-

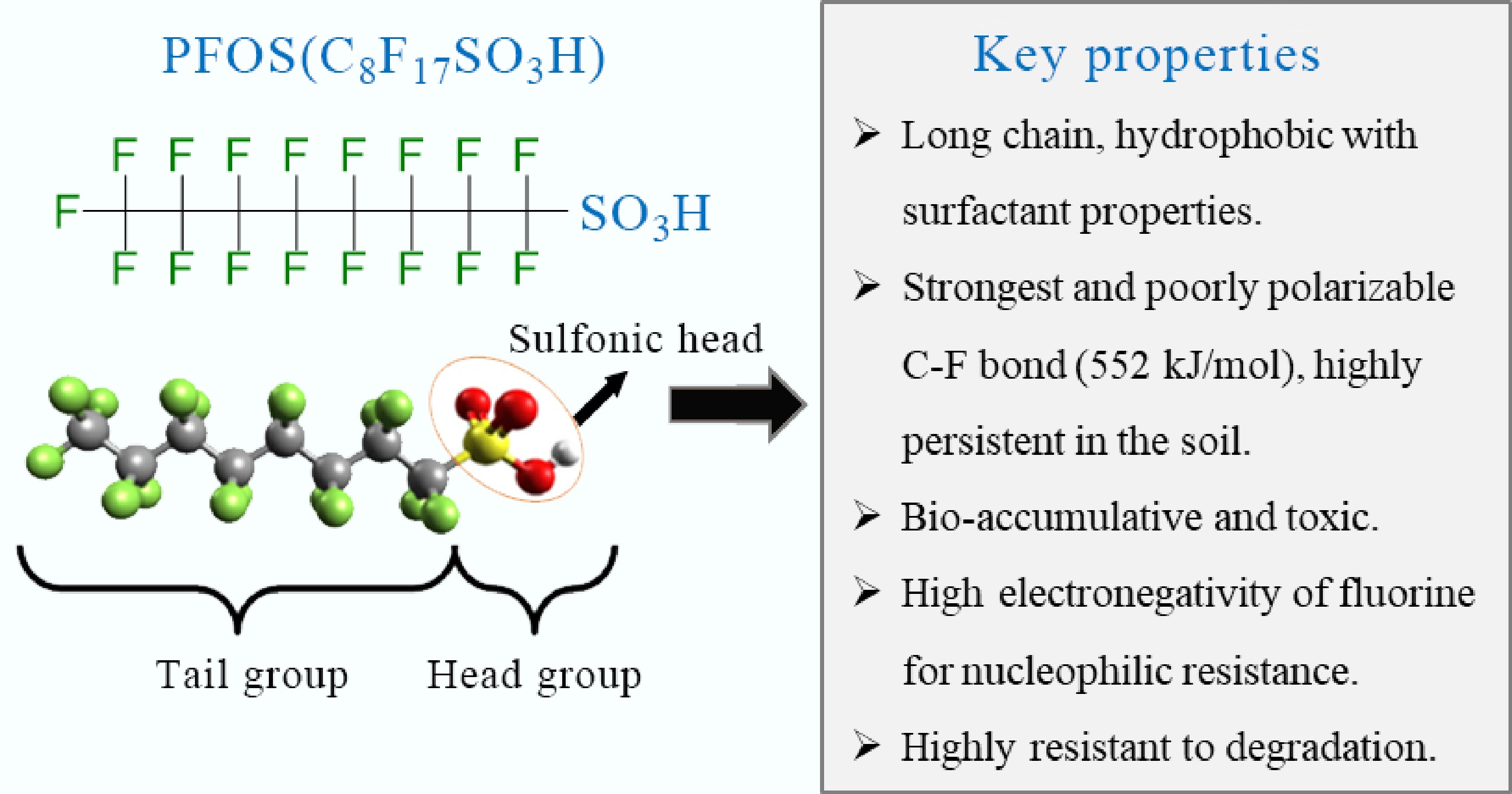

Perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), a synthetic perfluoroalkyl substance, is highly resistant to chemical, biological, and physical degradation due to its strong and poorly polarizable C–F bond (552 kJ/mol) and xenobiotic nature[1−3]. The structure and key properties of PFOS are presented in Fig. 1 below. Due to its persistence, it was listed as a persistent organic pollutant (POP) under the Stockholm Convention in 2009[4]. It has widely been used in industrial and consumer products, including firefighting foams, textiles, electronics, and non-stick coatings, leading to its widespread environmental contamination[5,6]. More importantly, its mobility and bioaccumulation in the environment are of significant concern, especially in the soil–plant system due to its potential ecological and health risks[7−9]. Despite this concern, there is limited knowledge about PFOS in Africa. This lack of knowledge is particularly critical given that industrialization and agricultural yields on the continent are projected to increase by 16% and 23%, respectively, by 2043, which is expected to raise the production and consumption of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) products in the continent. Global studies have demonstrated PFOS persistence in the soil, migration through soil profiles, accumulation in plant tissues, and the resulting risks to the environment and biodiversity[10,11].

While global production of PFOS has declined, legacy contamination persists, particularly in regions with limited environmental regulations (e.g., Africa)[12,13]. Whereas much research has focused on its presence in developed regions[10], less is known about Africa despite the unique environmental, agricultural, and socio-economic conditions that could influence PFOS interactions within the soil–plant system. This gap is due to the limited analytical capacity and high costs of research and monitoring involved, among other factors. Many African laboratories still rely on ineffective gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) and ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) methods for pollutant analysis, rather than the ultra-performance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS)[14]. This has led to an underestimation of contamination levels, affecting risk evaluation. Despite the overall low industrialization levels in Africa, rapid industrialization in certain regions, coupled with urbanization, increased waste generation, and agricultural dependence, has accelerated PFOS contamination risks.

Recent studies, however, have identified PFOS contamination hotspots in several African countries, particularly in urbanized areas and agricultural fields of South Africa, Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya, and Uganda (Supplementary Table S1). A study in South Africa revealed that PFOS was the dominant PFAS in soils near industrial areas[15]. Similarly, PFOS was detected in soils around waste dumps and urban drainage systems in Ghana[16,17]. These results align with global trends, where urbanization, inadequate waste management, and other anthropogenic activities exacerbate PFOS contamination. Exposure to PFOS can cause significant health problems in humans, mammals, and birds, ranging from changes in organ and/or body weights, cancer, and developmental abnormalities to death[18]. While international frameworks such as the Stockholm Convention provide guidelines on handling POPs, the lack of specific regulations for PFOS in many African countries presents a significant barrier to effectively manage this compound in the environment. The regulations of PFAS are still developing in the region, with South Africa leading in formal regulatory measures. In September 2019, South Africa implemented a ban on the use, distribution, sale, production, import, and export of PFOS and its precursors[19]. This regulation mandated the phase-out of PFOS and related products by December 2021[20]. Other African nations have yet to establish specific regulations on PFAS.

However, the African Ministerial Conference on the Environment (AMCEN) supports the integration of sustainable development goals into national policies to help countries address chemical pollutants under broader environmental protection or chemical safety laws, which can encompass PFAS-related issues[21]. For instance, Kenya's Environmental Management and Coordination Act (EMCA), No. 8, enacted in 1999 and revised on December 31, 2022, formed the National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) to provide a general framework for environmental protection. In addition to the EMCA, Kenya has also implemented the Sustainable Waste Management Act, which was signed into law on July 7, 2022, to further strengthen the legal framework for waste management[22]. As awareness of PFAS-related risks grows, it is anticipated that more African nations will develop specific regulations to manage and mitigate the presence of these substances in the environment[23]. However, a wide gap exists between environmental policies and actual implementation due to financial and infrastructural limitations in waste management and environmental conservation in Africa. This study aims to raise awareness of this silent ecological threat to spur appropriate attention and action in the region.

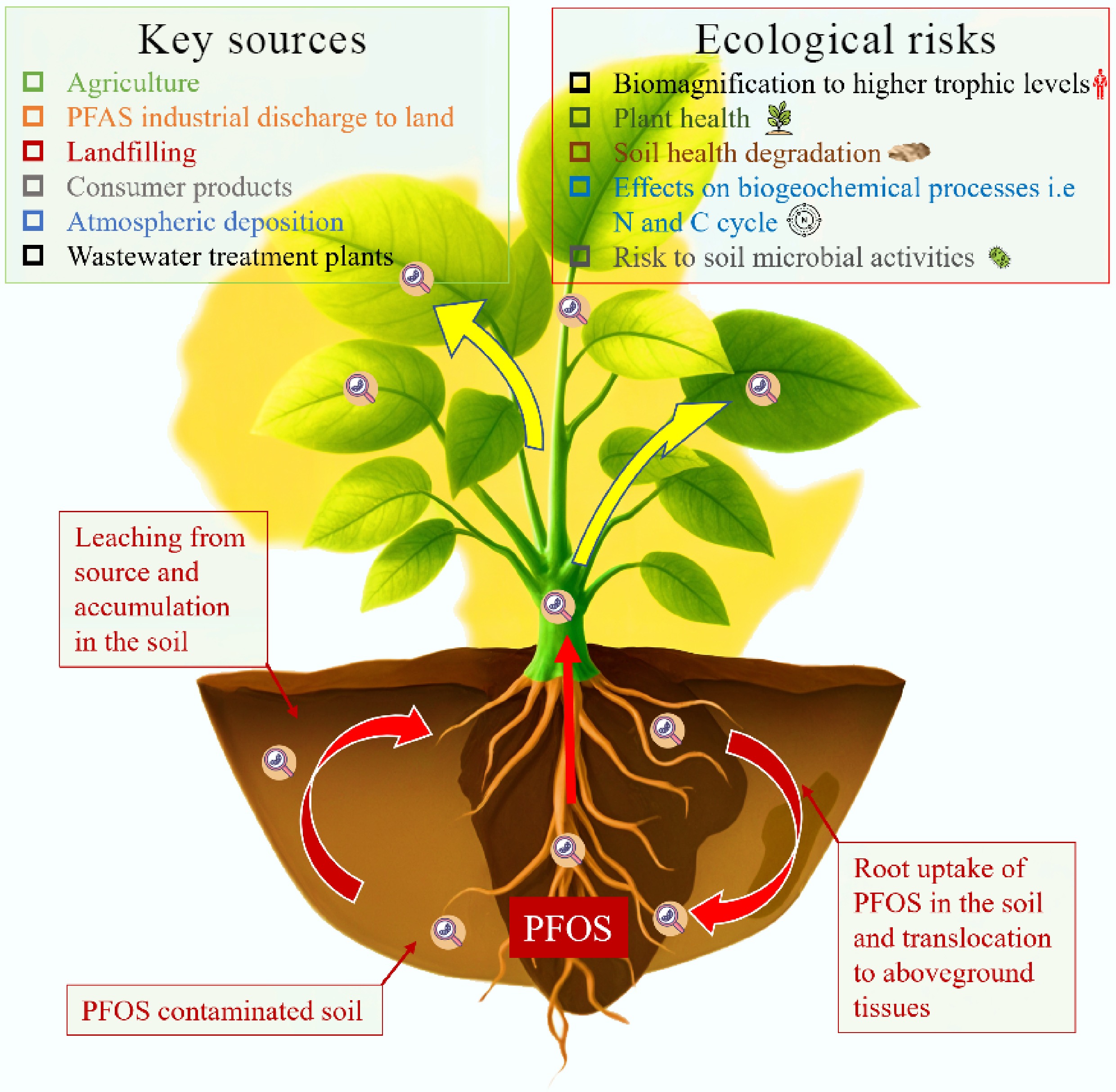

This review focuses on the source and occurrence of PFOS in African soil–plant systems, its fate and transport in the soil, mechanisms of plant root uptake and translocation to aboveground tissues, and associated ecological risks. The implications for human health are also highlighted, and certain mitigation strategies proposed. Finally, data gaps are identified and future research directions are suggested to address this pollutant in Africa.

