-

Phytohormones play an essential role in coordinating growth, development, and stress responses throughout the plant life cycle. Phytohormone signaling pathways do not however function in isolation, but are rather tightly associated with endogenous and environmental cues. As sessile organisms, plants adjust their growth and development in response to abiotic and biotic stresses, and phytohormones serve as important signals under abiotic stress conditions, including drought, high salinity, heat, cold, and flooding[1]. The molecular bases of phytohormone signaling have been revealed through major genetic and molecular biological studies, which have identified key signaling components such as receptors, kinases, and transcription factors. Moreover, in vivo dynamics of phytohormones are currently able to be observed using genetically encoded biosensors, for example, for abscisic acid (ABA)[2,3] and for auxin[4]. In addition, an amperometric and minimally invasive sensor that can be attached to plant leaves, has been developed to detect phytohormones simultaneously[5]. Despite these advances in our understanding of phytohormones at the molecular level and the development of quantification technologies, little is known about their upstream signaling events. This is partly because the receptors or sensors of various environmental cues remain largely obscure and, in some cases, debated, and partly because phytohormone levels fluctuate dynamically in response to environmental conditions. As a result, how environmental signals are integrated into phytohormone signaling remains largely unknown.

Given these gaps in our understanding, current knowledge is summarized here by highlighting recent advances in the upstream events of phytohormone signaling, mainly focusing on the topics not covered in previous articles[1,6]. It is also emphasized that all nine narrowly defined phytohormones are involved in stress responses, albeit to a varying extent, and provide a global picture of phytohormone signaling under abiotic stress conditions and their interactions with each other. To keep the context coherent among phytohormones, which have been studied in varying depth, we are particularly interested in the transcriptional cascade starting from the phytohormone perception, as well as their metabolism, regarding environmental stress conditions. Given our focus on recent advances and the space limitation, we are unable to comprehensively cover the broader aspects of phytohormones in stress responses. These topics have been well summarized in other reviews, including those on abiotic stress[1], high-salinity stress[7], and temperature stresses[8].

-

ABA plays an important role in controlling responses to various stresses, and its signal transduction under drought stress conditions is currently thought to be initialized by three scenarios: de novo biosynthesis, conversion of the inactive form from storage, and activation of signaling components. Given ABA metabolism is covered elsewhere[6,9], herein, recent advances in ABA signaling are highlighted.

