-

Dao-di herbs are medicinal materials recognized for their superior quality and efficacy, achieved through long-term clinical application in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). These herbs are cultivated in specific geographical regions, where their quality surpasses that of counterparts produced elsewhere, ensuring stability and widespread recognition. As a cornerstone of TCM resources, Dao-di herbs represent a vital strategic asset in China. Translating the concept of geo-herbalism into modern scientific terms is essential for the sustainable development of Dao-di herbs and for preserving, advancing, and utilizing the invaluable legacy of TCM. The theory of Dao-di herbs encapsulates the TCM perspective on the interplay between medicine and nature. The formation of Dao-di herbs is attributed to genetic variations and environmental influences, reflecting the long-term adaptation of specific germplasm to distinct habitats. This adaptation manifests across phenotypic, physiological, biochemical, and genetic dimensions, resulting in complex and systemic adaptive traits[1].

Atractylodes lancea (Thunb.) DC., a widely distributed Dao-di herb, has been extensively validated through clinical practice for its superior quality and therapeutic efficacy[2]. As one of the typical Dao-di herbs, A. lancea not only has a clear production area but also has specific and unique chemical characteristics[3]. Moreover, it is a polymorphic species, and this interaction not only enriches the biodiversity of its native species but also underpins the ecological and biological basis for the formation of its high-quality Dao-di characteristics. Over a prolonged period of adaptive microevolution, Mao-A. lancea from Maoshan, Jiangsu Province, has developed unique genotypes and chemical compositions in the face of environmental adversity, which further strengthens its geo-herbalism[4,5]. The advent of systems biology has provided transformative opportunities for researching Dao-di herbs. This review explores the excellent traits and quality of A. lancea, discussing its historical evolution, resource distribution, phenotypic characteristics, genetic background, and environmental determinants of its geo-herbalism. These insights aim to elucidate the quality-forming mechanisms of Dao-di A. lancea, thereby enriching and expanding the theoretical framework of the adverse effects hypothesis in the context of Dao-di herb formation.

-

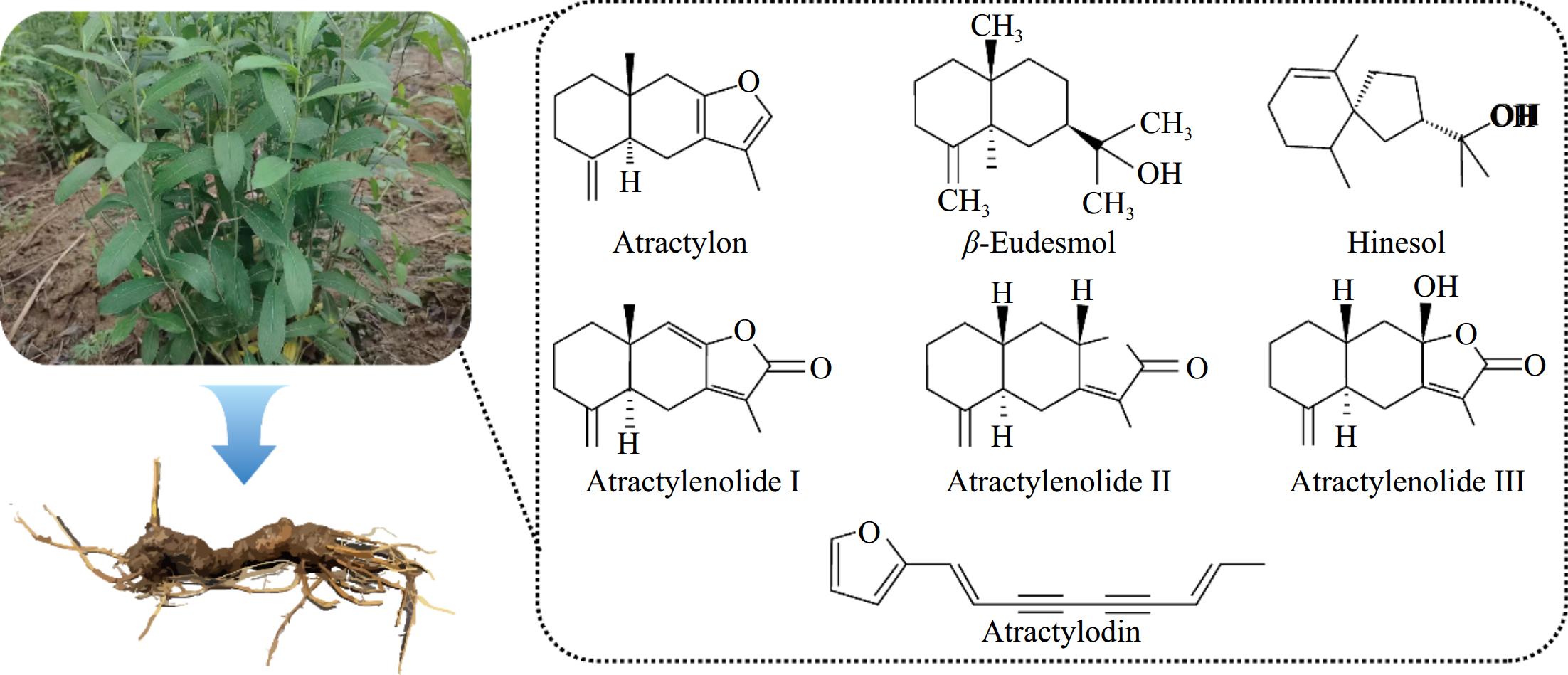

The dried rhizomes of A. lancea (Thunb.) DC. and A. chinensis (DC.) Koidz. are categorized as "Cāng zhú", which was included in the 2020 edition of the Chinese Pharmacopoeia. Among them, Mao-A. lancea is usually regarded as the Dao-di herb with a reasonable proportion of different essential oils and good clinical efficacy[6]. The medicinal herb Atractylodis rhizoma was first documented in 'Shennong Bencao Jing', wherein it was classified as a superior-grade substance, implying its exceptional therapeutic efficacy and low toxicity. The text clearly states that 'Long-term administration of herbal decoctions facilitates bodily lightness, extends longevity, and sustains satiety without causing nutritional deprivation'. Several studies have demonstrated that sesquiterpenes and polyene compounds are the main active substances of A. lancea, especially atractylodin, atractylone, β-eudesmol, and hinesol in the rhizome, which exhibit pharmacological activities such as antiviral, anti-inflammatory, hypoglycemic, antihypoxia, hepatoprotective, and diuretic effects[7−9].

