-

Horticultural plants include a diverse range of species, such as fruit trees, vegetables, tea trees, ornamental plants, and medicinal plants. Characterized by relatively small-scale cultivation and high economic efficiency, they are closely associated with human life. Current research on horticultural plants involve multiple dimensions, mainly focusing on aspects like flower development, fruit development, disease resistance, abiotic stress responses, senescence, and so on. In recent years, with the development of molecular biology and sequencing technology, more and more studies have used transcriptome sequencing and multi-omics methods to explore the mechanisms underlying complex traits of horticultural plants, most of which directly sampled and sequenced an entire plant tissue. However, as multicellular organisms, horticultural plants exhibit complicated cellular heterogeneity. The sampling method above involves mixing various types of cells in the target tissue, and the final result is the average expression of all cell types, which often ignores the cell heterogeneity, resulting in inaccurate sequencing results.

Single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) methods enable unbiased, high-throughput, and high-resolution transcriptomic analysis of individual cells[1]. With the help of conserved marker genes, different cell types could be identified, providing an accurate cell expression atlas. Since the first application of scRNA-seq technology in plant studies in 2017[2], cell types have been identified in different tissues of many plant species using this technology in recent years, and the development, metabolism, senescence, abiotic stress, disease resistance, and other processes of these plants have been preliminarily analyzed. In the process of scRNA-seq, it is generally impossible to obtain the spatial position of cells in tissue and the interactions among cells, while spatial transcriptomic (ST) technology enables investigating the heterogeneity of single cells and defining cell types, while preserving their spatial information[3]. Hence, single-cell and spatial transcriptomics, as well as their combined applications, have great potential in the study of horticultural plants, which could accelerate the precise analysis of gene functions and locate candidate genes in genetic engineering breeding. This review summarizes the application of single-cell and spatial transcriptomics in plant research, as well as their prospects and challenges in horticultural plants, providing new ideas for future horticultural plant studies.

-

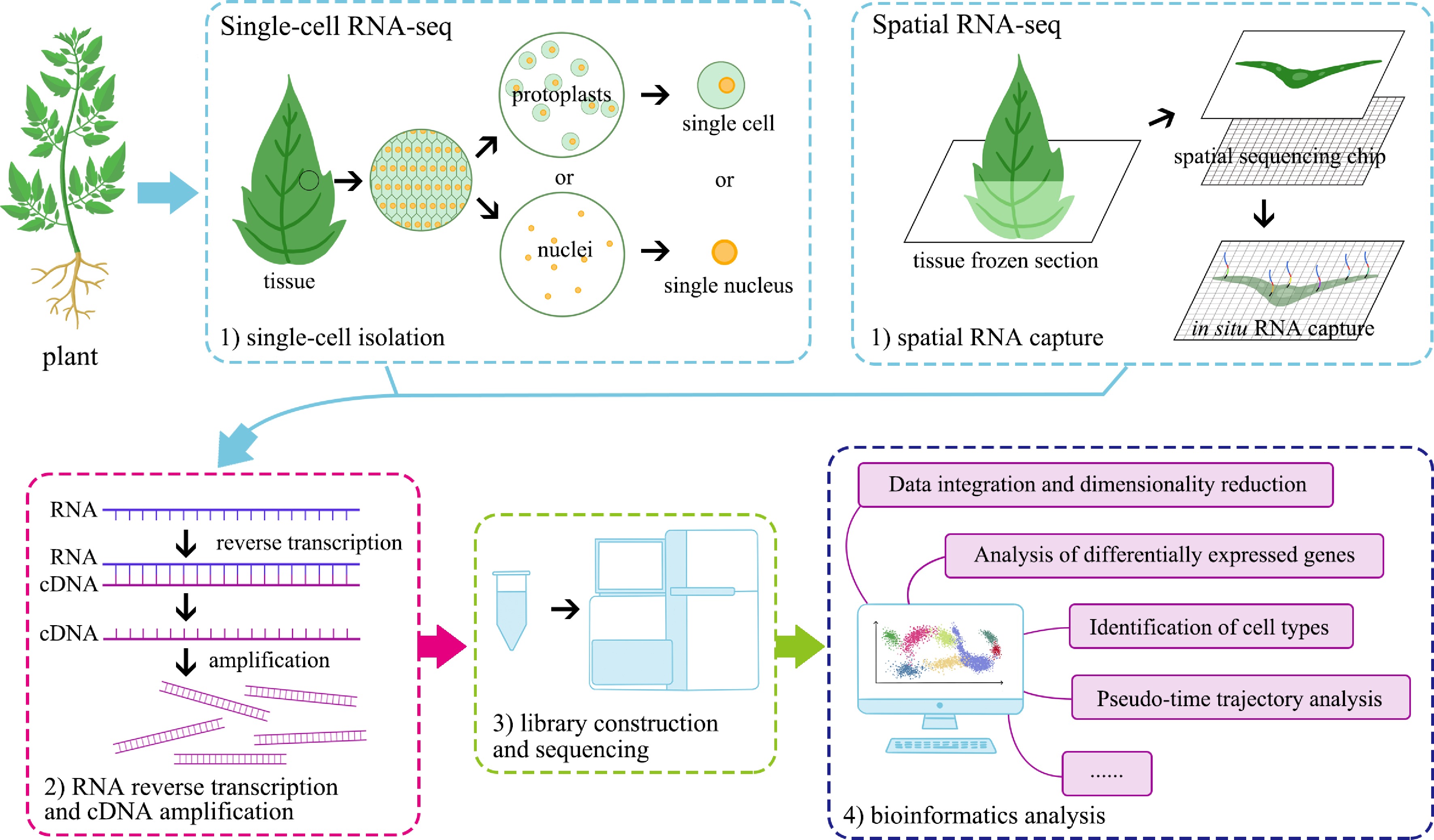

Early single-cell experiments were motivated by the prospect of an in-depth analysis of gene expression in a few precious cells[4], and with the development and improvement of technologies, Tang et al. conducted the first complete mRNA sequencing of mouse blastomere single cell, marking the start point of single-cell transcriptomic technology[5]. Subsequently, from studying only a few single cells to high-throughput single-cell isolation and sequencing, currently, the number of cells detected can reach up to hundreds of thousands[4,6]. Single-cell transcriptome analysis mainly involves the following four steps: (1) single-cell isolation; (2) RNA reverse transcription and cDNA amplification; (3) library construction and sequencing; and (4) bioinformatics analysis (Fig. 1)[7]. Single-cell isolation techniques include low-throughput technologies such as micropipette micromanipulation[8], laser capture microdissection (LCM)[9], fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS)[10], as well as high-throughput technologies such as microfluidics[11], microdroplets[12,13], and microwells[14,15]. With the development and commercialization of single-cell technologies, an increasing number of scRNA-seq platforms have emerged, such as Smart-seq (as well as Smart-seq2 and Smart-seq3) for low throughput[16−18], Fluidigm C1 platform based on microfluidic chips[19], BD Rhapsody platform based on Cyto-seq technology[20,21], and 10x Genomics Chromium platform based on Drop-seq[6,22]. Due to its high sequencing throughput, high stability, and relatively low cost, the 10x Genomics platform has been widely used in single-cell sequencing in plant studies (Supplementary Table S1). Through data filtering, integration, and dimensionality reduction, sequenced cells can be classified into distinct clusters. These clusters are further identified by marker genes that are specifically expressed within each cluster, thereby facilitating the annotation of cell types. Additionally, pseudo-time analysis offers valuable insights into the developmental trajectories of cells, providing a reference for understanding the directionality of cellular differentiation and maturation.

