-

Hydrogen, as a suitable substitute for fossil fuels, has attracted widespread attention owing to its renewable, clean, and carbon-free advantages[1,2]. Just as importantly, the calorific value of H2 is 39.4 kWh/kg, about 2.75 times greater than that of other liquid hydrocarbon fuels[3,4]. Hydrogen production in an efficient and continuous manner is highly desired for the sustainable development of clean energy[5−7]. Relying on the abundant proven reserves worldwide, and the technological advantages of a high H/C ratio, natural gas is widely utilized for generating H2[8−10]. Among methane-to-hydrogen production pathways, steam reforming of methane is a commercialized technology and a predominant industrial approach to producing hydrogen[11,12]. Nevertheless, the process suffers from complicated procedures, high energy consumption, and equipment costs. Moreover, carbon dioxide removal would also result in a substantial increase in the cost of producing hydrogen[13].

The decomposition of methane has garnered significant interest as a new route capable of generating hydrogen in one step. COx-free hydrogen could be theoretically produced by methane decomposition (CH4 → C + 2H2), which is potentially used in Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells (PEMFCs)[14,15]. Additionally, solid carbon material, the only byproduct, has a wide range of potential applications and economic value[16,17]. However, high temperatures > 1,200 °C are generally required to acquire reasonable hydrogen yields[18]. A significant reduction in decomposition temperature can be achieved by applying a catalyst, namely catalytic methane decomposition (CMD)[19]. Ni-based materials have been reported as promising candidates for CH4 activation, due to their low cost and high activity[20,21]. Nevertheless, carbon deposition during CMD would result in the coverage of the active sites, thus lowering catalyst performance permanently[22−24].

Catalyst supports are especially crucial for enhancing active component dispersion and remaining catalyst stability[25]. MgAl2O4 is an excellent spinel material used as catalyst support for its high mechanical strength, thermal stability, and chemically inert properties[26,27]. Nuernberg et al.[28] prepared Ni/MgAl2O4 catalysts for methane decomposition using a wet impregnation method with methane conversion reaching up to 37% at 550 °C. They also verified that carbon nanotube can be effectively produced under the catalysis of Ni/MgAl2O4. Yu et al.[29] conducted the H2-TPR measurements, and illustrated that the Ni/MgAl2O4 catalyst possesses a stronger metal-support interaction effect compared with Ni/MgO and Ni/γ-Al2O3, demonstrating high activity and superior sintering resistance in methane decomposition.

An alternate approach to enhancing the CMD performance involves the construction of bimetallic catalysts. The doping of noble metals [platinum (Pt)[30], ruthenium (Ru)[31], palladium (Pd)[32]] or transition metals (cobalt [Co][33], iron [Fe][34]) is reported to further promote the activity and the stability of Ni-based catalysts due to the structural and electronic rearrangements during alloy formation. The performance of Ni-Fe alloy-based catalysts has been reported and proven to be effective[35,36]. Chesnokov & Chichkan[37] performed the kinetic analysis regarding CMD reaction using Ni-Cu-Fe-based catalyst, and results demonstrated that the catalyst durability is strongly connected to the carbon growth and carbon diffusion. Compared to Ni0, the diffusion coefficient of carbon atoms in Fe0 is greater by three orders of magnitude, which allows faster diffusion of the carbon atoms through alloy particles. This can facilitate carbon transfer and offer prolonged stability[38]. Despite these positive studies, Ni-Fe catalysts still require further exploration to enhance its low-temperature catalytic activity as well as its resistance to sintering and agglomeration[39,40].

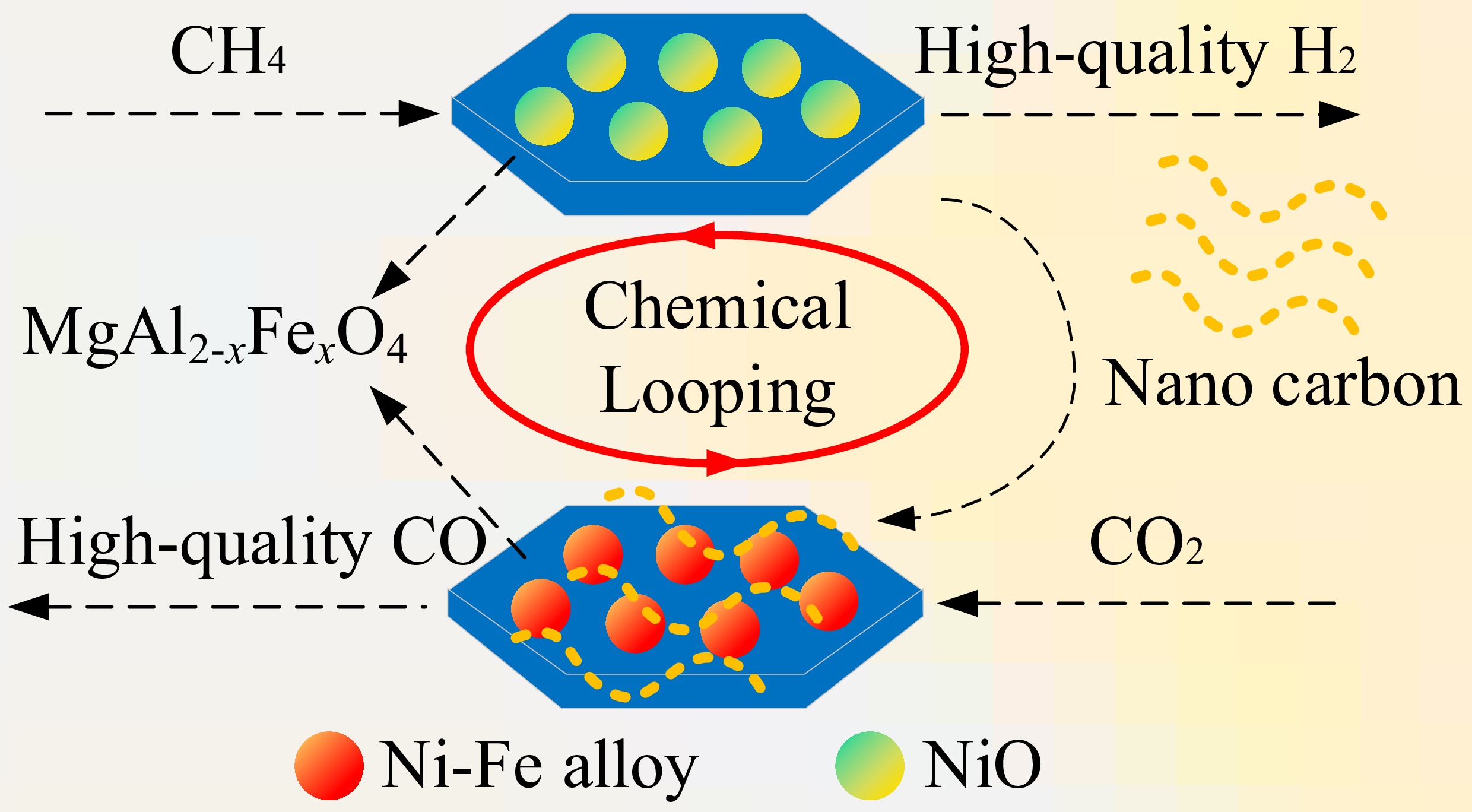

In this regard, we propose a strategy for strengthening low-temperature CMD via in situ Ni-Fe alloy formation by incorporating Fe into the magnesium aluminate lattice. Specifically, nickel catalysts supported by MgAl2-xFexO4 spinel were synthesized. On one hand, methane dissociation coupled with carbon dioxide reduction was conducted with the aim of resolving carbon deposition and catalyst deactivation; besides, the effects of FeO6 and AlO6 octahedral distortion on the CMD performances were explored with the aim of guiding the design of catalysts.

-

MgAl2-xFexO4 (x = 0.50, 0.75, 1.00, 1.25, 1.50, 1.75, 2.00) supports were prepared using a citric acid-induced sol-gel method as described previously[41]. Mg(NO3)2·6H2O, Fe(NO3)3·9H2O, Al(NO3)3·9H2O, and Ni(NO3)2·6H2O were purchased from Sinopharm. Citric acid (C6H6O7) was used as received from Aladdin. Typically, suitable metal nitrates, Mg(NO3)2·6H2O, Al(NO3)3·9H2O, and Fe(NO3)3·9H2O, were added into the deionized water according to the magnesium (Mg) : aluminium (Al) : Fe ratio of 1:(2-x):x (0.50 ≤ x ≤ 2.00). Citric acid was introduced as a complexing agent, maintaining a molar ratio of 1.3:1.0 between citric acid and total metal ions. The obtained solution was stirred at 80 °C in a water bath to a viscous state. The gel was dried at 150 °C for 12 h, and placed in a muffle furnace and calcined at 850 °C for 4 h under 2 °C/min. For synthesizing NiO/MgAl2-xFexO4 catalysts, an aqueous solution of nickel nitrate hexahydrate was introduced into a suitable amount of the prepared supports by incipient wetness impregnation with a NiO loading of 12 wt%[42,43]. Seven NiO/MgAl2-xFexO4 catalysts, x = 0.50, 0.75, 1.00, 1.25, 1.50, 1.75, and 2.00, were denoted as S1−S7 (Supplementary Table S1).

