-

Wheat is among the most extensively cultivated and widely consumed crops globally, valued for its high nutritional content and versatility in producing a range of processed foods, including bread, noodles, and pastries. A significant characteristic of wheat flour is its ability to create a viscoelastic dough, essential for processing the diverse textures of wheat-based products like bread and pasta[1]. This property is primarily due to gluten, the principal storage protein in wheat. Gluten consists of gliadins and glutenins, which together determine the dough's elasticity, cohesiveness, and extensibility[2,3].

Cross-linking reactions that form bonds within and between gluten molecules heavily determine gluten's functionality. These reactions enhance the stability and mechanical properties of the gluten network, which are critical for dough elasticity, gas retention, and overall bread quality[4]. Although mechanical mixing and thermal treatments can induce bond formation, chemical redox agents and enzymes enhance the efficiency of gluten cross-linking. Traditionally, exogenous oxidizing agents, such as potassium bromate, iodate, and azodicarbonamide, have been used to strengthen disulfide bond formation and dough performance[5,6]. However, food safety and health concerns have prompted the food industry to pursue more natural alternatives. To meet consumer demands for safer, cleaner-label products, endogenous enzymes found in wheat have emerged as promising substitutes for exogenous additives[7]. Enzymes such as sulfhydryl oxidase (SOX), protein disulfide isomerase (PDI), ascorbate oxidase (AAO), and dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR) catalyze thiol-disulfide exchange and redox reactions, facilitating the formation of disulfide and dityrosine bonds in gluten proteins. These enzymes enhance the gluten network, improve dough rheological properties, and boost bread-making quality without adding foreign substances[3,8]. Unlike chemical agents, endogenous enzymes leverage wheat's inherent systems, minimizing contamination risks, offering a more natural method to enhance flour functionality. In recent years, artificial intelligence techniques have enabled accurate prediction of enzyme structures through tools such as AlphaFold2[9], and generative models (e.g., Chroma) have demonstrated the ability to design functional enzyme proteins from scratch[10]. These breakthroughs provide a new paradigm for rational modification of endogenous enzymes in wheat: by fusing multi-omics data to train prediction models, key sites affecting enzyme activity can be accurately identified; and sequence generation based on reinforcement learning is expected to break through the limitations of traditional directed evolution to design wheat enzyme variants adapted to extreme processing conditions[11].

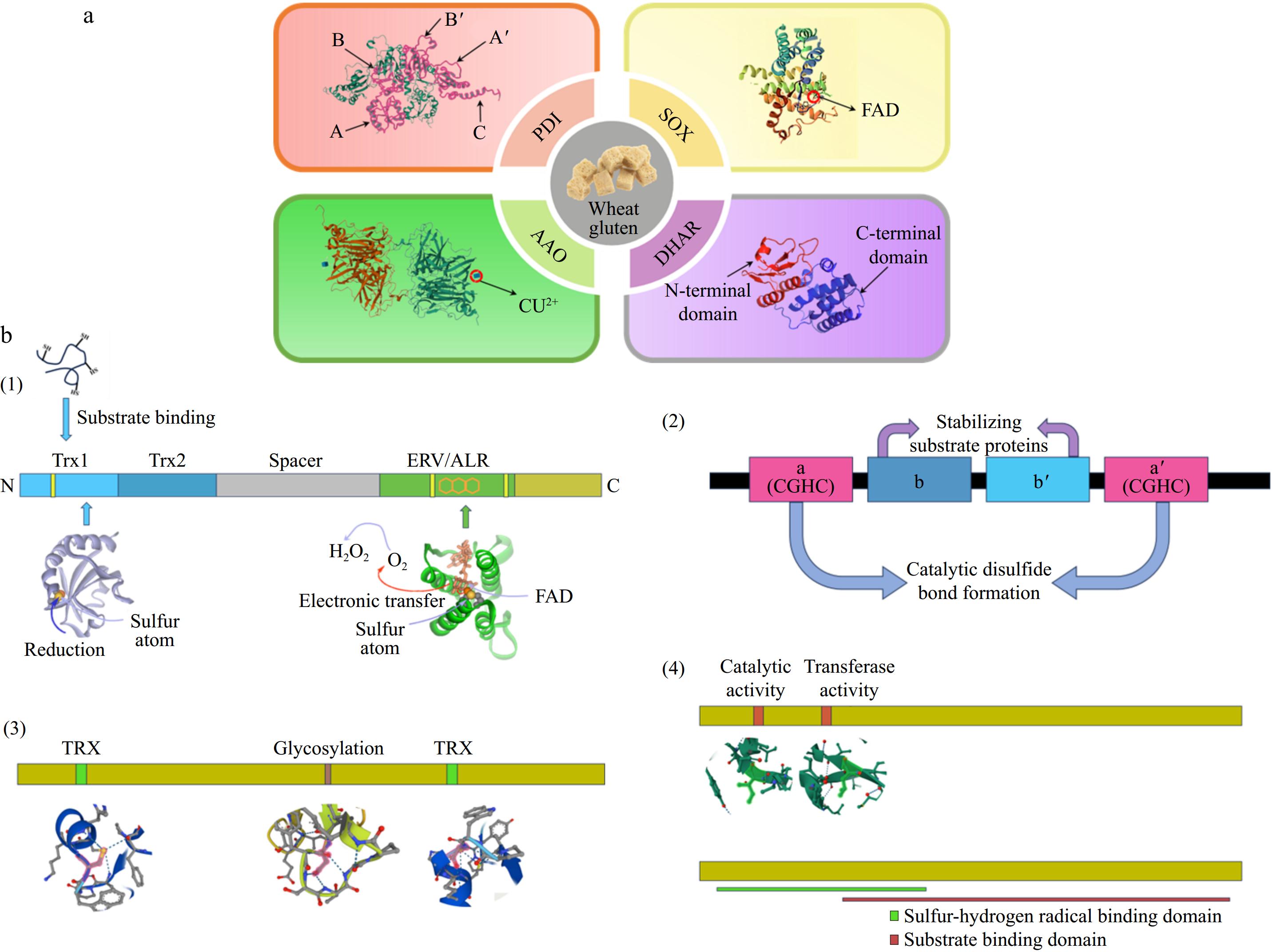

The degree of gluten cross-linking is regulated by endogenous enzymes that catalyze redox reactions or thiol-disulfide exchanges, enhancing gluten's gelation and elasticity[3,8]. As shown in Table 1, there are four main methods of gluten protein cross-linking: (1) acting on amino acids (e.g., cysteine and tyrosine) via sulfhydryl oxidases; (2) catalyzing disulfide bond networks for correct protein folding using protein disulfide isomerase; (3) indirectly facilitating cross-linking by altering oxidation states with ascorbate oxidase; and (4) maintaining redox balance through dehydroascorbate reductase. Previous reviews on the role of exogenous oxidases in the modification of gluten extensively discussed the application of endogenous vs exogenous enzymes[7]. In contrast, the present review uniquely focuses on wheat endogenous enzymes, dissecting their domain-specific catalytic mechanisms and their intrinsic role in regulating gluten cross-linking. The natural advantages of wheat's enzyme system are emphasized to provide theoretical support for 'clean label' food processing. Figure 1 illustrates detailed descriptions of SOX, PDI, AAO, and DHAR, emphasizing their structures, mechanisms, and effects on gluten modification and bread quality, thereby providing a theoretical basis for enhancing the quality of wheat-based products.

Table 1. Summary of various endogenous oxidative enzymes acting in gluten.

