-

The control of the fruit ripening process is a fascinating topic that has attracted extensive research. Among the various regulators, the gaseous plant hormone ethylene plays a crucial role in the ripening of fruit. The ethylene biosynthesis pathway in seed plants was mainly elucidated in the 1970s and 80s. Ethylene biosynthesis starts from methionine, a sulfur-containing amino acid. Methionine reacts with adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to produce S-adenosyl-methionine (SAM) by SAM synthetase (SAMS). Then two committed steps are followed to synthesize ethylene. First, SAM is converted to 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) by ACC synthase (ACS). Second, ACC is oxidized to ethylene by ACC oxidase (ACO). During these steps, the C-3 and C-4 carbon atoms of methionine are converted into ethylene, and the C-1 and C-2 are metabolized into CO2 and HCN, respectively[1−3]. One may ask what happens to the fifth carbon and sulfur atom of methionine. Many ethylene biosynthesis scientists also paid attention to this intriguing question. Methionine levels in postharvest apple fruit were rather low while the fruit could emit a large amount of ethylene over months[4]. In addition, when apple tissue was administrated with L-methionine-35S, the 35S radioactivity was mainly recovered in methionine itself and SAM, but not emitted as a volatile[5]. Based on these observations, Baur & Yang proposed that the sulfur atom of methionine must be recycled in order to provide an adequate supply of methionine to sustain high rates of ethylene production in ripening apple fruit[4]. Later, Shang Fa Yang and his co-workers largely unraveled this recycling pathway in plants, hence this metabolic pathway carries his name as the Yang cycle (Fig. 1). The Yang cycle is also called the methionine salvage pathway, the methionine recycling cycle or the MTA cycle. It is noteworthy that the Yang cycle was proposed before the identification of the intermediate metabolites SAM and ACC in the ethylene biosynthesis pathway.

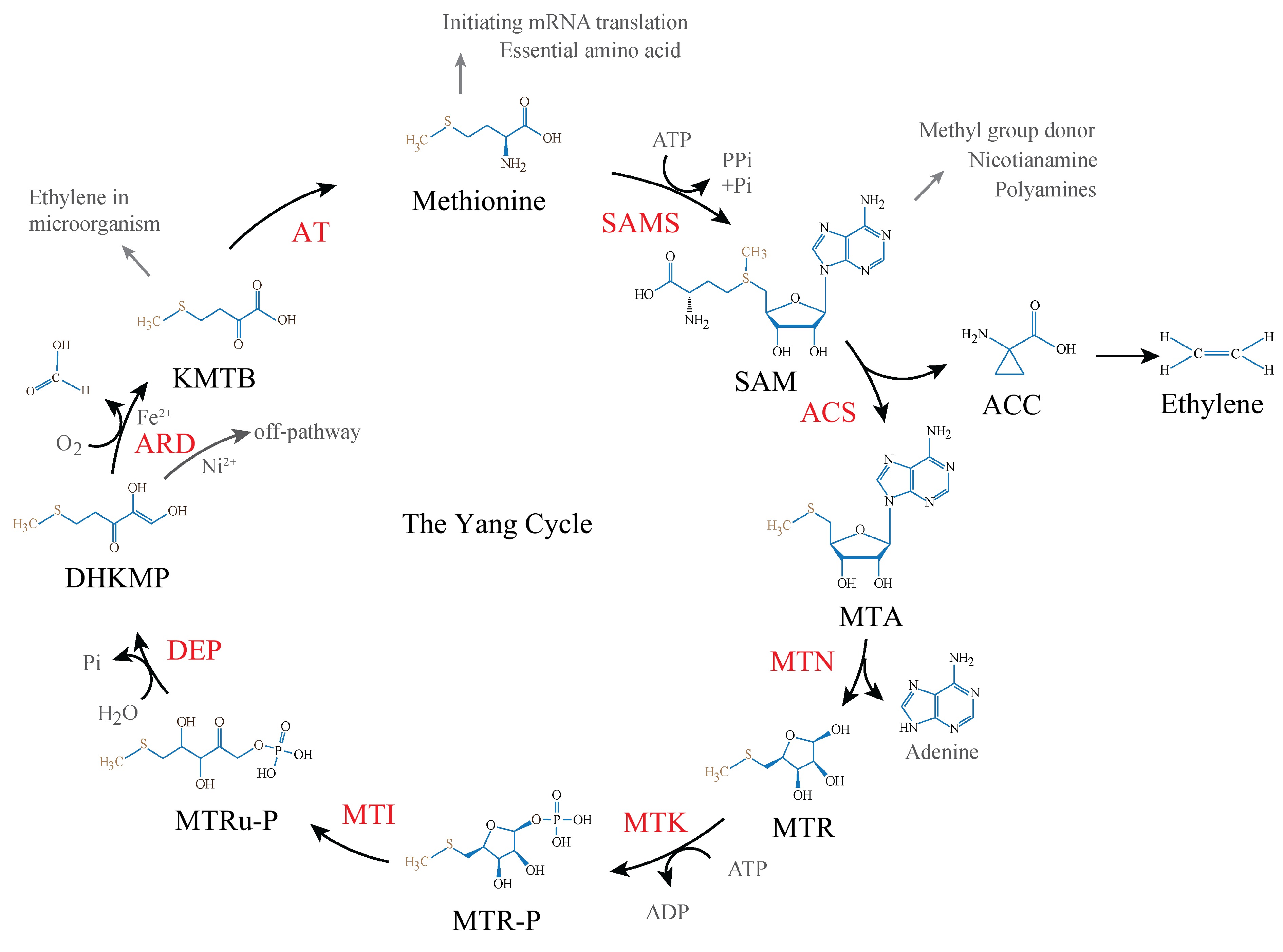

Figure 1.

The Yang cycle in plants. S-adenosyl-methionine (SAM) is first derived from methionine by SAM synthetase (SAMS), SAM then is converted to 5'-S-methyl-5'-thioadenosine (MTA) and 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) by ACC synthase (ACS). MTA is then depurinated to 5-methylthioribose (MTR) by MTA nucleosidase (MTN). MTR is subsequently phosphorylated to 5-methylthioribose-1-phosphate (MTR-P), catalyzed by MTR kinase (MTK) in the presence of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). MTR-P gets isomerization to yield 5-methylthioribulose-1-phosphate (MTRu-P) by MTR-P isomerase (MTI). MTRu-P then is metabolized to 1,2-dihidroxy-3-keto-5-methylthiopentene (DHKMP) by dehydratase-enolase-phosphatase (DEP). DHKMP is converted to 2-keto-4-methylthiobutyrate (KMTB) by acireductone dioxygenase (ARD) in the penultimate step. At last, KMTB turns to methionine by an unknown aminotransferase (AT).