Although scRNA-seq has addressed the issue of cellular heterogeneity, it dissociates all types of cells from the tissue, inevitably leading to the loss of their original spatial location information during library preparation. This makes it challenging to reconstruct the native spatial organization of cells and the interactions between different cell types. Therefore, by integrating some in situ imaging and molecular sequencing methods, the technology of spatial RNA sequencing (spatial RNA-seq) has emerged, which not only captures gene expression profiles but also preserves and links the spatial information of cells within tissues[23]. Similarly, spatial RNA-seq was first developed in animal and human studies, and its application in plant studies is lagging behind[3]. In 2017, Giacomello et al. optimized and expanded the spatial RNA-seq system previously used only in mammals, conducting high-throughput and high-resolution spatial RNA-seq in three model plants for the first time[24]. Spatial RNA-seq technologies can be broadly categorized into targeted and non-targeted approaches. Targeted methods include tissue- or single-cell-specific sequencing techniques such as LCM-seq[25], as well as in situ detection technologies to measure the expression levels of specific genes, exemplified by seqFISH[26]. In contrast, non-targeted methods rely on in situ RNA capture techniques, such as ST-seq[27], slide-seq[28], Stereo-seq[29], and so on. Due to the low throughput, high cost, and difficulty of targeted spatial transcriptome sequencing methods, plant studies generally utilize non-targeted sequencing techniques, especially 10x Genomics' commercial platform 10x Visium, and BGI Genomics' Stereo-seq, which were the most widely used (Supplementary Table S1). The sequencing and analysis pipeline of this technology is similar to that of scRNA-seq. However, during RNA capture, the tissues of interest must first be permeabilized onto a specialized chip through frozen section. Subsequently, RNA molecules are captured in situ through various methods, followed by reverse transcription and library construction for downstream analysis (Fig. 1)[30].

The integration of single-cell and spatial transcriptomic data represents a cutting-edge frontier in bioinformatics research. The primary objective is to map or deconvolve high-resolution cell-type annotations from scRNA-seq data onto spatial transcriptomics data, thereby resolving the fine-grained cellular composition of each spot or tissue region while preserving spatial context. Among the most widely used tools for this purpose is Seurat (v4 +), which enables the direct prediction and transfer of cell-type labels defined from scRNA-seq to spatial datasets[31]. Additionally, other methods such as SPOTlight[32], and Robust Cell Type Decomposition (RCTD)[33] can also effectively integrate expression matrices to infer spatial cell-type distributions. On another front, tools like CellChat[34], although not directly integrating expression matrices, facilitate functional data integration by leveraging cell-cell communication networks inferred from scRNA-seq data and validating their spatial proximity within tissue architectures.

-

In 2017, single-cell and spatial transcriptome techniques were first used in plant studies, respectively[2,24]. Han et al. isolated protoplasts from rice (Oryza sativa) and performed RNA sequencing of mesophyll cells by adapting the single-cell library construction protocol originally developed for mouse studies[2]. Although only 32 cells passed quality control and were fully analyzed, this work represents the first successful application of single-cell sequencing in plant systems despite various difficulties. In the same year, Giacomello et al. performed spatial RNA-seq in the inflorescence meristem of Arabidopsis thaliana, the leaf buds of Populus tremula, and the female cones of Picea abies based on in situ RNA capture techniques, respectively[24]. These exemplary species and tissues represent a broad catalogue of histologically and biologically variable samples across herbaceous and woody plant model systems of the distant angiosperm and gymnosperm phylogenetic groups, illustrating the wide applicability of this technique in plant studies.

Summary of publications on plant research using single-cell and spatial transcriptomics

-

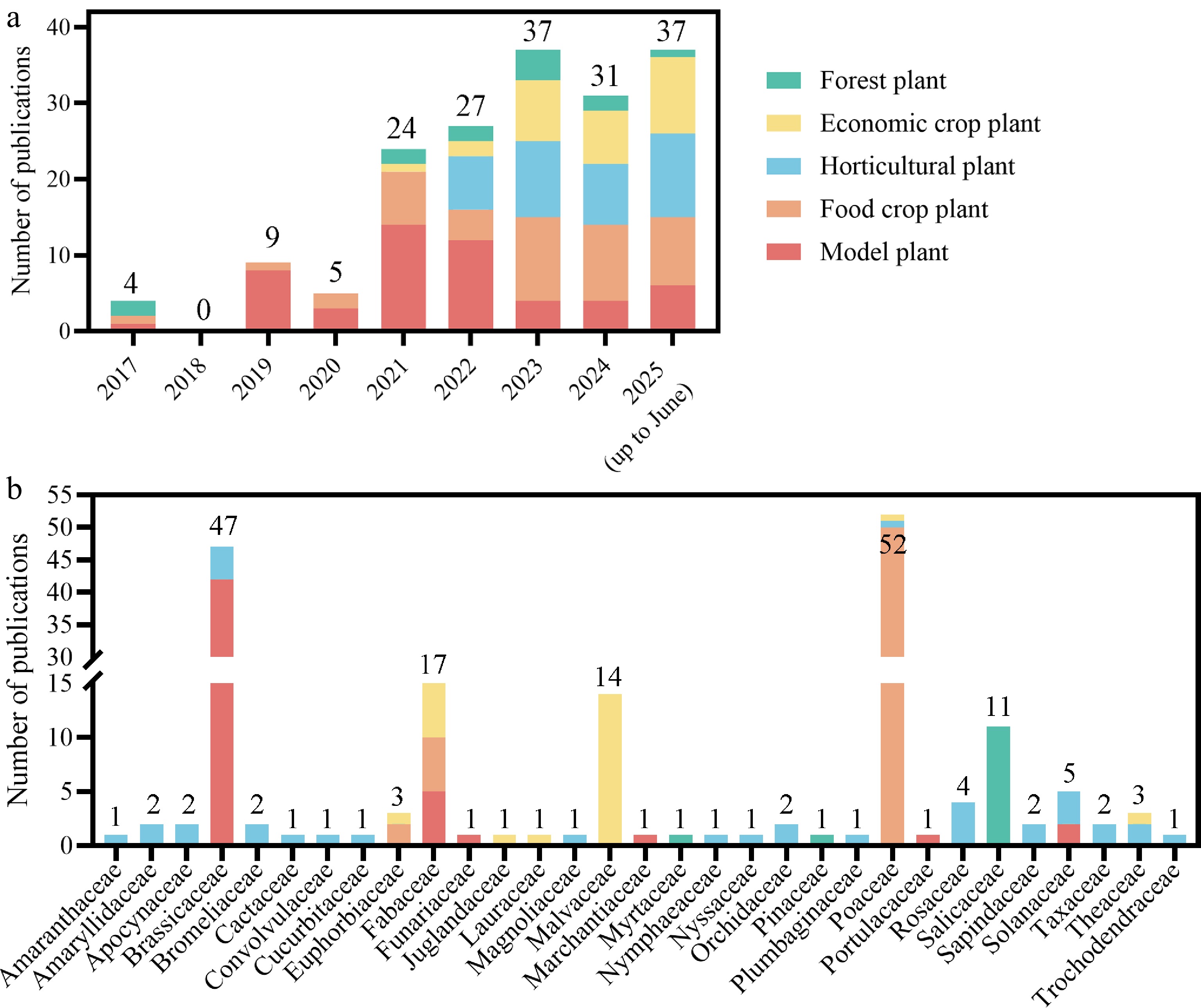

Here, 174 publications from 2017 to 2025 (up to June 30th) that utilized single-cell and spatial transcriptomics technologies in plant research were compiled (Supplementary Table S1). By 2025, these two technologies have been successfully applied in studies of numerous plant species (Table 1). For ease of categorization, all included plant species were classified into five groups based on their applications: (1) forest plants, including Eucalyptus grandis, Picea abies, Populus alba, Populus tremula, etc.; (2) economic crop plants, including peanut (Arachis hypogaea), oil-tea camellia (Camellia oleifera), cotton (Gossypium hirsutum), rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis), etc.; (3) horticultural plants, including tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), tea (Camellia sinensis), strawberry (Fragaria vesca), mei (Prunus mume), etc.; (4) food crop plants, such as cassava (Manihot esculenta), rice, wheat (Triticum aestivum), maize (Zea mays), etc.; and (5) model plants (used for basic research), including A. thaliana, Lotus japonicus (a legume model plant), Medicago truncatula (a legume model plant), Physcomitrella patens (a moss model plant), and so on (Table 1).

Table 1. Plant species studied using single-cell and spatial transcriptome techniques.

