-

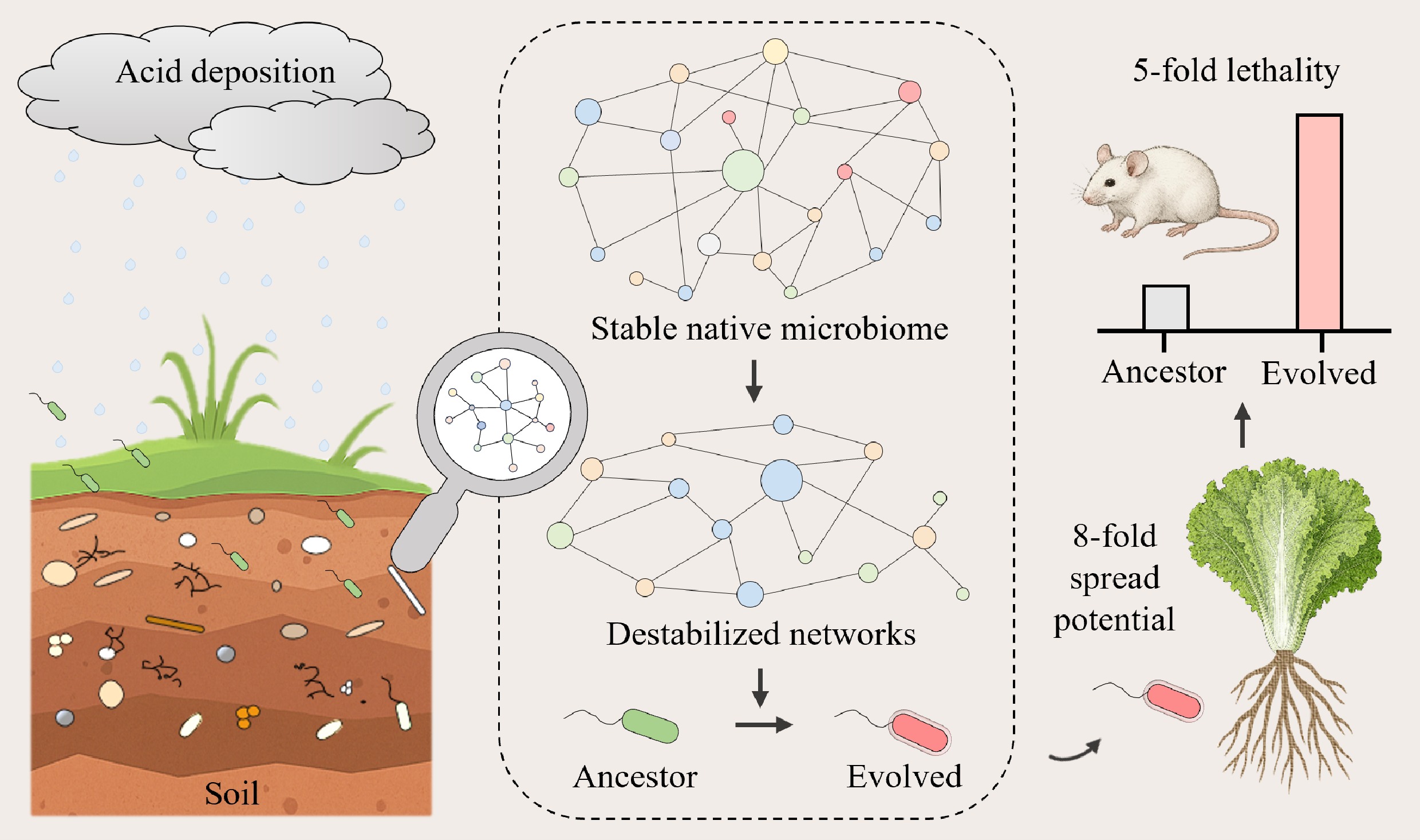

Human activities are reshaping the global environment at an unprecedented rate, creating novel selective pressures that can alter the ecology and evolution of pathogenic microbes[1]. A critical challenge is to understand how anthropogenic stressors impact the environmental reservoirs of pathogens, as these ecosystems can act as both crucibles for evolution and springboards for transmission[2−5]. While it is known that environmental change can influence disease dynamics[1,5−7], the interplay between ecological opportunity and rapid pathogen evolution forms an eco-evolutionary feedback loop, a mechanism that remains poorly understood yet could amplify public health risks.

Acid deposition, a pervasive consequence of fossil fuel combustion, represents a powerful anthropogenic stressor on terrestrial ecosystems[8,9]. Its primary effect, soil acidification, is fundamentally hostile to most bacteria, including enteric pathogens, by directly impairing cellular functions[10−13]. However, ecosystems are not simply collections of individuals responding to stress; they are complex networks of interacting species. Environmental disturbances can destabilize these networks, weakening the collective invasion resistance that native communities normally provide[14,15]. This raises a critical and paradoxical question of whether a broadly detrimental stressor like acid rain can create an ecological opportunity for an invading pathogen by disproportionately harming its native competitors, and subsequently, whether this new ecological niche can fuel the pathogen's rapid adaptive evolution.

Addressing this question is particularly urgent for soil-borne zoonotic pathogens, which pose significant public threats[16]. E. coli O157:H7, a major pathogen contributing to the global burden of foodborne disease[17], serves as an ideal model. The widespread use of livestock manure as fertilizer provides a primary route for its entry into agricultural soils[18], directly threatening the safety of the food chain[19]. While its persistence in soil is known to depend on a suite of physicochemical properties, including mineralogy, water content, and organic matter[20−23], how it navigates the dual challenges of abiotic stress and biotic resistance from the native microbiome is not well understood.

In this study, the hypothesis that acid rain initiates a positive eco-evolutionary feedback loop that enhances the environmental persistence and virulence of E. coli O157:H7 was investigated. First, global soil metagenomic data were analyzed to confirm that soil pH is a key environmental factor shaping E. coli abundance, establishing the macroecological context of this study. Subsequently, using a 150-d soil microcosm experiment, community ecology, phenomics, genomics, and infection models were combined to dissect this process. It is demonstrated that acid rain promotes pathogen survival not by benefiting it directly, but by disrupting the indigenous microbial network and reducing biotic resistance. It is then shown that this ecological scaffolding enables the rapid evolution of E. coli O157:H7, selecting for lineages with optimized colonization traits, enhanced transmissibility to plants, and dramatically increased virulence in a mammalian host. The present findings reveal a mechanistic pathway through which industrial pollution can inadvertently drive the evolution of more dangerous pathogens, highlighting the urgent need to consider eco-evolutionary dynamics in environmental health risk assessments.

-

Topsoil samples (0–20 cm) were collected from a natural forest in Fengqiu County, Henan Province, China (35°2'8" N; 114°33'4" E). In the laboratory, the soil was homogenized and sieved (2 mm mesh) to remove plant debris and stones, then stored at 4 °C until use.

