-

Cellulose nanofiber (CNF), a form of nanocellulose characterized by both amorphous and crystalline regions, possesses diameters and lengths ranging from 10 to 100 nm. The CNF is predominantly extracted from lignocellulosic materials such as wood or plant sources, including cotton, flax, and hemp, through mechanical processes that may be augmented with chemical or biological treatments[1]. CNF has garnered significant interest from both academic and industrial researchers due to its biodegradability, biocompatibility, thermal stability, and renewable nature[2].

In the food industry, CNF has emerged as a promising ingredient for enhancing food quality, leveraging its renewability, biocompatibility, bioavailability, and other desirable properties. It is extensively employed as a food stabilizer, dietary fiber, thickener, flavor carrier, and in the development of edible food packaging[3]. Studies have shown that the integration of CNF with other materials can confer beneficial functionalities, such as improved mechanical properties, antibacterial activity, and enhanced barrier characteristics[4]. The potential for CNF in food packaging is particularly noteworthy, as it can be used to create edible packaging that mitigates oxidative degradation and protects against physical and chemical damage during transportation and storage due to its superior barrier properties. Moreover, CNF enables the creation of intelligent and active packaging systems capable of monitoring food freshness[4]. With a high surface area and potent polymerization capabilities, CNF and its derivatives are also effective in delivery systems. Previous literature has highlighted its utility in drug delivery systems for monitoring and controlling drug release[5]. The application of CNF as encapsulating agents for targeted delivery of food functional and bioactive ingredients has garnered increasing attention for its superior embedding and controlled release properties.

This review provides an encapsulation of the preparation and functionalization processes of CNF, with a focus on its applications within the food sector. It covers the use of CNF as a food stabilizer, food additive, in food packaging, and as an ingredient in functional foods. Additionally, the review delineates the prospects and research directions for CNF in these areas. Finally, it identifies key issues and challenges that need to be addressed to facilitate the application of CNF in the food industry, offering a comprehensive perspective on the sustainable utilization of CNF in the future of food science and technology.

-

Wood is traditionally the predominant raw material used to produce CNF; however, non-wood biomass, including agricultural residues and industrial by-products, has garnered significant interest due to its abundance, renewability, and lower initial cost[6]. A variety of non-wood sources, such as cotton, bamboo, corn stover, rice straw, and bagasse, are all viable precursors to produce CNF[6,7]. The mechanical method is the most employed technique for CNF production, albeit its high energy consumption remains a notable drawback. Non-wood biomass typically possesses higher hemicellulose and lower lignin content, which can enhance the efficacy of both chemical and mechanical treatments during the production process. Moreover, the pretreatment of cellulose in the production of CNF can facilitate more efficient fibrillation, leading to a significant reduction in energy requirements[8].

Pretreatment

-

Current literature reports a variety of pretreatment methods commonly employed to produce CNF, which include chemical treatment, enzymatic processing, and ionic liquid pretreatment, among others[9−11].

Chemical treatment

-

The following chemical pretreatment methods are frequently cited in the literature to produce CNF and are summarized below: alkaline-acid treatment, TEMPO-mediated oxidation, and carboxymethylation. The impact on cellulose varies depending on the specific chemical reagents and treatment conditions used. These chemical modifications can introduce electrical charges to the cellulose surface while also conferring new properties to the resulting CNF[12].

Alkaline-acid pretreatment, a widely established chemical method in the field of chemistry, is often employed prior to the mechanical separation of nanocellulose. This process serves to remove hemicellulose, lignin, extracts, and waxes from the raw material[13]. The underlying principle involves the alkaline treatment causing fibrillation and swelling of the cellulose fibers, which in turn increases their surface area and ductility[14]. Consequently, the diameter of the CNF fibers decreases, leading to an enhanced aspect ratio and a more favorable fiber-matrix interaction due to the larger effective surface area[15].

TEMPO-mediated oxidation, initially applied to polysaccharides such as amylodextrin, pullulan, and starch, involves the introduction of functional groups, including carboxylate and aldehyde, to the cellulose structure. This is achieved using an oxidizing agent like sodium hypochlorite in the presence of the TEMPO radical and iodine or a bromide catalyst under appropriate conditions[16]. This technique has become the most prevalent method for CNF extraction. Following TEMPO oxidation, the addition of carboxyl groups to the cellulose molecule significantly increases its reactivity and adsorption capabilities while reducing its tendency to agglomerate[17]. Mechanically fractionating the TEMPO-oxidized nanocellulose (TOCNF) and adjusting the inter-fiber spaces allow for its application in drug and nutrient delivery systems[18]. However, the TEMPO oxidation process is indirect and pH-dependent, and the associated reaction system poses environmental hazards[11]. Furthermore, the safety of TEMPO-treated materials for food applications requires additional assessment.

Carboxymethylation is another commonly employed pretreatment method. The process begins with the swelling of cellulose by mixing it with aqueous sodium hydroxide, followed by the addition of an organic solvent, typically an alcohol like isopropanol, under vigorous stirring. Chloroacetic acid or sodium chloroacetate is then slowly introduced to facilitate carboxymethylation[4]. By manipulating reaction conditions such as temperature, reaction time, and chemical reagent concentration; side reactions can be minimized, thereby improving the yields and characteristics of the resulting carboxylated nanocellulose[19]. Previous studies have shown that carboxymethylated CNFs exhibit higher viscosity, better hydrogel strength, and water retention values, and carboxymethylated CNFs exhibit a uniform microstructure, ideal hydrogel strength, higher viscoelasticity, and high water retention in hydrogels[20,21]. The properties of carboxymethylated CNFs are dependent on the reaction conditions employed, and both the carboxyl content and the width of the CNFs affect their properties[22]. In practical research, the most suitable reaction conditions can be explored in a targeted manner.

