-

Nitrogen (N) is an essential element that limits the growth of all living organisms and serves as a critical component of terrestrial biogeochemical cycles[1]. The availability of N compounds is governed by complex cycling processes that involve transformations across various chemical forms and pathways[2,3]. These processes and resulting N availability critically influence the composition, structure, and functionality of terrestrial ecosystems. Soils, as the primary terrestrial nutrient reservoir, maintain global nitrogen stocks and facilitate plant nitrogen uptake and utilization[4]. However, excessive nitrogen compounds and nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions in soils can cause various pollution problems in ecosystems[5,6]. Consequently, effective management of soil nitrogen stocks is crucial for maintaining soil quality, ensuring nutrient availability for plants, and mitigating the challenges posed by global warming[7]. Soil total available nitrogen, comprising both organic and inorganic forms, reflects the net balance of nitrogen inputs and outputs. Soil organic nitrogen constitutes the dominant fraction of total available N; however, its availability for plant growth is determined by microbial-induced mineralization of organic-N to inorganic forms[8]. Generally, soil nitrogen pools, composition, and cycles are governed by the interactive effects of multiple natural and anthropogenic drivers, including climate, plant nitrogen-use strategies, and soil properties[1,2,5,9].

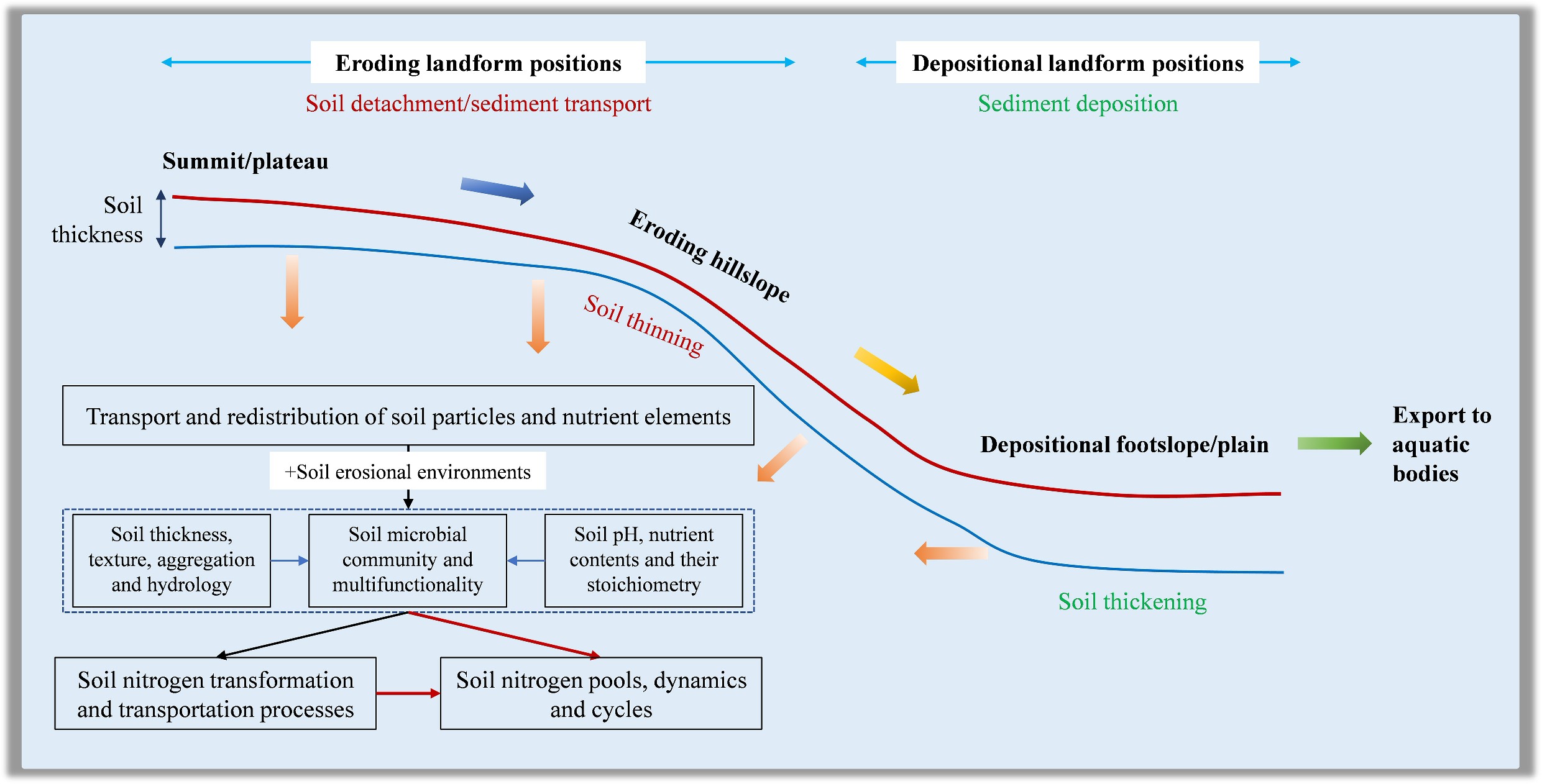

Soil erosion, recognized as a prevalent soil threat and global environmental issue, laterally redistributes approximately 28 Pg of sediment and degrades approximately 1.1 billion hectares of land annually worldwide[10]. The redistribution of sediments is often accompanied by soil nutrient turnover and loss, establishing soil erosion as a critical driver of terrestrial biogeochemical cycles[11,12]. Through detachment, transport, and deposition of surface soil, erosion redistributes soil materials while modifying physical and chemical properties, microbial community structures, and nutrient cycling pathways[12,13]. Over recent decades, the impacts of soil erosion on soil properties and terrestrial biogeochemical cycles have attracted significant global attention, driving substantial advances in research. However, most studies have focused on the effects of erosion on soil organic carbon (SOC) transformations, stocks, stability mechanisms, or greenhouse gas emissions[11,14−16]. Despite the importance of N availability for primary production, relatively few data exist on nitrogen dynamics in eroding landscapes[13,17]. Globally, approximately 23–42 Tg of nitrogen are eroded annually from arable lands, with erosion-induced lateral nitrogen fluxes comparable in magnitude to fertilizer inputs[10]. In the coming decades, global soil erosion rates are projected to increase with anticipated climate change, potentially resulting in substantially higher soil nitrogen losses[1]. The