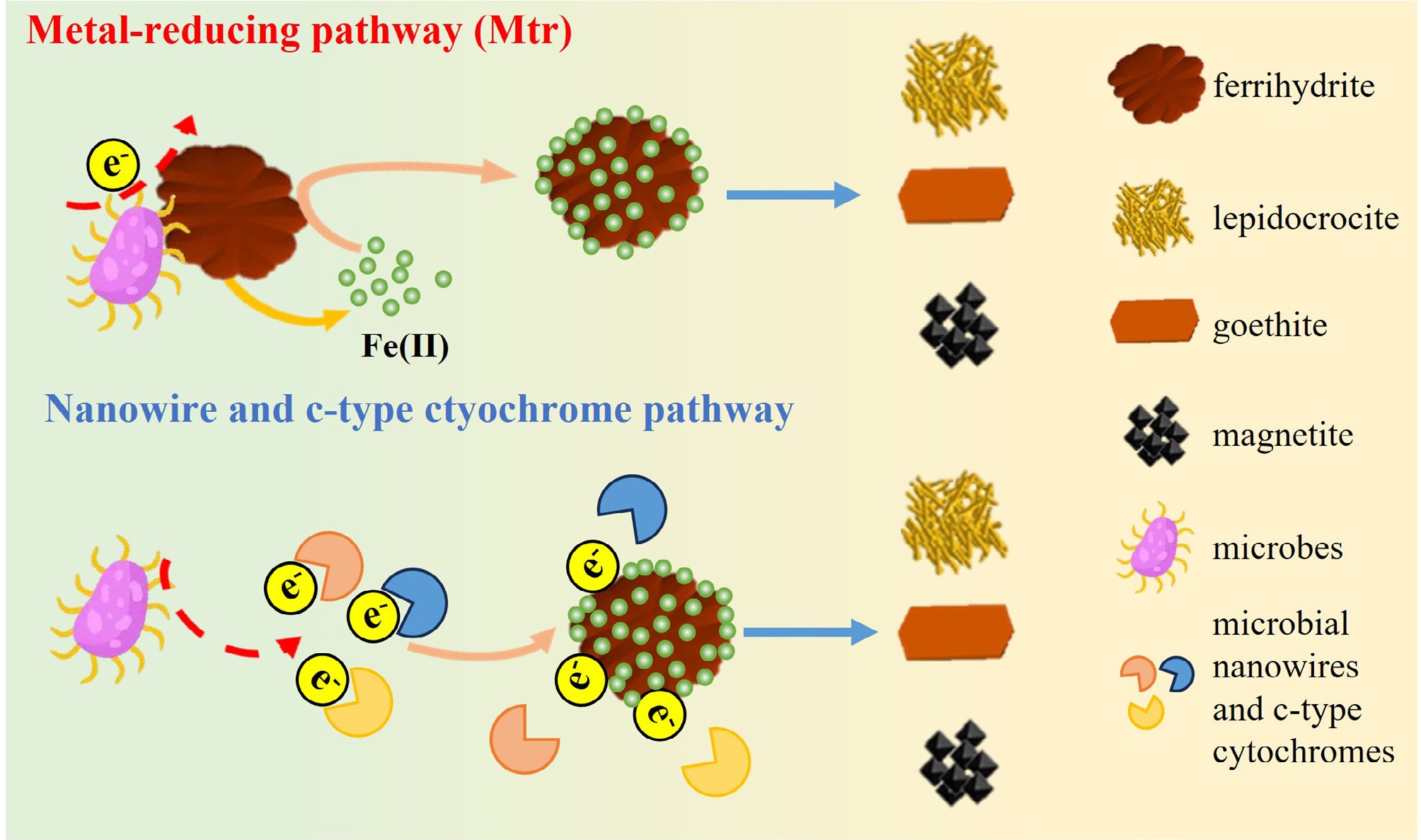

Dissimilatory metal-reducing microorganisms, such as Geobacter sulfurreducens[124] and Shewanella oneidensis MR-1[125,126], can consume OM (e.g., acetate) or hydrogen (H2) to induce Fe(III) dissolution and reduction[127]. OM or H2, act as electron donors in this system[127]. As electron transfer between microorganisms and extracellular minerals is not able to proceed given the physical permeability or electrical conductivity of the microbial cell envelope, strategies such as microbial nanowires and c-type cytochromes have been evolved by microorganisms to exchange electrons with Fe ions in minerals (Fig. 3)[117,128]. For example, G. sulfurreducens uses various sets of proteins (e.g., porin–cytochrome proteins) to transfer electrons to the cell surface[129]. S. oneidensis MR-1 is hypothesised to use a metal-reducing (Mtr) pathway to transfer electrons to Fe(III)-bearing mineral surfaces[130]. If cell and mineral surfaces are distant, unique mechanisms, such as nanowires and OmcS (a multiheme c-type cytochrome that is related to nanowires), have been evolved by microorganisms (G. sulfurreducens) to transfer electrons[128,131,132]. In this process, Fe(III) from Fe minerals acts as an electron acceptor, and is reduced to Fe(II) (Eq. [1])[124,133]:

$\rm Acetate^- + 8 Fe(III) + 4 H_2O \to 2HCO_3^- + 8Fe(II) + 9H^+$ (1) The reduced Fe(II) is expected to catalyse the transformation of poor crystalline ferrihydrite to more metastable, crystalline Fe mineral phases, such as lepidocrocite, goethite, and magnetite[52,134]. In this system, the concentration of solid-associated Fe(II) is a key contributor to the formation rates of secondary minerals, and determines their identity. Low solid-associated Fe(II) concentrations enhance lepidocrocite growth, while the rapid-uptake of high concentrations of