Simulated acid rain solutions (pH 6.5, 4.5, and 2.5) were prepared by diluting a stock solution of H2SO4 and HNO3 (3:1, v/v) with deionized water. These levels were selected to represent a gradient from a non-acidic control (pH 6.5) to an environmentally relevant acid rain scenario (pH 4.5)[24] and an extreme stress condition (pH 2.5) to assess the pathogen's physiological limits and evolutionary response. E. coli O157:H7 was cultured in LB medium at 37 °C to the logarithmic phase, harvested by centrifugation (4,000 × g, 10 min), washed, and resuspended in normal saline. Twenty-four soil microcosms were established in 1-L wide-mouth bottles, each containing 500 g of soil. Twelve bottles served as controls (amended with normal saline), while the other twelve were inoculated with the E. coli O157:H7 suspension to an initial concentration of 107 CFU/g soil. All microcosms were incubated in a greenhouse with the lids off to allow evaporation. After one week, 30 mL of the corresponding simulated acid rain was added weekly to each treatment group. Soil samples were collected on days 15, 30, 60, 90, and 150 for pathogen quantification, DNA extraction, and analysis of soil physico-chemical properties and microbial metabolic activity.

Determination of soil physico-chemical properties

-

Soil pH was measured in a 1:2.5 soil-to-water suspension using a PB-10 pH meter (Sartorius, Germany). Soil organic carbon (SOC) was quantified by the potassium dichromate volumetric method. Total carbon (TC), and total nitrogen (TN) were analyzed using a Vario PYRO cube elemental analyzer (Elementar, Germany).

Quantification of E. coli O157:H7

-

The abundance of E. coli O157:H7 was determined by both plate counting and qPCR. Plate counting was performed on Sorbitol MacConkey Agar, a selective medium specifically designed for the detection of E. coli O157:H7[25], using serial dilutions of soil, fecal, and lettuce samples. Colonies were confirmed as E. coli O157:H7 by 16S rRNA gene sequencing (primers 27F/1492R).

qPCR targeted the rfbE gene, specific to E. coli O157:H7[26]. Reactions were performed on a QuantStudio 3 system (ABI, USA) using ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme, China), and specific primers (rfbE-F/R). The thermal program consisted of an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, and 60 °C for 30 s, and a subsequent melting curve analysis. Pathogen abundance was calculated from a standard curve.

Soil DNA extraction and 16S rRNA gene sequencing

-

Total DNA was extracted from 0.25 g of fresh soil using the PowerSoil DNA Extraction Kit (MoBio, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions. The V3−V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using primers 338F/806R and sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq platform at Guangdong Magigene Biotechnology Co., Ltd.

Sequence data were processed using QIIME 2 (2022.11)[27]. Taxonomy was assigned to Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) against the SILVA 138 database using the classify-sklearn naïve Bayes classifier[28]. Alpha diversity was calculated from the ASV table. Beta diversity was assessed using Bray-Curtis distances and visualized via principal coordinate analysis. Co-occurrence networks were constructed based on SparCC analysis and visualized using the R packages igraph and ggraph.

Determination of microbial metabolic activity

-

Soil microbial suspensions (1:1,000 dilution) were inoculated into Biolog ECO microplates (BIOLOG, USA) and incubated at 25 °C. Absorbance at OD590 was measured daily with a multimode microplate reader (Tecan, Switzerland). Microbial metabolic activity (S) was calculated as the area under the Average Well Color Development curve, using the following formula:

$ AWCD=\sum _{i=1}^{n}({C}_{i}-r)/n $ $ S=\sum \left(\dfrac{{v}_{j}+{v}_{j-1}}{2}\times ({t}_{j}-{t}_{j-1})\right) $ where, C: OD590 value of the carbon source; r: OD590 value of blank control; n: the number of carbon sources involved; vj: the AWCD at time t = tj.

Phenotypic assays of evolved strains

-

Ancestral and evolved strains were cultured in LB medium to mid-log phase (OD600 ≈ 0.5–0.7) for all assays. Growth curves were generated by monitoring OD600 in a 96-well plate. Biofilm formation was quantified using the crystal violet staining method[29]. Motility was assessed on soft-agar plates (0.28% agar) by measuring the diameter of the swarm colony after 36 h at 28 °C[30]. Cellulose degradation was observed on LB plates containing Congo red (40 μg/mL).

Determination of gene transcript levels

-

Total RNA was extracted from mid-log phase cultures using the miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany), and reverse transcribed with the HiScript IV RT SuperMix for qPCR kit (Vazyme, China). Relative transcript levels of target genes (primers in Supplementary Table S1) were determined by qPCR using the comparative CT method, with the 16S rRNA gene as the internal control.

Whole genome sequencing and mutation detection

-

Whole-genome sequencing was performed on both Illumina NovaSeq and Oxford Nanopore ONT platforms at Shanghai Personal Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Genomes were assembled with CANU[31], corrected with Pilon[32], and annotated using KAAS[33] and Prokka[34]. Illumina reads were mapped to the reference genome using bwa mem[35]. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were identified with GATK[36] and Snippy. Results were visualized with BRIG[37] and Easyfig[38].

Soil microcosm and pot experiments with evolved E. coli O157:H7

-

Mid-log phase cultures of ancestral and evolved strains were inoculated into 50 g of soil at an initial concentration of 107 CFU/g soil and incubated at 28 °C. Pathogen abundance was quantified on days 7, 15, 20, 28, and 60.

One hundred sixty-eight lettuce plants were divided into seven groups (n = 24): a control, an ancestral strain group, and five evolved strain groups. Plants were inoculated by applying 5 mL of bacterial suspension (107 CFU/mL) to leaves and roots. Samples (roots, leaves, rhizosphere soil) were collected on days 7, 15, 20, 28, and 60.

Murine model of infection

-

All animal experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of Huazhong Agricultural University (HZAUMO-2024-0249) and conducted in a biosafety level 2 facility. Four- to five-week-old BALB/C mice were divided into seven groups (n = 10 per group, equal sex ratio). Prior to infection, mice were fasted for 24 h and given drinking water supplemented with 5 g/L streptomycin. Mice were orally gavaged with 0.3 mL of bacterial suspension (109 CFU/mL in PBS). Body weights were recorded daily, and fecal pellets were collected on days 1, 3, 5, and 8 for pathogen quantification.

Mouse dissection and intestinal histology

-

At the end of the experiment or upon death, mice were euthanized and dissected. Intestinal segments were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, processed through a TP1020 automatic dehydrator (Leica, Germany), and embedded in paraffin using an EG1150H embedding station (Leica, Germany). Four-micrometer sections were cut using an RM2235 rotary microtome (Leica, Germany), stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and examined under a Nikon 80i biological optical microscope (Nikon, Japan).

Statistical analyses

-

The global distribution analysis of soil E. coli utilized a dataset of 2,874 soil metagenomic samples from previous studies[39,40]. All experiments were performed with at least four replicates, and data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunn's post-hoc test was used to determine significant differences (p ≤ 0.05). Differences in alpha diversity were assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's post-hoc test (* ≤ 0.05, ** ≤ 0.01).

