-

In eukaryotes, the entire genome must be faithfully duplicated and propagated in each cell division cycle[1−3]. Defects in DNA replication can cause genomic mutations and chromosomal aberrations and lead to genome instability. Inherited mutations in key replication genes have also been linked to a range of genetic conditions characterized by developmental abnormalities and reduced organismal growth[2,4,5].

DNA replication is a highly regulated process, which begins with the loading of ORCs (Origin recognition complex) at replication origins. Afterwards, CDT1 (Chromatin licensing and DNA replication factor 1), CDC6 (Cell division control protein 6), MCM2-7 (Minichromosome maintenance 2-7), CDC45 (Cell division control protein 45), GINS (Go, ichi, ni, and san), Treslin (TOPBP1-interacting replication-stimulating protein), and RECQL4 (ATP-dependent DNA helicase Q4) are sequentially recruited[1,6,7]. Upon the phosphorylation of key components, such as MCMs, by CDK (Cyclin-dependent kinase) and DDK (Dbf4-dependent kinase), the CMG (CDC45-MCM-GINS) helicase is activated to unwind DNA[1,6,8]. As DNA replication is initiated, additional factors, including RPA (Replication protein A), PCNA (Proliferating cell nuclear antigen), and DNA polymerases, are recruited, resulting in a large protein complex usually referred to as the replisome that drives replication fork progression[1,6].

