-

Currently, microplastics (MPs) are ubiquitous in different aquatic systems, including oceans, rivers, lakes, and reservoirs, with high concentrations (over 1,000 particles/L)[1,2]. With long-term contact with water accompanied by extensive exposure to solar irradiation, dissolved organic matter can be released from MPs into aquatic environments as microplastic-derived dissolved organic matter (MPs-DOM). Consequently, MPs-DOM is ubiquitous in natural surface waters and susceptible to light conditions particularly to ultraviolet (UV) irradiation, which contributes up to 10% of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) in the top microlayer in severely polluted regions[3]. Considering the immense and incremental plastic production that leads to a continual disposal of MPs, MPs-DOM is constantly derived and released; thus, it can be hypothesized that the composition and properties of MPs-DOM may be distinct over the derivation processes, thereby leading to diverse environmental impacts.

UV irradiation is ubiquitous in surface water systems and water treatment processes, which is considered the trigger for the derivation of MPs-DOM. In comparison with the dark condition, UV irradiation may enhance the leaching of additives which act as critical protective components of plastic materials, and facilitate the release of MPs-DOM in the form of monomers and oligomers as well as oxidized intermediates[4]. Furthermore, extra oxygen-containing functional groups (OFGs) can be formed in MPs-DOM[5,6]. However, current studies mainly focused on the final derivation state of MPs-DOM, and a knowledge gap still exists regarding the dynamics of molecular composition of MPs-DOM during the derivation processes.

MPs detected in aquatic environments span a wide range of synthetic polymer types; for instance, polyethylene (PE) and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) are among those that occur most frequently[7,8]. As promising substitutes for the conventional petroleum-based plastics, biodegradable plastics have been proposed, and their global production capacity is constantly increasing, dominated by polylactic acid (PLA) and polybutylene adipate-co-terephthalate (PBAT)[9,10]. Different types of polymers may differ in the DOC amount and molecular composition of MPs-DOM[11]. In comparison with aromatic MPs (such as PET and PBAT), aliphatic MPs (such as PE and PLA) tend to release additives more rapidly, leading to an intensive photodegradation[12,13]. Biodegradable plastics may release extra MPs-DOM in comparison with conventional petroleum-based plastics due to the fragile backbone of the polymer[14]. MPs-DOM originating from different types of MPs may exert varying influence on the aquatic system; therefore, it is necessary to reveal the specific features of MPs-DOM derivation kinetics based on different polymer types, such as aromatic vs aliphatic MPs, and/or conventional vs biodegradable MPs.

As an emerging anthropogenic component of dissolved organic matter in aquatic environments, MPs-DOM is characterized by a low-molecular-weight, a low degree of aromaticity and humification, and greater bio-lability, which may significantly differ from natural organic matter derived DOM (N-DOM)[15,16]. Thus, it is critical to distinguish the molecular features and derivation dynamics of MPs-DOM from those of natural origins to precisely investigate the relevant environmental implication.

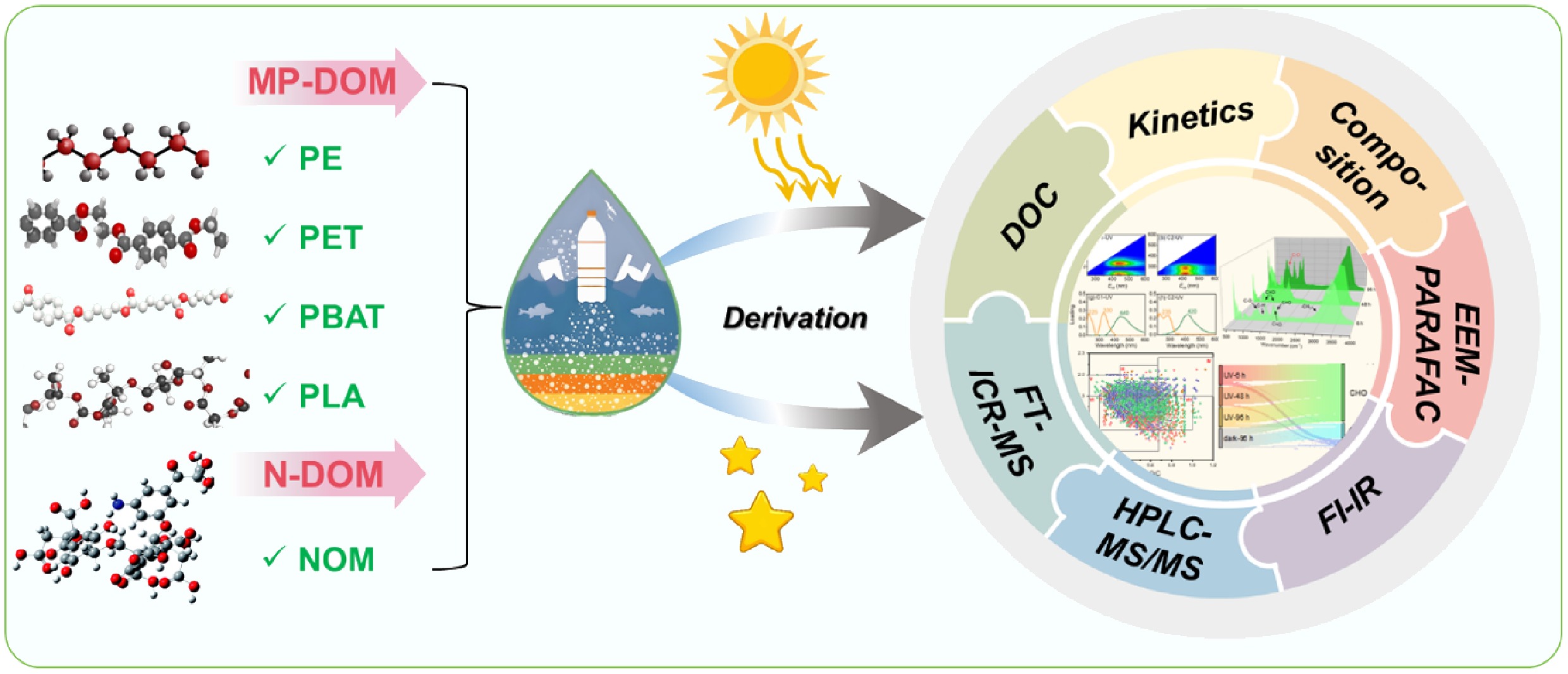

Therefore, PE, PET, PBAT, PLA MPs, and Suwannee River NOM were selected to derive MPs-DOM and N-DOM, respectively, with the aims to: (1) investigate the derivation kinetics of MPs-DOM and N-DOM; (2) characterize the molecular-level dynamics of MPs-DOM in comparison with N-DOM; and (3) discuss the potential environmental implications of MPs-DOM.

-

PE, PET, PLA, and PBAT microplastic polymers were purchased from Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The particle size of the MPs was in the range of 13–74 μm. NOM isolated from the Suwannee River was purchased from the International Humic Substances Society (IHSS) serving as a widely used reference material for NOM in aquatic systems[17].

Derivation experiment setup

-

To derive MPs-DOM, 3.0 g of microplastic samples each of PE, PET, PLA, and PBAT were separately added into 600 mL of ultrapure water in a quartz reactor with a magnetic stirrer and conducted in the dark and under UV irradiation (50 W mercury lamp), respectively, the temperature was maintained at 25 ± 1 °C, the samples were collected at 6, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h and were thereafter filtered by Whatman GF/F membranes (GE Whatman, UK), which were pre-washed with ultrapure water and pre-combusted at 450 °C for 5 h. The filtrates were stored in glass bottles in the dark at 4 °C for further analysis. All the experiments were performed in triplicate. The details are given in the Supplementary Text S1.

