-

Over the past decades, significant advances have been made in the understanding of plant hormone biosynthesis, metabolism, transport, and signaling[1]. Classical approaches have provided deep insights into their function, revealing that they regulate virtually every stage of life, from early development and germination to flowering and fruit production. Thus, given their pivotal roles, plant hormone research holds immense promise for being translated into other fields such as agriculture, offering strategies to enhance crop productivity and address global food security challenges. Nevertheless, despite the significant advances in the field, the intricate regulatory networks underlying hormone functioning remain only partially understood[2]. With the advent of high-throughput technologies, biological research has been revolutionized, which has allowed for the generation of vast amounts of datasets aimed at fulfilling these knowledge gaps. However, for fully exploiting the potential of these datasets, advanced computational approaches are required.

It is undeniable that artificial intelligence (AI) is emerging as a transformative tool for plant biology research. The integration of large-scale datasets with AI can reveal novel regulatory components and uncover patterns that classical methods might overlook. This synergy between biology and computational sciences increases the potential of in silico analyses, offering deeper insights into plant hormone regulation and their broader physiological roles. As hormone research expands, its combination with AI-driven approaches will be essential for solving longstanding questions in the field and unlocking new real-life applications, from identifying key regulatory components to optimizing hormone-mediated traits towards more sustainable food production systems.

-

Over the past 40 years, plant hormone research has exponentially expanded[3]. Among classical hormones, ethylene (ETH) gained particular interest in the early 2000s, highlighting its critical role in plant biology (Fig. 1a). Currently, together with auxins (AUX) and abscisic acid (ABA), a significant number of research projects focus on elucidating their biological functions, addressing key knowledge gaps that must be resolved to unlock the full potential of this field.