Obvious regional characteristics

-

A. lancea is a perennial herbaceous plant that is widely distributed across China, including the provinces of Hubei, Jiangsu, Anhui, Inner Mongolia, Hebei, Henan, Shaanxi, Heilongjiang, Jilin, Liaoning, Shanxi, Ningxia, Gansu, and Qinghai. According to ancient records, the Dao-di production area of A. lancea had changed. In fact, the Northern Song scientist, Su Song, documented the shifting biogeography of A. lancea, as follows: 'It used to grow in the valleys of Zhengshan, Hanzhong, and Nanzheng, but now it can be found everywhere. Among them, the quality of "Cāng zhú" produced in Songshan and Maoshan areas is the best'. During the Ming Dynasty, Zhu Su's 'Herbal for Relief of Famines' also recorded that "Cāng zhú" originated in the valleys of Zhengshan and Hanzhong. Nowadays, it has also been discovered in the valleys of nearby counties, and the quality of "Cāng zhú" produced in Songshan and Maoshan is better; Lu Zhiyi also recorded in his 'Ben Cao Cheng Ya Ban Ji' that the quality of "Cāng zhú" produced in Songshan and Maoshan is relatively good. Conventionally, it is believed that the Dao-di production areas of A. lancea include Songshan in Henan and Maoshan in Jiangsu. Presently, scholars generally believe that A. lancea from the Maoshan region is a good quality Dao-di herb. The Dao-di production areas of A. lancea mainly include Jurong, Jiangning, the suburbs of Nanjing, Jintan, Liyang, Lishui, Dantu, and other places. A. lancea is generally distributed in the hilly and mountainous areas at an altitude of 40–400 m, with denser growth detected in the 40–150 m range. A. lancea thrives in loose sandy loam and soil containing humus, and the associated plants in the community include Quercus sp., Lindera glauca, and Vitex negundo var. cannabifolia, as well as shrubs and herbs such as Smilax china L., ferns, sedge, Eulalia speciosa, Eupatorium, Rosa laevigata Michx., Rubus coreanus Miq., Houttuynia Thunb., and Lysimachia clethroides[8].

Excellent traits

-

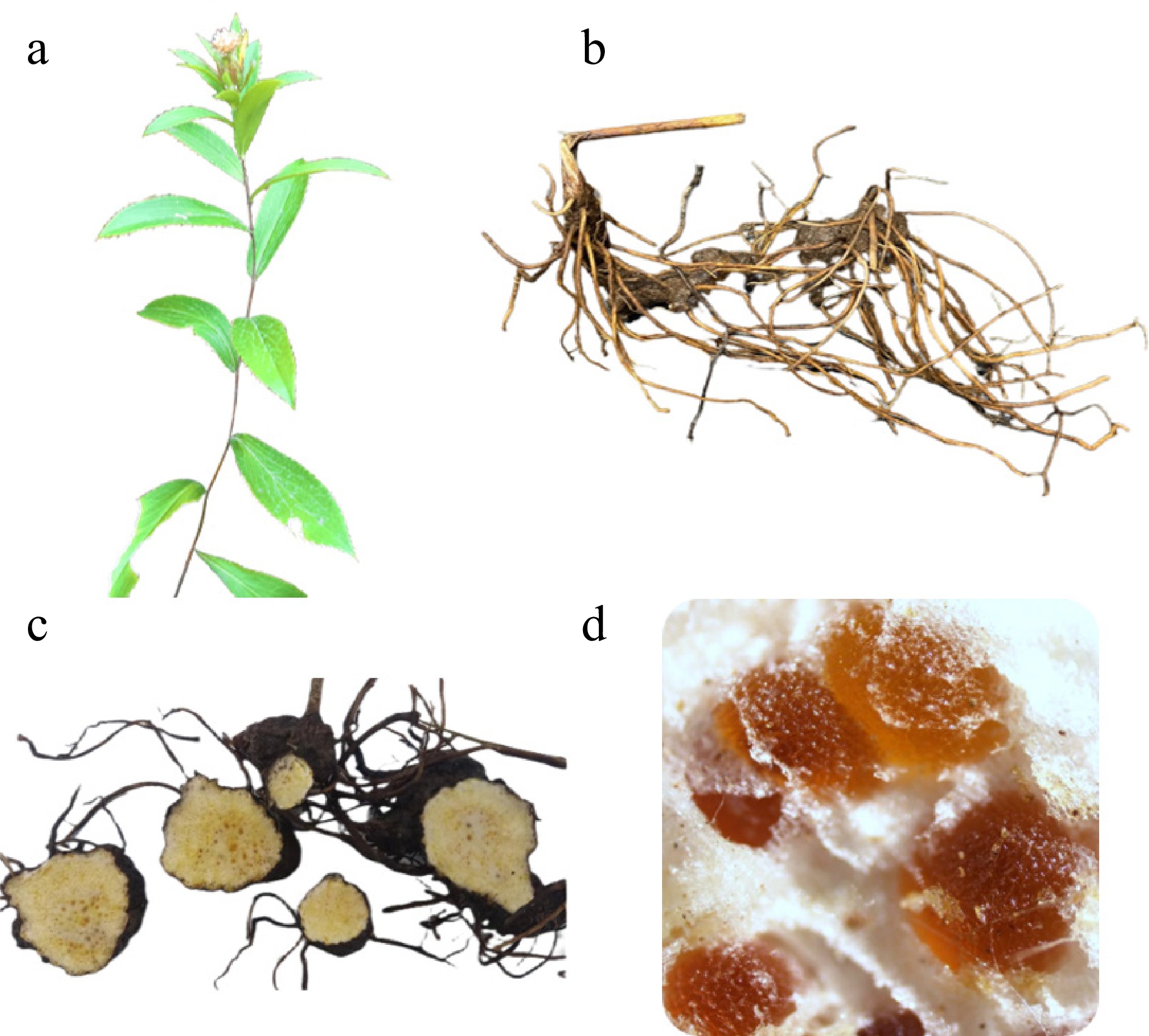

A. lancea from the Dao-di region (Maoshan, Jiangsu) exhibits distinct phenotypic characteristics, representing one of the excellent traits of its Dao-di herb status. Long-term observations of wild A. lancea populations in Tangshan Town (Nanjing City) and Huangmei Town (Jurong City) revealed that most leaves are unsplit, with elliptical or oblong shapes being predominant. The leaves of Maoshan A. lancea are leathery, with the widest part located near the middle or front. They lack petioles, with the leaf base either clasping or attaching to the stem. The leaf surface, especially on young leaves, is covered with arachnoid hairs[9]. A. lancea rhizomes are atypically moniliform or nodular-cylindrical, slightly curved, and casually branched. They have a dark external surface with wrinkles, horizontal folds, residual fibrous roots, and stem scars or remnants at the top. Above ground, the plant produces a single stem, with each stem scar indicating 1 year of growth. While A. lancea typically requires 3 to 5 years to reach medicinal maturity, its quality is not strictly dependent on growth duration. Field investigations have shown that rhizomes begin to deteriorate after 5 years, turning black, decayed, and exposing fiber bundles.

Atractylodis rhizoma demonstrates superior macromorphological markers; its texture is solid, and the sections are yellow-white. Scattered orange-yellow or brownish-red oil chambers can be observed on the cross-section, which may precipitate fine, needle-shaped white crystals upon exposure over time. The quality evaluation standard for A. lancea rhizomes— solid texture, multiple oil cavities on the cross-section, and strong aroma (Fig. 1)—has been an established criterion in TCM for thousands of years. Two hallmark traits of A. lancea are 'white frost' and 'oil cavity spots'. The frosting phenomenon, attributed to variations in the composition and content of volatile oils, reflects geographical differences in origin. Current research identifies β-eudesmol and hinesol as the main components of 'white frost'[10]. The formation of A. lancea 'white frost' is induced by the combined effects of medicinal herb variety, volatile oil content, environmental temperature and humidity, and exposure time. The process is a reflection of the excellent quality of medicinal herbs; the higher the volatile oil content, the more pronounced the white frost becomes[11]. The oil cavity spots appear as brownish-yellow dots in the secretion sacs (oil chambers) of the rhizome cross-section. These chambers, rich in volatile oils, form the primary material basis for the medicinal efficacy of A. lancea. The color of the oil chambers varies with their formation time. Research from our group has identified atractylodin and 4E, 6E, 12E-tetradecyltrimene-8, 10-diyne-1, 3-diacetate as key metabolites responsible for the red coloration of the secretory cavities. Differential accumulation of atractylodin contributes directly to the observed color variations (red and yellow) in these cavities.

