-

Fresh-cut products have become a highly sought-after category in the retail food market in recent years, exhibiting promising growth potential due to their freshness, nutritional value, and ease of preparation[1]. Various fresh-cut products are widely available in markets, such as potatoes, carrots, cabbage, and apples, among others[2]. Compared to whole potatoes, the advent of fresh-cut potatoes offers consumers more convenience while providing a complete nutritional profile[3]. Fresh-cut potatoes are more vulnerable to changes in ambient temperature. Potatoes left at room temperature after cutting damage can lead to severe browning while losing most of their nutrients due to direct contact of the internal tissues with air[4].

It is crucial to alleviate fresh-cut potatoes' surface browning and quality deterioration. Previous research has explored many directions for storing fresh-cut potatoes, including modified atmosphere packaging (MAP), ultrasound treatment (US), ultraviolet (UV), and cold storage. Potato MAP storage in a suitable gaseous environment can effectively inhibit the propagation of spoilage bacteria, but controlling the balance of the gaseous environment in the bag is not an easy problem to solve[5]. Sweet potatoes treated with US were able to inhibit surface browning significantly, but due to differences in protein structure, the same US frequency may kill some enzymes and result in nutrient loss[6], fresh-cut potatoes were UV irradiated to kill their surface microorganisms more completely, but with loss of nutrients and increased sugar content[7]. Cold storage is the most cost-effective way of storing fresh-cut potatoes[8]. However, temperature is the condition that most significantly affects fresh-cut products, as biochemical reactions increase by 2–3 for every 10 times increase in temperature[9]. Of course, this is also determined by the variety of potatoes[10]. Therefore, the concept of SC storage was introduced.

Supercooling (SC) is an extension of the cold storage method. Vegetables or fruits are stored between freezing temperature (FT), and nucleation temperature (NT), at which they do not freeze and cause tissue damage[11]. SC maintains the active state of tissue cells for a longer period, inhibits enzyme activity, and slows nutrient depletion compared to cold storage, while SC saves more energy compared to freezing. Due to species, tissues, and maturity differences, SC stability and degree are highly variable. So it is necessary to explore the SC point of different varieties of vegetables[12]. Potatoes are rich in nutrients and are a typical vegetable prone to browning[13]. Fresh-cut potatoes have a yellowish-white surface, and slight browning can be observed. SC storage has become an active research field since first reported by Dr. Akira Yamagen from Japan in the 1970s[14]. James et al. discovered that peeled garlic cloves could be preserved for longer durations at subfreezing SC temperatures (−2.7 °C) without freezing[15]. Similarly, Liu et al. reported that apricots could be stored at −1.7 ± 0.2 °C without experiencing cold injuries after 4 d of storage at near-freezing temperatures[16].

The study examined the use of SC for storing fresh-cut potatoes. Fresh-cut potatoes were stored using the SC method for 10 d. During this period, the effectiveness of SC in inhibiting browning was evaluated by measuring the BI of the potatoes. Hardness, bacterial counts, malondialdehyde (MDA), lipoxygenase (LOX), total phenolic content (TPC), total flavonoid content (TFC), peroxidase (PPO), polyphenol oxidase (POD), catalase (CAT), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), superoxide anion (·O2−), 2,2-diphenyl-1-matrylhydrazine (DPPH), and ferrous reducing antioxidant power (FRAP). In short, a supercooling storage temperature of −2 °C significantly reduced the BI, and the microbial growth rate of potato flakes, and enabled potato flakes to maintain a high oxidation resistance.

-

The potatoes (Solanum tuberosum L. cv. 'Wu Chuan') utilized in this study were obtained from Chi Feng, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China (42°15′23.50″ N, 118°52′58.14″ E). Smooth-surfaced potatoes free of mechanical damage were chosen to be pre-cooled for 24 h at 4 °C. They were then cleaned by rinsing in water and sanitized by submerging in a 5% hydrogen peroxide solution for 30 s. Potato tubers were washed with distilled water, peeled, and sliced into 4 mm-thick pieces. Following a sterile distilled water rinse to remove any remaining starch and a layer of filter paper to wipe dry, the potato slices were placed in PE zipper bags, sizes 140 mm by 200 mm, with a 0.3 mm thickness, and placed in an environment containing 21% O2, and 0.03% CO2.

The physicochemical properties and microbial indicators of the samples were assessed at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 d of storage time. The experiment was carried out in three biological replications. Each replication consisted of 120 slices of potatoes, and samples were extracted by randomly taking 15 slices in each replication for technical analysis. For the preparation of the samples to be tested, three samples were randomly taken from the disrupted 15 samples to be prepared to determine the indicators.