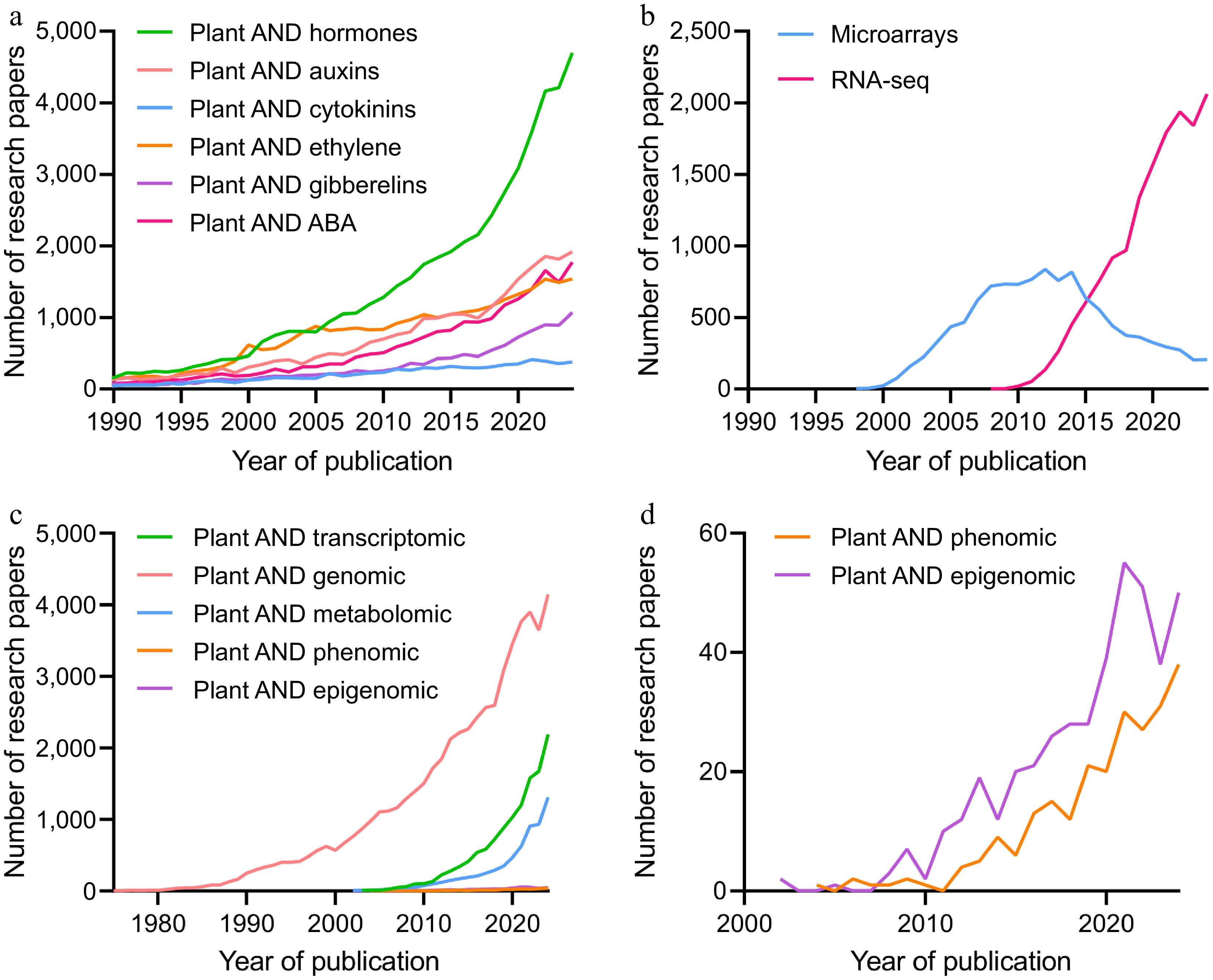

Figure 1.

(a) Number of research papers published on plant hormones, (b) transcriptional data, and (c) plant omics over the past 40 years. (d) A close-up view of 'plant AND phenomic' and 'plant AND epigenomic'. Data were obtained from Scopus on February 13, 2025, based on the number of publications containing the indicated keywords in titles, abstracts, or keywords.

Simultaneously, the post-genomic era has generated a wealth of transcriptional data, driven by the advances in next-generation sequencing technologies (Fig. 1b). This has led to a substantial increase in omics datasets deposited into public repositories, which is reflected in the growing number of related research publications. Following a similar trend, classic omics disciplines such as genomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics have experienced a significant growth since their emergence (Fig. 1c), while newer fields studying phenotypic variations and epigenetic regulation have only gained importance over the last years (Fig. 1d). More recently, the concept of hormonomics was introduced[4,5]. As a subdivision of metabolomics, hormonomics analyses aim to provide comprehensive and complete hormonal profiles of individual samples[6]. This emerging field underscores the need for holistic approaches that can integrate these complex hormonal networks with the traditional omics analyses.

This rapid accumulation of data highlights the dynamic evolution of plant sciences, demonstrating the vast amount of information that can be extracted from biological assays. Moreover, the continuous expansion of databases creates a gold mine of information, offering an invaluable resource for all biological disciplines and driving significant advances over the past two decades[7−9]. Nevertheless, maximizing the impact of these datasets requires their effective integration to create holistic viewpoints and derive meaningful insights. In this context, AI has emerged as a powerful tool to take advantage of it. Research projects where AI plays a central role have increased exponentially, as it enables more efficient processing and analysis of large datasets.