-

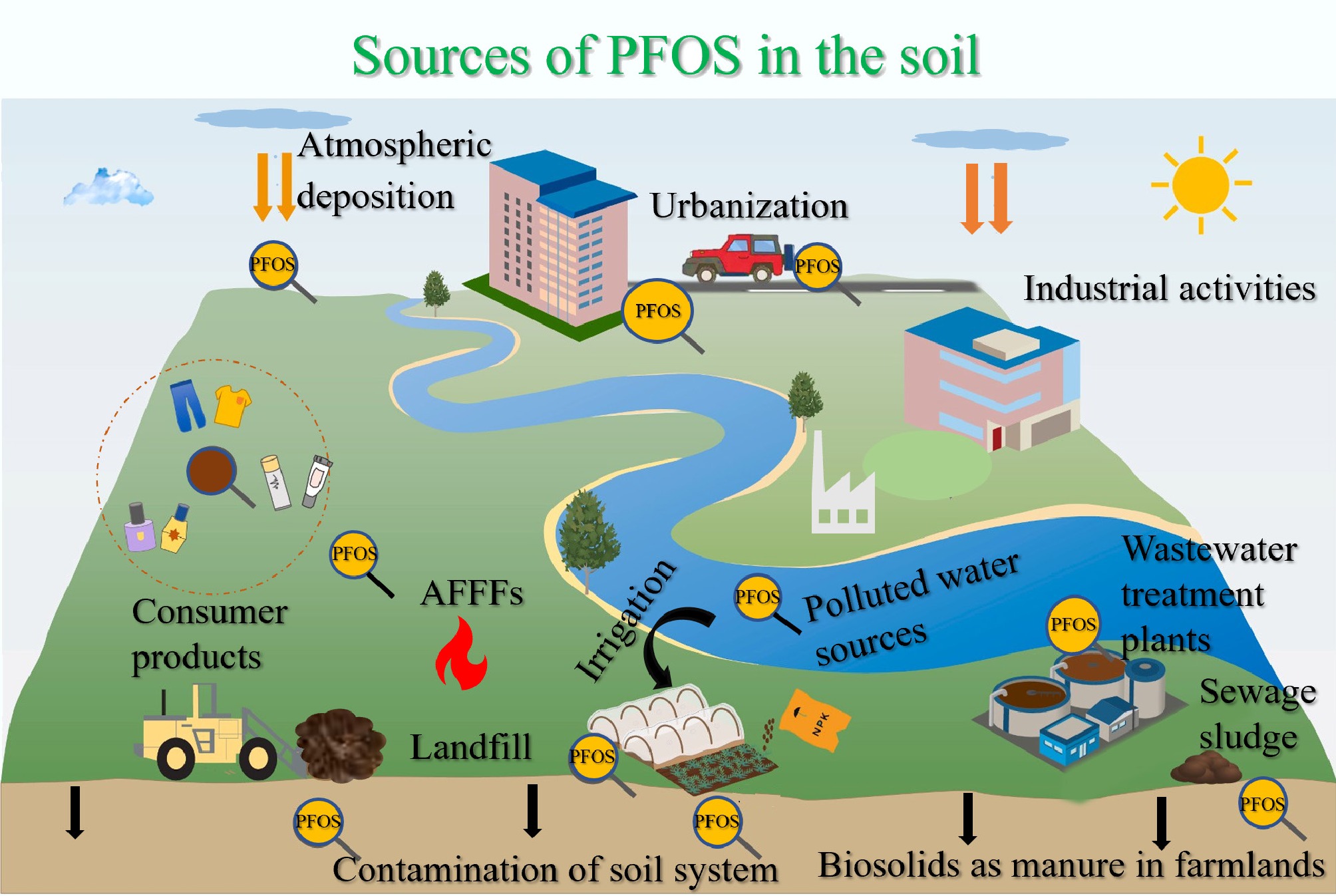

PFOS contamination in African soils may arise from various sources, as illustrated in Fig. 2. Increased urbanization and the presence of emerging contaminants in the environment: PFOS and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) have an average concentration of 0.18 and 2.74 µg/m in textile samples, respectively[24]. PFOS concentrations in soils around industrial zones in South Africa exceeded regulatory limits[25]. Additionally, manufacturing PFOS-related chemicals[26] and importing consumer products, such as carpets, upholstery, and food packaging materials, can introduce PFOS into African soils during their lifecycle and disposal[27,28]. Furthermore, urban hotspots exhibit higher PFOS levels than rural areas[14]. Agricultural practices (e.g., irrigation and use of biosolids as fertilizers): The use of treated water for irrigation is common in water-scarce areas in Africa[29], accounting for 4% of cultivated land in Sub-Saharan Africa and 28% in Northern Africa[30]. This can be a significant route for PFOS to enter agricultural soils. Waste management, e.g., wastewater treatment and waste disposal practices, for example, the alarming levels of PFOS in soils at an e-waste landfill site in Ghana ranging up to 275.3 ng/g, and a research in Kano, Nigeria on soil contamination[31] and transnational hazardous waste disposal, particularly e-wastes produced domestically and by developed countries from the North[32], contribute significantly to indirect sources of PFOS in the soil. PFOS also contaminates soils indirectly via long-range transport (LRT) through atmospheric deposition and water channels[33,34]. Airborne PFOS that settles on soils ranges from 0.44 to 6.75 ng/g in suspended particles, while water contamination facilitates dispersal across regions[35,36], as observed in African rivers and lakes[37,38]. These pathways explain PFOS detection in remote areas like South Africa and Uganda's Mabira Forest[25].

Occurrence of PFOS in African soil

-

Soil as a potential global reservoir of PFAS was first studied, where PFOS was found to have a global soil loading of > 7,000 metric tons from the samples of surface soil collected[39]. Another study also investigated the regional transport and distribution properties of PFOS in China's coastal region using a multimedia-based model, and soil was found to be a major reservoir of PFOS in the environment, accounting for more than 40% of the total mass[40]. In another study, the maximum reported concentrations of PFOS in soil across the globe was reported to range from 0.003 to 162 ng/g, indicating that soil is a significant reservoir of PFOS[41].

The occurrence of PFOS in African soils is not uniform but shows distinct patterns that are closely related to different agroecological conditions, uneven industrial activities and urbanization, varied soil types, agricultural and waste management practices, and significant disparities in research and monitoring capabilities across the continent. Many African agricultural soils are naturally low in soil organic matter (SOM) and often exhibit acidity (low pH). Therefore, in most soils, PFOS binds strongly to organic carbon due to its sticky nature. Soils with low SOM provide fewer binding sites, meaning a larger fraction of the PFOS remains bioavailable (dissolved in the soil water) and is therefore easily taken up by plant roots. The long-chain PFAS, like PFOS, are generally considered to be highly adsorbed to the soil. However, the sorption mechanisms are complex and can be influenced by pH. Highly weathered soils, which are common in Africa, have different mineral compositions (like iron and aluminum oxides) that can interact with PFOS. The exact impact of the common acidic conditions in many African soils on the mobility of PFOS is difficult to determine, but generally, the overall lack of SOM tends to counteract any mineral-based sorption, resulting in increased mobility and uptake of PFOS. Areas with higher industrial activities and dense urban populations tend to have higher concentrations of PFOS in their water systems and subsequently in soil through various sources. Soils in urbanized areas tend to have higher PFOS concentrations compared to those in rural settings, reflecting enhanced anthropogenic influence in the occurrence of PFOS in African soils[14]. According to a previous study, the levels of PFOS in soil are typically highest in primary exposure sites, such as areas near manufacturing facilities or firefighting training sites and waste dumpsites, and lower in secondary exposure sites like marginalized agricultural lands[42].

The levels of PFOS concentrations reported across these different African countries suggest that the extent of soil contamination is likely influenced by localized anthropogenic activities and the presence of specific sources of pollution. Such as industrial waste discharges, and areas with poor waste management practices or significant e-waste processing activities appear to be potential hotspots for PFOS contamination in African soils. While comprehensive data on PFOS occurrence in African soils is still limited, some studies have reported its presence in the soil, as listed in Supplementary Table S1. Ghana, South Africa, Kenya, and Uganda are dominant in terms of the maximum levels reported. From the literature searches that were done from peer research papers in Google Scholar, Semantic Scholar, Scopus, PubMed, Elsevier, ResearchGate, and the internet, the following data were retrieved for analysis in this study.

Fate of PFOS in the soil

-

Soil has been found to be an important reservoir medium of PFOS in the environment[43,44], with a half-life of over 300 years[45]. The fate and transport of PFOS in soil are significantly influenced by its structure, ability to sorb to soil particles, and the soil properties. PFOS is generally considered a very stable compound with the strongest covalent bonds (C–F bonds) in organic chemistry, consisting of a fully fluorinated hydrophobic octyl chain and a hydrophilic sulfonate head group that does not readily break down under typical environmental conditions such as hydrolysis, photolysis, or biodegradation[1]. This chemical and thermal stability makes it extremely resistant and energy-intensive to break down in the environment[46]. The vast size and diverse climates in Africa contribute to its wide variety of soil types. Hot, arid, or immature soil assemblages cover 60% of the land, with a further 20% covered by tropical or subtropical soils[47]. The primary soil types in the continent include Ferralsols, Nitosols, Acrisols, Arenosols, Cambisols, Luvisols, Lithosols, Gleysols, Fluvisols, Vertisols, Histosols, Regosols, Xerosols, Yermosols, Solonetz, Solonchaks, Rendzinas, Phaeozems, and Kastanozems[48]. The varying distribution and specific characteristics of these soils, such as organic matter content, pH, and mineral composition, influence the behavior and fate of PFOS in the soil around the continent. Soils with higher organic carbon content, such as some of the wetland soils or top soils under certain vegetation[49], generally exhibit a greater capacity to adsorb PFOS. Conversely, soils with low organic carbon, like many Arenosols found extensively in Southern Africa, may allow for greater PFOS mobility. The pH of these soils, which varies significantly from acidic (common in deeply weathered, humid central areas) to alkaline (found in some Arenosols in Namibia and South Africa), directly impacts PFOS sorption[50]. Under acidic conditions, electrostatic interactions can lead to increased PFOS sorption, while neutral to alkaline conditions may reduce this effect, allowing for greater mobility.