In plants, the methylthio moiety of SAM in the Yang cycle is first reconstituted as one unit into 5'-S-methyl-5'-thioadenosine (MTA) as a product of the ACS reaction. MTA is then depurinated (loses an adenine) to 5-methylthioribose (MTR) by MTA nucleosidase (MTN)[6]. The C-1 hydroxyl group of the ribose moiety of MTR is subsequently phosphorylated to 5-methylthioribose-1-phosphate (MTR-P), a step catalyzed by MTR kinase (MTK) in the presence of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). MTR-P is isomerized to 5-methylthioribulose-1-phosphate (MTRu-P) by MTR-P isomerase (MTI), an enzyme that opens the ribose moiety of MTR-P. MTRu-P then undergoes a series of reactions to 1,2-dihidroxy-3-keto-5-methylthiopentene (DHKMP) by one single enzyme, dehydratase-enolase-phosphatase (DEP). DHKMP is converted to 2-keto-4-methylthiobutyrate (KMTB) by acireductone dioxygenase (ARD) in the penultimate step. Finally, a transamination of KMTB reproduces a new molecule of methionine by an unknown aminotransferase (AT), in which the corresponding amino donor has also not been identified yet (Fig. 1). In summary, the Yang cycle can be described using the following formula:

$\begin{split} &\mathrm{M}\mathrm{T}\mathrm{A}\;+\;\mathrm{A}\mathrm{T}\mathrm{P}\;+\;{\mathrm{O}}_{2}\;+\;\mathrm{R}\;-\;\mathrm{N}{\mathrm{H}}_{2}\;\to\; \mathrm{M}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{h}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{e}\;+\;\mathrm{A}\mathrm{D}\mathrm{P}\;+\\&\quad\mathrm{P}\mathrm{i}\;+\;\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{e}\;+\;\mathrm{H}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{H}\;+\;\mathrm{R}\;=\;\mathrm{O} \end{split}$ Of the newly generated methionine molecule, the methythio group is recycled and the other four carbon atoms originate from the ribose moiety of an ATP. Therefore, ATP availability has been claimed to correlate with the ethylene production rate[7].

The Yang cycle was initially identified in microorganisms and plants[8]. Its significance has also expanded to animal and human metabolism, where methionine metabolism imbalance can impact tumor growth and neurodegeneration[8]. Although the main function is sulfur recycling, the Yang cycle pathway in plants poses variations in the biochemical steps from that in microorganisms, animals, and humans. For example, in mammalian tissue and yeast, MTA is directly converted to MTR-1-P by MTA phosphorylase (MTAP) without the requirement of MTN and MTK and without MTR production[9,10]. In some microorganisms, DEP is in fact a three-step reaction composed of three individual enzymes[8]. However, the evolution of specific Yang cycle genes in plants and the biological functions of intermediate metabolites have not been well understood.

Metabolites and enzymes involved in the Yang cycle have been progressively identified in the 40 years after its first proposal. Over the last decade, studies have tilted their focus more toward the regulation of genes and enzymes in the cycle and the versatile physiological functions in plants. In this review, we summarize the current understanding of the individual metabolites and enzymes in the Yang cycle in plants. We also discuss the role of the Yang cycle in regulating ethylene biosynthesis.

-

Methionine is one of the few sulfur-containing essential amino acids in plants. It plays fundamental roles in protein synthesis and mRNA translation initiation in cell biology, and it also serves as the precursor of SAM which is used in many physiological processes. In contrast to its significance, the free methionine content is extremely low compared with other amino acids in Arabidopsis leaves[11], indicating that plants have a precise mechanism in modulating methionine content[12].

Methionine can be de novo synthesized starting from O-phosphohomoserine (OPH) in three consecutive steps, in which the first specific enzyme, cystathionine γ-synthase (CGS) competes with threonine synthase (TS) for the common substrate OPH (Fig. 2)[11]. CGS is covalently linked to a cofactor pyridoxal phosphate in Mycobacterium ulcerans[13]. Subsequently, cystathionine β-lyase (CBL) catalyzes the β-cleavage of cystathionine to homocysteine. Finally, methionine synthase (MS) converts homocysteine to methionine[14]. The first two steps are localized in the chloroplast, but the final step of methionine biosynthesis takes place in the cytosol[14,15]. An Arabidopsis TS mutant, mto1, accumulates up to 40-fold more soluble methionine in the rosette than the wild type while threonine content decreases by only 12%[16]. The SAM level is 3-fold more than in the wild type but ethylene production only increases 40%[16]. Another TS-impaired mutant, mto2-1, which carries a single base pair mutation resulting in leucine-204 to arginine change, accumulates over 20-fold soluble methionine and 3-fold more SAM in young rosettes than the wild type. However, threonine was greatly reduced to 6%[17]. Direct regulation of the expression of CGS could also promote methionine biosynthesis. For example, overexpressing either the full-length or an N-terminus truncated Arabidopsis CGS leads to substantial increases in methionine content in transgenic tobacco plants[18]. Intriguingly, a comparable increase in methionine contents in two types of transgenic plants rendered distinct rates of ethylene production. In the truncated CGS overexpressing plants, the ethylene level is 40 times greater than that in the wild-type plants. In contrast, there is no difference in ethylene production between the full-length CGS overexpressing plants and the wild type[18]. This indicates that an accumulation of methionine does not align with an increase in the ethylene production rate. The CGS N-terminus may have a regulatory role in the ethylene biosynthesis pathway, or certain feed-back steps trigger stress-induced ethylene synthesis. The remarkable abundance of the sulfide-containing compounds dimethyl sulfide and carbon disulfide in the truncated CGS plants also raises another possibility that the CGS N-terminus may impact methionine metabolism and eventually suppress ethylene biosynthesis.

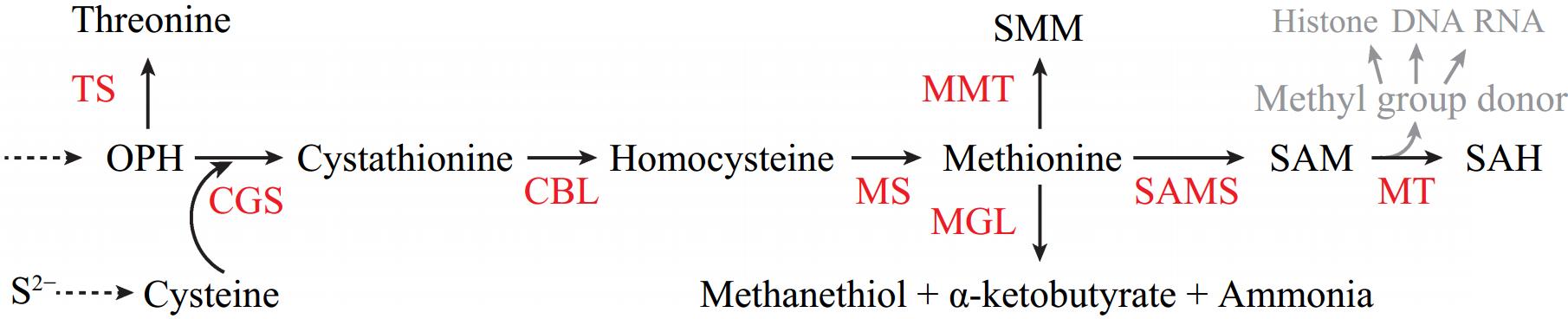

Figure 2.

