-

Energy production and consumption play a crucial role in the world's scientific, economic, and social environment that humanity has constructed throughout time[1]. The contemporary economy is primarily propelled by energy, with a worldwide energy demand of roughly 13,973 million tons of oil equivalent (Mtoe). By 2019, 85% of global energy demand was met by fossil fuels[2]. In recent decades, the growing demand for fossil fuels, urbanization, and modernization have led to a significant increase in the emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG). The atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration increased from approximately 280 ppm before the Industrial Revolution to approximately 418.9 ppm in 2023[3]. The atmospheric CO2 concentration is projected to reach around 570 ppm by the end of this century[4].

Consequently, there has been an estimated rise in the global mean temperature of 0.85 °C since the 18th Century[5]. In an effort to ameliorate the potentially disastrous effects of global warming, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has recommended limiting temperature increases to 2 °C, with a preferable target of 1.5 °C by the end of the current century[6]. The task of reducing CO2 emissions is a challenging and enduring endeavour. As recommended in the fifth edition of the IPCC, a comprehensive transformation of worldwide energy supply systems, lifestyles, and dietary requirements is necessary. The depletion of fossil fuels is also a serious concern[7]. It is imperative to persist in commercializing low-carbon and carbon-neutral resources for chemicals, energy, materials, and technologies to facilitate the adoption of low-carbon pathways. The 2016 Paris Agreement underscores the need for a phased reduction in fossil fuel dependency, targeting a 50% reduction in CO2 emissions through the increased integration of renewable energy sources[8]. Biomass has emerged as a promising feedstock in this transition due to its carbon neutrality. It has been reported that 80%–90% GHG emissions can be reduced by replacing fossil fuels with biomass[9]. The shift from a carbon economy of fossil fuel-dependent to a bio-based fuel is anticipated to undergo a gradual and ongoing transformation in the next few decades, with a consequential impact on all processing industries[10].

In the future, a bio-based alternative is expected to supplant the petrochemical product tree. The transition in raw materials should be perceived as an opportunity to restructure the industrial chain by utilizing renewable raw feedstocks to create novel products rather than as a potential hazard[10]. The utilization of bio-based carbon in biomass processes is characterized by its sustainability and renewability, resulting in a near carbon-neutral outcome. The implementation of suitable residue management strategies can result in a carbon-negative process. The emergence of bio-based fuels can be attributed to the availability of resources, advances in science and technology, and favourable policies.

Unlike other renewable energy sources such as wind, solar, geothermal, or hydropower, biomass is unique in its capacity to store carbon-based chemical energy. It serves as a readily available resource for biofuel production, aligning with global policy efforts to decarbonize the transportation sector. Initially, biofuel policies focused on first-generation biofuels derived from food crops such as corn, sugarcane, and canola. However, concerns over indirect land-use change (iLUC), GHG emissions, and food security have prompted a shift toward second- and third-generation biofuels, derived from non-food biomass sources such as agricultural residues, algae, and woody biomass[11]. Advanced synthetic biofuels offer the advantage of higher energy yields while preventing negative ecological and socio-economic side-effects such as high GHG emissions through indirect land-use change (iLUC)[11], or the competition manifested in the food-vs-fuel debate.

Recent policy frameworks, such as the European Union's Renewable Energy Directive (2018/2001), impose strict limitations on biofuels with a high iLUC risk[12]. Similarly, the ReFuelEU Aviation initiative, as part of the EU Fit for 55 Package, promotes second- and third-generation biofuels as sustainable alternatives for decarbonizing the aviation sector[13]. Globally, governments are implementing policies to accelerate the adoption of advanced biofuels. The U.S. Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) mandates annual volume targets for four fuel categories: (a) cellulosic biofuel, (b) biomass-based diesel, (c) advanced biofuel, and (d) renewable fuel[14]. China has also implemented and supported renewable energy production, such as solar, wind, and biomass, including gasification, liquefaction, and direct combustion[15]. In 2023, the global power production was sourced 26% from coal, 32% from petroleum, 23% from natural gas, and 14% from renewables[16]. These data underscore the urgent need to scale up bio-based energy solutions to achieve a sustainable energy transition.

As the global energy landscape evolves, the demand for renewable and low-carbon fuels is projected to rise substantially. With continuous advancements in technology and policy frameworks, second-generation biofuels are gaining momentum as a promising pathway toward sustainable and environmentally friendly energy solutions. However, accurately assessing their feasibility and advantages over conventional fossil fuels requires scientifically rigorous and data-driven methodologies[17]. Life-cycle assessment (LCA) and techno-economic analysis (TEA) play a crucial role in evaluating novel biofuel technologies by systematically analyzing their socioeconomic, environmental, and technical feasibility[18]. LCA focuses on quantifying environmental aspects such as GHG emissions, energy consumption, and resource utilization, while TEA assesses economic viability by estimating production costs, investment requirements, and market competitiveness.

A key focus of these assessments lies in the production phase, where LCA and TEA aid in optimizing design parameters and estimating the market price of value-added biofuel products. Before large-scale investment in emerging biofuel technologies, funding agencies and policymakers require a thorough evaluation of both environmental performance and economic feasibility. This is particularly critical for thermochemical conversion processes, which must demonstrate commercial viability before widespread adoption. When conducting LCA for biomass thermochemical conversion processes, explicitly addressing uncertainties is critical for ensuring robust and reliable results[19]. Three primary types of uncertainty commonly considered are parameter uncertainty, model uncertainty, and scenario uncertainty. Integrating systematic uncertainty and sensitivity analysis through methods like Monte Carlo simulations provides transparency and enhances the credibility and applicability of LCA findings. This approach supports informed decision-making by clearly communicating the potential variability and limitations inherent in LCA studies[20].

Biomass, as a renewable feedstock, is broadly categorized into lignocellulosic sources such as wood, straw, and grass, and non-lignocellulosic sources like sludge, algae, and oil[21]. Compared to coal, as listed in Table 1, biomass typically has higher moisture content, increased volatile matter, elevated oxygen content calculated by the difference from ultimate analysis results, and lower carbon content, all of which influence the choice of conversion pathways[22−26]. Several methods transform biomass into fuels or chemicals, including thermochemical pathways[27] (i.e., combustion, pyrolysis, gasification, and hydrothermal treatment) and biochemical pathways (i.e., anaerobic digestion and fermentation)[28]. Thermochemical conversion processes operate at higher temperatures, allowing for shorter reaction times and nearly complete degradation of biomass components[28]. Some of these processes require catalysts, particularly in tar cracking and reforming, to improve efficiency. The primary products of thermochemical conversion include gaseous fuels such as syngas from gasification and hydrothermal gasification, and liquid biofuels such as bio-oil from pyrolysis and hydrothermal liquefaction, both of which require upgrading to meet fuel standards.

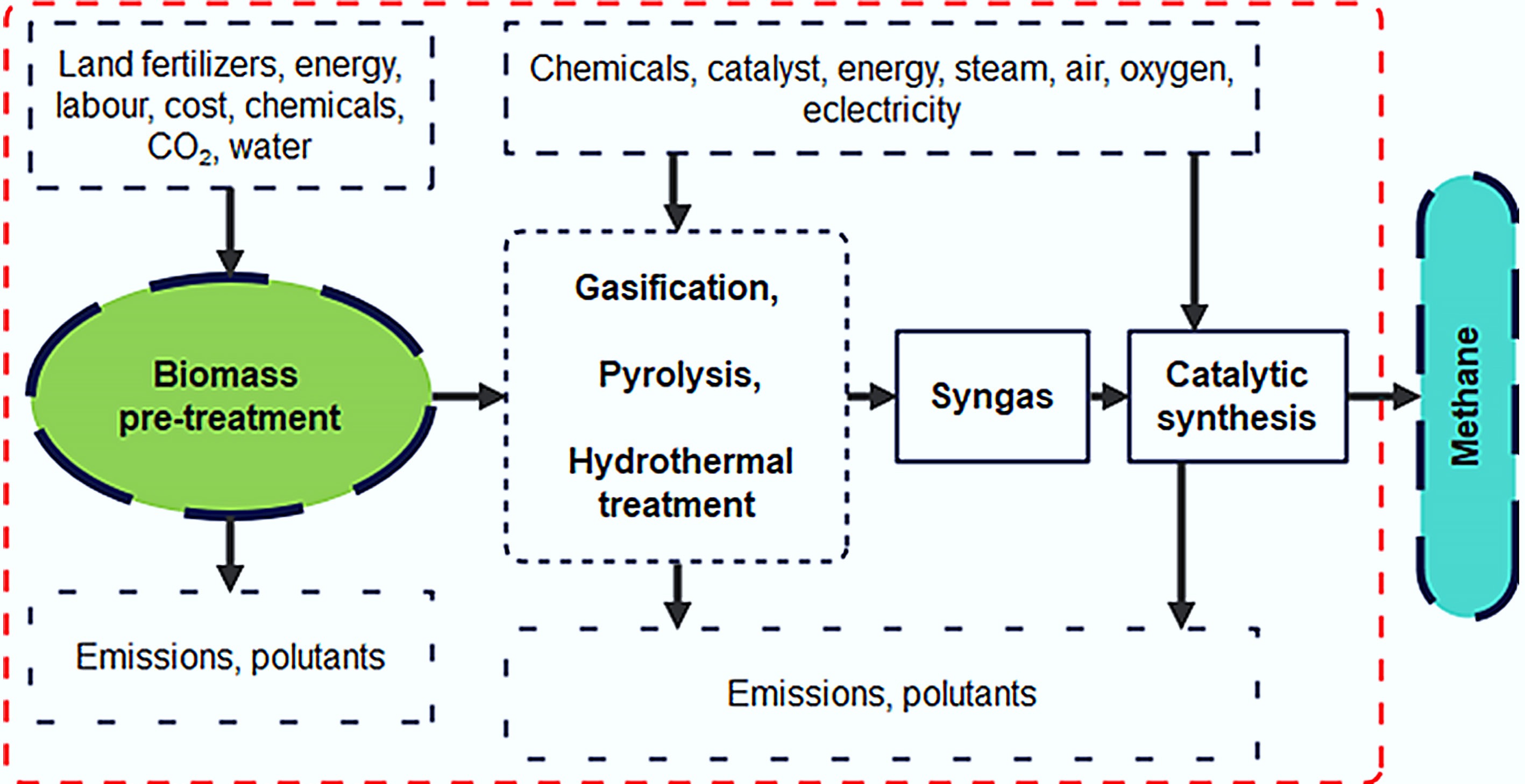

Biomass Proximate analysis (%, as received basis) Ultimate analysis (%, dry ash-free basis) Ash Moisture Organic fraction C H N S O Wood 1.8 19.8 78.4 50.8 6.1 0.3 0.1 42.7 Legume straw 9.8 1.6 73.7 43.3 5.6 0.6 0.1 50.4 Apricot stone 8.5 0.2 75.1 44.4 5.7 0.4 0.0 49.5 Hornbeam shell 9.5 2.3 78.8 41.8 5.4 0.60 0.0 52.3 Hornbeam sawdust 0.5 8.8 78.1 45.2 6.6 0.0 0.0 48.2 Rice husk 12.9 1.1 70.5 42.0 5.4 0.4 0.0 39.3 Straw 6.4 12.7 80.9 48.9 5.9 0.8 0.2 43.9 Safflower 2.2 5.7 80.8 60.5 9.8 3.1 0.0 27.4 Sludge 25.7 32.5 41.8 50.2 7.1 5.6 1.8 34.9 Manure 17.2 43.6 39.2 50.2 6.5 6.5 0.9 34.6 Vegetable oils 0.0 0.0 100.0 75.4 11.7 0.0 12.9 0.0 Biochemical conversion, including anaerobic digestion and fermentation, primarily produces liquid biofuels and biogas, which can also undergo refinement to obtain high-value biofuels. While both thermochemical and biochemical conversion technologies share similarities with traditional oil refinery processes, further research and development of H2-rich processes, such as water gas shift (WGS) reaction, are necessary to improve their economic competitiveness against fossil fuels[29]. As biofuels are increasingly recognized as viable alternatives to fossil-based energy[30], optimizing their production processes and enhancing their commercial feasibility will be critical to accelerating their adoption. The thermochemical conversion pathways involved in biomass-to-biofuel transformation are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic flowchart for thermochemical conversion of biomass into syngas, bio-oil, and char.

The performance and economics of biomass thermochemical conversion are strongly influenced by the inherent variability of feedstocks, especially in tropical and arid regions. Biomass sourced from tropical climates such as sugarcane bagasse, oil palm residues, and fast-growing grasses typically exhibits very high moisture content, often exceeding 50% by weight, as well as significant variability in ash content and mineral composition[21]. High moisture content imposes substantial additional energy demands for drying prior to gasification or pyrolysis, directly increasing operating costs and reducing net system efficiency. In many cases, the parasitic load for drying tropical biomass can represent 15%–30% of total process energy, potentially undermining the overall energy balance if waste heat or low-grade renewable energy is not available[21]. Regional feedstock characteristics thus have direct techno-economic implications, affecting energy yield, process design, capital expenditure (e.g., for robust handling and cleaning equipment), and supply chain configuration. Integrating robust LCA and TEA frameworks with local feedstock assessment is essential for accurately predicting system performance and economic feasibility in both tropical and arid environments.