Enzymatic pretreatment

-

Enzymatic pretreatment is employed to degrade non-cellulosic components of biomass, such as lignin and hemicellulose, thereby facilitating the isolation of cellulose. During this procedure, enzymes catalyze the hydrolysis of cellulose fibers either selectively or restrictively, depending on the specific enzyme and conditions used. Previous research has demonstrated that enzymatic pretreatment can enhance the thermal stability and crystallinity of CNF[23−25]. For instance, Zhang et al.[23] investigated the use of varying doses of xylanase to aid in the mechanical production of CNF. Their findings indicated that enzymatic treatment could improve the thermal stability of CNF, although the thermal stability decreased as the enzyme dosage increased. Rocha et al.[24] employed enzymatic hydrolysis to extract CNF from olive pomace. This process involved breaking the hydrogen bonds between cellobiose dimers, thereby shortening the chain and yielding CNF with enhanced thermal stability and crystallinity compared to the original olive pomace. Tao et al.[25] observed that the crystallinity and thermal stability of CNFs were improved due to the hydrolysis of hemicellulose on the surface of microfibers in bagasse pulp following xylanase pretreatment. Furthermore, several studies have highlighted that CNF films pretreated with enzymatic digestion exhibit superior optical and mechanical properties[26−28]. Enzymatic pretreatment is advantageous due to its mild conditions, which minimize damage to the product. However, this method typically necessitates a longer reaction time compared to acid hydrolysis[29].

Ionic liquid

-

Ionic liquids (ILs) are increasingly utilized in pretreatment processes due to their characteristic low melting points and low vapor pressures, which confer benefits such as non-flammability, reduced vapor pressure, and enhanced thermal stability[30]. The underlying concept involves dissolving cellulose in an ionic liquid, followed by high-pressure homogenization to isolate the nanocellulose fibers. Sui et al.[31] developed a pretreatment method using a combination of ionic liquids and ball milling to produce CNF from wheat straw. This approach facilitated the simultaneous removal of lignin and hemicellulose, reduction of cellulose crystallinity, and modification of cellulose morphology under mild processing conditions. Sankhla et al.[32] employed 1-n-butyl-3-methylimidazole chloride, an ionic liquid, in conjunction with Na2CO3 to pretreat bagasse for CNF preparation. Na2CO3 was used for the extraction of cellulose microfibrils, while the IL treatment facilitated further nanofibrillation, demonstrating an efficient and environmentally friendly process. It is crucial to note that the dissolution of cellulose in ionic liquids is influenced by various factors, including temperature, reaction time, microwave power, and the cellulose-to-ionic liquid ratio[33]. Peng et al.[34] utilized aqueous proton ionic liquid (PIL) pretreatment combined with ultrasonic treatment to prepare CNF. Their response surface optimization experiment revealed that excessive pretreatment time, high temperature, high PIL content, and an excessively high liquid-solid ratio in the pretreatment system could lead to excessive hydrolysis and result in reduced CNF yield. Therefore, in practical applications, it is imperative to determine the optimal pretreatment conditions based on the specific raw materials and ionic reagents employed.

Mechanical treatments

-

The mechanical extraction method involves the application of high shear force to cleave the cellulosic fibrils in the longitudinal axis to isolate the fibrils as nanofibrillated cellulose[35]. The process commonly employs three types of equipment for mechanical processing: ultrafine mills, high-pressure homogenizers, and high-pressure microfluidic processors. The selection of the most appropriate mechanical technology is contingent upon critical factors, including the type, morphology, and chemical properties of the diverse starting materials[36]. The preparation of CNF through mechanical means typically involves three common methods: high-pressure homogenization, micro-jetting, and milling. The principles underlying these methods, as well as their respective limitations in practical application, are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Principle and disadvantages of different mechanical methods for the preparation of CNF.

Method Principle Disadvantage High-pressure homogenization Pass the cellulose dispersion through the homogenization valve's tiny flow channel several times under high pressure (> 150 MPa)[37]. Strong peeling and shearing forces generated by the dispersion reduce the fibrillation of the cellulose. The reliability of the equipment is low, the maintenance work is complex, the preparation of homogenization is time-consuming, the energy consumption is high[38], and the size of CNF particles are too large to use directly[39]. Micro-Jet Similar to the high-pressure homogenization method, the cellulose dispersion is subjected to a huge shear force when passing through a zigzag flow channel under ultra-high pressure (> 300 MPa) and quickly ejects from a narrow valve port of 100−400 μm[40]. Under extremely high pressure, CNF's crystallinity will diminish, and as the number of processing steps grows, cellulose's creep flexibility and the fiber network structure tend to relax[41]. Milling The grinding process mainly uses a fixed groove disc and the mechanical force of a planetary mill or grinding disc to rub and shear the cellulose fibers and decrease the size of the fiber particles[42]. Fibrillation is achieved by narrowing the gap between the grinding discs and reducing the particle size of CNF. Production efficiency is limited because the distance between the discs must be continuously changed during the process. It is challenging to modify the distance between the discs because the cellulose is too small. When spinning at high speeds, two grinding discs may clash, introducing quartz or metal chips; The grinding disc's surface has a specific number of grooves that make it easy for cellulose to become embedded during the grinding process, producing uneven cellulose scale[43]. -