Plant type Species Family Key traits Number of publications Model plant Arabidopsis thaliana Brassicaceae Inflorescence; roots; calli; etc. 42 Lotus japonicus Fabaceae Root nodules 2 Marchantia polymorpha Marchantiaceae Dormant gemmae; developing thalli 1 Medicago truncatula Fabaceae Root nodules 3 Nicotiana attenuata Solanaceae Corolla limbs; throat cups 1 Nicotiana tabacum Solanaceae Low-nitrogen resistance 1 Physcomitrella patens Funariaceae Leaves 1 Portulaca oleracea Portulacaceae Leaves 1 Total 8 6 52 Food crop plant Hordeum vulgare Poaceae Grains; embryos under ABA 2 Manihot esculenta Euphorbiaceae Leaves; tuberous roots 2 Oryza sativa Poaceae Leaves; roots; embryos; etc. 12 Pisum sativum Fabaceae Shoot apices under boron deficiency 1 Triticum aestivum Poaceae Root tips; grains under heat stress; grains; etc. 4 Zea mays Poaceae Anthers; ears; endosperms; etc. 22 Total 6 3 343 Horticultural plant Allium sativum Amaryllidaceae Bulb basal plates; bulbs 2 Amygdalus persica Rosaceae Flower buds 1 Brassica campestris Brassicaceae Root tips under salt stress 1 Brassica rapa Brassicaceae Heat resistance; young leaves; leaf vasculature 4 Camellia sinensis Theaceae Leaves; root tips 2 Camptotheca acuminata Nyssaceae Shoot apices 1 Catharanthus roseus Apocynaceae Leaves 2 Cucumis sativus Cucurbitaceae Inferior ovary 1 Dendrobium devonianum Orchidaceae Flower buds 1 Dimocarpus longan Sapindaceae Embryogenic callus 1 Euryale ferox Nymphaeaceae Leaves 1 Fragaria vesca Rosaceae Gray mold resistance 1 Hylocereus undatus Cactaceae Pericarps senescence 1 Ipomoea aquatica Convolvulaceae Root tips under Cd treatment 1 Limonium bicolor Plumbaginaceae Young leaves 1 Liriodendron chinense Magnoliaceae Stem-differentiating xylem 1 Litchi chinensis Sapindaceae Undetermined resting buds; vegetative buds; floral buds 1 Phalaenopsis Orchidaceae Inflorescences 1 Phyllostachys edulis Poaceae Basal root tips 1 Prunus mume Rosaceae Petals 1 Rosa hybrida Rosaceae Gray mold resistance 1 Solanum lycopersicum Solanaceae Root primordia; calli; ToCV resistance 3 Spinacia oleracea Amaranthaceae Inflorescences 1 Taxus mairei Taxaceae Leaves; young stems 2 Tillandsia duratii Bromeliaceae Leaves 1 Trochodendron aralioides Trochodendraceae Stem-differentiating xylem 1 Vriesea erythrodactylon Bromeliaceae Roots 1 Total 19 20 36 Economic crop plant Arachis hypogaea Fabaceae Leaves; roots; peg/pod tips; etc. 7 Bombax ceiba Malvaceae Ovary wall 1 Camellia oleifera Theaceae Ovaries 1 Cinnamomum camphora Lauraceae Leaves 1 Glycine max Fabaceae Root nodules and various tissues 4 Gossypium bickii Malvaceae Cotyledons 1 Gossypium hirsutum Malvaceae Ovules; hypocotyls; anthers; etc. 12 Hevea brasiliensis Euphorbiaceae Powdery mildew resistance 1 Juglans regia Juglandaceae Fruit 1 Saccharum spp. Poaceae Smut resistance 1 Total 10 7 30 Forest plants Eucalyptus grandis Myrtaceae Stem-differentiating xylem 1 Picea abies Pinaceae Female cones 1 Populus alba Salicaceae Bark; wood; apical buds 2 Populus alba × Populus glandulosa Salicaceae Xylem; stems 3 Populus alba × Populus tremula var. glandulosa Salicaceae Stem segments 1 Populus euramericana Salicaceae Stem internodes 1 Populus tremula Salicaceae Leaf buds 1 Populus tremula × alba Salicaceae Shoot apices 1 Populus trichocarpa Salicaceae Stems; stem-differentiating xylem 2 Total 9 3 13 Following the initial publication in plant research in 2017, the number of publications was only in single digits before 2020. Subsequently, in 2021, the number of publications utilizing single-cell and spatial transcriptomics technologies in plant research experienced an explosive growth, this number maintaining a high level over the following four years (2022–2025) (Fig. 2a). The year 2021 also marked the peak in the number of publications focused on model plants, and then it gradually declined over the next three years (2022–2024), with economic crop plants, horticultural plants, and food crop plants dominating the publication landscape (Fig. 2a). This shift indicates that the application of single-cell and spatial transcriptomics technologies has focused more on plants that are more closely related to human life. Research on horticultural plants began in 2022 and has remained at a high level over the past three years. Given their significance to various aspects of human life, the number of publications related to horticultural plants are predicted to continue to increase in the future.

Figure 2.

The number of publications utilizing single-cell and spatial transcriptome techniques for various types of plants, (a) from 2017 to 2025 (up to June 30th), and (b) in different families.

Plant research using single-cell and spatial transcriptomes involved 31 families, 19 of which include horticultural plants (Fig. 2b). Among all plant types, the highest number of publications was observed in the field of model plants, with a total of 52 (Table 1). Although the number of publications on horticultural plants is not the highest, this category encompasses the greatest diversity of species and families, with 27 species involved in 20 families, respectively (Table 1). This highlights the rich species diversity of horticultural plants and underscores the significant potential for applying single-cell and spatial transcriptome technologies in this field.

