-

Box columns are frequently used as components of special moment-resisting frames (SMRF) in regions with a high seismic risk. These sections are typically fabricated from four welded plates. Their large bending capacity about any axis makes these sections more efficient than wide flange sections in flexural and compression members such as beam columns[1]. Additionally, the closed shape of box columns provides high torsional stiffness, which decreases the need for lateral bracing and mitigates the strength reduction typically caused by column rotation[2]. The high ductility, energy dissipation, and post-buckling strength of box sections further enhance their suitability for use as columns of seismic moment-resisting frames. Box columns also optimize material utilization and minimize the costs associated with painting and surface maintenance through their efficient design[3]. Goswami and Murty[4] introduced an improved I-beam configuration of a box column connection to overcome the drawbacks of the flow path of discontinuous forces observed in seismic steel moment frames. Their results indicated that the mobilization of the nominal beam's plastic moment capacity with sufficient strain hardening of the beam flanges could be achieved in I-beam–box column connections. Although their concept addressed the major problem of the flow path of discontinuity forces, it was not practical or economically viable. Similarly, Ghobadi et al.[5] demonstrated the promising performance of box column connections with side stiffeners, though their practical fabrication remained a challenge. Full-scale experimental tests and finite element (FE) analyses reported in[6,7] showed that connections with adequate stiffeners, designed according to fundamental seismic principles, provided sufficient strength, stiffness, and rotational capacity. Additional research by Choi et al.[8] and Yang[9] has further advanced the understanding of box columns and their connections.

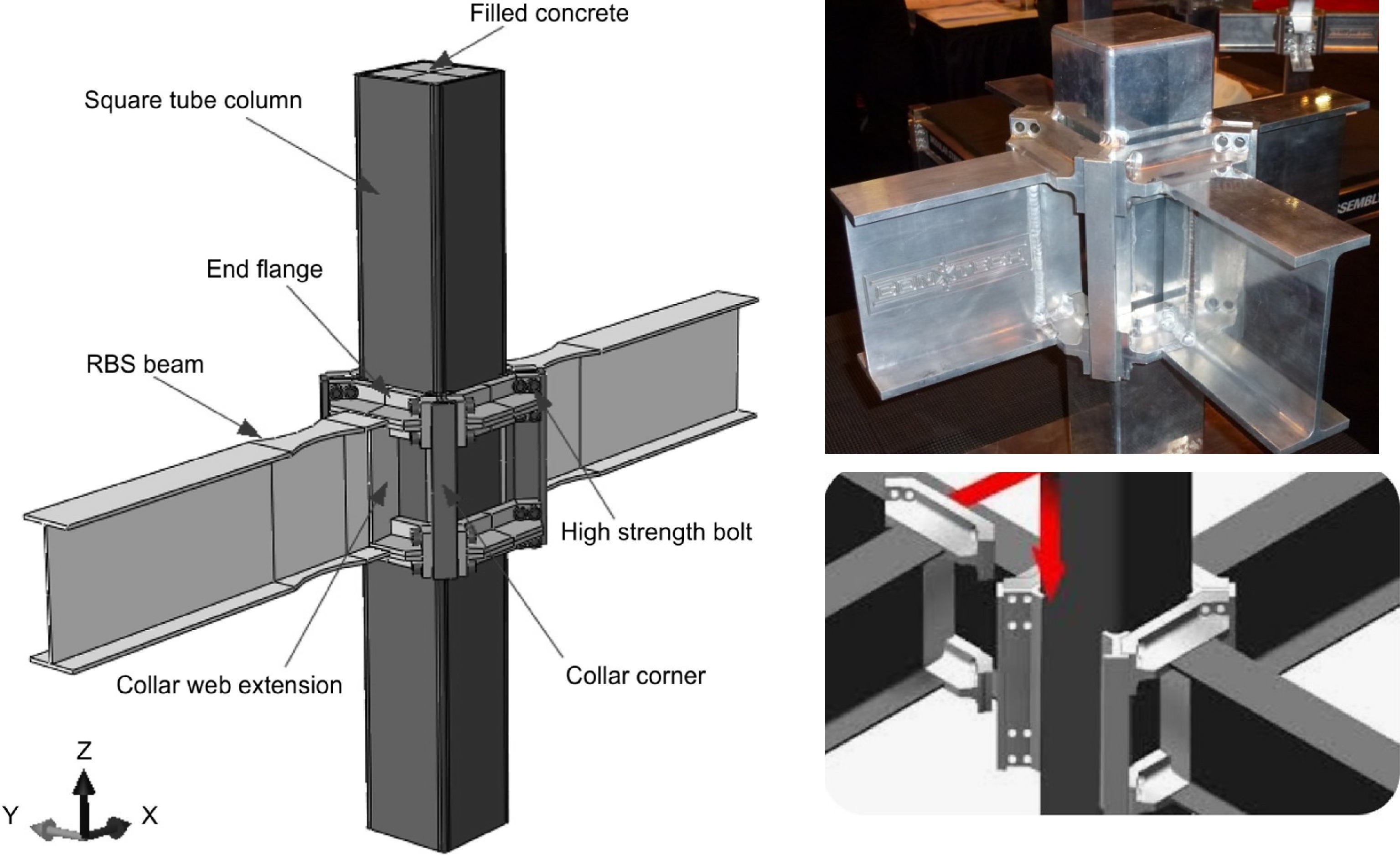

Despite the abovementioned advantages, box columns present certain challenges compared with other cross-sections. For instance, accessing the interior of box columns for welding and connecting the continuity plates is challenging, complicating welding inspections and increasing production costs. Furthermore, the presence of two parallel webs in box columns results in different behaviors in comparison with other wide-flange columns. These challenges have led to extensive research into box column connections, aiming to develop cost-effective solutions while ensuring appropriate seismic performance. One notable outcome of those efforts was the introduction of the ConXL connection in the ANSI/AISC 358-10 standard[10] as a prequalified moment connection. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the ConXL connection.

Figure 1.

Details of the ConXL connection with concrete infill, based on AISC 358-10[10]. Figure constructed by the authors.

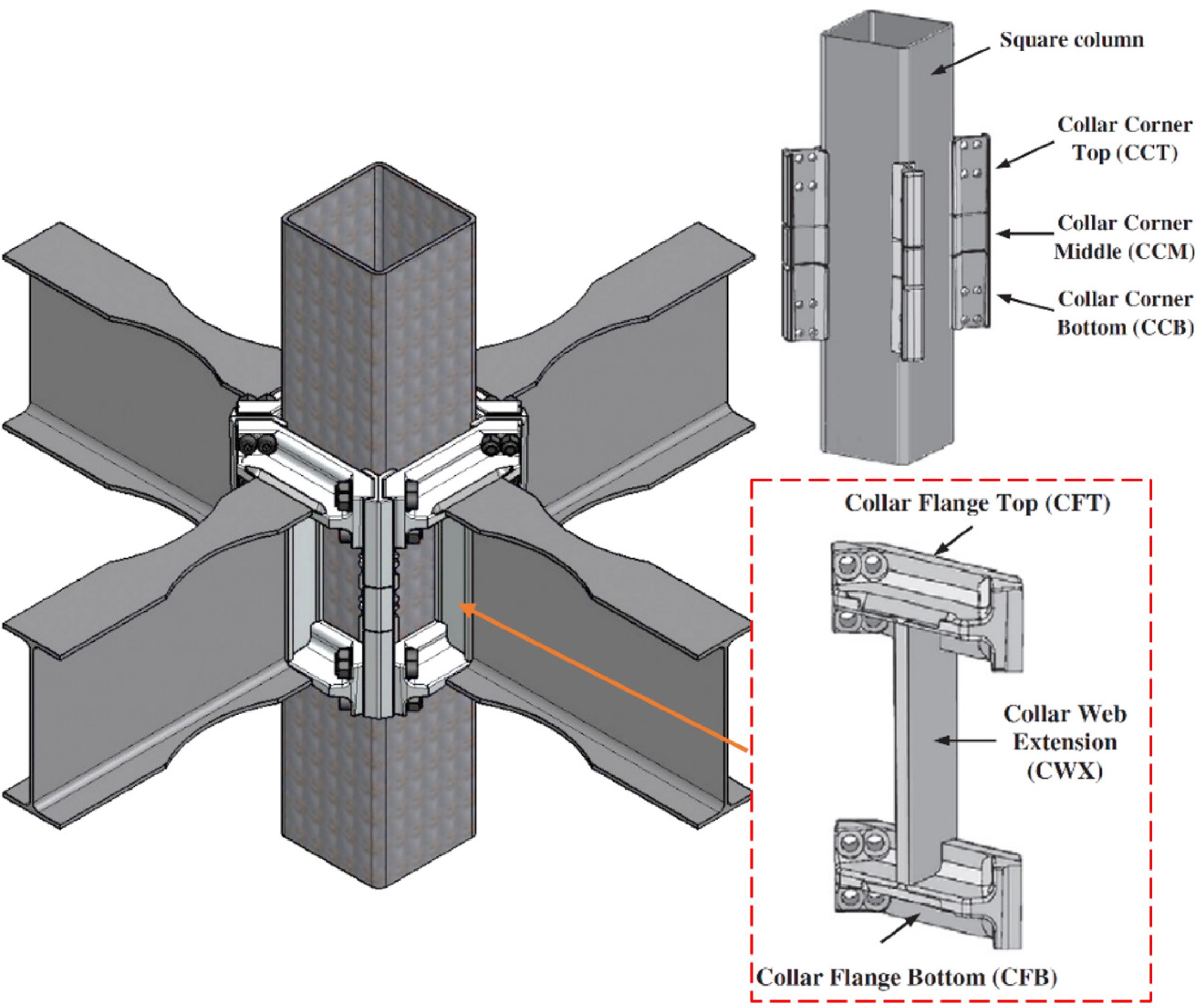

Figure 2.

Box column with ConXL connections, showing the details of the attached collar corner assemblies. Figure created by the authors.

The ConXL connection has attracted significant attention as a standardized, cost-effective, special moment biaxial connection for building applications. This connection incorporates wide-flange beams, concrete-filled square Hollow Structural Section (HSS) or built-up columns, high-strength bolts, a collar flange assembly, and a collar corner assembly. It has been prequalified and codified by the American Institute of Steel Construction (AISC). Numerical studies by Rezaeian et al.[11] and Shahidi et al.[12] examined the cyclic behavior of the ConXL connection without concrete filling in the column. Their results revealed that the seismic behavior of ConXL connections is appropriate, with no significant local buckling observed in the columns.