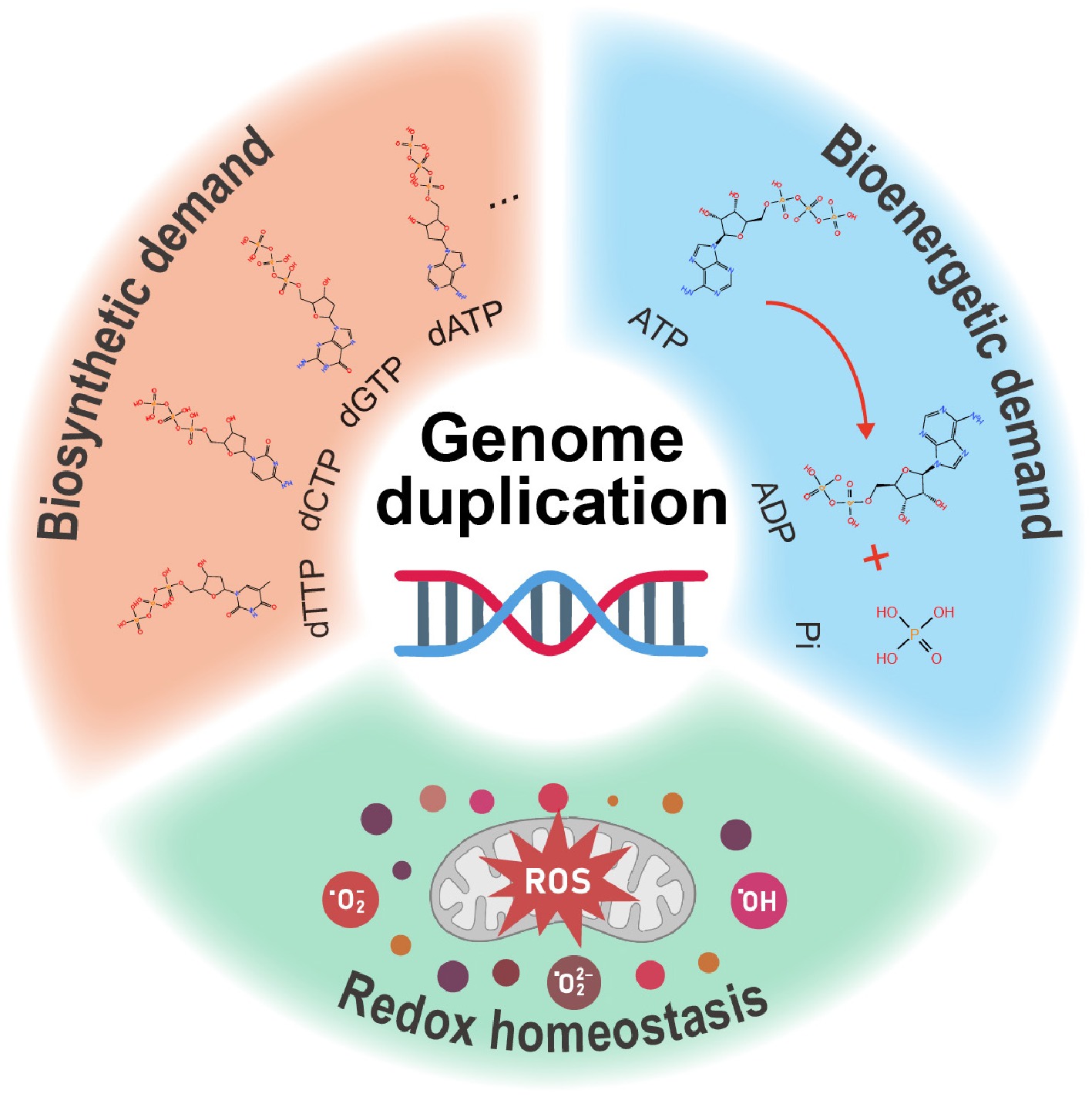

Genomic DNA is replicated in a dynamically changing environment and has to be coordinated with cellular metabolism (Fig. 1). Alterations in cell metabolism that impinge on biomass production, energy supply, and redox balance can often affect DNA replication[9,10]. For instance, nucleotide deficiency triggers ATR (Ataxia-telangiectasia-mutated and rad3-related) checkpoint activation, which in turn maintains fork stability and constrains new origin firing[7]. More recent studies revealed that metabolic intermediates and enzymes could regulate DNA replication in a more direct manner[11,12]. Here, we review connections of DNA replication with cellular metabolism and discuss recent insights into the metabolic control of DNA replication, with a focus on mechanisms directly regulating replication fork function and stability.

Figure 1.

DNA replication is coordinated with cell metabolism. (1) Biosynthetic demand: the biosynthesis of macromolecules is important for DNA replication. In particular, dNTP, including dTTP, dCTP, dGTP, and dATP, which serve as basic building blocks, are much in demand; (2) Bioenergetic demand: energy supply is also indispensable for DNA replication. For instance, changes in ATP level can affect DNA replication; (3) Redox homeostasis: hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hydroxyl radical (·OH), and superoxide anion (·O2−) that are the main resources of ROS can influence DNA replication in different manners.

-

The biosynthesis of macromolecules is fundamentally important for almost every biological process and molecular event[13−15]. As basic building blocks of DNA architecture, dNTP (Deoxynucleotide triphosphate) is in high demand during genome duplication[16,17]. As one of the best characterized conditions that compromise DNA replication and genome stability, depletion of the intracellular dNTP pool by HU (Hydroxyurea) that inhibits RNR (Ribonucleotide reductase) leads to the uncoupling between replicative helicase MCM2-7 and DNA polymerases[7,18,19]. As a consequence, ssDNA (Single-stranded DNA) coated by RPA is exposed, activating the ATR signaling cascade, the so-called replication checkpoint[2,20]. Once ATR is activated, it can directly phosphorylate key replication factors, such as RPA2 (Ser4/Ser8, Thr21 or Ser33), to protect fork stability[18,20]. In parallel, ATR catalyzes the phosphorylation of CHK1 (Checkpoint kinase 1), a master kinase that can phosphorylate and activate multiple factors required for replication initiation and elongation[21]. For example, CHK1 phosphorylates CDC25 (Cell division control protein 25) and WEE1 (Wee1-like protein kinase) to repress CDK1/2 activity and limit origin activation and fork progression[18,22,23].

Excessive dNTP can also be harmful to DNA replication. Extravagant dNTP in S. cerevisiae impaired replication origin firing by hindering CDC45 recruitment[24]. Also, excessive dNTP could increase genomic mutations through inducing Polδ and Polε replacement by TLS (Translesion DNA synthesis) polymerases, such as REV1, Polη, and Polζ[25−27]. In addition, an imbalanced dNTP supply might also be deleterious. For instance, an imbalanced dNTP pool caused by the overexpression of RNR mutant (rnr1-Y285A) in yeast resulted in a 13-fold higher mutation frequency than that in the wild type[17]. These findings demonstrated a critical role of macromolecule biosynthesis, particularly dNTP, in DNA replication (Fig. 1).

