-

The transcription initiation process involves interactions among various proteins, including transcription factors (TFs). Plant TFs serve as master regulators of developmental processes and responses to environmental stimuli. On the basis of their conserved DNA-binding domains, TFs are classified into several families, such as APETALA2/ethylene-responsive element binding protein (AP2/EREBP), basic region/leucine zipper (bZIP), MYB, WRKY, and zinc finger proteins. The bZIP family represents a major group of TFs. The number of bZIP TFs varies markedly among different plant species, ranging from fewer than 20 in lower plants to nearly 200 in polyploid crops (Supplementary Table S1). This variation is primarily shaped by differences in genome size and complexity, lineage-specific duplication events, and evolutionary adaptations to ecological niches. For example, whole-genome and segmental duplications in species such as Glycine max (soybean) and Gossypium hirsutum (cotton) have greatly expanded the bZIP family, whereas woody perennials like Vitis vinifera (grapevine) and Populus trichocarpa (poplar) often have fewer but highly specialized members[1,2]. Functional diversification following duplication has allowed bZIP subfamilies to acquire roles in stress responses, metabolism, and development, contributing to species-specific regulatory networks. Therefore, the observed differences in bZIP gene counts across taxa reflect both the genomic architecture and adaptive selection pressures.

TFs are DNA-binding proteins that regulate gene expression by interacting specifically with cis-acting elements in promoter regions. Transcriptional activators, including bZIPs, typically have two main functional domains: A DNA-binding domain and a transcriptional activation domain. Studies have shown that bZIPs play critical roles in plants' development and biotic and abiotic stress responses throughout their lifecycle. The DNA-binding domain of the bZIP family, known as the basic leucine zipper, determines binding specificity. It comprises a leucine zipper that enables dimerization and a basic region that binds to DNA. In the leucine zipper, a hydrophobic leucine residue appears every seven amino acids along the same side of the α-helix, facilitating the formation of a clamp-like dimer that binds DNA. The basic region anchors to the DNA's major groove. The DNA-binding specificity of bZIP TFs is governed by this domain, which recognizes cis-elements containing the core ACGT motif, such as CACGTG (G-box), GACGTC (C-box), and TACGTA (A-box)[3].

-

Plants are frequently challenged by abiotic stresses such as drought, low temperature, and salinity, as well as biotic stresses like diseases and insect pests. These stresses disrupt normal plant growth and development, often causing damage or even death. Therefore, understanding plants' responses and resistance to stress is crucial. Plant cells perceive stress signals, such as water deficit or high salinity, through receptors and activate signal transduction pathways, with abscisic acid (ABA) playing a key role in regulating gene expression under abiotic stress. Stress also affects transcriptional regulation by activating or repressing TFs and inducing epigenetic modifications. Physiologically, plants respond by synthesizing osmotic regulators like proline and betaine, activating antioxidant defense systems to scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS), and producing secondary metabolites like anthocyanins[4]. Additionally, stress leads to modifications in the cell wall's composition and changes in roots' development and morphology to enhance adaptability. TFs are central to these responses, regulating downstream gene expression to facilitate adaptation to environmental challenges. Among these, the bZIP family is one of the most extensively studied, with numerous reports highlighting its role in modulating stress tolerance through various mechanisms. This review summarizes the key roles of bZIP TFs in regulating plants' stress responses.

Drought stress responses

-

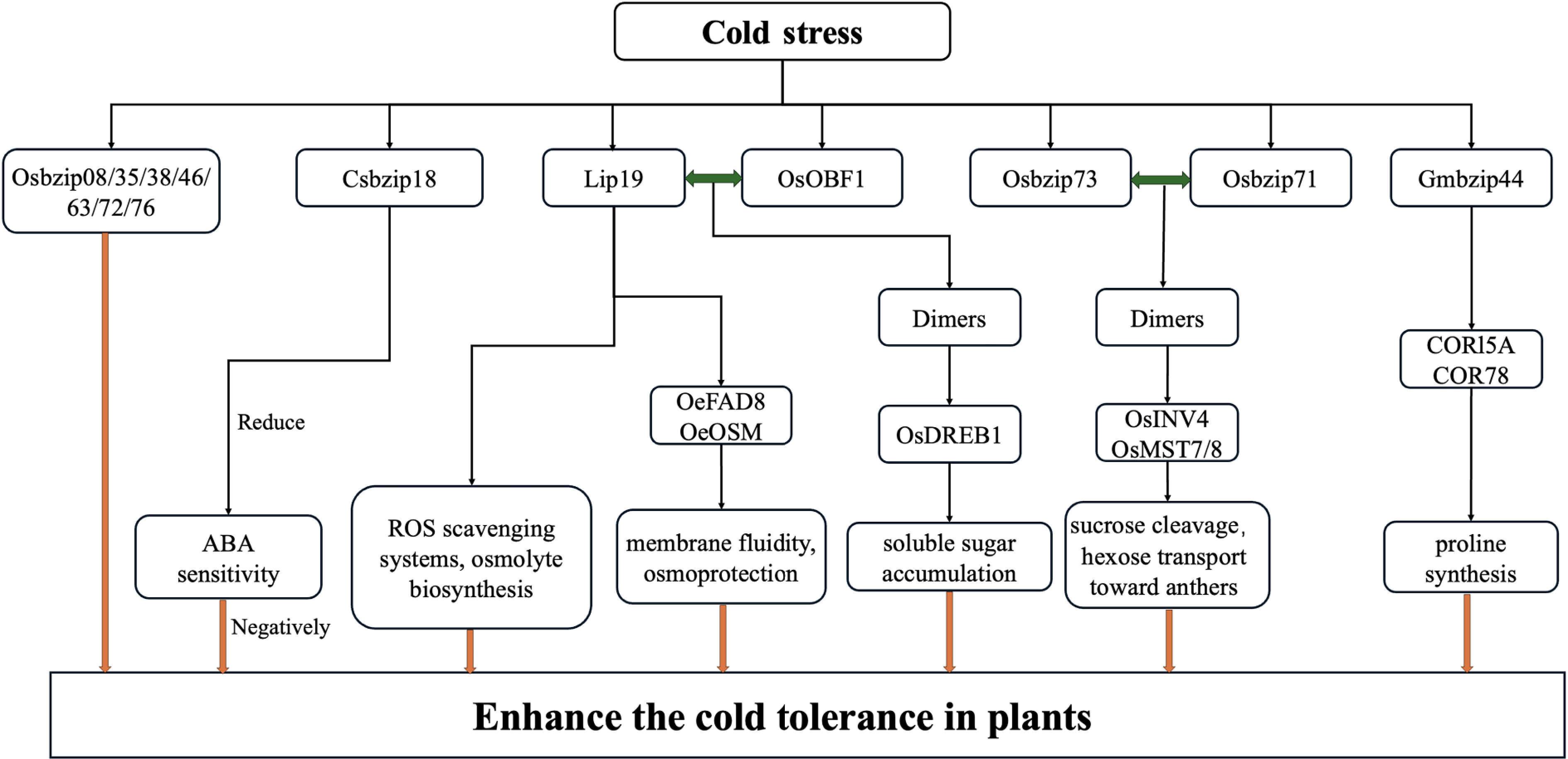

Plants can mitigate drought stress through several mechanisms, including enhanced antioxidant enzyme activity, increased osmolyte accumulation, and regulation of endogenous hormone levels (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

bZIPs respond to drought stress and salt stress. Abbreviations: PPO, polyphenol oxidase; POD, peroxidase; SOD, superoxide dismutase; CAT, catalase; ERS, endoplasmic reticulum stress; PYR, pyrabactin resistance; PYL, PYR1-like; RCAR, regulatory component of ABA receptor; PP2C, protein phosphatase 2C; SnRK2, SNF1-related protein kinase 2; ABF, ABRE-binding factors; AREB, ABRE-binding proteins; JA, jasmonic acid.