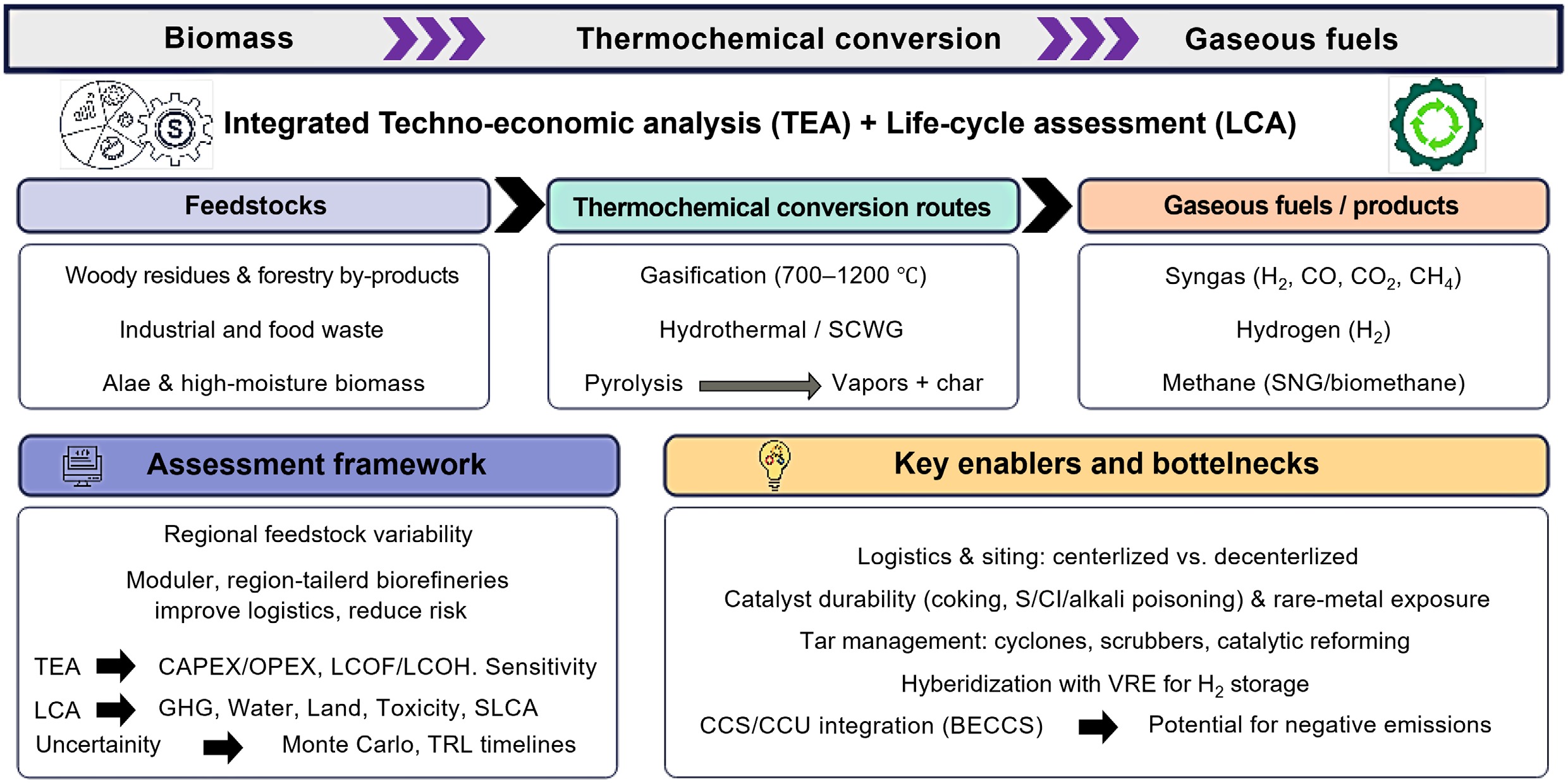

TEA is a widely used methodology for assessing the financial viability of emerging technologies, while LCA evaluates their environmental impact. These evaluations are typically conducted using specialized software (e.g., Aspen, OpenLCA, and SimaPro) that simulates the environmental consequences of a process based on key input parameters, including process variables, energy consumption, and material flows. While numerous studies have focused on the production of liquid biofuels, fewer have examined the socioeconomic and environmental implications of biomass thermochemical conversion into gaseous biofuels.

This review specifically investigates the thermochemical conversion of various biomass feedstocks into gaseous biofuels, namely: (a) bio-based hydrogen, (b) bio-based methane, and (c) bio-based syngas. It provides a comprehensive analysis of the technical and economic feasibility of these processes alongside their environmental implications. By integrating TEA and LCA, this study aims to identify research gaps for guiding future research and tackling challenges in developing technologies for producing gasesous fuels by thermochemical conversion from biomass.

Several review articles on biomass thermochemical conversion processes have recently been published. Adeniyi et al.[31] evaluated biochar derived from leaves, discussing different thermochemical conversion techniques and key properties influencing its environmental uses (feedstock characterization). Ighalo[32] examined thermochemical methods for transforming bio-wastes into eco-friendly sorbents, focusing on their water decontamination capabilities (environmental sustainability). Jha et al.[33] reviewed various biomass resources and corresponding thermochemical technologies, highlighting their efficiency and selectivity toward specific products (biomass resource overview). Muh et al.[34] systematically analyzed thermochemical conversion processes for producing fuels and valuable chemicals from biomass, emphasizing optimization strategies for improving yields (process and technology assessment). Lee et al.[35] summarized the latest catalytic advancements in thermochemical biomass conversion, specifically addressing enhancements in biofuel production efficiency (catalyst development and TEA). Das et al. reviewed different biomass thermochemical conversion methods and compared product yield and quality[36]. The various processes produce different amounts of products. Lewandowski et al. presented the thermochemical conversion model as a function of biomass temperature, pressure, and heating rate. The author articulated that combustion emissions can be compensated for by high-temperature gasification of biomass using steam[37]. While several existing articles focus primarily on the technological aspects, they often overlook the importance of TEA and LCA. This review addresses that shortcoming by thoroughly analyzing thermochemical routes for producing syngas, H2, and methane from biomass, with a particular focus on their environmental impacts and economic performance.

Recent review articles have primarily emphasized individual aspects, such as technological advancements[35,36], specific gaseous fuel production pathways[38], or general biomass-to-energy processes[39,40]. For example, Das et al. extensively reviewed advancements in algal biomass conversion without comprehensive economic or life-cycle perspectives, and Lee et al. addressed catalytic thermochemical conversions but did not include detailed economic and sustainability evaluations[35,36]. Arregi et al.[38] primarily focused on H2 production technologies, with limited coverage of socioeconomic impacts and regional variability of biomass feedstocks.

Patel et al.[39] conducted an integrated review of lignocellulosic biomass conversion pathways, but the work did not incorporate detailed socioeconomic and technology readiness level (TRL) analyses. Similarly, Kumar & Vyas.[40] reviewed various gasification methods, emphasizing technological progress without extensively addressing detailed techno-economic scenarios, lifecycle impacts, or socioeconomic implications. Recent reviews by Ignat et al.[41] and Kaloudas et al.[21] provided insights into land-use conflicts and socio-environmental challenges but lacked comprehensive techno-economic modeling and LCA integration. A comparison has been made with the recent review papers, as given in Table 2. Table 2 benchmarks prior reviews across six lenses: gaseous fuels, integrated TEA, integrated LCA, TRL, socioeconomics, and regional feedstocks, and added a final column (key limitations) to make gaps explicit.

Table 2. Comparative summary with recent review papers relevant to biomass thermochemical conversion

Review study Gaseous fuels Integrated TEA Integrated LCA TRL

analysisSocioeconomic analysis Regional feedstock consideration Key limitations Das et al.[36] Syngas Partial No No No No No integrated TEA + LCA;

no TRL/socioeconomics.Lee et al.[35] Syngas No No No No No Lacks TEA/LCA synthesis and deployment context. Arregi et al.[38] Hydrogen Partial Partial Limited No No Partial TEA/LCA with pre-2020 datasets; limited TRL mapping; excludes SNG. Patel et al.[39] Syngas, hydrogen Partial Yes No No Limited Mixed system boundaries;

no TRL analysis, no regional feedstock economics.Kumar et al.[40] Syngas Partial Partial No No No Absent TRL and socioeconomic lenses. Ignat et al.[41] Bioenergy (general) No Yes No Yes Yes Not a thermochemical-process review; no TEA. Kaloudas et al.[21] Bioenergy (general) No Partial No Partial Yes Limited LCA depth and no

TEA integration.This review Syngas, hydrogen, methane Yes Yes Comprehensive Yes Comprehensive Thermochemical-to-gas focus

with harmonized TEA/LCA, integrated TRL and socioeconomic/

regional lenses.This review fills these gaps by presenting an extensive comparative analysis that includes:

• Robust integration of TEA and LCA methodologies across multiple gaseous biofuel production routes.

• Detailed analyses of economic scenarios under varying carbon pricing schemes.

• Comprehensive assessment of TRLs and commercialization prospects for biomass-to-gas technologies.

• In-depth exploration of socioeconomic implications, including labor conditions, community impacts, and food-vs-fuel debates.

• Consideration of regional variability, specifically addressing moisture and ash content impacts in tropical and arid zones.

This review goes beyond prior summaries by providing a decision-oriented synthesis that jointly treats TEA, LCA, TRL, socioeconomics, and regional feedstock constraints for thermochemical routes to syngas, H2, and CH4. This holistic approach not only helps inform better decision-making but also emphasizes the significance of these innovations in supporting the global energy transition. Incorporating TEA and LCA into biomass biofuel production processes provides a clear path toward more sustainable energy solutions. A comprehensive study illustrating the relationship between biomass-based gaseous fuels and the energy transition can further enhance the understanding of these complex dynamics. Such a study can serve as a tool to communicate the importance of these biofuels in reducing carbon emissions and enhancing energy security, aligning with global sustainability objectives.

-

Expanding biomass supply chains can significantly influence socioeconomic dynamics and alter land-use patterns, particularly when transitioning agricultural lands from food production to bioenergy crops. One critical concern is the well-documented food-vs-fuel debate, which arises when fertile land traditionally used for cultivating food crops is redirected toward biomass production for energy purposes. Recent studies have raised substantial concerns about potential negative implications for food availability, food prices, and nutritional security, especially in vulnerable regions already facing food shortages[42]. This competition can exacerbate food insecurity by driving up prices and limiting access to essential crops, underscoring the importance of strategic planning to balance bioenergy development with food security objectives.

Moreover, biomass energy supply chains can influence local and regional labor markets. Bioenergy projects have the potential to create numerous employment opportunities in agriculture, harvesting, transport logistics, processing, and distribution. However, these opportunities are frequently seasonal, characterized by low wages and often precarious working conditions, unless supported by robust labor standards and protective regulations. Recent analyses emphasize that meaningful socioeconomic benefits from biomass production require policy frameworks to secure fair labor conditions, adequate income, and improved livelihoods, particularly in rural and economically disadvantaged areas[43].

Land-use changes driven by biomass expansion pose additional sustainability risks. Converting forests, grasslands, and other ecosystems into energy crop plantations can have profound ecological impacts, including biodiversity loss, soil erosion, nutrient depletion, and altered water cycles. Recent literature emphasizes that intensive biomass cultivation without proper safeguards may lead to deforestation and habitat destruction, undermining long-term ecological and climate benefits[44]. Sustainable land-use strategies such as agroforestry, integrated crop–livestock systems, and the use of marginal or degraded lands are recommended to mitigate these impacts. Policymakers and industry stakeholders are increasingly encouraged to adopt holistic, landscape-level planning and sustainability certification schemes that balance bioenergy production with ecosystem conservation and food production objectives.

Incorporating comprehensive socioeconomic and environmental assessments within biomass supply chain planning and development is thus crucial. Such assessments ensure balanced trade-offs, promote sustainable agricultural practices, safeguard community livelihoods, and ultimately support equitable and environmentally sustainable bioenergy transitions.

Cross-study differences in functional unit (e.g., per MJ-LHV vs per Nm3-CH4), system boundary (gate-to-gate vs cradle-to-grave; treatment of biogenic CO2, land-use change), co-product handling (allocation vs system expansion), LCIA method (e.g., ReCiPe2016 vs TRACI 2.1), and data/temporal representativeness (electricity mixes, background databases) can shift absolute and relative results, limiting comparability and threatening both internal (method consistency) and external (transferability) validity[45]. To mitigate this, the approach: (i) tag each study's functional unit (FU), boundary, LCIA method, and data year; (ii) normalize TEA figures to a common currency year and finance/scale assumptions by referencing established frameworks (Zimmermann TEA/LCA guideline; DOE H2A; NREL TEA practice); and (iii) report ranges with explicit method notes where harmonization is not possible[46]. Prior harmonization efforts show that aligning such assumptions materially reduces unexplained variance, enhancing the decision usefulness of synthesized results.