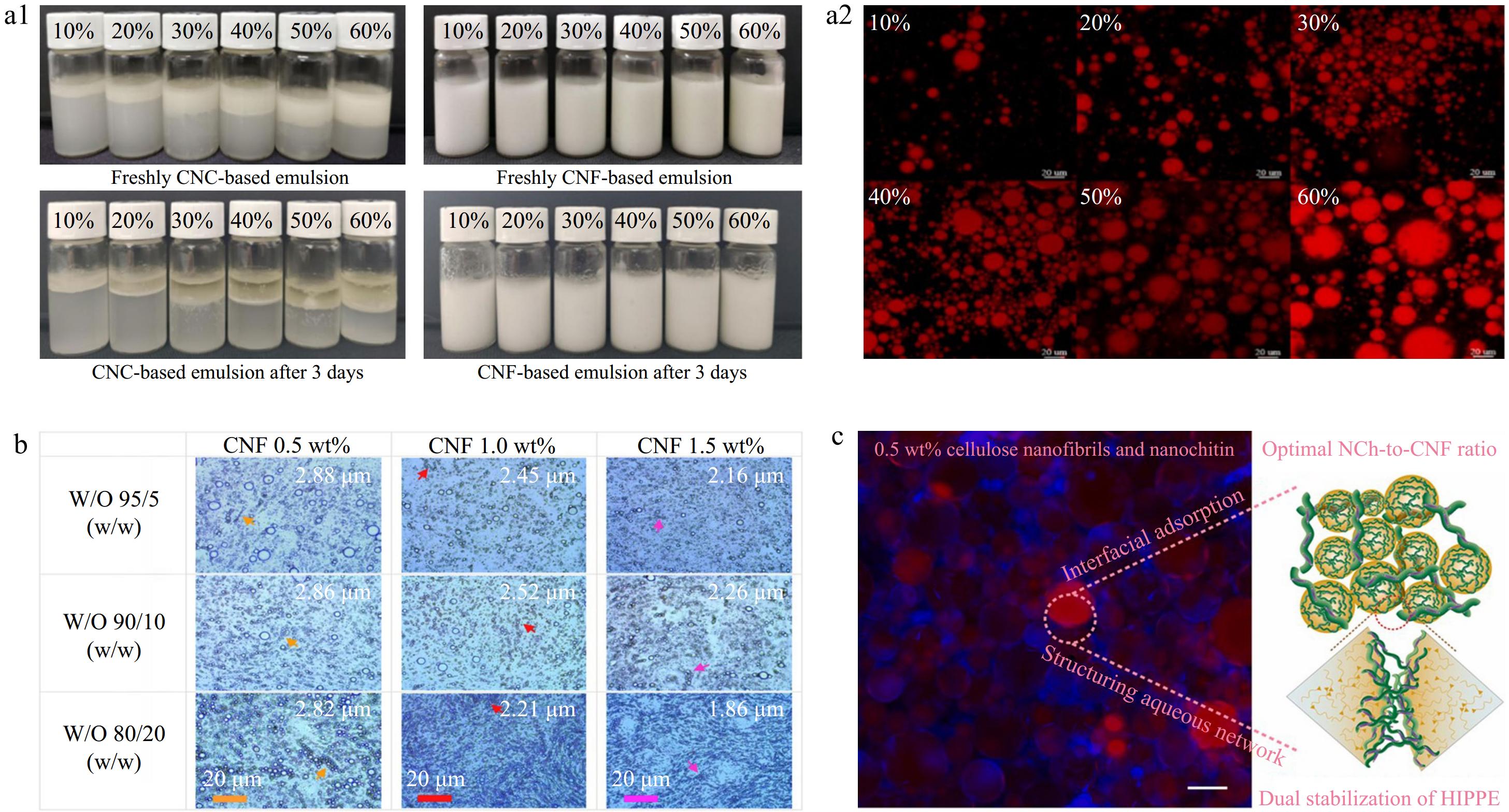

Pickering emulsions utilize solid or colloidal particles to stabilize the oil-water interface, replacing traditional surfactants. Unlike conventional emulsions, Pickering emulsions offer the advantage of protecting droplets against Ostwald ripening and coalescence due to the irreversible adsorption of nanoparticles at the oil/water interface[1]. These emulsions hold significant application potential in the food industry, serving as carriers for active substances and as fat substitutes thanks to their excellent biocompatibility[44]. Enhancing the stability of Pickering emulsions is a current research focus and challenge, with the key factors influencing stability being the emulsification and stabilization properties of the particles (Fig. 1). Gao et al.[45] utilized CNF and nanocellulose crystals (CNC) derived from grapefruit peel to stabilize Pickering emulsions for targeted lycopene delivery, finding that the CNF-stabilized emulsion exhibited superior storage stability compared to CNC (Fig. 1a). Lu et al.[46] used CNF as an emulsifier to prepare oil-in-water sesame seed Pickering lotion, and studied the influence of lotion morphology on the rheological properties of the system; the oil-in-water photos under the optical microscope confirmed that CNF can effectively stabilize the oil/water interface (Fig. 1b). Lv et al.[47] demonstrated the stabilizing effect of CNF in Pickering emulsions by complexing it with oppositely charged nanochitin (NCh) to stabilize oil-in-water high internal phase emulsions (Fig. 1c). The above studies have shown that the incorporation of CNF into Pickering emulsions can improve stability and mechanical properties, making them promising materials for clean and green food-related applications.

Figure 1.

CNF stabilized Pickering emulsion: (a1) Storage stability of Pickering emulsions prepared by CNF and CNC respectively stabilized with different oil contents. (a2) CLSM images of CNF-based Pickering emulsion (reproduced with permission from Elsevier)[45]. (b) CNF stabilized sesame oil-in-water emulsion oil-in-water morphology (reproduced with permission from Elsevier)[46]. (c) CNF and NCh to obtain a high internal phase Pickering emulsion (reproduced with permission from Elsevier)[47].

Edible food packaging

-

In recent years, there has been a surge in the search for sustainable alternatives to plastic packaging. Biocompatible macromolecules with film-forming capabilities, such as proteins and polysaccharides, have emerged as promising candidates for producing degradable films that could serve as viable substitutes for plastic packaging[48]. Edible coatings and films represent another alternative, with edible films primarily used for packaging applications and edible coatings applied directly to food surfaces to form a protective microlayer[49]. However, the performance of pure matrix edible films often falls short of practical application standards. Consequently, researchers are actively seeking materials that can enhance the inherent properties of these films while endowing them with additional functional attributes. Agustín et al.[50] demonstrated that incorporating CNF into soybean protein membranes could significantly improve their hydrophobicity, opacity, and mechanical strength. Niu et al.[51] utilized rosin-modified CNF as a reinforcing filler in polylactic acid films, which resulted in enhanced antibacterial properties against Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis, as well as improved oxygen barrier and mechanical properties. Nima et al.[52] showcased the potential of CNF to augment the barrier, mechanical, and thermal stability properties of tomato seed mucilage (TSM) films. Additionally, CNF was found to enhance the antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of the phenolic compounds and lycopene present in TSM. The above studies proved that the incorporation of CNF can enhance the tensile properties, barrier properties, antioxidant capacity, and antimicrobial properties of edible food packaging materials. These attributes are crucial for food packaging, and the addition of CNF allows for the creation of intelligent and active packaging solutions, thereby expanding its application scope within the food packaging sector.

