-

Rhododendron maculiferum Franch., commonly referred to as the oriental azalea, is a variety highly prized for its ornamental value; its vibrant blooms and compact, dwarf growth have garnered widespread attention among horticulturalists and gardeners[1]. Beyond its prominent role in horticulture, its flexible branches and striking flowers and foliage make it an excellent choice for home gardening and interior decoration. When in bloom, R. maculiferum often creates a unique display of numerous large flowers that mask the branches and leaves, making it a favorite among flower enthusiasts. In modern horticultural production, accurately regulating the flowering period and improving flower quality are crucial strategies for enhancing economic returns and market competitiveness[2−4]. However, controlling the flowering period has always posed a significant challenge in cultivating R. maculiferum. As these plants bloom in the spring and their peak flowering period is brief, they frequently fail to meet the market demand for flowers with persistent ornamental value. Adequate regulation of the flowering period effectively extends the ornamental period and substantially improves the commercial value of plants in the horticultural market.

Flowering is a core developmental event in the plant life cycle, marking the critical transition from vegetative to reproductive growth. This process is coordinated by internal developmental signals and external environmental factors such as photoperiod, temperature, and humidity[5]. As the initial stage of reproductive growth, precise floral transition is crucial for plants to maximize reproductive success, particularly in their responses to endogenous developmental cues and environmental stresses. The dynamic balance of plant hormones plays a key regulatory role in controlling flower bud differentiation and flowering processes[6]. Studies have shown that the dynamic changes in the contents of gibberellin (GA3), abscisic acid (ABA), zeatin riboside (ZR), and indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) in flower buds collectively participate in the fine regulation of plant differentiation processes[7,8]. GA has been demonstrated to be a core hormone in the floral transition of Arabidopsis thaliana, primarily driving the flowering process by promoting cell division and elongation, and is broadly involved in almost all major developmental processes of plants, from seed germination, stem elongation, leaf expansion to flowering[9]. Higher concentrations of ABA are critical for forming multiple flowers throughout the year in blueberries[10]. Exogenous hormones exert notable effects on the regulation of flower bud dormancy: ABA and IAA treatments inhibit the release of flower bud dormancy, whereas 6-benzylaminopurine (6-BA), GA3, and GA4 treatments promote dormancy release[11,12]. In the branches of the sweet cherry 'Summit', a higher ratio of GA to ABA is observed from dormancy break to full bloom, further corroborating the regulatory role of hormone dynamic balance[13]. Additionally, exogenous GA3 treatment has been confirmed as a highly effective approach, second only to natural conditions for promoting flowering in tree peony cultivars[14].

Melatonin is a widely present biogenic amine hormone in animals and plants. Melatonin (N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine), when synthesized by plants, is known as phytomelatonin (PMT). It was first detected by several independent research groups in 1995[15]. Its functions involve the regulation of plant circadian rhythms and photoperiods[16]. They are also deeply involved in key plant growth and development processes, including root morphogenesis, seed germination, circadian rhythm regulation, stress response, and flowering transformation. Kolár et al. found that exogenous PMT concentration can significantly affect the flowering process of Chenopodium rubrum, suggesting that it may act in the early stages of flowering initiation[17]. Park et al. observed that PMT synthesis could be induced during the development of rice flower buds, thereby regulating flowering time[18]. Shi et al.[19] further revealed the direct correlation mechanism between PMT and the floral transition. Although PMT does not affect the overall flowering stage, it can specifically regulate the key links of floral transition by interfering with the expression of flowering-related transcription factors. In addition, applying 20 μM PMT in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) effectively enhanced pollen vitality[20]. Experiments on 'Fuji' apples showed that spraying different concentrations of PMT (0, 20, 200, 1,000 μM) before mixed bud germination resulted in a 2 d delay in the flowering period for the 20 μM and 200 μM treatment groups compared to the control group, and a 3 d delay for the 1,000 μM treatment group[21].

PMT is highly similar in chemical structure to classical plant hormones, and it shares tryptophan as a synthetic precursor with auxin (IAA); this suggests that, as growth regulators, the two may exhibit functional synergy in regulating plant growth and development[22]. The exertion of PMT's functions in plants appears to involve synergistic effects with other known plant hormones. As an important component, PMT can effectively promote plant growth, prolong the flowering period, and improve flower quality in plants. In a study on floral transition in Arabidopsis thaliana, Zhang et al.[23] revealed a direct association mechanism between strigolactones and PMT. Their research proposed that when PMT content in tissues exceeds a specific threshold, strigolactones act upstream of the PMT signaling pathway by regulating protease activity in FLC activation, thereby delaying the flowering process[24]. Jahan et al.[25] further discovered that PMT can inhibit tomato senescence through signaling pathways mediated by ABA and GA. Notably, treatment with 100 μM PMT significantly increases endogenous PMT levels in tomato seedlings and promotes early flowering in plants by upregulating the expression of genes related to endogenous hormone synthesis. Additionally, the upregulatory effect of PMT on key hormones such as GA and IAA serves as an important molecular basis for promoting flower organ development, prolonging the flowering period, and improving flower quality[26].

PMT also participates in the metabolic regulation processes of plants, especially in carbohydrate metabolism. It provides energy support for extended flowering periods and flower development by influencing the accumulation of endogenous substances, while also promoting the synthesis of sugars and starch, thereby enhancing plant growth potential[27]. Exogenous PMT can significantly regulate the contents of sorbose, mannobiose, galactitol, and mannitol in Bermuda grass (Cynodon dactylon L.)[28]. In contrast, in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.), exogenous PMT effectively improves pollen fertility by regulating carbohydrate metabolism in male tissues[29]. Although PMT fulfills multiple plant functions, it is a potent free radical scavenger, and its antioxidant characteristics are particularly prominent, significantly enhancing plant resistance to oxidative damage. As a safe and beneficial indoleamine substance, PMT not only directly scavenges reactive oxygen species (ROS) to alleviate flower senescence but also activates plant antioxidant mechanisms through pathways such as upregulating the transcriptional levels of antioxidant-related genes, enhancing the activity of antioxidant enzymes, and synergistically improving the efficiency of other antioxidants[30,31].

Additionally, lower levels of endogenous melatonin can promote an increase in anthocyanin content: seeds of snat1 and coPMT1 Arabidopsis mutants exhibit significantly lower levels of PMT than the wild-type Col-0. In contrast, their anthocyanin concentrations are notably higher than those of the wild-type[32]. Therefore, PMT can induce significant changes in various physiological processes of plants, affecting the flowering period. Thus, this study aims to investigate the effects of exogenous PMT on the flowering period, accumulation of endogenous substances, and endogenous hormones in R. maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster'. By applying exogenous PMT at different concentrations, this study explores its regulatory effects on the flowering performance, flower development, and physiological responses of R. maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster'. The research results provide a theoretical basis for the precision cultivation of R. maculiferum and offer new insights for the flowering period regulation and quality improvement of other ornamental flowers. This study expects to elucidate the multiple roles of PMT in plant growth and development and provide new directions for efficient and environmentally friendly regulatory technologies in horticultural production.