-

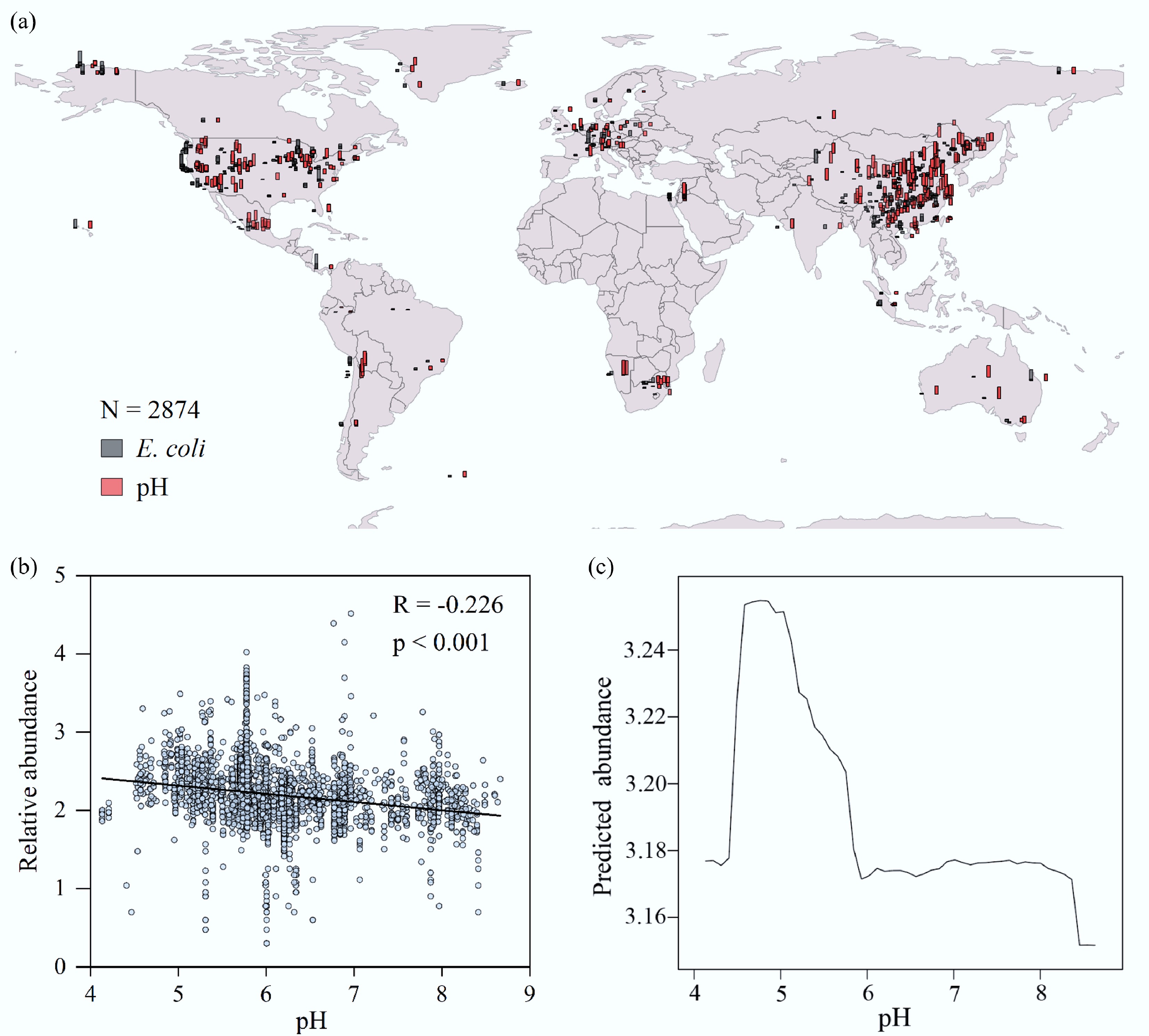

To investigate the key environmental factors driving the soil colonization of E. coli on a macroscopic scale, a soil metagenomic dataset comprising 2,874 geographical samples from around the globe were analyzed. The results showed that across these soils, with a pH range of 4.1 to 8.7, E. coli demonstrated a striking prevalence, being detected in up to 99.99% of the samples (Fig. 1a). Further analysis revealed that soil pH is a key ecological factor influencing its abundance. A linear regression analysis indicated that the relative abundance of E. coli exhibited a significant negative correlation with soil pH overall (Fig. 1b). However, this relationship was not a simple linear decrease. A Partial Dependence Plot analysis further unveiled a more complex, non-linear pattern: the abundance of E. coli peaked in a weakly acidic environment (pH ≈ 5.0), then stabilized as the pH rose above approximately 6.0, and began to decline significantly again as the pH approached 8.0 (Fig. 1c). This global-scale evidence strongly suggests that soil acidification is a key environmental pressure affecting the ecological fitness of E. coli. It thus provides a clear theoretical basis and a precise starting point for our subsequent microcosm experiments using simulated acid rain to delve into its micro-ecological and evolutionary mechanisms.

Figure 1.

The relationship between soil pH and E. coli abundance on a global scale. (a) Geographical distribution of the relative abundance of E. coli and pH levels in global soil samples. Data were normalized for visualization. (b) Linear regression analysis of the relationship between the relative abundance of E. coli and soil pH. (c) The non-linear relationship between the relative abundance of E. coli and soil pH as revealed by a Partial Dependence Plot (PDP).

Environmental stress promotes pathogen invasion and survival by reshaping microbial interaction networks