carbon and nitrogen cycles are closely interconnected in terrestrial ecosystems due to their tight coupling within organic matter and the influence of nitrogen availability on soil carbon storage[18]. Consequently, quantifying the effect of soil erosion on carbon cycling alone is insufficient for comprehensively assessing its impact on biogeochemical cycles[10,12]. Therefore, advancing the understanding of how erosion and deposition affect the redistribution and bioavailability of nitrogen in eroded landscapes is essential to elucidate the broader impacts of soil erosion on nutrient cycling, availability, and loss.

The objective of this review is to synthesize current research on the influence of soil erosion on nitrogen cycles, with a specific focus on systematically examining its impacts on nitrogen transport, nitrogen pools, influencing factors, key transformation processes, and underlying mechanisms. Furthermore, this review identifies priorities for future research to clarify the role of soil erosion in nitrogen cycles.

-

Soil nitrogen (N) pool is predominantly concentrated in topsoils (> 95%) and consists primarily of organic forms (> 90%), which are chemically bound to soil particles and are thus relatively susceptible to erosional transport[19]. Rainfall-induced water erosion is a key driver of soil N transport and redistribution[12]. Under varying rainfall and surface conditions, runoff generation typically involves several dominant processes: infiltration-excess or saturation-excess overland flow, lateral subsurface flow within the soil profile, and deep percolation to groundwater[20]. During various rainfall events, these processes regulate both the spatial distribution of rainwater and the dominant erosion mechanisms on slopes, thereby directly influencing the pathways, magnitude, and forms of N transport.

Soil erosion via surface runoff directly impacts the upper soil profile, driving the lateral redistribution of N-rich topsoil downslope and generating distinct spatial patterns of soil N dynamics across landscapes[13,21,22]. Typically, particulate organic N associated with fine soil particles is preferentially removed from erosional zones, depleting local soil N stocks. Conversely, these nutrient-rich sediments accumulate in depositional areas, leading to localized N enrichment[18,23]. In a relatively undisturbed zero-order watershed in northern California, Berhe & Torn[13] reported that erosion transports 0.26–0.47 g N m−2 year−1 from eroding slope positions (summit and slope), with approximately two-thirds of the displaced N being deposited in lower landscape positions (hollow and plain). As a result, soils in depositional zones were found to contain up to three times more N than those in eroding areas. Based on a synthesis of 39 studies examining carbon and nitrogen contents along eroded slopes, Holz & Augustin[18] observed that eroded sediments were enriched in N by about 50% compared to source soils, with the degree of enrichment influenced by slope gradient and soil texture.

