-

Plant-derived proteins and their functional properties have attracted considerable attention in recent decades. Plant proteins exhibit high health and nutritional value, and are often recommended for vegetarians and patients suffering from heart disease, diabetes, obesity, and cancer[1]. Concurrently, plant proteins are being developed as alternatives to animal proteins in the human diet because of their environmental friendliness and affordability. However, it is estimated that only 33% of plant proteins are utilized in food production, with a further 26% being allocated to animal feed or discarded, with approximately 40% remaining unexploited[2]. This amount of plant-derived proteins that are not fully utilized is equivalent to the total global production of animal protein[3,4]. The mounting interest in the significance of proteins derived from diverse plant sources in the human diet has prompted nutritionists to undertake research into their functional and nutritional characteristics.

Lacquer tree seed protein isolate (LSPI) is a novel plant protein resource with significant potential for development. LSPI accounts for 40% of lacquer tree seed meal and is abundant in essential amino acids, exceeding that of defatted soybeans[5]. The lacquer tree is renowned for the raw lacquer from its bark, which is extensively utilized in the production of Chinese lacquerware[6,7]. Moreover, lacquer tree seeds are frequently used for the extraction of oil and wax, which are pivotal plant-derived edible oils and chemical raw materials for soap, cosmetics, and candles[8,9]. However, it is estimated that over 20,000 tons of LSPI-rich lacquer seed meal is generated annually during the oil/wax extraction. These by-products are then processed into low-value animal feed and discarded, thus causing severe waste[10,11]. Developing LSPI as a novel plant-based food ingredient in food formulations is an effective way to solve the waste of this resource and enhance its industrial value.

Plant proteins generally demonstrate inferior functionalities (e.g., emulsifying attributes) compared with animal proteins, thus necessitating additional structural modifications[12]. Proteins are frequently used as food emulsifiers because of their amphiphilic properties. Nonetheless, plant proteins exhibit a greater prevalence of β-layers and fibrillar protein structures than animal proteins[13]. This structural characteristic restricts the capacity of plant protein molecules to adsorb at the oil–water interface. The overarching strategy involves physical, chemical, and enzymatic processing, all with the objective of modifying plant protein structures and improving their emulsifying characteristics. Ultrasound has been demonstrated to enhance the solubility and dispersibility of protein from soybean, broad bean, and wheat, thereby improving their emulsification properties[14]. This improvement is primarily attributed to acoustic cavitation effects that disrupt protein aggregates, unfold compact structures, and expose buried hydrophilic and hydrophobic residues. Such structural rearrangements increase surface activity and facilitate better dispersion of protein molecules in aqueous systems[15]. Acid, alkaline, and enzymatic hydrolysis impact the degree of protein hydrolysis, thereby effectively reducing the size of plant protein aggregates and enhancing their emulsification properties[16]. Heating also functions as an effective strategy for altering the structure and aggregation state of pea proteins, thereby making them an excellent emulsifier[17].

The capacity of plant protein emulsions to deliver hydrophobic active ingredients, such as curcumin, is another significant indicator[12]. Curcumin (C21H20O6), the principal polyphenolic constituent of Curcuma longa (turmeric), consists of two O-methoxy phenolic rings linked by a conjugated α, β-unsaturated β-diketone chain, giving it strong antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, and neuroprotective activities[18]. However, its extremely low water solubility (< 0.1 mg/mL), rapid metabolic degradation, and poor intestinal absorption result in oral bioavailability below 1%[19]. Notably, curcumin is chemically unstable in aqueous environments, particularly at neutral and alkaline pH values (around pH 7), where it undergoes rapid hydrolytic and oxidative degradation—approximately 90% degradation within 30 min at pH 7.2 and 37 °C[20]. Consequently, the development of efficient delivery systems is critical to enhance curcumin's solubility, stability, and intestinal release. Protein emulsions could protect active materials from degradation in the stomach and ensure their efficient release in the intestinal tract. This phenomenon is referred to as gastroprotection–intestinal release, an effect that can significantly enhances curcumin's bioavailability and bioactivity through synchronizing its release with absorption sites[21]. Nevertheless, designing protective and stimulus-responsive protein emulsions remains challenging[22]. In our previous study, several modification approaches, including enzymatic hydrolysis, ultrasonic treatment, and thermal processing, were systematically compared to enhance the functional and interfacial properties of LSPI. Among them, heat treatment was identified as the most effective and practical strategy, as it significantly improved the emulsifying capacity and stability of LSPI through controlled structural unfolding and rearrangement. Therefore, the present work focuses on elucidating the mechanism by which heat-induced structural changes in LSPI contribute to improved interfacial performance and efficient delivery. However, the suitability and underlying mechanism of LSPI emulsions as an effective and targeted curcumin delivery system remains to be ascertained.

The primary objective of this study was to investigate the potential of heat-treated LSPI emulsions as an effective delivery system for lipophilic bioactive compounds, using curcumin as a model compound. Curcumin encapsulation efficiency and the storage stability of emulsions stabilized by different temperature-treated LSPI samples were first evaluated. Then curcumin's bioaccessibility and the effectiveness of delivery in emulsions stabilized by different temperature-treated LSPI samples were determined using a simulated digestion system in vitro. The underlying mechanism contributing to the ‘gastric shield–intestinal release’ effect of the LSPI emulsion was finally elucidated through combining the physicochemical, structural, and rheological characteristics. This study provides a theoretical foundation for developing LSPI as a novel plant-based emulsifier, but also contributes to the advancement of sustainable delivery systems for fat-soluble nutraceuticals such as curcumin, thus enhancing LSPI's wide application in the food industry.

-

Lacquer seed meal was provided by Shaanxi Qinqiao Agroforestry Biotechnology Co. Ltd (Shangluo, China). Lacquer seed oil was supplied by Henan Jingsen Oil & Fat Co Ltd (Henan, China). All chemical reagents used in this research were of analytical grade and were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Shanghai, China).

Preparation of LSPI

-

LSPI was prepared by the alkaline extraction–acid precipitation method[23]. Defatted lacquer seed powder (1:10, w/v) was dispersed in deionized water, adjusted to pH 10.0 with 1M NaOH, stirred at 50 °C (90 min), and centrifuged (4,000 rpm for 15 min). The supernatant was then acidified to pH 4.5 (with 1 M HCl), incubated for 2 h, centrifuged (4,000 rpm for 15 min), and lyophilized to obtain the final product.

Preparation of LSPI-stabilized curcumin emulsions

-

The LSPI-stabilized curcumin emulsions were prepared by mixing a curcumin solution with an LSPI dispersion. The curcumin solution (1 mg/mL) was obtained by dissolving curcumin in lacquer seed oil under dark conditions with continuous stirring for 2 h. Specifically, 10 mg of curcumin was dissolved in 10 mL of lacquer seed oil to prepare the stock solution, which was subsequently used as the oil phase for forming the emulsion. The LSPI dispersion (50 g/L) was prepared by suspending LSPI in a 0.01 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and subjecting it to heat treatment at 70, 90, 120, or 140 °C for 20 min. Emulsions were produced by blending the curcumin solution and the LSPI dispersion at a 1:9 (v/v) ratio, followed by homogenization at 16,000 rpm for 3 min and high-pressure homogenization at 45 MPa using a JN-Mini Pro homogenizer (JNBIO, Guangzhou, China). To inhibit microbial growth, 0.02% sodium azide was added to the emulsions[10]. The resulting emulsions, stabilized with LSPI that had been preheated at 70, 90, 120, and 140 °C, were designated as LSPI-70, LSPI-90, LSPI-120, and LSPI-140, respectively.