Proteases (EC:) Mode of action/cross-linking mechanism Cofactor/metal dependence Substrate Reactive sites in gluten Application of enzymatic

cross-linkingRef. Sulfhydryl oxidase

EC:1.8.3.3Catalyzes the oxidation of a sulfhydryl group (-SH) to a disulfide bond (-S-S-) with the simultaneous generation of hydrogen peroxide. Usually contains FAD or metals such as iron or copper. Small molecule thiols such as glutathione, cysteine, or cysteine residues in proteins. Cysteine residue Promotes protein cross-linking. [12] Protein disulfide

isomerase EC:5.3.4.1Catalyzes the exchange reaction of sulfhydryl groups and disulfide bonds in proteins. − Disulfide bonds in proteins. Intermolecular disulfide bonds Affects dough quality. [13] Ascorbate oxidase

EC:1.10.3.3Oxidizes ascorbic acid, forming new disulfide bonds. Copper ion Ascorbic acid. − Improve dough properties. [14] Dehydroascorbic acid reductase

EC:1.8.5.1Reduction of dehydroascorbic acid. Formation of new disulfide bonds NAD(P)H Dehydroascorbic acid. − Reduction of oxidative stress. [15] Tyrosinase

EC:1.14.18.1Catalyzes hydroxylation and oxidation reactions of phenolic compounds. Two copper atoms. Tyrosine and L-dopa. Tyrosine residues. Catalyze protein cross-linking reactions. [16,17] Laccase

EC:1.10.3.2Oxidizes phenolic compounds to produce reactive phenol radicals. Four copper atoms. Phenolic compounds and ferulic acid etc. Tyrosine and cysteine residues Catalyze protein cross-linking reactions. [17] Lipoxygenase

EC:1.13.11.12Oxidized fats and oils produce hydroperoxides. − Fats and oils with a pentadiene 1,4 double bond. − Enhances gluten strength. [18,19] Lipase

EC:3.1.3.3Hydrolysis of fatty acid ester bonds. − Lipids. − Catalyze protein cross-linking reactions. [20,21] Peroxidase

EC:1.11.1.7Catalyzes the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide and enhances gluten strength. Iron-containing hemoglobin protein. Hydrogen peroxide. Tyrosine Catalyze protein cross-linking reactions. [22] Catalase

EC:1.11.1.6Decompose hydrogen peroxide. − Hydrogen peroxide. − Baking, dough strengthening. [23] NAD(P)H-dependent dehydrogenase Oxidized substrates that initiate free radical chain reactions between gluten. Dependent on NAD(P)(H). Includes alcohols, aldehydes, alpha-hydroxy, and beta-hydroxy carboxylic acids. − Participation in redox reactions. [5,24]

Figure 1.

(a) Structures of the four endogenous enzymes SOX (sulfhydryl oxidase), PDI (protein disulfide bond isomerase), AAO (ascorbate oxidase), and DHAR (dehydroascorbate reductase) that function in gluten. (b) Schematic structures of the four endogenous enzymes. (1) Homology models for the Trx1 and Erv/ALR structural domains were constructed based on the structure of QSOX using the crystal structures of the yeast PDI structural domain and yeast Erv2p, respectively. (2) Schematic structure of PDI, Catalytic thioredoxin-like domains (a and a') are colored pink, and non-catalytic domains (b and b') are blue. (3) Schematic structure of AAO, including glycosylation site and disulfide bonding region, respectively. (4) Schematic structure of DHAR, including the catalytic active site and the transferase active site, respectively.

-

Sulfhydryl oxidases (SOX) constitute a major class of enzymes that oxidize thiol-containing molecules using molecular oxygen as an electron acceptor, producing hydrogen peroxide. The hydrogen peroxide produced during the catalytic process can further improve the quality of wheat products.

Types and overview

-

SOX enzymes oxidize sulfhydryl groups to form disulfide bonds and produce hydrogen peroxide[25]. SOX is classified into four families based on structural features: the essential for respiration and viability (ERV)/augmenter of liver regeneration (ALR) family, the endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreductase (Ero) family, the quiescent sulfhydryl oxidase (QSOX) family, and the secretory fungal SOX family. Among these, the QSOX family and Ero enzymes are particularly relevant to wheat flour systems[26]. In wheat systems, SOX focuses primarily on cysteine residues within gluten, catalyzing both intramolecular and intermolecular disulfide bonds. This activity strengthens the gluten network, enabling the dough to retain gas during fermentation, thus achieving optimal bread volume and texture. The hydrogen peroxide produced by SOX facilitates additional protein cross-linking through oxidative reactions, further contributing to dough stability[12]. However, the specific mechanism of action has not been fully elucidated.

Composition and structure

-

The ERV/ALR and secreted fungal SOX families can catalyze disulfide bond formation from sulfhydryl groups, though not reported in wheat gluten. These enzymes are typically dimers composed of multiple subunits, each housing a signal peptide, one or more thioredoxin (TRX) domains, an ERV1/ALR domain, and a transmembrane region[26]. As shown in Fig. 1b(1), the ERV1/ALR domain serves as the catalytic center, containing FAD and a redox-active CxxC site. The TRX domain allows efficient substrate binding and oxidation, aiding the folding of reduced peptides and proteins. The ERV1/ALR domain features a distinct FAD-binding module with a unique α-helix-rich structure[25]. QSOX enzyme completes the catalytic cycle through three structural domains in concert: (1) the N-terminal Trx structural domain (containing the CxxC active site) is responsible for capturing the substrate sulfhydryl group to form the enzyme-substrate complex ( Fig. 2a); (2) the central helical linkage region transfers electrons from the Trx structural domain to the C-terminal ERV/ALR structural domain; and (3) after accepting the electrons, the FAD cofactor in the ERV/ALR structural domain transfers the electrons to oxygen via a thioredoxin-like reaction at the C459/C462 site transfers electrons to oxygen, generating H2O2 and regenerating the oxidized state enzyme[27].

Figure 2.