In addition to lateral transport via surface water erosion, subsurface hydrological pathways are recognized as important routes for N transport and redistribution, affecting soil N stocks[24,25]. Subsurface flow generation is governed by soil conditions (e.g., pore structure and hydraulic conductivity), rainfall characteristics, and infiltration dynamics[26]. Dissolved total nitrogen (TDN), comprising mineral N and dissolved organic N, readily accumulates in surface soil and exhibits high mobility, making it susceptible to vertical leaching via subsurface flow. This vertical migration and leaching not only alter soil N pool composition and bioavailability along the soil profile but also contribute to substantial N loss. For instance, along 100 cm soil profiles in a sloping agricultural landscape, Shi et al.[23] reported that erosion facilitated the movement of both dissolved inorganic and organic N to deeper soil layers. Dissolved N dominated in deeper layers (40–100 cm) at erosional sites (where TDN constituted 18%–50% of total N), but not at non-eroding and depositional sites (where TDN constituted only 8%–20% of total N). Furthermore, studies indicate that N transport and loss rates can be significantly higher in subsurface runoff than in surface runoff. Artificial rainfall experiments on purple soil in the Three Gorges Reservoir Area demonstrated that macropore-driven subsurface flow was the dominant pathway for substantial N loss across all rainfall events, particularly for nitrate-N, which was predominantly transported via this pathway[24,25]. Specifically, Wang et al.[25] observed that over 90% of total N was lost through interflow, with nitrate-N accounting for more than 50% of that loss. The high N transport and loss rates via interflow and deep percolation into groundwater can significantly reduce N use efficiency for deep-rooted plants and contribute to adverse ecological and environmental effects[27].

The erosional transport and loss rates of soil N are governed by interactions among multiple natural and anthropogenic factors, including topography, climate, land-use and land-cover change, and agricultural management practices[12]. Topography and climate control soil formation, erosion, and deposition processes, thereby significantly influencing N cycling across the landscape. Stacy et al.[28] reported sediment exports ranging from 0.4 to 177 kg ha−1 across eight temperate forest catchments in California, with nitrogen exports in sediment between 0.001 and 0.04 kg N ha−1, varying with catchment climate and topography. Extensive research has examined the effects of topographic slope and landscape position on various aspects of N cycling, including availability, leaching, and retention[18,29,30]. For example, Weintraub et al.[29] suggest that elevated N loss resulting from high rates of soil and particulate organic matter erosion on steep slopes can drive considerable spatial variation in N cycling and availability.

Land use and land cover (LULC) types and their changes are key anthropogenic factors controlling soil erosion rates and organic matter accumulation, thereby influencing nutrient cycles[31]. In recent years, the combined impacts of land use type and soil erosion on N dynamics in sloping landscapes have been widely studied. Globally, soil erosion rates on agricultural lands are substantially higher than on forestlands and other semi-natural vegetated areas due to more frequent farming disturbance and lower vegetation cover[32]. Consequently, studies confirm that croplands are more prone to N transport and loss than forestlands during erosion events. In the south subtropical zone of China, Tang et al.[33] demonstrated that agricultural land, under the interactive effects of sheet erosion and frequent tillage, exhibited significant declines in soil structural stability and total N content in both bulk soils and aggregates compared to native woodland. Furthermore, land use and cover changes can alter soil N sequestration and stocks due to associated changes in vegetation cover and erosion rates[22,34]. For example, in the black soil region of Northeast China, Li et al.[35] found that converting forest to cropland decreased soil structural stability due to tillage-induced loosening and reduced N concentrations and stocks along the soil profile, with these reductions being substantially greater under heavy erosion conditions. However, a plot-scale study in northern Vietnam by Anh et al.[36] reported that forests did not always exhibit lower erosion rates and higher total N stocks than croplands, a pattern attributed to specific characteristics of surface cover and understory biomass governed by forest type or crop species. The generally higher risk of N transport and loss in sloping croplands is attributed not only to intensified runoff and sediment generation driven by tillage practices but also to excessive nitrogen applications and suboptimal irrigation strategies[5,37]. During periods of high water input from irrigation or precipitation, the overapplication of nitrogen fertilizers beyond crop uptake capacity can lead to substantial N losses via surface and subsurface flow pathways[38].

