-

Emulsions are stable dispersion systems stabilized by emulsifiers, consisting of two or more immiscible phases (usually oil and water)[1]. With appropriate formulation, they can be designed as fat substitutes for conventional fats, offering functionalities such as improved texture and calorie reduction. Emulsion systems can also be tailored to possess health-promoting properties by encapsulating active compounds. However, the complexity of the food matrix could lead to the formation of unstable emulsions and thus affect the appearance of the final product. Therefore, exploring the mechanisms of emulsion stabilization, e.g., stability under various conditions, is essential for expanding the applications of emulsions in the food industry. Conventional emulsions stabilized by surfactants have been shown to be sensitive to certain processing conditions and may give rise to safety concerns due to potential adverse effects[2]. To address these limitations, Pickering emulsions have emerged as a more advanced emulsion system, as they are capable of enhancing stability and reducing sensitivity to processing conditions. Unlike conventional emulsions, they are stabilized by the adsorption of solid particles at the oil-water interface, forming a physical barrier that can prevent droplet coalescence and Ostwald ripening[3]. Pickering particle-based stabilization not only enhances the physical stability of emulsions but also reduces reliance on conventional surfactants, making them attractive for applications in food, medicine, and cosmetics[4,5]. In recent years, the understanding of Pickering emulsions has gradually advanced, driven by progress in nanotechnology and materials science, particularly in the design and application of functional Pickering particles. For example, Pickering emulsions with tailored functions, such as controlled release and targeted delivery, could be designed by finetuning the size, shape, and surface properties of Pickering particles[6−9].

Proteins and polysaccharides, the main biopolymers in the food industry, could be used as structure-forming materials to stabilize emulsions[10,11]. Several recent studies have developed protein-polysaccharide composite particles as effective Pickering emulsifiers, such as soy protein isolate with okara dietary fibre[12]; gliadin and chitosan[13]; heating whey protein isolate with κ-carrageenan/chitosan[14]. Compared with single biopolymers, these composites offer enhanced interfacial adsorption, long-term stability, and functional tunability, making them ideal for designing emulsions with unique structural and delivery properties. They offer significant advantages over inorganic particles and synthetic surfactants in terms of health promotion, biocompatibility, and resource sustainability[15]. Ovalbumin (OVA), the primary protein component of egg white, has increasingly attracted attention in recent years. As a typical globular protein, OVA exhibits excellent emulsifying, gelation, and foaming properties, making it widely used in the food industry[16]. Moreover, OVA possesses good biocompatibility and degradability, making it increasingly relevant in the fields of biomaterials and drug delivery. Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) is a non-ionic cellulose derivative, possessing interfacial activity due to the presence of methyl (hydrophobic) and hydroxypropyl (hydrophilic) groups in its main chain[17]. HPMC also shows excellent water solubility as well as remarkable film-forming, thickening, and gelation properties, which could adsorb oil–water interfaces and simultaneously enhance the viscosity of the continuous phase, thus providing both interfacial and bulk-phase stabilization[18]. HPMC is shown to form functionalized materials, such as edible films and hydrogels, when it is combined with other natural or synthetic polymers[19,20]. Consequently, HPMC finds widespread applications in the food and pharmaceutical sectors[21].