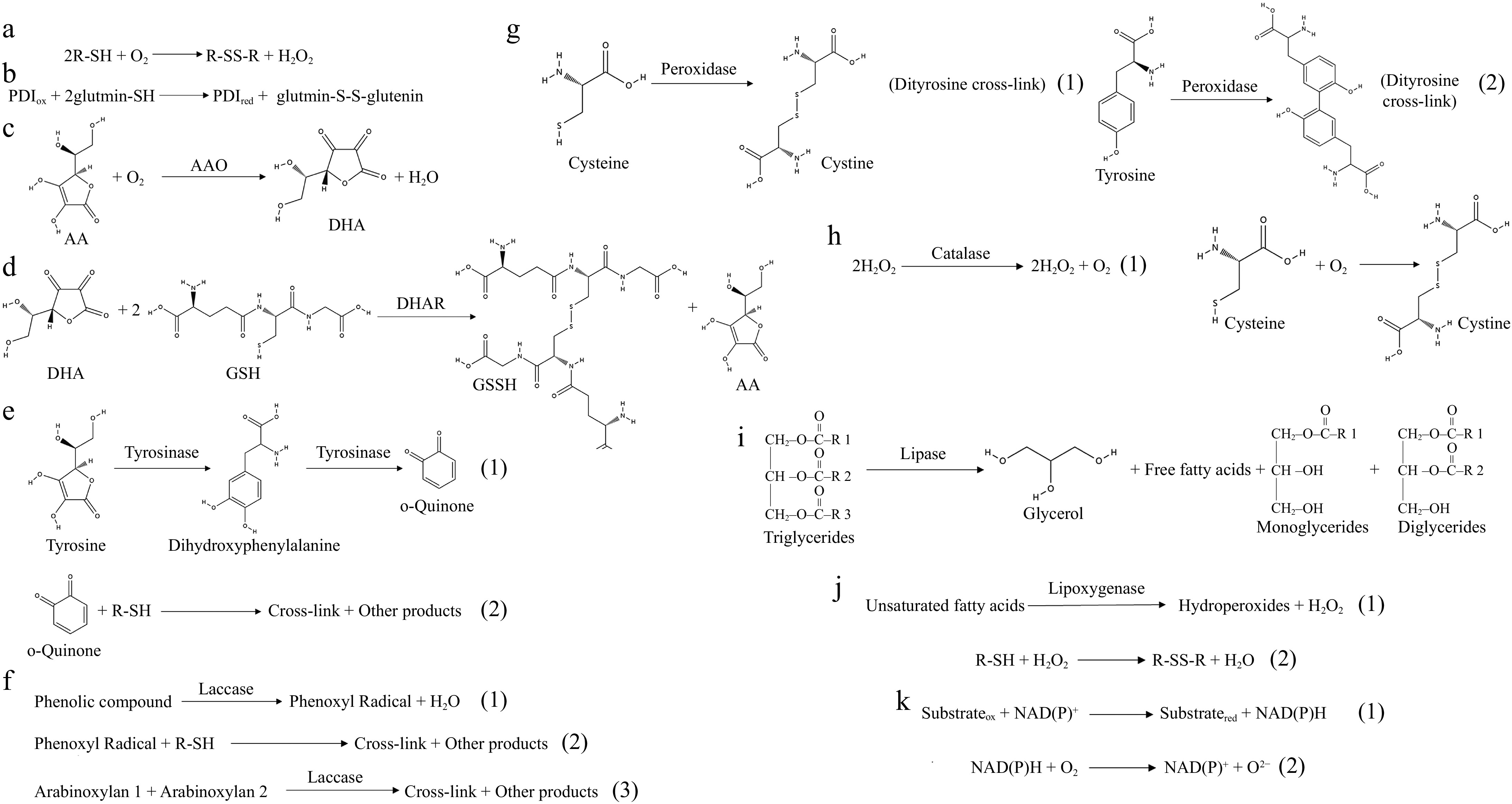

Enzymatic catalysts in dough chemistry. (a) Mode of action of sulfhydryl oxidase. (b) Mode of action of disulfide bond isomerase. (c) Mode of action of ascorbate oxidase. (d) Mode of action of dehydroascorbate. (e) Mode of action of tyrosinase. (1) Tyrosinase catalyzes the production of dihydroxyphenylalanine from tyrosine to continue the production of o-quinone. (2) O-quinone can interact nonenzymatically with thiol groups and amino groups in proteins, resulting in covalent cross-linking. (f) Mode of action of laccase. (1) Phenolic compounds are catalyzed by laccase to generate phenoxy radicals. (2) Phenoxy radicals can interact with thiol groups to form SH radicals for SH/SS intercalation. (3) Laccase can cross-link arabinoxylan in whole flour to form distearic acid, resulting in a powerful network. (g) Mode of action of peroxidase. (1) Peroxidase catalyzes the formation of disulfide bonds from cysteine. (2) Peroxidase catalyzes the formation of a double tyrosine cross-link from tyrosine. (h) Mode of action of catalase. (1) Catalase catalyzes the breakdown of hydrogen peroxide into water and oxygen. (2) Molecular oxygen promotes the formation of disulfide bonds between cysteine residues. (i) Mode of action of lipase. Lipase catalyzes the hydrolysis of triglycerides into free fatty acids and glycerol, thereby modifying the lipid architecture of dough. (j) Mode of action of lipoxygenase. (1) Lipoxygenase catalyzes the oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids to produce hydrogen peroxide and Hydroperoxides. (2) The H2O2 produced promotes the formation of disulfide bonds between thiol groups in gluten. (k) Mode of action of NAD(P)-dependent dehydrogenases. (1) Electrons are transferred from the substrate to NAD(P)+ to produce NAD(P)H. (2) NAD(P)H can react with molecular oxygen to produce superoxide radicals.

In yeast, a protein residing in the yeast endoplasmic reticulum (ER), Ero1[12]. EroI is a FAD-containing oxidoreductase that catalyzes the oxidation of PDI, thereby promoting the formation of disulfide bonds in proteins within the endoplasmic reticulum. The activity of Ero1 is influenced by its disulfides and interactions with PDI[28]. The Ero1 enzyme consists of a single-chain polypeptide containing a non-covalently bound FAD cofactor that accepts electrons from the internal active site and transfers them to an oxygen molecule, generating hydrogen peroxide[29]. Ero1's structure contains a catalytic domain and a regulatory domain linked by a flexible peptide. Additionally, Ero1 has a loop region with an outer active site that changes conformation during redox reactions[30].

Although the structure and catalytic mechanism of SOX have been extensively studied in bacterial and eukaryotic systems, less is known about wheat-specific SOX enzymes. Future studies should aim to characterize the structural domains and redox properties of wheat SOX to optimize its application in dough systems.

Mechanisms of action

-

SOX enzymes catalyze thiol oxidation through a multistep redox reaction. As shown in Fig. 2a, the key steps include: (1) Substrate binding: cysteine residues in gluten proteins engage with SOX's active site, oxidizing the thiol groups into disulfides; (2) Electron transfer: electrons from the substrate reduce the FAD cofactor to FADH2; and (3) Regeneration of active site: FADH2 gets reoxidized by molecular oxygen, restoring the active enzyme and generating hydrogen peroxide[12]. SOX is sometimes confused with thiol oxidase, which reduces molecular oxygen to water rather than hydrogen peroxide. The cross-linking mechanism of SOX is less studied than that of transglutaminase or tyrosinase. While SOX and transglutaminase both enhance gluten network formation, their mechanisms diverge significantly. In contrast, transglutaminase forms isopeptide bonds between glutamine and lysine residues in a calcium-dependent manner. Transglutaminase has been widely used in the food industry. Its cross-linking mechanism, optimal reaction conditions, and effects on texture have been systematically studied[7].

QSOX initially oxidizes a disulfide substrate via an oxidative disulfide bond in the N-terminal TRX domain, forming a mixed disulfide bond (Fig. 1b(1)). Subsequently, through a series of disulfide exchanges, reducing equivalents are transferred from the TRX domain to an FAD-binding module in the ERV1/ALR domain at the C-terminus. Finally, as shown in Fig. 3, the reduced FAD reacts with oxygen to generate hydroperoxides, restoring the oxidized state of the QSOX enzyme[25,31]. Transferring two reducing equivalents to the disulfide (C459/462) creates a cysteine thiol (C462) that interacts with the oxidized flavin[25]. Most flavoproteins exhibit these characteristics, where flavin cofactors undergo redox reactions with disulfides. The nucleophilic thiol can form a C-4a adduct with flavin, which eventually regenerates the proximal disulfide and yields reduced flavin. Finally, oxygen is reduced to hydrogen peroxide.