The metabolism and homeostasis of methionine and S-adenosyl-methionine (SAM) in plants. Methionine can be de novo synthesized from O-phosphohomoserine (OPH), in which cystathionine γ-synthase (CGS) competes with threonine synthase (TS) for OPH. CGS metabolizes OPH and cysteine to cystathionine which is then converted to homocysteine by cystathionine β-lyase (CBL). Methionine is produced from homocysteine by methionine synthase (MS). Methionine can be metabolized to methanethiol, α-ketobutyrate and ammonia by methionine γ-lyase (MGL). It also can be converted to S-methylmethionine (SMM) by methionine S-methyltransferase (MMT). The conversion of SAM to S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) by diverse methyltransferases (MTs) provides methyl moiety for acceptors including histone, DNA, and RNA.

Though a significant amount of methionine fluxes to SAM by SAMS[19], many enzymes including methionine γ-lyase (MGL) and methionine S-methyltransferase (MMT) are involved in methionine metabolism (Fig. 2). MGL catalyzes methionine to methanethiol, α-ketobutyrate, and ammonia[20]. In Arabidopsis, knocking out MGL results in a significant increase in methionine levels in leaf[21]. MGL also functions in seed development and germination under heat stress[22]. Methionine can be metabolized to S-methylmethionine (SMM) by SAM-dependent MMT (Fig. 2)[23]. SMM is a storage reservoir of methyl donor in the phloem, and functions in controlling SAM and methylation levels[23,24]. Both Arabidopsis and maize mmt mutants produce 1%−2% of wild-type SMM contents. Despite the reduction of SMM content, the morphology and fertility in both Arabidopsis and maize are indistinguishable from wild-type plants[25]. However, when growing Arabidopsis mmt mutant under saline conditions, the plant growth, and germination rates are severely repressed[26]. In soybean, a transposon-insertion in the MGL gene results in a mutant with SMM hyperaccumulation in the seed. The SMM storage was postulated to avoid excess methionine build-up[27].

During tomato fruit ripening, a large amount of ethylene is emitted while the free methionine content continuously increases, suggesting methionine is not limiting for ethylene synthesis[28]. Interestingly, tomato CGS expression and protein level peak at the color-turning stage during ripening. CGS mRNA level in the pericarp is stimulated by wounding, resulting in higher ethylene production[29], corroborating an active synthesis of methionine during tomato fruit ripening. In addition, tomato CGS expression was responsive to ethylene[29]. The relationship between the availability of soluble methionine and ethylene production may be further evaluated by generating methionine overaccumulation in fruit by disrupting TS or enhancing CGS activity. Methionine to SAM metabolism is around 80% of the sulfur flux in the Lemna plant[30]. Similarly, some interesting questions remain in the fruit ripening process: (1) What are the ratios of the methionine recycling by the Yang cycle, methionine metabolism and de novo biosynthesis? (2) How are the methionine fluxes mediated? (3) What is the influence of methionine metabolism on ethylene production rate?

SAM: a universal metabolite with versatile functions

-

SAM is a precursor for many metabolites, such as ethylene, polyamines (PAs), nicotianamine (NA), and phytosiderophores. SAM also serves as a universal methyl donor for O-methyltransferases for lignin and flavonoids, for N-methyltransferases of DNA and histone methylation, for C-methyltransferases of lipids, thiol, and halide ion methyltransferases for organic thiols[31]. For the biological destination of all SAM constituents and the SAM-dependent enzymes, we refer to two comprehensive reviews[32,33]. Here we will focus on the regulation of SAM levels and its link with fruit ethylene synthesis.

SAM was identified as an effector of the posttranscriptional regulation of CGS. Exogenous SAM application reduces the expression and stability of CGS in Arabidopsis, while various SAM metabolites including SMM, MTA, and ACC had no regulatory effect on CGS expression. Exon1 of CGS has been identified to carry the regulatory site for this SAM effector, because mto1-1, harboring a single base change within the first exon of CGS, lacks the SAM-feedback on CGS expression[34]. The transport of SAM in sub-cellular compartments is also critical for plant growth. A recent study identified two putative Golgi-localized SAM transporters. The disruption of both genes alters cell wall molecular architecture and polysaccharide mobility, and the double mutant displays stunted plant morphology with significantly shorter inflorescence stems and reduced flower size[35].

SAM level is also adjusted by its conversion to S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) by methyltransferases (MTs), providing a methyl moiety for acceptors such as histone, DNA, and RNA (Fig. 2)[36]. The SAM/SAH ratio is considered an indicator of methylation potential in plants, altering with changing environments such as sulfur deficiency and developing stimuli[36]. In fruit ripening, histone, DNA, and RNA methylations have been identified as important epigenetic modifications[37,38]. Meanwhile, the synthesis and distribution of SAM have been shown to impact MT activity[39]. It is unclear whether the SAM level and its impact on the activity of epigenetic enzymes have a regulatory effect on fruit ripening. Indeed, SAM content shows a decrease during tomato fruit ripening while SAH increases substantially, leading to a continuous decline in the SAM/SAH ratio[28,40]. It is also yet to be explored whether ACC biosynthesis from SAM functions as a pathway in modulating the SAM pool in fruit. The ethylene precursor ACC has been proposed as an emerging signaling molecule functioning in a vast array of physiological processes in both seed and non-seed plants[41]. We wonder whether exogenous ACC treatment or disrupting ACS genes may introduce a feedback effect on SAM level that can influence plant functioning, independent of the ACC/ethylene action. This is in contrast to ethylene signaling mutants which still have an intact ethylene biosynthesis pathway and a possibly higher capacity in mediating SAM homeostasis.

MTA: a molecule that mediates cell growth

-

MTA is a common by-product produced during the biosynthesis of PAs, NA, and ethylene in plants. In Arabidopsis, MTA content is not altered in mtn single mutants[42]. However, MTA content is respectively 2-fold and 10-fold higher in the rosette leaves and inflorescences of mtn double mutants[32,43]. The overaccumulation of MTA in mtn mutants causes pleiotropic phenotypes including interveinal chlorosis in young seedlings, thicker mild veins, increased vascular bundles in the stem, abnormal pollen grains and ovules[43]. The authors confirmed that these phenotypes were caused by MTA accumulation since complementation with MTN restored the phenotypes. In addition, by expressing the human MTAP gene in the mutants, they also ruled out that those phenotypes were due to a reduction of MTR, the following product of MTA in the Yang cycle[43].

It has been an interesting question why MTA metabolism causes pleiotropic phenotypes in plants. MTA metabolism alters PA and NA contents, but these changes are predominantly observed after MTA-treatment conditions and are not substantial during normal growth[42,43]. Nevertheless, exogenous PAs or NA treatment could partially rescue phenotypes of interveinal chlorosis and fertility in mtn double mutants. In mammals, MTA itself functions as a molecule mediating cell growth[44]. A loss of MTAP activity leads to cancer, and overaccumulation of MTA has been associated with tumor progression[45]. Based on crystal structures, it is predicted that two PA synthesizing enzymes, spermidine and spermine synthases, contain residues for interacting with MTA which potentially inhibit their enzyme activities[43]. The molecular basis of MTA metabolism in plant growth was further dissected by carrying out a genetic suppressor screening of mtn1-1 mutant grown with MTA as the sole sulfur source[46]. A MTA RESISTANT 11 (mtar11) mutant exhibits increased plant growth and fertility, in which the causal mutation was located in a bZIP29 transcription factor. In addition, some defects in mtn1-1 could also be explained by the action of TARGET OF RAPAMYCIN (TOR) which is a central regulator for cell growth and metabolism[46,47]. The activity of TOR is largely reduced in the mtn double mutant. Surprisingly, the root growth of the wild type is inhibited by a TOR inhibitor, whereas the root growth of the mtn double mutant remains relatively unaffected[46].