-

The market for syngas as an intermediate in the chemical industry is anticipated to increase as a precursor to bulk chemicals, including methanol and biofuels from the Fischer–Tropsch process[47]. Biomass-derived syngas is primarily obtained through gasification. This process involves subjecting biomass to high temperatures (typically 700–1,200 °C) under limited oxygen or air conditions. Gasifying high-carbon-content solids like biomass produces synthesis gas, mainly composed of H2, CO, CO2, CH4, water vapor, N2, and undesirable tars as impurities[48]. High-quality syngas is characterized by a low tar content, a high H2 content, and a low nitrogen concentration.

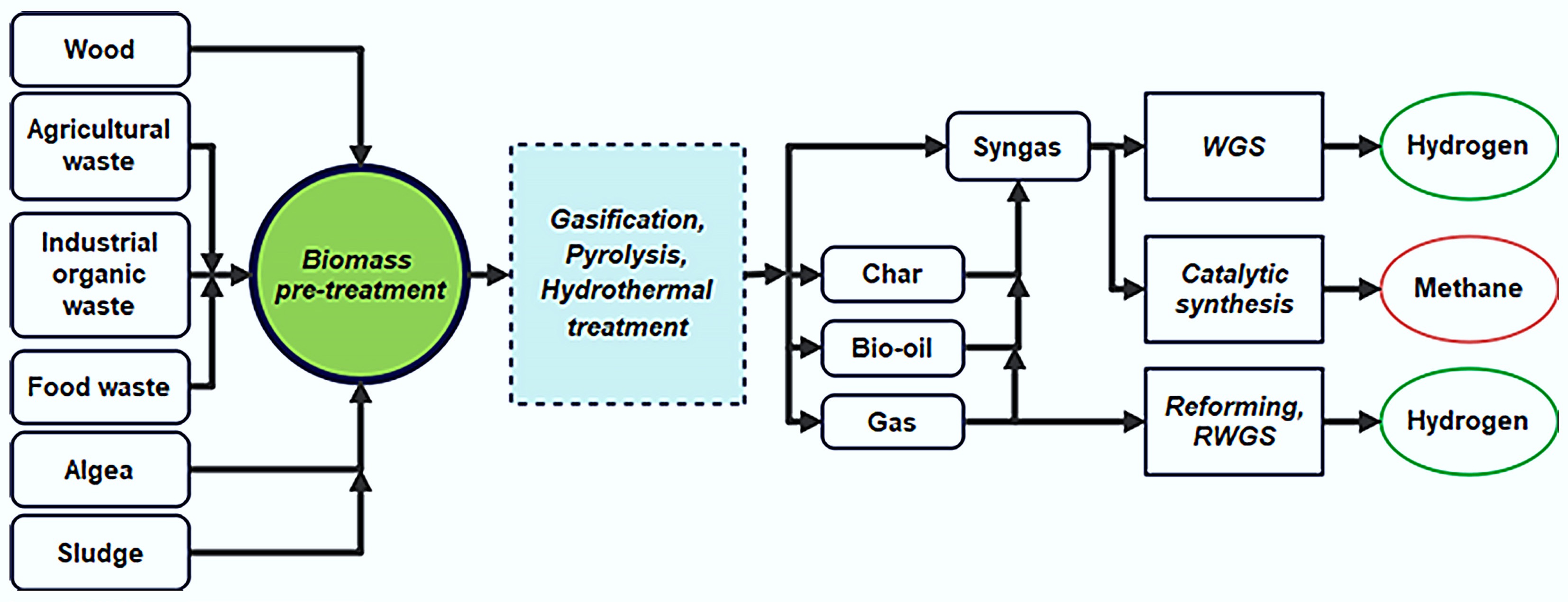

Various biomass feedstocks, including wood, agricultural residues, municipal solid waste (MSW), and energy crops like switchgrass or miscanthus, can be utilized for syngas production. Before gasification, biomass is typically dried and ground into small particles. The syngas production capacities of different feedstocks are illustrated in Fig. 2[7]. As shown, coal exhibits the highest syngas production capacity, exceeding 35,000 MWh, whereas petcoke and biomass/waste yield the lowest amounts.

Figure 2.

Syngas production capacities of various feedstocks. Redraw based on the data from Ahmad et al. [7].

Inside the gasifier, biomass undergoes a series of chemical reactions to produce syngas. Biomass-derived syngas offers significant advantages over fossil fuel-based methods, including reduced reliance on non-renewable resources and lower GHG emissions. It plays a crucial role in power generation through gas turbines, fuel cells, and steam turbines. Additionally, syngas serves as a key feedstock for producing H2 and various chemicals, such as urea, ammonia, methanol, dimethyl ether, and Fischer–Tropsch diesel, reinforcing its economic importance[49]. Beyond energy production, utilizing biomass feedstocks supports local agriculture and forestry industries, fostering economic growth within communities. The quality and yield of syngas are critical in determining its practical applications. Several factors influence its composition, including gasifier type, operating conditions, pressure, space velocity, gasifying agents, feedstock properties, particle size, and catalyst efficiency[48]. Optimizing these parameters is essential for producing high-quality syngas with minimal contaminants, such as tar and nitrogen, while maximizing H2 content. Advances in gasification technologies continue to enhance efficiency, solidifying syngas as a cornerstone of sustainable energy and chemical production.

Techno-economic analysis of bio-based syngas

-

The TEA of syngas, bio-based H2, and bio-based methane production from biomass typically involves the following steps, as listed in Table 3.

Table 3. A summary of parameters need to be considerd for conducing techno-economic analysis of syngas, bio-based H2, and bio-based methane production from biomass

Step Syngas Bio-based hydrogen Bio-based methane Comparison Ref. Biomass feedstock characterization Moisture content, ash content, and heating value Moisture content, ash content, and heating value Moisture content, ash content, and heating value Similar [50−52] Process design Gassifiaction: Feedstock properties and the desired syngas composition,gasifier type, operating conditions, and gas cleaning methods Gasification process design: feedstock properties, gasifier type, operating conditions, gas cleaning, H2 separation Drying, pyrolysis, and gasification: feedstock properties, gasifier type, operating conditions, gas cleaning Key difference: drying for methane; H2 separation for H2 [50] Product gas composition analysis Analyzed to determine its suitability for downstream applications Analyzed for H2 purity and downstream applications Analyzed for downstream applications Similar, with H2 requiring additional purity analysis [50] Capital cost estimation Based on the process design, equipment specifications, and installation costs Based on process design, equipment, H2 separation unit, installation costs Based on process design, equipment, installation costs Similar, with H2 including additional costs for H2 separation [50] Operating cost estimation Feedstock costs, energy costs, and maintenance costs Feedstock, energy, H2 separation, maintenance costs Feedstock, energy, maintenance costs Similar, with H2 including H2 separation costs [50] Revenue estimation From the sale of the syngas or downstream products From bio-based H2 or downstream product sales From bio-based methane or downstream product sales Similar [50] Sensitivity analysis Evaluate the impact of changes in key parameters, such as feedstock prices and product prices, on the economic viability of the process. Evaluates impact of feedstock and product price changes on viability Evaluates impact of feedstock and product price changes on viability Similar [50] The successful commercialization of biomass thermochemical conversion technologies is heavily influenced by their current TRLs, which provide a standardized scale to gauge technological maturity. These levels range from TRL 1 (basic research) to TRL 9 (fully commercial systems). For biomass-based gaseous fuel systems, most technologies operate within the TRL 3–8 range, with only a few reaching sustained commercial viability, as listed in Table 4.

Table 4. Technology readiness levels (TRL) of the technologies for producing biomass-based gaseous fuels

Technology Fuel type Current TRL Key barrier Estimated commercialization timeline Ref. Bubbling fluidized bed gasifier Syngas 7–8 Tar control, catalyst degradation 3–5 years [53] Steam reforming of bio-oil H2 5–6 Catalyst cost, scalability 5–8 years [38] Sorption-enhanced gasification H2 4–5 Process integration, CO2 handling 8–10 years [54] Supercritical water gasification (SCWG) Syngas/H2 4–5 High pressure equipment cost, limited demo data 8–12 years [55] Biomass methanation Methane 6–7 Ni-based catalyst deactivation, cost estimating 5–7 years [56] The configuration of biomass conversion systems, whether centralized or decentralized, plays a critical role in the economic and environmental performance of biofuel production. Logistics—including feedstock collection, transportation, storage, and preprocessing—account for a substantial share of both the cost and emissions associated with biomass-based systems[57]. Therefore, the system layout significantly influences the feasibility of thermochemical conversion technologies and applies broadly to all biomass-to-gas systems.

In recent years, numerous studies have focused on developing advanced technologies to enhance the utilization of renewable energy sources in response to climate change and the corresponding policies aimed at its mitigation. Biomass gasification is a promising pathway for producing energy, chemicals, and H2, offering a sustainable alternative to fossil-fuel-based processes. However, evaluating the TEA of these systems is critical, as multiple factors influence economic viability and energy efficiency. These factors include biomass quality, feedstock transportation, process efficiency, operational costs, and market conditions[58].

Colantoni et al. conducted a financial feasibility analysis of biomass-based combined heat and power (CHP) systems at three different scales: 100 kWth, 1 MWth, and 10 MWth. This study used a bubbling fluidized bed reactor, and the feedstock comprised various biomass types. Indicators such as Net Present Value (NPV), Internal Rate of Return (IRR), and Pay Back Period(PBP) were utilized in an economic feasibility analysis. The sensitivity of NPV was also compared through a risk analysis using the Monte Carlo Simulation. It was found that the most influential economic model parameters for sensitivity analysis were the biomass cost, the amount of synthesis gas, and the price of electricity sold. The probability of a system having a positive NPV ranged from 66% to 90%, and it increased with the size of the system. It has been established that using regionally procured biomass as a raw material and acquiring an energy green certificate from the resultant syngas would qualify the undertaking as a triumph[59].

Catalyst deactivation is a critical challenge in biomass thermochemical conversion, directly affecting system performance and economics. Common mechanisms include coke deposition, sintering, and poisoning from sulfur, chlorine, or alkali metals in feedstocks. Nickel-based catalysts, widely used for reforming and methanation, are particularly susceptible to carbon deposition, requiring regular regeneration and impacting operating costs[60]. Additionally, the reliance on rare or precious metals such as cobalt, rhodium, or ruthenium in advanced catalyst systems raises concerns about resource availability, supply chain risks, and increased capital expenditures[61]. Research is thus focusing on developing robust, earth-abundant alternatives and strategies to prolong catalyst life, such as doped supports and periodic oxidative regeneration. Comprehensive TEA should incorporate catalyst replacement intervals, regeneration costs, and market volatility of rare metals to accurately assess process sustainability.