Figure 1.

Characteristics of plant morphology and rhizome traits of Atractylodes lancea. (a) Plant morphology of wild A. lancea. (b) Rhizome traits. (c) Cross-section of rhizome. (d) Cinnabar-like oil glands in A. lancea rhizome.

Unique quality standards

-

The rhizome of A. lancea is the Chinese medicine "Cāng zhú", which is valued for its pharmacological functions, including drying dampness, strengthening the spleen, dispelling wind, and removing cold. Essential oils, particularly sesquiterpenes such as atractylone, β-eudesmol, and hinesol, are the primary bioactive components and serve as key indicators for quality evaluation and origin identification of A. lancea. To date, over 200 compounds, including alkenes, alcohols, esters, ketones, and acids, have been identified in its rhizomes[12].

Polysaccharides, referred to as Atractylodis Rhizoma Polysaccharides (ARP), constitute a crucial non-volatile component contributing to the pharmacological efficacy of A. lancea. ARP exhibits a range of biological activities, including immunomodulatory, antitumor, antiviral, and antioxidant effects, making it a significant research focus[7]. Polysaccharides, as active ingredients, have a close connection with the superior efficacy of Dao-di herbs. The research on the biological activities of ARP is of great significance for the quality, safety, and effectiveness of TCM. Studies by Chang et al.[13] revealed that crude polysaccharides of A. lancea consist of 12 monosaccharides, including glucose, galacturonic acid (the most abundant), arabinose, mannose, and ribose. Ribose and allose were detected in A. lancea polysaccharides for the first time, offering novel insights into the material basis of its authenticity[14,15].

The pharmacological properties of A. lancea further underscore its clinical relevance. Atractylodin demonstrates anticancer activity by inducing apoptosis in tumor cells, while atractylone exhibits antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties and shows promise as an antihypertensive agent due to its ability to gradually lower blood pressure with sustained effects after discontinuation[16,17]. Hinesol and β-eudesmol effectively improve spleen deficiency in mouse models, normalize gastrointestinal motility, and increase body weight, aligning with their traditional use for strengthening the spleen and drying dampness[18]. Additionally, β-eudesmol and hinesol have analgesic effects and β-eudesmol specifically reduces the sensitivity of acetylcholine receptors in mouse skeletal muscles[19]. Mao-A. lancea (Dao-di herb) exhibits superior pharmacological effects relative to non-Dao-di A. lancea. It demonstrates antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, anti-gastric ulcer, liver-protective, hypoglycemic, lipid-lowering, and antitumor properties. The volatile oils, flavonoids, and alkaloids in Mao-A. lancea shows enhanced antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activities compared to those in non-Dao-di counterparts[20].

-

The superior quality of Dao-di herbs, including A. lancea, results from the interplay between genetic factors and environmental influences. Dao-di A. lancea is subject to multiple environmental stresses during its growth, which play a pivotal role in inducing the accumulation of specialized metabolites[21,22]. Zhou et al. investigated the molecular-level adaptive responses of Dao-di A. lancea under environmental stress, revealing that potassium deficiency and drought stress lead to significant changes in volatile compound accumulation and the activity of protective enzyme systems[23]. However, further research on gene expression in Dao-di herbs under such stress conditions is needed. Microorganisms, including fungi, also contribute to the plant's ability to withstand complex environmental stress. For instance, Yang et al. demonstrated that under drought stress[24], the endophytic fungus Acremonium strictum (AL16) increases the levels of soluble sugar, protein, proline, and antioxidant enzyme activity in A. lancea. It also reduces lipid peroxidation, enhances abscisic acid content in roots and leaves, and increases the root-to-shoot ratio, aiding the plant in coping with drought stress. Similarly, Zhang et al. reported that arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi enhance stress resistance in A. lancea by promoting cell membrane repair, increasing antioxidant enzyme activity, and supporting growth under high-temperature and drought conditions[25]. The variation in sesquiterpenoid content in A. lancea is closely linked to the geographical environment. Stress factors such as high temperatures, soil moisture, and nutrient content in the Maoshan area significantly influence sesquiterpenoid accumulation, which is believed to play a role in the plant's defense mechanisms (Table 1). Microbial metabolic interactions play a pivotal role in the synthesis and accumulation of chemical constituents in A. lancea, which is facilitated by nutrient exchange and stress responses. By synergistically degrading soil toxins or antagonizing pathogenic fungi (such as Fusarium), microbial communities maintain a stable rhizosphere microenvironment, thereby indirectly ensuring the stable accumulation of secondary metabolites in A. lancea. The synergistic expression of core functional microbiota (such as Pseudomonas) and host genes (such as the terpene synthase (TPS) family) enhances the production of secondary metabolites. Under the conditions of high temperature, drought, or heavy metal stress, rhizosphere microorganisms activate the defense genes of A. lancea by secreting stress-signaling molecules (such as 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-Carboxylic Acid (ACC) deaminase), while simultaneously modulating the metabolic flux to maintain the synthesis efficiency of sesquiterpenoids. For instance, specifically, microbial–host interactions under copper stress increased the contents of β-eudesmol in A. lancea. The rhizosphere microbial community in the Dao-di regions of Mao-A. lancea exhibits distinct regional characteristics, and the genome (such as the gene clusters involved in terpenoid synthesis) has coevolved along with host genetic variations to form a stable microbe-metabolite-environment interaction network that guarantees the chemical quality of Dao-di herbs.

Table 1. Chemical and biogeographic fingerprints of Dao-di herbs and the habitats of Atractylodes lancea.

Grade 1 Grade 2 Grade 3 Dao-di producing areas

of A. lanceaNon-Dao-di producing areas

of A. lanceaMorphological characteristics Excellent traits Spot of oil cavity Much Less Moniliform Moniliform, mostly long cylindrical Mostly nodular or mass-like in shape Quality Chemical type Atractylone : atractylodin : hinesol :