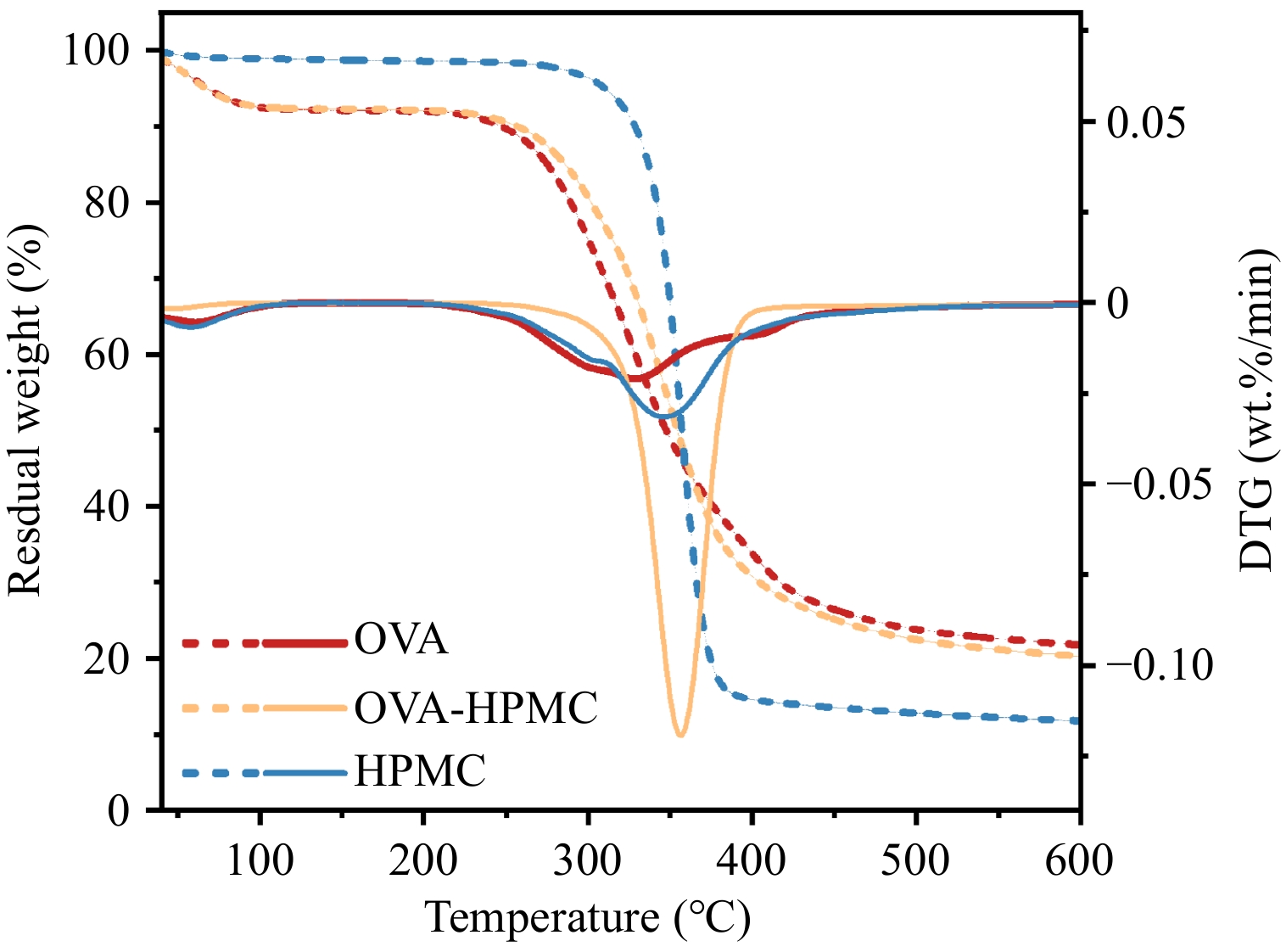

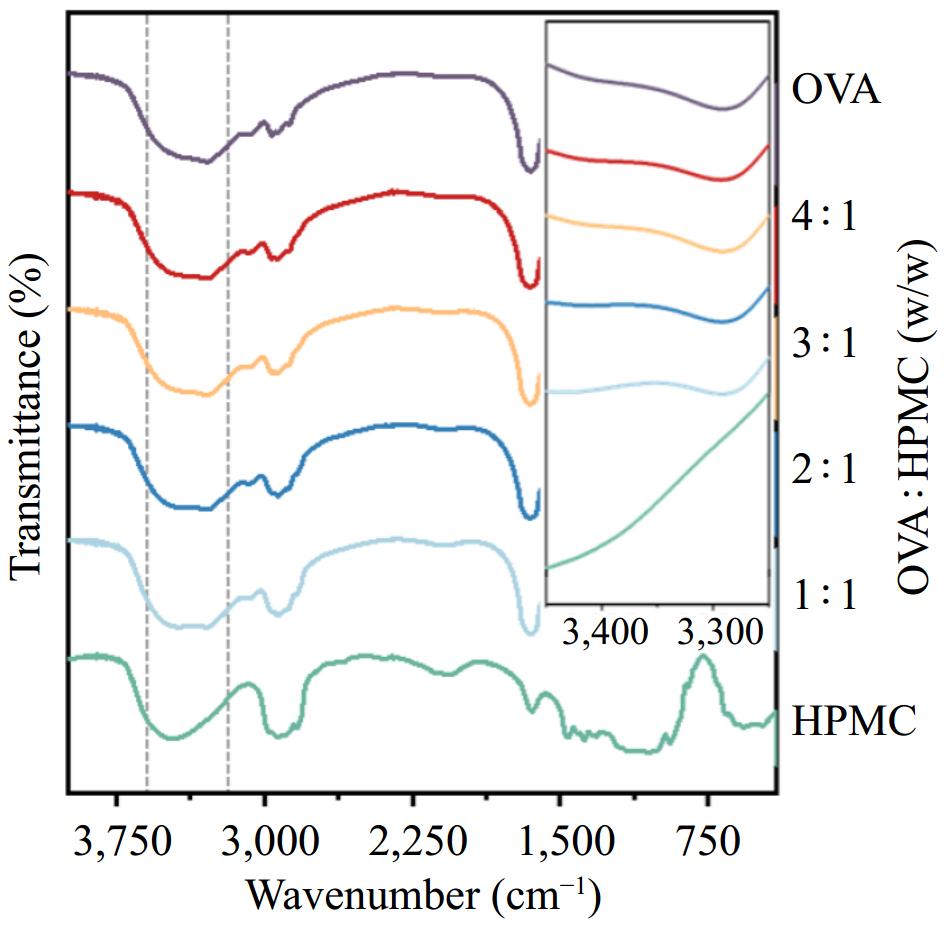

This study investigated the microstructure, macroscopic properties, and stability of OVA-based emulsions. Results showed that emulsions prepared with OVA were stabilized by its particles via the Pickering mechanism. While the addition of HPMC did not alter the stabilization mechanism at the oil-water interface, it significantly influenced the bulk-phase structure of the emulsion. In emulsions prepared with pure OVA, the OVA particles in the water phase were loosely stacked, whereas in OVA-HPMC emulsions, the particles formed a more stable three-dimensional network in the bulk phase. In the presence of HPMC, the OVA particles imparted greater emulsion stability than those stabilized by OVA particles alone at the same oil : water ratio during storage, freeze-thaw cycles, and centrifugation. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy showed a slight increase of peak height and broadening in the 3,200–3,600 cm−1 region, indicating stronger hydrogen bonding and molecular interactions between OVA and HPMC. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) revealed that the decomposition peak at 250–450 °C shifted to higher temperatures, suggesting improved thermal stability due to OVA-HPMC interactions. Molecular docking and dynamics simulations confirmed hydrogen bonding between the HPMC molecule and Asn155 of OVA.

-

Ovalbumin (OVA, purity ≥ 98%) and sunflower seed oil were supplied from Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC, 2wt.% viscosity = 4,000 mPa·s at the temperature of 20 °C), sodium hydroxide (analytical reagent) and hydrochloric acid (analytical reagent) were obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). All other chemicals were from Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Deionized water was used throughout the experiment.

Preparation of OVA and HPMC-OVA solutions and emulsions

-

OVA (4%, w/v) original solution was prepared by dispersing the OVA powder in deionized water with stirring (400 rpm) at 25 °C for 4 h, and the mixture was stored at 4 °C for 24 h to ensure thorough hydration. Additionally, sodium azide (0.02%, w/v) was added to the OVA solution to prevent bacterial growth. HPMC (2%, w/v) original solution was prepared by dissolving HPMC in deionized water until dissolved completely. The aqueous phase was prepared based on the mass of OVA and HPMC, and OVA-HPMC mixtures (1:1, 2:1, 3:1, 4:1 w/w) were prepared to explore the effect of replacement ratios on the formation of complexes by stirring the OVA and HPMC original solutions for 1 h at 800 rpm. All solutions were stirred at 600 rpm at 90 °C for 30 min and then immersed in ice water (0–2 °C) quickly and uniformly for more than 30 min to obtain the aqueous phase.

The aqueous phase (the concentration of the OVA-HPMC mixtures = 3% w/v) and sunflower oil were sheared at 12,000 rpm using the high-speed disperser (T25, IKA, Germany) for 12 min to obtain emulsions with different oil phase volume fractions (oil : water ratio = 1:3, 1:1, 3:1 [v/v]). All the aqueous phases were individually adjusted to pH 7.0 using 0.1 M NaOH or HCl.

Contact angle measurement

-

An optical contact angle goniometer (20 AMP, DataPhysics Instruments, German) was used to explore the water-oil contact angle of all samples at room temperature (~25 °C). The diluted aqueous phase solution was coated on the slides uniformly (original solution mixtures were prepared at the weight ratio of the structuring agent and ensuring that the total concentration of the proteins and polysaccharides = 0.6% (w/v), which reduced total concentration ensures uniform dispersion, The coated slides were dried at 40 °C to prepare uniform and flat films, then immersed in a colorimetric cell filled with sunflower oil. The images of the deionized water droplets (2.0 μL) were captured by a high-speed video camera during the contact-wetting process, and the contact angle was calculated based on outline fitting by the software provided with the instrument.