Bioenergetic demand

-

Energy production also seems indispensable for DNA replication[10,28,29]. Especially, changes in the energy currency, ATP, can influence DNA replication in multiple ways. In E. coli, DNA replication initiator DnaA (ORCs in mammals) was sensitive to cellular ATP level. Depletion of ATP led to DnaA degradation as well as a reduction in replication efficiency[29]. In eukaryotic cells, increased ATP levels accelerated DNA replication and promoted S phase progression[10,30]. A more recent work showed that ATP-binding to CDC7 (Cell division cycle 7-related protein kinase), the catalytic subunit of DDK, could unleash its activity to promote CDC45 recruitment and MCM2 S53 phosphorylation for replication initiation[3]. Other than CDC7, many key replication regulators, such as ORCs, CDC6, MCMs, and Lig1 (DNA ligase 1) are also ATP-dependent[30−33]. For instance, there is an ATP-binding domain at the interface between each pair of MCM subunits of the MCM heterohexamer. ATP-binding is not only important for the stabilization of MCM hexamer and double hexamers but also required for the release of CDT1[30].

In addition, AMPK (AMP-activated protein kinase), the master regulator of energy homeostasis[34], was also indicated to be important for DNA replication[34−36]. AMPK activation, induced by low glucose or metformin, impaired DNA replication and arrested cell cycle at the G1/S border[36]. In response to replication stress, such as HU or Aph (Aphidicolin), AMPK catalyzed the phosphorylation of Exo1 (Exonuclease 1) at S746 to prevent its recruitment to stalled replication forks, and thus avoid unscheduled resection[35]. Together, these findings highlight the dynamic coordination of DNA replication with changes in the bioenergetic state (Fig. 1).

Redox homeostasis

-

Accumulating evidence shows that redox homeostasis is important for DNA replication[11,13,37] (Fig. 1). In S. cerevisiae, an oscillation between oxidative and reductive state has been well characterized[38]. Adding H2O2 to boost ROS during the reductive phase of the yeast metabolic cycle, where DNA replication takes place, accelerated replication efficiency but increased genomic mutations[38]. In eukaryotes, ROS accumulation appeared to be associated with increases in transcription-replication conflicts, R-loop generation, and fork reversal[5]. For example, ROS-induced ATM (Ataxia telangiectasia mutated) oxidation at C2991 could mediate its dimerization and autophosphorylation[39], and in turn triggered MRE11 (Meiotic recombination 11)-dependent nascent DNA digestion at replication forks[37]. Intriguingly, reduction of mitochondrial ROS also jeopardized DNA replication[9]. Upon antioxidant MitoTEMPO treatment or PDC (Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex) depletion to block pyruvate production that directly supports the TCA (Tricarboxylic acid) cycle, and the ETC (Electron transport chain), mitochondrial ROS level was significantly decreased, resulting in decreased replication efficiency and reduced PCNA foci number[9]. Intracellular ROS can either function as a signaling molecule or trigger oxidative stress, depending on its level, that oscillates from nanomolar to micromolar, even under normal physiological conditions[40,41]. A threshold mechanism, which guarantees a proper amount of ROS acquired during DNA replication, might be able to reconcile the seemingly contradictory observations, but remains to be explored.

Moreover, CDK2 could also respond to changes in ROS during the S phase. Clearance of mitochondrial ROS by MitoTEMPO or mutating C177, the oxidation site in CDK2, compromised CDK2 activity and impaired DNA replication[9]. A more recent study revealed that fluctuations in ROS level could also be 'sensed' through an alternative mechanism. In brief, upon ROS accumulation, PRDX2 (Peroxiredoxin 2) disassociated from the replication fork and impaired TIMELESS-TIPIN binding, resulting in a significant slowdown in fork progression[11]. Despite these findings, connections between redox homeostasis and DNA replication, as well as more direct links beyond biomass production, energy supply, and redox balance, remain to be further investigated.