Measurement of freezing point and SC point

-

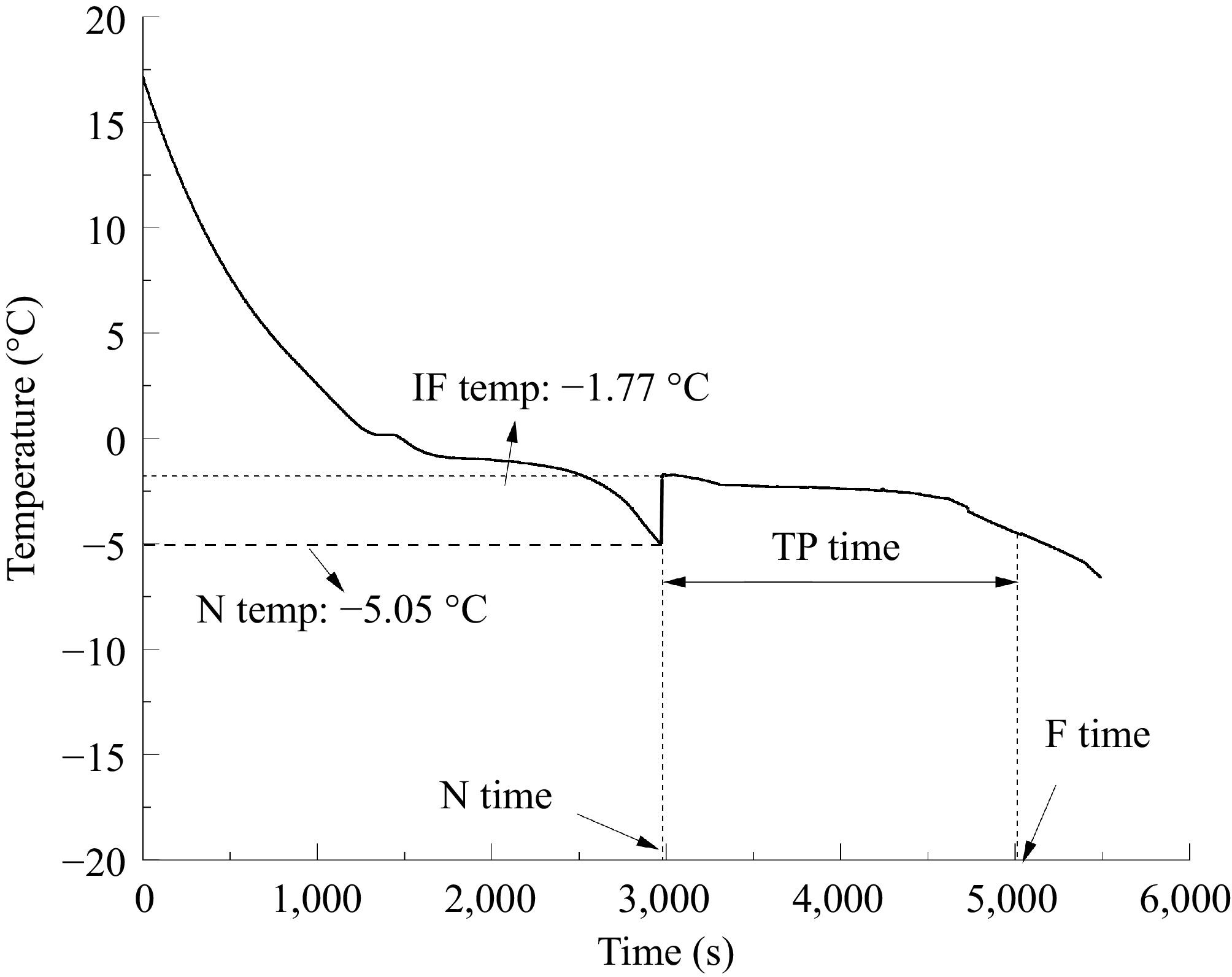

Gauze was used to squeeze the potatoes after they had been ground in a mortar. The ground samples were placed in a small beaker and stirred with a glass rod in an ice water bath. A thermometer was placed inside the beaker, and when the liquid's temperature decreased to 2 °C until the sample solidified, the temperature change was noted. The temperature changes were plotted over time, and the initial freezing point was determined by identifying the point where the temperature curve transitioned to a smooth change (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Freezing curves of fresh-cut potatoes were obtained experimentally. IF Temp: Initial Freezing Temperature; N Temp: Nucleation Temperature; TP time: Transition Phase Time; F time: Freezing Time; N time: Nucleation Time.

The determination of SC points in potatoes was carried out by Koide et al.[17]. Potato samples (2 cm × 2 cm × 2 cm) were prepared, and a T-type thermocouple was placed at the geometric center of each sample. The samples were then stored in a refrigerator (BC-142FQD, TCL Technology Group Ltd.). Temperature data were recorded with a data logger (FLUKE 2638A, FLUKE Electronic Instruments, Inc., USA) at 3 s intervals until the samples reached −20 °C.

Color measurements

-

The color of the potato slices was assessed using a precise colorimeter (HP-200, Shanghai Hampton Optoelectronic Technology Co., Ltd., China). Three potato slices were chosen at random, and each slice had three points checked. Color measurements were represented using L*, a*, and b* values. The following equations were employed to calculate the browning index (BI), and chromatic aberration (ΔE)[18]:

$ BI=\dfrac{100 (\mathrm{x}-0.31)}{0.172}\times 100 $ (1) $ x=\dfrac{{a}^{*}+1.75{L}^{*}}{5.64{L}^{*}+{a}^{*}-3.012{b}^{*}} $ (2) $ \Delta E=\sqrt{{\Delta L}^{*2}+{\Delta a}^{*2}+{\Delta b}^{*2}} $ (3) Hardness determination

-

Hardness was measured using a texturization analyzer (TA-XT plus, Stable Micro Systems, Surrey, UK). Potato slices were cut into rounds with a diameter of 10 mm and a thickness of 4 mm. The test speed is 15 mm·s−1 and the maximum strain is 75%. The sensor shows the compression force vs time as a peak plot, with the peak being the hardness of the sample expressed in N[19].

Bacterial counts

-

The method for determining the total number of colonies adhered to the procedure outlined by Li et al.[20]. 5 g of sample was taken and added to 45 ml of sterile saline, homogenized for 2 min at 8,000 r·min−1 at room temperature to make a homogeneous 1:10 (g : v) solution, and the 10-fold diluted sample solution was then subjected to gradient dilution. For the dilution coating, 1 mL of the diluted sample solution was pipetted, and repeated three times. Following a 48 h inverted incubation period at 36 ± 1 °C, the counts were evaluated visually and reported as colony-forming units per gram, CFU·g−1.

TPC and TFC assay

-

The TPC was determined using the method outlined by Thummajitsakul et al.[21], with results expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalent per kilogram of potato sample (mg GAE kg−1) at 765 nm.

The TFC was assessed using the method described by Tang et al.[22]. The methanol supernatant of the sample was mixed with NaNO2 and incubated with AlCl3 for 5 min. Afterward, NaOH was added for 6 min, and absorbance was measured at 510 nm. TFC results were expressed as milligrams of quercetin equivalents per kilogram of potato sample (mg QCE kg−1).

MDA content and LOX activity

-

MDA content was assessed following the methodologies outlined in prior research[21], with absorbance measured at 350, 532, and 600 nm. The results were reported in μmol·kg−1.

LOX activity was determined following previous studies[23], with absorbance measured at 234 nm and expressed as U·kg−1.

PPO, POD, and CAT enzyme activities assay

-

PPO, POD, and CAT activities were assessed using the method of Meng and Yang et al.[24,25]. PPO activity was assessed by measuring absorbance at 420 nm, POD at 470 nm, and CAT at 240 nm. The results were presented as U·kg−1 relative to fresh weight.

H2O2 content and ·O2− scavenging activity

-

H2O2 production was measured using a hydrogen peroxide assay kit, with results expressed in mmol·kg−1. The superoxide anion (·O2−) was assessed using a superoxide anion assay kit, also expressed in mmol·kg−1.

Antioxidant capacity

-

DPPH was measured according to the method described by Qiao et al.[26]. Following a 4 h reaction, at room temperature in the dark, with phenolic extract and DPPH solution (350 μM in methanol), absorbance was measured at 517 nm. The outcomes were presented as micromoles of trolox equivalents per kilogram of potato sample, μmol TE kg−1.

The FRAP experiment was performed according to Chen at al. with minor adjustments[27]. Following the combination of the samples and L-ascorbic acid solution with the FRAP reagent, the mixture was left to stand at room temperature in the dark for 2 h. The results were reported as micromoles of ascorbic acid equivalents per kilogram of potato sample, μmol AAE kg−1. Absorbance measurements were measured at 593 nm.