Under drought stress, the production of ROS in crops leads to lipid peroxidation of the cell membranes, disrupting normal plant metabolism. In plants, drought stress tolerance is positively correlated with ROS-scavenging capacity. To mitigate the harmful effects of ROS, plants protect the integrity of cell membranes, proteins, and metabolic enzymes by accumulating antioxidant enzymes. Therefore, peroxidase (POD) levels can, to some extent, reflect a plant's drought resistance. Osmotic substances include soluble sugars, proline, betaine, and inorganic ions such as Ca2+, Na+, and Cl−. These solutes, which exhibit affinity within plant cells, rapidly accumulate under abiotic stress to maintain cell turgor and protect cellular structures. Studies have shown that bZIPs can enhance drought resistance by regulating POD activity and osmotic substances. For example, the AtbZIP62 mutant exhibited greater susceptibility to drought stress than wild-type Arabidopsis thaliana, as AtbZIP62 regulates catalase (CAT), POD, and polyphenol oxidase (PPO)-like activities and increases proline and malondialdehyde (MDA) levels, thereby enhancing drought resistance[5]. Heterologous expression of VvABF2 in A. thaliana significantly improved ROS scavenging capacity, reduced membrane damage, and enhanced drought tolerance[6]. Similarly, GhABF2 in cotton has been shown to boost the activity of peroxidases such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and CAT, improving drought resistance[7]. Likewise, FtbZIP83, AhAREB1, and ThbZIP1 improve drought tolerance by enhancing ROS scavenging and osmoregulatory capacity[8−10].

Hormones are key signaling molecules in plants that regulate signal transduction and play crucial roles in plants' stress responses. ABA is central to plants' stress responses, with bZIP TFs playing a vital role in ABA signaling. Specifically, the A subfamily of bZIPs acts as a master regulator in ABA-dependent responses and mediates hormone-driven drought responses. As noted earlier, several bZIP TFs bind to ABA-responsive elements (ABREs) and function in drought stress through the ABA signaling pathway. ABRE-binding factors (ABFs) and AREBs are induced by abiotic stresses and play a key role in regulating the expression of downstream stress-responsive genes via ABA signaling, thus enhancing drought resistance[11]. ABFs/AREBs participate in ABA-mediated stress responses activated by SnRK2s (SNF1-related protein kinases). Studies have shown that ABA signaling is regulated by the phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of SnRK2s[12]. Endogenous ABA activates receptor proteins, such as PYR (pyrabactin resistance), RCAR (regulatory components of ABA receptors), and PYL (PYR1-like), which interact with PP2Cs (Type 2C protein phosphatases) to release SnRK2s. These kinases then phosphorylate and activate ABF/AREB TFs. The activated ABFs/AREBs induce ABA-responsive genes to regulate stress responses[13]. Arabidopsis srk2d/e/i triple mutants exhibit significantly reduced drought tolerance, caused by impaired SnRK phosphorylation of AREB1. This limits the binding of AREB1 to ABREs, weakening downstream stress gene regulation. In addition to Arabidopsis, numerous bZIP TFs that bind ABREs have been identified as responsive to water stress in other species. For example, overexpression of TaAREB3 in Arabidopsis enhances ABA sensitivity and drought resistance[14]. In rice (Oryza sativa), OsbZIP23 conferred ABA-dependent drought and salinity tolerance and shows strong potential for improving stress resistance through genetic modification[15]. Overexpression of OsbZIP72 in rice significantly enhances ABA-responsive genes' expression and drought resistance compared with wild-type plants[16]. Hsieh et al. reported that the tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) bZIP TF SlAREB binds ABREs, mediating ABA signaling and improving drought resistance[17]. Overexpressing VlbZIP30 from grapevine in Arabidopsis enhances drought resistance via G-box (CACGTG)-mediated regulation of ABA-responsive genes[18]. In tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum), FtbZIP83 and FtbZIP5 act as positive regulators of drought resistance through ABA signaling, directly binding to FtSnRK2.6/2.3 and FtSnRK2.6, respectively[9,19]. Interestingly, bZIP TFs not only act as downstream components of ABA signaling but also contribute to its negative feedback regulation. Some studies show that ABFs can rapidly induce PP2Cs under ABA treatments, thereby negatively regulating ABA signaling. In rice, OsbZIP23 was also found to positively regulates OsPP2C49, providing further evidence of negative feedback regulation in ABA signaling[20]. Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) CaATBZ1 negatively regulated drought responses by regulating ABA-induced stomatal closure[21].

In addition, some bZIP TFs also participate in other plant hormone signaling pathways and enhance drought resistance. Their regulatory roles involve cross-talk among the gibberellic acid (GA)/brassinosteroid (BR), salicylic acid (SA), and auxin signaling cascades, including limiting shoot growth via hormonal balance, mitigating oxidative stress through SA-induced antioxidant biosynthesis, and hydraulic adjustment mediated by auxin-driven root patterning[22]. In Arabidopsis, the AtTGA2/3/5/6-NPR1 protein interaction enhances drought tolerance by activating jasmonic acid (JA)-responsive genes, boosting ROS scavenging, and reducing drought-induced oxidative membrane damage through coordinated molecular mechanisms. In maize (Zea mays), ZmbZIP4 positively regulates gibberellin biosynthesis, thereby improving resistance to abiotic stress[23]. MdIPT5b encodes the rate-limiting enzyme isopenyltransferase in the cytokinin biosynthesis pathway and represses gene expression, thus delaying drought-induced premature leaf senescence by reducing oxidative damage and sustaining plant growth. This contributes to drought and salt stress responses via the cytokinin pathway[24].

Salt stress responses

-

As a major abiotic stressor, salt stress impairs plants' growth and development through interconnected mechanisms, including ion toxicity, osmotic imbalance, oxidative stress, and disruption of nutrient homeostasis (Fig. 1).

bZIP TFs act as central regulators in plants' responses to salinity stress. By integrating ABA signaling cascades, ROS regulatory networks, and ion homeostasis, these transcriptional modulators coordinate the expression of stress-responsive genes to mediate adaptation to ionic and osmotic challenges under saline conditions. Hsieh et al. functionally characterized the tomato bZIP TF SlAREB, demonstrating its role in reprogramming stress-responsive gene networks and conferring salinity tolerance in both Arabidopsis (heterologous) and tomato (homologous) systems[17]. Transgenic overexpression of MhNPR1 from Malus hupehensis in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) confers dual stress tolerance by alleviating ionic imbalance and osmotic stress[25]. Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) CabZIP25 is strongly induced by abiotic stresses and phytohormones and positively regulates salt tolerance; its expression level correlates with chlorophyll content in peppers[26]. Tamarix hispida exhibits halophytic adaptation through integrated physiological mechanisms, enabling growth under saline conditions. The Tamarix hispida ThbZIP1 TF enhances POD and SOD activity, mitigating oxidative stress during exposure to salinity[27].

