-

All organisms rely on the energy derived from electron flow to sustain their metabolic activities[1]. In most microbes, this process occurs intracellularly via an electron transport chain located on the cell membrane, where electrons from nutrients are transferred through a series of redox enzymes and proteins to a final electron acceptor (such as oxygen), generating a proton motive force that drives the synthesis of ATP, the universal energy currency of the cell[2]. However, some microorganisms have evolved a remarkable adaptation known as extracellular electron transfer (EET), through which they can transfer electrons across their cellular boundaries to, or from, external solid materials[3]. This bidirectional EET capability enables them to utilize insoluble substances, such as minerals or electrodes, as terminal electron acceptors or donors in environments where soluble counterparts are scarce[4,5]. This bidirectional process enables microbial survival in environments where soluble electron donors or acceptors are scarce[6]. Furthermore, it drives critical biogeochemical cycles, such as the transformation of iron, heavy metals, and methane, thereby shaping ecosystem dynamics and the planetary redox balance[3,7]. Additionally, EET underpins innovative biotechnologies, including bioremediation, bioenergy production from waste, and microbial electrosynthesis[4].

Microbial bidirectional EET relies on a series of specialized molecular mechanisms, including heme c-type cytochromes, conductive pili (nanowires), and redox mediators[4,8]. These components couple intracellular metabolic electron flow with environmental redox gradients, thereby enabling reversible electron exchange[9,10]. Current understanding of bidirectional EET mechanisms primarily derives from studies of two representative electroactive bacteria: Shewanella oneidensis and Geobacter sulfurreducens[2,8]. In S. oneidensis, outward electron transfer to Fe(III) oxides is mediated by the metal-reducing (Mtr) pathway, which comprises periplasmic decaheme cytochromes (e.g., MtrA) and outer membrane porin-cytochrome complexes[4]. Inward EET is mediated through the reverse Mtr pathway[11]. In contrast, G. sulfurreducens facilitates bidirectional electron flow through conductive pili and extracellular matrix-associated cytochromes (such as OmcS). It employs distinct energy conservation strategies to mediate electron export and import[8,9].

Existing evidence indicates that the bidirectional EET process is inherently asymmetric. Specifically, outward electron transfer generally depends on the proton motive force to conserve energy, while inward electron flow may rely more heavily on substrate-level phosphorylation for energy conservation[6,12]. The directional asymmetry of these electron flows highlights the complex regulation of microbial electron transfer coupled with energy conservation. Therefore, further exploration of their potential energy metabolism pathways and regulatory mechanisms is needed. Sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) Fundidesulfovibrio spp are key anaerobic microorganisms in the sulfur cycle and metal-rich environments[7,13]. Extensive studies have shown that SRB play central roles in sulfate-driven biocorrosion and heavy metal bioremediation[7,14]. Recently, Xu et al. demonstrated that SRB can directly utilize an electrode as an electron donor for sulfate reduction[15,16], suggesting the possibility of an EET pathway in Fundidesulfovibrio. Despite advances in bioelectrochemistry, it remains unclear whether typical electroactive microorganisms, such as SRB, possess specialized molecular systems for bidirectional EET, and how these systems interface with biosynthetic metabolism.

In this study, the bidirectional EET mechanisms and carbon metabolism potential of a novel SRB, Fundidesulfovibrio terrae SG127 isolated from paddy soil were investigated. By integrating electrochemical measurements with genomic analyses, the bidirectional EET network and its key components involved in EET were systematically deciphered. An autotrophic cultivation system was established using an electrode as the sole electron donor, and carbon dioxide as the sole carbon source, allowing for the assessment of the carbon fixation potential of this strain. Furthermore, the classical research strategy primarily regards EET as a downstream electron sink for organic matter oxidation, as exemplified by Shewanella and Geobacter[4,17]. In contrast, the present results show that in F. terrae, the bidirectional EET network operates as an upstream, primary energy-harvesting system that directly channels exogenous electrons into central carbon metabolism. These findings provide a mechanistic understanding of the metabolic versatility of F. terrae, and highlight its potential application in microbial electrochemical technologies for carbon fixation.

-

The strictly anaerobic sulfate-reducing bacterium F. terrae was isolated from paddy soil and maintained by serial passage in liquid culture[18]. The liquid basal medium used for culturing F. terrae contained 1.8 g NaHCO3, 0.427 g Na2CO3, 0.04 g CaCl2·2H2O, 0.1 g MgSO4·7H2O, 0.001 mM Na2SeO3, 10 mM sodium lactate, 40 mM sodium fumarate, 10 mL 100 × NB salts, 10 mL trace mineral solution, and 15 mL vitamin solution (Supplementary Table S1). The liquid medium was adjusted to pH 7. Cultures were inoculated with 10% (v/v) of exponentially growing cells and incubated at 30 ± 0.5 °C under anaerobic conditions maintained by continuous flushing with N2/CO2 (80:20, v/v).

Extracellular Fe(III) reduction tests

-

Extracellular Fe(III) reduction experiments were conducted in 120 mL serum bottles containing 50 mL of the basal medium, supplemented with 15 mM sodium lactate as the electron donor[19]. Ferrihydrite served as the electron acceptor in the experiments. A 0.4 mol/L FeCl3 solution, and a 1 mol/L NaOH solution were prepared. Under vigorous and constant stirring, the solution containing FeCl3 was adjusted to pH 7 using NaOH. The suspension was maintained for 2–6 h, after which the pH was readjusted to maintain it at pH 7. After centrifugation, the precipitate was collected and washed approximately seven times with ultrapure water to obtain ferrihydrite. All media were purged with a gas mixture of 80% N2 and 20% CO2 for 30 min, then sealed with rubber stoppers and aluminum caps. Under aseptic conditions, 5 mL of culture in the exponential growth phase was inoculated into each bottle. The inoculated bottles were incubated at 30 °C in a constant-temperature incubator for 7 d.

BES construction and experimental setup

-

A single-chamber bioelectrochemical system (BES, total volume 100 mL, liquid volume 80 mL) was constructed using a graphite plate electrode (99.99%, surface area 4 cm2) as both working and counter electrodes and a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) as the reference (Supplementary Fig. S1). The fresh water electrolyte contained 2.5 g/L NaHCO3, 0.068 g/L NaH2PO4·2H2O, 0.25 g/L NH4Cl, 0.1 g/L KCl, and 10 mL/L trace elements and vitamins[5]. The SCE was connected via a KCl salt bridge to form a three-electrode system. Reactors and electrolytes were sterilized at 121 °C for 20 min, and purged with N2/CO2 (80:20) to maintain anoxic conditions. Subsequently, they were inoculated with 10% (v/v) of F. terrae in the exponential growth phase. The anodic and cathodic reactors were established, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1). In the anodic reactor, pyruvate (30 mM) was used as the electron donor, while in the cathode reactor, 15 mM sulfate was used as the electron acceptor. Positive and negative working potentials were maintained in the anodic and cathodic reactors, respectively. Current generation was recorded every 100 s (I-T mode), and electrochemical activity was evaluated using cyclic voltammetry (−0.8 to +0.4 V, 1–20 mV/s) on a CHI 1000C workstation[20].