Statistical analysis

-

Figure plotting was performed using Origin 2018 (Origin Lab Corporation, Massachusetts, USA). A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted with SPSS 19 (IBM, USA). Data were expressed as mean ± SD, with statistical significance set at p ≤ 0.05. ANOVA was used for statistical analysis, using the assumptions of homogeneity and normalcy of variance. The mean values of potato data from different treatments were different, and ANOVA was considered to test the premise assumption of ANOVA. The normality test results indicated that p > 0.05 suggests the data follow a normal distribution. Additionally, p > 0.05 for the homogeneity of variance test indicates that the variance of potato indices across different treatments is homogeneous.

-

The fresh-cut potatoes exhibited an initial freezing point of −2.2 °C, while the SC had an average of −1.7 ± 0.4 °C (Table 1). Earlier research suggests that fresh-cut potatoes can be preserved at low temperatures near −2 °C[28]. Consequently, the storage temperature for SC in this research was established at −2.0 ± 0.1 °C.

Table 1. Initial freezing point and SC point of fresh-cut potatoes.

Initial freezing point (°C) SC point (°C) Mean −1.7 −3.9 SD 0.4 0.9 SE 0.1 0.2 Min −2.8 −5.4 Max −1.5 −2.2 Initial freezing point: the temperature at which water in potatoes begins to freeze; SC point: between the freezing temperature (FT) and nucleation temperature (NT) without forming ice crystals. Changes in appearance, color, and hardness

-

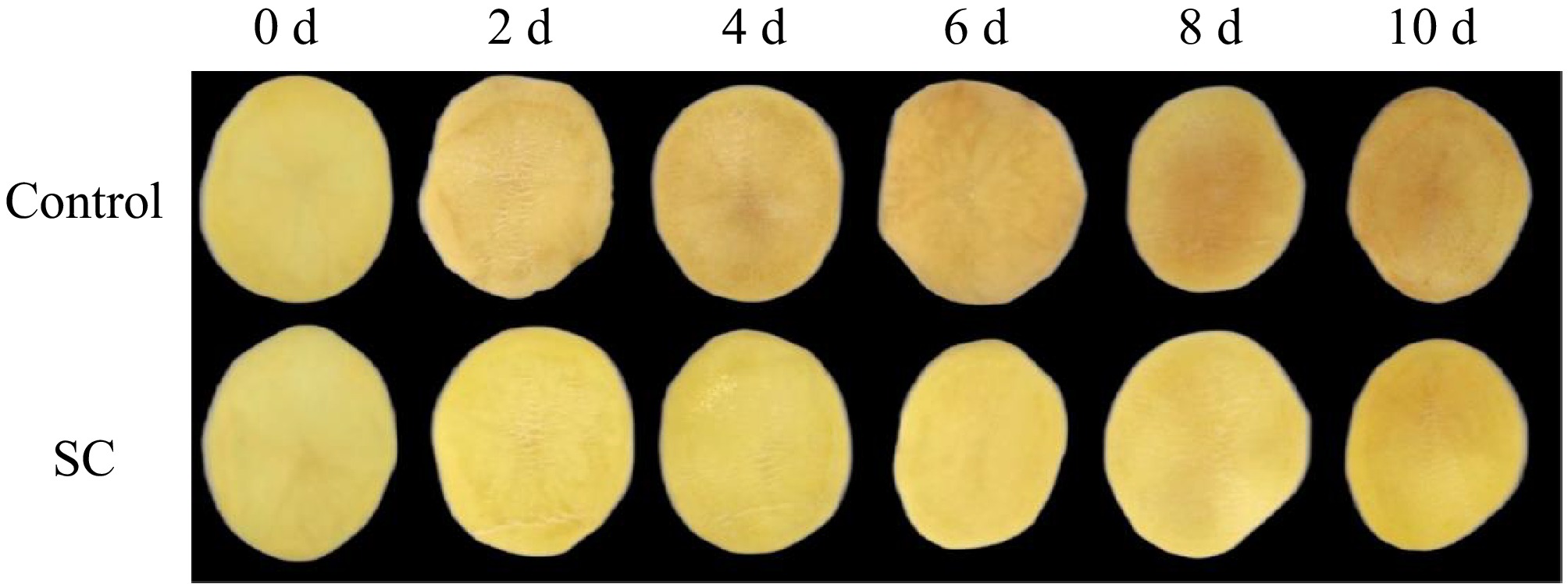

The primary cause of fresh-cut potatoes' declining commercial value is surface browning[29]. Figure 2 illustrates the changes in the appearance of fresh-cut potatoes after 10 d. In control, significant surface browning was observed starting on the 2nd d of storage and gradually browning until the 8th d, when the browning became severe and the commodity value was lost. Conversely, during the storage period, the surface browning of potato slices in the SC group was less pronounced compared to the control group. Notably, almost no surface browning appeared by the 6th d of storage in the SC group. Additionally, the browning level of potato slices in the SC stayed within acceptable limits, even after 10 d.

Figure 2.

Changes in the visual appearance of fresh-cut potatoes during SC storage and the control for 10 d.

The color parameters (L*, BI, and ΔE) of fresh-cut potatoes were analyzed, as depicted in Fig. 3. During the entire storage period, the L* value of the SC samples consistently exceeded that of the control, while the BI value remained lower. The change in ΔE was initially slow but then accelerated. This indicates that the browning rate of fresh-cut potato slices in the SC was slower compared to the control, explaining the visual changes presented in Fig. 2. Gao et al. considered the L* value as an indicator of the brightness of browning in fresh-cut potatoes, that a lower L* value typically corresponds to a darker surface color[30]. Likewise, the BI value is widely acknowledged as a key indicator of the browning level in fresh-cut potatoes.

Figure 3.

Effect of SC storage on color change and hardness of fresh-cut potato slices. (a) L* value, (b) BI value, (c) ΔE, (d) hardness. The results are represented as means ± standard deviations. Different letters represent significant differences among different treatments for each sampling time at p ≤ 0.05.

While the hardness of the control showed noticeable changes by the 2nd d compared to 0 d, the hardness of fresh-cut potatoes in the SC treatment did not exhibit a significant decline in the 10 d storage period. Furthermore, the hardness of the SC-treated samples decreased by only 10.05% from 0 to 10 d of storage, while the control group experienced a more significant decrease of 30.29%. In conclusion, fresh-cut potatoes' surface browning and softening rate were effectively slowed down by SC storage.

Considering that enzymatic browning is the primary factor causing color changes in fresh-cut potatoes, monitoring browning during storage is essential for preserving commercial quality. Earlier studies have focused on maintaining the overall quality of fresh-cut potatoes by preventing enzymatic browning[31]. Raigond et al. treated potatoes with chitosan, and results showed that coating with 0.25% concentration maintained a good appearance after 170 d of storage[32]. Hardness refers to the resistance of fresh-cut products to stress, serving as an indicator of their freshness and brittleness, as well as an indirect measure of nutrient loss[33]. Cutting can also cause vegetables to become softer, primarily as a result of pectin components in the cell wall being hydrolyzed enzymatically and the activity of pectin breakdown enzymes[34]. Wang et al. researched the trend of changes in potato hardness and found that cutting damage can induce the accumulation of Subelin polyphenols and lignin, which can lead to potato softening[35]. The SC state can inhibit the accumulation rate of phenols and lignin by reducing the overall activity in the potato cells, thereby maintaining the hardness of potatoes for extended storage periods.