The seismic performance of metallic beam–column connections is usually validated through experimental and numerical studies[13,14]. The ConXL connection effectively addresses the issue of global bucking in box column sections. Extensive research on box columns and their connections has contributed to this achievement. Tsai et al.[15] identified that conventional connections in box columns are susceptible to damage, prompting the development of new connection designs with side stiffeners. Their experimental results demonstrated stable hysteresis loops with no degradation in strength or stiffness for the proposed connection. Similarly, Mirghaderi and Mahmoud[16] confirmed that the panel zone in box column connections exhibited yielding, influencing the overall behavior of the system. This finding highlighted the necessity of strengthening such connections, when designed in compliance with seismic design codes. The results reported in[17] highlight that failure modes such as the columns' hinge mechanism remain common under strong seismic events, despite the regulation of bending moment by various seismic codes in different countries. Furthermore, a study of the Wenchuan Earthquake (China, 2008) underscored the significance of bidirectional seismic action as a key factor contributing to failures of the columns' hinge mechanism[18].

Most studies on the seismic performance of beam–column connections conducted on three-dimensional (3D) beam–column connections have focused on concrete structures[19−21], composite structures[22−24], or prestressed reinforced concrete structures[25−27]. However, a few relevant studies on steel beam–column connections have also been reported[28,29]. The results indicated that in beam–column joints, the effects of biaxial loading cannot be ignored in the analysis and design of spaced ductile moment-resisting frames. Green et al.[30] conducted a bidirectional load test study of a spaced semi-rigid steel beam–column joint with a floor; however, they did not show any contrast with a unidirectional loading test. Wang et al.[31] conducted a bidirectional test on a steel beam with circular tubular column connections with an outer diaphragm and found that bidirectional loading may reduce the connection strength in the decoupled loading plane but increase the connection strength and ductility in the coupled loading plane.

Fire and post-fire scenarios significantly influence the structural response of steel frames, primarily by degrading material properties such as strength, stiffness, and ductility as a result of elevated temperatures. These effects can result in reduced load-carrying capacity, increased deformation, and potential failure of critical connections, ultimately undermining their seismic response capacity. Although extensive research has been conducted on the fire performance of standard steel frame connections[32,33], there is a notable gap in the literature concerning the behavior of ConXL connections under fire and post-fire conditions. Despite their widespread use and robust performance in seismic applications, the lack of studies analyzing their structural response in these scenarios underscores the need for comprehensive investigations to ensure their safety and reliability under extreme thermal conditions.

A review of studies conducted on ConXL connections confirms their robust performance under seismic actions. The design details of these connections are included in regulations such as ANSI/AISC 341-22[34] for seismic design and ANSI/AISC 358-22[35], where the ConXL connection is prequalified for special and intermediate steel moment frames for seismic applications. Despite the demonstrated performance of the ConXL connection under seismic conditions, its behavior under fire has not yet been comprehensively investigated. Thus, its behavior under fire remains unknown, and completing a comprehensive study is required. Additionally, no prior studies have addressed the effects of variable temperatures on ConXL connections. This paper seeks to address this gap in the literature through a comprehensive numerical investigation of the behavior of ConXL connections under fire.

-

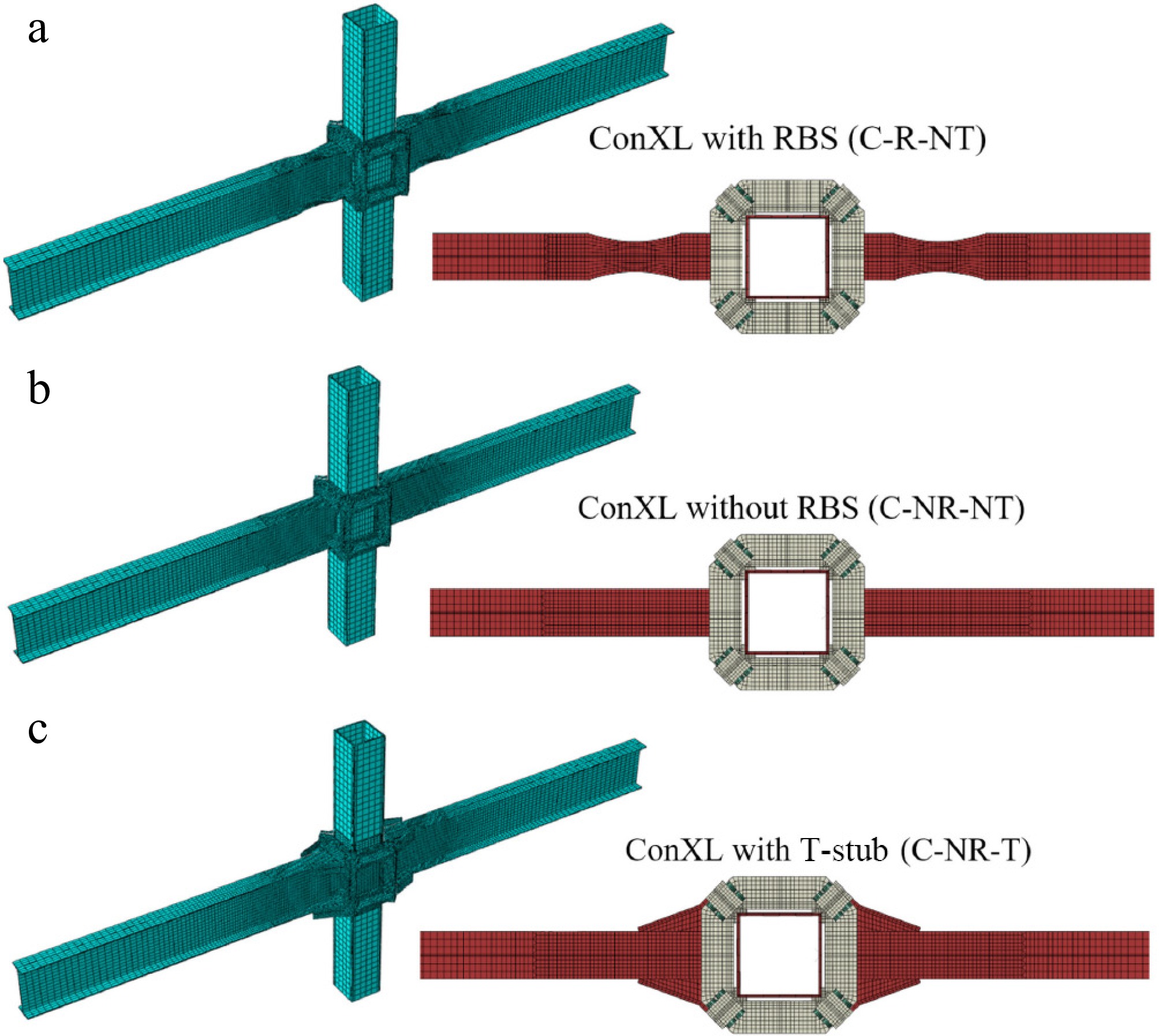

FE models were used to analyze the performance of the ConXL connection. Figure 3 illustrates the details of the different ConXL connection models' configurations studied here. As shown in this figure, three types of ConXL were examined. For each model, a name was designed that consisted of four parts. The first part, C, represents the ConXL. The second letter is related to the reduced beam section (RBS), which indicates the model with (R) or without (NR) an RBS. The third letter represents the T-stub, where T and NT are used for models with and without a T-stub, respectively. Two numbers as two parts are used at the end of name to represent the thickness of the columns and the temperature applied to the model. First, the model C-NR-NT was created according to the ANSI/AISC 341-22 standards[34]. Then a RBS was incorporated in the beam to create the C-R-NT model. Finally, a T-stub was added to the ConXL as a proposed idea to improve the connection, thus resulting in the C-NR-T model.

Figure 3.

Types of ConXL connections considered in the parametric study: (a) ConXL with an RBS (the C-R-NT model); (b) ConXL without an RBS (C-NR-NT model); and (c) ConXL with a T-stub (C-NR-T model).

The beam and columns (width: 24 mm × 68 mm; cross-section: 406 mm × 406 mm) with thicknesses of 12 and 20 mm, respectively, were used for the simulation. The connection was designed according to the AISC/ANSI 358-22 standards[35]. First, the models were analyzed under cyclic loading (Tu = 20 °C). Then, to consider the behavior of the model, different temperatures, Tu = i, were applied and the models were analyzed under cyclic loading. For this consideration, the temperatures of Tu = 200, 400, and 600 °C were adopted.

According to ANSI/AISC 358-22[35], the beam and connections were designed, based on the computed probable maximum moment at the plastic hinge, Mpr, as presented in Eq. (1):

$ M\mathrm{_{pr}}=C\mathrm{_{pr}}R\mathrm{_y}F\mathrm{_y}Z_{\mathrm{e}} $ (1) where, Fy is the specified minimum yield stress of the yielding element; Ze is the effective plastic section modulus of the section at the location of the plastic hinge; Ry represents the ratio of the material ultimate stress, Fu, to the expected material yield stress, Fy; and Cpr is computed as (Fy + Fu) / (2Fy). In addition, the shear force at each plastic hinge location, Vh, is determined from a free-body diagram of the portion of the beam between the plastic hinge locations, Lh. This calculation assumes that the moment at the center of the plastic hinge is Mpr and the gravity load, Vgravity, acting on the beams between plastic hinges, is as presented in Equation (2):

$ {V}_{\rm h}=\dfrac{{M}_{\rm pr}}{{L}_{\rm h}}+{V}_{\rm{gravity}} $ (2) Finite element models and simulation technique