Electron transfer inhibitor experiment

-

Four respiratory chain inhibitors, including rotenone, antimycin A, diphenylammonium iodide and dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCCD) were used to study the mechanism of electron uptake and release in F. terrae biofilms. After the current in the BES stabilized (fluctuation < 5%), inhibitor stock solutions, rigorously deoxygenated (N2 purging for 30 min, dissolved O2 < 0.1 ppm), were injected sequentially via sterile syringes to achieve a four-step concentration gradient with 30-min intervals to ensure diffusion equilibrium. Real-time current density (I)−time (t) curves were recorded using a CHI 1000E electrochemical workstation, taking the moment of inhibitor addition as t0 and monitoring for 60 min at 10-s intervals. Solvent controls were conducted by adding equivalent volumes of DMSO (< 0.1% v/v). All experiments were performed in biological triplicate. Data were tested for normality (Shapiro-Wilk), and analyzed by one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05). Inhibitor-induced changes in current were used to assess the impact of each compound on F. terrae extracellular electron transfer, and inhibition efficiencies were calculated accordingly[21].

Characterization of bacterial cells and biofilms

-

The biofilm cell suspensions of F. terrae were analyzed using UV-visible spectroscopy (UV-vis). Cell suspensions were collected and washed with deoxygenated phosphate buffer solution (PBS), and 1 mM dithionite was anaerobically added as a reducing agent. Reduced samples were measured at 25 °C using a Shimadzu UV-2401 UV-visible spectrophotometer equipped with a thermostatted cuvette holder. Baseline-corrected absorption spectra were recorded from 350 to 650 nm, at a scan rate of 400 nm/min, and a slit width of 2 nm, using deoxygenated PBS as a reference. After bioelectrochemical experiments, graphite electrodes were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 4–5 h, washed, dehydrated with graded ethanol (50%, 75%, 100%), and gold-sputtered. Biofilm morphology was observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, KYKY 2800) at 25 kV[22].

Genome sequencing and analysis

-

The genome of F. terrae was sequenced by Illumina NovaSeq PE150 at the Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Company, Ltd (Beijing, China). DNA samples that passed electrophoresis were subjected to library preparation. Fragmentation was performed using a Covaris ultrasonic disruptor to obtain DNA fragments of approximately 350 bp. The resulting DNA fragments were then subjected to end-repair, A-tailing, sequencing adapter addition, purification, and PCR amplification to complete library preparation. An Illumina PE150 (350 bp) library was constructed. After library construction, initial quantification was performed using Qubit 2.0, and the library was diluted to 2 ng/μL. Insert size was then determined using an Agilent 2100. Once the insert size reached the expected value, precise quantification was performed using Q-PCR. Related coding genes were searched using GeneMarks software[23]. After library testing, different libraries were pooled according to effective concentrations, and target loads for Illumina HiSeq sequencing. Raw data was filtered to obtain clean data, and the genome size was estimated based on K-mer analysis. Assembly was performed using SOAPdenovo[24], SPAdes, and ABySS[25], followed by integration using CISA and gap filling optimization using GapCloser[26]. After removing fragments smaller than 500 bp, evaluation, statistics, and gene prediction were performed. The KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) database was used to predict gene functions.

Determination of products of microbial electrosynthesis

-

Products of microbial electrosynthesis were quantified using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) equipped with a WondaSilTM C18-WR column (5 µm particle size, 4.6 mm × 150 mm). The chromatographic separation was performed using a mobile phase composed of 18 mM KH2PO4, adjusted to pH 2.5 with phosphoric acid, and acetonitrile in a 92:8 (v/v) ratio. The effluent was delivered at a constant flow rate of 0.4 mL/min, and the column temperature was maintained at 35 °C throughout the analysis. Detection was carried out using a UV detector set at 200 nm, and the injection volume for each sample was 25 µL.