In fruit, MTA content is tightly regulated during maturation and postharvest senescence[28]. It has been shown that the ethylene production in ripening tomato fruit could be suppressed by various exogenous MTA analogs[48], indicating a close link between MTA and ethylene production. During tomato fruit ripening, MTA content decreases sharply in developing tomato, and increases back to the initial level around the orange stage, then declines slowly as fruit ripens further and senesces. This MTA profile is similar to the changes in ethylene production levels and ACS activity. In addition, MTA contents do not differ significantly between fruit that ripened on or off the vein[28]. It remains to be studied whether a change in ACS activity in tomato fruit can impact MTA levels, and other pathways MTA is associated with. For example, it was proposed that MTA biosynthesis from PA and ethylene might jointly regulate MTA abundance in ripening fruit[28].

KMTB and other metabolites: much to be understood

-

KMTB, the last intermediate of the Yang cycle, is a direct precursor of methionine, with a keto group to be transaminated. In the pharmaceutical industry, KMTB is of particular interest since it improves the bioactivity of methionine in tumor growth[49]. KMTB deficiency is associated with tumor development, thus, it is a potent indicator for diagnosis and therapeutic treatment[49]. In microorganisms, such as Escherichia coli[50], Cryptococcus albidus[51], and Botrytis cinerea[52,53], KMTB is an ethylene biosynthetic precursor. In these cases, KMTB is directly produced from methionine by methionine AT rather than biosynthesized from the Yang cycle[50]. KMTB has also been suggested to play a role in tomato fruit-microbe interactions[53].

It has been shown that KMTB can be aerobically converted to ethylene in in vitro reactions[54]. In planta, KMTB was first identified as an intermediate metabolite in the Yang cycle in tomato and avocado fruit[55]. However, similar to other methionine analogs including S-methylmethionine and homoserine, KMTB is much less efficient than methionine in ethylene synthesis. Therefore, KMTB is considered to influence ethylene production in fruit via its first conversion into methionine[56]. Interestingly, a KMTB analog, 2-hydoxy-4-methylthiobutyrate (HMTB), is formed as a by-product when administrating fruit cell extracts with MTR. Distinctly from KMTB, HMTB treatment cannot induce ethylene production. Instead, it inhibited the conversion of KMTB to methionine[55]. It remains unsolved how HMTB is produced and what its function is in the Yang cycle.

Another two intermediate metabolites in the Yang cycle in plants, MTR and MTR-P, were first identified in tomato fruit by feeding with radioactive precursors[55,57]. For the rest of the intermediates, most of our knowledge comes from non-plant systems (yeast, bacteria, and animal cells). The abundances of MTR-P, MTRu-P, DHKMP, and KMTB in developing plants, as well as their responses to various stimuli or stresses, await further investigation. Analytical methods such as precipitation with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine, mass spectrometry or high-performance liquid chromatography have been used to detect KMTB content in microorganisms[52,58,59]. The application of these methods in plants can be explored to understand, for example, what the pattern of KMTB abundance is in ripening tomato fruit.

-

SAMS is one of the well-studied enzymes of the Yang cycle. In the Arabidopsis genome, there are four SAMS genes (Fig. 3). As expected, regulation of the expression or activity of SAMS could efficiently alter methionine content in plants. For example, an Arabidopsis mto3-1 mutant which contains an amino acid change in the ATP binding domain of SAMS3 leads to more than 200-fold higher methionine content compared with the wild type[60]. Similarly, in the mto3-2 mutant, a different amino acid change in SAMS3 results in an overaccumulation of methionine[61]. In contrast, SAMS overexpressing transgenic Arabidopsis plants are morphologically indistinguishable from wild-type plants and have little changes in methionine content[62]. A different case was observed in tobacco, in which both overexpression and suppression of SAMS activity lead to abnormal phenotypes. The suppressed SAMS activity also renders a characteristic volatile smell of methanethiol as a consequence of methionine accumulation[63].