Catalyst characterizations

-

The metal concentrations in the fresh catalysts were determined using ICP-OES (PerkinElmer Avio500).

The phase composition of the catalysts was examined by X-ray diffraction (XRD) using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) at 40 kV and 40 mA. Diffraction data were collected over a 2θ range of 10−90° with a scan rate of 7°/min and an increment of 0.02°.

Nitrogen adsorption-desorption experiments were carried out at −196 °C to determine the specific surface areas and pore structural parameters of the catalysts. Prior to measurement, all samples were degassed at 200 °C for 6 h under vacuum. The BET method was applied to calculate surface areas, while the BJH approach was used to derive pore size distribution and total pore volume.

The redox properties of the samples were investigated by H2 temperature-programmed reduction (H2-TPR) using a Micromeritics AutoChem II 2920 instrument. In a typical procedure, 100 mg of sample was loaded into a quartz reactor, pretreated at 300 °C under an Ar flow for 30 min, and then cooled to 50 °C for 1 h. Once the baseline stabilized, the temperature was raised from 50 to 1,000 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min in a flow of 10 vol% H2/Ar (40 mL/min). H2 consumption was monitored using a thermal conductivity detector (TCD).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM, G2 60−300) was used to observe the morphology of fresh and spent catalysts. Elemental mapping for nickel (Ni), magnesium (Mg), Al, Fe, and oxygen (O) was performed via energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). Prior to imaging, all samples were dispersed in ethanol and sonicated for 30 min.

Raman spectroscopy (Renishaw inVia) was conducted to probe carbon-related features, with measurements repeated at least three times per sample. Spectra were collected using a 532 nm laser, 10 s acquisition time, and a scan range of 40–4,000/cm.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was employed to determine the surface chemical states of both fresh and used NiO/MgAlFeO4 catalysts. The measurements were conducted on a Thermo Scientific ESCALAB 250 system with a monochromatic Al Kα source (hv = 1,486.6 eV). Binding energies were calibrated using the C 1s peak at 284.8 eV as the internal standard.

Catalytic test

-

The catalytic activity experiments of the samples were carried out by a fixed-bed reactor (ID = 8 mm, length = 600 mm). Typically, a 0.400 g sample was placed at the center of the quartz reactor. Before the methane decomposition experiments, the reactor was flushed with 50 mL/min N2 for 20 min. Then, the reactor was heated to 600, 650, 700, 750, or 800 °C at 10 °C/min. Once the temperature was stabilized, the gas was switched to a 10 vol% CH4-N2 steam (N2 = 45 mL/min) with a duration time of 10~40 min. Similarly, the reactor was flushed by 50 mL/min N2 for 20 min before the carbon dioxide reduction experiment. The carbon dioxide reduction test was performed for 60 min under the atmosphere of 10 vol% CO2-N2 stream (N2 = 45 mL/min) within 750−900 °C. The protocol for the cyclic experiment was established as CH4 decomposition for 40 min (50 mL/min 10 vol% CH4-N2) → N2 purge for 10 min (50 mL/min N2) → carbon dioxide reduction for 50 min (50 mL/min 20 vol% CO2-N2) → N2 purge for 10 min (50 mL/min N2). The outlet gas mixture was detected by an INFICON Micro GC equipped.

Data analysis

-

The gas productivity (mmol/min), the outlet flow rate of gas i (mmol/min), CH4 conversion (%), and CO2 conversion (%) were calculated as follows:

$ {Y_{{\text{total}}}} = \dfrac{{Y{\text{(}}{{\text{N}}_{\text{2}}}{\text{,out)}}}}{{C{\text{(}}{{\text{N}}_{\text{2}}}{\text{,out)}}}} $ (1) $ Y{\text{(}}i{\text{,out)}} = {Y_{{\text{total}}}} \cdot C{\text{(}}i{\text{,out)}} $ (2) $ X\left( {{\text{C}}{{\text{H}}_{\text{4}}}} \right) = \dfrac{{Y{\text{(C}}{{\text{H}}_{\text{4}}}{\text{,in)}} - Y{\text{(C}}{{\text{H}}_{\text{4}}}{\text{,out)}}}}{{Y{\text{(C}}{{\text{H}}_{\text{4}}}{\text{,in)}}}} \times 100{\text{% }} $ (3) $ X\left( {{\text{C}}{{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}}} \right) = \dfrac{{Y{\text{(C}}{{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}}{\text{,in)}} - Y{\text{(C}}{{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}}{\text{,out)}}}}{{Y{\text{(C}}{{\text{O}}_{\text{2}}}{\text{,in)}}}} \times 100{\text{% }} $ (4) where, Ytotal denotes the total gaseous production rate; Y(i, in) and Y(i, out) represent the feeding rates of gas i and the production rate of gas i, respectively; C(i, out) is the concentration of generated gas i (i = N2, CH4, H2, CO, or CO2). X(CH4) and X(CO2) signify the methane and carbon dioxide conversion, respectively.

-

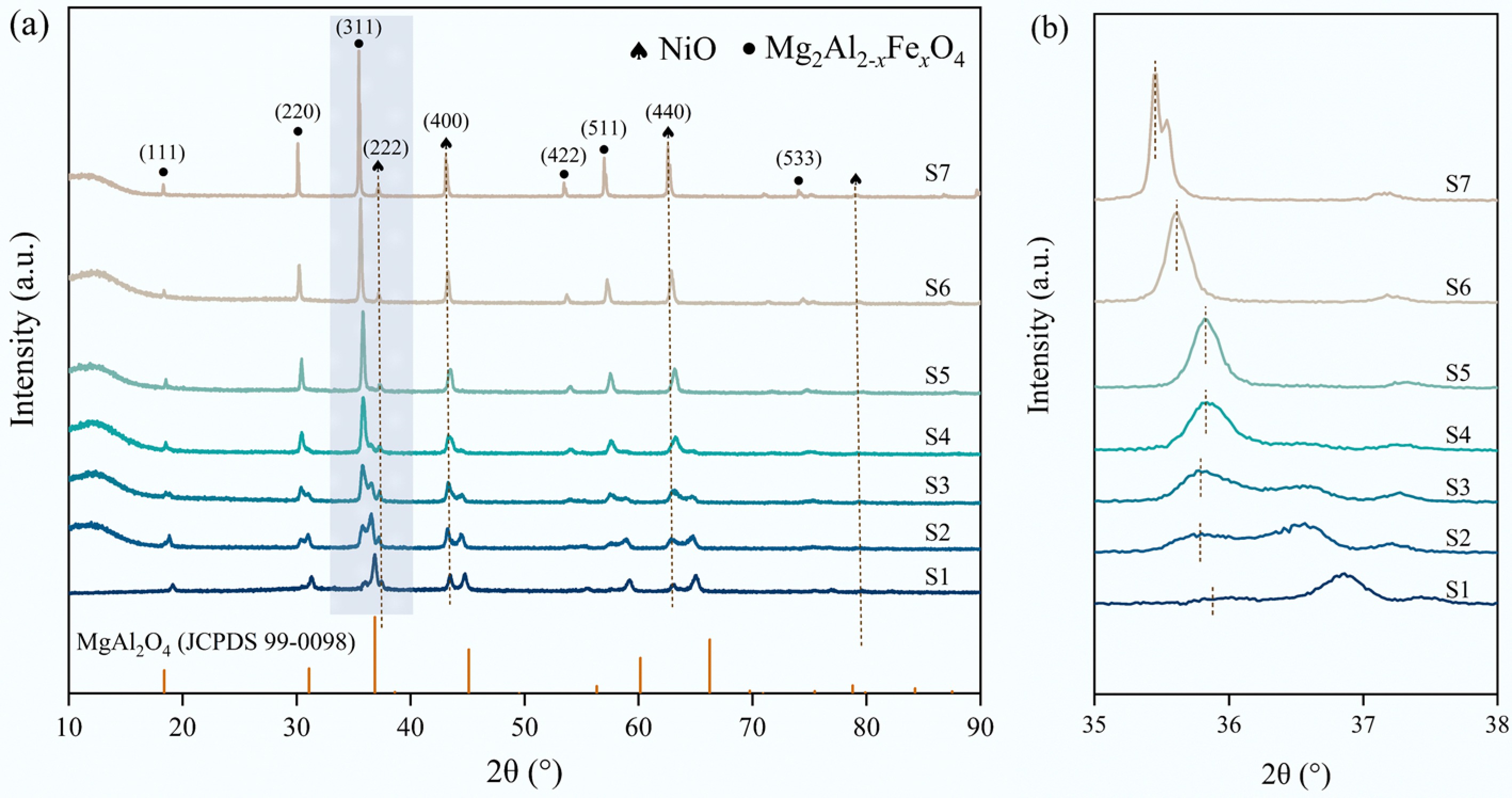

ICP-OES results indicated that the Fe content in the catalyst increased while the Al content decreased with the Fe doping amounts, which aligns with the theoretical ratios (Supplementary Table S2). XRD results are displayed in Fig. 1, aiming at clarifying the phase of the fresh NiO/