The mineralogy and texture of African soils, such as the clay-rich Vertisols or gravelly upland soils which contain clay minerals, metal oxides (like iron oxides), and silt content, contribute to PFOS adsorption through various mechanisms, including ligand exchange and metal ion bridging. For instance, the black, clay-rich soils of the Nile Valley, while fertile, have different PFOS retention characteristics compared to sandy or gravelly soils found along the coastlines[50]. Fine-textured soils generally have a higher surface area and more adsorption sites, which can lead to stronger PFOS retention than coarser soils like sandy loams or silt loams, which are preferred for alfalfa production (in Sudan and South Africa). The long hydrophobic chain and sulfonate group in PFOS contribute to its strong sorption to soil organic matter (log Koc = 3.2–3.6) in surface soils compared to shorter chain PFAS and are thus less susceptible to movement through the soil profile[43,50,51]. Transport processes such as advection, dispersion, and diffusion strongly influence its migration within the soil and between other media. However, its mobility in saturated soils is mostly influenced by advective transport[52]. Solid-phase adsorption is a well-recognized process and perhaps the dominant contributor to the sorption behavior of PFOS in soils, in both saturated and unsaturated conditions. In unsaturated soils, PFOS can accumulate at the air–water interface due to its surface-active properties contributing to the overall retention of PFOS in soil systems. The relative contribution of interfacial adsorption could range from < 5% to as high as 85% of total PFOS retention, depending on the conditions related to the geological media, their degree of saturation, and the PFOS chemical properties[53]. Lower pH generally increases the adsorption of chemicals in the soil. For example, certain herbicides like imazaquin and imazethapyr have reduced mobility, especially in silty clay loam soils[54].

Leaching of PFOS varies significantly across different soil types due to their distinct physicochemical properties. Sandy soils, found extensively along the coastlines, exhibit high leaching of anionic perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) compared to soils with higher clay or organic carbon content[36], such as the upland soils. In contrast, clay soils retain PFOS more effectively due to their finer particles, which create a larger surface area for sorption, thus limiting contaminant movement[55]. Furthermore, the leaching of PFOS is influenced by the presence of dissolved organic matter in the soil. In soils like the Vertisols found along the Nile Valley and some upland soils, contain abundant aluminosilicates or phyllosilicate minerals, which carry permanent negative charges and thus offer significant adsorption sites for positively-charged compounds, while organic matter, Fe and Al oxides, and the edges of phyllosilicate minerals have significant amounts of pH-dependent surface charge[55] that limit the mobility of the chemical. The anionic nature of PFOS at environmental pH allows it to interact with positively charged sites on soil particles. This increases the ionic strength, thus enhancing sorption by reducing electrostatic repulsion. Fe and Al oxides can carry a positive charge below their point of zero charge (pH 8), and therefore soils rich in these sorbents can electrostatically adsorb PFOS from the soil solution[53]. The inorganic component of the soil surface can also promote PFOS adsorption through charge-based mechanisms, such as a Ca2+-bridge[42]. Compounds such as humic and fulvic acids can enhance the sorption of PFOS onto soil particles, potentially reducing its leaching into groundwater, while the absence of these organic compounds increases its mobility, especially in sandy soils[56]. PFAS can move with percolating water into deeper soil layers, reaching groundwater reserves[57]. This implies that increased leaching at higher pH values could be due to repulsive electrostatic forces between PFAS and the soil sorption sites. At optimal moisture levels (approximately 10%), PFOS leaching can be drastically reduced due to enhanced sorption interactions that occur when the soil structure is adequately hydrated[58]. Well-drained soils, like many upland soils in West Africa and Ferralsols in Cameroon, can facilitate the leaching of PFOS through the soil profile, whereas poorly permeable soils, such as those found in Sahelian landscapes, could lead to different transport patterns, potentially increasing surface runoff. The presence of water reduces the initial crushing strength of soil particles, affecting their compression behavior and potentially influencing PFOS transport. Soils vulnerable to erosion and nutrient depletion, such as those under tropical rainforests following vegetation removal, could experience altered PFOS transport if soil particles carrying adsorbed PFOS are displaced. Several studies modelling the fate and transport of PFAS at contaminated sites have shown that soils in the unsaturated zone serve as a significant long-term source of PFAS[59−61].

Factors influencing the occurrence of PFOS in the soil

-

Several factors influence PFOS mobility and bioavailability in the soil including, soil type and soil properties such as organic matter content, pH, and clay content. Soil organic matter and surface chemical properties of soils are key factors influencing PFOS sorption[40]. Organic carbon is a primary sorbent for PFOS via hydrophobic interactions. It varies greatly and is generally lower in mineral topsoil than in temperate regions due to rapid decomposition (high temperature/humidity). However, in many tropical soils, the mineral component (metal oxides) can be a more significant factor for PFOS sorption than organic carbon alone. In tropical and sub-tropical agroecological conditions, extreme weathering breaks down primary minerals, leaving behind high concentrations of highly-reactive Fe and Al oxides (sesquioxides). On the other hand, heavy rainfall leaches out basic cations (like Ca2+ and Mg2+), leading to low-nutrient, acidic soils[49]. These resulting acidic, oxide-rich soils maximize the electrostatic attraction for the anionic PFOS molecule, enhancing its sorption and stability within the soil structure. The presence of humic acid enhances the sorption of all PFOS isomers, while fulvic acid inhibits their sorption onto soil[56]. PFOS can accelerate the decomposition of organic matter in soil, leading to changes in soil pH[62]. A study found that while total organic carbon (TOC) showed a significant positive relationship with the distribution coefficient (Kd), it accounted for approximately 35% of the variance in PFOS sorption in soils. The TOC contents declined rapidly with depth in soil profiles, and the Kd of PFOA also showed a decline with depth in soils[53]. Furthermore, in sequentially extracted humic substances from a peat soil, PFAS sorption was inversely proportional to the contents of aromatic TOC as well as phenolic and carboxylic moieties. The study also compared the sorption of PFOS by TOC and non-oxidizable organic matter in soils by treating the soils with persulfate and found that the Kd of PFOS in treated soils was two to six times greater than in untreated soils, indicating that TOC content is an important factor affecting the sorption of PFAS in different soils[51]. Therefore, in areas where PFOS is less mobile (especially in the sub-Saharan savanna, equatorial, and some Mediterranean regions, as well as the highland areas of Africa), it can easily be taken up by food crops grown on contaminated land, creating a pathway for human exposure. Many African soils are often relatively porous; therefore, over long-time scales, particularly in regions with high seasonal rainfall, PFOS can slowly leach out of the soil profile, eventually contaminating the groundwater, a critical source of drinking and irrigation water in many parts of Africa, threatening ecological life.

Soil pH (acidity) also influences the fate of PFOS in the soil, especially in highly leached, low-base saturation soils common in the humid tropics of Africa. Since PFOS is an anion, as pH decreases (becomes more acidic), the number of positive charge sites on mineral and organic surfaces increases, which strengthens the electrostatic attraction and sorption of the negative PFOS molecule. PFOS isomers also exhibit different sorption behavior, with linear PFOS readily sorbing onto soils with very low pH (< 4.5), and the least sorption under a high pH range. Soil type also plays a significant role in PFOS mobility and bioavailability through various soil properties [organic matter content, clay content, pH, and cation exchange capacity (CEC)][63]. Higher organic matter and clay content in soil can lead to increased sorption of chemicals and reduced their mobility[63]. For instance, clay soils retain PFOS more effectively than sandy soils, which have lower adsorption capacities[64,65]. Conversely, sandy soils with low organic matter allow for greater PFOS mobility; that is, soils with sand content > 80% and organic matter < 1% can result in almost 100% elution of norflurazon herbicide from soil columns[58]. Therefore, higher TOC content generally leads to greater PFOS retention due to hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions[43].

In the African context, soils with higher organic carbon content, such as in some wetland soils or topsoil under vegetation like those in Tropical and Mediterranean regions, generally exhibit a greater capacity to adsorb PFOS, reducing its mobility. This is due to the presence of humic acid, which enhances the sorption of PFOS isomers onto soil due to increased capacity for hydrophobic interactions with the fluorinated tail, while fulvic acid can inhibit it due to competition for binding sites or by alteration of surface charge characteristics of soil minerals. Luvisols found extensively in the humid and sub-humid wooded savannah zones, known for agriculture due to their high organic matter, may also exhibit lower PFOS mobility. Conversely, soils with low organic carbon, like many Arenosols found extensively in coastal Africa, Southern Africa, and Sub-Saharan Africa, may exhibit greater PFOS mobility due to their low organic carbon content and CEC. This contributes to their reduced organic matter and fewer chemical binding sites that will potentially lead to higher mobility and leaching. Furthermore, soil type can also modulate the interaction between metals and PFOS. For example, soil type and land use can alter the soil organic matter content and free iron-aluminum oxides, which in turn affect the bioavailability of selenium (Se) and cadmium (Cd), and thus the mobility of Se and Cd[66]. The polyvalent cations such as Ca2+, Mg2+, Fe2+, and Al3+ in soil solution (and on the soil exchange complex) affect the sorption behavior of PFOS by influencing the electrostatic interactions within the soil solid phase, promoting the sorption of PFOS in soils. Conversely, monovalent cations such as Na+ and K+ in solution have little effect on PFOS sorption[53]. The high Fe3+ and Al3+ content in Ferralsols readily binds with PFOS. Furthermore, Ferralsols and Acrisols are considered very acidic, with a high amount of organic matter under natural conditions, influencing PFOS sorption via a combination of electrostatic interactions and organic carbon partitioning. Nitosols, which are among Africa's most fertile soils, contain a high amount of humic and fulvic acids, which increase the sorption potential of PFOS onto the soil particles.

Moreover, land use, such as historical application of contaminants through processes like land application of biosolids from past practices, can significantly affect current PFOS levels observed in soil[67]. Land degradation through destructive extraction, over-exploitation, and inadequate conservation practices common in Sub-Saharan Africa can also impact soil health and potentially the fate of PFOS[48]. Therefore, the presence of PFOS in soil can lead to its accumulation in the food chain, posing risks to both human and ecological health. Thus, it is important to understand the occurrence and exposure pathways of this 'forever chemical' in the environment.