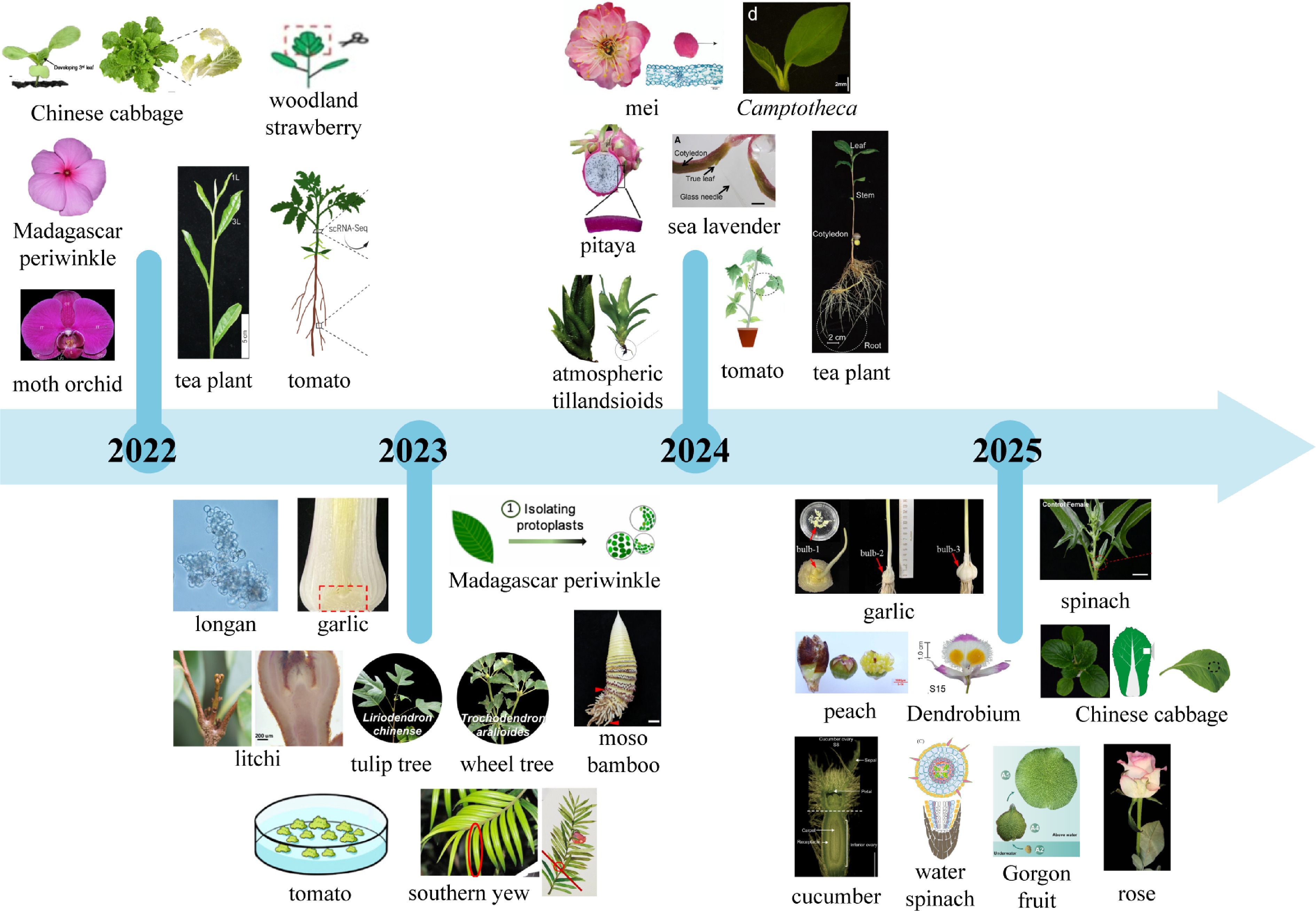

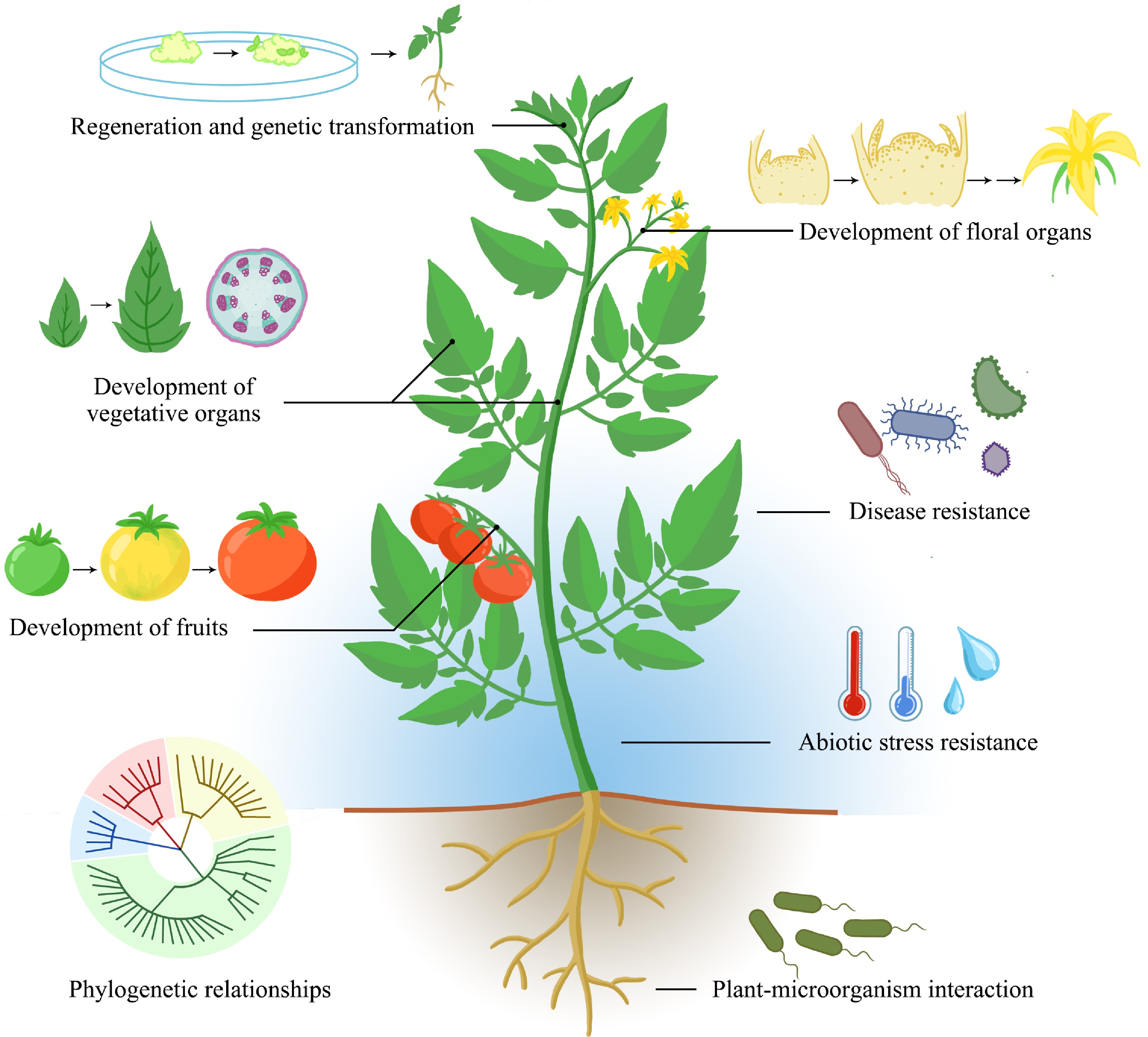

Here, horticultural plants studied using single-cell and spatial transcriptomics to date are summarized (Fig. 3). The first article, published in January 2022, employed scRNA-seq to construct a single-cell transcriptomic atlas of woodland strawberry (F. vesca) leaves during early infection by Botrytis cinerea[35]. This study analyzed over 50,000 single cells and successfully identified 12 distinct cell types. It represents not only the first application of scRNA-seq in a horticultural plant species but also its pioneering use in the investigation of plant-pathogen interactions. In the field of spatial transcriptomics, the spatiotemporal gene expression atlas during early floral organ development in Phalaenopsis Big Chili was constructed for the first time using the 10x Visium platform[36]. This study revealed that AGL6-like genes exhibit specific expression in the lip and tepals, potentially substituting for the conventional A-function in the 'ABC model' and contributing to the identity determination of orchid-specific floral organs. This work represents the first application of spatial transcriptomic technology in horticultural plants, systematically deciphering the molecular mechanisms underlying the complex floral organ development in orchids. To date, single-cell and spatial transcriptomic technologies have been successfully applied to various horticultural plant species, facilitating advances in areas such as development, stress resistance, regeneration, and metabolism (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Horticultural plants studied using single-cell and spatial transcriptomes from 2022 to 2025 (up to June 30th).

Cell types and marker genes

-

Unsupervised dimensionality reduction methods such as the t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE), and the Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) can be applied to single-cell and spatial transcriptomic data. These methods enable the identification of distinct cell clusters. By analyzing the expression patterns of marker genes and their corresponding spatial locations, these cell clusters can be annotated to specific cell types. This study summarized the cell types identified in different tissues of horticultural plants (up to June 30th, 2025, Table 2). Within the same tissue across different species, there exist some highly conserved cell types. For instance, the roots of various plants species generally possess the following cell types: epidermis, cortex, stele, root cap, meristem/initial cells, phloem, and xylem; likewise, leaves universally comprise core constituent cell types such as mesophyll, epidermis, guard cells, and vasculature. Meanwhile, some plants have also evolved specialized cell types to adapt to their specific ecological niches, physiological functions, and microenvironments. Velamen cells were found in the roots of the epiphytic bromeliad Vriesea erythrodactylon[37]. These cells constitute a specialized water-absorbing tissue commonly found in epiphytic orchids. The idioblast cells uniquely found in Catharanthus roseus leaves serve as the 'terminal' cells in the monoterpenoid indole alkaloid (MIA) biosynthetic pathway, primarily involved in the synthesis and storage of MIAs[38,39]. Limonium bicolor is a recretohalophyte. Its salt tolerance is attributed to the presence of salt gland-associated epidermal cells on the leaf epidermis, which actively secrete excess Na+ out of the plant body[40].

Table 2. Cell types of horticultural plant tissues.

