-

Vegetables are classified into various genera and species, which play an important role in a nutritious diet. They are rich in vitamins, antioxidants, minerals, fiber, amino acids, and other beneficial substances that provide a healthy diet[1]. They are broadly categorised into roots and tubers, other vegetables, and green leafy vegetables, each having a significant role in nutrition and health[2]. Their regular consumption helps reduce the risk of chronic diseases, strengthens immune defences, and improves overall health. Additionally, vegetable juices, beverages, blends, smoothies, and purees offer numerous health benefits, promoting a healthier lifestyle, which in turn leads to a rapid increase in their consumption, thereby expanding the beverage industry. This signifies their importance in ensuring dietary requirements and meeting nutritional needs. However, despite their numerous benefits, vegetables face significant challenges in post-harvest management, storage, and processing[3].

Vegetables undergo metabolic and respiratory processes even after harvest. This can lead to water loss, microbial infection, and quality degradation during storage and transportation[4]. The industries face challenges in the spoilage of vegetable products, which are usually caused by microbes and enzymes. Salmonella species, Listeria monocytogenes, and Escherichia coli are the primary pathogenic bacteria that can cause foodborne illnesses in fruits and vegetables[5]. Hence, vegetables have a very low preservation time and undergo significant losses due to deterioration. Additionally, conventional methods pose several challenges that impact both the safety and quality of vegetables and juices. Thermal treatments often cause the degradation of biologically active compounds, vitamins, and the nutritional quality of the food. Also, intensive conventional treatment conditions cause the loss of desirable flavors as well as sensory attributes, thereby affecting consumer acceptance[6].

To increase the reliability of vegetables, emerging technologies are needed. Consumers are increasingly seeking food that is high in nutrients and free from microorganisms, as their understanding of food safety has grown. Food that has undergone non-thermal processing is only subjected to a very normal temperature for a short period of < 1 min, and hence, they do not undergo any changes relative to nutrition, texture, or mouthfeel. Novel technologies have been employed to preserve vegetables, including gamma irradiation, ultraviolet light, pulsed electric field, high-pressure processing, and ultrasound[7]. Among these technologies, pulsed electric field (PEF) and ultrasound (US) stand out for their scalability, cost-effectiveness, and minimal impact on nutritional and sensory qualities. Since non-thermal processing methods often cause less damage to food attributes than thermal processing, extensive research has been conducted on these novel approaches[8−10]. US and PEF technologies support the objectives of sustainable food processing and have a beneficial impact on the environment[11].

PEF technology is primarily used for preserving foods with high electric permeability, such as liquids or semi-liquid foods. PEF enhances the conductivity of the cell membrane by causing a persistent poration to form using an electric field. Food and nutraceutical industries are still in the early stages of applying pulsed electric fields[12]. On the other hand, ultrasound is applied in food processing to enhance preservation, improve mass transfer, support thermal treatments, modify texture, and assist in food analysis[13]. In liquids, ultrasound causes 'cavitation'; in gases, it causes pressure change, and it causes movement of liquids in solids[14].

Despite the advancements, studies into the synergistic application of US and PEF technologies in vegetable processing remain limited. While the literature has explored the individual effects of US and PEF on food quality, there is a lack of comprehensive studies investigating their synergistic effect on the physicochemical, rheological, and microbial characteristics of vegetable-processed products. The mechanism of ultrasound and its effect on quality standards and the efficiency of drying in different fruits and vegetables was discussed by Zhou et al.[15] while Ali et al.[16] described the effect of pulsed electric fields on texture attributes in different fruit and vegetable juices. In recent years, only a few review papers have highlighted the application of PEF and the US in carrots, potatoes, and spinach, despite being nutrient-dense and widely consumed staple foods that act as great examples for assessing the impact of non-thermal technologies due to their distinct compositions, such as high carotenoid content, starch, and chlorophyll. However, this review focuses on these vegetables, highlighting the potential of US and PEF in maintaining physicochemical, rheological, and microbial properties. This review also highlights the role of the US and PEF in retaining the nutritional and bioactive properties of these vegetables and vegetable-processed products.

-

Ultrasound has emerged as a green food processing technology due to its numerous advantages, including energy efficiency, low operating temperatures, and the potential to preserve the nutritional and sensory properties of food products[17]. These benefits, combined with its potential for sustainability, positioned ultrasound processing as a compelling alternative to thermal processing methods[18,19]. The ultrasonic process utilises high-frequency (20–100 kHz) and high-intensity (1–1,000 W/cm2) acoustic waves, which can penetrate various materials, making them effective for multiple applications in food processing[20,21].

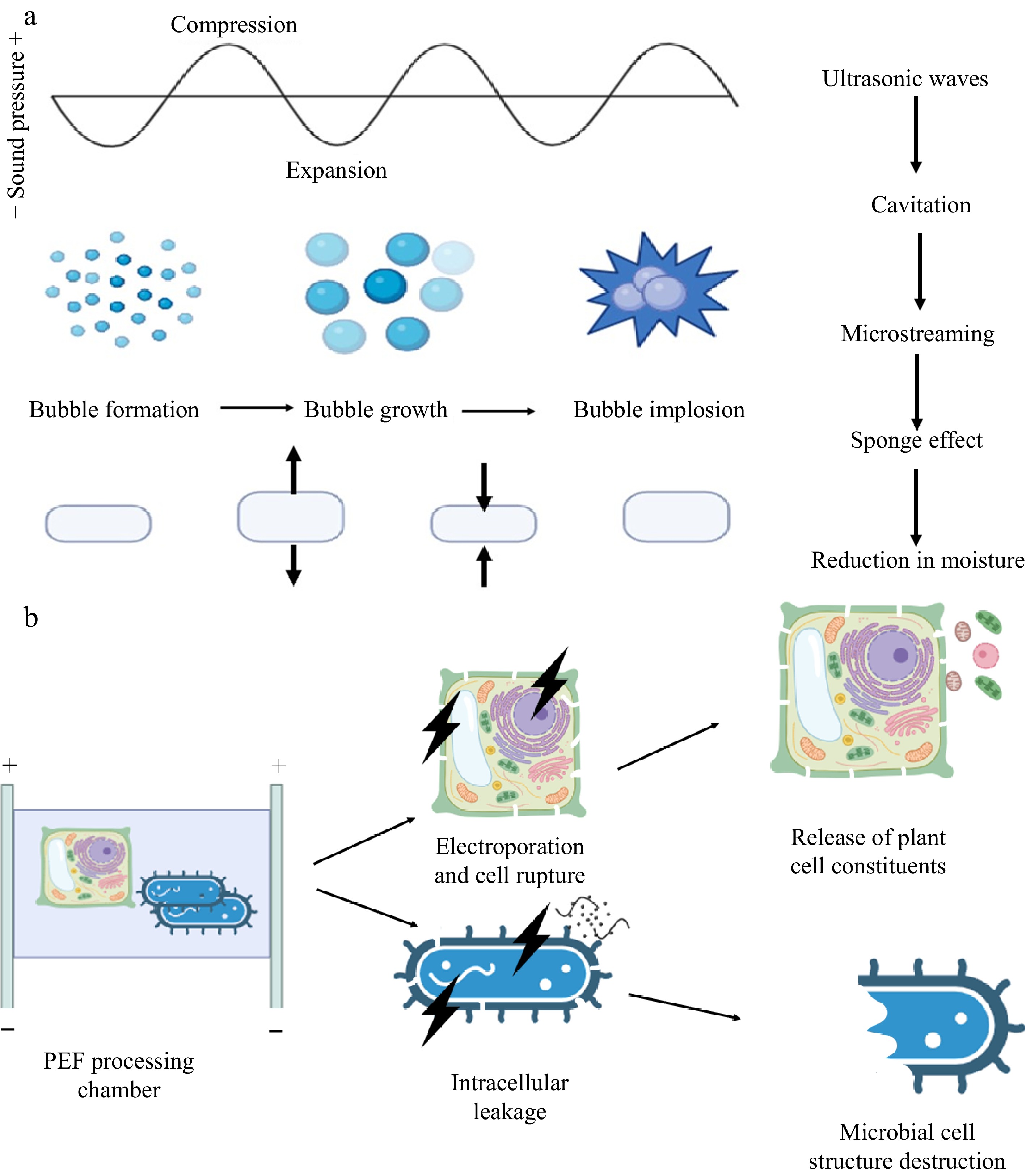

Ultrasonic processing equipment typically comes in two main types: ultrasonic bath-type and probe-type devices, which utilise piezoelectric transducers to convert electrical energy into pressure waves[22,23]. High-intensity ultrasound technology is employed for various industrial applications, including drying, extraction, pasteurisation, and emulsification[24]. The primary mechanisms of action in ultrasound processing include the sponge effect, cavitation, microstreaming, and microjetting. The sponge effect involves repeated compression and release cycles, which alter water surface tension, create surface wrinkles, and reduce initial moisture content, thereby improving drying and extraction efficiency[25,26]. According to studies, the type of drying material determines the efficiency of the sponge effect, which has a positive impact on this phenomenon[27].