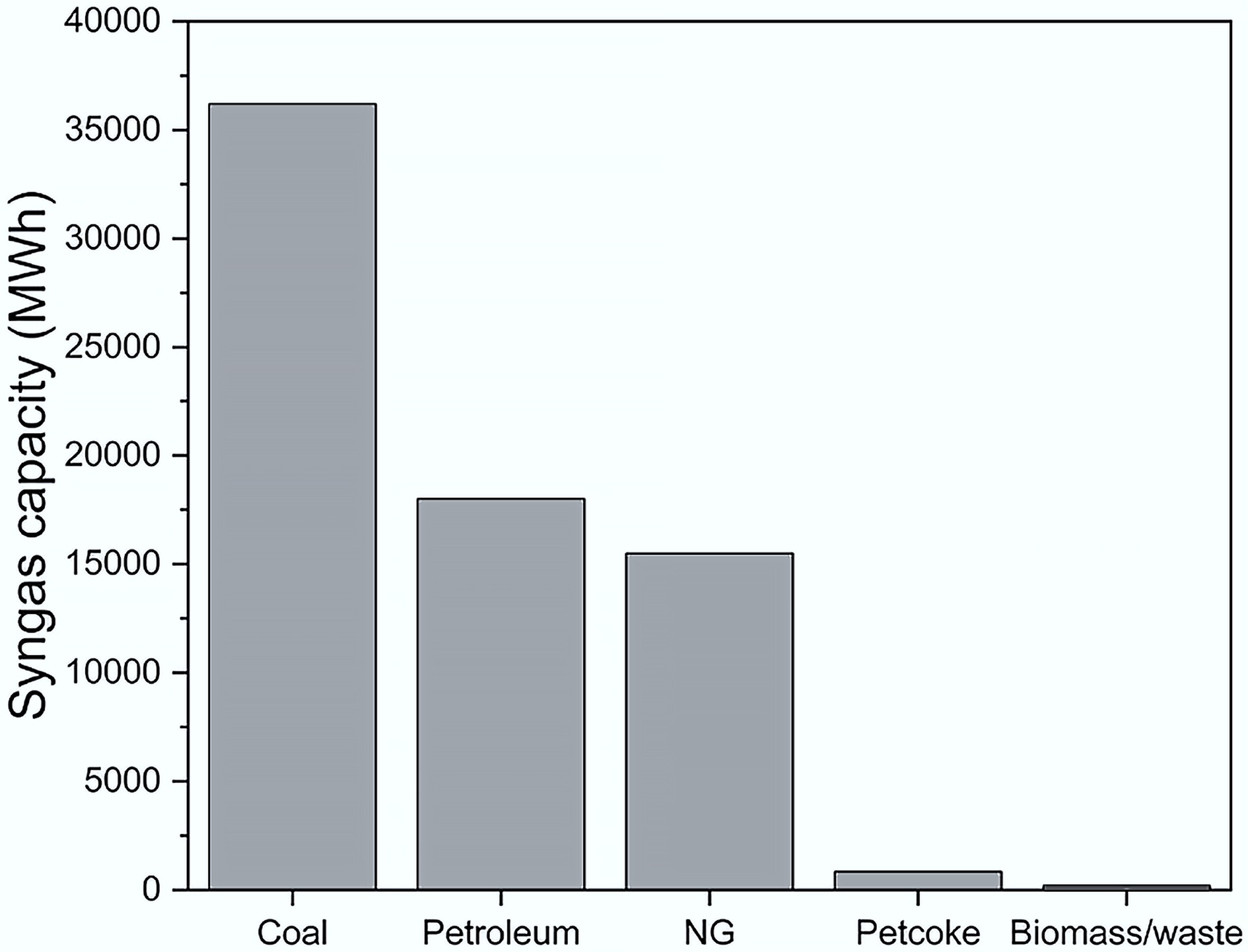

Sarafraz et al.[62] investigated the economic feasibility of a chemical looping gasification system using liquid indium as an oxygen carrier for syngas production. A TEA was conducted to evaluate cost-effectiveness and levelized energy costs under different pricing scenarios based on real-world market indices. The study analyzed a system capable of processing 110 t/d of carbon feedstock, optimizing process parameters to achieve a syngas quality score of approximately 0.5. The cost breakdown for the chemical looping gasification process with liquid metal oxide carriers (CLG-LMOC) is presented in Fig. 3[62]. It was determined that liquid metal handling represented a significant cost component, accounting for 49% of total equipment cost. Furthermore, fuel costs comprised 57.51% of the total annual cost, while equipment operation accounted for 40%.

Figure 3.

Price breakdown for syngas production by chemical looping gasification process with liquid metal oxide carriers (CLG-LMOC). Redraw based on the data from Sarafraz & Christo[63].

The cost breakdown shown in Fig. 3 is derived from a specific case study by Sarafraz et al.[62], which analyzed a chemical looping gasification system using a liquid medium as an oxygen carrier. It reflects the economic conditions, market indices, and operational factors particular to the studied region. Although the distribution of cost components, such as liquid metal handling (49%) and reactor operations (18%) offers valuable insights, it may not be universally applicable to regions with differing market conditions or feedstock prices. Variables like local energy costs, labor expenses, raw material availability, and regional regulations can significantly affect the cost structure. Therefore, while this breakdown is informative, it should not be broadly generalized without considering local contexts.

These findings underscore the importance of optimizing process conditions and reducing high-cost elements to improve the economic feasibility of biomass gasification. Integrating advanced gasification techniques and policy incentives, such as carbon credits and renewable energy subsidies, could further enhance the viability of biomass-based syngas production systems.

The supercritical water gasification (SCWG) method has received much attention in recent years due to its high energy conversion efficiency and environmental benefits. Meanwhile, the SCWG does not require a separate drying stage, saving cost and space. Additional economic evaluation is necessary to encourage the widespread development and commercialization of SCWG. In 1999, Amos refined the syngas produced at the starch waste SCWG plant using a complex membrane purification device[63]. The economic assessment found that the membrane unit accounted for over 35% of the total equipment cost. Table 5 provides an economic assessment of syngas production via SCWG.

Table 5. Economic analysis of various SCWG processes for syngas production

Year Category Targeted product Indicator Feedstock Capacity Result Ref. 2011 Fixed capital investment:

US${\$} $53.4 million ; US${\$} $TCI: 64.06 millionCH4 and H2 Annual net income Waste sludge 481 kg/h H2 Annual profit will be highest at US${\$} $3.78 /kg H2 selling price [67] 2012 Construction cost: US${\$} $16,169 /ha;

Labor cost: US${\$} $30,787 /ha/yr;

TPC: US${\$} $110,270 /ha/yrSyngas Syngas production cost Microalgae 86,500 t/d Updated syngas cost: US${\$} $79–129 /GJ [55] 2014 Indirect cost, O.C.,

Depreciation costSyngas Break-even prices for syngas, electricity Sugarcane

Bio-refinery residues1 kg/h syngas yield The break-even syngas price is lower than US${\$} $32.40 /MWh is profitable [68] Brandenberger et al. investigated the production of synthetic natural gas (SNG) via microalgal SCWG[55]. Their findings indicated that feed concentration was the most influential factor affecting SNG production costs. Under optimistic hypothetical conditions, where the SCWG plant had a microalgae treatment capacity of 86,500 t/d, the estimated cost range for SNG was US

${\$} $ ${\$} $ Several gasification technologies are employed for syngas production from biomass, but only the double fluidized bed (DFB) steam gasification technology has reached commercial-scale operation. Although extensive research and demonstration projects have been conducted, no full-scale commercial plants are currently operational. Numerous demonstration projects are in progress or in the planning phase, including GoBiGas, BioTfueL, Stracel BTL, Ajos BTL, Woodspirit, Enerkem's ethanol demonstration plant, and the TIGAS project[65]. These projects utilize different gasification technologies to produce various products, including liquid and gaseous fuels such as BioSNG and H2.

Plasma gasification exhibits considerable promise for syngas production from biomass. Ramos & Rouboa[50] reported a net energy output of 816 kWh/t of biomass, with conversion efficiencies ranging from 20% to 45%, substantially higher than the 2.7% efficiency of conventional gasification[66]. Additionally, the technology achieves a mass reduction rate of 90 wt.% and generates an annual revenue of approximately US

${\$} $ One of the key advantages of these gasification technologies is their high conversion efficiency, which can reach up to 70%[65]. However, challenges remain, particularly regarding H2 production, which requires further infrastructure development. While the transportation sector is gradually transitioning toward electric vehicles and H2 fuel, widespread adoption will take decades. As a result, hydrocarbons are expected to remain the dominant fuel source for the foreseeable future. Despite previous setbacks and industry failures, it is crucial to further develop syngas production technologies to reduce costs and improve economic viability.

Life-cycle assessment of bio-based syngas

-

The LCA of bio-based syngas production offers an in-depth analysis of its environmental impacts, focusing on critical sustainability indicators such as GHG emissions, acidification potential, eutrophication potential, and water usage. A detailed LCA evaluates the environmental consequences of syngas production across its entire life-cycle, encompassing biomass cultivation, harvesting, gasification, purification, and end-of-life waste management. The environmental performance of bio-based syngas is shaped by multiple factors, including the type of biomass feedstock, energy requirements, gasification technology, and overall process efficiency. By pinpointing environmental hotspots through LCA, opportunities for improvement can be identified, such as increasing energy efficiency, adopting carbon capture technologies, and sourcing biomass sustainably. Additionally, a comparative analysis between bio-based and fossil-derived syngas highlights the former's potential benefits, particularly in reducing carbon emissions and enhancing overall environmental sustainability. Performing an LCA for bio-based syngas production yields essential insights for policymakers, researchers, and industry stakeholders, supporting the shift toward more sustainable and eco-friendly energy systems. The LCA is typically divided into the following stages, as listed in Table 6.

Table 6. A summary of LCA steps of syngas, bio-based H2, and bio-based methane production from biomass thermochemical conversion

LCA step Syngas Bio-based hydrogen Bio-based methane Comparison/note Ref. Biomass feedstock acquisition and preprocessing Land, water, and energy

use for growth, harvesting, transport, drying; GHG and biodiversity impactsAs syngas; effects depend on H2 pathway selected (gasification, steam reforming) As syngas; for biogas/

biomethane, includes anaerobic digestion of waste or cropsAll rely on sustainable sourcing and transport minimization; cropping practice crucial [72] Conversion/

process stageGasification emissions

(CO2, CO, tars, particulates); electricity/fuel useGasification plus water-gas shift, H2 separation (membranes, PSA); added energy and chemicals Anaerobic digestion/followed by upgrading and possible methanation; methane slip and biogenic CO2 H2 route has higher process emissions and energy use; methane route increases risk of fugitive CH4 emissions [72] Product gas upgrading/

cleaningAcid gas removal (CO2, H2S),

tar cleanup, waste disposal impactsH2 purification to fuel cell or pipeline standards; impacts from separation units Upgrading biogas to biomethane purity (> 95% CH4); methane slip is critical LCA factor All require energy-intensive cleanup; H2 and biomethane purity requirements drive additional impacts [72] Distribution

and usePipeline or local use;

GHG savings depend on substitution (e.g., replacing fossil syngas)Similar; GHG impact determined by end use (fuel, chemical); negative emissions possible with carbon capture and storage (CCS) Grid injection or CNG; methane leakage and efficiency affect net GHG savings Biogenic routes generally yield lower GHG than fossil, but only if methane slip and H2 purification are managed efficiently [72] End-of-life/waste management Ash, char, tar reuse/disposal, water effluents; possible recycling or reuse of byproducts Similar, plus wastes from H2 separation materials Digestate use in agriculture, residual CO2 streams from upgrading H2 and methane pathways introduce separation wastes; all routes can benefit from optimal byproduct valorization [72] Overall GHG and environmental performance (summary) Significant GHG reduction vs fossil syngas, especially when using bio-waste; some trade-offs in land/water use H2 from biomass + CCS can be net negative GHG; LCA depends on full-system boundaries Biomethane can achieve deep decarbonization if methane slip minimized and digestate reused Best LCA results from waste-based feedstocks, strong methane management, CCS integration for negative emissions [72] Syngas, which is H2-rich, is considered one of the cleanest energy sources, producing the fewest GHGs. Several studies have investigated the environmental impact of producing H2-rich syngas from various biomass types[69]. Biomass pyrolysis produces the highest CO2 equivalent emissions among the thermo-catalytic processes for producing H2-rich syngas[70]. Yet, due to variations in machinery, process conditions, and feedstocks, it is impossible to compare the environmental impact of these various processes directly. According to Dufour & Moreno, the CO2 equivalent emissions can be decreased by combining the water-gas-shift reaction with the reforming process[71].

Carpentieti et al.[73] studied the LCA of an integrated biomass gasification combined cycle (IBGCC) for the production of syngas. The LCA demonstrates the significant environmental benefits of biomass utilization, including mitigating GHG emissions and preserving natural resources. With a fixed CO2 removal efficiency of 80%, modelling an IBGCC + DeCO2 yielded an intriguing 33.94% cycle efficiency and specific CO2 emissions of 178 kg CO2/MWh. Due to the low efficiency of the IBGCC + DeCO2 and the significant impact of energy crop cultivation, the results for the other indicators indicate values that are slightly higher than the ICGCC + DeCO2[73]. For system-scale LCA, modeled BECCS yields ~850–900 kWh per tCO2 captured, while DAC requires ~350–600 kWh and ~5.4–7.1 GJ heat per tCO2; net-negative cases imply ~0.3–1.1 GtCO2/yr storage (–0.85) and ~4 GtCO2/yr (–3.9) in 2050 EU scenarios[74].