Species Tissue Cell types Ref. Allium sativum Bulb basal plates Xylem-type cells; stem cells; epidermis cells; sieve cells; proliferative cells; etc. Wang et al.[41] Allium sativum Bulbs Meristem cells; parenchyma cells; etc. Gao et al.[42] Amygdalus persica Flower buds Sepal; petal; stamen and filament; style; etc. Zhao et al.[43] Brassica campestris Root tips Root hair; epidermis; cortex; endodermis; stele; root cap; dividing cells; initial cells. Liu et al.[44] Brassica rapa Shoot apices and leaves Meristem cells; mesophyll cells; epidermal cells; guard cells; vascular cells; proliferating cells; etc. Sun et al.[45] Brassica rapa Young leaves Mesophyll cells; epidermis; vasculature; bundle sheath; guard cells; proliferating cells; phloem; xylem. Guo et al.[46] Brassica rapa Leaf vasculature Xylem parenchyma; tracheary elements; phloem parenchyma; companion cells; sieve elements; procambium cells; procambium cells with xylem features; unknown vascular cells. Guo et al.[47] Brassica rapa Young leaves Mesophyll cells; epidermal cells; guard cells; vascular cells; proliferating cells; etc. Zhang et al.[48] Camellia sinensis Leaves Epidermis cells; mesophyll cells; vascular bundle cells; proliferating cells; etc. Wang et al.[49] Camellia sinensis Root tips Xylem; epidermis; stem cell niche; cortex/endodermis; root cap; cambium; phloem; pericycle. Lin et al.[50] Camptotheca acuminata Shoot apices and leaves Shoot apices: mesophyll cells; epidermal cells; vascular cells; proliferating cells; central zone. Leaves: mesophyll cells; epidermal cells; vascular cells; proliferating cells. Wang et al.[51] Catharanthus roseus Leaves Mesophyll cells; epidermal cells (young); epidermal cells (mature); guard cells; vascular cells; proliferating cells; idioblast cells; internal phloem-associated parenchyma; etc. Sun et al.[38] Catharanthus roseus Leaves and roots Leaves: internal phloem-associated parenchyma; epidermis; idioblast; mesophyll; vasculature; guard cell; etc. Roots: Ground tissue; epidermis; stele; root cap; meristem; etc. Li et al.[39] Cucumis sativus Floral buds Floral primordia; placenta; ovule; stigma/transmitting tract; sepal; petal/stamen; floral intercalary meristem; receptacle-early; receptacle-late; conjunctive tissue; epidermis; trichome; provascular; phloem; mesocarp/endocarp; G1/S phase cells; G2/M phase cells. Dong et al.[52] Dendrobium devonianum Flower buds Epidermal cells; vascular bundle cells; mesophyll cells; xylem cells; phloem cells; ovule cells; anther cells; guard cells; proliferating cells. Wang et al.[53] Dimocarpus longan Embryogenic callus Proliferating cells; meristematic cells; vascular cells; epidermal cells; etc. Zhang et al.[54] Euryale ferox Leaves Proliferating cells; epidermis cells; mesophyll cells; procambium cells; phloem cells; xylem cells; bundle sheath cells; hydathode cells; etc. Liu et al.[55] Fragaria vesca Leaves Hydathode cells; mesophyll cells; bundle sheath cells; upper epidermal cells; phloem cells; lower epidermal cells; xylem parenchymal cells; meristem cells; xylem cells; etc. Bai et al.[35] Hylocereus undatus Pericarps Exocarp cells; mesocarp cells; endocarp cells; endocarp fiber cells; vascular bundle cells. Li et al.[56] Ipomoea aquatica Root tips Epidermis cells; cortex cells; endodermis cells; root cap cells; sub-cell type of stele; trichoblast cells; phloem cells; xylem cells; pericycle cells; procambium cells. Shen et al.[57] Limonium bicolor Young leaves Promeristem cells; epidermal cells; mesophyll cells; vascular tissue cells; salt gland-associated epidermal-cell subclusters. Zhao et al.[40] Liriodendron chinense Stem-differentiating xylem Ray organizer cells; ray precursor cells; ray parenchyma cells; fusiform organizer cells; fusiform early precursor cells; fusiform intermediate precursor cells; vessel elements; libriform fibers; tracheids. Tung et al.[58] Litchi chinensis Undetermined resting buds; vegetative buds; floral buds Mesophyll cells; epidermis cells; meristem cells; G1/S proliferating cells; G2/M proliferating cells; cortex cells; guard cells; floral meristem cells (Exists only in floral buds.); etc. Yang et al.[59] Phalaenopsis Inflorescences Inflorescence meristem cells; floral meristem cells; tepal cells; lip cells; column cells; pollinium cells; bract cells; primordium cells. Liu et al.[36] Phyllostachys edulis Basal root tips Root cap cells; epidermis cells; ground tissue cells; initial cells; transition cells; etc. Cheng et al.[60] Prunus mume Petals Epidermal cells; parenchyma cells; xylem parenchyma cells; phloem parenchyma cells; xylem vessels and fibers; sieve element-companion cell complex; etc. Guo et al.[61] Rosa hybrida Petals Epidermal cells; epidermis/Fra cells; xylem cells; phloem cells; petal mesophyll cells; guard cells; bundle sheath cells. Li et al.[62] Solanum lycopersicum Shoot-borne root primordia Phloem parenchyma cells; transition cells; root cap/initial cells; cambium cells; phloem companion cells; procambium cells; vasculature initials. Omary et al.[63] Solanum lycopersicum Calli Epidermis cells; vascular tissue cells; shoot primordia cells; inner callus cells; chlorenchyma cells. Song et al.[64] Solanum lycopersicum Leaves Mesophyll cells; epidermal cells; guard cells; vascular cells; trichome cells; proliferating cells. Yue et al.[65] Spinacia oleracea Inflorescences Vegetative shoot apical meristem cells; Inflorescence meristem/flower primordia cells; bract primordia/bract cells; epidermal cells; cortex cells; pith cells; pith rib meristem cells; basal bud cells. You et al.[66] Taxus mairei Leaves Bundle sheath cells; vein cells; mesophyll cells; stomatal complex cells; guard cells; epidermal cells; vascular cells; procambium cells; phloem cells; leaf pavement cells. Zhan et al.[67] Taxus mairei Young stems Xylem parenchyma cells; xylem cells; epidermal cells; photosynthetic/cork cells; vascular cells; xylem mother cells; companion cells & phloem cells; endodermal cells; cambium region and sieve element cells. Yu et al.[68] Tillandsia duratii Leaves Trichome cells; mesophyll cells; epidermal cells; vascular cells. Lyu et al.[37] Trochodendron aralioides Stem-differentiating xylem Ray organizer cells; ray precursor cells; ray parenchyma cells; fusiform organizer cells; fusiform early precursor cells; fusiform intermediate precursor cells; tracheids. Tung et al.[58] Vriesea erythrodactylon Roots Cortex cells; velamen cells; stele cells; meristem cells. Lyu et al.[37] Marker genes play a pivotal role in identifying cell types. Here, marker genes for various tissues and cell types in ornamental plants (including other plants with ornamental value) are summarized (Supplementary Table S2). Some marker genes are highly conserved across the same cell types. Mesophyll cells of nearly all species have marker genes related to photosynthesis; marker genes for epidermal cells function similarly in different species, primarily involved in cuticle formation and epidermal differentiation; for vascular tissues, marker genes are mainly associated with functions in sugar transport and cell wall synthesis; marker genes for meristems and proliferating cells are largely related to the cell cycle (such as Cyclin, CDK, and histone), and stem cells (such as WUSCHEL, WOX, and AGO). The ABCE model of flower organ development is widely applicable in angiosperms. Therefore, some MADS-box transcription factor genes are often used as marker genes for flower organ identity. For example, AG2 (AGAMOUS 2) is a marker gene for the ovule of Dendrobium devonianum[53], while the AG subfamily is a key determinant of the identity of carpels and stamens. However, the marker genes of petals are relatively less conserved. These genes are generally related to color, aroma, and morphology, and have strong species specificity. The marker genes for peach (Amygdalus persica) petals belong to the WRKY transcription factor family[43]. The marker genes for the epidermis of mei (Prunus mume) petals include non-specific lipid-transfer protein 1-like and GDSL esterase/lipase EXL3-like[61], while the marker genes for the epidermis of rose (Rosa hybrida) petals include 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase 6[62], and these genes are all related to cutin synthesis. Reviewing the published marker genes is helpful for future studies on single-cell or spatial transcriptomes of ornamental plants, as it enables the identification of cell types through homologous genes.

Although single-cell or spatial RNA-seq has been successfully conducted in many plant species and tissues, these two technologies are not mature enough in plant fields and the researchers have not determined the universal plan, strategies, and analysis methods[69]. Therefore, plant research, particularly in horticultural plants, continues to encounter significant challenges that need further investigation and resolution.