Encapsulation efficiency of LSPI-stabilized curcumin emulsions

-

Curcumin was extracted from the emulsion system using the ethanol emulsion breaking method with slight modifications[24]. Briefly, 0.3 mL of the emulsion samples were collected, diluted with anhydrous ethanol at a 1:5 (v/v) ratio, and centrifuged at 5,000 g for 15 min. The absorbance of the supernatant at 425 nm was determined, then the curcumin concentration was calculated using a standard curve. The encapsulation efficiency of curcumin was calculated as follows:

$ \mathrm{Encapsulation\ ef ficiency}\; (\text{%})=\dfrac{c_1}{c_2}\times100 $ (1) where, c1 is the concentration of curcumin encapsulated in the emulsion and c2 is the initial curcumin concentration in the lacquer seed oil.

Interfacial protein load

-

The surface load was determined according to previous methods[25]. Briefly, fresh emulsions were centrifuged at 35,000 g at 4 °C for 1 hour. The supernatant was then collected and filtered through a 0.45 μm filter. The amount of nonadsorbed protein remaining in the supernatant was determined using the Bradford method, and the surface load was calculated using the following equation:

$ \Gamma =\dfrac{{V}_{a}({C}_{0}-{C}_{1})}{S {V}_{oil}} = \dfrac{\left(1-\phi \right){d}_{32}}{6\varnothing }\left({C}_{0}-{C}_{1}\right) $ (2) where, Va and Voil are the volumes of the aqueous and oil phase, respectively (mL); S is the surface area of the emulsion droplets (m2); C0 and C1 are the initial LSPI concentration and nonadsorbed LSPI concentration in the aqueous phase (mg/L); and

$\varnothing $ Emulsifying properties

-

The emulsifying activity index (EAI) and emulsifying stability index (ESI) of LSPI were measured by a method described previously[26]. After homogenization, 50 μL of fresh LSPI emulsion was taken from the bottom at 0 and 10 min and diluted 100 times with a 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) solution (w/v). Then the absorbance of the diluted solution was measured at 500 nm using an ultraviolet (UV) spectrophotometer. The EAI and ESI were calculated as follows:

$ \mathrm{EAI\; }(\rm{m}^2/\rm{g})=\dfrac{2\times2.303\times A_0\times DF}{C\times\phi\times\theta\times10,000} $ (3) $ \mathrm{ESI\; }(\text{%})=\dfrac{A_{10}}{A_0}\times100 $ (4) where, DF = 100, C is the protein concentration (g/mL), Φ is the volume fraction of lacquer seed oil (10%), θ is the optical path length (1 cm), and A0 and A10 represent the absorbance values at 0 and 10 min, respectively.

Retention rates of LSPI-stabilized curcumin emulsions

-

To determine the retention rate of curcumin emulsions, all emulsions were stored in an incubator at 55 °C for 12 d, and samples were taken at 0, 3, 6, 9, and 12 d for testing. The retention rates of curcumin were calculated as follows:

$ Retention\;rate\;\left({\text{%}}\right)=\dfrac{{c}_{2}}{{c}_{1}}\times 100 $ (5) where, c1 is the concentration of curcumin encapsulated in the emulsion and c2 is the curcumin content in the emulsion at different sampling times during storage.

Protein and lipid oxidation assessment

Oil oxidation products

-

Hydroperoxides: The lipid hydroperoxide content was assessed following a previously described method[25]. Briefly, 0.3 mL of emulsion was mixed with 1.5 mL of iso-octane/2-propanol (2:1, v/v), vortexed, and centrifuged (3,000 rpm for 10 min). Next, 0.2 mL of the supernatant was combined with 2.8 mL of methanol/1-butanol (2:1, v/v), 50 µL of a Fe2+ solution, and 50 µL of a 3.94 M ammonium thiocyanate solution, followed by incubation in the dark for 20 min. Absorbance was recorded at 510 nm, and lipid hydroperoxide content was calculated using a cumene peroxide standard curve. The Fe2+ solution was prepared by mixing 0.132 M BaCl2 and 0.144 M FeSO4 (in 0.4 M HCl), followed by centrifugation to collect the supernatant.

Malondialdehyde (MDA): The 2-thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) assay was used to quantify MDA[27]. A 200 μL emulsion sample was mixed with 2 mL of thiobarbituric acid (TBA) reagent, composed of 15% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid and 0.375% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid in 0.25 M hydrochloric acid. The mixture was heated at 100 °C for 20 min, cooled, and centrifuged (5,000 rpm for 20 min). Absorbance was measured at 532 nm, and TBARS content was determined using a standard curve for 1,1,3,3-tetraethoxypropane.

Intrinsic fluorescence spectroscopy

-

The emission spectra of LSPI were determined in the 300–400 nm range using a fluorescence spectrometer (RF-6000, Shimadzu, Japan). In this case, the scanning speed was 600 nm/min, and the excitation wavelength was 280 nm[23].

Protein carbonyl content

-

The protein carbonyl content of emulsions was determined via a modified DNPH (2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine) colorimetric method[28]. Emulsion samples (0.1 mL) were mixed with 10 mM DNPH in 2M HCl (0.5 mL), incubated at 25 °C for 1 h, and centrifuged (10,000 g for 15 min). Pellets were washed thrice with ethanol–ethyl acetate (1:1, v/v), dissolved in 6.0 M guanidine hydrochloride, and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Absorbance was measured at 370 nm, and the carbonyl content was calculated as nmol/mg soluble LSPI.

Physical stability

Particle size

-

The particle size of emulsions diluted 1,000 times was determined at 25 °C using a Malvern particle size analyzer (Nano ZS90, Malvern, UK)[29]. Each sample was tested three times, and the run time was 18 s. Measurements were carried out using dynamic light scattering at a scattering angle of 90° with a laser wavelength of 633 nm. The refractive index of oil and the dispersant (water) were set as 1.47 and 1.33, respectively.

ζ-potential

-

The ζ-potential of emulsions diluted 1,000 times was determined at 25 °C using a Malvern particle size analyzer (Nano ZS90, Malvern, UK). Each sample was tested three times, and the run time was 18 seconds. Electrophoretic mobility was measured using electrophoretic light scattering at a detection angle of 17°, and the Smoluchowski model was used to calculate ζ-potential values.

Microstructure

-

The microstructure of the emulsion was observed using a confocal laser microscope (FV1200 CLSM, OLYMPUS, Japan) with a 60× objective[30]. Forty microliters of dye consisting of Nile Red (0.02%, w/v) and Nile Blue (0.1%, w/v) were mixed with 1 mL of the emulsion and diluted 10-fold. The stained emulsion was observed using laser excitation sources at 488 and 630 nm. The entire experiment was kept out of the light until analysis.

Digestive properties in vitro

In vitro digestive simulation system of LSPI-loaded curcumin emulsions

-

In vitro digestion of the emulsions was performed according to established protocols[31,32], with modifications to adjust the shear rate by varying the shaker's speed at different stages to better mimic physiological conditions. During the oral phase, the emulsion (6 mL) was mixed with simulated salivary fluid (SSF) (NaCl, NH4NO3, KH2PO4, and KCl; pH 7.0) and incubated at 37 °C with shaking at 80 rpm for 10 min. The resulting oral digest (10 mL) was then combined with simulated gastric fluid (SGF) (NaCl, HCl, and 3.84 U/mL pepsin; pH 2.0) and incubated at 37 °C with shaking at 40 rpm for 120 min to simulate the gastric phase. Subsequently, the gastric digest (18 mL; adjusted to pH 7.0) was mixed with simulated intestinal fluid (SIF) (54 mg/mL porcine bile salts, 150 U/mLtrypsin, and CaCl2/NaCl solution) and incubated at 37 °C with shaking at 120 rpm for 120 min to simulate the intestinal phase[33−35].

Free fatty acid release rate of LSPI-loaded curcumin emulsions

-

During simulated intestinal digestion, the pH was maintained at 7.0 using 0.1 M NaOH, with titration volumes recorded at 30-min intervals. Free fatty acid (FFA) release rates were calculated, based on NaOH consumption[24]. Although the FFA results are expressed as absolute concentrations (μmol/mL) for clarity, they can also be expressed as the percentage of theoretical total FFA release, and both representations show consistent trends.