-

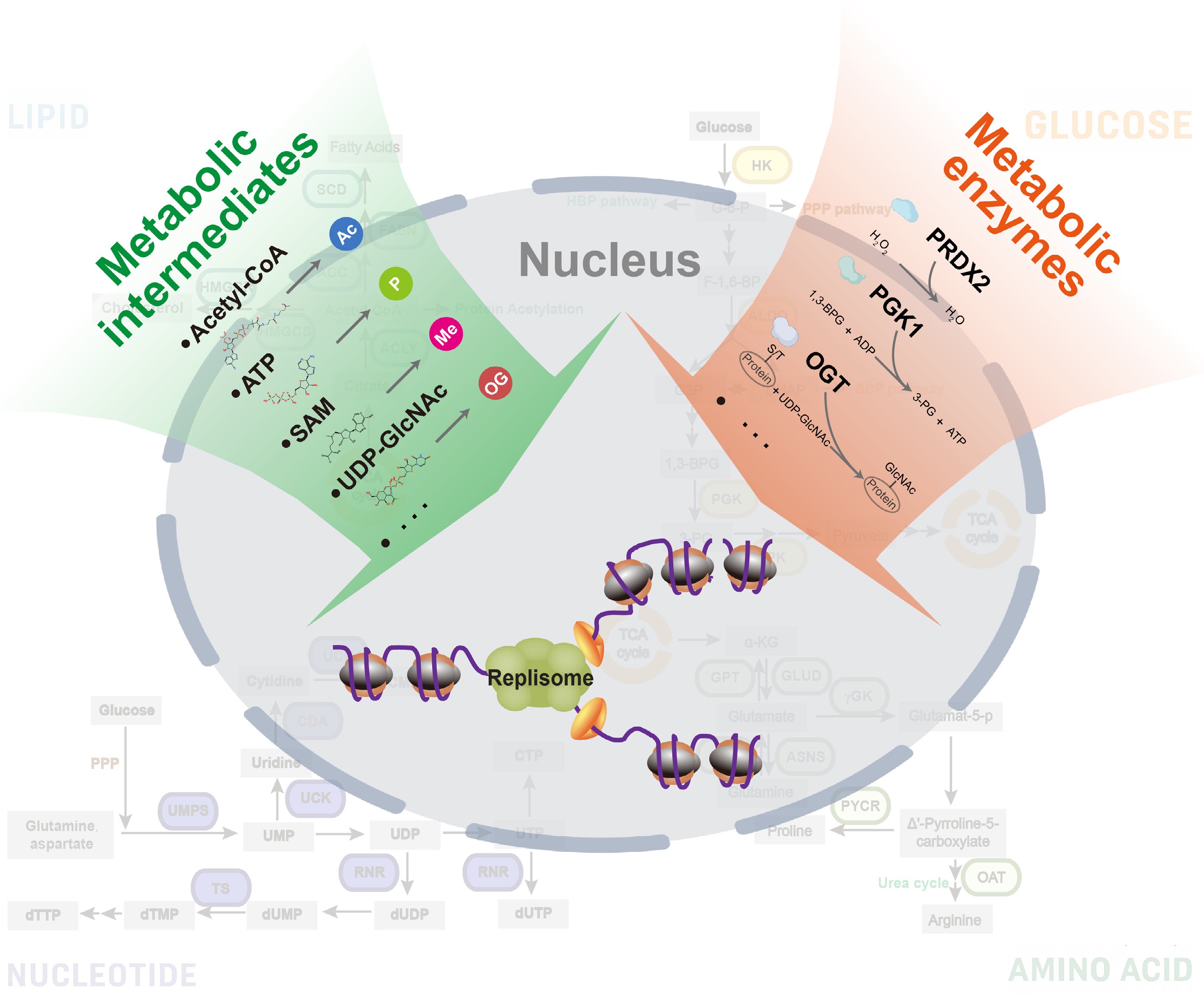

Metabolic intermediates are fundamentally important for almost every cellular process and activity[42−44]. In different situations, they may act as allosteric activators or repressors to manipulate protein functions[45]. Also, they could function as donor molecules and influence protein structure and function by supporting the establishment of distinct PTMs (Post-translational modifications), such as acetylation, phosphorylation, methylation, and O-GlcNAcylation (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Metabolic regulation of DNA replication. (1) Metabolic intermediates: small molecules, such as acetyl-CoA, ATP, SAM, and UDP-GlcNAc, function as donors and support the establishment of PTMs on key factors to regulate DNA replication; (2) Metabolic enzymes: classic enzymes that control metabolic reactions may enter the nucleus and regulate fork function/stability directly.

Acetylation (Acetyl-CoA)

-

Acetyl-CoA, which is usually produced via glucose and fatty acid metabolism, is the sole acetyl group donor for acetylation[14,46]. Notably, acetylation on both histones and non-histones has been shown to be important for DNA replication[47,48]. In yeast, acetylation at H3 K9/14 and H4 K5/8/12 near ARSs (Autonomously replicating sequences) appeared to be indispensable for DNA replication[49]. Mutating these lysines to arginines significantly impaired origin activation and S phase progression[49]. In HeLa cells, upregulation of H4 acetylation by histone acetyltransferase HBO1 (Histone acetyltransferase binding to ORC1) facilitated origin licensing, while artificial tethering of catalytically disabled HBO1 to origins dampened MCM2-7 loading[50]. In line with this observation, HBO1 in complex with scaffold protein BRPF3 (Bromodomain and PHD finger containing 3) promoted H3K14 acetylation and improved origin activation[51]. Moreover, acetylation of H3 at K56 by Rtt109 (p300 in mammals) also played a critical role in DNA replication, particularly for new histone deposition and nucleosome assembly[52,53].