Characterization and kinetic models

-

Dissolved organic carbon (DOC) concentrations in the samples were determined using a total organic carbon analyzer (SHIMADZU TOC-V CPN, Japan). The release of MPs-DOM was hypothesized to be a desorption process, and zero-order, pseudo-first-order, pseudo-second-order, interparticle diffusion, and Boyd models were employed to fit the data of DOC for the derivation kinetics of MPs-DOM (Supplementary Table S1). The samples of MPs-DOM and N-DOM were adjusted to the same condition, i.e., a concentration of 10 mg-C/L with pH = 7.0 ± 0.1 to obtain fluorescence excitation emission matrices using a fluorescence spectrophotometer F-2700 (HITACHI, Japan). EEM-PARAFAC was performed using the DOMFluor toolbox[18]. To investigate the variation in functional groups of the samples, ATR-FT-IR (Nicolet NEXUS 670, ThermoFisher, USA) was conducted over a range of 400–4,000 cm–1. The additives in MPs-DOM were determined using an HPLC-MS/MS (Thermo Scientific, Orbitrap Exploris 120). To obtain information on molecular formulas, MPs-DOM and N-DOM were analyzed using electrospray ionization Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (ESI FT-ICR-MS) (Arix 2xR 7.0T) in negative ion mode. The details are given in the Supplementary Text S1, Supplementary Tables S2, Table S3.

-

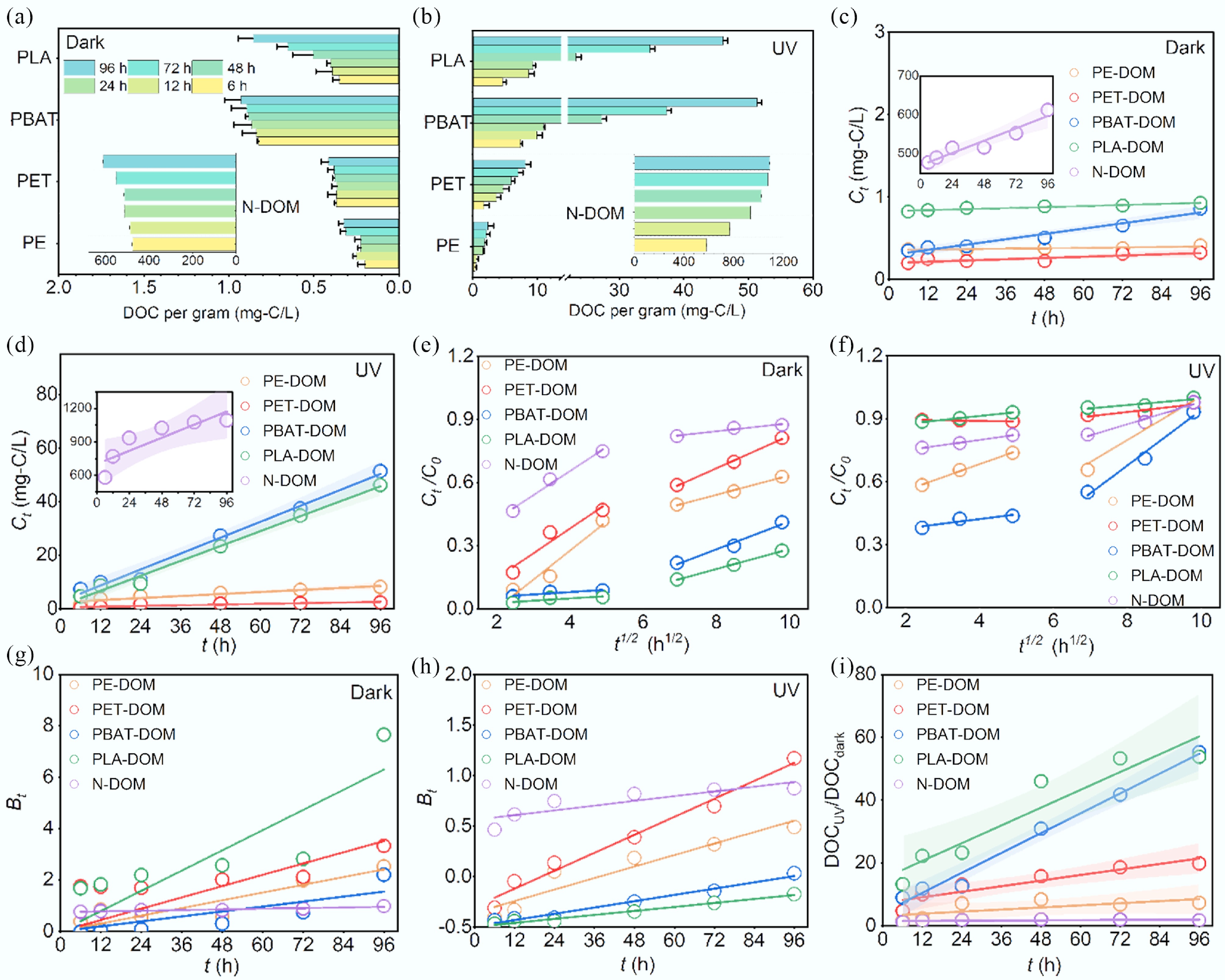

In the dark condition, the data on DOC per gram of MPs or NOM shared a similar pattern as the value increased along with derivation time (Fig. 1a). The DOC concentration of N-DOM was significantly higher than that of MPs-DOM (p < 0.01). Biodegradable MPs tended to release more DOC than conventional MPs (p < 0.01). The experimental kinetic data can be well fit by zero-order and pseudo-second-order kinetic models (p < 0.01) (Fig. 1c; Supplementary Fig. S1c, Supplementary Table S4), indicating that the DOC derivation rate of N-DOM exceeded that of MPs-DOM. The intraparticle diffusion model showed that the plots could be divided into two linear segments (Fig. 1e), corresponding to intraparticle diffusion and film diffusion, respectively. The slope (kp) generally increased (Supplementary Table S4), implying the film diffusion rate accelerated. The Boyt model (Fig. 1g) showed that Bt was linearly correlated with t (p < 0.01), and the plots passed through the origin for MPs-DOM (Supplementary Table S4), suggesting that the intraparticle diffusion was the rate-limiting step; however, it was not the case for N-DOM, which was controlled by film diffusion. UV irradiation significantly enhanced the derivation of DOC for both MPs-DOM and N-DOM (Fig. 1b). The zero-order kinetic model also fitted the experimental data well (p < 0.01) (Fig. 1d; Supplementary Table S4), suggesting that UV greatly enhanced the DOC derivation rate of MPs-DOM, in particular for biodegradable MPs. The rate of zero-order reaction is independent of the concentration of reactants and is equal to the rate constant, commonly occurring under conditions where only a limited fraction of the reactant molecules is ready to react, and can be continually replenished from a large pool. Accordingly, the derivation kinetics of MPs-DOM may be constant under specific conditions, relying on the internal properties of MPs (e.g., polymer type, specific surface area) and external factors (e.g., irradiation conditions) rather than the concentrations of MPs. The intraparticle diffusion model (Fig. 1f) showed that kp2 > kp1 for all the data except for PLA-DOM in which kp2 was close to kp1 (Supplementary Table S4). The Boyt model demonstrated that none of the plots passed through the origin (Fig. 1h; Supplementary Table S4); thus, the film diffusion predominated the derivation processes of both MPs-DOM and N-DOM.

Figure 1.

Derivation kinetics of MPs-DOM and N-DOM with the treatment under dark and UV irradiation conditions. (a), (b) DOC; (c), (d) zero-order kinetic model; (e), (f) intraparticle diffusion kinetic model; (g), (h) Boyd film diffusion kinetic model; and (i) the DOCUV/DOCdark ratio.

