-

Many valuable plant secondary metabolites are unique to certain plant species or groups of closely related species involved in complex biosynthetic pathways, and different kinds of catalytic enzymes. Large-scale production of natural plant products is hampered by the long cultivation periods, requirements for specific cultivation conditions, reliance on climatological conditions, seasonally dependent growth, and competition for arable land for food production[1]. In addition, extraction of these secondary metabolites is often quite costly and has a large environmental impact due to the low concentrations of the products[2]. As an example, the production of 1 kg of flavonoids requires the processing of 0.25−33 tons of dry fruits or vegetables[3], but the yearly global need for flavonoid extracts exceeds 3,000 tons (estimated by market size). As a result, microbial production of value-added, plant-derived compounds increasingly attracts commercial interest in the food and pharmaceutical industries. Synthetic biology strategies necessitate heterologous expression of plant-derived genes to reconstruct the biosynthetic pathway within the target microbial host. This demands detailed knowledge of these pathways and several studies have focused on elucidating the biosynthetic pathways.

Along with the development of high-throughput technologies, biologists can comprehensively measure genome constitution, gene expression, and metabolism: Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) technologies have pushed the development of plant genomics, enabling comprehensive investigation of genome composition, structure, functional elements, and evolutionary dynamics. Transcriptomics, which also leverages NGS, examines global gene expression patterns by quantifying RNA abundance per gene. Metabolomics profiles the complete set of metabolites using chromatographic techniques coupled with mass spectrometry, and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. These methods collectively regarded as 'omics' generate vast amounts of data requiring bioinformatic analysis. Along with the development of multi-omics techniques, reverse genetics started to flourish in the discovery of pathways for the biosynthesis of plant natural products in recent years. De novo genome assembly, followed by structural and functional annotation identifies genes and their functions based on homology; biosynthetic gene clusters (BGC) are regularly found by taking advantage of the similarity of structural arrangements of genes in common biosynthetic pathways; co-expression of function elucidated genes from transcriptome studies provides convincing inferences of candidate catalytic genes; metabolome measurement, and second-generation sequencing of plant populations enable metabolome genome-wide association studies (mGWAS) to identify variation in Single Nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) related to secondary metabolism; comparative genomics and analysis of the pan-genome of a taxon are useful in detecting large structure variations for related metabolic phenotypes; comparison of omics datasets also dictate the evolutionary trajectory of plant natural product biosynthesis pathways[4,5].