Interestingly, acetylation of key components in the replisome is also at play during DNA replication[54,55]. Acetylation of MCM10 at multiple sites (K312 and K390 in the internal domain, K683/K745/K761/K768 in the C-terminal domain) by p300 facilitated its unloading from chromatin and thus negatively regulated origin activation and fork progression[54]. Moreover, acetylation of PCNA at K13/K14/K20/K77/K80 also appeared to be important. Mutating these sites (5KR) to abolish acetylation compromised PCNA binding on DNA, causing an impairment in DNA replication and hypersensitivity to UV[55]. Together, acetyl-CoA can directly regulate DNA replication by facilitating acetylation on histones and key components of the replication machinery.

Phosphorylation (ATP)

-

ATP is the donor molecule fueling phosphorylation on diverse proteins[56]. Extensive investigations have demonstrated that phosphorylation on replication factors is necessary for the control of DNA replication[6,57]. For instance, phosphorylation of MCM2 at S40, S53, and S108 by DDK is a prerequisite for its recruitment to chromatin[3]. MCM4 phosphorylation at S6 and T7 could promote its interaction with CDC45 to initiate DNA replication[58]. MCM10 phosphorylation at S66 and S630 respectively, enhanced its interaction with MCM2 and replisome stability[59,60]. Moreover, phosphorylation of GINS, precisely on sld2 and sld3 subunits, by S-CDK (CDK2 in mammals) improved the assembly of the functional CMG helicase during DNA replication[61,62].

Besides, phosphorylation is also involved in cellular responses to replication stress[7,19]. Upon replication stress, ATR, the master kinase governing the DNA replication checkpoint, was activated and phosphorylated at T1989[63]. Subsequently, a chain of events driven by the phosphorylation of different downstream effectors, including CHK1 (S317 and S345), CDC25A (S124 and S76), RPA2 (Ser33, Ser4/Ser8 and Thr21), and H2AX (Ser139), was launched to maintain fork stability and genome integrity[7,20,63,64]. Collectively, phosphorylation is not only important for unperturbed DNA replication, but also plays a critical role in the control of replication stress response.

Methylation (SAM)

-

Methylation of DNA, RNA, and proteins is widely involved in the regulation of diverse cellular processes and molecular events[65−68]. Its donor molecule is SAM (S-adenosylmethionine), synthesized from methionine and ATP by MAT (Methionine-adenosyltransferase)[69]. During DNA replication, both DNA methylation and histone/non-histone methylation appear to be indispensable[70−74]. Genome-wide analyses, such as Repli-seq and Hi-C (High-throughput/resolution chromosome conformation capture), demonstrated that the absence of DNA methylation in human cells disrupted replication timing and altered 3D genome organization[75]. In mESCs (Mouse embryonic stem cells), DNA hypomethylation due to DNMT1 (DNA methyltransferase 1), DNMT3A (DNA methyltransferase 3A), and DNMT3B (DNA methyltransferase 3B) triple deletion delayed replication timing in pericentromeric heterochromatic domains[76]. Furthermore, knocking down DNMT1 in human cells triggered ATR-CHK1 activation and arrested S phase progression[71].

In addition to DNA methylation, both histone and non-histone methylation are important for DNA replication. For example, H3K36me improved CDC45 recruitment to promote replication initiation in S. cerevisiae[72] . In human cells, H4K20me1 and H4K20me2 are crucial for ORCs recruitment, aiding origin licensing and activation[73,77]. Besides, methylation of PCNA at K110 promoted its trimerization and, in turn, stabilized polδ association at the replication fork during DNA replication[74]. Together, methylation is required for the control of DNA replication.