$ \mathrm{Free\; fatty\; acid\; release\; rate\; }\left(\text{μmol/mL}\right)=\dfrac{V_{NaOH\left(t\right)}\times C_{NaOH}\times1,000}{V_{Simulated\; Intestinal\; Fluid}} $ (6) where, VNaOH(t) is the volume of the NaOH solution consumed at time t, CNaOH is the concentration of the NaOH solution (0.1 M), and VSimulated Intestinal Fluid is the volume of SIF.

Digestive stability and curcumin bioaccessibility of LSPI emulsions

-

The in vitro digestion products were centrifuged (10,000 g for 20 min) to remove the supernatant, which was then mixed with an equal volume of ethanol, vortexed to extract the curcumin, and centrifuged again. The resulting supernatant (the mixed micelle) was filtered (0.22 μm) and its absorbance was measured at 425 nm. Bioaccessibility and digestive stability were calculated using the following equations:

$ \mathrm{Bioaccessibility\; }\left(\text{%}\right)=\dfrac{C_{micelle}}{C_{initial}}\times\mathrm{ }100 $ (7) $ \mathrm{Digestive\; stability\; }\left(\text{%}\right)=\dfrac{C_{digest}}{C_{initial}}\times\mathrm{ }100 $ (8) where, C initial, C micelle, and C digest are the concentrations of curcumin in the initial emulsion, mixed micelles, and digest, respectively.

Rheological properties

-

The rheological properties of all LSPI emulsions were analyzed using a dynamic rheometer equipped with a 10 mm rough-surfaced parallel plate to prevent slippage following previous studies with slight modifications[36].

Shear Rate Scan: The apparent viscosity was recorded as the shear rate increased from 0.1 to 100 s−1 at a fixed frequency of 1 Hz.

Frequency Scan: The storage modulus (G') and loss modulus (G'') were measured over a 0–100 rad/s frequency range at a fixed stress of 10 Pa to characterize all LSPI emulsions' viscoelastic properties.

Statistical analysis

-

All experiments were conducted in triplicate, with the results expressed as the means ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Duncan's multiple-range test (p < 0.05) was applied to the data in Figs. 1−6. Graphs were generated using Origin 2019 (OriginLab, USA).

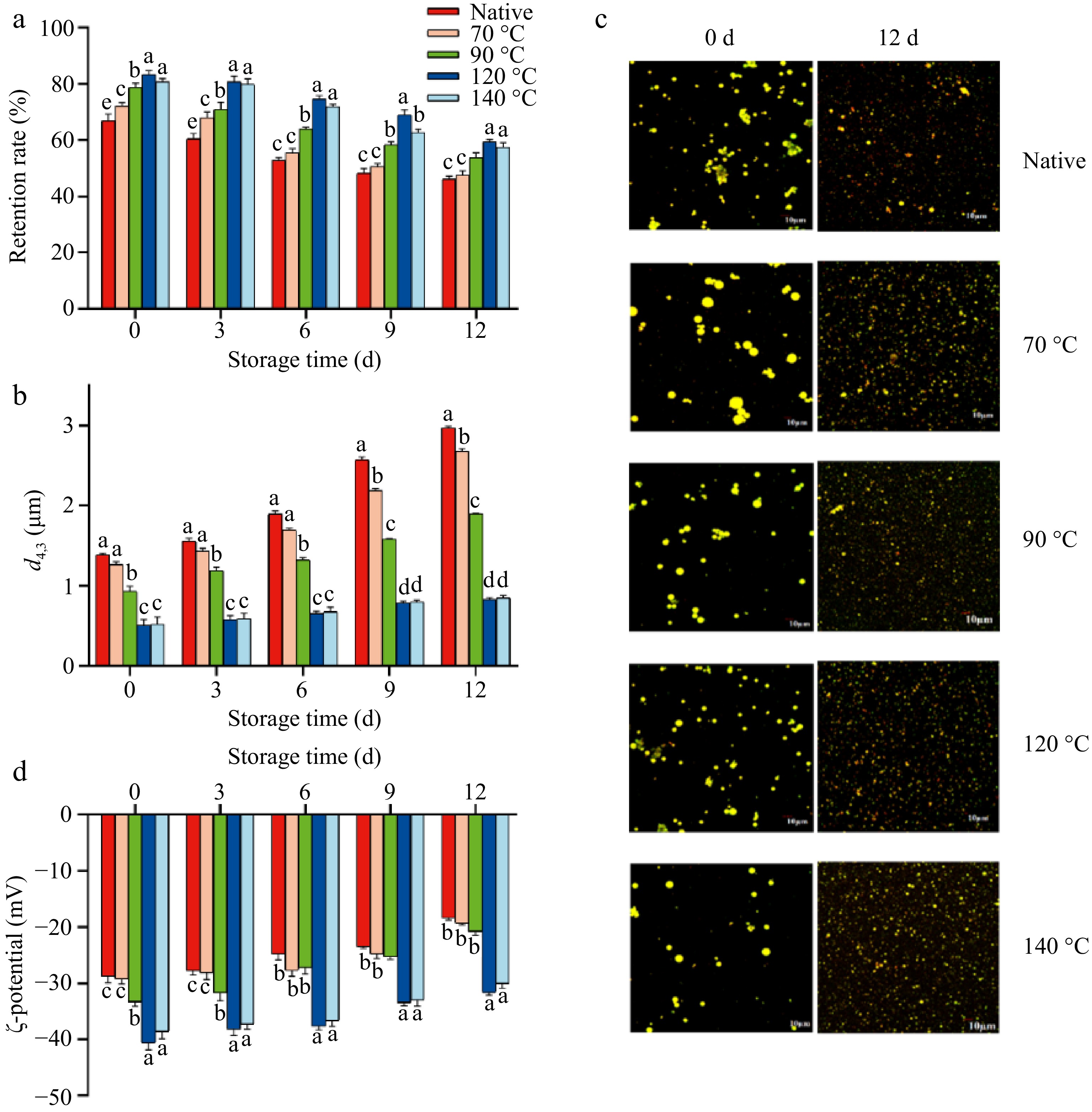

Figure 1.

(a) Appearance of curcumin emulsions stabilized by LSPI at different temperatures. (b) Loading efficiency and particle size of curcumin emulsions stabilized by heat-treated LSPI at various temperatures, including the control, LSPI-70, LSPI-90, LSPI-120, and LSPI-140 emulsions. (c) EAI, ESI, and (d) interfacial load content of the control, LSPI-70, LSPI-90, LSPI-120, and LSPI-140 emulsions. "Native" indicates the control emulsion. Samples labeled with different lowercase letters (a–d; A–C) indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among different treatments.

Figure 2.

(a) Retention rate of curcumin during storage. Changes in (b) particle size, (c) microstructure, and (d) ζ-potential of the control, LSPI-70, LSPI-90, LSPI-120, and LSPI-140 emulsions. "Native" indicates the control emulsion. Samples labeled with different lowercase letters (a–d) indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among different treatments.

