-

Ethyl carbamate (EC) is a natural product produced in fermented foods such as cheese, bread, soy sauce and alcoholic beverages[1,2]. Owing to its carcinogenic and genotoxic properties, it is categorized as a Group 2A carcinogen[3,4]. Huangjiu, known as one of the world's three ancient wines[5], is a traditional fermented alcoholic beverage in China. It is rich in amino acids, vitamins, active peptides and other biologically active ingredients[6], and thus has a vast consumer market in southeast China[7]. However, a large amount of EC is generated during the production and storage of Huangjiu[8]. As a result, it is necessary to find ways to reduce the EC content.

During the fermentation of Huangjiu, EC is mainly produced by S. cerevisiae and lactic acid bacteria (LAB) through the reaction of EC precursors, which are produced by arginine metabolism and ethanol[9]. The metabolism of arginine can be divided into urea cycle pathway[10] and the arginine deiminase (ADI) pathway[11,12]. S. cerevisiae degrades arginine into urea and ornithine via the urea cycle pathway[2,13], whereas LAB generates citrulline through the ADI pathway[14]. Urea and citrulline are the most important EC precursors[12], and reducing their contents can effectively inhibit EC production[15]. Enzymatic degradation of EC has the advantages of precision, high efficiency and environmental friendliness. Liu[16] isolated an EC enzyme from Alicyclobacillus pomorum with high salt and high ethanol tolerance, which not only reduces EC in soy sauce but also shows high activity against acrylamide, another Class 2A carcinogen in foods. In addition, Liu[17] also identified a heat- and high-acid-tolerant EC enzyme from Thermoflavimicrobium dichoditicum, which was also highly active against EC and acrylamide.

Numerous studies have revealed that mixed fermentation can diminish the EC content[18−19] and non-brewer's yeasts can produce aromatic substances such as higher alcohols, glycerols, volatile phenols, and aromatic ketones[20−21].

BTN2, encoded by Btn2p, could interact with Rhb1p, which inhibits the activity of Can1p arginine permease[22]. Knockout of BTN2 leads to the loss of arginine uptake by Can1p arginine permease, thereby preventing arginine metabolism as well as the production of urea and citrulline. In our previous study[23], it was discovered that the reduction in EC in Huangjiu through mixed fermentation was accompanied by a significant downregulation of BTN2 in S. cerevisiae. This implies that different fermentation systems may influence the transcriptional expression of BTN2, resulting in EC regulation.

Building upon our prior research, we isolated a strain of Pediococcus pentosaceus (PP) from Chinese koji provided by a Huangjiu company. This strain is among the most prevalent LAB strains in Chinese koji. Despite its ability serve as a fermenter during wine production[9], studies on PP are infrequently reported. There is also no reported research on investigating the reduction in EC content through mixed fermentation with PP. However, we found that mixed-culture fermentation of BTN2 knockout strains with PP exhibited a more favorable inhibitory effect on EC precursors[24], especially urea and citruline. Consequently, we applied a BTN2 knockout strain to different Huangjiu fermentation systems to investigate the regulation mechanism of EC and the alterations of basic qualities. Meanwhile, transcriptomic analysis was utilized to identify the key genes involved in single- and mixed-culture systems. Herein, we aim to provide novel perspectives for reducing the EC content in Huangjiu fermentation.

-

Wild-type BTN2 was obtained from Hangzhou Medical College. The BTN2 knockout strain was obtained from Shanghai Jiao Tong University. The PP used in this study was isolated from Chinese koji supplied by a Huangjiu company in Zhejiang Province. L-citrulline (> 98%), L-arginine (> 98.5%), L-ornithine (> 98%), urea (> 98%), EC (> 99%), Trizol, Avian Myeloblastosis Virus Reverse Transcriptase and SYBR® Green Premix Pro Taq HS qPCR Kit II were purchased from Sangon Biotech Corporation (Shanghai, China). Methanol and acetonitrile (HPLC grade) were obtained from China National Pharmaceutical Group Corporation (Shanghai, China).

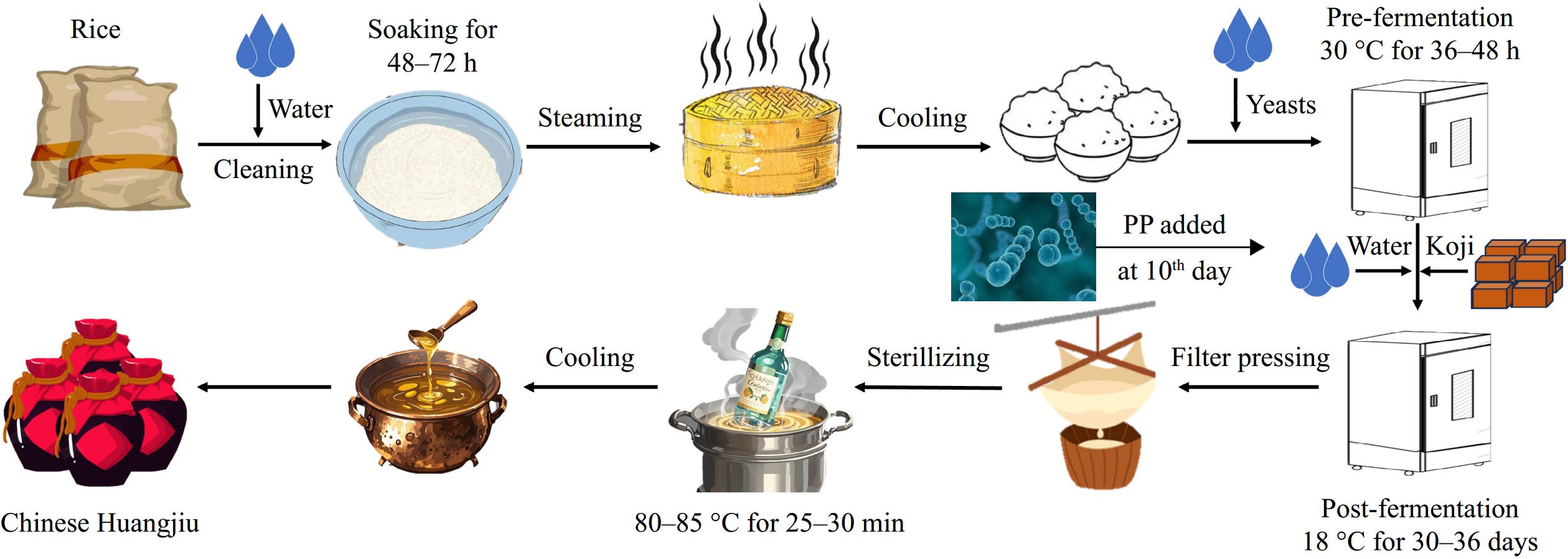

Huangjiu fermentation process

-

All three groups of Huangjiu (SC, S. cerevisiae; SK, BTN2 knockout strain; SPK, BTN2 knockout strain with PP) were produced according to the method described by Fang et al.[23] (Fig. 1). PP was added on Day 10 of fermentation.