MgAl2-xFexO4 catalysts. The diffractions of MgAl2O4 were mainly located at 19.0°, 31.3°, 36.9°, 44.8°, 55.7°, 59.4°, and 65.2° (JCPDS 99-0098). All the fresh catalysts with different Fe doping ratios showed diffraction peaks around these angles without the detection of other impurities, preliminarily confirming the formation of MgAl2-xFexO4 after Fe incorporation. With the increase in the Fe doping amount, the peaks shifted to lower angles, attributing to lattice tensile strain caused by the substitution of Fe3+ (0.0645 nm) by Al3+ (0.0535 nm) in the spinel structure. Furthermore, three diffraction peaks (37.2°, 43.3°, and 62.9°) detected indicate the formation of NiO. The crystallite sizes of NiO were analyzed based on the Scherrer formula (Table 1). It is revealed that appropriate Fe doping is beneficial to maintain the small crystalline size of NiO. However, excessively high Fe doping results in an increase in the NiO crystalline size. In this regard, S3 and S4 catalysts are speculated to perform higher catalytic activity and stability during methane dissociation.Table 1. Textural properties of the fresh catalysts

Sample BET surface

area (m2/g)Pore volume (cm3/g) Average pore diameter (nm) NiO crystallite size (nm) S1 4.7 0.016 7.9 27.0 S2 3.6 0.012 5.0 20.3 S3 2.4 0.011 12.5 17.1 S4 3.4 0.016 12.6 16.0 S5 2.8 0.013 3.9 22.9 S6 2.3 0.010 3.5 34.1 S7 1.8 0.004 3.2 44.0 Textural properties of the fresh catalysts are presented in Table 1. The S1 sample possesses the largest BET surface area and pore volume, while a gradual decrease could be observed in surface area and pore volume with the further increase in the Fe doping amount[44,45].

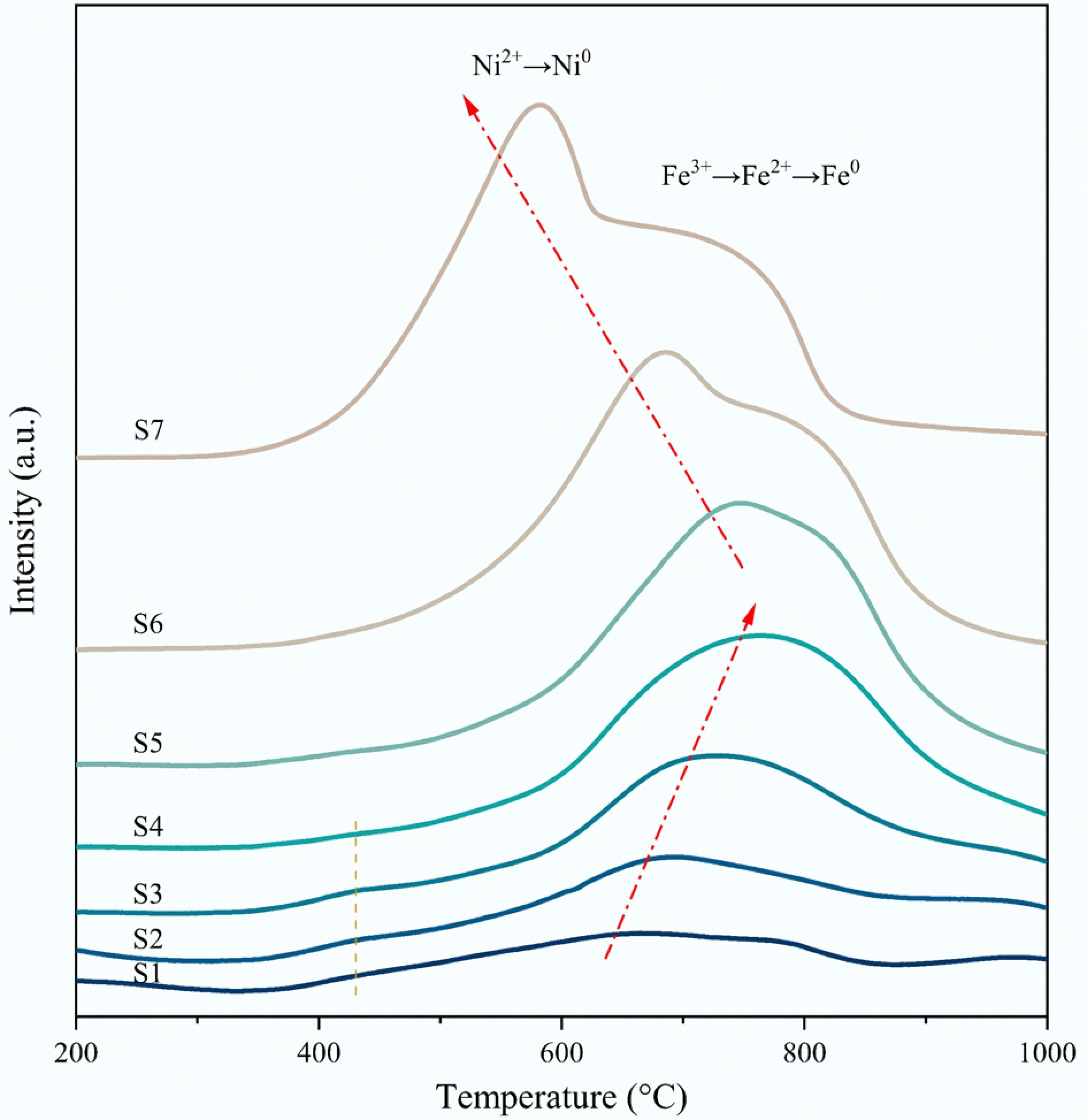

The H2-TPR results of the fresh samples are presented in Fig. 2. Support reduction followed the procedures of MgFeIIIAlO4 → Mg1-xFeIIxO → Fe0, which requires the complete separation of Fe with Mg and Al elements. Therefore, the presence of Al3+ and Mg2+ to some extent hinders the reduction of Fe3+[46]. For the catalysts S1 to S4, the reduction peak located at ~430 °C corresponds to the reduction of surface amorphous NiO, indicating relatively weak interaction with the support. The main reduction peaks located at higher temperatures were assigned to the reduction of the NiO with a strong NiO-MgAl2-xFexO4 interaction. Additionally, improving the Fe doping amount (S1 → S4), the peak shifted to high-temperature range, also confirming the increase in the interactions between NiO and MgAl2-xFexO4. The strong interaction leads to the decrease of NiO crystallite size, which is consistent with XRD findings. With further increase in the Fe doping (1.25 ≤ x ≤ 2.00), two hydrogen reduction peaks obviously appeared for S5–S7 samples. The reduction peak located within the lower temperature range corresponded to NiO → Ni, while the peak at a higher temperature was attributed to the reduction of the MgAl2-xFexO4. Excessively high Fe doping promotes lattice oxygen mobility, resulting in the reduction peak shift towards lower temperatures.