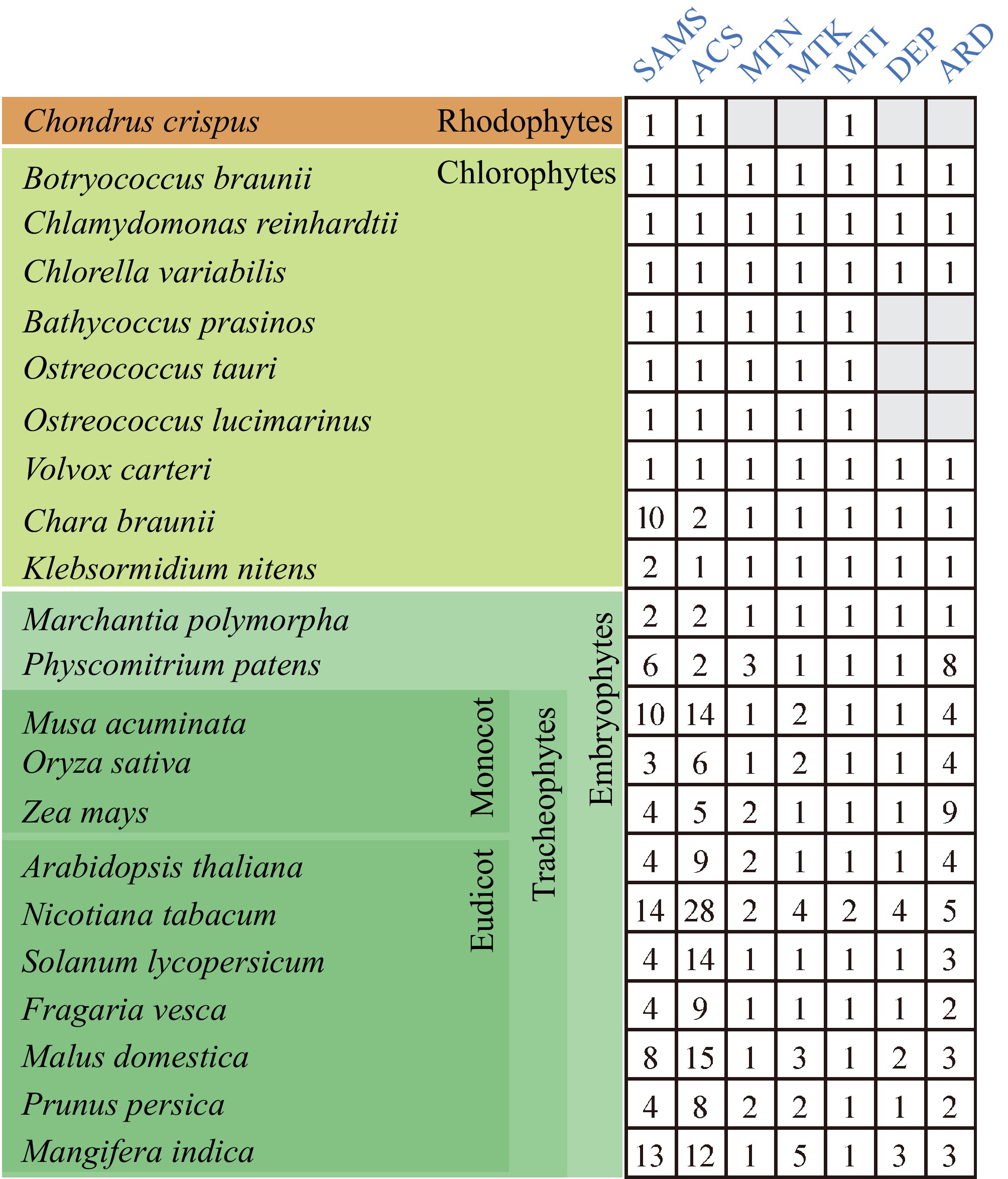

Figure 3.

The enzyme proteins of the Yang cycle in several major plant lineages. The Yang cycle proteins in each species were identified using BLAST with an E-value threshold of 1e−5, employing the default settings of TBtools-II. Searches were conducted with the amino acid sequences of each enzyme from Arabidopsis thaliana as references. The numbers indicate enzyme paralogs. Gray boxes indicate an absence of enzyme paralog.

A vast array of studies has shown that SAMS are important for many developmental and growth processes in plants. For example, RNA interference of OsSAMS1, 2, and 3 causes pleiotropic phenotypes including dwarfism and delayed flowering in rice[64]. Overexpressing SAMS in Arabidopsis also leads to abnormal floral organ development[65]. In Arabidopsis pollen tubes, SAMS3 is highly expressed and a disruption of SAMS3 impairs pollen tube growth and seed set[66]. OsSAMS1 also functioned as a regulator for grain size and yield in rice[67]. Plant SAMS is localized in the cytoplasm and nucleus[64,66]. The molecular mechanism of the functions of SAMS in plants is mainly associated with SAM-dependent DNA and/or histone methylation, ethylene signaling, and PA metabolism[64−66]. By using overexpression trangenic plants or knockout mutants, SAMS genes have been shown to play important functions in various abiotic stress responses in plants. For example, SAMS confer tolerance to stresses including cold, drought, and salt stress[68−71].

The functions of SAMS are tightly regulated at multiple levels in plants. For example, OsSAMS1, 2, and 3 interact with a cell wall-associated kinase (OsWAK112), resulting in their degradation. The overexpression of OsWAK112 significantly decreases plant survival under salt stress, mainly caused by reduced ethylene production[72]. In pumpkin fruit, a long non-coding RNA was found to interact with SAMS and promote its stability, thus promoting fruit development via ethylene biosynthesis[73]. SAMS can also be post-translationally regulated, in which protein phosphorylation is the most abundant modification. Arabidopsis CDPK28 and cucumber CsCDPK6 interact with and phosphorylate their corresponding SAMS proteins[74,75]. SAMS phosphorylation leads to its protein degradation via the 26S proteasome pathway, therefore regulating ethylene biosynthesis[74]. Another putative protein kinase-like protein, OsLCD3, can interact with OsSAMS1 as well. Genetically, OsSAMS1 and OsLCD3 share a common regulatory pathway in regulating rice grain size through controlling ethylene/PA homeostasis[76]. OsSAMS1 is also targeted by the F-box protein OsFBK12 for degradation and is involved in multiple processes including leaf senescence, seed germination, and grain size[77].

The tomato genome contains four SAMS genes evenly divided into two subgroups[78]. The expression of SAMS genes shows various patterns in response to stress or hormone treatments, suggesting that tomato SAMS genes are transcriptionally regulated[78]. During tomato fruit development, all SAMS genes also show different expression profiles, but none of the SAMS expression profiles are correlated with the climacteric ethylene production pattern[28]. The function of SlSAMS1 in tomato fruit ripening was uncovered recently by applying virus-induced gene silencing. The transient silencing of SlSAMS1 leads to incomplete coloration during fruit ripening. In addition, the function of SlSAMS1 was claimed to be regulated during fruit ripening via interaction with a plasma membrane protein, FERONIA-like[79].

ACS: for ACC synthesis and/or for SAM metabolism?

-

ACS catalyzes SAM into ACC and MTA, and it is generally considered as the rate-limiting enzyme in ethylene biosynthesis. ACS belongs to a multigene family in most plants, and its transcription and activity are intricately modulated[80].

Distinct from many other Yang cycle genes, the expression patterns of ACS genes in Arabidopsis are not vascular-specific[6,81]. It remains obscure what the relationship is between the functional locations of ACS and other Yang cycle enzymes. Intracellularly, ACS is predominantly localized within the cytosolic compartment. Its enzymatic activity is contingent upon the presence of pyridoxal-5′-phosphate (PLP) as a cofactor[82]. Within the ACS enzyme, Arg412 plays a crucial role in positioning the substrate SAM adjacent to the PLP-lysine internal aldimine. Tyr152 executes a nucleophilic attack on the C-γ of SAM, which results in the cleavage of the C-γ–S bond. A covalent intermediate, likely formed through a transmethylation-like mechanism between Tyr152 and C-γ, is then transformed into ACC aldimine. Finally, the deprotonated Lys278 attacks the C4′ of PLP, leading to the release of ACC[83]. ACC is an emerging signaling molecule in plants[43], therefore, together with MTA, ACS functions as a key enzyme to simultaneously produce two important signaling molecules. Interestingly, another study revealed that ACS has an additional Cβ-S lyase activity in seed plants. With this activity, L-cystine can be metabolized into thiocysteine, pyruvate, and ammonia[84]. The ratio between the canonical and Cβ-S lyase activity of ACS in plants remains unsolved. It was postulated that canonical ACC-producing ACS activity could be the main function while Cβ-S lyase activity is residual in seed plants[84]. Whether the Cβ-S lyase activity of ACS has a biological function in ripening fruit awaits to be studied. This function could be towards L-cystine metabolism or mediating ACC/MTA production. In addition, it is reported that ACS in non-seed plants only has the Cβ-S lyase activity while the ACC-producing activity evolves later in seed plants[84]. It remains intriguing to investigate the function of the Yang cycle in methythio group recycling and ACC/ethylene homeostasis non-seed plants.

MTN: the starting enzyme in recycling the methythio moiety

-

MTN activity was first observed in crude apple fruit extracts in plants[85], and the enzyme was purified from Lupinus luteus seeds, showing a broad substrate specificity[86]. The Arabidopsis genome has two MTN-encoding genes, MTN1 and MTN2, showing distinct expression abundances and patterns. MTN1 is mainly expressed in roots, stems, flowers, and rosette leaves, and the expression of MTN1 is preferential in vascular tissues[6]. MTN2 transcripts are 10-fold less abundant in these tissues. MTN2 is predominantly expressed in the apical-basal cells of embryos and in developing reproductive organs and leaf guard cells[87]. In addition, biochemical characterization shows that MTN1 only metabolizes MTA, while MTN2 has substrate promiscuity. The crystal structures of MTN1 and MTN2 aided in revealing the differences in substrate specificity. The active loop for substrates is more rigid in MTN1 than MTN2[88,89].