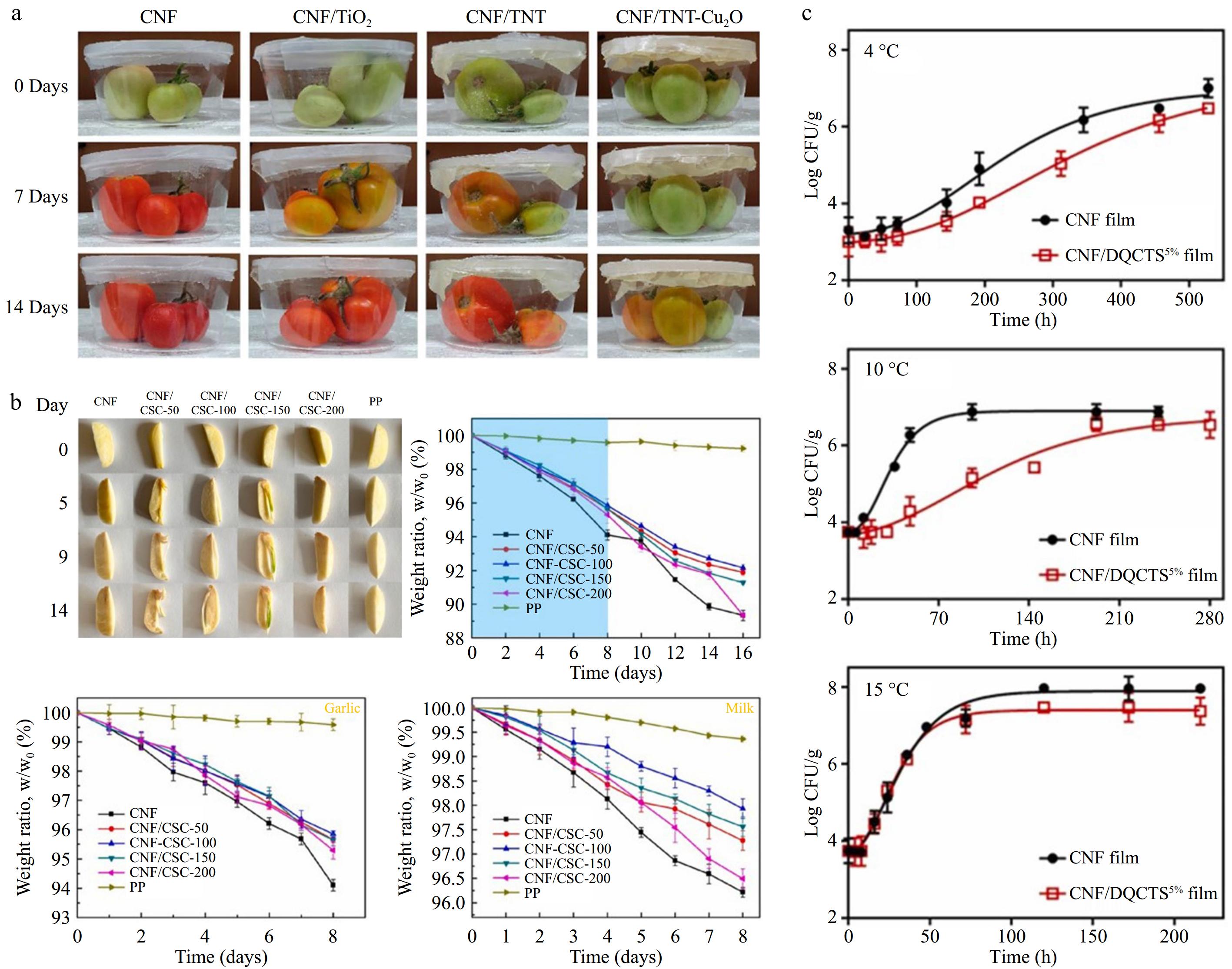

Active food packaging involves the release of active substances into the packaging environment to inhibit microbial growth, prevent oxidation, maintain food flavor and quality, and extend shelf life (Fig. 2). Riahi et al.[53] developed multifunctional composite membranes with CNF and TNT-Cu2O for tomato packaging, which not only extended shelf life and reduced post-harvest mass loss but also exhibited significant ethylene scavenging activity and bactericidal effects (Fig. 2a). Li et al.[54] created CNF/corn stover core (CSC) nanocomposites, addressing the mechanical weakness, poor water repellency, and lack of antimicrobial properties of CSC as a packaging material. These nanocomposites demonstrated excellent UV-blocking and bacterial blocking properties and performed well in packaging tests for garlic and milk (Fig. 2b). Kim et al.[55] prepared fully deacetylated quaternary ammonium chitosan and used it as a functional filler in CNF-based films for packaging raw salmon, which exhibited potent antimicrobial activity against Listeria monocytogenes (Fig. 2c).

Figure 2.

CNF can be used in food active packaging: (a) CNF-based film delays tomato ripening at 25°C (reproduced with permission from the American Chemical Society)[53]. (b) CNF-based film at room temperature for fresh garlic preservation test, solid food (garlic) and liquid food (milk) water loss over 8 d (reproduced with permission from Elsevier)[54]. (c) Antimicrobial effect of CNF-based film as raw salmon packaging: growth status of Listeria monocytogenes in CNF- and CNF/DQCTS-based film packaging of raw salmon at different temperatures (reproduced with permission from Elsevier)[55].