Determination of EC, extracellular arginine, citrulline, ornithine and urea

-

EC was determined by high-performance liquid chromatograpy with fluorescence detection (HPLC-FLD)[14]. Extracellular arginine, citrulline and ornithine were detected by high-performance liquid chromatography–ultraviolet (HPLC-UV) according to the method of Li & Chen[25]. Urea was quantified following the methods of Fu et al.[4].

Key enzyme activity assays

-

The urease activity was measured using a urease assay kit purchased from Boxbio Science & Technology Corporation (Beijing, China, Catalog Number: AKNM003M). One urease unit was defined as the amount of enzyme required to catalyze the degradation of urea to 1 μmol of ammonia per minute. ADI and ornithine transcarbamoylase (OTC) activity levels were expressed as one unit of enzyme required to hydrolyze 1 μg of protein to yield 1 μmol of citrulline and ornithine per minute, respectively[26,27].

RNA extraction and transcriptome sequencing

-

In total, 50 mL of Huangjiu samples fermented for 20 d were rapidly centrifuged at 4 °C and 10,000 rpm for 5 min. Subsequently, the samples were washed with diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC) and water and centrifuged twice. The supernatant was discarded, and samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen for 15 min, then the samples were stored at −80 °C. Comparative RNA sequencing analysis was conducted by Guangzhou Magigene Co., Ltd.

The analysis system employed was the Illumina HiSeq 2500 sequencing system, and the raw data were filtered using Fastq to remove low-quality readings. Subsquently, the filtered data were compared with the reference genome GCA_003086655.1 (NCBI database) for the statistical matching ratio and the reading distribution on the reference sequence. Gene expression levels, Gene Ontology (GO) functions and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment (metabolism, etc.,) were investigated.

Verification by reverse transcription–quantitative polymerase chain reaction

-

Ten differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were selected for reverse transcription–quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) analysis, and the primers designed for this are listed in Supplementary Table S1. The mRNA expression level of genes was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCᴛ method.

Determination of the basic quality of Huangjiu

-

The amino acid concentration was determined with an automatic amino acid analyzer (L-8900; Hitachi Co., Tokyo, Japan), and volatile flavor compounds were detected by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) with mass selective detection. The ethanol content was determined according to the methods described by Zhou et al.[14]. The color variation and sugar–acid ratio of Huangjiu were measured with a colorimeter (CR400, Japan) and a refractometer (PAL-BX/ACID, Tokyo, Japan), respectively.

Statistical analysis

-

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate significant differences (p < 0.05), and Origin 2022 software was used for creating graphics.