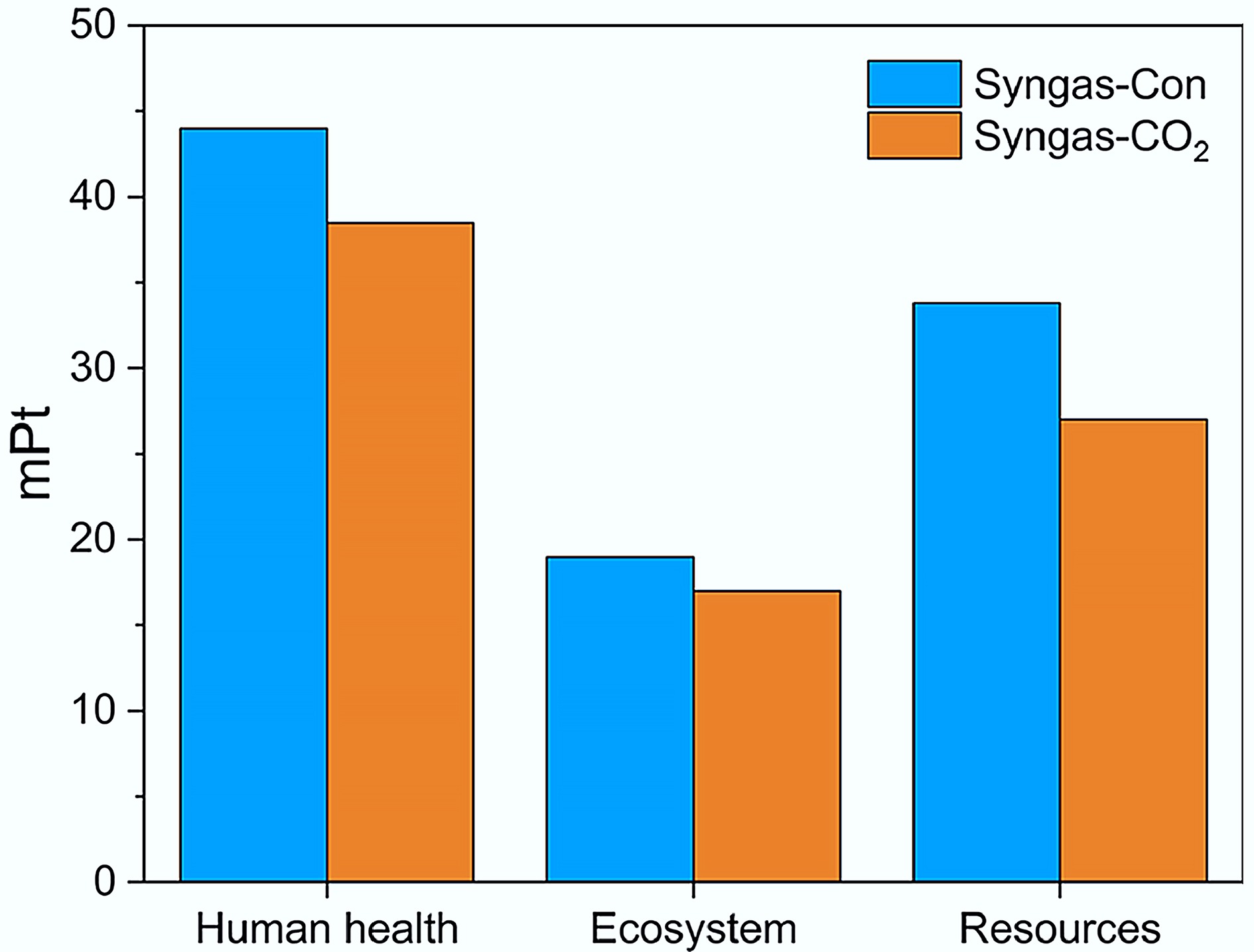

The environmental impact of syngas production through air, steam, and CO2-enhanced gasification was analyzed by Parvez et al.[75]. The study showed that CO2-enhanced gasification had fewer adverse environmental effects than traditional gasification. When considering the environmental impact of a process, CO2 emissions are typically a primary concern. While CO2-enhanced gasification had a lower energy footprint than conventional gasification, it resulted in larger consequences in the middle-ground category, particularly in terms of human toxicity and marine ecotoxicity. As shown in Fig. 4, conventional biomass gasification had a greater effect on resource consumption, whereas its impact on human health and ecosystems was less significant[75].

Figure 4.

Environmental impact caused-conventional biomass gasification (Syngas-Con) and CO2-enhanced biomass gasification (Syngas-CO2). Redraw based on the data from Parvez et al.[76].

Ramos & Rouboa[50] underscore the potential of plasma gasification for syngas production from biomass, highlighting its environmental and economic advantages through a life cycle thinking (LCT) approach that encompasses LCA, life-cycle costing (LCC), and social life-cycle assessment (S-LCA). From an LCA standpoint, plasma gasification of biomass yields a global warming potential (GWP) ranging from –31 to 422 kg CO2 equ., which is comparable to conventional gasification (27 to 104 kg CO2 equ.) and pyrolysis (–1 to 151 kg CO2 equ.)[76].

Shen et al. measured particulate matter (PM) emissions in CO2-enhanced biomass gasification, finding a 75.4% reduction in PM emissions at a 15% CO2 addition[77]. An environmental investigation using Aspen Plus software also revealed that CO2-enhanced biomass gasification reduced environmental impacts compared to traditional biomass gasification, especially regarding human toxicity and ecotoxicity[75]. Gu & Bergman[78] conducted an LCA of GHG emissions from electricity generated by syngas produced from woody biomass. Their study found that the conversion of woody biomass into medium-energy syngas in a high-temperature, low-oxygen environment, followed by combustion to produce electricity, had a significantly lower global warming potential than energy from bituminous coal (1.08 kg CO2-eq/kWh) or conventional natural gas (0.72 kg CO2-eq/kWh), with a global warming impact value of just 0.142 kg CO2-eq/kWh[78].

Voultsos et al. assessed the proposed cogeneration biomass gasification facility in Thessaly, Greece, for its energetic and environmental performance using a combination of process modelling and the LCA technique. When the gasification model was expanded to a 1 MWel and 2.25 MWth CHP facility, its Global Warming Potential (GWP) and Cumulative Demand for Non-Renewable Fossil Energy were analyzed as part of a 'cradle-to-gate' LCA. Plant operation was found to lower GHG emissions by around 0.6 kg CO2-eq/kWhel and save roughly 10 MJ/kWhel of non-renewable energy under all test conditions[79].

Integrating LCA with LCC analysis for bio-based syngas production enables a holistic evaluation, balancing environmental impacts like GHG emissions with economic costs, ensuring sustainable and cost-effective energy solutions. The LCC analysis of thermochemical syngas production from biomass provides a comprehensive economic assessment of this renewable energy process, covering feedstock acquisition, plant construction, operation, and eventual decommissioning. Thermochemical syngas production primarily involves biomass gasification, where lignocellulosic materials such as forestry residues, agricultural wastes, or energy crops are converted into a gaseous mixture of CO, H2, and CO2 at high temperatures (typically 700–1,000 °C)[80]. Capital costs are a major component of the LCC, with gasification facilities requiring investments of US

${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ Table 7. Comparison of syngas production cost and GWP for different technologies

Process type Feedstock/context Syngas production cost (US${\boldsymbol\$} $/GJ) GWP (kg CO2-eq per kg syngas) Ref. Indirect steam DFB gasification Woody biomass − ~2–5 depending on electricity GWI [85] Stand-alone biomass syngas plant Lignocellulosic biomass 8.22–6.73 − [86] Pulp-mill integrated biomass gasification Forest residues 17 − [87] Mill-gas separation (COG H2 + BOFG CO) to syngas Steel mill off-gases − 0.7–3.6 (pathway and electricity carbon intensity dependent) [88] Micro-scale biomass gasification Various residues 5–54 − [89] Across studies, levelized costs pivot on feedstock logistics and gas cleanup, while LCA swings with electricity mix and methane/tar management. CCS and waste-based feedstocks frequently flip GWP from positive to near-neutral/negative. At TRL 7–8 (indirect steam gasification), near-term wins lie in tar control and heat integration; policy levers (e.g., carbon price, renewable gas credits) strongly affect bankability. Decision-relevant range: syngas GWP improves most when the cleanup energy is low-carbon and when co-products (biochar) are valorized.

The results of the LCA and LCC can be used to identify areas where improvements can be made to reduce the environmental impact of syngas production from biomass. For example, the LCA may identify opportunities to reduce energy consumption, switch to renewable energy sources, or improve waste management practices. Overall, the LCA of syngas production from biomass provides essential information for decision-makers, stakeholders, and investors to evaluate the environmental sustainability of the process and make informed decisions about its implementation. Hence, enhancing the production process is a viable option for reducing CO2 equivalent emissions.

-

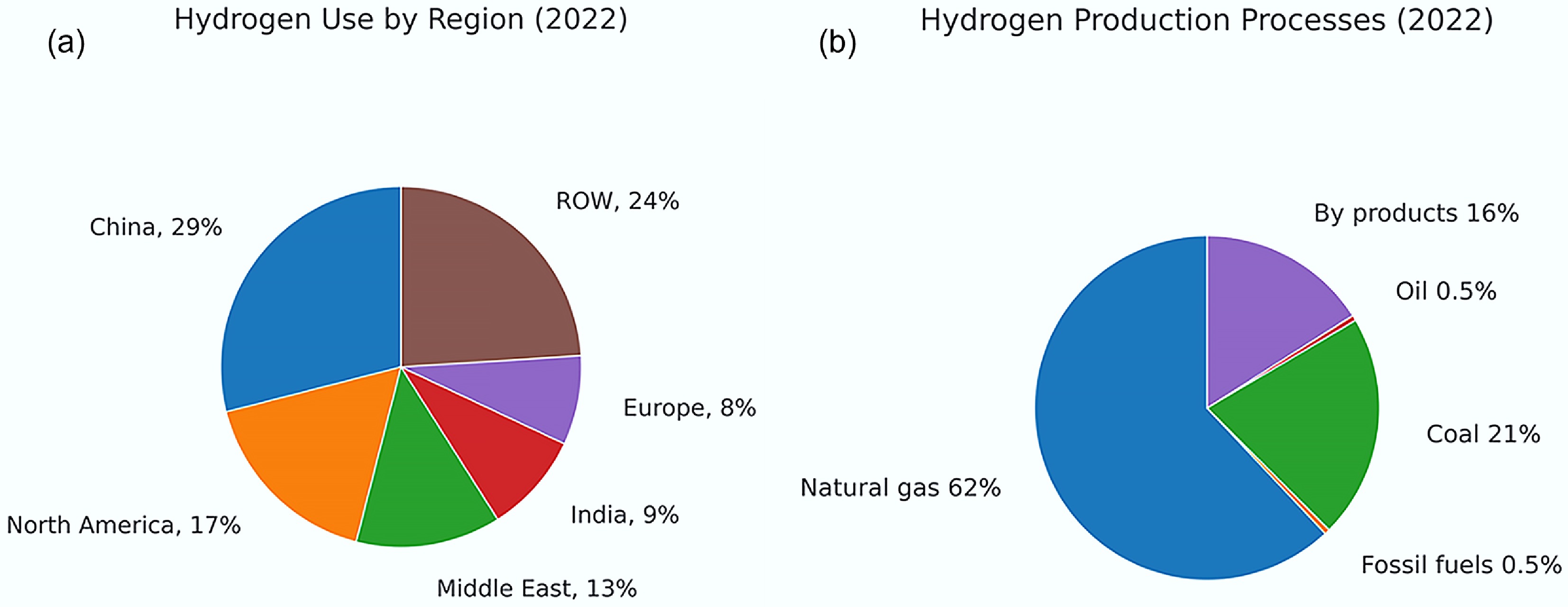

The development of sustainable fuels is critical for addressing the global challenges of climate change, energy security, and transitioning to a low-carbon economy. H2 is widely considered a highly efficient and environmentally friendly energy carrier because only water is produced from H2 combustion. It is a carbon-free energy carrier and has the highest known energy density among common fuels, at 142 kJ/gal[90]. H2 energy has the potential to decarbonize several sectors, including industry, transportation, and energy storage. Worldwide, H2 production might reach 10 EJ/year in 2050, up from 7.7 EJ/year in 2017[91]. Figure 5 shows the primary application regions of H2, which include China (29%), North America (17%), the Middle East (13%), and others (42%)[92]. Furthermore, the H2 industry is expected to grow at an annual rate of 5%–10% in the coming years, primarily due to its use in oil refineries for processing heavy oil fractions and its anticipated role in the transportation sector or as an energy carrier[93]. Currently, 96% of the produced H2 is based on non-renewable resources[94]. Natural gas (62%) and oil reforming (0.5%) are the most common methods, followed by coal gasification (21%). According to Fig. 5, the production of H2 through water electrolysis accounts for a mere 0.4%[92].

Figure 5.

(a) Major application regions, and (b) production processes of H2 in 2022. Redraw based on the data from IEA[93].

Biomass is emerging as a promising sustainable feedstock for H2 production, harnessing thermochemical processes such as steam gasification, supercritical steam gasification, bio-oil reforming, and pyrolysis[38]. Globally, approximately 181.5 billion tons of lignocellulosic and agricultural biomass are produced; however, a minor proportion of this biomass undergoes processing and repurposing, resulting in substantial quantities of organic waste (equivalent to 40%−50% of its initial mass) being deposited into the environment[95]. Today's food systems result in massive volumes of wasted food; the United States (U.S.) alone produces over 50 Mt of food waste per year[96]. Employing renewable biomass materials in H2 production mitigates their inherent uncontrolled decomposition and the environmental risk of climate change[97]. This approach aligns with broader trends in sustainable fuel development, where bio-based H2 is increasingly seen as a crucial component in achieving a net-zero future. By linking biomass conversion technologies to the H2 economy, this paper offers insights into how sustainable fuels can play a pivotal role in the broader energy transition.

Importance of bio-based hydrogen

-

The thermochemical conversion of biomass offers a sustainable and carbon-neutral method for H2 production, tackling two significant issues: decreasing reliance on fossil fuels and reducing GHG emissions. The production of H2 from biomass presents a promising avenue for reducing carbon emissions in sectors that are challenging to electrify, including heavy industry and long-distance transport. The incorporation of H2 into energy systems plays a vital role in achieving the ambitious climate goals established by international accords like the Paris Agreement, which seeks to restrict global warming to 1.5 °C. In this context, the capacity of biomass conversion technologies to produce low-carbon H2 via sustainable methods emerges as a crucial element of future energy systems[98].