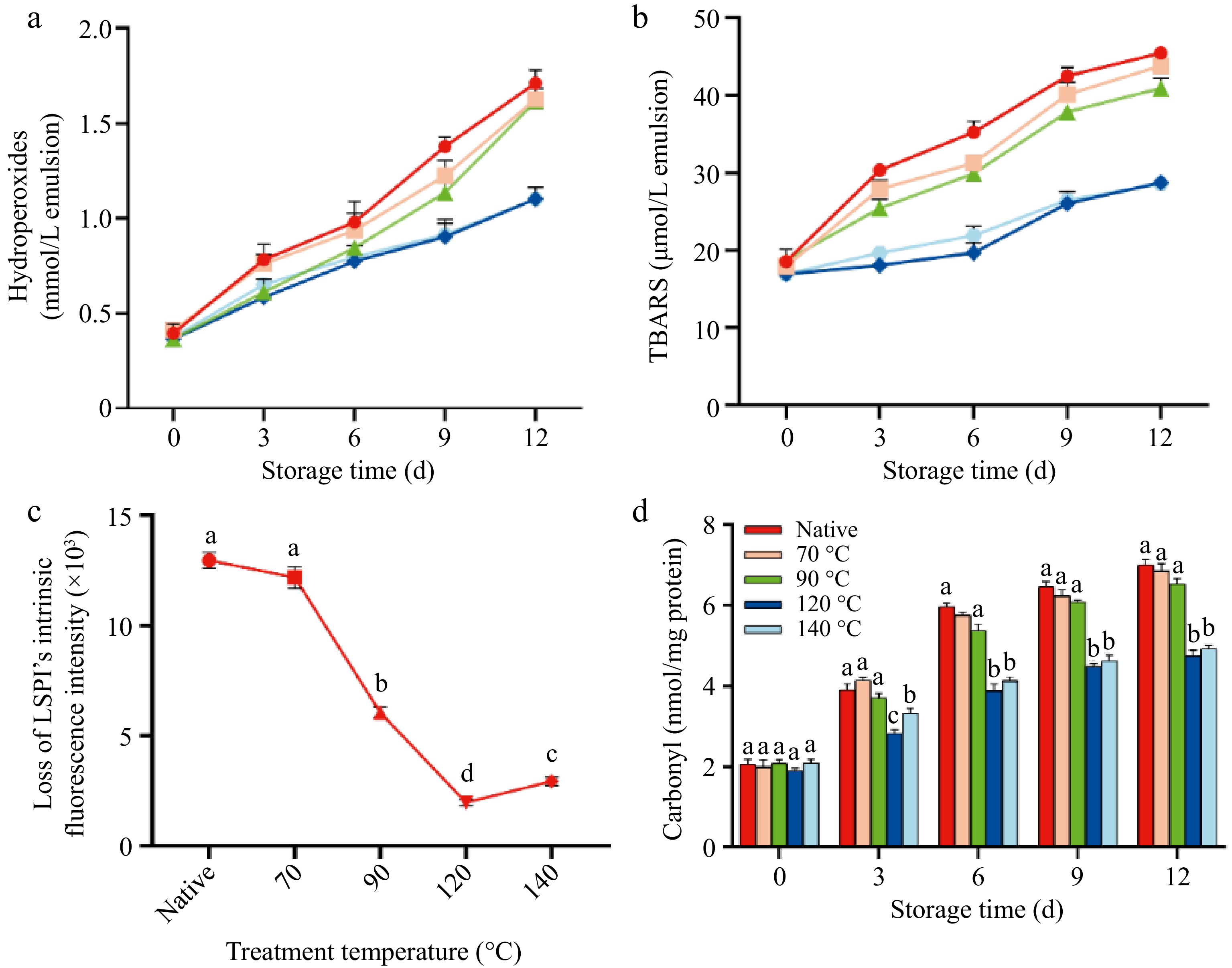

Figure 3.

Lipid–protein co-oxidation of the control, LSPI-70, LSPI-90, LSPI-120, and LSPI-140 emulsions during storage. (a) Hydroperoxide content, (b) TBARS content, (c) the intrinsic fluorescence loss, and (d) carbonyl formation of the control, LSPI-70, LSPI-90, LSPI-120, and LSPI-140 emulsions over a 12-d storage period. "Native" indicates the control emulsion. Samples labeled with different lowercase letters (a–d) indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among different treatments.

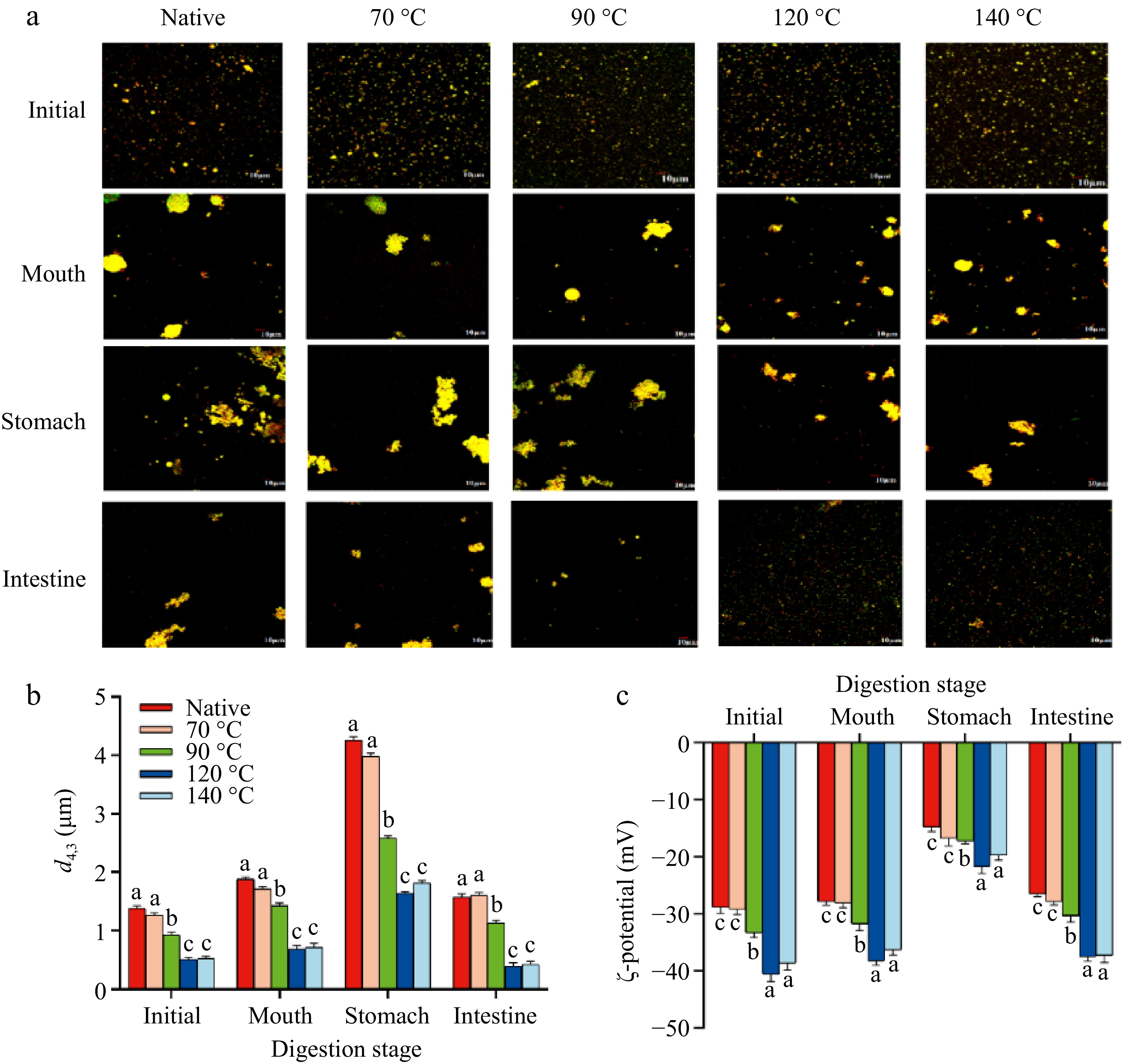

Figure 4.

Changes in (a) the microstructure, (b) particle size, and (c) ζ-potential of the control, LSPI-70, LSPI-90, LSPI-120, and LSPI-140 emulsion after oral, gastric, and intestinal digestion. "Native" indicates the control emulsion. Samples labeled with different lowercase letters (a–d) indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among different treatments.