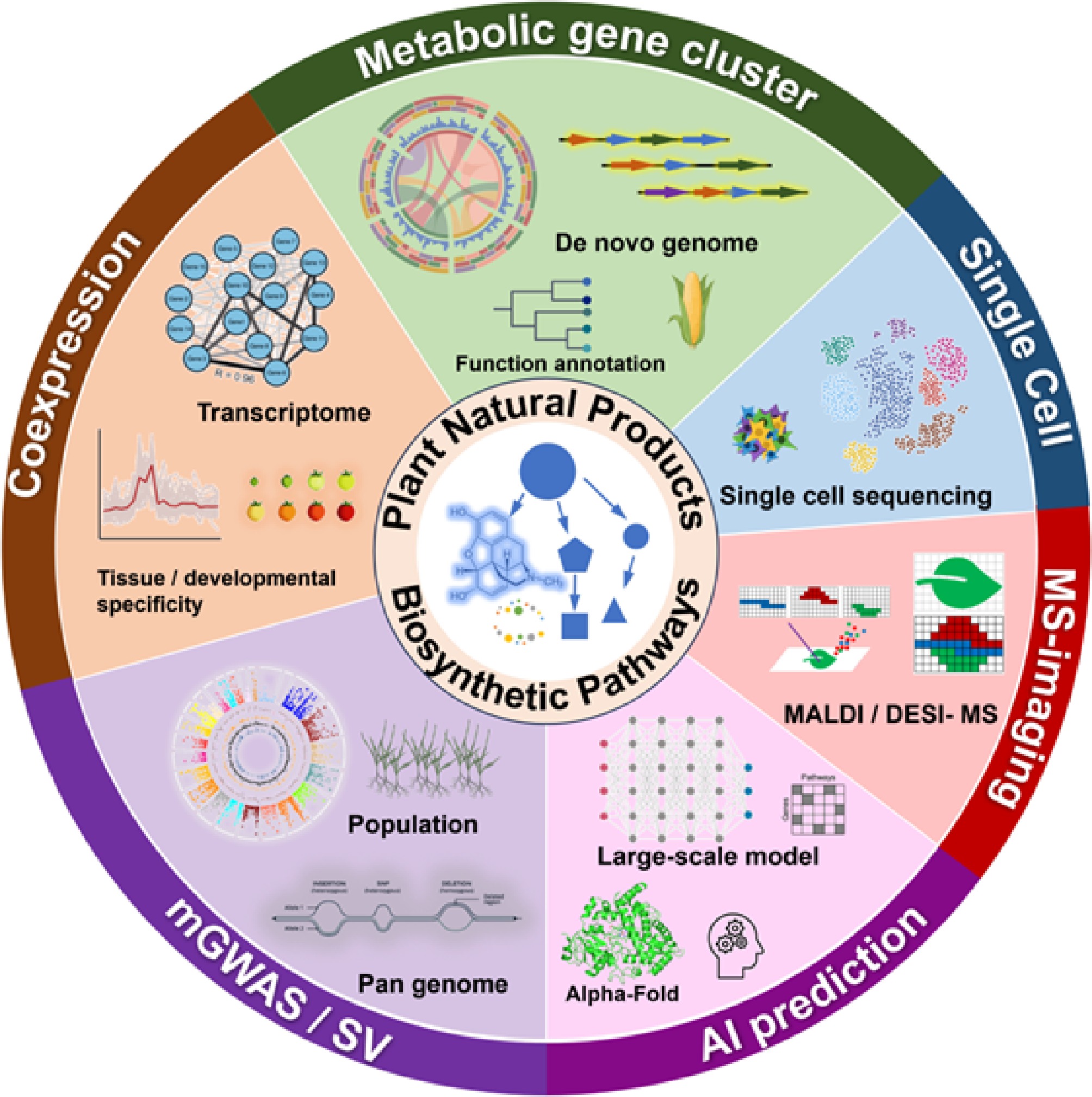

This review highlights recent advancements in plant natural product biosynthesis enabled by multi-omics approaches (Fig. 1) and discusses future perspectives facilitated by emerging technological innovations. These omics strategies, including de novo genome assembly, transcriptome coexpression, mGWAS, and pan-genome, have substantially advanced the identification of catalytic enzymes, characterization of metabolic gene clusters, and elucidation of evolutionary trajectories. We also examined emerging technologies, such as single-cell sequencing, spatial transcriptomics, mass spectrometry imaging, and, notably, machine learning, a transformative computational tool with broad interdisciplinary applications These advanced techniques are expected to push plant natural product research to the next level.

-

Plants are sessile organisms. As they cannot escape from environmental threats and biotic stressors they developed defense strategies by generating various natural products to combat plant diseases, herbivory insects, abiotic stresses, and in addition, to attract beneficial organisms like pollinators[4,6]. These products have also proven valuable for humans and plant natural products can be used in a range of applications. For instance, pyrethrins from pyrethrum and benzoxazinoids from maize show effects of repelling and killing insects[7,8], hence they are considered natural pesticides. Other plant natural products, such as polyamines and phenolics participate in plant growth and development such as flowering and fruit set[9,10]. Furthermore, a broad range of natural products including terpenoids and fatty acid derivatives from tomato and cucumber fruits are appreciated as food additives due to their contribution to distinctive and complex flavor profiles[11−13]. In addition, some of these metabolites possess pharmacological activities like anti-inflammatory and anti-pathogenic activities and are therefore used as plant-derived drugs or as traditional medicines for curing human diseases[4−6,14]. Examples are artemisia for malaria treatment[15,16], paclitaxel for cancer chemotherapy[17], and tropane alkaloids as anticholinergics[18].

Plant natural products are regulated by various factors. The regulation of gene expression in biosynthetic pathways is usually accomplished by transcription factors (TFs) directing downstream gene expression[19,20]. Under drought stress, baicalin and wogonoside levels in Scutellaria baicalensis initially showed a slight decrease followed by a significant increase at a later stage. Transcriptomic analysis revealed that TF SbWRKY34 negatively regulated this drought response[21]. In rice, a receptor-like kinase (OsRLCK160) was shown to interact with a bZIP family TF (OsbZIP48) and promoted flavonoid accumulation to enhance UV-B tolerance[22]. Phytochrome-interacting factors (PIFs), members of the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor family, directly associate with phytochromes, the red/far-red light photoreceptors[23]. In tomato melatonin biosynthesis, SlPIF4 acts as a negative regulator by suppressing the expression of the key biosynthetic gene SlCOMT2. However, under red light conditions, SlphyB2 (phytochrome B2) promotes the degradation of SlPIF4, thereby relieving the repression and enhancing melatonin accumulation[24]. Integrating transcriptome and spatio-temporal metabolome data resulted in a metabolic network of tomato, which revealed the regulation of TFs, such as SlMYB75 and SlERF.G3-like in flavonoids biosynthesis, and SlGAME9 and SlbHLH14 in steroidal glycoalkaloids (SGA)[25]. In cucumber, GWAS revealed a BGC of nine genes involved in cucurbitacins biosynthesis and two TFs regulating this BGC in leaves and fruits, named Bl (Bitter leaf) and Bt (Bitter fruit)[26]. Regulations may be achieved by epigenetic modification as well[20]. For instance, the ubiquitin-like protein SILENCING DEFECTIVE 2 (SDE2) interacted with HETEROCHROMATIN PROTEIN 1 (LHP1) and together increased the H3K27me3 level to repress the anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana[27]. A study on telomere-to-telomere (T2T) genome assemblies of two Chili pepper species revealed the placenta-specific biosynthesis of capsaicinoid was coordinately regulated by the low methylation level at the open chromatin regions (OCRs) with placenta specificity[28].