The global shift towards an H2 economy is accelerating, particularly with Europe at the forefront of this movement. The H2 strategy of the European Union, especially within the framework of the RePowerEU plan, presents a detailed roadmap aimed at deploying 40 GW of electrolyzers by 2030 for the production of renewable H2, emphasizing the integration of H2 across multiple sectors[99]. Nonetheless, a significant challenge in the production of green H2 through electrolysis is the reliance on renewable electricity, which may not consistently be accessible in adequate amounts. H2 production from biomass presents a valuable approach by utilizing a renewable feedstock that can function autonomously or alongside renewable electricity, thereby guaranteeing a consistent H2 supply. Furthermore, integrating biomass conversion with carbon capture and storage technologies can significantly improve its environmental impact, facilitating negative emissions and aiding in the achievement of net-zero objectives[100].

The environmental advantages of biomass-derived H2 production are significant, especially in contrast to traditional H2 production techniques. The conventional method of producing H2, mainly via steam methane reforming (SMR) of natural gas, leads to considerable CO2 emissions. Conversely, thermochemical processes utilizing biomass, especially when combined with carbon capture and storage, can lead to a net decrease in CO2 emissions, thereby rendering H2 produced from biomass carbon-negative[101]. This holds particular significance in the realm of challenging sectors like cement, steel, and chemicals, where H2 can serve as a substitute for fossil fuels, thereby diminishing their carbon emissions. In the industrial sector, H2 is becoming a crucial tool for decarbonization, and biomass conversion is poised to significantly contribute to fulfilling the H2 needs of these industries[102].

The significance of H2 in the transportation sector is growing, especially for applications where battery-electric solutions prove impractical, including long-haul trucking, shipping, and aviation. Hydrogen fuel cells, utilizing H2 derived from biomass, offer a zero-emissions alternative to diesel engines in these sectors, contributing to global initiatives aimed at lowering transport emissions[103]. Studies indicate that hydrogen fuel cells provide greater energy density and range than battery-electric options, rendering them more appropriate for heavy-duty and long-range uses. Additionally, H2 produced from biomass can be incorporated into current infrastructure, minimizing the necessity for expensive new energy systems[101].

A notable benefit of biomass-based H2 production is its potential for implementation in areas where renewable energy sources such as wind and solar are scarce. Biomass is abundantly accessible in numerous regions globally, presenting a compelling opportunity for decentralized H2 production, especially in rural and agricultural areas. This approach can strengthen energy security by decreasing reliance on imported fossil fuels and ensuring a consistent, locally sourced energy supply. Furthermore, the production of H2 from biomass has the potential to enhance rural economic development by establishing new markets for agricultural residues and various organic waste materials[102]. This method promotes a circular economy by transforming waste into valuable energy resources, which is in line with global sustainability objectives.

From an economic standpoint, the viability of converting biomass through thermochemical processes into H2 is gaining significant competitiveness. The review emphasizes that advancements in thermochemical processes, including enhancements in gasification efficiency and the incorporation of carbon capture and storage (CCS), are reducing the costs associated with H2 production from biomass[1]. When external factors like carbon pricing and environmental benefits are taken into account, biomass-based H2 demonstrates the potential to compete with alternative H2 production methods, such as electrolysis. Furthermore, the advancement of hybrid systems that integrate biomass conversion with renewable energy sources has the potential to significantly improve the cost-effectiveness and sustainability of H2 production[104].

The incorporation of H2 into the broader energy framework, especially via power-to-H2-to-power systems, presents a noteworthy opportunity for H2 derived from biomass. In these systems, surplus renewable electricity is utilized to produce H2 via electrolysis, allowing for storage and subsequent conversion back into electricity during periods of low renewable production. H2 derived from biomass can enhance this strategy by offering a consistent supply that remains unaffected by weather variability, thereby ensuring the reliability and stability of the energy system[98]. The adaptability of biomass-derived H2 positions it as a significant resource for stabilizing variable renewable energy sources such as wind and solar.

As progress continues, the advancement of sustainable fuels, such as H2, will remain a crucial priority for policymakers, experts, and industries across the globe. The review highlights biomass thermochemical conversion as an essential element of the future H2 economy. With the increasing scale of H2 production from renewable sources, biomass is set to be a vital component in supporting various H2 production methods, thereby contributing to a diverse and robust energy supply[52]. The ongoing progress in biomass conversion technologies, along with favorable policies and investments, will be crucial for unlocking the full potential of biomass-based H2 in meeting global decarbonization objectives.

The techno-economic potential for biomass thermochemical conversion into H2 is gaining competitiveness as a result of technological advancements and improved process efficiency. Considering the implications of carbon pricing and the environmental advantages associated with negative emissions, biomass-derived H2 emerges as a competitive option against alternative H2 production techniques, including electrolysis and steam methane reforming with carbon capture and storage[52]. This production pathway also generates economic opportunities in rural regions, enabling the conversion of agricultural and forestry residues into valuable energy products, thereby fostering economic development and job creation[101]. This is in accordance with worldwide initiatives aimed at facilitating a fair shift to a low-carbon economy, ensuring that the advantages of clean energy are distributed equitably[98].

Techno-economic analysis of bio-based hydrogen

-

The sustainability of the H2 economy and the future of clean energy hinge on the development of adaptive and environmentally benign methods for H2 production. As discussed in TEA of bio-based syngas, H2 production technologies such as steam reforming and sorption-enhanced gasification (SEG) remain in mid-development stages (TRL 4–6), affecting their current economic viability and scalability. The configuration of biomass conversion systems, whether centralized or decentralized, plays a critical role in the economic and environmental performance of biobased H2 production, as discussed in a previous section. Traditional H2 production methods, such as steam methane reforming (SMR) of natural gas and coal gasification, are increasingly unsuitable for a circular economy due to their energy-intensive processes and high carbon emissions, which amount to approximately 830 million tons per year[105]. As the global demand for H2 rises, especially in the context of decarbonization strategies, the need for alternative production methods has become pressing. The utilization of renewable resources, particularly organic residual biomasses such as food wastes, lignocellulosic agricultural residues, and forestry waste, offers one of the most promising alternatives to these conventional methods[106].

For H2 to be commercially viable as a clean fuel, it is essential that its production methods are both sustainable and cost-competitive. The scalability and processing reliability of bio-based H2 production are crucial to reducing production costs and driving broader adoption. Several factors contribute to the overall economics of bio-based H2, including: (a) substrate/feedstock and pretreatment costs, (b) production costs of H2, (c) downstream purification and processing costs, (d) storage and transportation costs, and (e) distribution costs[107]. While thermochemical H2 production technologies such as gasification and pyrolysis are productive and can yield high-purity H2, they are often not economically viable without significant improvements in energy efficiency due to their high energy consumption[106].

H2 commercialization has progressed considerably due to advances in various production technologies. These include water electrolysis, steam reforming, and coal gasification, each of which has been extensively applied in industrial settings[108]. However, as H2 production from biomass is explored more extensively, it has been found that the cost of H2 produced through gasification of biomass remains relatively high compared to conventional methods. For example, a study by Liu et al. reported that the levelized cost of hydrogen (LCOH) from MSW gasification was US

${\$} $ ${\$} $ Further analysis revealed that LCOH for MSW gasification was calculated at GBP 2.22 /kg, and for waste wood gasification, it was GBP 2.02 /kg. This cost disparity underscores the economic challenge faced by biomass-derived H2. Liu et al. evaluated five different scenarios for H2 production: (S1) gasification of MSW, (S2) gasification of waste wood, (S3) dark fermentation of wet waste or sludge, (S4) combined dark and photo fermentation of wet waste or sludge, and (S5) steam methane reforming (SMR) of natural gas. Among these, biomass-based H2 production through gasification (S1 and S2) was more expensive compared to SMR, but dark fermentation (S3) and combined fermentation (S4) showed some potential for reducing costs, particularly when compared to more conventional methods[109].

The techno-economic feasibility of SEG for H2 production was also investigated. Santos & Hanak[54] found that this method led to a higher LCOH of US

${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $

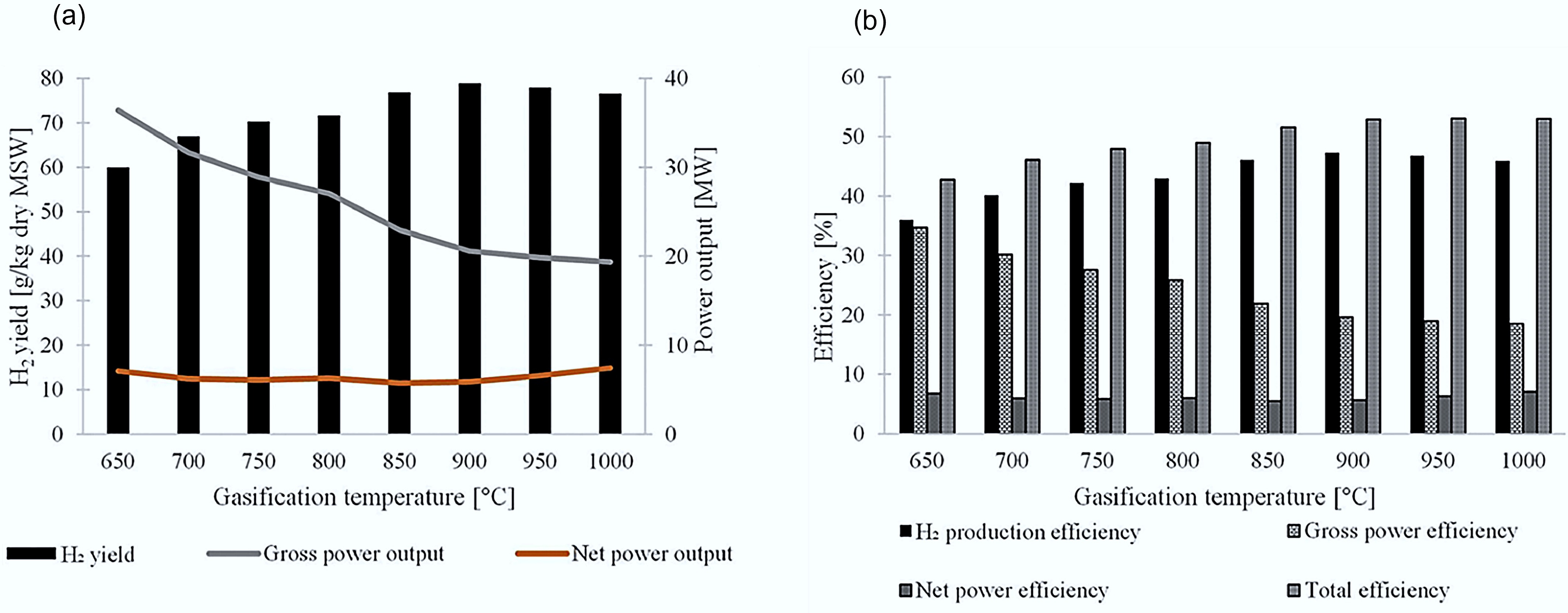

Figure 6.

The influence of gasification temperature on H2 product yield and process efficiencies[54].

The pyrolysis process, another thermochemical method for converting biomass into H2, also presents an alternative to gasification. Pyrolysis offers advantages such as lower operating temperatures and the potential for producing valuable byproducts, but like other thermochemical processes, it still faces challenges in terms of cost competitiveness with more established H2 production methods. The economics of pyrolysis-based H2 production, while promising, require further investigation and optimization, especially concerning the integration of CCS to mitigate the environmental impact.

However, the production of H2 via biomass pyrolysis is still in the early stages, with a TRL between 3.5 and 4.2 (laboratory scale). This relatively low TRL reduces production efficiency and increases associated costs[110]. To enhance the scalability of the process, improving H2 yields from biomass would be crucial for reducing both capital and operating expenditures.

Capital expenditures (CAPEX) for biomass pyrolysis encompass both direct costs, such as instrumentation, equipment type, installation location, and electrical control systems, as well as indirect costs, which include construction and engineering expenses[111]. Operating expenditures (OPEX), on the other hand, include variable costs such as biomass feedstock transportation, raw material pricing, chemicals, and energy consumption. Additionally, fixed costs, such as administrative, labor, and maintenance expenses for the pyrolysis plant, must also be considered[111].