solid-associated Fe(II) promotes goethite growth rates[52]. If the solid-associated Fe(II) concentration on the mineral surface is high enough (e.g., ≥ 1 mM/g ferrihydrite), ferrihydrite can be induced to transform into magnetite as an Fe(II)-bearing end-product of mineral transformation[62,58,125].

Metal ions can impact microbially-mediated ferrihydrite mineral transformation. For example, previous studies investigated vanadium (V), arsenic (As), cerium (Ce), and cobalt (Co) doped ferrihydrite in the presence of bacteria[94,95,97,135,136], and observed that goethite formation occurred at high metal concentrations, instead of magnetite, due to a metal toxicity effect on ferrihydrite to magnetite reduction, resulting in metal-doped magnetite formation only at low metal concentrations[97,136]. The doped metals can also change the properties of newly formed minerals. For example, high Co amounts ([Co]/[Fe] = 50%) were reported to decrease magnetite particle sizes to 4 nm whilst increasing effective anisotropy and coercivity[94]. Co and V were observed to substitute for Fe2+ in the tetrahedral site and hence were predominantly incorporated in octahedral coordination[94,97].

For metal-sorbed ferrihydrite (e.g., molybdenum [Mo], antimony [Sb]), the addition of Geobacter sulfurreducens showed similar results: high concentrations of added metals led to goethite formation and low metal levels resulted in magnetite formation[96] due to sufficient Fe(II) concentrations at the mineral surface[93]. Both metal-doped and metal-sorbed ferrihydrite showed that the concentration of Fe(II) in solution increased over time, despite no additions of Fe(II), indicating that bacteria played an important role in reducing Fe(III) to Fe(II)[93−97]. However, the Fe(II)/Fe(III) ratios in minerals presented similar results regardless of low or high metal concentration[93].