-

Soil nitrogen exists in multiple chemical forms, and biological processes mediate its dynamic interconversion. Following the fixation of atmospheric dinitrogen (N2) into organic compounds that enter the soil biota, a series of nitrogen transformations occur[2,3]. These processes primarily include: the mineralization of organic nitrogen into inorganic forms; the immobilization of inorganic nitrogen by microbes and other soil organisms; the nitrification of ammonium into more mobile, plant-available forms that are also prone to loss; and the denitrification of nitrate back into atmospheric gases[2,3,39]. These interconnected processes often proceed concurrently, with specific environmental conditions such as soil properties and climate governing which pathway predominates. Of particular significance is the synergistic regulation between mineralization-immobilization turnover and nitrification, which dynamically controls the availability of inorganic nitrogen in soil, thereby dictating the ultimate magnitude of nitrogen loss via denitrification[40].

Similar to its effect on nitrogen stocks, soil erosion significantly influences gross nitrogen transformation processes within soil profiles[2,17,23,41]. However, the impact of erosion on nitrogen transformation rates remains controversial, with studies reporting increases, decreases, or no significant change[12]. These discrepancies among research findings are likely attributable to variations in soil type (e.g., acidic or alkaline soils), erosion intensity (e.g., weak or strong), and methodology (e.g., field in-situ observations or indoor simulations) across studies. For instance, Shi et al.[23] and Wang et al.[42] conducted research in the same Mollisols region but with different sampling slopes and erosion rates, yet they reported opposing effects of erosion on the spatial redistribution, bioavailability, and transformation of soil nitrogen. Compared to non-eroding and depositional sites, Shi et al.[23] observed increased N immobilization alongside reduced net N mineralization and soil N bioavailability at eroding sites. In contrast, Wang et al.[42] reported increased N mineralization and bioavailability, attributing this to significantly higher nitrification levels. These contrasting findings are primarily explained by differences in soil carbon-to-nitrogen (C:N) ratios and physicochemical protection resulting from varying erosion rates. Furthermore, in an indoor simulation where erosion levels were mimicked by mixing topsoil with varying proportions of subsoil, Schoof et al.[17], using 15N tracing techniques, found that erosion-induced topsoil dilution significantly reduced gross nitrogen transformation rates, primarily ammonium (NH4+) oxidation and organic nitrogen (Norg) mineralization. This reduction was attributed to decreased soil organic C and total N substrates, with the magnitude of the decline increasing significantly with higher erosion levels. As discussed, the controversial effects of erosion on N transformations are likely attributable primarily to variations in substrate quantity, quality, and availability, specifically C and N compounds and their ratios. These variations, which are strongly influenced by differences in soil types, properties, and erosional conditions across studies, in turn regulate microbial activity[17,23,41−43]. However, data on the influence of erosion on nitrogen transformations remain limited. It is therefore necessary to identify general response patterns as the number of studies increases.

The regulatory mechanisms by which soil erosion influences nitrogen transformations are primarily driven by its direct effects on soil physical and chemical properties, such as texture, aggregation, pH, and nutrient dynamics[41]. Soil aggregates function as natural containers for nutrients, with their stability directly determining the physical protection of soil nitrogen. Erosion disrupts surface soil aggregates, leading to the redistribution of nitrogen fractions, weakening physical stabilization, and regulating key transformation processes such as mineralization, nitrification, and denitrification[10,28,42]. Soil texture governs particle aggregation and nutrient turnover, thereby indirectly influencing nitrogen transformation pathways and rates[41]. Texture and aggregation also regulate soil hydrothermal conditions by affecting water infiltration and retention, which are key determinants of whether nitrification or denitrification dominates[44]. Erosion frequently alters soil pH, often inducing acidification through the loss of fine particles and the generation of organic acids, thereby influencing microbial activities and associated nitrogen transformations[19,43,45]. Furthermore, erosion and deposition processes alter the sources and distribution of soil carbon and nitrogen, which affects microbial metabolic activity and nutrient-use efficiency, consequently regulating nitrogen transformation pathways[2,18,21]. As different nitrogen transformations typically occur simultaneously, changes in soil properties during erosion and deposition affect multiple processes concurrently. For example, the reductions in organic C and total N contents and their ratios due to topsoil erosion can significantly affect the mineralization of soil organic nitrogen, thereby regulating the efficiency of autotrophic nitrification of ammonium to nitrate[17,42]. Moreover, erosion-induced soil acidification may inhibit nitrification, reducing nitrate production and indirectly affecting denitrification.