-

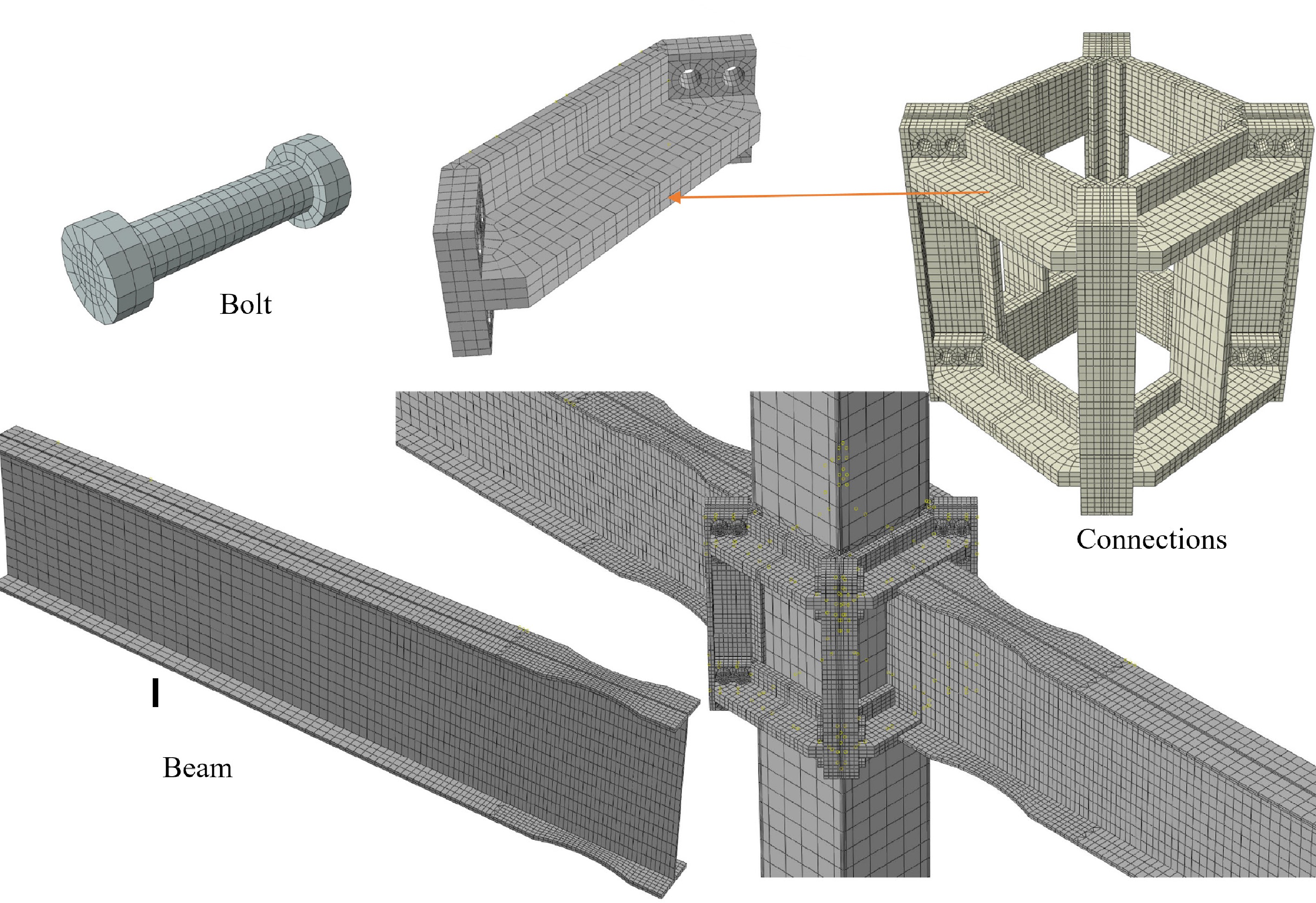

In this paper, to simulate the FE models, ABAQUS software was used. To simulate all parts of the models, the C3D8R solid element was used. This solid element is an eight-node brick element containing a reduced integration aspect with hourglass control. The tangential behavior with a friction coefficient of 0.4 was used for the contact of the bolts. Normal behavior with hard contact was used for other elements that were touching. For meshing the elements, standard structural meshing with hexahedral mesh was utilized. Accordingly, the mesh size was 2–20 mm for different elements. For the beam, in the predicted location of plastic hinge formation, a smaller mesh size was used than that in the beam length outside the area of plastic hinge formation. A very small mesh size was applied for the bolts and other components with short lengths. Figure 4 illustrates the schematic view of the model with the selected mesh sizes.

Boundary conditions and materials

-

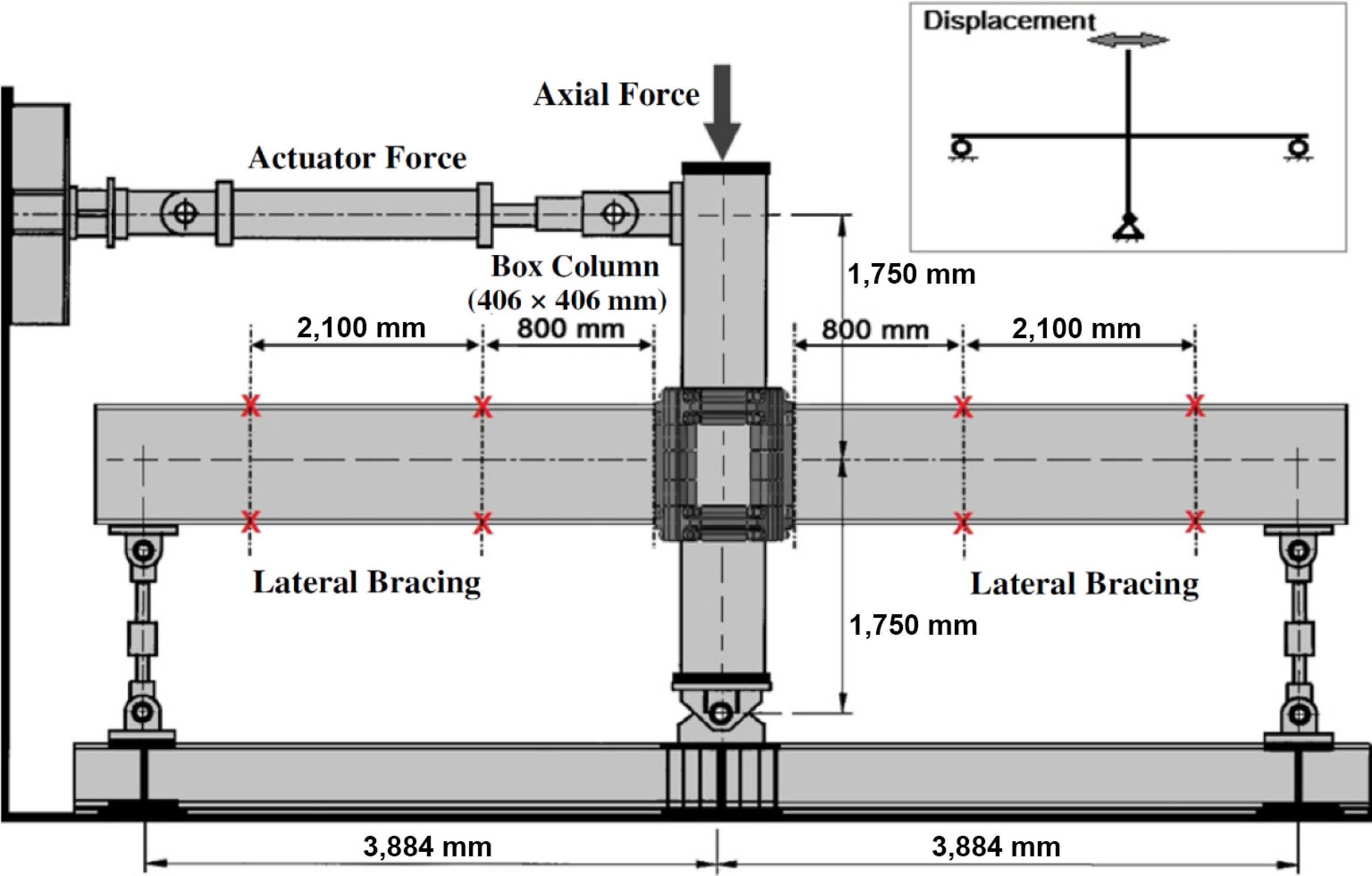

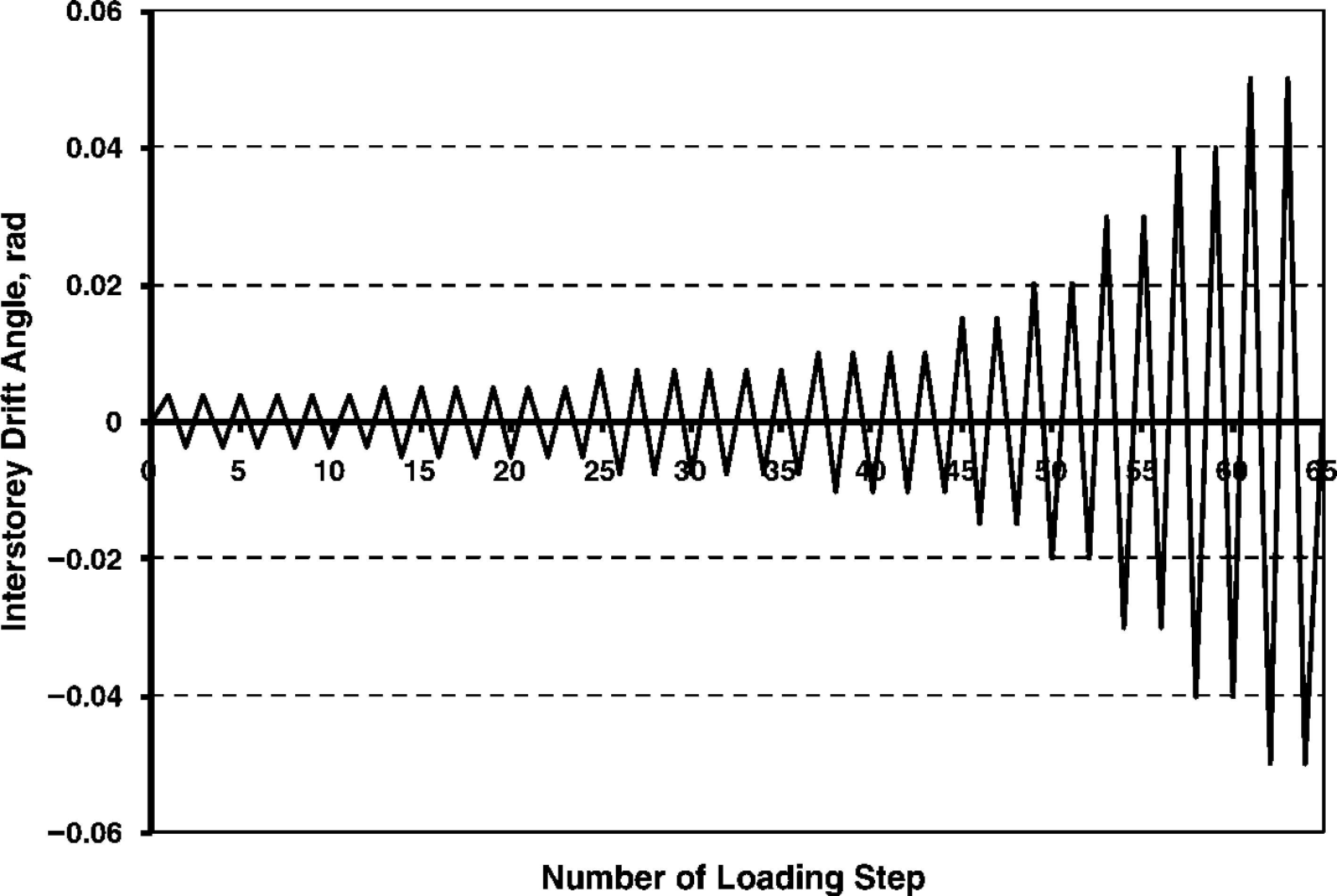

In this paper, each system comprising two beams as a planar state are considered, as shown in Fig. 5. According to ANSI/AISC 358-22[35], the acceptable rotation of connection is 0.04 rad. Therefore, lateral loads are applied to the columns to achieve an inter-story drift of 5% to consider the connection with a rotation of 0.04 rad and to understand the system's behavior under rotation greater than the limitations of ANSI/AISC 358-22[35].