Salinity stress induces ABA biosynthesis, which promotes adaptation through SnRK2-mediated phosphorylation of bZIP TFs, enabling their nuclear translocation and activation of stress-responsive genes. Overexpression of OsbZIP71 in Oryza sativa enhanced salinity tolerance by directly targeting the OsNHX1 and COR413-TM1 promoters, activating their transcription[28]. OsNHX1 contributes to Na+ homeostasis via ion compartmentalization and mediates osmotic regulation, offering dual protective mechanisms under salinity stress. OsbZIP71-overexpressing lines show hypersensitivity to ABA and osmotic stimuli, along with transcriptional activation of ABA-inducible markers (RD29B, RAB18, HIS1-3), highlighting its role as an ABA-responsive transcriptional activator that integrates stress signaling for improved crop resilience to salinity[29]. Overexpression of IbbZIP1 in Arabidopsis elevated ABA accumulation, conferring tolerance to both salinity and drought through ABA-mediated signaling[30]. Cotton plants overexpressing GhABF2 show increased activities of the key ROS-scavenging enzymes SOD and CAT, resulting in improved salinity tolerance via enhanced mitigation of oxidative stress[7].

A key transcriptional regulator orchestrates salinity-responsive gene networks in plants. Rolly et al. demonstrated that AtbZIP62 transcriptionally suppresses salinity responses beyond canonical ABA signaling. bZIP TFs also mediate salinity responses through ABA-independent mechanisms[31]. For instance, expressing the AtbZIP60 gene enhances salt tolerance in rice by upregulating Ca2+-dependent protein kinase genes (OsCPK6/9/10/19/25/26) under salt stress. This suggests that overexpression of AtbZIP60 in transgenic cell lines enhances salt tolerance by modulating Ca2+-dependent protein kinase genes. In Arabidopsis, AtbZIP17 TF is reportedly activated in response to salt stress, with genetic evidence supporting its role in a conserved stress signaling pathway. Under salinity stress, endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-localized AtbZIP17 undergoes proteolytic processing, releasing its DNA-binding domain for nuclear translocation to activate salt-responsive targets including ATHB-7. An activated form of AtbZIP17 has been shown to confer salt tolerance in Arabidopsis[32]. Furthermore, AtbZIP24 has been functionally validated as a negative regulator of salinity tolerance in Arabidopsis by repressing salt overly sensitive (SOS) pathway-associated genes[31].

Notably, some studies have reported contradictory results regarding the roles of identical bZIP transcription factors under different stress conditions. For example, AtbZIP62 has been described as a positive regulator of drought tolerance through the modulation of ROS-scavenging enzymes' activity and osmolyte accumulation[5], whereas other studies suggest that its overexpression may impair plant growth under prolonged or high-intensity drought stress[24]. Such inconsistencies may arise from differences in experimental design, including the severity and duration of stress treatments, as well as variations in the plants' developmental stages and tissue-specific expression patterns. Similarly, in rice, OsbZIP23 is generally regarded as a positive regulator of ABA-dependent drought and salt responses[15], yet feedback regulation through PP2C induction indicates a potential negative role in ABA signaling under certain contexts[20]. These discrepancies highlight the importance of considering the plants' genetic background, the environmental conditions, and the intensity of stress when interpreting functional studies of bZIP TFs. Future investigations integrating standardized stress treatments, multi-omics analyses, and cross-species comparisons will be essential to reconcile these divergent findings and establish a clearer mechanistic framework.

Low-temperature stress responses

-

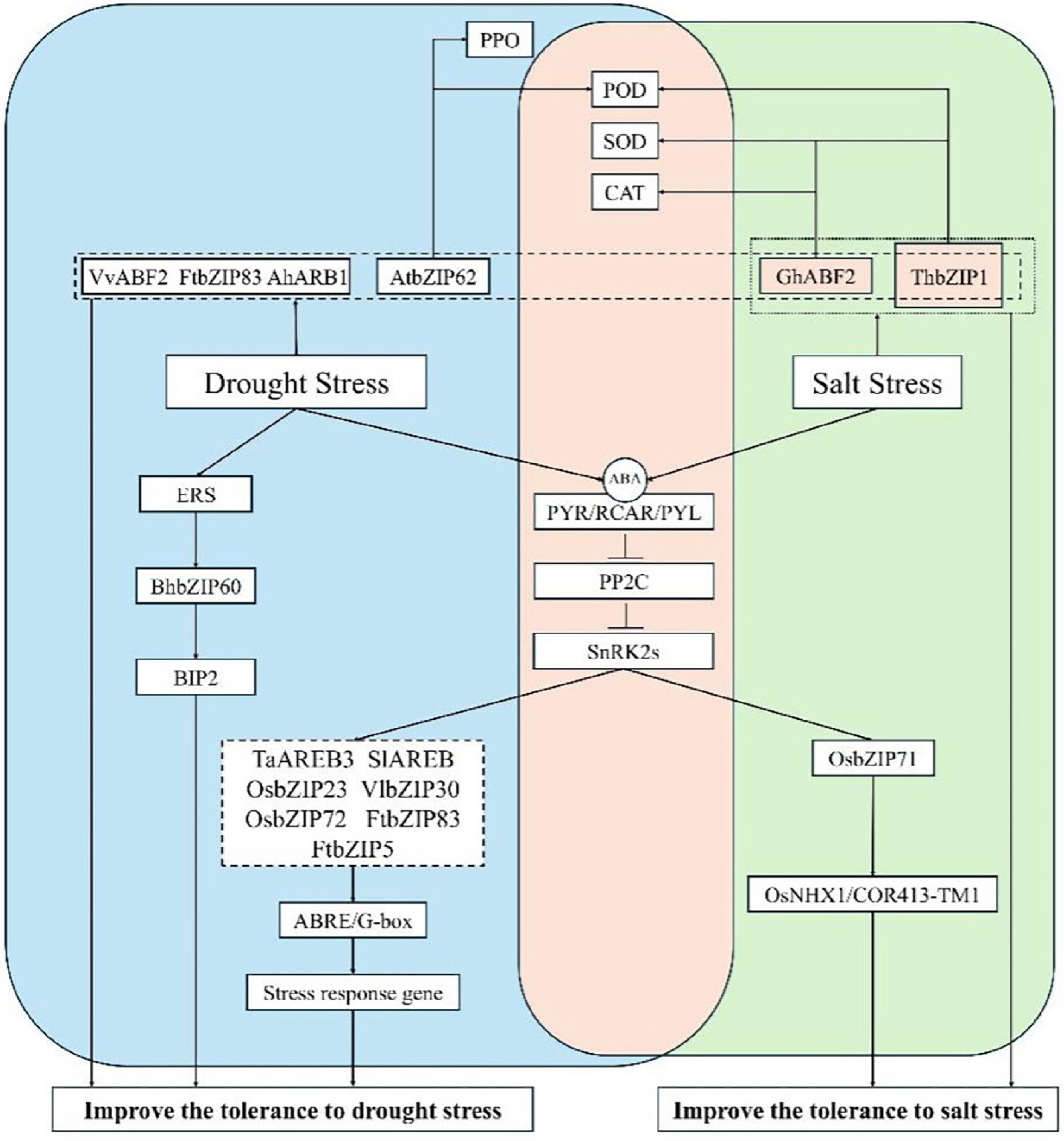

Low-temperature stress severely limits plants' growth and productivity, forcing plants to activate adaptive responses through transcriptional reprogramming (Fig. 2).