The DOCUV/DOCdark ratio was utilized to investigate the contribution of UV irradiation to DOC leaching (Fig. 1i). For MPs-DOM, the DOCUV/DOCdark ratio was significantly linearly correlated with time (p < 0.01) except for PE (p > 0.05), and the slope followed the order as kPBAT (0.526) > kPLA (0.472) > kPET (0.147) > kPE (0.056) > kNOM (0.005) (Supplementary Table S5), which further confirm that the derivation of MPs-DOM can be enhanced by UV irradiation, however, UV did not alter the derivation of N-DOM. Furthermore, aromatic MPs tended to leach more DOC in comparison to aliphatic MPs due to a greater content of additives[16], while biodegradable MPs were likely to undergo photodegradation to produce extra soluble molecules (e.g., oligomers); thus, they may release and contribute extra DOC to aquatic environments compared with conventional MPs[10,19]. Additionally, UV irradiation also facilitated the leaching of additives, which may further promote the degradation of MPs and the release of MPs-DOM[5]. Thus, UV irradiation is an essential factor governing the derivation of MPs-DOM.

Variation of functional groups during the derivation processes based on FT-IR

-

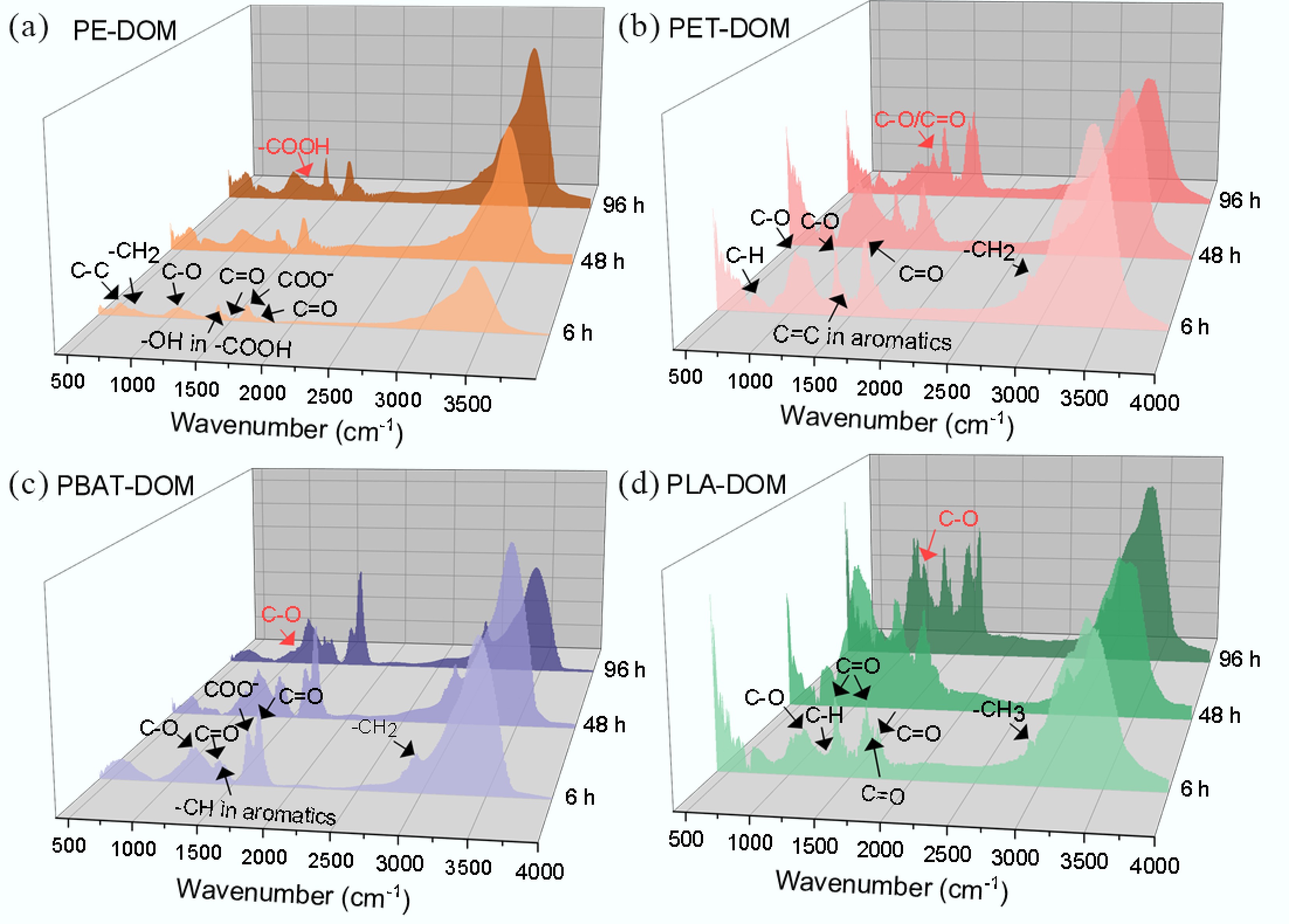

FT-IR was conducted to identify the functional groups of the DOM samples. The results (Fig. 2; Supplementary Table S6, Supplementary Fig. S2) demonstrated that for PE-DOM, the peaks corresponding to the aliphatic carbon skeleton (C–C at 663 cm–1, –CH2 at 710 cm–1) strengthened during the derivation process. OFGs, such as C–O (1,066 cm–1), –COOH (1,402 cm–1), –COO– (1,402, 1,550 cm–1), C=O in unsaturated structures (1,630 cm–1) and saturated aliphatic (1,700, 1,751 cm–1) also increased in intensity, accompanied by the emergence of a peak assigned to C–O in –COOH at 1,265 cm–1. In PLA-DOM, the peaks associated with the aliphatic carbon chain (–CH at 1,130 cm−1 and –CH3 at 2,940 cm−1) elevated, likewise, OFGs including C=O (1,400, 1,620, 1,650, and 1,750 cm–1) did so, while the peaks assigned to C–O (1,030, 1,070 cm–1) shifted and a new one corresponding to –OH formed at 1,190 cm–1. For PET-DOM, the peaks ascribed to –C–H (731 cm–1), –CH2 (731, 2,960 cm–1), C=C in aromatic rings (1,510, 1,650 cm–1), C–O (1,060 cm–1), and C–O/C=O in COO– (1,400, 1,650 cm–1) amplified. In PBAT-DOM, the peaks located at 1,210 cm–1 (C–O), 1,400 cm–1 (C=O), 1,440 cm–1 (–CH, aromatic ring), 1,630 cm–1 (C=O/COO–), 1,730 cm–1 (C=O), and 2,960 cm–1 (–CH2) increased in intensity, and a peak emerged at 1,080 cm–1 (C–O). These results suggested that the monomer and/or oligomers of MPs were produced and released under UV irradiation leading to the enhancement of peaks corresponding to the aliphatic carbon chain and/or the aromatic structures, while OFGs were generated via the reactions, including hydrolysis and Norrish reactions[20−22]. Additionally, phthalates as an essential type of additives in plastics, including dibutyl phthalate, dipentyl phthalate, bis(2-methoxyethyl) phthalate and dimethyl phthalate were detected in MPs-DOM by HPLC-MS/MS (Supplementary Fig. S3), and the peaks related to phthalates emerged and/or strengthened in FT-IR (Supplementary Table S6), due to the fact that the additives are commonly not covalently bonded to the polymer structures[23]. MP-DOM may also show properties of light absorption and photoactivity due to the presence of a variety of additives, aromatic structures, and oxygen-containing functional groups, which can be further revealed via spectral methods, such as UV-vis and fluorescence spectroscopy.

Figure 2.

FT-IR spectra of MPs-DOM during UV derivation. (a) PE-DOM; (b) PET-DOM; (c) PBAT-DOM; (d) PLA-DOM.