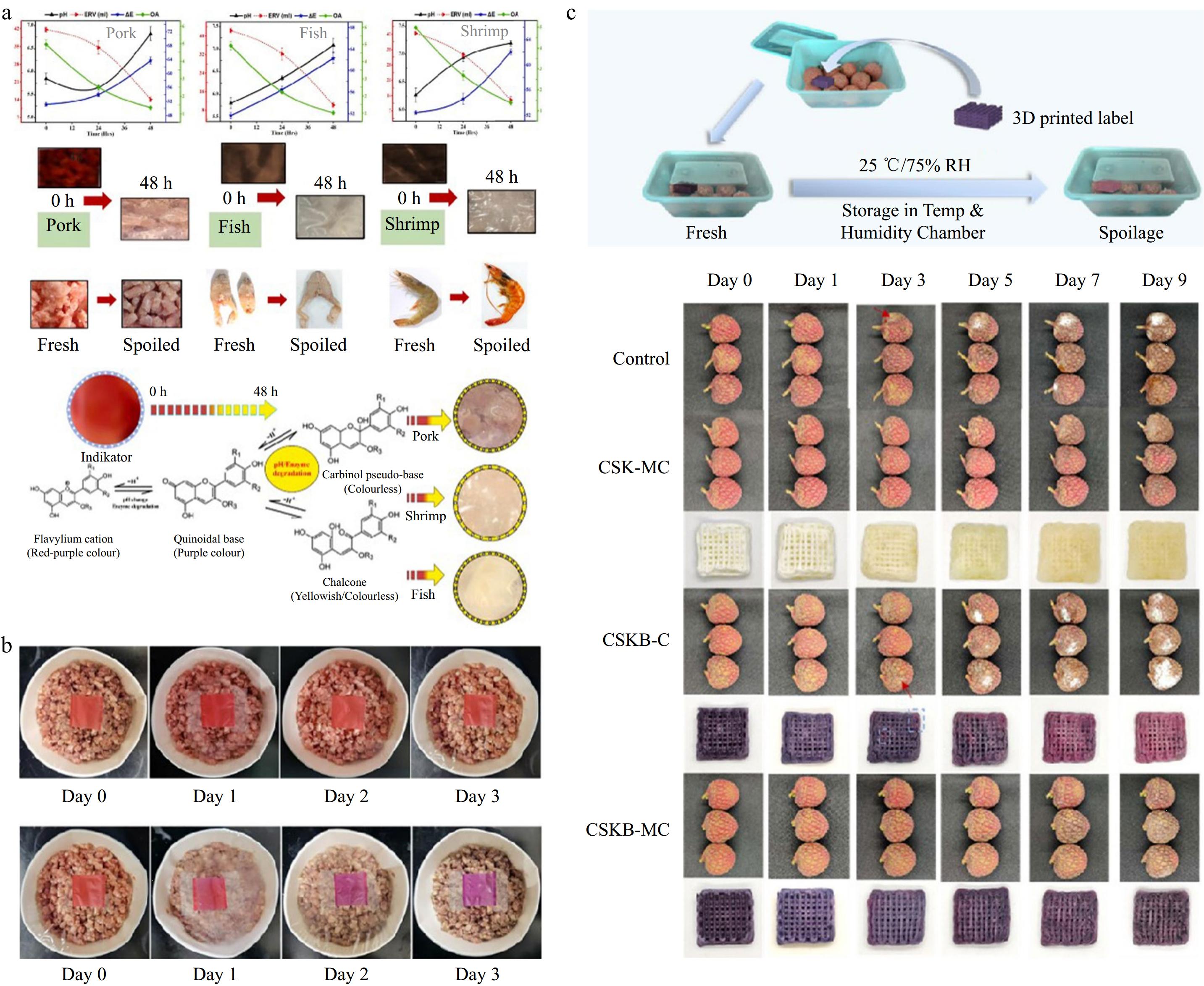

Intelligent food packaging, which incorporates materials that interact with the packaging environment, can monitor and reflect changes in the internal environment of the package. This capability allows for the assessment of food deterioration, freshness, and maturity during storage and transportation (Fig. 3). Wagh et al.[56] developed an intelligent nanocomposite film based on CNF, cabbage anthocyanin, and cabbage biowaste, which is capable of monitoring meat freshness in real-time through colorimetric changes (Fig. 3a) Jeong et al.[57] combined carotene pigment extract with CNF to create a pH-sensitive indicator film that can signal the freshness of minced pork by transitioning from red (indicating freshness) to purple (indicating spoilage) (Fig. 3b). Zhou et al.[58] fabricated a 3D-printed CNF-based label for fruit preservation and monitoring, which can indicate the freshness of lychee by altering the label's color (Fig. 3c). These studies collectively expand the application of CNF as a versatile material for multifunctional smart packaging.

Figure 3.

CNF can be applied to smart packaging: (a) Smart nanocomposite films based on CNF/cabbage anthocyanins/cabbage biowaste can detect changes in the quality of fish, pigs, and shrimps. (Reproduced with permission from Elsevier)[56]. (b) CNF film compounded with carotene pigment extract can detect the freshness of minced pork by color change (reproduced with permission from Elsevier)[57]. (c) CNF-based 3D printed label that can detect the freshness of lychee by color change (reproduced with permission from Elsevier)[58].