Cavitation occurs when ultrasound waves generate microbubbles in liquids or moist solids, leading to localized pressure and temperature changes[28]. These microbubbles oscillate rapidly, leading to disruptions in plant tissue that enhance bulk and heat flow, which is known as 'microstreaming'[29]. The collapse of a single bubble releases only a small amount of energy, creating points of extremely high pressure and temperature, as shown in Fig. 1a[30]. The asymmetric collapse generates a fluid jet directed towards the solid surface, causing the tissue to be disrupted. This effect is called 'micro jetting' [31].

Figure 1.

(a) Cavitation and sponge effect induced by ultrasound. (b) Cellular mechanisms under pulsed electric field treatment.

Pulsed electric field and its construction and mechanism

-

PEF is emerging as a potential technology due to its wide-ranging applications in both biotechnology and the food industry, alongside its reputation as a sustainable method. PEF has shown potential across various areas, including microbial inactivation, enhancement of fruit quality[32], improvement of potato chip products[33], and optimisation of drying and extraction processes[34]. Additionally, PEF shows promising potential in winemaking, biogas production, and protein modification[35].

PEF works by applying short, high-intensity pulses (10–80 kV/cm) for microseconds to nanoseconds to the food material placed between electrodes. The total PEF processing time is calculated by increasing the duration of each pulse by the number of pulses delivered[36]. The efficiency of PEF is determined by electrode geometry and the voltage generator[37]. PEF systems consist of a high-voltage pulse generator, control and monitoring equipment, and a treatment chamber equipped with a cuvette[38]. The effectiveness of PEF depends on voltage, electrode spacing, and pulse width, with capacitors generating pulses and triggers regulating circuit decay[39]. The high-voltage pulse generator can be a direct current or an alternating current[40].

The primary cellular mechanism involved in PEF is electroporation, which is characterized by transmembrane potential and pore formation[41]. The transmembrane potential induced by PEF leads to the formation of hydrophilic pores, which then expand, causing leakage of intracellular contents and microbial inactivation as shown in Fig. 1b[42]. PEF enhances the extraction of intracellular components from plant cells by permeabilizing cell membranes, leading to the release of compounds[43]. The cellular mechanism in PEF plays a key role in microbial inactivation and the extraction of intracellular components. Several process parameters, including pulse frequency, waveform, flow rate, and product parameters, such as chemical composition, pH, and conductivity, influence the outcome of PEF treatment[44].

Industrial applications and limitations of the US and PEF

-

The industrial application of PEF and US in food processing often presents innovative opportunities for enhancing product quality and safety. PEF serves as a pre-treatment for processes like freezing and drying, thereby potentially enhancing the quality[45]. On the other hand, US is used in various processes such as freezing, crystallisation, drying, and emulsification[46]. The US is used to enhance the texture and flavour of food[47]. Combining both US and PEF has been developed in olive oil production, resulting in a yield increase from 16.3% to 18.1% and enhancing the nutritional profile of the oil[48].

Despite all the advantages, both the US and PEF have significant limitations and challenges for small-scale and industrial applications. PEF processing can lead to electrochemical reactions between the electrodes and food, causing corrosion, fouling, and chemical changes in the food, which in turn affect the safety and quality of the food[49]. Additionally, the high cost of PEF systems, particularly the pulsers, makes it challenging to scale up to an industrial level[50]. While in the US, the difficulty arises from the dense and complex food matrices, such as proteins, which limit the effectiveness in certain applications[51]. The need for advanced designs is necessary to enhance the cavitation efficiency and consistency[52]. Both the US and PEF face challenges in optimising the process conditions to overcome these challenges[53]. Hence, the current research should focus on mitigating these challenges and expanding their applications.

-

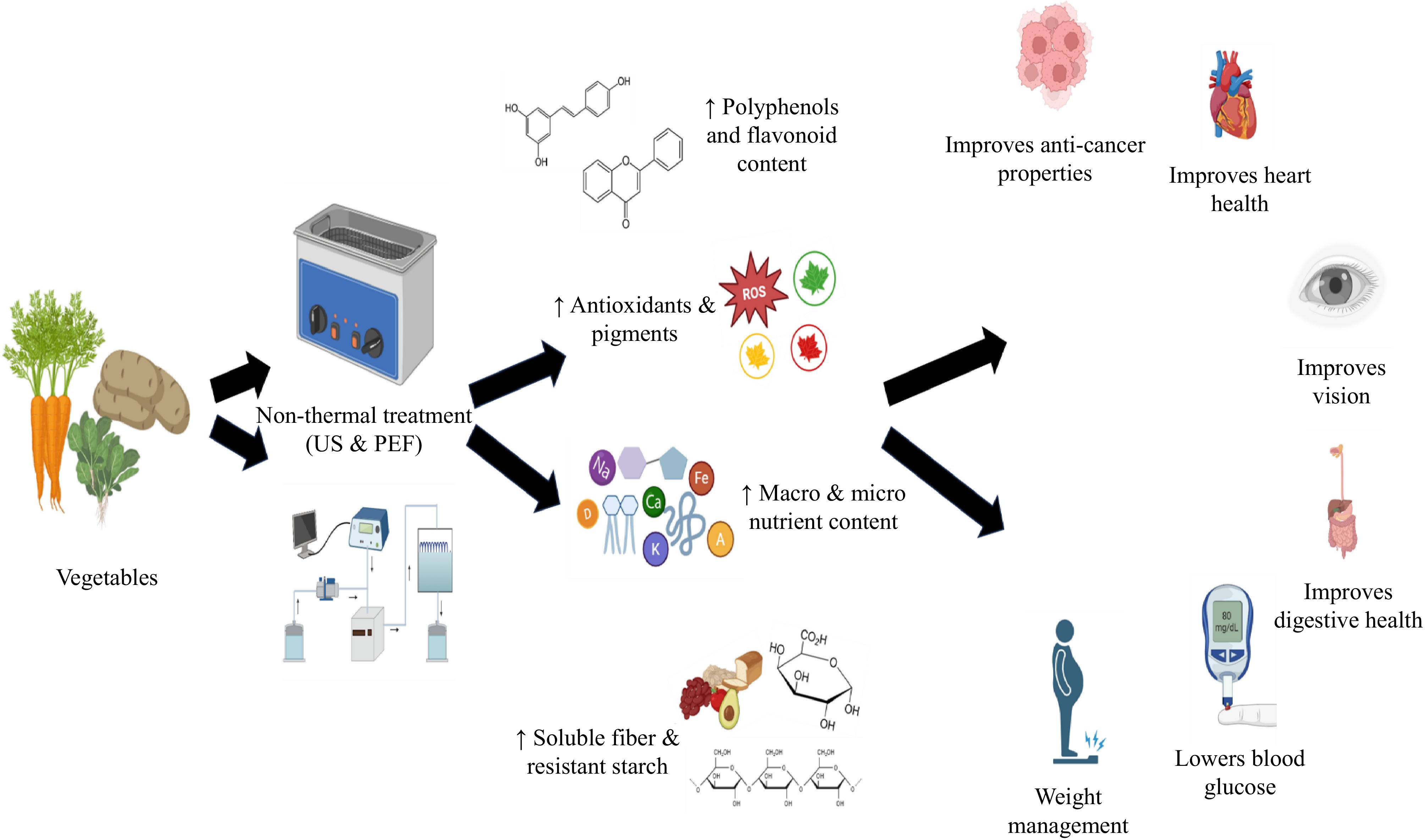

Vegetables come in various types, each playing a distinct role. Vegetables are crucial for maintaining overall health due to their abundant nutrients, including vitamins, minerals, dietary fiber, and phytochemicals[54]. Regular vegetable consumption has been linked to several health benefits, including improved gastrointestinal health, enhanced vision, and a lower risk of chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and certain types of cancer[55]. The World Health Organization suggests an everyday consumption of 400–600 g of vegetables and fruits to help prevent micronutrient deficiencies and chronic health conditions[56]. Ultimately, consuming a wide variety of vegetables is essential for maximising health benefits and reducing the risk of nutrition-related diseases[57]. Ultrasound and pulsed electric fields have the potential to enhance the therapeutic health benefits of carrots, potatoes, and spinach (Fig. 2). The application of US and PEF improves the extraction of compounds, thereby increasing the nutritional value of these vegetables, mainly focusing on carrots, potatoes, and spinach due to their significant nutritional value and processing potential.