Variation of the components during the derivation processes based on EEM-PARAFAC

-

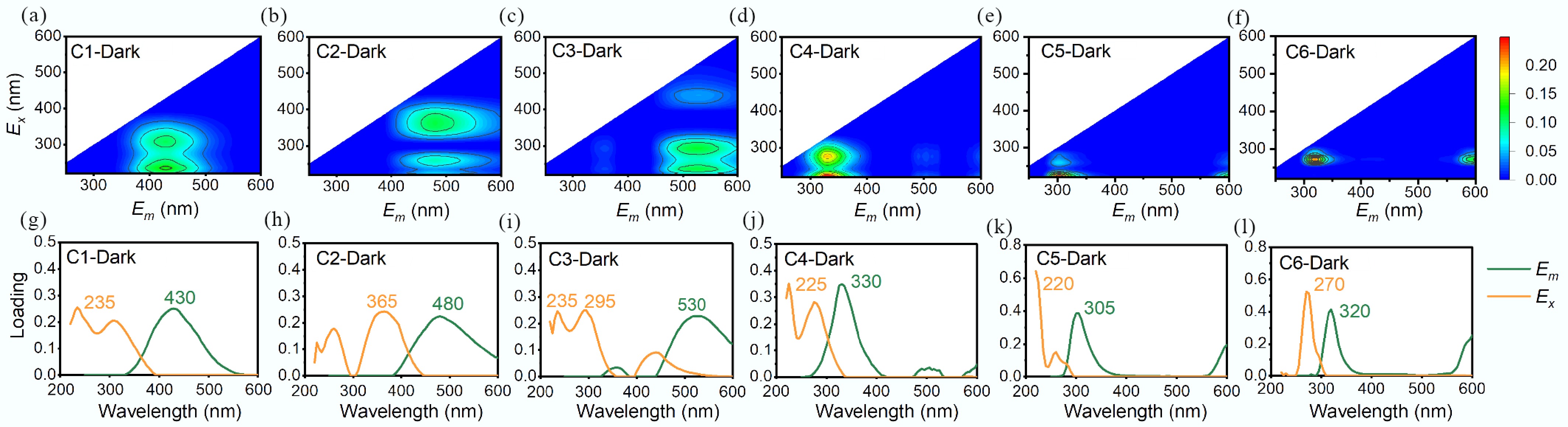

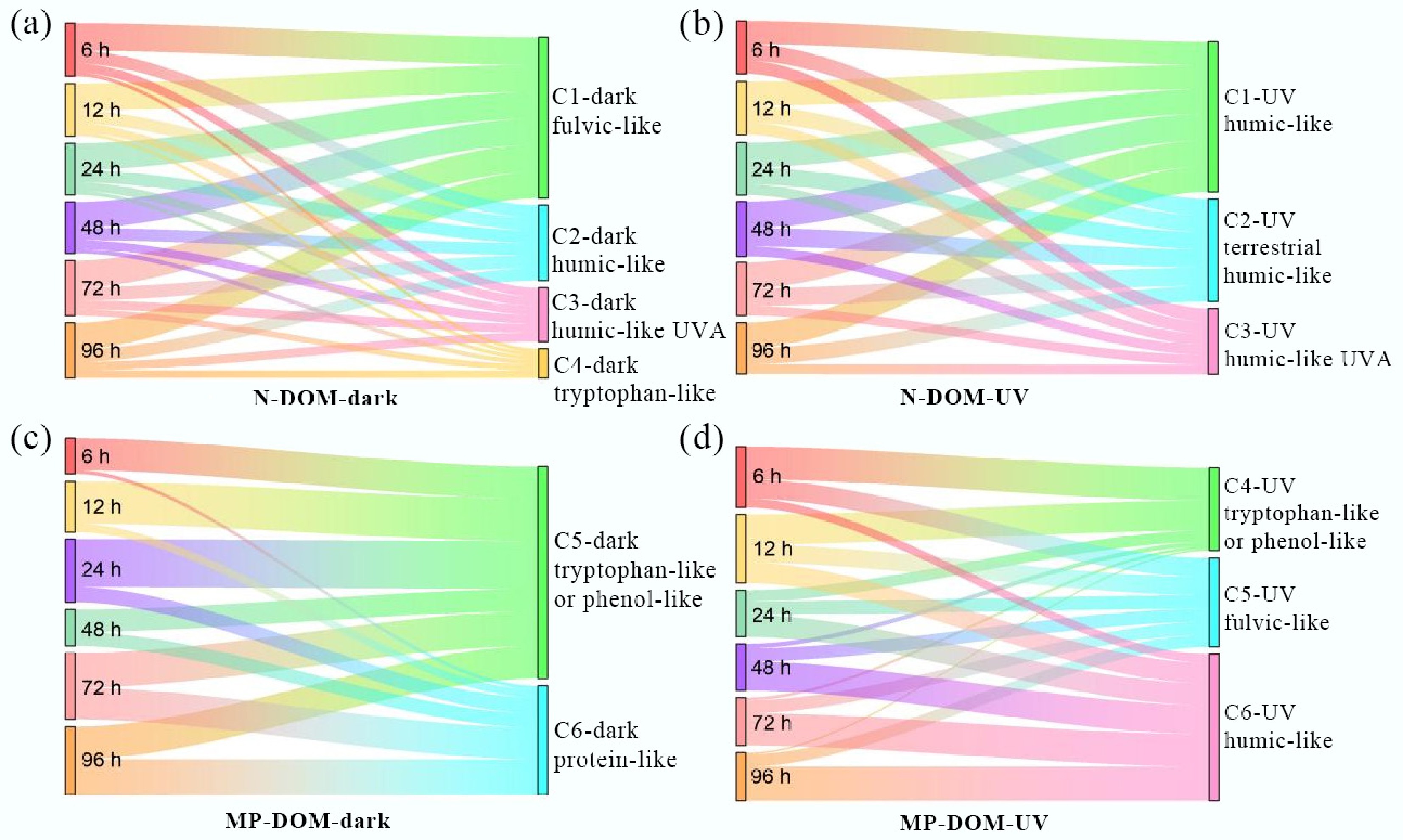

EEM-PARAFAC was applied to probe the derivation dynamics of DOM[24,25]. A total of 180 fluorescence EEMs of MPs-DOM and N-DOM were subjected to PARAFAC, all the fluorescence EEMs except for PLA-DOM were successfully deconvoluted (Fig. 3, 4; Supplementary Figs S4, S5, Supplementary Tables S7, S8). Under dark treatment, four components were identified in N-DOM, including terrestrial humic-like (C1-Dark, Fig. 3a, g), the humic acid-like (C2-Dark, Fig. 3b, h), the autochthonous fulvic-like (C3-Dark, Fig. 3c, i), and the protein-like/phenols (C4-Dark, Fig. 3d, j) substances. MPs-DOM included components associated with additives in MPs (C5-Dark, Fig. 3e, k) and tyrosine-like substances (C6-Dark, Fig. 3f, l). Fmax (Fig. 5a) of different components in N-DOM remained stable during the derivation processes, dominated by C1-Dark, whereas for MPs-DOM (Fig. 5c), the percentage of C5-Dark declined from 89% to 48%, accompanied by a corresponding rise in C6-Dark.

Figure 3.

EEM-PARAFAC contour plots and loadings of excitation and emission wavelengths of MPs-DOM and N-DOM derived in the dark condition.