-

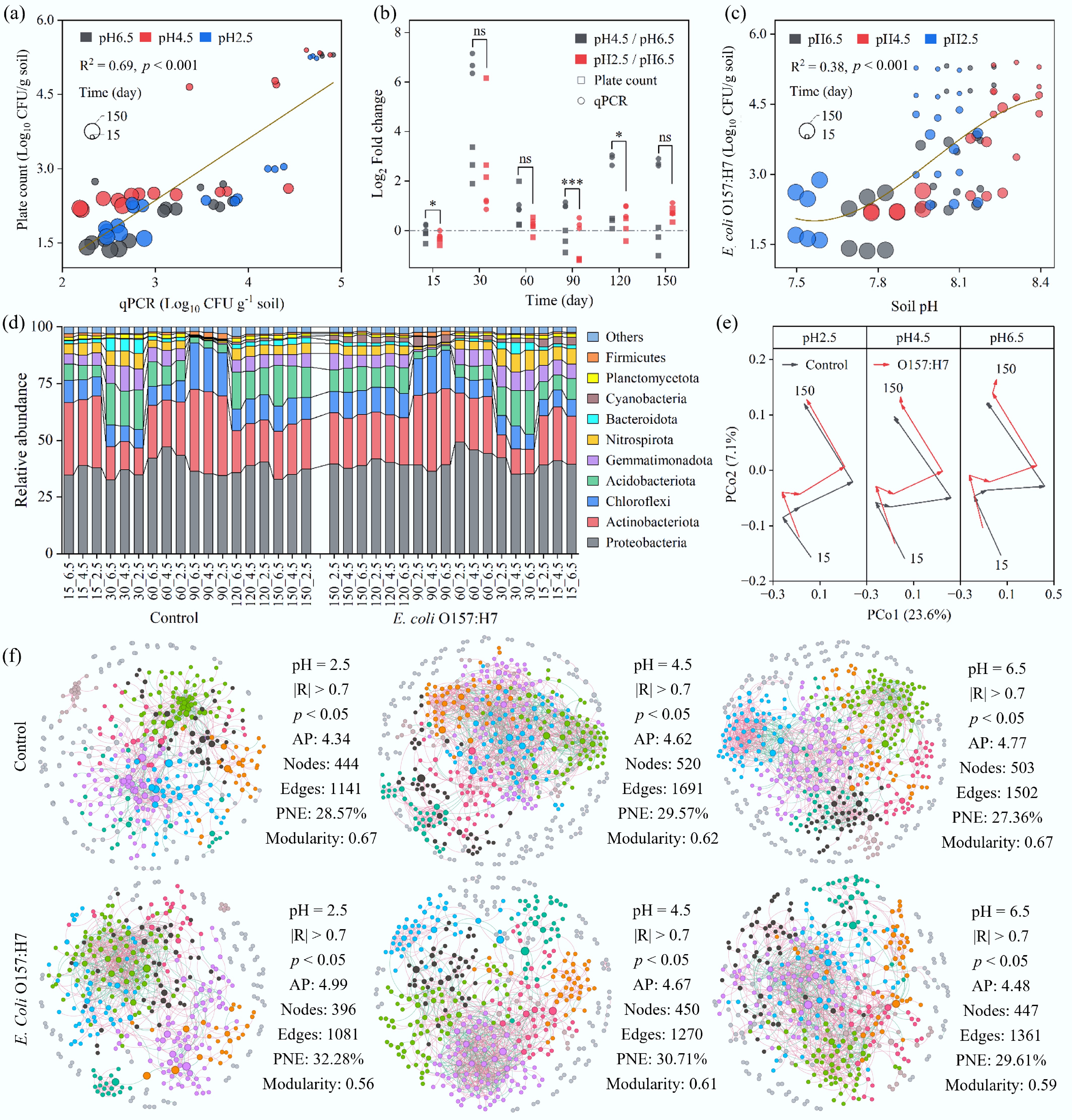

Simulated acid rain treatments (pH 6.5, 4.5, 2.5) significantly decreased soil pH but had minimal impact on soil organic and total carbon, while increasing total nitrogen content in the later stages of the experiment (Supplementary Fig. S1). Although the abundance of E. coli O157:H7 declined over time in all treatment groups, acid rain stress significantly slowed its decay rate. It should be noted that E. coli O157:H7 was not detected in the un-inoculated control groups throughout the experiment. Combined monitoring by qPCR and plate counting (R2 = 0.69) revealed that under normal rain conditions, the abundance of E. coli O157:H7 decreased most rapidly (Fig. 2a), dropping from ~2.0 × 105 CFU/g to 487 CFU/g between day 15 and day 30, and reaching 24 CFU/g by day 150 (Supplementary Fig. S2a, c). In contrast, acid rain treatments markedly slowed this decline. At the end of the experiment (day 150), the pathogen abundance under mild and strong acid rain was 163 CFU/g and 43 CFU/g, respectively, nearly 7-fold and 2-fold higher than that in the normal rain group.

Figure 2.

Effects of acid deposition and E. coli O157:H7 invasion on the soil microbial community. (a) Abundance of E. coli O157:H7, determined by plate counting on Sorbitol MacConkey agar and by qPCR targeting the rfbE antigen. (b) Fold change in E. coli O157:H7 abundance under simulated acid rain treatments (mild: pH = 4.5; severe: pH = 2.5) relative to normal rainfall conditions (pH = 6.5). Paired t-tests were performed; * and *** indicate p < 0.05 and p < 0.001, respectively. (c) Trend of E. coli O157:H7 abundance as a function of soil pH. (d) Relative abundances of the top 10 most abundant phyla in the soil. (e) Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) based on Bray-Curtis distances. (f) Overview of soil microbial co-occurrence networks under different rainfall treatments, with or without E. coli O157:H7 invasion. AP: Average Path Length; PNE: Proportion of Negative Edges.

This facilitative effect was particularly pronounced under mild acid rain during the mid-phase of the experiment (day 30), where its abundance was up to 100-fold higher than that of the normal rain group (Fig. 2b; Supplementary Fig. S2b, d). Besides, the fitted curve in Fig. 2c reveals the pathogen's non-linear response to pH; as the pH dropped below 7.8, its rate of decline slowed, suggesting a potential tolerance to acid stress.

To investigate the underlying microbial mechanisms, the response of the soil bacterial community was further analyzed. Notably, while targeted qPCR confirmed the persistence of E. coli O157:H7, its low relative abundance fell below the detection limit of 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing, which did not detect Enterobacteriaceae. Therefore, the subsequent community analysis primarily reveals the response of the indigenous microbiota to the invasion. It was found that the macroscopic composition (at the phylum level) of the native bacterial community exhibited high stability against pathogen invasion. Inoculation with exogenous E. coli O157:H7 did not cause significant shifts in community composition; the primary drivers of community structure were the environmental filtering effect of strong acid rain (pH 2.5) itself (e.g., significantly inhibiting Proteobacteria and promoting Acidobacteriota), and temporal succession (Fig. 2d). Principal Coordinate Analysis and alpha diversity analysis also confirmed that all samples clustered primarily by sampling time (early, middle, and late stages) rather than by acid rain pH or pathogen invasion treatment (Fig. 2e; Supplementary Fig. S3). Furthermore, community diversity showed a trend of resilience after a transient fluctuation. This suggests that the enhanced survival of E. coli O157:H7 did not stem from a major disruption of the overall species composition of the native community. Additionally, under the dual stress of acid rain and pathogen invasion, the stimulating effect of acid rain on microbial metabolism was dominant, leading to an increase in total microbial metabolic activity as acidity increased (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Despite the stability of the macroscopic community composition, the microscopic ecological network of species interactions underwent profound restructuring. Co-occurrence network analysis revealed that pathogen invasion simplified the microbial network structure, reducing the number of nodes and edges, an effect exacerbated by acid rain stress (Fig. 2f). Under the combined pressure of strong acid rain and pathogen invasion, the numbers of network nodes (396) and edges (1,081) dropped to the lowest levels. Network stability was also severely compromised, reflected by a significant decrease in modularity (invaded group 0.563 vs control 0.667). Crucially, the proportion of negative correlations within the network systematically increased in all invaded groups, peaking in the strong acid rain-invaded group (32.28%), which was significantly higher than its control (28.57%). This suggests that acid rain weakened the overall invasion resistance of the native community by intensifying internal competition, creating an ecological opportunity for the persistent survival of E. coli O157:H7.