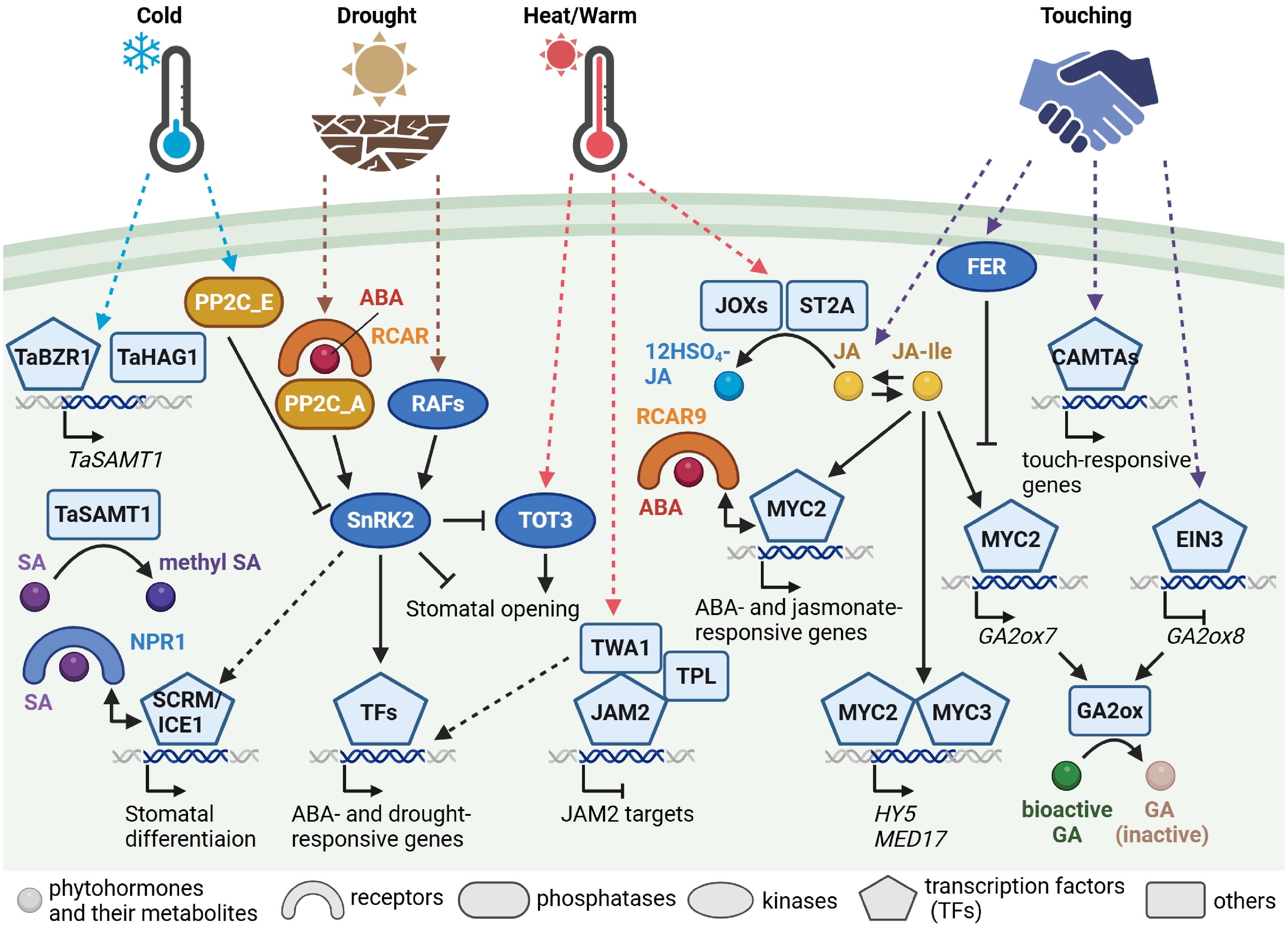

Three families of proteins play a pivotal role in ABA perception and signaling[10,11] (Fig. 1). ABA is perceived by cytosolic receptor proteins, named REGULATORY COMPONENTS OF ABA RECEPTOR (RCAR), PYRABACTIN RESISTANCE1 (PYR1), or PYR1-LIKE (PYL), and then the complex is formed with the co-receptors, clade A protein phosphatases of type 2C (PP2C). Whilst the PP2Cs interact with and inhibit subclass III sucrose non-fermenting-1 (SNF1)-related protein kinase 2s (SnRK2s) in the absence of ABA, in response to ABA, the SnRK2s are released from the inhibition by the PP2Cs[10,11]. It had been thought that the released SnRK2s were activated by auto-phosphorylation until the identification of their upstream kinases. A study in the moss Physcomitrella patens first reported a Raf-like MAP kinase kinase kinase (MAPKKK), which is referred to as RAF hereafter, activating the SnRK2s under osmotic stress conditions[12]. Then, the Arabidopsis homologs were identified and characterized[13−16] (Fig. 1). Among subgroup B RAFs in Arabidopsis, several B2 and B3 RAFs phosphorylated ABA-activated SnRK2s, whilst several B4 RAFs phosphorylated ABA-unresponsive, i.e., subclass I, SnRK2s. Further studies uncovered the detailed mechanism of how the SnRK2s are activated in response to drought stress[17,18]. Under control conditions, the constitutive active B2 RAFs, including RAF7, RAF10, RAF11, and RAF12, phosphorylate subclass III SnRK2s, which are also inhibited by the PP2C phosphatases, and thus ABA signaling is turned off. In response to drought stress, the ABA receptors block the PP2Cs' inhibition on the SnRK2s, and the constitutive active B2 and drought stress-activated B3 RAFs activate the SnRK2s, switching the signaling on. The B3 RAFs, such as RAF3, RAF4, and RAF5, are likely associated with stress perception and initiating the signaling, yet the underlying mechanism remains elucidated.

Figure 1.

Abiotic stress signaling associated with abscisic acid, jasmonate, and salicylic acid signaling and metabolism. Simplified signaling pathways from phytohormone perception to transcriptional regulation of abscisic acid (ABA), jasmonate, and salicylic acid (SA) in response to drought, heat, or warm temperature, cold, and touching stresses. Key signaling components are illustrated using different shapes, as indicated. Arrows represent activation, T-shaped lines indicate inhibition, and dashed lines denote proposed or indirect pathways. 12HSO4-JA, 12-hydroxy jasmonoyl sulfate; BZR1, BRASSINAZOLE-RESISTANT 1; CAMTA, calmodulin-binding transcription activator; EIN3, ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE 3; FER, FERONIA; GA, gibberellin; GA2ox, GA 2-oxidase; HAG1, HISTONE ACETYLTRANSFERASE OF THE GNAT FAMILY 1; ICE1, INDUCER OF CBF EXPRESSION 1; JA, jasmonic acid; JA-Ile, jasmonoyl-isoleucine; JAM2, JASMONATE-ASSOCIATED MYC2-LIKE 2; JOX, JASMONATE-INDUCED OXYGENASE; MED17, MEDIATOR SUBUNIT 17; NPR1, NONEXPRESSOR OF PATHOGENESIS-RELATED GENES 1; PP2C_A, clade A protein phosphatases of type 2C (PP2C); PP2C_E, clade E PP2C; RAF, Raf-like MAP kinase kinase kinase; RCAR, REGULATORY COMPONENTS OF ABA RECEPTOR; SAMT1, SA METHYLTRANSFERASE 1; SCRM, SCREAM; SnRK2, sucrose non-fermenting-1 (SNF1)-related protein kinase 2; ST2A, SULFOTRANSFERASE 2A; TOT3, TARGET OF TEMPERATURE 3; TPL, TOPLESS; TWA1, THERMO-WITH ABA-RESPONSE 1. Created with BioRender.com.

SnRK2s are unique to plants among the calcium-dependent protein kinase (CDPK)-SnRK superfamily, and a part of them, grouped into subclass III, were activated by osmotic stress and ABA in Arabidopsis[19], and rice[20]. Subclass III SnRK2s and their substrates have been extensively studied in ABA-dependent gene expression and stomatal closure[21,22]. By contrast, subclass I SnRK2s activated in response to osmotic stress were reported to be involved in post-transcriptional regulation via mRNA decapping complex[23,24] and root hydraulics via aquaporins[25]. Interestingly, in contrast to the earlier view on subclass I SnRK2s being unresponsive to ABA[19], accumulating evidence[25−27] suggested that these SnRK2s, such as SnRK2.4 (also known as SRK2A), are also under the control of ABA coreceptors, such as ABA INSENSITIVE 1 (ABI1). Moreover, a recent study proposed that the condensation of subclass I SnRK2s in response to molecular crowding under osmotic stress conditions led to their spatial isolation from the PP2Cs and, subsequently, their activation[28]. Although subclass I SnRK2s were known to form punctate structures in response to osmotic and high-salinity stresses[23,29], Yuan & Zhao[28], further revealed that the condensation was formed via liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) and required the C-terminus intrinsically disordered region of the SnRK2s. Collectively, both subclass I and III SnRK2 kinases are likely controlled by two-layered regulations: release from the inhibition by the PP2C phosphatases dependently of ABA and its receptors and activation via ABA-independent mechanisms, including LLPS and/or RAF kinases, in response to drought and osmotic stresses.

The role of ABA has been studied in association with water availability caused by drought and osmotic stresses. Yet, freezing and heat stresses are also associated with plant water availability in terms of forming ice and cooling via evaporation, respectively, although relatively little is known about how ABA signaling functions in response to altered temperature. In cold stress signaling, SnRK2.6 (also known as SRK2E or OPEN STOMATA 1 [OST1]) was reported to activate cold-induced transcriptional networks under the control of a clade E PP2C at the plasma membrane[30] (Fig. 1). However, the involvement of the INDUCER OF CBF EXPRESSION 1 (ICE1) transcription factor downstream of SnRK2.6[31] might need to be revalidated, as detailed in the salicylic acid (SA) section below. By contrast, whether ABA is involved in heat stress responses has long been obscure. Notably, a screening study for altered ABA-responsive gene expression recently isolated a temperature sensor, THERMO-WITH ABA-RESPONSE 1 (TWA1)[32] (Fig. 1). TWA1 is a possible intrinsically disordered protein and, in response to elevated temperatures, exhibited accumulation in nuclear subdomains with the JASMONATE-ASSOCIATED MYC2-LIKE 2 (JAM2) transcription factor and the TOPLESS (TPL) corepressor. Moreover, TWA1 was involved in the induction of several heat-shock responsive genes, probably indirectly, suggesting that TWA1 is a temperature-sensing transcriptional co-regulator for thermotolerance. By contrast, the high-temperature-associated kinase, named TARGET OF TEMPERATURE 3 (TOT3), was revealed to be regulated by SnRK2.6 in ABA signaling in the stomatal opening[33] (Fig. 1). TOT3 phosphorylated and activated plasma membrane H+-ATPases involved in stomatal opening in response to increased temperature, whilst SnRK2.6 inhibited TOT3 via phosphorylation under drought to prevent water loss. Given that multifactorial stress combinations, such as drought and extreme temperature occurs more frequently nowadays due to global warming and climate change, further investigation on ABA signaling in response to combined stress will aid to apply for future agriculture.