The physiological functions of MTN1 and MTN2 have been evaluated using T-DNA insertion mutants in Arabidopsis. Both single mtn1 and mtn2 mutants do not exhibit any obvious phenotype under normal growth conditions, but the growth of mtn1 seedlings is significantly inhibited when MTA is supplied as the sole sulfur source. Blocking MTA metabolism in mtn1 seedlings results in an accumulation of SAM and PAs when grown on MTA-containing medium. Further analysis of mtn1 and mtn2 single mutants revealed that more than 80% of the total MTN activity originates from MTN1[42]. A double mutant completely lacking MTN activity is not viable due to embryo lethality, therefore, a leaky double knock-down mutant was generated by crossing mtn2-1 with mtn1-1 which is viable and shows 7% to 8% residual MTN activity. Under normal growth conditions, the double mtn1-1mtn2-1 mutant displays pleiotropic phenotypes, including delayed flowering, underdeveloped siliques, interveinal chlorosis in true leaves, thicker mid veins, aberrant pollen and ovule, and sterility[42,43]. The molecular basis of the significance of MTN in plant growth and development could be due to MTA metabolism since MTA over-accumulates in the mtn1-1mtn2-1 mutant, which in turn can influence auxin transport and PA biosynthesis[43]. Although MTA is closely linked to ethylene and NA biosynthesis, their levels are not altered in MTN single mutants[42]. It is still unclear whether ethylene and NA biosynthesis would be impaired in the mtn double mutant and contribute to the physiological basis for these pleiotropic traits.

MTN also plays important roles in the growth of crop plants. In rice, MTN is encoded by only one gene (Fig. 3). The in vitro activity of OsMTN recombinant enzyme was characterized, and also rice MTN shows a broad substrate affinity for a wide array of thioadenosine substrates[90]. In maize, an amino acid mutation (glycine changes to asparticacid) in ZmMTN1 or disrupting its activity triggers Fe-deficiency responses, leading to interveinal chlorosis in leaves[91], similar to Arabidopsis mtn mutants[42,43]. The MTA levels in roots and leaves of maize mtn1 mutants are higher, while NA contents are substantially reduced[91]. Moreover, the interveinal chlorosis defect can be restored by exogenous NA treatment or overexpressing an NA biosynthesis gene[91]. These results reveal a significant role of MTN in mediating NA and Fe homeostasis in maize.

The physiological function of MTN in fruit has not yet been well understood. In the tomato genome, only one gene encodes MTN (Fig. 3). Based on the changes in MTR content, MTN activity exhibits a continuous decline during tomato fruit ripening[48]. In another study, MTN activity sharply decreases in developing fruit and increases again from the start of ripening until the postharvest stages[28]. In contrast, the transcript of SlMTN increases in the fruit developing stage, declines in the ripening phase, and peaks in the postharvest period. As such, the MTN activity profile does not exhibit a high correlation with its transcription, nor MTA, ACC, or ethylene levels. It would be interesting to study the function of MTN using a genetic approach and investigate its physiological role during tomato plant development and fruit ripening.

MTK: the first Yang cycle gene cloned in plants

-

It has long been established that an ATP-dependent kinase, named MTK, is responsible for the conversion of MTR to MTR-P in fruit extracts[92]. MTK has been partially purified from yellow lupin (Lupinus luteus) seeds, and reaches its maximal activity around pH 10.0 with Mg2+ and Mn2+ as metal cofactors[93]. Despite these early findings on the establishment of MTK’s role in the Yang cycle, the gene encoding MTK in plants was only cloned more than 20 years later. Two rice MTK genes (OsMTK1 and OsMTK2) and one Arabidopsis MTK gene were the first MTK genes cloned in the Yang cycle in plants[94]. In most plant species, MTK is encoded by a single-copy gene (Fig. 3). The highly conserved sequences and gene structure of the two rice MTK genes suggest gene duplication may have happened recently in monocots[94]. By driving a β-glucuronidase reporter gene under the control of MTK promoter, the expression of MTK is observed to be predominant in vascular tissues, more specifically the phloem[6]. The T-DNA knock-out mutant of MTK is phenotypically comparable to the wild-type plants under normal growth. However, the growth arrest caused by sulfur-depletion could be partially rescued by MTA in the wild type but not in the mtk mutant[94]. In rice, OsMTK expression is induced under sulfur deficiency while unaffected under Fe or nitrogen shortage[94]. These results suggest that MTK may predominantly function in MTA metabolism under sulfur-limited conditions.

Besides regulating growth under sulfur-deficient conditions, the link between MTK and ethylene biosynthesis has also been assessed. For example, ethylene production of deepwater rice is known to be triggered by submergence. Unexpectedly, OsMTK expression shows a poor spatial or temporal correlation with the ethylene rate during the flooding of rice plants[94]. To evaluate the role of MTK in methionine recycling under a high-rate ethylene production physiology, a mtk mutant was crossed with an ethylene overproducing mutant, eto3 (which harbors an amino acid change in ACS9 resulting in ACS9 protein stability and ethylene over-production). The double eto3mtk mutant retains a high rate of ethylene biosynthesis while the methionine salvage pathway is impaired[95]. It shows that the ethylene production of eto3mtk seedlings is at an intermediate level between mtk and eto3, indicating that MTK is in part required to sustain high rates of ethylene synthesis[95]. Surprisingly, no additional growth defects in adult eto3mtk plants are observed in comparison with the eto3 mutant. Moreover, the contents of methionine, SAM, MTA, and two other sulfur-containing amino acids (cysteine and glutathione) are also not significantly different among wild type, mtk, eto3mtk, and eto3 mutants both under normal growth conditions and in sulfur-deficient medium[95].

Climacteric fruit produce high amounts of ethylene during ripening and in response to wounding. Therefore, it is an interesting model to study the function of MTK in regulating ethylene biosynthesis. The expression of tomato SlMTK generally remains constant during fruit development and ripening, but increases in the overripe stages[28]. In contrast, MTK activity significantly increases during tomato fruit ripening, and its activity peaks around the color breaker stage, correlating to the peak in ethylene production[48]. The discrepancy between SlMTK expression and its activity during tomato fruit ripening may be caused by posttranscriptional regulation. Moreover, 5-isobutylthioribose, an MTR analog, is effective in suppressing MTK activity and ethylene production in ripening tomato fruit[48,96]. MTK activity is also induced in the first few hours after wounding in mature-green tomato fruit and cucumber[96], a process also linked to wound-ethylene production. Overall, MTK seems important to enable ethylene production in fruit tissue. To further reveal the role that MTK plays in fruit ripening or other physiological processes, a reverse genetic approach to study the single SlMTK tomato gene is likely rewarding.