Pathogen enhances its ecological competitiveness through phenotypic optimization

-

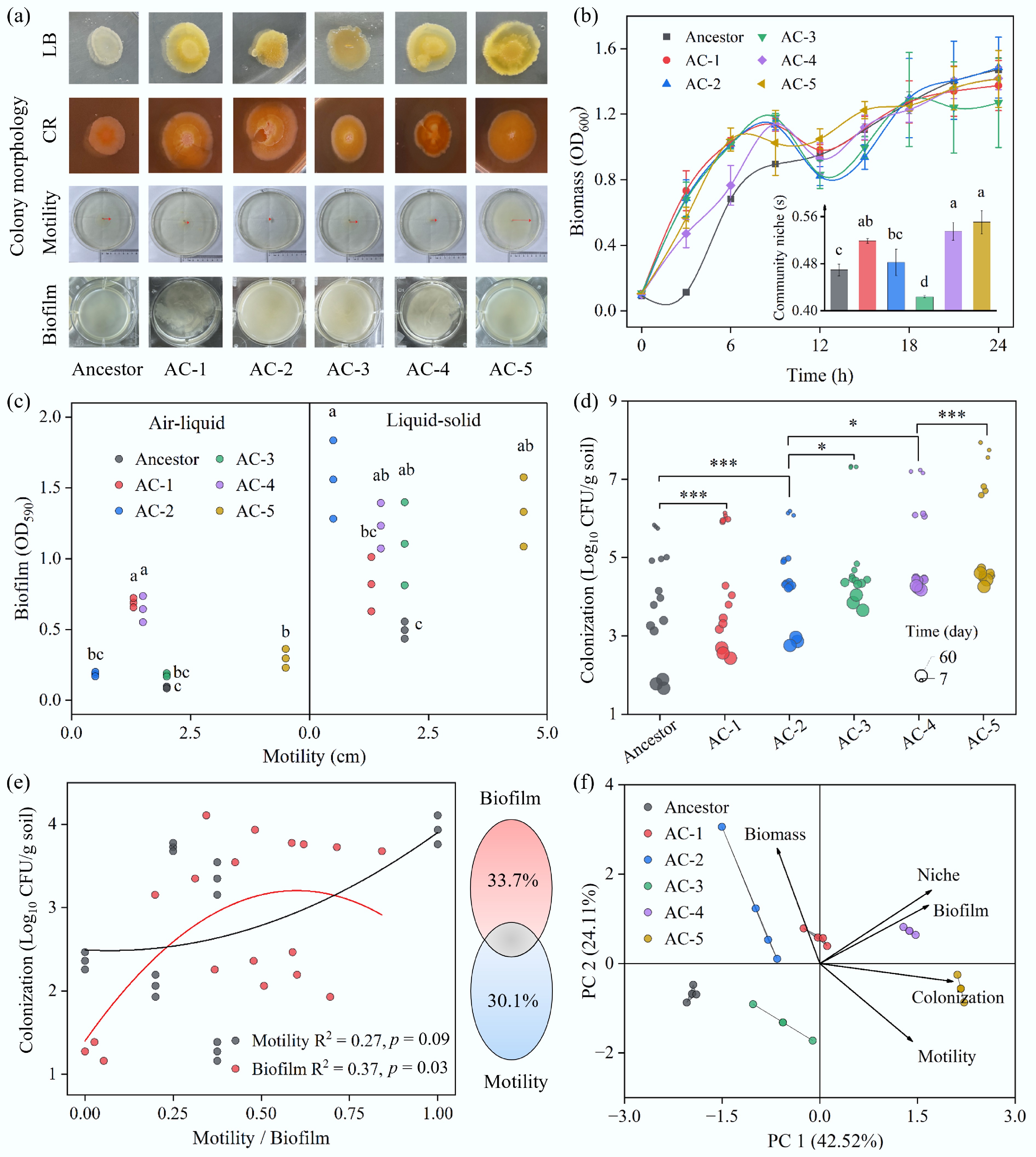

After 150 d of incubation under mild acid rain (pH 4.5) treatment, E. coli O157:H7 colonies isolated from multiple, independent soil microcosms consistently exhibited significant morphological variations. To investigate this adaptive evolution, we selected five representative strains (AC-1 to AC-5), each originating from a different biological replicate, for in-depth analysis.

Compared to the ancestor, these evolved strains displayed a unique orange-yellow color and serrated edges on LB agar plates and showed larger transparent halos on Congo red agar, indicating enhanced cellulose metabolism and biofilm-forming potential (Fig. 3a). Furthermore, while their final planktonic biomass was similar to the ancestor's, the evolved strains exhibited a markedly shorter lag phase, initiating logarithmic growth almost immediately. This suggests enhanced environmental fitness and a greater readiness for growth rather than an increase in resource utilization efficiency. Concurrently, they demonstrated altered metabolic flexibility in their carbon source utilization profiles (Fig. 3b). Phenomic analysis revealed significant divergence in two key functional traits: all evolved strains showed generally enhanced biofilm formation, capable of forming thicker submerged and pellicle biofilms than the ancestor. In contrast, motility followed diverse evolutionary trajectories, with some lineages (AC-1, AC-2, AC-4) showing decreased motility, while AC-5 became significantly more motile (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3.

Physiological and colonization differences between the ancestral and evolved strains. (a) Morphologies of the strains on LB agar, Congo Red agar, and soft agar (swimming) plates, and in LB broth. (b) Growth curves in LB broth and niche breadth of the strains. Niche breadth was calculated using Biolog ECO plates. Different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05. (c) Relationship between motility and the formation of submerged (liquid–solid interface) and pellicle (air–liquid interface) biofilms. Different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05. (d) Colonization abundance of the strains in soil over time. Paired two-tailed t-tests were performed; * and *** indicate p < 0.05 and p < 0.001, respectively. (e) Impact of biofilm formation and motility on soil colonization. Data for biofilm and motility were normalized. Colonization data from day 60 were used for the Variation Partitioning Analysis (VPA). (f) Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of strain characteristics.

To verify whether these evolved traits translated into an ecological advantage, a soil microcosm re-inoculation experiment was conducted. The results showed that the soil colonization ability of the evolved strains far surpassed that of their ancestor. After 60 d of incubation, the cell abundance of the evolved strains was 6- to 450-fold higher than that of the ancestor (Fig. 3d). This clearly demonstrates that the rapid evolution under acid rain pressure significantly enhanced the pathogen's long-term survival in this environment. Further analysis revealed that this ecological success stemmed from a complex strategy of trait trade-offs and optimization, rather than the maximization of a single trait. A correlation analysis showed a significant quadratic, non-linear relationship between biofilm formation and soil colonization (Fig. 3e), where colonization efficiency peaked at an intermediate level of biofilm formation; excessively strong (e.g., AC-4) or weak biofilm was suboptimal. In contrast, motility showed only a weak positive correlation with colonization. However, a variance partitioning analysis confirmed that biofilm formation and motility were two nearly equally important factors explaining the variation in colonization ability, independently contributing 33.7% and 30.1% of the variance, respectively.

Principal component analysis visually depicted the evolutionary landscape, showing different lineages diverging from a common ancestor along distinct adaptive paths (Fig. 3f). For example, the most successful colonizer, lineage AC-5, achieved optimal fitness through a combined strategy of significantly enhanced motility and moderately strong biofilm formation. Conversely, lineage AC-4, despite having evolved the strongest biofilm-forming ability, was not the best colonizer, illustrating the principle of survival of the fittest, not the strongest. In conclusion, acid rain acted not only as an ecological disturbance but also as a powerful evolutionary driver. It prompted E. coli O157:H7 to rapidly evolve a suite of new phenotypic strategies. This enhanced biofilm formation and optimized motility not only helped the pathogen withstand the direct chemical stress of acid rain but, more critically, enabled it to more efficiently exploit the ecological niches freed up by the decline of the indigenous community. This constitutes a key component of a positive eco-evolutionary feedback loop: the ecological opportunity promoted the pathogen's survival, the surviving pathogen evolved under selection pressure, and the newly evolved traits, in turn, enhanced its ability to seize that ecological opportunity.