-

Jasmonates, phytohormones derived from fatty acid oxygenation, consist of several variants, including jasmonic acid (JA), methyl jasmonate (MeJA), and jasmonoyl-isoleucine (JA-Ile), and are involved in various stress responses, such as immune signaling. Their role under drought stress conditions has also been investigated, and it appears to differ from that of ABA. For instance, whilst ABA sharply accumulated in response to decreased soil water contents, jasmonate biosynthesis, and signaling were attenuated only in later stages under prolonged mild drought stress conditions[34]. Recently, altered levels of bioactive JA-Ile, obtained by manipulating the enzyme converting JA to JA-Ile, resulted in pleiotropic effects on growth and stress responses[35], and similar phenotypes were also reported by the manipulation of the enzyme converting JA to its hydroxylated form[36]. Moreover, the enhanced drought stress tolerance due to elevated JA-Ile appeared to be somewhat negatively associated with ABA contents[35,36]. However, jasmonate and ABA signaling pathways might not interact with each other in simple synergistic or antagonistic manners. In this regard, it is noteworthy that the MYC2 transcription factor, which regulates both jasmonate- and ABA-responsive genes, interacted with an ABA receptor RCAR9 (also known as PYL6)[37] (Fig. 1). Further studies will reveal more detailed mechanistic understanding as to how jasmonate and ABA signaling interact and this will in turn extend our understanding of their roles under drought.

Jasmonates also play a unique role in touching stress responses. Plants respond to mechanical stimuli, and touch-induced developmental alterations in a process termed thigmomorphogenesis[38]. These are gradual morphological alterations and as such differ from the rapid responses seen in some species, such as the Venus flytrap. An earlier study in Arabidopsis demonstrated that touching induced jasmonate accumulation and jasmonate signaling was involved in touch-induced delayed flowering and reduced rosette size via thigmomorphogenesis[39]. More detailed and complex signaling networks were recently uncovered. A reverse genetic approach revealed that the receptor-like kinase FERONIA negatively regulated jasmonate-dependent touch signaling[40] (Fig. 1). Given that FERONIA plays an essential role in mechanical signal transduction[41], their findings demonstrated that MYC2-mediated jasmonate signaling in response to touching was attenuated by FERONIA to fine-tune the response. Additionally, CALMODULIN-BINDING TRANSCRIPTION ACTIVATORs (CAMTAs), CAMTA3 and its homologs CAMTA1 and CAMTA2, regulated the jasmonate-independent pathway[40]. Moreover, an antagonistic interaction between jasmonates and ethylene regarding GA catabolism was demonstrated[42]. Jasmonate signaling via the MYC2 transcription factor induced GA 2-OXIDASE 7 (GA2ox7), encoding a GA-inactivating enzyme, in response to touching, leading to thigmomorphogenesis, whilst touching also stimulated ethylene signaling and repressed GA2ox8 via the ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE 3 (EIN3) transcription factor. From these studies, it can be concluded that jasmonates may promote thigmomorphogenesis under adverse conditions, and ethylene may prevent excessive responses.

In addition, jasmonate signaling was recently suggested to be involved in thermomorphogenesis[43] (Fig. 1). Warm temperature stimulates JA catabolism, especially toward 12-hydroxy jasmonoyl sulfate via JASMONATE-INDUCED OXYGENASES (JOXs) and the sulfotransferase ST2A, and hence bioactive jasmonates decrease. As a result, JASMONATE ZIM-DOMAIN (JAZ) transcriptional repressors are stabilized; that is, jasmonate signaling is turned off, allowing hypocotyl elongation. Downstream factors of MYC2 were further identified (Fig. 1). MYC2 and MYC3 in jasmonate signaling directly regulated the expression of HY5 (designated after long hypocotyl mutants), which encodes a key transcription factor in photomorphogenesis[44]. Moreover, MEDIATOR SUBUNIT17 (MED17) was found to be regulated by MYC2 during warm temperatures[45]. MED17 is a subunit of the Mediator complex as a transcriptional coactivator and was shown to be involved in histone modification on the promoters of thermosensory genes, including PHYTOCHROME-INTERACTING FACTOR4 (PIF4) and auxin biosynthesis and signaling genes. Collectively, emerging evidence suggests that jasmonate signaling is involved, especially in stress-responsive morphogenesis, and these unique features of jasmonates may be associated with their source being membrane lipids, yet further substantiations are required.

Recently, besides JA-Ile, its precursor oxylipins generated by fatty acid oxidation, such as 12-oxophytodienoic acid (cis-OPDA) and dinor-12-oxo-10,15(Z)-phytodienoic acid (dnOPDA), have brought attention. In particular, dnOPDA was proposed to serve as a phytohormone in the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha to stimulate their growth and stress responses, similar to JA-Ile in angiosperms[46,47]. Moreover, these OPDAs were found in the biomass of some green algae[48]. Yet, the dnOPDA production appeared to be found in M. polymorpha but not in the moss P. patens[48], and further efforts will be required to reveal the evolutionary perspective when dnOPDA and JA-Ile appeared to function as phytohormones in land plants.

-

SA has been well studied in plant defense responses to pathogens. Besides this, the exogenous application of SA and acetyl SA was reported to stimulate abiotic stress resistance, including drought, heat, and chilling stresses, in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) and common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris)[49]. Interestingly, a recent study using wheat (Triticum aestivum) demonstrated that methyl SA is involved in freezing tolerance[50] (Fig. 1). The SA methyltransferase gene TaSAMT1, whose product converts SA to methyl SA, was found to be induced by cold treatment, and the respective overexpression and knockout lines exhibited enhanced and impaired tolerance to freezing, respectively, most likely due to alterations in the levels of methyl SA. Moreover, the wheat transcription factor BRASSINAZOLE-RESISTANT 1 (TaBZR1) in brassinosteroid (BR) signaling and TaBZR1-interacting histone acetyltransferase were identified to be upstream regulators of the TaSAMT1 expression. Collectively, SA and its derivatives are therefore putatively suggested to be involved in mediating abiotic stress responses, yet existing evidence remains fragmentary.