O-GlcNAcylation (UDP-GlcNAc)

-

UDP-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc), mainly produced via HBP (Hexosamine biosynthesis pathway), is the donor molecule of O-GlcNAc modification (Fig. 2), which is reversibly controlled by OGT (O-GlcNAc transferase) and OGA (O-GlcNAcase)[78−80]. Because the synthesis of UDP-GlcNAc is tightly associated with glucose, fatty acid, amino acid, and nucleotide metabolism, O-GlcNAcylation is widely recognized as a 'nutrient sensor'[78,79,81]. Over the past few decades, more than 5,000 proteins bearing O-GlcNAcylation have been characterized[79]. They were shown to be involved in the control of a growing list of biological processes, such as signaling transduction, gene transcription, metabolic rewiring, and cell cycle progression[79,80,82].

As for DNA replication, a panel of O-GlcNAcylated proteins has been shown to be critical (Table 1). For instance, H4S47 O-GlcNAcylation promoted the activation of the MCM complex and origin firing by facilitating DDK recruitment. Once H4S47 was mutated, the coordination between DNA replication and nutrient supply, especially glucose and glutamine, was disrupted[83]. This indicated that H4S47 O-GlcNAcylation might be a key linking genome duplication to the dynamically changing environment. Other than H4, H2A, H2B, and H3 could also carry O-GlcNAc modification[84−86], but their role, if any, in DNA replication is still unclear. In addition to histones, MCM2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 were also reported to bear O-GlcNAcylation[87]. Knockdown of OGT disturbed interactions between MCM subunits and impaired MCM association on chromatin[87]. A more recent study showed that RPA2 Ser4/Ser8, which are typically phosphorylated after DNA damage[88], could also be O-GlcNAcylated[89]. Upregulation of RPA2 O-GlcNAcylation by Thiamet-G, impaired CHK1 activation and S-G2 transition, suggesting an important role of RPA2 O-GlcNAcylation in DNA damage response[89] (Table 1). Unquestionably, more O-GlcNAcylated proteins and O-GlcNAcylation sites involved in the regulation of DNA replication and replication stress response will be discovered when technical breakthroughs in the detection of O-GlcNAcylation can be achieved in the future.

Table 1. O-GlcNAcylation on factors that are potentially involved in the control of DNA replication.

Protein Site(s) Function Ref. Replisome components MCM2-7 Unknown Promotes MCMs loading on chromatin [87] FEN1 S352 Disrupts FEN1 interaction with PCNA, causing replication defect and DNA damage [93] AND-1 S575, S893 Promotes HR to protect genome stability [94] Histones H4 S47 Directs DDK recruitment to promote replication origin activation [83] H2A S40 Associate with γH2AX to promote genome stability [84] DNA damage repair factors PLK1 T291 Required for proper chromosome segregation and thus important for the maintenance of genome stability [98] H2AX S139 Antagonizes phosphorylation of S139 on H2AX to restrain DNA damage signaling and protect genome integrity [90] Polη T457 Promotes TLS synthesis [99] MRE11 Unknown Promotes MRE11 recruitment on chromatin to protect genome integrity [100] RPA2 S4, S8 Antagonizes RPA2 S4/8 phosphorylation and impairs Chk1 activation [89] MCM, minichromosome maintenance; FEN1, flap endonuclease 1; AND-1, acidic nucleoplasmic DNA-binding protein 1; PLK1, polo-like kinase 1; Polη, DNA polymerase eta; MRE11, meiotic recombination 11; RPA, replication protein A; HR, homologous recombination. Together, metabolic intermediates can serve as messengers coupling cell metabolism to DNA replication. Meanwhile, changes in the complex metabolic network reflected by alterations in variable PTMs may also profoundly impact both the epigenomic landscape and genomic function.

-

In recent years, mounting evidence has shown that metabolic enzymes possess previously unappreciated functions beyond the regulation of cell metabolism[15,90,91]. These functions, including transcriptional regulation, DNA damage repair, and signaling transduction, are frequently referred to as the 'moonlighting' functions[91,92]. Notably, their emerging roles in DNA replication have attracted increasing attention (Table 2).

Table 2. Metabolic enzymes potentially involved in the regulation of DNA replication.