β-eudesmol0.70–2.00 : 1 : 0.04–0.35 : 0.09–0.40 0–7 : 1 : 9–147 : 6–100 Climate Temperature Annual average temperature 15–15.4 °C 8.8–15.4 °C The average lowest temperature

of the coldest month–2 to 1 °C –15 to 1 °C The average highest temperature

of the hottest month32 °C 27–32 °C Extreme minimum temperature –17.5 to –15.5 °C –25 to –13 °C Precipitation Annual average precipitation 1,000–1,160 mm 530–1,740 mm Soil Inorganic elements Potassium (K) element 146.0 mg/kg 279.5 mg/kg Soil microorganism Fungi Predominant bacteria: Fusarium, Ankylobacter, and Penicillium genera Predominant bacteria: Trichoderma, Fusarium, Aspergillus, and unclassified Ascomycota fungi Bacterium Predominant bacteria: Gallales and Burkholderia genera Predominant bacteria: Bacillus and Burkholderia genera The variations in climate, soil, and other environmental factors across different regions significantly affect the content and proportions of the four primary active components—hinesol, β-eudesmol, atractylone, and atractylodin—in A. lancea. These chemotypic differences lead to alterations in its efficacy for drying dampness and strengthening the spleen. The volatile oils, particularly these four main components, form the material basis for the excellent quality of A. lancea and are closely associated with the content and color of the secretory cavities in A. lancea. Additionally, the climate and soil conditions in different regions influence the coloration of cinnabar spots in the secretory cavities, further affecting the herb's dampness-drying and spleen-strengthening properties. The excellent quality of Dao-di A. lancea arises from the synergistic action of its volatiles, with atractylodin playing a dominant role. This efficiency is fundamentally linked to changes in the content and proportions of the key volatiles, which are influenced by soil microecology. Endophytic microorganisms and soil conditions impact not only the growth and development of A. lancea but also the composition and ratio of its volatiles. Guo et al.[26] reported that mild shading promoted sesquiterpenoid synthesis and accumulation in A. lancea by regulating photosynthesis and phytohormones. As a result, the total sesquiterpenoid content of 80% mild shading increased by 58%, 52%, and 35%, respectively, when compared to 100% strong light in seedling, expansion, and harvest stages; moreover, it increased by 144%, 178%, and 94%, respectively, when compared with 7% low light[26]. The biomass and volatile oil accumulation of A. lancea under different light treatments occurred mainly during the expansion period. The root biomass (23.18 and 28.38 g) and the content of four volatile oil components (i.e., atractylodin, atractylodin, hinesol, and β-eudesmol) (3.74% and 5.17%) in the red-blue (9:1) group were recorded during the expansion and maturation stages of A. lancea, followed by the red-blue (6:1) group, with the respective biomass of 18.32 and 25.15 g[27]. Wang et al. conducted comprehensive analyses of rhizosphere and rhizome microbial community structures in various habitats, alongside experiments with endophytic microbial agents. Their findings demonstrated that distinct microbial communities exist in the rhizosphere and rhizome of Dao-di A. lancea. Inoculation experiments with Paraburkholderia caryophylli, an endophytic bacterium isolated from the roots of A. lancea, revealed that these microbes promote the plant's growth and regulate the content and proportion of its core volatile components. Moreover, under high-temperature and drought stress, soil microorganisms significantly enhance the growth of A. lancea and the accumulation of volatile oils. However, the degree of drought substantially influences this effect, with more severe drought conditions reducing the benefits[28,29]. Studies on tissue-cultured seedlings of A. lancea from Jiangsu Province inoculated with geo-authentic soil microbes showed increased root biomass and elevated levels of atractylone and atractylodin in the rhizomes[30,31]. Through artificial climate chamber inoculation experiments, fungi were verified to enhance root rot resistance, promote growth, and boost the accumulation of the four primary components of Atractylodes rhizoma. Zhang's microevolution analysis[32], based on genome resequencing of the A. lancea population, identified genes associated with quality under environmental stress. The study demonstrated the role of the AlAAHY1 in regulating abscisic acid metabolism and hinesol accumulation, shedding light on the microevolutionary adaptation of Dao-di A. lancea. These findings indicated that the formation of Dao-di herbs represents a microevolutionary process of polygenic inheritance driven by environmental stress[32].