Plant-specialized metabolites are generally synthesized from common primary metabolites[29]. Depending on the type of precursors and sharing structures, they are divided into several groups, commonly known as terpenoids, alkaloids, phenylpropanoids, polyketides, etc.[5]. Synthesis of these plant natural products usually requires complex pathways formed by enzymes from multiple gene families. Several of the enzyme families involved have been thoroughly researched. Notably, enzymes like cytochrome P450s (CYP450s) and uridine diphosphate (UDP)-glycosyltransferases (UGTs) are part of large families comprising hundreds of members[20,21,30,31]. The sequence diversity within biosynthetic pathways poses a challenge for comprehensive candidate gene identification, as it is impractical to functionally assess all possibilities simultaneously. However, the use of reverse genetics enables the selection of the most probable candidates for functional tests to relieve the experimental work intensity.

-

Plants have complex genomes with large sizes and bulk of tandem repeats, which make them difficult to assemble. However, the development of the 3rd generation ultra-long sequencing techniques allows plant scientists to obtain plant de novo genomes at the chromosome-scale, including gap-free and telomere-to-telomere (T2T) level resolutions[32]. This development also facilitates the discovery of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) which are groups of genes involved in a specific biosynthetic pathway and closely located on a chromosome[33−38]. Although genes from BGCs of eukaryotic plants cannot be controlled by unique promoters, they often participate in the same metabolic pathway and experience shared regulation[39], such as the seed-specific BGC for aescin and aesculin biosynthesis in Aesculus chinensis[40], and the pathogen-defensive BGCs in bread wheat[41].

BGCs might arise as a result of gene duplication, genome reorganization, or whole genome duplication, and might acquire new functions for natural product biosynthesis later during evolution[40,42−44]. BGCs across different plant species can evolve analogous functions through mechanisms of convergent or parallel evolution[45,46]. The first biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC) identified in plants was discovered in maize in 1997, comprising a tryptophan synthase gene (Bx1) and four cytochrome P450 genes (Bx2–Bx5) located on chromosome 4. This BGC is responsible for the biosynthesis of benzoxazinoid, a defensive metabolite against pathogens[47]. Subsequently, two UDP-glycosyltransferases (UGT) Bx8 and Bx9 were identified as additional components of this cluster[48]. Since then, an increasing number of BGCs have been identified in plants, including a cluster comprising 10 synthetic genes for noscapine biosynthesis in Papaver somniferum reported in 2012[49]. However, it is important to note that not all genes involved in natural product biosynthesis are physically clustered. For example, genes responsible for the biosynthesis of berberine in Coptis chinensis and saponarioside in soapwort (Saponaria officinalis) are dispersed throughout the genome[50,51].

As finding BGCs is often an important part of genome annotation and analysis, bioinformatic tools have been developed specifically for BGC identification. PlantiSMASH is a widely used online tool that efficiently identifies genomic loci encoding multiple (sub)families of specialized metabolic enzymes. To perform this task, plantiSMASH integrates a curated library of enzyme families associated with plant biosynthetic pathways, in conjunction with CD-HIT-based clustering of predicted protein sequences[52].

The identification of BGCs in newly assembled plant genomes informed our understanding of these specialized metabolic pathways, a progress largely driven by advances in genomics. The assembled genome of Taxus chinensis var. mairei helped identify a BGC for paclitaxel, an important anti-cancer compound. Within this BGC, members of the CYP725A family (T5αH, T13αH, T2αH, T7βH, T9αH1, TOT1) catalyze specific hydroxylation reactions, which are critical steps in forming this complex natural product[53,54]. A mirror-structured BGC for p-menthane monoterpenoids biosynthesis was identified in the assembled genome of Schizonepeta tenuifolia[55]. A gene cluster for ginkgolide biosynthesis containing five CYP450s was discovered by mining the published Gingko biloba genome[56]. Hyperforin in St John's wort has been shown to involve two distinct BGCs[57].

In field crops and horticultural plants, typical BGCs associated with plant defense have been identified. Examples include BGCs responsible for phytoalexin production in wheat, the avenacin biosynthetic cluster in oat, and the BGC for the biosynthesis of falcarindiol a highly modified fatty acid, in tomato[14,41,58]. Additionally, a fatty acid metabolic gene cluster conserved across the Poaceae family has been shown to control male fertility rice thereby influencing rice yield[39]. The genomes of Isodon rubescens, and Tripterygium wilfordii contained tandem-duplicated CYP706V and CYP82D clusters for oxidative modification of biosynthesis oridonin and triptolide, respectively, both of which are diterpenoid with anti-inflammatory and anticancer applications primarily isolated from plants and used in traditional Chinese medicine[59,60]. It is worth noting that members of the CYP706 family have been found in various other plant species and are associated with the biosynthesis of compounds that contribute to plant defense and resistance. Examples are CYP706A3 involved in terpenoid biosynthesis cluster responsible for flower defense and herbicide resistance in A. thaliana, CYP706B1 from cotton, and CYP706M1 from Alaska cedar both of which were involved in the biosynthesis of anti-herbivory sesquiterpenes. Furthermore, CYP706C55 from Eucalyptus cladocalyx was found to be involved in the biosynthesis of cyanogenic glucosides, a class of chemicals defending plants against herbivores[61−65]. These BGC discoveries indicated the importance of genome architecture in informing our understanding of plant natural product biosynthesis.