-

Plant uptake of PFOS has been reported by different studies globally for different plant species (e.g., wheat, carrots, alfalfa, strawberry, and leafy vegetables such as lettuce, kale, spinach, and beets). PFOS has been found to be taken up by plants with a bioaccumulation factor (BAF) ranging from 0.10 to 3.12, as reported by some global studies[68−70]. In Africa, few studies have investigated the presence of this chemical in the soil–plant system due to the lack of research and monitoring programs, as well as capacity development targeting this domain. There is a lack of well-trained analytical personnel and the use of outdated methods in detection, resulting in lower detection, and in some cases, under- or over-exaggeration of environmental data. It is reported that despite the occurrence of PFOS in Ugandan soil, the soil–plant concentration ratio was less than one for the plant species studied (sugarcane, maize cobs, and yams)[43]. The reported PFOS levels in African plants are still lower than those reported in industrialized countries like Germany, the USA, Canada, and China. It can bioaccumulate in plants common to Africa, like maize, sugarcane, and wild plants. There is a need for proper capacity building, and research is needed to fully understand its presence in plants.

The main pathways for PFOS entry into plants are mainly root uptake facilitated by practices such as the application of contaminated biosolids as fertilizers (high levels in Ghana), landfilling, and the use of treated wastewater or contaminated river water for irrigation (found to contain high levels of PFOS), all of which expose most agricultural plants to the chemical. For example, the Kakume River in Ghana was reported to contain high levels of PFOS (77–160 ng/L)[71]. Rivers within the Lake Victoria basin in Kenya also contained PFOS at concentrations ranging from 0.4 to 8.3 ng/L[63]. Moreover, PFOS concentrations in irrigation with treated wastewater ranged from 1.3 to 28 ng/L in Uganda[72], and from 0.9 to 18.8 ng/L in Kenya[43]. Due to the high levels of agricultural activities along these rivers, PFOS can easily be taken up by plants via the transpiration stream when the water is applied to the land. A study[73] in Kampala, Uganda, demonstrated the entry of PFAS in plants from wastewater-contaminated soil, although accumulation was low. PFAS are absorbed by crops when either biosolids are applied as fertilizer or contaminated water is used for irrigation. The amount of uptake depends on the type of PFAS—with perfluoroheptanoate (PFHpA) and PFOA dominating different plant tissues studied in Uganda—and the crop species. Shorter-chain PFAS have been demonstrated to accumulate more in the edible parts compared to the longer-chain PFAS, which tend to accumulate more in the roots. Consumption of contaminated crops is a major route of human exposure, which creates public health concerns compounded by the limited monitoring capacity in many African countries. While research is still limited compared to other continents, there is direct evidence from Uganda, and highly contaminated source materials (wastewater, river water, and biosolids) have been documented across South Africa, Uganda, and other countries, establishing a clear risk and confirmed pathway for PFAS contamination in African crops.

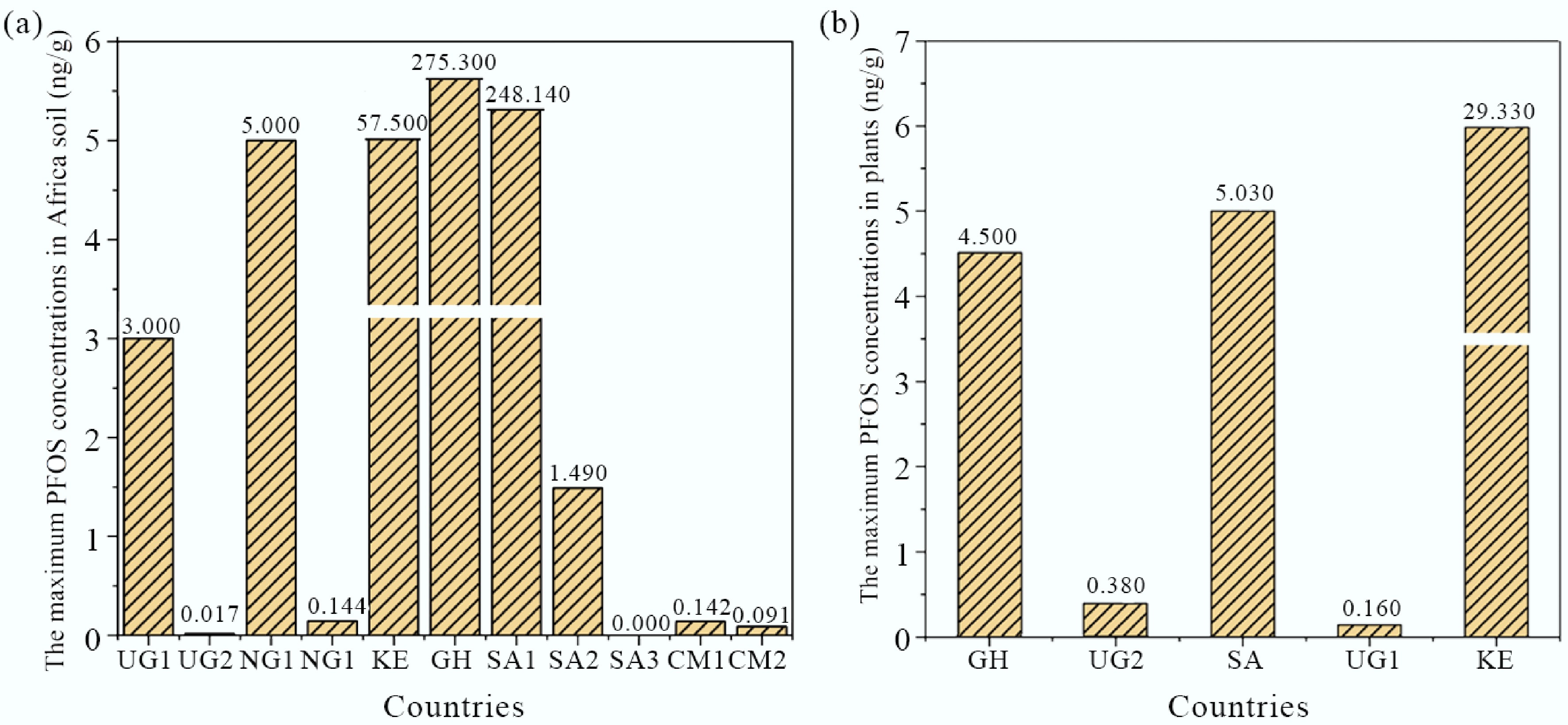

Studies in Kenya[37], South Africa[74], Ghana[75], and Uganda[43] have detected varying concentrations of PFOS in different types of plants. Based on the literature search, the data in Supplementary Table S2 and Fig. 3 below were retrieved for the analysis of PFOS concentrations in African plants. One study also investigated riparian wetland plants (Xanthium strumarium, Phragmites australis, Schoenoplectus corymbosus, Ruppia maritime, Populus x canescens, Polygonum salicifolium, Cyperus congestus, Persicaria amphibia, Ficus carica, Artemisia schmidtiana, and Eichhornia crassipes) along the Diep, Eerste, and Salt River[74]. PFOS levels were found to be below the limit of detection for all the plants studied, although PFOA ranged from 11.7 to 38 ng/g in the reeds, with river water and sediments reported as contamination sources. These findings highlight the potential for PFOS to enter the food chain through the uptake by plants and accumulation in edible parts, leading to bioaccumulation in humans and animals that consume these plants.

Figure 3.

The maximum concentrations of PFOS in: (a) the soil, (b) and plants collected from different locations in Africa (UG1: Uganda; UG2: Mabira Forest Reserve, Uganda; NG1: Nigeria; NG2: Jos, Nigeria; KE: Kenya; GH: Ghana; SA1: Cape Town, South Africa; SA2: South Africa; SA3: Mapunguwe National Park, South Africa; CM1: Buea, Cameroon; CM2: Edea, Cameroon).