-

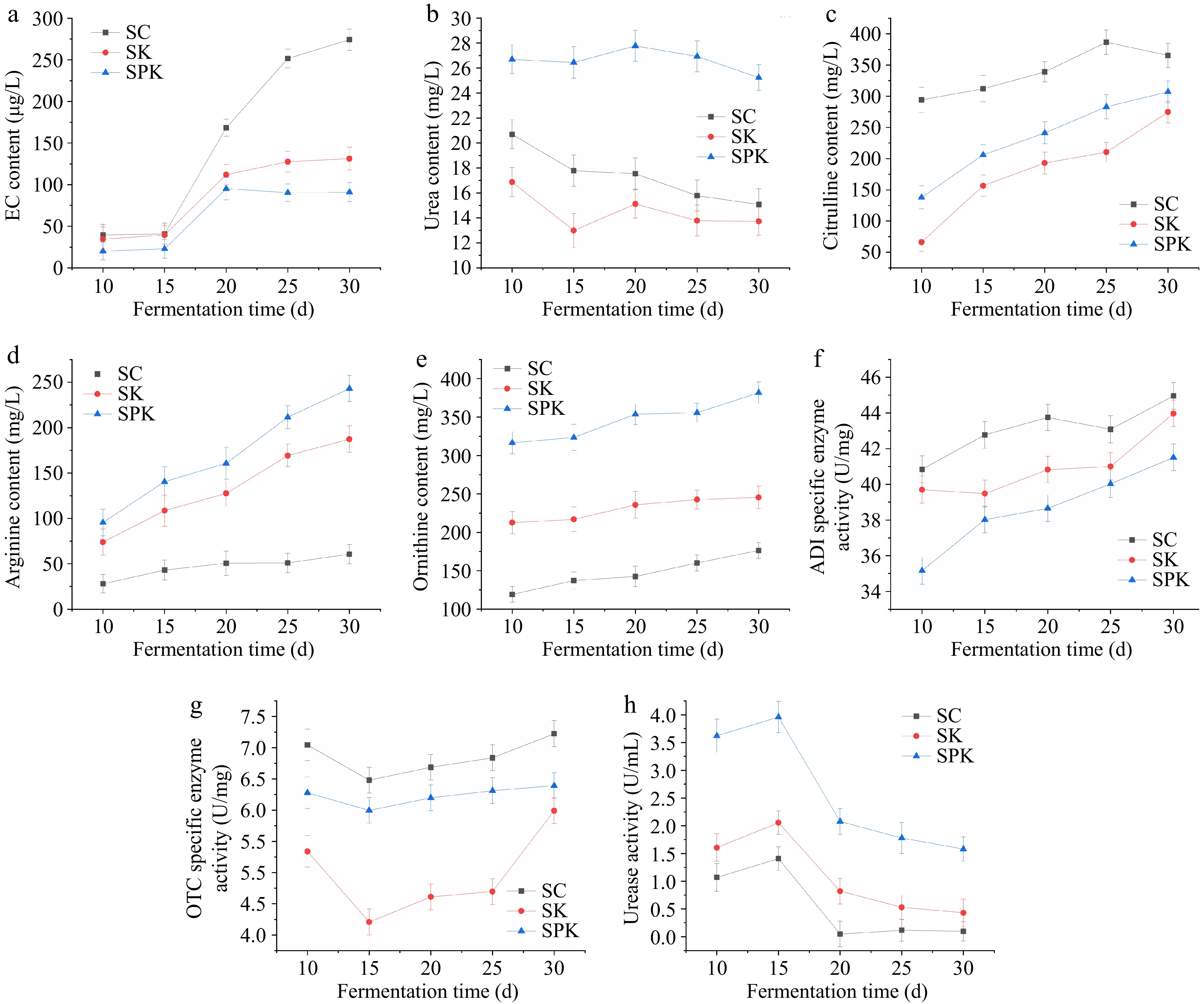

As shown in Fig. 2a, EC content displayed an upward trend throughout the fermentation period. SK and SPK exhibited lower EC content compared with control group. Notably, the SPK group exhibited the lowest and most stable EC content. Therefore, it could be concluded that the BTN2 knockout strain could effectively reduce EC, and that mixed fermentation with PP exerted a more favorable effect on reducing EC, which is consistent with previously reported research[23,24].

Figure 2.

Variation in EC, arginine-related metabolites and enzymes in the processing of Huangjiu under different fermentation systems. (a) Effect of different fermentation systems on EC formation. (b) Urea content. (c) Citrulline content. (d) Arginine content. (e) Ornithine content. (f) ADI-specific activity. (g) OTC-specific activity. (h) Urease activity. SPK, BTN2 knockout strain with PP; SC, S. cerevisiae; SK, BTN2 knockout strain.

Contributions of urea and citrulline to EC formation

-

Urea and citrulline served as the primary precursors of EC[28]. Consequently, one of the crucial approaches to eliminate EC was to regulate their generation. As shown in Fig. 2b, c, SK exhibited a lower content of urea and citrulline, resulting in reduced EC production. SPK had a higher urea content but a lower citrulline content. It was hypothesized that the pathway for EC synthesis from urea was inhibited during the fermentation of SPK, and thus EC was mainly produced by the reaction of citrulline with ethanol. This also accounted for the lower EC production in SPK.

The variations in arginine and ornithine are shown in Fig. 2d, e. The arginine and ornithine contents in SPK and SK were higher than those in SC and were on the rise, indicating that amino acids were constantly produced by cellular metabolism during the fermentation of Huangjiu. By integrating the results in Table 1 and Fig. 3, it was found that many of the upregulated DEGs in SPK and SK were associated with amino acid transport. This suggested that the knockout of BTN2 influenced amino acid transport in S. cerevisiae, which, in turn, affected the amino acid content during the fermentation of Huangjiu.

Table 1. DEGs in S. cerevisiae and their functions.