There are several possible explanations for how SA signaling affects stress responses to abiotic stresses. Polyamines, such as putrescine, which are small polycationic molecules involved in plant stress responses as well as development, and genes associated with putrescine metabolism is transcriptionally regulated in the SA signaling in Arabidopsis[51]. In addition, SA is involved in reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis in association with sumoylation[52,53]. The SUMO E3 ligase, SAP AND MIZ1 DOMAIN-CONTAINING LIGASE 1 (SIZ1), was suggested to be involved in stomatal closure under drought via SA accumulation. Intriguingly, one of the SA receptors, NONEXPRESSOR OF PATHOGENESIS-RELATED GENES 1 (NPR1), was shown to interact with the bHLH transcription factor ICE1 (whose alias is SCREAM [SCRM])[54] (Fig. 1). ICE1 was originally isolated as an upstream regulator of DRE-BINDING PROTEIN 1A (DREB1A) (also known as CRT-BINDING FACTOR 3 [CBF3]) by a screening of luciferase reporter lines[55], and has been thought to be a master regulator in cold stress signaling. However, this notion was disproven by genetic and epigenetic analyses in a more recent study[56]. Yet, SCRM/ICE1 and SCRM2 play an important role in stomatal differentiation[57]. Therefore, the study by Li et al.[54] may be interpreted as demonstrating that SA signaling via NPR1 were rather involved in stomatal development. Given that ABA signaling is also involved in polyamine metabolism, ROS homeostasis, and stomatal responses and development, future studies focusing on the ABA-SA interaction will be needed in order to uncover how these processes are controlled by phytohormones under adverse abiotic conditions.

-

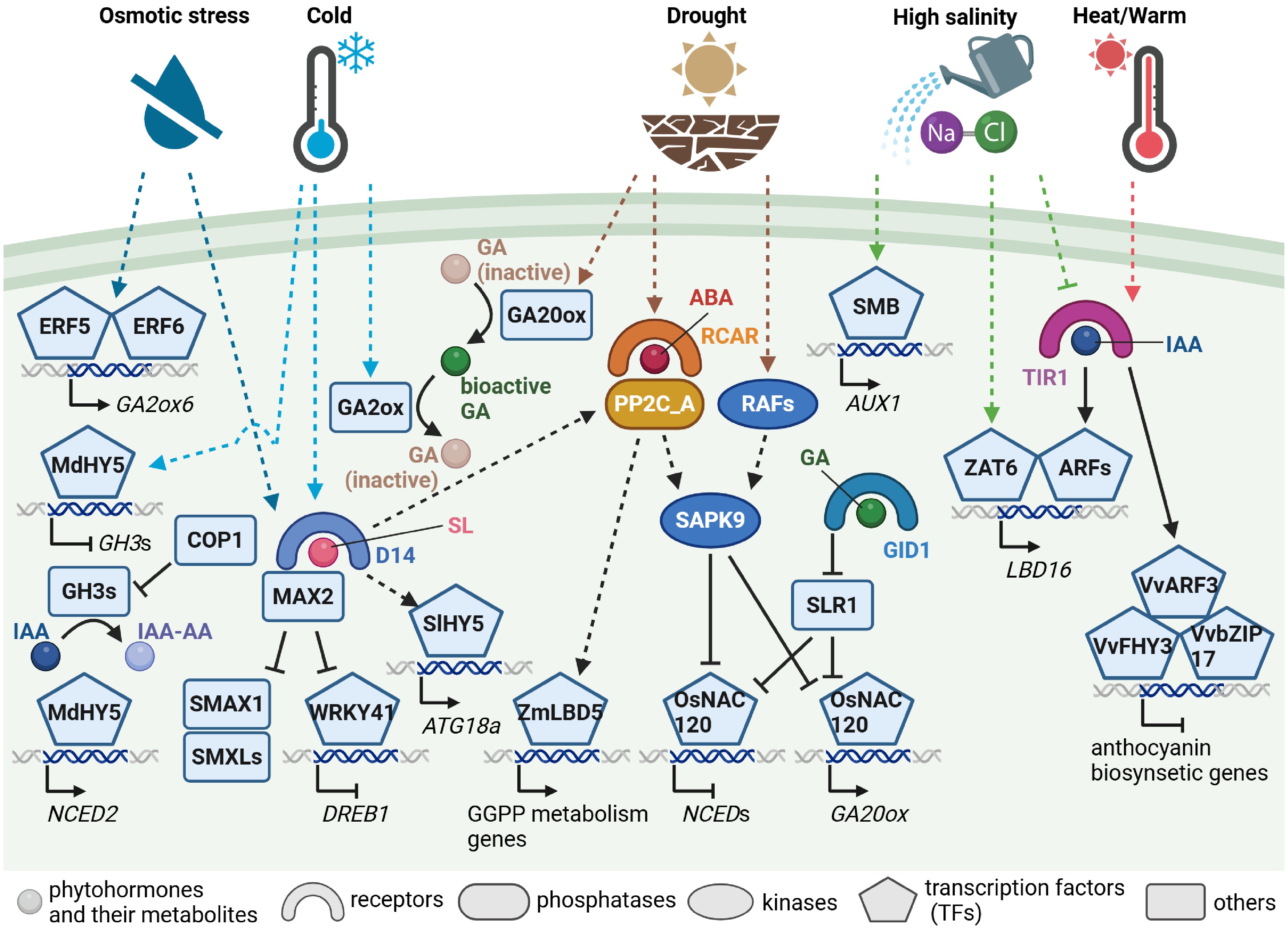

Only a few members among the over 100-strong family of GAs are biologically active in regulating plant growth and development, and their role under abiotic stress conditions is often described in interaction with other phytohormones. For instance, GA2ox6, which encodes an oxidase for inactivating GA, was induced by the ethylene response factors (ERFs), such as ERF5 and ERF6, in ethylene signaling under mild osmotic stress conditions, caused by 25 mM mannitol, in Arabidopsis, and thereby leaf growth was inhibited due to decreased bioactive GA[58]. Moreover, studies of submergence responses in rice and the wetland dicot Rumex palustris suggested a hormone signaling model consisting of ethylene, ABA, and GA controlling cell elongation[59]. Although GA and ABA act antagonistically during seed germination, relatively little is known about how these phytohormones coordinate vegetative growth. A recent study revealed that the OsNAC120 transcription factor was involved in the transcriptional regulation of GA and ABA biosynthetic genes and regulated by direct interaction with the DELLA protein SLENDER RICE 1 (SLR1)[60] (Fig. 2). Under control conditions, where GA levels are high, SLR1 is degraded via the GA receptor (for a review see Van de Velde et al.[61]), and OsNAC120 induces GA 20-oxidase (GA20ox) genes in GA biosynthesis and represses 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase (NCED) genes in ABA biosynthesis. Under drought stress conditions, OsNAC120 is inhibited by SLR1 and also degraded via phosphorylation by a rice ABA-activated SnRK2, OsSAPK9, and thus, OsNAC120-dependent induction and repression are turned off. In addition, a maize transcription factor involved in terpene biosynthesis, and also affecting the levels of both GA and ABA has been reported[62]. Terpenoid biosynthesis derived from isopentenyl diphosphate overlaps with phytohormone metabolism, including that of GA, ABA, cytokinin (CK), and BR, with geranylgeranyl diphosphate serving as a precursor of both GA and ABA. A lateral organ boundaries domain (LBD) transcription factor, named ZmLBD5, was found to regulate a series of genes in geranylgeranyl diphosphate biosynthesis and catabolism toward GA, including terpene synthase, ent-kaurene synthase, and GA2ox[62]. Moreover, the ZmLBD5 overexpressing maize exhibited promoted growth and decreased drought tolerance, probably due to increased GA1, one bioactive GA, and decreased ABA, whilst contrasting phenotypes were observed in the knockout lines. Accumulating evidence suggests that GA and ABA metabolism are somewhat linked, yet whether these factors are conserved or specific to particular species remains obscure.