To simplify the moment frame, it is assumed that the height and length of the frame are equal to 3,500 and 7,768 mm, respectively. The lateral loading is applied to the model as shown in Fig. 6, according to the ANSI/AISC 358-22[35] specifications. A36 steel was used for the beams and columns with a yield stress (Fy), ultimate stress (Fu), and modulus of elasticity equal to 240 MPa, 370 MPa, and 200 GPa, respectively. On the basis of ASTMA574[36], the bolts were modeled using Fy = 1,050 MPa and Fu = 1,150 MPa. Finally, for the collar system, material properties of Fy = 390 MPa and Fu = 510 MPa were used according to ASTM A572 Gr50.

Figure 6.

Cyclic loading diagram based on ANSI/AISC 358-22[35].

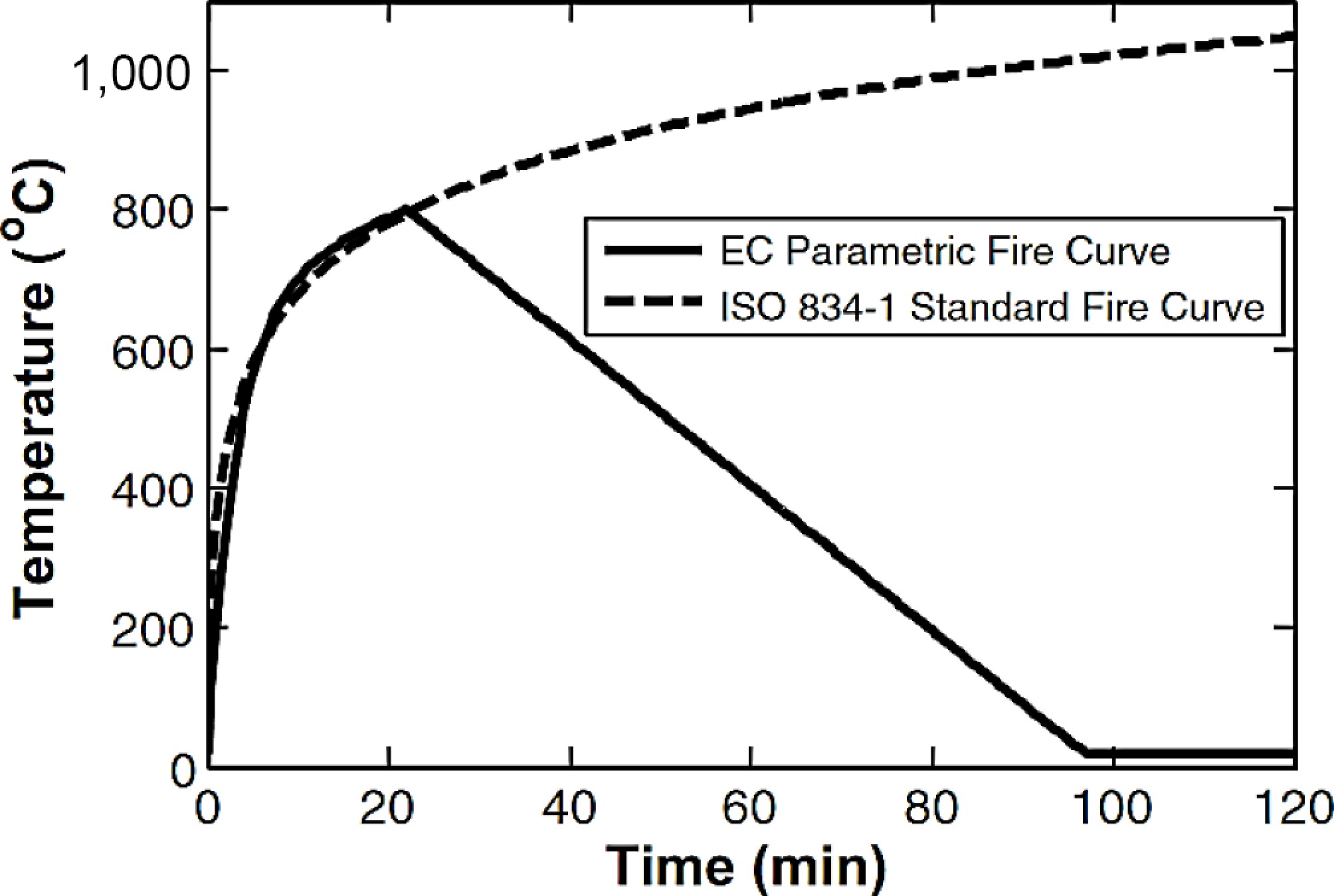

As an alternative, time–temperature curves from International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 834[37], and EN 1991: 1-2[38] (the Eurocode parametric fire curve) can be used to consider the effects of fire. As shown in Fig. 7, ISO curves only have a heating phase. These curves are commonly used for furnace-based testing and are not influenced by ventilation or other factors that would affect an actual fire. Accordingly, the ISO 834 standard[37] was used in this paper. In contrast, Eurocode parametric curves include a cooling phase and vary depending on the thermal inertia of the enclosure (b), the opening factor (O), and the fire's loading density (qt,d). Varying these parameters affects the peak fire temperature, the fire's duration, and rate of heating and cooling. This cooling phase is important, as it results in thermal contraction, which can produce large tensile forces that cause connections to fail[39,40].

Calibration and verification of the FE model

-

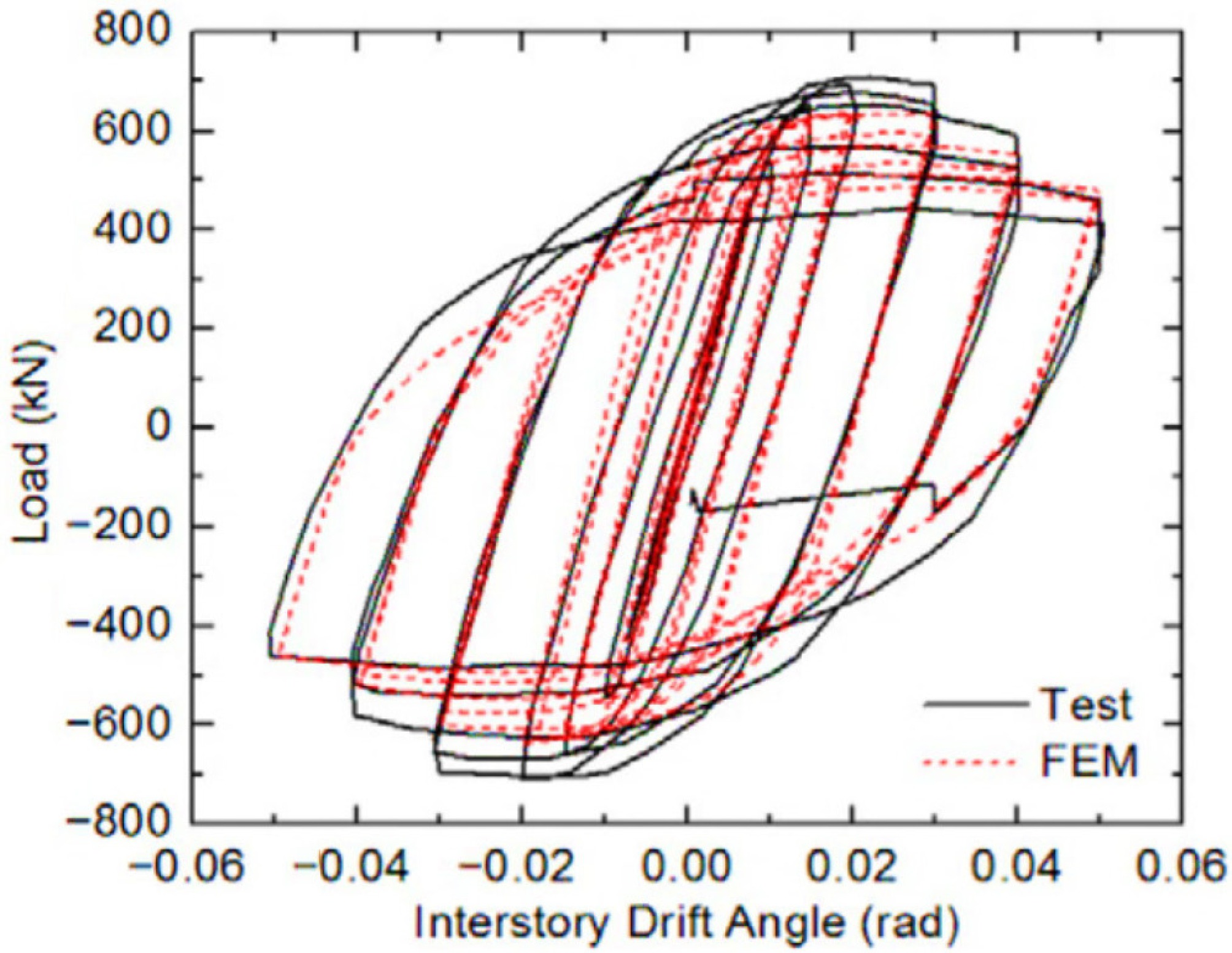

To calibrate and verify the FE numerical model, an experimental test reported in[41] was selected and simulated using ABAQUS. Accordingly, the test results and FE results are compared in Fig. 8. As can be observed in this figure, the two hysteretic curves are in good agreement. By achieving an acceptable error (less than 10% to calculate the ultimate strength) in this model, other FE models will be considered with confidence (because of the acceptable error) in the accuracy of the results.