Genes Function Log2(Fold change) DEGs and their functions in SK Ard1 Predicted to enable DNA-binding transcription factor activity and RNA Polymerase II cis-regulatory region sequence-specific DNA-binding activity. 3.7122 Ntc20 Predicted to enable reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) dehydrogenase activity. Involved in NADH oxidation and glycolytic fermentation to ethanol. 3.563 Shq1 Involved in the cellular response to amino acid stimuli and transcription factor catabolic processes. Located in the inner nuclear membrane 3.3911 Erv15 Enables organic acid transmembrane transporter activity. Involved in organic acid transport. 3.3432 Mum3 Enables protein kinase activity. Involved in several processes 3.3293 Mga1 Predicted to enable DNA-binding transcription factor activity and sequence-specific DNA-binding activity. 2.909 Pex21 Enables adenosine triphosphate synthase (ATPase) activator activity and unfolded protein binding activity. 2.6193 Mud1 Enables mannosyltransferase activity. Involved in glycosylphosphatidylinisotol (GPI) anchor biosynthetic process. 2.4528 Cab1 Enables adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-dependent peptidase activity. 2.3866 Rrg8 Predicted to enable amino acid transmembrane transporter activity. 2.285 Asi2 Enables DNA-binding activity, bending and centromeric DNA-binding activity. 2.2283 Kip2 Involved in DNA repair. Located in the cytosol and nucleus. 2.1517 Rps9 Enables cyclin-dependent protein serine/threonine kinase regulator activity 2.1481 Gzf3 Enables cyclin-dependent protein serine/threonine kinase regulator activity. 2.1396 Kar1 Enables 3′–5′ DNA helicase activity and enzyme activator activity. 2.064 Yar1 Enables protein kinase inhibitor activity. Involved in fungal-type cell wall organization and negative regulation of protein kinase activity. 2.0084 Mak16 Predicted to enable oxidoreductase activity. Involved in protein targeting to membrane and protein transport into membrane rafts. 1.9673 Gar1 Predicted to enable DNA-binding activity. Involved in regulation of fungal-type cell wall biogenesis and regulation of the mitotic cell cycle. 1.9195 Osw1 Enables dicarboxylic acid transmembrane transporter activity and sulfate transmembrane transporter activity. −2.9978 Aro80 Enables protein transporter activity and unfolded protein binding activity. −2.4876 Rec104 Enables DNA secondary structure binding activity. −2.2241 Shy1 Enables cyclin-dependent protein serine/threonine kinase regulator activity. −1.5477 Bud27 Enables protein kinase activity. Involved in several processes, including DNA recombination, positive regulation of DNA-dependent DNA replication and protein phosphorylation. −1.2341 Lif1 Enables DNA replication origin binding activity and adenylate kinase activity. −1.2149 Sip4 Enables sequence-specific DNA-binding activity. −1.2094 Lam5 Enables DNA-binding transcription factor activity, RNA Polymerase II-specific activity and RNA Polymerase II cis-regulatory region sequence-specific DNA-binding activity −1.1971 Pib2 Involved in DNA recombinase assembly and maintenance of rDNA. −1.1861 Atg5 Enables RNA Polymerase I general transcription initiation factor activity. −1.165 Apl5 Enables sequence-specific DNA-binding activity. −1.1553 Vac17 Enables DNA-binding transcription factor activity. Involved in the response to xenobiotic stimulus. −1.1399 Fet3 Involved in positive regulation of transcription by RNA Polymerase II. −1.1133 Lre1 Enables DNA-binding transcription activator activity, RNA Polymerase II-specific. −1.046 DEGs and their functions in SPK Sbh1 Enables guanyl nucleotide exchange factor activity and protein transmembrane transporter activity. Contributes to protein-transporting ATPase activity. 3.0518 Utp4 Involved in maturation of small subunit (SSU) rRNA from tricistronic rRNA transcripts and positive regulation of transcription by RNA Polymerase I. 2.6671 Dpm1 Enables dolichyl-phosphate beta-D-mannosyltransferase activity. 1.5603 Gar1 Enables Box H/ACA small nucleolar (snoRNA) binding activity. 1.5532 Tif11 Enables RNA binding activity, ribosomal small subunit binding activity and translation initiation factor binding activity. 1.5054 Adk1 Enables DNA replication origin binding activity and adenylate kinase activity. 1.2293 Git1 Enables glycerol-3-phosphate transmembrane transporter activity and glycerophosphodiester transmembrane transporter activity. 1.2141 Dic1 Enables dicarboxylic acid transmembrane transporter activity. 1.1481 Egt2 Predicted to enable cellulase activity. 1.1403 Mcm4 Enables DNA replication origin binding activity and single-stranded DNA-binding activity. 1.129 Hxt6 Enables glucose transmembrane transporter activity and pentose transmembrane transporter activity. 1.1233 Mot3 Enables DNA-binding transcription factor activity 1.0971 Cin5 Enables DNA-binding transcription factor binding activity and sequence-specific DNA-binding activity. 1.0629 Kti12 Enables chromatin binding activity. 1.0457 Hop1 Enables four-way junction DNA-binding activity. −1.0204 Tah11 Enables DNA replication origin binding activity. −1.0225 Cbf2 Enables DNA-binding activity, bending and centromeric DNA-binding activity. −1.0359 Bur2 Enables cyclin-dependent protein serine/threonine kinase regulator activity. −1.0365 Lpx1 Enables triglyceride lipase activity. Involved in the triglyceride catabolic process. −1.054 Stn1 Enables single-stranded telomeric DNA-binding activity and translation elongation factor binding activity. −1.0597 Pcl10 Enables cyclin-dependent protein serine/threonine kinase regulator activity. −1.1792 Ast1 Predicted to enable oxidoreductase activity. Involved in protein targeting to the membrane and protein transport into membrane rafts. −1.1986 Rog3 Enables ubiquitin protein ligase binding activity. −1.2246 Ctf3 Involved in the initiation of DNA replication, establishment of mitotic sister chromatid cohesion and mitotic spindle assembly checkpoint signaling. −1.2298 Pga2 Involved in protein transport. Located in the endoplasmic reticulum and the nuclear envelope. −1.2993 Faa4 Enables long-chain fatty acid–coenzyme A (CoA) ligase activity. Involved in long-chain fatty acid import into the cell −1.4328 Tda6 Predicted to be involved in protein transport. Located in the cell periphery and fungal-type vacuoles −1.5558 Cyk3 Enables enzyme regulator activity. Involved in secondary cell septum biogenesis. −1.7224 Sps1 Enables protein kinase activity. Involved in several processes, including ascospore wall assembly and meiotic spindle disassembly −1.9151 In conclusion, the BTN2 knockout strain could reduce EC formation by inhibiting the precursors, and mixed fermentation with PP may inhibit the reaction between urea and ethanol, leading to reduced EC in SPK.

Comparative analysis of key enzyme activity

-

Citrulline is primarily generated by PP through the degradation of ADI[14]. Subsequently, it could be subsequently degraded to ornithine and carbamoyl phosphate by OTC. Urease could decompose to urea directly[29,30]. Therefore, it was necessary to study the activities of these key enzymes involved in the fermentation process.

As can be seen from Fig. 2f, g, the ADI activities of SK and SPK were reduced compared with the control group. This reduction would result in a greater consumption of arginine in SC, thereby generating more citrulline and EC, which is consistent with the fingdings presented in Fig. 2a, c. According to Fig. 2g, mixed fermentation could increase OTC activity. This might accounted for the lower EC content in the mixed-culture group compared with the single-culture group.

The urease activities of both SK and SPK were higher than that of SC, with SPK exhibiting the highest activity (Fig. 2h). This indicates that the BTN2 knockout strain could increase urease activity. This phenomenon may be due to the accumulation of urea stimulating an increase in urease activity.

Transcriptome analysis of S. cerevisiae in single and mixed fermentation cultures