-

In plant species with numerous germplasm resources, pan-genome analysis integrates genomic information across different germplasms and populations. This population-based genomic approach enables efficient identification of key genetic loci and facilitates the evolutionary tracing of natural product biosynthesis. Third-generation sequencing further enables the precise identification of genomic locations with large structural variations associated with metabolic synthesis and its regulation[66]. Since the accumulation of a specific secondary metabolite can be considered a measurable plant phenotype, population genetics approaches traditionally used in morphological and physiological trait analysis can likewise be applied to investigate natural product biosynthesis. Metabolome genome-wide association study (mGWAS) integrates metabolic traits or metabolome data to the genome to identify SNPs in candidate loci via large-scale correlation[67,68].

Analysis of genomes could reveal the evolution of typical genes and gene families involved in natural product biosynthesis as well as the evolution of the whole pathways. A typical example is found in tomatoes: Integration of pan-genome data with mGWAS revealed a loss of flavor chemicals in commercial tomato varieties and pointed out a negative correlation between fruit size and sugar content[11,12,69,70]. By analyzing 980 metabolites from 442 lines, mGWAS identified 3,526 SNPs suggesting that fruit weight might indirectly change metabolite accumulation by gene linkage[11]. Pan-genomes of 100 tomato genomes uncovered 238,490 structural variants, further confirming gene loss in domesticated varieties, and showcasing the impact of genome structure variations on phenotypic traits[69,70]. Other examples include a genomic analysis of 204 selected domesticated and bred watermelons, which led to the identification of 29 candidate genes associated with 20 metabolites. The findings suggest that flavor was enhanced through a decrease in flavonoids and cucurbitacins during the domestication process[71]. Carotenoids are nutritional substances that have become significant selection criteria in carrots, resequencing of 630 carrot accessions revealed selection on carotenoid-associated loci[72]. Resequencing analysis of 390 peanut accessions revealed that genes associated with enhanced oil content have undergone positive selection during the breeding process[73].

GWAS has been introduced to study rice agronomic traits, including the biosynthesis and diversity of rice grain oil[74]. Pan-genome analysis of citrus species uncovered that metabolic gene families involved in flavonoid biosynthesis expanded during evolution, and identified a key gene involved in citric acid biosynthesis[75]. mGWAS identified a gene cluster in the pomelo genome associated with the content of melitidin, a potential anti-cholesterol flavonoid, and successfully uncovered the biosynthetic pathway of melitidin biosynthesis[76]. Population genetics analysis identified a gene cluster in citrus associated with polymethoxyflavone (PMF) accumulation, which originated through tandem duplication events followed by neofunctionalization[77]. From 29 assembled T2T reference genomes and the resequencing data of 466 grapevine cultivars, a variation map with 9,105,787 short variations and 236,449 structural variations (SVs) was obtained. 32 related candidate loci were enriched based on eight metabolic phenotypes providing scientific insight into wine flavor development[78].

Population genomics has also been used for natural products other than edible substances. Genome assembly and resequencing of rubber tree genome accessions proved artificial selection on higher latex production and identified domesticated genes[79]. A multi-omics study revealed that jasmonic acid signaling, triggered by leafhopper infestation, regulates pest resistance in Nicotiana attenuata. The analysis further identified a caffeoylputrescine–green leaf volatile conjugate as the key metabolite conferring resistance to leafhoppers[80]. It is anticipated that the exponential increase in plant genomic data will significantly deepen our understanding of plant BGCs.

-

Plant natural products usually accumulate in specific tissues. They can also be induced under certain conditions[81]. Genes from the same biosynthetic pathway are often co-regulated, thus reducing energy expenditure and limiting the accumulation of toxic products. Regulation of expression of genes in biosynthetic pathways is essential for optimizing metabolic processes in response to environmental demands. Genes in these pathways are often regulated at the transcription level. Therefore associations between metabolite accumulation and changes in gene expression have been found in selected organs or tissues, or at certain developmental stages, or only after stimulation (e.g. herbivore bait or microbe infection)[82−84]. Whole-cell RNA extraction followed by sequencing (RNA-seq) allows measuring expression levels of all genes in the genome in different plant tissues under different treatments. These data can be used for gene identification. Genes of known function in the pathway can be used as a 'bait' for co-expression analysis for downstream genes, and specific accumulation patterns of metabolites can be used for correlation analysis and gene selection[85,86]. Commonly used methods include Pearson's correlation and network approaches. For instance, weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) identified co-expressed genes jointly participating in the biosynthetic pathway[85]. Methods to generate and analyze transcriptomics data keep being updated and optimized, still biosynthetic gene identification strategies still rely on co-expression and phenotype association analysis[87] as the following examples related to medicinal plants illustrate.