Figure 2.

Abiotic stress signaling associated with gibberellin, auxin, and strigolactone signaling and metabolism. Simplified signaling pathways from phytohormone perception to transcriptional regulation of gibberellin (GA), auxin (indole-3-acetic acid [IAA]), and strigolactone (SL) in response to drought, osmotic, high-salinity, heat or warm temperature, and cold stresses. Key signaling components are illustrated using different shapes, as indicated. Arrows represent activation, T-shaped lines indicate inhibition, and dashed lines denote proposed or indirect pathways. ABA, abscisic acid; ARF, AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR; ATG18a, AUTOPHAGY-RELATED GENE 18a; COP1, CONSTITUTIVELY PHOTOMORPHOGENIC 1; D14, DWARF14; DREB1, DRE-BINDING PROTEIN 1; ERF, ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR; FHY3, FAR-RED ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL 3; GA2ox, GA 2-oxidase; GA20ox, GA 20-oxidase; GGPP, geranylgeranyl diphosphate; GH3, GRETCHEN HAGEN 3; GID1, GIBBERELLIN INSENSITIVE DWARF 1; IAA-AA, IAA-amino acid conjugate; LBD, LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES DOMAIN; MAX2, MORE AXILLARY GROWTH 2; NCED, NINE-CISEPOXYCAROTENOID DIOXYGENASE; PP2C_A, clade A protein phosphatases of type 2C (PP2C); RAF, Raf-like MAP kinase kinase kinase; RCAR, REGULATORY COMPONENTS OF ABA RECEPTOR; SAPK9, OSMOTIC STRESS/ABA–ACTIVATED PROTEIN KINASE 9; SLR1, SLENDER RICE 1; SMAX1, SUPPRESSOR OF MAX2 1; SMB, SOMBRERO; SMXL, SMAX1-LIKE; TIR1, TRANSPORT INHIBITOR RESPONSE 1; ZAT6, ZINC FINGER OF ARABIDOPSIS THALIANA 6 (created with BioRender.com).

The current understanding of transcriptional regulation of the genes in GA metabolism was highlighted above, whilst a recent modeling study suggested that post-transcriptional regulation had an important role in GA metabolism under drought and cold stress conditions[63]. GA is involved in regulating division-zone size in leaf growth in monocotyledons, and Band et al.[63] developed a multiscale computational model, including cell movement, growth-induced dilution, and metabolic activities, to investigate GA distribution in the maize leaf growth zone, and to assess the effect of drought and cold stress. The model revealed that variations in GA metabolism determined the GA distribution. Moreover, although drought and cold stress altered the transcripts of enzymes in GA metabolism, the model, additionally, predicted that GA distributions are mediated post-transcriptionally. That is, the GA20ox activity for biosynthesizing bioactive GAs was increased by drought stress, and that of GA2ox for catabolizing bioactive GAs was increased by cold stress. Upstream regulators and signaling pathways stimulating these enzyme activities will hopefully be uncovered in future studies.

-

Emerging evidence suggests the important role of auxin in growth adaptation under adverse conditions. For instance, a root cap-localized NAC transcription factor was identified to be essential for establishing asymmetric auxin distribution in response to high salinity stress[64]. In contrast, both auxin-dependent and -independent signaling pathways are crucial for root branching under high-salt conditions[65]. Moreover, a transcriptional hub of several hormone signaling, including auxin, BR, and ABA, was found in rice[66]. The role of auxin was also demonstrated in endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress (by Waidmann et al., amongst others[67]), thermomorphogenesis[68], and anthocyanin biosynthesis repressed by high temperature[69] as well as in lysigenous Aerenchyma formation[70], and in response to mitochondrially generated ROS stress[71].

Auxin is also highly central to many aspects of the plant life cycle, so we will only highlight a few of the more recent examples of its importance in mediating abiotic stress signaling responses here. Starting with the role in salt stress response highlighted above, Zheng et al. revealed that the NAC transcription factor SOMBRERO (SMB) established asymmetric auxin distribution in the lateral root cap also being responsible for the basal expression of the auxin influx carrier gene AUX1 thereby leading to directional bending of roots away from high salinity[64] (Fig. 2). That said, results of a contemporary study revealed the presence of salt-activated auxin-independent pathways alongside the auxin-dependent repressive pathways operating under high salt conditions[65].

Auxin also seems to be highly important in high temperature responses with Ai et al. recently demonstrating that roots are able to sense and respond to elevated temperature independently of shoot-derived signals. This response is mediated by a yet unknown root thermosensor that employs auxin as a messenger to relay temperature signals to the cell cycle[68]. Similarly, the high-temperature regulation of anthocyanins in grapes was recently demonstrated to be controlled by the interaction of the grape AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR 3 (VvARF3) and FAR-RED ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL3 (VvFHY3) in a complex manner which also involves the ER stress sensor VvbZIP17[69] (Fig. 2). In roots, the core splicing factor PORCUPINE both modulates the expression of central meristematic regulators and is required for the maintenance of appropriate levels of auxin in the root apical meristem[72]. Considerable further research focuses on the role of ER stress signaling and how it regulates plant growth[67,73], suggesting that this will be a key research field in the coming years. In parallel, the importance of the heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) in the maintenance of root auxin levels has been uncovered[74].

The transcription factor HY5 was similarly implicated in the regulation of cold tolerance by integrating the auxin and ABA pathways[75] (Fig. 2), while a recent systems analysis of the long-term heat stress response in Setaria revealed that indole-3-acetic acid conjugates accumulated, alongside ABA, in the heat-stressed plants and this invoked considerable shifts in both transcription and metabolism[76]. Moreover, auxin is strongly involved in the photomorphogenic response orchestrated by CONSTITUTIVELY PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1 (COP1), given that this regulator inhibits the activity of GRETCHEN HAGEN 3.5 (GH3.5), which conjugates amino acids to indole-3-acetic acid promoting hypocotyl elongation[77]. It is additionally involved in low phosphorus stress tolerance via ZmARF1 modulation of lateral root development in maize[78].

Whilst the above paragraphs discuss the extensive role of auxin in isolation, or at most in concert with ABA, in abiotic stress responses it seems likely that the responses will most likely be more highly intwined with other hormones. In keeping with this, Duan et al. defined a transcriptional hub including auxin, BR, and ABA signaling in rice[66], and it would seem likely that such networks are commonplace with, for example similar, if not greater, complexity being envisaged in hypoxia signaling[79].