Transcriptome analysis of S. cerevisiae in different fermentation systems

-

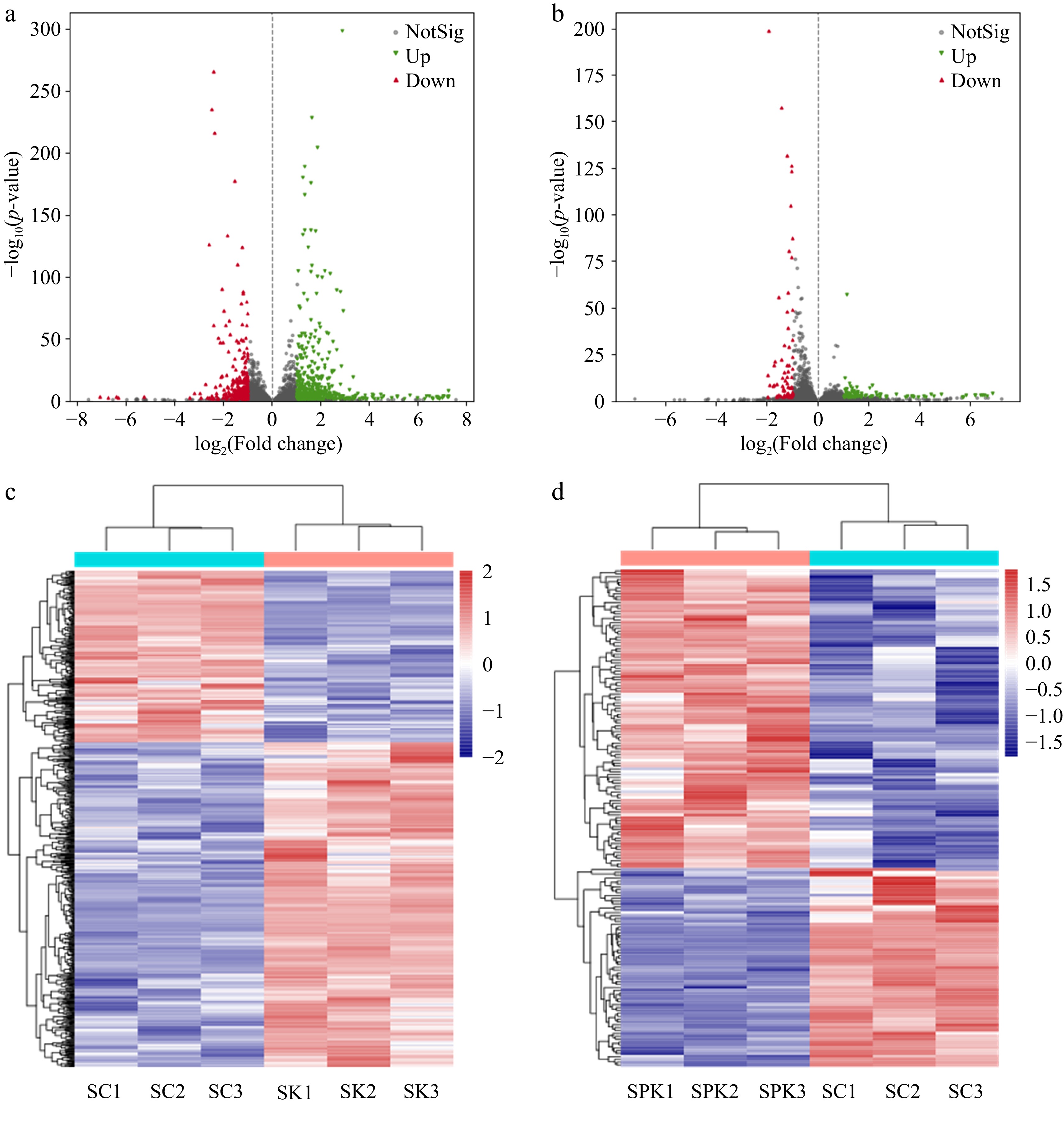

The level of difference (|log2(Fold change)| > 1) and significance level (p < 0.05) were employed to obtain the number of DEGS in Huangjiu under different fermentation systems[31]. As shown in Fig. 3, the red and green dots represented a significant decrease or increase, respectively, in the DEGs compared with the control group, and the gray points indicate nonsignificant DEGs. In total, 320 DEGs were found in the single-culture system; among these, 200 DEGs were upregulated and 120 DEGs were downregulated (Fig. 3a). Meanwhile, there were 36 upregulated DEGs and 23 downregulated DEGs during mixed-culture fermentation (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

Heatmap and volcano plot of DEGs. (a) DEGs in SK. (b) DEGs in SPK. (c) Volcano plot of DEGs in SC and SK. (d) Volcano plot of DEGs in SC and SPK. SPK, BTN2 knockout strain with PP; SK, BTN2 knockout strain.

The datasets of significant DEGs were analyzed via the DESeq2 database to gain a more in-depth understanding of how different fermentation systems affected the overall regulatory network of S. cerevisiae[32]. The activity of each transcription factor was predicted according to the number of documented targets[33], and the results are presented in Fig. 3c, d.

To better clarify the DEGs and their functions, several examples were selected and the results are shown in Table 1. A positive (negative) multiplicity of difference indicates an increase (decrease) in gene expression compared with SC.