bZIP transcription factors function as pivotal regulators, integrating ABA signaling, antioxidant defense, and cryoprotective gene expression to enhance cold tolerance. Within the S1-bZIP subfamily, low-temperature-induced protein 19 (LIP19) is strongly induced under cold conditions in monocots, and functional studies in O. sativa confirm its central role in cold-responsive regulatory networks[33]. OsOBF1, a paralog of LIP19 within the S1-bZIP family in O. sativa, exhibits temperature-dependent functional synergy with LIP19 in thermosensory regulation. At normal temperatures (25 °C), OsOBF1 maintains constitutive transcriptional activity to regulate basal temperature signaling homeostasis. During cold exposure (4–10 °C), LIP19 undergoes structural changes enabling heterodimerization with OsOBF1, thereby allosterically modulating its DNA-binding specificity and reprogramming transcriptional networks toward cold acclimation. Mutational studies show that loss of LIP19 function leads to reduced survival at 4 °C, whereas co-expression of LIP19 and OsOBF1 restores cold tolerance by activating OsDREB1 genes and enhancing soluble sugar accumulation. In Olea europaea, increased expression of OeLIP19, together with OeFAD8 (a fatty acid desaturase) and OeOSM (osmotin), has been associated with enhanced membrane fluidity and osmoprotection in cold-acclimated leaves of this evergreen perennial[34]. Recent advances in the functional genomics of rice have identified multiple bZIP TFs (OsbZIP08, OsbZIP35, OsbZIP38, OsbZIP46, OsbZIP63, OsbZIP72, OsbZIP73, and OsbZIP76) as key regulators of chilling stress adaptation through both ABA-dependent and independent pathways[35]. Similarly, low-temperature treatment (4 °C for 24 h) significantly induces the expression of RsLIP19, a bZIP TF in Raphanus sativus roots, which enhanced chilling tolerance by modulating ROS scavenging systems and osmolyte biosynthesis[36].

Additionally, bZIP TFs participate in cold stress responses in various ways. For example, in soybean, GmbZIP44 activates the expression of the low-temperature-regulated genes CORl5A and COR78, promoting proline synthesis and enhancing chilling tolerance[37]. In Oryza sativa, OsbZIP73 is among the best characterized bZIPs in cold tolerance at the reproductive stage. Under chilling conditions, the japonica allele bZIP73^Jap physically interacts with OsbZIP71 to form heterodimers; this complex enhances the expression of sugar metabolism genes such as OsINV4 (cell wall invertase) and OsMST7/8 (monosaccharide transporters) to promote sucrose cleavage and hexose transport toward the anthers[35]. In contrast, CsbZIP18 functions as a negative regulator of ABA-mediated cold stress signaling in Cucumis sativus. Heterologous overexpression of CsbZIP18 in Arabidopsis reduced ABA sensitivity and impaired cold acclimation compared with wild-type plants under freezing conditions[35].

In conclusion, bZIP transcription factors function as central regulators of plants' cold stress tolerance by integrating ABA signaling, ROS detoxification, and expression of cryoprotective genes. Both positive and negative regulators exist across species, reflecting functional diversity. Future research should clarify their hierarchical networks and molecular interactions to improve crops' resilience under low-temperature conditions.

Heat stress responses

-

Heat stress disrupts proteins' stability, membrane integrity, and photosynthetic efficiency in plants.

To cope with high temperatures, bZIP transcription factors integrate ER stress signaling, activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR), and antioxidant defense, thereby orchestrating transcriptional networks that are essential for thermotolerance and survival under elevated temperatures. Zhang et al. (2008) reported that transgenic Arabidopsis lines overexpressing ABP9 exhibited improved photosynthetic efficiency under heat shock compared with wild-type plants, attributed to ABP9's role in stabilizing the Photosystem II (PSII) complex and reducing thylakoid membrane disorganization[38]. The ER is a key organelle for protein biosynthesis in eukaryotic cells. Under biotic or abiotic stress, misfolded proteins accumulate abnormally in the ER lumen, triggering ERS through the UPR. This condition leads to excess ROS production and programmed cell death. Mechanistically, the activation of canonical Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress (ERS) biomarkers, including molecular chaperones such as binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP) and calnexin (CNX), constitutes a critical adaptive response. These chaperones mitigate proteotoxic stress through two coordinated pathways: Targeted degradation of oxidatively damaged polypeptides and upregulation of antioxidant defense systems[39,40]. Studies have shown that bZIP TFs from the K subfamily (e.g., AtbZIP60 in Arabidopsis and OsbZIP74 in rice) activate ERS-responsive genes by binding directly to ER stress elements (ERSEs) (e.g., CCAAT-N9-CCACG; ERSE-II, ATTGG-N-CCACG; UPRE-I, CAGCGTG; UPRE-II, TCATCG), thereby mitigating ERS[41]. In Arabidopsis, the inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1) kinase-ribonuclease is activated by heat stress via recognition of misfolded proteins in the ER lumen. Its C-terminal domain splices AtbZIP60 mRNA, generating a transcript that encodes an active TF—a conserved UPR mechanism that restores ER homeostasis. The IRE1-processed AtbZIP60 mRNA isoform functions as a transcriptional activator, regulating UPR-associated genes to mitigate ERS-induced cellular damage[42]. Maize bZIP60 knockdown lines showed reduced thermotolerance under heat stress, indicating its essential role in heat stress adaptation via UPR activation[43]. ERS is also involved in drought stress responses. A strong correlation has been observed between ER stress and drought resistance[44−46]. ERS modulates drought tolerance through multiple mechanisms. For example, heterologous expression of BhbZIP60S in Arabidopsis upregulates the ER stress marker BiP2, enhancing drought tolerance, and deletion of ER stress-responsive cis-elements within the 5'-untranscribed region (UTR) of maize ZmPP2C-A10 improves drought resistance. Conversely, virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) of the ER chaperone CaBiP1 in pepper increases ROS and MDA levels, impairing drought adaptation[39,45,47].

Heavy metal stress responses

-

The toxicity of heavy metals, such as cadmium (Cd) and copper (Cu), poses severe threats to plants' growth and development by inducing oxidative stress, disrupting ion homeostasis, and damaging cellular structures. bZIP TFs function as key regulators in these processes, modulating detoxification, ion transport, and ROS scavenging systems. In tobacco, overexpression of NtbZIP62 improves Cd tolerance by inducing antioxidant enzymes and phytochelatin synthase, which chelate Cd and reduce ROS-induced damage[48]. Similarly, in the Cd-hyperaccumulator Sedum plumbizincicola, SpbZIP60 enhances tolerance by promoting lignification of root cell walls, thereby restricting Cd influx[49]. These results indicate that bZIP TFs orchestrate multiple protective mechanisms to mitigate heavy metal toxicity.

In addition to Cd and Cu detoxification, bZIP TFs also play a central role in zinc homeostasis. Zinc (Zn) is an essential micronutrient that functions as a structural motif and catalytic cofactor in numerous proteins, and its deficiency leads to oxidative damage, genomic instability, and reduced yield. In Arabidopsis, bZIP19 and bZIP23 act as master regulators of Zn deficiency responses, sensing Zn2+ via their N-terminal zinc-sensing modules (ZSMs) and activating downstream transporters such as ZIP1[50]. Notably, reduced expression of bZIP19 and bZIP23 increases Zn and Cd accumulation in roots and shoots, further confirming their dual roles in nutrient balance and heavy metal detoxification[51].

In summary, bZIP TFs function as versatile regulators of abiotic stress adaptation, including drought, cold, heat, salinity, and heavy metal toxicity. Their primary roles include modulating ABA signaling, ROS homeostasis, ion transport, and secondary metabolism. Both positive and negative regulatory functions exist across bZIP subgroups, highlighting their complexity and functional diversity. Recent studies on AtbZIP60, ZmbZIP29, OsbZIP50, AtbZIP17, and OsbZIP68 provide new insights into the molecular mechanisms of abiotic stress regulation. However, unresolved issues remain regarding pathway cross-talk, redundancy among subfamily members, and integration with epigenetic regulation. Future research should employ multi-omics and genome editing approaches to systematically dissect these mechanisms and develop stress-resilient crops.