Thermal properties

-

The weight degradation (TGA) and the first-derivative change of derivative thermogravimetry (DTG) of the aqueous phase contain pure OVA, OVA-HPMC complex (OVA : HPMC = 2:1 w/w), and pure HPMC (4–6 mg), which dried at 40 °C were also recorded at a heating rate of 10 °C/min from 30 to 600 °C using a thermogravimetric analyzer (Q50, TA instruments, Germany).

Microstructure observation

Optical microscope

-

The microstructure of the emulsion was observed by a microscope (IX51, Olympus Optical Co., Ltd., Japan). A drop of emulsion was first placed on a slide. Then, the coverslip was gently placed to cover the drop for observation at 10× and 20× magnification.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM)

-

The sunflower oil phase and OVA-HPMC complex in the emulsions of all samples were dyed with Nile red/Nile blue (1 mg/mL) and observed at the excitation wavelength of 488 nm and 633 nm, respectively. The fluorescence micrographs were captured using the CLSM (TCS SP8, Leica, Germany) at a magnification of 2,000×.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

-

The morphology of OVA-HPMC complexes was observed by an SEM (SU8010, Hitachi, Japan), and the morphological images were captured at the accelerating voltage (25 kV) in the low vacuum mode. For SEM observation, the freeze-dried OVA and OVA-HPMC complexes (freeze-dried with a vacuum freeze-dryer [DC801, Yamato, Japan] for 2 d) were sputtered with platinum in Argon atmosphere and set on the holder with conductive adhesive tape and coated with gold.

The morphology of the emulsions prepared with OVA and OVA-HPMC complex were observed using Cryo-scanning electron microscopy (cryo-SEM) (S3000N, Hitachi, Japan) at a magnification of 15,000×. The sample was mounted onto a specimen holder and rapidly frozen by plunging into liquid nitrogen. The frozen samples were then transferred to a cryo-preparation chamber, where they were fractured under vacuum to expose the internal microstructure. Subsequently, the samples were sputter-coated with a thin layer of platinum to enhance surface conductivity and imaging contrast.

Rheological properties

-

Rotational rheometer (MCR302, Anton Paar GmbH, Austria) equipped with a Peltier system and a 50 mm parallel aluminum plate fixture were used to determine the energy storage modulus (G') and loss modulus (G'') of the emulsions. First, the amplitude sweep tests were conducted with a frequency of 1 Hz while the strain ranged from 0.1% to 100%. Second, the frequency sweep tests were performed over the range of 0.01–10 Hz. Third, the time sweep was carried out at 1 Hz frequency, and the strain value changed at 0.01%, 200%, and 0.01% for 100, 100, and 200 s for each value. All tests were conducted at a temperature of 25 °C.

Physical stability analysis

Appearance observation

-

The sample appearances of all emulsions were photographed by a digital camera (ILCE-7M3, Sony, Japan), and the emulsion layer was measured at 0, 1, and 28 d of storage (4 °C).

Centrifugal stability

-

The centrifugal stability of the emulsion was evaluated by centrifugation at 1,500 rpm for 10 min. The creaming index (CI) was calculated using the following formula (1):

$ \mathrm{CI\ (\%)}=\frac{\mathrm{The\ height\ of\ the\ serum\ layer}}{\mathrm{The\ total\ height\ of\ the\ emulsion}}\times100\ $ (1) Freeze-thaw stability

-

The emulsion sample was frozen at –20 °C for 24 h and then thawed in the oven at the temperature of 30 °C for 4 h. The CI of the emulsions was calculated after the freeze-thaw process using the formula above.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

-

One milligram of the freeze-dried sample was mixed with 150 mg of KBr, ground to powder, and pressed into circular pieces. The spectrum of the sample was obtained by an FTIR spectrometer (Nicolet IS50, Thermo Nicolet, USA). The detection spectrum range was 400–4,000 cm−1, and the scanning number was 16. Deconvolution was performed at 1,600–1,700 cm−1 using software (Thermo Scientific OMNIC, USA) to calculate changes in protein secondary structure.

Molecular dynamics simulation

-

To further investigate the structural behavior and intermolecular interactions between heat-denatured ovalbumin (OVA) and HPMC monomers under thermal stress and cold shock, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed using the GROMACS 4.5 package. The HPMC unit structure was constructed based on the method of Li et al.[22], and force field parameters were generated using the Automated Topology Builder (ATB) under the GROMOS96 54a7 force field. The ligand partial charges were assigned using the AM1-BCC method. The OVA protein structure was obtained from the Protein Data Bank (Alphafold ID: AF-O73860-F1-v4) and preprocessed to remove water molecules and add hydrogen atoms. The OVA-HPMC complex was solvated with TIP3P water molecules and neutralized with Na+ and Cl− ions at a concentration of 0.15 M. The system underwent the steepest descent energy minimization until the maximum force dropped below 1,000 kJ/(mol·nm). Following minimization, two-step equilibration was performed: (1) NVT ensemble (constant number of particles, volume, and temperature) for 100 ps at either 363.15 or 273.15 K using the V-rescale thermostat, and (2) NPT ensemble (constant pressure, 1 atm) for 100 ps using the Parrinello-Rahman barostat. Long-range electrostatic interactions were treated with the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method, and dispersion corrections were applied to both energy and pressure to enhance convergence. The SETTLE algorithm was used to constrain water molecule geometry, while all covalent bond lengths involving hydrogen atoms were maintained using the LINCS algorithm. Production MD simulations were subsequently run for 1,000 ns (at 363.15 K) and 100 ns (at 273.15 K) using a 2 fs time step. Post-simulation analyses included the calculation of root mean square deviation (RMSD) and root mean square fluctuation (RMSF). All analyses were conducted using built-in tools in the GROMACS package, and finally, PyMol 2.6.0 (Schrödinger LLC, USA) was used for visualizing.

Statistical analysis

-

All test data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation, and the graphs were generated using Origin (OriginLab, USA) and Photoshop (Adobe, USA). Each experiment was conducted in triplicate or more. A p-value of less than 0.05 (95% confidence level) was considered statistically significant.