Transcriptional profiling of S. cerevisiae in different fermentation systems

-

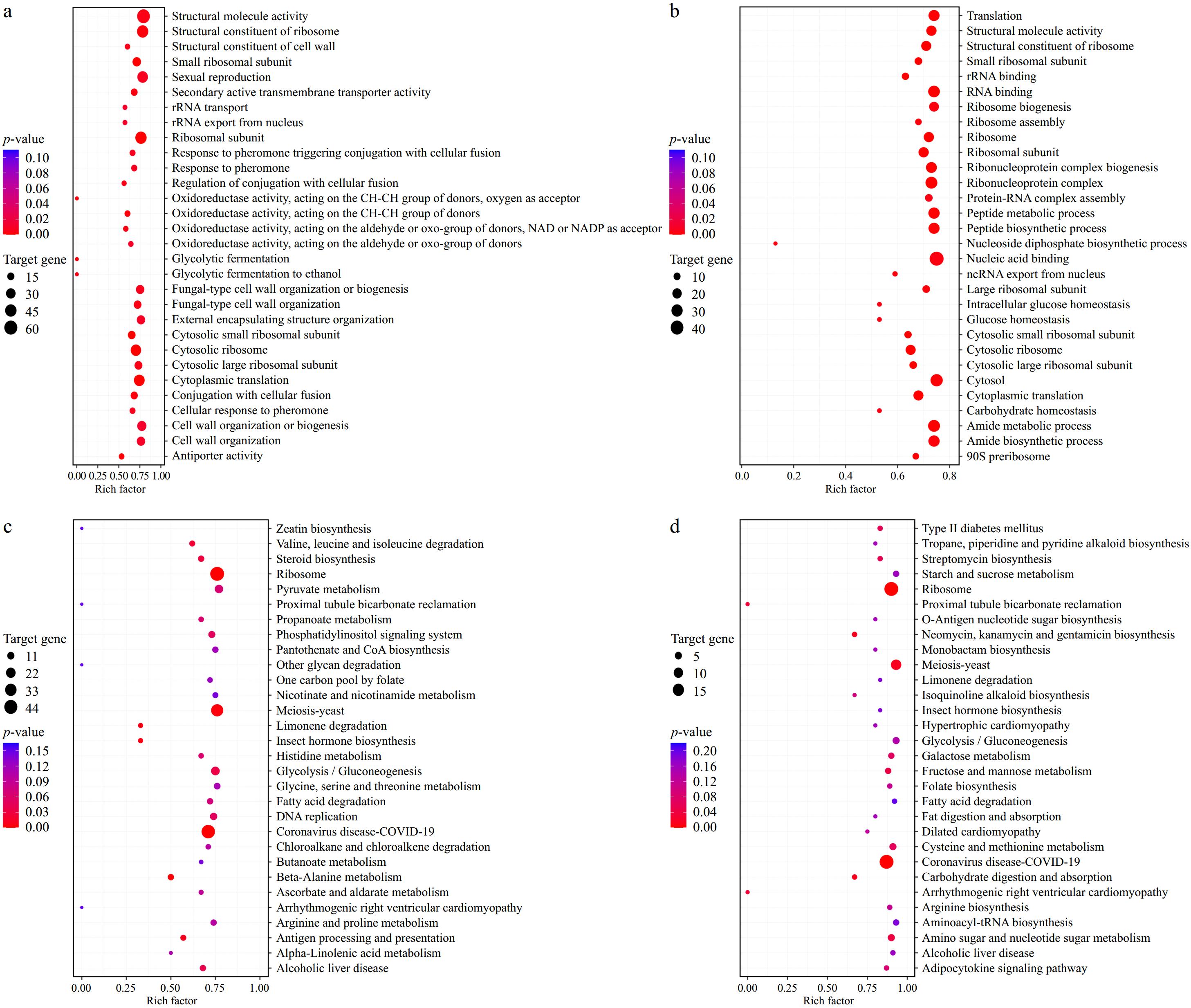

To gain a more intuitive understanding of how BTN2 knockout strains regulate the metabolic pathways of S. cerevisiae in different fermentation systems, KEGG and GO analysis were performed[34], and the results areshown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4.

GO and KEGG analysis. (a) GO analysis of SK. (b) GO analysis of SPK. (c) KEGG analysis of SK. (d) KEGG analysis of SPK. SPK, BTN2 knockout strain with PP; SK, BTN2 knockout strain.

It can be seen in Fig. 4a that the DEGs in SK were associated with 30 cell functions, which were categorized into three major parts: molecular functions, cellular components and biological processes. Fourteen molecular functions were involved, including translational regulator activity, transcriptional regulatory activity, molecular function regulator activity, etc. Fifteen functions were related to biological processes, including bio-regulation, reproductive processes and cellular processes. A substantial varity of genes related to metabolic processes, cellular processes and catalytic activities were identified. These finding implied that knockout of BTN2 exerted a significant influence on molecular functions and biological processes in S. cerevisiae.

Figure 4b indicates that the DEGs in SPK participated in a total of 25 molecular functions. Compared with the single-culture fermentation group, the genes involved in molecular functions decreased. Most genes were associated with biological processes, such as bio-regulation, cellular processes and metabolic processes. This suggested that mixed-culture fermentation has a greater impact on the biological processes of S. cerevisiae.

According to Figs 3 and 4, it was observed that a large number of genes were upregulated in both SK and SPK. Genes with an increased expression level were detected in SK, especially Prp38 (transcription), Sbh1 (folding, sorting and degradation; transport and catabolism), Nej1 (replication and repair), Pop7 (translation), Rdh54 (replication and repair), Pdc5 (carbohydrate metabolism), Izh4 (signal transduction), Leu9 (amino acid metabolism), Dib1 (transcription), Dpm1 (glycan biosynthesis and metabolism), Cab1 (metabolism of cofactors and vitamins), Hxt6 (cell growth and death), Sok2 (cell growth and death), Ccz1 (transport and catabolism) and Iqg1 (cell motility).

The following genes were identified as being upregulated in SPK: Prp38 (transcription), Sbh1 (folding, sorting and degradation; infectious disease: bacterial; transport and catabolism), Utp4 (translation), Fmp30 (nervous system), Dpm1 (glycan biosynthesis and metabolism), Adk1 (metabolism of cofactors and vitamins; nucleotide metabolism), Dic1 (excretory system), Mcm4 (cell growth and death; replication and repair), Hxt6 (cell growth and death) and Rog1 (signal transduction).

Our research concentrated on three genes, namely Lso2, Shq1, and Kti12. Lso2 is associated with DNA-binding activity. It participates in the catabolic processes of aromatic amino acids and the positive regulation of transcription by RNA polymerase II. Shq1 is involved in the cellular response to amino acid stimuli and transcription factor catabolic process. Kti12 is related to the transmembrane transport of amino acids and was predicted to be involved in amino acid transmembrane transport. All three genes are involved in amino acid transport and transcription factor expression, suggesting that BTN2 knockout affected the regulation of other transcription factors and amino acid transport, which, in turn, affected EC formation in Huangjiu.

In total, 35 identical DEGs were identified between SK and SPK, including Ard1, Csi1, Lso2, Mrx7, etc. The expression levels of these genes were dramatically upregulated in both SK and SPK, and all of them are related to the activities of protein transporters and DNA-binding transcription factors. In addition, there were eight DEGs with significant differences, namely Ast1p, Cbf2p, Pac1p, Pcl10p, Pga2p, Rog3p, Sps1p and Tda6p. Among them, Pac1p is associated with DNA-binding activity, histone-binding activity, and lipid metabolism. Sps1p is associated with lipid-binding activity, sequence-specific mRNA binding activity, and cell growth and apoptosis.

In order to verify the results of RNA-seq, 10 DEGs were selected for RT-qPCR analysis and the results areshown in Fig. 5. There are six upregulated DEGs (e.g., Lso2, Nct20 and Shq1) and three downregulated DEGs (such as Osw1, Shy1 and Sps1) in the RT-qPCR results, consistent with the results of RNA-seq. This indicates that the results of RNA-seq were reliable.

In summary, BTN2 knockout and PP significantly affected gene expression in S. cerevisiae. A large number of genes upregulated in SK and SPK were involved in multiple processes such as transcription, metabolism, and cell growth. Genes involved in molecular functions were reduced in SPK compared with SC. Most of the genes were related to biological processes, suggesting that mixed-culture fermentation had a greater impact on biological processes in S. cerevisiae, and BTN2 knockout affected the expression of genes related to amino acid transport and transcription factor metabolism, which, in turn, affected EC formation.

Effect of single- and mixed-culture fermentaion of S. cerevisiae on the basic quality of Huangjiu

Effects of single- and mixed-culture fermentaion on amino acids

-

The decomposition of proteins in the raw materials of Huangjiu could produce various free amino acids, which served as the precursors of flavor substances and are among the important criteria for evaluating the quality of Huangjiu[35].