The Fe mineral transformation process, in turn, is able to reduce or oxidise the doped or sorbed metals. For example, Mo(VI), As(V), V(V), Sb(V), and uranium (U[VI]) reduction to lower valence metals were observed in the studies of microbially-mediated ferrihydrite phase transformation[92,94,96,97,135−138]. However, the oxidation of Ce(III) to Ce(IV) during microbially-mediated ferrihydrite transformation was observed, and the amounts of oxidised Ce(IV) increased with added Ce(III) concentration[95]. Microorganisms can play a key role in the mobilisation of metals in sediments, either through reducing metals to more insoluble or more soluble species, such as Mo(VI) reduction to Mo(IV)O2[93], U(VI) to U(IV)O2[137,138], As(V) to As(III)[92], V(V) to V(IV)/V(III)[97], or through inhibiting the release of the metal, such as Ce, into solution due to strong associations with Fe minerals during bio-induced ferrihydrite mineral transformation[95]. This strong association with the Fe solid phase can prevent a change in the oxidation state of the doped metals, e.g., Sb(V), indicating strong surface adsorption or structural incorporation with Fe minerals[96].

In addition to metal ions, OM can also influence microbially-mediated Fe mineral transformation processes by affecting ferrihydrite properties or bacteria-Fe mineral surface contact. Through studying the microbially-mediated (Geobacter bremensis and Shewanella oneidensis MR-1) transformation of ferrihydrite either coprecipitated or treated (surface adsorption) with soil OM, Eusterhues et al. and Cooper et al. showed that, at a given OM concentration, OM-ferrihydrite coprecipitates underwent faster reduction than ferrihydrite with surface-sorbed OM due to the smaller crystallite sizes and poorer crystallinity of the former[139,140]. Further, low OM concentrations enhanced siderite formation but suppressed goethite formation, which was attributable to reduced bacteria-ferrihydrite surface contact caused by OM[139]. Similarly, OM can also control the extent of ferrihydrite particle aggregation: increased particle aggregation for ferrihydrite suspensions mixed with humic acid was associated with decreased exposed ferrihydrite surface areas, which in turn limited ferrihydrite-bacteria contact and decreasing the amounts of reduced ferrihydrite in bacteria (Shewanella oneidensis MR-1)-humic acid-ferrihydrite transformation experiments[141]. While Poggenburg et al. confirmed that ferrihydrite reduction mediated by Geobacter metallireducens in ferrihydrite-NOM coprecipitates was a function of particle size and aggregation, reduction by Shewanella putrefaciens was instead shown to be a function of the amount of electron shuttling molecules (NOMs), showing a dependence on microbe type[142].

For the microbially-mediated transformation of metal ion-OM-ferrihydrite coprecipitates, redox processes involving both metal ions and OM can control the transformation behavior. For example, Hu et al. studied the transformation of fulvic acid-Cr(VI)-ferrihydrite coprecipitates mediated by Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. They reported that while carboxyl and hydroxyl groups in OM and on microbes can bind Cr(VI), observable transformation did not occur prior to complete Cr(VI) reduction due to redox reactions with Fe(II) produced through microbial interactions, yielding Cr(III) and Fe(III). This Cr(III) could then be structurally incorporated into transformation products (goethite and magnetite), where the nanoporosity of these transformed phases preserved OM with a higher oxidation state than OM sorbed to the mineral surfaces; highly aromatic OM readily underwent mineral surface sorption or was decomposed microbially[143]. Such results highlight the complex interplay between Fe minerals, aqueous species, OM, and microbes that likely occurs in natural systems.

Overall, microbially-mediated Fe mineral transformation has an important role in controlling the mobility of heavy metals in a variety of geochemical systems, and in turn potentially affects the transport and fate of heavy metal pollutants in the environment.

-

This review emphasizes that the stability of IONPs in the environment, defined here in terms of their colloidal aggregation state and the identity and crystallinity of their phase, is governed by interactions with metal ions, organic ligands, and microbes. Metal ions strongly influence IONP aggregation and phase transformation. In colloidal suspensions, electrolyte cations often neutralize surface charges or bridge particles, promoting aggregation, and the promotion effects increased with the increase of cation valence. For phase transformation, Fe2+ accelerates ferrihydrite transformation to more crystalline phases, whereas other metal dopants tend to stabilize amorphous phases and delay crystallization.