Figure 8.

Comparing the test results presented in ConXtech[41] against the FE simulation's results.

-

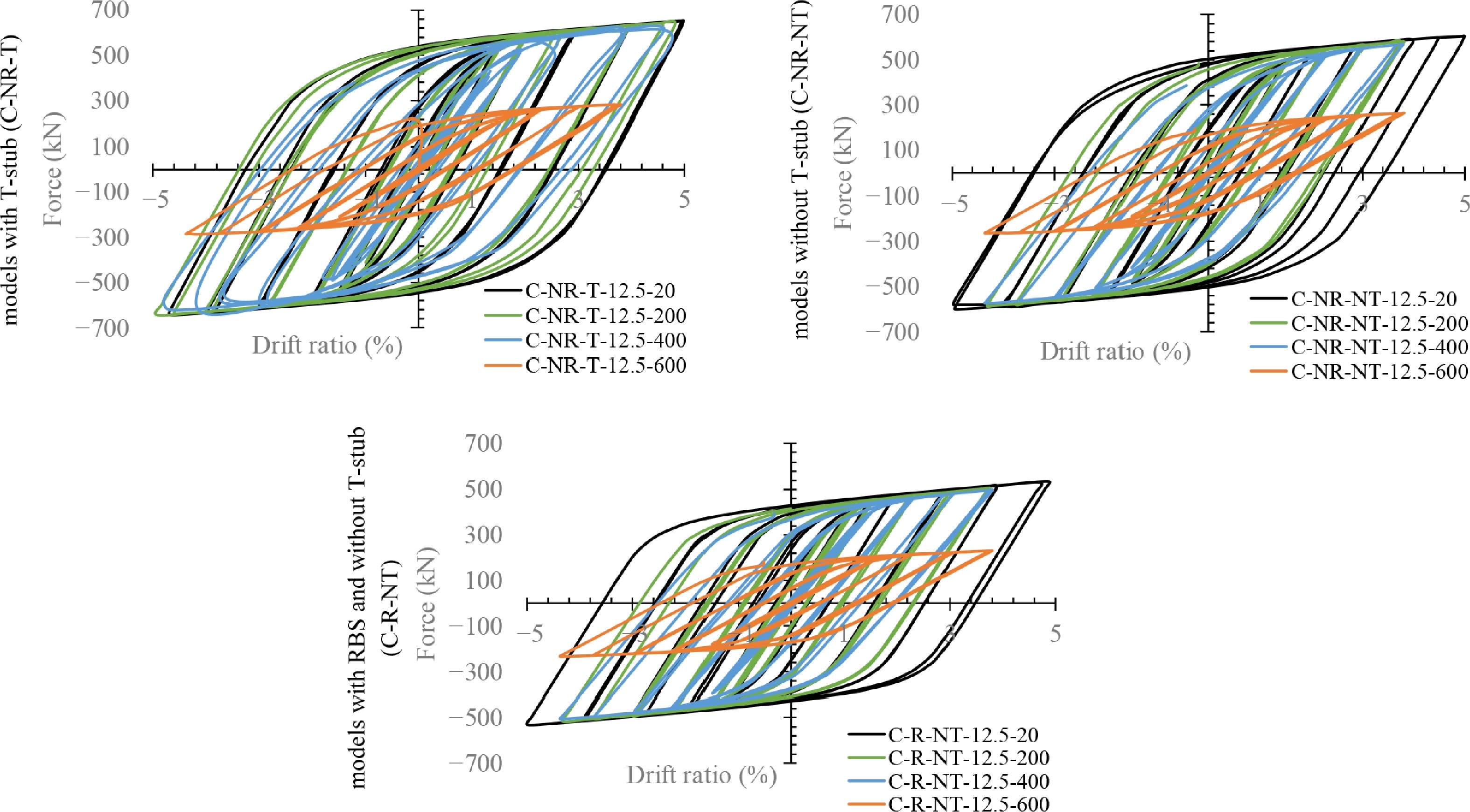

In Fig. 9, the hysteresis curves of the C-NR-T, C-NR-NT, and C-R-NT FE models are compared for the different temperature values considered. As shown in this figure, as expected, fire affects the response of the models. The rate of reduction is different from the rate of the increase in temperature. At Tu < 400 °C, no considerable reduction is seen in the hysteresis curves. Moreover, by increasing the temperature from ambient temperature to 400 °C, the rate of reduction in hysteresis is much lower than the one observed for Tu = 600 °C. Accordingly, the rate of reduction and the effect of the variable on the response of the models are investigated in the next subsections. RBS (C-R-NT) connections cause a lower ultimate strength than the other types of connection at all temperatures.

Yielding scenarios

-

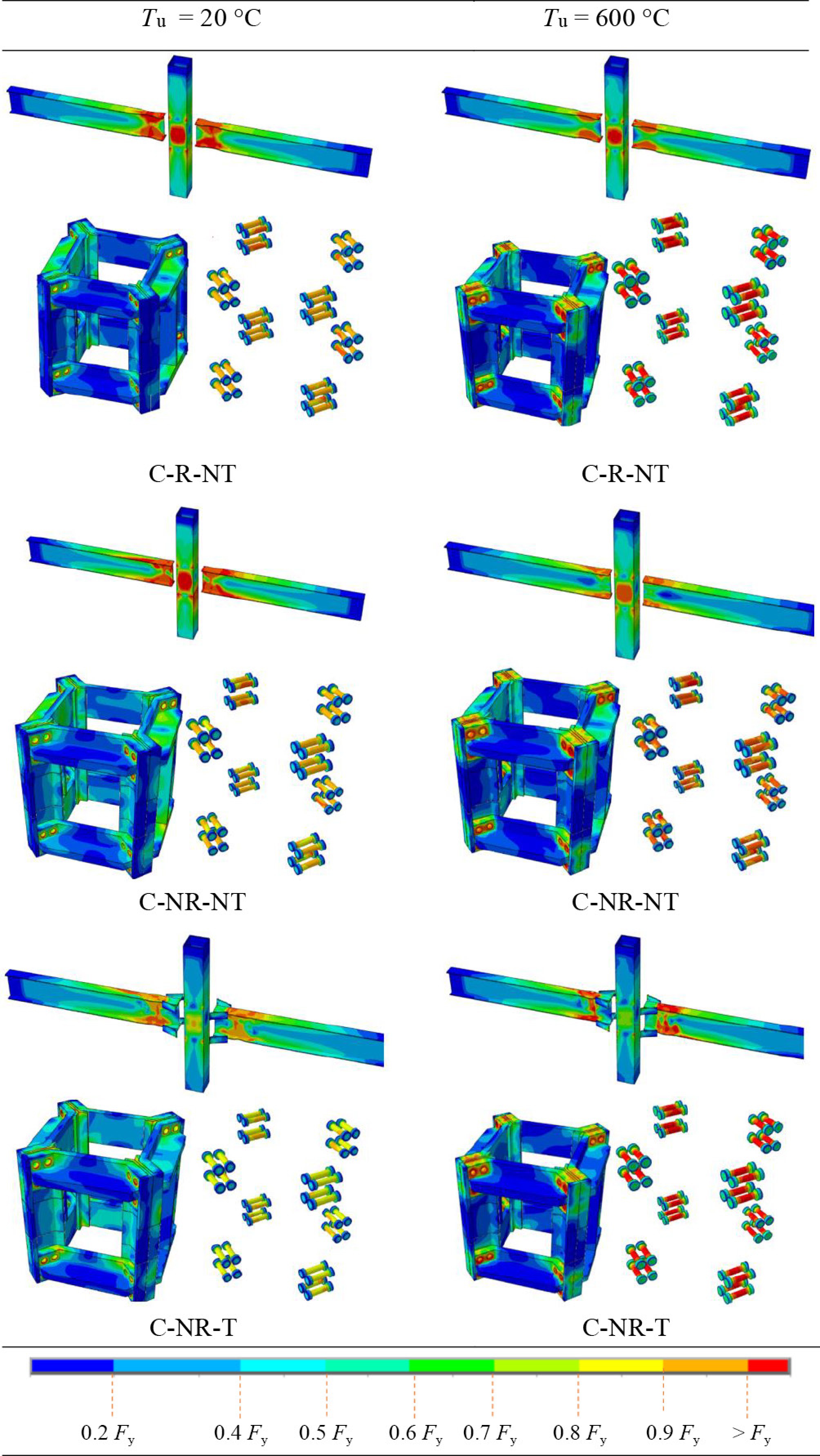

The von Misses stresses of the ConXL connection components are shown in Fig. 10 to consider the yielding and hinge formation over the elements. To simplify the discussion of the results, only the elements at ambient temperature and at Tu = 600 °C are shown. As illustrated in Fig. 10, for all types of elements, hinges form at the two ends of the beams, as expected, to produce desirable performance. The collar under ambient temperature for all types of connection remains elastic, which confirms the suitable behavior of the ConXL. For the conventional ConXL with and without an RBS, yielding emerges on the panel zone of the columns, but the column can carry the load. A suitable hinge forms on the proposed ConXL, where the hinge is formed at the end of T-stub, which is far from the columns and collar. Moreover, no yielding occurred on the columns at Tu = 600 °C, and all types of connections show acceptable performance. Although the connection has been designed for ambient temperatures, negligible yielding occurs at the collar system around the bolts. However, all bolts managed to yield but were not ruptured. The T-stub made the system have the yield as in ambient system, which is considerable.