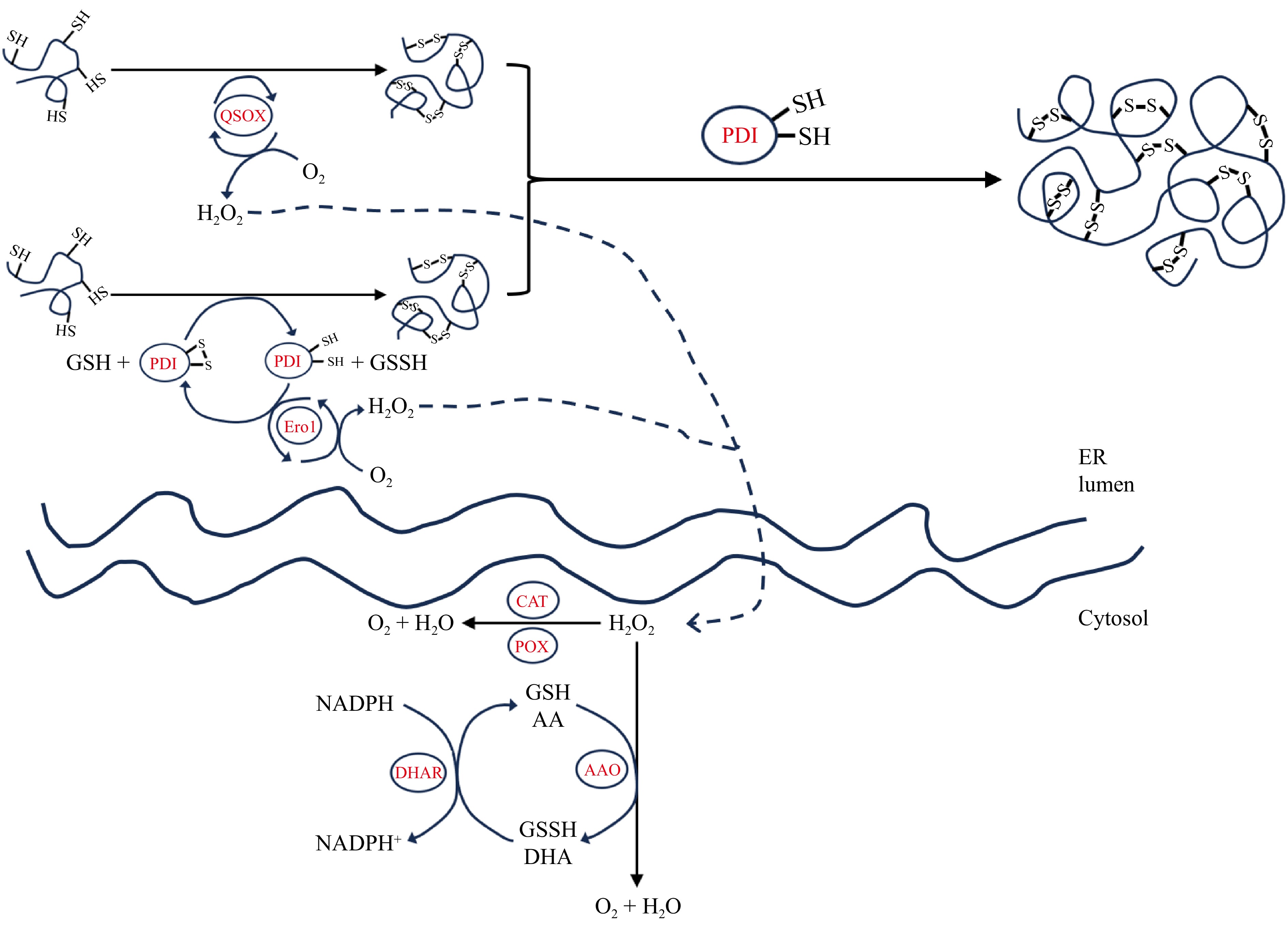

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the reaction mechanisms of different endogenous enzymes in the endoplasmic reticulum and cytoplasm.

In eukaryotes, the ER provides an oxidized environment with a lower glutathione (GSH)/glutathione disulfide (GSSG) ratio than in the cytoplasm, facilitating the oxidation of free sulfhydryl groups into disulfide bonds[32]. The crystal structure of yeast-derived Ero1, reported in 2004, significantly contributes to understanding its catalytic mechanism[33]. Ero1 enhances the oxidation of PDI's thiols via thiol-disulfide exchange with external site disulfides, which reoxidize into disulfide forms through internal disulfide sites[34]. As illustrated in Fig. 3, The reduced internal disulfide site donates electrons to molecular oxygen, aided by FAD, regenerating oxidized disulfides and producing hydrogen peroxide[35].

Current studies highlight SOX's role in protein folding, but researchers have inadequately addressed the detailed catalytic mechanisms and electron transfer pathways. Future research should focus on a deeper examination of SOX's catalytic mechanisms and pathways.

Functions and applications

-

In the pasta industry, SOX is used to enhance dough processing and bread baking quality[36]. In dairy products, SOX improves flavor by oxidizing the thiol groups exposed during ultra-high temperature sterilization and eliminating the burnt flavour of milk[37]. In the laundry sector, hydrogen peroxide produced by the SOX reaction acts as a decontaminant in household cleaners[38]. Nonetheless, SOX activity must be regulated to prevent over-oxidation, which can yield a rigid gluten network. Further research is warranted to clarify the physiological roles of secreted SOX in various organisms.

Protein disulfide isomerase

-

While SOX primarily catalyzes the formation of disulfide bonds, PDI complements this process by correcting misfolded proteins through thiol-disulfide exchange reactions. PDI is a multifunctional protein that catalyzes disulfide bond formation and isomerization and possesses molecular chaperone activities that regulate the aggregation of unfolded proteins.

Types and overview

-

PDI facilitates the formation, breakage, and reconfiguration of disulfide bonds in proteins, which is essential for proper protein folding[13]. It possesses two conserved active sites (CGHC) in the a and a′ domains and three non-catalytic domains (b, b′, and c)[39]. PDI is crucial in the ER of eukaryotic cells, participating in exocytosis and quality control of folded and cell surface proteins[40]. It catalyzes thiol/disulfide bond exchange reactions, including their formation, reduction, and isomerization. Numerous PDI homologs exist in mammalian ERs, including ERp57[41], ERp72[42], ERp44, PDIR[43], P5[44], ERdj5[45], PDIp[46], and ERp18[47]. These homologs differ in tissue distribution and substrate specificity, potentially performing distinct functions in the ER. In yeast, four PDI homologs exist in the ER: Eug1p, Mpd1p, Mpd2p, and Eps1p[48]. In E. coli, PDI functions are performed by DsbA (oxidase) and DsbC/G (reductase/isomerase)[49]. Although PDI's structure and mechanism of disulfide bond formation are well understood, its functional roles still warrant investigation.

Composition and structure

-

PDI is a 55 kDa protein composed of five structural domains: a, b, b', a', and c. The a and a' domains are catalytically active, the b and b' domains are inactive, and the c domain serves as an ER retention signal[39]. As shown in Fig. 1b(2), the structural domains of PDI are organized as follows: the a domain: Catalyzes oxidation and reduction reactions by forming disulfide bonds with substrate proteins. The b and b' domains: Stabilize substrates and prevent protein aggregation. The a' domain: Synergizes with the a domain in oxidative and isomerization functions. The c domain: facilitates ER localization and recycling.[50,51]. In summary, these features allow PDI to facilitate disulfide bond formation and stabilize gluten proteins, enhancing dough's viscoelastic properties.

Mechanisms of action

-

PDI comprises four thioredoxin domains arranged in an a-b-b'-a' order. The N-terminal a and C-terminal a' domains possess conserved CGHC motifs that cycle between oxidized and reduced forms[52]. As shown in Fig. 2b, PDI's oxidoreductase activity forms and reduces disulfide bonds in proteins while modifying its active site[53]. This activity hinges on the high reactivity of active site disulfides. PDI's isomerization activity converts incorrect disulfides into correct ones, often requiring a reduced state and cooperation between the a or a domains and the b domain, and as shown in Fig. 3, PDI conducts thiol-disulfide exchange through three mechanisms: oxidation, reduction, and isomerization. These reactions ensure correct folding and cross-linking of gluten proteins, impacting dough strength and elasticity.

Functions and applications

-

The non-catalytic b and b' domains, despite lacking active sites, enhance substrate binding through their hydrophobic surfaces. This structure allows PDI to conduct thiol-disulfide exchange reactions[53,54]. PDI recognizes and binds unfolded or misfolded proteins, promoting correct disulfide bond formation through thiol-disulfide exchange reactions[55]. It is integral to various enzyme complexes and regulates cellular responses across extracellular, cytoplasmic, and nuclear regions[13]. Overall, PDI's physiological functions are crucial for cellular processes, demonstrating its significance in organisms. Furthermore, PDI acts as a molecular chaperone, binding various peptides with low specificity, contributing to protein folding and stability[56].

Ascorbate oxidase

-

A ascorbate oxidase (AAO) converts ascorbic acid (AA) into free radicals and dehydroascorbic acid (DHA) while reducing molecular oxygen to water, avoiding the production of harmful reactive oxygen intermediates. DHA can be reverted to AA by sulfhydryl groups, which undergo oxidation into disulfide bonds during this process.

Types and overview

-

AAO catalyzes the oxidation of ascorbic acid to DHA, helping maintain cellular redox balance[57]. Primarily found in higher plants, especially Cucurbitaceae species like cucumber, pumpkin, and zucchini. AAO comprises three structural domains, each housing a copper center: type 1, type 2, and type 3. These centers facilitate electron transfer during the catalytic process[14]. Each AAO subunit consists of three structural domains with β-barrel configurations akin to small blue copper proteins, differing in segment length and connections. The catalytic mechanism involves two main steps: (1) reduction of AAO: electrons from ascorbic acid are transferred to type 1 copper, yielding DHA and reduced AAO. (2) Reoxidation of AAO: electrons are transferred from reduced AAO through type 2 and type 3 copper to oxygen, restoring AAO's active state and reducing oxygen to water[14]. However, the distribution and types of AAO across species are not well-detailed, warranting further studies to explore the forms and functional differences of AAO in various organisms.