NOM can also modulate IONP stability. For IONP aggregation, organic effects largely correlate with the adsorbed mass: low adsorbed amounts of OMs can partially neutralize charge or create patchy charge attractions that lower the stability of IONPs, whereas high surface coverage imparts negative charge repulsion and steric hindrances, stabilizing nanoparticles. Moreover, nanoparticle aggregation could also be accelerated by a synergistic bridging effect of OM and divalent cations, such as Ca2+. For phase transformation, carboxyl-rich organics often inhibit phase transformation by binding to nanoparticle surface sites or the reactive intermediate Fe species that participate in crystallization, preserving metastable phases.

Microorganisms mediate IONP formation and stability through several processes. EPS coatings impart a negative charge and steric hindrances, keeping particles dispersed. However, incomplete surface coverage or cation bridging can induce aggregation. Under anoxic conditions, iron-reducing bacteria (FeRB) reductively dissolve Fe(III) phases, and generate Fe2+, which promotes ferrihydrite recrystallization into more stable minerals (e.g. magnetite or goethite). These biotic redox processes strongly affect IONP's longevity and can concurrently alter the fate of associated contaminants.

Outlook

-

Future progress in elucidating the environmental behavior of IONPs will depend on uncovering finer-scale mechanisms while bridging insights across disciplines and spatial scales. One major aspect is oriented aggregation (OA): in OA, particles adopt specific alignments before attachment, leading to ordered, compact aggregates with high structural coherence. This OA pathway is thus considered a particle-based crystallization process distinct from classical nucleation and growth. It contributes to the rapid coarsening of mineral nanoparticles under conditions where monomer-by-monomer growth is limited. Guyodo et al. observed the OA of nanogoethite rods, which enhanced magnetic ordering as particles merged into larger crystals[144]. For methods improvement, it will benefit from the integration of in situ and single-particle analytical techniques to capture nanoscale processes in real time. For example, synchrotron-based in situ X-ray microscopy and liquid-cell TEM can visualize aggregation and phase transformation dynamics under aqueous conditions, while single-particle ICP-MS enables time-resolved tracking of particle size, number concentration, and compositional evolution in complex matrices. Combining these emerging tools with conventional methods (e.g., DLS, TEM, and XRD) will provide a more comprehensive mechanistic understanding of the aggregation and transformation of IONPs in natural systems.

Also, assessing the correspondence between mechanistic insights gained from laboratory experiments and field studies will be a key aspect of applying these insights to complex natural settings. Our present understanding of the mechanisms of IONP aggregation and transformation as a function of geochemical conditions is largely derived from the results of highly controlled benchtop experiments (e.g., batch titrations or simplified analog waters). While valuable, these comparatively simplistic benchtop studies do not fully encompass the numerous, simultaneous conditions present in natural waters, soils and sediments, such as fluctuations in pH and temperature with time, numerous species in the waters, heterogeneous mixtures of OM, microbial communities, and numerous distinct mineral surfaces. From this perspective, there remains a need to validate the findings of these laboratory experiments using real systems, such as rivers or soil porewaters. Field studies have already suggested that these complex environments can result in mechanistic changes: for example, laboratory experiments suggested that a Ca2+-NOM bridging mechanism can predominantly drive IONP aggregation, but this effect may be modulated by a continuous input of NOM into the system, such as in rivers. Field studies with high monitoring frequencies or experiments in which environmental parameters (e.g., the presence of specific elements, NOM or microbes) are varied in enclosed or monitored areas may provide further valuable insights to address these apparent discrepancies. Moreover, integrating OM with inorganic IONPs represents an effective strategy for contaminant removal in engineered systems. Such combinations leverage the strong adsorption capacity of IONPs and the flocculation ability of organic polymers, providing a rational framework for designing water treatment processes that couple aggregation control with targeted pollutant capture.