-

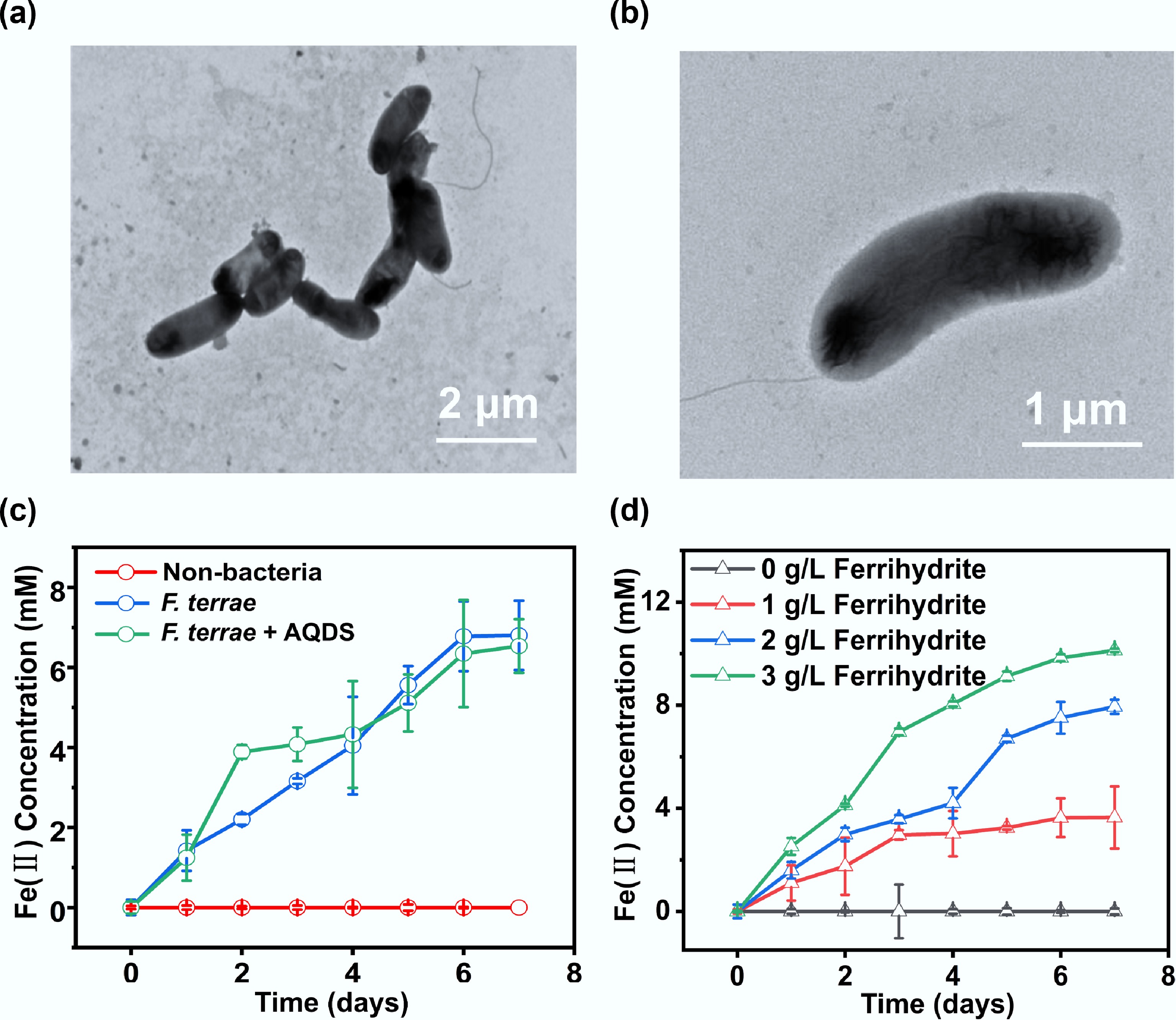

SEM images showed that F. terrae cells were 0.75–0.95 µm wide and 1.7–2.2 µm long, curved in shape, and equipped with a single polar flagellum (Fig. 1a, b). Ferrihydrite, a poorly crystalline iron(III) oxyhydroxide known for its high bioavailability and reactivity[27], was employed as the terminal electron acceptor to assess the extracellular respiratory capacity of F. terrae (Supplementary Fig. S2a). Fe(III) reduction by F. terrae exhibited distinct phase-dependent kinetics, with the rate progressively increasing during the lag phase, reaching a maximum in the exponential growth phase, and subsequently declining through the stationary and death phases (Supplementary Fig. S2b). F. terrae demonstrated efficient Fe(III) reduction, achieving a reduction efficiency of 68.3% (Supplementary Fig. S2c). Notably, the bacterium reduced Fe(III) effectively even in the absence of exogenous electron shuttles such as anthraquinone-2,6-disulfonate (AQDS) (Fig. 1c), indicating that its Fe(III) reduction capability is independent of soluble mediators. The microbial reduction of Fe(III) was governed by the availability of ferrihydrite as the terminal electron acceptor (Fig. 1d), while the total iron content in the system remained well-balanced throughout the process (Supplementary Fig. S2d). The ability of F. terrae to directly reduce solid-phase Fe(III) minerals underscores its metabolic versatility and suggests that this sulfate-reducing bacterium can utilize solid-phase Fe(III) as a respiratory electron acceptor, revealing considerable flexibility in its respiratory strategies[28]. The observation that Fe(III) reduction occurred without added AQDS or similar shuttles supports the presence of a direct, membrane-bound EET pathway in F. terrae, likely involving specialized cytochromes or conductive proteins. All experiments included rigorous sterile controls, which effectively ruled out abiotic contributions to Fe(III) reduction, such as chemical corrosion or non-biological redox reactions in the medium (Fig. 1c, d). These findings indicate that F. terrae utilizes a distinctive, membrane-associated mechanism for direct electron transfer to Fe(III) minerals, highlighting its capacity for direct mineral reduction without relying on soluble electron shuttles. This capability enhances our understanding of the role SRB may play in anaerobic iron cycling and solid-phase electron acceptor utilization.

Figure 1.

Cellular morphology and Fe(III) reduction of F. terrae. (a) Low- and (b) high-magnification transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of F. terrae cells; (c) Fe(II) production yields by F. terrae across different experimental treatment; (d) Fe(II) production as a function of ferrihydrite concentration. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. from n = 3 independent replicates.

Revealing bidirectional EET activity of F. terrae through electrochemical measurements