-

Two-year-old, healthy, pest- and disease-free, and uniformly-sized potted R. maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster' specimens were selected for the experiment. The height of the selected plants ranged between 40 and 50 cm, with crown diameter also between 40 and 50 cm. The plants were cultivated individually in plastic pots (diameter 20 cm, height 20 cm) containing a potting mixture of peat soil and perlite in a 3:1 ratio.

PMT with a purity of 99%, anhydrous ethanol, Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 reagent, anthocyanin assay kit, peroxidase (POD) activity assay kit, and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity assay kit were purchased from Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. The preparation steps for the PMT solution in the experiment are as follows: First, the weighed PMT powder was fully dissolved in absolute ethanol; after complete dissolution, it was topped up to 1 L with distilled water.

Methods

Experimental design

-

The experiment was conducted from November 2023 to November 2024 in the smart greenhouse facility of the Landscape Engineering Technology Centre at Jiangsu Urban and Rural Construction Vocational College. The potted plants were divided into six treatment groups (n = 15/group) based on concentration of the PMT spray: 100 μmol·L−1 (MT1), 300 μmol·L−1 (MT2), 500 μmol·L−1 (MT3), 1 mmol·L−1 (MT4), 3 mmol·L−1 (MT5), and 5 mmol·L−1 (MT6), with water sprayed as the control (CK). PMT was sprayed onto the entire plant at the onset of the bud break period after the flower bud differentiation stage. Treatments were applied once every 7 d, for three applications during the experimental period. Each spraying was performed until the leaves and flower buds dripped with solution.

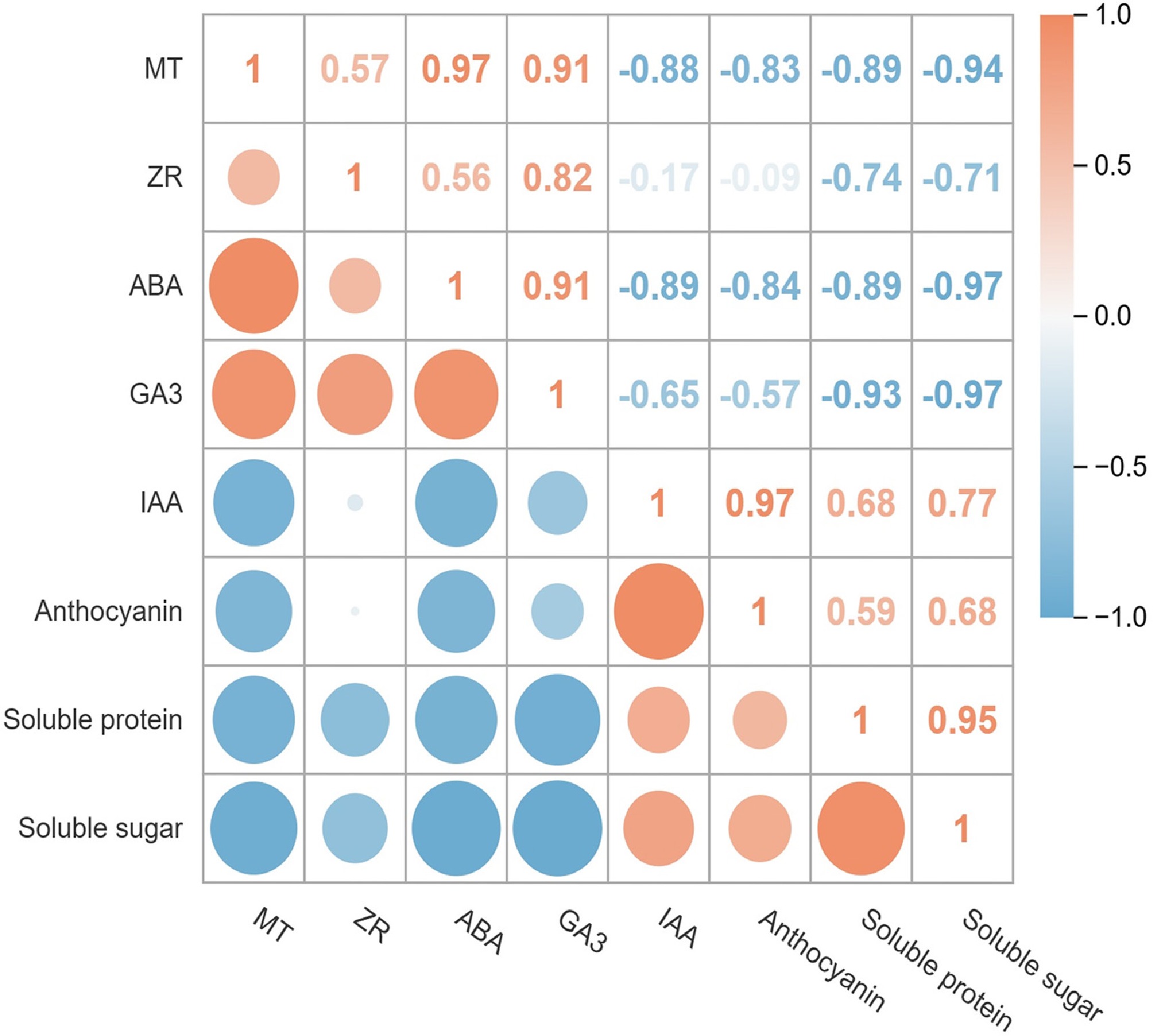

Sampling began 15 d after the third treatment, and samples were collected every 15 d (D-15, D-30, and D-45) for three sample collections post-treatment. For each sample, three pots of plants were randomly selected, and flower buds from different positions on the plants were collected to measure morphological indexes. As for endogenous physiological indicators, flower buds from the MT2, MT3, and MT5 treatments, which showed significant differences in ornamental traits, were selected (Fig. 1 and Table 1). After sampling, the buds were immediately placed in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. Morphological and phenological observations of the potted plants were made daily at 15:00 h. The endogenous physiological indicators measured included: anthocyanin content, endogenous nutrient content, and levels of Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), Abscisic Acid (ABA), Gibberellic Acid (GA3), Trans-Zeatin-riboside (ZR), and Phytomelatonin (PMT).

Figure 1.

Effect of different concentrations of melatonin on the flowering period of Rhododendron maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster'. (a) Phenotypic changes after different MT treatments. (b) Flowering last days. (c) Advance flowering time.

Table 1. Effect of different concentrations of melatonin (MT) on flowering period and flower quality of Rhododendron maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster'.