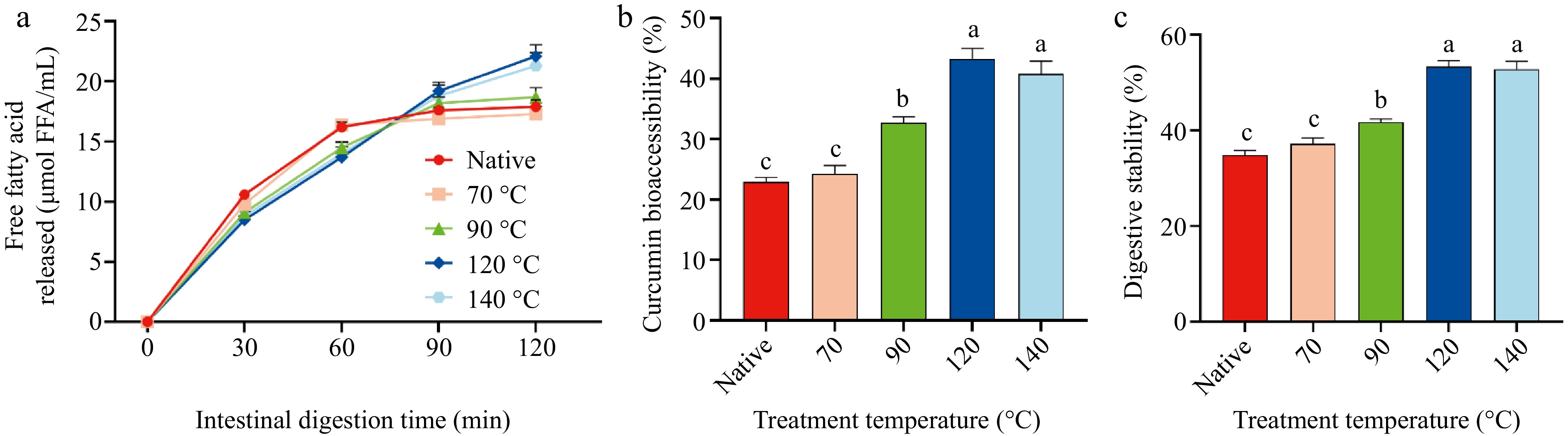

Figure 5.

Effectiveness of delivery by the control, LSPI-70, LSPI-90, LSPI-120, and LSPI-140 emulsions. (a) Changes in the release rate of free fatty acids (FFA) during simulated in vitro digestion. (b) Bioaccessibility of curcumin determined at the end of intestinal digestion (120 min). (c) Digestive stability of curcumin during simulated in vitro digestion. "Native" indicates the control emulsion. Samples labeled with different lowercase letters (a–d) indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among different treatments.

Figure 6.

(a) Apparent viscosity and (b) the effect of frequency on the G' and G'' of emulsions stabilized by LSPI at different temperatures. "Native" indicates the control emulsion. Samples labeled with different lowercase letters (a–d) indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among different treatments.

-

The encapsulation efficiency of active compounds is a pivotal indicator for evaluating the efficacy of emulsion as a delivery system[37]. As illustrated in Fig. 1a, various emulsions were prepared, including a control emulsion and LSPI-70, LSPI-90, LSPI-120, and LSPI-140 emulsions, using untreated LSPI and LSPI treated at the corresponding temperatures. Among these emulsions, the LSPI-120 and LSPI-140 emulsions exhibited a more efficient curcumin encapsulation. This improvement is mainly attributed to thermally induced structural unfolding of LSPI, which exposes hydrophobic residues and enhances protein–oil interactions, forming a denser interfacial film that effectively traps curcumin molecules within the oil droplets. As shown in Fig. 1b, the curcumin encapsulation efficiency in heat-treated LSPI-stabilized emulsions exhibited a significant increase in comparison with the control emulsion (p < 0.05). Curcumin encapsulation efficiency in the control emulsion was 69.27% ± 2.40%, whereas LSPI-120 emulsion exhibited an encapsulation efficiency that was approximately 25% higher, reaching a maximum of 90.69% ± 2.10%.

In general, a smaller oil particle size indicates the higher encapsulation efficiency of functional oil and lipophilic active molecules[38]. As shown in Fig. 1b, smaller oil droplets were observed in the LSPI-70, LSPI-90, LSPI-120, and LSPI-140 emulsions, especially the LSPI-120, and LSPI-140 emulsions. The particle sizes in the LSPI-120 and LSPI-140 emulsions were 0.51 ± 0.07 and 0.52 ± 0.09 μm, respectively, showing a significant reduction compared with the untreated group, which had 1.38 ± 0.02 μm (p < 0.05). The trend of particle size exhibited a negative correlation with the curcumin encapsulation efficiency, as indicated by a Pearson correlation coefficient of –0.9045. This inverse relationship can be explained by the fact that smaller droplets provide a larger specific surface area for protein adsorption and interfacial film formation, leading to improved droplet stabilization and more efficient entrapment of lipophilic compounds within the oil core. Conversely, larger droplets tend to coalesce more easily, resulting in leakage or partial loss of curcumin from the emulsion system[39].

The emulsifying and interfacial characteristics, including the emulsifying ability, stability, and surface protein loading, are critical factors in curcumin encapsulation efficiency. LSPI preheated at high temperatures exhibited enhanced emulsifying ability and stability compared with untreated LSPI, especially the sample treated at 120 °C. As shown in Fig. 1c, the LSPIemulsions' EAI and ESI values exhibited a temperature-dependent pattern, with a tendency to first increase and then decrease. Untreated LSPI's EAI and ESI were only 29.4 ± 1.2 m2/g and 62.1% ± 1.5%, respectively. In contrast, LPSI-120 demonstrated maximum EAI and ESI values of 52.1 ± 1.2 m2/g and 94.0% ± 0.9%, representing a 77% and 52% increase compared with untreated LSPI, respectively (p < 0.05). However, the EAI and ESI values of LSPI treated at 140 °C showed a slight but not significant decrease to 50.3 ± 0.7 m2/g and 90.0% ± 0.8%, respectively. In addition, interfacial LSPI loading demonstrated a similar trend to EAI and ESI. Figure 1d shows that LSPI's interfacial content gradually increased with rising temperature. The maximum interfacial loading of LSPI was found to be 1.63 ± 0.02 mg/m2 at the treatment temperature of 120 °C. However, a higher temperature (140 °C) led to a slight, nonsignificant decline in LSPI's surface loading, decreasing to 1.58 ± 0.01 mg/m2. The similar trends of EAI, ESI, and surface LSPI load suggest that appropriate heat treatment facilitates the migration of LSPI towards and adsorption at the oil–water interface through the protein structure. However, higher temperatures destroy the protein structure, thus slightly affecting LSPI's emulsifying and interfacial properties.

Heat treatment is frequently used to modify the functional attributes of plant proteins, such as pea protein and soy protein[17,40]. Heating could influence the protein's structure and aggregation state. High temperatures exceeding protein's denaturation temperature generally result in partial unfolding and subsequent aggregation of these unfolded proteins[17]. This structural change has been shown to generate smaller oil droplet sizes and higher interfacial protein loading in a soy protein emulsion[41]. These phenomena are consistent with the findings of our previous study, which demonstrated that LSPI produces a small amount of aggregates at 120 and 140 °C, as shown by the nonreducing SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) pattern and turbidity measurement results[10]. The formation of LSPI aggregates promoted the balance of LSPI's hydrophobic and hydrophilic groups, although excessive aggregation could destroy this balance. Consequently, 120 °C emerges as the optimal temperature for LSPI modification, enhancing LSPI's aggregation state and, in turn, boosting the interfacial properties and curcumin encapsulation efficiency.