MTI and DEP: delicate enzymes in plants

-

By using yeast and bacteria sequences, a gene named MTI encoding the enzyme catalyzing MTR-P to MTRu-P was identified in the Arabidopsis genome. The biochemical function of MTI was then confirmed by complementing in an MTI homolog-deleted yeast mutant[6]. In bacteria and yeast, the conversion of MTRu-P to DHKMP is catalyzed by several enzymes, possessing individual or combined functions of dehydratase, enolase, and/or phosphatase[97,98]. BLAST analyses revealed that DEP is a fusion protein with an N-terminal sharing similarity with dehydratases and a C-terminal resembling an enolase-phosphatase, similar to fusion proteins encountered in animals, bacteria, and fungi. The trifunctional enzyme activity of DEP is confirmed in yeast mutants[6]. As per MTN and MTK, both Arabidopsis MTI and DEP are preferentially expressed in the phloem[6]. In addition, their expression is ubiquitous in the vasculature of reproductive organs, roots, siliques, seeds, and rosette leaves[99]. In Arabidopsis, the functions of MTI and DEP are linked to the sulfur metabolism during flowering and seed development. These two genes also show significant roles in adjusting PA and NA metabolism in the vascular tissues[99].

Two DEP-encoding genes are present in the apple genome (Fig. 3). Ectopic overexpression of MdDEP1 in Arabidopsis enhances salt and drought tolerance, and promotes flowering[100]. Overexpressing MdDEP1 in apple plants enhances ethylene production and leaf senescence, and the expression of MdDEP1 is regulated by the MdBHLH3 transcription factor[101]. MdDEP1 was further found to interact with, dephosphorylate and destabilize the thylakoid protein MdY3IP1, involved in mediating photosynthesis and leaf senescence[102]. These results expand our understanding of the physiological functions and molecular regulation of DEP1 in horticultural crops.

ARD: a moonlighting protein with metal-driven activities

-

ARD is a metalloenzyme whose activity is determined by divalent metal ion co-factors. The Fe2+-ARD isozyme catalyzes the Yang cycle on-pathway reaction using DHKMP to produce KMTB and formate, whereas, Ni2+/Co2+/Mn2+-ARD converts DHKMP in an off-pathway to methylthiopropionic acid, carbon monoxide, and formate[103]. This particular characteristic of ARD has been observed in a wide array of organisms, such as Escherichia coli[103], Klebsiella oxytoca[104], mice[105], humans[106], and rice[107]. The dissociation rates of the metals from ARD are low[103], making the coordination of different metal binding states of ARD an intriguing question.

The affinity for Ni2+ is higher than for Fe2+ in E. coli. The relative amount between the two metalloenzymes is approximately 1:3 (Ni2+ : Fe2+), while this ratio could be elevated by adding additional Ni2+[103]. The eventual ARD enzyme activity seems dependent on the availability of these co-factor metals. When rice OsARD1 is expressed in bacteria, it shows a preference for Fe2+ rather than Ni2+, suggesting a more primary function in the methionine salvage pathway[107]. Which mechanism determines these two distinct biochemical reactions remains puzzling. It has been indicated that these two reactions do not occur sequentially[103]. The different addition sites of a hydroperoxide radical or anion to KMTB could be caused by the conformational differences of two metalloenzymes[103]. More insights into the structural mechanisms of ARD are described in a review[108]. The off-pathway metabolites, particularly methylthiopropionic acid, and carbon monoxide, are also of physiological importance in plants[103,107]. The in planta occurrence of the off-pathway reaction and its impact on the Yang cycle needs to be further clarified.

The expression of ARD gene changes in response to environmental stimuli and hormones in plants. For example, rice OsARD1 mRNA levels show a rapid increase upon submergence and after treatment with ethylene-producing compounds[107]. In potato, StARD expression was remarkably induced after wounding[109]. By transgenic overexpression, OsARD1 promotes stress tolerance through enhancing ethylene biosynthesis[110]. The link between ARD and ethylene is less clear in Arabidopsis, because etiolated ard1 seedlings exhibit a shorter hypocotyl length, yet they have a lower ethylene production[111]. This suggests that ethylene is not directly involved in hypocotyl elongation in the dark-grown ard1 mutant, but that ARD1 can have another direct or indirect action on cell elongation[111]. The absence of an exaggerated apical hook and a short root in ard1 dark-grown seedlings corroborates the broken link between ARD and ethylene in Arabidopsis[111].

Mammalian ARD enzymes are known as moonlighting proteins, executing additional functions that are unrelated to their enzymatic activity[112]. Surprisingly, ARD1 was first reported to be an effector for the Gβ (AGB1) subunit in the heterotrimeric G protein complexes in plants[111]. This finding was established when screening for dominant suppressor mutants of the agb1-2 null phenotype. ARD1 activity is enhanced by an interaction with AGB1[111]. However, it is challenging to discriminate whether ard1 phenotypes are caused by its metabolic activity or the altered non-enzymatic moonlighting function of ARD.

The tomato genome contains three ARD genes (Fig. 3). SlARD1 and SlARD2 show mild increase in expression at the beginning of ripening and their expression remains constant until the full-ripe stage[28]. Ectopic expression of an apple ARD in tomato promotes fruit ripening and enhances cold hardiness possibly via increasing ethylene biosynthesis[113]. It is unclear whether ARD has a dual enzyme activity in maturing fruit and whether ARD may perform moonlighting functions as well in the fruit ripening process.

AT: the closing enzyme is yet to be identified

-

The last and the least defined step in the Yang cycle is the conversion of KMTB into methionine. This process requires the function of an AT, which has been elucidated in rat liver and some other organisms[114,115]. ATs play indispensable roles in various metabolic pathways and are comprised of a diverse family. According to the amino donor, the AT family includes aspartate AT (AspAT), tyrosine AT (TyrAT), branched-chain amino acid AT (BCAT), and many others[116]. Several ATs that can close the Yang cycle have been characterized in non-plant organisms, such as an AspAT in Crithidia fasciculata[117], a TyrAT in Klebsiella pneumoniae[118], and a BCAT in Mycobacterium tuberculosis[119]. In Arabidopsis, at least 90 AT genes exist[116]. We have yet to identify which specific AT(s) are involved in the Yang cycle. In mammalian tissue, enzymological and in vivo tracer assays suggest that a glutamine transaminase K (GTK) is likely involved in the conversion of KMTB to methionine[120]. Following comparative genomic analyses and consistency with subcellular localization and gene expression profiles with other Yang cycle genes, tomato, and maize GTK, and omega-amidase are proposed to act in tandem to convert KMTB to methionine in plants[115]. Both the tomato and maize GTK recombinant enzymes prefer glutamine as the amino donor and KMTB as the acceptor[115]. However, Bacillus subtilis GTK or omega-amidase disruption mutants still grow, albeit slower, in a medium having MTR as the sole sulfur source. These results suggest that GTK is not essential for B. subtilis cell growth and other ATs may participate in the transamination of KMTB[115]. It is still unclear whether GTK is the authentic AT that can close the Yang cycle in plants.