-

Given that SLs were demonstrated to function as growth-associated phytohormones rather recently[80,81], relatively little is known about whether and how SLs are involved in stress responses. Interestingly, SL signaling mediated by its receptor DWARF14 (D14) under osmotic stress conditions, caused by 300 mM mannitol, might target the co-repressors involved in seed germination and hypocotyl elongation, whilst D14 is known to lead to the degradation of the co-repressor homologs in shoot branching[82] (Fig. 2). Moreover, the F-box protein MORE AXILLARY GROWTH2 (MAX2) functioning with D14 was suggested to target WRKY transcriptional repressors in cold stress signaling, activating cold acclimation[83]. Beyond these involvements, SLs are long known to be involved in response to nutrient stresses with low nitrate and low phosphate stress resulting in a dramatic elevation of SL levels[84]. Recent studies have characterized the low stress response particularly well in rice revealing that it promotes NODULATION SIGNALING PATHWAY 1 (NSP1)-NSP2 heterodimerization in order to enhance SL biosynthesis and thereby regulate shoot and root architecture[85].

In addition, SLs have recently been reported to act in concert with ABA in the drought response of barley[86], but in the absence of ABA in Arabidopsis[87], although other studies convincingly demonstrate that the SL response to drought (and also salt) stress in Arabidopsis is ABA-dependent[88]. SL has additionally been implicated in salt stress in complex experiments, identifying salt stress signaling between dodder-connected tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) plants[89] with similar experiments being used to elucidate inorganic phosphate signaling[90].

SLs have also been demonstrated to play important roles in cold stress being found to regulate HY5-dependent autophagy and the degradation of ubiquitinated proteins under cold conditions in tomato[91] (Fig. 2), while enhancing freezing tolerance by releasing the WRKY41-mediated inhibition of DREB1 expression in Arabidopsis[83]. SLs have, furthermore, been demonstrated to alleviate aluminium (Al) toxicity in a two-pronged approach—both blocking the movement of Al through the cell wall and by vacuolar compartmentalization of Al[92]. Given that SL levels, particularly in roots, increase in response to nitrate and phosphate deficiency, it will be necessary to reveal how plants respond to nutrient and abiotic stress combinations. From this perspective, an interesting observation by soybean (Glycine max) experiments in the fields was that phosphate starvation response preceded the ABA responses under mild drought stress conditions[93], yet whether SL signaling is involved in these events remains to be elucidated.

-

CKs are one of the phytohormones involved in various processes of plant growth and development, including cell division, shoot initiation and growth, leaf senescence, and so forth. In addition, increased CK contents by the ectopic expression of the biosynthetic gene isopentenyltransferase (IPT) were demonstrated to be involved in enhanced drought stress tolerance in tobacco, likely independently of ABA contents[94]. In contrast, when CK contents were decreased either by the ipt mutation or its catabolic gene overexpression in Arabidopsis, these lines exhibited enhanced drought and high-salinity stress tolerance, probably via altered ABA sensitivity[95]. Although alteration of CK levels appeared to result in opposite readouts in tobacco and Arabidopsis, at least in Arabidopsis, the interaction between CK and ABA signaling was proposed[96,97].