Treatment MT concentration

(μmol·L−1)Initial flowering

dateFull bloom date Flower diameter

(cm)Flowering

duration (d)Advance flowering

duration (d)Flowering rate

(%)CK 0 20 March 12 April 7.56 ± 0.27 f 17 ± 3.17 e − 68.89 ± 2.35 f MT1 100 10 March 31 March 7.89 ± 0.23 d 26 ± 1.99 c 10 ± 0.37 78.22 ± 1.26 d MT2 300 6 March 28 March 8.23 ± 0.12 b 32 ± 2.13 a 14 ± 0.85 86.69 ± 2.33 b MT3 500 13 March 31 March 8.66 ± 0.33 a 26 ± 2.88 c 7 ± 1.22 88.78 ± 2.88 a MT4 1,000 20 March 10 April 7.61 ± 0.13 e 25 ± 1.89 d 0 ± 3.18 82.33 ± 2.56 c MT5 3,000 28 March 16 April 8.13 ± 0.23 c 28 ± 2.33 b – 8 ± 0.98 78.56 ± 3.25 d MT6 5,000 1 April 18 April 7.84 ± 0.09 d 28 ± 1.98 b −10 ± 1.87 72.68 ± 2.82e Measurement of morphological and phenological indexes

-

After the last PMT application, the ornamental traits of the potted plants were observed and recorded daily at 15:00. The flowering status of the plant was also monitored. Flowering period was recorded for each treatment, which referred to the total number of days in the bud stage, initial flowering stage, full flowering stage, and final flowering stage. The flowering rate was the ratio of the total number of flowers to the total number of flower buds. The flower diameter was maximum when the flower buds were fully open.

Measurement of endogenous physiological indicators

Anthocyanin content

-

Anthocyanin content was determined using an anthocyanin assay kit (Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd, Shanghai, People's Republic of China, D799289). The specific method was as follows: 0.1 g of flower buds was added to 1 mL of extraction solution. After thorough homogenization, the mixture was transferred into an EP tube (Eppendorf Microtest tubes) sealed with film to prevent evaporation. Extraction was performed at 60 °C for 30 min. The resulting extract was diluted to a final volume of 1 mL and then centrifuged at 12,000 × g at 25 °C for 10 min. The supernatant was collected for the spectrophotometric analysis, with absorbance measured at 530 nm (A1), and 700 nm (A2). Anthocyanin content (mg/L FW) was then calculated as follows:

$ \mathrm{0.037\times \Delta A\times 10/FW} $ where, FW is fresh weight, and ∆A = A1 – A2.

Endogenous nutrient content

-

To measure the soluble sugar content of the flowers, 0.1 g of flower bud powder was ground with 80% anhydrous ethanol at 4 °C. The mixture was centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 5 min. 0.2 mL of supernatant was mixed with 0.1 mL of anthrone ethyl acetate and 1 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid, then placed in a boiling water bath for 10 min to obtain the final product, which was allowed to cool to room temperature. The absorbance of the sample was measured at 662 nm using a spectrophotometer. The soluble sugar content (mg·g−1 FW) was calculated as follows:

$ \mathrm{[(OD662+0.07)/8.55\;V}_{ \mathrm{1}} \mathrm{]/(FWV}_{ \mathrm{1}} \mathrm{/V}_{ \mathrm{2}} \mathrm{)} $ where, FW is fresh weight, V1 is the sample volume, and V2 is the extraction solution volume.

To measure the soluble protein content of the flowers, 0.1 g of flower bud was ground with 1 mL of extract solution, then centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 10 min. Pipette 20 μL of the supernatant solution (add distilled water for the control group) and mix it with 1 mL of the working solution. Place the mixture in a boiling water bath for 30 min, then cool it to room temperature. Measure the OD value at 526 nm. Protein content (mg·L−1 FW) was calculated as follows:

$ \mathrm{0.5 \Delta A/\Delta A/FW} $ ∆A = A1 − A0, where A1 is the absorbance measured at 530 nm of the sample, and A0 is the absorbance measured at 530 nm of the control group. FW is fresh weight.

Endogenous hormone content

-

Endogenous hormone content, including IAA, GA3, ZR, ABA, and PMT, was quantified using the liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry platform manufactured by Metware Co., Ltd (Wuhan, People's Republic of China). The measurement methods were based on those described by Deng et al.[18].

Data analysis

-

All experiments included three independent plants of the same age and growing conditions. For each treatment, three samples were measured for all indicators, with three replicates for each experiment. Raw data were collated using Excel 2019. Statistical analysis and graphing were performed using GraphPad Prism.

-

The results showed that all exogenous PMT treatments could increase the flowering duration, flower diameter, and flowering rate compared with the control (Table 1). Regarding the flowering period, it was found that under lower concentrations of PMT (MT1, MT2, MT3), the flowering time occurred earlier than the control. Specifically, the flowering period of the 300 μmol·L−1 PMT (MT2) treatment occurred 14 d earlier compared with the control, and its flowering period had the longest duration, extending by 15 d compared to the control. However, as the PMT concentration increased, the flowering period was gradually delayed. The 1 mmol·L−1 PMT (MT4) treatment group was found to have an initial flowering time similar to that of the control, but the flowering duration was extended by 8 d. Under higher concentrations of PMT (MT5, MT6), the flowering time was delayed compared with the control. When PMT concentration increased to 5 mmol·L−1 (MT6), the flowering time was delayed by 12 d compared to the control. The flowering duration was extended by 11 d (Fig. 1); this indicates that different PMT concentrations significantly affected the flowering period, prolonged the flowering duration, and improved the flowering rate.