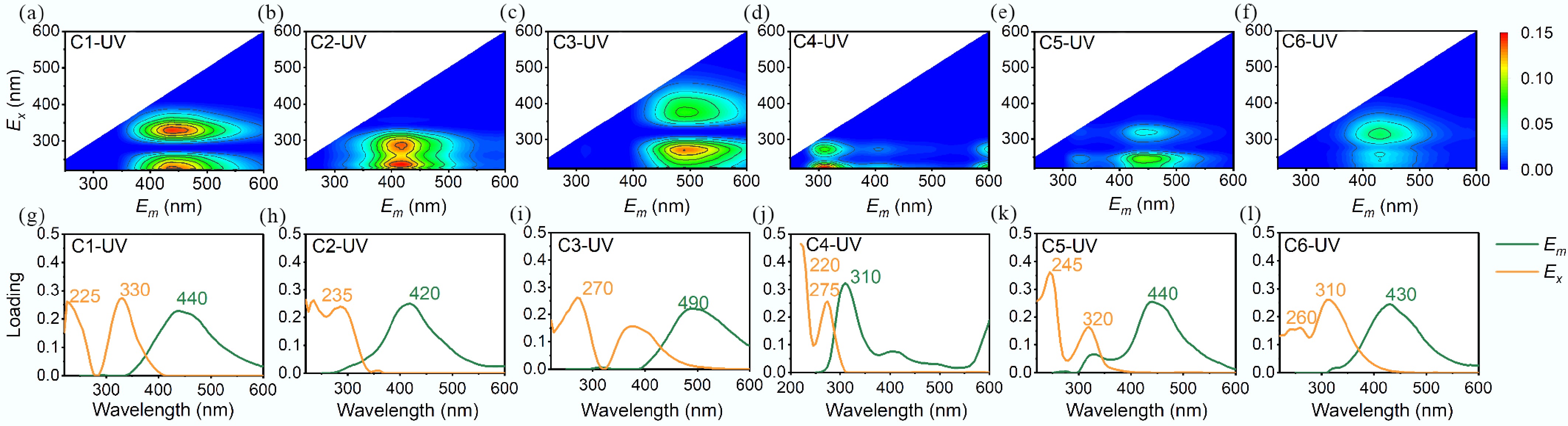

Under UV irradiation, three components were obtained in N-DOM, including fulvic-like acids (C1-UV, Fig. 4a, g), the terrestrial humic-like components with high-molecular-weight (C2-UV, Fig. 4b, h), and the terrestrial humic-like components with low-molecular-weight aromatic terrigenous structures (C3-UV, Fig. 4c, i)[26,27]. MPs-DOM included the tyrosine-like fluorescent compounds (C4-UV, Fig. 4d, j), the typical allochthonous fulvic/humic-like substances (C5-UV, Fig. 4e, k), and UVA low-molecular-weight humic-like substances associated with biological activity (C6-UV, Fig. 4f, l)[28]. During the derivation processes, Fmax (Fig. 5b) was generally stable for N-DOM governed by C1-UV, for MPs-DOM, Fmax of C4-UV dropped dramatically from 54% to 3% with an increase in C6-UV of 56% (Fig. 5d).

Figure 4.

EEM-PARAFAC contour plots and loadings of excitation and emission wavelengths of MPs-DOM and N-DOM derived under UV irradiation.

Figure 5.

Relative proportions of Fmax of each component during the derivation process. (a) N-DOM in dark; (b) N-DOM under UV irradiation; (c) MPs-DOM in dark; (d) MPs-DOM under UV irradiation.

Indices based on EEMs were also investigated to reflect the composition of DOM. The Fluorescence index (FI) is an indicator to distinguish DOM derived from terrestrial origins (around 1.2) from that derived from microbial activities (around 1.8)[29]. The FI values (Supplementary Fig. S6a, S6b) fluctuated around 1.8 for MPs-DOM with both dark and UV treatment, except for PE-DOM in the dark (< 1.2), indicating that MPs-DOM was generally in line with DOM derived from microbial activities. For N-DOM, FI remained stable at approximately 1.2 under both treatments, suggesting the domination of terrestrial origins. BIX is associated with recent autochthonous contribution to DOM; the values of MPs-DOM varied from 0.11 to 1.72 under dark treatment and 0.11 to 1.93 under UV irradiation, which were significantly (p < 0.01) lower than the values of N-DOM (> 2.0) (Supplementary Fig. S6e, S6f), indicating a significant difference in the autochthonous component between MPs-DOM and N-DOM[30]. HIX, an indicators reflecting the aromatic degree, increased for MPs-DOM under both conditions (Supplementary Fig. S6c, S6d), indicating that the release of soluble aromatic structures from MPs increased during the derivation processes; however, the humic character may still be at a weak level due to the low values of HIX (< 4), whereas N-DOM showed a strong humic character, and the HIX values declined with the derivation time, which may be attributed to the re-adsorption of these components[31,32].

Variation of molecular compositions during the derivation processes based on FT-ICR-MS