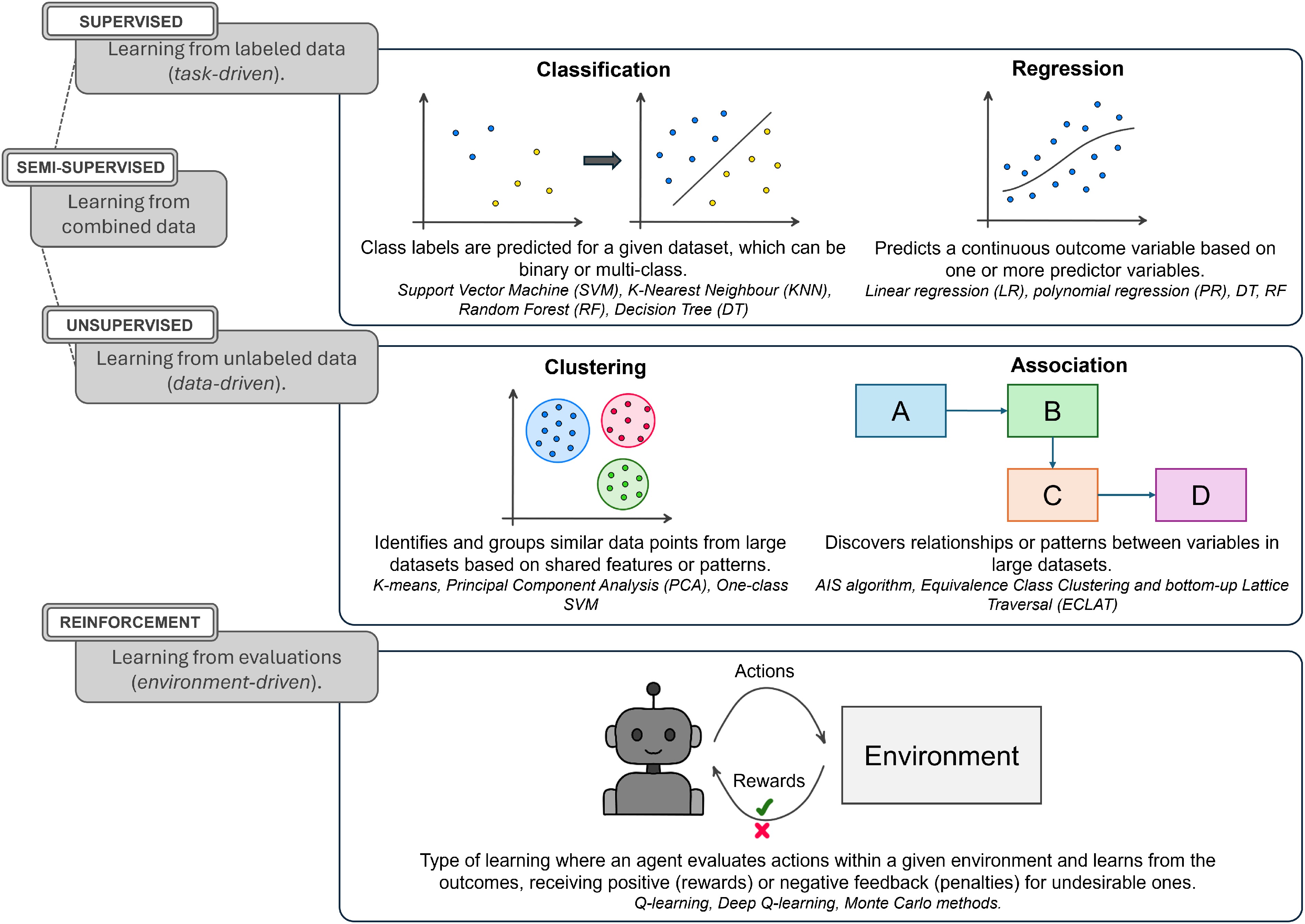

As a brief introduction, AI refers to computational processes designed to perform high-level tasks that typically require complex data processing, such as pattern recognition, decision-making, and problem-solving, which are functions traditionally associated with human intelligence. Within AI, one of the most prominent approaches is machine learning (ML), which can analyze complex multidimensional datasets to identify patterns and classify or make predictions using statistical tools[10]. A key aspect of ML is how models learn from data, which can be categorized into different approaches. For instance, in supervised learning, a training step that labels the data for subsequent processing of unlabeled datasets is required. In contrast, unsupervised learning strategies can directly process unlabeled datasets, extracting patterns without previous training on labeled data[11]. Reinforcement learning, on the other hand, evaluates actions within a given context (or environment) and learns from the outcomes by receiving positive (rewards) or negative (penalties) feedback[12]. A simplified overview of ML approaches is provided in Fig. 2. These analytical capacities have made ML an essential tool in several scientific fields, including biology and agriculture.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of different machine learning (ML) approaches, categorized by learning type and functionality.