Composition and structure

-

The crystallographic structure of zucchini AAO shows it exists as a dimer, each consisting of eight copper ions: three type 1, one type 2, and four type 3[14]. Figure 1b(3) illustrates the schematic structure of AAO, type 1 copper resides in the third structural domain, coordinated by two histidines, a cysteine, and a methionine, contributing to electron transfer. Type 2/3 copper is located between the first and third structural domains, coordinated by eight histidines, and plays a role in oxygen reduction[14]. Type 1 copper accepts electrons from substrates (e.g., ascorbic acid) and transfers them to type 3 copper, which can accept two electrons and bind molecular oxygen to create water[58]. Thus, type 1 and type 3 copper centers are critical for the catalytic mechanics of blue oxidases, handling substrate oxidation and oxygen reduction. The role of type 2 copper is to mediate electron movement between type 1 and type 3 coppers, influencing the enzyme's activity and affinity[59]. In wheat systems, AAO activity enhances gluten cross-linking by generating DHA, which interacts with sulfhydryl groups in gluten proteins, forming additional disulfide bonds that strengthen the gluten network.

Mechanisms of action

-

As an antioxidant, AA scavenges free radicals and produces ascorbate free radicals (AFR). Glutathione reduces the AFR back to AA or DHA to AA through a non-enzymatic reaction, while being oxidized and subsequently regenerated to its reduced form using NADPH or NADH[60]. According to the kinetic equation (

$ {K}_{cat}AAO=\dfrac{{V}_{max}\cdot R\cdot {DHA}^{2}}{{K}_{m}+R\cdot DHA} $ Functions and applications

-

AAO's active site comprises copper ions crucial for electron transfer during oxidation, serving as a terminal oxidase in the electron transport chain. It regulates intracellular redox homeostasis by transferring reducing power to oxygen via the AA and glutathione systems, effectively reducing oxygen to water and mitigating reactive oxygen species[61,62]. The role of AAO in wheat-based systems is well-established. In industrial bread making, AAO acts synergistically with ascorbic acid to enhance dough functionality. It has been shown that the combination of AAO with SOX increases the dough's resistance to elongation by 37% and reduces elongation by 23%. A tenfold reduction in the amount of ascorbic acid in the presence of SOX gave approximately the same results. Further research is needed to optimize AAO formulations for consistent performance in industrial applications.

Glutathione-ascorbate oxidoreductase

-

Glutathione-ascorbate oxidoreductase, also known as dehydroascorbate reductase[63], is an enzyme from the glutathione transferase family that reduces DHA to AA with the help of glutathione, thereby maintaining intracellular AA levels. DHAR complements AAO activity by ensuring a steady supply of ascorbic acid, vital for maintaining the redox state of gluten proteins.

Types and overview

-

DHAR participates in the ascorbate-glutathione cycle, utilizing glutathione to reduce dehydroascorbic acid to ascorbic acid[64]. AA is an important antioxidant that protects cells from oxidative stress damage. DHAR plays a crucial role in the ascorbate-glutathione (AA-GSH) cycle, preventing oxidative damage to cellular proteins by excessive hydrogen peroxide and other reactive oxygen species[65]. As shown in Fig. 1b(4), DHAR has typical glutathione transferase structural domains, including an N-terminal hydrothiol-binding domain (G-site) and a C-terminal substrate-binding domain (H-site)[64]. The active site contains a conserved serine residue that interacts with glutathione, facilitating catalysis[66]. DHAR's primary function is to reduce DHA to AA, maintain AA homeostasis, and protect proteins from reactive oxygen species (ROS) damage[67]. DHAR can be categorized into two types based on substrate specificity and affinity: one with a high affinity for both DHA and GSH and another with a low affinity for DHA but a high affinity for GSH[63]. Recent studies have shown that glutathione metabolism is not only involved in ROS scavenging but also regulates the detoxification of methylglyoxal through the glyoxalase pathway. Methylglyoxal acts as a by-product of glycolysis, accumulating and inducing protein glycosylation damage under stress[68].

Composition and structure

-

DHAR consists of two identical subunits, each containing GSH-binding and DHA-binding domains that are coordinated by a water molecule. The active site is situated at the interface of both subunits and requires two GSH molecules and one DHA molecule for its catalytic activity. A tryptophan residue forms interactions with DHA[69]. As shown in Fig. 1b(4), DHAR also includes a catalytic active site and a transferase active site. The short distance between the G and A sites of DHAR and the presence of a conserved tryptophan residue at the A site may enhance its catalytic efficiency[65]. In wheat systems, DHAR is crucial for recycling DHA formed by AAO, maintaining adequate ascorbic acid levels for the redox environment and supporting disulfide bond formation in gluten proteins, thus improving dough elasticity.

Mechanisms of action

-

DHAR operates via a parallel double substitution reaction or Ping-Pong Bi Bi mechanism, where two active sites simultaneously bind substrate molecules and facilitate electron transfers to yield products[15,70,71]. As shown in Figs 2d and 3, DHAR's action can be divided into two steps. Initially, an active cysteine residue attacks DHA to release AA. Then, another cysteine or GSH reacts with the intermediate to yield a second AA molecule, with GSH or thioredoxin reducing the enzyme back to its state, producing GSSG[72]. The catalytic process involves a GSH-SH redox center that can alternate between GSH-SH and GSH-S-SG states. GSH-SH undergoes nucleophilic addition with DHA to form an intermediate and release AA. Another GSH engages in nucleophilic substitution to release another AA molecule, producing GSH-S-SG. GSH-S-SG can regenerate two GSH-SH molecules via glutathione reductase, submitting reducing power for subsequent reactions[65]. While AAO catalyzes the oxidation of AA to DHA, DHAR reduces DHA back to AA, sustaining ascorbic acid's antioxidant capacity within the cell. It has been found that spring wheat mitochondria regulate the cytoplasmic NADPH pool through the Ca2+-dependent NADPH oxidation pathway, which may indirectly affect the efficiency of DHA reduction by DHAR[73].

Function and applications

-

In terms of antioxidant defense, DHAR helps protect AA from being oxidized to DHA, thereby maintaining a high level of AA. In bread-making, DHAR impacts dough elasticity and stability by regulating GSH to GSSG ratios, affecting disulfide bond dynamics in gluten Generally, high DHAR activity is beneficial for improving bread quality[74]. The primary function of DHAR is to regenerate AA by reducing DHA, thereby maintaining intracellular AA recycling. This process indirectly supports the ability of AA to scavenge reactive oxygen species (e.g., H2O2 and O2−) and ensures that the cell continues to resist oxidative stress damage[75]. DHAR's activity is dependent on GSH availability and environmental factors like pH and temperature, necessitating careful control to optimize its effectiveness in industrial use. Future research should focus on improving DHAR activity in synergy with other endogenous enzymes to enhance dough stability and bread quality.

Other endogenous enzymes

Tyrosinase

-

Tyrosinase is a type 3 copper-containing monooxygenase that can be categorized into five groups in bacteria, catalyzing a wide variety of reactions[76]. It can accept monophenols or diphenols as substrates; for example, as shown in Fig. 2e, in the presence of molecular oxygen, phenol is hydroxylated to o-diphenol, which is then oxidized to quinone[77]. Tyrosinase-encoding genes have been extensively characterized from various sources, including bacteria, fungi, plants, and mammals[78−80]. Tyrosinase can form tyrosine-cysteine and tyrosine-lysine crosslinks. It can also couple to form tyrosine-tyrosine bonds[81]. In wheat systems, tyrosinase may enhance gluten functionality by promoting cross-linking reactions that strengthen the gluten network and improve dough elasticity. However, the precise chemical nature of these covalent bonds in food systems remains under-explored. Additionally, tyrosinase activity may lead to unwanted pigmentation, potentially limiting its application in some food contexts.