-

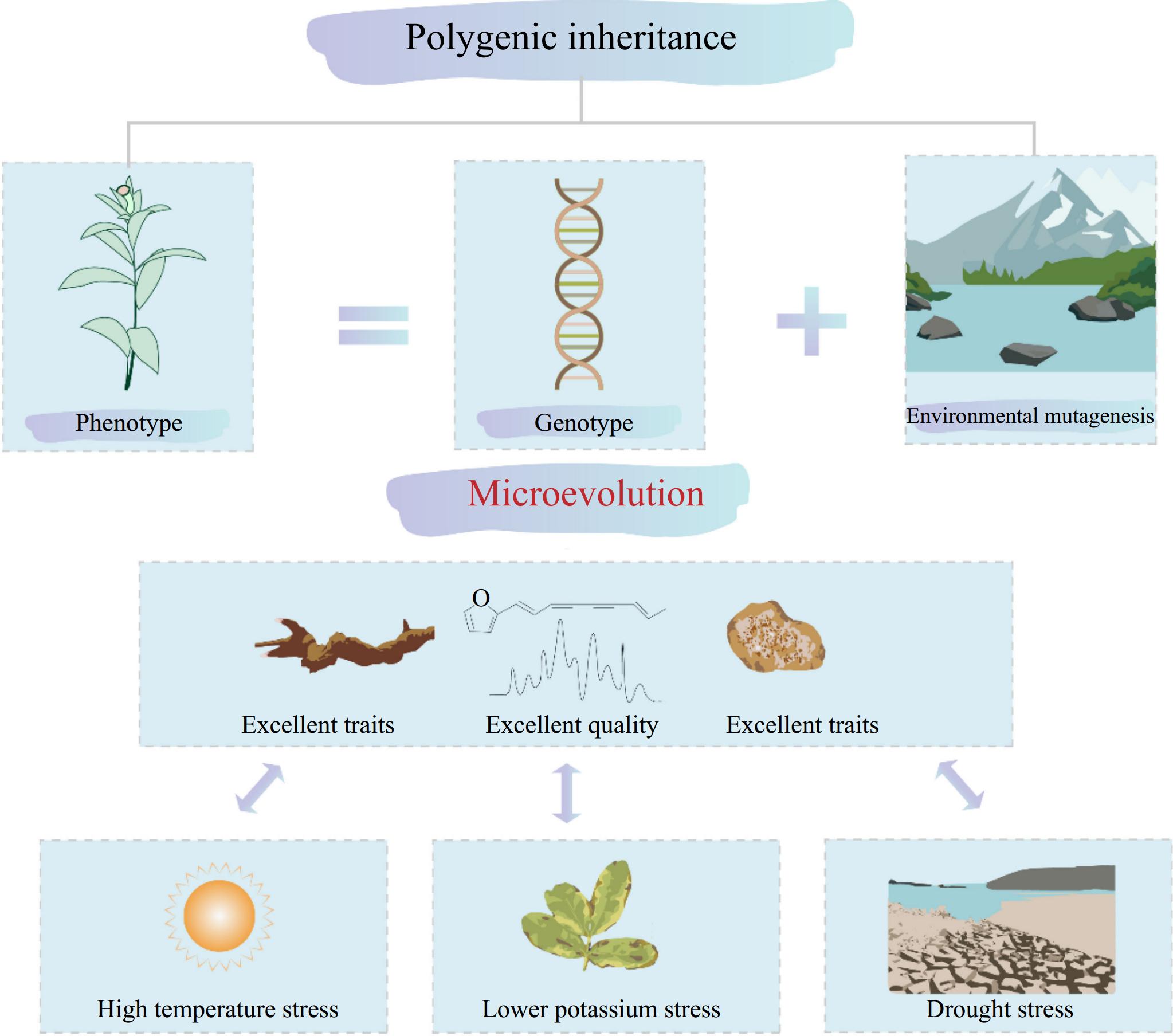

The biological essence of Dao-di herbs lies in the concept of 'same species, different places,' referring to how the same species adapts over time to diverse ecological environments. This prolonged adaptation induces mutations in the genetic material, resulting in unique genetic traits. The quality formation of Dao-di herbs occurs at the population level as changes in gene frequency, a process referred to as microevolution. This process can be represented by the equation: Microevolution = Genetic variation + Unequal transmission of genetic variation (Fig. 2). Genetic variation encompasses mutations, recombination, and gene flow at the individual level, while unequal transmission of variation describes the genetic changes at the population level resulting from natural selection and genetic drift during the adaptation of medicinal plants to their environment. Dao-di herbs represent a transitional state in species evolution, where gene flow continues to occur. Until reproductive isolation is achieved from other populations within the same species, these adaptations are collectively described as microevolutionary processes[1,32]. For instance, research on metabolite variation occurring during the domestication of Tartary buckwheat discovered that crop domestication typically reduces genetic diversity. The mGWAS results on Tartary buckwheat revealed that 384 mGWAS signals for 336 metabolites were under selection during the domestication, implying that the abundances of most metabolites were influenced by independent domestication processes. Furthermore, some related genes (such as FtMYB43, FtPAL, FtUGT74L2, and FtSAGH1) associated with variations across metabolite abundances in Tartary buckwheat were validated to illustrate the effect of domestication on the accumulation of secondary metabolites of the Tartary buckwheat[33]. Li et al.[34] compared the SNPs between local and wild soya beans and identified that the Trait-Associated SNPs (TASs) were significantly correlated with flowering time and bioclimatic variables, suggesting the genetic basis of environmental adaptability of soya bean landrace. A total of 17 flowering-time TASs and 27 bioclimatic TASs exhibited strong selection during domestication. Among the 44 TASs (17 flowering and 27 bioclimatic), 11 underwent selection in both domestication scenarios (i.e., subsequent landrace diversification and adaptation), three were selected only during domestication, 24 were selected during the diversification and adaptation of landraces, and six showed no selection. These results highlight the role of natural and artificial selection processes in adaptation to specific environments as well as the influence of bioclimatic variables on the patterns of genetic variation among soya bean landraces[34]. By comparing the metabolome, Zhang et al.[35] found that, during the domestication process from wild jujube to domesticated jujube, both primary and secondary metabolites underwent the process of significant selection. Notably, the reduction in the malic acid content was a crucial factor contributing to the decrease in sourness. In addition, triterpenoid metabolites experienced significant negative selection during domestication, which potentially impacted both the fruit flavor and environmental adaptability. Through mGWAS analysis, the key control loci for jujube metabolites and their genetic variation patterns were identified. Specifically, six loci were found to govern triterpenoid metabolite content, and a 2,3-oxidosqualene cyclase was identified as a significant gene involved in domestication selection[35]. At the population level, the genetic essence of A. lancea is typically a quantitative change process, which is distinct from that for other non-Dao-di herbs within the species mainly via alterations in gene frequencies within the population. At the individual level, it manifests as quantitative genetics controlled by polygenes with small effects or quantitative traits that are jointly controlled by polygenes, with small effects and major genes. Zhang et al. demonstrated through mGWAS analysis that terpenoids, polyene alkynes, esters, and ketones were the metabolites most strongly selected during the natural variation of A. lancea. The genetic diversity of genes in the sesquiterpene biosynthetic pathway genes, such as the TPS family, constitutes the genetic foundation for variations in core pharmacologically active compounds such as atractylone and β-eudesmol. Specific SNP loci exhibited significant correlations with the content of rhizome metabolites in A. lancea, suggesting that natural selection pressures have driven metabolic adaptive differentiation in Dao-di herbs from the Dao-di areas. The MYB transcription factor in Dao-di A. lancea activates relative sesquiterpene biosynthetic genes in the pathway through epigenetic modifications (i.e., DNA methylation), thereby displaying a high expression pattern in populations from the Dai-di Maoshan areas, which directly enhanced the accumulation efficiency of volatile oil components such as atractylone[32]. Moreover, stress responses can bolster the stability of active ingredient accumulation in A. lancea. For instance, drought, high temperature, and other stressors upregulate antioxidant enzyme genes in the ABA signaling pathway while simultaneously promoting the synthesis of phenylpropanoid metabolites. This aspect maintains the stability of active ingredients in the rhizome and mitigates the impact of environmental fluctuations on medicinal quality. Phenotypic plasticity further optimizes the morphology and composition of Atractylodis rhizoma, encompassing the coevolution of rhizome morphology and metabolism, as well as the regulation of secondary metabolism through microbial interactions. Research has indicated that the rhizome density of Dao-di A. lancea is positively correlated with the content of active ingredients[32]. Mechanical stress signals coordinate rhizome expansion and secondary metabolite accumulation by regulating cell wall remodeling genes (e.g., cellulose synthase genes), which imparts the characteristics of 'excellent traits, excellent quality'. The rhizosphere microbial community influences the efficiency of terpenoid synthesis in A. lancea through the exchange of metabolites, such as plant hormones and precursors of secondary metabolites. However, the systematic dissection of this mechanism warrants further in-depth research.

The geo-herbalism of A. lancea, characterized by its excellent traits and superior quality, represents a microevolutionary process involving multiple genes and quantitative inheritance under environmental stress. This microevolution under environmental stress manifests as adaptation and variation at both the population and individual (cellular) levels. The adaptation mechanisms involve a wide array of processes, including physiological and biochemical effects of organisms, signal transduction and its network interaction, functional gene expression and regulation, environmental stress memory, and phenotypic trait adaptation, presenting complex systemic suitability characteristics[36]. In addition, key components such as atractylodin and atractylone, along with their ratios to other volatile oil constituents, play significant roles in defining the authenticity of A. lancea. Dao-di herbs of A. lancea are subjected to various environmental stresses, including high temperatures, low light conditions, and pathogens like Fusarium oxysporum. Under moderate stress conditions, these environmental factors drive an increase in the production of atractylodin and atractylone extracts, underscoring the pivotal role of environmental stress as a driving force in the formation of Dao-di herbs (Fig. 2). In summary, the microevolution of A. lancea has synergistically shaped the 'unity of form and quality' characteristics of authentic Atractylodes Rhizoma through genetic variation screening, environmental adaptation regulation, and phenotypic plasticity optimization. In the future, we need to focus on multi-dimensional interaction network analysis to realize the systematic regulation of Atractylodes Rhizoma quality formation.