Metabolic enzyme Function in DNA replication Ref. PGK1 Binds to CDC7 and convert ADP to ATP for origin activation [12] PRDX2 Associates with TIMELESS-TIPIN at the replication fork to adjust fork speed [11] OGT Enriches on chromatin in S phase and modifies H4 S47 to promote origin activation [83] ACO2 Knockdown of ACO2 compromises DNA synthesis [94] HK2 Knockdown of HK2 compromises DNA synthesis [94] GAPDH Knockdown of GAPDH compromises DNA synthesis [94] PDC Localizes in the nucleus and regulates S phase entry [97] H6PD Knockdown of H6PD impairs DNA synthesis [93] RPE Knockdown of RPE impairs DNA synthesis [93] PRPS1 Knockdown of PRPS1 impairs DNA synthesis [93] ACLY Regulates nuclear acetyl-CoA concentration thereby regulating MCM2-7 and CDC45 transcription [101] FH Knockout of FH in S. cerevisiae leads to be sensitive to HU [95] IDH1/2 IDH1/2 mutants regulate DNA replication by contributing heterochromatin formation [96] PGK1, phosphoglycerate kinase 1; PRDX2, peroxiredoxin 2; OGT, O-GlcNAc transferase; ACO2, aconitate hydratase 2; HK2, hexokinase 2; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; PDC, pyruvate dehydrogenase complex; H6PD, hexose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; RPE, ribulose 5-phosphate epimerase; PRPS1, ribose-phosphate pyrophosphokinase 1; ACLY, ATP-citrate lyase; FH, fumarate hydratase; IDH, isocitrate dehydrogenase. Unbiased siRNA screen of metabolic enzymes from the pentose phosphate pathway demonstrated that downregulation of H6PD (Hexose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase), RPE (Ribulose 5-phosphate epimerase), or PRPS1 (Ribose-phosphate pyrophosphokinase 1) impaired DNA synthesis[93] (Table 2). Downregulation of metabolic enzymes that are responsible for glycolysis and TCA cycle, such as HK2 (Hexokinase 2), GAPDH (Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase), ACO2 (Aconitate hydratase 2), and FH (Fumarate hydratase), could also hinder DNA synthesis in human cells[94] (Table 2). In line with these observations, Fum1 (Fumarate hydratase in mammals)-dependent generation of fumarate competed with α-KG (α-ketoglutarate) to inhibit histone demethylase Jhd2 in S. cerevisiae. This stimulated H3K4me2/me3 accumulation, and eventually helped cells survive replication stress[95]. IDH1/2, which are also key enzymes controlling the TCA cycle, could also regulate DNA replication[96]. 2HG (2-hydroxyglutarate), generated by the oncogenic IDH1/2 mutant, inhibited dioxygenases to increase H3K9me2, a marker of facultative heterochromatin. As a consequence, replication fork progression in heterochromatic regions was slowed down, causing replication stress and DNA double-strand break[96]. Moreover, PDC could enter the nucleus and regulate S phase entry[97]. GAPDH and LDH (Lactate dehydrogenase) participated in the regulation of S phase-specific H2B transcription in human cells, and linked H2B expression to NAD+/NADH redox status[98−100]. In addition, key enzymes in fatty acid metabolism were also indicated to be involved in the regulation of DNA replication. For instance, mutation of Y542 and Y652 in ACLY (ATP-citrate synthase) impaired its catalytic activity in human cells, causing reduced acetyl-CoA supply and compromised expression of MCM2-7 and CDC45, which both are essential components of the replication machinery[101] (Table 2).

Evidence indicating a more direct connection between metabolic enzyme and DNA replication has already been revealed in earlier investigations[11,12,102]. PDH (Pyruvate dehydrogenase) was found to be associated with OriC, the sole replication origin in B. subtilis, and interacted with DnaG (DNA primase)[103−105]. Depending on their concentrations in the reaction systems in vitro, purified LDH, GAPDH, and PGK1 (Phosphoglycerate kinase 1) could either stimulate or repress the activity of Polα, Polε, and Polδ[106,107]. More recently, PGK1 was demonstrated to modulate replication initiation, precisely origin activation, by converting ADP to ATP. It alleviated ADP-dependent inhibition of CDC7, the catalytic subunit of DDK, and unleashed its activity to phosphorylate MCM2 for origin activation[12] (Fig. 2, Table 2). The presence of PRDX2, a member of the peroxiredoxin family that controls ROS homeostasis[108,109], at the replication fork further substantiated the important role of metabolic enzyme(s) in DNA replication[11] (Fig. 2, Table 2). In brief, PRDX2 formed a decamer associating with TIMELESS-TIPIN complex at the replication fork. Due to the accumulation of intracellular ROS, PRDX2 was released from the replication fork and caused TIMELESS-TIPIN dissociation, resulting in a significant slowdown in replication fork progression. When PRDX2 was depleted, unprotected replication forks became more vulnerable to ROS stimuli, leading to DNA damage accumulation and therefore genome instability[11].