-

The application of non-thermal processing techniques, particularly ultrasound and pulsed electric fields, has shown a significant effect on the quality and nutritional value of various vegetables. PEF is effective in enhancing the extraction of bioactive compounds, which are beneficial for carrots and potatoes[58,59]. However, high-power ultrasound inactivates the enzymes that degrade the quality of spinach, thereby improving its nutrient value and quality[58]. In carrot juice, PEF treatment enhances the bioaccessibility of carotenoids and phenolic compounds[59]. The combined application of the US and PEF resulted in increased concentrations of flavonoids, phenolics, and carotenoids, while reducing the microbial load[60].

Physicochemical and bioactive compounds of carrots

-

Due to their well-known high content of phytonutrients and their bioactive properties, carrots are a valuable component of a healthy diet. Carrots are a rich source of carbohydrates and minerals. The amount of protein, carbohydrates, fat, and fiber present in 100 g of carrot roots is around 0.93, 9.58, 0.24, and 0.24 g, respectively (USDA 2015)[61]. Essential minerals present in carrots include K, Mg, and Ca[62]. Carrots are the major source of carotenoids, containing primarily 75% β-carotene, 23% α-carotene, and 1.9% lutein. The high content of β-carotene accounts for its remarkable antioxidant, anti-cancer, and immune-stimulating properties[63]. The phenolic compounds possess antioxidant properties, which contribute to the reduction of inflammation and oxidative stress[64].

Potential of the US and PEF in improving the nutritional profile of carrots

-

Ultrasound treatment has been found to maintain and enhance the β-carotene content in carrots, which is crucial for its antioxidant properties[65]. US and PEF-assisted drying processes increase the polyphenol and flavonoid content, which are linked to anti-cancer and anti-diabetic effects[66]. The US and PEF significantly enhance moisture diffusivity during the drying process, ensuring the preservation of nutrients and quality in carrots[67]. Carrot juices treated in the US exhibited the highest antioxidant activity, indicating improved vision[68]. Additionally, the antioxidant properties enhanced by US and PEF contribute to reduced oxidative stress, a factor that contributes to the development of cardiovascular diseases and obesity[69].

Physicochemical and bioactive compounds of potatoes

-

The composition of potatoes includes essential amino acids, vitamins, minerals, and bioactive compounds that promote health. It is a rich source of carbohydrates (16.5–20 g) and provides 96.33–123.17 kcal of energy from a 100 g intake[70]. The fiber content in the peel of a potato is around 1.8 g, while cooked potatoes have 2.1 g. An amount of 1–1.5 g of protein is served with 100 g of potatoes[71]. Potatoes are associated with antioxidant properties due to their content of phenolic acids, including ferulic, caffeic, and chlorogenic acids, as well as anthocyanins. Their bioactive profile is further enhanced by the presence of glycoalkaloids, which may have positive health effects[72]. Potatoes are rich in minerals and vitamins, including copper, zinc, iron, and magnesium, as well as vitamins C, E, and B. Additionally, phytonutrients such as anthocyanins, carotenoids, phenolics, and flavonoids are abundant in these tubers. These plant nutrients are antioxidants that support human health and well-being[73].

Potential of the US and PEF in improving the nutritional profile of potatoes

-

The US can enhance the bioavailability of nutrients that support cardiovascular health and regulate blood sugar levels[74]. Ultrasound-assisted extraction significantly increases the yield of health-promoting compounds such as anthocyanins, which possess antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties in potatoes[75]. High-intensity ultrasonication enhances the recovery of functional proteins in potato trimmings, potentially facilitating obesity management by increasing satiety. Polyphenols in potatoes, such as chlorogenic and ferulic acids, exhibit anti-carcinogenic and anti-diabetic properties, potentially reducing the risk of cancer and regulating blood sugar levels[76]. The preservation of these compounds through PEF enhances their bioactivity, making potatoes a valuable dietary component for the prevention of cancer and diabetes[77]. The effects of PEF and US on the overall nutritional quality and potential adverse effects on certain enzymes, such as polyphenol oxidase, need further research[78].

Physicochemical and bioactive compounds of spinach

-

Since spinach is rich in phytochemicals and bioactive compounds, it is considered a functional food that supports human health. The nutritional profile of spinach is of six components: carbohydrates, proteins, fats, fiber, minerals, and vitamins. The reported contents of spinach include 50.10% to 50.59% carbohydrates and 14.13% protein[79]. Numerous studies have noted that spinach contains high concentrations of polyphenols and phytochemicals, including β-carotene, flavonoids, aromatic chemicals, and phenolic acids[80]. Reportedly, a high amount of calcium (13.4 mg/100 g) and iron (40.4 mg/100 g) is present in spinach[81]. Antioxidants, which include flavonoids and phenolic compounds, help combat oxidative stress and also lower the risk of neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's. Minerals and vitamins like iron, calcium, magnesium, and vitamins K, A, and C are all present in spinach, which are necessary for multiple bodily functions[82].

Potential of the US and PEF in improving the nutritional profile of Spinach

-

US-PEF treatment has been shown to enhance the concentrations of minerals and free amino acids in spinach juice, which are crucial for various health benefits[77,78]. These phytochemicals in spinach modulate gene expression related to cancer prevention[83]. PEF treatment significantly enhances the antioxidative activity of spinach pigment, thereby helping to combat oxidative stress[84]. These antioxidants can lower blood sugar levels, contributing to weight and diabetes management[85]. The disruption of cells caused by ultrasound potentially releases essential vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants from spinach. This increases the bioavailability of nutrients, such as carotenoids and flavonoids, which in turn aid in maintaining gut health and improving the absorption rate[86].

-

The studies examined how ultrasound affected various plants, including potatoes, broccoli, spinach, and carrots. The main conclusions are that the drying rates and time for carrot slices were raised, the microbial inactivation of spinach was enhanced, and the PPO activity inhibition of potatoes was adjusted[87,88]. Furthermore, it was discovered that ultrasound improved freezing rates, encouraged dehydration, and preserved the vegetable's quality. The findings of various studies on the application of ultrasonic processing of vegetables are shown in Table 1. Together, these results demonstrate how ultrasonic technology can be utilised to enhance the quality, processing, and preservation of various vegetables.

Table 1. Effect of ultrasound on whole vegetables.

Vegetables US conditions Physical changes Chemical changes Reasons Ref. Carrot slices US type: ultrasound bath;

Power: 1.5 kW;

Frequency: 20, 30, and 40 kHz;

Amplitude: N.A.;

Time: 3, 5, and 7 min;

Temperature: 25 °C;

Quantity/speed: 3 mm thick slicesDecreased color parameters with increased treatment time.

Improved more porous structure.Decreased protein content.

Enhanced ash content.

Increased total phenolic and flavonoid content.

Increased the value of β-carotene.Enhanced the nutritional value of carrots, but intensive treatment led to protein denaturation and physical changes. [88,89] Carrot slices US type: ultrasound bath;

Power: 150 W;

Frequency: 40 kHz;

Amplitude: N.A.;

Time: 0–20 min;

Temperature: 50 °C;

Quantity/speed: 5 mm thick slicesDecreased drying time.

Changes in color index.

Increase in water diffusivity rate.

Decrease in rehydration with an Increase in treatment time.− US enhanced the bioactive compound release, while prolonged treatment time led to protein denaturation and structural changes. [21,67,68] Carrot slices US type: US vibration disk and infrared drying;

Power: 0–80 W;

Frequency: 20 kHz;

Amplitude: N.A.;

Time: time interval 5 min.

Temperature: N.A.;

Quantity/speed: 5 mm thick slicesIncrease in drying rates.

High water activity.

Positive effect on rehydration ratio.

More porous microstructure.

Increased heat transfer.

Reduction in the ratio of shrinkage.A decrease in vitamin C retention. US assisted drying enhanced porosity and rehydration but a decrease in vitamin C was reported due to thermal sensitivity. [46,51] Carrot cubes US type: ultrasound bath;

Power: 240 W;

Frequency: 35 kHz;

Amplitude: N.A.;

Time: N.A.;

Temperature: 25 °C;

Quantity/speed: 400 gmMinimal changes in quality parameters.

Reduced pH.

No change in texture.Increase in ascorbic acid content.

Increase in cellulose with an increase in treatment time.

Decreased hemicellulose and pectin content.

Loss of carotene content.

Enhanced total phenolic content.

Rise in antioxidant activity.The US enhanced both physical and chemical properties with minimal changes, suggesting that moderate treatment conditions can improve food quality. [29,31,66] Carrot US type: ultrasound bath;

Power: 30 WL−1;

Frequency: 40 kHz;

Amplitude: N.A.;

Time: 5 min;

Temperature: 20 °C;

Quantity/speed: N.A.Decrease in surface cell number.

Positive effect on microbial reduction.Increase in surfactant Tween 20 concentration. The cavitation effect caused by US led to microbial reduction and enhanced surfactant interaction. [69,82] Potato powder US type: ultrasound probe;

Power: 0–5 w/cm3;

Frequency: N.A.;

Amplitude: N.A.;

Time: 15 min;

Temperature: 25 °C;

Quantity/speed: N.A.Improved the gel texture properties.