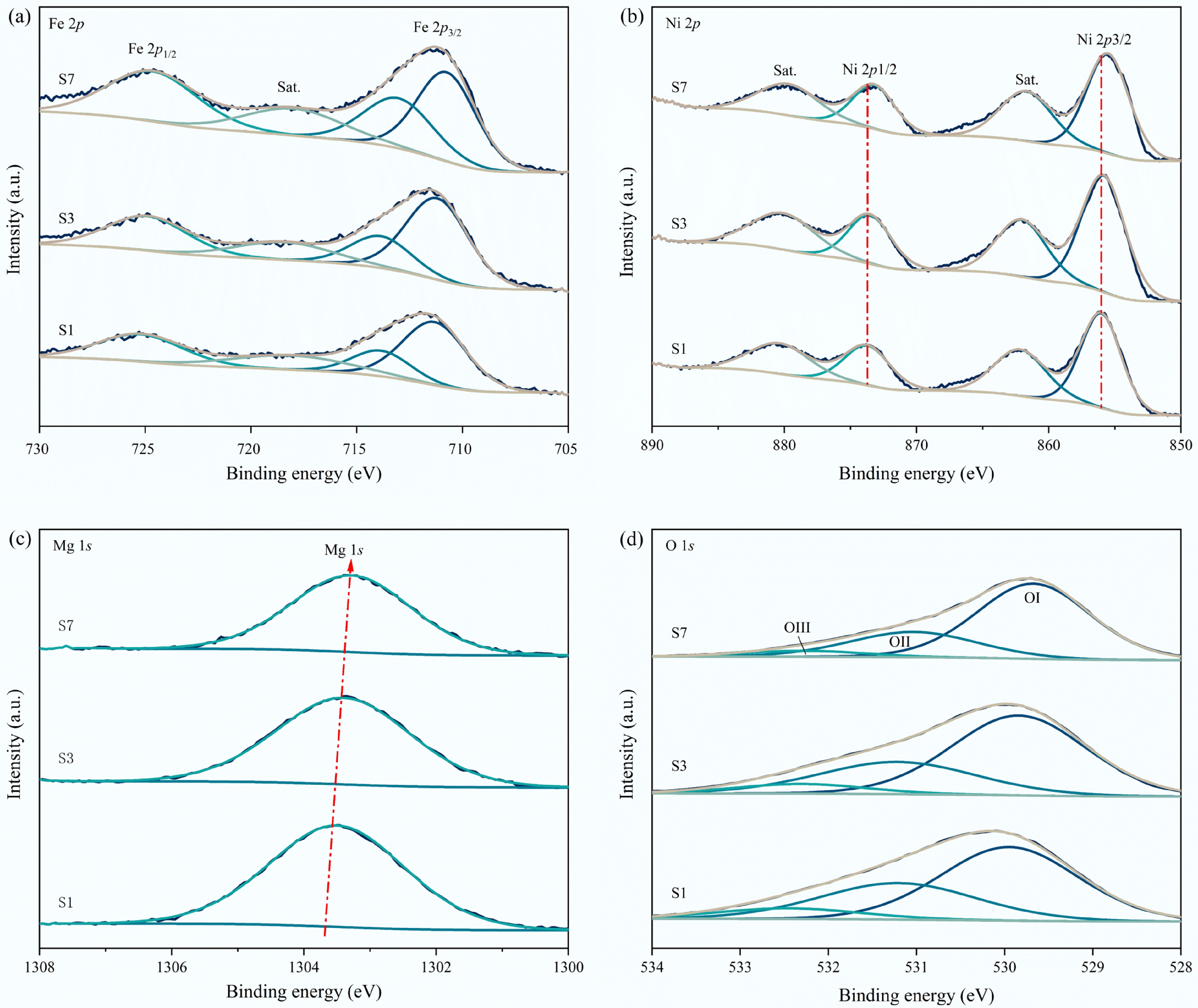

The chemical states of fresh S1, S3, and S7 samples were further explored by XPS, as shown in Fig. 3 and Table 2. From Fig. 3a, Fe 2p spectra of S1, S3, and S7 were deconvoluted into four characteristic sub-peaks. For S3, the strong peak at 711.6 eV was assigned to Fe 2p3/2, and the peak at 724.9 eV was attributed to Fe 2p1/2, which are assigned to Fe3+[47]. The Ni 2p spectra of S1, S3, and S7 samples are illustrated in Fig. 3b. The three catalysts exhibited a Ni 2p3/2 peak at 855.9 eV and a Ni 2p1/2 peak at 873.5 eV, indicating the existence of Ni2+, which aligns with the XRD results. O 1s spectra of fresh S1, S3, and S7 catalysts are shown in Fig. 3c, in which the peaks were deconvoluted into three peaks OI (529.8 eV), OII (531.2 eV), and OIII (532.3 eV), corresponding to lattice oxygen, oxygen vacancy, and surface –OH species in the catalyst respectivel[48]. The ratio of lattice oxygen to oxygen vacancy (OI/OII) in these three catalysts increased with Fe doping amounts, confirming that Fe doping contributes to the formation of lattice oxygen (Table 2).

Figure 3.

XPS analysis of fresh S1, S3, and S7 catalysts. (a) Fe 2p; (b) Ni 2p; (c) Mg 1s, and (d) O 1s.

Table 2. Summary of XPS characteristics of S1, S3, and S7 catalysts

Catalyst Binding energy (eV) Ratio OI/OII Ni 2p3/2 Mg 1s Al 2p Fe 2p3/2 OI OII OIII S1 856.0 1303.5 74.2 711.3 0.58 0.33 0.09 1.76 S3 855.8 1303.4 73.9 711.2 0.63 0.30 0.07 2.10 S7 855.5 1303.3 / 710.7 0.68 0.26 0.05 2.62 Catalytic methane decomposition

-

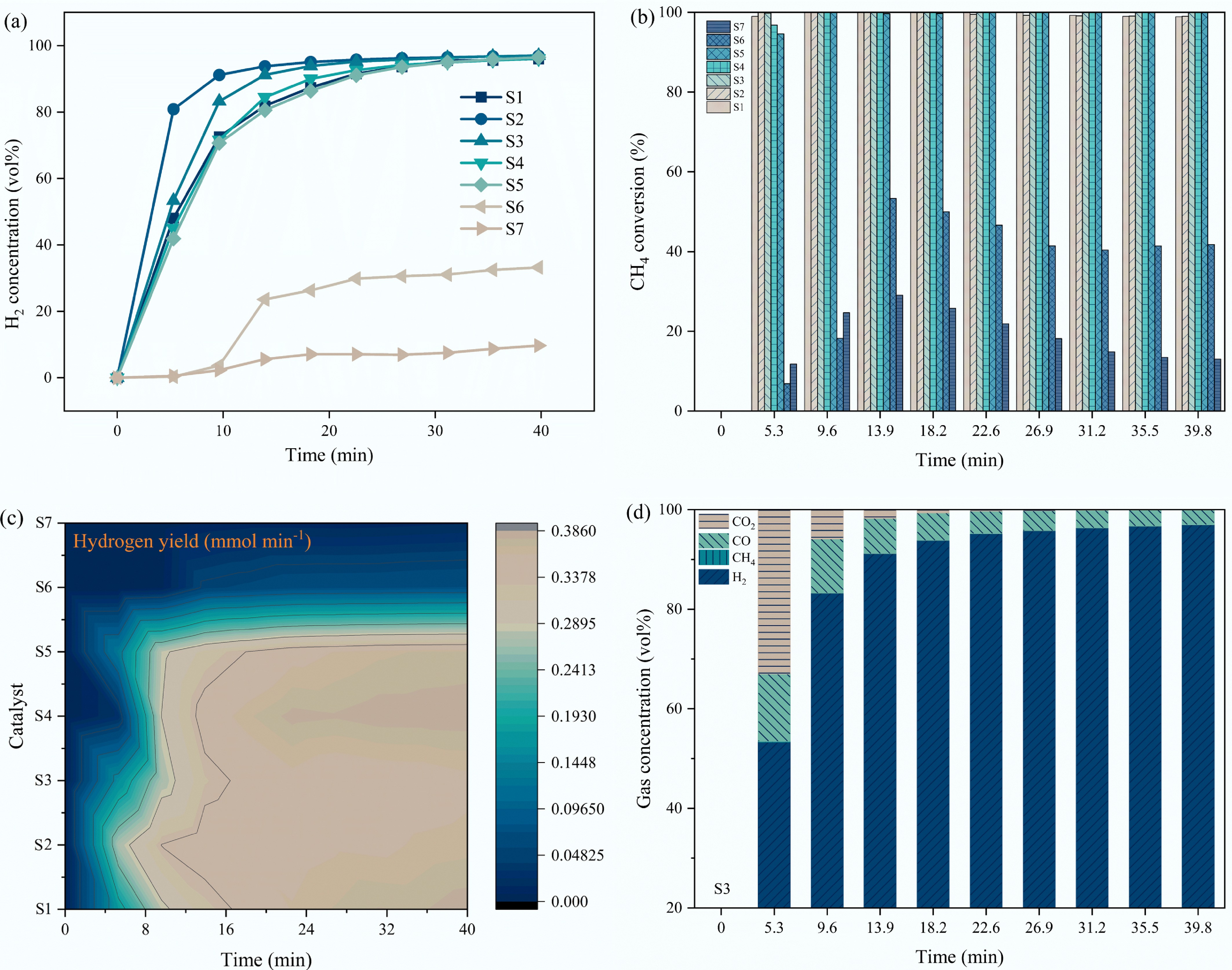

The CMD activities of the seven samples were firstly examined at 750 °C (Fig. 4). At the initial period of CMD, S1 to S5 samples exhibited satisfactory CH4 conversion but relatively low H2 concentration and H2 yield, which can be ascribed to methane selective oxidation induced by the lattice oxygen. CH4 conversion, H2 concentration, and H2 yield all increase as a function of CMD times. This can be attributed to Ni-Fe alloy formation, thus enhancing the catalytic performance, as proven by XRD (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 4.

Effect of Fe doping on the (a) H2 concentration; (b) CH4 conversion; (c) H2 yield; (d) gas concentration of H2, CH4, CO, CO2 under the catalysis of S3 catalyst.

As shown in Fig. 4a and b, S1−S5 samples reached high H2 concentrations as a function of time, while S6 and S7 samples exhibited inferior performance, indicating that a certain amount of Al doping is essential. Of the S1−S5 samples, S3 catalyst showed the best CMD activity and hydrogen evolution rate, and the H2 concentration and the CH4 conversion reached 97 vol% and 100%, respectively, after 40 min CMD (Fig. 4b and d). The gas concentration evolutions with CMD times by using S1, S2, S4, S5, and S6 catalysts are provided in Supplementary Fig. S2. After comprehensively considering CH4 conversion, H2 yield, and quality, the S3 sample was selected as the optimal catalyst for further exploration.