Plant root uptake and translocation of PFOS from the soil

-

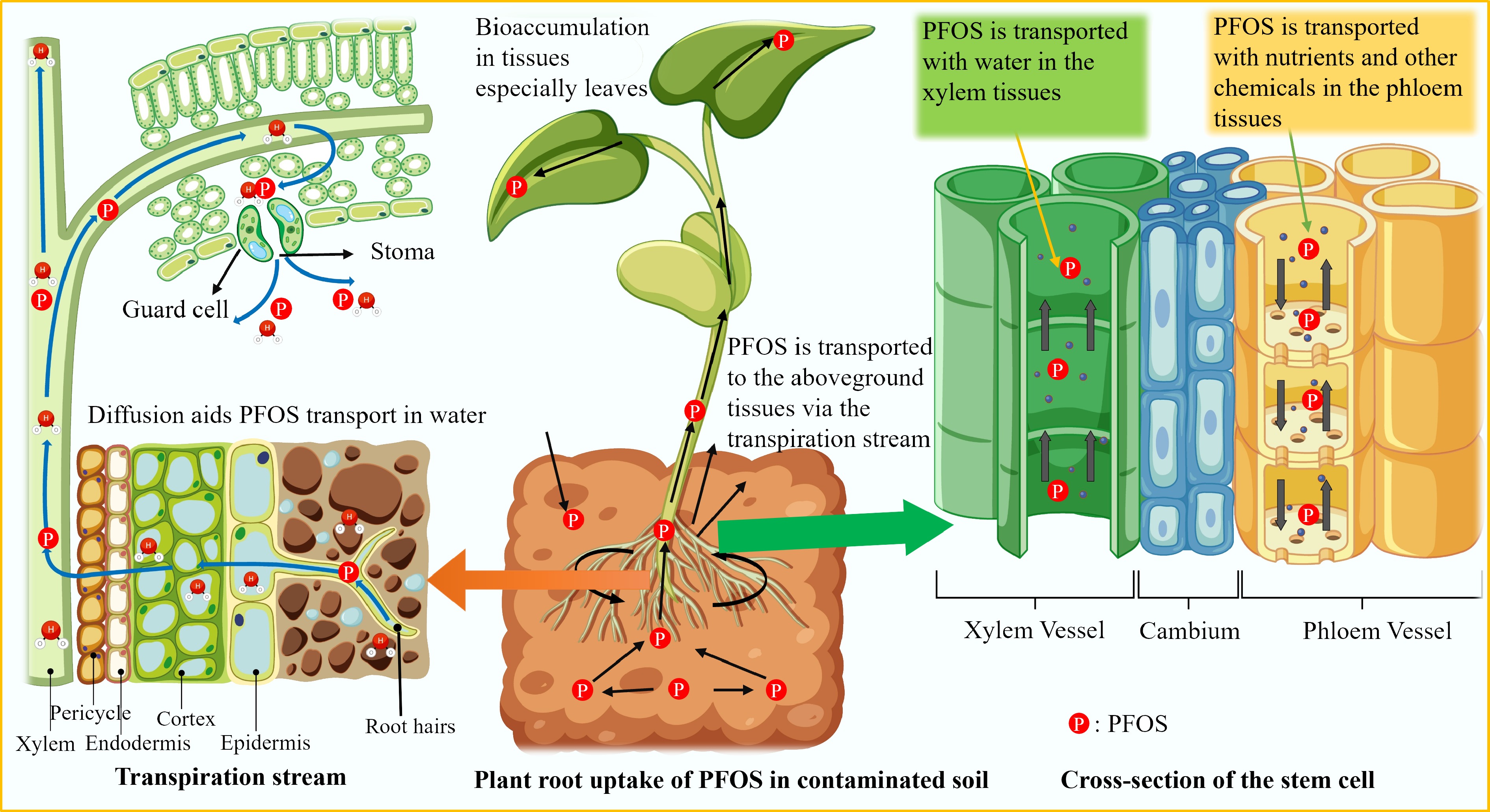

Plant roots serve as the primary interface between plants and the soil environment, playing a critical role in the uptake of water, nutrients, and contaminants such as PFOS[75,76]. Global studies reveal that PFOS in plants can be transported from the hydroponic solution to the root cortex via the transpiration mass through apoplastic (across cell walls and/or intercellular spaces) and symplastic routes (across plasma membranes or via plasmodesmata)[77]. The model of root uptake and accumulation of PFOS is illustrated in Fig. 4 below. The physicochemical properties of PFOS, including hydrophobicity, coupled with the root concentration factor (RCF), charge, and the presence of the sulfonate group, influence its affinity for root surfaces[76,78,79]. Longer-chain PFAS generally show greater accumulation in roots, gradually moving to the above-ground tissues, whereas short-chain PFAS are distributed across above-ground tissues. Additionally, the concentration of PFOS in the soil directly impacts the amount that plants can absorb. In Africa, this mechanism is difficult to explain for local crops and plants because of the lack of studies on the uptake of PFAS by plants; thus, a global understanding is employed to explain this mechanism. Nevertheless, a study in Uganda observed a lower plant–soil concentration ratio for PFOS in crops that may be attributed to the strong sorption of PFOS to the soil, as indicated by its log Kd values (soil–water partitioning coefficient) ranging from 2.8 to 3.1 L/kg in wetland soil under yams[43]. A higher log Kd value suggests that PFOS tends to bind to soil particles rather than dissolving in the soil water, which is the primary medium for root uptake. Root exudates, including organic acids, enzymes, and secondary metabolites, modulate PFOS availability by altering local soil pH, redox conditions, or competing for sorption sites[80]. Thus, while the transpiration stream is involved in the upward movement of PFOS, its efficiency is limited by the compound's physicochemical properties (long-chain), leading to greater interaction with root tissues or sorption to xylem walls.

Figure 4.

Root uptake and translocation via transpiration and cell membrane (symplastic and apoplastic pathways) of PFOS to aboveground tissues via the cortex, phloem, and xylem cells.

Once PFOS enters the root xylem through mechanisms such as passive diffusion, driven by concentration gradients, active transport, and membrane transport proteins, it is transported to the above-ground tissues along with the flow of water via the transpiration stream[80]. The plasma membrane regulates PFOS movement into and out of root cells. Root cell walls, composed primarily of polysaccharides like cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin, act as the first barrier encountered by PFOS and can serve as temporary storage sites through sorption processes[76]. These chemicals are transported from roots to stems mainly through the cortex, to the leaves via the xylem, and to the fruits via the phloem[77].

The efficiency of PFOS uptake is significantly influenced by root architecture, including protein and lipid content and surface area, as well as by the transpiration rate and overall plant metabolism available for contact with the soil solution. Plants with extensive root systems, characterized by a high density of fine roots and root hairs, generally exhibit a greater capacity for contaminant uptake[76,80]. Furthermore, a study observed a positive correlation between root protein content and PFOS uptake[80]. Certain plant species, such as silver birch, Norway spruce, bird cherry, and long-beach fern, have demonstrated a high capacity to accumulate PFOS, suggesting their potential utility in phytoremediation efforts[81]. Conversely, other species or varieties might exhibit lower uptake rates, which is a critical consideration for ensuring food safety in areas with PFOS contamination.

Exposure to perfluorophosphinates (PFPiAs) in roots ultimately leads to the accumulation of more persistent PFPAs in the above-ground parts of plants[82]. A recent study on Arabidopsis thaliana also identified the phosphate transporter, PHT1;8, as being involved in the active transport of PFOS from the roots to the shoots[83]. Thus, PFOS can utilize existing nutrient transport pathways within the plant, potentially mimicking phosphate or interacting with the phosphate transport system to facilitate its movement. The presence of copper (Cu) also affects PFOS distribution, especially in maize tissues. While concentrations of < 100 μmol/L Cu have a limited effect on PFOS bioaccumulation, levels of > 100 μmol/L Cu can damage the root cell membrane and increase root permeability, resulting in a higher PFOS concentration in roots[84]. Moreover, environmental factors such as pH, soil moisture, temperature, the presence of co-contaminants, and plant species also influence the interaction between roots and PFOS. At typical environmental pH levels (around 4–7), PFOS exhibits an anionic nature and thus carries a negative charge, affecting its binding to roots[70,76,80].

The highest translocation factor (TF) for PFOS in aboveground tissues to that in roots was highest in radish than in alfalfa, lettuce, maize, mung bean, soybean, and ryegrass[85]. The Casparian strips in plant roots have been found to partially restrict the translocation of PFAS from the roots to the upper parts of the plant[77,86]. PFOS concentrations in carrot leaves (320–777 ng/g) were much higher than those in lettuce leaves (53–101 ng/g) since carrot lacks the Casparian strip[33,87]. Thus, the Casparian strip plays a critical role in the transport of chemicals to the aboveground tissues in plants.

The transfer factors of PFOS according to a previous study[88] from exposed root to other unexposed parts of the plant organs such as the leaves (TF, root-to-leaf) and from the exposed leaves to unexposed roots (TF, leaf-to-root) in plants can be calculated using Eqs (1) and (2) below:

$ {\text{TF}}_{\text{root-to-leaf}}=\dfrac{\text{PFOS concentration in the unexposed leaf (ng/g dw)}}{\text{PFOS concentration in the exposed root (ng/g dw)}}\text{} $ (1) $ {\text{TF}}_{\text{leaf-to-root}}=\dfrac{\text{PFOS concentration in unexposed root (ng/g dw)}}{\text{PFOS concentration in exposed leaf (ng/g dw)}\text{}} $ (2) Bioaccumulation in plants

-

The key to understanding the ecological risks of PFOS is its accumulation potential in edible parts of the plant. Studies have demonstrated the bioaccumulation of PFOS within various plant organs following root uptake[89]. A previous study investigated the uptake of PFAAs on hydroponically grown lettuce (Lactuca sativa) and found that the RCF was highest compared to foliage-root concentration factors (FRCF) in long-chain PFAAs[64]. This was attributed to their hydrophobic properties limiting mobility within the plant. Different crops exhibit varying capacities for PFOS uptake, with leafy vegetables showing higher accumulation rates. Furthermore, leafy vegetables like spinach and lettuce exhibited higher PFOS accumulation due to their large surface area and direct contact with contaminated soils[29]. Early research also investigated PFOS accumulation in common crops like wheat, oats, potatoes, maize, and ryegrass, and quantified PFOS concentrations in different plant tissues[89]. It found that accumulation increased with an increase in soil pollutant concentrations, with higher values in vegetative parts than in grains. Subsequent research also confirmed the accumulation of PFAAs in the straw and grains of maize plants for C4 to C10 substances containing the carboxylic (perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids, PFCAs) or sulfonic (perfluoroalkyl sulfonic acids, PFSAs) functional groups, all individually spiked at 0.25 and 1 mg/kg soil[90]. They found a direct correlation between soil and plant tissue concentrations, i.e., the higher the soil PFAS content, the more the accumulation in plants. Variation in the accumulation levels of compounds in plants depends on chain length, with the longer-chained compounds generally having lower accumulation rates, and on the associated functional groups, with PFSAs generally having lower accumulation rates than PFCAs. Transport into plant fruits originates from the leaves, where PFAAs enter the phloem and flow to fruit tissues with water. Furthermore, straw with a PFAS content of around 52,000 ng/g dw had a much greater rate of accumulation than kernel with around 900 ng/g dw at an individual spiking dose of 1 mg/kg for a total of 10 mg/kg soil, despite much being retained in the root. Maize is one of the most studied plants regarding bioaccumulation due to its ability to yield flowers, fruits, stems, roots, and leaves at the same time, and is easy to cultivate[91]. However, the overall understanding of PFOS bioaccumulation and movement within plants remains complex and somewhat inconsistent due to factors such as environmental conditions, differing PFOS structures, and variations in plant species[92]. As reported by a previous study[80], the following formula can be used to calculate the BAF in plant organs relative to root exposure concentration:

$ \text{BAF}=\dfrac{\text{PFOS concentration in plant (ng/g dw)}}{\text{PFOS concentration in soil (ng/g dw)}} $ (3) A study in South Africa investigated the BCF for PFOS and PFOA in a medicinal plant (Targetes erecta L.)[74]. The BCF was found to range from 13.67 to 72.33. This study confirms that PFOS in the soil can accumulate in the aboveground tissues of plants, potentially causing detrimental risks to humans and other animals in the food chain.