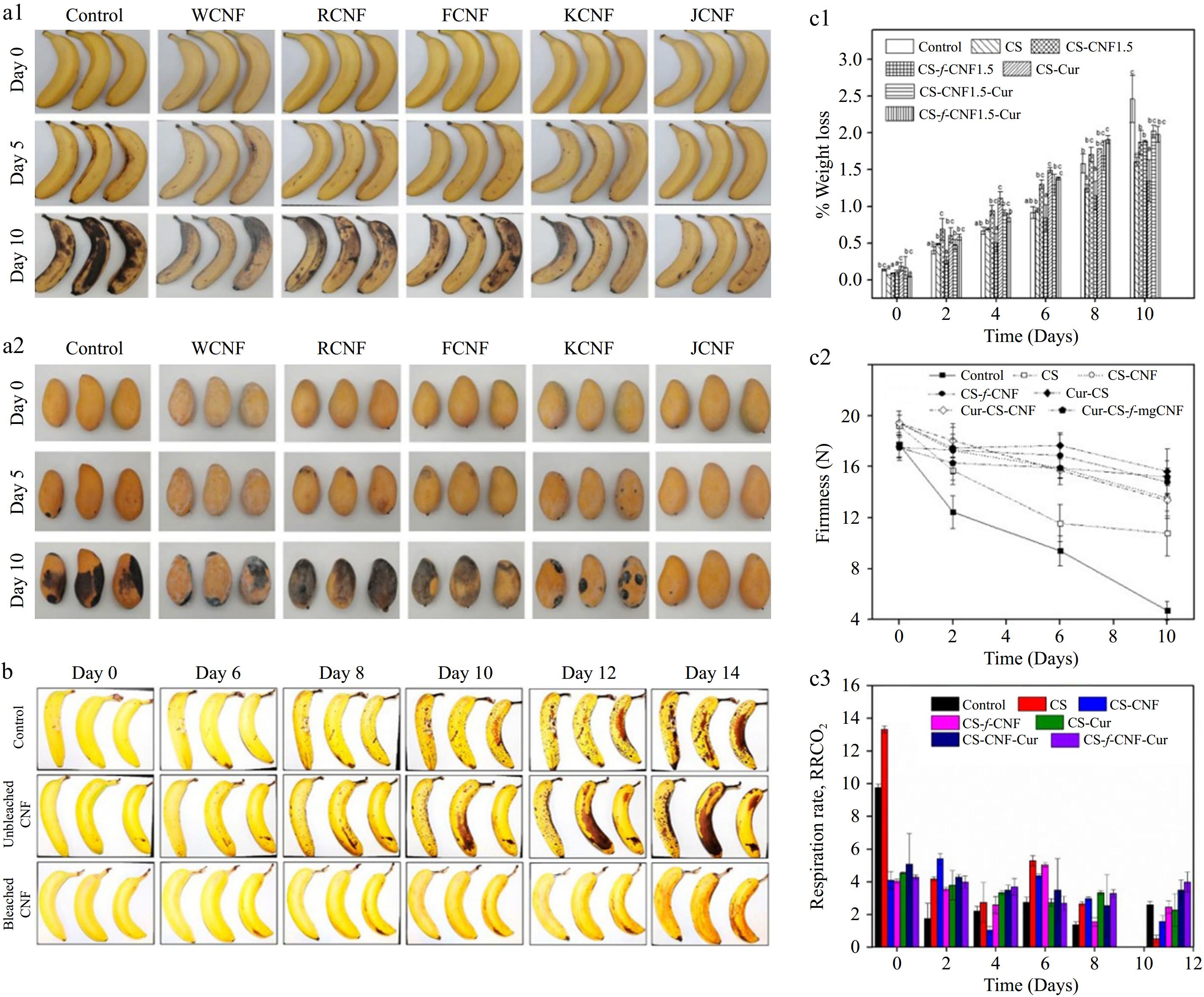

Edible coatings are utilized on fruits and vegetables to mitigate water loss, enhance texture, decrease respiration rates, and support the preservation of their physiological attributes. The incorporation of renewable biological resources, including their nanoscale forms, into coating materials can provide additional functionality. Wang et al.[59] applied jute-derived CNF as a coating material and sprayed it onto the surfaces of bananas, mangoes, and other fruits to create an active fresh-keeping film. This film exhibited robust antioxidant activity and effective oxygen and ultraviolet-blocking properties, thereby significantly extending the shelf life of bananas and apples at room temperature (Fig. 4a). Amoroso et al.[60] applied a carrot CNF suspension to the surface of bananas, which markedly delayed enzymatic browning for up to one week. These studies collectively confirm the efficacy of CNF composites as outstanding materials for the development of food coatings (Fig. 4b). Ghost et al.[61] utilized iron-functionalized nanocellulose fibers (i-CNF) to reinforce chitosan in the preparation of edible coatings for kiwifruit. These coatings effectively reduced quality loss (Fig. 4c1), firmness loss (Fig. 4c2), respiration rate (Fig. 4c3), and microbial count during storage.

Figure 4.

CNF can be used as a spray coating for food preservation: (a) Mitigation effect of different CNFs sprayed on the surface of (a1) bananas, and (a2) mangoes on their decay. (Reproduced with permission from the American Chemical Society)[59]. (b) Freshness of bleached and unbleached carrot CNF sprays for bananas (reproduced with permission from the American Chemical Society)[60]. (c) f-CNF enhanced chitosan edible coating for kiwifruit preservation: (c1) Weight loss. (c2) Texture analysis. (c3) Respiration rate of edible coated kiwifruit products stored at 10 °C (reproduced with permission from Elsevier)[61].