-

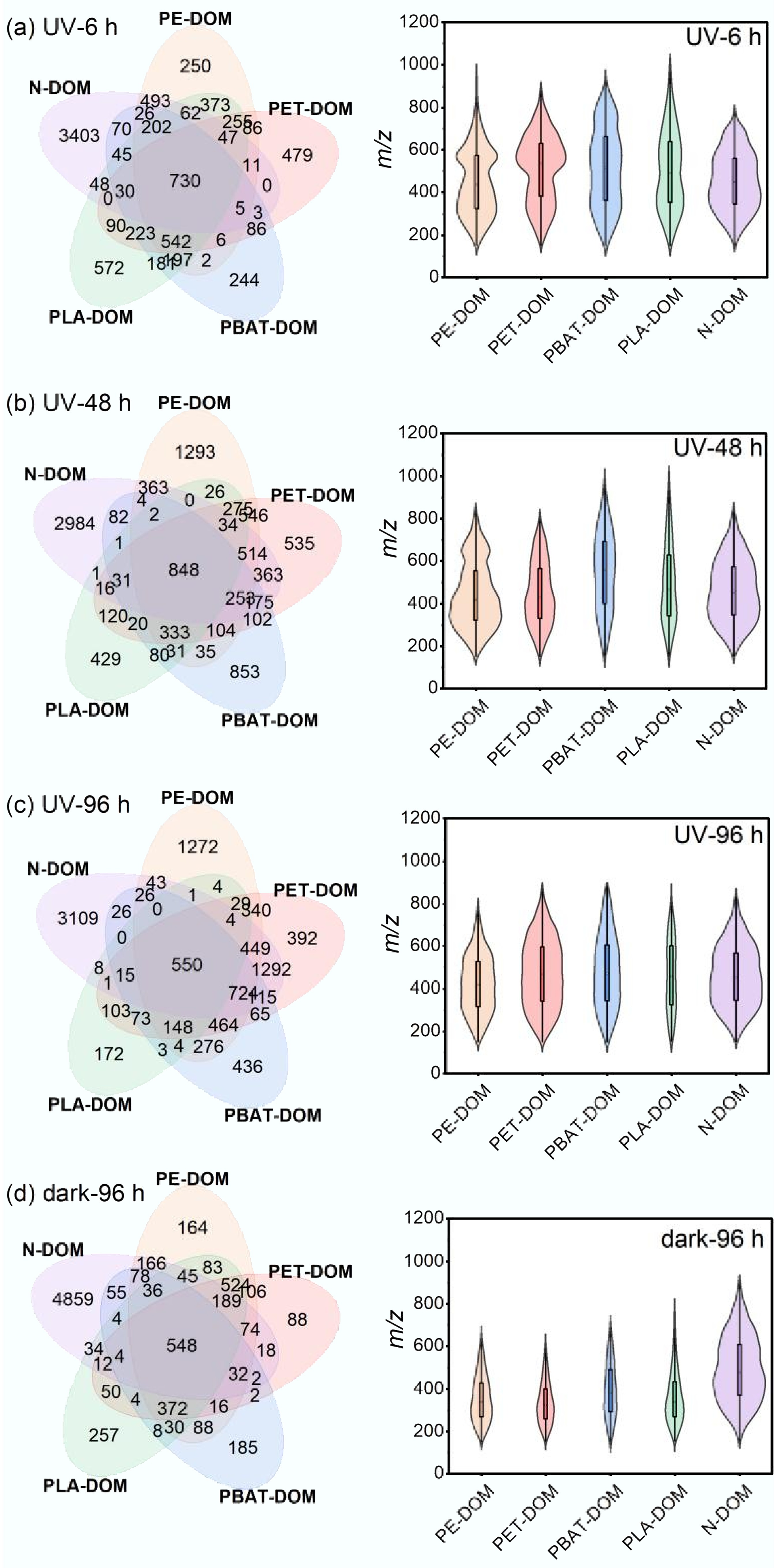

The molecular-level composition of MP-DOM and N-DOM during the derivation processes were profiled by FT-ICR-MS. The Venn diagram (Fig. 6) showed that in comparison with dark treatment for 96 h, UV significantly increased the number of identified formulas of MPs-DOM with the same duration, and the number increased constantly with the exposure time, except for PLA-DOM; moreover, N-DOM contained many more molecules than MPs-DOM with both treatments. During the derivation processes, the highest number of unique molecules was found in N-DOM, and the number declined slightly by 8.64%; for MPs-DOM, PE-DOM exhibited the most unique features, and the number increased significantly from 250 to 1,272. The similarity between MPs-DOM and N-DOM weakened during these processes, as the number of shared formulas decreased from 730 at 6 h to 550 at 96 h, whereas the similarity between aromatic MPs-DOM and N-DOM enhanced, with the number of shared formulas increasing from 1,480 to 3,150 for PET-DOM and from 1,111 to 1,456 for PBAT-DOM. A significant difference in m/z between MPs-DOM and N-DOM was also observed (p < 0.01). UV significantly elevated the m/z of MPs-DOM but lowered the m/z of N-DOM (p < 0.01). The distribution of m/z fluctuated significantly during the derivation (p < 0.05); m/z varied widely over the range of 150–1,000 for MPs-DOM but within 150–850 for N-DOM; the average m/z increased for both conventional MPs-DOM and N-DOM, while it decreased for biodegradable MPs-DOM (Fig. 6; Supplementary Table S9).

Figure 6.

Venn diagrams of molecular formulas and distribution of m/z values during UV derivation. (a) 6 h under UV irradiation; (b) 48 h under UV irradiation; (c) 96 h under UV irradiation; (d) 96 h in dark.

To explore the specific molecular alteration during derivation, the formulas were categorized into photo-resistant (molecules detected at different derivation times) and photo-reactive (the molecules related to the photoreaction as either reactants or products) groups.

Based on their elemental composition, the molecular formulas were classified into four groups as CHO, CHON, CHOS, and CHONS (Supplementary Fig. S7). During the UV derivation processes, the distribution of the subcategories showed diverse patterns among different types of MPs-DOM. The proportion of CHO peaked in PET-DOM and PBAT-DOM with limited fluctuation (< 5%), but decreased by 19.4% in PE-DOM and increased by 12.7% in PLA-DOM. The proportion of CHON increased in PE-DOM, PET-DOM, and PBAT-DOM by 35.4%, 46.1%, and 12.4%, respectively, but remained stable in PLA-DOM. The proportions of both CHOS and CHONS in MPs-DOM, which contain heteroatoms derived from additives in MPs, decreased constantly, especially for aromatic MPs-DOM[33]. The relative abundance of each group was generally stable in N-DOM. For the photo-resistant group, the molecular formulas only included CHO and CHON. CHON was the major component in PE-DOM (75.7%), whereas the others were dominated by CHO, accounting for over 65%. Under dark treatment, CHON was the main photo-reactive subcategory in MPs-DOM (generally > 50%); under UV irradiation, CHON was still the major component in conventional MPs-DOM, but CHO became the leading one in biodegradable MPs-DOM.