Finally, a mechanistic understanding of how variations in geochemical conditions will affect the cycling of IONPs in complex natural environments will be required to predict the effects of strong perturbations, such as those associated with climate change. Changes in the elemental, organic and microbial inputs or the chemical properties (e.g., temperature or pH) of these systems would feasibly affect IONP stability. For example, anthropogenic salt inputs or freshwater salinization would be associated with changes in the dominant electrolyte inputs to the system (Na+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Cl−, etc.), with corresponding effects on the Fe-OM colloid surface charge neutralization and subsequent aggregation. From this perspective, Fe-OM colloids formed under low-salinity conditions might aggregate and subsequently settle as salinity increased. Similarly, changes in solution pH, such as those through the solubilization of increased atmospheric CO2 concentrations, would influence IONP aggregation through surface charges as well as transformation pathways. Understanding and predicting such effects will constitute an important aspect of mitigating the potential detrimental effects of changing IONP stability on the cycling of contaminants and nutrients.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Li Z, Goût TL, Hu Y; visualization and writing − original draft: Li Z; writing − review and editing: Goût TL, Zhang J, Zhao J, Liu J, Hu Y; resources and supervision: Hu Y. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 42177193 and 42107265), and the Yunnan Provincial Science and Technology Project at Southwest United Graduate School (Grant No. 202302AP370002).

-

All authors declare that there are no competing interests.

-

This review highlights how interactions with metal ions, organic matter, and microbes govern the environmental stability of IONPs.

Metal ions modulate IONP stability mainly through surface adsorption, charge neutralization, bridging, and lattice incorporation.

Organics regulate IONP aggregation and transformation via surface coating, bridging, and crystallization inhibition.

Microbial processes influence IONPs' stability through EPS-related effects, and Fe(II)-driven phase transformations.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Zhixiong Li, Thomas L. Goût

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li Z, Goût TL, Zhang J, Zhao J, Liu J, et al. 2025. Review on stability of iron (oxyhydr)oxide nanoparticles in natural environments: interactions with metals, organics, and microbes. Environmental and Biogeochemical Processes 1: e012 doi: 10.48130/ebp-0025-0013

Review on stability of iron (oxyhydr)oxide nanoparticles in natural environments: interactions with metals, organics, and microbes

- Received: 04 September 2025

- Revised: 07 November 2025

- Accepted: 18 November 2025

- Published online: 04 December 2025

Abstract: Iron (oxyhydr)oxide nanoparticles (IONPs), which are ubiquitous in many natural aquatic and soil systems, can strongly interact with nutrient and contaminant species in the environment through their large specific surface areas and redox reactivity, thus controlling the transport and fate of these elements. Following their formation, IONPs often undergo aggregation and phase transformation processes that collectively determine their long-term environmental stability. The aggregation of IONPs reduces colloidal stability and can lead to deposition and immobilization, whereas stable dispersed colloids can remain mobile and transport associated elements over long distances. The phase transformations of metastable, poorly crystalline IONPs (e.g., ferrihydrite) into more crystalline iron (oxhydr)oxides (e.g., goethite, hematite, and magnetite) profoundly alter particle properties and influence the retention or release of sorbed or structurally incorporated species. This review focuses on IONP aggregation and phase transformation as key processes controlling long-term IONP stability and critically examines how they are influenced by three common environmental factors: metal ions, organic matter (OM), and microbial activity. Metal ions can adsorb to IONP surfaces to modify surface charges or be structurally incorporated to affect IONP crystallography, thereby modulating inter-particle forces and transformation rates. OM can adsorb to IONP surfaces, and, depending on its concentration and molecular characteristics, it can either stabilize particles via electrostatic and/or steric repulsion, or promote aggregation through charge neutralization and bridging effects. Further, organic ligands can also often inhibit IONP transformation or alter transformation pathways by binding to reactive surface sites. Microbial activity influences IONP stability through extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) that coat or bridge particles, and through redox processes that generate or consume Fe(II), thereby either dispersing IONPs or accelerating their transformation into more stable mineral phases. This review summarizes present research on the effects of IONP interactions with metals, organics, and microbes on IONP aggregation and transformation. Such an understanding is crucial for predicting IONP stability and transport in the environment and the long-term cycling of associated organic and inorganic contaminants and nutrients.