Many key genes in natural product biosynthetic pathways have been identified by co-expression analysis combined with genomic analysis. Analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEG) analysis is frequently used when RNA-seq data is available. For tissue-specific plant natural products, DEG analysis is effective in discovering candidate genes as it can identify genes with high expression levels in the accumulating tissue. This analysis could be expanded to investigate differences between plant species. The bioactive components ginsenosides (triterpene saponins) from traditional Chinese herbal medicine Panax notoginseng mainly accumulate in the root and rhizome, and five UGTs involved in the ginsenoside biosynthetic pathway were identified by tissue-specific transcriptomic analysis[88]. Similarly, the identification of the genes associated to the biosynthesis of the anti-obesity agent celastrol partly depended on the differential expression of CYP450s in different tissues of Tripterygium wilfordii[89]. Differences in the expression of CYP450 in plant tissue was also key to identify genes related to the biosynthesis of painkiller mitragynine in Mitragyna speciosa[90]. Similarly, differential expression of α-carbonic anhydrases (CAHs) contributed to the discovery of their novel functional roles in the biosynthesis of Lycopodium alkaloids[91]. The identification of strychnine biosynthetic genes was achieved by considering both tissue-specific gene expression and differences in the gene expression levels between plant species producing strychnine or not[92].

Identification of biosynthetic genes usually comprehensively considers the correlation between gene and 'bait' gene expression, and the correlation between gene expression and natural product accumulation. Three key CYP450 genes for baccatin III, an intermediate in paclitaxel biosynthesis, were revealed by analysing co-expression patterns and associations between pathway intermediates and gene expression[54,93,94]. Biosynthetic genes for the anti-cancer natural product camptothecin were identified by analyzing published transcriptomics data using as a reference a newly assembled genome All camptothecin biosynthesis-related genes were located in the same module of the gene co-expression network reconstructed using WGCNA[95]. In our previous study, we identified two dehydrogenases, two CYP450s, and one Nudix phosphatase required in the biosynthesis of pyrethrins, the natural pesticide derived from the Pyrethrum plant. These genes were identified by analyzing transcriptomics data obtained at five developmental stages of the flower as well as vegetative tissues leaf, stem, and root; and the key strategy to identify these candidates was investigating their co-expression with the gene TcGLIP[96−99]. Similarly, another investigation led to the discovery of 22 enzymes for limonoid biosynthesis[100], indicating the effectiveness of co-expression analysis based on transcriptomics.

Research in biosynthetic pathways often combines metabolome and gene expression data. A Lycopodium alkaloid biosynthetic regulon was detected by paired transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses[101]. The O-methyltransferase (OMT) and CYP450s for colchicine alkaloid biosynthesis, and the CYP450s for triptolide biosynthesis were also discovered by combining these data types[102,103]. Identification of BAHD acyltransferases for 3β-tigloyloxytropane, an important intermediate in calystegine biosynthesis, employed tissue-specific DEG analysis, metabolite and gene expression association analysis, phylogenetic and subcellular localization[104]. QS saponin from Quillaja saponaria relied on genome mining to find out the required biosynthetic enzymes but also implemented RNA-seq and co-expression analysis for assistance[105]. Similar approaches were later used for the elucidation of saponariosides B biosynthesis in Saponaria officinalis by the same research group[50]. Although transcriptomic analysis sometimes only plays a small part in the evolutionary study[106−108], it strongly supports the elucidation of natural product biosynthetic pathways[24,109−111].

-

Conventional omics approaches are limited, therefore they are often combined with other approaches or with upgrades in technology. Identification of metabolic signals usually relies on the abundance of the metabolites, the availability of standards, and on databases for metabolite identification. Plant metabolites are highly diverse, but often their abundance is very low. Mass spectrum techniques facilitate obtaining metabolic information from plant tissues or at developmental stages. Mass imaging visualizes the distribution of metabolites on plant tissue to direct the best strategy choice for synthetic pathway elucidation[112,113]. For example, in situ MS imaging of the stem of Isodon rubescens showed that ordonin, an ent-kaurene-type diterpenoid, was synthesized in apices, but gradually diluted in young leaves, helping pathway elucidation in subsequent research[59]. In another example, MALDI-MSI imaging of the cross-section of horse chestnut pericarp showed the specific accumulation of Escin (barrigenol-type triterpenoid saponins) in cotyledon[40].

Despite the tissue-specific accumulation, biosynthesis of some natural products is highly specific to a certain small range of cells such as trichomes or root hairs. Conventional tissue specific RNA-seq may normalize and weaken the expression signals of target genes. One solution is subdividing the samples with more criteria. Research on oridonin biosynthesis introduced growth as a parameter: beyond normal tissue samples like roots, stems, flowers, buds, and leaves, researchers left half of the leaves opposite to the sampled leaves and took samples of them 14 d later[59]. The results suggested shoot apex as the actual location for oridonin biosynthesis. Amaryllidaceae alkaloids (AmAs) accumulate in most parts of the Amaryllidoideae plant. To find out the particular part producing AmAs, the long leaves of daffodils were cut into short sections for sampling[114].

Single-cell sequencing is a novel and effective tool to recognize gene expression and find their coexistence among cell types[115−117]. Research on cotton applying this technique confirmed the glandular trichome-specific expression of genes related to gossypol-type terpenoids and volatile terpenoid biosynthesis and identified two novel transcription factors for terpenoid biosynthesis in secretory glandular cells[118]. A 'hyper' cell type was identified in St. John's wort by single-cell RNA sequencing, where hyperforin biosynthesis de novo takes place, and four prenyltransferases were identified for the complete pathway by gene coexpression among single cells[119].