Enhanced water and oil absorption capacity.Increased content of α-helix.

Enhanced the β-sheet values.

Increased amylose content.US treatment caused a significant enhancement in the overall quality of potato powder, suggesting that moderate treatment conditions can improve food quality. [87,88] Potato US type: ultrasound probe;

Power: 1,200 W;

Frequency: 20 kHz;

Amplitude: N.A.;

Time: 15 min;

Temperature: 20 °C;

Quantity/speed: N.A.Micro-structure disruption. Promote polyphenol oxidase activity inhibition. US enhanced polyphenol oxidase activity inhibition leading to reduced enzymatic browning. [75,78] Potato US type: US freezing system;

Power: 270 W;

Frequency: 20, 28, and 40 kHz;

Amplitude: N.A.;

Time: N.A.;

Temperature: –18 °C;

Quantity/speed: N.A.Enhances freezing rate.

Reduced drip loss.

Increase in cavitation yield.

Decreased firmness of the potato.Reduced calcium content.

Enhanced L-ascorbic acid content.

Decrease in total phenolic content.The cavitation effect led to an enhanced freezing rate, while intensive treatment conditions resulted in mineral and phenolic loss. [73,88] Potato US type: ultrasound bath;

Power: 480 W;

Frequency: 40 kHz;

Amplitude: N.A.;

Time: 10 min;

Temperature: 25 °C;

Quantity/speed: 5 mm thick slicesLowered the color parameters.

Decreased texture properties such as firmness and chewiness.

Reduced pH and soluble solids.Reduction in PPO (polyphenol oxidase) and POD (peroxidase) activity.

Enhanced PAL (phenylalanine ammonia-lyase) activity.

Increased total phenolic content.

Enhanced antioxidant properties.Tissue disruption caused by US led to a reduction in physical properties, while the cavitation effect resulted in enhancement of chemical properties. [72,73,78] Potato US type: ultrasonic probe;

Power: 500 W cm–2;

Frequency: 20 kHz;

Amplitude: 50%–100%;

Time: 2–4 min;

Temperature: 18–23 °C;

Quantity/speed: 140 gEnhanced the lightness color value.

No change in the ratio of rehydration.Decreased total phenolic and total monomeric anthocyanin content.

Changed antioxidant values.

Reduction in ascorbic acid content.The short duration with intense power of US treatment led to degradation of chemical compounds, suggesting for optimization of conditions to improve overall quality. [75,88] Potato US type: ultrasound bath;

Power: 60 W;

Frequency: 28 ± 0.5 kHz;

Amplitude: N.A.;

Resonance: 0–20 Ω;

Time: 30 min;

Temperature: 25 °C;

Quantity/speed: Ten piecesPromotes the dehydration process.

Reduce drying time.

Decrease in moisture content.

Enlarged micropores.Increase in total phenolic and total flavonoid content with increasing ultrasound power. Prolonged duration and increased power of the US enhanced the quality of the potato. [66,67,88] Spinach US type: jet ultrasound;

Power: 100 W;

Frequency: 40 kHz;

Amplitude: N.A.;

Time: 15 min;

Temperature: 20 °C;

Quantity/speed: N.A.;

Flow: 0.5–2.0 L/minPromoted stomatal closing.

Enhances freshness.Increased abscisic acid signaling.

Enhanced the activity of Ethylene-sensitive 3 Binding F-box proteins 1 and 2.The US enhanced both physical and chemical properties with minimal changes, suggesting that moderate treatment conditions can improve food quality. [91] Spinach US type: N.A.;

Power: 150 W;

Frequency: 40 kHz;

Amplitude: N.A.;

Time: 10, 25, 30 min;

Temperature: 25 °C;

Quantity/speed: N.A.Increase in the capacity of extracts.

Enhanced antibacterial activity.Increase in antioxidant activity.

Increased total phenolic content.Moderate US treatment enhanced the overall quality of spinach. [92] Spinach US type: ultrasound bath;

Power: 400 WL–1;

Frequency: 40 kHz;

Amplitude: N.A.;

Time: 3 min;

Temperature: 23 °C;

Quantity/speed: N.A.Caused reduction in yeasts and molds.

Reduced total bacterial count.– The short duration of the US treatment and the cavitation effect caused microbial reduction in spinach [58,60,99] Broccoli US type: ultrasonic probe;

Power: 400 W;

Frequency: 24 kHz;

Amplitude: 100 µm;

Time: 5 min;

Temperature: 20 °C;

Quantity/speed: 180 gHigh intensity caused cell disruption of the tissue. Increased the extraction of glucoraphanin, 4-hydroxy glucobrassicin, and glucobrassicin.

No change in total ascorbic acid and isothiocyanate content.Moderate conditions of US preserved chemical compounds, while the intensive power led to cell disruption. [93,94] Broccoli US type: N.A.;

Power: 400 W;

Frequency: 24 kHz;

Amplitude: 100 mm;

Time: 10, 20, 30, 60, 120 min;

Temperature: 25 °C;

Quantity/speed: N.A.Ruptured cell wall polysaccharides.

Change in cell structure.Increased phenolic acid compounds.

Enhanced carotenoid content.

Increased chelate soluble pectin and sodium carbonate soluble pectin.

Enhanced carotenoid and phenolic acid compounds.

Increased ascorbic acid content.Extended treatment time led to the release of bioactive compounds and enhanced bioactive content. [93,98] Broccoli US type: ultrasonic vibrating plate;

Power: N.A.;

Frequency: 20 kHz;

Amplitude: N.A.;

Time: N.A.;

Temperature: 20 °C;

Quantity/speed: 3 gReduction in drying time. Reduced Fe2+.

Decreased the content of glucoraphanin.

Enhanced the sulforaphane content throughout the treatment.The US vibrating plating led to reduced drying time, while oxidative reactions led to a reduction in chemical properties. [93,106] Broccoli US type: ultrasonic probe;

Power: N.A.;

Frequency: 23 kHz;

Amplitude: 135 µm;

Time: 1–20 min;

Temperature: 25, 42.5, and 60 °C;

Quantity/speed: 1 g– Promoted myrosinase activation.

Reduction in sulforaphane content.US treatment led to an initial increase in myrosinase, but prolonged treatment conditions led to a reduction of sulforaphane content. [94,106] Effect of ultrasound on the physicochemical characteristics of whole roots and tubers

-

Ultrasonic bath treatment led to a significant decrease in colour parameters, protein content, and ascorbic acid content. While the total phenolic content and flavonoid content (7.9%) were enhanced after sonication, and β-carotene value increased[89,90]. Carrot cubes treated with an ultrasonic bath at a frequency of 35 kHz exhibited slightly reduced pH and textural parameters, while the ascorbic acid content and total phenolics increased, resulting in enhanced antioxidant activity. Prolonged treatment resulted in an increase in cellulose content to 8.6 ± 0.2, but reduced hemicellulose, pectin, and carotene levels to 0.7 ± 0.3, 0.01 ± 0.36 g/100 g FM, and 102 ± 13 µg/g DM, respectively. Ultrasound-treated carrots showed a decreased cell number and reduced and inactivated Bacillus cereus spores to 2.22 log CFU g−1 [20,68,89]. Therefore, careful control of the intensity and duration of the treatment is required to minimise nutrient loss.

Ultrasound-treated potato powder with a power density of 0–5 W/cm3 led to an enhanced quality in terms of physicochemical properties. Ultrasonication significantly increased oil absorption capacity to 2.12 times and water absorption capacity to 1.36 times. The α-helix content increased by 1.47 times and the β-sheet by 1.26 times that of the untreated sample, thereby improving the gelling texture[87]. A study on two varieties of whole potatoes was treated with ultrasound at a 20 kHz frequency and a power of 1,200 W, resulting in a decrease in PPO activity to 42.9% and 47.4% of that of the untreated ones. However, the intensity of the treatment should be monitored to avoid structural damage that might affect the textural quality.

Potato slices treated with an ultrasonic probe enhanced the lightness colour value. The reductions in bioactive compounds are due to the oxidative degradation by the high energy of ultrasound. The TPC, DPPH, TEAC, and TMA contents ranged at 3.01 ± 0.019 mg GAE/g dw, 3.83 ± 0.035 mg TE/g dw, 3.11 ± 0.040 mg TE/g dw, and 1.91 ± 0.005 mg Cyn-3-glu/g dw at US 100% amplitude for 4 min[88]. Optimisation of ultrasound intensity and duration could help minimise the loss of bioactive compounds. Ultrasound treatment is effective in improving the physicochemical characteristics of vegetables; however, the intensity and treatment time should be optimised to minimise nutrient loss and maintain the overall quality of the vegetables.