Deep learning (DL) represents a more specialized and powerful AI approach. DL employs artificial neural networks (ANNs) – computational structures inspired by biological neural architectures – to process large annotated datasets hierarchically. This enables DL models to automatically learn more abstract and complex representations and patterns[13]. As a result, DL has become particularly valuable for handling highly complex datasets, such as those found in genomics, plant phenotyping, and environmental modeling.

Nevertheless, it is important to emphasize that selecting the appropriate approach is a crucial decision. A more powerful tool does not necessarily yield better results. For example, if a simple linear regression produces an accurate model, using a multiple linear regression or a DL-based regression may be unnecessary. Adding irrelevant predictors can increase model complexity and potentially lead to overfitting rather than improving accuracy. Therefore, researchers must carefully select the most appropriate method when applying AI to complex datasets. Nevertheless, it is important to note that there are few examples of guidance regarding method selection and failed models in the literature, as highlighted by Greener and collaborators[14] during the development of their detailed guide on the use of ML in biological sciences. This gap in guidance underscores the need for researchers to carefully consider their method choices when applying AI to complex datasets.

-

Classically, plant hormone molecular mechanisms have been studied using genetic analyses. A commonly used strategy is the study of large collections of mutants to find relevant phenotypes and their associated causal genes[15]. This way, through large-scale screening, several hormonal processes have been elucidated, such as the classical example of the characterization of AUX transport by PIN trafficking networks[16].

Unfortunately, these techniques have some limitations in resolving traits regulated by complex, interconnected mechanisms or redundant genes. Rather than being an exception, such redundancy is a common feature in plants, where gene duplication events have led to the emergence of paralogs capable of buffering perturbations through active compensation[17]. This complex regulation limits the success of such approaches to link genomes with phenotypes, or, in the other direction, phenotypic alterations with their responsible gene mutations[18]. Together with the complexity of the traits that remain unexplored, the limitations of classical approaches are evidenced by the slowing down of the success of these strategies to provide new discoveries[19].

The potential integration of AI-driven approaches does not imply that classical methods such as forward and reverse genetics are obsolete. Instead, their combination offers a powerful and promising perspective for advancing plant biology. Moreover, this relationship is not a one-sided dependency in which empirical research merely benefits from AI advancements. While computational analyses can detect patterns in complex datasets, their predictive power must be guided in a biologically meaningful direction to avoid generating misleading conclusions. Therefore, the synergy between empirical and computational approaches will be most effective when they inform and refine each other: while AI-driven analyses maximize the value of experimental data, empirical research provides the necessary validation and direction to optimize computational models.

Nevertheless, the generation of biological data for AI-driven analyses often relies on datasets that are difficult to normalize, as they are highly dependent on experimental conditions and influenced by both controlled and uncontrolled variables. For example, when studying the effects of salinity in Arabidopsis thaliana, the duration and severity of salt treatments – factors that can strongly influence results – can be accurately controlled. However, factors such as temperature fluctuations, light intensity, and manual sample handling can introduce variability that is challenging to standardize across experiments.

This issue is particularly relevant for complex biological processes, where strict spatiotemporal regulation can cause the same effector to exhibit opposing effects. For instance, the MITOGEN-ACTIVATED PROTEIN KINASE KINASE 9 (MKK9), involved in ethylene regulation through the activation of the MKK9-MITOGEN-ACTIVATED PROTEIN KINASE 3/6 (MPK3/6) cascade[20], has been reported as both a positive and negative regulator of salt responses[21,22]. Such discrepancies do not necessarily indicate errors but rather reflect differences in the experimental setup that may alter MKK9 function[18]. This variability is a common feature of regulatory proteins embedded in intricate molecular networks, where the balance between positive and negative regulators determines the final outcome[23].

Meta-analyses are an effective way to reduce such variability by combining diverse datasets from independent empirical assays to draw novel and robust conclusions[24]. While meta-analyses do not necessarily require AI, incorporating it enables a higher degree of abstraction, facilitating the integration of complex data from different conditions. AI-driven approaches, such as ML-based meta-analyses, help to minimize experimental biases and extract generalizable insights from these datasets. For example, ETH has long been associated with specific stress responses, but its broader involvement in general stress regulation has been overlooked. Nevertheless, in a recent ML-driven meta-analysis, its role appears to be more universal, as it regulates over 50% of the genes responsible for general stress responses[25]. Similarly, the biological implications of other plant hormones have been studied by using AI approaches to uncover roles that are not classically associated with them. For instance, supervised ML approaches, such as random forest (RF) and decision trees (DTs), have characterized the role of ABA as extending beyond water-related stress, highlighting its regulatory functions in both biotic and abiotic stresses[26].