Unique adaptive features appear in the chemical compositions of A. lancea

-

The volatile oils of A. lancea are primarily composed of sesquiterpenoids (e.g., atractylone, β-eudesmol, hinesol, atractylenolide I, II, and III) and polyacetylenes (e.g., atractylodin) (Fig. 3). Secondary metabolites serve as the foundation of Dao-di herb authenticity, resulting in distinctive chemotypes and superior efficacy compared to other populations of the same species. Over its evolutionary history, A. lancea has developed self-organizing chemical characteristics uniquely adapted to its environment. In Dao-di production areas, the volatile oil components of A. lancea exhibit a specific ratio—atractylone, atractylodin, hinesol, and β-eudesmol are present in a ratio of 1.2:1:0.2:0.3. In contrast, non-Dao-di regions produce a significantly different ratio of 0.4:1:22.4:19.6. Furthermore, the peak area ratio of oligosaccharide isomers (fruit-fructooligosaccharides/sucrose-fructo-oligosaccharides) is greater than one in Dao-di A. lancea but less than one in other production areas[13]. This specific composition and ratio of volatile oils are direct outcomes of habitat adaptation, making the chemical composition a key determinant of the phenotypic specificity of Dao-di A. lancea[32]. Guo et al.[8] identified a strong correlation between volatile oil variations and the geographical distribution of A. lancea, noting a continuous decline in the content of six main components from southern to northern regions. A. lancea from different origins can be categorized into two chemical types. One is represented by "Cāng zhú", which is mainly found in Hubei, Anhui, Shaanxi, Southern Henan, and other places. The total amount of the volatile oil in Hubei type (HBA) is high, and mainly composed of hinesol and β-eudesmol, with or without very small amounts of atractylone and atractylodin. The other type, Maoshan type (MA), is mainly represented in Maoshan, Jiangsu Province, including Jiangsu, Shandong, Hebei, and northern Henan. Its total volatile oil is low, and mainly composed of atractylone and atractylodin. Zhang et al.[3] conducted a comprehensive volatile metabolomics analysis of 133 wild A. lancea samples from 12 provinces, systematically categorizing them into two main chemical types with three subtypes, namely MA (Maoshan A. lancea, authentic chemical type), NA (Northern A. lancea), and SA (Southern A. lancea). Their findings highlighted 15 chemical compounds critical for origin tracing and quality evaluation. The research confirmed that the biological essence of 'high-quality' A. lancea lies in its ecological chemical type, formed as a result of the species' adaptation to distinct regional ecological environments[3]. The metabolic spectrum of A. lancea from Dao-di production areas is markedly different from that of other regions in China, underscoring the unique adaptive features of Dao-di A. lancea’s chemical composition. Furthermore, we observed significant differentiation between cultivated and wild A. lancea in terms of phenotypic plasticity (i.e., morphology and growth cycle) and chemical adaptability (i.e., secondary metabolism and environmental response). The total volatile oil content in wild A. lancea (ranging from 2.5%–4.0%) was notably higher than that in the cultivated varieties (ranging from 1.8%–2.5%). The active ingredients, such as β-eudesmol and atractylone, account for 60% of the total content, which is correlated with the high expression of stress-resistant genes. Although the volatile oil content in cultivated varieties can be increased to 2.8% through stress induction (such as through water control and shading), the composition tends to become more single. The atractylodin content in the Atractylodis rhizoma of wild varieties was 0.15%–0.25%, while that in cultivated varieties decreased to 0.08%–0.12% due to continuous cropping obstacles (enrichment of soil pathogenic bacteria). In the future, therefore, it will be necessary to address the contradiction between yield and quality so as to achieve sustainable resource utilization through ecological simulation planting and the regulation of microbe–host interactions.

Gene specialization of A. lancea

-

Dao-di herbs represent distinct populations shaped by their specific habitats over long-term evolutionary processes. These populations, formed in different regions but belonging to the same species, exhibit unique genetic and phenotypic characteristics. In biological terms, Dao-di herbs are stable, naturally occurring, or cultivated populations that thrive in particular geographic locations and timeframes. Traditionally, Dao-di herbs are considered to share a common genetic background but display superior qualities compared to their non-Dao-di counterparts[37]. Advances in DNA analysis techniques have enabled in-depth investigations into the specialized genotypes of Dao-di herbs, elucidating their genetic uniqueness. For instance, random-amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis of A. lancea "Cāng zhú" from its authentic production region, the Maoshan area in Jiangsu Province, China, revealed a direct correlation between geographical distribution and genetic diversity—the smaller the geographic range, the lower the genetic diversity[38]. Guo et al. explored the genetic diversity of A. lancea from various regions. Their findings demonstrated that the genetic distance between individuals of Maoshan A. lancea was relatively small, indicating a shared and consistent genetic background. Moreover, both population-level and individual-level analyses grouped Maoshan A. lancea separately from other populations, highlighting genetic differentiation driven by long-term environmental adaptation[39]. Wang et al. used molecular phylogeography to analyze the chloroplast genome variation and phylogenetic relationships of Atractylodes species[40]. This study revealed significant genetic differentiation between Dao-di A. lancea populations and other A. lancea populations. The phylogenetic analysis confirmed that Atractylodes species form a monophyletic clade, reflecting a clear evolutionary relationship within the genus. Furthermore, A. lancea has undergone macroevolution alongside other Atractylodes species. Through long-term breeding and domestication, Dao-di herbs develop unique genotypes. The more pronounced the authenticity of a Dao-di herb, the greater its degree of genetic specialization. At the individual level, authenticity is reflected in quantitative inheritance, controlled by multiple minor-effect genes, or as a quantitative trait regulated by the combined actions of minor-effect genes and major-effect genes. The genetic specialization and chemical adaptability of Dao-di A. lancea also offer molecular markers and metabolic network targets for the evaluation of the core germplasm resources. A targeted breeding strategy that combines genome selection and ecological simulation is expected to overcome the critical barriers that currently impede the simultaneous optimization of yield and quality in cultivated species. In the future, therefore, an intelligent breeding platform integrating multi-omics data will be needed to facilitate the precise regulation of germplasm innovation and the production of Dao-di Atractylodes rhizome.

Secondary metabolites, a hallmark of Dao-di herbs, represent a classic example of polygenic traits, as confirmed by numerous modern studies. These metabolites serve as direct and vital indicators of the authenticity of TCM. Their biosynthesis involves numerous and intricate metabolic steps, each catalyzed by at least one gene. For instance, the production of terpenes, alkenes, alkaloids, flavonoids, anthraquinones, and coumarins—secondary metabolites integral to medicinal quality—requires an array of metabolic steps and the involvement of numerous key enzyme genes across diverse pathways[41]. The biological essence of Dao-di herbs lies in the expression of genotypes influenced by environmental factors. Functional gene expression and regulation studies are central to understanding the genetic foundation of Dao-di herbs. Using metabolome genome-wide association studies (mGWAS), our research group identified 10 candidate genes significantly associated with changes in the key medicinal quality traits of A. lancea. These include genes encoding zinc finger proteins, GATA transcription factors, glycosyltransferases, and abscisic acid 8'-hydroxylase (AlAAHY1), a crucial enzyme in abscisic acid (ABA) catabolism. ABA accumulation is among the earliest plant responses to drought stress, highlighting its role in environmental adaptation[42]. Additionally, selective sweep analysis of the A. lancea genome identified MYB transcription factor (AlMYB59) and heat stress transcription factor (AlHSTF3) as key players in environmental stress adaptation. These factors are significantly associated with responses to low-potassium and high-temperature stresses, critical conditions contributing to the formation of Dao-di A. lancea in Maoshan[43,44]. Furthermore, we explored the molecular mechanisms underlying A. lancea’s responses to light and temperature signals. Results showed that light intensity and wavelength significantly influence the balance of root growth and metabolism. Reducing light intensity or the proportion of far-red light affects the degradation of AlHY5 protein mediated by E3 ubiquitin ligase AlCOP1. This reduction relieves the inhibition of key enzymes like DXS in the atractylodin biosynthesis pathway, thereby enhancing the synthesis of active ingredients in A. lancea. Lu et al. investigated the impact of copper stress on the accumulation of three pharmacologically active components in A. lancea and the expression of two key enzyme genes involved in their biosynthesis. The results indicated that the expression of the key enzyme genes HMGR and FPPS significantly contributes to the content of β-eudesmol and atractylone. These findings also demonstrate that these two key enzymes play a pivotal role in regulating the synthesis of β-eucalyptol and atractylone, which then exerts a crucial influence on the synthesis and accumulation of these pharmacologically active components in A. lancea[45].