Effect of ultrasound on the physicochemical characteristics of whole green leafy vegetables

-

The use of a jet ultrasonic cleaner at a frequency of 40 kHz for a period of 15 min improved the closure of stomatal pores and enhanced freshness in spinach as there was an increase in EBF1 and EBF2 (Ethylene-insensitive 3-Binding F-box Protein 1 and 2) from –1.584, 1.619 to 1.841, 10.632 respectively indicating a response that helps in maintaining cellular integrity and extending shelf life of fresh spinach[91]. A reduction of 2.08 log CFU/g in total bacterial count was observed in spinach treated with ultrasound. Specific bacterial counts of E. coli and L. monocytogenes were decreased by 2.41 log CFU g−1 and 2.49 log CFU g−1, which could be due to the cavitation effect generated by ultrasound[92]. This method is effective for reducing microbial contamination without compromising the nutritional and quality properties of spinach.

The ultrasound treatment was carried out in broccoli at a power of 400 W and a frequency of 24 kHz. The treatment resulted in the rupture of cell wall polysaccharides, thereby releasing nutrients. Carotenoid content and phenolic acid content were also noted to be improved to 20.2 ± 0.2 mg/100 g DW and 841 ± 17 mg/100 g DW. However, an increase in chelate-soluble to 205 ± 18 mg/100 g AIR and sodium carbonate-soluble pectin to 366 ± 24 mg/100 g AIR was observed[92,93]. The broccoli florets treated with an ultrasonic probe have inactivated myrosinase, reducing it to 508 ± 12 U from 2,450 ± 72 U, thereby facilitating enzymatic activity. The reduced sulforaphane content to 64% after treatment indicates that optimal conditions must be maintained to preserve the bioactive compound[94].

Effect of ultrasound on vegetable juices/ thick juice/puree

-

Various researchers have done experiments to explore the effects of temperature, time, power, and frequency of ultrasound on the quality parameters of these juices. For instance, various frequencies and power levels have been studied in the case of carrot juice, leading to changes in physicochemical properties, a reduction in aerobic bacteria, and an improvement in carotenoid content[90]. Similarly, ultrasonicating spinach juice has resulted in a rise in beneficial chemicals, a decrease in bacteria, and modifications to its colour[57,58]. Also, the application of ultrasound to sweet potato juice results in enhanced antioxidant activity and β-carotene bio accessibility[95]. Overall, the results suggest that ultrasonic treatment may improve the quality and nutritional profile of vegetable juices. Table 2 provides a comprehensive overview of how ultrasonic treatment impacts various vegetable juices.

Table 2. Effect of ultrasound on vegetable juices, thick juices, and purees.

Vegetables Ultrasound conditions Effect on microorganisms Effect on rheological properties Findings Ref. Carrot puree US type: ultrasound bath;

Power: 300 W;

Frequency: 21 kHz & 35 kHz;

Amplitude: N.A.;

Intensity: 0.5 W/cm2;

Time: 30 min;

Temperature: 20–50 °C;

Quantity/speed: 200 g− Enhanced viscosity with increase in extract content.

Increased consistency coefficient K.

Increased flow behaviour with increased frequency in 12 °Brix.No significant change in total soluble solids.

No significant change in color parameters.[59,65] Carrot juice US type: ultrasound bath;

Power: N.A.;

Frequency: 40 kHz;

Amplitude: N.A.;

Intensity: 0.5 W/cm2;

Time: 20–60 min;

Temperature: 20 °C;

Quantity/speed: N.A.Reduced total microbial plate count to 3.23 ± 0.11 log CFU/mL.

Decreased yeast and mold counts by 3.03 ± 0.09 log CFU/mL.Increased the viscosity to 2.23 ± 0.08 cP. Increase in color.

Enhancement in total carotenoid content.

Increase in total soluble solids.[68,76,109] Carrot juice US type: ultrasound probe;

Power: 400 W;

Frequency: 24 kHz;

Amplitude: 120 µm;

Time: 0–10 min;

Temperature: 50, 54 and 58 °C;

Quantity/speed: 500 mReduced E. coli to more than 5 log values. − No change in pH, soluble solids, and acidity.

Negligible increase in carotenoid content.

No major change in phenolic content and ascorbic acid content.[90,110] Carrot juice US type: ultrasound probe;

Power: 525 W;

Frequency: 20 kHz;

Amplitude: 70%;

Time: 5 min;

Temperature: 15 °C;

Quantity/speed: 250 ml− − Enhanced all the quality parameters such as pH, total soluble solids, phenols, and flavonoids. [90,109] Carrot juice US type: ultrasound probe;

Power: 950 W;

Frequency: 20 kHz;

Amplitude: N.A.;

Time: 2–10 min;

Temperature: 4 °C;

Quantity/speed: 200 mlInactivation of pectin methylesterase by 72.55%. Decreased viscosity by 1.27% initially and then increased by 2.29 mPa·s 1.78%. Polyphenol oxidase and pectin methylesterase decreased.

Increase in turbidity.

Decreased carotenoids.[65,90] Carrot juice US type: ultrasound cell;

Power: 271 W;

Frequency: 20 kHz;

Amplitude: N.A.;

Time: 10 min;

Temperature: 30 °C;

Quantity/speed: 25 mlInactivation of aerobic microorganisms by 4.28 log10 cycles. Increased viscosity by 2.29 mPa·s. No change in total soluble solids, pH.

Changed color attributes.[110,109] Carrot juice US type: ultrasound waves;

Power: 1,000 W;

Frequency: 20 kHz;

Amplitude: N.A.;

Time: N.A.;

Temperature: 30 °C;

Quantity/speed: 1,000 ml/10–20 ml per s− − No change in pH, total soluble solids, and total phenolic compounds.

Enhanced color parameters.[69,90,109] Sweet potato juice US type: ultrasound probe;

Power: 0.66 W/cm;

Frequency: 20–100 kHz;

Amplitude: N.A.;

Time: 8 min;

Temperature: probe temperature 550 °C;

Quantity/speed: 200 mlReduction of polyphenol oxidase to 98.7% ± 3.2% and peroxidase activity to 97.8 ± 3.0%. − Increases bioaccessibility of β carotene and antioxidant activity. [74,75,88] Sweet potato paste US type: ultrasound probe;

Power: N.A.;

Frequency: 26 kHz;

Amplitude: 20%, 40%, 60%;

Time: 2, 6, 10 min;

Temperature: 25 °C;

Quantity/speed: N.A.Inhibited the enzymatic activity of peroxidases and polyphenol oxidase to 98%. − Highest anthocyanin content.

Enhanced overall color attributes.

Increased total phenolic content.[95] Spinach juice US type: ultrasonic bath;

Power: 180 W;

Frequency: 40 kHz;

Amplitude: N.A.;

Time: 21 min;

Temperature: 30 °C;

Quantity/speed: 100 mlDecrease in POD Abs min−1 to 31.76% and PPO Abs min−1 to 36.00% activity. Caused a minimal increase in cloud value to 0.218 ± 0.01 and cloud stability to 10.45% ± 0.08%. Increase in flavonoids, phenolics, and anthocyanins.

Enhanced carotenoid content.

Improved overall chlorophyll content.

Lowered vitamin C content.

Change in color parameters.[60] Spinach juice US type: ultrasonic homogenizer;

Power: 600 W;

Frequency: 30 kHz;

Amplitude: N.A.;

Time: 30 min;

Temperature: 60 °C;

Quantity/speed:100 mlReduction in E. coli, yeast, and molds up to 4 log CFU/ mL. Decrease in viscosity to 1.123 ± 0.2 Pa.sn.

Decrease in yield stress.Enhanced bioactive compounds. [58,60] Spinach juice US type: ultrasound bath;

Power: 200 W;

Frequency: 40 kHz;

Amplitude: N.A.;

Time: 21 min;

Temperature: 30 °C;

Quantity/speed:100 mlReduced activity of E. coli to 1.5 log CFU/mL. Decrease in viscosity by 13.10 mPa·s. Reduction in particle distribution.

Increase in free amino acids (FAA).

Decrease in Fe, Ca, Mn, and Zn content.

Increase in K.[59,65] Broccoli puree US type: ultrasonic sonotrode;

Power: 500 W;

Frequency: 18 kHz;

Amplitude: N.A.;

Time: 7 min;

Temperature: 60 °C;

Quantity/speed: N.A.Decreased the count of Enterobacteriaceae to 2.26 ± 0.12 log CFU/mL. − Increased total polyphenol content.

No change in pH and tritrable acidity.

Reduced the content of glucoraphanin.[98,99] Effect of ultrasound on microbial, rheological, and physicochemical properties of vegetable juices/ thick juice/puree

-

Ultrasound treatment on carrot juice has significantly reduced total microbial plate count to 3.23 ± 0.11 log CFU/mL and yeast and mould counts by 3.03 ± 0.09 log CFU/mL, possibly due to the disruption of the cell walls caused by the temperatures during the treatment process[69,89,90].