-

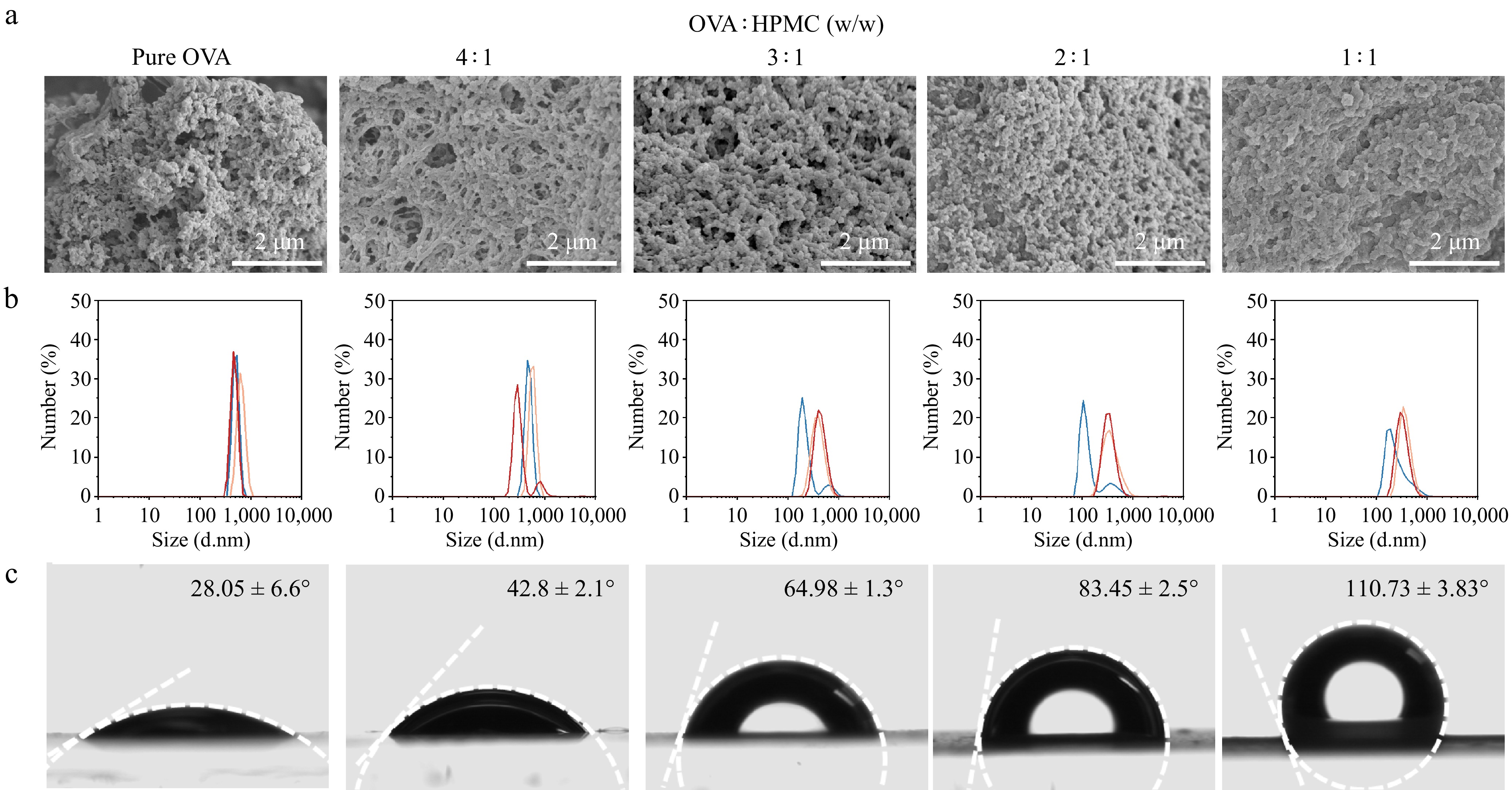

Through pre-experimental, it was found that ovalbumin (OVA) can be used to prepare Pickering emulsions, and the addition of hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) to OVA-based emulsions significantly enhances their properties. However, HPMC alone does not effectively stabilize oil-in-water (O/W) emulsions. Various experimental methods were employed to explore different HPMC replacement ratios to determine the optimal Pickering particles. Under unadjusted pH conditions, the system had a pH of 5.5. All samples were then adjusted to pH = 7 using HCl and NaOH (0.1 M). Previous studies indicate that heat-denatured ovalbumin particles exhibit a flexible chain morphology at this pH, but particles could still form with the addition of ions and precise control over preparation conditions (e.g., heating, stirring rate)[23]. The particle solutions were freeze-dried at various replacement ratios, and they were observed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Similar aggregations were observed (Fig. 1a), and as the HPMC replacement ratio increased, the polymer microstructure became more uniform and smoother. HPMC could act against protein aggregation and form a denser gel structure as non-ionic cellulose[24].

Figure 1.

Characterization of particle solutions with different HPMC-OVA ratios. (a) Scanning electron microscope (scale bar = 2 μm). (b) Particle size distribution. (c) Contact angle.

The particle size at different replacement ratios was measured three times, and the fitting curve is shown in Fig. 1b. The particle size distribution followed a normal curve, with pure protein particles ranging from 342–955 nm. As the HPMC replacement ratio increased, the size of the composite particles decreased. The smallest particle size was observed when the OVA : HPMC ratio was 1:1 (w/w), with a size range of 100–825 nm.

Finally, the contact angle at different replacement ratios was measured. As shown in Fig. 1c, the glass slide was coated with a structural agent at different replacement ratios. Finally, the contact angle was measured at different OVA-HPMC replacement ratios. As shown in Fig. 1c, OVA-HPMC solutions with various substitution ratios were evenly coated onto glass slides to form a uniform planar film, which facilitated more accurate contact angle measurements by minimizing surface irregularities and ensuring consistent droplet interaction. As the HPMC replacement ratio increased, the contact angle between the water droplet and the interface increased. When the contact angle is less than 90°, the particles are hydrophilic; when the contact angle is greater than 90°, the particles are hydrophobic. For emulsions stabilized by the Pickering mechanism, this study aims for particle hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity to be balanced, ensuring their stable presence at the interface. Additionally, since the O/W emulsion was prepared, the particle contact angle should be less than 90°[25], with values closer to 90° being preferable[26,27]. Apart from this, the zeta potential of the mixture solutions did not show much difference (Supplementary Fig. S1).

In summary, the particles prepared with the ratio of OVA : HPMC = 2:1 (w/w) showed the best properties and were selected for subsequent experiments. The emulsions with pure OVA, OVA-HPMC mixture (2:1 w/w), and pure HPMC were labeled as OVA, OH, and HPMC, respectively. The emulsions with oil : water ratio = 1:3, 1:1, 3:1 (w/w) were labeled as 25, 50, and 75, respectively.