Sustained release and delivery system

-

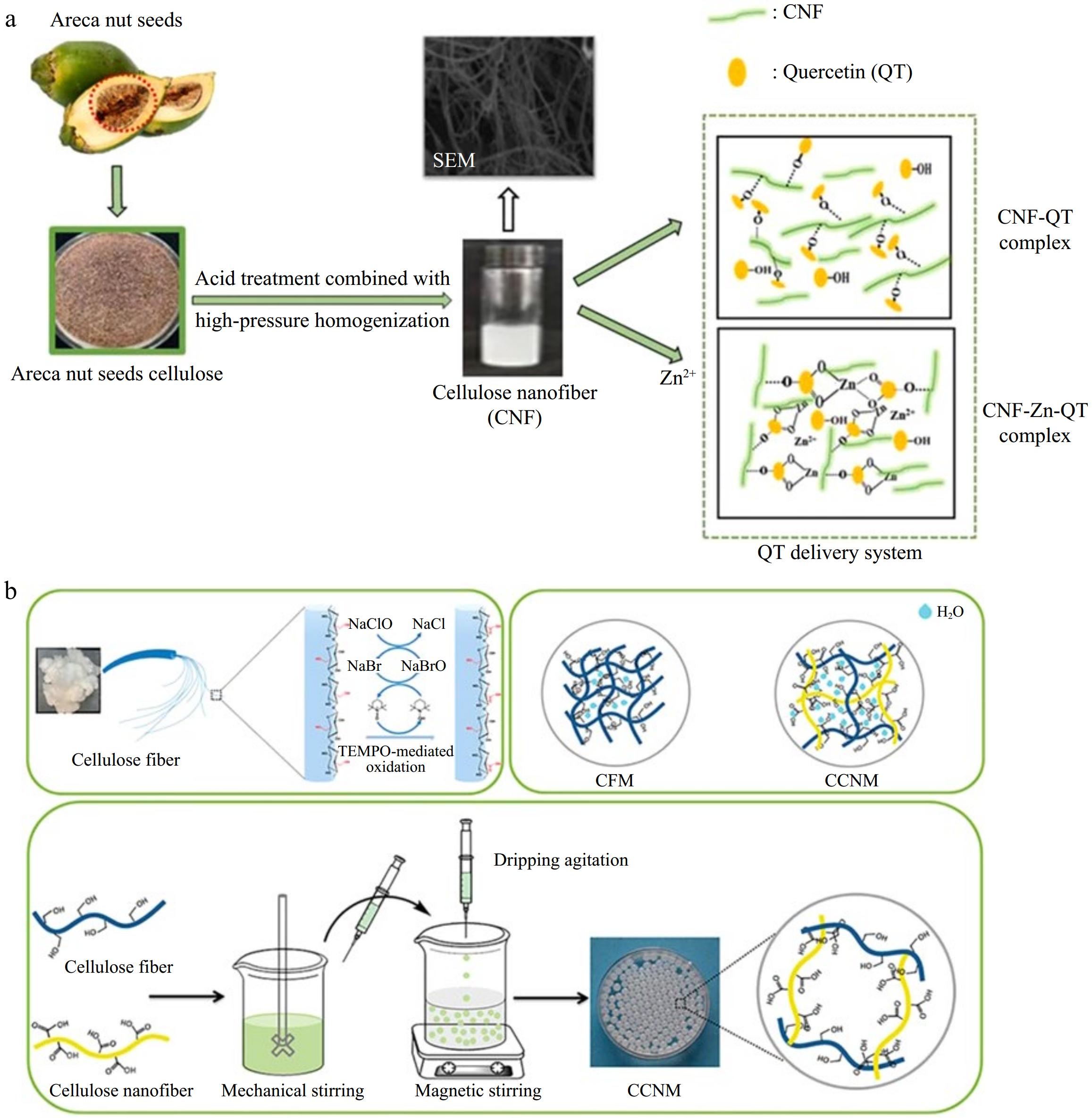

Recently, there has been a surge in the application of CNF as embedding materials in the field of biomedicine. Chen et al.[62] developed an ibuprofen-CNF delivery system. Putra et al.[63] integrated alginate hydrogels into CNF derived from the solid waste agar industry for the delivery of hydrophobic antibiotics. Wang et al.[64] grafted dopamine onto CNF functionalized with carboxyl groups, creating dopamine sustained-release delivery materials with enhanced biocompatibility. Several studies have demonstrated that nanoparticles, such as CNF, exhibit superior encapsulation efficiency and controlled release characteristics under simulated gastrointestinal conditions[65−67]. Research in the field of food science utilizing CNF has garnered increasing attention (Fig. 5). Chang et al.[65] showed that the immobilization and encapsulation of CNF can improve the photothermal stability of curcumin, effectively delaying and prolonging its release in the simulated gastrointestinal tract. This suggests a potential protective mechanism for the sustained release of curcumin. Li et al.[66] utilized leftover cellulose from betel nuts to fabricate a novel quercetin-supported CNF composite, incorporating zinc ions onto its surface (Fig. 5a). This composite boasts high capacity and encapsulation efficiency, exhibits robust antioxidant activity, and releases quercetin in a controlled manner. Luan et al.[67] prepared cellulose-based porous composite gels, where CNF was used to adjust pore size and pH, enabling the embedding and targeted delivery of probiotics (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5.

Application of CNF in the sustained-release delivery system: (a) CNF-based quercetin (QT) delivery system (reproduced with permission from Elsevier)[66]. (b) CNF-based macrogels as probiotic sustained-release delivery carriers (reproduced with permission from the American Chemical Society)[67].

Function food additives

-

Functional foods are designed to enhance health and prevent illness by incorporating new or existing ingredients. Dietary fiber, known for its benefits in alleviating obesity, reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease, and regulating intestinal flora[68], can be incorporated into functional foods. However, research has indicated that the addition of dietary fiber to food products may impact flavor[69], texture[70], and color[71]. Utilizing cellulose nanofibers (CNF) as a source of dietary fiber in functional foods not only increases the fiber content but also addresses the limitations associated with traditional dietary fibers[72]. Furthermore, CNF can be employed in the preparation of structured oils and fats as fat substitutes, contributing to the development of low-fat food products. Azeredo et al.[73] utilized CNF-based Pickering emulsion in the formulation of low-fat ice cream, with results demonstrating that CNF enhanced the organoleptic properties of the reduced-fat sample and improved its freeze-thaw stability. CNF's ability to form gels with a three-dimensional mesh structure in aqueous solution aids in enhancing the viscosity of the food system, thereby providing a texture similar to that of oil[74]. Velásquez-Cock et al.[75] incorporated CNF into low-fat ice cream formulations, potentially reducing fat instability and improving emulsion stability in these products by effectively covering the fat globules. Sensory experiments revealed that ice cream with higher CNF content was described as smoother and creamier. Hongho et al.[76] investigated the use of CNF as a partial replacement for egg yolk in salad dressings, showing that CNF in lime residue powder could prevent fat globule coagulation without significantly affecting the salad dressing's color.

Additionally, CNF can interact with other components within the food system, such as proteins, to prevent contraction and reorganization of the 3D network structure, thus forming a tight structure. CNF also fills the gaps within the food system's network structure, contributing to a soft texture reminiscent of fat during chewing and swallowing[74].

-

Environmental pollution and high energy consumption during the production of CNF present significant challenges to the sustainable and scalable manufacturing of high-quality CNF with optimal reactivity. The production process often requires substantial energy input, the use of hazardous chemical reagents, and high water consumption, and results in an uneven size distribution of the produced CNF, complicating the sustainable and large-scale production of CNF with desirable properties[77]. Various chemical and mechanical treatments are employed to remove hemicellulose, lignin, fat, wax, and pectin from the cellulose structure. Mechanical methods, such as high-pressure homogenization, micro-jet processing, and milling, are energy-intensive and can be cost-prohibitive. Chemical treatments, including alkaline-acid processing, TEMPO-mediated oxidation, and carboxymethylation[78,79], are considered effective in reducing energy consumption. However, these methods necessitate the use of large quantities of reactants and solvents, as well as substantial amounts of water for washing, dissolving compounds, and neutralizing acids. The use of acids and excessive water can lead to environmental pollution, and the energy demands of these pre-treatment steps in industrial-scale production are also significant barriers from a cost-benefit standpoint[80].

To mitigate energy consumption, it is imperative to conduct further study and research into the development of energy-efficient pretreatment techniques to produce CNF from an environmental perspective. Recent studies suggest that a synergistic combination of mechanical and chemical methods can lead to a reduction in overall energy usage[80−82]. Certain pretreatments have been applied to enhance the hydrogen bonding between cellulose fibers, thereby facilitating the loosening of fibers. Haroni et al.[80] proposed the use of bio-based electricity for heating and the substitution of bioethanol for ethanol to lessen environmental impact and reduce total energy demand. Pradhan et al.[81] employed ultrasound-assisted deep eutectic solvent treatment to produce CNF from barley straw, followed by high-intensity ultrasonication for nano-fibrillation. Pinto et al.[82] demonstrated that TEMPO-mediated oxidation could be used to create CNF without the need for mechanical defibrillation, thereby reducing the environmental impact associated with CNF production. An overview of the commonly used pretreatment methods for CNF production is provided above. However, enzymatic hydrolysis is costly and time-consuming; TEMPO catalysts are expensive and difficult to recycle; and the processes of carboxymethylation and cationization require the consumption of large quantities of organic reagents. Therefore, there is an expectation to develop pretreatment methods that are cost-effective, less polluting, and more efficient, tailored to the different sources and properties of CNF. Emerging pretreatment techniques such as organic acid hydrolysis, periodic acid oxidation, eutectic solvent pretreatment, and solvent-assisted pretreatment have been progressively developed in recent years as effective and environmentally friendly alternatives[83]. Table 2 summarizes the principles and advantages of some of these innovative pretreatment methods.