-

In recent years, with the rapid advancement of biotechnological methods, in addition to single-cell and spatial transcriptomics, a diverse array of single-cell or spatial omics technologies has emerged, such as single-cell epigenomics, proteomics, and metabolomics. These techniques have demonstrated substantial potential in biological research, with several applications already being successfully implemented in plants[70,71]. Single-cell epigenomics approaches utilize chemical treatment of DNA (bisulfite conversion), immunoprecipitation, or enzymatic digestion (e.g., by DNaseI) to study DNA modifications (scBS-seq and scRRBS), histone modifications (scChIP-seq), DNA accessibility (scATAC-seq, scDNase-seq), chromatin conformation (scDamID, scHiC)[72]. Among them, scATAC-seq has been utilized in several plant species[44,73−81]. For example, Cui et al. conducted single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) combined with single-nucleus ATAC sequencing (snATAC-seq) to provide comprehensive information on specific cell types, gene expression, and chromatin accessibility during the early stages of peanut fruit-pod development, providing insights into the mechanisms of peanut pod development[73]. Single-cell proteomics aims to identify and quantify the proteomes of individual cells, which can play an important role in elucidating the protein expression patterns at the single-cell level[71]. The application of this technology in plant research remains relatively limited, but researchers have successfully employed LCM to isolate specific cell types from tomato root tips and combined with tandem mass tags (TMTs) to study the protein responses of different cell types under aluminum stress[82]. Single-cell and spatial metabolomics can detect complete small-molecule metabolites in specific tissues or cells, is a direct indicator of phenotypic diversity of single cells, and a nearly immediate readout of how cells react to environmental influences[83,84]. At present, some mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) technologies have been applied to the studies of plant spatial metabolomics[84], which can show the spatial distribution of metabolites. For example, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) is the most widely used MSI technology in plant research[85−88].

The above single-cell and spatial omics are also relatively new technologies, most of which are still immature in plant study. Future research can learn more from the relevant research methods in animals, and innovate based on some unique attributes of plants to develop more universal methods for plants. Additionally, the combined application of single-cell and spatial multi-omics can also help to more deeply and intuitively analyze the growth and development mechanisms of plants in various aspects.

-

As cutting-edge technologies in contemporary plant research, single-cell and spatial transcriptomics hold tremendous potential for applications in horticultural plants. However, the full realization of their capabilities in this field faces significant challenges, primarily due to inherent technical limitations and the complexity of horticulture species. This section will provide a comprehensive review of both the promising applications and existing challenges associated with these technologies in horticultural plant research, aiming to provide novel insights and perspectives for future investigations in horticultural plants (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Application prospects of single-cell and spatial transcriptome techniques in horticultural plants.

Application prospects

Regeneration and genetic transformation

-

The powerful regeneration ability of plants can not only enable plants to repair damaged tissues and organs, but also generate new plants. This ability has been widely used in the field of modern agriculture, such as the use of tissue culture technology for rapid propagation of plants in vitro, which is of great significance to accelerate the production efficiency of horticultural plants. Furthermore, plant regeneration serves as a fundamental prerequisite for genetic transformation, playing an important role in gene function validation and molecular breeding of horticultural plants. The application of single-cell and spatial transcriptomic technologies in elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying plant regeneration offers opportunities to enhance regeneration efficiency. Such insights could significantly accelerate molecular breeding programs by facilitating the development of optimized regeneration protocols for horticultural plants. In the model plant A. thaliana, scRNA-seq analysis showed that the tissue structure of callus was similar to the root apical meristem, and the middle cell layer produced endogenous auxin, showing a strong ability of organ regeneration[89]. In horticultural plants, Song et al. analyzed the spatial transcriptome of tomato callus and revealed the shoot regeneration mechanism in chlorenchyma cells induced by light[64]. In addition, the high-resolution single-cell RNA atlas of embryogenic calli of longan (Dimocarpus longan) showed the direction of cell division and differentiation in the process of somatic embryogenesis, and some key transcriptional regulators related to cell fate were revealed by pseudo-time trajectory analysis[54].

Development of vegetative organs

-

Vegetative organs are essential for sustaining fundamental plant processes such as photosynthesis, structural support, and nutrient uptake. Under certain specific conditions, they can also reproduce asexually. Plants have evolved diverse organ morphologies—including simple and compound leaves, erect or creeping stems, and taproot or fibrous root systems—enhancing environmental adaptability and reproductive success. Horticultural plants, after multiple generations of hybridization and selective breeding, have more diverse and valuable vegetative organs. Examples include the storage roots of carrot (Daucus carota), the edible leaves of cabbage (Brassica oleracea), the stolons of strawberry (F. × ananassa), and the medicinal roots of tree peony (Paeonia suffruticosa). Moreover, the vegetative organs of many plants can also be used for ornamental purposes, such as the red leaves of Acer palmatum. The study of the vegetative organs of horticultural plants using single-cell and spatial transcriptome technologies can accelerate the understanding of their development mechanisms, which is helpful for subsequent molecular breeding and enriching the germplasm resources of horticultural plants. ScRNA-seq of basal roots of moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) revealed their development trajectory and clarified key factors determining cell fate[60]. To investigate the biosynthetic pathway of medicinally valuable monoterpenoid indole alkaloids (MIAs) in Catharanthus roseus, Sun et al. performed scRNA-seq on the leaf tissues, identifying 20 MIA-related gene transcripts and updating the model of MIA biosynthesis[38]. L-theanine is an important quality component of tea, which is primarily synthesized in roots and then transported to new shoots of tea plants. ScRNA-seq of tea roots enabled cell-type-specific analysis of glutamate and ethylamine (two precursors of theanine biosynthesis) metabolism, and theanine biosynthesis, storage, and transport[50].

Floral organ development and floral ornamental characteristics

-

As reproductive organs of plants, flowers develop into fruits and seeds through sexual reproduction. Their morphological and sensory traits (such as color, shape, and scent) serve to attract pollinators, thereby ensuring species survival. In horticultural plants, floral traits directly influence economic value. Fruit yield depends on flower bud number and bloom timing, while ornamental value derives from color, form, and fragrance. Additionally, floral volatiles are commercially valuable in perfume production. In terms of flower organ development, the classic ABC regulatory model was proposed long ago and has been further refined through extensive research, which can explain the differentiation mechanisms of sepals, petals, stamens, and carpels in dicotyledonous plants[90]. Recent advances in single-cell and spatial transcriptomics provide new tools to investigate cell-type-specific developmental trajectories during floral formation. Moreover, by analyzing the biosynthetic pathways of some metabolites, the regulatory mechanisms of traits such as floral color and scents can be elucidated, laying a foundation for subsequent breeding work. In horticultural plants, the Orchidaceae family is notably rich in species and exhibits diverse and unique floral structures. Spatial transcriptomic analysis of early floral organs in Phalaenopsis Big Chili has unveiled spatiotemporal gene expression patterns across different stages, providing a valuable resource for further research on floral development[36]. The snRNA-seq analysis on the terminal buds of litchi (Litchi chinensis) revealed genes related to the regulation of the transformation from leaf bud to flower bud[59]. By integrating scRNA-seq with bulk RNA-seq and volatile metabolome, Guo et al. identified genes related to the synthesis of floral volatiles in mei (Prunus mume) petals, providing a reference for further exploration of petal cell types in horticultural plants and for understanding the potential molecular mechanisms underlying the synthesis of floral volatiles[61]. In addition to aromatic characteristics, floral forms defined by the combinatorial variations in the number and arrangement of floral organs represent a key ornamental trait in mei. By performing spatial RNA-seq on floral buds at distinct developmental stages, it is possible to visually map the spatial expression patterns of genes that determine the identity and number of floral organs. This approach provides a powerful means to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the formation of complex floral architectures in mei. Through spatial transcriptomic analysis and cell lineage reconstruction during cucumber floral bud differentiation, Dong et al. revealed the mechanisms underlying inferior ovary formation and unisexual flower development in cucurbit species, and identified the critical role of the KNAT2-like1 gene in these processes[52].

Fruit development and fruit characteristics

-

Fruits, which develop primarily from the ovary after fertilization, function as key reproductive structures in plants. Some species form fruits from additional floral tissues such as the receptacle or calyx, resulting in structurally complex organs. The special structure (such as samara), color, taste, and other characteristics of fruits enable them to spread seeds with the help of wind or animals. It contains rich nutrients and is also conducive to seed germination. Therefore, the fruit is also important for species continuation. The fruits of horticultural plants are of great value in edible, medicinal, ornamental, and economic aspects. For example, strawberry (F. × ananassa) is known as the 'fruit queen', and its fruit is rich in vitamin C, folate, and phenolic constituents, with great nutritional value. Bioactive substances in blueberry (Vaccinium uliginosum) can improve obesity and have the effect of combating diabetes. Besides, plants like kumquat (Citrus japonica) and finger citron (C. medica 'Fingered') are often used as potted plants with ornamental fruits. In addition, the fruits of fruit trees and vegetables have high economic value as commodities. Therefore, for the development of the horticultural industry, it is very important to analyze the mechanism of fruit development and the regulation of fruit quality (flavor, aroma, hardness, nutrients, etc.). Using single-cell and spatial transcriptome technology, we can not only accurately analyze the differentiation trend of different types of cells in fruit development and provide a high-resolution fruit cell atlas, but also explore the biosynthesis pathway of quality-related metabolites such as fruit flavor and aroma, and provide gene resources for fruit quality improvement breeding. At present, only one study on horticultural plant fruit has applied both single-cell and spatial transcriptome technology: Li et al. combined single-cell with spatial transcriptome analysis, constructed the single-cell expression atlas of pitaya (Hylocereus undatus) pericarp during fruit senescence, determined the cell differentiation and gene expression trajectory of exocarp and mesocarp, and finally verified the central function of HuCBM1, an early response factor to fruit senescence[56].