Microstructure

-

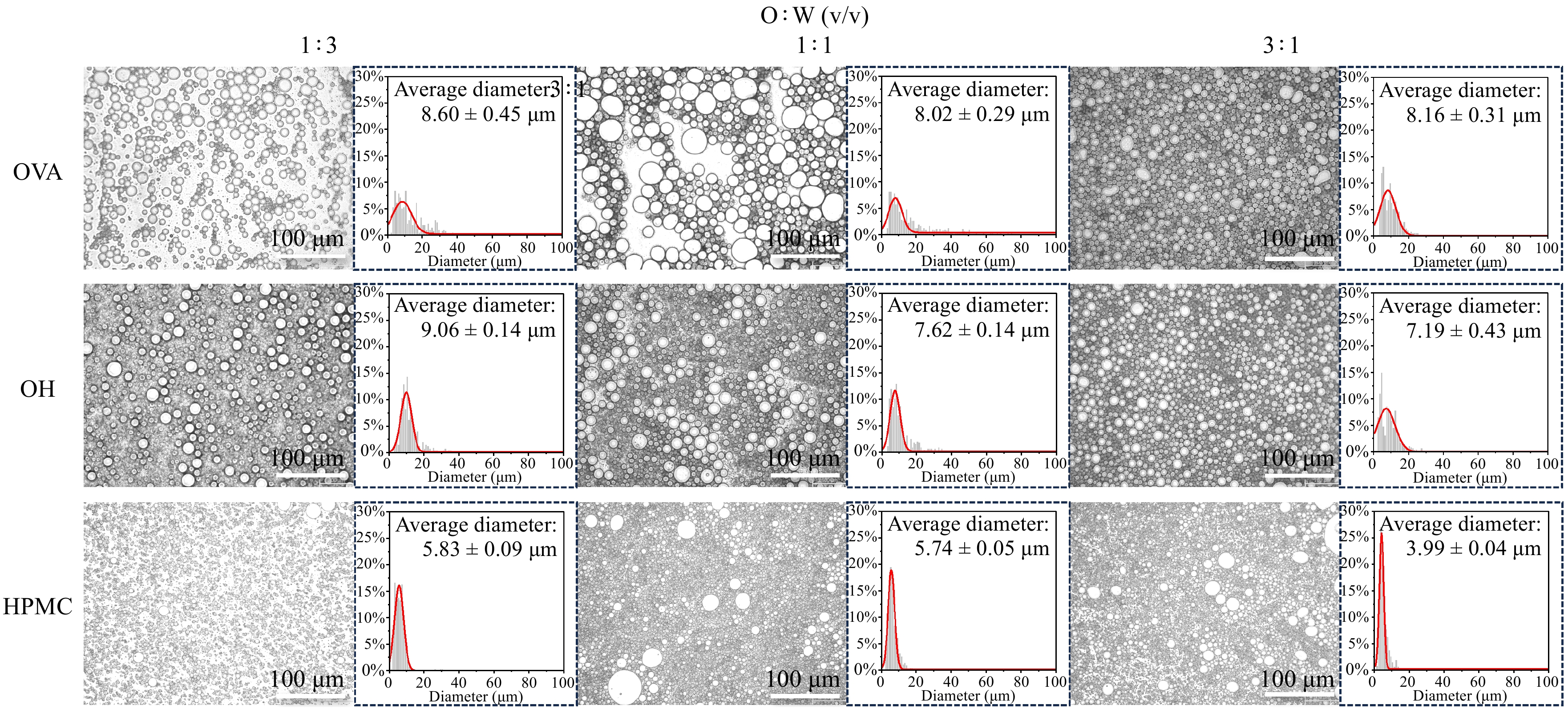

A variety of microscopes were used to observe fresh emulsions with different structuring agents and oil : water ratios. The morphology of the droplets, structuring agents, and oil-water interfaces was comprehensively explored. First, the emulsions were analyzed under the optical microscope, which clearly revealed the size distribution and dispersion state of the droplets (Fig. 2). When comparing emulsions with the same structuring agents, droplet size generally increased with the oil phase. This could be attributed to the increasing oil-water interface, which was harder to be stable at a certain concentration of structuring agents in the bulk phase[28,29]. Further comparison of emulsions with different structural agents at the same oil : water ratio showed that the particle size in OVA and OH emulsions was consistently larger than that in the HPMC group, which corresponded with the Pickering stabilization mechanism of both, where droplets are constrained by the particle diameter. Typically, the particle diameter is one order of magnitude smaller than the droplet size[30]. ImageJ (NIH, USA) was used to manually count the droplets (> 400) at the microscopic of typical emulsions, and histograms were plotted for the data. By fitting the normal distribution curve using a Gaussian function, the peak value was considered the average particle size[31]. The results show that the droplet size distribution of the OH emulsion is more concentrated and smaller than that of the OVA-based emulsion in emulsions with medium and high oil phases.

Figure 2.

Optical micrographs (scale bar = 200 μm), and droplet size distribution of emulsion with different HPMC-OVA and oil : water ratios.

Next, fluorescence microscopy was used to examine the distribution of structuring agents and emulsion types (Supplementary Fig. S2). The aqueous phase was labeled green with FITC (containing polysaccharides and proteins), while the oil phase was labeled red with Nile red[32]. It was observed that all emulsions Iwere the O/W type, with no phase inversion occurring. The droplet size observed by CLSM appeared larger, and the distribution was more uneven compared to optical microscopy (particularly in emulsions with low oil phase). The reason for droplet damage was assumed to be caused by the dyeing process. Additionally, when comparing emulsions with the same oil phase ratio but different structuring agents, it was observed that the distribution of the structuring agents in the bulk phase of OH was more dispersed compared to the OVA.