-

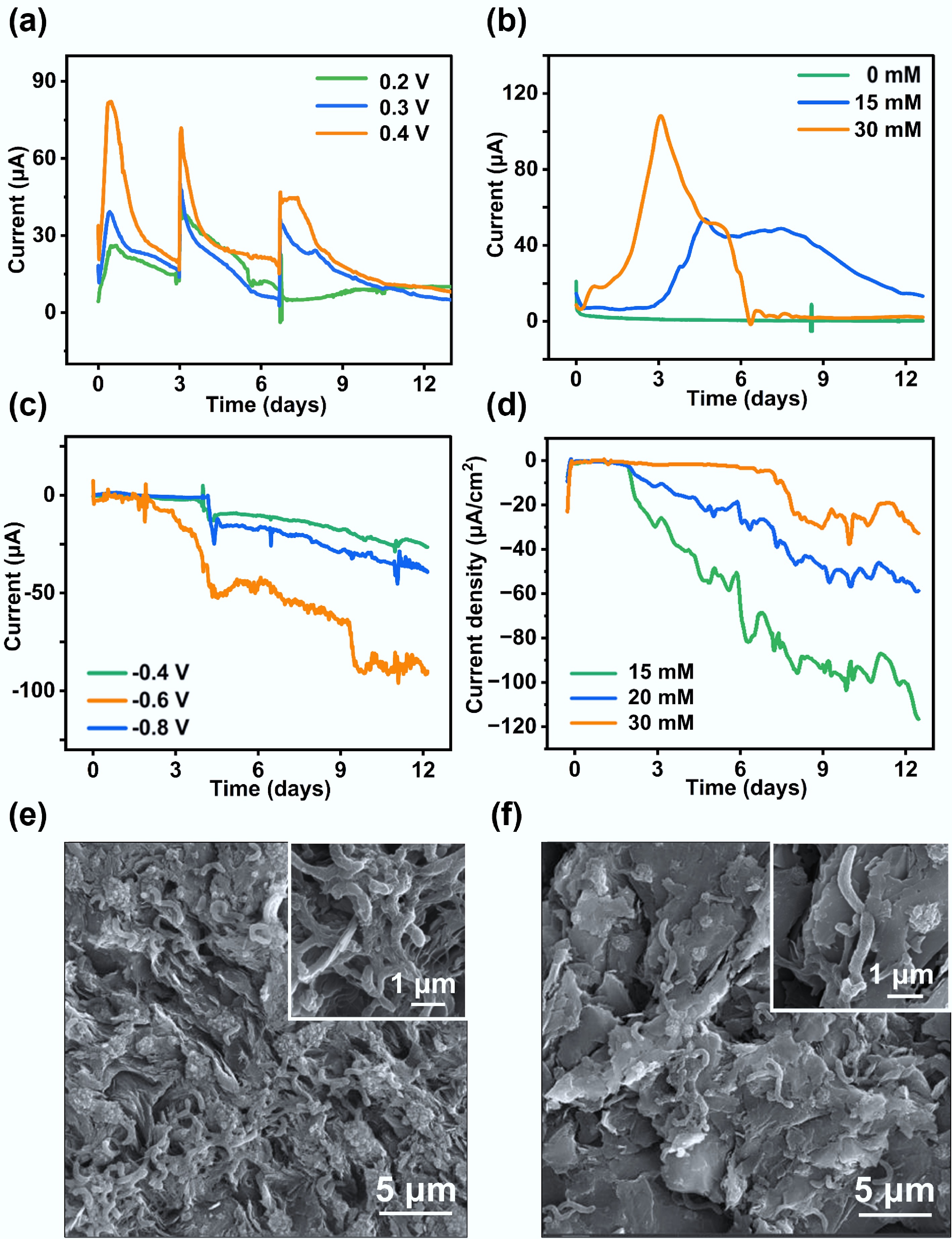

The EET activity of F. terrae was further evaluated electrochemically using an electrode that served as an electron donor and acceptor, respectively. F. terrae was inoculated in a BES operated at various electrode potentials. The gradual current decline during anodic cycling reflects substrate (pyruvate) depletion, as confirmed by its rapid and near-complete recovery upon medium replenishment. This demonstrates that the attenuation is solely due to reversible substrate limitation, thereby confirming the metabolic resilience and stable electrocatalytic function of F. terrae (Fig. 2a). The highest current output of 21.75 μA/cm2 was achieved at +0.4 V. The influence of electron donor concentrations on BES performance was further investigated (Fig. 2b). When pyruvate was supplied as the electron donor at 30 mM, the maximum anodic current reached 27.5 μA/cm2. The reproducible and stable current outputs under sterile control conditions confirm that the observed activity originates from biological EET rather than abiotic reactions. Notably, the anodic current density generated by F. terrae is comparable to that of well-studied electroactive models such as Geobacter and Shewanella[17,29], indicating its high EET performance. In the cathodic mode, where the electrode served as the electron donor, a peak current of −24 μA/cm2 was recorded at −0.6 V (Fig. 2c). Although no periodic current was generated under cathodic polarization, the steady increase in current, followed by stabilization, suggests the activation of an inward electron uptake pathway[28]. The cathodic current reached −28.75 μA/cm2 with 15 mM sulfate as the electron acceptor (Fig. 2d). These results clearly demonstrate that F. terrae can function both as an electron donor and acceptor, coupling its metabolism to solid-phase electrodes—a hallmark of bidirectional EET. SEM image revealed that dense biofilms had formed on both the anodic and cathodic electrode surfaces (Fig. 2e, f), suggesting that this strain is capable of bidirectional EET through a direct electron transfer process. Bacterial cells grew faster under electroheterotrophic conditions (using the electrode as an electron acceptor) than under electroautotrophic conditions (using it as an electron donor)[6]. This explains the higher cell density observed in the anodic biofilm.

Figure 2.

Bidirectional EET performance of F. terrae in a BES. (a) Anodic current generated by F. terrae under different applied potentials; (b) Anodic current responses under varying concentrations of the electron donor; (c) Cathodic current recorded at different applied potentials; (d) Cathodic current responses under varying concentrations of the electron acceptor; SEM images of the electroactive biofilm formed on the (e) anode and (f) cathode surfaces.

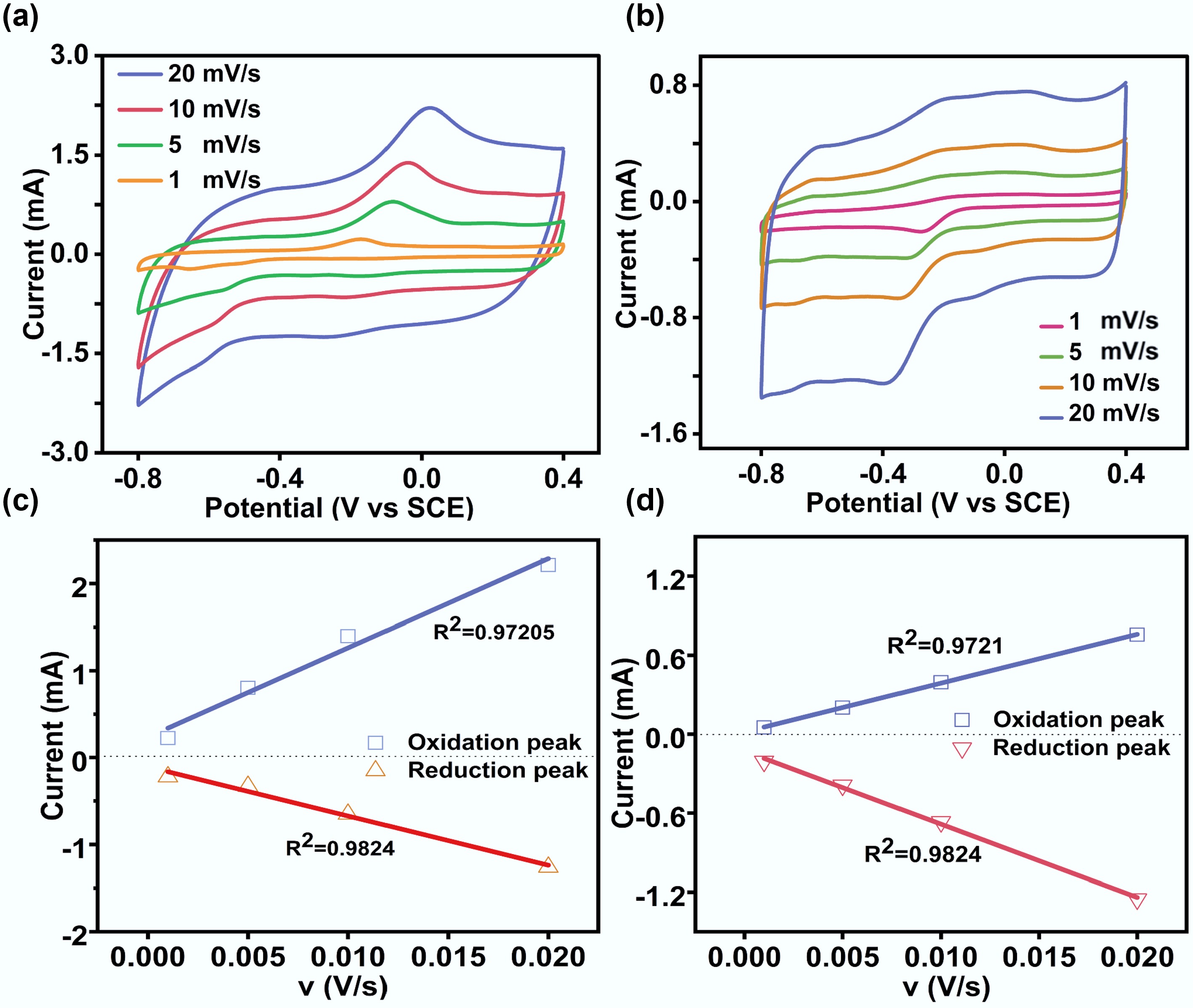

To elucidate the electron transfer mechanism, CVs of the anodic and cathodic biofilms were measured at different scan rates (Fig. 3). Both the anodic and cathodic peak currents exhibited an increase with scan rate, while the redox peak potential separation (ΔEp = Epc–Epa, where Ep is the redox peak potential) also increased, indicating quasi-reversible electron transfer behavior. Separated oxidation and reduction peaks were identified at 0.025 and −0.62 V for the anodic biofilm, respectively (Fig. 3a). Distinct oxidation and reduction peaks were identified at −0.1 and −0.4 V for the cathodic biofilm, respectively (Fig. 3b). A negative shift in the redox potential of the cathodic biofilm suggests the expression of low-potential redox proteins (such as c-type cytochromes or flavoproteins) in the cathodic cells, thereby likely facilitating electron uptake from the electrode[12]. This potential difference also suggests that anodic and cathodic EET pathways are mediated by distinct membrane-bound complexes or electron shuttle systems[4,6]. Linear regression analyses of the peak current vs scan rate yielded R2 values of 0.9720 and 0.9824 for the anodic biofilm, respectively, and 0.9721 and 0.9824 for the corresponding cathodic biofilm (Fig. 3c, d). The dependence of peak currents on the scan rates indicated typical surface-controlled electrochemical processes[5]. In summary, the EET network in F. terrae is a bidirectionally governed system, which might be dynamically controlled by an array of low-potential redox proteins and interfacial mediators. This complex regulation provides an adaptive advantage to expand the metabolic versatility of this strain in bioelectrochemical niches.