The above two solutions, sample selection, and single-cell sequencing, may be combined. Recent work on paclitaxel biosynthesis developed a combinatorial method named multiplexed perturbation x single nuclei (mpXsn) to combine both approaches. In mpXsn researchers prepared a series of samples treated with different conditions for increasing paclitaxel biosynthesis, and pooled all samples for single-cell RNA sequencing[120]. This innovative method discovered eight new genes, proving a promising outlook of both omics strategies and research on natural product biosynthesis.

Combination of various approaches complements the limitation of single methods. Multi-omics for tomato revealed new metabolic genes and pathways by combining metabolome with population genome and transcriptome for mGWAS, expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL), and correlation relationship analysis[11]. This research first collected 610 tomato accessions and generated genomic, metabolomic and transcriptomic datasets; the multi-omic datasets provides, general information on SNPs, metabolite composition and DEGs; the correlation in these datasets was investigated by mGWAS and eQTL, and a multi-omic network was established using the results; focusing on the domesticated traits of tomato, the researchers finally discovered candidate genes involved in tomato quality domestication. Combinations of multiple methods have also advanced research stagnated for a long time. As an example, research on the biosynthesis of the natural hallucinogen mescaline had been stuck for decades, but a complex method combining genomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics, and molecular modeling finally elucidated the biosynthetic pathway in peyote[121]. In this work, researchers first analyzed the composition of peyote metabolites and the specific part of mescalin accumulation by LC-MS/MS and MALDI-MSI to infer the possible intermediates and pathway; then a genome was assembled and annotated based on pair-end transcriptomes; depending on the predicted pathway, enzymes belonging to CYP450, methyltransferase (MT), L-tyrosine/L-DOPA decarboxylase (TyDC) and polyphenol oxidase (PPO) families were selected as candidates; after function characterization, one TyDC, one CYP450, and two MTs were identified, and the pathway was reconstituted in yeast and tobacco leaves. The above cases indicate the importance and effectiveness of combinatorial multi-omic methods.

-

Recent advances have driven the application of machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI) approaches in almost every scientific area. In agriculture, the combination of machine learning and various cameras and sensors has led to a new discipline called plant phenomics[122]. Advanced cameras such as thermal infrared camera and 3D time-of-flight cameras, and diverse sensors including chlorophyll fluorescence sensors, laser distance sensors, and RGB sensors have been used to collect crop phenotypic data including plant height, leaf area index, leaf color, tiller density, grain yield, moisture content, and pathogen infection[122]. Utilization of machine learning algorithms in image processing has enabled analysis of such large data. For example, deep learning techniques such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) allowed quick detection of rice disease in the early stages from pictures; Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Gaussian Processes Classifier (GPC) were used to detect moisture deficit by analyzing thermal images of canopies; finally, analysis of light detection and ranging (LiDAR) technology could predict canopy geometry and yield of apple tree[122−125]. These applications required large amounts of data to build models of concerned features.

Since omics strategies have been widely applied in biological research, gene prediction, and identification based on machine learning are introduced into natural product biosynthetic research. Optimized statistics and machine learning have been used to analyze RNA-seq data and predict gene function[87,126]. The integration of large-scale omics datasets, including genomic, transcriptomic, and metabolomic information, has significantly advanced our understanding of plant-specialized metabolism. These datasets provide detailed insights into gene sequences, structural features, genomic loci, BGCs, phylogenetic relationships, and gene regulatory networks. Importantly, computational modeling and machine learning are emerging as powerful tools to synthesize these complex datasets, enabling data-driven predictions and hypothesis generation. As multi-omics resources continue to expand, their synergistic application holds great promise for elucidating biosynthetic pathways and guiding metabolic engineering efforts in plants[127]. For instance, a machine learning–based genome scan was analyzed to predict introgression regions for grape populations[128]. In crop breeding, machine learning has been used to build genomic prediction model for parental selection. These models offered a more comprehensive and deeper analysis of the complex interactions among vast datasets, and their prediction could be adjusted according to the target of breeding by assigning weights to different traits[122,129].

AI also holds significant potential for identifying genes involved in biosynthetic pathways. The introduction of the AlphaFold model marked a breakthrough in structural biology by enabling highly accurate prediction of protein structures. Subsequent models, such as RoseTTAFoldNA and AlphaFold 3, have further expanded these capabilities to include the prediction of protein–ligand interactions, encompassing metal ions, nucleic acids, and post-translationally modified residues[130−132]. In combination with molecular docking that predicts interaction patterns between enzyme and substrate molecules, these AI-powered models help in the functional verification of enzymes and contributed to downstream research such as protein design and virtual screening. A recent example was the identification of a UGT involved in salidroside biosynthesis by predicting protein structure with RoseTTAFold and virtual screening with AutoDock Vina, a tool for molecular docking[133]. Large language models also help develop more advanced BGC detection algorithms, such as DeepBGC[134], and self-supervised training BiGCARP[135]. These algorithms have achieved promising results for BGCs in microbial genomes by leveraging large-scale pre-trained language models to embed Pfam domains and training with masked language model objectives, and therefore effectively capturing higher-order dependencies within sequences.