Laccase

-

Although both tyrosinase and laccase belong to polyphenol oxidases, their catalytic mechanisms and physiological roles exhibit distinct characteristics. Compared to the dual catalytic functions (hydroxylation and oxidation) of tyrosinase, laccase exhibits broader substrate compatibility through free radical-mediated polymerization of polyphenols.

Laccase, as depicted in Fig. 2f, is another multicopper oxidase that catalyzes the oxidation of phenols and aromatic while reducing molecular oxygen to water[82]. Unlike tyrosinase, laccase does not hydroxylate monophenols; instead, it generates organic radicals that can dimerize, polymerize, or undergo rearrangement reactions. Studies have found that using laccase in wheat dough improves dough strength and stability[17,83]. As shown in Fig. 2f, This is due to the cross-linking of ferulic acid-esterified arabinoxylans with cell wall polysaccharides, forming a gel with higher water-holding capacity and simulating the gluten matrix[84]. While laccase's ability to promote cross-linking reactions is promising, there is limited data on its efficiency and mechanisms of action in functional protein cross-linking. Further research is needed to determine its potential industrial applications and to evaluate its comparative effectiveness against other endogenous enzymes.

Peroxidase

-

Peroxidase is a heme-containing enzyme widely distributed in plants, animals, bacteria, and fungi. It catalyzes the oxidation of various substrates using hydrogen peroxide as an electron acceptor[85]. In addition to its peroxidase activity, it possesses thiol oxidase activity, facilitating disulfide bond formation and producing dityrosine bonds (see Figs 2g & 4) that strengthen the gluten network[86]. In wheat-based systems, peroxidase has been shown to catalyze the gelation of arabinoxylans through di-ferulic acid bond formation, enhancing dough stability and elasticity[87]. However, excessive peroxidase activity or hydrogen peroxide concentration may lead to over-oxidation, negatively affecting dough extensibility. Although peroxidase is a promising dough improver, its applications in non-food fields remain underexplored.

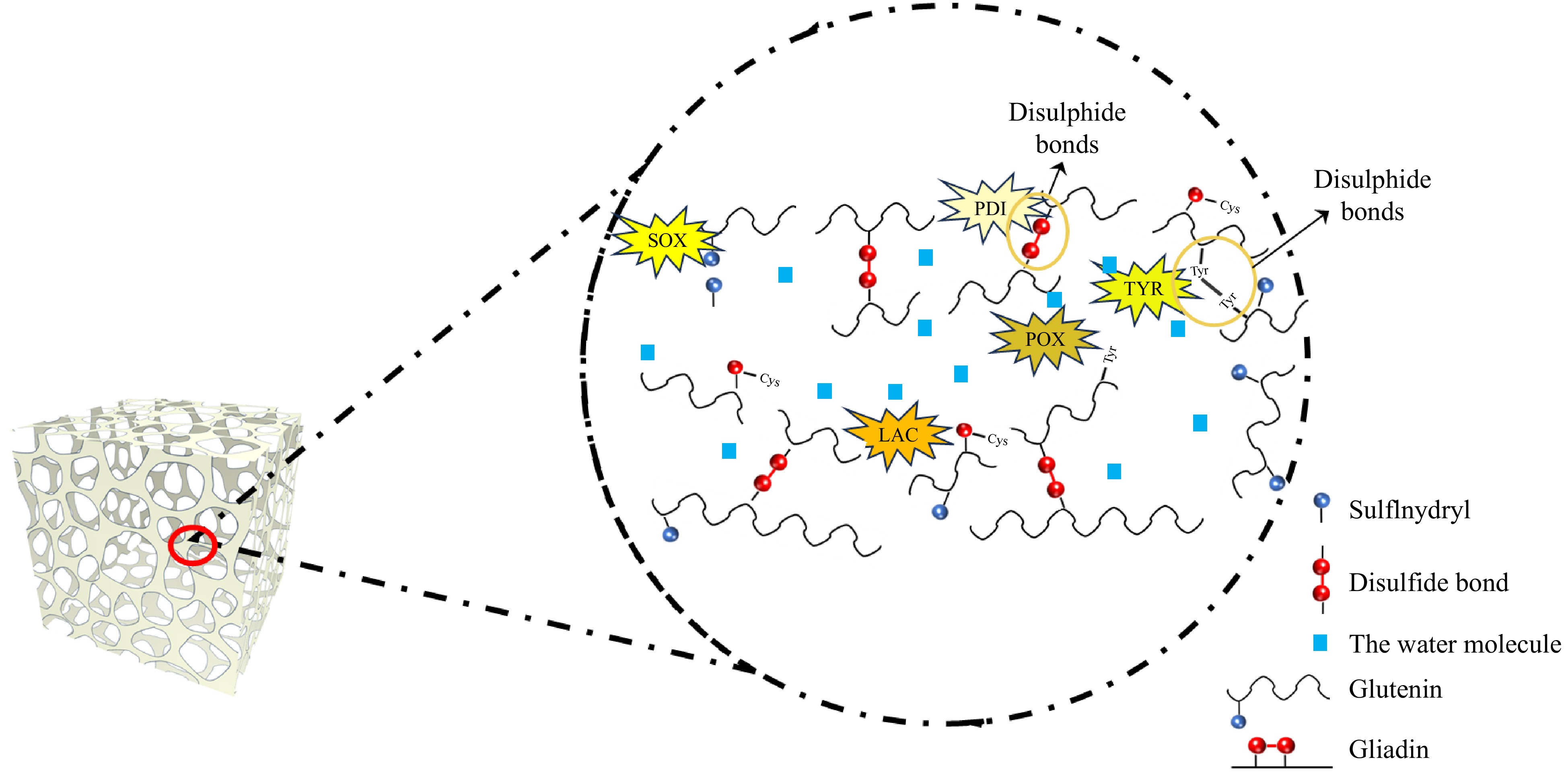

Figure 4.

Mechanisms of endogenous wheat enzymes in gluten cross-linking: reaction sites and bond types.

Catalase

-

Catalase is a heme-containing enzyme that decomposes hydrogen peroxide into water and oxygen. This enzyme's catalytic and peroxidase activities are crucial for managing oxidative stress in dough systems[88,89]. Catalase operates at high H2O2 concentrations for catalysis and low concentrations for peroxidase activity, oxidizing substrates like ethanol and phenols. Its breakdown of hydrogen peroxide can produce molecular oxygen, promoting disulfide bond formation between cysteine residues (see Figs 2h & 4), enhancing gluten strength[88,90]. Further research is needed to explore the regulation of catalase activity.

Lipoxygenase

-

Lipoxygenase is a non-heme dioxygenase that catalyzes the dioxygenation of polyunsaturated fatty acids, producing hydroperoxides[18]. As shown in Fig. 2j, the resulting H2O2 can aid disulfide bond formation in gluten, enhancing its network[91]. In wheat, lipoxygenase is mainly found in the scutellum and germ, with low activity in the endosperm[92]. In baking, it not only bleaches but also cleaves disulfide bonds and initiates cross-linking among free thiol groups, increasing disulfide bonds and free lipids[18]. The addition of lipoxygenase and enzymes enhances dough ductility and strength[93]. Though beneficial in bread-making, its role in other food applications requires further exploration.

Lipase

-

Lipase, as shown in Fig. 2i, is an enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis of triglycerides into free fatty acids and glycerol, along with transesterification and ester synthesis[20,94]. During dough mixing, it aids lipid redistribution, enhancing dough emulsifying properties and mimicking traditional emulsifiers like DATEM[95]. Excessive lipase/lipoxygenase activity promotes lipid oxidation during dough processing and storage, leading to the accumulation of rancidity-related aldehydes and ketones that generate cardboard-like off-flavors in whole wheat bread[96]. Thus, lipase may serve as a substitute or reduce the need for traditional emulsifiers. While promising, further research is required to clarify lipase's effects on dough systems and bread quality.