A TEA study on the hydropyrolysis of woody biomass for biofuel production estimated the minimum fuel selling price (MFSP) at US

${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ H2 production costs must be below or close to US

${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ Table 8. Techno-economic comparison of different H2 production processes

Process type Feedstock Capital expenditure

(M US${\boldsymbol\$} $)Hydrogen

production cost (US${\boldsymbol\$} $/kg)Levelized cost of hydrogen (US${\boldsymbol\$} $/kg) GWP

(kg CO2 eq/kg H2)Ref. Biomass Gasification and steam reforming Solid waste 399.2 2.26 3.04 4.4–7.72 [109,116] Waste wood 137.65 2 2.77 0.18–6.98

(–24.19 with CCS)[109,116] Wood chips 12.5 1.83–2.35 n.a. 0.18–6.98

(–24.19 with CCS)[116] Dark fermentation Wet waste, sludge 38.162 2.38 2.945 n.a. [109] Dark and photo fermentation Wet waste, sludge 41.642 2.52 3.137 n.a. [109] Pyrolysis Bio-nut shell, olive husk, black liquor, pulp and paper waste 264.6–361.6 1.21–2.57 n.a. n.a. [117] Supercritical water gasification Black liquor 72.37 1.51–3.89 n.a. n.a. [118] Fossil resources SMR Natural gas 215.4–302.65 0.77 1.45–2.56 10–16 [117] SMR with CCS Natural gas 2–2.4 3–10 [119,120] Coal gasification Coal 324.57 0.92–2.83 1.26 19.25–23 [117] Coal gasification with CCS 1.51 4.85–11 [121] Non-biobased renewables H2 electrification Renewable energy 2.9–6.7 0.49–6.63 [119,120] The world's largest economies, particularly China, the United States, Japan, and India, have been pivotal in supporting the development of H2 fuel production[122]. China, as the leading market for bio-H2, anticipates that the sector's production value will reach US

${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ The H2 economy holds immense potential to mitigate GHG emissions and reduce pollution, thereby playing a crucial role in achieving the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). By promoting the adoption of eco-friendly technologies and fostering environmentally conscious production methods, the H2 economy contributes to environmental preservation and long-term sustainability[126]. If effectively implemented, this transition can support sustained economic growth while easing the burden on natural resources, establishing a solid foundation for social sustainability. However, for this to be realized, it is imperative to lower processing costs. This will require the continued development and scaling up of new technologies, such as integrated bioprocessing, to enhance the efficiency and economic feasibility of bio-H2 production.

Life-cycle assessment of bio-based hydrogen

-

LCA is a crucial methodology for systematically evaluating the environmental, economic, and social impacts of products, processes, and activities, including H2 production, biofuel synthesis, power generation, and energy systems. LCA provides a structured analytical framework that identifies both direct and indirect inputs and outputs, assesses energy and material flows, and quantifies environmental impacts throughout the entire life cycle of a product. This approach also helps identify potential areas for improvement in process optimization and policy implementation[127].

The LCA methodology is standardized under ISO 14040:2006 and ISO 14044, which define four key stages: (1) goal and scope definition, (2) life-cycle inventory analysis (LCI), (3) life-cycle impact assessment (LCIA), and (4) interpretation of results[128]. The goal and scope definition phase establishes the purpose of the LCA, system boundaries, functional unit, geographical scope, and temporal considerations. The LCI phase involves quantifying all material and energy inputs, emissions, and waste outputs across the system. The LCIA phase evaluates the potential environmental impacts associated with resource use, GHG emissions, and energy consumption. Finally, the interpretation phase ensures that the results align with the study's objectives and provides recommendations for process improvement and policy development.

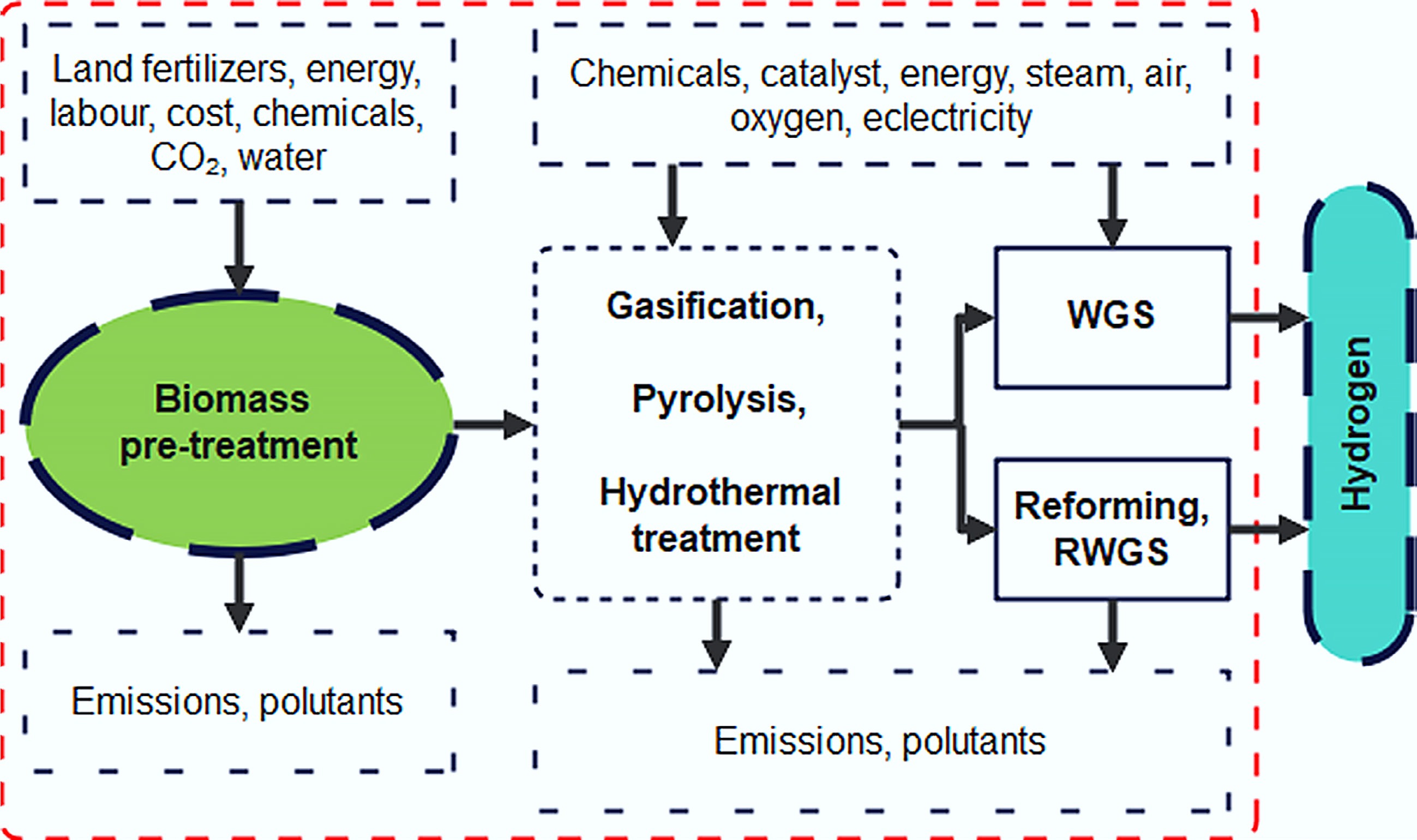

A cradle-to-grave LCA of bio-based H2 must consider multiple process steps, including raw biomass production, pretreatment, collection, transportation, syngas production, H2 purification, distribution, and end-use applications. Each of these stages contributes to the overall environmental impact and energy efficiency of the H2 production system[129]. A schematic diagram of the LCA approach is shown in Fig. 7.

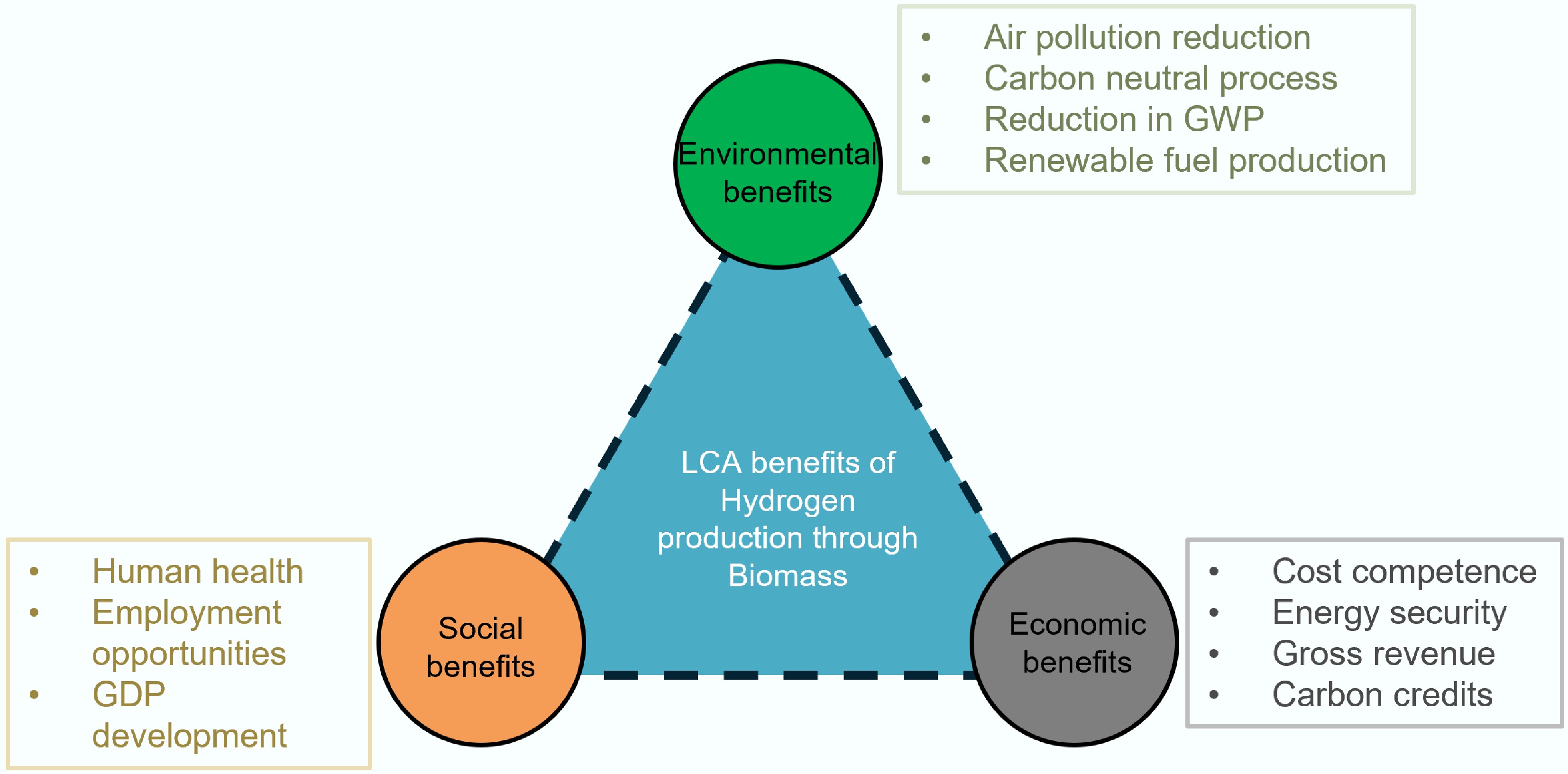

The analysis indicates that in the near term, bio-H2 produced through biomass gasification is unlikely to fully replace conventional H2 due to various economic and social barriers. Nonetheless, improving process efficiency can strengthen the sustainability of bio-H2 production, addressing economic, environmental, and social factors. By employing cost-effective measures and leveraging carbon credits, conducting a thorough LCA of bio-H2 production can support the global shift toward renewable energy systems and net-zero emission targets, as depicted in Fig. 8. Despite its potential, bio-H2 production from biomass faces notable challenges, such as the need for expensive catalysts, the production of multiple by-products (including CO2 and H2), and, in some cases, liquid-phase by-products[93].

To overcome these limitations, expanding traditional LCA with a broader life cycle sustainability assessment (LCSA) is necessary. Unlike standard LCA, LCSA evaluates not only environmental impacts but also economic and social consequences. This comprehensive approach can reveal inefficiencies in operations, potential health risks, and pollution issues linked to bio-H2 production[130]. Moreover, LCSA can promote improved resource management, community participation, knowledge exchange, safer living conditions, cost savings, responsible technology adoption, and infrastructure development.

Environmental impacts of bio-H2 production are primarily assessed through two indicators: acidification potential (AP), mainly due to SO2 emissions that contribute to acid rain, and GHG emissions, largely CO2, associated with global warming potential[131]. A meta-analysis suggested that H2 production from biomass can lower GHG emissions by up to 75% compared to the natural gas reforming process[132]. Valente et al.[116] aimed to standardize LCA studies to better compare AP, cumulative non-renewable energy demand (CEDnr), and GHG emissions. Their research showed that biomass-based H2 production produces fewer GHG emissions, particularly when coupled with CCS, which can even achieve negative emissions due to carbon absorption during biomass growth. An overview of the global warming potential of various H2 production pathways is shown in Table 8.

The H2 was produced by using coal-to-H2 (CTH) and biomass-to-H2 (BTH) processes. When compared to producing H2 from coal, biomass-to-H2 methods score better on many relevant LCA indicators. The life cycle boundaries of the system include transportation, syngas synthesis, H2 purification, and its applications. The energy consumption data for H2 production indicate that H2 produced from biomass requires roughly 25% less energy than H2 produced from coal[133]. Furthermore, transporting H2 through pipelines is a more eco-friendly option, as it minimizes GHG emissions[133]. However, the economic feasibility of bio-H2 production from residual biomass remains uncertain. Despite the projected global market for H2 reaching US

${\$} $ Combining LCA and LCC for bio-based H2 production through thermochemical biomass conversion allows for a thorough assessment of both environmental impacts and economic feasibility, promoting efficient resource use and minimizing overall costs. The process typically involves biomass gasification to produce syngas, followed by water-gas shift reactions and H2 purification (e.g., pressure swing adsorption or membrane separation) to produce high-purity H2.