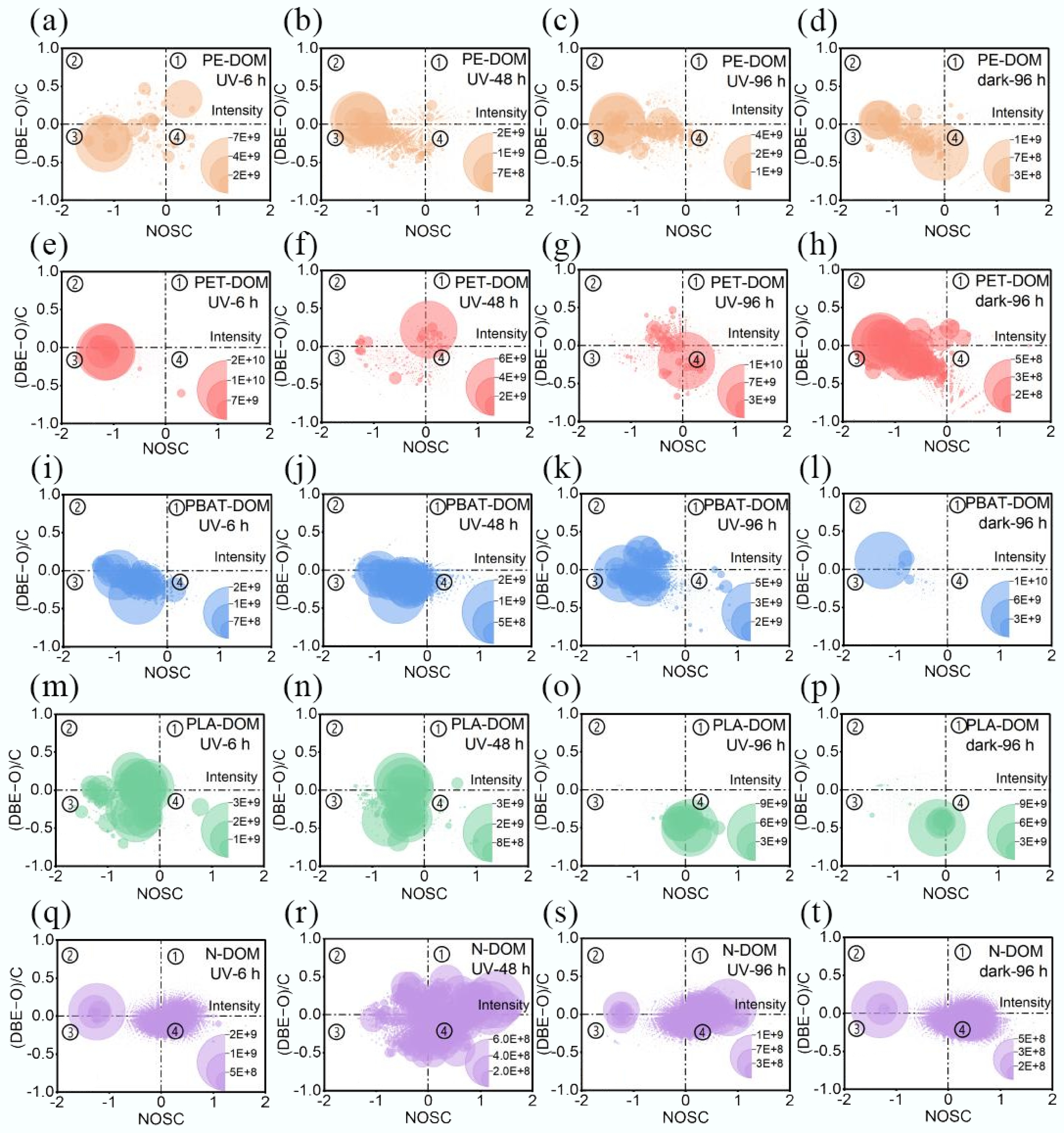

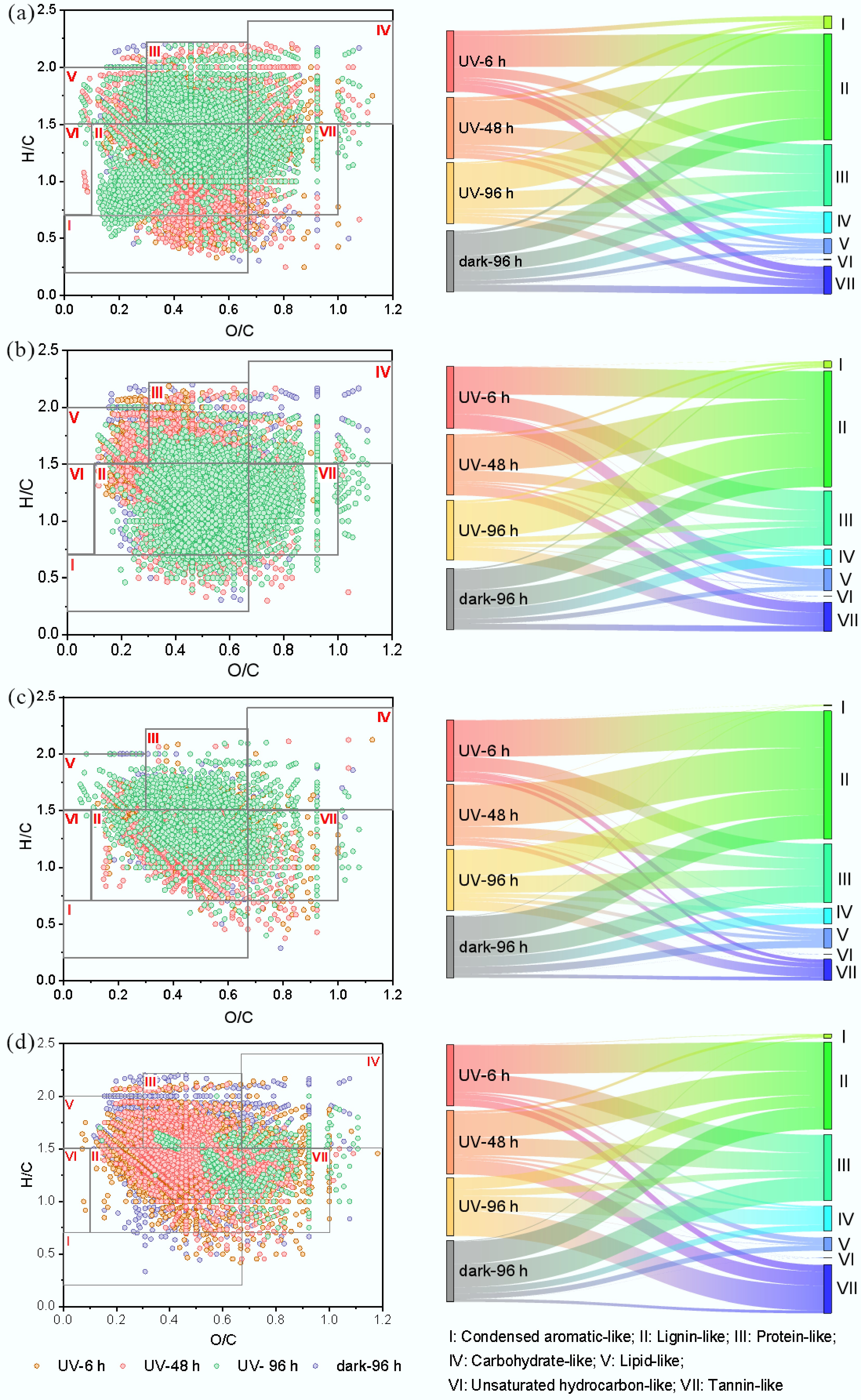

To further reveal the distribution and its variation in the diversity of chemical compositions, molecules were categorized into unsaturated-oxidized, unsaturated-reduced, saturated-reduced, and saturated-oxidized groups (Supplementary Table S2) based on (DBE-O)/C vs NOSC plots[34], NOSC reflects the oxidized and reduced state of molecules[35], (DBE-O)/C represents the unsaturation degree as the sum of aromatic rings and double bonds[32]. According to the van Krevelen diagram, they were classified into seven categories (Supplementary Table S3), i.e., lipid-like, protein-like, carbohydrate-like, unsaturated hydrocarbon-like, lignin-like, tannin-like, and condensed aromatic-like compounds[6]. MPs-DOM was dominated by reduced molecules (> 65%) (Fig. 7), by lignin-like (> 30%), and protein-like (> 25%) substances (Fig. 8). During the UV derivation process, the distribution of photo-reactive molecules in MPs-DOM demonstrated distinct trends. The proportion of saturated oxidized compounds increased by 10.07% with a drop in unsaturated oxidized compounds of 14.82% in PE-DOM (Fig. 7a−c), indicating that the abundance of C=C bonds decreased due to the addition reactions, and the compound distribution generally remained stable with a variation in relative abundance of less than 10%, apart from the protein-like substances, which increased by 11.25% (Fig. 8a), which was in accordance with the increase in the relative abundance of CHON (Supplementary Fig. S7). In PET-DOM, oxidized components increased by 57.5% (Fig. 7e−g), suggesting the formation of OFGs via photo-oxidation, which was in line with FT-IR results as the ester linkage in PET was cleaved to form the functional groups including aromatic alcohol (1,060 cm–1), phenolic hydroxyl (1,140 cm–1), quinone (1,690 cm–1), ether (1,060 cm–1), and carbonyl (940, 1,290, and 1,650 cm–1). Moreover, the proportions of lignin-like and tannin-like compounds increased by 11.35% and 21.45%, respectively, while those of protein-like and the lipid-like compounds decreased by 22.87% and 22.17%, respectively (Fig. 8b). For PBAT-DOM, the proportions of saturated and unsaturated reduced compounds decreased with an increase in saturated oxidized compounds by 33.75% (Fig. 7i−k), implying the formation of OFGs such as phenolic hydroxyl (1,370 cm–1), quinone (1,730 cm–1), acetyl (1,730 cm–1), carbonyl (1,730 cm–1), carboxyl (1,400, 1,630 cm–1) via hydrolysis, Norrish reaction, and photoreaction. Additionally, the proportion of lignin-like compounds decreased by 18.08%, while those of carbohydrate-like and the tannin-like compounds increased by 9.27% and 9.23%, respectively, the fluctuation in the others was within 10% (Fig. 8c). In PLA-DOM (Fig. 7m−o), the proportion of reduced components decreased with an increase in saturated oxidized compounds by 60.89%, suggesting that hydrolysis and photooxidation may occur to generate the structures such as hydroxyl (1,030 cm–1), ether (1,080 cm–1), acetyl (1,750 cm–1), carbonyl (2,940 cm–1), and carboxyl (1,400, 1,620 cm–1) based on FT-IR; the main components changed largely from the lignin-like (48.85%) and the protein-like (30.95%) to the tannic-like (41.90%), the carbohydrate-like (25.14%), and the lignin-like (20.11%) (Fig. 8d). Unlike MPs-DOM, the proportion of saturated oxidized compounds decreased by 29.92% with a corresponding increase in saturated reduced compounds in N-DOM (Fig. 7q−s), which was dominated by lignin-like compounds, accounting for approximately 60%, and the variation in each component was relatively stable within 10% (Supplementary Fig. S8a, S8b). For the photo-resistant group PE-DOM, PET-DOM, and PBAT-DOM were governed by the lignin-like and the protein-like substances with a total percentage of over 80%; for PLA-DOM, in addition to these two components, the tannin-like compounds were also a critical component (22.34%). N-DOM was dominated by the lignin-like (62.57%), the tannin-like (19.5%), and the condensed aromatic-like (15.26%) compounds.

Figure 8.

VK diagram and distribution of typical compounds during UV derivation process. (a) PE-DOM; (b) PET-DOM; (c) PBAT-DOM; (d) PLA-DOM.

Compared with dark treatment, UV did not significantly alter the proportion of each component in PE-DOM and PBAT-DOM (< 10%, Figs 7d, l & 8a, c). In PET-DOM, nearly 25% of reduced molecules were transformed into the oxidized compounds (Fig. 7h); consequently, instead of the reduced molecules, oxidized compounds became the primary component (> 50%); the proportion of protein-like substances dropped by 22.00%, meanwhile that of lignin-like and tannin-like compounds increased by 24.67% and 12.52%, respectively (Fig. 8b). These results were in line with EEM-PARAFAC (Fig. 5). In PLA-DOM, the proportion of saturated oxidized compounds increased by over 50% (Fig. 7p), accompanied by a decline in the other groups; the proportion of tannin-like compounds increased by 37.04%, while those of lignin-like and protein-like compounds descended by 18.14% and 28.32%, respectively (Fig. 8d). In N-DOM, UV irradiation enhanced the proportion of reduced compounds from 24.47% to 45.90% (Fig. 7t), and lignin-like (60.88%), instead of a combination of lignin-like and the tannin-like, became the sole primary component (Supplementary Fig. S8a, S8b).