In the context of the previously mentioned meta-analysis, applying DL methods to link transcriptomic data to specific phenotypes provides an opportunity to introduce additional layers of complexity. For instance, DL models can account for gene redundancy by incorporating gene sequence similarity into the analysis, recognizing that gene duplication often results in functional similarities between genes. This added layer allows DL models to capture subtle patterns across datasets, ultimately enhancing the interpretation of results and revealing meaningful connections that might otherwise be overlooked.

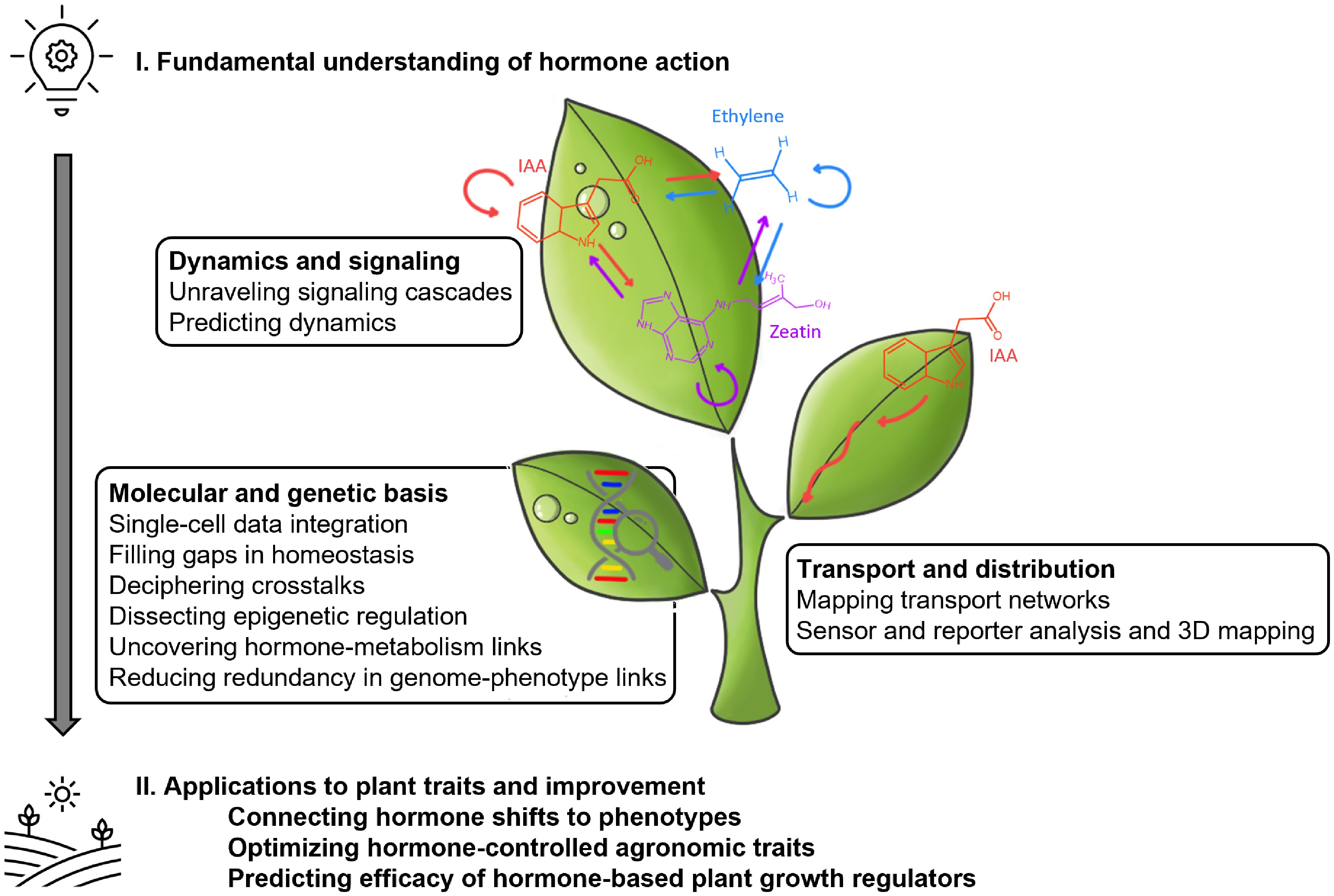

Yet, the application of AI in plant hormone research goes beyond meta-analyses, with several specific examples outlined in Fig. 3, illustrating its diverse applications within the field. AI has been increasingly employed to construct models revealing hormone involvement in complex processes. In this line, ML analyses have been largely used to optimize in vitro cultures by adjusting media compositions, generating models that predict the optimal levels of hormones, nutrients, and other conditions[27]. In the field of genomics and proteomics, the increasing availability of high-quality genomes has led to significant advances in gene expression predictions and protein annotation[28]. The breakthrough achieved by Alphafold in protein structure prediction has revolutionized the field, providing invaluable insights into uncharacterized hypothetical proteins and facilitating rational studies towards their empirical characterization[29]. Despite these advances, plant genomes characterization remains incomplete. In Arabidopsis, only 60% of the proteome has an assigned function, with just 30% experimentally validated[30]. This underscores that translating genomic information into functional insights remains a challenge even in the post-genomic era.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of potential applications of AI in plant hormone research. Data from different biological layers (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics) can be integrated using artificial intelligence (AI) to unravel the complex regulatory networks underlying plant hormone function, and how a fundamental understanding of hormone action can be translated into practical applications in agriculture. Each leaf represents a key topic in hormone biology. Three representative hormones: ethylene, indole-3-acetic acid (IAA; auxin), and zeatin (cytokinin) are depicted as example molecules.