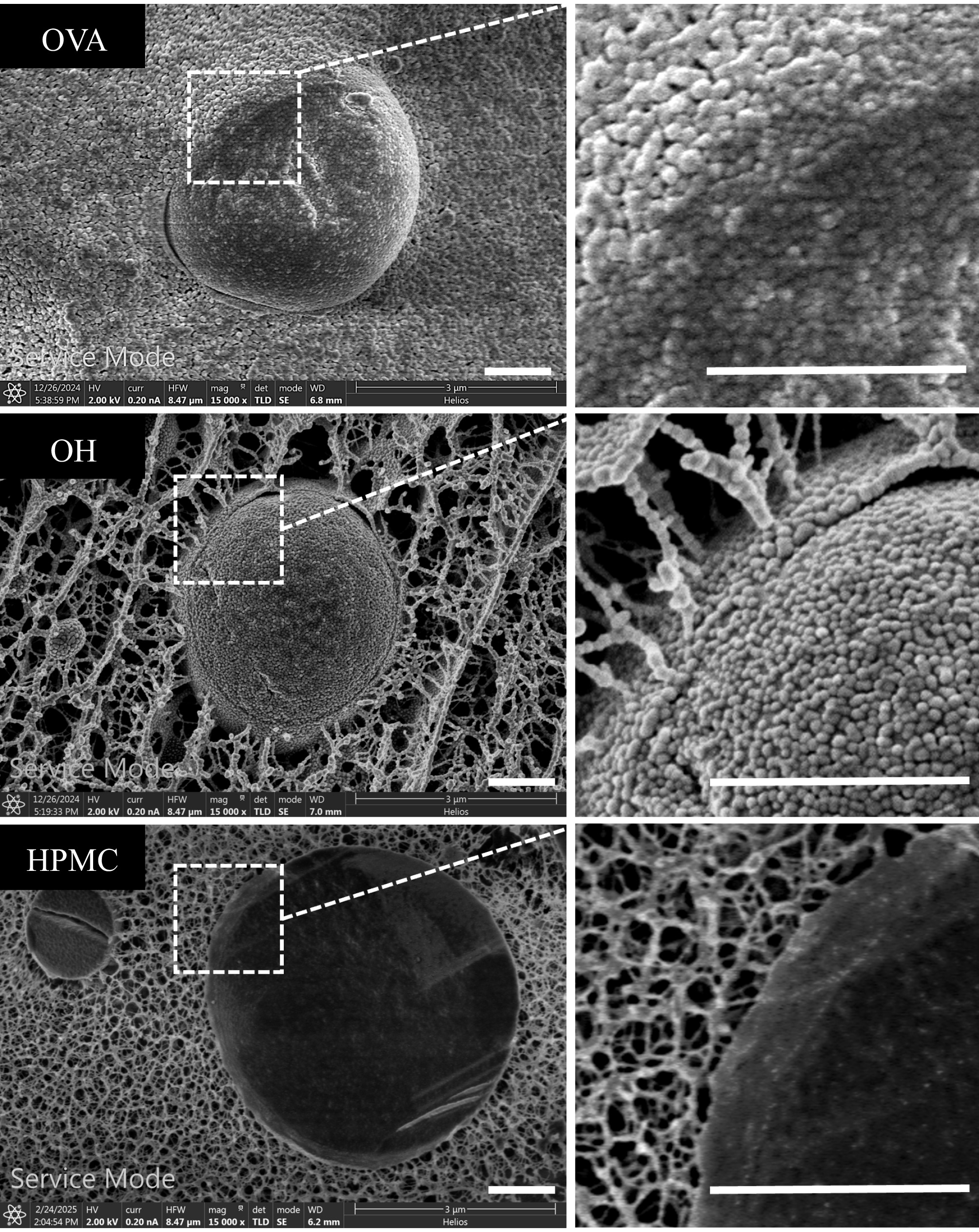

Finally, cryo-SEM was used to observe the distribution of structuring agents at the oil-water interface and in the bulk phase, with OVA50 and OH50 serving as examples. As shown in Fig. 3, the droplet surfaces were covered with particle-like structures, confirming that the droplets were stabilized by the Pickering mechanism. There was a high probability that the particle-like structure is OVA, considering the SEM images of the aqueous phase (Fig. 1a). Although their particle size was smaller than the measured particle size (Fig. 1b), this result might be due to the dispersion of aggregated particles after high-speed shearing. Further comparison of emulsions prepared with different structuring agents revealed significant differences in the distribution of the structuring agent in the bulk phase. In the OVA emulsion, the structuring agent in the bulk phase formed simple granular stacks, whereas the structuring agent in the bulk phase of OH emulsions formed the ordered 3D network structure. These findings were consistent with the CLSM micrographs, where the structuring agent in the OVA group tends to aggregate in the bulk phase, while the structuring was more evenly distributed in the OH group.

Figure 3.

Scanning electron micrographs (SEM) of bulk and surface structures in emulsions with different structuring agents (scale bar = 1 μm; using OVA50, OH50, and HPMC50 as examples).

Rheological properties

-

The rheological properties of the emulsions were evaluated to assess their macroscopic characteristics (Supplementary Fig. S3). Initially, an oscillation sweep was performed on all the emulsions to determine the linear viscoelastic region (LVR). When the elastic modulus (G') exceeds the viscous modulus (G"), the emulsion exhibits solid-like behavior. Among all the samples, only OVA75 and OH75 demonstrated solid-like behavior, while the other samples exhibited liquid-like behavior. At a strain of 10%, the G' and G" of OH75 began to decrease, indicating the material entered the nonlinear region, where the structure began to break down, and the network was irreversibly destroyed. The G' and G" intersected at the strain of 20%, signifying the transition from solid-like to liquid-like behavior. For OVA75, the decrease continues beyond a strain of 20%, with G' and G" intersecting at a strain of 100%[33].

Subsequently, frequency and time sweep were measured with the strain fixed at 0.01% to ensure that they remained in the LVR. Both OVA75 and OH75 emulsions exhibited solid-like properties. For OVA75, G' and G" remained parallel across the frequency range from 0.01–10 Hz and did not intersect, indicating that the material exhibits weak frequency dependence over the tested range, implying a relatively stable viscoelastic behavior across different time scales[34]. For OH75, G' and G" increased with the frequency increasing and eventually intersected, displaying the liquid-like properties. A three-stage time sweep was used to evaluate the structural recovery behavior related to the thixotropy of OVA75 and OH75. At low stress (0.01%), the G' of OVA75 was 660 Pa and 50.5 Pa for OH75. Under high strain (200%), the emulsion structure was destroyed, after which the modulus recovered when the stress returned to 0.01%. The recovery rate was quantified using the G' of the third stage over the G' of the first stage[35]. Both emulsions exhibited a certain thixotropic recovery, with OH75 showing a higher recovery, although the difference between the two was not significant.