A study on carrot juice treated with ultrasound at 30 °C reduced aerobic microorganisms by 4.28 log10 cycles[90]. In contrast, the same microbes are inhibited by up to 98% in sweet potato paste using ultrasound at 25 °C[96]. However, the reduction of E. coli was achieved using an ultrasonic homogenizer and an ultrasonic bath system. The reduction of E. coli using an ultrasonic homogenizer was up to 4 log CFU/mL, and by bath, it was 1.5 log CFU/mL in spinach juice[92,97]. Broccoli puree treated with a sonotrode at 60 °C showed a reduction in Enterobacteriaceae count by 2.26 ± 0.12 log CFU/mL[98]. Ultrasonic treatment provides an effective approach for inactivating microorganisms in vegetables. However, the treatment conditions must be optimised so as to preserve the nutritional and quality parameters of the juice.

The effect of ultrasound on the rheological properties of vegetable juices has been extensively studied, revealing significant changes in viscosity and flow behaviour. In a study of ultrasound probe treatment resulted in an initial decrease in viscosity of 1.27% in carrot juice, followed by an increase of 1.78% with extended treatment time[15,27,31,89]. The initial decrease in viscosity could be attributed to the breakdown of molecules caused by cavitation; however, the subsequent release of cell wall polysaccharides gradually led to an increase in viscosity. Also, Bi et al.[90] interpreted an increased viscosity of carrot juice treated with ultrasound by 2.29 mPa·s. In spinach, US treatment caused a minimal increase in cloud value to 0.218 ± 0.01 and improved cloud stability to 10.45 ± 0.08%, thereby maintaining a uniform particle distribution[58,59]. The viscosity of spinach juice decreased to 1.123 ± 0.2 Pa·s when treated with US at 30 kHz frequency, and a reduction up to 13.10 Pa·s resulted when treated at 40 kHz[92,97]. While ultrasound is a promising technique in enhancing the rheological properties of vegetable juices, it is essential to consider the potential for over-processing, which could lead to undesirable changes in flavour and nutrient degradation.

A recent study on carrot puree reported no significant change in total soluble solids and colour parameters when treated with 21 and 35 kHz frequencies for 30 min, potentially indicating that moderate ultrasonic treatment doesn't alter the physical properties of foods[65]. Spinach juice treated with ultrasound showed enhanced flavonoid content from 703.18 ± 0.11 CE µg/g to 753.18 ± 0.14 CE µg/g, phenolics increased from 860.87 ± 0.13 GAE µg/g to 945.28 ± 0.19 GAE µg/g, anthocyanins, and carotenoids increased to 37.01 ± 0.07 µg/ml and 2.92 ± 0.04 µg/g as a result of the ultrasonic treatment. In other treatment conditions with 200 W and 40 kHz frequency, the spinach juice showed a reduction in particle distribution and an increase in free amino acids[80,82]. In broccoli puree, ultrasonic treatment resulted in a significant increase in total polyphenol content and a corresponding decrease in glucoraphanin content. The thermal degradation during the treatment caused a decrease in glucoraphanin content[98]. Ultrasound is an effective technique for enhancing the functional and nutritional properties of vegetable juices, thereby increasing their bioavailability.

Effect of pulsed electric field on vegetable-processed products

-

Dried carrots and carrot slices, under PEF conditions varying in electric field strength, pulse width, and treatment time, exhibited reduced drying time, minimal colour change, increased phenolic content, slowed cooking behaviour, and cell disruption. For spinach, PEF treatment increased the drying rate, inhibited surface shrinkage, and preserved L-ascorbic acid. Baby spinach leaves demonstrated improved freezing tolerance when treated with PEF combined with cryoprotectants[83,84,99]. In potatoes, PEF reduced frying conditions, lowered oil consumption, enhanced crust hardness acceptability, increased diffusion rate during frying, and significantly reduced acrylamide content in potato chips[96]. Table 3 presents the various studies on the application of PEF treatment on different vegetables, highlighting the conditions and findings of each study.

Table 3. Effect of pulsed electric field on whole vegetables.

Vegetables PEF conditions Physical changes Chemical changes Reasons Ref. Dried carrot Pulse shape: rectangular shape;

Pulse type: monopolar pulses;

Electric field strength: 0.6 kV/cm;

Pressure: 0.3 bar;

Number of pulses: N.A.;

Treatment time: 100 µs;

Temperature: 25–90 °CReduced drying time.

Caused minimal color changes when compared to untreated samples.Increased the extraction of β-carotene. Moderate PEF conditions enhanced quality while preserving color. [100,111] Carrot slices Pulse shape: N.A.;

Pulse type: monopolar pulses;

Electric field strength: 0.6 kV/cm;

Output voltage: 1.5 kV;

Pulse width: 10–1,000 μs (± 2 μs);

Time interval: 10 minDecrease in drying time.

Lowered color parameters.

Moisture ratio was decreased in PEF-treated samples.

Caused restoration of cell forms.− Electroporation enhanced moisture loss, leading to reduced drying time. [101] Carrot Pulse shape: rectangular shape;

Pulse type: bipolar pulses;

Electric field strength: 0.9 kV/cm;

No of pulses: 1,000;

Pulse time: 20 µsDecrease in color attributes.

Increase in yellow color characters.

No change in shear stress.

Increase in cell disintegration index.

Reduction in drying time.− Moderate treatment condition enhanced physical properties, causing minimal changes. [63,61] Carrot slices Pulse shape: N.A.;

Pulses: 4 μs;

Capacitor: 0.1 μF;

Frequency: 0.1 Hz;

Voltage: +5 to +7 kV DC;

Output voltage: +50 VEnhance cell disruption.

Reduced the color parameters regarding lightness value.Increase in phenolic content after 24 h.

Showed high antioxidant potential.Intensive treatment led to degradation in physical properties while enhancing compound extraction. [101,102] Potato chips Pulse shape: N.A.;

Pulse type: N.A.;

Pulse generator: N.A.;

Total energy input: 0.75–1.5 kJ/kg;

Electric field strength: 1 kV/cm;

Pulse width: 6 µs;

Frequency: 24 kVReduced frying time.

No significant changes in texture properties.

Reduced oil uptake.Reduced fat content.

Reduced acrylamide content.

Decreased reducing sugar contents.Moderate PEF treatment enhanced overall food quality and safety. [105,96] Potato (French fries) Pulse shape: N.A.;

Pulse type: N.A.;

Pulse generator: 30 kW;

Total energy input: 2 & 50 kJ/kg;

Electric field strength: 1.1 kV/cm;

Pulse width: 20 µs;

Frequency: 200 HzReduction in frying conditions.

Reduced oil consumption.Lowered the percentage of slowly digestible starch.

Increased the percentage of resistant starch.Overall quality of fries has enhanced when treated with moderate PEF treatment conditions. [103] Potato chips Electric field strength: 1 kV/cm

Specific energy input: 1 kJ/kg

Pulse energy: 450 J

Capacitors: 0.5 μF

Discharge voltage: 30 kV

Frequency: 2 Hz

pulse width: 40 μsIncreased diffusion rate.

Enhanced frying behavior.Reduced the content of acrylamide. PEF enhanced cell permeability, thereby enhancing the overall quality of chips. [102,103] Potato slices Pulse shape: N.A.;

Pulse type: N.A.;

Electric field strength:1 kV/cm;

Pulse width: 20 µs;

Pulse frequency: 50 Hz and 150 kJ/kgNo change in lightness color parameters. − Moderate treatment conditions maintain the quality of potato slices without changing physical properties. [103] Spinach Pulse shape: N.A.;

Pulse type: N.A.;

Electric field strength: 2.8 kV/cm;

Pulse width: 1 μs;

Frequency: 30 Hz;

Capacitance: 0.218 μF;

Specific energy input: 27.1 kJ/kgThe rate of drying increased.

Change in moisture content.

Surface shrinkage was more inhibited.

Increased the color attributes.Prevented elution of L-ascorbic acid. Moderate PEF enhances drying efficiency and enhances chemical compounds. [99] Baby spinach leaves Pulse shape: rectangular pulses;

Pulse type: bipolar;

Amplitude: 350 V;

Pulses: 500;

Pulse width: 200 μs;

Pulse space: 1,600 μs;

Frequency: 500 HzImproved freezing tolerance. Increase in sucrose and fructose accumulation post-harvest.

A decrease in glucose accumulation.Electroporation and moderate stress enhanced sugars. [84,99,105] Broccoli stalks Pulse shape: N.A.;

Pulse type: N.A.;

Interelectrode distance: 11.0–29.7 cm;

Electric field strength: 8.00 kJ/kg, 2.50 kJ/kg, 0.5–2 kV/cmRuptured the membrane of broccoli stalks. Change in volatile profile, such as dimethyl sulfide and ethyl acetate. An increase in electric field strength gradually led to cell rupture and changed the volatile compound profile. [106] Chinese cabbage Electric field strengths: 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, and 2.5 kV/cm;

Pulse generator: 5 kW;

Pulse width: 20 µs;

Frequency: 50 Hz;

Voltage: 400 V;

Current: 25 A;

Temperature: 25 °CChanged color attributes.