The application of AI methods has also significantly enhanced the efficiency and accuracy of data analysis in response to the rapid expansion of multi-omics technologies. For instance, the multi-omics analysis platform Compounds And Transcripts Bridge (CAT Bridge) integrates various statistical approaches alongside an AI agent to improve the interpretation of transcriptome–metabolome associations. This platform has demonstrated strong performance, particularly in the analysis of longitudinal omics datasets[136]. For more complex datasets like single-cell transcriptome data, generative AI models such as scGPT showed good performance in cell type annotation, perturbation prediction, multi-batch data integration, and gene network inference[137]. The modelling capacity was also used for optimizing natural product metabolism for higher yield. The integration of design of experiment (DoE) strategies with machine learning approaches has been successfully applied to optimize metabolic pathways, exemplified by the enhanced production of p-coumaric acid in engineered yeast strains[138−140]. The deep learning–based model BioNavi-NP has demonstrated notable potential in predicting plausible biosynthetic pathways directly from the chemical structures of natural products. Through extensive training on known biosynthetic reactions, BioNavi-NP can infer enzyme-catalyzed transformations and pathway logic, providing valuable insights for pathway elucidation and metabolic engineering. Its application not only accelerates the discovery of unknown biosynthetic routes but also supports the rational design of synthetic biology strategies[141].

-

Finding candidate genes and gene clusters represents only the initial step in elucidating biosynthetic pathways. The next essential task is to validate the functions of the candidate genes. There are various methods developed to test gene function, and could be primarily divided into in vitro and in vivo. In vitro experiments give direct results by eliminating the interference of the internal environment of plants, while in vivo experiments can show the real situation about how candidate gene function in plants.

The most straightforward method for in vitro validation involves incubating purified enzymes with their respective substrates in a buffered reaction system. Target enzymes are usually obtained through protein expression in bacteria cells followed by tag-based purification. E. coli is the most common chassis for in vitro protein expression. In mescaline biosynthesis, for example, TyDC candidates and MT candidates were heterologously expressed in E. coli and the lysate was used for in vitro enzyme assays[121]. The 3β-tigloyloxytropane synthase (TS) from Atropa belladonna was expressed in E. coli and purified via MBP-tag[104]. Similarly, ApCPS2 and ApGGPPS from Andrographis paniculata were characterized by an in vitro assay using E. coli expressed and purified protein[142,143]. However, there are enzymes like membrane proteins that usually require eukaryotic organelles for proper translation, folding, modification, and functioning, making them difficult to express in prokaryotes[144]. Membrane proteins like CYP450s were usually insoluble when directly expressed in E. coli and therefore required extra modification[144]. Hence for these enzymes, eukaryotic chassis were introduced. Yeast, especially Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is commonly used in enzyme expression as it provides a sufficient environment including endoplasmic reticulum (ER) for membrane enzyme expression[144]. For secreted protein, inducible expression, and purification protocols are generally comparable to those used in prokaryotics. For membrane enzymes, a better alternative might be microsomes as it maintains the conformation of enzymes. Several studies, such as flavonoid diversification in Scutellaria, aporphine alkaloids biosynthesis, colchicine alkaloid, and huperzine A biosynthesis, have employed microsome for in vitro enzyme assay to characterize functions of CYP450s[91,102,145,146].

Exogenous expression is another method to validate gene function. Substrates could be directly supplied to the engineered microbial strains or produced by the chassis. The CYP450s involved in aescin and aesculin biosynthesis were characterized in engineered yeast[40], so as the CYP450s catalyzing oxidative rearrangement for xanthanolide[147]. In the study of tripterifordin and neotripterifordin biosynthesis, yeast strains were engineered to characterize CYP450 monooxygenase C20ox[148]. The model plant, tobacco Nicotiana benthamiana is also a popular chassis for enzyme function validation, especially in plant natural product biosynthesis, as it provides a more suitable environment for plant gene expression. Characterization of biosynthetic enzymes via transient expression in N. benthamiana included CYP725A subfamily enzymes for baccatin III[54,94], a gene set involved in paclitaxel biosynthesis[93], UGTs for saponins in soapbark tree and soapwort[50,105], complete pathway genes for pyrethric acid[97], a CYP450 gene cluster involved in ginkgolide biosynthesis[56]. Other model plants, such as A. thaliana[149], Oryza sativa (rice)[150], Solanum lycopersicum (tomato), and Cucumis sativus (cucumber)[151] were also used as chassis in natural product biosynthesis studies. In addition, some studies employed insect cells for exogenous expression in gene function validation[54]. These methods were often combined in the same study to eliminate the probable side effects of endogenous metabolism of chassis[54,56,91,94,102,121,148].

Compared to exogenous expression, in vivo methods typically validate gene function in the original plants. Gene knock-outs and overexpression are widely used strategies to verify gene functions. Popular approaches include transgenic technology and genome editing that create plant lines with stable inheritance.