Physical stability analysis

-

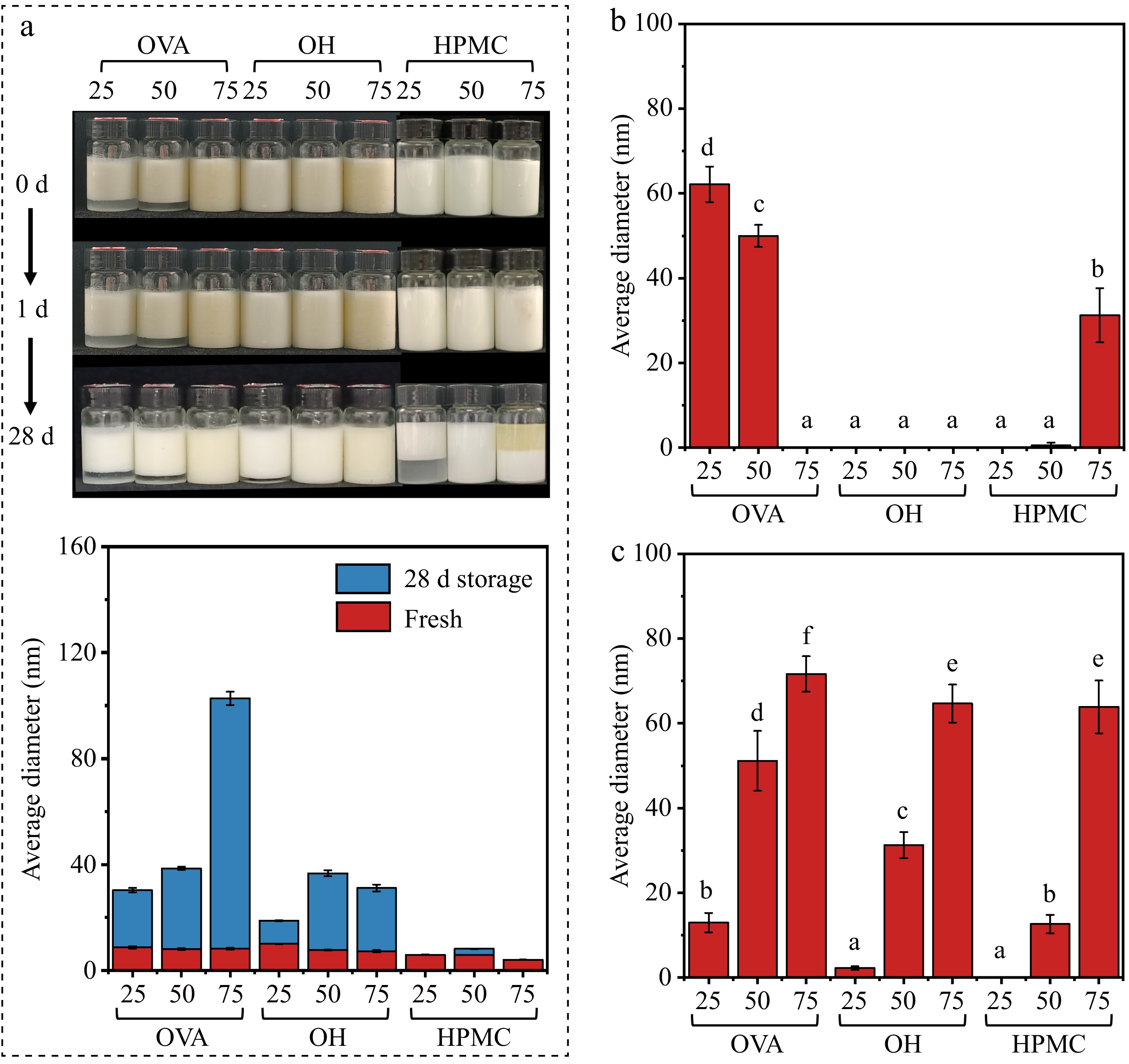

The physical stability of the emulsion was evaluated t using storage stability, freeze-thaw stability, and centrifugal stability. The storage stability (Fig. 4a) results showed that all freshly prepared emulsions exhibited a uniform appearance, except for OVA25 and OVA50. After a short storage period (1 d), the HPMC group emulsions showed phase separation. Although the visual difference in the sample bottles was not obvious because of the support of the bottle walls, significant precipitation was observed in the beakers. As storage time increased, no notable changes were observed in the OVA and OH groups. However, the instability increased in the HPMC group emulsion, with noticeable water separation in the low-oil phase, suggesting the poor hydrophilicity of HPMC, which was consistent with the increasing contact angle as the HPMC replacement ratio rose (Fig. 1c). The distinct oil separation in HPMC75 indicated that the HPMC which was used (4,000 mPa·s) fails to stabilize droplets through the Pickering mechanism as a non-gelling polysaccharide[36]. In contrast, the OVA and OH groups, which stabilize the interface through the Pickering mechanism, form an 'interface shell' that prevents droplet coalescence more effectively. This is also confirmed by the microstructure, with obvious Ostwald number ripening in HPMC (Supplementary Fig. S4)[37,38].

Figure 4.

Stability of emulsion with different HPMC-OVA and oil : water ratios. (a) Storage stability (top: photographs; bottom: changes in droplet size). (b) Freeze-thaw stability. (c) Centrifugal stability.

The freeze-thaw stability and centrifugal stability (Fig. 4b,c) were both assessed using the creaming index (CI). The freeze-thaw procedure involved storing the emulsion at 0 °C for 22 h. The purpose of this step is to form ice crystals which could pierce the interface and accelerate destabilization[39]. Similarly, centrifugation stability was tested by applying extra centrifugal forces, which also promoted emulsion destabilization. At the centrifugal stability test, OH showed the best stability, suggesting that differences in emulsion stabilization mechanisms were sufficient to produce different stabilization effects under external forces. The interfacial-network dual stabilization mechanism of OH has the highest stability compared to OVA and HPMC emulsions. However, all emulsions exhibited similar destabilization in the freeze-thaw stability test.

Thermal properties

-

Due to the vaporization of the water phase at high temperatures, which could cause the destruction of the aluminum pan, the effect of HPMC addition on the thermal stability of the OVA-based emulsion was investigated through TGA-DTG analysis of the dried aqueous phase (Fig. 5) (OVA : HPMC = 2:1 w/w). As shown in the TGA curve, the weight of the substance decreased as the temperature increased. In the 0–100 °C range, this loss was primarily due to water evaporation. The second significant weight loss occurred between 250 and 450 °C, which was typically associated with the thermal decomposition, dehydration, or volatilization of organic components. For polysaccharides, thermal decomposition reactions generally occur between 250 and 450 °C and include processes such as dehydration, de-alcoholization, and chain scission of carbohydrates. For proteins, mass loss between 250 and 450 °C is usually linked to thermal denaturation, unfolding, and further decomposition[40]. The DTG curve provided a clearer reflection of mass loss, which could be observed in the fact that the peak temperature corresponding to the OVA-HPMC complex between 250 and 450 °C is higher than that of OVA alone. This indicates that the addition of HPMC improves the thermal stability of the OVA-based emulsion, which may reflect an interaction between HPMC and OVA.

Figure 5.

Thermal properties of the dried aqueous phase contain pure OVA, OVA-HPMC complex (OVA : HPMC = 2:1 w/w), and pure HPMC.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

-

Furthermore, OVA, HPMC, and the emulsion stabilized by varying HPMC replacement ratios were dried and analyzed using FTIR spectroscopy to explore potential interactions between HPMC and OVA (Fig. 6). The region from 500–1,500 cm−1 in the mid-infrared spectrum, known as the fingerprint region, provides a unique molecular fingerprint for a specific compound[41]. By comparing the absorption peaks in this region with those of the same substance reported in the literature, the composition and structure of the sample were determined. The characteristic spectral peak of OVA was observed in the amide I band, between 1,600–1,700 cm−1, corresponding to the C = O stretching vibration of the protein, a peak closely related to its secondary structure[42]. HPMC displays typical polysaccharide vibration peaks, with an absorption peak between 950–1,050 cm−1 representing the C-O-C bridging glycosidic bond and peaks around 1,030 and 1,150–1,200 cm−1 indicative of methyl and hydroxypropyl groups, reflecting the different ratio of HPMC partial replacement[39]. To strengthen the interpretation of molecular interactions, FTIR spectra of pure OVA and pure HPMC were used as control samples and directly compared to the spectra of the mixed systems. Further analysis of the single bond region revealed spectral peaks in the 3,000–3,500 cm−1 range, corresponding to the stretching vibrations of O−H and N−H bonds. In comparison to the control spectra of pure OVA, the emulsion samples containing HPMC showed a slight increase and broadening of the peak in this region. This shift is indicative of changes in the hydrogen bonding environment, typically associated with the formation of intermolecular hydrogen bonds between hydroxyl groups of HPMC and amide or amino groups of OVA. Such spectral changes suggest that HPMC interacts with OVA through hydrogen bonding, which may influence the structure and interfacial behavior of the protein.