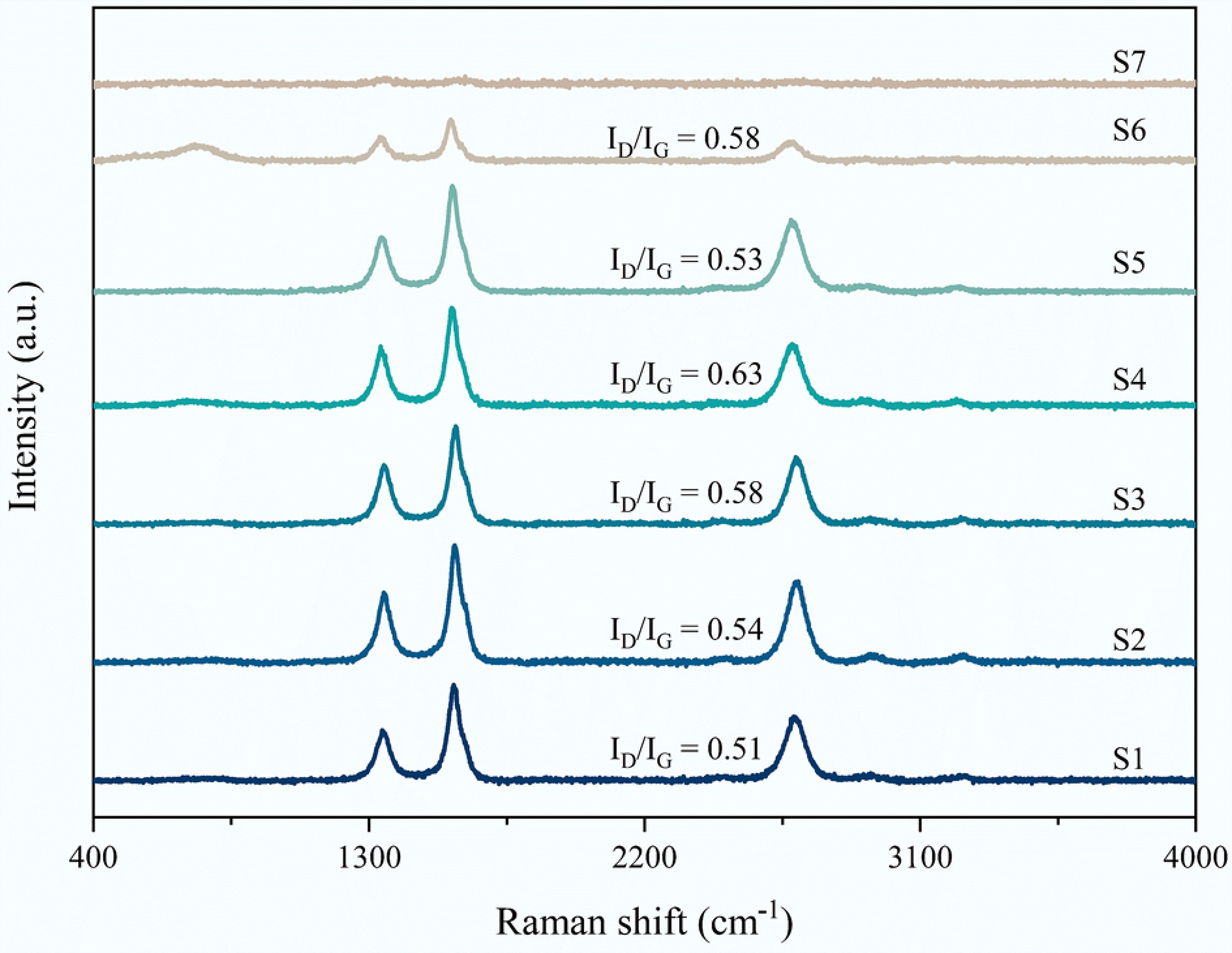

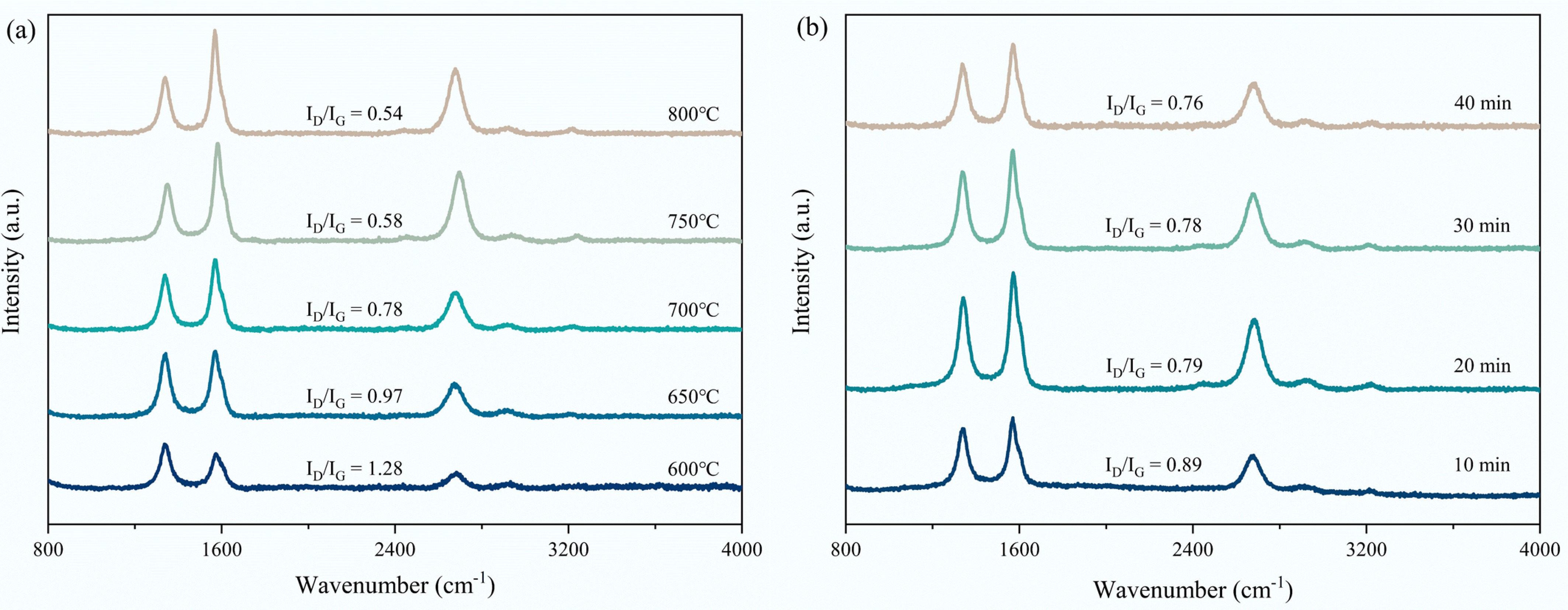

Raman measurements were carried out to identify graphitization degree of carbon on the spent S1–S7 catalysts after CMD (Fig. 5). Three peaks were observed at 1,335–1,348/cm, 1,565–1,580/cm, and 2,670–2,695/cm, corresponding to D, G, and 2D bands, respectively. D band represents disordered structures, which is ascribed to the vibration of the sp3-hybridized carbon atom[49]. The G band is due to the in-plane vibrations of the sp2-bonded carbon in ordered graphite[50,51]. 2D band is the second order of the D band[50]. The intensity ratio of the D band to G band (ID/IG) is related to the crystallinity and graphitization degree of the carbon species. Carbons with a high ID/IG ratios could favor their oxidation at lower temperatures[42,52]. Overall, except for the S7 sample, the carbon obtained from the carbon deposition in other samples had a relatively high degree of graphitization. Additionally, the graphitization degree of carbon exhibited a first decreasing and then increasing trend with the Fe content, and the carbon catalyzed by the S3 catalyst showed the highest ID/IG value.