NAD(P)H-dependent dehydrogenase

-

NAD(P)H-dependent dehydrogenases are enzymes that oxidize substrates by transferring electrons to NAD+, producing NAD(P)H. These enzymes can oxidize various substrates[8]. NAD(P)H-dependent dehydrogenases catalyze the oxidation of reducing substrates (e.g., alcohols, aldehydes) in the dough, generating NAD(P)H that reacts with molecular oxygen to form superoxide radicals (O2−)[5,24]. These radicals induce oxidative modifications in gluten proteins through two primary pathways: (1) Oxidation of cysteine thiols (-SH) to sulfenic (-SOH), sulfinic (-SO2H), or disulfide (-S-S-) forms, promoting both intra- and intermolecular cross-linking; (2) Conversion of tyrosine residues to tyrosyl radicals, which undergo dimerization to form dityrosine bridges, enhancing gluten network rigidity[97]. NADH and NADPH enhance bread production by influencing gluten cross-linking. As shown in Fig. 2k, the conversion of NAD+ or NADP+ to NADH or NADPH can generate superoxide radicals, impacting dough characteristics[98].

-

Wheat endogenous enzymes are vital for altering gluten protein structure and functionality through mechanisms like disulfide bond formation, thiol oxidation, and covalent cross-linking. These activities improve gluten's viscoelastic properties, enhancing dough development and bread quality. As shown in Fig. 4, SOX, AAO, and peroxidase facilitate the formation of these bonds, which are essential for the structural integrity and strength of the gluten network. PDI ensures the proper folding and stability of gluten by rearranging disulfide bonds, while tyrosinase and laccase introduce additional covalent cross-links that further strengthen the glutenin network. The redox state modulation by DHAR and NAD(P)H-dependent dehydrogenases is essential for effective thiol-disulfide exchange, ensuring optimal gluten functionality.

Sulfhydryl oxidase

-

The FAD structural domain in SOX catalyzes disulfide bond formation between cysteine residues in proteins, enhancing glutenin network stability and strength by introducing new cross-links[99]. It efficiently facilitates disulfide bond formation between gluten by generating hydrogen peroxide, which non-enzymatically cross-links wheat gluten[12,100]. SOX enhances the gluten network by catalyzing sulfhydryl oxidation and indirectly generating H2O2 (inducing di-tyrosine cross-linking), thereby improving dough rheological properties (significant increase in elastic modulus G' and viscous modulus G''), with comparable or even superior effects to glucose oxidase[101]. Its interaction with ascorbic acid boosts gluten strength and loaf volume[102], though its role in flour milling quality needs further study.

Protein disulfide isomerase

-

PDI rearranges disulfide bonds in gluten, ensuring proper folding and stability of the gluten network[13]. It is crucial during dough mixing, as improper bonds weaken gluten structures. Wheat-derived PDI enhances dough toughness, elasticity, and adhesion, while reducing hardness[103]. It increases active sulfhydryl (SH) and disulfide (S-S) groups, improving quality[104]. PDI strengthens gluten networks, enhancing gas retention and bread volume but has less impact on ductility than exogenous oxidants. The addition of recombinant wheat PDI significantly enhanced dough tenacity and elasticity. At an optimal concentration of 80 mg/kg flour, PDI increased dough tenacity by 39% and ductility by 12% compared to the untreated control[103].

Ascorbate oxidase and glutathione dehydroascorbate oxidoreductase

-

AAO and DHAR work together to maintain redox balance in dough. AAO oxidizes AA to DHA, and DHAR reduces DHA back to AA using GSH. These reactions enhance gluten protein cross-linking and can aid PDI oxidation, promoting disulfide bond formation[105]. DHA's oxidation of GSH forms oxidized GSSH, which interacts with gluten, improving elasticity, gas retention, and bread volume[106]. Maintaining proper redox balance is essential for optimal gluten functionality.

Tyrosinase and laccase

-

Tyrosinase and laccase enhance the gluten network through oxidative cross-linking. Tyrosinase promotes cross-linking between protein molecules by oxidizing tyrosine residues to generate reactive quinones, thus improving the network structure of gluten-free dough and enhancing its viscoelasticity[81]. Both enzymes boost bread volume and crumb softness, especially with xylanase[16]. Laccase oxidizes phenolic compounds like ferulic acid, generating free radicals that cross-link proteins and polysaccharides, simulating gluten's structural effects in dough[17,107]. However, excessive laccase activity may soften dough due to protein aggregation[16]. Thus, optimizing conditions is the key to ensuring consistent bread quality.

Peroxidase

-

Peroxidase catalyzes oxidation reactions using H2O2 as an electron acceptor, leading to dityrosine bond formation and protein-polysaccharide cross-linking[87]. These reactions enhance gluten network stiffness and stability while reducing dough stickiness. Peroxidase also promotes the oxidative gelation of arabinoxylans, forming interchain bonds that improve dough elasticity and water retention[87]. Its action involves creating interchain bonds among arabinoxylans or coupling them with gluten, ultimately changing dough texture[108]. Further research is needed on its applications in gluten-free formulations.

Catalase

-

Catalase is a heme-containing enzyme that decomposes hydrogen peroxide into water and oxygen, reducing oxidative stress in dough systems. This protects gluten proteins from over-oxidation and promotes controlled disulfide bond formation between cysteine residues, strengthening the gluten network and improving dough properties[88]. Increased catalase activity raises SDS-insoluble protein content, enhancing gluten network expansion and crumb structure. By lowering hydrogen peroxide levels, catalase prevents oxidative damage and maintains the required redox balance for optimal gluten functionality, improving dough elasticity, gas retention, and bread quality[23].

Lipoxygenase

-

Lipoxygenase contains non-heme iron that activates molecular oxygen and promotes the oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids. This non-heme iron catalyzes hydroperoxide formation, oxidizing thiol groups and creating disulfide bonds, which strengthen the gluten network[91]. Wheat lipoxygenase facilitates the cleavage and rearrangement of disulfide bonds, allowing new cross-links between gluten proteins, improving dough hardness, elasticity, and extensibility[19]. Similar effects are noted with soybean-derived lipoxygenase, which enhances dough's rheological properties and extensibility[91,93].

Lipase

-

Lipase is an enzyme that hydrolyzes triglycerides into free fatty acids and glycerol, a process catalyzed by its catalytic triad (serine, histidine, and aspartic acid). Beyond hydrolysis, lipase also catalyzes transesterification and esterification reactions, producing polar lipids that interact with gluten proteins to enhance dough stability. During dough development, lipids are kneaded off starch granules and encapsulated in or interact with the gluten network[109]. Lipase modifies the lipid profile by converting bound lipids into free polar lipids, forming lipid-gluten complexes that stabilize the gluten network, improving dough elasticity and extensibility[21]. Optimizing lipase activity is vital to maximizing its benefits.

NAD(P)H-dependent dehydrogenase

-

NAD(P)H-dependent dehydrogenases are vital redox enzymes that transfer electrons to nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+/NADP+), producing reduced cofactors (NADH/NADPH). These cofactors maintain redox balance in dough, regulating reactions that affect gluten cross-linking and stability[24]. NAD(P)H is oxidized by endogenous oxidases, forming hydrogen peroxide, which enzymes like SOX and catalase use for disulfide bond formation and enhancing gluten protein elasticity[98]. NAD(P)H also interacts with thioredoxins and glutaredoxins, enzymatic systems that directly affect the redox state of gluten proteins, promoting the formation of disulfide bonds and improving dough elasticity.

-

Dough's rheological properties, such as elasticity and stability, are influenced by enzymatic modifications to the gluten network, primarily through disulfide bond formation and oxidative cross-linking. These strengthen the gluten matrix, enhancing gas retention and improving bread quality. As shown in Fig. 5, enzymes like SOX, PDI, and AAO increase elasticity, while tyrosinase and laccase strengthen dough, though excessive cross-linking may reduce ductility. Lipases affect texture, but excessive hydrolysis can lead to stickiness. Proper redox balance maintained by glutathione-ascorbate oxidoreductase and NAD(P)H-dependent dehydrogenase is essential for maintaining dough strength and elasticity during mixing and fermentation.