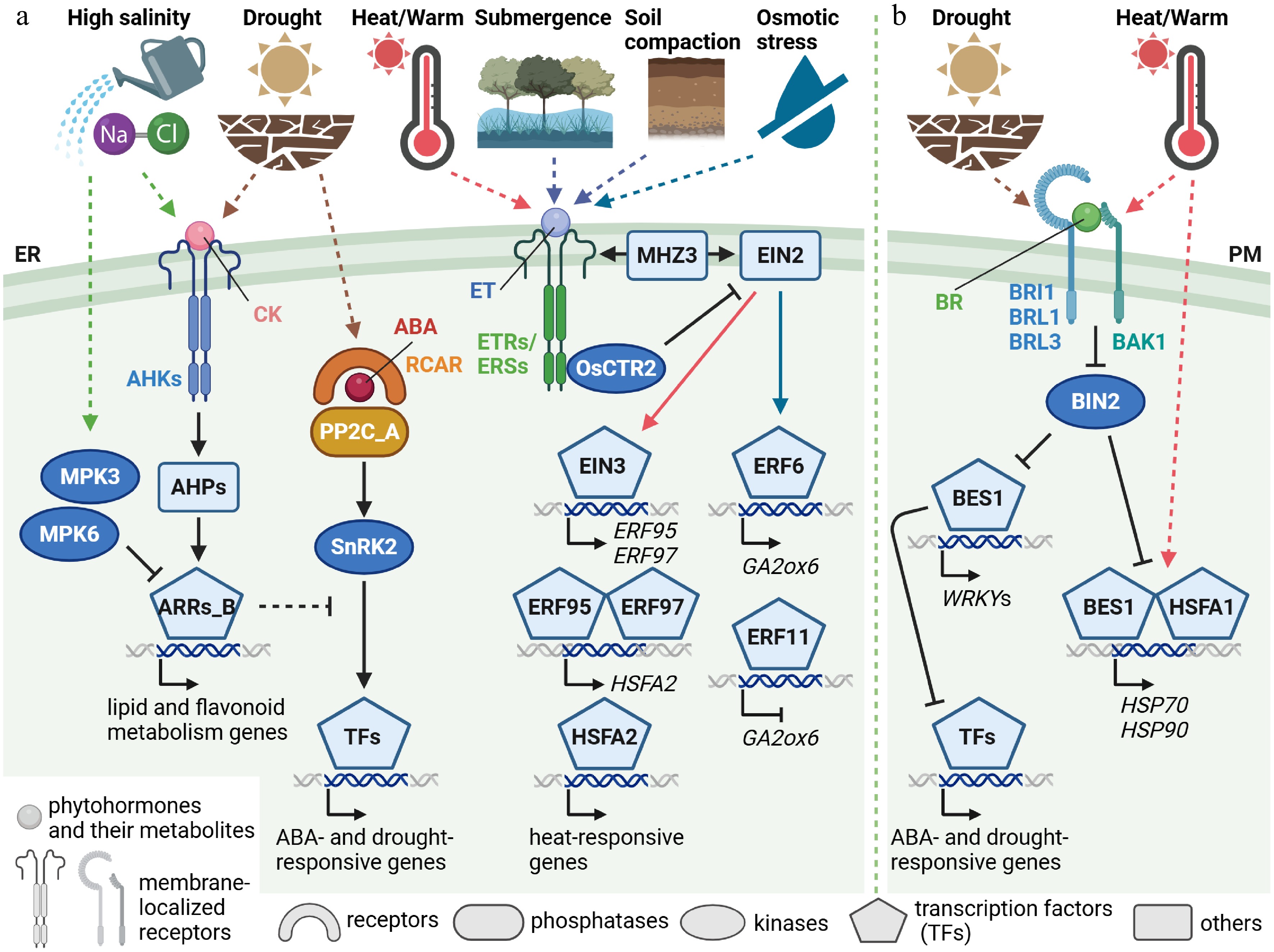

Multistep His-Asp phosphorelay is key components of CK signaling, consisting of the ARABIDOPSIS HISTIDINE KINASE (AHK) sensors, HISTIDINE-CONTAINING PHOSPHOTRANSFER PROTEINS (AHPs), and RESPONSE REGULATORS (ARRs). Recently, the CK signaling mutants of AHPs or type-B ARRs exhibited enhanced salt stress tolerance and altered metabolism[98] (Fig. 3a). In particular, the sugar and amino acid levels increased in these mutants under control and high-salinity stress conditions. Moreover, lipid and flavonoid metabolites and the transcripts in these pathways were altered in the CK-signaling mutants in response to the high-salinity stress. In contrast, whilst the AHPs transfer the phosphate to the Asp in the receiver domain of type-B ARRs, different sites were phosphorylated in response to high-salinity stress[99] (Fig. 3a). The MAP kinases MPK3 and MPK6 were shown to be activated by the salt stress treatment and mediate the degradation of the ARRs via phosphorylation. Similarly, in the absence of apparent stresses, the type-B ARRs serving as important transcription factors in CK signaling were regulated via protein degradation, albeit the turnover kinetics appeared to vary among the ARRs (for a review see Kieber & Schaller[100]). Thus, multiple layers of regulations might strictly regulate the abundance of type-B ARR proteins, which appear to regulate specific metabolites, such as lipids and flavonoids, to balance the tradeoff between growth and stress responses.

Figure 3.

Abiotic stress signaling associated with cytokinin, ethylene, and brassinosteroid signaling and metabolism. Simplified signaling pathways from phytohormone perception to transcriptional regulation of cytokinin (CK), ethylene (ET), and brassinosteroid (BR) in response to drought, osmotic, high-salinity, heat or warm temperature, submergence, and soil compaction stresses. Given that the major receptor proteins for CK and ET are localized to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane (a), whilst those for BR are localized to the plasma membrane (PM) (b), the pathways are illustrated separately for clarity. Key signaling components are illustrated using different shapes, as indicated. Arrows represent activation, T-shaped lines indicate inhibition, and dashed lines denote proposed or indirect pathways. ABA, abscisic acid; AHK, ARABIDOPSIS HISTIDINE KINASE; AHP, ARABIDOPSIS HISTIDINE-CONTAINING PHOSPHOTRANSFER PROTEIN; ARRs_B, type-B ARABIDOPSIS RESPONSE REGULATOR; BAK1, BRASSINOSTEROID-INSENSITIVE 1(BRI1)-ASSOCIATED RECEPTOR KINASE 1; BIN2, BRASSINOSTEROID-INSENSITIVE 2; BRL, BRI1-LIKE; BES1, BRI1-EMS-SUPPRESSOR 1; CTR, CONSTITUTIVE TRIPLE RESPONSE; EIN, ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE; ERF, ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR; ERS, ETHYLENE RESPONSE SENSOR; ETR, ETHYLENE RESPONSE; GA, gibberellin; GA2ox, GA 2-oxidase; HSFA, HEAT SHOCK TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR A; HSP, HEAT SHOCK PROTEIN; MHZ3, MAO HUZI 3; MPK, MAP kinase; PP2C_A, clade A protein phosphatases of type 2C (PP2C); RCAR, REGULATORY COMPONENTS OF ABA RECEPTOR; SnRK2, sucrose non-fermenting-1 (SNF1)-related protein kinase 2 (created with BioRender.com).

-

Ethylene is a gaseous phytohormone that uniquely affects plant growth, development, and stress responses. For instance, ethylene was known to be involved in tomato growth on compacted soil[101], and recently, ethylene levels were demonstrated to be sensed around roots in Arabidopsis and rice[102]. Ethylene and soil compaction inhibited root growth, and X-ray computed tomography imaging clarified nondestructively that root growth was impaired in wild-type rice but not in ethylene signaling mutants. Moreover, examinations using Arabidopsis marker lines for ethylene and oxygen revealed that soil compaction appeared to restrict gas diffusion rather than stimulate hypoxia responses. Plants may use ethylene to avoid growing toward compacted soil zones. In contrast, because of its gaseous nature, ethylene also plays an important role in hypoxic stress caused by soil waterlogging and submergence. Interestingly, a recent study in rice revealed that the membrane-localized scaffold protein, named MAO HUZI 3 (MHZ3), functions as a switch of ethylene signaling[103] (Fig. 3a). In the absence of ethylene, MHZ3 interacts with ethylene receptors, which phosphorylate and anchor the RAF kinase, the rice ortholog of Arabidopsis CONSTITUTIVE TRIPLE RESPONSE 1 (CTR1), referred to as OsCTR2, to the ER membrane. Subsequently, phosphorylated OsCTR2 phosphorylates and inactivates the key regulator ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE 2 (OsEIN2). When the receptors perceive ethylene, their complexes with MHZ3 are impaired, the attachment of OsCTR2 to the ER membrane is weakened, and OsEIN2 interacts with MHZ3 activates downstream transcription factors. Although ethylene signaling may differ to some extent among species, since Arabidopsis mutants of the MHZ3-like genes exhibited ethylene-insensitive phenotypes[104], MHZ3 appeared to be a conserved regulator of ethylene signaling.

Transcription factors, including EIN3 and ERFs, function downstream of EIN2. ERFs control various ethylene responses, and several members, such as ERF6 and ERF11, were involved in growth regulation via altering GA metabolism in response to mild osmotic stress[58,105] (Fig. 3a). Moreover, the interaction of ethylene with other phytohormones was often discussed with GA in thigmomorphogenesis and cell elongation, as described in the sections on jasmonates and GAs, respectively. Furthermore, ethylene signaling regulates temperature responses. Under warm ambient temperature, EIN3 in ethylene signaling was demonstrated to be protected from proteasome-dependent degradation via the further upstream factor[106] and recruited, as well as the EIN2 C-terminal end, to chromatin to activate specific genes[107]. Recently, a transcriptional cascade consisting of EIN3, two ERFs, and a heat shock transcription factor (HSF) was uncovered to play an important role in acquiring basal thermotolerance[108]. In contrast, recent studies shed light on epigenetic and translational regulation in ethylene signaling. Particularly, the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, which biosynthesizes nuclear acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl CoA) serving as a donor of acetyl groups to Lys on histone N-terminal tails via histone acetyltransferases, was reported to accumulate in the nucleus in response to ethylene and interact with the EIN2 C-terminal end leading transcriptional reprogramming[109]. Moreover, EIN2, and a type of eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) kinases, named GENERAL CONTROL NONDEREPRESSIBLE 2 (GCN2), were demonstrated to be involved in modulating translational dynamics, including translational repression and enhancement, in ethylene signaling under submergence[110]. Another study also identified a rice Gly-Tyr-Phe domain protein, MHZ9, as a translational regulator in response to ethylene[111]. Whether these newly identified regulators in ethylene signaling are involved in other ethylene-associated processes, such as fruit ripening, and whether they are conserved among plant species will be attracting open questions.