Decrease in texture qualities.Increased pH.

Enhanced acidity and salinity.A change in electric field strength gradually led to pigment release and texture degradation. [112] Effect of pulsed electric field on physicochemical characteristics of whole roots and tubers

-

Dried carrots treated with PEF exhibited minimal colour change and a shortened drying time, from 6 to 1.5 h. There was an increase in the yield of β-carotene from 170 mg/100 gDM to 207 mg/100 gDM[100,101]. Additionally, in another study, carrot slices dried 55% faster than the untreated ones and underwent less colour change as a result of PEF treatment. In terms of relative diameter and relative thickness, there was no difference in comparison to untreated samples[101,102].

Carrots treated with 1,000 pulses had no significant change in shear stress. But reduced drying time by 5% at 60 °C and 28% at 70 °C. PEF caused an increase in yellowness to 24.68 ± 3.25[59]. In carrot slices, severe treatment conditions enhanced the total phenolic content to 39.5 ± 0.1% and 40.1 ± 0.2%[103,104].

Potato chips were subjected to PEF with a frequency of 24 kV, resulting in a 10% reduction in frying time. The fat content of fried chips was reduced to 6.45%. PEF significantly reduced acrylamide and reducing sugar content, making a healthy impact on consumers[105,96]. PEF treatment had no effect on the value of lightness during frying for samples that did not undergo blanching. This implies that the application of PEF does not considerably change the colour changes that potato slices undergo during frying, even though it may have other impacts[104,96].

Effect of pulsed electric field on physicochemical characteristics of whole green leafy vegetables

-

Spinach was treated with PEF, which accelerated the drying process to 1.5 h, prevented surface shrinkage, and inhibited the elution of L-ascorbic acid. The colour parameters of the PEF-treated sample were 41.33 ± 0.53, –8.14 ± 0.09, and 18.99 ± 0.26 for L* (lightness), a* (redness), and b* (yellowness), respectively[99]. In another study, PEF treatment on spinach leaves increased the accumulation of sucrose and fructose and improved freezing tolerance post-harvest[83,84]. In broccoli stalks, PEF treatment caused membrane rupture, resulting in changes to the volatile profiles, including the presence of dimethyl sulfide and ethyl acetate[106].

Effect of PEF in vegetable juices/ thick juice/puree

-

The effects of temperature, voltage, pulse width, and frequency of PEF, as well as their potential impact on various vegetable-processed products, are discussed in Table 4. In spinach juice, PEF has been shown to significantly increase the content of flavonoids, phenolics, and chlorophyll[58,59]. Similarly, in carrot puree, PEF has been shown to enhance the carotenoid and phenolic content[107]. However, these findings highlight the potential of PEF to enhance the microbial activity and improve the rheological and physicochemical properties of vegetable-processed products.

Table 4. Effect of pulsed electric field on vegetable juices, thick juices, and purees.

Vegetables PEF conditions Effect on microorganisms Effect on rheological properties Findings Ref. Carrot juice Electric field strength: 3.5 kV/cm;

Passes: 5 times− − Exhibits highest carotenoid and phenolics.

No change in pH and total soluble solids.[67] Carrot puree Capacitor: 0.1 µF;

Frequency: 0.1 Hz;

Pulses: 3.5 kV cm−1− Viscosity increased minimally to 1.48 ±

0.04 mPa·s.Increased carotenoid and phenolic bioaccessibility.

Improved bioaccessibility of caffeic acid derivatives and ferulic acid derivatives.

Change in microstructure.

No change in pH and total soluble solids.

Minimal change in color attributes.[107] Carrot puree Pulse frequency: 10 Hz;

Pulse type: bipolar pulse;

Voltage: 1–4 kV;

Pulses: 100, 300, 500, 1,000 and 2,000;

Pulse width: 20 µs;

Specific energy input: 1.5–576 J/kg− − High level of polyacetylene content.

Increase in FaDOH, FaDOAc, and FaOH.

Increase in sucrose, β−glucose, α−glucose, and fructose levels.[113] Carrot mash Electric field strength: 0.8 kV/cm;

Voltage: 4 kV;

Pulse energy: 4 J;

Capacity: 0.5 µF;

Pulse width: 10 µs;

Input: 0.5 kJ/kg;

Time: 0.5 ms− Increase in viscosity. Increase in juice yield.

Improved cell disintegration.

Decrease in TSS content and increase in TDS content.

Decreased the pH level.[101,108] Spinach juice Electric field strength: 9 kV/cm;

Frequency: 1 kHz;

Pulse width: 80 µs;

Time: 335 µs;

Temperature: 30 °CDecreased polyphenol oxidase to –44.00% RC (relative change) and peroxidase enzyme activity to –43.52%. − Flavonoids were increased.

Phenolics were increased.

Anthocyanins exhibited an increase.

Significant increase in carotenoid content.

Enhanced concentration of chlorophyll.

No variation in color attributes.[60,62] Spinach juice Electric field strength: 20 kV/cm and 20 kV/cm Reduced aerobic microbial growth to less than 1 log CFU/mL. Lowered flowability. No decrease in lutein content.

Inhibited the degradation of pigments.[58] Spinach juice Frequency: 1 kHz;

Pulse width: 80 µs;

Flow rate: 60 ml/min;

Temperature: 30 °C;

Time: 335 µs;

Electric field strength: 9 kV/cmDecreased polyphenol oxidase by 56% and peroxidase enzyme activity by 78.82%. Enzymatic reduction of Peroxidases and polyphenol oxidase. − [102,105,110] Spinach juice Electric field strength: 9 kV/cm;

Frequency: 1 kHz;

Pulse width: 80 µs;

Time: 335 µsLowered microbial activation by 1.25 log CFU/mL. Decreased viscosity to 1.32 ± 0.06 mPa·s. Electrical conductivity is enhanced.

No change in pH and titrable acidity.

Increase in free amino acids.

Decrease in Mn content and increase in K content.[58] Effect of PEF on microbial, rheological, and physicochemical properties of vegetable juice/thick juice/ puree

-

PEF has demonstrated positive results in reducing microbial loads in vegetable juices, with mechanisms primarily involving electroporation and cell disruption. In spinach juice, a reduction of polyphenol oxidase activity by 44% and peroxidase enzyme activity by 43.52% was seen when compared to the untreated juice[58,59]. The positive effect of PEF on enzyme inactivation and microbial inactivation is due to the electroporation caused during the treatment, leading to reduced catalytic activity. The moderate temperature likely preserves the juice quality and retains the nutrients. In a separate study, PEF treatment resulted in a 1-log reduction in CFU/mL of aerobic microbial growth[106,10]. With a pulse width of 80 µs and a duration of 335 µs, PEF treatment has resulted in a 1.25 log reduction in microbial activity. Therefore, moderate processing conditions of PEF favour the reduction of microbes without impacting the quality of the juice[102]. PEF is highly effective for microbial inactivation, thereby reducing spoilage and making it a suitable option for the commercial-scale production of juices.

PEF treatments have the potential to influence the rheological properties of vegetable juices, depending on the processing parameters and the type of vegetable. In carrot-based products, PEF led to an increase in viscosity. In carrot puree treated at 305 kV/cm, a minimal rise of 1.48 ± 0.04 mPa·s was observed due to the release of pectin and polysaccharides[59,63]. Similarly, carrot mash treated at 0.8 kV/cm exhibited higher viscosity that could be influenced by the water binding capacity. Contrarily, in spinach juice, PEF reduced flowability, likely due to an increase in structural resistance[82,84,102,105]. These changes are influenced by the electroporation and molecular alterations during the process time. PEF tailors the rheological properties of vegetable juices, thereby improving the texture of the products and making them appealing to consumers.

PEF treatment enhances the functional and nutritional qualities of these items. No appreciable changes in pH or total soluble solids are observed in carrot juice, despite an increase in carotenoid and phenolic content[59,63]. Increased flavonoid, phenolic, anthocyanin, carotenoid, and chlorophyll content are all advantageous properties of spinach juice. Vegetable juices and purees benefit from PEF treatment in terms of stability and nutritional quality overall[59,63,105].

Spinach juice processed with PEF using specific parameters showed an increase in flavonoids, phenolics, anthocyanins, carotenoids, and chlorophyll concentration after PEF treatment. Specifically, chlorophyll concentrations from 36.30 ± 0.04 µg/ml to 40.58 ± 0.03 µg/ml, and chlorophyll b increased from 12.87 ± 0.01 µg/ml to 14.69 µg/ml. Therefore, PEF treatment prevented the pigments in the juice from deteriorating, indicating the maintenance of the spinach juice's colour and nutritional value[83,84,102,105]. Spinach juice treated with PEF showed a significant increase in electrical conductivity (EC) to 8.32 ± 0.04 ms/cm. However, titrable acidity (TA) and pH remained unchanged. Together with a rise in potassium (K) concentration to 398 ± 0.55, the PEF treatment also caused a drop in manganese (Mn) to 0.504 ± 0.02 and a reduction in free amino acids (FAA) by 2.05%. These results suggest that the PEF treatment of spinach juice can alter several of its properties, potentially impacting its microbiological and nutritional qualities[58].