Effect of CMD temperatures

-

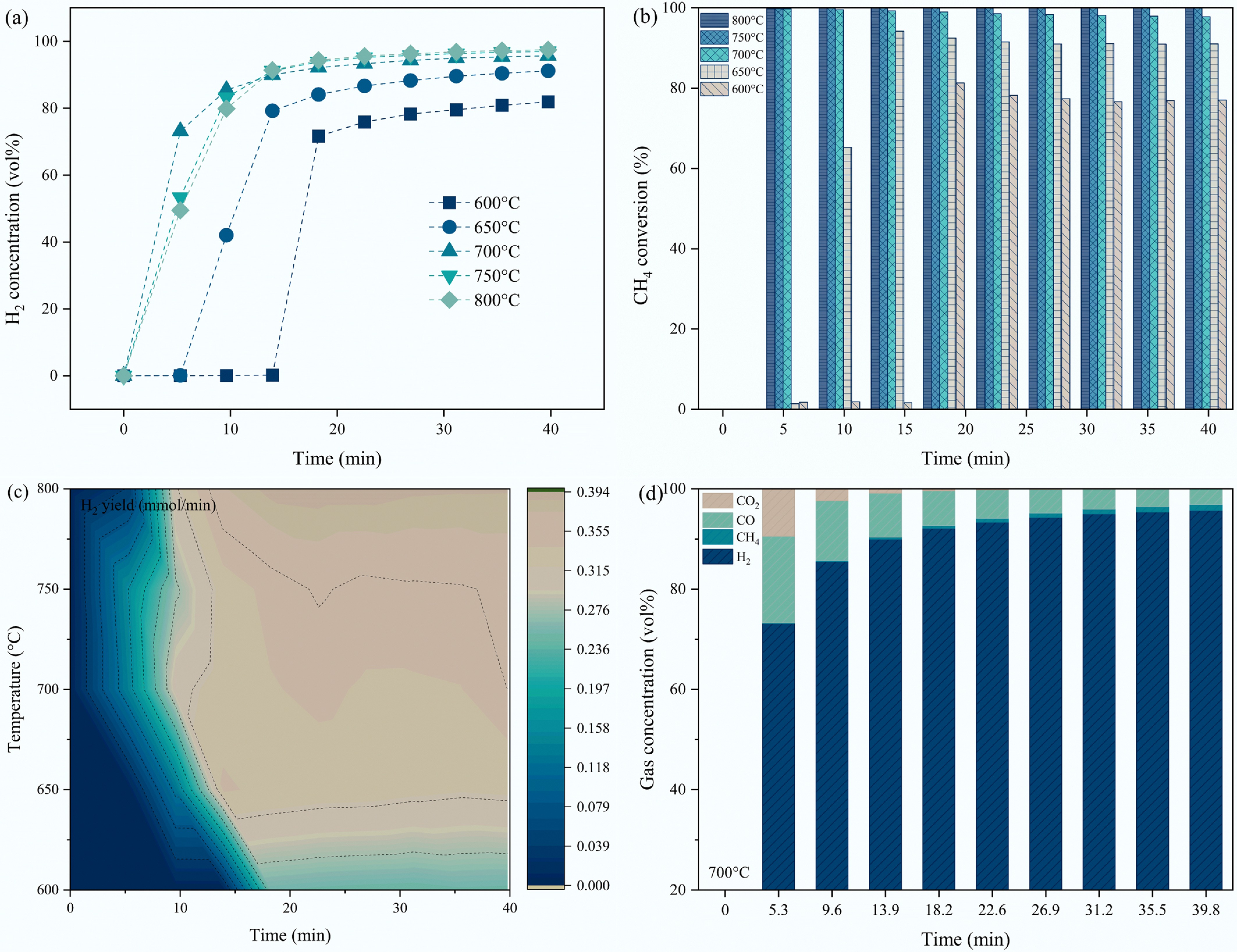

CMD temperature shows significant effects on the methane decomposition performance. It can be observed from Fig. 6a, b, and c that the H2 concentration CH4 conversion, and H2 yield show a gradually increasing tendency with methane decomposition temperatures, which is because of the acceleration of the C-H bond cleavage (Supplementary Fig. S3). Specifically, the H2 concentration and CH4 conversion with applied S3 catalyst reached 91.21 vol% and 91.03% at 650 °C, respectively, which implies the significant superiority of the S3 sample in low-temperature hydrogen generation from CMD. The hydrogen concentration and methane conversion reached up to 95.73 vol% and 97.82%, when the CMD temperature was raised to 700 °C (Fig. 6b and d). The NiO/MgAlFeO4 (S3) catalyst also demonstrated higher CMD activity compared with other reported studies under nickel-based catalysts, and 700 °C was considered an appropriate temperature for methane decomposition (Supplementary Fig. S4)[34,49,53−55].

Figure 6.

Effect of methane decomposition temperatures on (a) H2 concentration; (b) CH4 conversion; (c) H2 yield using S3 sample; (d) the gas concentrations of H2, CH4, CO, CO2 under S3 catalyst at 700 °C.

For a fresh S3 catalyst, NiO and MgAlFeO4 are the main phases. After CMD, Ni-Fe alloy and MgAl0.6Fe1.4O4 were observed as the main phases, indicating the occurrence of reduction and phase recombination of the catalyst. Specifically, the diffraction peaks appeared at smaller angles relative to metallic Ni, suggesting that Fe gradually migrated from support to surface with the formation of Ni-Fe alloy, as also described previously[56−58]. In addition, the characteristic peak of graphitic carbon was observed around 26.5° (JCPDS 02-0405), which is the product of methane decomposition.

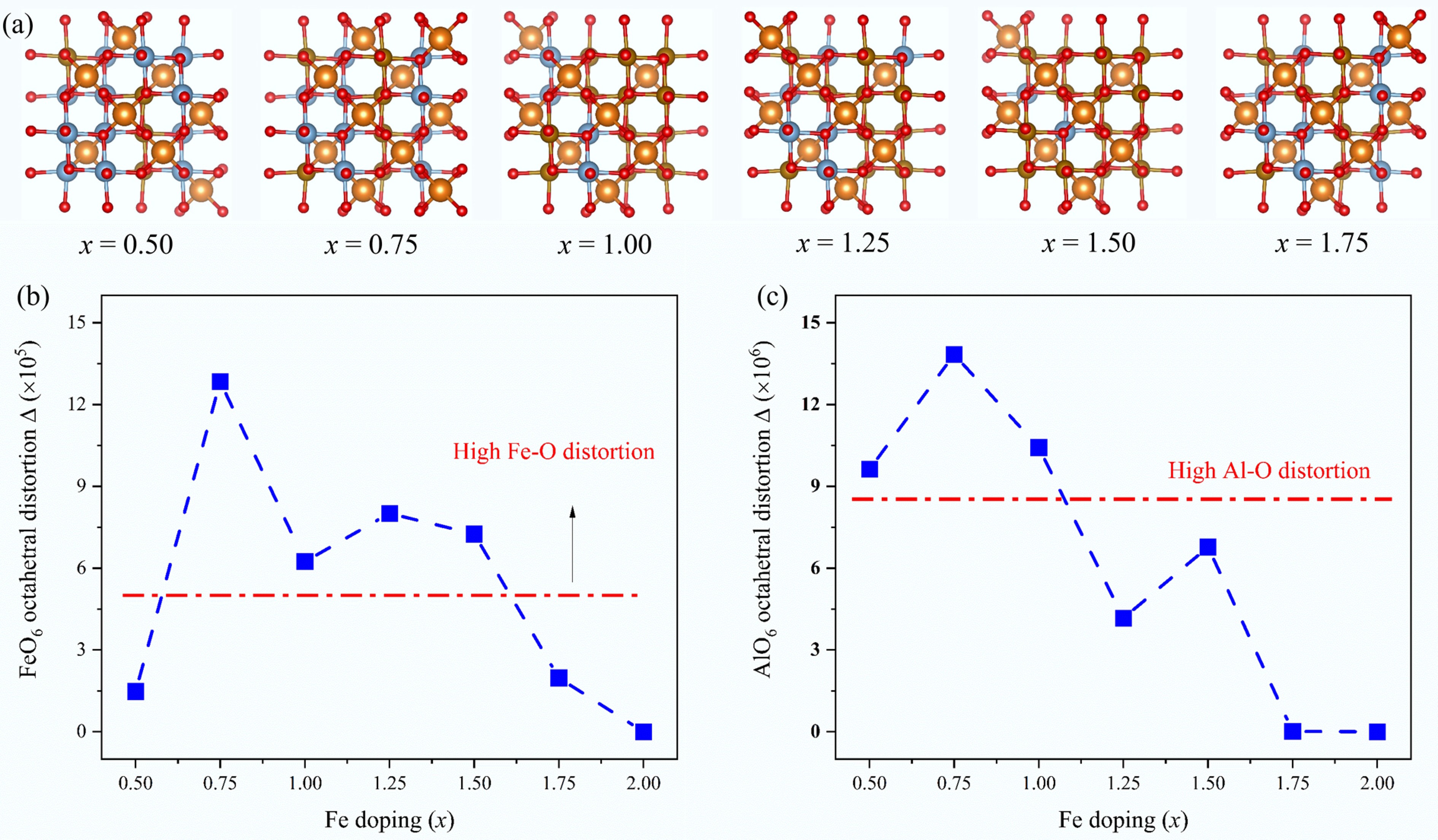

To further clarify the intrinsic reason for highly efficient CMD, we calculated the lattice distortion of these catalysts under various Fe doping amounts. Zhang et al.[59] previously quantified the lattice distortion degree of the Ce modified LaFeO3 perovskite by the method reported by Shannon[60,61]. The lattice distortion was carried out to evaluate the degree to which the Fe-O bond deviates from the average one. The lattice distortion of MgAl2-xFexO4 supports, Δ(Fe-O) and Δ(Al-O), were assessed by the following equation:

$ \Delta = \dfrac{{\text{1}}}{{\text{6}}}\sum {\left( {\frac{{{R_i} - {R_{av}}}}{{{R_{av}}}}} \right)^2} $ (5) where, Rav is the average bond length of the Fe-O or Al-O bond in the octahedron, and Ri is the actual bond length of each Fe-O or Al-O bond. Based on the above equation, the configurated structure of MgAl2-xFexO4 support, as well as the relationship between the Fe doping amount x (0.50 ≤ x ≤ 2.00) and the lattice distortion degree of Fe-O and Al-O bonds, are shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7.