Heating enhances the curcumin storage stability through strengthening the oil–water interface of LSPI and reducing lipid–protein–curcumin co-oxidation

-

The long-term stability of curcumin is a pivotal factor in determining its shelf life in functional foods[42]. The LSPI emulsions' oxidation stability was tested at 55 °C for 12 d, including protein oxidation, lipid oxidation, and curcumin oxidation. As demonstrated in Figs. 2 and 3, distinct degradation patterns were observed among all LSPI emulsions under extended storage conditions. The LSPI-stabilized emulsions treated at high temperatures, including the LSPI-120 and LSPI-140 emulsions, exhibited better oxidative resistance, as indicated by reduced lipid–protein–curcumin co-oxidation. Figure 2a shows that curcumin underwent severe oxidation loss in the control emulsion, with only 46.13% ± 1.10% remaining following a 12-d storage period. In contrast, emulsions stabilized by LPSI treated at high temperatures exhibited significantly higher curcumin retention rates, with 59.37% ± 0.9% and 57.38% ± 1.7% in LSPI-120 and LSPI-140 emulsions, respectively (p < 0.05). Similar phenomena were observed in the analysis of within-group differences. The 120 and 140 °C treatment groups exhibited higher stability (Supplementary Table S1). This difference indicates that LSPI, following high-temperature modification, can form an emulsion delivery system with high antioxidation ability, thus protecting curcumin from oxidation.

The physical stability of an emulsion system is a fundamental factor in ensuring the oxidation stability of curcumin. Droplet size and ζ-potential are the most common parameters used to assess an emulsion's stability. During the 12-d storage period, the De Brouckere mean diameter (d4,3) value of the LSPI-120 emulsion increased minimally from 0.51 ± 0.07 to 0.83 ± 0.02 μm, with no significant differences observed (Supplementary Table S2). In contrast, other emulsions showed severe coalescence, particularly the control emulsion, LSPI-70, and LSPI-90 emulsions, with larger d4,3 values of 2.97 ± 0.02, 2.67 ± 0.04, and 1.90 ± 0.01 μm, respectively (Fig. 2b). The change in droplet size of all LSPI emulsions was further visualized using confocal microscopy. The observed results were consistent with the changes in the d4,3 values. Initially, the control emulsions exhibited large, irregularly aggregated oil droplets, whereas the LSPI-120 and LSPI-140 emulsions displayed smaller, more uniform droplets (Fig. 2c). After 12 d of storage, the LSPI-120 emulsion maintained relatively fine and uniform oil droplets, showing only slight aggregation. In contrast, the oil droplets in other LSPI emulsions, particularly the control, LSPI-70, and LSPI-90 emulsions, exhibited pronounced coalescence and droplet enlargement. The coalescence of an emulsion means that the LSPI interface layer was damaged during 12 d of storage, leading to leakage and the subsequent aggregation of the oil phase. Once the oil phase leaks, curcumin will be exposed to more oxygen, resulting in oxidation loss and less retention[39].

Changes in the ζ-potential are also indicative of the physical stability of LSPI emulsions. Generally, a higher absolute ζ-potential value (e.g., |ζ| > 30 mV) indicates stronger electrostatic repulsion among oil droplets[43]. Among the fresh LSPI emulsions, LSPI-120 emulsion exhibited an initial ζ-potential of –40.63 ± 1.22 mV, representing a 41% increase compared with the control emulsion (–28.80 ± 1.11 mV; p < 0.05; Fig. 2d). The observed difference in ζ-potential was attributed to LSPI's structural changes induced by heating, thus affecting the balance between hydrophobic and hydrophilic groups. The decline in ζ-potential means a stronger electrostatic repulsion between oil droplets in the LSPI-120 emulsion. However, the ζ-potential values of all LSPI emulsions increased to varying degrees during storage (Fig. 2d). The LSPI-120 emulsion's ζ-potential value rose by approximately 9 mV after 12 d of storage, with a value of –31.67 ± 0.45 mV (p < 0.05, Supplementary Table S3). Conversely, the ζ-potential value increased to –18.40 ± 0.34 mV for the control emulsion (p < 0.05, Supplementary Table S3). These results suggest that the LSPI interface layer in the LSPI-120 emulsion experienced less damage during storage, but the LSPI interface layer in the other LSPI emulsions, especially the control emulsion, experienced more severe damage. This destruction of the interfacial layer is likely caused by the co-oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids in the lacquer seed oil and interfacial LSPI[25].

The oxidative stability of emulsions also represents a critical factor with regard to curcumin retention[44]. Lipid–protein oxidation frequently occurs in various food systems, particularly within emulsion-based formulations[45,46]. Unsaturated fatty acids are susceptible to oxidation, producing lipid oxidation products. These, in turn, are liable to attack proteins and active compounds, giving rise to lipid–protein oxidation or the degradation of curcumin[47]. Our previous study demonstrated that LPSI emulsions stabilized by heating exhibited enhanced oxidative stability, as shown by their delayed lipid and protein oxidation[10]. However, the oxidation process of lacquer seed oil, interfacial LSPI, and curcumin remains to be further elucidated. Figure 3 shows that all LSPI emulsions displayed a variable degree of lipid and protein oxidation during 12 d of storage. The control emulsion demonstrated most significant rate of oxidation, with a 295% increase in lipid hydroperoxides from 0.41 ± 0.03 to 1.62 ± 0.04 mM (p < 0.05). In contrast, the lipid hydroperoxides in the LSPI-120 emulsion increased to a lesser extent, reaching 1.10 ± 0.06 mM, which was 67.90% of the control emulsion (Fig. 3a). This reduction is consistent with literature showing that heat-treated protein-stabilized emulsions exhibit lower lipid oxidation because of their more compact interfacial film formation and inhibited free radical propagation[48]. MDA, a secondary oxidation product of lipids, gradually accumulated in the later stage (6–12 d). MDA content in the LSPI-120 emulsion rose from 16.91 ± 0.40 to 28.72 ± 0.90 μmol/mg, whereas MDA in the control emulsion increased to 45.45 ± 0.50 μmol/mg (Fig. 3b).

Protein oxidation frequently occurs concurrently with lipid oxidation in emulsion systems[49]. Amino acids, peptides, and proteins can react with lipid oxidation products, including lipid hydroperoxides and MDA, resulting in the loss of fluorescence and the formation of protein carbonyls. Interfacial LSPI oxidation in all LSPI emulsions was evaluated by analyzing the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence and carbonyl content (Fig. 3c, d). The reduced fluorescence loss and carbonyl content indicated that the heat-treated LSPI exhibited enhanced resistance to oxidation. The control group and LSPI-70 emulsion had a severe loss of intrinsic fluorescence, almost 12.95 ± 0.40 and 12.17 ± 0.30 RFU after 12 d, but the LSPI-120 emulsion only lost 1.97 ± 0.05 RFU. In addition, the carbonyl content in the control emulsion increased from 2.06 ± 0.12 to 6.99 ± 0.14 nmol/mg over 12 d, whereas the LSPI-120 emulsion exhibited a lower carbonyl content, increasing from 1.90 ± 0.06 to 4.74 ± 0.14 nmol/mg. More importantly, fluorescence loss and carbonyl formation in LSPI correlated well with the lipid hydroperoxides and TBARS content in all LSPI emulsions during storage, which suggests that lipid, protein, and curcumin oxidation occurred simultaneously. The reduction in lipid–protein co-oxidation may be attributed to the formation of a denser LSPI interface, as shown by the increased LSPI content at the oil–water interface (Fig. 1d). This denser protein layer has the capacity to reduce oxygen permeability, thereby reducing the oxidation of lipids, protein, and curcumin[50].