Together, these findings depict important functions of metabolic enzymes for the control of DNA replication (Fig. 2). Compared to classic replication regulators, this additional layer of regulation by metabolic enzymes may, to some extent, have the privilege of orchestrating genomic DNA replication in a dynamically changing metabolic context.

-

Despite extensive investigations on metabolic reprogramming associated with biological and pathological processes, how DNA replication is interconnected with cell metabolism still remains elusive. In recent years, exciting findings on previously unappreciated functions of metabolic enzymes and PTMs in DNA replication have shed some light on the connection of DNA replication to its extracellular environment. Undeniably, technical limitations, such as the detection of highly dynamic metabolites in specific compartments in cells, are still the major barriers hindering advances in this field. Emerging revolutionary approaches, such as genetically encoded fluorescent biosensors, obviously hold great promise for overcoming these hurdles. In particular, powerful tools like FiLa for monitoring lactate in real time with spatial distribution, and SoNar/Frex for tracking subcellular NAD+/NADH ratio dynamics, will help us understand the metabolic control of DNA replication[110−112].

Metabolic reprogramming and uncontrolled DNA replication are hallmarks of cancer and are intertwined with each other in many pathological situations. In patients with ADA (Adenosine deaminase) deficiency autosomal recessive disorder of purine metabolism, ADA mutations caused abnormal accumulation of dATP (Deoxyadenosine triphosphate) in lymphocytes[113−115]. An earlier study showing disrupted balance among the four types of dNTP and compromised DNA synthesis resulting from dATP upregulation indicates a strong connection between metabolic changes and DNA replication in this specific disorder[114]. Moreover, ALCL (ALK-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma) and NECs (Neuroendocrine carcinomas) are characterized with upregulated NAMPT (Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase), and acute NAD+ elevation, which can lead to pyrimidine depletion, purine accumulation, and eventually cause replication defects and genomic instability[116]. Targeting metabolic pathways and DNA replication is already proven to be effective for treating and preventing human diseases, such as cancer. Exploration of mechanism(s) linking DNA replication to cell metabolism can pave the way to develop integrative strategies for tackling human diseases, and may eventually achieve 'killing two birds with one stone'.

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 32470782 and 32070758 to YF). This work was also supported by the Shenzhen Medical Research Fund (B2402044 to YF), the Natural Science Foundation of Jilin province (20250102279JC to YF), the Research and Innovation Improvement Project for PhD Students (JJKH20250328BS to YF), Higher Education Teaching Reform Project of Jilin province (JJKH20240138YJG to YF), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2024135134006 to YF). We would like to thank Sung-Bau Lee (College of Pharmacy, Taipei Medical University), Jialin Liu (National Center for Protein Sciences, Beijing Institute of Lifeomics), and Yang Jiao (School of Physical Education, Northeast Normal University) for their advice.

-

An ethics statement is not applicable because this study is based exclusively on published literature and publicly available data.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conception and design: Feng Y, Dong K, and Pei J; draft manuscript preparation: Feng Y, Dong K, and Pei J; review and/or editing of the manuscript: Liu J, Li Y, and Wang Y. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Kejian Dong, Jiayao Pei

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Dong K, Pei J, Liu J, Li Y, Wang Y, et al. 2025. Metabolic control of DNA replication: beyond biosynthetic and bioenergetic needs. Epigenetics Insights 18: e016 doi: 10.48130/epi-0025-0015

Metabolic control of DNA replication: beyond biosynthetic and bioenergetic needs

- Received: 29 July 2025

- Revised: 09 November 2025

- Accepted: 16 December 2025

- Published online: 31 December 2025

Abstract: Both genome duplication and cell metabolism are fundamentally important for organismal growth and homeostasis. Defects in DNA replication and metabolic programming are often associated with various human diseases, such as cancer. In addition to links between these two cellular activities revealed in early studies, remarkable advances in recent years have extended our understanding of how DNA replication is coordinated with metabolic changes in cells, especially in biomass production, energy supply, and redox balance. Novel functions of metabolic intermediates and enzymes in the control of DNA replication have attracted considerable attention. Here, we review the current knowledge of metabolic cues involved in DNA replication and discuss the underlying mechanisms, with a focus on direct impact on replication fork function and stability.