Figure 3.

Cyclic voltammetry analysis of anode and cathode biofilms at different scan rates. (a) Anode biofilm; (b) Cathode biofilm; (c) Linear relationship between peak current and the scan rate derived from non-turnover CVs of anode biofilms; (d) Linear relationship between peak current and the scan rate derived from non-turnover CVs of cathode biofilms.

Revealing the bidirectional EET process using electron transfer inhibitors

-

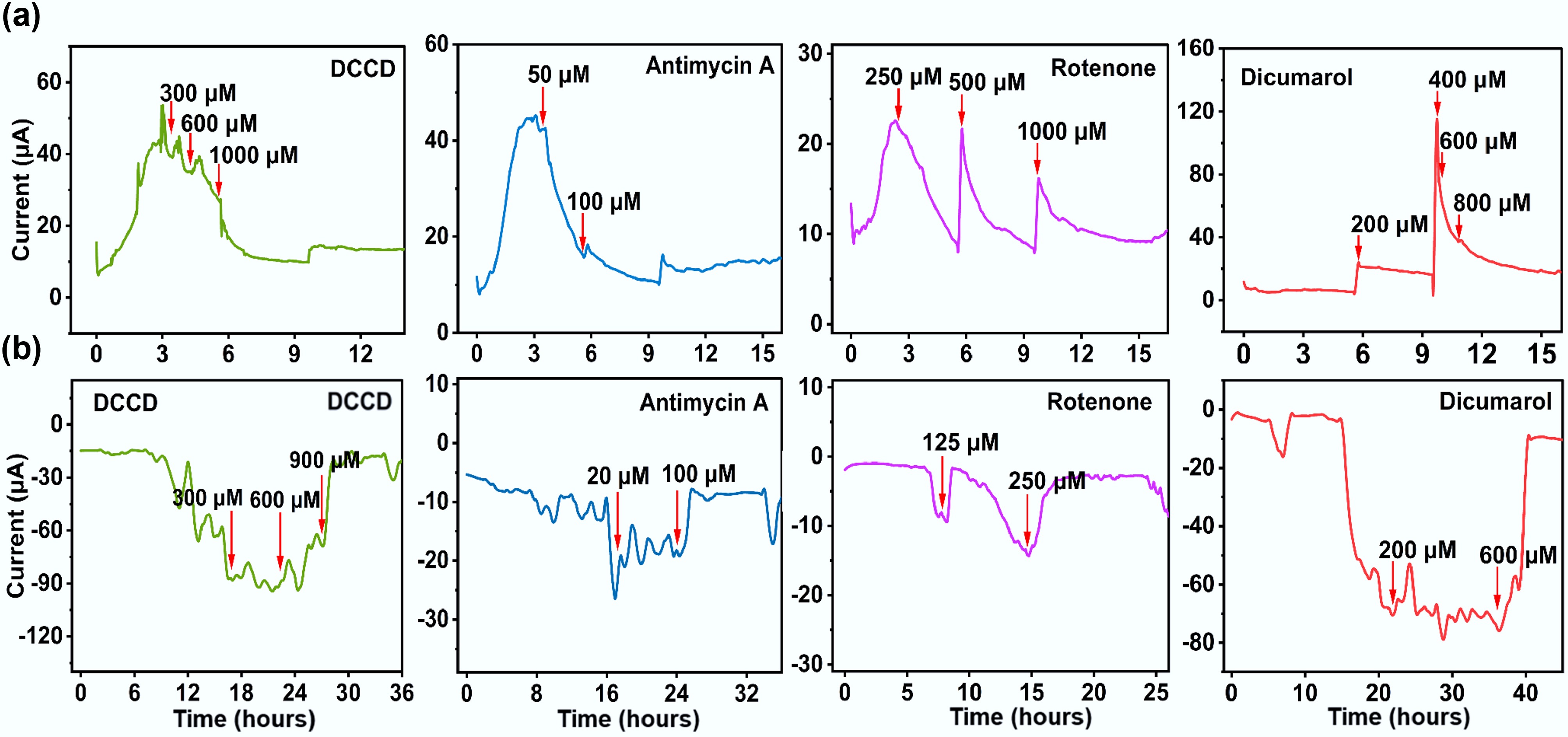

Previous studies have shown that electron transfer inhibitors can be used as important tools to analyze the mechanism of bidirectional EET in microorganisms[30]. DCCD, a specific inhibitor of the F-type ATP synthase (complex V), blocks ATP synthesis and consequently depletes intracellular ATP[31]. As shown in Fig. 4, increasing DCCD concentrations (0.3, 0.6, and 0.9 mM) progressively suppressed both inward and outward EET, with maximal inhibition rates exceeding 80% in both directions. These results demonstrate that ATP generation is essential for sustaining the bidirectional EET activity of F. terrae[32]. Antimycin A can specifically bind to the Qi site of the cytochrome bc1 complex, blocking the transfer of electrons from complex I (NADH dehydrogenase) to cytochrome c[33,34]. Antimycin A exhibited a dose-dependent inhibitory effect on EET in F. terrae. At a concentration of 0.05 mM, it caused significant suppression of outward EET (Fig. 4a), while for inward EET, 0.1 mM exhibited a pronounced inhibitory effect, with an inhibition rate exceeding 80% (Fig. 4b), suggesting that the outward electron transfer pathway depends more critically on complex III (cytochrome c oxidoreductase). The compound substantially impaired the bidirectional electron flow capacity of F. terrae by specifically inhibiting electron transfer between cytochrome b_H and coenzyme Q within complex III[35]. This blockage is consistent with the known mechanism of antimycin A as an allosteric inhibitor of the bc1 complex, which binds to the quinone-binding site and disrupts the Q-cycle mechanism essential for electron propulsion. Based on the present experimental observations, a putative electron transfer pathway in F. terrae can be proposed. In this model, electrons originating from pyruvate oxidation are initially delivered to the quinone pool. They are then transferred to complex III (cytochrome bc1 complex), ultimately being channeled across the membrane via cytochrome-mediated pathways for EET. The differential sensitivity of inward versus outward EET to antimycin A underscores the functional specialization of electron transport components in bidirectional extracellular respiration.