Total number of microbial colonies

-

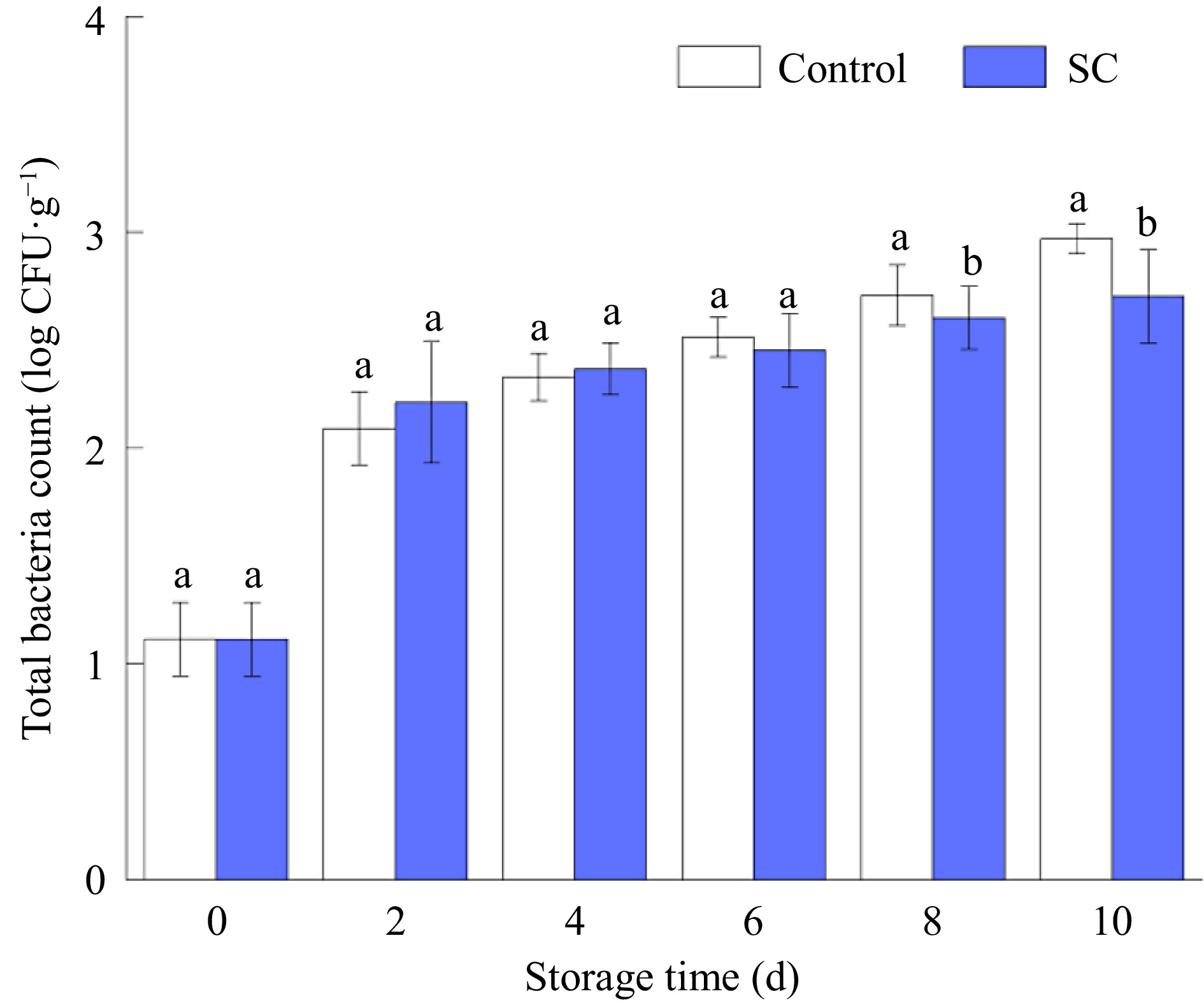

Fresh-cut potato slices are prone to bacterial infections during processing. Excessive microbial growth causes potatoes to spoil and become inedible[36]. Figure 4 shows the total number of microbial colonies in fresh-cut potatoes after 10 d of storage in both the control and SC storage conditions. Although there were more microbial colonies overall throughout the storage period, the control had a faster rate of bacterial reproduction than the SC, and the difference peaked on the 8th and 10th d (p ≤ 0.05). On the other hand, before the 8th d of storage, there was no discernible difference in the total number of microbial colonies between the SC and control. Data revealed that the colonies of the two storage conditions were far below the maximum level of hygienic criteria for the entirety of the pure vegetable product-producing territory (4.70 log CFU·g−1)[37]. This suggests that SC storage slowed the reproduction rate of spoilage microorganisms in potatoes compared with the control.

Figure 4.

The total microbial counts of fresh-cut potatoes under SC and the control during storage of 10 d. Vertical bars show the standard errors. Different letters denote significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) between different storage conditions of the same storage time.