Furthermore, DL techniques have become increasingly integral in plant phenomics and computer vision analysis, enabling high-throughput, automated phenotyping with unprecedented precision[31]. By leveraging convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and other advanced DL models, researchers can accurately analyze complex plant traits from images, monitor plant growth in real-time, and predict phenotypic outcomes with greater efficiency. These advancements have significant implications for accelerating plant breeding, improving crop management, and enhancing our understanding of plant physiology.

In addition to deep learning techniques, Large Language Models (LLMs) have shown great potential in biological and biomedical research[32]. These models are able to process vast amounts of textual data, including scientific literature, and could play a vital role in analyzing experimental results, enabling the extraction of key insights and relationships that might be overlooked by traditional methods. Although these approaches depend on their training and require special attention to avoid introducing errors, LLMs have the potential to predict gene-hormone interactions, identify novel hormone regulators, and even propose hypotheses for experimental validation, thereby accelerating the discovery of new regulatory mechanisms in plant hormone research.

Finally, and equally important, the use of AI can be a game changer in contexts where financial constraints significantly impact research. Beyond its previous applications, AI can play a crucial role in streamlining research projects by enabling rational decision-making, ultimately reducing costs. For instance, when the potential outcomes of a research project are uncertain, initial proposals often require broad data analyses, involving numerous samples and conditions. A preliminary AI analysis taking advantage of public databases can help to refine the research approach by identifying the most promising directions. By integrating insights from existing datasets, AI can guide the selection of key variables and experimental conditions, minimizing resource use and enhancing the overall efficiency of research efforts.

-

A fundamental limitation for the application of AI across disciplines, including biological sciences, is data quality. As commonly stated in AI-driven research, the reliability of the output is dependent on the quality of the input – summarized by the principle 'garbage in, garbage out'[33]. In this context, researchers must critically assess the datasets used for model training and analysis, as this initial step is crucial for generating meaningful and biologically relevant conclusions. To reduce these issues, best practices have been established to enhance transparency and minimize the risks and limitations of AI-driven analyses[34]. One approach will be the generation of data under the FAIR data principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable), which promote standardized, high-quality datasets[35].