Biotic stress responses

-

In addition to coordinating abiotic stress adaptation, the bZIP TF family regulates biotic stress responses. Notably, these transcriptional regulators positively influence pathogen resistance through SA- and ABA-mediated signaling modules, indicating their dual functionality in stress cross-talk. SA, synthesized as a phytoimmune signal upon pathogen attack, orchestrates systemic acquired resistance (SAR) via transcriptional reprogramming, thereby conferring broad-spectrum disease resistance in plants. SA also induces the accumulation of excess pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins in Arabidopsis, which play a key role in disease defense.

TGACGmotif-binding factor (TGA) TFs belonging to the D subfamily of bZIPs play a key role in the SA signaling pathway[1]. Upon pathogen infection, the SA level in plants rises sharply, inducing the dissociation of intracellular NPR1 oligomers into monomers. As a transcriptional coactivator, the NPR1 monomer binds to TGA TFs, enhancing their binding affinity and stability with the target gene promoters (containing as-1-like elements). This process strongly activates the expression of downstream defense genes, such as PR-1[52]. Zhang et al. demonstrated the redundancy and function of TGA2, TGA5, and TGA6 in SAR. Knockout of these genes adversely affected PR gene expression and pathogen resistance in Arabidopsis[53]. TabZIP74 mRNA splicing is triggered by ER stress, which is induced by Pst (Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici) infection and wounding. Thus, TabZIP74 participates in the ABA pathway to regulate the defenses of wheat (Triticum aestivum) against Pst[54]. Moreover, other studies proved that OsbZIP1 enhances rice's resistance to blast disease through the SA signaling pathway[55]. OsbZIP1 expression is induced by rice blast infection, and it responds rapidly to SA, JA, and ABA. Its role in enhancing resistance is mediated through an SA-dependent signaling pathway[55].

bZIP TFs also play crucial roles in integrating stress signaling with herbivory defense. In Arabidopsis, AtbZIP10 interacts with JA-regulated pathways while balancing ROS accumulation, thereby strengthening cell wall barriers and enhancing resistance to leaf-chewing pests[56]. Similarly, AtbZIP11 influences amino acid metabolism and the synthesis of phenylpropanoid-derived compounds, altering the nutritional and chemical profiles to deter herbivores. Furthermore, specific bZIP subfamilies act as central regulators of JA-responsive defense programs[57]. In particular, Arabidopsis Class II TGAs (TGA2/5/6) function as essential activators of the JA/ethylene branch, driving the expression of PDF1.2 and b-CHI via the ERF1/ORA59 node and forming a TGACG-box–centered transcriptional module for antiherbivory defenses. Supporting this, feeding assays with Spodoptera exigua demonstrated that the tga2/5/6 triple mutant displays altered expression of JA/SA markers, confirming the role of TGAs in modulating JA-dependent transcription during herbivore attack[58]. At the molecular level, herbivory-induced jasmonoyl-L-isoleucine (JA-Ile) promotes COI1-mediated degradation of the jasmonate ZIM domain (JAZ), releasing ethylene response TF (ERF) and MYC regulators, whereas TGAs cooperate at the target promoters to potentiate the expression of PDF12/VSP2[59]. Collectively, TGA bZIPs act as hubs linking JA signaling to direct defenses, including proteinase inhibitors and antimicrobial proteins, thereby enhancing plants' resistance under insect pressure[59].

Plants are constantly exposed to diverse environmental challenges, including abiotic stresses such as drought, salinity, temperature extremes, and heavy metal toxicity, as well as biotic stresses from pathogens and herbivores (Table 1). To cope, they have evolved sophisticated regulatory networks that integrate hormonal signaling, transcriptional reprogramming, and metabolic adjustments. The central mechanisms involve ABA- and JA-mediated cascades, activation of ROS scavenging systems, and induction of protective metabolites such as proline, flavonoids, and lignin. Within these networks, bZIP TFs act as pivotal hubs, linking upstream signal perception to downstream gene expression, thereby regulating osmotic balance, antioxidant defense, protein folding, and immune responses. Despite significant advances, several challenges remain. Many studies focus on single-gene characterizations, leaving the questions about functional redundancy and cross-talk among bZIP subgroups unresolved[11]. Moreover, most findings are based on model species such as Arabidopsis thaliana and rice, whereas crop-specific roles and ecological contexts are less explored[35]. Another critical gap is the limited understanding of spatiotemporal regulation, including how bZIPs integrate developmental cues with stress signaling in distinct tissues or stages[33].

Table 1. Roles of bZIP transcription factors in abiotic stress and biotic stress responses across species.

Stress type Key bZIP members Species Subgroup Mechanistic role Abiotic stress Drought AtbZIP62, VvABF2, FtbZIP83, AhAREB1, ThbZIP1, GhABF2, FtbZIP83, FtbZIP5, OsbZIP23, VlbZIP30 Arabidopsis thaliana, Vitis vinifera, Gossypium hirsutum, Fagopyrum tataricum A ABA-SnRK2-AREB pathway activation; ROS scavenging; osmolyte accumulation Salinity OsbZIP23, OsbZIP71, SlAREB, ThbZIP1, CabZIP25 Oryza sativa, Solanum lycopersicum, Tamarix hispida, Capsicum annuum A/K ABA-responsive regulation; Na+/H+ homeostasis; activation of antioxidant enzymes Low temperature LIP19, OsOBF1, RsLIP19,

GmbZIP44, CsbZIP18Oryza sativa, Raphanus sativus, Glycine max, Cucumis sativus S1 Cold-inducible transcription; heterodimerization (LIP19-OBF1); ROS scavenging; proline biosynthesis Heat AtbZIP60, OsbZIP74,

BhbZIP60, TabZIP74Arabidopsis thaliana, Oryza sativa, Boea hygrometrica, Triticum aestivum K ER stress-induced splicing; activation of UPR genes; protein folding; ROS homeostasis Heavy metal AtbZIP19, AtbZIP23,

OsbZIP48, ThbZIP2Arabidopsis thaliana, Oryza sativa, Tamarix hispida F / A Regulation of zinc homeostasis and metal chelation; activation of antioxidant and phytochelatin genes to alleviate metal-induced oxidative stress Biotic stress Pathogen defense TGA2/5/6, OsbZIP1, TabZIP74 Arabidopsis thaliana, Oryza sativa, Triticum aestivum D SA-dependent systemic acquired resistance (SAR); NPR1 interaction; PR gene activation Herbivory defense AtbZIP10, AtbZIP11, TGA2/5/6 Arabidopsis thaliana D/S Integration of JA/ET signaling; modulation of ROS balance; regulation of phenylpropanoid; amino acid metabolism bZIP TFs hold great potential for molecular breeding and genome editing strategies aimed at developing stress-resilient crops. For example, manipulation of bZIP genes via clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas) mediation could enhance drought or salinity tolerance without compromising yield[60]. In addition, synthetic biology approaches could exploit bZIP-controlled promoter elements to fine-tune stress-responsive genes' expression in transgenic lines. Future research should prioritize integrated multi-omics (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics) to construct holistic regulatory models. Comparative studies across species will be essential to identify conserved versus species-specific regulatory nodes. Finally, an important frontier lies in exploring how bZIPs participate in stress memory and priming, which may provide novel strategies for sustainable agriculture under climate change.