Figure 4.

Effects of electron transport inhibitors on bidirectional EET. (a) Outward EET; (b) Inward EET.

Rotenone exhibited a concentration-dependent inhibitory effect on outward EET in F. terrae. At low concentrations, it caused only mild and recoverable suppression of outward current (Fig. 4a), whereas a high dose (1.0 mM) led to nearly complete inhibition. In contrast, inward EET was strongly inhibited even at low rotenone concentrations (0.25 mM) (Fig. 4b), suggesting greater sensitivity of the inward electron uptake pathway to complex I disruption. These results indicate that the NADH-quinone segment of complex I participates in both outward and inward EET[4]. Similarly, dicoumarol—an inhibitor of the quinone pool—effectively impeded electron flow from metabolic complexes to quinones. At 0.6 mM, it had no significant effect on outward electron transfer, whereas inward electron transfer was nearly completely inhibited, with an inhibition rate exceeding 90% (Fig. 4). This supports the model that electrons destined for export must first pass through complex II to the quinone pool, whereas inward electron uptake can proceed via alternative, quinone-independent routes, such as membrane-associated oxidoreductases[1]. To further identify electron carriers involved in these processes, UV-visible spectroscopy was performed on cell suspensions of F. terrae (Supplementary Fig. S3). Characteristic absorption peaks were observed at 409 nm for oxidized c-type cytochromes (c-Cyts), and at 419 nm (Soret band) and 522 nm (β band) for reduced c-Cyts[4,36]. The observed spectral features suggest that these c-type cytochromes may be involved in EET[37].

Genomic dissection of the EET mechanism in F. terrae

-

Electron transfer inhibition experiments can only reveal part of the EET process at the plasma membrane level. To systematically elucidate the bidirectional EET mechanism of F. terrae, this study performed functional annotation of its genome using InterProScan and Gene Ontology (GO). GO categorizes gene functions into three classes: biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions, reflecting the physiological processes, subcellular localization, and molecular activity of gene products, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S4). The biological process genes of F. terrae encompass functions such as metabolism, signal transduction, motility, and cell proliferation, indicating its complex energy metabolism and environmental responsiveness. Cellular component genes are mainly located in the cell membrane and extracellular structures, suggesting their involvement in electron transport at the intracellular and extracellular interfaces. Molecular function genes are rich in heme-binding proteins, oxidoreductases, and transport proteins, providing molecular support for electron transport processes (Supplementary Fig. S4b). Generally, bacterial EET pathways do not follow the traditional respiratory chain. They rely on hydrogenase (with cytochrome c as a cofactor) to transfer electrons generated by intracellular oxidative electron donors (such as NADH) to cytochrome c through the periplasm[6]. Electrons are then transferred via cytochrome c to extracellular acceptors.

Multi-heme c-type cytochromes are usually located in biological membranes or on the cell surface and contain multiple heme cofactors, which can achieve efficient electron transfer[38]. F. terrae harbors multiple genes encoding components of cytochrome c, including the inner membrane protein MacA, the periplasmic protein MtrD, and the outer membrane protein MtrC (Supplementary Table S2). We speculate that these proteins are not independent units, but together construct a continuous electron transport chain extending from the intracellular quinone pool to the extracellular acceptor, promoting the bidirectional EET of F. terrae. Specifically, MacA is located on the inner membrane and has two globular domains containing heme, which helps to bind tightly to the negatively charged plasma membrane and transfer inner membrane electrons to the periplasmic space[39]. In the periplasmic region, as a homolog of MtrA, MtrD can transfer electrons from the quinone pool to the extracellular acceptor. In some cases, MtrD is capable of partially compensating for MtrA in mediating periplasmic electron transfer[40]. The outer membrane MtrC contains 10 heme groups, which can efficiently export electrons to extracellular receptors after receiving electrons from the periplasm[41,42].

In the model strain Shewanella, the outer membrane cytochrome MtrC has been unequivocally demonstrated to accept electrons from extracellular electron donors (e.g., metal oxides) and mediate inward electron transfer via the Mtr pathway[43]. Given the presence of mtrC homologous genes in the F. terrae genome, we hypothesize that this strain may employ a similar mechanism for electron uptake. Electrons are first received by outer membrane MtrC, transferred via the periplasmic cytochrome pool, then through the inner membrane redox complex MacA into the quinone pool, and finally into complex III. Antimycin A inhibition of complex III demonstrates that electrons must pass through the quinone pool and complex III. MacA likely mediates electron transfer from the periplasm to complex III, serving as a key inward electron conduit. Electrons can then drive reverse electron flow through the respiratory chain, ultimately reducing NAD+ to NADH. The generated NADH and proton motive force (PMF) may support metabolism, with PMF potentially driving ATP synthesis[6,44]. This process supplies both reducing equivalents and energy for autotrophic carbon fixation. In addition, the F. terrae genome encodes several type IV pili (T4P)-related genes, such as pilA, pilB, pilC, pilD, and pilQ (Supplementary Table S2). These pili not only support biomembrane structures but may also serve as electron conduction channels[45], unlike the Geobacter genus, which relies on thick biomembranes for long-range electron conduction[6,46]. In F. terrae, pili may resemble nanowires, acting as 'external cables' to mediate electron transport, working in conjunction with outer membrane polyhemoglobin cytochromes, and periplasmic electron carriers to form short-range, high-conductivity extracellular electron transport pathways, thereby minimizing energy loss and electrical resistance[9,29]. F. terrae may represent a new EET paradigm that combines a Shewanella-like transmembrane cytochrome module with Geobacter-like pilus nanowires, forming a distinctive cytochrome–nanowire system. This architecture allows flexible use of diverse extracellular electron donors and acceptors, providing metabolic and ecological advantages in complex anaerobic environments.