Disease resistance

-

In nature, various pathogens and viruses invade plants, leading to the occurrence of plant diseases that threaten biodiversity and ecological balance. Utilizing plant species with disease resistance in production can reduce the use of chemical pesticides, promote food security, improve crop quality, and increase economic benefits. As horticultural plants are closely related to human life, using horticultural plants with strong disease resistance can ensure the food safety of edible plants and extend the viewing period of ornamental plants. Therefore, it is urgent to create excellent disease-resistant germplasm for horticultural plants. Plants cannot evade pathogen invasion by moving like animals, so they have evolved sophisticated immune mechanisms to respond to such attacks. Many plant-pathogen interaction patterns conform to the 'gene for gene' hypothesis, which suggests that for incompatibility (no disease), the presence of a resistant gene (R gene) in the plant and a corresponding avirulence gene (Avr gene) in the pathogen is necessary. The 'zigzag' model published by Jones & Dangl in 2006 provided a more detailed and in-depth interpretation of the plant immune system[91]. Identifying plant R genes can help cultivate new disease-resistant varieties. Furthermore, identifying the disease susceptibility genes of plants and knocking them out through gene editing techniques such as CRISPR/Cas9 is also a method for creating disease-resistant germplasm[92]. By analyzing the gene expression of different types of cells after pathogen infection through single-cell and spatial transcriptome techniques, key disease resistant cell types can be identified, and the gene regulatory network can be constructed. Subsequently, plant resistance proteins (R proteins) and their recognized pathogen effectors can be identified through single-cell proteomics or other methods. Bai et al. constructed a single-cell gene expression atlas of woodland strawberry (F. vesca) leaves infected by Botrytis cinerea, revealing signals of the transition from normal functioning to defense response in epidermal and mesophyll cells upon B. cinerea infection[35]. ScRNA-seq analysis of tomato leaves infected with tomato chlorosis virus (ToCV) showed that mesophyll cells exhibited a rapid function transition after infection, consistent with the pathological changes such as thinner leaves and decreased chloroplast lamellae. In addition, the researchers also analyzed the chlorophyll maintenance function of the selected F-box family gene SlSKIP2 during viral infection[65].

Abiotic stress resistance

-

Abiotic stress refers to environmental pressures caused by abiotic factors that are detrimental to plant growth and development, including water stress, temperature stress, salt stress, nutrient stress, and so on. Abiotic stress has a significant impact on the distribution of plant species in different types of environments and also limits crop productivity. Due to the potential impact of climate change on rainfall patterns, extreme temperatures, and other aspects, as well as human activities such as irrigation and fertilization causing land salinization, and the increasing demand for agricultural productivity due to population pressure, the impact of abiotic stress on plants in natural and agricultural environments has become an increasingly important topic of concern. In the production and utilization of horticultural plants, various abiotic stresses are also encountered. These abiotic stress factors often interact with each other, forming combined stresses that exert more complex impacts on horticultural plants. Understanding the response mechanisms of horticultural plants to abiotic stresses is of great significance for enhancing their stress resistance, ensuring food safety, and extending the ornamental period and post-harvest storage period. Through breeding, genetic engineering, and cultivation management, the resistance of horticultural plants to abiotic stresses can be enhanced, costs can be reduced, and production efficiency and sustainability can be improved. Single-cell and spatial transcriptome techniques have unique advantages in analyzing the heterogeneous responses of horticultural plants to abiotic stress. Compared to the bulk RNA-seq, scRNA-seq can provide information on the differences in the abiotic stress responses of different cell types, while the spatial RNA-seq can reveal the spatial distribution of the abiotic stress responses in tissues; thus both technologies can also provide new impetus to the classic question of horticultural plant physiology. For example, Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa ssp. pekinensis) experienced a whole-genome triplication (WGT) event and thus has three subgenomes. ScRNA-seq of leaves under heat stress showed that heat stress not only affects gene expression in a cell type-specific manner but also impacts subgenome dominance[45]. Some other plants and tissues have also used scRNA-seq to study the response mechanism of abiotic stress, such as cotton roots under salt stress[93], tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) leaves under low nitrogen stress[94], pea (Pisum sativum) shoot apices under boron deficiency[95].

Plant-microorganism interaction

-

In addition to pathogenic bacteria and fungi, there is also a type of microorganism that can interact with plants and have beneficial effects on plant growth. These microorganisms generally exist in the rhizosphere soil of plants, which can improve the growth and development of plant roots, increase their absorption of water and nutrients, enhance plant resistance to stress and disease, and increase plant biomass, such as nodule-forming nitrogen-fixing bacteria, arbuscular mycorrhizae, root endophytic bacteria and fungi. On the other hand, upon pathogen or insect attack, plants are able to recruit protective microorganisms and enhance microbial activity to suppress pathogens in the rhizosphere. Therefore, plant-microorganism interaction is very complex and crucial for plant health. The use of beneficial microorganisms in horticultural plant production can not only form induced systemic resistance (ISR) in plants for biological control, but also promote plant growth, increase yield, and reduce production costs. Recently, the analysis of plant-microorganism interaction mechanisms has also become one of the hotspots, and single-cell and spatial transcriptome sequencing provide new ideas for these studies. By analyzing the gene expression changes of different cell types after microbial symbiosis, key cell types and molecular mechanisms involved in the interactions can be identified, and key genes that determine cell fate can be screened. ScRNA-seq was performed on root nodules of the legume model plant M. truncatula, revealing the differentiation trajectories of root meristem cells with symbiotic and asymbiotic fate[96]. Serrano et al. combined single-nucleus and spatial transcriptome analysis to demonstrate the symbiotic process between M. truncatula and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi[97]. At present, the relevant publications focus on legumes, which can be used as a reference for future studies of horticultural plants.

Phylogenetic relationship analysis

-

The analysis of plant phylogenetic relationships is an important method for studying the genetic relationships and evolutionary history between plant species. Through various analysis methods (whole genome sequencing, genome-resequencing, plastid genome sequencing, genome structure, transcriptome, etc.), key information such as the evolutionary path, differentiation time, and adaptive evolution of plants can be revealed. Single-cell and spatial transcriptome techniques provide new strategies for analyzing plant phylogenetic relationships. The interspecific comparison of single-cell and spatial transcriptomes can comprehensively analyze the evolutionary relationships of horticultural plants from both cellular and spatial dimensions, and elucidate the origin and evolution of specific agronomic traits. Due to difficulties in cell type identification and interspecies data integration, such studies have not yet emerged in plants. However, with the development of technology, it is reasonable to expect that these two techniques would play an important role in phylogenetic analysis in the future.