-

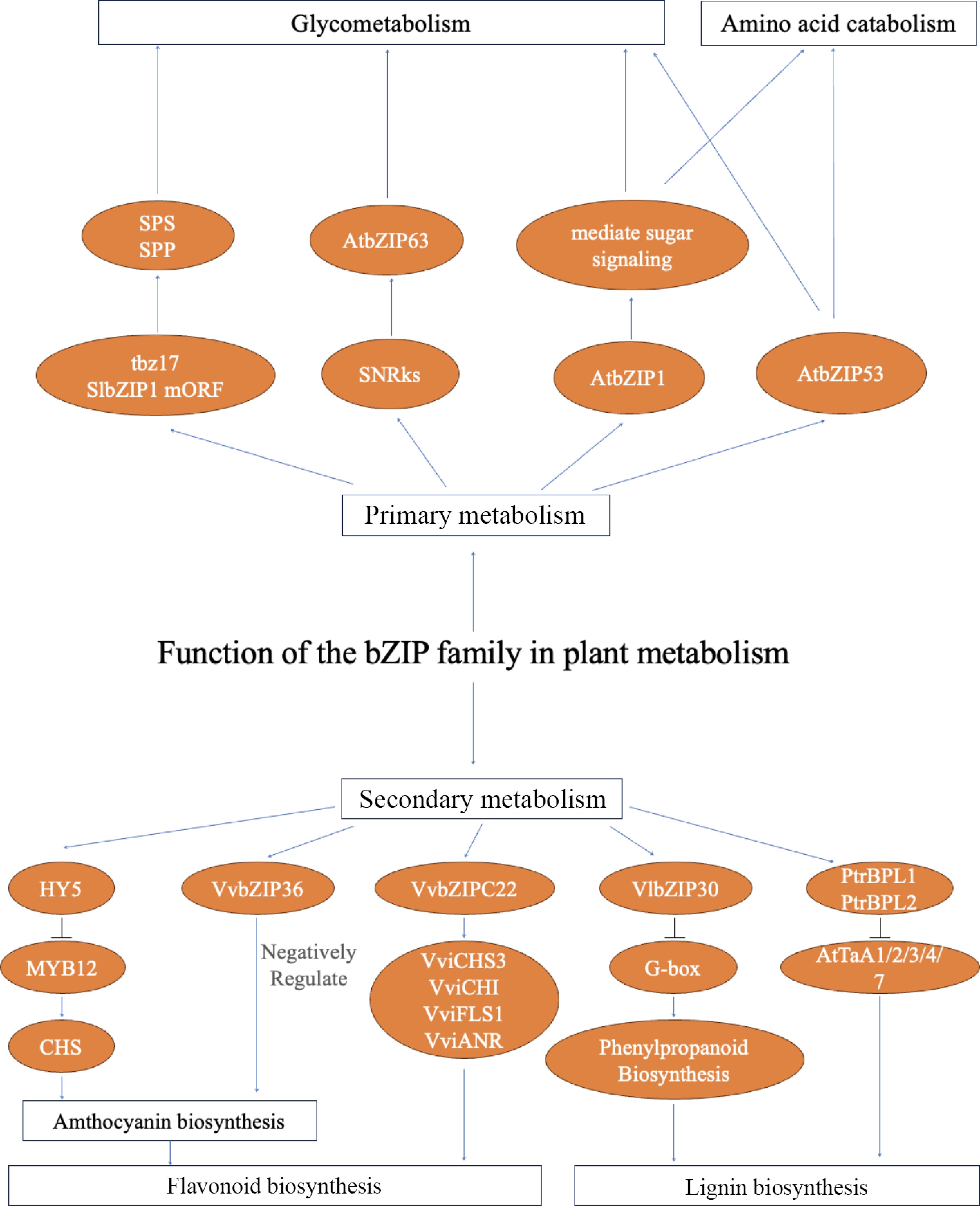

In plants, metabolism consists of primary and secondary metabolism. Primary metabolism supports growth and development, producing essential compounds like sugars and amino acids. Secondary metabolism, derived from the primary pathways, generates products such as alkaloids and pigments, which are often associated with stress resistance. bZIP TFs are closely linked to plant metabolism (Fig. 3).

bZIPs involved in primary metabolism

-

The S1-group bZIP family (including AtbZIP1, AtbZIP11, AtbZIP44, AtbZIP53, and bZIP63) plays a regulatory role in glucose metabolism and sugar signaling pathways[33]. AtbZIP1, a sugar-responsive gene, mediates sugar signaling and influences gene expression, plant growth, and development[61]. Previous studies have shown that overexpression of the tbz17 and SlbZIP1 micro Open Reading Frame (mORF) upregulates genes encoding sucrose phosphate synthase (SPS) and sucrose phosphate phosphatase (SPP), while silencing tbz17 down-regulates these genes[62]. The C/S1 network responds to low energy or nutritional starvation signals, which are mediated by SnRK1, HXK1 (HEXOKINASE 1), and the sucrose-induced repression of translation (SIRT) mechanism[11]. For example, bZIP63 is regulated by SnRK-mediated phosphorylation, which affects the target genes' expression and primary metabolism. A bZIP63 knock-out mutant exhibited starvation-related phenotypes[63]. bZIP1 and bZIP53 reprogram primary carbon and nitrogen metabolism after salt treatment, influencing gluconeogenesis and amino acid catabolism[64].

Despite these advances, the regulatory mechanisms of S1-bZIPs in primary metabolism remain only partially understood. The molecular determinants of target gene specificity are not well defined, as AtbZIP1 and AtbZIP53 regulate overlapping pathways but display distinct outputs[64]. It is also unclear how S1-bZIP–mediated sugar signaling is integrated with hormone pathways such as those associated with ABA and gibberellic acid (GA), leaving gaps in our understanding of stress adaptation[11]. Furthermore, although knockout studies such as bZIP63 suggest starvation phenotypes, it remains unresolved whether these reflect functional redundancy or unique contributions within the S1-group[33,63]. Future work should combine structural biology, transcriptomics, and mutant analyses to clarify how S1-bZIPs balance energy status with growth.

In summary, S1-group bZIPs serve as central hubs linking sugar signaling with nutrient and stress responses, coordinating plant growth with metabolic homeostasis under fluctuating environmental conditions.

bZIPs involved in secondary metabolism

-

Flavonoids, a class of secondary metabolites, are widely distributed in plant organs and serve various biological functions[65]. The MYB, basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) and WD40 TF families are known to regulate flavonoid metabolism[65]. The bZIP family of TFs also contributes to this regulatory network. HY5 was the first bZIP TF identified as a regulator of anthocyanin biosynthesis. Experiments by Stracke et al. showed that HY5 is required for light- and ultraviolet (UV)-B-responsive gene regulation and activates the flavonoid biosynthetic gene CHS. Moreover, HY5 cooperates with MYB12 to ensure appropriate regulation of flavonoid biosynthesis. Additionally, in grape, VvibZIPC22 activates the transcription of flavonoid biosynthetic genes, including VviCHS3, VviCHI, VviFLS1, and VviANR, thereby contributing to flavanol production[66]. Soybean GmbZIP131 has been identified as a positive regulator of isoflavonoid synthesis, linking stress adaptation with legume-specific secondary metabolites[67]. In contrast, Tu et al. (2022) reported that knockout of one allele of VvbZIP36 negatively affects anthocyanin biosynthesis, suggesting that it functions as a negative regulator[68].