-

BRs have emerged as key regulators of abiotic stress adaptation through both cell-autonomous and systemic mechanisms. The exogenous application of BR compounds has been used widely in agriculture to promote plant growth under different abiotic stress conditions[112]. Early functional studies provided contradictory results regarding the functions and molecular mechanisms of BR signaling in abiotic stress tolerance. Overexpression of the canonical BRASSINOSTEROID-INSENSITIVE 1 (BRI1) pathway conferred tolerance to freezing stress[113], and overexpression of the BR biosynthetic gene DWARF4 conferred resistance to dehydration and heat stress[114]. Conversely, other studies have shown that bri1 loss-of-function mutants are resistant to drought stress[115,116]. Specifically, partial suppression of BRI1 in Brachypodium distachyon and Arabidopsis resulted in dwarf phenotypes coupled with enhanced drought tolerance. Supporting this, increased levels of BR-regulated transcription factors such as BRI1-EMS-SUPPRESSOR1 (BES1) were shown to have antagonistic effects in drought stress responses, modulating stress-induced growth repression through interactions with key transcription factors including WRKYs (Fig. 3b)[116,117]. In conclusion, early functional studies of BR signaling mutant plants subjected to stress highlighted the complexity and context dependency of BR signaling in abiotic stress responses.

A more refined understanding came from a comprehensive analysis of Arabidopsis BR receptor mutants[118]. The study identified that all the different combinations of BR receptor loss-of-function mutants exhibited small dwarf phenotypes and enhanced resistance resistant to osmotic and drought stress, while the overexpression of the receptor BRI1-LIKE 3 (BRL3) produced drought-resistant plants without penalizing growth. Phenotypic, physiological, and multi-omics analyses unveiled distinct mechanisms behind these resistant phenotypes. BR loss-of-function mutants exposed to drought showed growth arrest, insensitivity to water loss, no stress-related gene activation, and lack of ABA and other stress-related metabolite accumulation, following a drought avoidance mechanism. Subsequently, in BRL3 overexpression plants, drought stress induced the transcriptional activation of stress-related genes and the accumulation of osmoprotectant metabolites, indicating an active drought-tolerance mechanism[118]. Supporting this model in monocots, untargeted mutagenesis of the SbBRI1 receptor in Sorghum bicolor led to the reprogramming of phenylpropanoid metabolism and increased drought resilience, further supporting BRs as regulators of stress-related metabolic pathways[119]. They show that Sbbri1 mutants show increased tolerance to drought stress, while SbBRI1 overexpression lines were more sensitive. SbBES1 regulates lignin biosynthesis in normal conditions while during drought stress, reduced SbBES1 activity shifts metabolism towards the flavonoid pathway, enhancing photosynthetic efficiency and drought resistance in sorghum[119].

Recent studies have revealed a mechanistic framework by which BR signaling enhances thermotolerance through multiple convergent mechanisms. BES1 is activated by heat stress independently of BR signaling and directly binds to HEAT SHOCK ELEMENTS (HSEs) in the promoters of HSP70 and HSP90 (Fig. 3b)[120]. Moreover, BES1 directly interacts with HSFA1s, stabilizing them and enhancing their DNA-binding activity to HSEs, thereby promoting the expression of HSP70 and HSP90 under stress conditions and forming a positive feedback loop that reinforces the heat shock response[120]. This interaction enhances the plant's ability to withstand elevated temperatures. In addition, the GSK3-like kinase BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE 2 (BIN2) phosphorylates HSFA1s under control conditions, restricting their nuclear accumulation and transcriptional activity, while BRs inactivate BIN2 to relieve this repression, enabling HSFA1-driven transcriptional reprogramming during heat stress[121]. Moreover, at the systemic level, the vascular BR receptor BRL3 mediates thermotolerance signaling from the phloem, coordinating stress adaptation across tissues through transcriptional and metabolic priming[122]. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that BR signaling promotes thermotolerance through multi-layered mechanisms: direct activation of HSFA1s and heat shock proteins, inhibition of negative regulators such as BIN2, and systemic integration of heat responses via vascular signaling.

-

The growing evidence highlighted here suggests that phytohormone signaling and metabolism are involved in mediating abiotic stress signaling in various ways. Moreover, the interactions among phytohormones appear to play an important role in balancing between plant growth and stress responses under adverse conditions. However, key open questions are how plants sense environmental cues and what are crucial integrators between phytohormone signaling pathways. Recently, abiotic stress-sensing mechanisms have been increasingly reported in Arabidopsis[28,32,123], yet further validations are necessary. Moreover, to capture the special-temporal dynamics of phytohormones, future technological advancements in sensitivity and resolutions in bulk analyses, such as mass-spectrometry-based comprehensive hormone profiling[124], and non-destructive sensors, such as genetically encoded biosensors[2−4], and amperometric sensors[5], will be essential. Fine control of phytohormone metabolism and signaling by manipulating newly reported sensor genes and by the state-of-the-art measurement technology will deepen our insights into phytohormone signaling and metabolism, particularly under environmental stress conditions associated with global climate change.

This work was supported by the Max-Planck Society (to ARF).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceived the topic and structure of the review: Yoshida T, Fernie AR; conducted the literature survey and drafted the manuscript: Yoshida T, Fàbregas N, Fernie AR; prepared the figures: Yoshida T. All authors discussed the content and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

This review contains no new experimental data.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Chongqing University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Yoshida T, Fàbregas N, Fernie AR. 2025. Unveiling links between phytohormone and abiotic stress signaling. Plant Hormones 1: e025 doi: 10.48130/ph-0025-0025

Unveiling links between phytohormone and abiotic stress signaling

- Received: 30 June 2025

- Revised: 22 September 2025

- Accepted: 27 October 2025

- Published online: 17 November 2025

Abstract: Signal integration is essential for organisms to fine-tune their growth, development, and stress responses. Phytohormones, serving as endogenous signals, play important roles in mediating various processes in response to environmental cues. Extensive research to date in genetics and molecular biology has uncovered the central regulators of phytohormone signaling, such as receptors, protein kinases, and transcription factors. Here, recent advances in how these phytohormone signaling pathways mediate environmental signals are highlighted, especially focusing on newly identified components and their links with the core regulators under abiotic stress conditions. With particular interests in transcriptional readouts, how environmental signaling impacts the perception and signal transduction of phytohormones and their interactions are discussed.

-

Key words:

- Phytohormones /

- Abiotic stress /

- Signaling