TPC and TFC

-

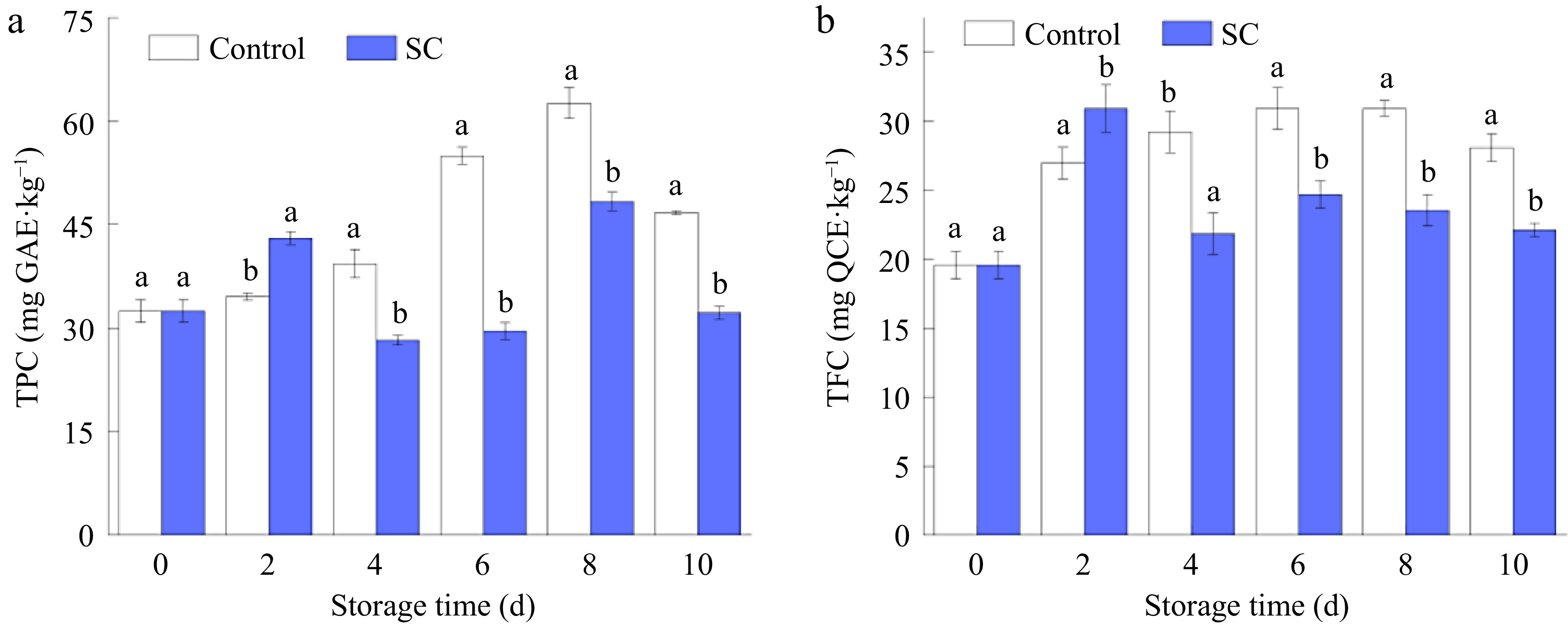

According to the earlier study, flavonoids and phenolics are significant markers of high antioxidant capacity[38]. Chlorogenic acid, the main phenolic compound in potatoes, accounts for 90% of the TPC in potato tubers[39]. Quercetin is the main flavonoid in potatoes, and some other authors have found that potatoes also contain significant amounts of catechins[40].

TPC and TFC of fresh-cut samples were elevated every 2 d during storage, and results suggested both contents in the SC storage were higher than those in the control during the first 2 d. TPC increased 32.6% from 0 d to 2nd d in the SC storage group. The increase in TFC was more apparent in SC storage, which increased by 59.2% compared with 0 d. However, beginning on the 4th d of storage, the phenolic and flavonoid concentrations in the SC group were lower than those in the control group. After 8 d of storage, the TPC accumulation reached its highest level in the control group at 62.62 mg GAE kg−1, while the content in the SC group was 48.33 mg GAE kg−1. At that time, the TPC in the SC was 1.30 times lower than in the control, with a greater overall range compared to the early storage period. The TFC initially increased before starting to decline. Following a 10 d period of storage, the control group TFC was 1.27 times greater than the SC group.

Phenols are the critical substrates for enzymatic browning and can react with enzymes to form brown condensation products under the action of oxygen[41]. Mechanical damage from the peeling and slicing of fresh-cut products disrupts tissue cell membranes, enabling enzymes to directly interact with phenolic compounds, which accelerates the browning process[42]. The phenolic content in fresh-cut broccoli, carrots, and dragon fruit was 5.2, 2.1, and 1.9 times higher, respectively, than in their whole counterparts. Generally, fresh-cut fruits and vegetables contain higher levels of phenolic compounds compared to whole fruits[43]. Hu et al. found that the cause of this difference may be the production of lignin by plant tissues as a toxic stress substance[44]. According to Shraim et al., flavonoids are a subgroup of phenolic compounds[45]. As phenolic substances, flavonoids have a direct impact on both the rate of browning and the antioxidant capacity of plants. The impact of near-freezing temperatures on the storage of fresh apricots yielded results comparable to those reported by Fan et al.[46]. Maximum levels of TP and TF in the fruit were delayed by processing the sample at temperatures close to freezing. As a result, the phenolic and flavonoid contents in the SC were lower than those of the control. On the 8th d of storage, the contents of TPC and TFC increased to the highest levels in the control, as shown in Fig. 5, which corresponds to the obvious surface browning presented in Fig. 2.

Figure 5.

The (a) TPC, and (b) TFC of fresh-cut potatoes under SC and the control during storage of 10 d. Vertical bars show the standard errors. Different letters denote significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) between different storage conditions of the same storage time.