Beyond data quality, the formulation of clear biological questions is essential to ensure that AI models are applied effectively. Given the vast computational power of AI, it is critical that data processing, experimental design, and quality controls are carefully structured to maintain the integrity of the results. Similar to empirical research, the design of AI-driven analyses plays a pivotal role in ensuring robust and interpretable findings. While AI models typically undergo validation to assess their accuracy and robustness[36], this type of validation primarily focuses on technical performance. However, we propose an additional concept, biovalidation, which refers to the evaluation of AI-generated outputs in the context of their biological relevance. This step ensures that the results align with established biological knowledge, either through in silico comparisons with previous studies or through empirical validation in experimental settings. By incorporating biovalidation as a standard practice, AI applications in biological sciences can achieve greater reliability and biological significance.

Another critical challenge is the reproducibility of AI-driven results[37]. Errors in data processing or pipeline implementation can lead to misleading conclusions, underscoring the need for transparency and replicability in AI workflows. A related challenge is interpretability, or the ability to understand how a ML approach processes data and makes decisions[14]. While simpler models like linear regression are more interpretable, DL models tend to be more opaque. Integrating biological data into AI models has been proposed as a way to improve their transparency[38]. Additionally, incorporating biovalidation as a standard practice can further enhance interpretability by ensuring that AI-generated outputs are biologically meaningful and aligned with existing knowledge.

Addressing these challenges requires expertise in both computational and biological methodologies. Given the interdisciplinary nature of AI applications in biology, a key solution will be the integration of multidisciplinary research teams that combine expertise in computational sciences, statistics, and experimental biology[39]. This collaborative approach can enhance the reliability, reproducibility, and biological relevance of AI-driven discoveries.

-

As plant researchers, our ultimate goal is to bridge the gap between plant biology and real-world applications, aiming for a more sustainable and equitable society. Plant hormones play a critical role in agriculture, not only regulating crop responses to environmental stressors but also influencing yield quantity and quality. The integration of AI technologies, particularly DL, with transfer learning for continuous model updates and improvements, has the potential to revolutionize this field[40].

The application of AI in agriculture has been anticipated as the next step in the Green Revolution, referred to as Green Revolution 2.0. This term describes the integration of advanced technologies, such as AI, genomics, and precision agriculture, to sustainably enhance crop productivity, resource efficiency, and resilience to environmental challenges[41]. AI can optimize farming practices by enabling real-time monitoring of crop health through image analysis obtained from drones or sensors, predicting yield outcomes based on environmental data, improving resource management through precision irrigation and fertilization, and facilitating the rapid development of stress-tolerant plant varieties, as discussed in previous sections. Together, these advances are expected to lead to more efficient, sustainable, and resilient agricultural systems.

However, this evolution in agriculture mirrors a historical turning point prior to the original Green Revolution in the mid-20th century, when fertilizers were seen as the solution to improving yields[42]. While promising, these innovations brought unforeseen challenges: crops could not handle the increased biomass. It was then that plant hormones emerged as key players. The discovery of crop varieties with reduced gibberellin levels or signaling and limited apical elongation addressed this issue, offering a sustainable way to enhance yield potential[43].

Today, we find ourselves in a similar scenario where AI offers the promise of transforming agricultural productivity. However, the implementation of the proposed use of AI in agriculture will require extensive field digitalization, which may be unaffordable for small-scale farmers. In addition, the increasing frequency and severity of adverse environmental conditions due to climate change still present extra challenges, since they are the main effectors of crop losses[44]. Plant stress responses, which are usually multifactorial[45], remain not fully understood, posing a challenge to AI-driven solutions. For instance, heat, drought, and intense light often occur simultaneously, each triggering specific signaling pathways while collectively altering plant physiology, which strongly depends on hormonal regulation. This complexity underscores the need for deeper insights into hormone-mediated stress responses to develop reliable and adaptable agricultural strategies, which, as mentioned earlier, could be addressed by AI approaches.