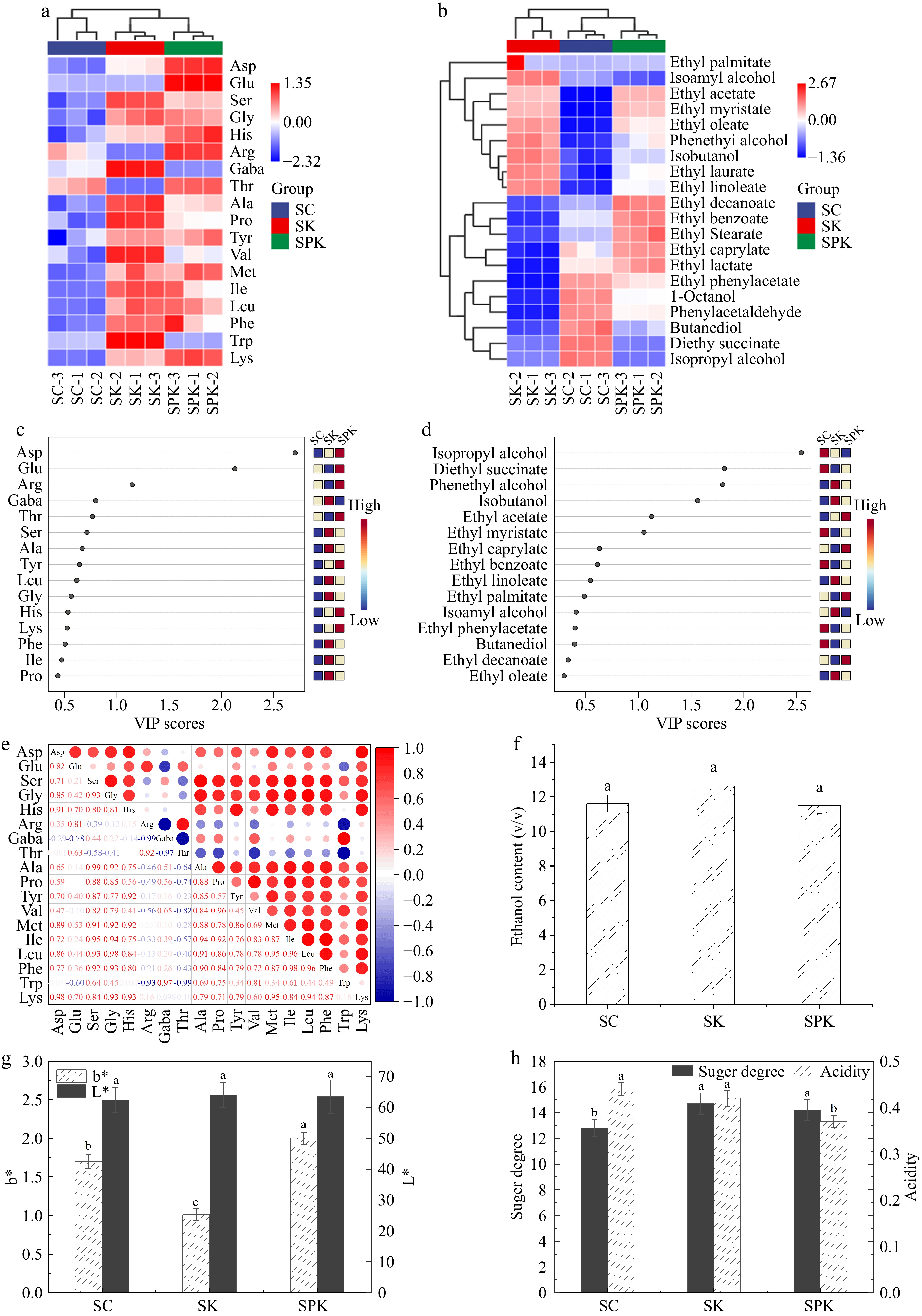

As shown in Fig. 6a, 18 free amino acids were detected. They could be classified into two categories: positively (aspartate [Asp], threonine [Thr], serine [Ser], glycine [Gly], proline [Pro], isoleucine [Ile], leucine [Leu]) and negatively (histidine [His], arginine [Arg], methionine [Met]) correlated with the flavor of Huangjiu[14]. The total amount of amino acids in SPK was greater than that in SK, indicating that mixed-culture fermentation could increase the amino acid concentration. In comparison with SC, the amount of positively correlated amino acids in SK was higher, while that of negatively correlated amino acids was reduced, implying that the BTN2 knockout strain had a positive effect on free amino acids and thus could improve the flavor of Huangjiu.

Figure 6.

Analysis of amino acids and volatile flavor substances in Huangjiu under different fermentation systems. (a) Cluster heat map analysis of free amino acids in Huangjiu. (b) variable importance inprojection (VIP) scores of free amino acids under different fermentation systems. (c) Heat map of free amino acid correlations. (d) Cluster heat map analysis of volatile flavor substances (e) VIP score of volatile flavor substances under different fermentation systems. (f) Alcohol content. (g) b* and L* values. (H) Sugar–acid ratio. SPK, BTN2 knockout strain with PP; SC, S. cerevisiae; SK, BTN2 knockout strain.

We employed the variable importance in projection (VIP) method to identify the key compounds in different Huangjiu samples[35]. Compounds with VIP > 1 can be considered as significant discriminators. Aspartic acid, glutamic acid, and arginine were key discriminators of SPK (Fig. 6b).

The correlation analysis of the amino acids is presented in Fig. 6c. Most of the amino acids exhibited a high degree of correlation. The absolute values of the correlation coefficients were greater than 0.5, indicating a strong correlation among the quality indicators of free amino acids.

Effects on volatile flavor compounds

-

The flavor profile of Huangjiu is predominantly characterized by mellowness, bitterness and freshness, accompanied by acidity and sweetness[36]. In Fig. 6d, 20 volatile flavor compounds were detected, mainly consisting of alcohols and esters, with alcohols being the most abundant. Isoamyl alcohol and phenylethanol were the most dominant alcohols in the samples. SK exhibited the highest content of isoamyl alcohol and phenylethanol. Although the content of the main alcohols in SPK was lower than that in SK, the variety was more diverse, including octanol, isopropyl alcohol and isobutyl alcohol. These alcohols are also important flavor-contributing substances.