Membrane lipid peroxidation

-

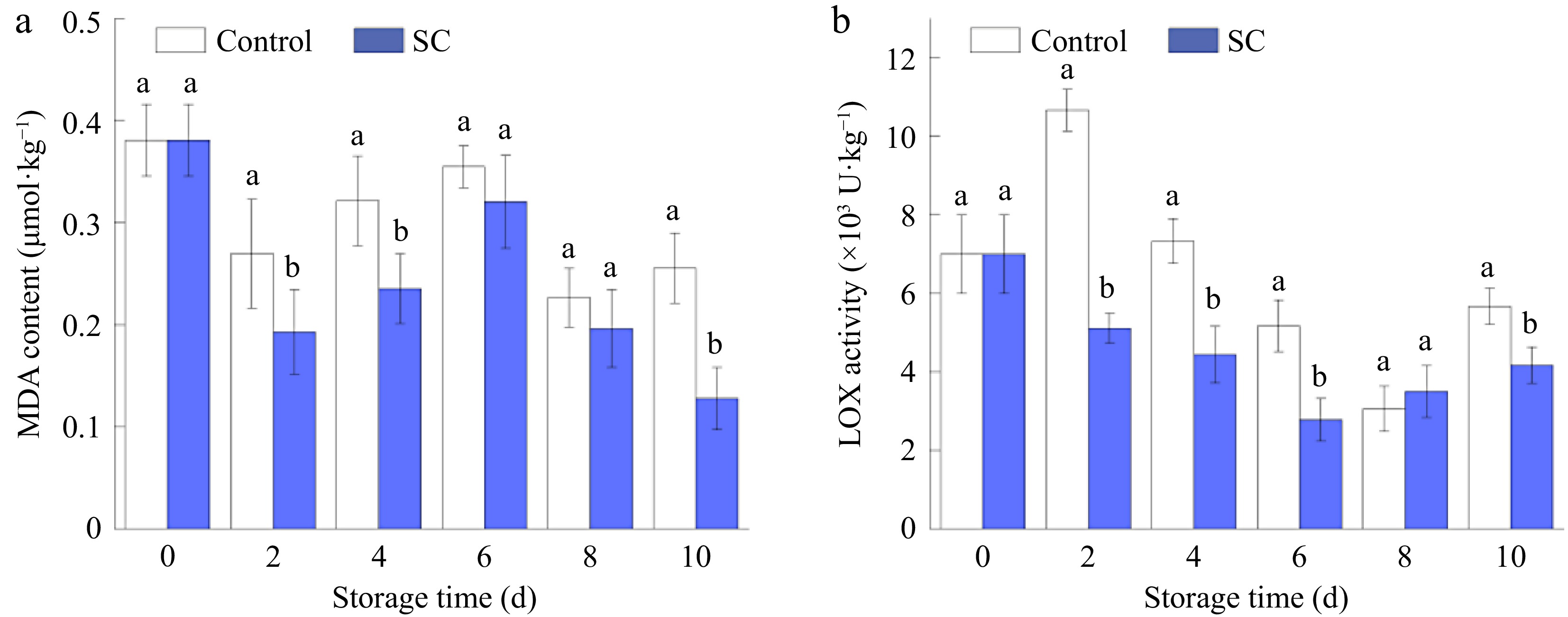

The integrity of fruit membranes and the extent of oxidative damage can be evaluated using MDA levels. The extent of membrane lipid peroxidation, the degree of membrane damage, and the capacity of fresh-cut potatoes to maintain their original condition are closely associated with MDA accumulation levels[47]. Fresh-cut potatoes were stored for 10 d, and Fig. 6a shows the variations in MDA content during that time. In the present study, it was found that the MDA content of fresh-cut potatoes was higher at 0 d, likely due to mechanical damage. This damage induced a stress response in the cell membranes, leading to an initial higher accumulation of MDA. Over time, this accumulated MDA was depleted, resulting in a reduction in its levels. The MDA content in both the SC storage group and the control group followed a pattern of first dropping, then increasing, and then decreasing. MDA levels were consistently and noticeably lower in the SC storage than in the control. After 10 d, the MDA content in the control was 1.99 times higher than that in the SC. The reduced accumulation of MDA in the SC treatment group may be due to the slowed consumption rate of vitamin C and some phenolic substances during the low-temperature storage process, which inhibits the production of MDA. According to reports, mangoes subjected to low-temperature induction exhibited lower MDA content compared to the control group, and this treatment significantly inhibited MDA accumulation[48].

Figure 6.

Changes in (a) MDA content, and (b) LOX activity of fresh-cut potatoes under SC storage and the control during storage of 10 d. Vertical bars show the standard errors. Different letters denote significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) between different storage conditions of the same storage time.

The oxidoreductase class, which includes LOX, is crucial for the ripening and aging of fruits and vegetables[49]. Linolenic acid and linoleic acid, which are abundant in plant membrane lipids, are the main reaction substrates for LOX, which directly act on unsaturated fatty acids to produce membrane lipid peroxidation[50]. As illustrated in Fig. 6b, LOX activity initially decreased and then increased during storage in both the SC storage and control groups. LOX activity in the SC storage group was notably lower than in the control group. On the 6th d of storage, the LOX activity in the SC treatment group reached its lowest point at 2.77 U·kg−1. The lowest LOX activity in the control group was recorded on the 8th d, at 3.05 U·kg−1. Consequently, SC storage significantly reduced the overall LOX activity in fresh-cut potatoes.

The SC treatment inhibited LOX activity, thus preventing the oxidation of additional unsaturated fatty acids. This oxidation reduction, in turn, minimized the extent of damage to the cell membrane. The cell membrane retention was intact so that more MDA would not be accumulated, and thus the rate of potato browning was slowed down. The correlation between severe browning and the accumulation of MDA content and high LOX activity has been shown in previous studies[51]. The present study similarly confirms this view.

Antioxidant-related enzyme activity

-

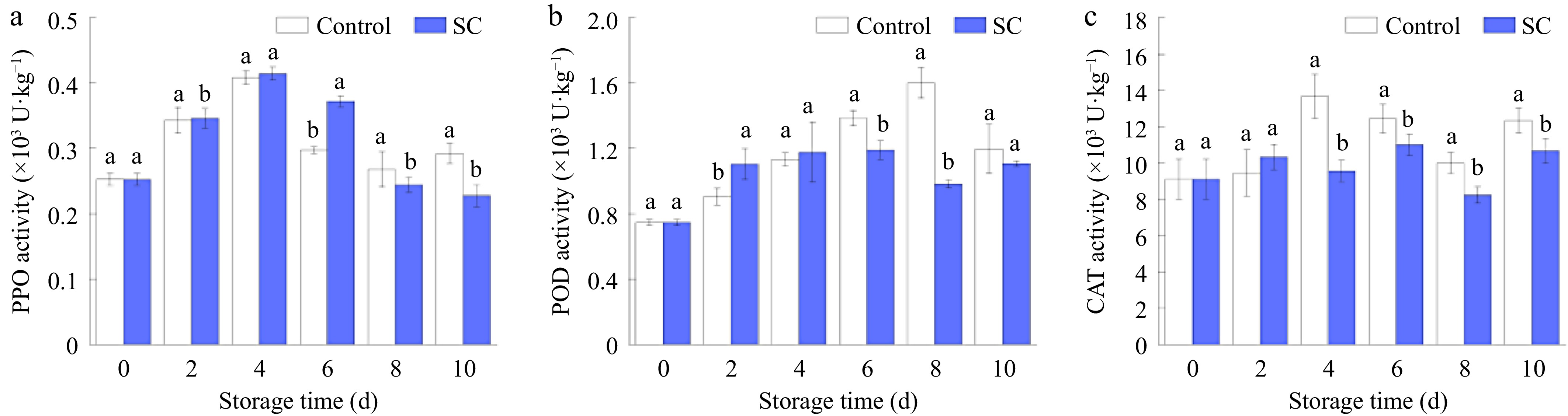

Figure 7 displays the variations in PPO, POD, and CAT activities throughout the storage period of fresh-cut potatoes. As shown in Fig. 7a, PPO activities in both groups exhibited a similar pattern, initially increasing and then gradually declining. On the 4th d, PPO activity reached a maximum in both the control and SC groups; the SC group exhibited slightly higher activity compared to the control group. By the 10th d, the PPO activity in the SC group was 0.228 × 103 U·kg−1, which was 21.9% lower than that of the control (p ≤ 0.05). Enzymatic browning is mostly caused by PPO, an enzyme found in most fruits and vegetables. The cutting process disrupts the membrane system of the potato, breaking the regional distribution pattern. As a result, PPO is activated and oxidizes phenolics in the tissue to quinones, which then produce a black-brown substance through non-enzymatic polymerization[52].

Figure 7.

Changes in (a) PPO activity, (b) POD activity, and (c) CAT activity of fresh-cut potatoes under SC storage and the control during storage of 10 d. Vertical bars show the standard errors. Different letters denote significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) between different storage conditions of the same storage time.