Nevertheless, agricultural data are diverse and complex, ranging from soil composition and plant health data to satellite imaging, and often contain high-dimensional, incomplete, and noisy information[46]. In addition, much of the knowledge that guides practical farming decisions comes from real-time observations passed down through generations. AI methods, such as ANNs, have the potential to integrate these data sources. Currently, they are used in agriculture to address different challenges, including crop management (such as quality and yield optimization), pest and weed control, and water and soil resource management. In addition, there is evidence that ML, when applied to crop mapping and recognition, provides a robust methodology for identifying and characterizing crop varieties[47]. However, we are still far from reaching its full potential. Thus, the success of the AI technology applied to crops will depend on a two-way transfer of knowledge. Farmers' insights will be crucial in building and refining AI models, ensuring that they consider real-world agricultural complexities. In addition, their deep understanding of plant behavior under variable conditions can provide essential context for further studying hormone-driven stress adaptations. By integrating this expertise with AI-driven analyses, researchers can uncover new dimensions of hormone regulation in the field, leading to improved crop management strategies. In turn, AI models can help farmers make data-informed decisions, optimizing agricultural practices while enhancing productivity and resilience. This collaboration between technology and traditional knowledge will be key to advancing AI-driven agriculture, leading to a real Green Revolution 2.0.

In conclusion, AI presents transformative opportunities for both plant research and agriculture, but its success hinges on bridging computational advancements with biological expertise and practical knowledge. Overcoming challenges such as data variability, model interpretability, and accessibility will require not only interdisciplinary collaboration but also the adoption of best practices in AI development, including robust data curation, transparent modeling, and continuous validation and biovalidation. By fostering a two-way exchange between AI-driven insights and biological expertise, we can refine predictive models and uncover the missing pieces of the puzzle in hormone biology. This synergy will not only deepen our understanding of hormone-mediated regulation but also has the potential to enhance agricultural productivity and resilience, contributing to the development of sustainable agricultural practices.

Sanchez-Munoz R acknowledges the Generalitat de Catalunya for the postdoctoral grant under the Beatriu de Pinós programme (Grant No. 2023 BP 00088). Roig-Villanova I is a professor under the Serra Húnter Plan (Generalitat de Catalunya).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design, writing − draft manuscript preparation: Sanchez-Munoz R; writing − critical revision: Roig-Villanova I; writing − review of the final manuscript: Sanchez-Munoz R, Roig-Villanova I. Both authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data analyzed during this study is included in this published article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Chongqing University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Sanchez-Munoz R, Roig-Villanova I. 2025. When AI meets hormones: opportunities and challenges of AI for advancements in plant hormone research and agriculture. Plant Hormones 1: e016 doi: 10.48130/ph-0025-0016

When AI meets hormones: opportunities and challenges of AI for advancements in plant hormone research and agriculture

- Received: 22 March 2025

- Revised: 18 June 2025

- Accepted: 27 June 2025

- Published online: 20 August 2025

Abstract: Advancements in plant hormone research have significantly deepened our understanding of their roles in plant physiology. However, there are still knowledge gaps in the complex regulatory networks that govern hormone functions. While high-throughput technologies have generated vast datasets over the last few years, fully exploiting this information requires advanced computational tools. Artificial intelligence (AI) is emerging as a transformative tool in plant biology, facilitating the integration of large datasets to uncover hidden regulatory components and improve our understanding of hormone regulation. This perspective explores the synergy between classical plant biology and AI-driven approaches, emphasizing how they can overcome the limitations of traditional methods. By examining the potential applications of AI in plant hormone research – from optimizing in vitro cultures to improving gene expression analyses – we expose how AI can provide novel, biologically significant insights that may lead to a paradigm shift in the field. Importantly, we also address key challenges in AI-driven analyses, such as data quality, reproducibility, interpretability, and biological relevance, emphasizing critical considerations for effectively applying AI methods. Finally, as AI continues to integrate into plant research, we explore its potential to drive the next phase of the Green Revolution, optimizing agricultural productivity, sustainability, and food security.

-

Key words:

- AI /

- Artificial Intelligence /

- Machine learning /

- Deep learning /

- Plant hormones