Stress-induced genome remodeling and synergistic enhancement of pathogenicity

-

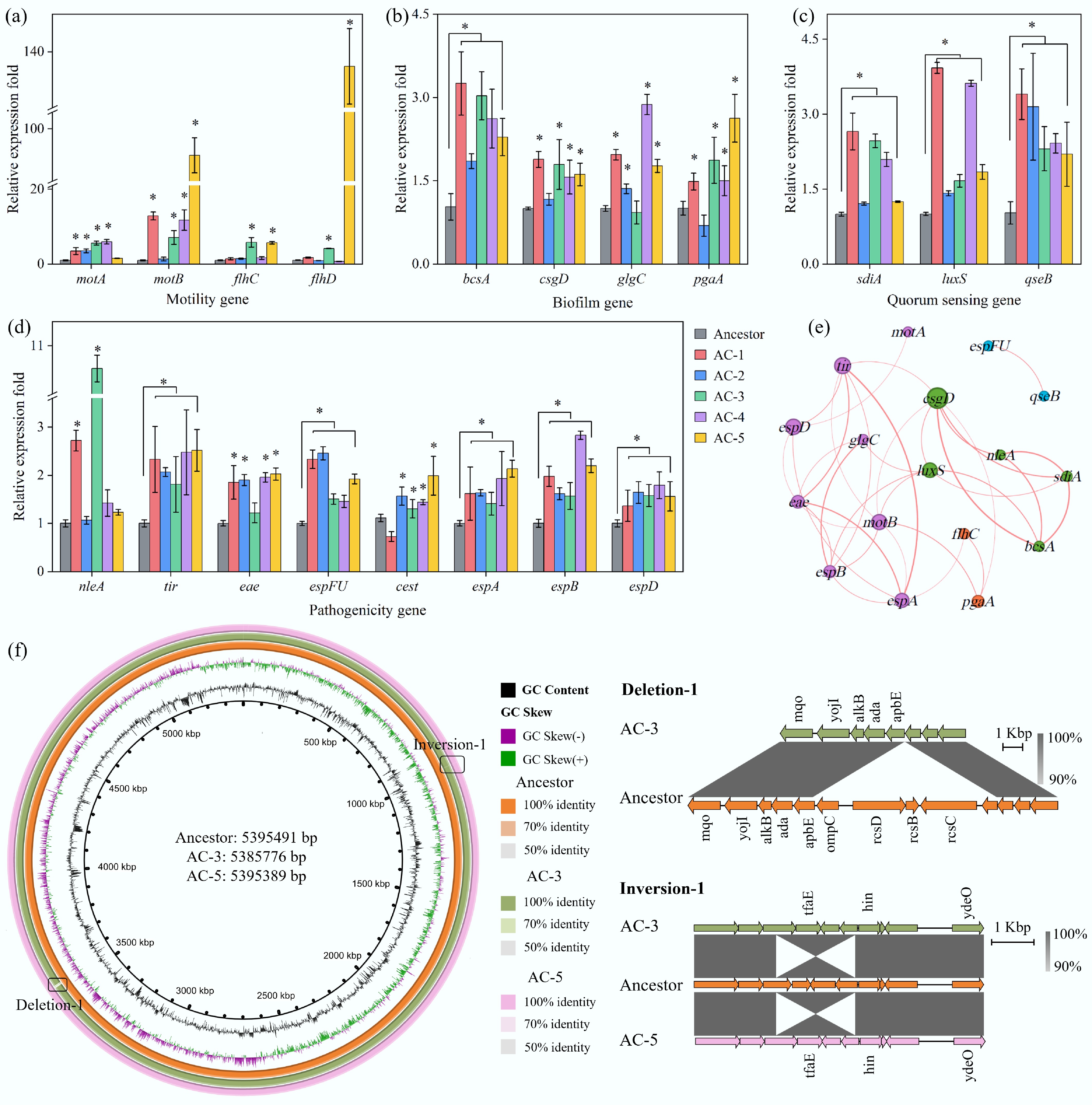

To explore the molecular mechanisms behind the observed phenotypic evolution, we first assessed the expression profiles of key functional genes in the evolved strains via qRT-PCR. The results revealed that the adaptive advantage of the evolved strains originated from a coordinated transcriptional reprogramming of a multi-functional module. Compared to the ancestor, the expression of motility-related genes corresponded precisely with the phenotypes; for instance, in the hyper-motile strain AC-5, the expression of motility regulatory and motor genes (flhC/D, motA/B) was significantly increased (Fig. 4a). Furthermore, genes associated with biofilm formation (e.g., bcsA, csgD), quorum sensing (e.g., luxS, sdiA), and pathogenicity (e.g., genes encoding T3SS effector proteins such as nleA, eae, espA/B/D) were systematically and significantly upregulated across all evolved strains (Fig. 4b−d). A gene expression correlation network further elucidated the logic of this co-regulation: the quorum sensing core gene luxS and the key biofilm regulator csgD occupied central hub positions in the network, showing strong positive correlations with multiple motility and virulence genes (Fig. 4e). This indicates that under acid rain stress, E. coli O157:H7 did not merely modify individual genes, but achieved a systemic upgrade of communication, colonization, and virulence capabilities by activating a regulatory network centered on quorum sensing. This finding provides direct molecular evidence for the enhanced soil colonization of the pathogen and its potential increase in public health risk.

Figure 4.

Genetic differences between the ancestral and evolved strains. (a) Transcriptional changes in motility-related genes. (b) Transcriptional changes in biofilm formation-related genes. (c) Transcriptional changes in quorum sensing-related genes. (d) Transcriptional changes in pathogenicity-related genes. Asterisks indicate a significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) between the evolved E. coli O157:H7 strains and the wild-type. (e) Spearman correlation network of gene expression. Connections with R > 0.7 and p < 0.05 are displayed. (f) Circular genomic maps of the ancestral and evolved E. coli O157:H7 strains AC-3 and AC-5. From the innermost to the outermost circle: the first circle represents the scale; the second, GC skew; the third, GC content; the fourth, fifth, and sixth circles show the sequence alignment results between the ancestral strain, AC-3, and AC-5, respectively. Details of deletions and inversions are shown below the map.

To trace the genetic basis of these transcriptional changes, we performed whole-genome sequencing on the two most successful colonizers, AC-3 and AC-5 (Fig. 4f). The results showed that genetic variations occurred primarily on the chromosome. Although a few single nucleotide polymorphisms were detected in non-coding regions, large-scale structural variations appeared to be the key drivers of rapid evolution. A major finding was a large-scale inversion that occurred at the same chromosomal location in the independently evolved lineages AC-3 and AC-5. This inverted region is adjacent to the DNA invertase gene hin and the known acid tolerance regulator ydeO, suggesting that this structural rearrangement may be a convergent evolutionary event in response to acid stress, optimizing acid adaptation by altering the relative positions of genes or regulatory elements.

Additionally, a critical genomic deletion occurred in strain AC-3, which encompassed the outer membrane porin gene ompC and the entire Rcs phosphorelay system (rcsB, rcsC, rcsD). The Rcs system is a conserved environmental stress-sensing and regulatory hub in bacteria. Under specific pressures, deleting this complex regulatory system may provide an adaptive shortcut, lifting the fine-tuned constraints on downstream genes (such as those for biofilm synthesis) and thereby enabling the enhanced expression of specific functions.

In summary, driven by the environmental pressure of acid rain, the adaptive evolution of E. coli O157:H7 was manifested not only in the synergistic optimization of its gene expression network but was also rooted in profound genomic structural variations, such as inversions and deletions. These genetic-level changes endowed the pathogen with enhanced environmental fitness and pathogenic potential, completing its transformation from an ordinary invader to a highly effective colonizer.

Ecological adaptation drives virulence evolution and cross-kingdom transmission of the pathogen

-

Acid rain stress drove profound adaptive evolution in E. coli O157:H7 at both genetic and phenotypic levels. To assess whether this environmental adaptation translates into a tangible public health threat, we examined the capabilities of the evolved strains in two critical areas: food chain transmission and host pathogenicity.