Effect of exogenous phytomelatonin treatment on endogenous substances

Endogenous nutrients

-

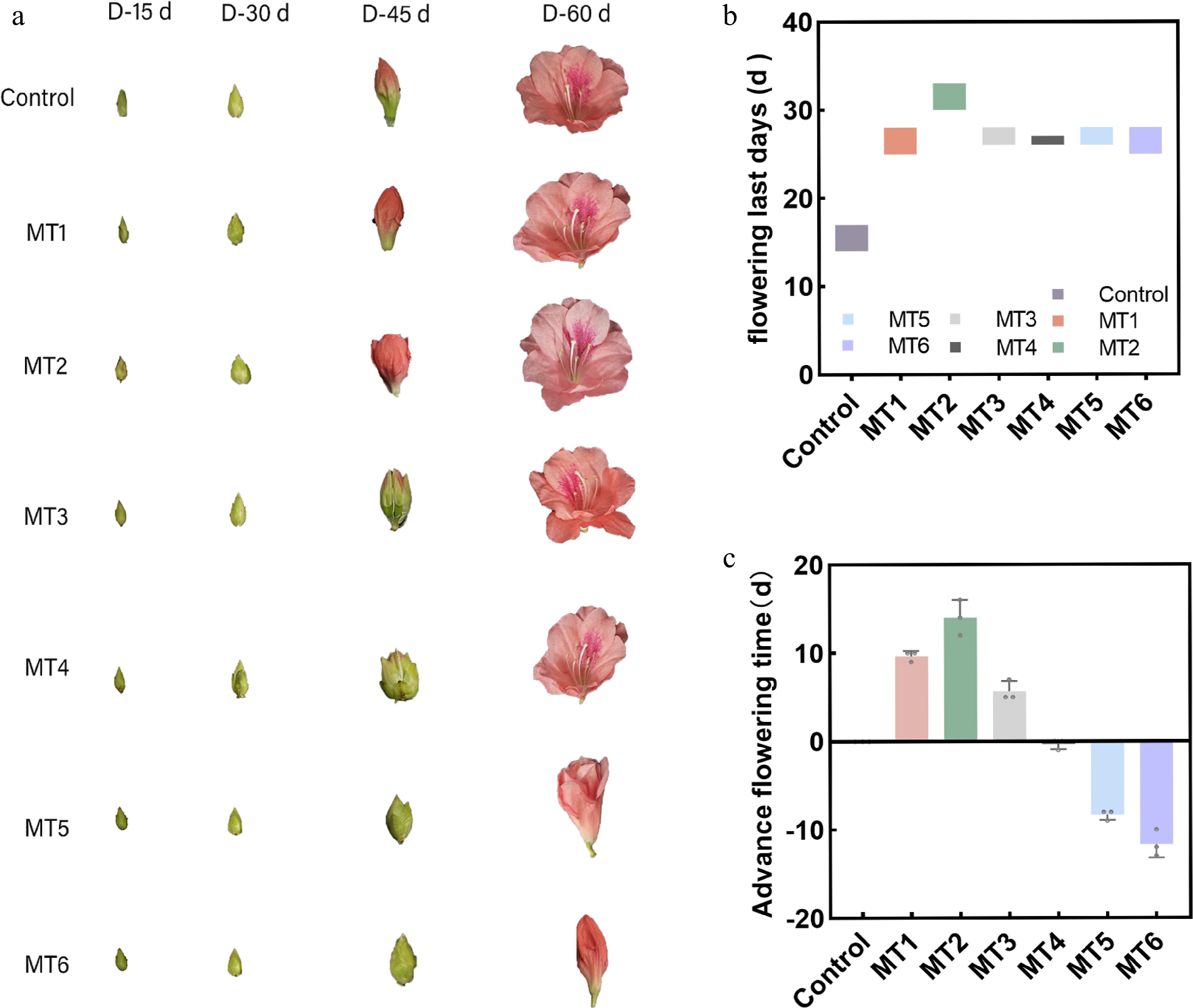

After three treatments, the soluble sugar content in all groups exhibited an upward trend, reaching the highest value on D-45 (45 d after the third treatment). The soluble sugar content of R. maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster' in different groups was as follows: 106 mg·g−1 (CK), 119 mg·g−1 (MT2), 110 mg·g−1 (MT3), and 115 mg·g−1 (MT5). As shown in Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table S1, within 15–45 d after treatment, the soluble sugar content of MT2 remained significantly higher than that of the control, while the soluble sugar content of MT5 was significantly lower than that of the control group at D-15 and D-30, but increased significantly at D-45 and was slightly higher than that of the control. These results suggest that certain concentrations of PMT could enhance the mobilization and distribution of soluble total sugars. The trend of soluble protein content was similar to that of soluble sugars, exhibiting an upward trend and reaching the highest value on D-45, increasing by 40.5% (MT2), 30% (MT4), and 31.6% (MT5) (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Table S2). These results further suggest that PMT treatment at certain concentrations can significantly increase the soluble sugar and soluble protein contents in R. maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster', and these factors play a positive role in regulating the onset and duration of the flowering period.

Figure 2.

Effect of different concentrations of MT on endogenous nutrients in Rhododendron maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster'. (a) Soluble sugar content. (b) Soluble protein content.