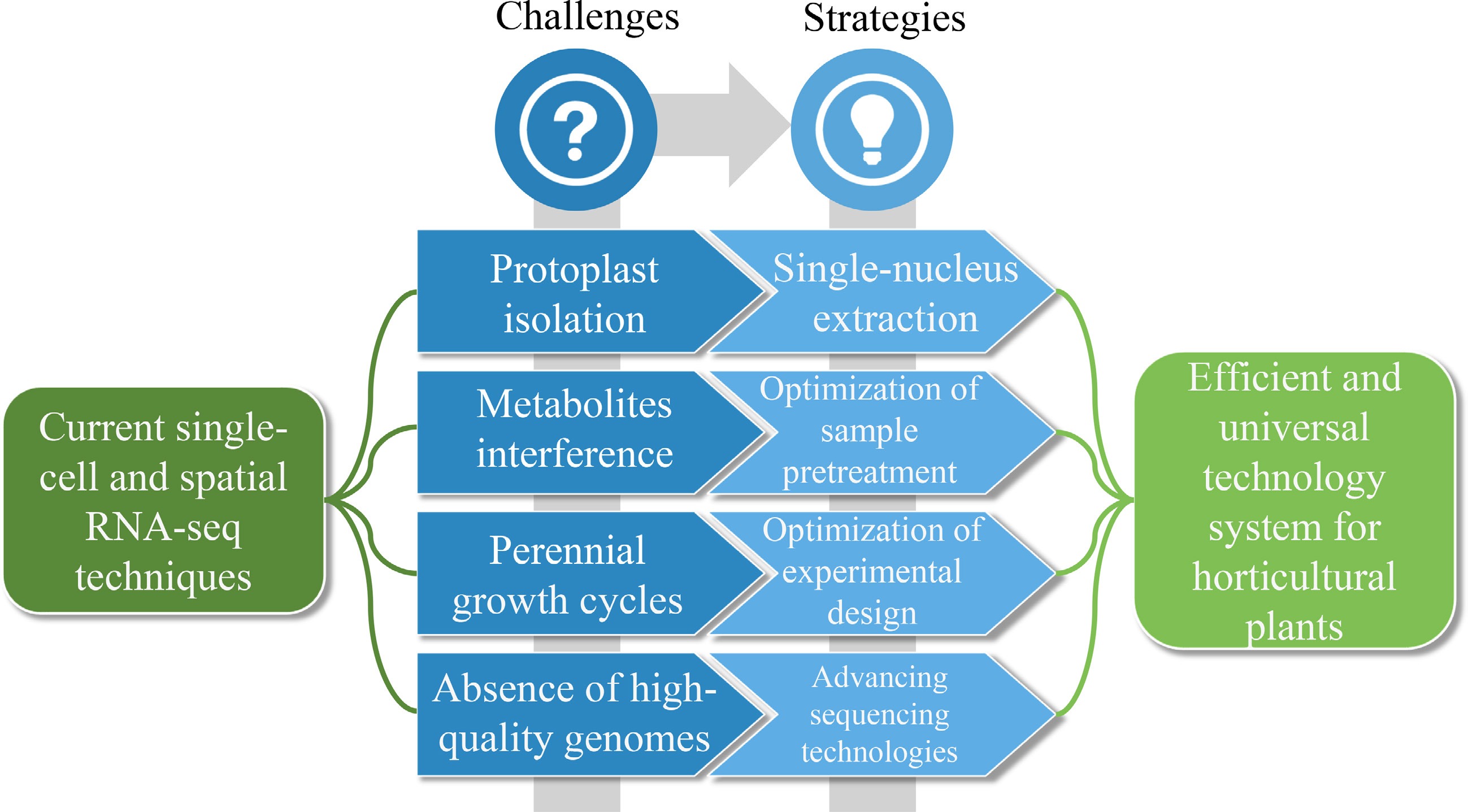

Challenges and strategies

-

Although single-cell and spatial transcriptomics hold immense potential for future research in horticultural plants, there are several challenges that must be overcome before their full potential can be realized. For all plant species, there are some common difficulties in aspects such as single-cell isolation, cryosection, cell type identification, and data analysis. In addition, some of the difficulties in applying single-cell and spatial transcriptomics, particularly to horticultural plants are outlined, as well as potential directions for future technological innovations (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Challenges and strategies for single-cell and spatial transcriptome applications in horticultural plants.

Structural complexity and protoplast isolation efficiency

-

Many horticultural plants, particularly fruit trees (such as apple and citrus) and ornamental trees, possess tissues (e.g., xylem, phloem, and flesh) with abnormally thickened and highly lignified cell walls. This renders conventional enzymatic digestion protocols (using cellulase and pectinase) inefficient, resulting in low yields and poor viability of protoplasts. However, more critically, such recalcitrance varies significantly among different cell types. For instance, thick-walled fiber cells may resist complete digestion, whereas thin-walled parenchyma cells are prone to over-digestion and rupture. This selective digestion bias directly leads to single-cell suspensions that fail to accurately represent the original cellular composition of the tissue. As a result, certain cell populations with specialized cell wall components may be entirely lost or substantially underrepresented, thereby introducing systematic bias into subsequent cell atlas construction.

Specialized metabolite interference

-

Horticultural plants are typically rich in secondary metabolites, such as pigments (anthocyanins), aromatic compounds (terpenes), tannins, and alkaloids. During sample preparation, the release of these compounds can be substantial. On one hand, they may inhibit the activity of reverse transcriptase and PCR enzymes, leading to failures or biases in cDNA library construction. On the other hand, in spatial transcriptomics, these pigments or auto-fluorescent substances can interfere with microscopic imaging and morphological assessment of tissues, thereby compromising the accurate identification of cellular spatial locations.

Dynamic biology across perennial growth cycles

-

A vast number of important horticultural plants are perennial, with life cycles spanning several years or even decades. Their developmental processes—such as growth, dormancy, flowering, and fruiting—exhibit strong temporal and periodic characteristics. Most current single-cell studies capture only a single time-point snapshot, which is far from sufficient to reveal the complete biological processes. In fruit trees, for instance, key agronomic traits such as the transition from vegetative to reproductive growth (floral induction), bud dormancy and release, as well as fruit maturation and senescence, involve dynamic changes in cell types, states, and interactions. Designing multi-year, multi-time-point experiments and effectively integrating such dynamic data poses a major challenge. This requires not only technological breakthroughs but also innovations in experimental design and data analysis methodologies.

Extreme diversity and lack of genomic resources

-

The inherent complexity of horticultural plants poses certain challenges for data analysis. Horticultural plants have close relationships with humans and have undergone extensive domestication. Years of hybridization and selection have resulted in complex ploidy levels and genomes, and some other horticultural plants have very large genomes (for example, Lilium brownii and Paris japonica)[70,98], making it difficult to obtain high-quality reference genomes for some horticultural plants. However, with advancements in sequencing technologies, an increasing number of high-quality genomes of horticultural plants are now being published, which will help overcome this challenge over time.

All in all, single-cell and spatial transcriptomics provide high-resolution gene expression analysis tools for horticultural plant research, offering in-depth insights into cellular heterogeneity and spatial distribution characteristics. Despite the technical challenges in plant applications, such as the complexity of single-cell isolation and data analysis, their prospects in regeneration, development, disease resistance, and stress responses are vast. In the future, with advancements in technology and the enrichment of genomic resources for horticultural plants, single-cell and spatial transcriptomics are expected to play a crucial role in precision breeding and functional gene analysis of horticultural plants.

The research was supported by the Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (2025GXNSFAA069196), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32471935), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (QNTD202503), and the Yunnan Province Science and Technology Talent and Platform Program-Yunnan Province Zhang Qixiang Expert Workstation (202405AF140078).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: planned and designed the research: Liang X, Zheng T; wrote the draft manuscript: Liang X, Ma Z; contributed to the conception of the study: Li X, Li P; modified the language and format of the manuscript: Huang Y; revised the manuscript and finalized the manuscript: Zheng T, Zhang Q. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Summary of publications in plant research utilizing single-cell and spatial transcriptome techniques.

- Supplementary Table S2 Marker genes for identifying cell types in ornamental plants.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Liang X, Ma Z, Li X, Huang Y, Li P, et al. 2025. Application prospect of single-cell and spatial transcriptomics in horticultural plants. Ornamental Plant Research 5: e045 doi: 10.48130/opr-0025-0042

Application prospect of single-cell and spatial transcriptomics in horticultural plants

- Received: 11 September 2025

- Revised: 12 October 2025

- Accepted: 17 October 2025

- Published online: 01 December 2025

Abstract: Single-cell and spatial transcriptomics technologies hold great potential in horticultural plant research, enabling the analysis of cellular heterogeneity, spatial gene expression distribution, and cell-cell interactions. Although these technologies are relatively mature in animal studies, their application in plant research still faces numerous challenges, including difficulties in single-cell isolation, metabolite interference, perennial growth cycles, and a lack of genomic resources. This review summarizes the application of single-cell and spatial transcriptomics in plant research from 2017 to 2025, as well as their respective applications in horticultural plants, including regeneration, vegetative organ development, floral organ development, fruit development, disease resistance, abiotic stress responses, plant-microorganism interactions, and phylogenetic relationship analysis. Furthermore, the current limitations, as well as the future development of these two technologies are also discussed, with a view to informing applications on horticultural plants.