Figure 6.

The FTIR curve of dried emulsion stabilized with pure OVA, pure HPMC, and different ratios of OVA : HPMC (OVA : HPMC = 4:1, 3:1, 2:1, 1:1 w/w).

In silico analysis

-

The docking file was prepared following the protocol of Li et al.[22]. To save computational resources, only one repeating unit of HPMC was constructed, ensuring that all atomic groups were represented to maintain the feasibility of the results. The ovalbumin structure was retrieved from the AlphaFold Protein Database (v2.0). Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were conducted at 310.15 and 273.15 K for 1,000 and 100 ns, respectively, to simulate the interaction between the protein and the HPMC complex at elevated and low temperatures, corresponding to 90 °C and an ice-water bath. After the simulation, GROMACS 4.5 was used to analyze the results. The root mean square deviation (RMSD) is commonly used to evaluate the overall stability of the simulation process[43]. Under the simulation at 307.15 K, the RMSD of the protein changed over time (Supplementary Fig. S5a). The large fluctuation in RMSD during the early stages of the simulation indicates significant dynamic changes in the protein, while the RMSD stabilized in the later stages, suggesting that the protein's conformational changes had diminished[44]. The protein structure from the simulation was exported and re-simulated with the HPMC monomer at 217.15 K. Compared to the simulation at 310.15 K, the conformational fluctuations of the complex at the lower temperature were smaller. As the simulation progressed, the RMSD of the complex stabilized (Supplementary Fig. S5b). The root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) was also calculated to assess the degree of fluctuation of protein residues during the simulation (Supplementary Fig. S5c). The protein exhibited high RMSF values in several regions, likely due to significant fluctuations in residues located in flexible loops and regions[45]. The structure of the complex simulated at 217.15 K was exported, and hydrogen bond interactions were visualized using PyMOL (Supplementary Fig. S5d). It was observed that the O atom of the HPMC monomer formed a hydrogen bond with the aspartic acid residue at position 155 in ovalbumin. This interaction may explain how HPMC affects the distribution of ovalbumin in the bulk phase. This finding also correlates with the observed increased peak height and width in the 3,200–3,600 cm−1 region of the FTIR spectrum (Fig. 6).

-

This study investigated the incorporation of hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) into ovalbumin (OVA)-based emulsions to enhance their rheological properties and stability. Microscopic analysis confirmed that both pure OVA and the OVA-HPMC complex stabilized the oil-water interface via the Pickering mechanism. Compared to OVA-stabilized emulsions, the addition of HPMC promoted the formation of a dense three-dimensional network in the bulk phase. The OVA-HPMC complex further enhanced emulsion stability, as demonstrated by improved storage stability, freeze-thaw resistance, and tolerance to centrifugation. The emulsion stabilized by the OVA-HPMC complex exhibited significantly smaller droplet size and improved visual uniformity compared to the OVA-stabilized emulsion. Thermal analysis and FTIR spectroscopy confirmed molecular interactions between OVA and HPMC. Molecular dynamics simulations demonstrated that HPMC monomers, with hydroxypropyl and methyl functional groups, formed hydrogen bonds with Asn155 of OVA. This study provides a theoretical and technical foundation for designing protein-polysaccharide complex Pickering particles, which can stabilize functional emulsions and be applied as food emulsifiers or in drug delivery systems.

The authors would like to acknowledge the support from the Key Research and Development Program of Zhejiang Province (Grant No. 2023C02042), China.

-

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: investigation: Ma Y; data curation: Ma Y, Gu X; data analyzation: Gu X; writing − review & editing: Adhikari B, Luo Z; writing − draft manuscript preparation: Gu X; conceptualization, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition: Luo Z; figures preparation: Mao Y. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Zeta potential of particle solutions with different HPMC-OVA ratios.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM) images (scale bar = 200 μm) of emulsion with different HPMC-OVA and oil : water ratios.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 The rheological properties of emulsion with different HPMC-OVA and oil : water ratios. (a) Amplitude sweep; (b) Frequency sweep; (c) Time sweep; (d) Recovery rate.

- Supplementary Fig. S4 Optical micrographs (scale bar = 200 μm) and droplet size distribution of emulsion with different HPMC-OVA and oil : water ratios after 28 d storage (4 °C).

- Supplementary Fig. S5 MD of the HPMC monomer and OVA. (a) RMSD of the protein under 307.15 K; (b) RMSD of the complex under 217.15 K; (c) RMSF of the residues in OVA under 217.15 K; (d) Visualization of HPMC monomer and OVA interactions.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Agricultural University, Zhejiang University and Shenyang Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Ma Y, Gu X, Mao Y, Cheng Y, Adhikari B, et al. 2025. Enhancing the stability of ovalbumin-based Pickering emulsions using hydroxypropyl methylcellulose at varying ratios. Food Innovation and Advances 4(4): 471−479 doi: 10.48130/fia-0025-0037

Enhancing the stability of ovalbumin-based Pickering emulsions using hydroxypropyl methylcellulose at varying ratios

- Received: 11 March 2025

- Revised: 21 April 2025

- Accepted: 06 May 2025

- Published online: 07 November 2025

Abstract: Thermally denatured ovalbumin (OVA) was used to prepare particles for stabilizing Pickering emulsions. OVA could be partially unfolded through controlled thermal denaturation, exposing hydrophobic groups and enhancing its interfacial adsorption and emulsification ability compared to other proteins and polysaccharides. Partial replacement of OVA with hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) modulated the formation of a three-dimensional network in the continuous phase, thereby influencing the emulsion's macrostructure. Cryo-scanning electron microscopy (cryo-SEM) revealed that the oil-water interface was primarily stabilized by OVA-based Pickering particles, while the addition of HPMC transformed the bulk-phase OVA particles from a simple stacked arrangement into a more stable three-dimensional network. This transformation significantly reduced droplet size and improved the macroscopic stability of the emulsion when observed on day 29 of storage. Further analysis using FTIR and TGA revealed that interactions had occurred between OVA and HPMC, as indicated by an increased peak height and width in the 3,200–3,600 cm−1 region, as well as a DTG peak shift from 328 to 347 °C. In addition, molecular dynamics simulations and molecular docking further confirmed that hydrogen bonding had occurred between OVA and an HPMC molecule, elucidating the mechanism by which mixing OVA-HPMC ratios affected the microstructure at the molecular level. This study provides theoretical insights into the stabilization mechanism of Pickering emulsions based on protein-polysaccharide complexes.