However, stable genetic transformation systems are underdeveloped or unavailable for many plant species, particularly medicinal plants. Consequently, transient gene expression is an effective alternative method for functional gene analysis and pathway reconstruction. Hairy roots are abnormal growth induced by Agrobacterium rhizogenes infection but are similar to normal roots in anatomy and metabolism[152]. A. rhizogenes can harbor target genes inserted in its T-DNA region that can then be integrated into the plant genome. This allows gene function validation with the hairy root system[152,153]. The hairy root transformation system has been established in many medicinal plants to enhance natural product biosynthesis and verify gene function, the promotion of saikosaponins in Bupleurum chinense with overexpression of BcERF3 in hairy root as an example[154,155]. Crops also employed hairy root systems for rapid and efficient transformation. A reported hairy root system for soybean required only 16 d for the whole workflow of transformation, and allowed genome editing for gene function characterization[153].

Virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) is another in vivo validation method utilizing plant defense mechanisms against virus infection. This technique suppresses the expression of the target gene in plants by infecting plants with a virus conveying fragment of the target gene and inducing post-transcriptional gene silencing, and the system has been applied in tobacco and tomato[156]. As a transient transformation method, VIGS avoids the obstacle in establishing stable transformation system, showing a significant advantage in research on medicinal plants. VIGS at the cotyledon stage of Catharanthus roseus showed successful silencing of several transcription factors regulating terpenoid indole alkaloid (TIA) biosynthesis and resulted in a decrease of TIA intermediates[157]. Another study on C. roseus used VIGS to inhibit CrZIP transcription in function characterization[158]. Suppression of ApCPS2 via VIGS drastically decreased the content of andrographolide and weakened the defense of A. paniculata against herbivores[159]. In Ginkgo biloba and Lycoris chinensis, VIGS application was also reported[160,161].

-

Whatever strategies are used in plant natural product biosynthesis research, the final goal is the industrial production of natural products. Compared to plants, microbes showed multiple advantages for industrial production, such as rapid growth, a smaller genome, plenty of engineering tools, and a mature fermentation industry. A few natural products have been produced by engineered microbial strains and the yield achieved the potential for industrial production. The plant-derived antimalarial drug, artemisinin, was produced by hemi-biosynthesis[162]. An engineered yeast (S. cerevisiae) strain produced the precursor artemisinic acid at an optimized level of 25 g/L, and artemisinic acid was chemically catalyzed to artemisinin[15,162]. Similarly, vindoline and catharanthine were produced by engineered yeast (S. cerevisiae) and the anti-cancer phytochemical vinblastine was synthesized by in vitro chemical coupling[163]. Another study using yeast Pichia pastoris to produce catharanthine reached a titre 2.57 mg/L, indicating that P. pastoris was a potential alternative to microbial chassis[164]. Yarrowia lipolytica is another yeast species. Yields of engineered Yarrowia lipolytica strains for gastrodin production achieved over 13 g/L[165,166], and resveratrol production reached 22.5 g/L[167]. These outcomes suggested the promising potential for producing plant natural products by microbes.

Along with the rapid development of omics techniques, a vast amount of research applied de novo genome assembly, transcriptome co-expression, and population genomics (mGWAS and pan-genome) to investigate the biosynthesis of natural products. New strategies including single-cell RNA sequencing, mass imaging, and machine learning provide a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of natural product biosynthesis, whether in plants or microbes, and have started to play important roles. These novel techniques effectively complement classic techniques and are expected to further support the discovery of unknown biosynthetic pathways, such as the whole pathway of paclitaxel biosynthesis which has puzzled scientists for a long time, or uncover more biosynthetic pathways of lesser-studied plant natural products. For natural products that have been successfully synthesized de novo in microbial chassis but still suffer from limited yields, such as tropane alkaloids[168] and vaccine adjuvant QS-21[169], the technological innovation is expected to accelerate optimization. Ultimately, the rapid development of multi-omic strategies continues to deepen our understanding of plant natural product biosynthesis and paves the way for the efficient industrial production of plant-derived therapeutics.

This work is supported by Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (GJHZ20240218114715030), the National Nature Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32170264), and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant Nos 2020YFA0907900 and 2022YFD1700200).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Li W; draft manuscript preparation: Wan S, Li W, Schaap PJ, Suarez-Diez M. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wan S, Schaap PJ, Suarez-Diez M, Li W. 2025. Omics strategies for plant natural product biosynthesis. Genomics Communications 2: e011 doi: 10.48130/gcomm-0025-0010

Omics strategies for plant natural product biosynthesis

- Received: 15 December 2024

- Revised: 16 April 2025

- Accepted: 29 April 2025

- Published online: 10 June 2025

Abstract: Plant natural products play a crucial role in ecological balance, human health, industrial applications, and biodiversity conservation, making them invaluable across various fields. Elucidation of their biosynthetic pathways is important for further synthetic biology applications. Through gene cluster, co-expression, and population association assays, researchers leverage extensive genomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics data produced by multi-omic technologies to uncover metabolic genes involved in biosynthetic pathways. New techniques such as single-cell sequencing, MS imaging, and machine learning have shown their potential. Here we reviewed multiple omics studies of natural product biosynthesis and discussed the promise and potential of developing techniques for this task.

-

Key words:

- Plant natural products /

- Multi-omics /

- Biosynthetic pathway /

- Catalytic enzyme genes