Soil microorganisms are the primary drivers of nitrogen transformations, participating in and regulating every reaction in the nitrogen cycle[2,3,46]. Soil erosion significantly alters soil physicochemical properties and microhabitat conditions, exerting substantial negative impacts on microbial community composition, diversity, and network complexity[43,44,47,48]. Research has established that soil edaphic properties, particularly the composition and diversity of microbial communities, significantly influence multiple ecosystem functions (i.e., multifunctionality), thereby profoundly affecting nutrient cycling processes such as nitrogen transformation[43,49,50]. For instance, along an agricultural slope in the Mollisol region of Northeastern China, Yang et al.[48] observed that erosion fragments and transports soil aggregates, altering properties like soil organic carbon and aggregate water stability. These changes affect microbial activity, thereby altering soil multifunctionality. Similarly, Qiu et al.[43] demonstrated that erosion deteriorates soil structure and depletes available substrates and nutrients, significantly reducing soil bacterial diversity and multifunctionality. Quantification of functional genes serves as a molecular marker for assessing the abundance of microbial communities involved in nitrogen transformation pathways. Key genes include nifH for nitrogen fixation, amoA for nitrification (with archaeal-amoA for ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacterial-amoA for ammonia-oxidizing bacteria), and nirK and nirS for denitrification[46,51]. Qiu et al.[43] found that erosion increased the relative abundance of certain bacterial families involved in nitrogen cycling, such as Acetobacteraceae and Beijerinckiaceae, which are associated with nitrogen fixation as indicated by nifH genes. Furthermore, studies by Schoof et al.[17] and Qiu et al.[41] hypothesized that reduced nitrogen mineralization under simulated erosion conditions might be linked to changes in microbial activity and diversity. However, the quantitative relationship between erosion-induced shifts in microbial community structure and variations in nitrogen transformation rates remains poorly studied and warrants greater attention in future research.

-

Soil erosion is a critical driver of biogeochemical cycling in terrestrial ecosystems, and scientists have increasingly focused on understanding these interactions globally in recent decades[10,12,13,18]. However, compared to the extensive research on carbon cycling in erosional landscapes, the influence of erosion on nitrogen cycling remains inadequately studied[10,11]. Existing research has primarily assessed erosion-induced changes in soil nitrogen redistribution, transport, and stocks, while knowledge regarding how erosion and deposition impact nitrogen transformation processes remains limited. More studies should focus on quantifying soil erosion's role in nitrogen cycling, particularly by investigating the spatial variation in eroded nitrogen and elucidating the underlying microbial mechanisms.

Soil nitrogen cycling in erosional landscapes is influenced by multiple factors, as discussed above, many of which exhibit substantial variation across spatial scales. This variability likely generates spatial heterogeneity in nitrogen redistribution, transport, and storage patterns during erosion-deposition processes. While previous research has primarily concentrated on hillslope and catchment scales, the interactions between erosion and nitrogen cycling may demonstrate emergent properties at broader watershed and regional scales. Extensive research and significant progress have been made in soil erosion monitoring methods, including in-situ monitoring, model estimation, and remote sensing technology. These methods are applied across a range of spatial scales, from points and plots to slopes, watersheds, and entire regions[52]. Substantial progress has also been made over the last decade in elucidating the nitrogen (N) cycle across multiple dimensions, including the use of in-situ or laboratory isotopic tracing to separate gross N transformations and the development of cross-scale N cycling models[53]. Future research should prioritize integrating cross-scale methods to study soil erosion and nitrogen cycling, addressing the multiscale complexities of how erosion influences soil nitrogen transport and stocks.