The effect of the T-stub on the hysteresis curves of the system

-

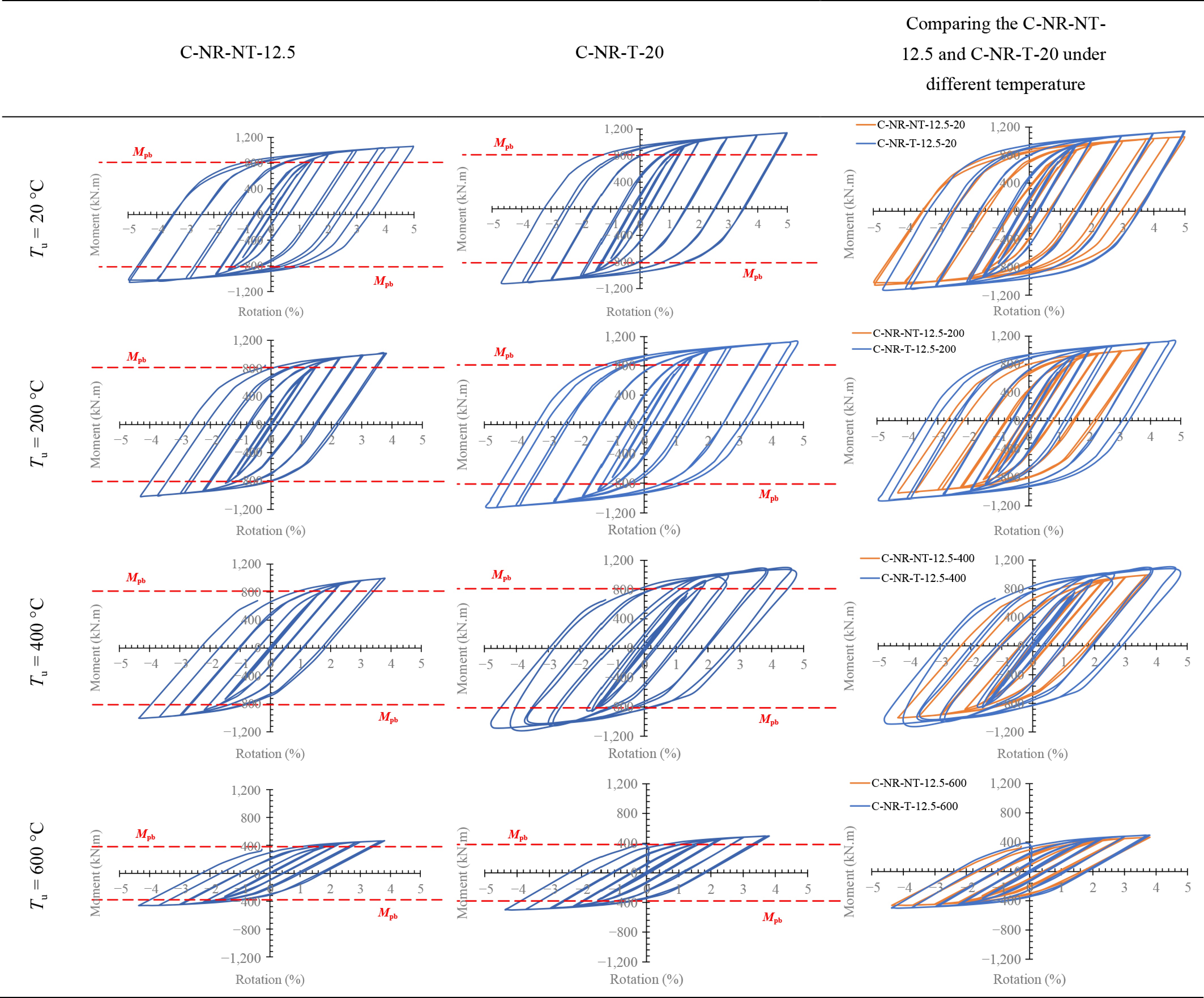

Figure 11 illustrates the hysteresis curves of the C-NR-NT and C-NR-T models at different temperatures. As revealed in this figure, all models present a stable hysteresis curve with no degradation in strength and stiffness, and no pinching in the curves. For all specimens, for rotations more than 0.04 rad, the moment is more than 80% of the plastic moment of the beam (Mpb). As shown, although there is no filler concrete or continuity plates in all specimens, they all have acceptable seismic behavior and seismic post-fire behavior under cyclic loading. Comparing the models with and without a T-stub indicates that the T-stub improves the hysteresis curve of the ConXL connection. The connections with the T-stub show a greater rotation capacity than the conventional ConXL. The connection with higher rotation capacity has higher ductility and stability. In addition, adding the T-stub improved the hysteresis. This represents an improvement in the strength and energy dissipation, as will be discussed in the following subsections.

Ultimate strength

-

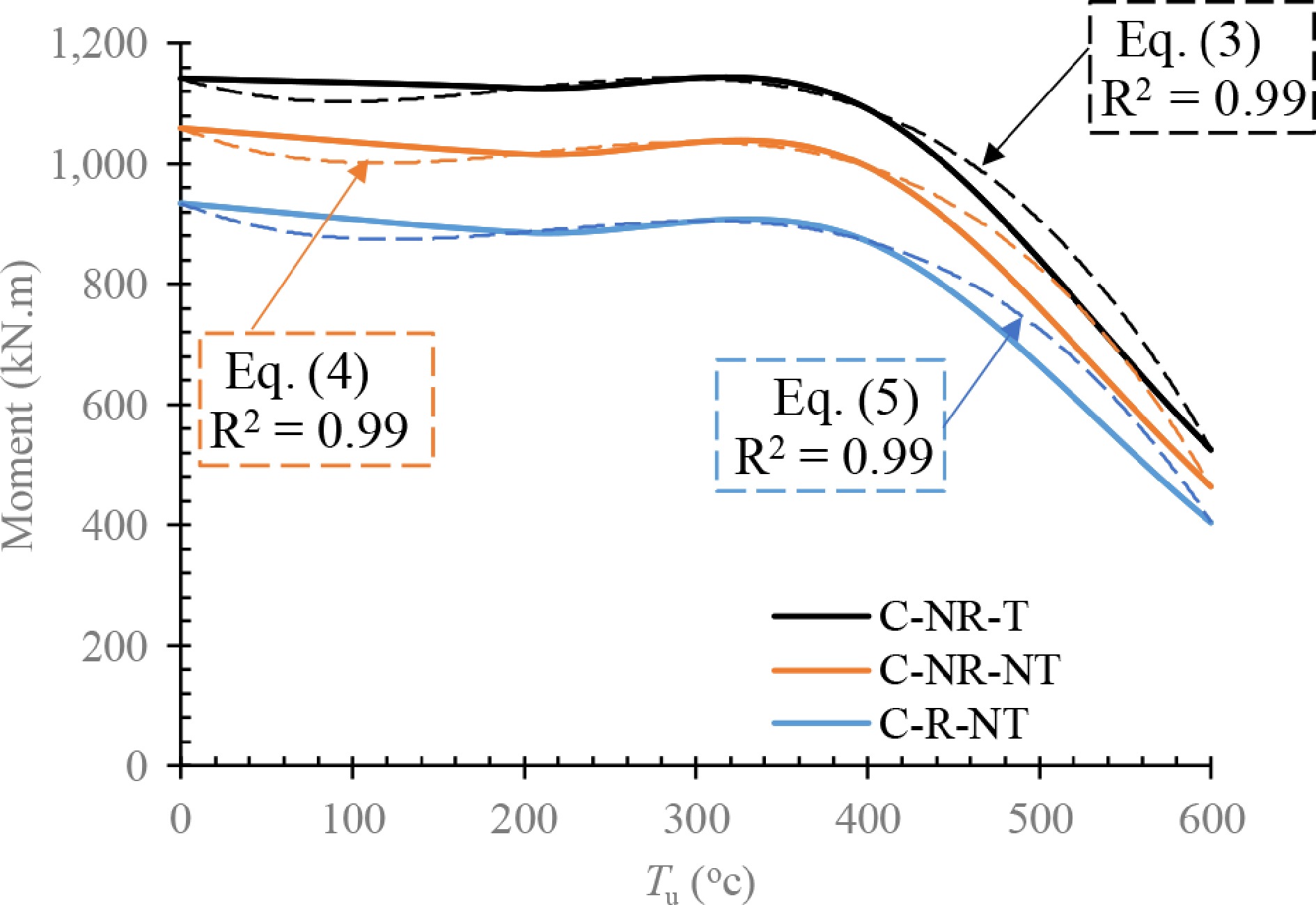

In Table 1, the ultimate strength of the FE models is listed. The results revealed that by increasing Tu, the capacity of the system is reduced, but the rate of reduction for the conventional ConXL (with and without RBS) and yjr proposed ConXL are different. When the Tu rises from the ambient temperature to 400 °C, the ultimate strength is reduced by 7%, 6%, and 4%, respectively, for the conventional ConXL with and without an RBS and the proposed ConXL. The noticeable finding is that the T-stub has a considerable effect in the Tu = 600 °C scenario. At this temperature, the reduction in the ultimate strength of the conventional ConXL (with and without an RBS) is around 56%, but with a T-stub, it improved by 24%. Moreover, a comparison of the results of the conventional ConXL (without an RBS) and the proposed ConXL indicates that the T-stub causes an increase in the ultimate strength of the system by 1.08, 1.11, 1.10, and 1.87 times for Tu = 20, 200, 400, and 600 °C, respectively. Therefore, the T-stub has a considerable effect on the strength of the system, especially at higher temperatures. Comparing the conventional ConXL with and without an RBS reveals that with the RBS, the ultimate strength is reduced by around 12% for all temperatures. Therefore, the RBS has a constant effect on the connection for all temperatures. Referring to Fig. 11, it can be observed that the moment capacity of all connections studied remains practically constant under 400 °C and suffers a linear drop in capacity between temperature ranges of 400–600 °C. To predict the behavior of the system with the ConXL connection, Equations (3), (4), and (5) are proposed. These equations help structural designers to create a primary design and to predict the post-fire performance of the system.

Table 1. Comparing the ultimate strength of the models.