Lignin forms the structural matrix of secondary cell walls in vascular plants and plays key physiological roles, including maintaining the xylem's hydrodynamic conductance, providing mechanical strength, and facilitating defense against biotic and/or abiotic stressors[69,70]. In addition to its role in ABA-mediated drought tolerance, VlbZIP30 also directly regulates lignin biosynthesis. Tu et al. (2020) demonstrated that VlbZIP30 binds to the promoters of phenylpropanoid pathway genes and activates peroxidase genes involved in lignin polymerization, thereby promoting strengthening of the cell wall under drought stress. This dual regulation of both ABA signaling and lignin metabolism highlights the central role of VlbZIP30 in coordinating physiological and structural responses to dehydration[71]. In poplar (Populus trichocarpa), two bZIP TFs (PtrBPL1 and PtrBPL2) physically interact with Arabidopsis TGA proteins (AtTGA1/3/4/7), which are also members of the bZIP family, to synergistically activate lignin biosynthetic genes and promote lignin deposition[72,73].

In addition, bZIPs can also regulate the biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites. LvbZIP44 enhances anthocyanin accumulation in lily (Lilium lancifolium Thunb) petals under light induction[74]. SlAREB1 in tomato integrates ABA signaling with secondary metabolism, improving both drought resistance and carotenoid biosynthesis[75]. In grapevine, VvHY5 not only activates CHS but also coordinates UV-B-induced stilbene accumulation[76]. In potato (Solanum tuberosum), StHY5 plays a key role in light-mediated regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis, highlighting the broad and conserved functions of bZIPs in secondary metabolism across species[77].

Although an>, VvibZIPC22, VvbZIP36, and VlbZIP30 have been identified as regulators of flavonoid and lignin biosynthesis, their hierarchical relationships remain poorly defined. Both VvHY5 and VvibZIPC22 activate flavonoid genes, yet whether they act redundantly or cooperatively is unclear[68,76]. New players, including PopbZIP2, LvbZIP44, SlAREB1, VvHY5, GmbZIP131, and StHY5, further complicate the network, but the mechanistic interactions and hormone cross-talk (ABA, JA, SA) remain insufficiently explored[67,71,77,78]. These gaps underscore the need for integrative studies that dissect cooperative versus antagonistic functions of bZIPs and their links to stress-induced metabolic remodeling.

Overall, bZIP TFs function as versatile regulators in secondary metabolism, controlling the biosynthesis of flavonoids, lignin, and other phenylpropanoid-derived compounds. Their activities connect developmental cues and environmental stimuli with metabolic outputs, ultimately shaping plants' phenotype and stress adaptability.

bZIP transcription factors play multifaceted roles in both primary and secondary metabolism, linking energy homeostasis with stress adaptation and developmental processes. In primary metabolism, members of the S1-group of bZIPs such as AtbZIP1, AtbZIP53, and bZIP63 act as central regulators of sugar signaling and nutrient reprogramming, coordinating carbon and nitrogen metabolism under fluctuating environmental conditions. In secondary metabolism, bZIPs including HY5, VvibZIPC22, VvbZIP36, and VlbZIP30 orchestrate flavonoid and lignin biosynthesis. Importantly, bZIPs can also regulate the biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites, such as alkaloids, terpenoids, and phenolic compounds, thereby expanding their functional scope beyond the flavonoid and lignin pathways. Despite these advances, the molecular mechanisms underlying their target gene specificity, regulatory hierarchies, and cross-talk with hormonal signaling remain poorly understood. Future research should integrate transcriptomics, metabolomics, and gene editing approaches to dissect the cooperative and antagonistic functions of bZIPs in metabolic regulation, ultimately providing new strategies for improving crops' quality and stress resilience.

-

bZIP TFs play central roles in regulating seed maturation, accumulation of storage reserves, and germination. For example, bZIP53 forms heterodimers with bZIP10 and bZIP25 to activate genes encoding seed storage proteins and proteins that are abundant in late embryogenesis, thereby coordinating maturation processes[79]. In the ABA signaling pathway, ABI5, a Group A bZIP, acts as a key regulator of seed dormancy and germination by controlling ABA-responsive genes' expression and feedback regulation of ABA receptor genes[80]. Moreover, seed-specific bZIPs such as DPBF2 modulate oil biosynthesis and fatty acid composition, linking transcriptional control to seeds' nutritional quality[81].

Despite these advances, current research on seed-related bZIPs is still fragmented. Most studies have focused on individual members like ABI5 or bZIP53, but systematic dissection of the redundancy and specialization within the bZIP network is lacking. Furthermore, although heterodimerization is known to expand regulatory capacity, the precise "dimer code" in seed-related transcriptional regulation remains poorly understood[11]. Bridging these knowledge gaps through cross-species comparative genomics, single-cell seed transcriptomics, and genome editing approaches will be critical for exploiting bZIPs for improving seed traits.

Light signaling and photomorphogenesis

-

Light is not only the energy source for plant photosynthesis but also an essential environmental signal that influences various aspects of plants' growth and development. Upon receiving light signals, plants' photoreceptors initiate a stepwise signal transduction process that activates key downstream TFs to regulate genes involved in development and photomorphogenesis.

HYH and HY5, two bZIP TFs, play central roles in light signaling and photomorphogenesis. HY5 was the first TF identified in the regulation of photomorphogenesis[82]. It binds to G-box and Z-box cis-elements in light-responsive promoters, inducing the expression of over 3,000 genes[83]. In light conditions, HY5 binds to cis-elements of photocontrol genes such as CHS, CAB, PHYA, and RBCS, thereby positively regulating their expression[84−87].

As a TF, HY5 functions by interacting with other proteins. CONSTITUTIVELY PHOTOMORPHOGENIC 1 (COP1)-HY5 molecular modeling represents a central mechanism regulating photomorphogenesis in plants. COP1, a negative regulator of photomorphogenesis, directly interacts with HY5 to mediate its proteasome-dependent degradation in the dark[88]. UV-B light inhibits COP1-mediated HY5 degradation, thereby promoting photomorphogenesis[89]. Additionally, HY5 interacts with and negatively regulates HFR1 and LAF1, which are crucial for Phytochrome A (phyA)-mediated photomorphogenesis[90]. HY5 also targets other light signaling components, including FAR-RED ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL1 (FHY1), FHY1-LIKE (FHL), and the B-BOX protein BBX25[90−92].

Floral development and pollen germination

-

Floral development occurs in three successive stages: Floral induction, floral primordial formation, and floral organ development.

FLOWERING LOCUS D (FD), a bZIP family member, is a central regulator of floral transition at the shoot meristem. FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT), a conserved flowering promoter acting downstream of multiple regulatory pathways[93], is expressed in the cotyledons and leaf vasculature but requires the bZIP TF FD at the shoot apex. Together, FT and FD promote floral transition and development via APETALA1 (AP1). FT may also function as a long-distance flowering signal. ABI5, another bZIP TF involved in ABA-mediated seed germination, also influences floral transition in Arabidopsis. Overexpression of ABI5 delays flowering by upregulating FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC), whereas ectopic FLC expression reverses early flowering in ABI5 mutants.

During the formation of floral primordia, the Arabidopsis TF PERIANTHIA (PAN), part of the TGA family, regulates the development of floral organs' primordia, as evidenced by the abnormal pentamerous arrangement of the outer three floral whorls in the pan mutant[94].

TGA TFs of Subfamily D are also critical for floral organ development. For example, TGA9 and TGA10 have overlapping functions in this process. Arabidopsis plants with mutations in both TGA9 and TGA10 exhibit male sterility, confirming these TFs' essential role in floral development and their necessity in anther dehiscence[95].