Previous studies have demonstrated that soil erosion influences biogeochemical nitrogen cycling primarily through physical, chemical, and biological pathways. However, the microbial mechanisms governing nitrogen transformation during erosion-deposition processes remain poorly understood. As discussed above, further investigation is required to elucidate how erosion modifies the structure of soil microbial communities, including denitrifying bacteria, ammonia-oxidizing bacteria, and archaea with their functional gene expression, consequently regulating key nitrogen cycling processes.

The interaction between soil erosion and nitrogen cycling is closely linked to the cycling of other elements, particularly carbon and phosphorus. As multiple stressors such as climate change, nitrogen deposition, and land-use change intensify, soil erosion intensity, carbon-nitrogen coupling, and other elemental cycling pathways are likely to undergo significant changes. Future research should prioritize investigating the feedback mechanisms between erosion and nitrogen cycling across diverse environmental scenarios, as this understanding is essential for developing adaptive management strategies to mitigate potential increases in greenhouse gas emissions.

-

Soil erosion exerts a significant influence on soil processes, particularly nutrient dynamics, which are critical drivers of terrestrial biogeochemical cycles. As a key component of these cycles, soil nitrogen cycling determines the nitrogen supply available for plant productivity and is strongly affected by soil erosion. This review synthesizes current research on the effects of soil erosion on nitrogen transport, stocks, major transformation processes, and the underlying mechanisms. In contrast to the well-documented understanding of soil carbon dynamics, the impacts of erosion on soil nitrogen cycles have received less attention and remain insufficiently characterized. Additional research is required to elucidate spatiotemporal variations in nitrogen transport and bioavailability during erosion and deposition processes at multiple scales. The mechanisms involved, particularly the microbial pathways by which soil erosion influences nitrogen transformation, also warrant further investigation. This review enhances understanding of the role of soil erosion in nitrogen cycling and offers insights relevant to terrestrial biogeochemical processes.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Minghua Zhou performed study conception and design, contributed to revising the initial draft. Baojun Zhang performed material preparation, literature collection, and analysis, wrote the draft manuscript. Both authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2023YFD1901201), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42107377), and the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. 2022380).

-

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

-

A review of soil erosion's role in the biogeochemical nitrogen cycle is presented.

Less is known about the influence of soil erosion on nitrogen cycling than on carbon dynamics.

Soil erosion significantly affects nitrogen pools, redistributes nitrogen, and transforms it across eroding landscapes.

The cross-scale impact of soil erosion on nitrogen cycles is an important direction for future research.

The microbial mechanism by which soil erosion influences nitrogen transformation processes should be clarified.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang B, Zhou M. 2026. Role of soil erosion in biogeochemical nitrogen cycles: a mini review. Nitrogen Cycling 2: e012 doi: 10.48130/nc-0025-0024

Role of soil erosion in biogeochemical nitrogen cycles: a mini review

- Received: 05 November 2025

- Revised: 16 December 2025

- Accepted: 30 December 2025

- Published online: 28 January 2026

Abstract: Soils function as the primary terrestrial reservoirs of essential nutrients, including carbon and nitrogen. The transport and redistribution of soil particles through erosion significantly modify soil properties and nutrient dynamics, thereby profoundly influencing terrestrial biogeochemical processes. Despite substantial advancements in understanding the role of erosion in biogeochemical cycles, the specific effects of erosion on nitrogen cycling across erosional landscapes remain insufficiently characterized. This review synthesizes current knowledge on the impact of soil erosion on nitrogen cycles, with particular emphasis on nitrogen pools, transformation and transport processes, and the underlying mechanisms. Erosion-induced redistribution generally decreases nitrogen stocks in eroding zones and increases accumulation in depositional areas; however, the magnitude and composition of redistributed nitrogen depend on specific erosional conditions. Erosion alters soil physicochemical properties by disrupting aggregates and sorting particles, which negatively affects microbial communities and soil multifunctionality. These changes regulate nitrogen transformation processes, such as mineralization and immobilization. Although most research has focused on hillslope and catchment scales, future investigations should address watershed and regional scales by employing cross-scale approaches, such as integrating regional soil erosion and nitrogen models. Further studies are required to clarify the mechanisms by which erosion influences nitrogen transformation, particularly those involving microbial processes. This review offers insights into the role of soil erosion in biogeochemical nitrogen processes within terrestrial ecosystems.