PEF application of carrot puree caused the greatest increases in carotenoid bioaccessibility (18.7%), and phenolic bioaccessibility (100%) was seen with this treatment. Moreover, it led to a 70% improvement in the bioaccessibility of ferulic acid derivatives and an 80% increase in the bio accessibility of caffeic acid derivatives. The puree's microstructure changed as a result of the treatment, with smaller and irregular cells forming. The caffeic acid derivatives and ferulic acid derivatives were improved by 80% and 70% due to the treatment[107]. Carrot mash treated with PEF exhibited enhanced cell disintegration, ranging from 30% to 40%, compared to the control sample, and resulted in higher juice output. In addition, the content of total dissolved solids (TDS) increased from 8.1 ± 0.3 to 9.4 ± 0.5, and the content of total soluble solids (TSS) decreased to 2.6 ± 0.2 from 3.5 ± 0.5. In addition, the pH significantly dropped after PEF treatment to 5.86 ± 0.06 from 6.6 ± 0.2. These results imply that the quality and extractability of carrot mash could be enhanced by PEF treatment[108].

-

The application of both ultrasound treatments combined with pulsed electric fields resulted in improved processing and higher-quality outcomes. (Table 5) briefs the findings on the synergistic effect of PEF and US in different vegetables and processed juices[58,59]. The quality of sweet potato chips is enhanced when treated with both US and PEF. A significant reduction in oil uptake was observed, ranging from 32.3% to 40.3%. The acrylamide content was reduced by 55.28%. No significant changes were reported in terms of texture and colour properties[105,96]. Various effects were observed when high-power ultrasound and PEF were applied to potato chips, particularly during frying. During frying, the treatment produced more bubbles, which might improve texture. More importantly, it reduced the fat content of the fried potatoes by 24.7%, making them a healthier choice. Furthermore, the treatment improved the 675 nutritional profile and safety of the fried potatoes by reducing the production of the hazardous 676 chemical acrylamide by 66%. The combination of PEF and US improved the frying characteristics of potato chips, making it beneficial for industrial applications[96].

Table 5. Synergistic effect of pulsed electric field (PEF) and ultrasound (US) on whole vegetables and their juices.

Vegetables US conditions PEF conditions Findings Ref. Carrot US type: immersive sonication

Frequency: 21 kHz

Power: 180 W

Time: 20 min

Temperature rise: 2.4 ± 0.2 °C

US type: contact sonication

Frequency: 24 kHz

Power: 250 W

Time: 20 min

Temperature rise: 5.4 ± 0.6 °COutput voltage: 30 kV

Capacitance: 0.25 µF

Pulse width: 7 µs

Time: 20 s

Time interval: 2 sImproved electric conductivity.

Reduced drying time.

Retention of total carotenoid content.

Increased redness value.

Decreased yellowness value.[114] Sweet potato chips US type: ultrasonic probe

Power: 180 W

Frequency: 53 kHz

Temperature: 25 °C

Time: 30 minNo of pulses: 50

Electric field strength: 1 kV/cm

Input energy: 9.47 ± 0.5 kJ/kg

Voltage: 1.5 kV

Frequency: 2 Hz

Pulse width: 20 µs

Time: 0.2 sReduced oil uptake of chips.

No significant difference in color and texture parameters.

Increased reducing sugar content.

Reduced acrylamide content.[96] Potato US type: ultrasonic probe

Power: 1,000 W

Energy: 40 kJ/kg

Amplitude: 25 µm

Time: 180 sNo: of pulses: 12

Electric field strength: 1 kV/cm

Input energy: 1 kJ/kg

Voltage: 30 kV

Frequency: 2 Hz

Pulse width: 40 µs

Time: 480 µsIncreased number of bubbles while frying.

Reduced fat content.

Reduction in acrylamide content.[115] Spinach juice US type: ultrasonic bath

Power: 180 W

Frequency: 40 kHz

Time: 21 min

Temperature: 30 °CFlow rate: 60 ml/min

Electric field strength: 9 kV/cm

Frequency: 1 kHz

Pulse width: 80 µs

Time: 335 µs

Temperature: 30 °CIncreased total phenolic and flavonoid content.

Improved chlorophyll content.

Preserved antioxidants.

Inactivation of enzymes.

Increased carotenoids.

Enhanced anthocyanins.[66] Spinach juice US type: ultrasonic bath

Power: 200 W

Frequency: 40 kHz

Temperature: 30 ± 2 °C

Time: 21 min

Flow rate: 0.5 L/minElectric field strength: 9 kV/cm

Frequency: 1 kHz

Pulse width: 80 µs

Temperature: 30 ± 2 °C

Time: 335 µsIncrease in total free amino acids.

Enhanced mineral content.

Reduction in microbial inactivation.[68] In a study, spinach juice was treated with ultrasound at a power of 200 W, a frequency of 40 kHz, and a temperature of 30 ± 20 °C for 21 min, followed by PEF under the same conditions. This combined treatment improved total free amino acids and enhanced mineral content, while also reducing the microbial load, thereby improving safety and extending shelf life by maintaining vegetable quality[58]. These findings highlight the potential of using a combination of US and PEF treatments to significantly enhance the nutritional, functional, and overall quality of vegetables.

-

Ultrasound and PEF are promising non-thermal technologies for processing vegetables. The acoustic cavitation caused by US and the high-voltage electric fields in PEF leads to cell wall disruption and induces electroporation, resulting in microbial inactivation. Both US and PEF preserve bioactive compounds, such as phenolics, flavonoids, and carotenoids, improving the food safety of vegetable-processed products. They also enhance the rheological properties, such as increased viscosity and flow rate, which contribute to a better texture and consistency in vegetable-processed juice. The synergistic application has the potential to extend shelf life and improve the nutritional quality of vegetables and vegetable-processed juices. Despite these promising results, the application of PEF and US to a wider variety of vegetables, including roots, tubers, and leafy greens, remains unexplored. The future of ultrasound and PEF technologies in the vegetable processing industry holds great promise, offering innovative solutions to enhance food quality and safety, as well as the development of functional, nutritious food at an industrial scale.

The authors extend their gratitude to the Indian Institute of Packaging, Lucknow under the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India, for their valuable support and resources that facilitated the completion of this review paper. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not–for–profit sectors.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Dubey PK; methodology: Dubey PK; validation: Dubey PK; data curation: Dubey PK; visualization: Dubey PK, Mishra A, Shukla RN; draft manuscript preparation: Sushmitha M, Dubey PK; writing, review and editing: Sushmitha M, Dubey PK, Mishra A, Shukla RN; supervision: Dubey PK; project administration: Dubey PK. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data sharing and materials are the result of research and are properly referenced within the manuscript.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Authors contributed equally: Miriyala Sushmitha, Praveen Kumar Dubey

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Agricultural University, Zhejiang University and Shenyang Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Sushmitha M, Dubey PK, Mishra A, Shukla RN. 2025. Enhancing nutritional and functional properties of vegetables: a review on ultrasound and pulsed electric field effects. Food Innovation and Advances 4(4): 500−515 doi: 10.48130/fia-0025-0049

Enhancing nutritional and functional properties of vegetables: a review on ultrasound and pulsed electric field effects

- Received: 31 May 2025

- Revised: 04 November 2025

- Accepted: 05 November 2025

- Published online: 12 December 2025

Abstract: The growing significance of sustainable and efficient food processing has developed interest in non-thermal technologies, with ultrasound (US) and pulsed electric field (PEF) emerging as promising alternatives to conventional methods. These technologies offer significant advantages by enhancing food preservation without compromising nutritional value, while also being environmentally friendly and cost-effective, thereby meeting consumer demands. This review examines the physicochemical and bioactive properties of vegetables, highlighting the role of these technologies in preserving and enhancing their nutritional value. It also describes the various favourable changes caused by US and PEF processing regarding physicochemical properties, microbial inactivation, rheological properties, and biochemical effects, while preserving sensory attributes and pigments in whole vegetables as well as in processed vegetable juice products. Moreover, their synergistic combination has been effective in preserving the overall nutritional profile of different vegetables and their juices. However, the application of these technologies at an industrial scale is limited due to a lack of research. This review highlights the importance of these technologies and their potential uses. Further research is needed to refine and develop an understanding of the effectiveness of different parameters of US, PEF, and their synergistic effect on various vegetables, particularly green leafy vegetables, roots and tubers, and other types of vegetables.