In addition, bZIP TFs play a critical role in the development and functional regulation of roots and leaves. Roots, which absorb water and nutrients, anchor the plant and store nutrients, form the foundation for plants' survival and growth. In Arabidopsis, bZIP29 directly binds to and activates cell-cycle-regulatory genes (e.g., CYCB1;2) and inhibitory genes (e.g., SMR4), maintaining root apical meristem homeostasis by balancing cell proliferation and differentiation[96]. In maize, ZmbZIP4 positively regulates abiotic stress responses and modulates root development by influencing auxin signaling and cyclin-related genes[23].

Fruit development and organ senescence

-

Fruit development and organ senescence are complex biological processes that require precise transcriptional regulation. Increasing evidence has demonstrated that bZIPs play a central role in coordinating hormonal, metabolic, and environmental cues to regulate these developmental events. In fleshy fruit crops, bZIPs are directly linked to the control of ripening-associated pigmentation. For instance, in strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa), FaHY5, a light-responsive bZIP protein, acts within the FaCRY1–FaCOP1–FaHY5 regulatory module to activate anthocyanin biosynthesis and transporter genes, thereby promoting pigment accumulation and fruit coloration at the molecular level. Silencing FaHY5 leads to impaired anthocyanin production and delayed ripening, although its overexpression enhances fruit pigmentation[97]. This highlights the critical role of bZIPs in integrating light signals with secondary metabolism to fine-tune fruit quality.

In addition to fruit development, bZIP transcription factors are key regulators of organ senescence, a genetically programmed process that is essential for nutrient remobilization and survival. In Arabidopsis, ABA-activated ABF/AREB bZIPs directly induce the expression of chlorophyll catabolic genes and senescence-associated genes (SAGs), thereby promoting the degradation of chlorophyll and accelerating leaf yellowing[98]. These findings underscore that bZIPs function as transcriptional activators connecting hormonal signals with age-dependent transcriptional programs. Furthermore, recent reviews have emphasized the hub-like role of bZIPs in coordinating ABA, light, and stress signals with developmental outcomes, making them critical players in both fruit maturation and senescence pathways[99]. The molecular mechanisms revealed in strawberry and Arabidopsis exemplify how bZIP TFs act as central regulators, integrating environmental cues and endogenous signals to control developmental plasticity.

bZIPs activate metabolic pathways for pigment biosynthesis during fruit ripening, modulate hormone signaling to regulate maturation, and promote senescence programs by controlling the degradation of chlorophyll and SAG expression. These recent advances highlight their importance as molecular switches in balancing fruit quality traits and organ longevity, providing promising targets for genetic improvement of crops.

Overall, bZIP TFs orchestrate diverse aspects of plants' development, including seed maturation, photomorphogenesis, flowering transition, organ growth, fruit ripening, and senescence, by integrating hormonal, metabolic, and environmental cues into transcriptional programs[79,83,100]. Through context-specific dimerization and interaction with signaling pathways such as ABA, light, and carbon metabolism, bZIPs act as crucial molecular hubs linking developmental processes to stress adaptation[11]. However, most studies have concentrated on a few representative members such as HY5, ABI5, and FD, leaving the broader regulatory dimer code and network redundancy insufficiently understood[93]. Future research should therefore focus on elucidating the spatiotemporal specificity of bZIP dimers, integrating single-cell and spatial omics to map the developmental networks, and clarify the cross-talk among hormone, light, sugar, and ER stress signaling during growth transitions. In addition, dissecting the post-translational modifications and chromatin remodeling complexes that fine-tune bZIP activity will help link developmental plasticity with resilience[85]. Finally, the application of genome editing and synthetic biology offers promising opportunities to engineer bZIP pathways in a precise and organ-specific manner, thereby improving flowering control, fruit quality, and postharvest longevity in crops.

The activity and specificity of bZIP TFs are tightly regulated by post-translational modifications (PTMs) and epigenetic mechanisms. Phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and acetylation dynamically modulate the stability, localization, and DNA-binding activity of bZIP proteins during development and stress adaptation. For instance, SnRK2- and Calcium-Dependent Protein Kinase (CDPK)-mediated phosphorylation enhances the transactivation capacity of AREB/ABF members under drought and ABA treatments, whereas casein kinase II-dependent phosphorylation of HY5 affects its stability and photomorphogenic function[13,85]. Conversely, ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated degradation, such as the COP1-dependent turnover of HY5, represents a crucial feedback mechanism linking light and temperature cues[100].

In parallel, bZIPs' transcriptional networks are modulated by epigenetic modifications that shape chromatins' accessibility at target loci. Histone acetylation and methylation influence recruitment of bZIPs to promoter regions of stress-responsive and metabolic genes. The SNL–HDA19 histone deacetylase complex antagonizes HY5 activity, repressing light-induced gene expression and photomorphogenesis[85]. Furthermore, interactions between bZIPs and chromatin remodelers such as Switch/Sucrose Non-Fermentable (SWI/SNF) complexes integrate hormonal and developmental signals to fine-tune gene expression. These multi-layered regulatory networks illustrate how PTMs and epigenetic modifications cooperate to orchestrate bZIP-mediated transcription in growth, stress responses, and secondary metabolism. Understanding these layers of control will be critical for elucidating the context-specific regulatory hierarchies and for leveraging bZIPs in precision engineering of crops.

The bZIP TF family, as highly conserved regulatory elements in plants, plays a central role in developmental regulation by participating in multiple physiological processes, including the initiation of seed maturation, establishment of the root system's architecture, light signal perception, and photomorphogenesis. Molecular studies have revealed that this family establishes complex signal cross-talk networks by integrating various hormone signaling pathways (e.g., ABA and JA) and secondary metabolic pathways (e.g., lignin biosynthesis in phenylpropanoid metabolism), thereby coordinating plants' adaptive responses to abiotic stresses such as drought and salinity and enhancing stress resistance. Although current molecular breeding strategies based on bZIP TFs have shown promise for developing stress-resistant germplasm, the functional redundancy among family members and subfamily-specific regulatory cascades remain to be fully understood. Future research should integrate multi-omics analyses with CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing to systematically identify the key functional modules involved in improving crop nutrition and extreme environmental adaptation, with attention to the three-dimensional genomic architecture and epigenetic modifications. Therefore, this approach will support the development of multidimensional stress-resistance models, offering theoretical frameworks and technical strategies for breeding smart crops with complex stress-resistant traits.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32202423).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: writing – original draft: Mao Y, Tu M, Zhao R; writing – review and editing: Zhang Y. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no new datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Yingjie Mao, Ruikang Zhao

- Supplementary Table S1 Distribution of bZIP transcription factors across plant species.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Mao Y, Zhao R, Zhang Y, Tu M. 2025. Regulatory function of plant basic region/leucine zipper transcription factors in stress, metabolism, and developmental processes. Fruit Research 5: e046 doi: 10.48130/frures-0025-0039

Regulatory function of plant basic region/leucine zipper transcription factors in stress, metabolism, and developmental processes

- Received: 03 July 2025

- Revised: 28 October 2025

- Accepted: 12 November 2025

- Published online: 24 December 2025

Abstract: The basic region/leucine zipper (bZIP) proteins represent one of the largest transcription factor (TF) families and have been identified in various plant species. The plant bZIPs regulate growth and development processes, are closely linked to plant metabolism, and play key roles in responses to biotic and abiotic stresses. This review specifically summarizes the regulatory functions of plant bZIP TFs in abiotic stresses (drought, salinity, temperature extremes, and heavy metals), biotic stresses (pathogens and herbivorous insects), primary and secondary metabolism, and developmental processes (seed maturation, fruit ripening, organ senescence). We highlight mechanistic models, unresolved controversies, and future research directions, providing a theoretical basis for crop improvement.