Esters were the most diverse volatile flavorings in Huangjiu[37]. The content of some esters in SK and SPK was relatively high, such as ethyl acetate, ethyl oleate, ethyl linoleate and ethyl palmitate, all of which are the main contributors to the aromatic character of Huangjiu. The VIP method was also employed to identify the key compounds in different samples. Six volatile flavor substances could be regarded as significant indicators (Fig. 6e). Among them, isopropanol, diethyl succinate and ethyl myristate were the key discriminatory compounds for SC, while phenyl ethanol and isobutanol were the dominant flavor substances for SK, and ethyl acetate was the most important flavor-contributing compound for SPK.

In conclusion, mixed-culture fermentation facilitated the formation of various volatile flavor compounds during the fermentation of Huangjiu, thereby endowing Huangjiu with a more favorable flavor.

Effect on ethanol content

-

In accordance with the methods proposed by Zhou et al.[14], the ethanol content in Huangjiu should be no less than 8% (v/v). As shown in Fig. 6f, all samples conformed to this standard. Compared with SC, the alcohol content of SK increased slightly, whereas the difference between SPK and SC was not statistically significant.

Effects on the color and sugar–acid ratio of Huangjiu

-

The color of Huangjiu is one of the most important indicators of the overall quality[36]. According to Fig. 6g, SK and SPK exhibited higher L* values, which can be attributed to the relatively high content of phenylalanine and tyrosine in these two samples. Phenylalanine and tyrosine are important color-producing amino acids that participated in the meladic reaction during the decoction process, resulting in the production of more nigrosome-like substances[38,39]. Therefore, BTN2 knockout led to the accumulation of color-producing amino acids, and mixed-culture fermentation had no significant impact on lightness. The b* values indicate the yellow–blue color tones. In Huangjiu samples, the b* value of SPK was higher than that of SK, suggesting that PP may significantly improve the yellow colour.

As depicted in Fig. 6h, the Brix values of SPK and SK were significantly higher than those of SC. Meanwhile, the acid concentration of SPK was lower than that of the single-culture fermentation samples, which was also associated with the content of free amino acids and volatile flavoring substances, as previously mentioned.

-

This study investigated the mechanism of EC regulation by the BTN2 knockout strain in different Huangjiu fermentation systems. The findings indicated that the BTN2 knockout strain could diminish the EC content by reducing EC precursors during the fermentation process. Moreover, mixed fermentation with PP could inhibit the reaction between urea and ethanol, resulting in a reduction in EC.

Transcriptomic analysis revealed that the knockout of BTN2 and the addition of PP affected the gene expression of S. cerevisiae. BTN2 knockout exerted a more substantial influence on molecular function and biological processes, while the mixed-culture fermentation had a greater effect on biological processes. The BTN2 knockout affected the regulation and amino acid transport processes of other transcription factors, thereby influencing the formation of EC. For instance, the expression of genes related to transcription factor activity and amino acid transport, such as Lso2, Shq1 and Kti12, was significantly upregulated.

Regarding the basic quality of Huangjiu, both the mixed-culture fermentation and BTN2 knockout strain could increase the amino acid content, thereby improving the flavor of Huangjiu. SK and SPK exhibited the highest lightness values, which may be attributed to the color-producing amino acids, such as phenylalanine and tyrosine.

In conclusion, this study provides a practical foundation for the regulation of EC by BTN2 in different fermentation systems. It contributes to a deeper understanding of EC's formation mechanism in Huangjiu and provides a novel strategy for reducing EC. Consequently, this study holds important theoretical value for the Huangjiu industry.

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32101912), the Science and Technology Program of State Administration for Market Regulation (2022MK163), the Leading the Charge with Open Competition program in Wenzhou (ZNF2023009) and the Basic Scientific Research Project of Zhejiang University of Science and Technology (2023JLZD009) .

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Fang R; methodology: Fang R, Hu J; writing – original draft: Fang R, Xu H; writing – review & editing: Chen T, Tang X, Xiao G, Zhou A; funding acquisition: Fang R, Tang X; software: Zhou H, Hu J; formal analysis: Zhou H, Xu H; visualization: Zhou H, Lin W, Xu H; data curation: Zhou H, Lin W; investigation: Shi C, Lin W; validation: Shi C, Hu J; Zhou A; resources: Shi C, Tang X; project administration, supervision: Chen T, Xiao G. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its supplementary files.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Primers for RT-qPCR.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Agricultural University, Zhejiang University and Shenyang Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Fang R, Zhou H, Shi C, Chen T, Hu J, et al. 2025. Regulation of ethyl carbamate by BTN2 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae during mixed-culture Huangjiu fermentation with Pediococcus pentoses. Food Innovation and Advances 4(4): 480−489 doi: 10.48130/fia-0025-0043

Regulation of ethyl carbamate by BTN2 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae during mixed-culture Huangjiu fermentation with Pediococcus pentoses

- Received: 28 March 2025

- Revised: 29 July 2025

- Accepted: 30 July 2025

- Published online: 26 November 2025

Abstract: Ethyl carbamate (EC) is a naturally occurring potential carcinogen in fermented foods. Our prior research indicated that BTN2 knockout affected arginine metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and the inhibitory effect was more pronounced in mixed cultures with Pediococcus pentoses (PP). Consequently, in this study, we investigated the potential mechanisms of EC regulation by BTN2 knockout strains in single- and mixed-culture fermentation systems in Huangjiu and determined their fundamental qualities. The findings revealed that the BTN2 knockout strain could reduce the EC content by decreasing the amount of EC precursors and that mixed fermentation with PP could impede the reaction between urea and ethanol, thereby exerting a more favorable EC abatement effect. The BTN2 knockout strain had a positive effect on free amino acids in Huangjiu, thus improving the flavor. Additionally, transcriptome analysis demonstrated that the knockout of BTN2 and the addition of PP affected gene expression levels, paticularly genes associated with transcription factor activity and amino acid transport in S. cerevisiae, which subsquently affected the metabolic pathways during the fermentation process.

-

Key words:

- Ethyl carbamate /

- Huangjiu /

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae /

- Pediococcus pentoses /

- BTN2 /

- Mixed-culture fermentation