Lattice distortion analysis: (a) bond structure of MgAl2-xFexO4, x = 0.50, 0.75, 1.00, 1.25, 1.50, and 1.75, corresponding to MgAl1.50Fe0.50O4, MgAl1.25Fe0.75O4, MgAl1.00Fe1.00O4, MgAl0.75Fe1.25O4, MgAl0.50Fe1.50O4, and MgAl0.25Fe1.75O4, respectively; (b) Fe(Al)O6 octahedral distortion as a function of Fe doping.

It can be found that the FeO6 and AlO6 distortion occurs with varying Fe doping amounts. On the one hand, Fe doping amounts of 0.75, 1.00, 1.25, and 1.50 performed high Fe-O distortions, which promotes the breaking of Fe-O bonds, thereby enhancing the formation of Ni-Fe alloy; on the other hand, Fe doping amounts under 0.50, 0.75, and 1.00 performed high Al-O distortions. This may alter the electron cloud distribution around Al3+, enhancing its Lewis acidity and altering its electron density around the active Ni species, thereby facilitating methane dehydrogenation. According to the discussion above, the S2 and S3 samples were considered as promising catalysts, which is in full agreement with the experimental results, demonstrating synergistic lattice distortions of Fe-O and Al-O octahetral in boosting CMD activity.

The carbon graphitization degree after 40 min CMD at 600–800 °C was analyzed by Raman spectra (Fig. 8a). Three peaks in the D, G, and 2D bands of the deposited carbon can be observed. The ID/IG gradually decreased with the CMD temperatures, implying the gradually decreased carbon disorder degree. It is determined that a high temperature promotes generating highly graphitized carbon with an ordered structure. The effect of CMD times from 10 to 40 min on the carbon graphitization degree was also studied at 700 °C. Figure 8b displays the positive correlation between the carbon graphitization degree and the CMD time, i.e., extending the CMD time can enhance its graphitization degree.

Figure 8.

Raman spectra of (a) spent S3 sample after 40 min CMD at 600−800 °C; (b) spent S3 sample after 10−40 min CMD at 700 °C.

Effect of carbon dioxide reduction temperatures

-

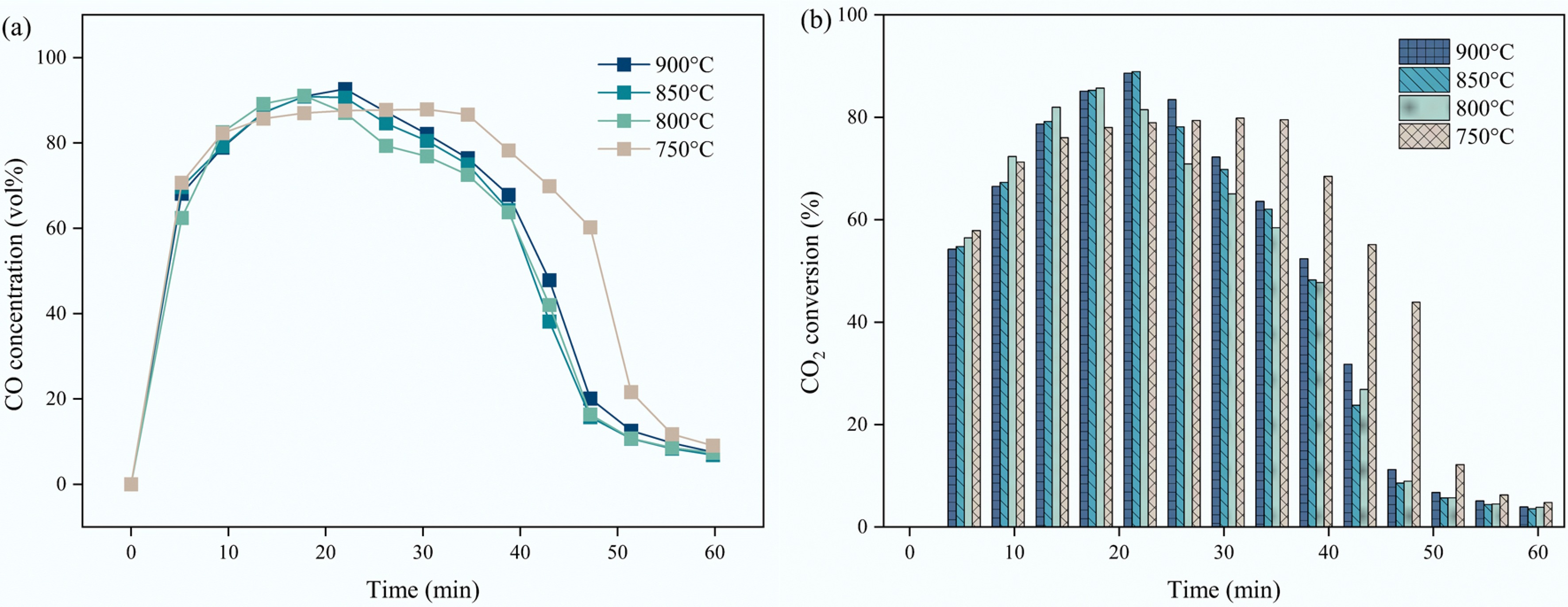

Catalyst and carbon separation presents a significant challenge for gas-solid CMD technology. CO2 is a commonly utilized gasification agent and thus was selected for eliminating the deposited carbon from CMD. The effect of carbon dioxide reduction temperatures from 750 °C to 900 °C on the carbon elimination performance was investigated (Fig. 9). As we expected, the increase in the carbon dioxide reduction temperature showed a positive impact on the carbon dioxide reduction, owing to higher C=O bond dissociation rate at high temperatures. According to the XRD results of the oxidized S3 sample, the cycled catalyst is mainly composed of Ni and MgFeAlO4, while other phases such as MgFe0.6Al1.4O4 and (MgO)0.91(FeO)0.09 were also detected. This confirmed that the main evolution of the S3 catalyst is: NiO·MgFeAlO4 → Ni-Fe alloy + MgFe0.6Al1.4O4 → Ni + MgFeAlO4, and Ni + MgFeAlO4 would be a stable form of the cycled catalyst.

Figure 9.

Effect of carbon dioxide reduction temperatures on the (a) CO concentration; (b) CO2 conversion of S3 sample.