Models Pu (kN) M (kN·m) $ \dfrac{M_{T_{\mathrm{u}}=i}}{M_{T_{\mathrm{u}}=20\; \text{°C}}} $ EModel with T/

EModel without TEModel with RBS/

EModel without RBSC-NR-T-12.5-20 652.33 1,141.6 1.00 1.08 C-NR-T-12.5-200 643.00 1,125.3 0.99 1.11 C-NR-T-12.5-400 623.23 1,090.7 0.96 1.10 C-NR-T-12.5-600 495.59 867.28 0.76 1.87 C-NR-NT-12.5-20 605.45 1,059.5 1.00 C-NR-NT-12.5-200 580.70 1,016.2 0.96 C-NR-NT-12.5-400 568.60 995.05 0.94 C-NR-NT-12.5-600 264.79 463.38 0.44 C-R-NT-12.5-20 534.29 935 1.00 0.88 C-R-NT-12.5-200 506.37 886.15 0.95 0.87 C-R-NT-12.5-400 497.95 871.42 0.93 0.88 C-R-NT-12.5-600 231.32 404.81 0.43 0.87 Stiffness

-

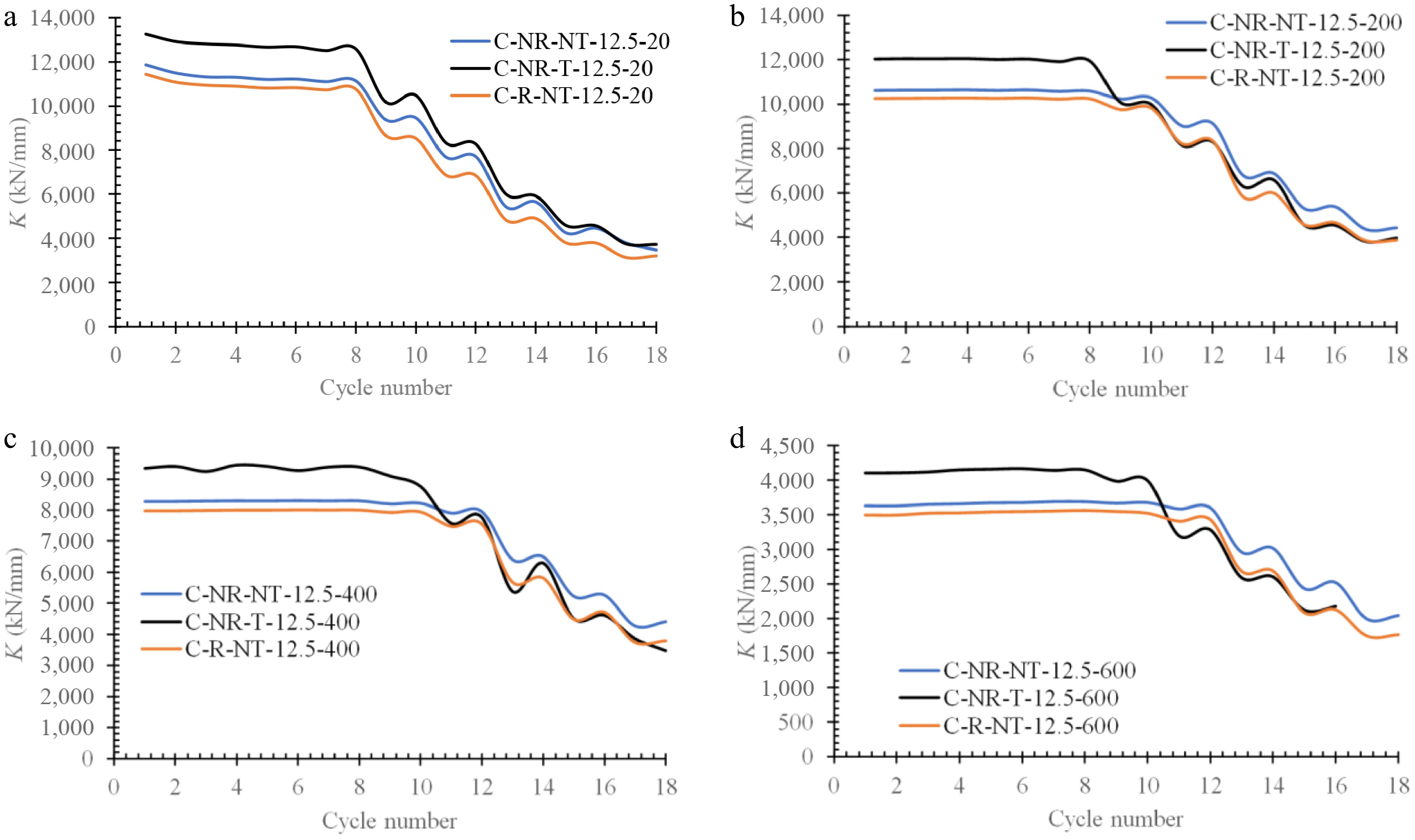

As expected, by increasing the applied loading as well as the temperature, the stiffness of any structures tends to be reduced. The stiffness K of the FE models is listed in Table 2. At all temperatures applied, the T-stub causes a 13% increase in K, and the RBS connection causes a 4% decrease in the system's K. The results show that the presence of a T-stub or RBS connection has the same trend at all temperatures. Moreover, the presence of a T-stub or RBS showed the same decreasing trend with increasing temperatures. Referring to Table 2, it can be seen that by increasing the temperature from the ambient temperature to 200, 400, and 600 °C, the K of all models decreases by around 10%, 30%, and 70%, respectively. It confirms that the rate of reduction up to 400 °C is lower than that at temperatures greater than 400 °C.

Table 2. Comparing the elastic stiffness of the models.

Models K (kN/mm) $ \dfrac{K_{T_{\mathrm{u}}=i}}{K_{T\mathrm{_u}=20\; \text{°C}}} $ EModel with T/

EModel without TEModel with RBS/

EModel without RBSC-NR-T-12.5-20 13,256 1.00 1.12 C-NR-T-12.5-200 12,034 0.91 1.13 C-NR-T-12.5-400 9,337.8 0.70 1.13 C-NR-T-12.5-600 4,102.0 0.31 1.13 C-NR-NT-12.5-20 11,850 1.00 C-NR-NT-12.5-200 10,621 0.90 C-NR-NT-12.5-400 8,266.5 0.70 C-NR-NT-12.5-600 3,630.5 0.31 C-R-NT-12.5-20 11,435 1.00 0.96 C-R-NT-12.5-200 10,246 0.90 0.96 C-R-NT-12.5-400 7,972.8 0.70 0.96 C-R-NT-12.5-600 3,498.1 0.31 0.96 Comparing the results confirms that the reduction in elastic stiffness is strongly affected by temperature changes rather than type of connection. For this reason, in Fig. 12, the K of the models is plotted versus the applied temperature.

The proposed equations, Eqs. (3) to (5), have been based on the results of the paper and are useful for primary design. Subsequently, after determining the configuration and predicting the behavior of the structure, suitable analysis is required.

$ \begin{split}& M=-0.00005\;{{{T}_{\rm u}}}^{3}+0.0062\;{{{T}_{\rm u}}}^{2}-0.89\;{T}_{\rm u}+1141\\&\quad\rm ConXL\; (with\; T{\text-}stub, \;without\; RBS)\end{split} $ (3) $\begin{split}& M=-0.00005\;{{{T}_{\rm u}}}^{3}+0.0069\;{{{T}_{\rm u}}}^{2}-1.16\;{T}_{\rm u}+1059\\&\quad\rm ConXL\; (with\; T{\text-}stub,\; without\; RBS)\end{split} $ (4) $\begin{split}& M=-0.00005\;{{{T}_{\rm u}}}^{3}+0.0065\;{{{T}_{\rm u}}}^{2}-1.14\;{T}_{\rm u}+935\\&\quad\rm ConXL\; (with \;T{\text-}stub,\; without\; RBS)\end{split} $ (5) As shown in Fig. 13, the rate of the reduction in stiffness is dissimilar at different temperatures. Generally, the downward and decreasing process of stiffness with a T-stub starts earlier than that of the conventional ConXL. At ambient temperatures, both the conventional ConXL and the ConXl with a T-stub show a reduction in their rotation by 1.5%. At Tu = 200 °C and Tu > 200 °C, this range is 1.5% and 2% for the conventional ConXL and 2% and 3% for the ConXL with a T-stub, respectively. Although the ConXL with a T-stub has a greater stiffness than the conventional ConXL, it tends to reduce sooner than the conventional ConXL.

Figure 13.

Comparing the elastic stiffness of the C-NR-NT-12.5, C-NR-T-12.5, and C-R-NT-12.5 models at (a) Tu = 0 °C, (b) Tu =200 °C, (c) Tu = 400 °C, and (d) Tu = 600 °C.

Energy dissipation

-

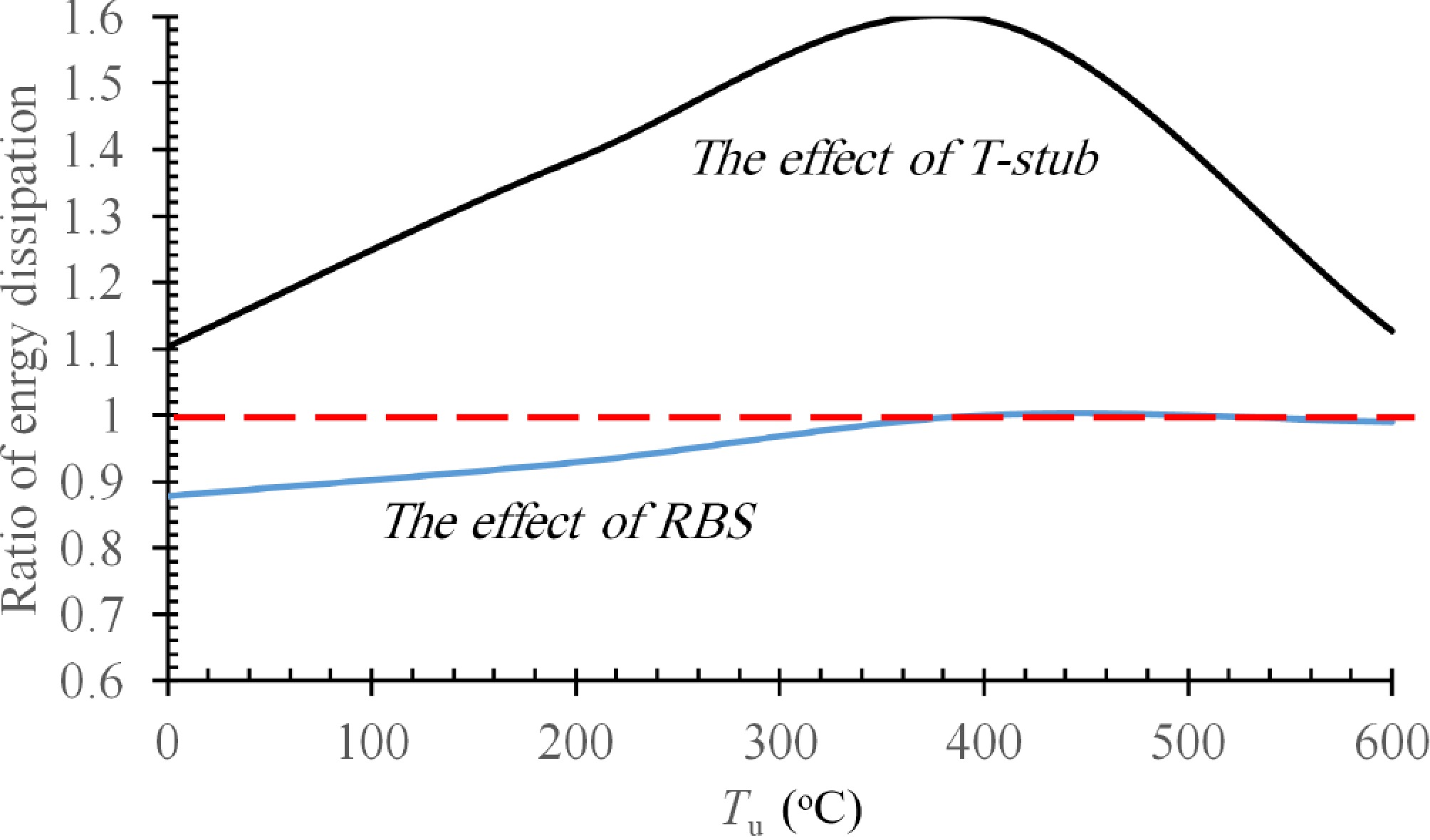

The energy dissipation E of the analyzed models is listed in Table 3. Comparing the results listed in Table 3 indicated that the T-stub provides an enhancement in the energy dissipation E of the connections. With the T-stub, E improves by 10%–60%, which is significant. This finding is plotted in Fig. 14, where the vertical axis represents the ratio of the E of the compared models to the E of the C-NR-NT model. A noticeable finding is that an RBS affects the E of the system under ambient temperatures and has a negligible impact on the E of the system at high temperatures.