POD activity displayed a similar trend to PPO, with an initial rise followed by a subsequent decline. By the 8th d, POD enzyme activity declined in the SC group, whereas it kept rising in the control group. By the 10th d of storage, POD activity in the SC group was 7.6% lower than that in the control group (Fig. 7b). All things considered, the POD activities of freshly chopped potatoes kept at −2 °C showed little variation and were consistently lower than those of the control group starting on day 6. POD is the key enzyme involved in the oxidation of phenolic compounds, leading to browning as a result. POD breaks down H2O2 during cellular metabolism and uses the released O2 to reduce phenolics and produce quinone. Fruits and vegetables browning is due to the production of a brown material following a sequence of dehydration and polymerization events[53].

The extent of CAT activity changes was overall stable, with the SC group showing lower activity than the control group (Fig. 7c). CAT activity in the control group surpassed that of the SC group after the 2nd d of storage, peaking on the 4th d, while the SC group reached its peak on the 6th d (p ≤ 0.05). CAT also plays a vital role in scavenging free radicals and improving antioxidant capacity. It can decompose H2O2 in plant tissues into H2O and O2 so that H2O2 cannot react with iron chelates under the action of O2 to produce harmful -OH, therefore cells can be protected from H2O2 damage[54].

It can be seen that the occurrence of browning during potato storage is closely related to changes in the activities of antioxidant related enzymes activity. By specific analysis, polyphenol oxidase promotes the conversion of phenolic compounds and molecular oxygen into quinones, which polymerise proteins and other cellular components, leading to the formation of melanin, a dark, amorphous pigment responsible for browning in plants[55]. Thus, a negative correlation exists between PPO enzyme activity and phenolic content in potato fruits. The action of both POD and CAT needs to be carried out by affecting H2O2, and in the later stages of storage, the decrease in CAT enzyme activity leads to an accumulation of H2O2 content[53]. The action of POD on H2O2 results in the release of O2, and phenolics and flavonoids utilize the produced O2 to accelerate the browning of the fruit.

Sugar metabolism and protein synthesis processes in fresh-cut potatoes are also affected by low temperatures. Low-temperature storage is beneficial for maintaining the soluble sugar content in fruits and vegetables, as evidenced by the research conducted by Xie et al.[56]. Low-temperature-induced soluble sugar accumulation is strongly associated with modifications in the levels of gene expression and the activities of enzymes involved in sugar metabolism. The impact of low temperatures on protein synthesis in fruits and vegetables primarily influences the expression and stability of proteins. Under SC conditions, some cold stress-related proteins are induced to be expressed to enhance the cold tolerance of fruits and vegetables. For example, Li et al. showed that when cold damage occurs by low-temperature stress, there is a large up-regulation and down-regulation of the membrane lipid peroxidation of the plant, and the balance of the metabolism of reactive oxygen species in the cell is disrupted, and the generated free radicals attack the cell membrane and produce MDA through metabolism[57].

ROS content and antioxidant activity

-

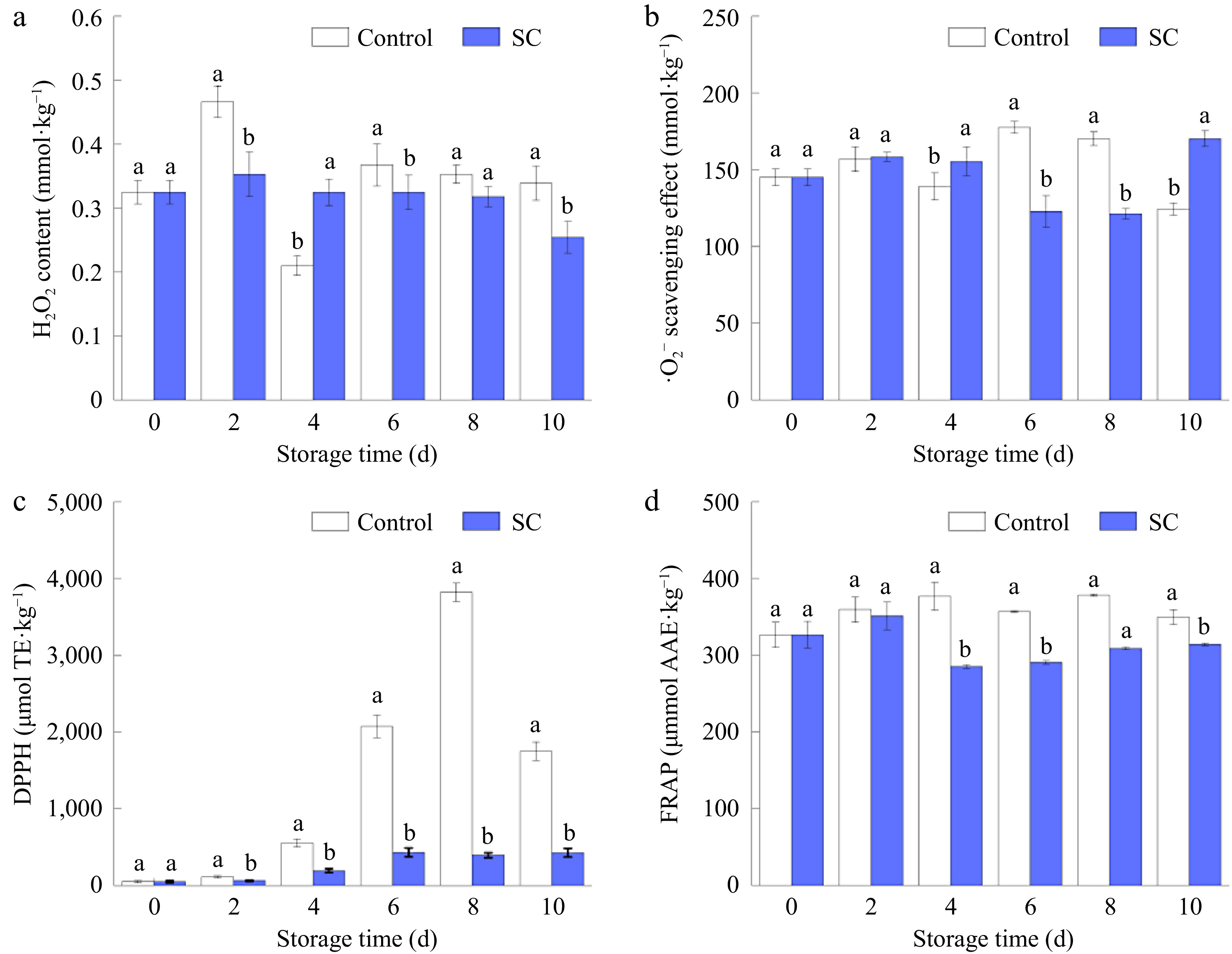

The H2O2, ·O2−, DPPH, and FRAP (Fig. 8a–d) were measured to evaluate the ROS content and antioxidant activities. H2O2 levels in the samples were monitored over the storage period, and it was discovered that the SC treatment group consistently displayed significantly lower levels than the control group (p ≤ 0.05). The H2O2 concentration in the SC group was only 74.9% of that in the control group following 10 d of storage. During the post-harvest storage of fruits and vegetables, ROS primarily exist as H2O2 and ·O2−. This is because ROS is usually the most natural component that stresses plants and causes quality changes[58].