Environmental implications

-

The current study demonstrated that solar or UV irradiation may promote the derivation and release of MPs-DOM from MPs into aquatic environments, and at the molecular level, the derivation kinetics of different MPs-DOM showed distinct patterns, which depended on the polymer type. Currently, the input of MPs into surface waters is not effectively controlled; their long-term contact with water, accompanied by the ubiquitous UV irradiation, causes MPs to constantly release MPs-DOM. Since the components and properties of MPs-DOM varied significantly during UV derivation processes, it is necessary to assess the environmental implications of MPs-DOM at different derivation stages; however, previous reports mainly focused on the initial and final states of MPs-DOM derived in the dark and under different irradiation conditions rather than the dynamics of the MPs-DOM derivation processes.

As an emerging component of DOM in aquatic environments, the contribution of MPs-DOM is expected to increase for the foreseeable future, due to the huge quantity of micro/nano-plastics and plastic wastes in the environment, and the amount is still on the rise. The composition and structure of MPs-DOM are largely different from those of N-DOM; thereby, the ever-growing abundance of MPs-DOM may alter the environmental effects and bioavailability of DOM in aquatic systems. The results of the current study suggested that compared with N-DOM, MPs-DOM was characterized by low-molecular-weight and oxidized molecules; thus, it may be bioavailable, serving as a primary carbon source for marine microorganisms and/or inhibiting the microbial growth, thereby the significant influx of DOC from MPs into the ocean may alter microbial metabolism and community structure, and further impact marine ecosystems and carbon sequestration in the ocean[9,22]. Furthermore, the presence of OFGs may enhance the polarity of the molecules, promoting MPs-DOM participation in the elemental biogeochemical cycles and in interactions with co-existing substances. PS-DOM can control the transformation of ferrihydrite, which may affect the nutrient cycling and pollutant transformation, and it exhibits a high affinity for minerals such as goethite, leading to a change in interface reactivity[4,36]. MPs-DOM was ready to form unstable complexes with heavy metal ions such as Cu, Cd, and Pb, and was susceptible to oxidation by Cr[37]. MPs-DOM also inhibited the adsorption of aromatic pollutants onto covalent triazine frameworks[38]. PS-DOM and PP-DOM serve as disinfection byproduct precursors, possessing the formation potential for trichloromethane as the dominant disinfection byproduct[39]. MPs-DOM can induce multiple reactive oxygen species, including hydroxyl radicals (•OH), superoxide radicals (O2•‒), and singlet oxygen (1O2) under solar irradiation[40,41], which may participate in the photoaging of MPs[9], accelerate the photodegradation of sulfamethazine[42] but inhibit the photodegradation of sulfamethoxazole[43], and induce the formation of Ag nanoparticles and Cr(VI)[44,45]. Furthermore, in comparison with NOM, the highly bioavailable MPs-DOM accelerated microbial respiration in soils by mediating physiological traits, leading to higher CO2 emission from soils and potential implications for climate change[46].

-

In the current study, based on the kinetic models, UV radiation was the primary factor controlling the derivation dynamics of MPs-DOM; the zero-order model fitted the experimental kinetic data well, and film diffusion was the rate-limiting step. During the derivation processes, the additives together with monomers and oligomers of the polymers and their oxygenated products contributed to MPs-DOM; a significant difference was observed between MPs-DOM and N-DOM in the derivation kinetics and chemical composition, but different types of MPs-DOM generally shared similar patterns. FT-ICR-MS further demonstrated the variation in the composition of MPs-DOM at the molecular level. Different types of MPs-DOM demonstrated distinct trends in chemical composition and properties during the UV derivation processes: in PE-DOM, the compound distribution generally remained stable; in PET-DOM, the proportions of lignin-like and tannin-like compounds increased, accompanied by a decrease in those of protein-like and lipid-like compounds; in PBAT-DOM, the proportion of lignin-like compounds decreased, with increases in those of carbohydrate-like and tannin-like compounds; in PLA-DOM, the main components changed largely from lignin-like and protein-like compounds to tannic-like, carbohydrate-like, and lignin-like compounds, indicating that these processes may depend on the polymer type. Given the extremely wide variety of polymers and the constant emission of plastic wastes and MPs, MPs-DOM is released continuously into the environment, exerting diverse environmental implications due to the change in molecular composition at different derivation stages. Thus, in the future, it is necessary to design machine learning-based approaches to predict the molecular dynamics of MPs-DOM during the derivation processes and provide a database for assessing the relevant environmental and ecological effects (such as elemental biogeochemical cycles, interaction with co-existing contaminants, bioavailability, and biotoxicity, among others).

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/newcontam-0025-0016.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Jiunian Guan; visualization, and writing—draft manuscript preparation: Shiting Liu, Xiamu Zelang; supervision: Jiunian Guan; investigation: Chao Ma, Zhuoyu Li, Xinyue Wang; funding acquisition: Hanyu Ju, Jingjie Zhang, Jiunian Guan; writing—review & editing: Jingjie Zhang, Jiunian Guan, Hanyu Ju. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42471089, 4231101419), the Research Foundation of the Science and Technology Agency (20250102178JC), and the Education Department of Jilin Province (JJKH20250337KJ).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

-

The derivation kinetics of MPs-DOM were revealed and compared with those of NOM in the dark and under UV irradiation.

The dynamics of molecular component distribution in MPs-DOM relied on the polymer types themselves.

MPs-DOM significantly differed from NOM on derivation dynamics and component distribution at the molecular level.

MPs-DOM may exhibit different environmental implications at different stages of the derivation processes.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Shiting Liu, Xiamu Zelang

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - The supplementary files can be downloaded from here.

- Supplementary Text S1

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Liu S, Zelang X, Ma C, Li Z, Wang X, et al. 2025. Molecular-level insights into derivation dynamics of microplastic-derived dissolved organic matter. New Contaminants 1: e016 doi: 10.48130/newcontam-0025-0016

Molecular-level insights into derivation dynamics of microplastic-derived dissolved organic matter

- Received: 30 September 2025

- Revised: 13 November 2025

- Accepted: 19 November 2025

- Published online: 05 December 2025

Abstract: Currently, microplastic-derived dissolved organic matter (MPs-DOM) is ubiquitous in natural surface waters, which not only contributes to dissolved organic carbon (DOC), but also becomes a specific component with significant environmental implications that differ from those of natural organic matter (NOM). Considering the continual disposal of MPs and plastic wastes into aquatic environments, MPs-DOM is constantly derived, and the molecular composition may be distinct over the derivation processes. Thus, in the current study, the kinetics of derivation and the variation of molecular features of MPs-DOM were investigated in comparison with those of NOM. The results showed that the zero-order model well fitted the experimental data and that film diffusion was the rate-limiting step for the UV derivation processes of MPs-DOM. The DOCUV/DOCdark ratio was generally correlated with derivation time, following the order of kPBAT (0.526) > kPLA (0.472) > kPET (0.147) > kPE (0.056) > kNOM (0.005), indicating that UV irradiation governed the derivation of MPs-DOM. Fluorescence spectra and HPLC-MS/MS indicated that the additives, together with monomers and oligomers of the polymers and their oxygenated products, contributed to MPs-DOM, while the components of MPs-DOM were largely different from those of NOM. FT-ICR-MS further demonstrated that the molecular composition of MPs-DOM derived from distinct polymer types varied separately, demonstrating that MPs-DOM at different derivation stages may show diverse environmental implications. In the future, the dynamic derivation of MPs-DOM can be further studied using artificial intelligence techniques, such as machine learning, to support a comprehensive assessment of its environmental implications.