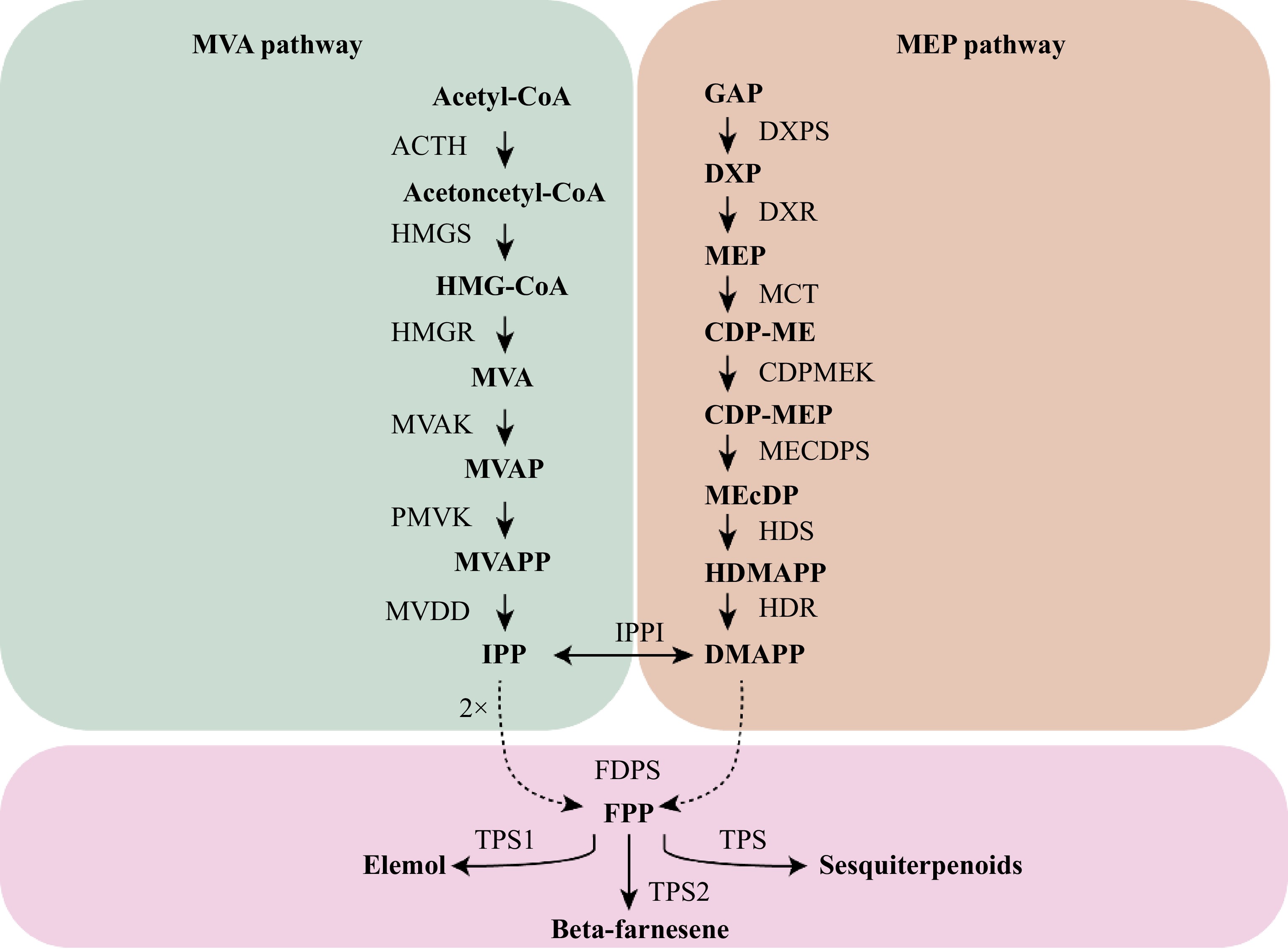

Terpenes synthesized by terpene synthase (TPS) play a crucial role in mediating plant responses to biotic and abiotic stress. Comparative genomic analysis revealed that tandem repeats have significantly expanded the TPS gene family in A. lancea[32,46]. Sesquiterpenes, known for their diverse pharmacological effects, are greatly influenced by environmental factors. The enrichment of sesquiterpenes serves as a key adaptive strategy for A. lancea and is a major contributor to its authentic formation as a Dao-di herb[47]. Previous studies have demonstrated that A. lancea populations from different regions can be classified into two chemical types based on sesquiterpene content[3,8]. These differences are regulated by key enzyme genes involved in terpenoid biosynthetic pathways[3]. Wu et al.[48] identified 42 differentially expressed genes associated with terpenoid biosynthesis in the rhizomes of two chemotypes of A. lancea. Among these, six candidate sesquiterpene synthase genes were highly expressed in the Dabieshan chemotype. Enzymatic characterization revealed that AlTPS1 catalyzes the conversion of the precursor farnesyl diphosphate (FPP) to elemol, while AlTPS2 produces β-farnesene from the same substrate[48]. The upstream genes in the terpenoid synthesis pathway are responsible for synthesizing the common precursors of secondary metabolites, whereas the downstream genes primarily determine the diversity of types and structures of secondary metabolites. The biosynthesis of sesquiterpenoids in A. lancea initiates through the mevalonate (MVA) pathway, involving specific steps such as three molecules of acetyl-CoA are condensed to form MVA, which is then phosphorylated and decarboxylated to form isoprenoid diphosphate (IPP) and its isomer dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP). IPP and DMAPP are converted to farnesyl diphosphate (FPP) by farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase (FPPS), which serves as the direct precursor of sesquiterpenes (Fig. 4)[49]. Zhang et al. analyzed the seasonal patterns affecting the quality of Dao-di A. lancea and identified 13 TPS candidate genes associated with sesquiterpene biosynthesis pathways. A joint analysis of metabolic and transcriptomic data highlighted that genes involved in the MVA pathway were predominantly expressed during the growth period. In contrast, specific genes within the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway—such as AlDXS1, AlDXR1, AlCMK1, AlMDS1, AlHDS2, AlHDS3, and AlHDR1—also showed high expression during this phase. These findings suggest that highly expressed genes during the growth period provide precursors essential for sesquiterpene biosynthesis in the rhizomes of A. lancea. Further research focused on the TPS genes specific to terpenoid biosynthesis revealed 10 TPS-encoding genes that are predominantly expressed in the roots or rhizomes of A. lancea. These include AlTPS9, AlTPS17, AlTPS21, AlTPS23, AlTPS24, and AlTPS21-3. These genes are believed to directly contribute to the synthesis of sesquiterpenes accumulated in the rhizomes[50].