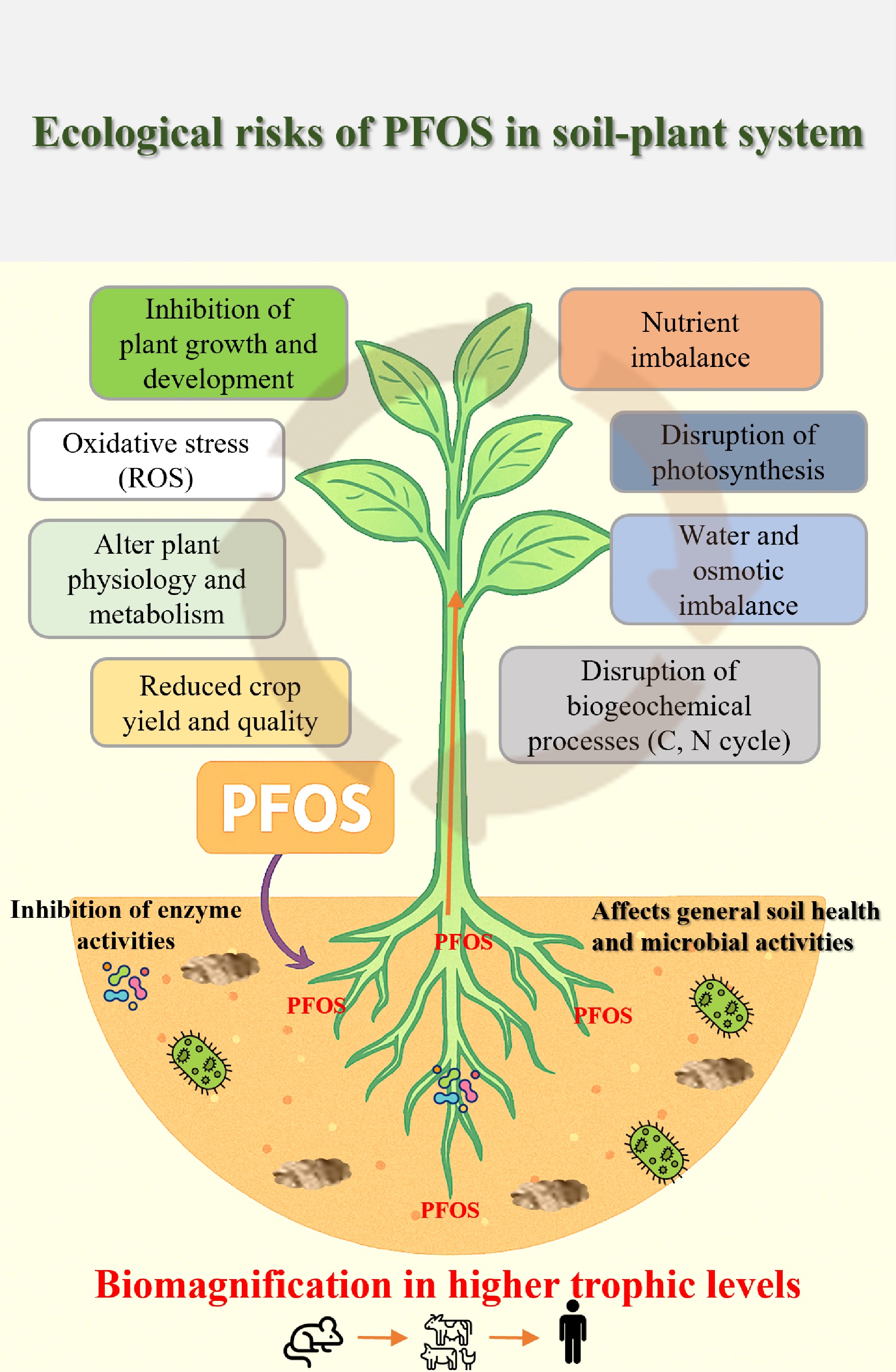

-

PFAS research in Africa is noticeably deficient, making it challenging to understand the extent and specific impacts of these contaminants in the context of local soil conditions. Despite this challenge, the ecological risks posed by PFOS in soil–plant systems are increasingly relevant due to the potential load introduced into the environment from different sources. These potential ecological risks are demonstrated in Fig. 5 below. Global studies have demonstrated the impacts of PFOS on plant and soil health. The potential for PFOS to bioaccumulate in plants highlights a direct pathway for human exposure through the uptake of such plant products.

Soil health and microbial community disruption

-

One of the primary concerns regarding PFOS is soil contamination and the general impact on plant health and function. PFOS is known to interfere with the plant's essential nutrient transport systems, particularly phosphate (P) transporters. Many African soils are deficient in essential nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. Phosphorus deficiency, in particular, is a major constraint across large parts of Sub-Saharan Africa due to naturally low P levels and high soil P fixation. PFOS-induced disruption of the P-transport system would have a devastating impact on crop growth in soils that are already critically low in P, further limiting an already scarce resource. Additionally, PFOS persistence in the soil can disrupt the delicate balance of microbial communities essential for nutrient cycling, organic matter decomposition, and soil structure, ultimately affecting the overall fertility of these soils[93]. The increasing concentrations of PFOS enhance litter decomposition, which could lead to a greater release of reactive oxygen species (ROS), carbon (such as CO2, CH4), and dissolved organic carbon (DOC), thereby affecting carbon sinks in the soil[94]. The priming effects caused by PFOS accelerate the consumption of DOC, resulting in a significant increase in SOC mineralization[55]. The alteration in carbon cycling has been reported to lead to reduced carbon storage in soils and potentially affect overall soil structure and fertility. Previous research indicates that PFOS has a larger effect size on water-stable aggregates[94]. Furthermore, it can increase soil pH, likely due to increased litter decomposition. Increased soil pH and changes in soil structure impact the overall soil health. Soil microorganisms play a crucial role in nutrient cycling and soil health. PFOS has been shown to inhibit microbial activity, reducing the diversity and abundance of soil bacteria and fungi[80]. In a global study, high concentrations of PFOS (especially above 100 ng/g dw) have been shown to significantly reduce the abundance, richness, and diversity of soil bacteria, as indicated by lower values for the mean Shannon (6.12 ± 0.65) and Chao1 (2,565 ± 813) diversity indices[95]. PFOS exposure can lead to shifts in the composition of soil microbial communities, often resulting in the enrichment of bacteria that are more tolerant to the presence of PFOS, such as Proteobacteria, Burkholderiales, and Rhodocyclales[80]. Conversely, certain bacterial groups that are known for their sensitivity to environmental stressors, such as Actinobacteria and Chloroflexi, may experience a reduction in their population size in PFOS-contaminated soils[96]. PFOS also affects functional genes and metabolic pathways of soil microorganisms. Functional gene prediction studies have suggested that PFOS exposure might inhibit key microbial metabolism processes, including nucleotide transport and metabolism, cell motility, and carbohydrate metabolism[80]. This has been reported to lead to decreased soil fertility and impaired ecosystem functions[94]. Additionally, for a sensitive endpoint like earthworm reproduction, PFOA showed significant effects at 100 mg/kg, while lethal toxicity is observed at much higher concentrations.

Risks on enzyme activities

-

PFOS contamination in the soil has been shown to exhibit varied effects on biochemical processes, including nutrient cycling and organic matter decomposition by altering the activities of key enzymes in the soil[95, 97]. In a greenhouse experiment, PFOS levels of 10 mg/kg soil inhibited soil enzyme activity (e.g., urease, sucrase) and destroyed the cellular structure of soil bacteria, which are important in carbon and nitrogen cycling[94, 98]. Furthermore, the high levels (ppm levels) affect soil microbial community through inhibition of soil enzyme activity and destroying the immune system, and gene expression of soil bacteria[95]. PFOS exhibits concentration-dependent effects, where short-chain PFAS might activate certain enzymes at low levels, while long-chain PFAS tend to inhibit them, especially at higher concentrations[94]. In low PFOS-treated soil, soil protease levels were high compared to high PFOS-treated soil[98]. A previous study found that an exposure concentration of 12.5 mg/kg induced the highest activity of enzyme GSH-PX in earthworms (Eisenia foetida), and at 50 mg/kg, the activity of catalase (CAT) was 2.83 times that of the control group, and SOD reached 2.19 times that of the control[95]. The overproduction of ROS due to the oxidative stress caused by PFOS contamination also activates various detoxifying mechanisms in plants, including the production of enzymatic antioxidants (like superoxide dismutase and catalase) and non-enzymatic antioxidants (like glutathione) in an attempt to mitigate the stress[99]. Furthermore, the enzyme phosphatase involved in phosphorus cycling has been identified as a sensitive biomarker for pollution by PFOA[100], suggesting a potential similar sensitivity to PFOS. Additionally, soil exposure to PFAS has been shown to reduce dehydrogenase activity and the overall rate of soil respiration, influencing microbial function and activity in plant roots[98].