Stability test

-

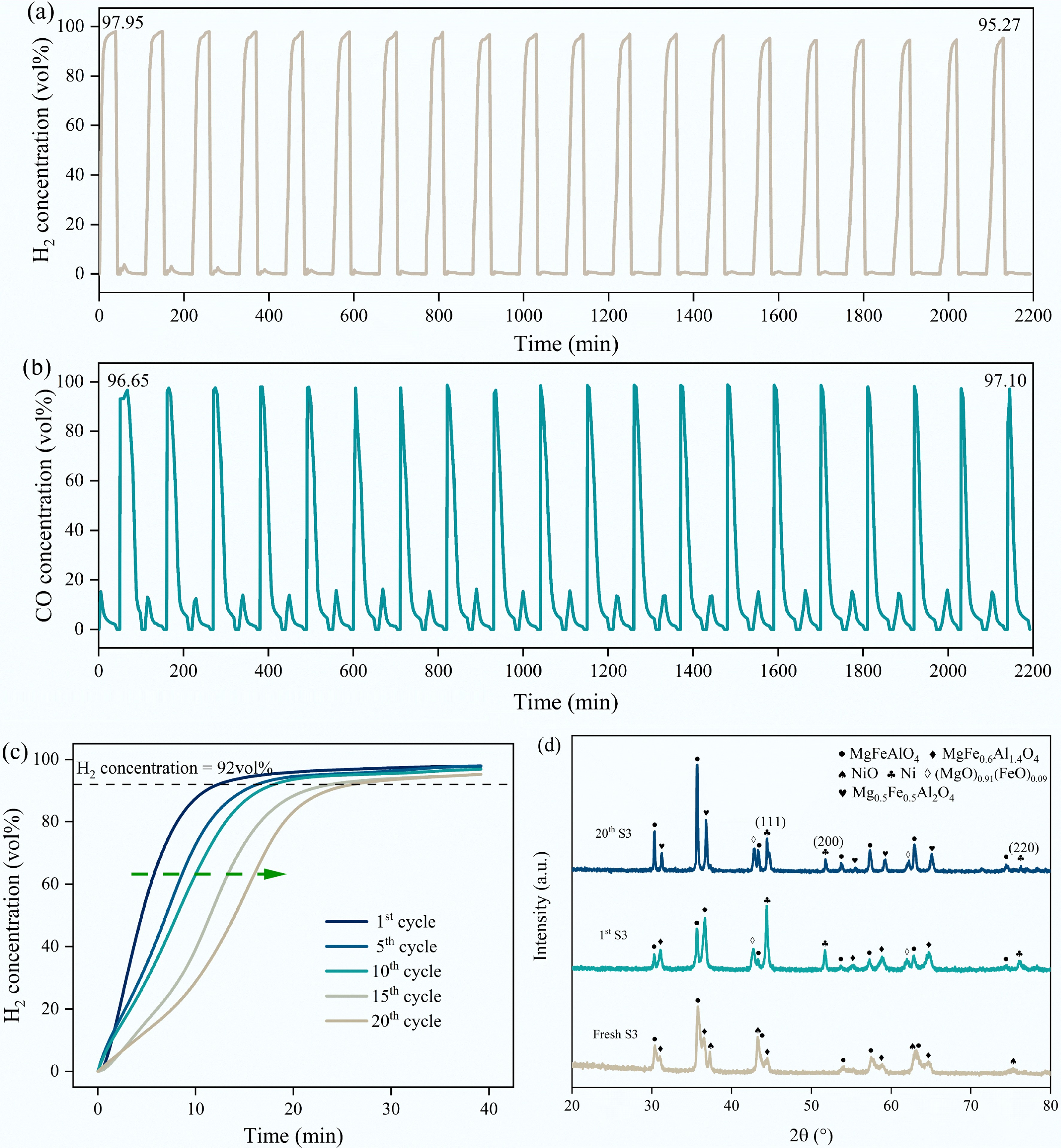

Twenty cycles of methane decomposition (800°C) with carbon dioxide reduction (900 °C) were performed to explore the stability of the S3 catalyst (Fig. 10a−c). S3 sample showed remarkable catalytic activity and stability even after 20th cyclic experiments. The maximum concentration of H2 dropped slightly from 97.95 vol% (1st cycle) to 95.27 vol% (20th cycle), and the concentrations of CO remained at approximately 97.00 vol%. The preeminent stability of the catalyst could be attributed to the in situ formation of Ni-Fe alloy as well as the re-generation of Ni/Mg2Al2-xFexO4 at the CO2 reduction stage. This phase segregation and re-organization suppresses the particle sintering and agglomeration, thus remaining significant durability under high temperature and carbon deposition conditions. At the initial period of methane decomposition, the phase NiO in the S3 catalyst was reduced and combined with Fe segregated from the support to form a Ni-Fe alloy, which realized efficient dissociation of methane. During the carbon dioxide reduction stage, the Ni-Fe alloy was disassembled. The formation and disassembly of the Ni-Fe alloy promoted the dispersion of Ni and inhibited the sintering and agglomeration of the catalyst to a certain extent. However, by counting the start-up time of the S3 catalyst during 20 cycles, we found that the time required for efficient methane decomposition for hydrogen production gradually increased with the cycle numbers, which can be accounted for by the following reasons: (1) Fe segregated from Ni-Fe alloy and formed FeOx species on the catalyst surface after carbon dioxide reduction, covering partial nickel-rich particles, thereby prolonging the time required for Ni-Fe alloy formation[40,44,58]; (2) The particle size of the catalyst gradually increases with cycles, leading to slower consumption of lattice oxygen under methane decomposition conditions. As a result, the time required for Ni-Fe alloy formation increases[42]. Apart from the cyclic performance of the S3 catalyst over 20 methane decomposition-carbon dioxide reduction cycles, its phase evolution during the cycle was investigated, as presented in Fig. 10d. After 20 cycles, the phase components of the S3 catalyst were basically in line with the 1st cycled state, except that a small proportion of MgFe0.6Al1.4O4 was transformed into Mg0.5Fe0.5Al2O4. This clarifies the slower lattice oxygen migration rate of the cyclic S3 sample, i.e., the B-site Fe in MgFexAl2-xO4 was migrated into the A-site MgxFe1-xAl2O4, thus lowering the lattice oxygen mobility.

Figure 10.

Cyclic stability test of S3 sample: (a) H2 concentration during 20 cycles; (b) CO concentration during 20 cycles; (c) Variation of H2 concentration with time and catalyst activation time in the 1st, 5th, 10th, 15th, and 20th cycles (based on 92 vol% H2 concentration); (d) XRD patterns of significant stages within 20 cycles of reacted S3 sample.

To observe the microscopic morphology and element distribution of S3, TEM-EDS was performed on the fresh, 1st cycled, and 20th cycled samples (Supplementary Fig. S5). Fresh samples were made of stacked nanosheets with grooves, while the groove morphology disappeared after one CH4 decomposition and carbon dioxide reduction cycle, confirming the occurrence of phase segregation and re-organization. EDS mapping results demonstrated that the Ni, Fe, and Al elements of fresh and 1st cycled S3 samples were homogeneously distributed. After 20 cycles, partial Ni, Fe, and Al elements were found to be separated from each other. This indicates that some phases did not undergo recombination, possibly due to incomplete removal of the deposited carbon, which leads to phase isolation.

-

A series of novel Fe-doped nanostructured supports, MgAl2-xFexO4, were prepared by a sol-gel method, and impregnated with Ni to form an NiO·MgAl2-xFexO4 catalyst. The effects of Fe doping, as well as other influencing parameters, on the reactivity and stability of the catalyst and the CMD performance were investigated. Results showed that a proper quantity of Fe doping showed a favorable impact on the improvement of the catalyst performance. Among the synthesized catalysts, Ni/MgAlFeO4 demonstrated the highest catalytic activity, achieving a 97 vol% H2 concentration and a 100% methane conversion at 750 °C with the generation of deposited carbon with relatively low graphitization degree. Additionally, the catalyst showed satisfactory stability over 20 methane decomposition and carbon dioxide reduction cycles, with only a slight decrease in H2 concentration observed. This splendid performance is owing to the formation high dispersed Ni-Fe alloy with the induction of Al-O and Fe-O bond distortion. In a typical cycle, the catalyst evolves from NiO·MgFeAlO4 to Ni-Fe alloy with MgFe0.6Al1.4O4 and to Ni with MgFeAlO4, demonstrating the occurrence of phase segregation and recombination. Moreover, the inhibition of Ni-Fe phase segregation/reconstruction and the slowing down of lattice oxygen migration rate owing to the phase transformation from MgFexAl2-xO4 to Mg0.5Fe0.5Al2O4 are the dominant factors affecting the multi-cycle activity of catalysts.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/een-0025-0005.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: All authors; Material preparation, data collection and analysis, draft manuscript preparation: Sun Z (Zhao Sun), Chen Z; project supervision, manuscript editing: Sun Z (Zhiqiang Sun). All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFE0206600).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Low-temperature methane decomposition with carbon dioxide reduction was proposed.

The NiO/MgAlFeO4 catalyst showed excellent catalytic activity and stability in CMD.

91.03% CH4 conversion and 91.21 vol% H2 concentration can be obtained at 650 °C.

Lattice distortion of MgAl2−xFexO4 dominates graphitization degree of deposited carbon.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Supplementary Table S1 Nominal metal nitrate ratio prepared for seven catalysts.

- Supplementary Table S2 Metal contents of the fresh catalysts.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 XRD patterns of the reacted S3 sample in fresh, spent, and CO2 oxidized states.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 The gas concentration of H2, CH4, CO, and CO2 under the catalysis of S3 (a) S1; (b) S2; (c) S4; (d) S5; (e) S6; (f) S7 at 750 °C.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 The gas concentration of H2, CH4, CO, and CO2 under the catalysis of S3 catalyst at (a) 600 °C; (b) 650 °C; (c) 750 °C; (d) 800 °C.

- Supplementary Fig. S4 Study on CMD performance based on nickel catalyst.

- Supplementary Fig. S5 TEM-EDX mapping of S3: (a) fresh sample; (b) 1st cycled sample; (c) 20th cycled S3 sample.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Sun Z, Chen Z, Sun Z. 2025. Modulating lattice distortion of NiO/MgAl2-xFexO4 for low-temperature methane decomposition with CO2 reduction. Energy & Environment Nexus 1: e006 doi: 10.48130/een-0025-0005

Modulating lattice distortion of NiO/MgAl2-xFexO4 for low-temperature methane decomposition with CO2 reduction

- Received: 20 June 2025

- Revised: 02 August 2025

- Accepted: 15 August 2025

- Published online: 30 September 2025

Abstract: Methane decomposition technology is regarded as a promising pathway for one-step H2 generation but suppressed by carbon deposition and catalyst deactivation. To solve these problems, a series of NiO/MgAl2-xFexO4 (0.50 ≤ x ≤ 2.00) catalysts were prepared for accomplishing low-temperature H2 generation from catalytic methane dissociation and alleviating catalyst invalidation through a carbon dioxide reduction strategy. Results indicate that a methane conversion of 91.03% and a hydrogen concentration of 91.21 vol% were achieved at 650 °C using NiO/MgAlFeO4. Long-term durability experiments were conducted under high-temperature and carbon-deposited conditions, and the NiO/MgAlFeO4 material still had highly satisfactory activity and stability after 20 cycles. It is revealed that the lattice distortions of Fe-O and Al-O in NiO/MgAl2-xFexO4 could be the dominant factor for boosted hydrogen generation from methane decomposition, synergistically promoting methane activation and dehydrogenation. These findings provide new implications for advanced catalyst design, which will substantially promote methane decomposition in a highly efficient manner.