Stress will promote the formation of Dao-di A. lancea

-

The active compounds in TCM are typically small molecules derived from secondary metabolism. Numerous studies have demonstrated that environmental stressors can enhance the production of secondary metabolites in medicinal plants[51]. Environmental factors not only influence the genotype of Dao-di herbs over extended periods but also regulate gene expression, impacting the formation and accumulation of secondary metabolites[52]. Secondary metabolites, which function as phytoalexins in medicinal plants, play a critical role in plant defense. Under environmental stress, these plants release secondary metabolites, also known as allelochemicals, into the external environment to inhibit the growth of competing plants and improve their survival. Adverse conditions such as drought, extreme cold, mechanical injury, high temperatures, or exposure to heavy metals can stimulate the production and release of these compounds[53,54]. Consequently, environmental influence on the formation of Dao-di herbs is primarily expressed as a 'stress effect'. Guo et al.[8] reported that the habitat of Mao-A. lancea experiences higher temperatures, shorter drought seasons, and greater precipitation compared to other populations of A. lancea. Their findings suggest that the formation of Mao-A. lancea is associated with high-temperature stress. Furthermore, they demonstrated that nutrient stress, combined with high-temperature and low-potassium conditions, promotes the production of essential oil compounds resembling those of Dao-di herbs in greenhouse experiments[8]. High temperature was identified as the primary limiting factor for A. lancea, while the interaction between temperature and precipitation significantly influenced the composition of essential oil. The Dao-di production area for A. lancea is located on the southeastern edge of the species' distribution, where plants are frequently exposed to multiple environmental stresses. These combined stressors are key factors in the authentic formation of A. lancea. Under drought stress, the rhizomes of A. lancea exhibit significantly increased levels of atractylenolide II, β-eudesmol, atractylone, and heightened activity of the key enzyme HMGR. Moderate stress elicits the strongest response in these parameters[55]. Guo et al. also observed that shading affects the growth and secondary metabolism of A. lancea. Field experiments revealed that reducing natural light to 80% intensity enhances the accumulation of four primary active ingredients and increases biomass (fresh and dry weight of roots and stems). Thus, weak light stress supports the high-quality formation of A. lancea[26]. Additionally, research by Li et al. demonstrated that high-temperature stress significantly impacts the photosynthetic and physiological characteristics of A. lancea leaves from various regions. Temperatures of 40 °C notably influence the chlorophyll fluorescence properties of A. lancea, underscoring the critical role of high-temperature stress in the authentic formation of Dao-di A. lancea[56,57].

-

The authenticity of A. lancea is governed by complex genetic factors, involving microevolutionary processes of multi-gene quantitative inheritance under environmental stress. These traits encompass genetic variation, environmental variation, and gene-environment interactions[58]. While inherited in a Mendelian manner, environmental influences may obscure the discontinuous variations of genotypes, leading to continuous phenotypic variations. For instance, the volatile oil components of A. lancea exhibit geographical variability and distinct chemical profiles. Additionally, its phenotypic traits—such as leaf shape, degree of leaf splitting, number of stem branches, style morphology, and bracts—demonstrate plasticity and follow identifiable variation patterns. The unique geographical, climatic, and ecological conditions of A. lancea are crucial factors influencing its authenticity. Ecological suitability analyses indicate that A. lancea, in its native Mao-shan region, experiences environmental stresses such as high temperature, high humidity, and nutrient deficiency. Studies show that moderate environmental stress enhances growth and secondary metabolite accumulation, while excessive stress negatively impacts biomass production, growth, and development.

The wide distribution of A. lancea across China results in significant geographical variability in its volatile oil composition, influencing its classification. Modern medicine has identified substantial therapeutic potential in A. lancea, with its volatile components demonstrating efficacy in treating cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, regulating gastrointestinal function, and boosting immunity. Non-volatile components, such as polysaccharides and starch, are increasingly utilized in health food, feed additives, and veterinary drugs. As awareness of natural medicines grows with rising living standards, the demand for A. lancea has increased annually, along with its applications. However, the Maoshan region, a Dao-di production area for A. lancea, faces challenges such as resource depletion due to unsustainable harvesting practices and severe habitat destruction. Research into the authentic characteristics of A. lancea is essential for optimizing its ecological environment and ensuring the sustainable use of this valuable resource. Japanese transplantation experiments further underscore the role of environmental factors in shaping the authenticity of A. lancea. When non-authentic A. lancea was transplanted to the Nanjing Botanical Garden Mem (within the authentic production area), the volatile oil composition of the plants became closer to that of authentic Mao-A. lancea after 2 to 3 years. These findings highlight the critical influence of environmental conditions in the formation of Dao-di A. lancea.

This research was financially funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2023YFC3503801), Scientific and Technological Innovation Project of China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (Grant Nos CI2024C001YN, CI2023E002, ZZ2024036, ZK2024010), Jiangxi Science and Technology Innovation Base plan project-the introduction of joint research and development institutions (Grant No. 20222CCH45004), China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA (Grant No. CARS-21), Key Project at Central Government level: the ability establishment of sustainable use for valuable Chinese medicine resources (Grant No. 2060302).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Zhang CC, Guo LP, Wang S; data collection: Zhang CC, Feng LF, Li Q; data analysis and interpretation of results: Kang CZ, Zhou L, Sun JH, Wan XF; writing − original draft: Zhang CC, Feng LF, Zhang YF, Kang CZ, Yan BB; writing − review and editing: Zhang CC, Feng LF, Zhang YF, Guo LP, Wang S. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The complete chloroplast genome sequences of Atractylodes were submitted to GenBank (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Other data mentioned in the article, such as chemical composition and phenotype, have not been made public yet.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Cheng-cai Zhang, Ling-fang Feng

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang CC, Feng LF, Zhang YF, Kang CZ, Zhou L, et al. 2025. Research progress on the formation mechanism of 'excellent traits, excellent quality' and Dao-di characteristics of Atractylodes lancea: a review. Medicinal Plant Biology 4: e027 doi: 10.48130/mpb-0025-0021

Research progress on the formation mechanism of 'excellent traits, excellent quality' and Dao-di characteristics of Atractylodes lancea: a review

- Received: 28 February 2025

- Revised: 13 April 2025

- Accepted: 12 May 2025

- Published online: 04 August 2025

Abstract: The geo-herbalism of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is defined by excellent traits and excellent quality, which result from a microevolutionary process involving polygenic quantitative inheritance under environmental stress. Dao-di herbs exemplify the interaction between genotype and environment, wherein phenotypes emerge as a product of genotypic expression modified by environmental factors. Atractylodes lancea, a representative Dao-di herb, is distinguished by its specific geographical origin and distinct phenotype. Ecological suitability analysis indicates that A. lancea thrives in its native region of Maoshan, where it endures environmental stresses such as high temperature, humidity, and nutrient deficiencies. This review summarizes the excellent traits and quality of A. lancea and explores the environmental mechanisms underlying its geo-herbalism. By examining its microevolutionary adaptation to environmental stress, this study extends the theoretical framework of the adverse effects hypothesis in the formation of Dao-di herbs.

-

Key words:

- Atractylodes lancea /

- Dao-di herbs /

- Microevolution /

- Quality formation