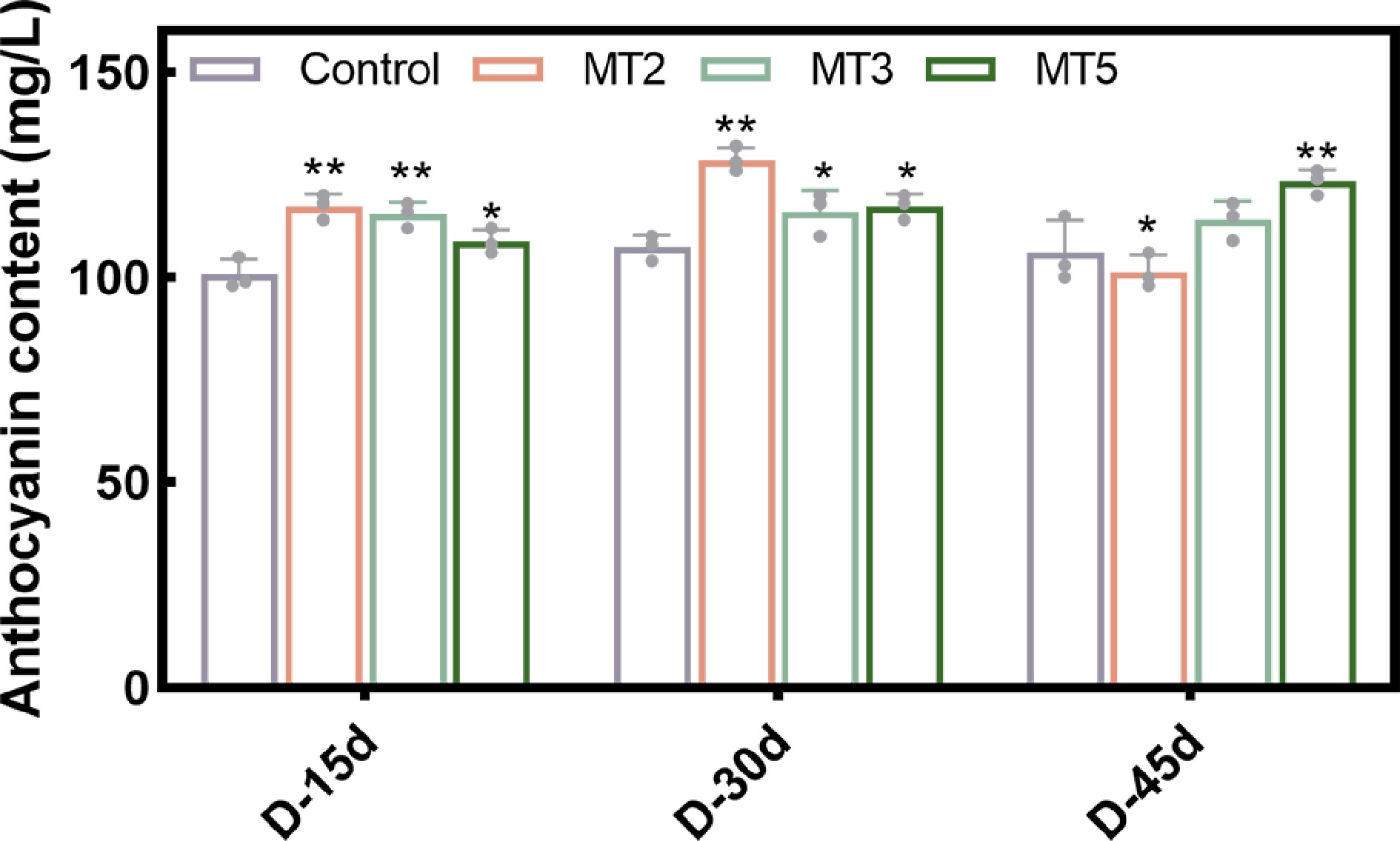

Anthocyanin content

-

Exogenous PMT treatment significantly promoted the anthocyanin content in R. maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster' (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S3). Specifically, the MT2 treatment group showed the highest anthocyanin content on D-30 (30 d after the third treatment), reaching 129 mg·L−1, before gradually decreasing. On D-45, anthocyanin content was slightly lower than that of the control group. The MT3 treatment followed a trend similar to the control group, but the anthocyanin content was slightly higher overall. In general, the MT5 treatment resulted in a gradual increase in anthocyanin content, reaching the highest level of 123 mg·L−1 on D-45, which was 1.16 times that of the control group. Overall, treatment with low-concentration PMT (MT2) promoted the differentiation of flower buds, with the anthocyanin content peaking on D-30, reaching 1.2 times that of the control. Treatment with high-concentration PMT (MT5) inhibited flower bud differentiation. Still, it promoted differentiation in the later stages, with anthocyanin content on D-45 reaching 1.13 times higher than the corresponding value on D-15 (15 d after the third treatment).

Figure 3.

Effect of different concentrations of MT on anthocyanin content of Rhododendron maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster'.

Effect of exogenous phytomelatonin treatment on the level of endogenous hormones

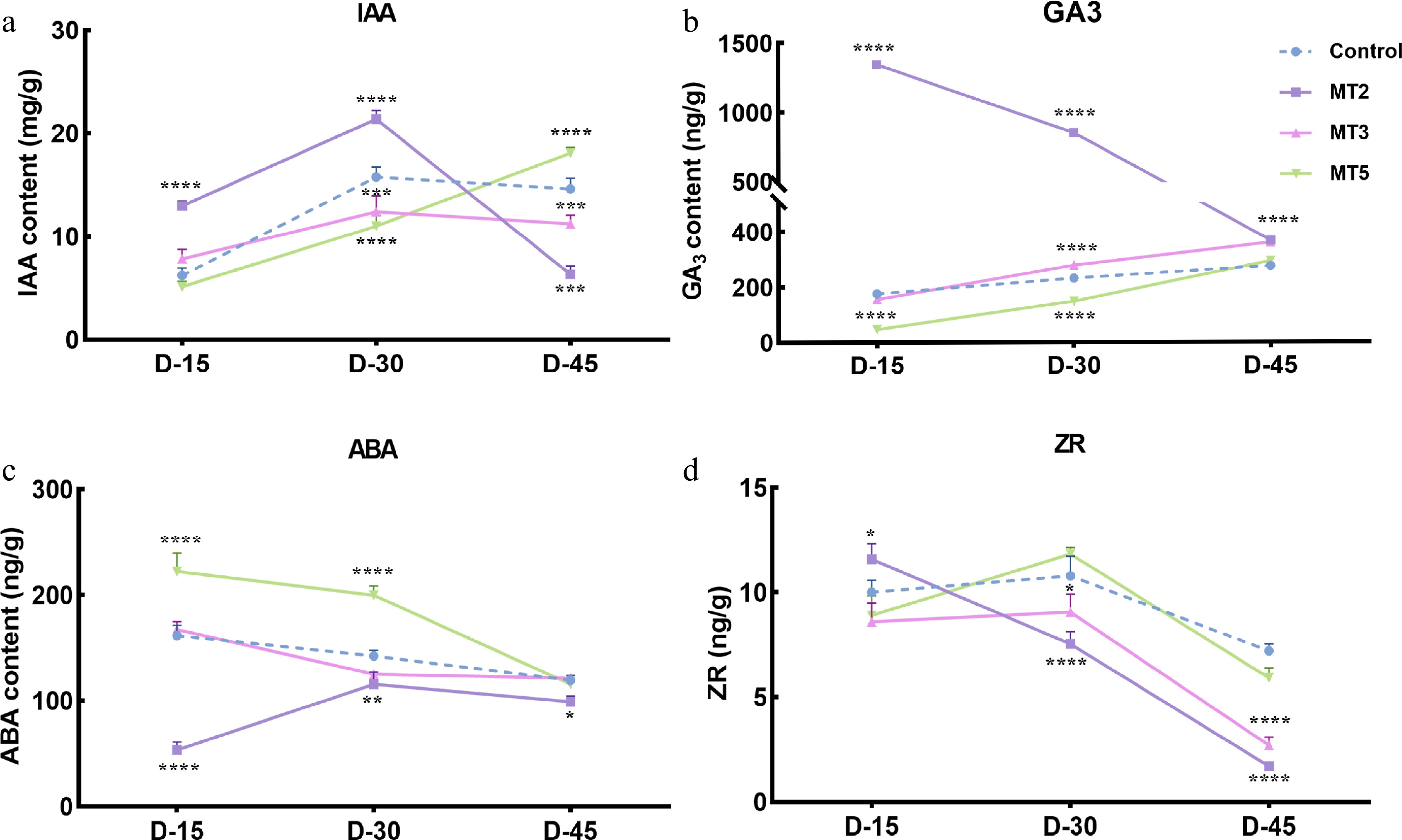

Level of endogenous IAA

-

IAA was one of the first plant hormones discovered to promote growth and delay senescence. After exogenous PMT treatment, the endogenous IAA content in the flower buds of the control and low-concentration PMT treatment groups showed an initial increase followed by a decrease. However, the treatment with high-concentration MT5 (3 mmol·L−1) gradually increased IAA content in the flower buds. Overall, low-concentration PMT promoted the maintenance of relatively high endogenous IAA levels in the early stages. After 30 d of treatment, the IAA content in MT2 (300 μmol·L−1) increased by 36.87% compared to the control group. High-concentration MT5 initially inhibited the formation of endogenous IAA in R. maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster' flower buds. After 30 d of treatment, the IAA content decreased by 29.62% compared to the control group. However, on D-45, the IAA content in the MT5 group increased by 24.9% compared to the control (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Table S4); this indicates that exogenous PMT treatment at certain concentrations can regulate the changes in endogenous IAA content, thereby influencing the flowering time of R. maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster'.

Figure 4.

Effect of different concentrations of MT on endogenous hormone content in Rhododendron maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster'. (a) IAA content. (b) GA3 content. (c) ABA content. (d) ZR content.