Heating facilitates curcumin's bioaccessibility and fatty acid release through the 'gastric shield–intestinal release' mechanism

-

Curcumin has attracted considerable attention because of its biological activities, which include antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. However, its bioactivity is limited by low oral and digestive bioavailability[51]. Dietary curcumin is partially absorbed in the small intestine, with the majority of it reaching the human colon, where curcumin interacts with gut microbes to exert its health-promoting effects[52]. Thus, it is imperative to use delivery systems that enhance curcumin's bioaccessibility, allowing more curcumin to reach human intestines. In this study, the digestive behavior of LSPI emulsions containing curcumin was assessed using simulated in vitro oral, gastric, and intestinal digestion trials. As demonstrated in Fig. 4, all LSPI emulsions exhibited significantly different digestive behavior, with LSPI-120 emulsion exhibiting optimal curcumin delivery and fatty acid release within the stomach and small intestine. The LSPI-120 emulsion protected curcumin and fatty acids within the emulsion droplets during the oral and gastric phases, then effectively releasing curcumin and fatty acids in the small intestine.

Oral phase

-

All emulsions exhibited an increase in particle size following simulated oral digestion (p < 0.05). Droplet size (d4,3 values) increased from 1.38 ± 0.04 to 1.84 ± 0.04 μm in the control emulsion, whereas the LSPI-120 and LSPI-140 emulsions showed a minor increase in d4,3 from 0.51 ± 0.04 to 0.68 ± 0.06 μm (p < 0.05). The observed increase in emulsion size in the control, LSPI-70, and LSPI-90 emulsions may be attributable to the binding of salts and ions present in saliva to the oil–water interface[53]. However, the ζ-potential values remained stable across all LSPI emulsions, suggesting that the interfacial layer of all LSPI emulsions did not disintegrate. Major disintegration of emulsions generally occurs in the stomach and small intestine, rather than within the few minutes in the oral cavity[21].

Gastric phase

-

Under acidic conditions, significant coalescence occurred in all LSPI emulsions, indicating notable destabilization of the interface (Fig. 4). However, heat treatment reduced oil droplets' coalescence, particularly in the LSPI-120 and LSPI-140 emulsions. Emulsions stabilized by heat treatment exhibited smaller oil droplets (p < 0.05), with the LSPI-120 emulsion exhibiting the smallest size (1.63 ± 0.03 μm). In contrast, the control emulsion demonstrated a d4,3 value of 4.26 ± 0.06 μm (Fig. 4a, b). The aggreggation of the emulsion in the simulated stomach environment may be attributed to the proximity of the pH (~3.0) of the gastric juice to LSPI's isoelectric point, resulting in charge reversal in the LSPI and subsequent weakening of the electrostatic repulsive force between the oil droplets[54]. Na+ in the simulated gastric juice may also shield the electrical charges of interfacial LSPI, leading to the physical instability and coalescence.

As shown in Fig. 4c, the ζ-potential values of all LSPI emulsions exhibited varying degrees of increase, approaching or falling below –20 mV. The ζ-potential of the LSPI-120 and LSPI-140 emulsions remained at −21.73 ± 1.21 and −19.67 ± 0.92 mV, respectively, whereas the control, LSPI-70, and LSPI-90 emulsions only reached a minimum potential of −17.23 ± 1.09, significantly higher than the high-temperature treatment groups (p < 0.05). However, the charge of the protein should be positive if the pH is below the protein's isoelectric point[55]. This charge contrast was also observed in other protein-stabilized emulsion systems[56]. The underlying reason may be associated with protein hydrolysis caused by pepsin, the ionic strength of the simulated gastric juice, or changes in the protein structure caused by heating.

Intestinal phase

-

The intestines are the primary site responsible for digestion and absorption, and it is expected that curcumin could reach this location in substantial quantities. Enzymatic hydrolysis in the small intestine reversed the coalescence trends that had been observed in the gastric phase, leading to progressive droplet breakdown (Fig. 4a, b). The LSPI-120 emulsion achieved the smallest oil droplets (0.39 ± 0.06 μm), which were considerably smaller than those of LSPI-140 (0.43 ± 0.05 μm) and the control emulsion (1.57 ± 0.06 μm; p < 0.05). This size reduction allows for more adequate contact between the oil droplets and pancreatin (including trypsin and lipase) and porcine bile salts, thus efficiently releasing the encapsulated oil phase and curcumin through forming mixed micelles.

The contact between oil droplets and pancreatin and/or bile salts can be demonstrated by the gradually increasing ζ-potential values of the LSPI emulsions (Fig. 4c). The increase in ζ-potential is mainly attributable to the interaction between the surface LSPI and pancreatin or porcine bile salts, whose ζ-potential values were found to be −30 to −50 mV[53]. In previous studies, enzymatic hydrolysis has been reported to reduce droplet size during the digestion of emulsions, and the adsorption of bile salts has been shown to affect ζ-potential of emulsion droplets[57,58]. Another possible reason is that the intestinal juice's pH (near 7.0) exceeded the protein's isoelectric point, thereby enhancing the LSPI's surface charge density. As shown in Fig. 4c, LSPI-120 and LSPI-140 emulsions restored their ζ-potential to –37.46 ± 0.84 and –37.28 ± 1.23 mV, respectively, whereas the control emulsion remained significantly lower at –26.47 ± 0.45 mV (p < 0.05). Microstructural analysis also confirmed the presence of smaller, more homogeneously dispersed mixed micelles in the LSPI-120 and LSPI-140 emulsions (Fig. 4a).

Following the simulated in vitro digestion, high levels of fatty acids and curcumin were released in the small intestine. Emulsions stabilized with LSPI treated with high temperatures LSPI, notably the LSPI-120 and LSPI-140 emulsions, were effective in the controlled release of fatty acids and curcumin through the gastric shield–intestinal release mechanism. During the initial phase of intestinal digestion (0–30 min), FFA release rates remained comparable across all LSPI emulsions. Within 30 to 90 min, the LSPI-90, LSPI-120 and LSPI-140 emulsions underwent a controlled release of fatty acids, reaching maximum FFA release and curcumin bioaccessibility at 120 min. In contrast, the control and LSPI-70 emulsions exhibited a marked FFA release within 30–60 min, accompanied by lower curcumin bioaccessibility (Fig. 5). As shown in Fig. 5a, the maximum FFA release rates of the control, LSPI-70, LSPI-90, LSPI-120, and LSPI-140 emulsions were 16.2 ± 0.4, 16.4 ± 0.5, 14.5 ± 0.5, 13.7 ± 0.9, and 14.0 ± 0.9 μmol/mL, respectively. After 120 min, the LSPI-120 and LSPI-140 emulsions exhibited greater FFA release, with values of 22.1 ± 1.0 and 21.3 ± 1.1 μmol/mL, respectively. In contrast, the amount of FFAs released from the control and LSPI-70 emulsions was only 17.9 ± 0.6 and 17.3 ± 0.6 μmol/mL, respectively. This delayed yet enhanced FFA release in the LSPI-120 and LSPI-140 emulsions can be attributed to the formation of a denser and more viscoelastic interfacial protein layer upon heat treatment, which initially limits lipase access and slows early hydrolysis, but progressively breaks down during intestinal digestion, thereby accelerating lipid hydrolysis and the release of curcumin at later stages[59,60].

Curcumin's bioaccessibility is strongly correlated with the digestion stability of LSPI emulsion systems. The LSPI-120 emulsion exhibited 43.29% ± 1.68% curcumin bioaccessibility, which is nearly double that of the control emulsion (22.87% ± 0.87%; p < 0.05; Figure 5b). The improved bioaccessibility of curcumin in the LSPI-120 and LSPI-140 emulsions was caused by the interfacial integrity. As shown in Fig. 5c, the LSPI-120 and LSPI-140 emulsions maintained 52%–54% digestive stability, which was significantly higher than the 35% observed in the control emulsion (p < 0.05; Fig. 5c). This suggests that high temperature optimally modifies LSPI to balance interfacial protection and digestive susceptibility, ensuring sustained micellar solubilization. Meanwhile, higher FFA release facilitated teh transfer of curcumin into mixed micelles, thus allowing it to undergo further digestion and adsorption[61].