Figure 8.

Changes in (a) H2O2 content, (b) ·O2− scavenging effect, (c) DPPH scavenging effect, and (d) FRAP of fresh-cut potatoes under SC storage and the control during storage of 10 d. Vertical bars show the standard errors. Different letters denote significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) between different storage conditions of the same storage time.

An established index is used to quantify the capacity of plant tissues to scavenge DPPH radicals[59]. In natural conditions, stronger antioxidant capacity is indicated by higher DPPH free radical scavenging capability, which would reduce the degree of browning of fresh-cut potatoes[60]. As illustrated in Fig. 8c, by the 10th d of storage, the DPPH free radical content in the SC group was just 428.89 μmol TE kg−1, marking a 75.5% decrease compared to the control group. The SC treatment effectively inhibited the production of DPPH free radicals in potato tissues, thereby reducing free radical-induced damage. As shown in Fig. 8d, the overall trend of FRAP indicated that the control group had higher levels than the SC group. After 10 d of storage, the FRAP in the SC group was 314.06 μmol·kg−1, which was 10.17% lower than that of the control.

Cutting damages the integrity of potato cell membranes, resulting in the accumulation of ROS, accelerated lipid peroxidation, and increased MDA levels[61]. Simultaneously, ·O2− accumulates, and specific enzymes catalyze its conversion to H2O2. The increasing H2O2 content then traverses the cell membrane to other regions of the tissue, eventually intensifying the browning of potatoes. During the transfer process, H2O2 activates defense enzymes such as POD and CAT in tissue cells, and H2O2 is finally decomposed to H2O and O2 under the action of CAT. SC storage delayed the accumulation of ROS in potatoes, thereby delaying the overall reaction process. Additionally, the low temperature reduced the degree of cell membrane disruption, resulting in lower average ROS content compared to the control group. This is consistent with studies showing trends in ·O2− free radicals and H2O2.

The antioxidant capacity of potatoes is closely related to oxidizing enzyme activity, nutrients, and phenolic free radical scavenging capacity. Low temperature inhibits the activity of various enzymes in potatoes and also induces the conversion of starch to sugar, which are all related to the level of antioxidant capacity. At the same time, the determination of DPPH and FRAP is also affected by temperature and time, in general, the free radicals should be determined so that the reaction solution should be stabilized for more than 3 h to get more accurate results[62].

-

In this research, it was observed that fresh-cut potatoes stored at −2 °C exhibited notably less browning and quality degradation, prolonging their shelf life to 6–8 d. SC storage, with its lower temperatures, reduced the accumulation of TP and TF in fresh-cut potatoes throughout the storage period. This, in turn, led to a decrease in the activation of browning-related enzymes such as POD and PPO. Simultaneously, low temperatures inhibited H2O2 and ·O2−, reducing their inhibitory activity. Additionally, these compounds were rapidly broken down by enzymes like CAT, preventing excessive damage to the cell membranes of fresh-cut potatoes. As a result, MDA content and LOX activity remained low, and the antioxidant capacity (as indicated by DPPH and FRAP) was preserved to the greatest extent. The external manifestation was the decrease of fresh-cut BI value and hardness, which maintained a good appearance condition with good commercial value.

Although SC storage is better than normal refrigeration, it requires more energy to maintain the storage environment during transportation and storage, and the fluctuation of temperature has a greater impact on fresh-cut potatoes, so it is necessary to design and study the supporting equipment. Meanwhile, due to the limitation of sample size, only one potato variety was studied in this experiment and the environmental humidity was not strictly controlled. Different varieties of potatoes have different temperature tolerances, so future research should widely consider the application of multiple varieties while strictly controlling the ambient humidity at 85%–90%. Overall, the present study offers a method for preserving fresh-cut potatoes; however, further improvements are needed for practical applications in the future.

This work was supported by the Tianjin University of Science and Technology Excellent Doctoral Dissertation Innovation Fund Project (YB2023008), the Key Research & Development Program of Shandong Province (2021CXGC010809), and the Key Science and Technology Planning Program of Tianjin (22ZYJDSS00090).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Miao Z, Li W; methodology: Miao Z, Wang H; data curation: Miao Z, Yang M; investigation: Miao Z; formal analysis: Miao Z; writing original draft: Miao Z, Liang F; Data analysis: Liang F, Du J, Jiang Y; visualization: Liang F, Wang H; validation: Li X; project administration: Li X, Jiang Y; supervision, funding acquisition: Li X; writing, review and editing: Li W. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Authors contributed equally: Ze Miao, Fuhao Liang

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Agricultural University, Zhejiang University and Shenyang Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Miao Z, Liang F, Wang H, Yang M, Du J, et al. 2025. Supercooling storage inhibits the browning and quality degradation of fresh-cut potatoes. Food Innovation and Advances 4(4): 516−524 doi: 10.48130/fia-0025-0048

Supercooling storage inhibits the browning and quality degradation of fresh-cut potatoes

- Received: 23 July 2024

- Revised: 30 December 2024

- Accepted: 07 January 2025

- Published online: 15 December 2025

Abstract: This research investigated how supercooling (SC) can inhibit browning and prevent quality degradation in fresh-cut potatoes by analyzing surface color, texture, phenolic metabolism, membrane stability, antioxidant activity, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) equilibrium. Consequently, during SC storage at −2 °C, the browning index (BI) of 197.24 in the SC group was 5.65 times lower compared to the control group, and the hardness loss rate was 20.24% lower than that of the control group. At the same time, the microbial colony counts were reduced. Supercooling reduced the extent of membrane lipid peroxidation in potatoes, leading to significantly lower levels of malondialdehyde (MDA), and lipoxygenase (LOX) activity compared to the control group. Moreover, the activities of browning-related enzymes, peroxidase (PPO), and polyphenol oxidase (POD), were reduced by 21.9% and 7.6%, respectively, compared to the control group. The inhibition of total phenolics (TP), and total flavonoids (TF) decreased the substrates and enzymes associated with browning, collectively mitigating the browning of fresh-cut potatoes. Furthermore, the antioxidant capacity of fresh-cut potatoes was better preserved during SC storage, with lower hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and superoxide anion (·O2−) levels than the control group, suppressing reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation. Overall, SC significantly inhibited browning, and delayed quality decline in fresh-cut potatoes.

-

Key words:

- Preservation technique /

- Fresh-cut /

- Supercooling /

- Browning index /

- Antioxidant ability /

- Microbial population.