Gasification plants requiring investments of US

${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ Compared to fossil-based H2 production via steam methane reforming (US

${\$} $ ${\$} $ Biomass-based H2 production can potentially reduce GHG emissions by up to 90%, depending on the production site's conditions and system boundaries. However, the effectiveness of this approach depends significantly on the type of biomass used. Utilizing high-yield biomass sources like eucalyptus can lead to better economic and environmental results[136]. Integrating advanced assessment methods like exergy analysis with LCA could provide more accurate insights into the sustainability of H2 production pathways, helping to develop more efficient and sustainable technologies[137]. TEA is dominated by separation and purification and catalyst life; LCA is dominated by capture rate and electricity carbon intensity. Biomass-to-H2 + CCS can be net-negative but requires durable WGS/PSA trains and steady feedstock. With current TRL ~4–6 for several routes, market access hinges on hydrogen offtake contracts and carbon policy; near-term pilots should target gate-fee feedstocks and heat recovery to compress LCOH ranges.

-

Methane is recognized as a cleaner alternative to conventional fossil fuels such as oil and coal. It is commonly used as a fuel alongside Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) in internal combustion engines[138]. In 2022, Europe emerged as the largest producer of bio-based methane, producing approximately 1.8 million tons annually[139]. Methane has diverse applications across residential and industrial sectors, including its use in transportation, electricity generation, and as a key component in fertilizer production[140].

The global methane market, which was valued at approximately US

${\$} $ ${\$} $ The adoption of biogas technology has seen substantial growth in recent years. In the European Union, the number of biogas plants increased from 10,508 in 2010 to approximately 19,000 by 2020, with 880 facilities specifically dedicated to biomethane production[143]. Similarly, in China, as of 2020, there were 172 biomethane plants and 3,150 biogas plants in operation[144].

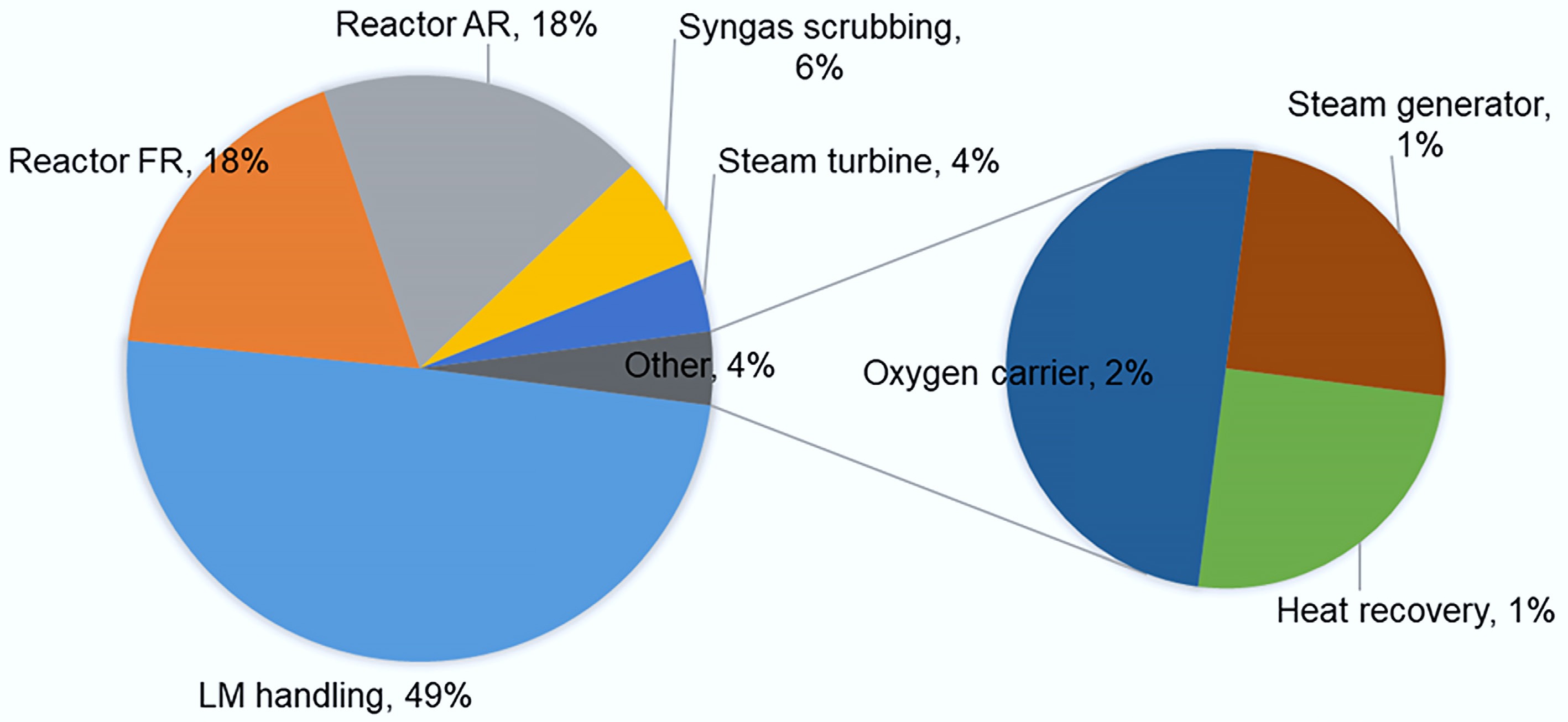

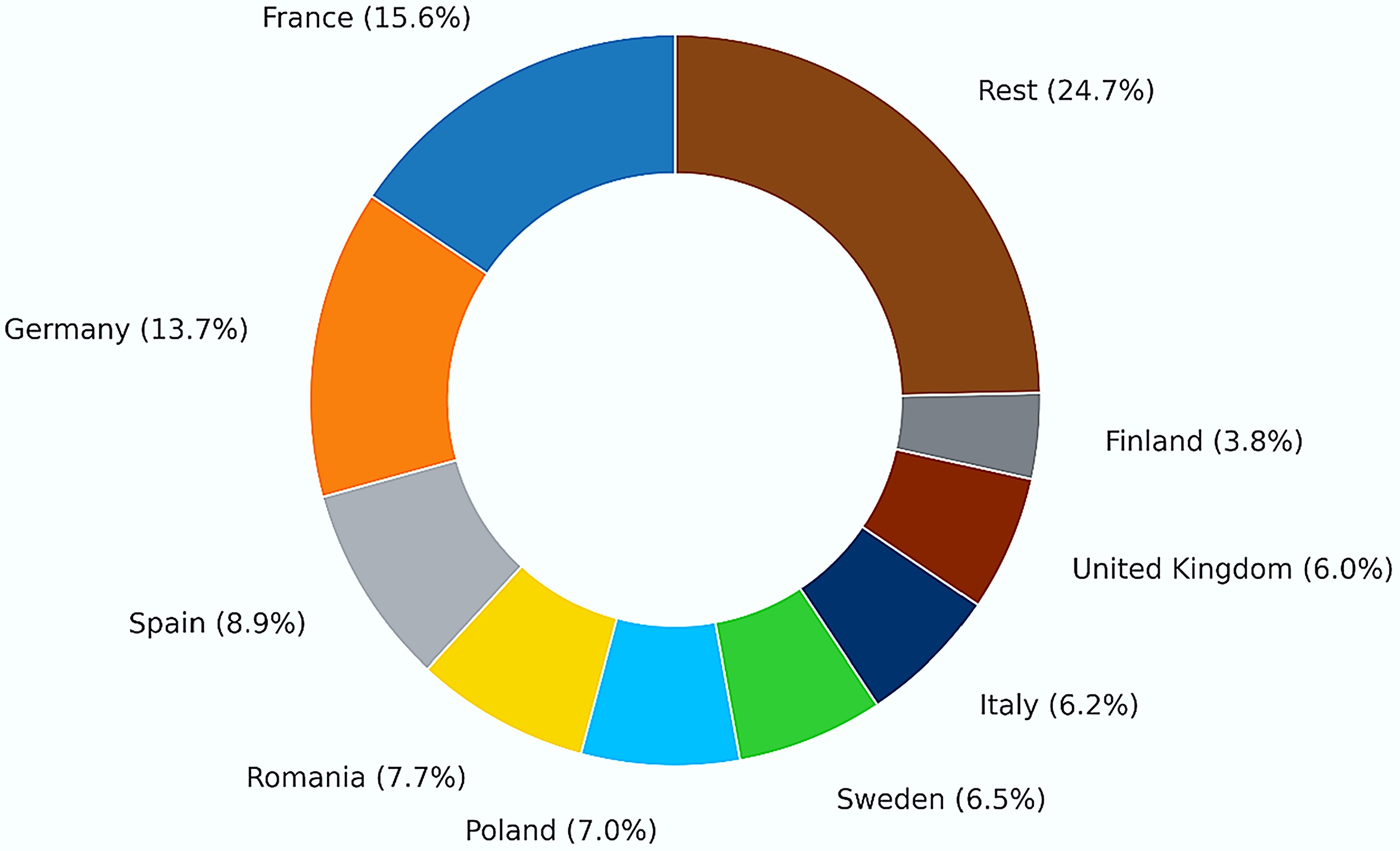

By 2050, several European countries, including Germany, France, Spain, Poland, and Italy, are expected to contribute more than 50% of the total biomethane production capacity, as depicted in Fig. 9. The production potential in these countries is largely influenced by the availability of biomass resources, with larger land areas typically supporting higher methane yields[145].

Figure 9.

Bio-based methane production in different countries. Redraw based on the data from Sulewski et al.[146].

A variety of feedstocks, including food waste, microalgae, agricultural residues, MSW, forestry by-products, animal manure, and energy crops, can be utilized for biogas production, further expanding the role of methane in the renewable energy landscape.

Techno-economic analysis of bio-methane

-

The thermochemical conversion of biomass into methane involves utilizing heat and chemical reactions to break down biomass and produce methane-rich gases. This process typically consists of three primary stages: drying, pyrolysis, and gasification. The resulting syngas undergoes cleaning and upgrading to maximize methane content. Evaluating the economic feasibility of this conversion requires analyzing factors such as total manufacturing costs, capital expenditures, and projected revenue. TEA frameworks incorporate key financial indicators, including return on investment (ROI), discounted payback period, net present value, and internal rate of return (IRR), to assess the profitability and risks associated with biomethane production[146]. Biomass methanation technologies are approaching higher TRLs (6–7), as outlined in the TEA of bio-based syngas, which supports their near-term potential but still demands targeted improvements in catalyst stability and system integration.

Several studies have investigated the biochemical conversion of biomass into biomethane, providing insights into process efficiencies and cost implications[147,148]. The techno-economic comparison of syngas, bio-based H2, and bio-based methane production from biomass is given in Table 9. Syngas production, typically achieved through fluidized bed gasification, offers operational flexibility but is less efficient (32%–53%) compared to bio-H2 (69% lower heating value (LHV) efficiency) and biomethane (70.98% system efficiency)[149]. In contrast, biomethane production via methanation achieves high carbon recovery (69.8%) but is hindered by the expense of catalysts[149].

Table 9. Techno-economic comparison of syngas, bio-based H2, and bio-based methane production from biomass

Parameter Syngas Bio-based hydrogen Bio-based methane Ref. Production method Gasification (fluidized/entrained bed) Gasification + WGS reactors + pressure swing adsorption purification Gasification + methanation (Ni-based catalysts) [149] Energy efficiency 32%–53% exergy efficiency 69% LHV efficiency (steam gasification) 70.98% system efficiency (with heat integration) [149] Yield 8–14 MJ/Nm3 (LHV) 0.057–0.107 kg H2/kg biomass 0.4–0.6 kg CH4/kg biomass [149] Production cost US${\$} $0.05–0.15 /m3 US${\$} $2.90–3.54 /kg US${\$} $1.37–1.47 /L liquid fuels (via biogas reforming) [149] Key cost driver Gasifier type, O2 consumption Gas cleaning, WGS reactors, electrolysis Methanation catalysts, drying energy [149] Carbon recovery N/A 41%–69% (with CCS) 69.8% (via gasification + methanation) [149] Byproduct Biochar, residual ash CO2 Biochar, CO2 (with CCS) [149] TRL TRL 7–8 (commercial gasifiers) TRL 6–7 (pilot plants) TRL 6 (demonstration-scale) [149] Key economic considerations include initial capital investment in infrastructure and equipment, operational costs such as feedstock procurement, labor, and maintenance, as well as revenue generation from methane sales. The choice of feedstock significantly influences process economics, with woody biomass, agricultural residues, and dedicated energy crops being the primary materials used in gasification-based methane production[39]. Catalyst deactivation and rare-metal cost considerations previously discussed in the syngas TEA section are also highly relevant here, particularly for methanation processes.

The chemical composition and energy content of different biomass feedstocks, as presented in Table 1, play a crucial role in determining product yield and overall economic feasibility. Hernández et al.[150] conducted a comparative analysis of biomethane production costs from various organic waste sources, including food waste, cattle manure, pig manure, and sewage sludge. Their findings indicated that food waste offered the most cost-effective pathway for biomethane production[150].