Electrosynthesis-driven carbon fixation by F. terrae

-

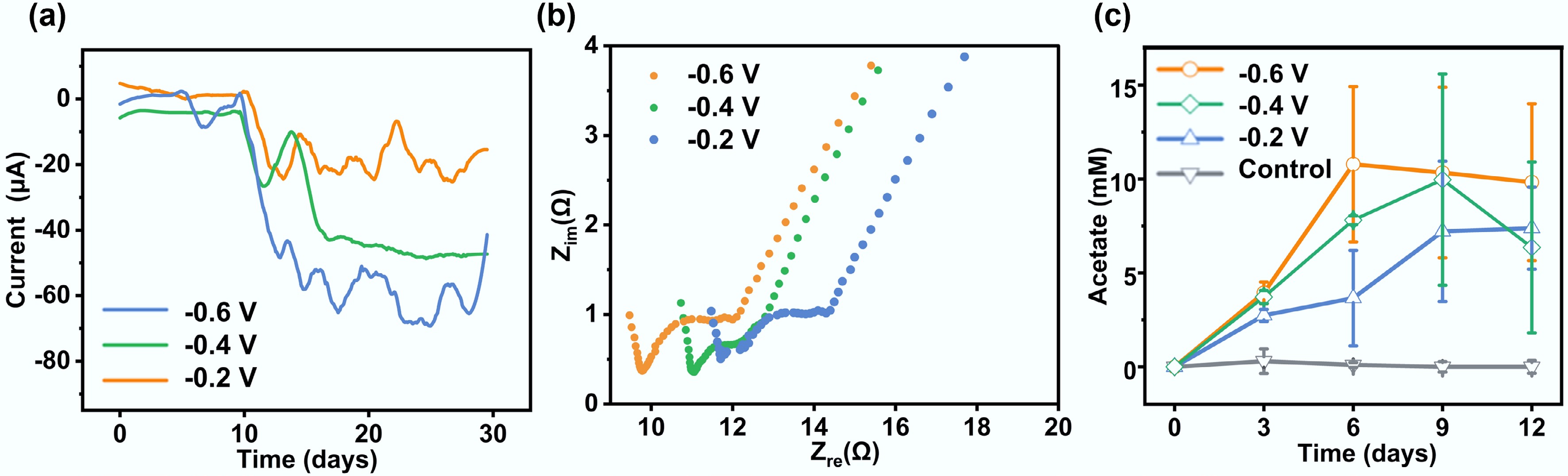

Microbial electrosynthesis powered by electrical energy represents a promising green strategy for producing value-added chemicals from CO2[47,48]. While Sporomusa ovata and Moorella thermoacetica have been established as model organisms for CO2 reduction via electron uptake in microbial electrosynthesis[49,50], the use of SRB for the conversion of CO2 into valuable products remains relatively underexplored[51]. In the microbial electrochemical system, a sustained cathodic current was observed when an external potential was applied to the electrode in the presence of F. terrae under sulfate-free conditions, with CO2 serving as the sole electron acceptor (Fig. 5a). The magnitude of this current exhibited a clear dependence on the applied potential, reaching a maximum at −0.6 V vs SCE. Notably, the current densities under these CO2-reducing conditions were consistently lower than those measured when sulfate was present as the electron acceptor, suggesting that sulfate is a thermodynamically and kinetically more favorable terminal electron acceptor for F. terrae than CO2. Consistent with the observed current peak, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy revealed that the charge transfer resistance was minimized at −0.6 V (Fig. 5b), indicating the establishment of a highly efficient electron transfer pathway under this potentiostatic condition.

Figure 5.

Microbial electrosynthesis performance of F. terrae. (a) Cathodic current densities recorded at different electrode potentials; (b) Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (Nyquist plots) of F. terrae-colonized electrodes under varying potentials; (c) Acetic acid yields correlated with applied potentials, reflecting bioelectrocatalytic efficiency.

Acetate was determined to be the dominant product of carbon fixation in this microbial electrosynthesis system. The yield of acetate was found to be potential-dependent, culminating at an applied potential of −0.6 V (Fig. 5c). This optimum potential corresponded to the peak in cathodic current, demonstrating a direct coupling between the electrochemical driving force and microbial CO2 reduction activity. Acetate production reached a concentration of 11.05 mM (Fig. 5c), validating the high efficiency of the electron transfer process. The generation of acetate showed a kinetic process with three stages, including hysteresis, exponential, and decay. The initial hysteresis stage was the adaptation period, followed by the exponential stage (days 3–9), during which acetate accumulated at an average rate of 1.84 mM/d. After the ninth day, the concentration began to decline, with a daily decay rate of approximately 0.23–0.57 mM/d. The system state changed from net product generation to synthesis inhibition or product consumption. This may result from localized acidification, transiently inhibiting acetyl-CoA synthetase activity, thereby limiting acetate utilization; through the reverse β-oxidation pathway, acetate can be reintegrated into the metabolic cycle, serving as an intermediate carbon source[52,53]. Geobacter also had a similar feedback effect under high current conditions[54].