Level of endogenous GA3

-

GA3 has been found to promote germination, tillering, and bolting, inhibit plant maturation and senescence, and enhance fruiting rate and yield. As shown in Fig. 5, treatment with exogenous low-concentration PMT (MT2) significantly increased the endogenous GA3 content in the early stage (15 d after treatment), which reached 1.95 times that of the control. The GA3 content gradually decreased but remained higher than that of the control throughout the treatment. The trends observed under the MT3 and MT5 treatments were similar to those of the control, with both cases showing a gradual increase in GA3 content. However, the growth rate of the control was slower than that of MT-treated plants, with an increase of only 80% from D-15 to D-45. In contrast, the growth of the MT3 and MT5 plants increased by 132% and 150%, respectively, over the same period (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Table S5). Overall, low-concentration PMT treatment contributed significantly to maintaining relatively high endogenous GA3 levels in the early stage, thus promoting earlier flowering in R. maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster'.

Figure 5.

Effect of different concentrations of exogenous MT on endogenous MT content in Rhododendron maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster'.

Level of endogenous ABA

-

ABA is a common growth inhibitor, and higher concentrations of ABA can suppress plant growth or accelerate senescence and organ degeneration. The changes in endogenous ABA content in R. maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster' were opposite to the trends in endogenous GA3 content (Fig. 4b, c). Treatment with exogenous low-concentration PMT (MT2, 300 μmol·L−1) significantly reduced endogenous ABA content in the early stage (15 d after the third treatment), after which the content increased and stabilized. Plants in the MT3 and MT5 treatment groups showed trends similar to that of the control, i.e., a gradual decrease in ABA content. In contrast with the control and MT3 plants, which showed a gradual decrease, MT5 plants showed a significant decline at D-45, such that ABA content was 1.93 times lower than at D-15. Further analysis revealed that treatment with low-concentration MT inhibited the large-scale production of ABA in the early stage, which decreased to 3.04 times lower than that of the control. In contrast, high-concentration MT treatment increased ABA production to 1.38 times that of the Supplementary Table S6.

Endogenous ZR

-

As shown in Fig. 4d and Supplementary Table S7, after treatment with different concentrations of PMT, the endogenous ZR content in R. maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster' flower buds showed an overall decreasing trend. As treatment time progressed, endogenous ZR content was highest under MT2 at D-15, which was followed by a linear decrease; the trend in the PMT3 treatment group was similar to that in the control, whereas MT5 significantly increased ZR content at D-30. PMT treatment altered the endogenous ZR content in the flower buds, and higher ZR concentrations helped promote flower bud differentiation. Overall, low-concentration PMT treatment helped maintain higher levels of endogenous ZR in the early stages, with ZR content in MT2 being 15% higher than that in control after D-15. High-concentration PMT treatment suppressed the formation of endogenous ZR in flower buds in the early stages, thus delaying the flowering time. After D-30, the ZR content in MT5 increased by 13% compared to the control.

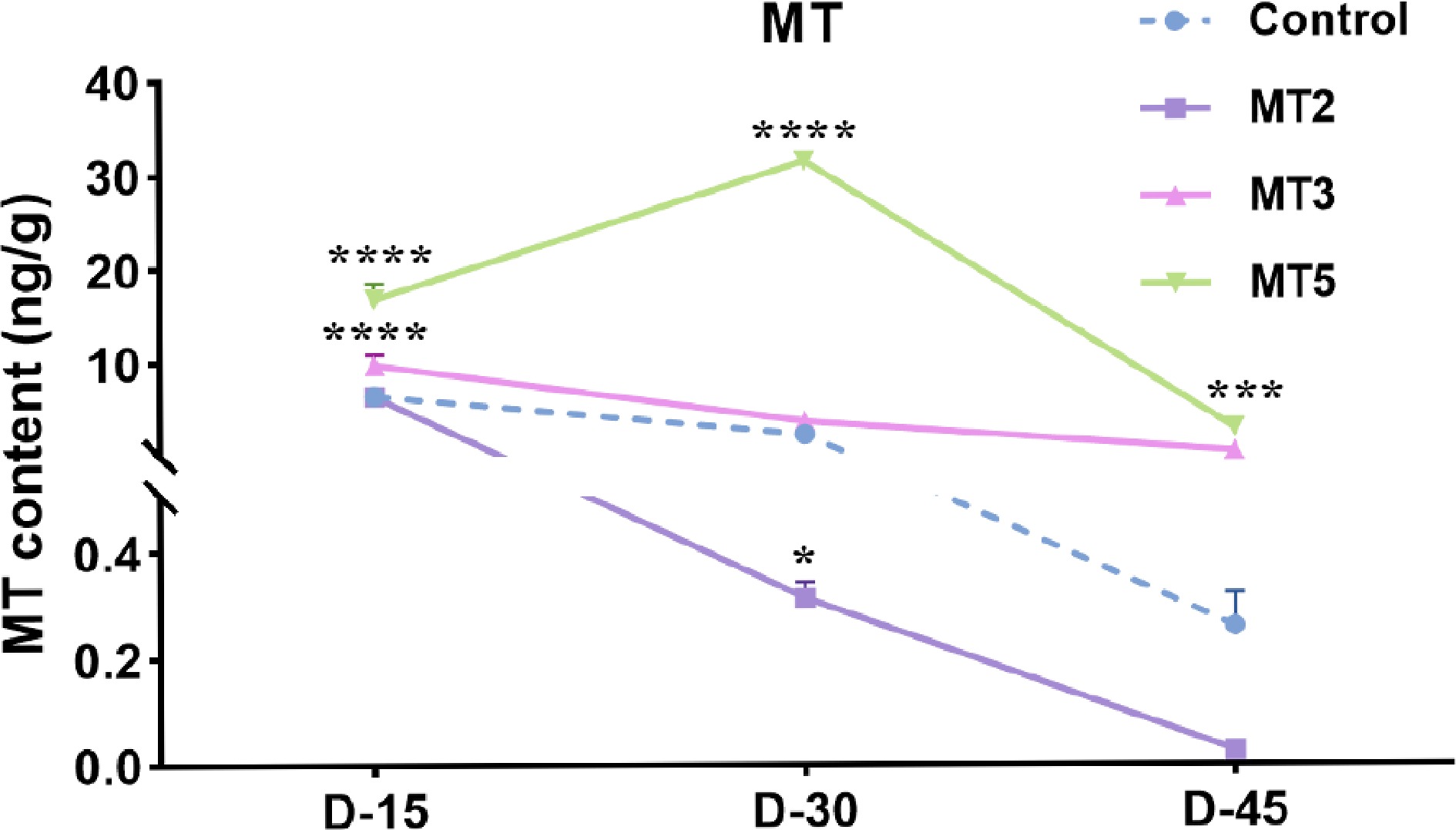

Endogenous PMT

-

As shown in Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table S8, when the exogenous PMT concentration was low (MT2), the endogenous PMT content in R. maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster' flower buds showed a sharp decline, decreasing by up to 99% from D-15 to D-45, reducing the PMT content in the flower buds to nearly zero. However, when a higher concentration of MT5 (3 mmol·L−1) was applied, the endogenous PMT content in the flower buds showed an initial increase, followed by a decrease from D-15 to D-45, while the PMT content on D-30 was 48% higher than on D-15. Based on a comprehensive phenotype analysis (Fig. 1), it was concluded that the exogenous PMT treatment effect is concentration-dependent, with low PMT concentrations promoting earlier flowering and high PMT concentrations delaying the flowering period.