Table 2. The principles and advantages of the emerging pretreatment methods.

Method Principle Advantage Hydrolysis of organic acids[83] Organic acid hydrolysis of cellulose raw materials can reduce its particle size, and can hydrolyze the amorphous region of cellulose, improve the crystallinity of the final product, and can also graft functional groups such as carboxyl and ester groups on the fiber surface. CNF can be synthetically prepared by adjusting the hydrolysis conditions, and the organic acids after the reaction can be recovered with high efficiency by rotary evaporation or crystallization Periodite oxidation pretreatment[12, 84,85] By increasing the anionic charge density on the surface of cellulose fibers to reduce hydrogen bonds, periodic acid oxidation pretreatment combined with sodium hypochlorite oxidation or sodium bisulfite reduction can enrich the surface of microfibrils inside cellulose with carboxyl or sulfonic acid groups, thereby increasing the electrostatic repulsion of microfibrils against each other The electrostatic repulsion of the microfibrils against each other is increased, which greatly improves the nano-efficiency of the mechanical treatment process, thereby reducing energy consumption, and the periodate can be recovered efficiently during the pre-treatment process. Eutectic solvent pretreatment[36, 83] Deutscible solvent (DES) is a two-component or three-component eutectic mixture composed of a hydrogen bond acceptor and a hydrogen bond donor with a certain stoichiometric ratio. The functionalization of cellulose surface groups can be achieved by adding modification reagents. The physicochemical properties of DES are similar to those of ionic liquids, but they are less expensive to prepare, less toxic, biodegradable, and greener than ionic liquids. In addition, DES can achieve efficient recycling through a simple recycling process. Cytotoxicity

-

In the majority of literature, nanocellulose materials such as CNF are considered safe and non-toxic and have been utilized in the food industry for edible packaging, food additives, and as delivery systems for active ingredients. However, the biological effects of nanocellulose on the human body cannot be assessed solely based on its chemical properties due to the nanomaterials' size, shape, aggregation behavior, and other unknown factors that may influence their interaction with cells and organisms[86]. The characteristics of CNF, including its nanoscale size, high specific surface area, and reactivity, may lead to cytotoxicity[87]. Concerns about the use of nanocellulose as a food additive are heightened by the ease with which CNF particles can cross biological barriers and enter the circulatory system when ingested, potentially impacting human health. Therefore, a thorough toxicological assessment of nanocellulose is essential before its application. During the production of CNF, there is a potential health risk to workers from skin exposure or inhalation, necessitating long-term exposure studies that are characterized by actual workplace concentrations of nanocellulose[88]. Morias et al.[89] emphasize the need for safety profiles and additional toxicological studies for selected nanocellulose materials. These investigations should follow the protocols established by major international regulatory bodies, such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Chemicals Agency, to accurately categorize specific nanocellulose materials within chemical hazard classifications. Currently, there is a limited number of in vitro and in vivo studies on nanocellulose, and although the available evidence suggests that CNF is non-cytotoxic in these small-scale experiments, there is a lack of documented clinical trials involving CNF in food applications. In vivo experiments must be clinically validated before they can be deemed reliable. Given the difficulty of human systems in degrading nanocellulose materials and the uncertainty surrounding the interaction mechanisms between cells and nanocellulose, it is imperative to incorporate relevant clinical trial designs into future research to investigate the potential complications associated with the use of nanocellulose and its biomaterials in tissue engineering and other biomedical applications.

-

This review provides a concise overview of the utilization of CNF in the food industry over the past five years, with an emphasis on the difficulties encountered during their production and implementation. Traditional pretreatment methods, while reducing energy and environmental impact, face issues like high costs of enzymes and chemical agents and pollution from organic reagents. Developing cost-effective, efficient, and eco-friendly CNF preparation methods is a promising research direction. Moreover, the influence of diverse pretreatment and modification approaches on CNF performance, as well as the differences in CNF characteristics depending on their source, play a crucial role in determining their suitability for specific food applications and merit further exploration.

The high water-holding capacity and thickening effect of CNF can be used to develop fat substitutes and increase its dietary fiber content in functional foods. Due to its excellent bioactivity, biocompatibility and mechanical properties, CNF has also been widely studied for the preparation of sustained-release nutrient delivery systems, active packaging and smart packaging. More research should focus on preventing microbial contamination and ensuring packaging stability without altering the physical and chemical properties of CNF. The development of more standardized and stringent management regulations is essential for the safe and effective use of CNF in the food industry.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32272343).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: investigation: Liang J, Xu B, Liu P, Bai C; formal analysis: Liang J; methodology: Lu S, Ma T; conceptualization, funding acquisition, resources: Song Y; writing − original draft preparation: Liang J; writing − review & editing: Ma T. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this review article as no datasets have been generated or analyzed.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Agricultural University, Zhejiang University and Shenyang Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Liang J, Xu B, Liu P, Bai C, Lu S, et al. 2025. Cellulose nanofiber in the food industry: a review of its applications, challenges, and prospects. Food Innovation and Advances 4(3): 352−362 doi: 10.48130/fia-0025-0033

Cellulose nanofiber in the food industry: a review of its applications, challenges, and prospects

- Received: 20 December 2024

- Revised: 01 March 2025

- Accepted: 04 March 2025

- Published online: 26 August 2025

Abstract: Cellulose nanofiber (CNF) is renowned for its renewable nature, biocompatibility, and high bioavailability, making them a valuable resource within the food industry. The CNF serves as effective stabilizers in emulsions and hydrogels, with their functionality significantly enhanced through modification and functionalization processes. CNF demonstrates considerable promise in the development of intelligent food packaging and food coatings and in the encapsulation and delivery of active ingredients. This article provides an overview of the research achievements on Web of Science since 2018 and briefly outlines the preparation methods of CNF, including chemical, enzymatic, ionic liquid pretreatment, and mechanical treatments. Furthermore, the current application status of CNF in the food sector is described in detail. It further identifies the technical hurdles associated with CNF utilization, addressing concerns related to energy consumption and pollution during its production, as well as the potential toxicity that may arise during the preparation process and subsequent food industry applications. By highlighting these challenges and concerns, the paper aims to guide future research directions for the application of CNF in the food domain.