Table 3. Comparing the energy dissipation of the models.

Models E (kN·m) $ \dfrac{E_{T_{\mathrm{u}}=i}}{E_{T_{\mathrm{u}}=20\; \text{°C}}} $ EModel with T/

EModel without TEModel with RBS/

EModel without RBSC-NR-T-12.5-20 270.78 1.00 1.10 C-NR-T-12.5-200 234.42 0.87 1.39 C-NR-T-12.5-400 213.99 0.79 1.60 C-NR-T-12.5-600 69.20 0.26 1.13 C-NR-NT-12.5-20 245.25 1.00 C-NR-NT-12.5-200 169.14 0.69 C-NR-NT-12.5-400 134.14 0.55 C-NR-NT-12.5-600 61.37 0.25 C-R-NT-12.5-20 215.51 1.00 0.88 C-R-NT-12.5-200 157.23 0.73 0.93 C-R-NT-12.5-400 134.18 0.62 1.00 C-R-NT-12.5-600 60.78 0.28 0.99

Figure 14.

Comparing the energy dissipation capacity of the models in the different temperature scenarios explored.

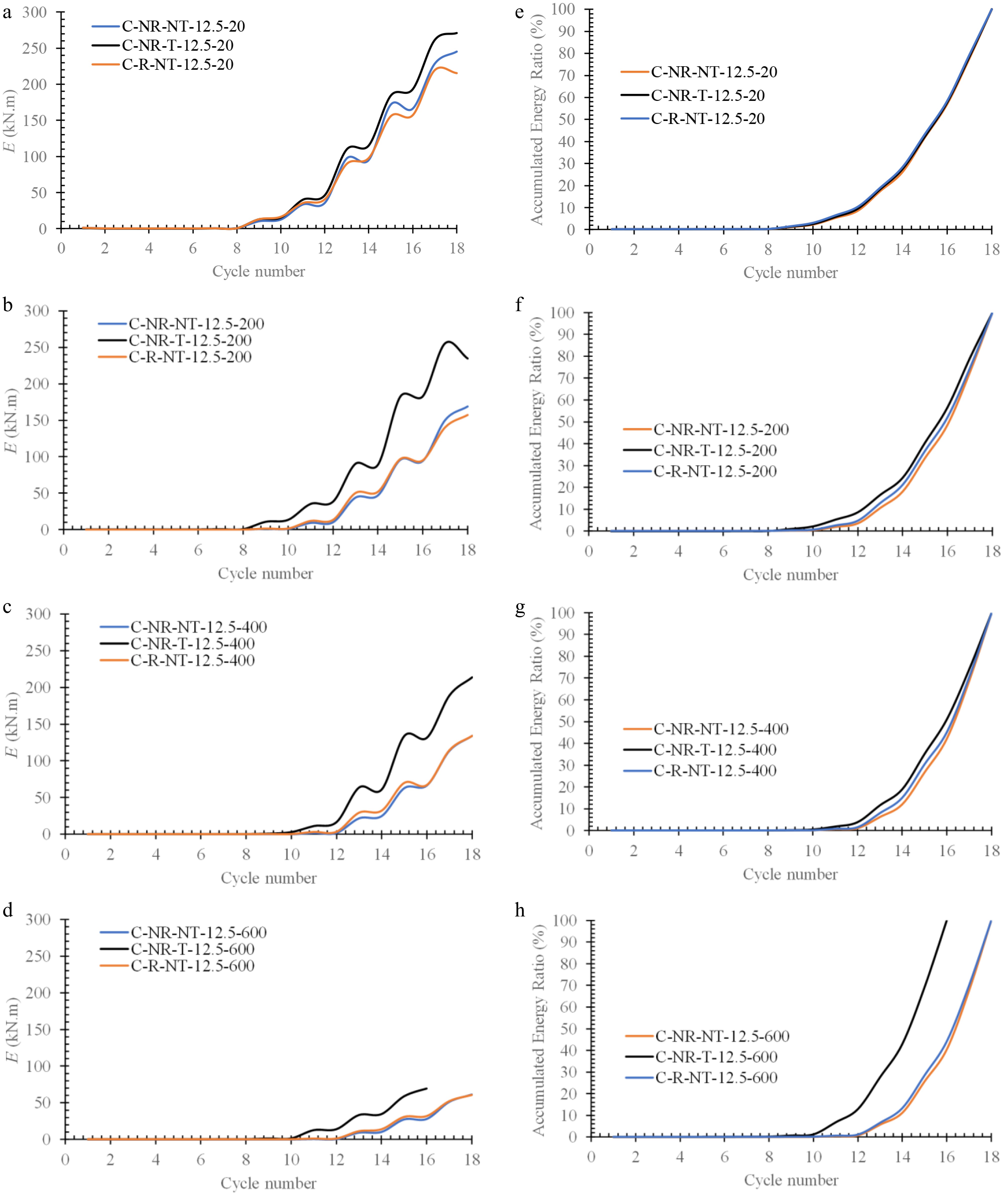

In Fig. 15, the energy dissipation of the models versus the cycle number is plotted. According to the figure, the rate of E is dissimilar at different temperatures, whereas the ConXL connections with and without an RBS have a similar rate. At ambient temperatures, both the conventional ConXL and the ConXl with a T-stub initially have an energy dissipation of 1.5%, which coincides with the reduction in stiffness. Correspondingly, at Tu = 200 °C and Tu > 200 °C, this range is 1.5% and 2% for the conventional ConXL and the ConXL with a T-stub, and 2% and 3%, respectively.

Figure 15.

Comparing the energy dissipation of the C-NR-NT-12.5, C-NR-T-12.5, and C-R-NT-12.5 models at (a) Tu = 20 °C, (b) Tu =20 °C, (c) Tu = 400 °C, (d) Tu = 600 °Cand the accumulated energy ratio of the C-NR-NT-12.5, C-NR-T-12.5, and C-R-NT-12.5 models at (e) Tu = 0 °C, (f) Tu = 200 °C, (g) Tu = 400 °C, (h) Tu = 600 °C.

-

This paper investigated the behavior of the ConXL connection, including an innovative enhancement to improve its seismic and performance under fire after seismic loading was applied, using parametric and numerical analyses.

(1) Although ConXL connections at ambient tempratures, with or without an RBS and with a T-stub, showed stable performance without a loss of stiffness or strength, even unfilled with concrete. At 600 °C, they exceeded 0.04 radians of rotational capacity without plastic hinges, meeting AISC's special moment frame standards.

(2) The temperature affects the response of the connections. At 400 °C, strength dropped by 7%, 6%, and 4% for the conventional ConXL with an RBS, that without an RBS, and the T-stub-enhanced ConXL, respectively. At 600 °C, the conventional ConXL lost ~56% of its strength, whereas the T-stub-enhanced system lost 24%.

(3) The T-stub-enhanced ConXL connection demonstrates superior performance under heat, particularly in its energy dissipation characteristics. At room temperature, both the conventional and T-stub-enhanced connections started dissipating energy at the same degree of rotation (1.5%).

(4) As temperatures rose above 200 °C, the T-stub-enhanced connection required a higher rotation (3%) to start dissipating energy compared with the conventional one (2%). This indicates that the enhanced connection is more robust and maintains its stiffness for longer under elevated temperatures, highlighting its advantage for practical high-temperature applications.

(5) To complete and expand the recent study, it is recommended to consider the T-stub's economical aspects in comparison with other models under ambient and high temperatures.

This research is supported by the Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI) Fundamental Fund for fiscal year 2026.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization, visualization, supervision and funding acquisition: Thongchom C, Ghamari A; methodology, data curation and writing − original draft preparation: Ghamari A; software and formal analysis: Karimi I; validation and investigation: Thongchom C, Ghamari A, Rios AJ; resources and project administration: Thongchom C; writing − review and editing: Thongchom C, Rios AJ. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Tech University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Thongchom C, Ghamari A, Rios AJ, Karimi I. 2025. Assessment of the performance of a novel T-Stub-enhanced ConXL moment connection under fire. Emergency Management Science and Technology 5: e023 doi: 10.48130/emst-0025-0021

Assessment of the performance of a novel T-Stub-enhanced ConXL moment connection under fire

- Received: 20 August 2025

- Revised: 02 December 2025

- Accepted: 10 December 2025

- Published online: 29 December 2025

Abstract: Box columns are widely recognized for their satisfactory performance in structural applications; however, their complex fabrication, particularly with the use of continuity plates, remains a significant drawback. The ConXtech® ConXL™ (referred to as ConXL) moment connection addresses this limitation, offering advantages such as improved industrialization processes and construction quality. This study proposes an innovative enhancement to the ConXL connection by incorporating a T-stub for application with unfilled box columns. The enhanced connection is analyzed through parametric and numerical investigations, with a particular focus on its behavior under fire. The results indicate that all types of ConXL connections maintain stable hysteresis curves, even at elevated temperatures of up to 600 °C. These connections achieve rotations exceeding 0.04 radians without forming plastic hinges, confirming their suitability for use in special moment frames. Additionally, the incorporation of the T-stub significantly enhances the performance of the ConXL connection, especially under high-temperature conditions. Comparative analysis revealed that the T-stub increased the connections' ultimate strength by factors of 1.08, 1.11, 1.10, and 1.87 at temperatures of 20, 200, 400, and 600 °C, respectively. Predictive equations for the behavior of the enhanced system are proposed, offering a practical tool for structural design and analysis practitioners.

-

Key words:

- ConXL /

- Post-Fire /

- Ductility /

- Stiffness /

- Ultimate Strength