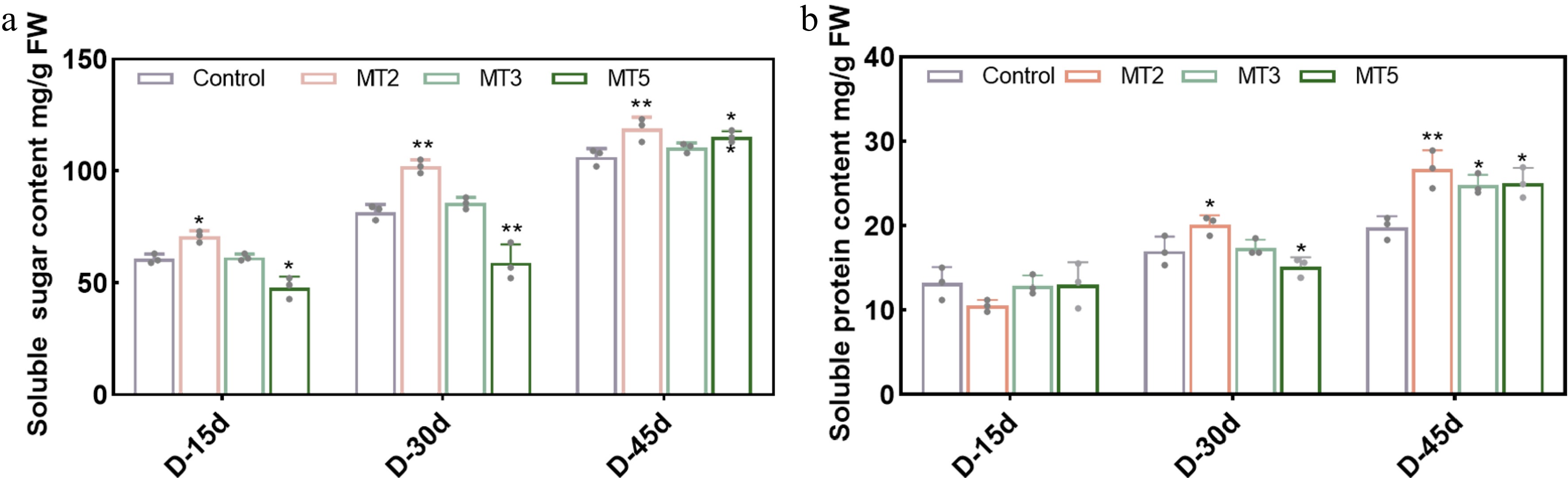

Correlation between physiological indicators and endogenous hormone levels

-

Under the action of exogenous PMT, a regular pattern of changes was observed between physiological indicators and endogenous hormones (Fig. 6). Specifically, the positive correlation between endogenous ABA and endogenous MT was the most significant (r = 0.97), followed by the positive correlation between soluble sugar content and soluble protein content (r = 0.95). Notably, endogenous MT exhibited a significant negative correlation with soluble sugar and protein content ( r = −0.94 and −0.89, respectively). Additionally, endogenous ABA showed a strong negative correlation with soluble sugar and protein content (r = −0.97 and −0.89, respectively). Analysis of dynamic changes revealed that endogenous MT levels displayed a continuous downward trend over time (Fig. 2). Combined with its negative correlation with the flowering process, it is speculated that endogenous PMT may exert a potential inhibitory effect on flowering. In contrast, soluble sugar and protein contents continuously increased during the flowering, indicating that they might act as positive regulatory factors in flowering regulation. These results further validated the negative correlation between endogenous PMT and soluble sugar/protein contents, and this negative regulatory characteristic might prolong the flowering period to a certain extent. Based on these findings, exogenous PMT may indirectly affect the accumulation of soluble sugar and soluble protein by regulating endogenous hormone levels, thereby regulating plant physiological processes, suggesting that exogenous PMT has a potential regulatory role in plant growth and development.

-

Regulating flowering time is crucial for enhancing the ornamental value of plants. PMT is known to regulate the differentiation process of plant tissues into cells and organs, thus exerting some control over the flowering period of plants[33−35]. PMT has been shown to promote the coleoptile growth in plant species, including Hypericum perforatum, Chenopodium rubrum, Datura metel, and Panicum virgatum[17, 36−38]. In the model plant A. thaliana, a dose-dependent effect of phytomelatonin on flowering time was found, whereby phytomelatonin concentrations in fresh leaf tissue > 8 ng·g−1 delayed flowering time. In contrast, concentrations < 0.9 ng·g−1 triggered flowering. At concentrations of 10 μM and 20 μM, exogenous phytomelatonin did not affect flowering time, as the leaf phytomelatonin levels were beyond the range of the threshold dose[36]. Furthermore, the inhibitory effects of 500 μM and 1,000 μM phytomelatonin (exceeding the above applied concentration of 50 μM by several orders of magnitude) on A. thaliana flowering time were reported by another research team[37]. In this study, low concentrations of exogenous PMT (MT2, 300 μmol·L−1) caused R. maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster' flowering time to occur 14 d earlier than the control. They extended the flowering duration by 15 d. As the concentration of exogenous PMT increased, the flowering time was gradually delayed, particularly under the high-concentration MT5 (3 mmol·L−1) treatment, where the initial flowering time was delayed by 12 d and the flowering duration was extended by 11 d; this indicates that within a certain concentration range, exogenous PMT can regulate the flowering period of this azalea cultivar, with low concentrations promoting flowering and high concentrations inhibiting flowering, while also offering the potential of extending flowering duration.

PMT treatment also improved flower quality, producing larger flower sizes, more vibrant flower colors, and greater flower uniformity[38]. This effect is likely closely related to its role in regulating endogenous hormones in plants. Flowering is a complex physiological, biochemical, and morphological process that requires substantial accumulation of starch, soluble sugars, and proteins, which serve as the material basis for flowering during flower bud differentiation[39]. Changes in the soluble sugar content in plants remarkably influenced the flowering process. Here, it was found that soluble sugar content peaked on D-45, with MT2 showing the highest content at 123 mg·L−1. In the MT5 treatment group, soluble sugar content did not peak by D-45, possibly related to a diminished response to exogenous hormones or increased physiological stress under high-concentration PMT treatment. Additionally, soluble protein content exhibited a pattern of change similar to that of soluble sugars, consistent with previous studies.