Heating strengthens the effectiveness of curcumin delivery through increasing the viscosity and rheological attributes of LSPI emulsions

-

The controlled release of curcumin in the human digestive tract is an extremely complicated process, in which the viscosity and rheological properties of the delivery system play a pivotal role, as these properties also contribute to promoting the gastric barrier–intestinal release effect[62]. Higher viscosity in the gastric phase enhances protection against enzymatic degradation and destruction in the intestinal environmental, whereas stronger shear-thinning behavior in the intestine facilitates the breakdown of emulsion droplets and nutrient release. In this study, physiological shear conditions were simulated by controlling the shaking speeds (80 rpm for oral digestion, 40 rpm for gastric digestion, and 120 rpm for intestinal digestion)[63]. This approach ensures relevance to food digestion conditions, particularly in simulating shear-dependent digestion dynamics.

The LSPI emulsions' viscosity increased with increased treatment temperatures, and emulsions prepared by high temperature-treated LSPI had greater viscosity. The LSPI-140 emulsion's viscosity reached the highest value at 1,447 MPa·s, followed by the LSPI-120 emulsion with 1,381 MPa·s (Fig. 6a). The control emulsion exhibited the lowest viscosity, at 782 MPa·s. A similar trend was also observed in the storage modulus (G') and loss modulus (G'') of the LSPI emulsions (Fig. 6b). All LSPI emulsions exhibited a liquid-like behavior, where G'' > G', indicating a loss of elasticity and a gain in viscosity. Importantly, the G'' for the LSPI-120 emulsion was higher than that of the other LSPI emulsions, especially the control emulsion, meaning that the LSPI-120 emulsion was more viscous (or less elastic). This viscous property helps to enhance LSPI emulsions' physical stability, oxidation stability, and gastric resistance while maintaining favorable flow properties for intestinal digestion. This viscous nature resluted from the formation of a denser LSPI interface induced by high temperatures. High temperatures have the capacity to cause protein unfolding, leading to the occurrence of molecular entanglements and aggregation[17].

Furthermore, LSPI emulsions exhibited a characteristic shear-thinning behavior, as reflected by how the viscosity of all LSPI emulsions decreased with increasing shear rates in the range from 0.1 to 100 s−1 (Fig. 6a). The LSPI-120 and LSPI-140 emulsions showed more pronounced shear-thinning behavior than the control group. Shear-thinning results from interparticle entanglements and other interactions at relatively low particle volume fractions. This indicates that at high shear rates, the intermolecular forces of LSPI proteins are significantly weakened, causing the LSPI interface to become loose, thereby increasing the intestinal diffusion of oil droplets. In this instance, there was a greater degree of contact between pancreatin and interfacial LSPI or the oil phase, thus achieving lipid hydrolysis and the controlled release of curcumin[64].

-

This study demonstrates that thermal modification of LSPI markedly improves its performance as a plant-based delivery system for curcumin. Heat treatment at 120 °C was identified as the optimal condition, effectively inducing protein unfolding and modulating the aggregation behavior of LSPI. These structural changes reinforce the oil–water interfacial layer, thereby improving the efficiency of curcumin encapsulation and the storage stability of LSPI-based emulsions, while also reducing lipid–protein–curcumin co-oxidation. More importantly, LSPI' structural modifications at 120 °C give LSPI emulsions a ‘gastric shield–intestinal release’ mechanism through dynamically adjusting the emulsion's viscosity in response to different physiological environments. This mechanism enables targeted curcumin delivery, resulting in the highest bioaccessibility and fatty acid release being observed in LSPI-120 emulsion. According to the observed bioaccessibility (~43%), the LSPI-120 emulsion system could effectively deliver approximately 0.43 mg of curcumin per 1 mg of the initially encapsulated curcumin. Considering that a daily intake of 80–500 mg of bioavailable curcumin is generally required to achieve therapeutic effects, incorporating LSPI-based emulsions into functional foods could realistically meet or exceed this level through controlled formulation and repeated intake. Collectively, these findings highlight thermally engineered LSPI as a promising, sustainable plant-based carrier for lipophilic nutraceuticals, offering a scalable strategy to improve bioavailability in functional food applications without compromising stability or digestibility. In future applications, LSPI-based emulsions could be extended to encapsulate a broad range of hydrophobic nutrients, vitamins, and bioactives in functional foods or nutraceutical formulations. Their simple, solvent-free, and thermally tunable nature also makes LSPI systems highly suitable for large-scale, clean-label manufacturing and the development of next-generation plant-based delivery platforms.

This work was supported by the Guidance Fund for Technology Innovation of Shaanxi Province (2020QFY08-06) and the 2020 Team Innovation Project from the Fundamental Scientific Research Special Capital Fund of the National Universities, China (GK202001008).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: supervision: Meng YH, Han YH; investigation: Zhu WB, Gong T, Yang XY; project administration: Meng YH, Zhang CQ; data curation: Zhu WB, Yang XY; methodology: Hu CY, Shi LS; validation: Zhu WB; writing original draft: Zhu WB, Gong T; writing, review and editing: Meng YH, Hu CY. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Changes in retention rate of emulsions under different treatments during storage.

- Supplementary Table S2 Changes in particle size of emulsions under different treatments during storage.

- Supplementary Table S3 Changes in ζ-potential of emulsions under different treatments during storage.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Agricultural University, Zhejiang University and Shenyang Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu WB, Gong T, Yang XY, Zhang CQ, Hu CY, et al. 2025. Heat-treated lacquer seed protein isolate as an efficient emulsion stabilizer enhances curcumin protection and delivery via a 'gastric shield–intestinal release' mechanism. Food Innovation and Advances 4(4): 525−536 doi: 10.48130/fia-0025-0050

Heat-treated lacquer seed protein isolate as an efficient emulsion stabilizer enhances curcumin protection and delivery via a 'gastric shield–intestinal release' mechanism

- Received: 08 September 2025

- Revised: 04 November 2025

- Accepted: 05 November 2025

- Published online: 22 December 2025

Abstract: Lacquer tree seed protein isolate (LSPI) is a plant protein with high nutritional value but is often underutilized as animal feed or discarded, leading to waste. We previously showed that heat treatment is more effective than enzymatic or alkaline modification for improving LSPI's emulsifying properties. In this study, LSPI subjected to heat treatment at different temperatures was used to prepare emulsions for delivering curcumin. These emulsions protected curcumin through a ‘gastric shield–intestinal release’ mechanism, with 120 °C (LPSI-120) identified as the optimal protein treatment temperature. Emulsions stabilized by LSPI-120 achieved a maximum curcumin encapsulation efficiency of 90.7%, representing a 25% improvement over emulsions stabilized by untreated LSPI. Heat treatment strengthened the interfacial protein load, mitigating co-oxidation of lipids, protein, and curcumin during storage. As a result, LSPI-120 retained 59.4% of curcumin after 12 d, 1.28-fold higher than the untreated LSPI emulsion. Furthermore, heat-treated LSPI improved the effectiveness of delivery by reducing gastric coalescence, maintaining interfacial integrity, and increasing viscosity. LSPI-120 emulsions exhibited a 62% reduction in gastric coalescence and in viscosity up to 1,381 MPa·s, along with pronounced shear-thinning behavior under intestinal conditions. Ultimately, LSPI-120 emulsions enabled maximal free fatty acid release (22.1 μmol/mL) and curcumin bioaccessibility (43.3%). These findings demonstrate that heat-treated LSPI can serve as a sustainable and functional delivery material, simultaneously enhancing nutraceutical bioavailability and supporting agricultural by-product valorization.

-

Key words:

- Plant protein /

- Lacquer seed protein isolate /

- Emulsion /

- Curcumin encapsulation /

- Bioaccessibility