Plant growth and physiology

-

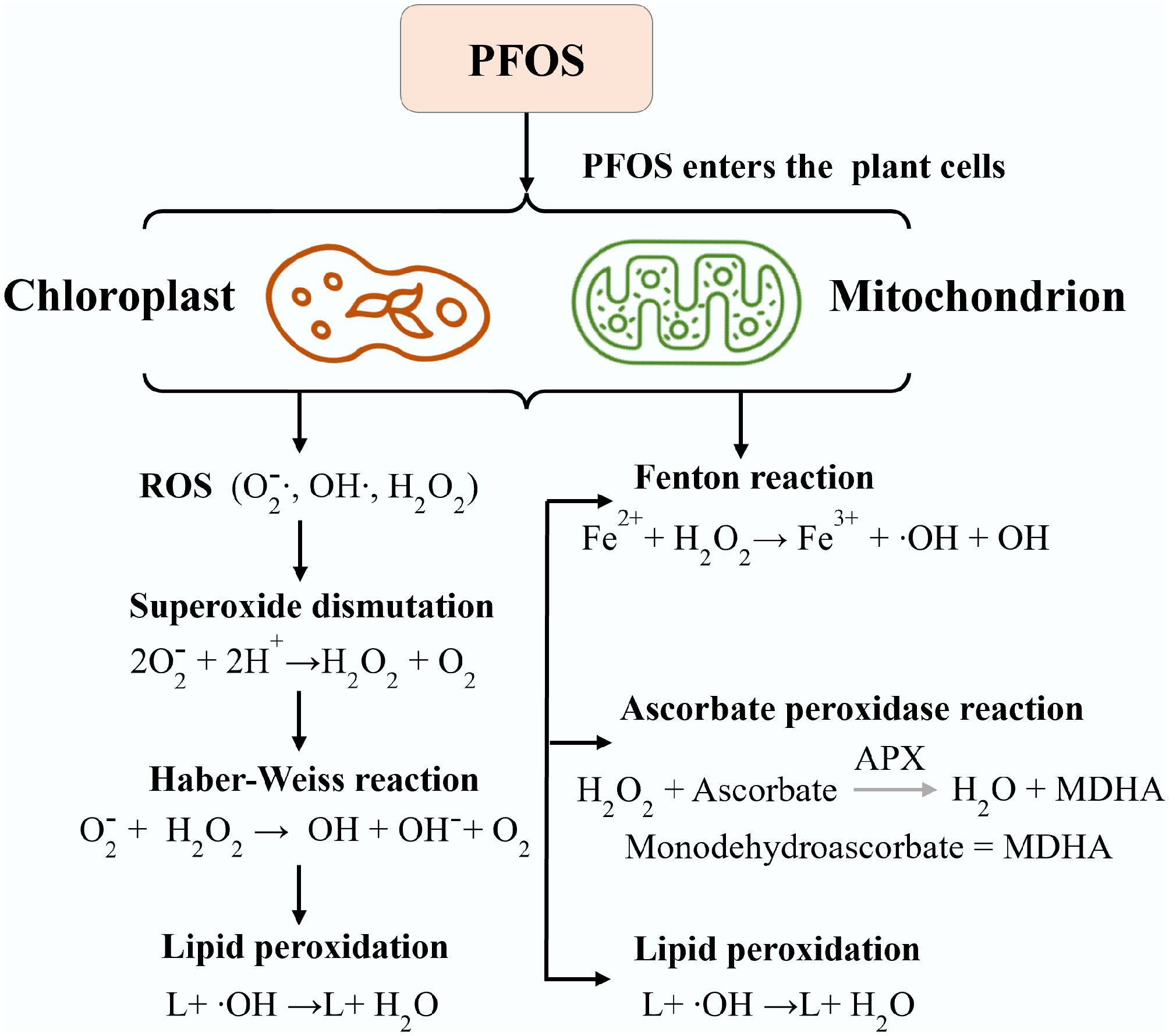

Global studies have shown that high concentrations of PFOS can destroy the antioxidant system in plants, severely damaging both leaf membranes and root cell structure[101]. PFOS can cause oxidative stress, chlorophyll loss, and impaired physiological growth, directly resulting in reduced crop yield. In Africa, severe nutrient deficiencies (N, P, K) already cause stunted growth and significantly reduced yields. Therefore, a plant already stressed by chronic nutrient starvation has a compromised defense system and is less resilient to the direct phytotoxicity stress (oxidative stress, metabolic disruption) caused by PFOS. Global studies on plant toxicity indicate that significant effects like decreased shoot weight are generally not seen below 50 mg/kg[102]. Long-chain PFAS (like PFOS) tend to remain in roots, with low accumulation levels in the above-ground plant tissues compared to short-chain PFAS (like PFOA). Common crops grown in Africa, like leafy greens (e.g., lettuce, spinach, kale, cabbage, and bananas) and legumes, have a higher risk of PFOS contamination due to their higher uptake potential and the environmental mobility of these compounds. The high uptake in leafy vegetables has also been linked to their large surface area and high transpiration rate. On the other hand, legumes (commonly grown by small-scale farmers in Africa) have a high protein and lipid content, which facilitates PFOS sorption, risking food safety in the event of pollution. Other crops common in agricultural lands in Africa, such as maize, wheat, rice, cassava, yams, potatoes, sweet potatoes, coffee, tea, cocoa, and cotton, are all at risk of PFOS contamination, as reported by Dalahmeh in Uganda. These plants can absorb PFOS from biosolids and irrigation water, leaving them more susceptible to the toxic effects of PFOS, further affecting their growth and yield. Global studies have also linked PFOS exposure to overproduction of ROS (Fig. 6), like superoxide (·O2–), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radicals (·OH–) in the soil and within plant tissues[102]. ROS are highly reactive molecules that can damage or modify the structure and functions of cellular plant components, including lipids, proteins, and DNA, and other nucleic acids. A global study found that PFOS induced oxidative stress in wheat, as evidenced by increased lipid peroxidation (49%) and upregulation of certain fatty acids and metabolites involved in stress responses[103]. Since plant membranes are primarily composed of phospholipids, glycolipids, and sterols, the accumulation of ROS can overwhelm the plant's antioxidant defenses, resulting in oxidative stress mainly in the mitochondria and chloroplast cells, which disrupts metabolic functions, including photosynthesis and respiration[41]. Furthermore, during lipid peroxidation, the decomposition of lipid hydroperoxides leads to the accumulation of toxic byproducts such as malondialdehyde (MDA), 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE), and other aldehydes that can crosslink proteins, DNA, and other cellular structures, leading to further oxidative damage and signaling stress responses.

Figure 6.

The reactions that occur in plants from the production of ROS to the resulting Fenton reaction.

The reactions involved in the production of ROS molecules in PFOS-contaminated plants and the resulting Fenton reactions (stress responses) are shown in Fig. 6. PFOS exposure has also been linked to influencing the availability of essential biological and physiological processes crucial for plant health, especially nitrogen cycling in the rhizosphere nutrient to plants. Since nitrogen is a vital nutrient for plant growth, its cycling involves complex interactions between plants and soil microorganisms. PFOS can adversely affect the activity of nitrogen-fixing bacteria and mycorrhizal fungi, which are essential for enhancing nutrient availability to plants, leading to nutrient deficiencies, stunted growth, and reduced agricultural productivity[80, 102, 104]. Research on wheat (Triticum aestivum) exposed to PFOS in soil has demonstrated several negative effects on plant health and development. These effects include a significant decrease in grain yield (34%), reduction in root biomass (37%), and lower chlorophyll a and b contents (49% and 41%, respectively). Furthermore, the study found that PFOS exposure led to decreased concentrations of essential nutrients such as magnesium (15%), phosphorus (14%), and potassium (14%) in the wheat tissues[105].

Moreover, the accumulation of PFOS in plant tissues can significantly alter their metabolomic profiles. Metabolomic changes often include shifts in the levels of important metabolites such as amino acids, sugars, and organic acids. For example, elevated levels of PFOS have been associated with altered concentrations of sugars and amino acids in various plant species[106]. These changes can impact not only the growth and development of the plants themselves but also their nutritional quality, ultimately affecting food security for human consumers. In maize and wheat, for example, exposure to PFOS resulted in decreased biomass and chlorophyll content[107,108]. Additionally, wetland plants exposed to PFOS showed reduced growth and reproductive success[29]. This has resulted in reduced crop yields and impaired productivity in herbivores that consume these plants, creating a pathway for PFOS to enter the food chain.

Effects on biogeochemical processes

-

PFOS has been shown to disrupt fundamental biogeochemical activities that are essential for maintaining soil health and ecosystem function, especially nitrogen cycling in the rhizosphere[109]. PFOS can have significant effects on key biogeochemical processes occurring in soil. Regarding the nitrogen cycle, PFOS has been shown to influence both nitrification and denitrification processes involved in the global nitrogen cycle[109]. A previous study on Lythrum salicaria and Phragmites communis in bulk soil suggested that low concentrations of PFOS (100 ng/g) might reduce nitrate nitrogen (NO3–-N) by 27.7% and ammonium nitrogen (NH4+-N) by 8.7%, indicating an initial impact on certain steps in the nitrogen cycle, while higher concentrations (50,000 ng/g) led to a major increase in the content of NO3–-N (by 1%) and NH4+-N (by 53.8%)[90]. In soil near plant roots contaminated with PFOS, the changes observed were different from those in the soil away from the roots and varied depending on the specific treatments applied. When PFOS levels were low, P. communis tended to increase nitrogen cycling while L. salicaria tended to decrease it. However, when PFOS concentrations were high, both plant types generally inhibited the soil's nitrogen cycle. Thus, the study concluded that the effect of PFOS on nitrogen transformation in the soil depends on the type of plant present.

According to previous work, an inversely U-shaped response was observed for potential nitrification rate, N2O emission rate, and denitrification rate in control, low, and high PFOS treatments of bulk soil (1.5, 3.0, and 1.1 mgN/[d·kg]; 0.01, 0.03, and 0.02 mgN/[d·kg]; and 0.19, 0.30, and 0.22 mgN/[d·kg]), respectively[98]. This response demonstrates the impact that PFOS has on ecological processes. Effectson microbial communities and on soil enzyme activities that are critical to soil function (e.g., nutrient cycling, decomposition) may occur at concentrations of less than 100 mg/kg for changes in bacterial diversity and 10 mg/kg for inhibition of enzyme activity. The abundance of specific genes involved in these nitrogen transformation processes can also be altered in the presence of PFOS[110]. Higher PFOS levels led to a decline in the archaeal amoA gene abundance, which is involved in nitrification, and a rise in bacterial amoA gene abundance, although the genes narG, nirK, nirS, and nosZ exhibited an inverted U-shaped response to increasing PFOS concentrations[98]. Furthermore, in the carbon cycle, PFOS has also been reported to inhibit the activity of glycoside hydrolases, which are enzymes involved in the breakdown of complex carbohydrates, thereby potentially disrupting carbohydrate metabolism in soil microbes[109]. The impact of PFOS on soil respiration, an indicator of overall microbial activity, has also been investigated. A study observed an initial enhancement followed by an inhibitory effect[90].

PFOS can also influence the cycling of other elements, such as sulfur, by affecting the abundance of bacteria involved in sulfate reduction[109]. Moreover, PFOS influences pH and TOC in the soil under different treatments[98]. In soils with low PFOS concentrations, the pH and TOC levels slightly rose by 0.3% and 1.1%, respectively, while in soils with high PFOS concentrations, the pH levels significantly increased by 61.8%, and TOC significantly decreased by 8.2%. Thus, understanding the effects of PFOS on biogeochemical processes is essential to understand its ecological risks in the soil–plant systems.

Biomagnification and trophic level transfer risks

-

PFOS enters terrestrial ecosystems primarily through contaminated soil, including via the application of biosolids from wastewater treatment plants, which can contain elevated PFAS levels. This contamination poses a direct pathway for human exposure through the diet, as PFOS can accumulate in the edible parts of various crops[80]. Plant species, soil/irrigation water quality, PFOS concentration level in the environment, chemical structure and polarity, and environmental conditions like soil carbon content, mineral content, and pH significantly influence plant uptake. Leafy vegetables, for instance, tend to accumulate higher concentrations than other crops, suggesting a greater public health risk associated with daily intake of these plants[80].

PFOS exhibits a strong potential for biomagnification within terrestrial food chains, meaning its concentration increases progressively at higher trophic levels[111]. Herbivores consuming contaminated plants or soil can accumulate PFOS in their tissues. Studies have documented this accumulation in various herbivores, including earthworms, mushrooms, bees foraging on contaminated nectar and pollen, and larger mammals like caribou and dairy cattle grazing on contaminated pastures[112]. A Swedish dairy farm study found elevated PFOS in cattle tissues (blood, liver, muscle) and reported muscle tissues showing the highest bio-transfer factors (BTFs) relative to daily intake, with log BTFs ranging from 1.95 to 1.15 d/kg[112]. As herbivores are consumed by higher trophic levels, PFOS biomagnifies through the food web, leading to substantially higher concentrations in predators[113]. Carnivores preying on contaminated herbivores accumulate even greater levels. Research in remote terrestrial food webs, such as the lichen-caribou-wolf chain in Arctic regions, demonstrates this biomagnification, with wolves as top predators exhibiting the highest PFOS concentrations. Significant trophic magnification factors (TMFs) for PFOS in these chains highlight its substantial biomagnification potential[114].

Case studies further illustrate PFOS accumulation in wildlife and its potential impacts. High PFOS levels have been found in the liver tissues of wolves and caribou in Northern Canada[111]. Honey bees exposed to PFOS accumulate it, negatively affecting their survival and reproduction[115]. Contamination incidents on dairy farms, such as in Maine, USA, show how soil PFOS contaminates crops, is taken up by livestock, and accumulates in milk and beef, impacting farm viability. The biomagnification of PFOS in terrestrial food chains has significant ecological implications, threatening wildlife health, potentially causing adverse effects on biodiversity, and contributing to ecosystem imbalances[85]. Even low levels of soil contamination can result in high concentrations in top predators, potentially affecting their health, reproductive success, and population dynamics.

Human exposure to PFOS occurs primarily through dietary intake of contaminated crops and animal products, posing significant health risks. High exposure levels have been linked to various adverse health effects, including liver damage, thyroid dysfunction, and increased cancer risk, specifically of the kidney, bladder, and prostate/testicular cancers[116,117]. Chronic exposure may also lead to developmental and reproductive disorders, immune suppression, and further carcinogenic effects[118]. Links between high serum PFOS levels and asthma[119] and type 1 diabetes[120] have also been reported. The persistence of PFOS in the human body, with a reported half-life of about four years[121], adds a layer of concern, particularly for communities reliant on local agriculture[122]. A study in South Africa found measurable PFOS concentrations in maternal serum (1.6 ng/mL) and cord blood (0.7 ng/mL)[123], indicating that PFOS exposure poses risks to human health beyond just its environmental presence.