Flowering regulation in plants depends on the joint regulatory effects of endogenous hormones, whereby hormones promote or antagonize each other to form a complex regulatory network[40,41]. Plant growth regulators influence the endogenous hormone system through exogenous supply, promoting cell growth and the transfer of nutrients to reproductive growth[41]. In the present study, it was found that after exogenous PMT treatment, the GA3 content peaked on D-15 in the MT2 group but on D-45 in the MT5 group. During flowering regulation in A. thaliana, PMT exists within a 'safe' threshold range, where it can promote flowering. Outside this range, it induces the synthesis of endogenous PMT, which can inhibit flowering. These results suggest that the PMT signaling pathway may be downstream of the GA signaling pathway, which can activate the expression of FLC, thereby leading to delayed flowering[23]. Low concentrations of IAA promote floral bud differentiation, whereas high concentrations inhibit floral bud development. Exogenous PMT treatment gradually increases the endogenous IAA content in plants.

Furthermore, when exogenous PMT is compared with exogenous IAA, both exhibit similar concentration gradient effects, indicating that both may simultaneously regulate plant growth. The higher levels of ABA in the early stage of treatment may be related to active metabolism and cell division. In contrast, the lower levels of ABA in the later stages are associated with plant maturation. The application of PMT can affect ABA content in floral buds, leading to a notable decrease in ABA levels in the later stages. These findings are consistent with those by Zhang et al., who observed similar results in A. thaliana[23].

Although the findings of the present study have validated the crucial role of PMT in regulating the flowering period and physiological characteristics of R. maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster', the synergistic effects of PMT with other hormones, such as ABA and cytokinin, and their potential interactions in flowering regulation warrant further exploration. Additionally, the focus of this study was a single cultivar of R. maculiferum; this limits the applicability of these results, as different cultivars of R. maculiferum may exhibit varying responses to PMT treatment. Additional azalea cultivars should be examined in future research, focusing on the regulatory patterns under different genetic backgrounds. This approach will contribute to a more comprehensive scientific basis for understanding hormonal regulation mechanisms in the flowering process of ornamental plants.

-

Exogenous PMT in R. maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster' exhibited a concentration-dependent effect during flowering regulation in the greenhouse environment. PMT concentrations sprayed on fresh flower tissue > 3 mmol·L−1 delayed flowering time, whereas concentrations < 0.5 mmol·L−1 triggered flowering. All treatments extended the flowering duration, with the longest duration observed under MT2 (32 d). Physiological analyses showed that PMT treatment significantly enhanced endogenous nutrient levels. Compared to the control, low-concentration PMT treatments increased endogenous GA, IAA, and ZR levels in flower buds during the early treatment phase (15 d after treatment), significantly reducing ABA levels. High-concentration PMT treatments significantly elevated GA3, IAA, and ZR levels during the later treatment phase (45 d after treatment). The elevated GA3, IAA, and ZR levels, combined with reduced ABA levels during the floral bud differentiation phase, promoted flowering. Exogenous PMT spraying induced physiological changes in the azalea plants, altering the timing and duration of flowering.

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of the Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions of the People's Republic of China (Grant No. 22KJA210002), the Higher Education Technological Innovation Team Program of the Education Department of Jiangsu Province, People's Republic of China (Grant No. [2023] 3), and the Engineering Research Center Program of Development & Reform Commission of Jiangsu Province, People's Republic of China (Grant No. [2021] 1368), the Science and Technology Plan Projects of Changzhou, Jiangsu Province, People's Republic of China (Grant No. CJ20250016).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Fu L, Zhang Z; data collection: Fu L, Jiang J; analysis and interpretation of results: Fu L, Jiang J, Wang K; draft manuscript preparation: Fu L, Zhang Z. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Effect of different concentrations of MT on soluble sugar in Rhododendron maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster'.

- Supplementary Table S2 Effect of different concentrations of MT on soluble protein in Rhododendron maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster'.

- Supplementary Table S3 Effect of different concentrations of MT on anthocyanin content of Rhododendron maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster'.

- Supplementary Table S4 Effect of Different Concentrations of MT on Endogenous IAA Content in Rhododendron maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster'.

- Supplementary Table S5 Effect of Different Concentrations of MT on Endogenous GA3 Content in Rhododendron maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster'.

- Supplementary Table S6 Effect of Different Concentrations of MT on Endogenous ABA Content in Rhododendron maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster'.

- Supplementary Table S7 Effect of Different Concentrations of MT on Endogenous ZR Content in Rhododendron maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster'.

- Supplementary Table S8 Effect of Different Concentrations of MT on Endogenous MT Content in Rhododendron maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster'.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Fu L, Jiang J, Wang K, Zhang Z. 2025. Concentration-dependent effects of exogenous phytomelatonin on flowering and physiological changes in azaleas (Rhododendron maculiferum). Ornamental Plant Research 5: e043 doi: 10.48130/opr-0025-0039

Concentration-dependent effects of exogenous phytomelatonin on flowering and physiological changes in azaleas (Rhododendron maculiferum)

- Received: 13 February 2025

- Revised: 18 August 2025

- Accepted: 03 September 2025

- Published online: 05 November 2025

Abstract: The effects of exogenous phytomelatonin (PMT) on the flowering and physiology of azaleas were investigated in the cultivar Rhododendron maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster'. Experimental plants in the budding stage were treated with PMT at concentrations of 100, 300, 500 μmol·L−1, 1, 3, and 5 mmol·L−1, with water serving as the control group. The results showed a concentration-dependent effect of exogenous PMT, with low concentrations promoting flowering and high concentrations delaying flowering. The sequence of flowering was as follows: PMT2 (300 µmol∙L−1) > PMT1 (100 µmol∙L−1) > PMT3 (500 µmol∙L−1) = CK > PMT4 (1 mmol∙L−1) > PMT5 (3 mmol∙L−1) > PMT6 (5 mmol∙L−1). All treatments extended the flowering duration, with the longest duration observed under PMT2 (32 d). PMT treatment significantly enhanced endogenous nutrient levels. Compared to the control, low-concentration PMT treatments increased the endogenous gibberellic acid (GA3), indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), and zeatin riboside (ZR) levels of flower buds in the early treatment phase (15 d after treatment) while significantly decreasing abscisic acid (ABA) levels. High-concentration PMT treatments significantly increased GA3, IAA, and ZR levels in the later treatment phase (45 d after treatment). High GA3, IAA, ZR, and low ABA levels promoted flowering during the floral bud differentiation phase. Exogenous PMT spraying induced physiological changes in R. maculiferum 'Pink Round Cluster' while altering its flowering time and duration. These findings provide theoretical support for regulating the flowering duration in azaleas by exogenous PMT and its application in the floriculture industry.

-

Key words:

- Azalea /

- Phytomelatonin /

- Physiological effects /

- Endogenous nutrients /

- Endogenous hormone