An aromatic AT, VAS1 (REVERSAL OF SAV3 PHENOTYPE 1), reversely converts methionine into KMTB in plants. The loss-of-function of VAS1 restores the responses of a shade avoidance mutant in Arabidopsis by promoting the levels of auxin and ACC. VAS1 may serve as a key regulator for mediating the contents of auxin and ethylene in plants[121]. Very recently, VAS1 was found to have a wide function in the biosynthesis and metabolism of three aromatic amino acids, phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan[122]. As these amino acids are basic units of proteins and metabolites in cells, their coordination by VAS1 in amino acid metabolism is significant.

-

The Yang cycle plays crucial roles in mediating sulfur recycling and the homeostasis of multiple important metabolites and signaling molecules in plants, including methionine, SAM, MTA, ACC, PAs, NA, and ethylene. Its essential functions in metabolism make the Yang cycle pivotal for plant development, stress responses, leaf and flower senescence, and crop productivity in both agricultural and horticultural species. We provide an overview table listing studies in plants that describe the enzymes involved in the Yang cycle (Table 1). Despite significant advances in dissecting the biological functions of the intermediate metabolites and enzymes, much remains to be uncovered. For instance, the distinct phenotypes between mutants with complete MTN activity disruption and those lacking MTK highlights that the importance of this cycle is far beyond just recycling the methylthio moiety. The functions of MTI and DEP in plant growth and development also await to be characterized. The moonlighting ARD protein contains a metal-driven dual-activity and acts as a downstream target of the heterotrimeric G protein complexes, further expanding our understanding of the significance of this cycle. A critical gap in our knowledge is identifying the AT involved in the last step of the Yang cycle. Moreover, the originally proposed function of the Yang cycle in modulating ethylene production and fruit ripening awaits to be elucidated. As more insights emerge, we believe that the Yang cycle will reveal itself as a key pathway with fascinating metabolites and enzymes in plant biology.

Table 1. Studies on the enzymes involved in the Yang cycle in plants.

Enzyme Plant species Main content Ref. SAMS Arabidopsis thaliana Excessive methionine accumulates in the mto3-1 and mto3-2 mutants [61,62] Overexpressing SAMS is morphologically indistinguishable from wild-type plants, or leads to abnormal floral organ development [62,65] SAMS is phosphorylated by CDPK28 [74] Nicotiana tabacum Suppressing SAMS renders accumulation of methanethiol and methionine [63] Rice Suppressing OsSAMS1, 2 and 3 causes pleiotropic phenotypes [64] OsSAMS1 functions as a regulator for grain size and yield [67] OsWAK112 interacts with OsSAMS1, 2 and 3 [72] OsSAMS1 interacts with OsLCD3 [76] OsSAMS1 is targeted by F-box protein OsFBK12 [77] Pumpkin SAMS interact with a long non-coding RNA with promoted stability [76] Tomato SlSAMS1 influences fruit ripening and it interacts with FERONIA-like [79] ACS Arabidopsis thaliana The expression of ACS genes are not vascular-specific [6,83] ACS has an additional Cβ-S lyase activity [84] MTN Lupinus luteus Enzyme is purified from seed [86] Arabidopsis thaliana MTN1 and MTN2 exhibit diverse expression patterns, preferentially in vascular tissues [6] The cystal structures of MTN1 and MTN2 are determined [88,89] mtn1 and mtn2 single and double mutants are characterized [42,43] Rice OsMTN recombinant enzyme is characterized [90] Maize ZmMTN1 mutant is linked with Fe and NA hemeostasis [91] Apple MTN activity is first detected in fruit extract [85] Tomato SlMTN expression and activity are characterized in fruit [28,48] MTK Lupinus luteus MTK activity is partially purified from seed [93] Rice OsMTK1 and OsMTK2 are cloned and evaluated under sulfur deficiency [94] Arabidopsis thaliana MTK is preferentially expressed in phloem [6] MTK is cloned and T-DNA insertional mutants are characterized [94] An eto3mtk double mutant is evaluated [95] Tomato SlMTK expression and activity are characterized in fruit [28,48,96] MTI Arabidopsis thaliana MTI is cloned and shows phloem-specific in expression [6] The functions of MTI in sulfur metabolism during flowering and seed development is evaluated [99] DEP Arabidopsis thaliana DEP is cloned and its expression also shows phloem-specific [6] The functions of DEP in sulfur metabolism during flowering and seed development is evaluated [99] Apple MdDEP1 is ectopically expressed in Arabidopsis, enhancing stress tolerance and flowering [100] The expression of MdDEP1 is regulated by MdBHLH3, and the activity is affected by MdY3IP1 [101,102] ARD Rice ARD has dual enzymatic activity with different binding metals, OsARD1 is induced by submergence and ethylene [107] OsARD1 promotes stress tolerance [110] Potato StARD1 is wounding responsive [109] Arabidopsis thaliana ARD1 function in hypocotyl growth is evaluated, ARD1 is an effector for AGB1 [111] Tomato The expression of SlARD1 and SlARD2 is characterized in fruit [28] Apple The physiological roles of an apple ARD gene are investigated by ectopically expressing in tomato plant [113] AT Tomato and maize GTK is proposed to convert KMTB to methionine [115] This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32402638 to DL) and the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LQ24C020001 to DL). BVDP also acknowledges financial support of European Research Council under the European Union's Horizon Research and Innovation Programme (Grant Agreement No. 101087134; ERC-2022-CoG 'Ethylution'). JM is financially supported by the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO) by a PhD-fellowship (11H3325N).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: review conception and design: Li D, Chen K; figures illustration: Chen H; draft manuscript preparation: Li D, Chen H, Zhao Z, Chen J, Mertens J, Van de Poel B, Chen K. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

-

The datasets generated and analyzed in Fig. 3 are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The Yang cycle proteins in each species were identified using BLAST with an E-value threshold of 1e−5, employing the default settings of TBtools-II[123]. Searches were conducted with the amino acid sequences of each enzyme from Arabidopsis thaliana as references.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Chongqing University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Chen H, Zhao Z, Chen J, Mertens J, Van de Poel B, et al. 2025. The Yang cycle in plants: a journey of methionine recycling with fascinating metabolites and enzymes. Plant Hormones 1: e007 doi: 10.48130/ph-0025-0007

The Yang cycle in plants: a journey of methionine recycling with fascinating metabolites and enzymes

- Received: 24 February 2025

- Revised: 13 March 2025

- Accepted: 17 March 2025

- Published online: 10 April 2025

Abstract: Methionine is a sulfur-containing amino acid that plays an essential role in plant growth and development. In contrast to its low abundance, methionine is highly demanded in various physiological processes, such as ethylene biosynthesis during fruit ripening. To sustain methionine levels, plants trade-off adenosine triphosphate to recycle the methylthio group through a metabolic pathway commonly known as the Yang cycle. Over the years, significant progress has been made in identifying the intermediate metabolites and enzymes involved in this cycle. While our understanding of the biological functions of certain metabolites and enzymes in the Yang cycle has expanded, there are still many important questions left unanswered. Notably, the aminotransferase responsible for the final step of the cycle has not yet been identified. This review provides a comprehensive overview of the metabolic roles of these metabolites and the biological significance of individual enzymes in the Yang cycle. We also discuss the regulatory influence of this cycle on ethylene production in plants.

-

Key words:

- Yang cycle /

- Methionine /

- Ethylene /

- Recycling