Sulfhydryl oxidase

-

SOX, including Ero and QSOX enzymes, improves dough properties by catalyzing disulfide bond formation in gluten proteins, stabilizing the gluten network, and enhancing viscoelasticity and bread quality. Wheat Ero I enhances mixing, strength, and elasticity[110]. Similarly, rice QSOX boosts dough elasticity[111]. However, excessive SOX activity can lead to over-oxidation, resulting in a rigid gluten structure and reduced extensibility. Future research should optimize SOX activity for balanced dough strength and flexibility.

Protein disulfide isomerase

-

PDI rearranges disulfide bonds in gluten proteins, ensuring proper folding and structural integrity. This enhances dough elasticity and stability, improving handling and baking performance. Wheat PDI increases functional disulfide bonds and reduces inactive sulfhydryl groups, thus improving dough rheology[104]. Its effects vary by flour type, enhancing durum wheat but reducing high-gluten flour quality. High PDI activity may destabilize the gluten network, so future studies should focus on optimal levels for different wheat types.

Ascorbate oxidase and glutathione dehydroascorbate oxidoreductase

-

AAO and DHAR maintain redox balance in dough preparation. AAO oxidizes ascorbic acid (AA) to dehydroascorbic acid (DHA), facilitating disulfide bond formation in gluten. DHAR reduces DHA back to AA with glutathione (GSH), ensuring a continuous redox cycle[62]. AAO strengthens the gluten network and enhances dough elasticity, but its impact depends on AAO levels and oxygen[74]. Similarly, DHAR contributes to maintaining dough strength and elasticity by ensuring an optimal redox environment. Precise control of both enzymes is crucial to avoid overly rigid dough or weakened gluten networks in future formulations.

Tyrosinase and laccase

-

Tyrosinase and laccase are oxidative enzymes that enhance dough properties by catalyzing cross-linking reactions. Tyrosinase affects dough texture by oxidizing phenolic compounds and improves gluten-free oat bread quality, increasing volume and softness, while promoting protein aggregation[17]. Laccase oxidizes phenolic compounds, generating free radicals that stabilize the gluten network and improve bread volume and crumb texture, especially with xylanase[16,17]. Careful control of their activity is essential for optimizing dough strength and softness.

Peroxidase

-

Peroxidase catalyzes oxidative cross-linking reactions using H2O2 as an electron acceptor, promoting high-molecular-weight gluten polymers by covalently linking gluten subunits through disulfide and non-disulfide bonds[86]. While peroxidase enhances dough strength and handling, excessive cross-linking can decrease extensibility and adversely affect bread quality. Its synergistic effects with enzymes like glucose oxidase and xylanase are limited; it is most effective alone[112]. Increased protein cross-linking improves dough stability and strength. Research should explore optimal peroxidase conditions to balance dough strength and flexibility.

Catalase

-

Catalase is essential for maintaining oxidation balance in dough by breaking down H2O2 into water and oxygen, preserving gluten integrity. It aids disulfide bond formation, strengthening the gluten network and improving rheology. Recombinant wheat catalase enhances dough by reducing softness and increasing elasticity, resulting in higher bread volume and better texture[23]. Balancing catalase with other oxidative enzymes is crucial, as excessive activity may limit hydrogen peroxide for peroxidase reactions. Future research should explore its synergistic effects with other enzymes in optimizing dough and bread quality.

Lipoxygenase

-

Lipoxygenase is a non-heme dioxygenase that enhances dough stability and bread quality by oxidizing polyunsaturated fatty acids into hydroperoxides, promoting disulfide bond formation and thiol oxidation. This leads to a more homogeneous gluten structure and improved dough handling[19]. It also brightens crumb color and stabilizes dough, enhancing gas retention and bread volume[93]. However, excessive free radicals can negatively impact dough rheological properties, so managing its activity is essential for consistent quality.

Lipase

-

Previous studies have proposed that lipases from fungi and bacteria can enhance bread-making properties, especially in dough stability and air retention[113]. Lipases significantly boost dough quality by converting endogenous wheat lipids into polar lipids, strengthening gluten interactions. They improve elasticity, reduce viscosity, and enhance air retention, increasing bread volume and texture[114]. Low doses of lipase can match synthetic surfactants like DATEM, making them a natural alternative[21]. However, lipase effectiveness varies across different dough types and processes, warranting further research on optimal conditions for consistent results.

NAD(P)H-dependent dehydrogenase

-

NAD(P)H-dependent dehydrogenases catalyze the oxidation of reducing agents in dough, producing products that trigger secondary reactions, which promote protein interactions and cross-linking, enhancing gluten stability. Their activity improves dough elasticity, strength, and handling[8]. While NAD(P)H-dependent dehydrogenases theoretically contribute to gluten cross-linking, their impact on dough rheology and bread quality is less pronounced compared to other endogenous enzymes. This may be attributed to competition with other redox systems: the ascorbate-glutathione and thioredoxin systems dominate redox regulation in dough. For instance, glutathione reductase and DHAR actively recycle glutathione and ascorbate, overshadowing NAD(P)H-dependent pathways[115]. More research is needed to identify optimal conditions for their use in baking and to explore their synergistic effects with other endogenous enzymes for better dough rheology and bread quality.

-

This review offers an in-depth analysis of how wheat endogenous enzymes enhance gluten cross-linking and improve dough rheological properties and bread quality. It details the types, structures, and mechanisms of these enzymes, highlighting their roles in strengthening the gluten network. Endogenous enzymes represent a paradigm shift in clean-label food innovation, leveraging wheat's innate biochemical machinery to enhance gluten networks without compromising consumer safety. Despite advancements in understanding their activity, challenges persist, necessitating further research into their molecular mechanisms and regulatory factors. Future studies should compare endogenous enzymes with exogenous oxidants regarding food safety and cost-effectiveness, optimize reaction conditions for better enzyme performance, and explore strategies to modulate gluten cross-linking for improved dough rheology and bread quality across various applications.

This work was supported by the Joint Fund of Science and Technology Research and Development Plan of Henan Province in 2022 (225200810110); Scientific and Collaborative Innovation Special Project of Zhengzhou, Henan Province (21ZZXTCX03); Youth teachers in colleges and universities of Henan province fund (2023GGJS061); Special Funds to Subsidize Scientific Research Projects in Zhengzhou R&D (22ZZRDZX34); and the open project program of the National Engineering Research Center of Wheat and Corn Further Processing, Henan University of Technology (NL2022016).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design, analysis and interpretation of results: Wang J, Liang Y, Zheng C; writing − original draft: Liang Y, Zheng C; writing − review & editing: Zheng C, Zhang P; data collection: Zhang Y, Liu H. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Agricultural University, Zhejiang University and Shenyang Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Liang Y, Zheng C, Zhang Y, Liu H, Zhang P, et al. 2025. Role of endogenous wheat enzymes on gluten cross-linking and dough and bread properties: a review. Food Innovation and Advances 4(3): 321−333 doi: 10.48130/fia-0025-0030

Role of endogenous wheat enzymes on gluten cross-linking and dough and bread properties: a review

- Received: 21 January 2025

- Revised: 21 April 2025

- Accepted: 23 April 2025

- Published online: 24 July 2025

Abstract: The quality of wheat-based products is significantly influenced by the structure and properties of gluten, and these are affected by various endogenous enzymes. However, the specific mechanisms of these enzymes, such as sulfhydryl oxidase, protein disulfide isomerase, ascorbate oxidase, and dehydroascorbate reductase have not been well studied. The role of these enzymes in enhancing gluten network formation and dough properties is not yet fully understood. This review examines the types, structures, and mechanisms of these key enzymes, with a focus on their roles in promoting disulfide bond formation and improving dough rheology and bread quality. By elucidating the mechanisms through which these enzymes directly or indirectly influence the structure, function, and physicochemical properties of gluten proteins, this review provides critical insights that advance understanding of gluten cross-linking and lay the groundwork for practical strategies to enhance the quality and safety of wheat-based products in food processing.

-

Key words:

- Gluten /

- Endogenous enzymes /

- Wheat-based products /

- Physicochemical properties /

- Rheological properties