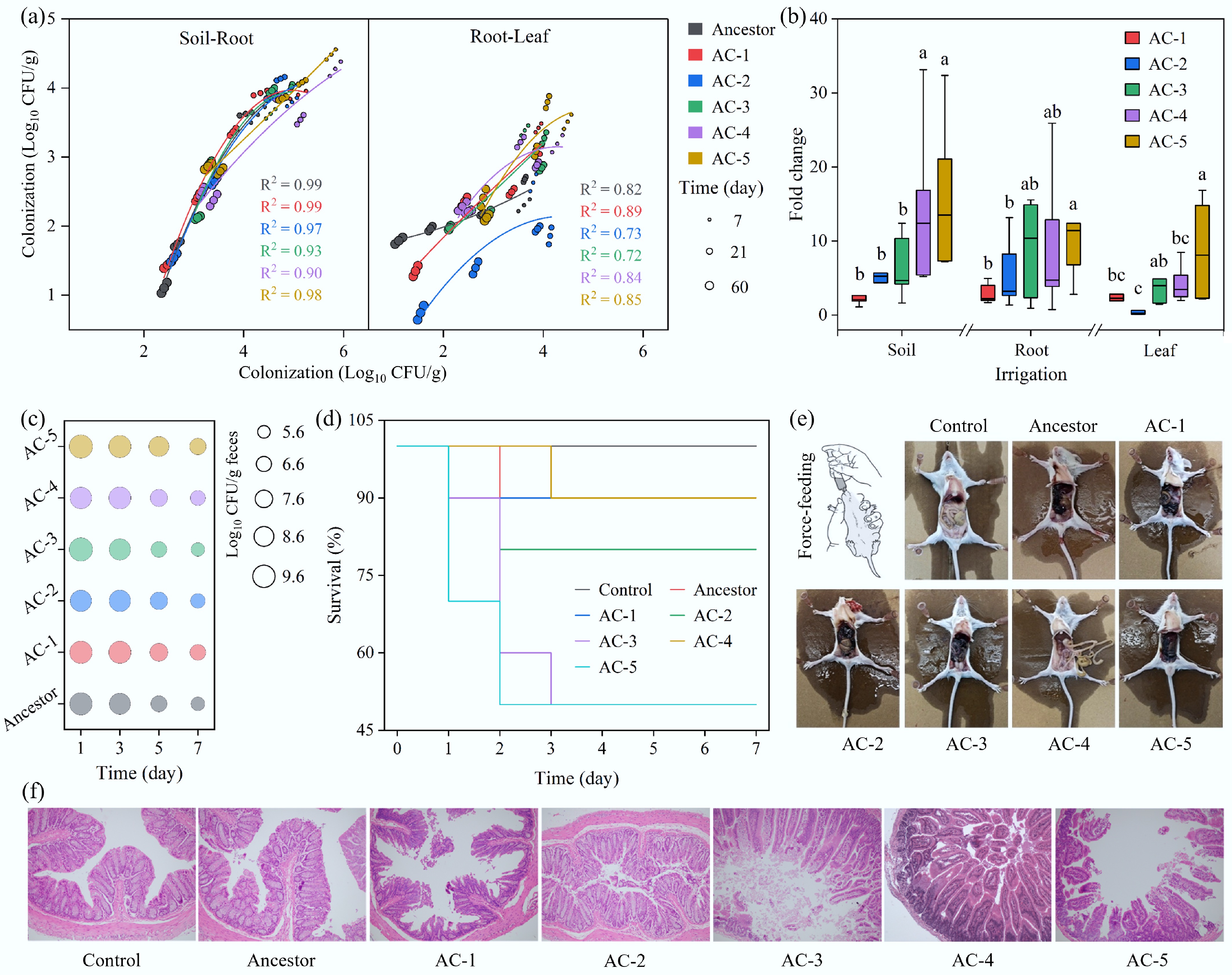

First, the transmission pathway from soil to plants was simulated by evaluating the strains' ability to colonize lettuce (Supplementary Fig. S5). The results showed that all strains followed an invasion route from the rhizosphere to the edible parts (leaves), with their abundance decreasing along the rhizosphere-root-leaf gradient (Fig. 5a). However, the evolved lineages demonstrated far superior transmission potential compared to their ancestor. Notably, in the leaves consumed by humans, the average abundance of the evolved strains AC-3 and AC-5 was 5-fold and 8-fold higher, respectively, than that of the ancestor (Fig. 5b). This not only proves that their colonization advantage in soil can be successfully translated into a colonization advantage in a plant host but also directly indicates a significantly amplified risk of human infection through contaminated produce.

Figure 5.

Ecological risks of the evolved strains. (a) Dissemination of wild-type and evolved E. coli O157:H7 strains in rhizosphere soil, and on lettuce roots and leaves after simulated irrigation. (b) Differences in colonization ability between evolved and wild-type strains. Significant differences for rhizosphere soil, root surface, and leaves are indicated by different letters (p < 0.05). (c) Abundance of E. coli O157:H7 in mouse feces following oral gavage. (d) Lethality of E. coli O157:H7 strains in mice. (e) Anatomical comparison of a healthy mouse and an infected mouse, showing multiple instances of damage to visceral organs caused by an evolved strain. (f) Histopathological sections of mouse tissues.

Next, the pathogenicity of the evolved strains was directly assessed using a mouse infection model. The results confirmed that the environmentally acquired adaptation co-evolved with enhanced virulence. Compared to the ancestor, almost all evolved strains exhibited a greater ability to proliferate within infected mice (Fig. 5c). This enhanced colonization led directly to more severe clinical outcomes: the mortality rate for mice infected with the ancestral strain was only 10%, whereas the AC-3 and AC-5 lineages increased the rate to a statistically significant 50% (Fig. 5d). Necropsy and histopathological analysis further revealed a qualitative shift in virulence: the ancestral strain primarily caused intestinal hemorrhage, whereas evolved strains like AC-1, AC-3, and AC-5 induced more extensive tissue damage, including thrombus formation in adjacent adipose tissue (Fig. 5e). Tissue sections showed that all strains could cause degeneration and necrosis of intestinal mucosal epithelial cells, but the tissue damage was most severe in mice infected with AC-3, whose intestinal structure was almost completely destroyed (Fig. 5f). These phenotypic outcomes are highly consistent with the molecular-level observation of systematically upregulated virulence genes (e.g., T3SS effector protein genes), confirming that the pathogenic potential of the evolved strains was fortified at multiple levels.

In conclusion, environmental stress in soil not only created an ecological opportunity for the pathogen but also drove its rapid evolution. The resulting evolved lineages were not only better environmental survivors but also more efficient transmitters and more lethal pathogens. This study provides compelling evidence that, against the backdrop of anthropogenic environmental change, the eco-evolutionary dynamics of pathogens may be shaping new pathogenic threats with elevated public health risks.

-

While epidemiological links between environmental change and infectious disease are established[5], the underlying eco-evolutionary mechanisms remain largely a black box. The present study illuminates this by demonstrating that acid deposition, a hallmark of industrial pollution, can inadvertently trigger a positive eco-evolutionary feedback loop, forging more persistent and virulent pathogens. We show this process unfolds in three interconnected stages: ecological opportunity, rapid adaptive evolution, and amplified public health risk.

The present findings reveal a crucial ecological paradox: a broadly detrimental stressor can benefit an invader. The study was initially motivated by a global-scale analysis of soil metagenomes, which confirmed that soil pH is a pivotal factor shaping E. coli abundance, with its prevalence surprisingly peaking in weakly acidic conditions (pH ≈ 5.0). This large-scale pattern raised the very question the experiment was designed to answer: how can a generally hostile acidic environment foster E. coli? The results provide a mechanistic explanation that combines the pathogen's physiological resilience with the community's ecological collapse. While acidic conditions likely triggered E. coli's own acid resistance systems, enhancing its baseline survival[41,42], the more critical effect was how acid rain created an ecological opportunity. Contrary to studies linking environmental change to major shifts in microbial community composition[43,44], it was observed that the macroscopic community structure remained remarkably stable. Instead, the critical impact of acid rain was at the microscopic level of species interactions. The stress destabilized the indigenous microbial network not merely by simplifying it, but through a combination of structural simplification and intensified internal competition[45−48], evidenced by a surge in negative correlations.