-

The primary challenges in addressing PFOS pollution in Africa are the limited analytical capacity for monitoring PFAS in the environment and the high costs involved. The scarcity of advanced analytical methods, especially mass spectrometry (MS), which is crucial for precise detection and quantification, is a significant impediment to generating comprehensive data on the occurrence and trace levels of PFOS in soil–plant systems and other environmental matrices across the continent[124]. This has largely contributed to a pronounced geographical data gap, with only close to 10% of the 54 countries in Africa reporting PFOS contamination in the soil–plant system. Furthermore, many African countries lack adequately equipped laboratories and trained professionals with sufficient expertise in PFAS analysis, thus hindering thorough research. The acquisition and maintenance of sophisticated instruments (e.g., the triple quadrupole mass spectrometry) are prohibitively costly for many African universities and research organizations, further limiting extensive PFAS analysis. This results in variations in sampling techniques, analytical procedures, and compromised data accuracy, leading to limited environmental data and related public health risks. Additionally, there is minimal integration of large datasets with advanced analytical tools like machine learning, GIS, or spatial statistics for accurate, reliable, and interpretable models for mapping regional PFAS patterns and hotspot prediction[125].

In many African countries, there is inadequate wastewater treatment and waste management. The existing wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) were not designed to handle emerging contaminants like PFOS. These WWTPs often exhibit limited removal efficiency for PFOS. High PFOS levels have been reported in effluents (5.6 to 9.1 ng/L) compared to influents (3.4 to 5.1 ng/L) due to factors like desorption from biosolids or transformation of precursor compounds during treatment[125]. Additionally, poor waste management techniques, including improperly constructed landfills and the direct application of sewage sludge as fertilizer, contribute to the release of PFOS into the environment, increasing the risk of groundwater contamination. The illegal importation of products containing PFAS from developed countries also exacerbates the contamination problem, compounded by inadequate governance and ineffective legislation.

However, there is a lack of specific regulations and a general absence of specific guidelines or advisory levels for PFOS and other PFAS in the environment, with most African countries relying on broader environmental protection or chemical safety laws. Likewise, most African countries have adopted guideline limits set by international organizations and regulatory bodies from other regions, such as the United States Environmental Protection Agency[118], European Union (EU), Canada, China, and Australia. These standards may provide a benchmark for assessment, but they may not be applicable in the African context due to differences in environmental conditions, urbanization rates, waste management, agricultural practices, and dietary habits. Furthermore, poor governance and inadequate enforcement mean that while some countries, such as South Africa and Kenya, have made strides in developing regulatory measures, much of the continent still needs to align its policies with international frameworks like the Stockholm Convention. The absence of well-defined legislation and procedures hinders effective monitoring and management of PFOS pollution. Even with existing regulations, inadequate enforcement and a lack of awareness among stakeholders pose significant challenges.

Furthermore, poor governance across the continent and the inadequate enforcement of existing environmental regulations further contribute to the data scarcity and research gap, particularly compared to developed countries. This has led to a lack of awareness regarding the magnitude of the problem, identification of local hotspots, and formulation of effective mitigation strategies, thus contributing to scarce and inconsistent data on PFAS. Moreover, there is a lack of studies on the health effects of PFAS exposure and dose-effect relationships in the African context, which need to be explored.

To address these challenges and improve the understanding of PFOS contamination in Africa, this review recommends the following future outlook:

(1) Substantial investment in research and capacity building to overcome the shortage of mass spectrometry instruments and analytical tools in Africa. This includes investing in training programs to develop local professionals in MS technologies and machine learning, and fostering collaborations with international research institutes to increase funding for modern laboratory infrastructures. It is highly important to establish regional centers of excellence for PFAS monitoring using MS instruments to enhance the sensitivity and specificity of PFOS detection in the African soil ecosystem. Routine and comprehensive monitoring of both established and emerging PFAS compounds in hotspot areas like landfills, industrial zones, and WWTPs is essential to understand their origin, spatial and temporal trends, and their fate in the environment.

(2) Furthermore, fostering regional and international collaborations among scientists, policymakers, industry players, and communities is essential to mitigate the impact of PFAS in the African environment. These partnerships with foreign researchers can enhance expertise, share analytical techniques, and produce significant data on PFAS exposure. Moreover, community engagement is also crucial to boost environmental health literacy and influence waste management practices, which will ultimately reduce human and environmental exposure to PFOS.

(3) Research institutions and environmental agencies in African countries need to promote research and data sharing to comprehensively address PFOS contamination, including studies on other PFAS and next-generation PFAS. Researchers in Africa need to explore cost-effective water remediation techniques, such as agro-based adsorbents, to address treatment challenges.

(4) Developing robust data-sharing mechanisms and ensuring accessibility of findings to environmental and trade organizations and the public will raise awareness and promote informed decision-making. Future research should also focus on toxicity and epidemiological studies to evaluate ecological and human health risks.

(5) Future research should prioritize investigating the phytotoxicity of PFOS on human health, soil microbial activities, and African native plant species and crops under realistic environmental conditions unique to the region.

(6) Research should focus on developing and validating cost-effective and sustainable remediation strategies for PFOS-contaminated soil, water, and plants in the African context, including exploring the potential of phytoremediation using native African plant species to provide a long-term treatment solution.

(7) African governments should strengthen their regulatory frameworks and ensure enforcement of national and regional regulations and guidelines for PFOS and other PFAS in soil, water, and plants, considering international standards and the specific context of African ecosystems and human health. This includes incorporating PFAS into existing regulatory frameworks under conventions like the Stockholm Convention and developing national standards for PFAS monitoring based on international guidelines. Stronger enforcement of these regulations and the development of specific guidelines for permissible PFAS levels in various environmental matrices, including sludge and soil, are vital. Policymakers should also prioritize cooperation and resource sharing to achieve comprehensive sustainability goals.

-

This review study concludes that PFOS is present in soil–plant systems across Africa, although generally at lower levels compared to more industrialized regions like China, the European Union, and the United States, except for certain regions in Ghana and South Africa. Localized contamination hotspots, particularly urbanized and industrial areas, contaminated biosolids and irrigation water, polluted water channels, waste disposal and electronic waste sites, exhibit significantly higher concentrations; thus, frequent monitoring and research are needed. The limited availability of advanced analytical equipment in Africa likely contributes to an underestimation of the full extent of PFOS contamination in the environment. This research further points out that PFOS can be taken up by plants common to Africa, such as medicinal plants, agricultural plants (maize, wheat, rice, sugarcane, bananas, leafy vegetables), and wetland plants (reeds) can take up PFOS, though at low levels compared to plants in other regions globally. This raises an alarm for further research and monitoring to reveal the extent of contamination, especially in agricultural crops. Given the rising economic growth, industrialization, and agricultural production in Africa, pollution of PFAS is predicted to further grow. There is an urgent need for capacity building, regional coordinated research, and integration of machine learning techniques and GIS to increase detection and monitoring programs, development of strict region-specific regulatory frameworks, and investment in modern laboratory infrastructures and innovative remediation technologies to address this underlying threat on the continent.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/newcontam-0025-0015.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Oginga B, Ibrahim A, Qin C, Gao Y; methodology: Oginga B, Gudda FO, Li Z; investigation: Oginga B, Gudda FO, Ibrahim A, Li Z; validation: Ibrahim A; data curation: Oginga B; draft manuscript preparation: Oginga B; writing − review and editing: Oginga B, Gudda FO, Li Z, Minkina T, Qin C, Gao Y; supervision: Qin C, Gao Y; funding acquisition: Qin C; project administration: Qin C. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data analyzed in this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

-

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant Nos 2023YFE0110800, 2023YFC3708103), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 42477419, 42107221, 42430703, U22A20590), and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2023M741738).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Maximum PFOS in African soils and plants: 275.3 and 29.33 ng/g, respectively.

PFOS in Ghana and South Africa soil pose significant threats via soil–plant translocation.

PFOS accumulation in Africa is dominant in surface soil and present in agricultural crops.

The accumulation of PFOS in plant tissues can significantly alter their metabolomic profiles.

African governments need to collaborate to address PFOS pollution in soil–plant systems.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Bonface Oginga, Fredrick Owino Gudda

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - The supplementary files can be downloaded from here.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Oginga B, Gudda FO, Ibrahim A, Li Z, Minkina T, et al. 2025. Perflourooctane sulfonate in soil–plant systems in Africa: occurrence and ecological risks. New Contaminants 1: e015 doi: 10.48130/newcontam-0025-0015

Perflourooctane sulfonate in soil–plant systems in Africa: occurrence and ecological risks

- Received: 20 August 2025

- Revised: 10 November 2025

- Accepted: 19 November 2025

- Published online: 05 December 2025

Abstract: Perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), with bio-accumulative and toxic properties, has been detected in various environmental matrices. In Africa, industrialization and agricultural yields are respectively projected to increase by 16% and 23% by 2043. This will further increase PFOS pollution risks, yet there is limited research in this domain to quantify its potential health risks. Since the soil–plant system is a critical pathway for PFOS to cause health risks, it is important to investigate the fate and transfer of PFOS in the system. This review synthesizes evidence on PFOS occurrence in African soils and plants, uptake mechanisms, and ecological impacts. PFOS sources include industrial discharges, electronic wastes (e-waste), and wastewater irrigation. These soil levels, particularly in Ghana and South Africa, pose significant threats to human health via soil–plant translocation. Sewage sludge in Ghana was found to have high levels of PFOS (197 to over 200 ng/g dw), exceeding recommended levels set by other developed countries like the United Kingdom (46 ng/g dw). This specific sewage sludge poses a significant threat when applied to agricultural land. Soil data from 11 locations in Africa were retrieved, and sites in Africa, with the highest recorded soil concentration being 275.3 ng/g (Ghana). Hotspot countries include Ghana (275 ng/g) and South Africa (248.14 ng/g). In plants, six samples were retrieved and analyzed, with 29.33 ng/g (Kenya) being the highest concentration. The soil–plant concentration ratio was 6.815. Plant uptake varies by species, with agricultural crops common to Africa like sugarcane, yams, and maize cobs, found to accumulate PFOS in their kernels, although at low levels compared to crops studied in other developed regions. Leafy vegetables are the most dominant in terms of plant uptake of these chemicals, showing higher accumulation in their foliage systems. A knowledge gap exists in Africa to understand the extent of soil and plant contamination and associated risks. This is contributed to by the lack of capacity and investment in research and monitoring programs targeting emerging contaminants in the region. The urgent need is stressed to build capacity, establish regional regulations, promote advanced research and monitoring, incorporating machine learning techniques and remedial strategies to tackle this challenge.

-

Key words:

- PFOS /

- Soil–plant systems /

- Occurrence /

- Bioaccumulation /

- Ecological risks /

- Africa