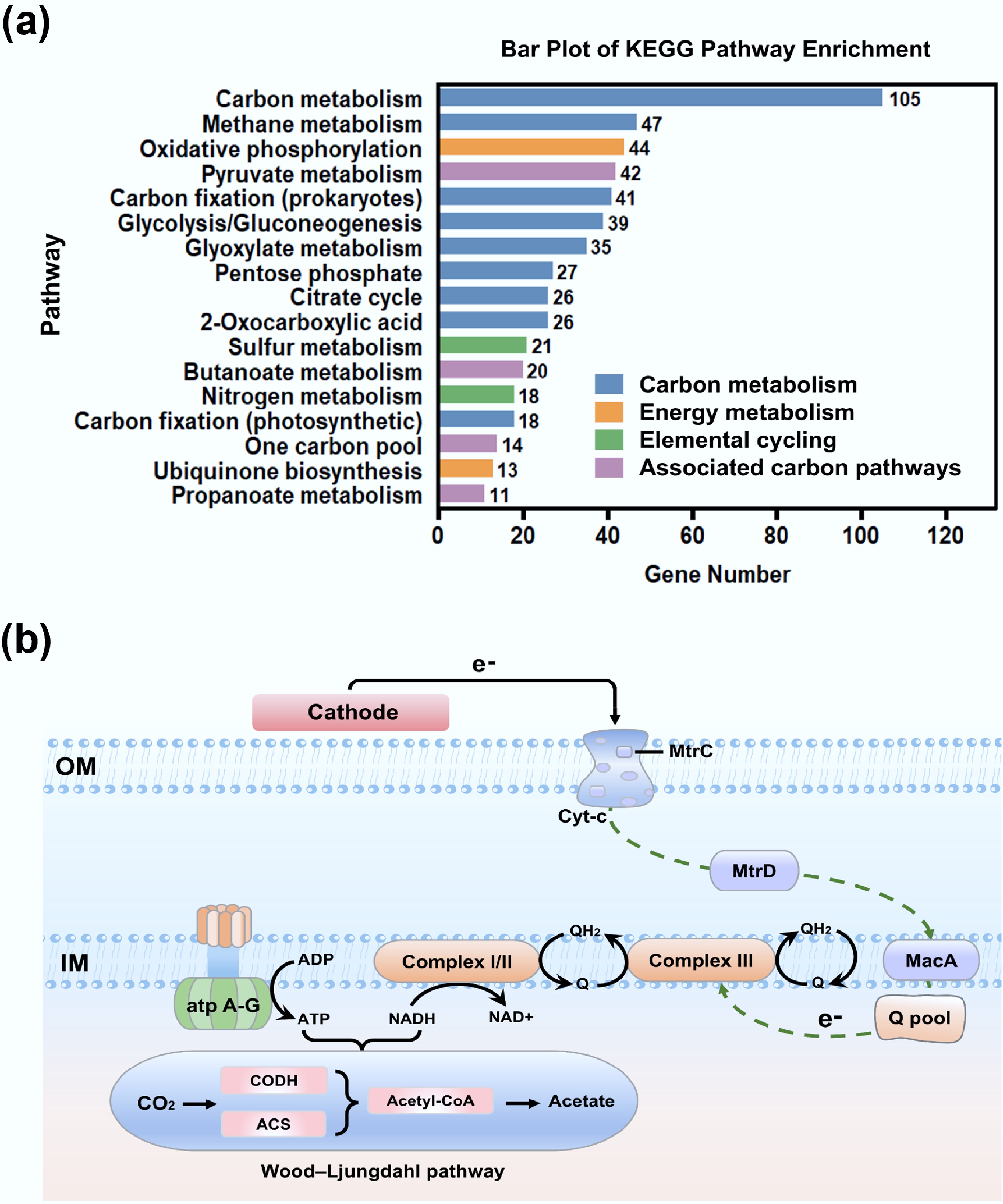

KEGG and genomic annotations show that F. terra contains up to 1,372 metabolic genes, and is enriched in several core pathways related to carbon fixation and conversion (Supplementary Fig. S5). These processes involve glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, the tricarboxylic acid cycle, glyoxylate metabolism, folate-mediated single-carbon pools, and prokaryotic carbon fixation pathways (Fig. 6a). These pathways collectively underpin a reductive carbon flux system, likely centered on the Wood-Ljungdahl (WL) pathway. Exogenous electrons from the cathode enter the cell via direct electron transport (DET), or indirect electron transport (MET). Electrons are initially transferred via cobalt-dependent enzymes to reduce CO2 to a formyl intermediate, which is then converted into a methyl group[55]. Subsequently, they bind to the carbonyl unit in the acetyl-CoA synthase complex (CODH/ACS complex) to generate acetyl-CoA[56]. Acetyl-CoA can be further converted to acetic acid, thus achieving the fixation of inorganic carbon into organic carbon. During this process, the electron flow drives the NADH/NAD+ cycle, and the quinone pool cycle, and proton transmembrane transport, maintaining the intracellular reducing environment and generating ATP through phosphorylation, providing energy for CO2 reduction. Therefore, it is speculated that CO2 fixation in this system is carried out via the WL pathway, a process that is highly dependent on electron input and energy coupling. The cross-coupling of sulfur and nitrogen metabolism further complements the electron flow and proton kinetic potential, enhancing the reducing conditions[57]. In this microbial electrosynthesis process, the electrons from the electrode could possibly be uptaken by the F. terrae cells via outer membrane polyhemoglobin cytochromes (e.g., MtrC) and coupled fimbriae or membrane protein pathways (i.e., transmembrane electron transport channels)[15,58]. The electrons then drove intracellular reduction reactions, thereby activating the WL pathway to fix CO2 into acetyl-CoA, and further generating acetic acid through substrate-level phosphorylation of acetyl-CoA, ultimately achieving the synthesis of autotrophic products (Fig. 6b).

Figure 6.

Microbial electrochemical carbon fixation pathways of F. terrae. (a) Functional distribution of genes associated with carbon metabolism and related processes: carbon metabolism (glycolysis, TCA cycle, carbon fixation) in blue; energy metabolism in orange; elemental cycling (N, S) in green; other carbon-related pathways in purple; (b) Schematic representation of the carbon fixation pathway in F. terrae.

-

This study provides experimental evidence that the sulfate-reducing bacterium F. terrae strain possesses bidirectional EET capability, enabling it to function both as an electron donor and acceptor in solid-phase redox reactions. Phenotypic characterization confirmed its ability to reduce extracellular Fe(III) oxides and electrodes, while bioelectrochemical analyses demonstrated electron uptake from cathodic surfaces, substantiating the bidirectional nature of its EET metabolism. Electrochemical and spectroscopic data further indicated that direct EET mechanisms, likely mediated by c-type cytochromes, contribute to electron transduction across the cell membrane. Inhibitor experiments revealed that inward EET primarily relies on a rotenone-sensitive route via complex III, whereas outward EET requires electron injection into the quinone pool via complex II before cytochrome-mediated extrusion. Genomic analysis supported these findings by identifying key genes encoding redox-active complexes and cytochrome c proteins essential for EET. Leveraging its inward EET capacity, F. terrae was successfully applied in a bioelectrosynthesis system, where it facilitated the conversion of CO2 to acetate via the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway, demonstrating its potential for microbial electrosynthesis. These findings reveal unique bidirectional EET pathways in F. terrae and demonstrate their potential for microbial electrosynthesis, laying a foundation for SRB-based technologies that convert CO2 into valuable products and support sustainable energy solutions.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/een-0025-0021.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Yong Yuan: conceptualization, review, editing, and design. Jiaojiao Wang: writing − original draft, data collection, and analysis. Jiaqi Huang: material preparation, data collection, and analysis. Yue Lai: data collection, and analysis. Mohamed Mahmoud: review and editing. Rong Tang: Review and editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable requests.

-

This study was supported by the Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (Grant No. 2023B1515040022), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. U24A20624).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

F. terrae performs direct iron reduction without soluble mediators.

F. terrae exhibits the capacity to perform bidirectional extracellular electron transfer.

Carbon fixation is achieved via CO2-to-acetate reduction by F. terrae.

CO2 reduction proceeds via the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Jiaojiao Wang, Jiaqi Huang

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - The supplementary files can be downloaded from here.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wang J, Huang J, Tang R, Lai Y, Mahmoud M, et al. 2026. Bidirectional extracellular electron transfer and electroautotrophic metabolism in Fundidesulfovibrio terrae. Energy & Environment Nexus 2: e006 doi: 10.48130/een-0025-0021

Bidirectional extracellular electron transfer and electroautotrophic metabolism in Fundidesulfovibrio terrae

- Received: 19 November 2025

- Revised: 10 December 2025

- Accepted: 31 December 2025

- Published online: 30 January 2026

Abstract: Extracellular electron transfer (EET) is a pivotal process in biogeochemical and bioelectrochemical systems, where its bidirectional form governs microbial energy exchange in complex environments. Sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) exhibit notable metabolic flexibility via bidirectional EET, yet this trait has been verified in only a few species. Herein, we report the bidirectional EET capability and electroautotrophic carbon fixation potential of a newly isolated SRB, Fundidesulfovibrio terrae SG127. This strain exhibited remarkable extracellular Fe(III) reduction activity, with a maximum reduction ratio of 68.3% in 7 d. Electrochemical measurements confirmed that the strain is capable of bidirectional EET, as evidenced by the generation of a maximum anodic and cathodic current density of 27.50 and 28.75 μA/cm2 through donating electrons to and accepting them from the electrode, respectively. A combination of UV-vis spectroscopy, inhibition studies, and genomic analyses confirmed the key role for c-type cytochromes in mediating bidirectional EET in F. terrae. Under autotrophic conditions, F. terrae efficiently converts CO2 into acetate as the main product by utilizing electrons from the electrode via a controlled potential in a microbial electrosynthesis system, attaining an acetate concentration of up to 11.05 mM. These findings provide a novel microbial resource and theoretical foundation for understanding the role of microorganisms in the carbon cycle, and for developing microbial electrochemical strategies to achieve carbon neutrality.