This finding challenges the conventional view that increased negative interactions necessarily enhance community stability and invasion resistance[49,50]. This observation is, however, consistent with ecological theories positing that excessive internal competition can paradoxically lower invasion resistance[51]. Beyond a certain threshold, pervasive antagonism can erode a community's collective defenses, creating opportunities for invaders that would otherwise be excluded[52]. We propose that beyond a certain threshold[46], excessive internal antagonism can erode collective defense, creating a state of community chaos that provides a crucial ecological opportunity for an invading pathogen like E. coli O157:H7 to establish a foothold. Furthermore, such network destabilization likely compromises essential soil functions, like nutrient cycling and decomposition, that depend on microbial cooperation, thus reducing the ecosystem's overall resilience. This stress-induced mechanism complements other known factors that create environmental reservoirs for pathogens, such as favorable soil phosphorus levels and synergistic microbiota[53].

This ecological opportunity served as the crucible for adaptive evolution[54]. Within just five months, far faster than some reported adaptation timelines, E. coli O157:H7 evolved new strategies to not only survive the acid stress but also to exploit the weakened community. This adaptation was primarily driven by major genomic rearrangements rather than simple point mutations, and is a common strategy for microorganisms to respond to environmental stress[55]. A key finding was the deletion of the Rcs phosphorelay system, a known repressor of biofilm formation[56,57]. This genetic shortcut, releasing the brakes on biofilm production, is highly significant as historical analyses suggest that changes in this and related regulatory pathways were instrumental in the emergence of the highly virulent E. coli O157:H7 lineage[58]. Furthermore, the discovery of a convergent chromosomal inversion near the acid-response regulator ydeO[59,60] underscores how specific genomic architectures can facilitate predictable evolutionary responses to environmental pressures[61,62]. The substantial variation in abundance among these lineages (from 6- to 450-fold) also highlights the stochastic nature of evolution, where distinct evolutionary paths can lead to a wide spectrum of fitness outcomes. These evolved phenotypes also reveal classic evolutionary trade-offs; for instance, the enhanced biofilm formation in most lineages came at the cost of reduced motility, reflecting a strategic shift from dispersal to a fortified, sedentary lifestyle.

Finally, and most critically, it is demonstrated that this environmental adaptation directly translates to heightened public health threats. The evolved lineages were not merely better survivors; they became more effective pathogens. This heightened virulence is plausibly linked to their key environmental adaptations: enhanced biofilm production (via Rcs deletion) is a known virulence factor that promotes gut colonization and immune evasion[41], while improved acid resistance likely increases pathogen survival through the gastric barrier[42]. Their enhanced ability to colonize and persist on lettuce far exceeded that of the ancestor and previous reports[63,64], directly amplifying the risk of foodborne transmission[65]. Strikingly, this enhanced environmental fitness was coupled with a dramatic increase in virulence, transforming a low-mortality infection into a highly lethal one in our animal model. This finding provides a stark warning: the selective pressures in the external environment can simultaneously favor traits that also increase pathogenicity within a host (a phenomenon known as co-selection), effectively turning environmental reservoirs into training grounds for super pathogens.

In conclusion, the present research moves beyond correlation to establish a mechanistic pathway linking industrial pollution to the evolution of enhanced pathogen risk. The 150-d duration of the present experiment, though brief compared to decades of real-world acid deposition, reveals the alarming speed at which such threats can emerge. These findings underscore the urgent need to integrate eco-evolutionary dynamics into surveillance and risk assessment frameworks. Mitigating anthropogenic stressors like acid rain is not only an act of environmental protection but a critical measure for safeguarding public health against the unexpected evolutionary trajectories of microbial pathogens.

We thank Dr. Jichen Wang (Institute of Agricultural Resources and Regional Planning, CAAS, Beijing, China) for providing the global dataset.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/newcontam-0025-0012.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Cai P, Huang Q; investigation: Wang L, Gao C; data curation and visualization: Wang Y, Wu Y, Qu C, Dai K, Zhang M; writing − original draft preparation: Wang L, Xing Y; writing − review and editing: Cai P, Huang Q, Wang L, Wang Y; supervision: Cai P, Huang Q; funding acquisition: Cai P. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All raw 16S rRNA gene sequences were deposited in NCBI Sequence Read Archive under the accession number of PRJNA1157662. The accession number of E. coli O157:H7 evolved strains AC-3 and AC-5 are SAMN43576845 and SAMN43577479, respectively. Other data generated in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42225706, 42177281), and the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province of China (460324005).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Acid rain weakens the natural microbial defenses of soil by disrupting community stability.

Stressed environments act as a selective pressure, accelerating pathogen evolution.

Evolved pathogens become more transmissible to plants and significantly more lethal.

Anthropogenic pollution and pathogen evolution form a positive eco-evolutionary feedback loop.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Liliang Wang, Yunhao Wang, Yonghui Xing

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - Supplementary Table S1 The specific primers for quantifying transcript levels of genes.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Soil physical and chemical properties.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Quantification of E. coli O157:H7 abundance in soil.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Alpha-diversity indexes of the soil microbial community under different rain treatments.

- Supplementary Fig. S4 Soil microbial metabolism under different rain treatments.

- Supplementary Fig. S5 Pot experiments.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wang L, Wang Y, Xing Y, Gao C, Wu Y, et al. 2025. Acid deposition fuels pathogen risk through a coupled ecological and evolutionary cascade. New Contaminants 1: e012 doi: 10.48130/newcontam-0025-0012

Acid deposition fuels pathogen risk through a coupled ecological and evolutionary cascade

- Received: 26 September 2025

- Revised: 16 October 2025

- Accepted: 27 October 2025

- Published online: 12 November 2025

Abstract: Acid deposition, a major consequence of fossil fuel consumption, profoundly alters soil ecosystems, yet its impact on the evolution and virulence of soil-borne human pathogens remains largely unexplored. Here, through a 150-d microcosm experiment, it is demonstrated that simulated acid rain enhances the persistence of the pathogen Escherichia coli O157:H7. This effect was not caused by a disruption in the native microbial community composition, but rather by a destabilization of its internal interaction network, which intensified competition and lowered biotic resistance to invasion. Critically, this acid-stressed environment acted as a strong selective pressure, accelerating the evolution of E. coli. This rapid adaptation was driven by major genomic remodeling, including convergent chromosomal inversions and deletions of key sensory-regulator systems. Evolved isolates consistently exhibited enhanced biofilm formation and optimized motility, leading to superior soil colonization. Strikingly, this environmental adaptation was directly coupled with enhanced virulence; a representative evolved strain showed an 8-fold greater transmission potential to lettuce and a 5-fold higher lethality in a mouse model compared to its ancestor. The present findings reveal a dangerous eco-evolutionary feedback loop where anthropogenic pollution not only promotes pathogen survival but also drives the rapid evolution of hypervirulent and more transmissible strains, posing unforeseen risks to public health.

-

Key words:

- Acid deposition /

- Pathogen survival /

- Microbial competition /

- Adaptive evolution /

- Public health